Abstract

Understanding and changing household consumption behaviour are considered the core driving force of the economic growth of a nation. Vietnam’s economic growth is mainly driven by final household consumption, which constituted over two-thirds of GDP during the last three decades. This paper aims to provide a novel way to understand household consumption decisions in a developing country based on several different but inter-related economic hypotheses of household consumption behaviour. Using a three-wave balance panel dataset constructed from nationally representative Vietnamese household surveys, we find strong evidence to support the importance of the permanent income hypothesis, the life-cycle factor hypothesis and the precautionary savings hypothesis. However, there is no evidence for the sex ratio hypothesis. Addressing the shortcomings of previous studies, this paper confirms the entry and exit of formal sectors and agriculture are the oriental predictors of precautionary motives. Heterogeneity analysis suggests the effect is fairly stable across balance sheet characteristics but varies across consumption categories. Our results are robust to a variety of robustness checks. These findings highlight the importance of combining a wide range of proxies for job insecurity and uncertainty indicators to understand household consumption behaviour, thus providing a powerful test of consumption and savings theories in short panels. The implications of these findings also are discussed and proposed in this research.

1 Introduction and Overview

Vietnamese final household consumption constitutes around 66% of GDP during last three decades, suggesting that restoring consumption levels has become an increasingly important role in fostering economic development. However, the total household consumption rate has declined from 11.76% in 2012 to 7.14% in 2016, which is opposite to the increasing trend of the world average.[1] As a result, understanding how to promote the household consumption rate has caught particular attention among both academia and policymakers. Existing literature suggests understanding its sources in determining consumption-saving behaviour is vital for policy implications[2] and improving welfare.[3] However, although the analysis of household consumption behaviour has become one of the most popular subjects in economic theories (Chai, Rohde, and Silber 2015), the empirical results drawn from the aforementioned studies remain ambiguous.[4] Consequently, debates have emerged in both policy and academic circles about which economic theories are good predictors of household decision-making. To the best of our knowledge, to date, studies on household consumption decisions in developing countries have lagged far behind the developed ones due to limited available resources. Motivated by these facts, this paper contributes to the literature by filling this gap using the nationally representative household panel dataset from Vietnam. The outcomes from this study will contribute to empirical evidence and theories and help policymakers design more appropriate strategies.

Traditional theory of consumption behaviour starts from the life-cycle hypothesis (LCH) by Modigliani and Bumberg (1954), which indicates that income varies systematically over the household’s life-cycle, and households maximise their lifetime utility by saving in a working period. The principal qualification to Friedman’s (1957) permanent income hypothesis (PIH) posits that consumption in a given period is determined by the income over the entire lifetime but not by current income. This framework helps explain the effects of the variation in income and economic shocks on the households’ consumption-savings decisions. Specifically, when households face income uncertainty or risk aversion, their consumption is expected to be lower, as they would expect their permanent income to be reduced in the future. However, the empirical evidence using both micro and macro data is not conclusive (Willassen 1978).

As the traditional models failed to investigate the relationship between expected future income and current consumption and may not adequately capture consumption-saving behaviours, a modern theory generated by Carroll (1994) stated that current consumption solely depends on projected current income and is unrelated to the expected future income. He also showed greater earning uncertainty is associated with lower current consumption. Results are well explained by “buffer stock” models proposed by Deaton (1991) and Carroll (1992, 1997. Prudent consumers might consume more than their current income if they know their future income, whereas income uncertainty in the future results in “buffer stock” saving behaviours. Hence, precautionary savings is considered a buffer stock against uncertainty. The model predicted that prudent consumers will save if the wealth is below the target; thereby, consumption will exceed current income and wealth will increase. A recent branch of literature has introduced and tested the sex ratios hypothesis by Wei and Zhang (2011). A possible explanation is that due to less pressure in the marriage market, households with only female children are more likely to consume more than the others.

Given the central importance of these theoretical results and their effects, it is perhaps not surprising there are sizeable empirical studies focusing on the consumption behaviour in the presence of uncertainty that employed income uncertainty to understand household behaviour (e.g., Miles 1997; Guariglia and Rossi 2002; Dardanoni 1991; Menegatti 2007; Hahm and Steigerwald 1999; Dynan 1993). The other strand used job insecurity and aggregate consumption data (e.g., Guariglia and Kim 2004; Meng 2003; Benito 2006; Stephens, 2004; Carroll, Dynan, and Krane 2003; Lugilde, Bande, and Riveiro 2018; Pericoli and Ventura 2012). The third strand argued that different occupations are associated with different degrees of earning risks; thus, occupations of households are important factors in predicting household decisions (e.g., Fuchs-Schündeln and Schündeln 2005; Skinner 1988; Fisher 1956). In contrast, there is little evidence concerning the simultaneous effects of different but inter-related economic hypotheses of household consumption behaviour in holistic economic modelling. Further, household consumption decisions depend not only on the mean of income uncertainty but also behave differently regarding job mobility (Low, Meghir, and Pistaferri 2010) and adjusting for risk aversion between men and women (Eckel and Grossman 2008). However, the empirical relationship between job mobility and consumption behaviour is limited. Moreover, despite the numerous studies, there is no consensus about the strength of what is an appropriate indicator for job insecurity and uncertainty. This issue must be settled by a comprehensive empirical study.

To address these challenges, the approach used in this research goes beyond existing studies in six main aspects: First, it emphasises the need of a unified framework for consumption hypotheses that can decide household consumption behaviour incorporating a wide range of measurements. Second, unlike previous studies, the unique nationally representative surveys allow us to calculate the propensity of moving in and moving out of occupations, which might be a good indicator for testing the precautionary savings hypothesis. Hence, we pay significant attention to the effect of the propensity for entry and exit of formal occupations and the agricultural sector of individuals on several household consumption categories. Third, although empirical works examine the household consumption response to income insecurity, the aforementioned studies have previously ignored the heterogeneity effects across different household consumption categories and different subgroups. This paper performs the asymmetric effects on different consumption categories. Fourth, due to the nature of taking risk aversion, men and women tend to make different consumption decisions (Eckel and Grossman 2008). However, a key limitation of aforementioned works is they largely ignore the effects of income insecurity on different consumption categories and the nature of taking risks between men and women. Our paper makes an effort to examine precautionary motives of both household heads and spouses in terms of occupations. Fifth, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first attempt to understand what drives different household consumption categories’ behaviour at micro levels in a typical developing country. Finally, while the empirical results could be attributed to different measurement errors or unobserved individuals’ characteristics, the paper’s results are robust to the possibility of various measurements of consumption and econometric techniques.

Under such circumstance, this paper aims to quantify the roles of consumption theories on explaining household consumption behaviour. This is a pioneering effort to represent estimates of consumption functions for households that incorporate all these hypotheses explicitly into a holistic economic modelling. We begin this paper by evaluating permanent and transitory incomes. Following the concept of Musgrove (1979), permanent income is a function of observed individual characteristics. Standard works in macroeconomics obtained permanent income by estimating the effects of current labour income on a set of observable household characteristics (Benito 2006; Fuchs-Schündeln and Schündeln 2005; Guariglia and Kim 2004). Additionally, the permanent income hypothesis (PIH) and its intuition illustrate that consumption should not respond to income fluctuation over time. In other words, consumption is only determined by permanent labour income yet not current labour income, implying the effect of the marginal propensity to consume out of transitory income should be equal to zero. However, recent research in the consumption literature argues that strict conditions could not fit with the real dataset (Meng 2003; Paxson 1992). This would imply that it is important to use the relaxed assumption of the PIH. We extend empirical works by controlling a wide range of household characteristics and accept the weak version of the PIH. Our findings are therefore consistent with the view of the weak version of PIH. Institutively, Vietnamese households are capable of smoothing most categories of consumption over time. This is in line with the findings by Benito (2006), Meng (2003), and Miles (1997), who showed that households are able to even out consumption during difficult periods by savings and borrowings.

Our approach is also new because it contributes to addressing the shortcoming of previous studies in testing one of the most salient risks of the precautionary savings hypothesis. Low, Meghir, and Pistaferri (2010) argued that job mobility is an important indicator to measure employment risk, thus unmeasured job mobility leads to misleading estimates of self-insure and earnings variances reflecting risks. In the dynamic environment, households make labour reallocation decisions across occupations (McCaig and Pavcnik 2015, 2018). Our empirical analysis of precautionary responses to employment risks extends the literature on understanding how the prosperity of employment mobility affects consumption. In our environment, individuals with a riskier income have an incentive to move to other jobs in less risky occupations. We use unique microdata extracted from nationally representative labour force data to evaluate the propensity of individuals to move in and out of formal employment[5] and out of agricultural sectors. Further, the study addresses the concern that people might change their occupations due to their consumption. We had estimated the probability of exit and entry sectors through probit equations. Our results shed some new light on whether switching to lower-risk employment promotes higher consumption. Results confront implications of the precautionary motives. Our affirmative answer indicates that while increasing the predicted probability of moving into formal sectors leads to rising consumption, the opposite is true for the predicted probability of moving out of formal sectors. This implies that moving from informal sectors to formal sectors with lower income insecurity is associated with an increase in consumption.

Another feature of this paper is that Attanasio and Weber (2010) and Paxson (1992) proposed an empirical model to look at life-cycle factors where individuals have concave utility functions. In this field, the objective of this paper is to provide new estimates of how life-cycle factors influence household consumption. Our empirical strategy is to construct a proportion of children, proportion of elderly members and the life-cycle consumption profile of age effects variables to investigate how consumption varies as individuals get older and households with higher numbers of dependent members. We also take care to control for the effect of time and unobserved household characteristics. Wei and Zhang (2011) improved our understanding of household consumption and saving decisions under the unbalanced sex ratio hypothesis. Going beyond that, this paper provides new estimates of the size of households with all sons and households with all females across different consumption categories and different subgroups. Our choice is based on the reason that due to less pressure in the marriage market, households with all females tend to consume more and save less. This paper adds to the work on life-cycle factors and the sex ratio hypothesis by building on appropriate indicators.

