Abstract

Given that economic growth is associated with increased life expectancy, declines in cognitive ability among the elder is a critical problem across the developed world. In this paper, we analyze the causal effect of the death of a spouse on the surviving spouse’s cognitive ability using the fixed effect model. The reliability of the estimates is enhanced by robustness checks, such as an event study model, to attend to potential threats to identification. Results show that, on average, spousal loss significantly reduces the cognitive functioning of the surviving spouse. We also study heterogeneity in the effect of spousal loss, finding that co-residing with children greatly mitigates the negative effect of bereavement.

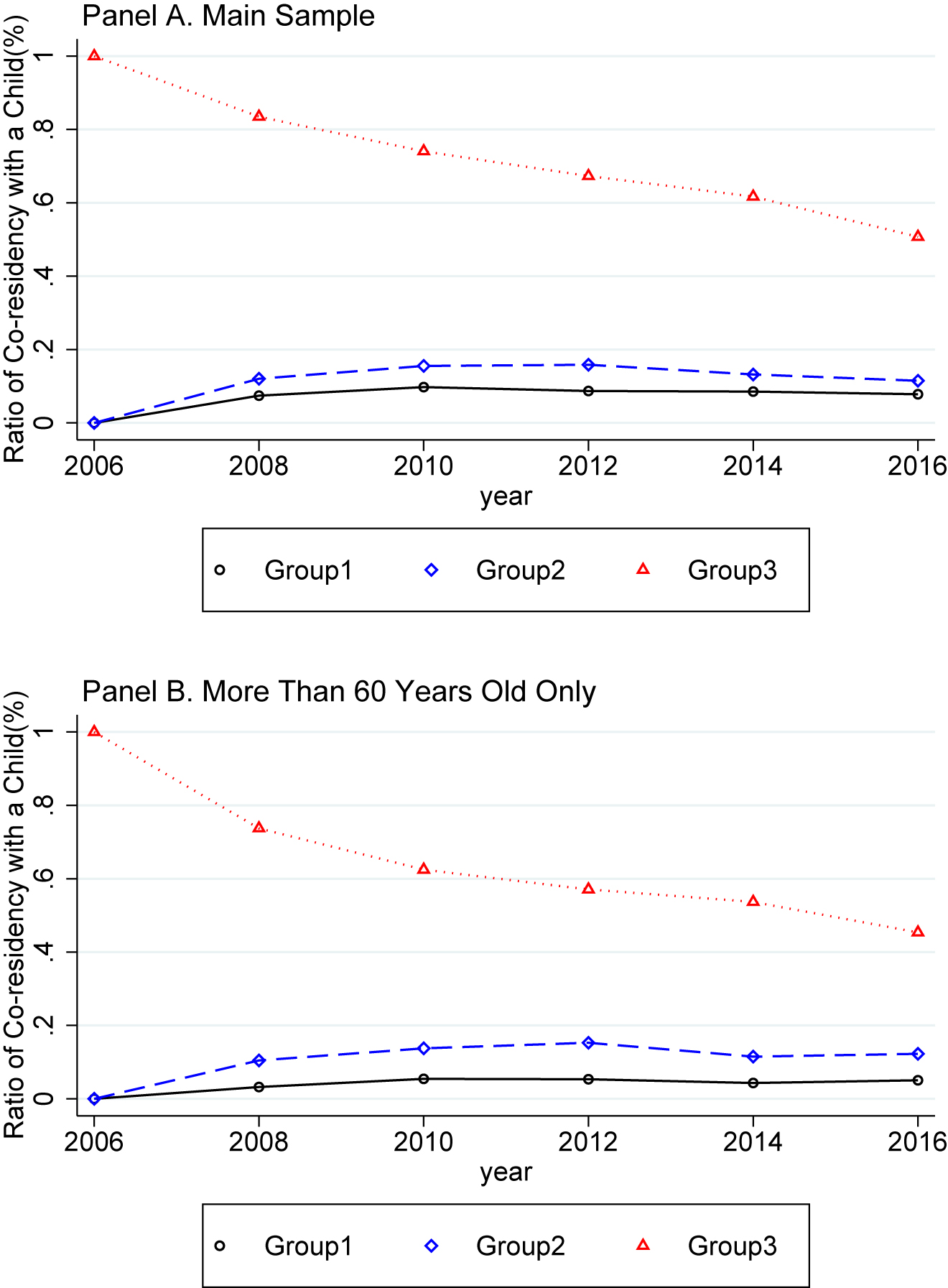

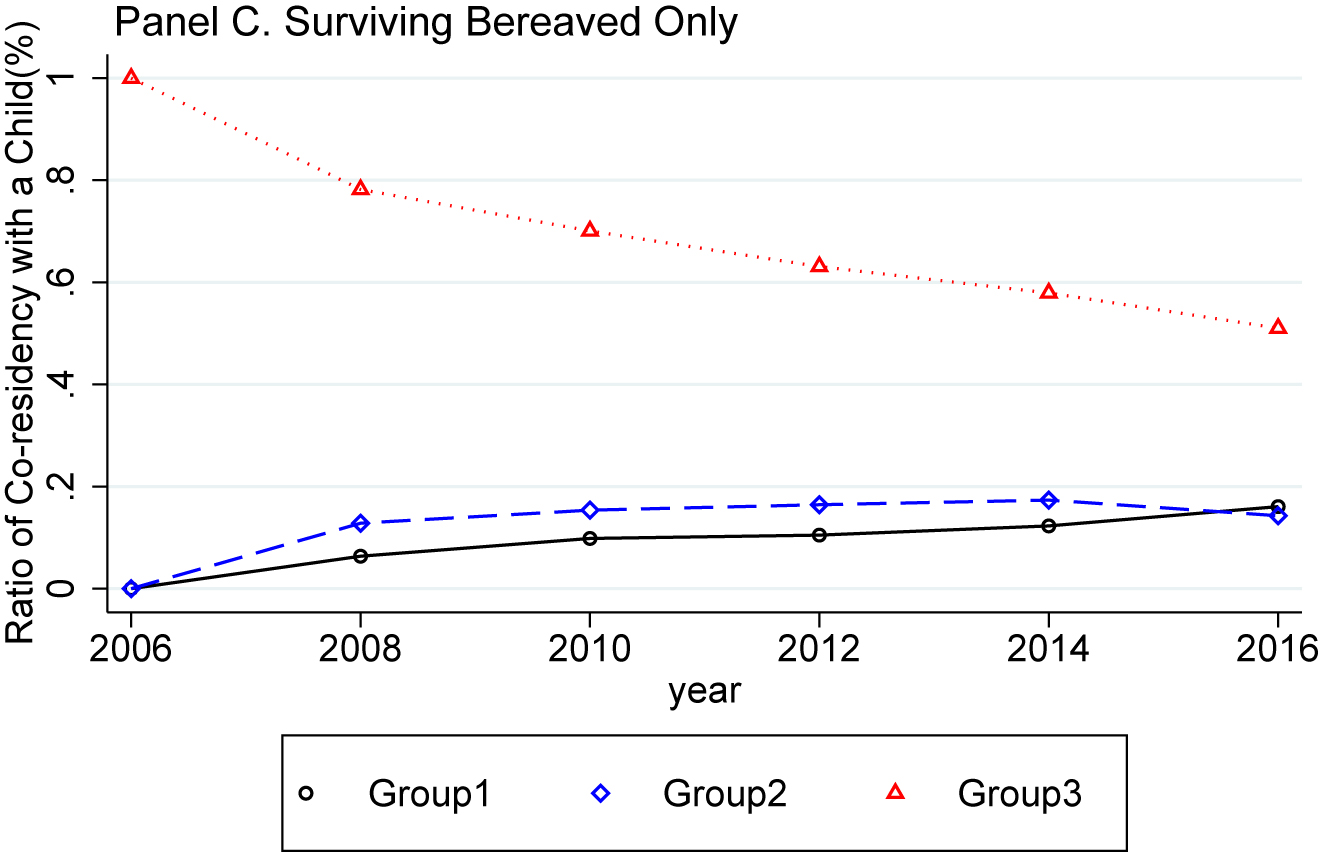

Dynamics of co-residing with children by groups.

