Abstract

In today’s global economy, where informality and insecurity characterise working life for millions, scholars, activists, and political authorities are looking for radical solutions. One of the most commonly advanced is universal basic income (UBI), which is widely theorised as a tool for enhancing worker power and improving work, through offering workers an ‘exit option’. Critics retort that social and economic life are too complex for UBI to be a magic bullet and that UBI could even make life worse. To date, very few studies have empirically interrogated this debate. This paper reports findings from what we believe to be the first two pilots to do so. Both combined unconditional cash and community organiser support in India and Bangladesh over two years. Our findings suggest that UBI can enhance worker power, enable partial exit, and support collective organisation. Its limitations leave us doubtful, however, that UBI alone could fundamentally alter labour relations.

1 Introduction

In today’s precarious global economy, where informality and insecurity characterise working life for hundreds of millions, scholars, activists, and even political authorities have begun looking for radical solutions. Universal basic income (UBI) frequently finds itself at the top of the list of proposals (e.g. Weeks 2011). Defined as a regular cash grant given to all people within a political community without means test or work requirement,[1] UBI is widely asserted to be able to tip the balance of power between workers and employers in favour of workers, by providing a source of sustenance and an economic floor outside labour, enhancing freedom and bargaining power (Widerquist 2013). The primary claim here is that UBI can offer the possibility of ‘exit’ – from a given labour relationship and from wage labour more broadly. An impressive body of literature has developed to substantiate this claim, while a more recent yet similarly rigorous literature has emerged to counter and caveat it. This paper begins by surveying the contours of the ‘UBI and Exit’ debate, before describing two major recent pilot studies that sought to empirically interrogate it. Those two pilots – known by the acronyms WorkFREE and CLARISSA – took place over 2 years in India and Bangladesh respectively and in each case involved the combination of unconditional cash and community organising. To our knowledge, they are the first experiments designed specifically to empirically ‘test’ claims around UBI and exit. In the second half of this paper, we present our findings from them. We conclude with implications for theory, advocacy, and policymaking around UBI, precarity, and worker power.

2 UBI, Labour Power and Exit

There are three main groups of claims that theorists make about UBI’s capacity to enable exit. These are categorised by some as existing on a spectrum running from ‘weak’ through ‘strong’ to ‘radical’ exit (Birnbaum & De Wispelaere 2016), and by others as combining the elements of ‘exit’ and ‘voice’ from Hirschmann’s seminal ‘Exit, Voice and Loyalty’ paradigm (Hirschmann 1970; Casassas 2016, 2024). We group these claims into three overarching themes under the banners of ‘Exit’, ‘Partial Exit’ and ‘Voice’, with Table 1 summarising the sub-claims into which these three meta-claims break down.

UBI and claims around exit.

| UBI can enable: | 1. Exit | …Taking the Form of… | 1.1 Leaving undesirable work and surviving |

| 1.2 Choosing activities other than work and surviving | |||

| 2. Partial exit | 2.1 Reducing dependence on undesirable work, for example through reducing working hours | ||

| 2.2 Re-balancing work/non-work time-use to combine desirable non-work activities, such as schooling, with work | |||

| 3. Negotiation/Voice backed by the threat of exit | 3.1 Increasing individual negotiating power to improve working conditions | ||

| 3.2 Increasing collective negotiating power to improve working conditions |

2.1 Exit

Calls for the adoption of some form of UBI are as old as capitalism itself (Wright 2010). They rely on the central Marxian insight that those divorced from the means of (re)production are as free to choose their employment as they are to starve. In other words, their ‘double freedom’ is really coercion masked as consent, since they cannot but accept whatever work is made available to them (Howard 2018). Representatives of political philosophical traditions as varied as liberalism, libertarianism, socialism and republicanism all accept the historical injustice embedded within this double freedom (and its unequal distribution) and thus propose various forms of UBI to offset it (Standing 2012). Providing an unconditional cash floor for all to stand on, they suggest, will enable ‘real freedom for all’ (Van Parijs 1997), understood by some as ‘the power to say no’ (Widerquist 2013), by others as ‘non-domination’ (Pateman 2004), and by others still as ‘social power’ (Casasass 2024). In each case, a counterfactual claim is at work: if people have to submit to undesirable, abusive or exploitative working conditions for want of a better alternative purely in order to survive, then ensuring that we all enjoy a survival-enabling UBI will empower us to resist such working conditions by walking away from them, which could in turn force a structural change in the social organisation of work (Weeks 2011). Birnbaum and De Wispelaere (2016) would characterise exit of this sort as ‘strong’ (entailing workers walking away from undesirable work for superior alternative jobs) or ‘radical’ (entailing substantial or even indefinite periods away from wage labour).

A second claim around UBI and exit centres on UBI’s putative ability to enable recipients to choose to spend their time on activities other than work, such as education, care, or personal/spiritual growth. Kathi Weeks and the ‘postwork’ tradition that she represents are important advocates of this position, arguing that the human condition is too complex and human needs too broad to be satisfiable only in and through paid labour (2011; Srnicek & Williams 2015). Taking this further (and inspired by Gorz), this tradition argues that the requirement to engage in paid labour as much as we do tends to crowd out important aspects of the full development of the human person. Not only do we all obviously need (to) care, but we also need to learn, play, explore, connect, and grow (Gorz 2007). Given this, and in light of the battle for time that is at the heart of the wage labour relationship (Standing 2023), scholars like Gorz and Weeks argue that the unconditional material security provided by UBI is a necessary pre-condition for enabling people to re-balance their lives away from paid labour and towards other pursuits that they have reason to value. This does not necessarily mean that people will choose to leave work because they experience it as exploitative or domineering; rather, it could mean that they simply choose to spend their time engaged in activities other than work which, for whatever reason, they find more attractive and appealing.

2.2 Partial Exit

Extending the above argument further, scholars like Birnbaum and De Wispelaere rightly point out that not all undesirable work is undesirable enough for people to walk away from it entirely. In addition, citing what they call a ‘realistic understanding of how labour markets operate and how the opportunities of disadvantaged workers are presently structured’ (2021: 909), they make the case that leaving work may entail economic, social, and affective costs which make doing so unpalatable (ibid.). In such instances, UBI could function as a means to enable an employee ‘to relax her dependence on an employer while nevertheless not fully severing the employment relation’ (2016: 62), for example through reducing working hours. Birnbaum and De Wispelaere characterise exit of this sort as ‘weak’ or ‘incomplete’ (ibid.; 2021); we approach it as ‘partial’.

Data from multiple empirical studies support the notion that people in receipt of unconditional cash will use such partial exit to pursue other activities that are desirable (Hum & Simpson 1993; Calnitsky & Latner 2017; Kangas et al. 2019; West & Castro 2023; Kappil et al. 2023; Brugger et al. 2023). Typically, these activities include care for children and other relatives, higher education, or opportunities to retrain, with respondents consistently citing the importance of ‘work-life balance’ and being able to ‘be with’ the people that matter in their narrations of basic income’s impacts (West & Castro 2023; Kappil et al. 2023; Brugger et al. 2023). What this points to is what a substantial strand of UBI theory has long claimed – that UBI could enable people to re-organise their time to spend more of it in valuable non-work activity without the cost of doing so becoming too great to bear (e.g. Van Parijs 1997).

2.3 Voice

Intricately related to the notion of ‘exit’ within UBI theory is the sister notion of ‘voice’, which draws heavily on Albert O. Hirschmann’s classic three-pronged categorisation for social relationships in situations of conflict and deterioration (1970). Hirschmann outlines three possible options in the face of such deterioration: loyalty to the relationship in question, exit from it, or recourse to raising one’s voice to challenge its functioning and try to modify it (Casassas 2024: 77). Crucially, when applying this framework to the world of paid work, commentators note that the effect of raising one’s voice to advocate for improved working conditions will likely be dependent upon the relative power between the worker and the employer: if the employer has no incentive to listen and the worker cannot make him do so, then the worker’s voice may go unheeded and their circumstances will stay the same (or, plausibly, even worsen) (ibid. 78–9; Wright 2010; Haagh 2018). This is where the ‘credible threat of exit’ becomes important. As Birnbaum and De Wispelaere explain, threatening to leave a work relationship (and thus impose costs on an employer) increases the chances of the employer being willing to listen to the grievances being voiced (2021: 912). In Casassas’ terms, ‘if people … are able to stand up and leave, their voices will be heard, or at least they won’t be as muted as they were’ (Casassas 2024: 77). The theoretical relationship between UBI, exit, and voice can be understood as follows: freedom at work requires the ability to bargain; bargaining power requires the ability to exit; and exit requires the ability to sustain oneself when one does. For this, UBI is essential. But UBI can also be helpful even in scenarios where the employer-employee relationship is not quite so evidently dominating. One can imagine, for example, a well-meaning employer who is quite willing to listen to worker requests for improved working conditions but who never receives them because the workers in question lack the confidence to approach the employer and make them. In this scenario, the material and thus psychological security provided by a UBI could plausibly increase worker self-confidence and thus make it easier for less sure-footed workers to raise their voices (Jütten 2017).

Voice can, of course, also be understood and operationalised collectively, and a final strand of theorisation around UBI and exit holds that UBI can make it possible for workers to combine to exercise their collective power in advocating for improved working conditions. Again, the mechanisms at play here are twofold. First, the unconditional material security provided by UBI reduces risk (of punishment or termination) and increases confidence (to take risks), with a plausible outcome that it can support groups of workers to come together to make joint petitions to employers. Second, the backing of a UBI could operate as a kind of ‘strike fund’, enabling employees both to credibly threaten employers with exit if they fail to listen and to actually exit, temporarily or permanently, unless and until improved conditions are offered (Wright 2010; Van Parijs 2015). Birnbaum and De Wispelaere categorise exit of this sort as ‘strategic’, in that it is a conscious tool used to improve the worker’s position vis-à-vis the employer (2021). In this vein, Van Parijs states that the social impact of UBI is ‘above all to increase bargaining power on all fronts by multiplying exit options’ (2015: 168).

3 Counters and Caveats

The claims above are all heavily contested, even from within literature that is broadly supportive of UBI and its emancipatory potential. We summarise the caveats and counters found in that literature below.

The first, and most obvious, is that for UBI to enable exit, then the amount of money provided by that UBI would need to be sufficient to replace the returns to labour. As Birnbaum and De Wispelaere put it, ‘the potential of basic income to make exit options available…depends importantly on the level of such a uniform payment’ (2021: 2015). For Erik Olin Wright, that level has to be pegged to a notion of ‘liveability’, implying a sum ‘that would enable a person to live at a respectable, no-frills level’ (Wright 2006: 8). Without this, no real exit would be possible, either because the UBI would fail to support survival or because it would enable a level of survival so basic and removed from that which the worker would leave behind as to make exit unviable. This means, in Wright’s words, that the level of the UBI has to be ‘sufficiently high that withdrawing from the capitalist labor market is a meaningful option’ (ibid.). Yet, as many commentators have been quick to argue, there is no guarantee that such a level will be forthcoming, particularly in capitalist states (Gourevitch & Stanczyk 2018). Orlando Lazar, for one, suggests that such a UBI will always be unlikely as the level of the income required will be ‘especially demanding if it is to provide workers with the power of radical exit’ (2020: 498). Likewise Alex Gourevitch, who dismisses as overblown the exit argument on grounds including the improbability of the amount ever being sufficient (2016). Notably, even Philippe Van Parijs, one of UBI’s great advocates, recognises that delicate balances will need to be struck between tax levels and UBI levels if we are to ensure the scheme’s sustainability (Van Parijs & Vanderborght 2017, Ch. 6).