Vietnam has unique features and has become an ideal candidate for understanding household consumption behaviour. Our empirical strategy requires the availability of high-quality consumption data at the household level over the period of interest. One of the largest nationally representative surveys is the Vietnam Households Living Standards Surveys (VHLSSs), based on a threewave balanced panel dataset. It is conducted by interviewers and data collected by the General Statistical Office (GSO) of Vietnam with technical assistance supported by the World Bank and the UN Statistics Division, making it ideally suited for this work. With the high-quality data, we are able to look at the changes in consumption over time in the presence of consumption hypotheses controlling unobserved time-invariant individual characteristics and time effects. The second advantage is that the market reform is launched by the Vietnamese government approach, which allowed private entrepreneurs to engage in the market (Migheli 2012). As a result, Vietnamese households are now more likely to face enormous uncertainty due to the dramatic change in socio-economic developments and structural reforms. This evidence raises several questions regarding the main determinants explaining household consumption behaviour. Further, unlike developed countries, although the prevalence of informal employment has been slightly declining—from 62.6% in 2012 to 62% in 2014 and 55.7% in 2016[6]—Vietnam still is characterised by the prevalence of informal employment. Hence, unexpected income shocks should have a significant influence on household consumption decisions.

The results of this paper highlight the importance of simultaneously examining four economic theories with a nationally representative panel dataset across different expenditure categories controlling sample selection biases, other potential bias sources and heterogeneity analysis. More precisely, a 1% increase in the long-run marginal propensity to consume out of permanent income leads to an increase of approximately 0.573% in total household consumption controlling for other theories, fixed effects and unobserved heterogeneity. However, the effect is higher for health expenditure while it is relatively similar for remaining categories of consumption except for the inability to smooth education expenditure. Most remarkably, the results confirm that the validity of the precautionary savings hypothesis heavily depend on the selected proxy of income uncertainty, as already indicated by Stephens (2004). In addition, our results support the argument that household consumption decisions merely depend on the household head characteristics, yet are not influenced by the spouse characteristics. Based on the validation of testing hypotheses, due to being unable to smooth their total consumption over time, the government should support various national savings or borrowing schemes to assist households living without their private households in overcoming negative shocks. At the same time, our findings suggest introducing initial financial supports for the shift of labour out of agriculture and moving out of formal occupations to cope with adverse economic shocks.

The remainder of the paper is organised as follows. The next section presents the theoretical framework. Section 3 presents the data and variables used, Section 4 describes methodology and econometric procedure and Section 5 reports empirical results and discussions. Section 6 discusses asymmetric analysis, Section 7 reports robustness checks, and the last section concludes with policy implications.

2 Theory and Literature

The PIH is the first possible theoretical basis for understanding household consumption behaviour. In the 1950s, Modigliani and Bumberg (1954) introduced the life-cycle hypothesis (LCH), which indicates that income varies systematically over the household’s life-cycle; households maximised their lifetime utility by saving in a working period. The principal qualification to the PIH of Friedman (1957) posits that consumption in a given period is determined by the income over the entire lifetime but not by current income. In other words, consumption depends not only on current income but also on past income and expectations of future income. According to Friedman, consumption does not respond to the changes in total income because permanent and transitory incomes are uncorrelated, and consumption is assumed to be a linear form of income. It is suggested that transitory consumption does not depend on transitory income (earning uncertainty), and the marginal propensity to consume is close to zero. Following the PIH, individuals are able to smooth their consumption by savings in the normal periods or borrowings in the face of transitory fluctuations in income. This framework helps explain the effects of the variation in income and economic shocks on the households’ consumption-savings decisions. Specifically, when families face income uncertainty or risk aversion, their consumption is expected to be lower, as they would expect their permanent income to be reduced in the future. However, the empirical evidence using micro and macro data is not conclusive (Willassen 1978). Therefore, it would be highly desirable to extend this approach to formally test whether households are able to smooth their consumption over their life-cycle.

Second, as the traditional models of the life-cycle/permanent income hypothesis failed to investigate the relationship between expected future income and current consumption, and may not adequately capture consumption-saving behaviours, Carroll (1994) stated that current consumption solely depends on projected current income but is unrelated to the expected future income. He also showed greater earning uncertainty is associated with lower current consumption. Results are well explained by “buffer stock” models, which are proposed by Deaton (1991) and Carroll (1997) and Carroll, Hall, and Zeldes (1992) and Carroll (1997). Prudent consumers might consume more than their current income if they know the future income; whereases income uncertainty in the future results in “buffer stock” saving behaviours, in which precautionary savings are considered buffer stock against uncertainty. The model predicted that prudent consumers would save if their wealth is below the target; thereby, consumption will exceed current income and wealth will increase. Carroll and Samwick (1998) showed this framework is empirically supported by both microeconomic and macroeconomic data. Another theoretical framework emphasises the importance in terms of uncertainty and risk aversion on household consumption. According to Giles and Yoo (2007), the determinants of consumer behaviour are decomposed into three components: the intertemporal substitution effect, the life-cycle effect and the precautionary saving effect. It can be predicted that the expected future variance of consumption shocks has a positive effect on consumption growth in the future because of an increase in saving rate.

This theoretical result has been empirically investigated by numerous papers. Given the magnitude and importance roles of household consumption on economic growth, identifying core factors driving household consumption has become one of the most popular topics recently (Chai, Rohde, and Silber 2015). However, most previous studies in this area have been motivated to examine the effects of income uncertainty on household consumption by considering the precautionary saving hypothesis. There are three main strands of literature. The first strand, which has attracted the attention of most researchers, directly measures income uncertainty from households’ incomes. Miles (1997) and Guariglia and Rossi (2002), measuring uncertainty by the residuals from earning equations, found a strong precautionary saving motive in Britain and the UK. Similarly, in support of precautionary savings hypothesis, Dardanoni (1991) and Menegatti (2007) approximated income uncertainty by the variance of labour income in the UK and Italy, respectively, and Hahm and Steigerwald (1999) measured uncertainty through the conditional standard deviation of income in the US. However, Dynan (1993), measuring uncertainty by the instrument variables of the variance of income change in the US, argued that precautionary saving motives fail to predict household consumption behaviour. However, these analyses face significant measurement and methodology issues, particularly regarding the quality of income uncertainty data. The second strand of literature, which used job insecurity as a proxy for individual uncertainty, produced contradictory results. Using the probability of job loss to measure income uncertainty in Russia, Guariglia and Kim (2004) found evidence of precautionary saving motives. In addition, Meng (2003), using data on China, found the predicted probability of being unemployed negatively affects household expenditure. However, using both unemployment risks and the predicted probability of job loss in Britain to measure uncertainty, Benito (2006) obtained different conclusions: while unemployment risks do not impact household consumption, increasing the predicted probability of job loss decreases consumption.

Conversely, measuring uncertainty by expectations of future job loss, Stephens (2004) concluded that precautionary saving motives do not exist in the US, while using job loss shows contradicting conclusions. Carroll, Dynan, and Krane (2003) tested the precautionary saving hypothesis in the US and found little evidence to support this hypothesis. Further, Lugilde, Bande, and Riveiro (2018), using different sources of uncertainty, showed the magnitude sign effects of uncertainty on household consumption heavily depend on the selected proxy of income uncertainty. Producing an alternative measurement of uncertainty in Italy, Pericoli and Ventura (2012) found the probability of marital splitting has powerful and negative effects on current consumption, which supports the precautionary saving motives. However, attempts to test the precautionary hypothesis have met with mixed findings.

Additionally, occupations of households are essential factors in predicting household decisions. Different occupations are associated with different degrees of earning risks. Hence, people with risker occupations might save more and consume less. For example, individuals who work for governments as civil servants might consume more and save less than others because the former face lower job uncertainty and have long-term contracts. To support this, Fuchs-Schündeln and Schündeln (2005) found that civil servants, who have low-risk occupations, have significantly lower financial wealth than non-civil servants with higher risk aversion in Germany and confirmed the existence of precautionary savings. Additionally, Skinner (1988), empirically examining the importance of precautionary savings based on different occupations of household’s head as a proxy of uncertain earning in the US, found that service workers and labourers have low average saving rates, suggesting the lower degree of earning risks lead to low average saving rates. These results are consistent with the precautionary saving hypothesis. However, while Fisher (1956) concluded that managers saved 12% less than self-employed people, Skinner (1988) showed farmers and the self-employed likely had low saving rates. One of the potential problems is the selection of occupations. Individuals with more risky occupations have an incentive to move to other jobs in less risky occupations. Our empirical approach attempts to avoid the potentially biased selection of occupations by considering different types of occupations. More precisely, we consider different behaviour between households that have a member working as civil servants and others because this type of job will be selected by governments. The paper also calculates the probability of entry or exit of formal occupations.

Overall, the previous attempts to test the precaution saving hypothesis related to consumption mainly concentrated on developed countries and produced mixed or inconclusive conclusions. Additionally, due to the nature of taking risk aversion and different personality traits, men and women tend to make different consumption decisions (Eckel and Grossman 2008; Mangiavacchi, Piccoli, and Rapallini 2021). However, previous empirical studies have ignored whether women with lower occupational risks are more likely to consume more than those with higher risks. Our paper makes an effort to examine the precautionary motives of both household heads and spouses in terms of occupations.

Another predictor of household consumption behaviour is life-cycle factors. Parents are expected to receive support from their children as they get older or retire; thus, they would be willing to invest more in their children (Paxson 1992). This is also confirmed by the fact that almost elderly people choose to live with their family when they retire. For life-cycle patterns, the nexus between consumption, income and age follows an inverted U-shape or a hump shape, whereby both consumption and income increase during the first part of the life-cycle profiles, then reach a peak before decreasing as people get older. This explanation does not appear to align with the life-cycle profiles, where Attanasio and Weber (2010) showed that both income and consumption would become much flatter as households become older. Considering the importance of life-cycle factors in explaining household decisions, the higher number of children and elderly people are expected to negatively impact consumption, according to Paxson (1992). It has been posited that the age of individuals’ variables is a more powerful predictors in understanding consumers’ decisions. Attanasio and Weber (2010) utilised the life-cycle model to explain that individuals have concave utility functions, and therefore only unanticipated permanent income changes cause a change in consumption. They also provided strong evidence that there is an invested U-shape relationship between the age of the household head and consumption and income. This was also found by Fernández-Villaverde and Krueger (2007) and Gourinchas and Parker (2002), yet a contradicting result is found by Gertler, Levine, and Moretti (2009).