This figure shows the dynamics of co-residency separately by three groups. The three groups are defined based on coresidency in 2006 and the definition of each group is the following: those not living within a proximity of 30 minutes of a child (Group 1), living within a proximity of 30 minutes of a child (Group 2), and co-residing with a child (Group 3).

(continued)

Summary statistics of pre-determined variables (2006) by groups (age 60>).

| K-MMSE | Age | Relative poverty | Highest level of | ADL index | IADL index | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| score | status | educational | score | score | ||

| attainment | ||||||

| Group 1 | ||||||

| Mean | 27.47 | 67.18 | 0.65 | 1.87 | 0.02 | 0.19 |

| SD | 1.91 | 5.42 | 0.48 | 1.05 | 0.23 | 0.73 |

| Min | 24.00 | 60.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Max | 30.00 | 88.00 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 7.00 |

| Group 2 | ||||||

| Mean | 27.27 | 67.13 | 0.64 | 1.94 | 0.03 | 0.21 |

| SD | 1.93 | 4.96 | 0.48 | 1.07 | 0.32 | 0.68 |

| Min | 24.00 | 60.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Max | 30.00 | 82.00 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 5.00 | 6.00 |

| Group 3 | ||||||

| Mean | 27.48 | 65.90 | 0.48 | 1.94 | 0.04 | 0.32 |

| SD | 1.96 | 4.99 | 0.50 | 1.03 | 0.41 | 1.09 |

| Min | 24.00 | 60.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Max | 30.00 | 86.00 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 7.00 | 10.00 |

| Overall | ||||||

| Mean | 27.43 | 66.71 | 0.59 | 1.91 | 0.03 | 0.24 |

| SD | 1.93 | 5.19 | 0.49 | 1.05 | 0.33 | 0.87 |

| Min | 24.00 | 60.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Max | 30.00 | 88.00 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 7.00 | 10.00 |

-

This table includes reports the same information included in Table 11 but uses the sample of adults older than 60 years of age. Group 1 consists of adults not living in close proximity to their children (within 30 min), Group 2 consists of adults living in close proximity to their children (within 30 min), and Group 3 consists of adults living in the same household with their children. Relative poverty status is a dummy variable indicating whether the adults’ household income is less than 50% of the median household income in the population. Educational Attainment is a categorical variable of the level of completed level of education. The variable for Highest Level of Education is coded to take on values from 1 to 4, referring to each of the following educational categories: elementary school, middle school, high school, and Bachelor’s Degree or Higher. SD is the abbreviation of standard deviation.

Robustness check for sample selection criteria.

| Number of observed (t ≥ 4) | Balanced panel (t = 6) | All | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Spousal loss | −0.480*** (0.171) | −0.368** (0.182) | −0.476*** (0.170) |

| n (Obs.) | 26,794 | 22,349 | 27,045 |

| n (PID) | 4673 | 3725 | 4775 |

-

Table reports coefficients for our sample selection criteria. Column (1) is the same as Column (2) of Table 3. Columns (2) and (3) are use the empirical equation in Column (1) but analyze a different sample. Column (2) is estimated using the balanced panel, and Column (3) is estimated using all observations. Standard errors are clustered at the family unit and in parentheses. Statistical significance: ***1% **5% *10%.