Taking this point further, friendly critics point out that the entire argument around UBI’s potential ability to support exit hides an enormous sine qua non assumption – that a UBI will be permanent (Gourevitch 2016; Dinerstein & Pitts 2021). For if it were not, then what security would people have? And what safe exit would be possible? Even worse, if people were to believe and behave as if their UBI were permanent only for it to be unexpectedly withdrawn, then plausibly their UBI could see them end up in worse, even more vulnerable circumstances than when they started.[2] For sympathetic critics like Lazar (2021) and De Wispelaere and Morales (2016), one possible solution to this dilemma is for UBI to be written into a polity’s constitution, providing a bedrock guarantee of non-withdrawability. Yet even they recognise that this is highly unlikely, at least at the present juncture and in most capitalist states. For more sceptical critics like Dinerstein and Pitts, the dangers of UBI being withdrawn once granted are so great as to merit debate over the policy’s desirability at all. What, for example, might be the consequences for people’s freedom, and indeed for any viable exit, if UBI were granted by a totalitarian state that made UBI integral to survival and thus, paradoxically, wielded it as a tool of social discipline (2021)?

Stepping down from macro concerns around totalitarian authority, there exist a further group of caveats and counters to the claims made about UBI and exit, which centre on the lack of meaningful alternatives available to would-be exiters (Gourevitch 2016; Lazar 2021). Simply put, this argument contends that for exit from a given labour relationship to be a practicable option, the person exiting will need realistic alternatives to move on to. If they choose to leave their job and let go of the financial and other benefits it provides, is there another job offering similar benefits that they can realistically avail themselves of? What will they do if there is not? Or indeed if the jobs that are available happen to be outside of their competence, in fields beyond their training, or offered by employers unwilling for whatever reason to employ them? Of course, an adequate level of UBI would guarantee the exiting worker their survival. But it would be unlikely to cover the full costs associated with exiting or reducing dependence on a given labour relationship, including, in Global North contexts, the healthcare, pension, employer contributions, or wages that enable life choices that matter to the worker, such as holidays or school fees. In Global South contexts, where the informal economy is the norm, we may add to this list the many non-wage benefits attached to patronal, relationship-dependent work arrangements, such as ‘gifts’, loans, or access to social services provided by employers to their employees.

The social organisation of labour and its centrality to social life also matters for the fourth of our counterarguments, which focus on the social and affective obstacles making easy exit difficult. In their Global North-focussed discussion of these concerns, Birnbaum and De Wispelaere note that ‘basic income may not compensate for the loss of social value and the risk of social stigma associated with becoming unemployed when the exit strategy fails’ (2021: 918). Alex Gourevitch points to something similar when he argues that a basic income can never fully compensate for the loss of social standing, respect, or connection associated with having a (particular) job (2016: 24; see also Lazar 2021). Kathi Weeks rightly points to ‘the ideology of work’ at play here, with people’s social standing and sense of self-worth typically tied to their occupation (2011). Beyond this, there are also the social relationships that an exiting worker may need to forego, along with the sense of community, belonging, and even identity that derive from a shared workplace that will no longer be shared. Likewise, the non-work facets of an individual’s life that may be contingent upon work, such as where one lives. It is plausible, for instance, that leaving a job and struggling to find a similarly compensated alternative may compromise one’s ability to continue living in the same locality, with all the implications that this could have for social and affective life, for individual and family relationships, schooling, childcare, and so on. Once more, this can be imagined to be all the more constraining in certain Global South contexts, for example for the armies of live-in staff employed to work in wealthy homes or cultivate large land-holdings, whose remuneration includes non-wage benefits such as accommodation. These considerations all lead Orlando Lazar to ask, not without irony, ‘Are you really going to leave your job because your boss told you to organise those files alphabetically, rather than by date?’ (2021: 435). A UBI could soften the blow associated with exit, such critics argue, but certainly not enough to make it cost-free; it may therefore only ever be useful in extreme cases.

Building on the above, the last two counterarguments address the Hirschmanian claim that UBI-guaranteed exit can strengthen worker voice and bargaining power, with potentially beneficial consequences for workers and their working conditions. These claims were comprehensively challenged by Birnbaum and De Wispelaere in their appropriately titled 2021 piece, ‘Exit strategy or exit trap?’ ‘The painful reality’, they state, ‘is that, in a relatively slack labour market, for every precarious worker that signals a readiness to exit or decides to leave there are scores of others waiting to take the vacant job’ (p. 921), which is particularly true in parts of the Global South, where our own empirical work took place. Unless the structural features of neoliberal globalization change, they suggest, this situation is unlikely to improve – low-skilled workers in low-skilled jobs are eminently substitutable, reducing the threat of exit posed by any given individual. Taking this argument further, Birnbaum and De Wispelaere also point out that in much of the world low-skilled work faces the threat of automation, since the ‘availability of low-cost technologies that could make existing jobs redundant is generally greatest in the context of routinized labour’ (ibid.). Paradoxically, therefore, the danger is that a UBI may end up making it easier and more socially acceptable for employers to replace their employees than for employees to leave their employers.

The final of our theoretical counterpoints draws on the central, Marxian insight that when workers combine to agitate for better wages or working conditions, employers eventually respond with investments in labour-saving technology. Andreas Malm tells this story in minute detail in his masterful Fossil Capital, lamenting the many pyrrhic victories Britain’s early factory workers won before industrialists turned to ever-more advanced machinery in order to regain full control over the productive process and, in the end, over labour (2016). Whatever victories workers may win, therefore, with their UBI-backed collective action or its threat, may only hasten their own demise. Birnbaum and De Wispelaere add further caution here, noting that a UBI could paradoxically weaken collective efforts towards emancipation by enabling further segmentation and hierarchisation of the labour market. ‘Workers can plausibly be placed on a continuum’, they state, ‘both in terms of their opportunities to find alternative employment and in terms of how valuable their retention is to the employer’ (2016: 69). Those who are valuable will thus presumably be equipped with genuine exit-threat power, while those who are not, will plausibly face the opposite fate. A possible outcome could be that ‘management may decide to improve the employment conditions of these workers as part of a retention strategy for high-value employees, but simultaneously decide to save on labour costs by further reducing pay and working conditions for the precariat’ (ibid.). In a world where not all work or workers are the same, it is thus possible that a basic income could be exploited by the holders of economic power to segment and stymy the growing social power of a UBI-enabled working class-for-itself. This danger is evident in the formal economies of the Global North and, once again, perhaps even more so in the informal economies of the Global South, where precarious, low value-added labour is the norm.

In the face of such extensive theoretical debate, we turn our attention now to our empirical research, the insights it offers, and the implications these have for theory around UBI, labour, and exit.

4 The Research

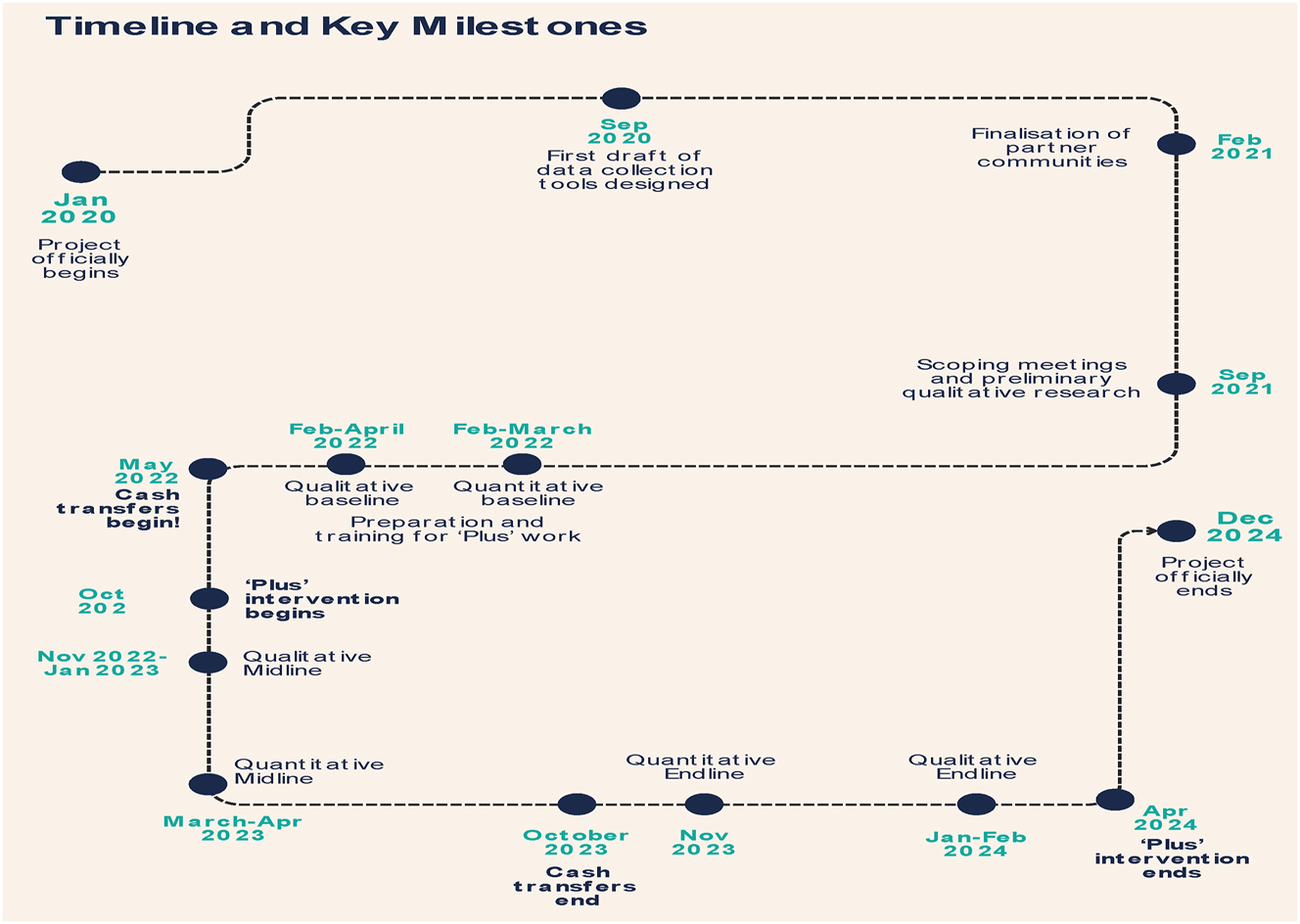

Our research took the form of two large-scale social experiments with residents across five informal settlements in Hyderabad, India and Dhaka, Bangladesh. The first, known by the acronym ‘WorkFREE’,[3] was a five-year project funded by the European Research Council. It brought together scholars, activists and civil society institutions from India and the UK to pilot what we called ‘UBI+’ in four informal settlements in inner-city Hyderabad, where residents primarily made their livings from garbage collection, daily wage labour, and domestic work. UBI + combines UBI and needs-focused, participatory community organising to support people to increase their power to meet their needs. The intervention phase ran for 24 months, 18 of which involved cash delivery. Rs. 1,000 were given monthly to each adult and Rs. 500 to mothers for each of their children. The intervention was universal and unconditional across each of the participant communities and involved approximately 1,400 people from 350 households. Roll-out of both intervention arms was led by a locally respected community organisation (see Figure 1 for the project timeline).