Finally, a recent branch of literature has generalised the importance of the sex ratio hypothesis. Differing from traditional predictors of household consumption and savings decisions, Wei and Zhang (2011) introduced and tested the sex ratios hypothesis. Specifically, to take comparative advantage in the marriage market, Chinese parents with a son need to accumulate assets to improve their chance of their child getting married. Therefore, a possible explanation is that due to less pressure in the marriage market, households with only female children are more likely to consume more than others. In addition, Vietnam is one of the East Asian countries in which the roles of family members are clearly defined due to social norms, whereby parents have a social responsibility to take care of their children and elderly members. Hence, a household with more children or elderly people is more likely to consume more and save less. The shortage of females in Vietnam would have resulted from the government’s population policy, known as a one-or-two child policy established in 1989. Therefore, sex-selective abortions are a problem in Vietnam (Bélanger and Oanh 2009). Similar to China, households with all sons are more likely to consume less and save more to have an advantage in the marriage market. Conversely, after getting married, a woman tends to move to live with her husband’s family to take care of elderly people, as sons are expected to take responsibility and care for their parents in old age as a social norm. Therefore, households with all female children tend to save more and consume less to smooth their consumption in their older age. All these characteristics make Vietnam a unique and interesting subject to explore. Our expectation is that households with all female children are more likely to consume more than those with all male children.

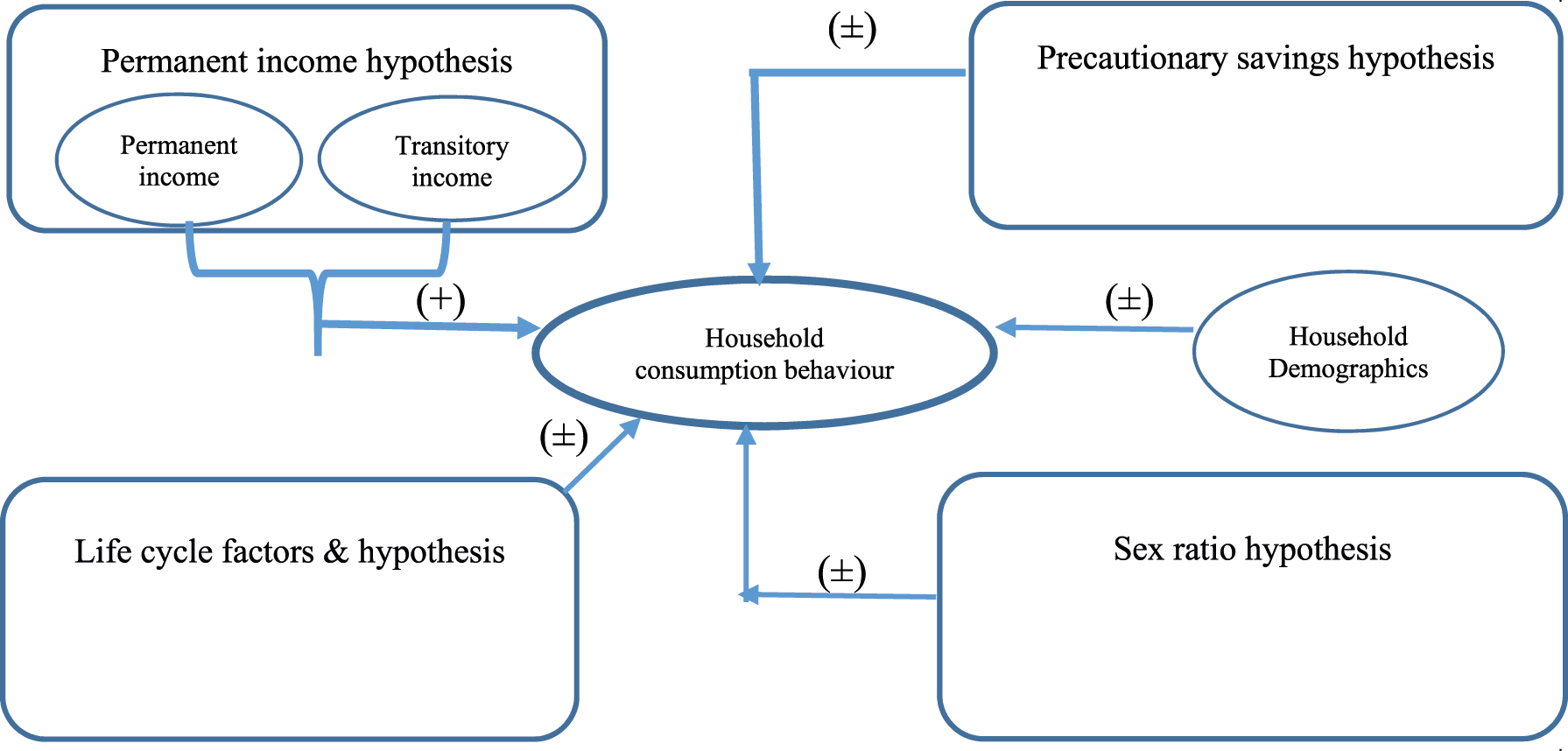

By summarising all the discussions above, it can be seen that household consumption behaviour might be predicted by a variety of consumption theories, which mainly forces on precautionary saving motivations, PIH, life-cycle factors and the sex ratio hypothesis. Our empirical study relies heavily on theoretical predictions of the consumption-savings decisions. In the concept of precautionary savings, the economic theory predicts that households with precautionary motives will consume more when future income uncertainty is lower. Hence, to empirically estimate the effects of income uncertainty on consumption decisions, it is important to know how to measure uncertainty. According to the standard Euler equation, the variance of consumption shocks as a proxy of uncertainty is related to the expected consumption growth. However, Hahm and Steigerwald (1999) argued the sign of the coefficient in the Euler equation is unclear. In this paper, besides the job loss in the next 12 months, we propose the alternative indicators of occupational insecurity, which is the most important source of income uncertainty. This suggests households might postpone their consumption when they work in high-risk occupations. Besides, the permanent income hypothesis predicts that consumption in a given period is not determined by income in that period (transitory income) but by income over their entire lifetime (permanent income). Additionally, the sex ratio hypothesis is another predictor of household consumption decisions, requiring further explanation since it is rare in Vietnam. Finally, the life-cycle factors hypothesis attaches significant importance to predicting household decisions, since different countries with different cultural and social norms might consume more or less. Considering these hypotheses, a hypothesis framework incorporated with factors affecting household consumption decisions is displayed in Figure 1. However, the effects of different indicators based on different theories maybe not be obvious and need further confirmation.

The hypothesis framework of household consumption behaviour.

3 Data Description and Variables Used

3.1 Data Sources

In this research, we use the VHLSSs, a national household survey conducted by Vietnam’s General Statistics Office with technical support from the World Bank. The nationwide surveys were designed to be significantly representative, both at core module topics and national levels. The dataset contains a wide range of information on the living standards of all social societies that can be used to obtain nationally representative summary statistics. However, it should be noted that while the survey consists of detailed information on household consumption categories, it does not collect information related to individuals’ consumption. Therefore, it is reliable to evaluate the impact of earning uncertainty on consumption at household levels. From 2002, the national survey has been carried out every two years. Households were interviewed bi-annually with various questions regarding ages, genders, educational levels, income sources, consumption categories, assets, health, and remittance both in domestic and international sources.

This paper uses the largest sample size of cross-sectional household surveys in 2016, 2014 and 2012. The sample size for the VHLSS 2012, the VHLSS 2014, and the VHLSS 2016 is 9399 households from 3130 communes. For each year, we have cross-section data of households. We also construct balanced panel data to have a comprehensive view of whether the relationship between consumption and income uncertainty has changed over time. The sample starts from 2012, which has a higher sample size but there are no government policy interventions during these periods. These surveys contain rich information on household consumption categories because of their comprehensive measure of household consumption expenditures and the wide range of socio-economic backgrounds of households. Further, using micro data set allows us to directly test whether households facing income uncertainty behave following the theoretical prediction in terms of changing their consumption. To overcome sample selection bias in sample selection, we consider labour force participants and thus exclude households where the household head’s age exceeded 60 years old or retired if they are male and 55 years old if they are female, in accordance with labour laws in Vietnam. We also exclude households in which all members are elderly people or children. The families with a negative total income, which might come from measurement errors, are also eliminated from our analysis. We use balanced panel data from 2012 to 2016 for a comprehensive view. It is emphasised that 50% of households will be interviewed in the next round. Therefore, we will have around 2500 households interviewed in 2012, 2014 and 2016.

3.2 Measurement of Variables and Data Description

3.2.1 Household Consumption

First, our measure of household consumption is obtained directly from the total household expenditure of all goods and services. However, evidence from previous studies (e.g., Dynan (1993) for non-durable and services consumption; Stephens (2004) for total household expenditure; Meng (2003) for total household expenditure, food consumption and educational expenditure; Guariglia and Rossi (2002) for food and groceries; and Lugilde et al. (2018) for non-durable goods) indicates that changes in durable goods consumption or food consumption do not closely relate to change in total consumption. Therefore, we also categorise total household purchases into a wide range of household expenditures to explain the income uncertainty effects on particular expenditures, such as non-durable goods consumption and durable goods expenditure, education expenditure, health expenditure, food consumption and non-food consumption. The paper uses household consumption rather than household income data for two appropriate reasons: (1) because the purpose of this study is to examine how economic theories work in explaining household consumption behaviour; and (2) data on household consumption is often easier to obtain than income data as there are many inherent problems calculating and defining household income in developing countries like Vietnam. For example, it is difficult to measure income from self-employed workers in agriculture and aquaculture, where a large proportion of labour participation is taken into account. Considering the potential non-normality of household consumption categories and heteroskedasticity, all variables were transferred to natural logarithms in the regression.