Propensity score estimation of sample attrition.

| Explanatory variables | Results |

|---|---|

| Age 51–60 | −0.201*** (0.071) |

| Age 61–70 | −0.027 (0.083) |

| Age 71–80 | 0.484*** (0.105) |

| Age 81–90 | 1.164*** (0.275) |

| K-MMSE score | −0.012 (0.015) |

| Female | −0.114*** (0.043) |

| Highest level of educational attainment (ref = elementary school) | |

| Middle school | −0.092 (0.081) |

| High school | 0.067 (0.072) |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 0.026 (0.100) |

| ADL score | −0.163 (0.130) |

| IADL score | 0.076* (0.040) |

| Relative poverty | 0.026 (0.058) |

| Co-residence with a child (Group 2) | 0.026 (0.095) |

| Co-residence with a child (Group 3) | 0.108 (0.068) |

| n (Obs.) | 4515 |

-

This table reports the coefficients from the probit regression analyzing attrition. Standard errors are clustered at the family unit and in parentheses. Statistical significance: ***1% **5% *10%.

The first stage result of the IV regression.

| Explanatory variables | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|

| Co-residency with a child in 2006 | 0.416*** (0.067) | |

| Number of children | 0.144*** (0.046) | 0.193*** (0.050) |

| Number of male children | −0.027 (0.032) | −0.012 (0.037) |

| Number of teenage children | 0.084 (0.103) | 0.204* (0.122) |

| Number of children in their 20s | 0.022 (0.065) | 0.014 (0.068) |

| Number of children in their 30s | −0.001 (0.029) | −0.008 (0.032) |

| Number of grandchildren | −0.020 (0.020) | −0.016 (0.021) |

| Number of married children | −0.089* (0.053) | −0.185*** (0.049) |

| Intercept | 0.125 (0.084) | 0.353*** (0.094) |

| F-statistic | 36.19 | 16.06 |

| n (Obs.) | 245 | 245 |

-

This table reports the coefficients for the first stage of the IV regression of Table 13. Column (1) reports findings using co-residency with a child in 2006 as an instrumental variable. Column (2) excludes co-residency with a child in 2006 as an instrumental variable. Standard errors are clustered at the family unit and in parentheses. Statistical significance: ***1% **5% *10%.

References

Abadie, A. 2005. “Semiparametric Difference-in-Differences Estimators.” Review of Economics Studies 72 (1): 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/0034-6527.00321.Suche in Google Scholar

Ahn, T., and K. D. Choi. 2019. “Grandparent Caregiving and Cognitive Functioning Among Older People: Evidence from Korea.” Review of Economics of the Household 17: 553–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-018-9413-5.Suche in Google Scholar

Angrist, J. D., and J. S. Pischke. 2008. Mostly Harmless Econometrics: An Empiricist’s Companion. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.10.2307/j.ctvcm4j72Suche in Google Scholar

Atalay, K., and A. Staneva. 2020. “The Effect of Bereavement on Cognitive Functioning Among Elderly People: Evidence from Australia.” Economics and Human Biology 39: 100932, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehb.2020.100932.Suche in Google Scholar

Atalay, K., G. F. Barrett, and A. Staneva. 2019. “The Effect of Retirement on Elderly Cognitive Functioning.” Journal of Health Economics 66: 37–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2019.04.006.Suche in Google Scholar

Bonsang, E., S. Adam, and S. Perelman. 2012. “Does Retirement Affect Cognitive Functioning?” Journal of Health Economics 31 (3): 490–501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2012.03.005.Suche in Google Scholar

Callaway, B., and P. H. C. Sant’Anna. 2021. “Difference-in-Differences with Multiple Time Periods.” Journal of Econometrics 225 (2): 200–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2020.12.001.Suche in Google Scholar

Celidoni, M., C. D. Bianco, and G. Weber. 2017. “Retirement and Cognitive Decline: A Longitudinal Analysis Using SHARE Data.” Journal of Health Economics 56: 113–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2017.09.003.Suche in Google Scholar

Coe, N. B., H.-M. von Gaudecker, M. Lindeboom, and J. Maurer. 2011. “The Effect of Retirement on Cognitive Functioning.” Health Economics 21 (8): 913–27. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.1771.Suche in Google Scholar