WorkFREE timeline and key milestones.

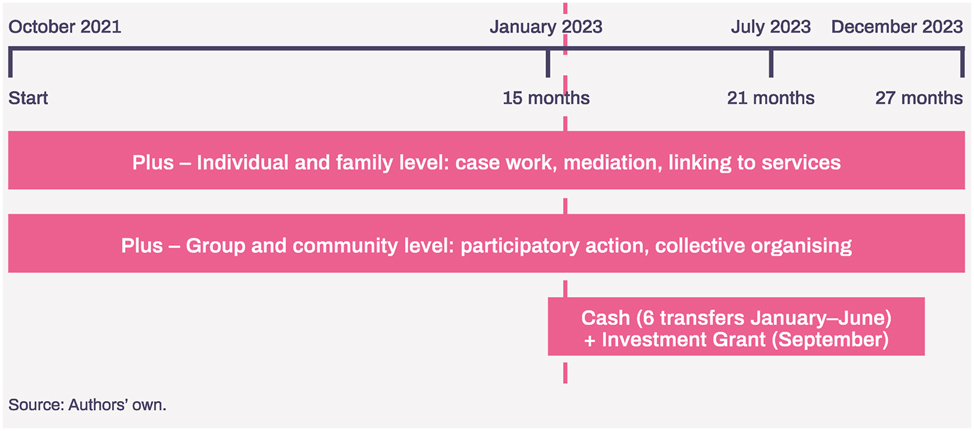

The second project was known by the acronym ‘CLARISSA’.[4] Funded by the UK’s Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO – formerly DfiD), this brought together researchers, international development actors, and civil society institutions from the UK, Switzerland, and Bangladesh. Like WorkFREE, the intervention combined cash and non-cash elements delivered by a respected local community organisation, but was framed as a ‘Cash+’ rather than a ‘UBI+’ pilot. This was because of the consortium’s political relationships with the Social Protection and Cash Transfer communities, each of whom use the term ‘cash plus’ to refer to bundled interventions like this. We chose to speak their language to increase our chances of influencing them with our findings. As with the WorkFREE project, the CLARISSA ‘plus’ included needs-focused, participatory community organising, as well as more traditional forms of assistance such as coaching and connecting residents to existing services. The plus was delivered for a period of 24 months. The cash, by contrast, was only delivered for seven months, because the British government enforced last-minute budget cuts on the programme, which reduced its cash component from the initially planned 18 months to seven (see Figure 2). Like WorkFREE, CLARISSA operated universally and unconditionally across the entire community, with the difference that cash was delivered to households rather than individually. This was in response to a feasibility study, which showed that participants preferred household to individual transfers. Transfer amounts were adjusted by household size, so that the amount that each household received was similar to what was received by WorkFREE participants in India (around 3,000 Taka per household per month, equating to approximately 20–25 % of household monthly income). Just over 1,500 households took part in the project, totalling more than 5,000 individual participants.

Clarissa intervention timeline.

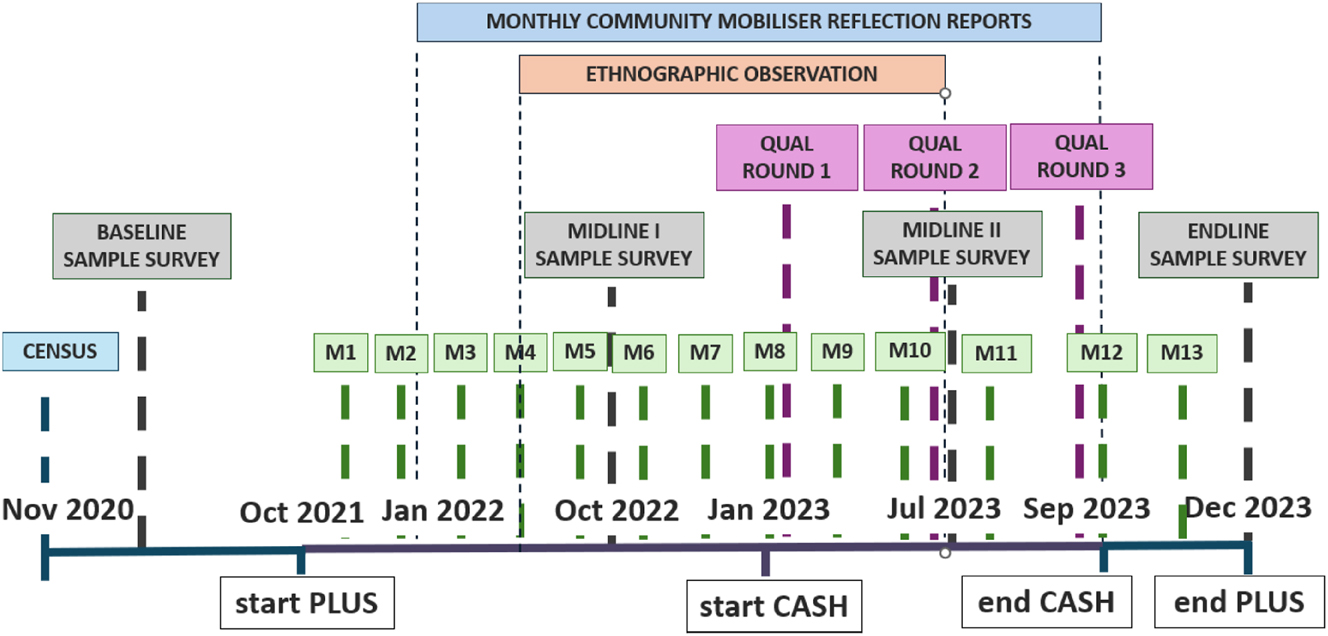

Both projects sought to explore a range of questions, including what impact the interventions had on labour relations, on freedom from exploitation, and of course on exit. Each used a suite of quantitative and qualitative methods to build their evaluations. Quantitative research included baseline, midline, and endline surveys, which collected information about key outcome indicators, such as time-use, people’s engagement with different forms of work, schooling, household living conditions, sources of income, and respondents’ perceptions of change. In India, the quantitative sample included all 350 participating households. In Bangladesh, we used a sub-sample of approximately 750 households. This was also complemented by bi-monthly monitoring surveys administered by the community organisers, asking questions about wellbeing, perceived economic resilience, school attendance, and so on. These data were used to descriptively analyse trend changes, documenting households’ perceptions of change and its causal attribution, for example through the construction of contribution scores. Qualitative tools were used to probe topics and results of interest, as well as impact pathways. These included in-depth case studies with select households followed over multiple rounds, three rounds of focus group discussions (FGDs) with community members, and long-term ethnographic observation (see Figure 3). Neither project used a randomised control design, and both were rooted in realist approaches to evaluation that used a mixture of theory and empirics to assess what worked for whom under which conditions (Mayne 2012; Ton 2022). This involved attempting to tease out the individual and combined impact of the two intervention arms, with extensive attention paid to the interaction between them. Informed consent was gained from all participants, both to be part of the experiment and to partake in data collection.

Clarissa research.

5 Our Findings

We structure the discussion of our findings in this section around the three broad groups of claims made within the literature on UBI and exit listed in Table 1, namely Exit, Partial Exit, and Voice. In each case, the discussion will refer to the sub-claims identified in that table and to the counterclaims subsequently articulated in the counters and caveats section. We will present quantitative findings alongside examples from our qualitative material. Qualitative data are chosen for fit and representativity; we avoid cherry-picking suitable examples. The Discussion section will relate our findings back to the wider literature and draw out their implications.