3.2.2 Precautionary Motives

Job loss represents one of the most important sources of uncertainty that households face. We used both household head and spouse not working by the self-reported unemployment responses for 12 months. However, it is only an indicator that captures the true employment status of main household earners. The second measurement affecting precautionary motives as occupational indicators follows and extends the approach of Fuchs-Schündeln and Schündeln (2005), Lugilde, Bande, and Riveiro (2018), and Skinner (1988). This is because different occupations are significantly associated with different degrees of earning risks. Regarding different occupations, manual labour and low-skilled workers have the highest income uncertainty compared with the other occupations. Waged employees have the lowest income uncertainty followed by self-employment in agriculture and self-engagement in the non-agriculture sectors. Further, civil servants, who face the lowest income risk compared to other jobs have significantly higher consumption than households in other occupations. Besides, to have better occupational indicators, we added not only a variety of occupations of the household head but also included the occupations of spouses due to the natural difference of taking risk aversion between males and females. Unlike previous studies, the unique nationally representative surveys allow us to calculate the propensity of moving in and out of occupations, which might be a good indicator for testing the precautionary savings hypothesis. In our environment, individuals with a riskier income have an incentive to move to other jobs in less risky occupations. Hence, we pay significant attention to the effect of the propensity for entry and exit of formal occupations and agricultural sector individuals on several household consumption categories.

3.2.3 Permanent Income and Transitory Income

The predicted values represented permanent income from the household income equation, where the household income equation is a function of demographic and social-economic characteristics of households. Then, the difference between the actual household income and permanent income is transitory income. Notably, we used the weak version of PIH in our empirical findings.

3.2.4 Life-Cycle Factors

As previous mentioned, the proportion of children and proportion of elderly people were used in this research, which is considered a situation of uncertainty regarding life span, as parents are more likely to invest in their children as the means of accumulating their expected future assets. Additionally, this paper mainly used the age of household head and age squared of household head to examine the LCH. Although examining the LCH can use many forms of age-specific relationships influencing individuals’ behaviour, as expected, our present interest focuses on the negative sign of the square of the age of the head of household variable.

3.2.5 Sex Ratio Indicators

Wei and Zhang (2011) stated that with less pressure in the marriage market, households with only female children are likely to consume more and save less. Following their approach, we used two dummy variables—households with all female children and households with all male children—as a proxy for the sex ratio hypothesis. Our explanation is that families with all females are likely to consume more than others.

3.2.6 Control Variables

To investigate the effects of income uncertainty on household consumption in Vietnam, we followed, extended and developed empirical modelling from Benito (2006) in Britain, Lugilde, Bande, and Riveiro (2018) in Spain, Miles (1997) in the UK and Meng (2003) in China by incorporating a series of potential determinants. The following control variables are used: health insurance of household head and home ownership, household assets, living areas, and number of years of schooling. The reasonable selection of variables in this research is based on a wide range of empirical studies that we consider potential control variables, which influence household consumption behaviour.

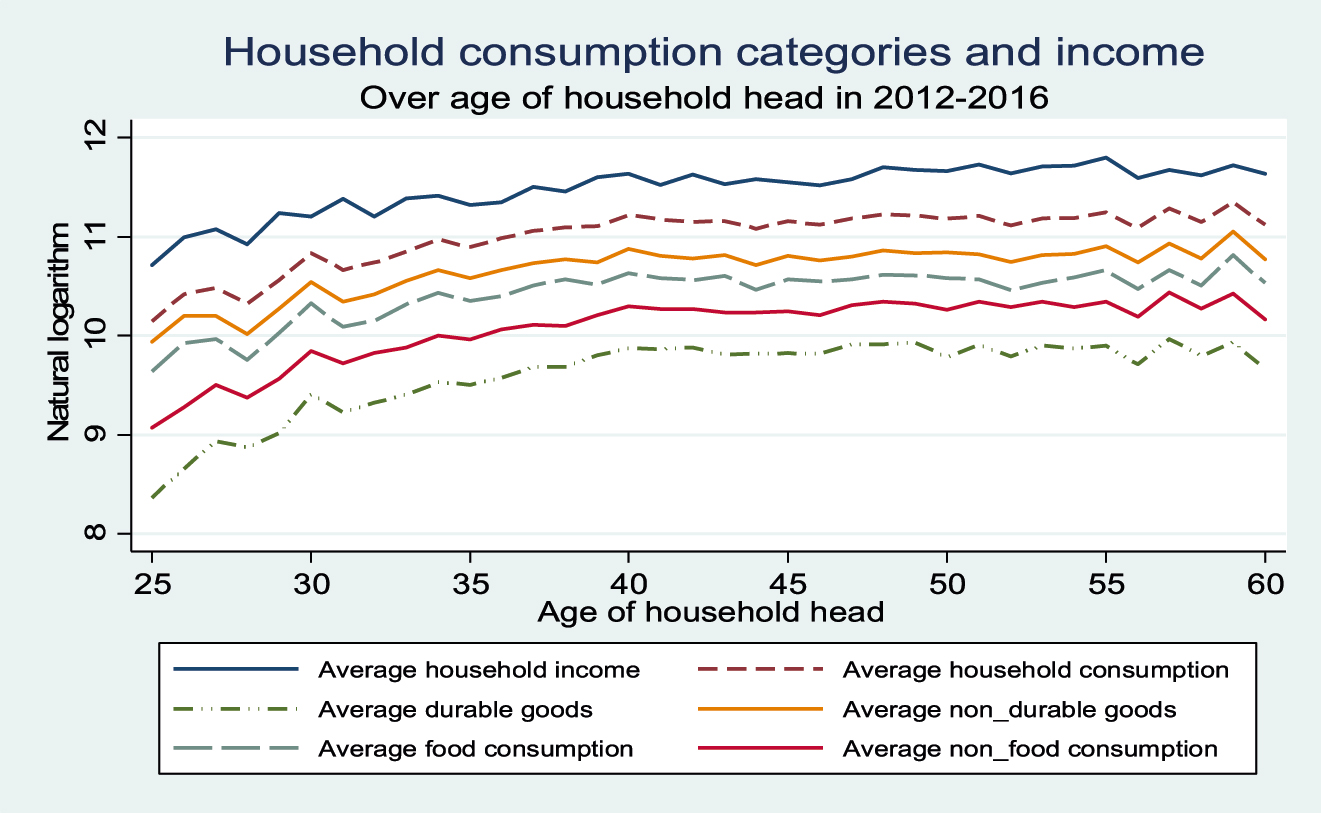

The information on the data description across different samples is shown in Table 1. Following Figure 1, Table 1 provides summary data from Vietnamese surveys of the different consumption categories and households’ characteristics for a balanced panel data running from 2012 to 2016. It is noted that all numbers in the table are in thousand VND. As seen from the table, the average amount of total household consumption expenditure was 84506.44 thousand VND. In terms of the life-cycle factor, Figure 2 shows that when the household head gets older, both income and consumption grow smoothly. Further, while income and consumption of households have more fluctuations in 2016 when people get older, these trends gradually increase as household heads get older. All household consumption categories and income of households are relatively stable at the end of retired ages.

Summary statistics for characteristics of the Vietnamese households.

| Indicator | Variable type | Mean | Std. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total consumption | Cont | 84,506.44 | 73,209.99 |

| Durable goods | Cont | 23,861.55 | 31,324.37 |

| Non-durable goods | Cont | 60,644.88 | 54,488.96 |

| Food consumption | Cont | 48,814.33 | 47,277.34 |

| Non_food consumption | Cont | 35,692.11 | 39,079.43 |

| Occupation position of household head | Ordinal | 2.7001 | 0.4957 |

| Occupational situation of household head | Ordinal | 2.7399 | 1.2038 |

| Employment status of head of household | Binary | 0.0687 | 0.2529 |

| Working in economic sectors of household head | Ordinal | 3.0979 | 0.9534 |

| Household head being not working | Binary | 0.9637 | 0.1871 |

| Occupation position of spouse | Ordinal | 2.7126 | 0.4625 |

| Occupational situation of spouse | Ordinal | 2.8122 | 1.1277 |

| Employment status of spouse of household | Binary | 0.0613 | 0.2399 |

| Working in economic sectors of spouse | Ordinal | 3.3980 | 0.8243 |

| Spouse of household being not working | Binary | 0.8372 | 0.3693 |

| Proportion of children | Cont | 47.1773 | 49.2792 |

| Proportion of elderly | Cont | 3.8691 | 14.4926 |

| Household with all sons | Binary | 0.2709 | 0.4445 |

| Household with all daughters | Binary | 0.1892 | 0.3917 |

| Household income | Cont | 13,9222.1 | 12,8086.1 |

| Household asset | Cont | 39,117.43 | 90,158.75 |

| Age of household head | Cont | 44.2806 | 8.3904 |

| Family size | Cont | 4.0000 | 1.3449 |

| Ethnicity | Binary | 0.7852 | 0.4107 |

| Gender | Binary | 0.8638 | 0.34302 |

| Proportion of unhealthy | Cont | 29.5108 | 57.3660 |

| Marriage status | Binary | 0.9055 | 0.2925 |

| Location | Binary | 0.2916 | 0.4546 |

| Number of years schooling | Cont | 7.6428 | 3.5159 |

| Educational levels of household head | Ordinal | 3.3753 | 1.1490 |

| Home ownership | Binary | 0.9756 | 0.1543 |

| Living area | Cont | 81.2789 | 49.2960 |

| Poor | Binary | 0.1197 | 0.3247 |

| Educational levels of spouse | Ordinal | 3.2999 | 1.4367 |

| Health insurance | Binary | 0.5875 | 0.4924 |

| Red river delta | Binary | 0.1940 | 0.3955 |

| Northern midlands and mountainous | Binary | 0.2306 | 0.4213 |

| North Central Coast | Binary | 0.1038 | 0.3051 |

| South Central Coast | Binary | 0.1140 | 0.3179 |

| South East | Binary | 0.0953 | 0.2937 |

| Mekong river delta | Binary | 0.1787 | 0.3832 |

| No. Obs | 3525 |

-

Using GDP deflator from World Bank Indicators to obtain real consumption and income in panel data with 2012 being the base year, all data are calculated from the VHLSSs 2012, 2014 and 2016.