Doblhammer, G., G. J. van den Berg, and T. Fritze. 2013. “Economic Conditions at the Time of Birth and Cognitive Abilities Late in Life: Evidence from Ten European Countries.” PLoS One 8 (9): e74915. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0074915.Suche in Google Scholar

Fitzgerald, J., P. Gottschalk, and R. Moffitt. 1998. “An Analysis of Sample Attrition in Panel Data: The Michigan Panel Study of Income Dynamics.” Journal of Human Resource 33 (2): 251–99. https://doi.org/10.2307/146433.Suche in Google Scholar

Fletcher, J. 2010. “Spillover Effects of Inclusion of Classmates with Emotional Problems on Test Scores in Early Elementary School.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 29 (1): 69–83. https://doi.org/10.1002/pam.20479.Suche in Google Scholar

Fletcher, J., and R. Marksteiner. 2017. “Causal Spousal Health Spillover Effects and Implications for Program Evaluation.” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 9 (4): 144–66. https://doi.org/10.1257/pol.20150573.Suche in Google Scholar

Gupta, S. 2018. “Impact of Volunteering on Cognitive Decline of the Elderly.” The Journal of the Economics of Ageing 12: 46–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeoa.2018.01.002.Suche in Google Scholar

Kang, Y. W., D. L. Na, and S. H. Hahn. 1997. “A Validity Study on the Korean Mini-Mental State Examination (K-MMSE) in Dementia Patients.” Journal of the Korean Neurological Association 15 (2): 300–8.Suche in Google Scholar

Kim, H. 2019. “Retirement and Cognitive Ability in Korea.” Korean Economic Review 35: 393–415. https://doi.org/10.38121/kpea.2019.06.35.2.1.Suche in Google Scholar

Korea Employment Information Service. 2018. “The Guide of Multiple Imputation and Generated Variables,” (in Korean) Technical Report. Eumseong-Gun, Chungcheongbuk-Do: Korea Employment Information Service.Suche in Google Scholar

Lyu, J., J. Min, and G. Kim. 2019. “Trajectories of Cognitive Decline by Widowhood Status Among Korean Older Adults.” International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 34 (11): 1582–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.5168.Suche in Google Scholar

Manor, O., and Z. Eisenbach. 2003. “Mortality after Spousal Loss: Are there Socio-Demographic Differences?” Social Science & Medicine 56 (2): 405–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00046-1.Suche in Google Scholar

Martikainen, P., and T. Valkonen. 1996. “Mortality After the Death of a Spouse: Rates and Causes of Death in a Large Finnish Cohort.” American Journal of Public Health 86 (8): 1087–93. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.86.8_pt_1.1087.Suche in Google Scholar

Prince, M., A. Wimo, M. Guerchet, G-C. Ali, Miss, YT. Wu, and M. Prina. 2015. World Alzheimer Report 2015, The Global Impact of Dementia: An Analysis of Prevalence, Incidence, Cost and Trends. London: Alzheimer’s Disease International.Suche in Google Scholar

Rose, L. 2020. “Retirement and Health: Evidence from England.” Journal of Health Economics 73: 102352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2020.102352.Suche in Google Scholar

Shin, S. H., G. Kim, and S. Park. 2018. “Widowhood Status as a Risk Factor for Cognitive Decline Among Older Adults.” The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 26 (7): 778–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2018.03.013.Suche in Google Scholar

Siflinger, B. 2017. “The Effect of Widowhood on Mental Health – An Analysis of Anticipation Patterns Surrounding the Death of a Spouse.” Health Economics 26 (12): 1505–23. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.3443.Suche in Google Scholar

Simeonova, E. 2013. “Marriage, Bereavement and Mortality: The Role of Health Care Utilization.” Journal of Health Economics 32 (1): 33–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2012.10.010.Suche in Google Scholar

Staiger, D., and J. H. Stock. 1997. “Instrumental Variables Regression with Weak Instruments.” Econometrica 65 (3): 557–86. https://doi.org/10.2307/2171753.Suche in Google Scholar