6 Exit

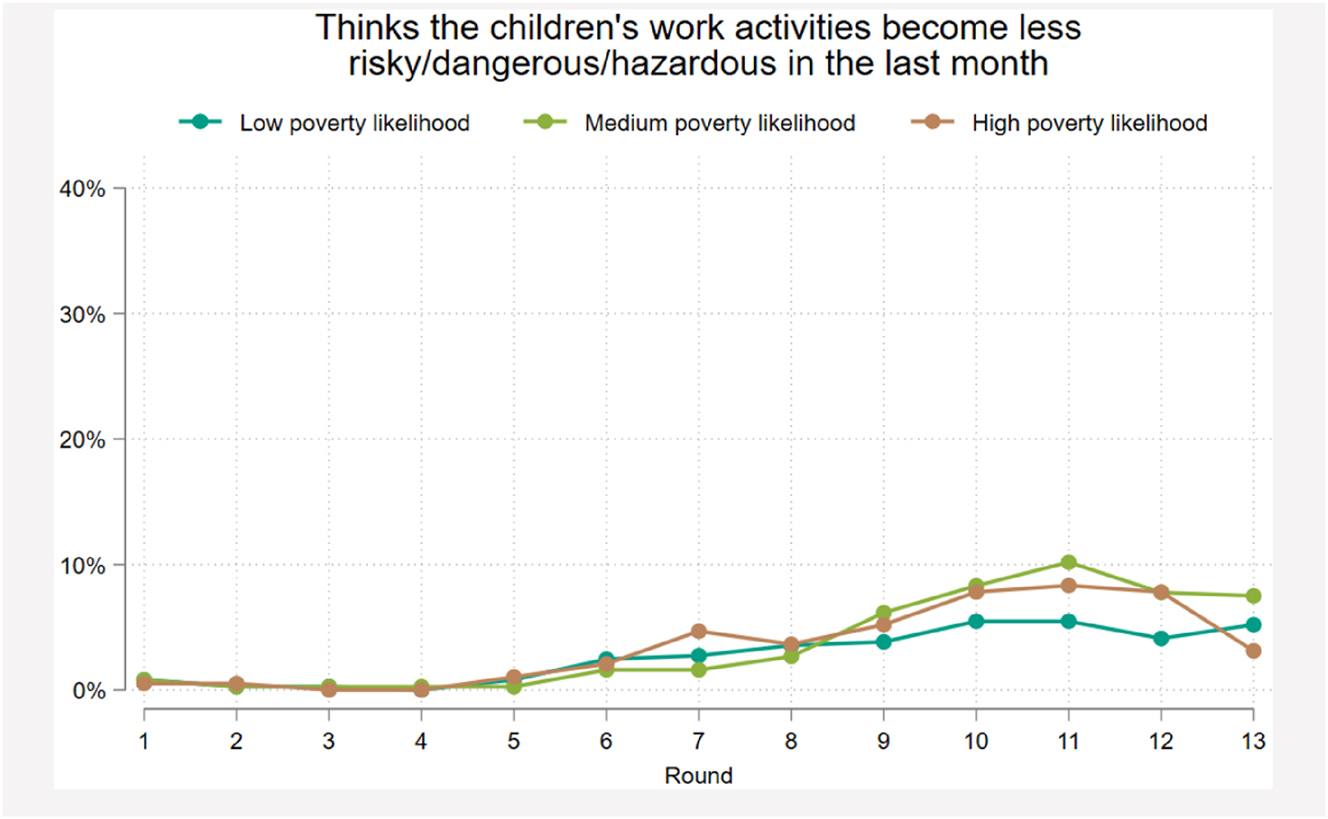

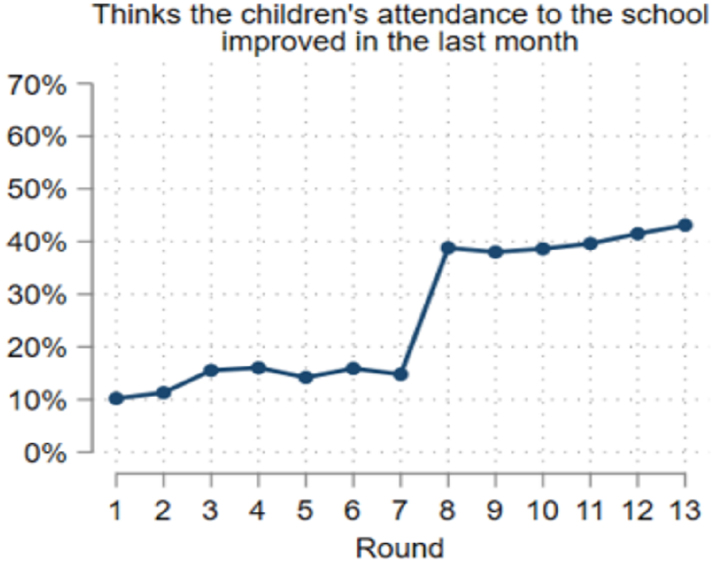

Perhaps unsurprisingly, in neither the Bangladeshi nor the Indian experiment did we encounter mass departures from the labour market. In India, where the lion’s share of participants made their incomes through a combination of challenging work including garbage collection, daily wage labour, and domestic work, we had hypothesised that the addition of UBI to people’s income pool may lead those who found their work challenging or undignified to leave it. However, surveys indicated no change whatsoever in overall employment rates – 52 % of respondents were in paid work at baseline and at endline, while fully 95 % of participants remained in the same employment across these time periods. In Bangladesh, where evaluation focussed in detail on the impact of cash on children’s work, we found marginal improvements in parents’ perception of child engagement in hazardous work. Trend data from our bi-monthly surveys showed an increase the percentage of parents who thought that children’s work had become less risky after the beginning of cash transfers in Round 8, which indicates that parents may have shifted children from more to less risky employment, yet even this change was only from 5 % to 10 % (see Figure 4).

Time-series analysis of perceptions of change of improvements in children’s working conditions.

Qualitative data add important nuance to this picture. In both India and Bangladesh, we found multiple individual cases of people changing jobs in part or wholly because of the support provided by the unconditional cash. In Bangladesh, one mother explained to the present authors that she had removed her son from the hard factory labour that he did before cash transfers started and instead put him in school alongside a less well remunerated grocery store job because of the wage replacement function performed by the cash transfer. Another used the incoming cash to set up a new business that afforded her significantly greater daily freedom. While a third swapped one factory job for another on account of the first treating her disrespectfully.

Which factors explain the relatively low overall numbers exiting employment? One possibility is that our thousands of participants generally enjoyed their work and would not have wanted to leave or change it. This possibility is undermined by the reems of qualitative data from both countries pointing to poverty and financial necessity as the determining factor in people’s work-lives. ‘We have no choice but to do this work’, was a common refrain in our focus groups, along with ‘What freedom do poor people like us have?’ Likewise, when asked what hopes people had for their children, parents in both countries identified education and subsequent, white-collar jobs like office work as the dream:

We are working so hard so they can go to study. Otherwise, they will also live a life like ours. (Woman, 36, Domestic Worker, Hyderabad)

This clearly undermines the hypothesis that people’s work was so desirable that even a UBI could not trigger them to change it. Alternative explanations are therefore required. Our data point squarely in the direction of three that speak directly to established critiques of the UBI and Exit thesis, namely: unavailable (superior) alternatives; the social embeddedness of people’s labour; and the insufficiency/impermanence of the UBI provided.

On the first point, it is important that the socio-economic contexts in which these experiments took place are both marked by poverty, marginalisation, and discrimination. In India, a majority of our participants made their livelihoods as garbage collectors, a fact heavily conditioned by their caste. All came from scheduled caste groups historically associated with dirt. As such, although in theory they may have been able to avail themselves of other low paying work, the social organisation of labour made waste work more readily available to them and made alternatives difficult to come by. Indeed, labour histories collected from our participants made clear that government agents had actually sought out these communities to become waste workers once the City Corporation re-organised its approach to waste disposal because of their historical caste association. From this initial opening, kin and caste networks played a role in bringing more such caste communities into the orbit of garbage collection. The following exchange with a mixed group of participants is instructive:

Interviewer: Everyone is here going to collect garbage only, right?

Many voices: Everyone here will go to do garbage collection, and some people will go to sell granite powder, sir.

Interviewer: Have you been discriminated against because of the work you do?

Man 1: Yes sir, we are looked down upon.

Man 2: Work is work, sir. Even those who study here end up doing garbage collection because no other work is available to them.

Woman 1: These days even young children are being sent to do garbage collection by their parents.

(FGD in P Community, Round 1)

Agency is evidently constrained by caste as well as class, but in neither India nor Bangladesh were our respondents entirely without freedom. Even amongst garbage collectors in Hyderabad, many articulated their decision to continue their work in the face of discrimination and constant body aches in terms of preference and choice as well as constraint. One 49-year-old male put his choice thus:

Here, there is no boss; I do my things. But in an office, even if you want to drink tea, you have to take permission from your boss… I used to be a mechanic. If you were two minutes late the boss would give you such abuse. Here [in garbage collection], I am in control.

(Interview in V Community, Round 1)

Garbage collectors across all four communities in Hyderabad cited autonomy and entrepreneurial freedom in their work and contrasted this with what is possible when one has a boss of any sort. Many also pointed to being able to make more money than in potential alternative employment. Work may be unpleasant, therefore, but for many it was better than the available alternatives, which UBI on the whole did not create.

A second reason explaining the limited overall level of exit within our communities surrounds what we think of as the social embeddedness of labour – in other words, the social, affective and other needs dependent on any given labour relationship. Domestic workers are a useful case in point. Primarily women within our Indian sample, they made up a substantial portion of the working population and valued the flexibility of their work, particularly as it allowed them to manage their domestic responsibilities. Their work began later than garbage collection and was split into morning and evening shifts, allowing them to juggle this and their social reproductive tasks at home. They also valued the relationships that they developed with employer families, who often provided non-cash benefits like food, old clothes, and toys. In Bangladesh, a close parallel to domestic work was home-based embroidery provided by nearby factories. This was preferred by many adolescent and adult women even in the face of more remunerative (and available) factory jobs because it enabled them to combine paid work with household responsibilities and protected them from the potential difficulties and shame associated with working in public and with men – an important consideration in this conservative, Muslim society.

Finally, we must also point to limitations inherent to the cash in both India and Bangladesh. In Bangladesh, cash transfers only ran for just over half a year, which is too short a time-period to underwrite anything like radical exit from the labour market. Various participants lamented the short duration of the cash component of the experiment and thus its limited impact:

Over 6 months, they gave us support. I got 3,700 taka every month through my Upay account. We used the money to cover our daily expenses, send our granddaughter to school, and get our basic needs met. During that time, their money was a lifeline, helping us through tough times…The only problem was that they gave us the money in small pieces over those six months. It was hard to plan for the future or make lasting improvements…When the program ended, we were back to struggling financially.

(Woman, 45, Round 3 Interview)

Yes, they stopped giving the money. If we kept getting it, things would be better for us. The family could be run better if we continued getting the money. For example, now my mother is working in different households as a maid, she earns 5,000 to 6,000 Taka. If she continues getting that money, then she could run her life better. Then she could move forward.

(Adolescent girl, Round 3 Interview)

In India, although the basic income was delivered over 18 months, its overall value – representing on average 25 % of household income – and its time-bound nature both factored into people’s considerations. This was perhaps most poignantly evidenced by the case of Zoya, an elderly woman living alone in one of our communities. Like a handful of other elderly widows, Zoya’s primary income came from seeking alms outside temples or mosques, from which she typically made Rs 2,000–3,000 monthly. Despite receiving the UBI, she chose to continue her alms-seeking. Not only did doing so provide her day with structure, purpose, and even a degree of community, but because her UBI was time-bound she chose to approach it as a way to put aside some savings, which she expected to need when the next health crisis inevitably hit. Poverty and the lack of wider structures of support are evidently crucial here in making sense of the limited impact of the cash.

7 Partial Exit

If cash was unable to trigger full or radical exit for many in India or Bangladesh, it nevertheless overwhelmingly enabled partial exit, understood as reduced dependence on undesirable work – for example through a reduction in work hours – and as the re-balancing of work and non-work time use – for example through increased schooling or leisure.

The first of these dynamics was particularly in evidence in India. Where, as the previous section noted, 95 % of respondents remained in the same employment at the end as at the start of the experiment, our data show far more substantial changes in the amount of time people worked. At baseline, 55 % of households worked 7 days a week, with a further 31 % of households working 6 days a week. By endline, these figures had shifted to 46 % and 41 % respectively – a net swing from 7 to 6 days among 9 % of households, representing close to a 20 % trend shift. Perhaps even more tellingly, though, at midline, halfway through the experiment, when 9 further months of basic income were still to be received, the number of households working 7 days a week had dropped as low as 38.6 %, with those working 6 days at 44 %. These are drastic reductions, and they point to the ability of basic income to increase people’s constrained freedom and make choices that serve their wellbeing which otherwise they would not have been able to make. Ramesh, a 62-year-old granite powder seller, leaves home at 6 am every morning, earning only on those days that he works. He said of the basic income:

Some days I wake up and my entire body is aching. I just can’t get up. These days I tell myself, “it’s okay. This money is coming. I can afford to not go to work”.

Rohit and his wife highlighted using the UBI to hire help for their garbage collection rounds. Garbage collection is typically a two-person job, since one person will drive the truck and the other will go to collect garbage from individual houses, shops and apartments. Collection is expected seven days a week. Being able to hire a helper gave them the flexibility to each take a day off a week and to attend to their caring responsibilities, with Rohit’s wife often starting the garbage collection round later after tending to their children:

Now my wife joins us later. This boy comes for garbage collection with me. She gets the children ready, feeds them and sends them to school. These days she also does some rag picking before joining us… That has also increased our income.