Household consumption and income over age of household head in 2012–2016.

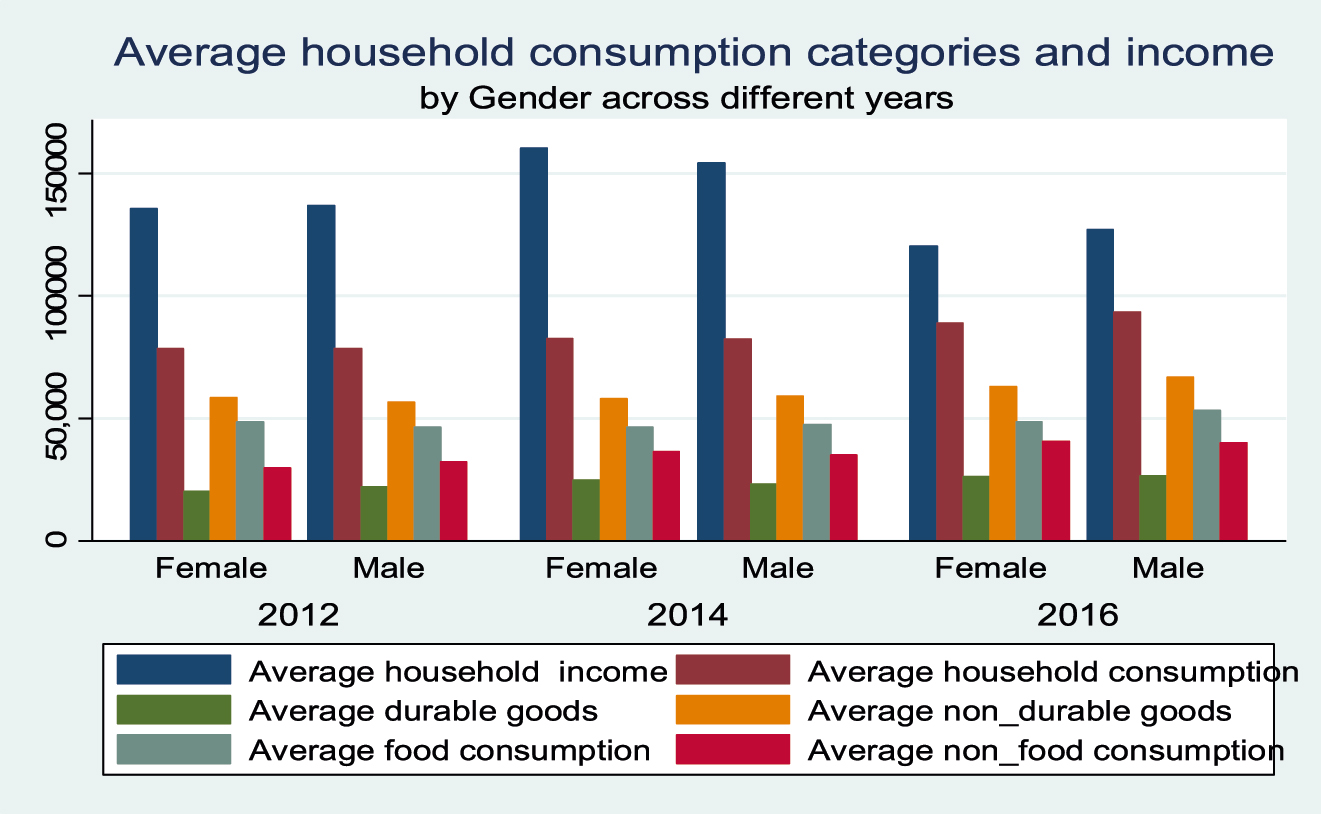

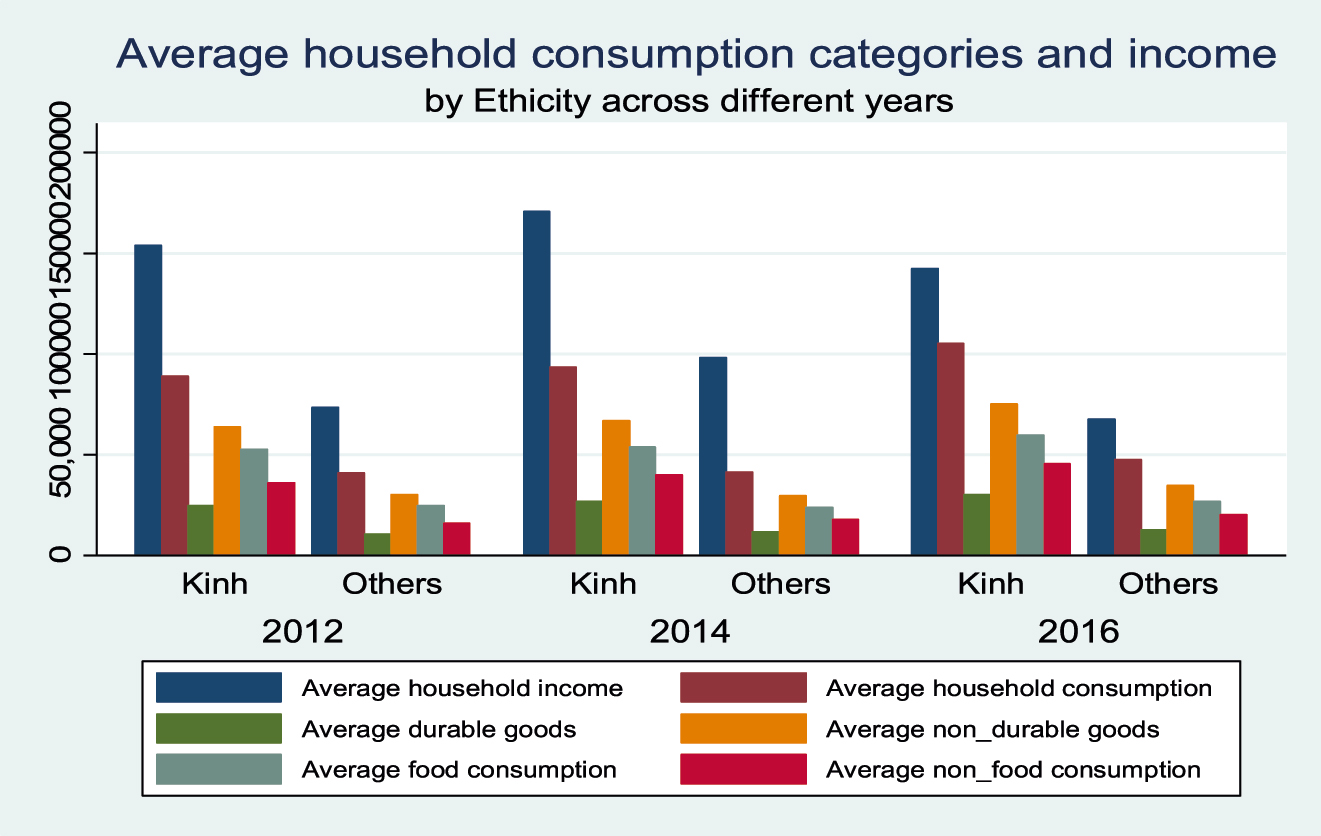

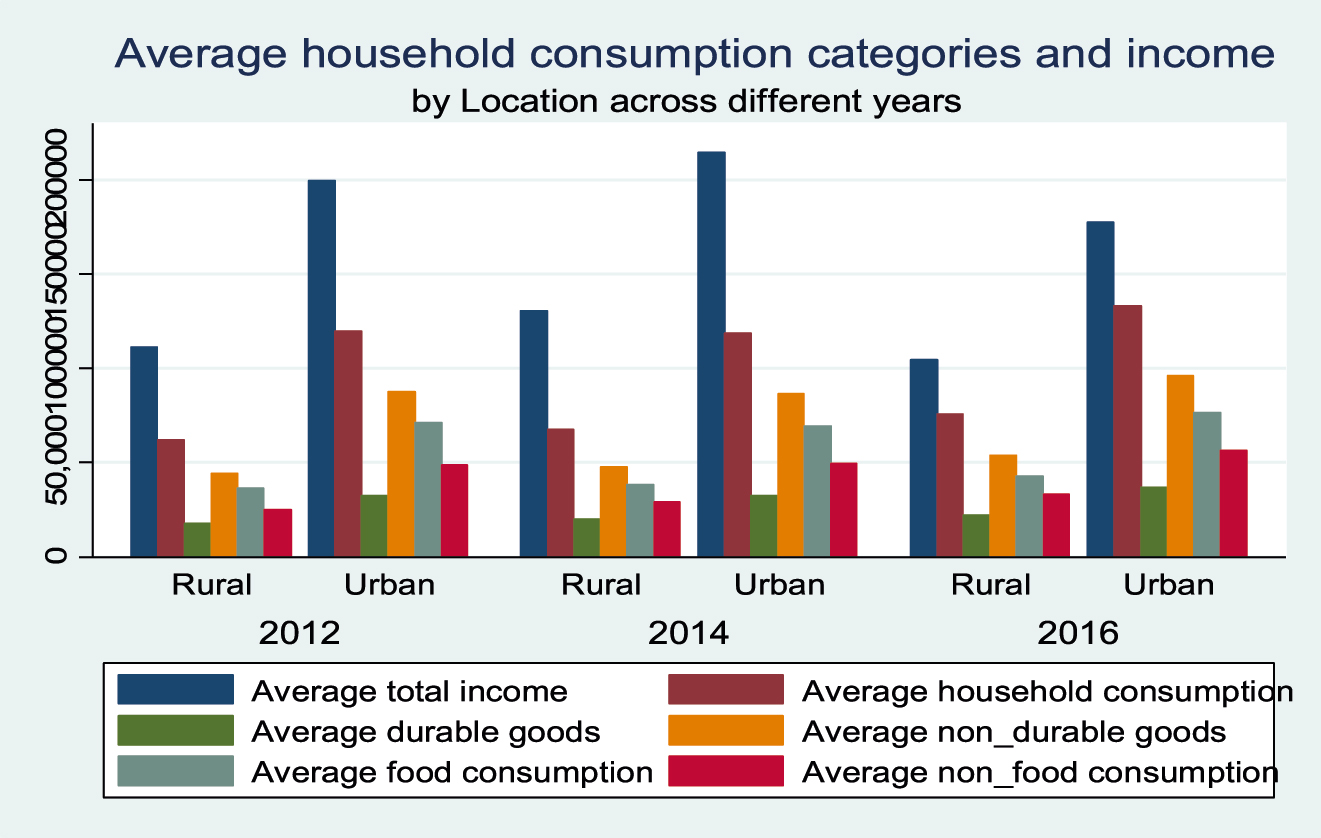

Additionally, there is relatively no difference between male and female household heads in terms of average consumption categories and income, as shown in Figure 3. This finding is not surprising because females and males have a similar ability to manage their household’s expenditures, ceteris paribus. Figures 4 and 5 present the difference in household consumption expenditures and income across ethnicity and location, respectively. It appears that households living in urban areas and Kinh ethnicity are wealthier than those living in rural areas and minority ethnicities. Therefore, their expenditures in terms of durable goods, non-durable goods, and food and non-food items are much higher. This is consistent with the supposition that people in cities might have many opportunities to obtain high-wage work, while living costs in urban areas are higher than in rural areas.

Household consumption and income by gender of household head.

Household consumption and income by ethnicity of household head.

Household consumption and income by location of household head.

Of course, this evidence does not necessarily imply that households living in urban areas and Kinh peoples are at a higher risk in terms of occupations and greater income uncertainty. Indeed, the increase in household consumption is matched by a parallel increase in household income over the age of the household head, which could be supported by the LCH.

4 Econometric Modelling and Estimation Procedure

Based on the variables discussed in the previous section, the following model in Eq. (1) sets up the econometric model using micro balanced panel data of three waves for households in Vietnam. The aim is to unify the model and study four hypotheses simultaneously to evaluate how four factors can explain household consumption decisions. Therefore, the discussion so far implies the following fixed effects regression can be written as:

where CONSUMP

it

is the outcome of interest, and the natural logarithm of household consumption by household i of year t; X

it

includes a wide set of household-specific characteristics such as regions, household assets and household head educational levels, which are assumed to significant influence on consumer behaviour;

The expression allows us to test several hypotheses, including the PIH, the LCH, the sex ratio hypothesis and precautionary saving hypothesis. Notably, the PIH and its intuition suggested that consumption should not respond to income fluctuation or consumption is only determined by permanent labour income but not current labour income, implying the marginal propensity to consume of transitory income should be equal to zero (β2 = 0) while its permanent income is 1 (β1 = 1). However, the empirical evidence argues that these strict conditions do not fit with the real data due to income uncertainty and borrowing constraints (Meng 2003; Paxson 1992). As a result, the life-cycle or permanent income hypothesis was rejected (Souleles 1999). Hence, the relaxed assumption of PIH should be applied, which is β1 > β2 (Meng 2003; Miles 1997). In this specification of consumption modelling, W it represents the life-cycle factors indicate that households with more children and more elderly people are expected to save less and consume more (Paxson 1992). Another explanation is that parents are expected to receive support from their children when they get older or retire, so they will spend more on their children as an investment in their life. It is also true that almost all elderly people choose to live with their families when they retire. In East Asian countries, the roles of family members are clearly defined due to social norms. Parents are expected to have a social responsibility to take care of children and elderly members. Therefore, households with more children also spend more and even save less. It is suggested that the sign of γ is expected to be positive correlation with consumption.

Additionally, according to the life-cycle theory, the relationship between age and total consumption exerts the invested U-shape curve as the well-known concave age-consumption nexus. Hence, we expected the signs of the coefficient of the age variable and the age square variable are significantly positive and negative, respectively. Further, based on the precautionary saving hypothesis, if Vietnamese households are precautionary savers, the signs of θ1 and θ2 should be significantly negative. And τ1 and τ2 should be significantly positive signs if the occupations with low labour income risk have significantly higher consumption in comparison with other occupations. For multiple choices of occupations, it is expected that the consumption of lower-risk occupations is likely higher than that of higher risk ones. As mentioned before, due to less pressure in the marriage market, a household with all female children (F it ) is more likely to consume more than households with all male children (M it ). The alternative explanation is that a woman tends to move to live with a man’s family after marriage. In other words, families with only female children might consume more.

Our key regressors are the earning uncertainty of both head and partner households for the precautionary saving hypothesis, households with all female children or male children for the sex ratio hypothesis, and the proportion of children and elderly members and the age variable for life-cycle factors. To test the existence of the precautionary saving hypothesis by evaluating the impact of household income uncertainty on the current consumption as H0 : θ i = 0 and H1 : θ i < 0, because in the presence of income uncertainty, it is optimal to reduce the current consumption. The other test is H0 : τ i = 0 and H1 : τ i > 0, to indicate that individuals with low-income risk occupations have significantly higher current consumption than others with high labour income risk and vice versa. Besides, we assess the existence of PIH, sex ratio hypothesis and LCH regarding the coefficients of γ, φ, β1 and β2.