Stroebe, M., H. Schut, and W. Stroebe. 2007. “Health Outcomes of Bereavement.” Lancet 370 (9603): 1960–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(07)61816-9.Suche in Google Scholar

Tseng, F., D. Petrie, S. Wang, C. Macduff, and A. I. Stephen. 2018. “The Impact of Spousal Bereavement on Hospitalisations: Evidence from the Scottish Longitudinal Study.” Health Economics 27 (2): 120–38. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.3573.Suche in Google Scholar

Van den Berg, G. J., M. Lindeboom, and F. Portrait. 2011. “Conjugal Bereavement Effects on Health and Mortality at Advanced Ages.” Journal of Health Economics 30 (4): 774–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2011.05.011.Suche in Google Scholar

Van Ness, P. H., and S. V. Kasl. 2003. “Religion and Cognitive Dysfunction in an Elderly Cohort.” Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 58B (1): S21–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/58.1.s21.Suche in Google Scholar

Vidarsdottir, H., F. Fang, M. Chang, T. Aspelund, K. Fall, M. K. Jonsdottir, P. V. Jonsson, M. F. Cotch, T. B. Harris, L. J. Launer, V. Gudnasson, and U. Valdimarsdottir. 2014. “Spousal Loss and Cognitive Function in Later Life: A 25-Year Follow-Up in the AGES-Reykjavik Study.” American Journal of Epidemiology 179 (6): 674–83. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwt321.Suche in Google Scholar

Zhang, Z., L. W. Li, H. Xu, and J. Liu. 2019. “Does Widowhood Affect Cognitive Function Among Chinese Older Adults.” SSM – Population Health 7: 100329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2018.100329.Suche in Google Scholar

Zhao, Y., B. Inder, and J. S. Kim. 2021. “Spousal Bereavement and the Cognitive Health of Older Adults in the US: New Insights on Channels, Single Items, and Subjective Evidence.” Economics and Human Biology 43: 101055. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehb.2021.101055.Suche in Google Scholar

Zunzunegui, M.-V., B. E. Alvarado, T. D. Ser, and A. Otero. 2003. “Social Networks, Social Integration, and Social Engagement Determine Cognitive Decline in Community-Dwelling Spanish Older Adults.” Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 58 (2): S93–100. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/58.2.s93.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2022 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Better School, Better Score? Evidence From a Chinese Earthquake-Stricken County

- The Effects of School Start Time on Educational Outcomes: Evidence from the 9 O’clock Attendance Policy in South Korea

- The Effect of Spousal Loss on the Cognitive Ability of the Elder

- High School Choices by Immigrant Students in Italy: Evidence from Administrative Data

- Permitting the Compensation of Birth Mothers for Adoption Expenses and its Impact on Adoptions

- Letters

- Social Efficiency of Market Entry Under Tax Policy

- Employment Protection, Workforce Mix and Firm Performance

- A Note on University Admission Tests: Simple Theory and Empirical Analysis

- Motivation in a Reciprocal Task: Interaction Effects of Task Meaning, Goal Salience, and Time Pressure

- Income Losses, Cash Transfers and Trust in Financial and Political Institutions: Survey Evidence from the Covid-19 Crisis

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Better School, Better Score? Evidence From a Chinese Earthquake-Stricken County

- The Effects of School Start Time on Educational Outcomes: Evidence from the 9 O’clock Attendance Policy in South Korea

- The Effect of Spousal Loss on the Cognitive Ability of the Elder

- High School Choices by Immigrant Students in Italy: Evidence from Administrative Data

- Permitting the Compensation of Birth Mothers for Adoption Expenses and its Impact on Adoptions

- Letters

- Social Efficiency of Market Entry Under Tax Policy

- Employment Protection, Workforce Mix and Firm Performance

- A Note on University Admission Tests: Simple Theory and Empirical Analysis

- Motivation in a Reciprocal Task: Interaction Effects of Task Meaning, Goal Salience, and Time Pressure

- Income Losses, Cash Transfers and Trust in Financial and Political Institutions: Survey Evidence from the Covid-19 Crisis