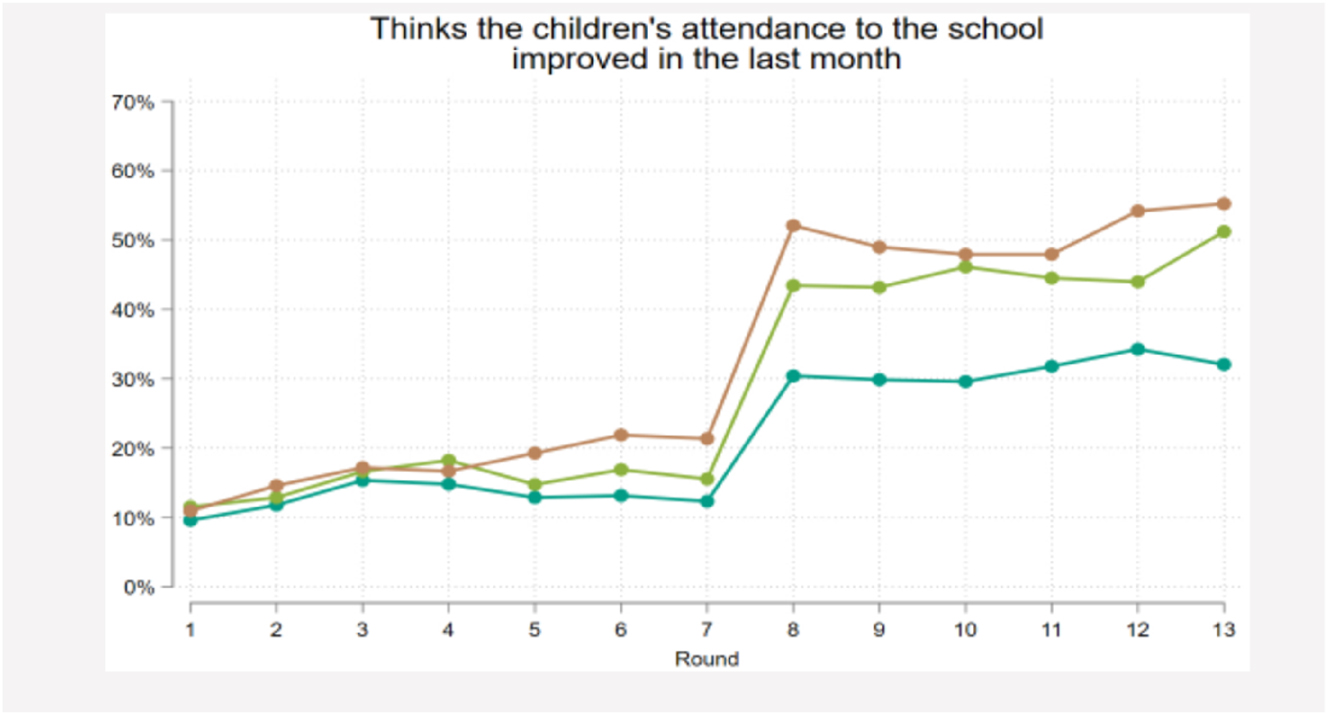

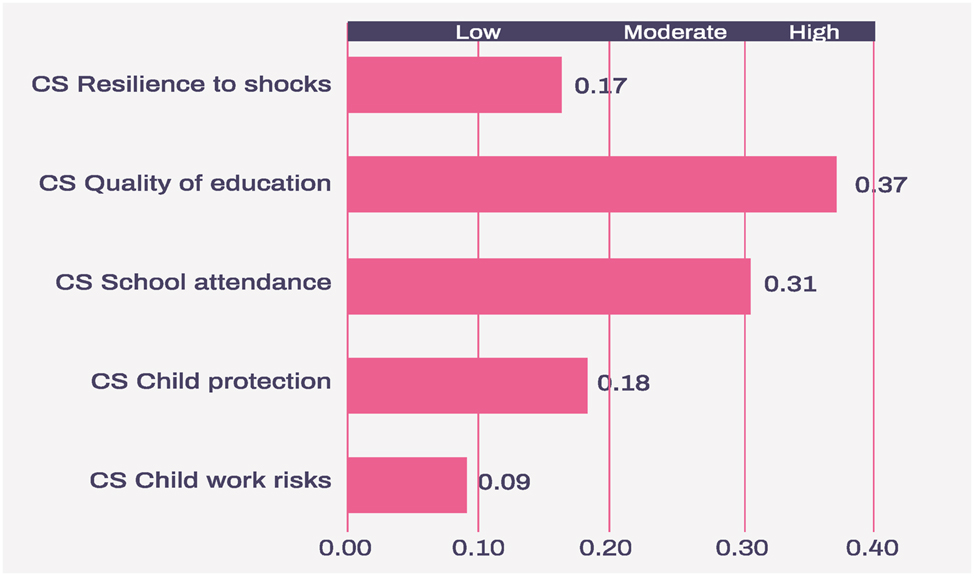

In Bangladesh, cash-enabled partial exit was most in evidence when it came to schooling and the replacement of children’s work with school attendance (Fig. 4). We noted above that a number of parents thought that their children’s work had become less hazardous after the beginning of the cash transfers, possibly indicating exit from undesirable employment. But the number of parents who reported improvements in school attendance was far more significant, as can be seen from Figure 5 below, with the spike also coming at the point of cash rollout (Round 8). Given that school is well established as the primary alternative to paid work for the young poor across the Global South (Bourdillon et al. 2010), this is an important outcome. Data also make clear that parents overwhelmingly attributed it to the impact of the cash. Figure 6 reports the contribution scores from respondent households. These estimate respondents’ assessment of the impact of the experimental intervention. Thirteen sets of questions were asked about perceived changes in outcomes (on a 1–5 Likert scale), followed by a question that asked how much the experiment influenced these outcomes (also on a 1–5 Likert scale). Following Ton et al (2023), both Likert scale answers were combined in contribution scores for each outcome, with contribution scores higher than 0.20 considered as moderate impact, and scores higher than 0.30 as high impact (Howard et al. 2024). Parents attributed improvements in school attendance and education quality to have been substantially impacted by the intervention, which qualitative data further confirm to have been one of the major uses to which cash transfers were put.

Time-series analysis of perceptions of improvements in children’s school attendance.

Reported cash transfer contribution scores.

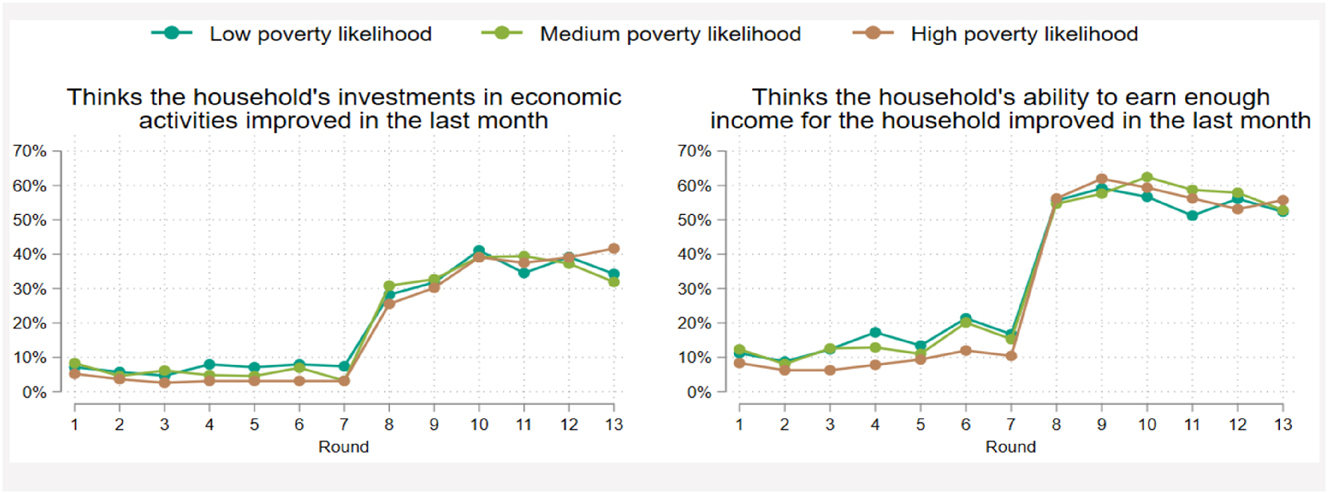

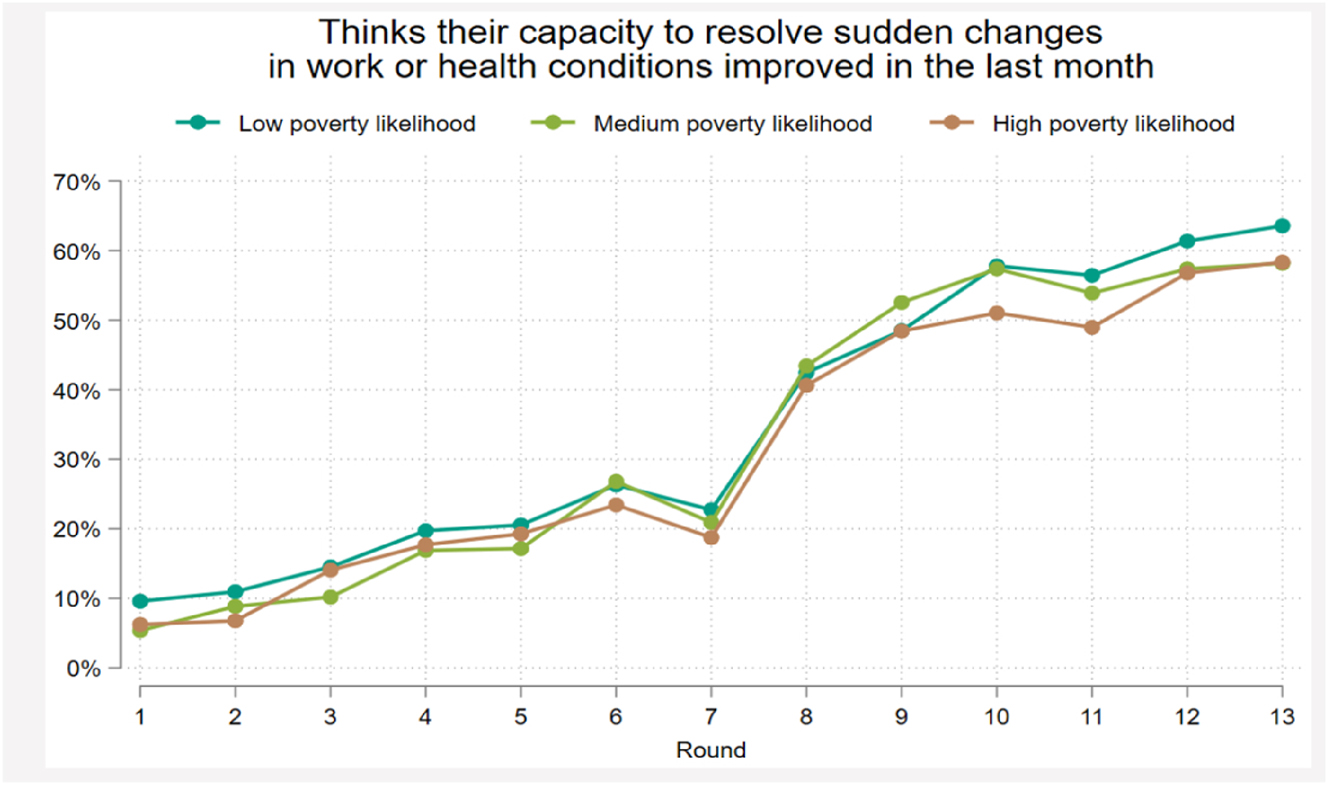

In interpreting these results, it is noteworthy that in each country the cash had a marked impact on people’s poverty. In Bangladesh, time-series data show a sharp jump in households’ perceived ability to earn enough income, to make investments, and to cope with shocks consistent with the onset of cash transfers (Figures 7 and 8 below). This trend data is backed by our qualitative findings:

I have received the cash transfer money and I have invested the money in my tea stall… As a tea stall owner, it is normal to have 500–1000 Taka debt. I also owe money from other people. I have invested all the cash transfer money in my tea stall.