Several econometric issues should be addressed. An important potential bias in the estimated effects of income uncertainty is the current consumption function does not include all relevant factors affecting household consumption, such as household tastes or wealth. Therefore, the error term might correlate with proxies of income uncertainty and income. However, the purpose of this study is to estimate the effect of proxies of income uncertainty on consumption, not labour income. In this case, we assumed that income variables are exogenous. Miles (1997) showed that human capital accumulation is an important source of income and consumption; thus, income might be correlated with the error term in Eq. (1), whereas it is beyond our scope. Hopefully, it will be accounted for the future research. Another potential problem is individuals prefer to switch in low-risk types rather than high-risk types due to risk aversion influences; therefore, the empirical results might be inconsistent because of the unobserved risk. To overcome this issue, we provide empirical results that include and exclude farmers and self-employed households. By doing this, the endogeneity and the selection bias could be eliminated. To correct for heteroskedasticity, the paper uses White’s heteroskedasticity consistent standard errors to adjust for potential heteroskedasticity.

One of the potential problems is the selection of occupations. Individuals with a riskier income have an incentive to move to other jobs in less risky occupations. Our empirical approach attempts to avoid the potentially biased selection of occupations though considering the different types of occupations. More precisely, we consider different behaviours between households that have a member working as civil servants and others because this type of job will be selected by governments. Additionally, there are many constraints to prevent individuals from changing their occupations in around four years (2012–2016); thus, we calculate the probability of entering and exiting formal occupations and moving out of the agriculture sector.

Estimating the consumption function in Eq. (1) requires information on both permanent and transitory labour incomes, in which permanent income is the income that a household would earn without idiosyncratic shock, while transitory labour income is defined as the difference between current incomes and permanent incomes. According to Musgrove (1979), permanent income is a function of observable variables, which is represented by a matrix X and an error term ɛ as follows:

Therefore, our research follows this way when estimating permanent labour income with the micro balanced panel dataset from 2012 to 2016. We extend Fuchs-Schündeln and Schündeln (2005), who used instrument variables for obtaining permanent income through a household’s characteristics. We also followed Benito (2006) and Guariglia and Kim (2004) to obtain the predicted values as a proxy of permanent labour income by estimating the effects of variables from a set of observable household characteristics on a log of labour income of households by random effects. That is because the permanent income can be expressed by the equation to capture age cohort effects and non-homotheticity of preferences. Notably, the error term ɛ might contain unobserved individual characteristics that are also accounted for in permanent income (Bhalla 1980) when using cross-sectional data.[7] They also suggested that an alternative approach using cross-sectional data is the weighted average of incomes to calculate permanent income. However, to apply this, it is necessary to have past income data (Meng 2003). Unfortunately, we do not have such information on households’ previous incomes. Therefore, to obtain more precise results, we calculated the predicted values from the income equation as an appropriate indicator of permanent income by using a random effects regression. We control a wide range of household characteristics in earning equations in a balanced panel data and accepted the weak version of PIH, namely: gender head of household, number of workers in a household, age cohorts, regions, number of children that followed Miles (1997) and Fuchs-Schündeln and Schündeln (2005); educational levels, occupations of both main earners and the household being poor.

5 Results and Discussions

The final parsimonious estimate of our econometric model focusing on precautionary saving hypothesis, PIH, sex ratio hypothesis and LCH, together with a set of diagnostic statistics, are presented in Table 2. It is notable that permanent income is the crucial factor affecting household consumption decisions. The model evaluations are accordingly based on the permanent income data, which is obtained from the income equation in Appendix B. Then, we use two-stage least squares to indicate whether households are able to smooth their consumption over time. Since household consumption and income are measured in logarithms, our results can be directly interpreted as the marginal propensity to consume. The results indicate the need to add both permanent and transitory incomes when testing other theories. Overall, our results suggest that interested coefficients remain relatively unchanged in both their magnitudes and significant levels when controlling other hypotheses.