(Male, 40, Tea Stall Owner, Round 2)

Speaking of if that money brought any changes or not, well, we bought cows by those money. We are rearing those cows now.

(Male, 17, Factory Worker, Round 2)

Poverty impact.

Perceived ability to cope with shocks.

In India, the basic income improved people’s poverty by helping them reduce their debt substantially. One male participant, Suresh, received Rs. 100,000 over 18 months when pooling his and his family’s basic income. ‘This is a huge amount for a poor man’, he said, ‘and it will help him clear his debts’. His analysis was supported by our quantitative data – 35 % of Indian recipient households paid off long-standing debts, with 88 % attributing this to the basic income. In places where financial margins are so tight, the extra resources provided by a basic income can be understood as enhancing financial capacity, which in turn impacts upon the conditions constraining any possibility of (partial) exit.

8 Voice

The third group of claims around the possible impact of UBI on labour exit surround the ‘voice’ element of Hirschmann’s seminal paradigm, specifically that the UBI can enable increased individual and collective bargaining power (both backed by the threat of exit) to improve working conditions. Various of our data speak to this point, but for the most part they do so indirectly, so this sub-section will build its case incrementally. The broad thrust of our argument is that people in our sample have agency that expresses itself in voice; this is not necessarily dependent on receiving UBI; yet there is ample evidence to believe that UBI is helpful for increasing both agency and its expression in voice.

To begin, let us note that, in Bangladesh, our data reveal multiple individual instances of workers advocating for their own interests and asking for better pay or conditions. Various of our teenage respondents reported asking for improved conditions, moving to better opportunities if these were not forthcoming, or planning to do so:

I wanted them to raise my salary, but they didn’t, that’s why I left that factory.

(Boy, 14, Factory Worker, Round 2)

I will probably change my job after getting my next salary, because I should be getting 10,000–12,000 Taka because of the machine I operate.

(Boy, 16, Factory Worker, Round 2)

Similarly, our data reveal cases where respondents chose not to leave a particular job but nevertheless demanded improvements within it. The following extract from an adolescent female factory worker is illustrative:

My supervisor is not that good, he behaves badly and scolds other girls in the factory but he never scolded me because I didn’t give him any chance to. Anybody can make mistakes, but scolding is not fair. One day, one of my colleagues cut her hand but the supervisor scolded her instead of taking care of her…Our boss is known to my father, and he has been good to us. One day, the supervisor scolded me too, so I went to the boss and he told the supervisor not to behave badly with any of this girls. “You have two daughters like them in your own house, try to behave well with them”, he said.

(Girl, 17, Factory Worker, Round 1)

It is likely that socio-economic circumstances were important in creating the conditions for such agency. The informal settlement where our experiment took place is large, diverse, and full of employment opportunities in the leather and garment sectors. In many respects, it characterises parts of the urban informal economy in South Asia, since it represents both a landing place for new migrants from the countryside and a home for more established residents, all amidst the constant churn of new and old businesses. This intersection means that work is readily available. Unsurprisingly, therefore, even though poverty constrains people’s freedom and limits their power, labour mobility and worker agency are relatively common even without the support of a UBI.

Yet our data also suggest that there is a plausible relationship between agency and the rollout of unconditional cash, since our quantitative findings show that cash had a major impact on people’s sense of control over their own lives. As can be seen in Figure 9 below, the percentage of respondents reporting a feeling of ‘being in control of one’s own life’ jumped from 30 % to over 60 % with the beginning of the cash. This was backed by a corresponding increase in people’s sense of being able to cope with unanticipated shocks, as illustrated in Figure 8. Both of these findings suggest that cash and the material security that it provides contribute towards the agency that lies at the heart of voice, even if this is not voice’s sufficient condition.

Feeling of being in control.

In India, the picture that emerges from our data is similar. That data speak clearly to the causal relationship between the basic income provided and positive psychological outcomes known to be vital for agency and voice, namely confidence, hope, and dignity (Arun 2007; Jütten 2017; Casassas 2024). Malam is a good example here. A daily-wage mason and painter, he found work solely through his contractor uncle’s networks. By the time of the midline interview, he was the sole earner within a family of five and had stopped working with his uncle due to conflict. Yet instead of depression and hopelessness, his interview was full of hope and ambition:

I want to start a partnership business by starting a small afternoon lunch stall. I have someone I know in that area. We want to start it. Both will invest half-half. They sell lunch in the afternoon on the roads, right…I have many plans in motion…

(Man, 23, Round 2 Interview)

When we asked why he was so hopeful despite his circumstances, Malam identified the basic income as vital:

…There is courage to take a step forward because of the money that we are receiving. If there is no such money, we would think multiple times before taking any such risk.

Malam’s words were echoed in a final round FGD conducted with a group of women participants in one of our settlements:

This money helps us in more than one way. Not just the daily expenses, or the hospital bills but also if we don’t have money in hand right now, just the thought that some money would come to us soon is enough of an assurance that helps us at least be confident and not to worry.

(Woman, 45, FGD Round 3)

This trend was paralleled by reports of increased dignity and self-worth as a result of the basic income. One male respondent put it thus:

At my work people never respect me. They call me different names. I have no other choice but to work. But this basic income recognises me as a human for any work I do. It takes care of my family.

(Man, 45, Garbage Collector, Field Notes)

Two women in one of our final FGDs put it similarly:

Woman 1: It felt good to receive this money. Even when we have emergencies. This money is helping us a lot. I am very thankful for it…It is also great that you are coming to meet us because most people distance themselves because we have a tag of being the garbage colony. People don’t like coming here. Thanks for coming here and for all the service.

Woman 2: Thanks for helping us. I feel good that you are coming and meeting us. Most people distance themselves from us because of our work.

This sense of dignity, of recognition, and ultimately of mattering, was reflected across all our participant communities and for some translated clearly into agency and voice. A group of young men who worked at function halls, for example, reported feeling empowered to say no to late-night shifts and heavy labour. In other cases, women domestic workers reported feeling emboldened to negotiate better wages and conditions in their workplace:

I said to them, if these people [delivering the basic income] can care for us and provide us help – I have been with your family for so long; won’t you care for my conditions?

(Woman, 42, Domestic Worker, Round 2 Interview)

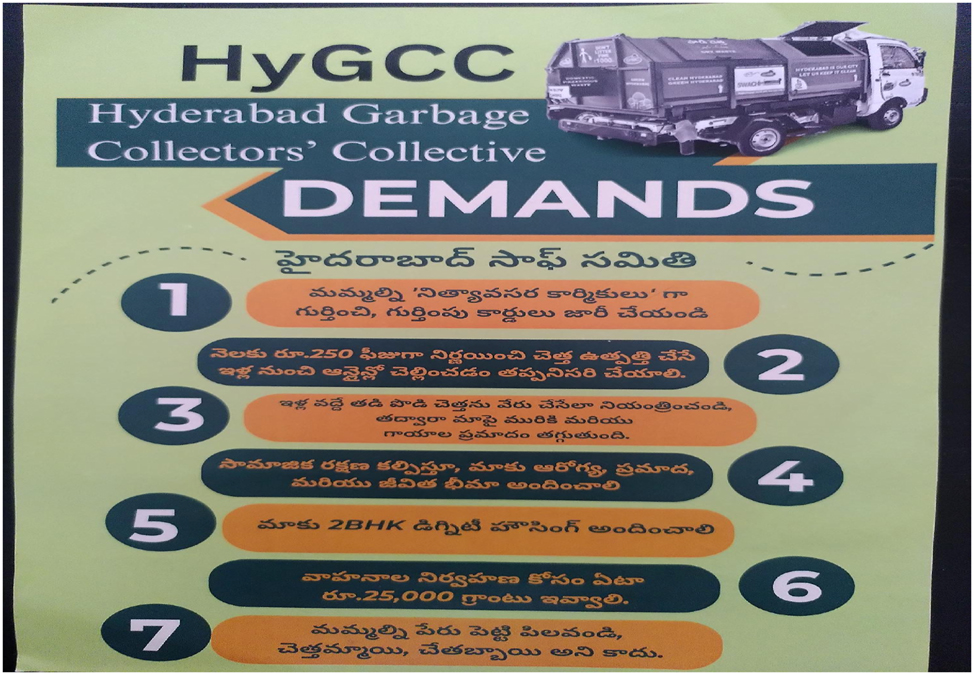

The impact of our two experiments on voice is most apparent, however, when it comes to collective rather than individual negotiating power. Nowhere was this more apparent than in India, where the experiment culminated in the establishment of HYGCC – the Hyderabad Garbage Collector’s Collective. Formed on November 5th, 2023, HYGCC brings together hundreds of garbage collectors across our participant communities and is led by a representative council comprised of an equal number of men and women from each. Their work is supported and facilitated by the community organisers who worked in these communities throughout our experiment (Figure 10). HyGCC’s demands – all presented to the City Corporation, to politicians at the time of the recent General Election, and to the press – include the following seven points:

Recognise us as Essential Workers and issue identity cards accordingly;

Fix Rs. 250 as a user fee per month to be paid by each waste generating household and make online payment mandatory;

Compel households to segregate waste into wet and dry. This mitigates the risks we face;

Ensure our social security with Health, Accident, Disability, and Life Insurance;

Provide us with housing under the 2 BHK Dignity Housing policy;

Provide an annual vehicular maintenance grant of Rs. 25,000;

Call us by our names and treat us with dignity.

HyGCC demands.

It is impossible to overstate how important a development the emergence of HyGCC is. Garbage collection in India is unpleasant, precarious work characteristic of the neoliberal semi-privatisation of state functions. Workers are allocated a particular set of neighbourhoods for which they are responsible and report to a City employee who nominally supervises their work. They are, however, independent operators, enjoying neither a contract with the State nor contracts with the households from which they collect the waste. This means that they are constantly required to negotiate payment with the households even as householders discriminate against them. They also face potential backlash from the supervisors to whom these households have the right to complain should they push back or refuse to collect waste in protest at ill-treatment. Their work is thus emblematic of neoliberal precarity and of their relative powerlessness within it. Moving to create an institution akin to a union and placing dignity at the heart of its demands is a major step.

Yet in analysing the emergence of HyGCC, it would be a mistake to overplay the role of the basic income. It will be recalled that our experimental design in both countries featured two intervention arms – unconditional cash and participatory forms of community organising. Our evaluation sought to explore the impact of each of these arms independently and in conjunction. The data on disaggregated impact comes from a mixture of in-depth observation, process tracing on the part of community organisers, and survey questions that sought to isolate cash and community organising effects. The quantitative material paints a mixed picture in relation to the role of the basic income in gestating HyGCC. For example, we asked survey respondents to rank the three most important impacts that the cash specifically had on their lives at midline and endline. In each case, family health, education, and nutrition came out on top – there was little mention of collective power. Similar things emerge from our qualitative data – overwhelmingly, respondents pointed to the material impact that cash had on their lives and to the wellbeing consequences associated with it.

This picture changes, however, when we look at the combination of cash and community organising. Notably, survey data suggest that fully 91 % of respondents in India believed that the intervention as a whole led to improved community relations, while 63 % claimed that it had enhanced their ability to raise concerns with public officials. These findings are confirmed by our qualitative data. Numerous respondents pointed to improved community relations generated by the community meetings that were wrapped around the cash, noting that these gave neighbours time and space to come together and get to know each other. From one of our final focus groups, three women had the following to say of the meetings:

Woman 1: We are getting awareness.

Woman 2: We are getting some wisdom.

Woman 1: We have learned how to negotiate. We are learning to behave properly… We know how to behave because of meetings.

Woman 3: We talk to each other after meeting. That talk is enabled by the meeting. We talk about our problems and we feel strong after the talk.

(Group of Elderly Women, Round 3 FGD)

Another explained that improved community relations translated into easier collective advocacy:

We have learned to talk to each other, and we have learned how to talk to others. Now we know how to raise our voices.

(Woman, 36, Garbage Collector, Interview Round 3)

Importantly, while these data suggest that the community organising was a necessary condition for the establishment of HyGCC, our observations indicate that alone it may have been insufficient. This is because the basic income laid essential foundations of trust in the community organisers and the community-building work that they were doing. As noted above, the basic income contributed to people’s dignity, in part because it implied recognition of their humanity and their struggles. Since it was associated with the community organisers, it positively inclined participants to collaborate with them in collective action like the establishment of HyGCC. As Rahul put it in our Round 2 interview: ‘There is a sense of trust that you help us in times of need.’ Rahul is now a garbage collector leader.

9 Discussion

The claims made around UBI and exit are amongst the most important within the entire canon of UBI theory. They represent a major point of attraction for those within liberal, republican, and even libertarian traditions (Birnbaum 2012; Casassas 2024; Zwolinski 2012). They are also central for advocates keen to mitigate or overcome the power inequities inherent to capitalist social organisation (Wright 2010). Yet these claims remain highly contested, and to date very few studies have been conducted which are able to lend empirical weight to the conversation. For this reason, the two experiments featured in this paper represent potentially important steps forward for theory and practice.

Their findings paint a mixed picture. On the one hand, they strongly suggest that ‘the basics’, as the sceptics would surely put it, matter decisively – that is, the amount and duration of any putative UBI will indeed be central to its emancipatory potential. The income substitution function of the unconditional cash delivered in India and Bangladesh mattered. For some, it was enough to remove children from difficult work; for many more, it was helpful, even inspiring, but far from sufficient to trigger wholesale life changes. This finding is broadly consistent with wider literature on the income substitution effects of cash transfers and unconditional benefits (De Hoop & Rosati 2014; Harman et al. 2016; Calnitsky & Latner 2017). Likewise, our findings suggest that the UBI thinkers who have highlighted permanence and non-withdrawability as intuitively important are, in fact, correct. Time horizons are important to people and there is a clear relationship between inter-temporal security and the willingness to take risks or invest in changes (Banerjee & Duflo 2012; Davala et al. 2015). In our case, participants recognised the time-bound nature of the experiments that they were part of and adjusted their behaviour accordingly. This is not to say that none made any changes because time horizons were too short; far from it. Yet we can reasonably assume that more people would have felt more comfortable making more changes were their UBI to have been permanent. The policymakers who eventually win the battle for UBI will also need to win the battle to keep it.

Context also counts in this conversation. The caveats detailed above pointed to the social embeddedness of labour as important for theorising the potential impact of UBI on exit, and our findings concur that this is vital. In India, in particular, where the social governance of labour is heavily mediated by caste, caste identity plays an important role in opening and closing doors of possibility (Breman et al. 2009). Likewise, gender, kin, and social networks (Doron & Raja 2015). We are not, it appears, all the perfectly substitutable, social actors beloved of neoclassical economics, nor can we slide seamlessly from one labour choice to another based solely on where the margins are greater. More prosaically, since the typical person has affective ties and reproductive responsibilities beyond simply themselves, navigating and maintaining these will matter when deciding whether to forego one job for another, even with the support of a UBI-shaped solid floor to stand on.

Taking this argument further, we once theorised that UBI might play a role in ending the various forms of ‘unfree labour’ targeted for eradication by the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 8 on Decent Work (Howard 2018). Building on Karl Widerquist’s famous articulation of ‘freedom as the power to say no’ (2013), we asked whether a UBI might represent precisely the foundational economic power necessary for the ‘unfree’ to say no to their would-be exploiters and yes to better work. Again, our data suggest that things may not be so simple. Although, in certain instances, unconditional cash did enable courageous choices and support people to move from worse to better employment, even where unfreedom is understood structurally and not interpersonally (that is, as the result of intersecting forms of oppression, rather than individualised forms of coercion), cash alone may be insufficient for people to cut loose. As LeBaron et al. have theorised (2018), the supply of ‘unfree’ workers is contingent not only on their poverty but also on the legal and social forces denying them access to the status of full personhood. Our findings confirm that these include identity-based sources of marginalisation and discrimination such as gender and caste, as well legal exclusions surrounding labour and mobility governance.

Yet for all these riders, our data are unambiguous that UBI can increase worker power. If we understand power as akin to Sen’s capabilities and thus broadly in the sense of ‘power to’ (Kabeer 2001; Alsop et al. 2006; Hughes et al. 2015), then having more money is self-evidently beneficial since it expands the scope of what people can choose to do. In our case, the influx of unconditional cash supported recipients to start new businesses, invest in their human capital, clear their debts, and, for many, simply take time away from drudgery to look after themselves and their relationships. Even if such minor improvements may disappoint the revolutionaries among us who invest in UBI the potential for ruptural transformation, they nevertheless matter for ordinary people, and they make a difference in lives lived at the margin.

But our data should also give hope to radicals. Not only did cash increase people’s power through decreasing their poverty; it also enhanced dignity, nurtured hope, enabled aspiration, and improved wellbeing. These are the affective bases of human agency. Self-efficacy and feminist theory are clear that dignity and well-being are central to the experience of ‘power to’ (Bandura 1997; Rowlands 1997, 2020), while Appadurai has famously argued that the ‘capacity to aspire’ is one of the key capabilities typically denied the poor through lack of resources or social stricture (2004; Scoones 2015). If material deprivation is known to limit long-term thinking and curtail the ability to imagine better futures (Hecht & Summers 2021), then UBI must by necessity be understood as a precondition of emancipation. André Gorz, one of the great theorists of hope (1989), eventually embraced UBI for precisely this reason, and our data offer an indication that he was right to do so.

This ties neatly into our final point – data from these experiments suggest that UBI could, under the right conditions and with the right accompaniments, help build collective worker power. Left critiques of UBI hold that it will undermine collective action by further atomising society (Coote & Yazici 2019), pit different categories of worker against each other (Birnbaum & De Wispelaere 2016), or reduce the material incentive to rebel (Dinerstein & Pitts 2021). All of these concerns make sense, and critical scholars and activists are right to take them seriously. But the findings from our experiments suggest that they may well be overblown. In India and Bangladesh, collective action of various sorts was enabled by UBI, with the relational, organising activities of community organisers able to build on the material and affective foundations laid by the provision of unconditional cash. This was especially notable in the emergence of HyGCC as a vehicle for garbage collectors’ communal voice. Such is the importance of this development that even if it is only one case study, and notwithstanding the fact that the UBI never operated as anything like a strike fund, it merits further enquiry. Indeed, it calls to mind Carole Pateman’s famous dictum that one of the more attractive things about a basic income may be its ability to enable political participation without ‘heroic efforts on the part of any citizens’ (2004: 96).

10 Conclusions

As we approach the end of the first quarter of the 21st Century, the social and labour protections established during the second half of 20th are creaking. In the face of rolling economic crisis, deepening ecological disaster, and ongoing challenges to democratic governance, informality and insecurity have come to characterise working life for the majority of people. This is the context in which calls for UBI are growing louder. Scholars, activists and now politicians are turning to UBI as a potential solution, imagining it as a response to the precarity at the heart of modern-day capitalism and as a potential brake on employer power. Theories of ‘exit’ are central to this turn, with the underlying assumption being that guaranteed economic security can strengthen workers’ positions by underwriting their ability to walk away from any given labour relationship or credibly threaten to do so. This assumption is hotly debated, and critics from the left and right argue that the claims made on behalf of UBI are overblown. The present paper offers a rare, empirically rooted contribution to this debate. We do not find evidence to suggest that UBI will be anything like a magic bullet, or that cash alone will tip the balance of class power. We also find that there are limits to what a UBI can achieve. However, it would be naive to conclude from these results that advocating for UBI is therefore pointless. Far from it. Our findings suggest that UBI can substantially improve people’s lives, enhance people’s power, enable at least partial forms of exit, and support the development of collective organisation. It also contributes substantially to increased wellbeing, dignity and agency. These developments alone make it worth fighting for.

Funding source: UK Department for International Development (DfID)

Funding source: European Research Council

Award Identifier / Grant number: No. 805425

-

Research funding: This work was funded by UK Department for International Development (DfID) and European Research Council (No. 805425).