Estimated results of the total household consumption across different hypotheses.

| Wave | Permanent income | Precautionary | Life cycle factors | Sex ratio | Combination | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hypothesis | motives hypothesis | hypothesis | hypothesis | |||||||

| Coef. | Robust | Coef. | Robust | Coef. | Robust | Coef. | Robust | Coef. | Robust | |

| std. err | std. err | std. err | std. err | std. err | ||||||

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) |

| Permanent income

|

0.546*** | (0.0377) | 0.559*** | (0.0393) | 0.554*** | (0.0384) | 0.548*** | (0.0379) | 0.573*** | (0.0402) |

| Transitory income

|

0.193*** | (0.0237) | 0.197*** | (0.0241) | 0.193*** | (0.0226) | 0.193*** | (0.0237) | 0.198*** | (0.0228) |

| Household head being a manager/leader (τ31) | – | – | 0.109 | (0.0894) | – | – | – | – | 0.126 | (0.0902) |

| Household head being a staff/employee (τ32) | – | – | 0.0313 | (0.0291) | – | – | – | – | 0.0365 | (0.0289) |

| Household head being waged employment (τ33) | – | – | 0.0147 | (0.0312) | – | – | – | – | 0.0148 | (0.0307) |

| Household head being self-employment in agriculture (τ34) | – | – | 0.0591* | (0.0311) | – | – | – | – | 0.0637** | (0.0312) |

| Household head being self-employment in non-agriculture sectors (τ35) | – | – | 0.0862* | (0.0441) | – | – | – | – | 0.0803* | (0.0434) |

| Employment status of household head (τ36) | – | – | 0.0626 | (0.0653) | – | – | – | – | 0.0525 | (0.0660) |

| Household head being not working (θ1) | – | – | −0.139** | (0.0545) | – | – | – | – | −0.156*** | (0.0531) |

| Spouse being a manager/leader (τ41) | – | – | −0.0078 | (0.137) | – | – | – | – | −0.00300 | (0.139) |

| Spouse being a staff/employee (τ42) | – | – | −0.0405 | (0.0293) | – | – | – | – | −0.0399 | (0.0289) |

| Spouse being waged employment (τ43) | – | – | 0.00896 | (0.0387) | – | – | – | – | 0.00203 | (0.0389) |

| Spouse being self-employment in agriculture (τ44) | – | – | −0.0354 | (0.0275) | – | – | – | – | −0.0274 | (0.0274) |

| Spouse being self-employment in non-agriculture sectors (τ45) | – | – | 0.0520 | (0.0408) | – | – | – | – | 0.0569 | (0.0402) |

| Employment status of spouse (τ46) | – | – | 0.0923 | (0.0653) | – | – | – | – | 0.0826 | (0.0638) |

| Spouse being not working (θ2) | – | – | −0.0216 | (0.0393) | – | – | – | – | −0.0259 | (0.0391) |

| Proportion of children | – | – | 0.000517* | (0.0003) | – | – | 0.00051* | (0.0003) | ||

| Proportion of elderly | – | – | – | – | 0.00195** | (0.0009) | – | – | 0.00196** | (0.0009) |

| Age | – | – | – | – | 0.0474*** | (0.0160) | – | – | 0.0469*** | (0.0160) |

| Age2 | – | – | – | – | −0.00062*** | (0.0002) | – | – | −0.0006*** | (0.0002) |

| Household with all sons | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.0214 | (0.0328) | 0.0238 | (0.0332) |

| Household with all daughters | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.00360 | (0.0374) | 0.0066 | (0.0373) |

| Socio-demographic | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Time fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Household fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Testing weak version of PIH (

|

74.80 (0.0000) | 77.04 (0.0000) | 79.03 (0.0000) | 75.20 (0.0000) | 81.87 (0.0000) | |||||

| Testing sex ratio hypothesis (

|

– | – | – | 0.13 (0.7149) | 0.12 (0.7238) | |||||

| R2 (%) | 63.85 | 64.20 | 62.86 | 63.83 | 63.48 | |||||

| F-statistics | 72.50 | 30.32 | 54.05 | 59.33 | 26.01 | |||||

| Number of observations | 3525 | 3525 | 3525 | 3525 | 3525 | |||||

-

Log of household total consumption is dependent variable. Robust standard errors are in parentheses. Social demographics are controlled and included here but not reported were: dummies for health insurance of household head and home ownership, household assets, living areas, number of years schooling. It should be noted that the variables including in the first-stage to obtain the permanent and transitory income datasets are excluded in the second-stage equation to estimate the effect of inter-related economic hypotheses on consumption, thus the whole is identifiable, and a constant, and ***p < 0.01; **p < 0.05 and *p < 0.1.

The empirical results in column 9 point out that the coefficients of both permanent and transitory income variables are statistically significant at a 1% level of significance with the expected positive signs. The long-run marginal propensity to consume derived from the permanent income variable indicates that, on average, a 1% increase in the permanent income is associated with 0.573% increase in household consumption. Hence, total household consumption increases as they become wealthier. Likewise, a 0.198% increase in household consumption would be derived from a 1% increase in transitory income. Not surprisingly, the estimated parameters of permanent income are significantly greater than that of transitory income, and the difference of both parameters is statistically significant at a 1% level. Our findings are therefore consistent with the view of the weak version of PIH. A test of the quality of the weak version of the PIH concludes that the null hypothesis is rejected because χ2 (1) with the p_value of all equations is lower than the conventional level of significance. The statistical test of coefficients of permanent income and transitory income indicates that households are capable of smoothing their total consumption over time. This finding confirms other studies such as Benito (2006) and Miles (1997). However, the magnitude of the estimated coefficients is relatively higher than in both studies. For example, Benito (2006) found the permanent and transitory income elasticities for British households are 0.418 and 0.113, respectively, while elasticities are found to be 0.82 and 0.61 by Miles (1997), accordingly. The higher margin to consume generally reflects that households in developing countries are likely to be high-income elastic, but the responsiveness of consumption to both permanent and transitory income is similar.

The income uncertainty regarding both household head and their spouses relatively behave as expected—the riskier occupations in terms of income volatility correspond to lower levels of total consumption, although some estimated coefficients are not significant. More precisely, the coefficient of the household head not working variable, which is considered the most important source of income uncertainty, is negatively signed and statistically significant at a 1% level of significance. These results might partly reflect that households facing high-income uncertainty are more likely to consume less and save more. This inference is consistent with the prediction of precautionary saving motives in terms of risk aversion.

Among the variables related to household heads’ occupations, only the coefficients associated with the household head being self-employment in agriculture and household head being self-employed in non-agriculture sectors variables are statistically significant at the conventional level. The magnitude of the former is relatively lower than the latter, 0.0673 and 0.0803, respectively. As suggested, the higher occupational risks or unstable work corresponds to lower current consumption; thus, our empirical results are relatively in line with the oriental predictions of precautionary hypotheses. However, there is no evidence of the spouse’s occupations on the household consumption in Vietnam, supporting the argument that household consumption decisions merely depend on the household head’s behaviour, yet are not influenced by the spouse’s decisions. One possible way to explain these results is due to self-selection by occupation (Skinner 1988). Surprisingly, the coefficients of both household heads and spouses who have been working for state organisations as civil servants are positive but statistically insignificant in various equations. One way to explain this is in Vietnam, the wages of civil servants are relatively low, thus civil servants are likely to save more and consume less, especially those who live in cities. By contrast, Fuchs-Schündeln and Schündeln (2005) presented a contradictory result in an analysis of the precautionary effects of the civil servant variables in both West and East Germany, where their evidence is in favour of the precautionary savings hypothesis.

Regarding life-cycle factors, there is strong evidence supporting the hypothesis that a higher proportion of children and elderly people is associated with a higher level of household consumption. More specifically, the empirical results indicate the impact of the proportion of children on total consumption is positive and statistically significant at 10% levels if other things are held constant. In addition, as expected, a higher proportion of elderly members is associated with a higher total consumption. The literature emphasises the conclusion that households with more children and elderly members are more likely to save less and consume more, which is in line with Paxson’s (1992) LCH. Further, as expected, the coefficient attached to the age square variable is statistically significant and negatively signed, and the age variable is positive and significant. These results provide strong support for the LCH that an increase in the age of household head leads to rising household total consumption until a certain threshold, and then starts to decrease as individuals get older. The results are consistent with the findings of Skinner (1988). This finding is also in line with the well-documented fact that individuals face sustainable uncertainty over their lifetime, thus accumulating more wealth. Consequently, consumers are likely to consume less while they are young. The opposite is true when they get older and the maximum point is in middle age.

To test unbalance sex ratio hypothesis, we expected that households with all daughters are more likely to consume more and save less than households with all male children; thus, the coefficient of the former would be a positive and significant sign and higher than that of the latter. Results indicate that households with all female children exert a positive but insignificant effect. Further, testing the difference among these coefficients suggests no difference between households with all female children and households with all male children. This finding contradicts the conclusion of Wei and Zhang (2011). Due to less pressure in the marriage market, households with only female children are likely to consume more and save less. Conversely, after getting married, a woman tends to move to live with her husband’s family to take care of elderly people; thus, households with only female children are more likely to save more to smooth their consumption in their older years. Hence, there is an ambiguous relation to the sex ratio hypothesis.

Now we examine whether these hypotheses are also true across different consumption categories. This is important for policy implications because households facing income uncertainty are unable to smooth their basic food consumption, health expenditure and educational expenditure. Therefore, governments should provide the fundamental goods and services for those who are unable to cover their food consumption to sustain their nutrition intake, especially in poor households. In addition, the importance of health and education in fostering economic growth in Vietnam is indisputable. Hence, if the families are unable to smooth education and health expenditures over time, the consequence is that their children’s educational levels are far below the high-income groups. In the long run, the inequality in both income and consumption becomes larger among different income groups. As a result, it is important to find whether households in Vietnam are able to smooth their consumption expenditure by categories. The total household consumption can be decomposed into durable goods consumption, non-durable goods consumption, health expenditure, education expenditure, food consumption and non-food consumption. Table 3 reports a comparison of the multiple regression results for different categories of total household expenditures controlling for key household characteristics. As noted previously, the independent variables represented four economic theories. Overall, empirical results of testing hypotheses are relatively mixed and reflect findings from previous literature.