References

Alsop, R., M. F. Bertelsen, and J. Holland. 2006. Empowerment in Practice: From Analysis to Implementation. Washington: World Bank.10.1596/978-0-8213-6450-5Suche in Google Scholar

Appadurai, A. 2004. “The Capacity to Aspire: Culture and the Terms of Recognition.” In Culture and Public Action, edited by V. Rao, and M. Walton, 59–84. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Arun, C. J. 2007. “From Stigma To Self-Assertion: Paraiyars and the Symbolism of the Parai Drum.” Contributions to Indian Sociology 41 (1): 81–104. https://doi.org/10.1177/006996670704100104.Suche in Google Scholar

Bandura, A. 1997. Self - Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. New York: Worth Publishers.Suche in Google Scholar

Banerjee, A., and E. Duflo. 2012. Poor Economics: A Radical Rethinking of the Way to Fight Global Poverty. New York: Public Affairs.Suche in Google Scholar

Birnbaum, S. 2012. Basic Income Reconsidered: Social Justice, Liberalism, and the Demands of Equality. New York: Palgrave.10.1057/9781137015426Suche in Google Scholar

Birnbaum, S., and J. De Wispelaere. 2016. “Basic Income in the Capitalist Economy: The Mirage of “Exit” from Employment.” Basic Income Studies 11 (1): 61–74. https://doi.org/10.1515/bis-2016-0013.Suche in Google Scholar

Birnbaum, S., and J. De Wispelaere. 2021. “Exit Strategy or Exit Trap? Basic Income and the ‘Power to Say No’ in the Age of Precarious Employment.” Socio-Economic Review 19 (3): 909–27. https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwaa002.Suche in Google Scholar

Bourdillon, M., D. Levison, W. Myers, and B. White. 2010. Rights and Wrongs of Children’s Work. New Brunswick and London: Rutgers University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Breman, J., I. Guerin, and A. Prakash, eds. 2009. India’s Unfree Workforce. Of Bondage Old and New. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Brugger, L., Davis, S., Elliot, D., Hamilton, L., Quick, A., Roll, S., et al.. 2023. In Her Hands: First Year Research Summary, Family Economic Policy Lab, Appalachian State University. https://appwell.appstate.edu/sites/default/files/ihh_year_1_report_2.23.24.pdfSuche in Google Scholar

Calnitsky, D., and J. P. Latner. 2017. “Basic Income in a Small Town: Understanding the Elusive Effects on Work.” Social Problems 64 (3): 373–97. https://doi.org/10.1093/socpro/spw040.Suche in Google Scholar

Casassas, D. 2016. “Economic Sovereignty as the Democratisation of Work: The Role of Basic Income.” Basic Income Studies 11 (1): 1–15.10.1515/bis-2016-0007Suche in Google Scholar

Casassas, D. 2024. Unconditional Freedom: Universal Basic Income and Social Power. London: Pluto Press.10.2307/jj.11033254Suche in Google Scholar

Coote, A., and E. Yazici. 2019. Universal Basic Income: A Union Perspective. Public Services International.Suche in Google Scholar

Daemen, J. 2021. “What (If Anything) Can Justify Basic Income Experiments? Balancing Costs and Benefits in Terms of Justice.” Basic Income Studies 16 (1): 11–25. https://doi.org/10.1515/bis-2021-0024.Suche in Google Scholar

Davala, S., R. Jhabvala, S. K. Mehta, and G. Standing. 2015. Basic Income: A Transformative Policy For India. London: Bloomsbury.10.5040/9781472593061Suche in Google Scholar

De Hoop, J., and F. C. Rosati. 2014. “Cash Transfers and Child Labor.” The World Bank Research Observer 29 (2): 202–34. https://doi.org/10.1093/wbro/lku003.Suche in Google Scholar

De Wispelaere, J., and L. Morales. 2016. “The Stability of Basic Income: A Constitutional Solution for a Political Problem?” Journal of Public Policy 36 (4): 521–45. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0143814x15000264.Suche in Google Scholar

Dinerstein, A., and H. Pitts. 2021. A World Beyond Work? Labour, Money and the Capitalist State Between Crisis and Utopia. Leeds: Emerald.10.1108/9781787691438Suche in Google Scholar

Doron, A., and I. Raja. 2015. “The Cultural Politics of Shit: Class, Gender and Public Space in India.” Postcolonial Studies 18 (2): 189–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/13688790.2015.1065714.Suche in Google Scholar

Gorz, A. 1989. Critique of Economic Reason. London: Verso.Suche in Google Scholar

Gorz, A. 2007. Ecologica. Kolkata: Seagull Books.Suche in Google Scholar

Gourevitch, A. 2016. “The Limits of a Basic Income: Means and Ends of Workplace Democracy.” Basic Income Studies 11 (1): 17–28. https://doi.org/10.1515/bis-2016-0008.Suche in Google Scholar

Gourevitch, A., and L. Stanczyk. 2018. “The Basic Income Illusion.” Catalyst 1 (4): 22.Suche in Google Scholar

Haagh, L. 2018. “Basic Income and Institutional Transformation.” In Basic Income and the Left: A European Debate, London: Social Europe, edited by P. Van Parijs, 78–88. London: Social Europe.Suche in Google Scholar

Harman, L., F. Bastagli, J. Hagen-Zanker, G. Sturge, and V. Barca. 2016. Cash Transfers: What Does The Evidence Say? An Annotated Bibliography. London: ODI.Suche in Google Scholar

Hecht, K., and K. Summers. 2021. “The Long and Short of It: The Temporal Significance of Wealth and Income.” Social Policy and Administration 55: 732–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12654.Suche in Google Scholar

Hirschman, A. O. 1970. Exit, Voice, and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Howard, N. 2018. “Abolitionist Anti-Politics? Capitalism, Coercion and The Modern Anti-Slavery Movement.” In Revisiting Slavery and Antislavery: Towards a Critical Analysis, edited by L. Brace, and J. O’Connell Davidson, 263–79. London: Palgrave Macmillan.10.1007/978-3-319-90623-2_10Suche in Google Scholar

Howard, N., K. Roelen, G. Ton, M. E Hermoza, S. Al Mamun, K. Chowdhury, et al.. 2024. CLARISSA Cash Plus Social Protection Intervention: An Evaluation, CLARISSA Research and Evidence Paper 12. Brighton: Institute of Development Studies.10.19088/CLARISSA.2024.008Suche in Google Scholar

Hughes, C., M. Bolis, R. Fries, and S. Finigan. 2015. “Women’s Economic Inequality and Domestic Violence: Exploring the Links and Empowering Women.” Gender and Development 23 (2): 279–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552074.2015.1053216.Suche in Google Scholar

Hum, D., and W. Simpson. 1993. “Economic Response to a Guaranteed Annual Income: Experience from Canada and the United States.” Journal of Labor Economics 11 (1, Part 2): 263–96. https://doi.org/10.1086/298335.Suche in Google Scholar

Jütten, T. 2017. “Dignity, Esteem, and Social Contribution: A Recognition-Theoretical View: Dignity, Esteem & Social Contribution.” The Journal of Political Philosophy 25 (3): 259–80.10.1111/jopp.12115Suche in Google Scholar

Kabeer, N. 2001. The Power to Choose: Bangladeshi Women and Labour Market Decisions in London and Dhaka. London: Verso.Suche in Google Scholar

Kangas, O., S. Jauhiainen, M. Simanainen, and M. Ylikännö. 2019. The Basic Income Experiment 2017–2018 in Finland Preliminary Results. Helsinki: Ministry of Social Affairs and Health.Suche in Google Scholar

Kappil, T., A. Jefferson, S. Gayen, and A. Smith. 2023. “My Kids Deserve the World”: How Children in the Southeast Benefit from Guaranteed Income. Boston, MA: Mayors for Guaranteed Income and Abt Associates. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/64f8b31cbb263222a1487bd6/t/65654cf43cb3cf6b8ffe99af/1701137653535/Child+Outcomes+Report_Digital_PREFINAL_Nov+27.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

Lazar, O. 2021. “Work, Domination, and the False Hope of Universal Basic Income.” Res Publica 27: 427–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11158-020-09487-9.Suche in Google Scholar

LeBaron, G., N. Howard, P. Kyritsis, and C. Thibos. 2018. “Confronting Root Causes: Forced Labour in Global Supply Chains, Beyond Trafficking and Slavery Series, Open Democracy.Suche in Google Scholar

Malm, A. 2016. Fossil Capital: The Rise of Steam Power and the Roots of Global Warming. London: Verso.Suche in Google Scholar

Mayne, J. 2012. “Contribution Analysis: Coming of Age?” Evaluation 18 (3): 270–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389012451663.Suche in Google Scholar

Pateman, C. 2004. “Democratizing Citizenship: Some Advantages of a Basic Income.” Politics & Society 32 (1): 89–105. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032329203261100.Suche in Google Scholar

Rowlands, J. 1997. Questioning Empowerment: Working with Women in Honduras. Oxford: Oxfam.10.3362/9780855988364Suche in Google Scholar

Rowlands, J. 2020. “Finding the Right Power Tool(S) for the Job: Rendering the Invisible Visible.” In Power, Empowerment and Social Change, edited by R. McGee, and J. Pettit, 152–66. Abingdon: Routledge.10.4324/9781351272322-10Suche in Google Scholar

Scoones, I. 2015. Sustainable Livelihoods and Rural Development. Warwickshire: Practical Action Publishing.10.3362/9781780448749.000Suche in Google Scholar

Srnicek, N., and W. Williams. 2015. Inventing the Future: Postcapitalism and a World Without Work. London: Verso.Suche in Google Scholar

Standing, G. 2012. “The Precariat: From Denizens to Citizens?” Polity 44: 588–608.10.1057/pol.2012.15Suche in Google Scholar

Standing, G. 2023. The Politics of Time: Gaining Control in the Age of Uncertainty. London: Pelican.Suche in Google Scholar

Ton, G., K. Roelen, N. Howard, and L. Huq. 2022. Social Protection Intervention: Evaluation Research Design, CLARISSA Research and Evidence Paper 3. Brighton: Institute of Development Studies.10.19088/CLARISSA.2022.004Suche in Google Scholar

Ton, G., F. van Rijn, and H. Pamuk. 2023. “Evaluating the Impact of Business Coaching Programmes by Taking Perceptions Seriously.” Evaluation 29 (1): 73–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/13563890221137611.Suche in Google Scholar

Van Parijs, P. 1997. Real Freedom For All: What (If Anything) Can Justify Capitalism? Oxford: Clarendon Press.10.1093/0198293577.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Van Parijs, P. 2015. “Real Freedom for All Women (and Men): A Reply.” Law, Ethics and Philosophy 3, 161–75.Suche in Google Scholar

Van Parijs, P., and Y. Vanderborght. 2017. Basic Income: A Radical Proposal for a Free Society and a Sane Economy. Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press.10.4159/9780674978072Suche in Google Scholar

Weeks, K. 2011. The Problem With Work: Feminism, Marxism, Antiwork Politics, and Postwork Imaginaries. Durham: Duke University Press.10.1215/9780822394723Suche in Google Scholar

West, S., and A. Castro. 2023. “Impact of Guaranteed Income on Health, Finances, and Agency: Findings from the Stockton Randomized Controlled Trial.” Journal of Urban Health 100 (2): 227–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-023-00723-0.Suche in Google Scholar

Widerquist, K. 2013. Independence, Propertylessness, and Basic Income: A Theory of Freedom as the Power to Say No. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.10.1057/9781137313096Suche in Google Scholar

Wright, E. O. 2006. “Basic Income as a Socialist Project.” Basic Income Studies 1 (1): 1–11. https://doi.org/10.2202/1932-0183.1008.Suche in Google Scholar

Wright, E. O. 2010. Envisioning Real Utopias. London: Verso.Suche in Google Scholar

Zwolinski, M. 2012. “Classical Liberalism and the Basic Income.” Basic Income Studies 6 (2): 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1515/1932-0183.1221.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.