Estimated results of different household consumption categories across different hypotheses.

| Categories | Food | Non-food | Durable | Non-durable | Health | Education |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | consumption – CF | consumption – CNF | goods – CD | goods – CND | expenditure – CHE | expenditure – CEE |

| Permanent income

|

0.608*** | 0.569*** | 0.586*** | 0.582*** | 0.722*** | 2.095*** |

| (0.0458) | (0.0478) | (0.0547) | (0.0420) | (0.154) | (0.261) | |

| Transitory income

|

0.189*** | 0.194*** | 0.200*** | 0.187*** | 0.0925 | −0.235** |

| (0.0250) | (0.0266) | (0.0288) | (0.0235) | (0.0666) | (0.109) | |

| Household head being | 0.222** | 0.0145 | 0.0510 | 0.155* | −0.902** | −0.272 |

| a manager/leader | (0.100) | (0.0926) | (0.123) | (0.0905) | (0.418) | (0.449) |

| Household head being | 0.0737** | −0.00613 | −0.00107 | 0.0534* | −0.0198 | 0.148 |

| a staff/employee | (0.0346) | (0.0318) | (0.0362) | (0.0308) | (0.103) | (0.174) |

| Household head being | 0.0539 | −0.0184 | −0.0260 | 0.0402 | 0.00421 | −0.120 |

| waged employment | (0.0361) | (0.0355) | (0.0403) | (0.0340) | (0.111) | (0.207) |

| Household head being | 0.0792** | 0.0639* | 0.0717* | 0.0694* | 0.0963 | −0.296 |

| self-employment in agriculture | (0.0392) | (0.0354) | (0.0393) | (0.0356) | (0.113) | (0.180) |

| Household head being self-employment | 0.117** | 0.0376 | 0.0527 | 0.0855* | 0.245 | −0.497** |

| in non-agriculture sectors | (0.0467) | (0.0535) | (0.0542) | (0.0456) | (0.156) | (0.251) |

| Employment status of | 0.0738 | 0.00762 | 0.0119 | 0.0574 | 0.0335 | −0.612 |

| household head | (0.0821) | (0.0671) | (0.0781) | (0.0764) | (0.300) | (0.452) |

| Household head being | −0.154** | −0.141** | −0.152* | −0.125** | −0.722*** | 0.125 |

| not working | (0.0630) | (0.0703) | (0.0888) | (0.0560) | (0.246) | (0.462) |

| Spouse being a | 0.123 | −0.152 | 0.0995 | −0.0369 | 0.636 | 1.457 |

| manager/leader | (0.157) | (0.142) | (0.174) | (0.169) | (0.479) | (1.176) |

| Spouse being a | −0.0449 | −0.0201 | −0.00842 | −0.0388 | 0.0819 | −0.332* |

| staff/employee | (0.0341) | (0.0322) | (0.0375) | (0.0312) | (0.103) | (0.175) |

| Spouse being waged | −0.00560 | −0.0415 | −0.0706 | 0.0191 | 0.0837 | 0.0291 |

| employment | (0.0458) | (0.0442) | (0.0478) | (0.0425) | (0.122) | (0.217) |

| Spouse being self-employment | −0.0532 | 0.00811 | −0.00539 | −0.0269 | 0.128 | −0.0538 |

| in agriculture | (0.0335) | (0.0328) | (0.0366) | (0.0313) | (0.110) | (0.174) |

| Spouse being self-employment | 0.0634 | 0.0148 | 0.0139 | 0.0672 | 0.00999 | 0.250 |

| in non-agriculture sectors | (0.0438) | (0.0479) | (0.0514) | (0.0425) | (0.138) | (0.262) |

| Employment status | 0.0943 | 0.0364 | 0.108 | 0.0509 | −0.372 | 1.745*** |

| of spouse | (0.0864) | (0.0784) | (0.0897) | (0.0709) | (0.258) | (0.608) |

| Spouse being not | −0.00790 | −0.0229 | −0.0161 | −0.0252 | −0.242 | 0.105 |

| working | (0.0465) | (0.0469) | (0.0528) | (0.0426) | (0.154) | (0.271) |

| Proportion of | 0.000643* | 0.000326 | 0.00038 | 0.000655** | 0.00262** | 0.0116*** |

| children | (0.000334) | (0.00035) | (0.0004) | (0.0003) | (0.0011) | (0.0019) |

| Proportion of elderly | 0.00271*** | 0.000751 | 0.000543 | 0.00243*** | 0.00840** | 0.00280 |

| (0.000934) | (0.00133) | (0.00153) | (0.000807) | (0.00345) | (0.00441) | |

| Age | 0.0294 | 0.0712*** | 0.0931*** | 0.0327** | 0.0560 | 0.844*** |

| (0.0179) | (0.0213) | (0.0265) | (0.0163) | (0.0602) | (0.133) | |

| Age2 | −0.000417* | −0.000910*** | −0.00113*** | −0.000473** | −0.000627 | −0.0105*** |

| (0.000224) | (0.000248) | (0.000302) | (0.000204) | (0.000744) | (0.00154) | |

| Household with | 0.0270 | 0.0582 | 0.0673 | 0.0211 | −0.147 | 0.934*** |

| all sons | (0.0392) | (0.0355) | (0.0433) | (0.0350) | (0.126) | (0.230) |

| Household with | −0.00783 | 0.0322 | 0.00245 | 0.0150 | −0.0171 | 0.761*** |

| all daughters | (0.0405) | (0.0445) | (0.0473) | (0.0397) | (0.128) | (0.283) |

| Socio-demographic | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Time fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Household fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Testing weak version of PIH (

|

79.26 (0.0000) | 57.38 (0.0000) | 47.51 (0.0000) | 85.32 (0.0000) | 15.16 (0.0001) | 70.59 (0.0000) |

| Testing sex ratio hypothesis (

|

0.41 (0.5210) | 0.22 (0.6382) | 1.16 (0.2814) | 0.01 (0.9065) | 0.58 (0.4466) | 0.24 (0.6234) |

| R 2 | 53.07 | 62.15 | 55.19 | 59.05 | 13.74 | 27.16 |

| F-statistics | 16.11 | 23.75 | 18.11 | 20.27 | 4.70 | 7.08 |

| Number of observations | 3525 | 3525 | 3525 | 3525 | 3525 | 3525 |

-

Log of each household consumption categories is dependent variable. Robust standard errors are in parentheses. Social demographics are controlled and included here but not reported were: dummies for health insurance of household head and home ownership, household assets, living areas, number of years schooling, and a constant, and ***p < 0.01; **p < 0.05 and *p < 0.1.

The results provide general evidence supporting the weak version of PIH across different samples. The marginal propensity to consume food, non-food, non-durable goods and durable goods of permanent income and transitory income is positive and statistically significant at a 1% level, suggesting households are capable of smoothing their food consumption, non-food consumption, durable goods and non-durable goods effectively. Testing the difference of both coefficients related to permanent income and transitory income confirms the marginal propensity to consume for permanent incomes is statistically higher than that of transitory incomes at a 1% level. These findings are consistent with several previous studies. For example, Benito (2006) found the elasticity of permanent incomes is statistically significantly higher than transitory incomes for British households. However, a negative relationship between the transitory income variable and education expenditure—indicating education expenditure decreases with higher transitory income at the conventional level—was quite surprising and warrants caution. Additionally, the marginal propensity to consume related to the permanent income variable is greater than 1, which contradicts the economic theory. Our results suggest that households with higher permanent income are more likely to invest in education, while families with higher transitory income tend to reduce educational investment. This finding contradicts Meng (2003), who found the effects of both transitory and permanent income are insignificant and close to zero on educational expenditure. For health expenditure, 0.722% increase in household health expenditure might be derived from a 1% increase in permanent income, whereas there is no relationship between health expenditure and transitory income.

In general, results indicate the main earners working in lower-risk jobs are likely to consume more and save less, which is supported by precautionary effects. More precisely, among household heads’ occupation variables, the coefficients of the household head being a manager variable and the household head being a staff variable are positive and statistically significant in the food consumption regressions and non-durable goods regression. Further, the magnitude of the household head being a leader variable is relatively greater than that of the other. Intuitively, individuals with lower-risk employment are likely to consume food and non-durable goods more than those with high-risk occupations. These findings are generally consistent with the findings of Fuchs-Schündeln and Schündeln (2005) and Lugilde, Bande, and Riveiro (2018), yet inconsistent with Skinner (1988). For the remaining consumption categories, there is no evidence of precautionary effects. In addition, as expected, households being self-employment in non-agriculture sectors tend to consume more foods and non-durable goods than households self-employed in agriculture, implying that households facing higher income uncertainty risks tend to consume less and save more in terms of foods and non-durable goods due to precautionary effects. This confirms our intuition that higher occupation risks matter in determining current household consumption of both food and non-food categories. Not surprisingly, the household head not working variable is negative and statistically significant at the conventional level for all most regressions except for education expenditure results. Intuitively, this is considered the riskiest uncertainty; thus, due to precautionary effects, households would spend less on food, non-food, durable goods and non-durable goods. This finding aligns with the number of previous studies. For instance, Stephens (2004) found that job losses contribute to reducing household food consumption. Further, a one-point decrease in the unemployment rate leads to a strong increase in household expenditure on non-durable goods and services (Campos and Reggio 2015). However, no occupational variables related to spouses were found to be influential in explaining the variance of household consumption categories except education expenditure. We found that households with the spouse working for state organisations or companies as civil servants are more likely to spend more on education. This is only a variable supported by the precautionary effects, as explained by Fuchs-Schündeln and Schündeln (2005), whereby civil servants with stable income face lower labour income risk than other occupations. Notably, the effect of working in different occupations is different for different consumption categories. It might be that individuals of the same occupational group are characterised by similar educational levels, experience and income levels. For instance, one may expect waged employees and leaders to have higher levels of income and education compared to those in self-employment in agriculture, in general. Furthermore, managers have the highest probability of homeownership, whereas the majority of workers are renters. While this is beyond the scope of this analysis, further research should pay attention to understanding this mechanism, which would be the fruit of further research to explore.