Abstract

This paper analyzes measures that limit firms’ profit shifting activities in a model that incorporates heterogeneous firm productivity and monopolistic competition. Such measures, e.g. thin capitalization rules, have become increasingly widespread as governments have reacted to growing profit shifting activities of multinational companies. However, besides limiting profit shifting, such rules entail costs. As the regulations can only focus on the means to shift profits, not on profit shifting itself, they impose costs on all firms, no matter whether these firms shift profits abroad or not. In the model, these costs force some firms to exit the market. Thus, as the resulting lower competition makes the remaining firms more profitable, regulations to limit profit shifting may even increase the aggregate amount of profits shifted abroad. From a welfare point of view, it can be optimal not to limit profit shifting by such rules.

1 Introduction

With growing financial integration, multinational companies have increasingly shifted profits abroad to reduce their tax payments. Profit shifting is an effective method to lower tax payments: Egger, Eggert, and Winner (2010) find that multinationals pay over 50% less taxes than similar domestic firms in high tax countries.[1] Governments have reacted. With the help of targeted changes to the tax code they have tried to secure their respective tax bases.

One such measure are thin capitalization rules, which aim at reducing profit shifting via internal debt.[2] In the last years, many countries have restricted the deduction of interest payments for tax purposes to a certain percentage of earnings, that is, they have implemented a general “interest cap” (Table 1 in Langenmayr, Haufler, and Bauer 2015).[3] In Italy, for example, interest expenses (net of interest income) can only be deducted if their value is less than 30% of earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization (EBITDA). Such rules are not restricted to borrowing from affiliates, but comprise all kinds of debt finance. Due to non-discrimination rules, they apply to many or all corporations, even if they are not active internationally.

The benefit of such a broad thin capitalization rule is that it effectively limits profit shifting via debt finance. However, such broadly applicable regulations also have disadvantages. They are badly targeted, as they also apply in cases that have nothing to do with profit shifting.[4] In extreme cases, it is even possible that tax payments accrue under such rules even if the firm makes a loss.[5]

As a second example, consider documentation requirements for transfer prices. Transfer pricing is often seen as the main profit shifting channel (Heckemeyer and Overesch 2013). As a countermeasure, many countries require detailed documentation from firms to justify their transfer prices for all international transactions within the firm (Lohse and Riedel 2013; Beer and Loeprick 2014). Preparing these documentations causes substantive administrative costs, especially as many countries do not have materiality thresholds (OECD 2013). Thus, these documentation requirements also affect firms who are active internationally, but do not engage in profit shifting, for example because they are only active in countries with similarly high tax rates. Further costs arise as firms hire consultants or choose inefficient strategies to comply with the regulations. For example, under a thin capitalization rule, firms may abstain from internal debt financing even when it would otherwise be optimal (e.g. for investments by affiliates who face high interest rates), and transfer pricing documentation requirements may deter firms from international expansion.

In this paper, I model such regulations to limit profit shifting, incorporating that they also impose costs on those firms that do not engage in such activities.[6] I use this model to analyze the effects of limiting profit shifting on welfare and on the aggregate sum of profits shifted abroad. Firms in the model are heterogeneous in their productivity and compete under monopolistic competition. Including heterogeneous productivity is crucial to this analysis of limiting profit shifting, as it allows to model that the effects of this specific tax policy differ among firms with different productivity levels.

The key result of the model is that strengthening a limitation on profit shifting does not necessarily lead to less profit being shifted abroad on aggregate. As the costs of such regulations force some firms out of the market, there is less competition, so that the remaining firms become more profitable. It is therefore possible that the absolute amount of profits shifted abroad increases, even though only a smaller percentage of profits can be transferred. Furthermore, additional firms may start to shift profits abroad.

Regulations to limit profit shifting have further effects, besides the ambiguous effect on the amount of profits shifted itself. As such rules force some firms to exit the market, consumers have fewer varieties from which to choose, which implies a welfare loss. The overall welfare effect depends on the market situation: If firms have high market power, it is best if governments do not limit profit shifting possibilities. If firm productivity is very heterogeneously distributed, the government should limit profit shifting, as relatively many firms engage in profit shifting activities to begin with.

Limiting profit shifting is also more likely to be favorable if the costs of profit shifting are relatively low. As such costs have fallen during the last decades due to increasing global integration, this result is in line with the empirical evidence of increased regulation against profit shifting presented above.

This paper is part of the literature that combines models of heterogeneous firm productivity, which are commonly used in international trade theory since Melitz (2003), with the analysis of tax policy. A first part of this literature studies competition for internationally mobile firms (Davies and Eckel 2010; Haufler and Stähler 2013; Baldwin and Okubo 2014). Baldwin and Okubo (2009a) and Bauer, Davies, and Haufler (2014) analyze tax-cut-cum-base-broadening tax reforms, and Pflüger and Suedekum (2013) study entry subsidies in the context of firm heterogeneity. Becker (2013) and Bauer and Langenmayr (2013) consider the interaction between taxes and foreign direct investment. Closest to this paper, Krautheim and Schmidt-Eisenlohr (2011) study profit shifting in a model with monopolistic competition among heterogeneous firms. In their model, the most productive firms shift all of their profits to a tax haven. In contrast, this paper analyzes the case when the government has a second instrument at its disposal, namely regulations that limit profit shifting. Due to such regulations, firms can only partially shift profits abroad.

A different line of literature examines specific policy measures to limit profit shifting. Hong and Smart (2010) consider if the presence of tax havens is desirable from the perspective of high-tax countries. In an extension they consider the case that the high-tax country imposes thin capitalization rules. Haufler and Runkel (2012) focus explicitly on thin capitalization rules, but in contrast to this paper, the firms’ internationalization decision is not endogenous in their model. Instead, they assume that only some firms are active internationally, and firms are otherwise identical.

This paper is structured as follows. The next section introduces the reader to the model and derives a first result on the aggregate amount of profits shifted abroad. Section 3 analyzes the optimization problems of the two countries in more detail. Some numerical simulations in Section 4 clarify the theoretical results. Section 5 concludes.

2 Model

The model consists of two countries, the “home market” and the “tax haven.” The tax haven is small; all production takes place in the home market. The economy of the home market comprises two sectors. One of them is a numeraire sector that produces a homogeneous good with a single factor (labor) under perfect competition using a technology with constant returns to scale. The final good in this sector is freely traded, its price is normalized to unity. In the second sector, firms with heterogeneous productivity manufacture differentiated goods under monopolistic competition.[7] The cost of production consists of constant, firm-specific marginal costs

The Pareto distribution implies that higher values of

Firms in the differentiated goods sector compete under Dixit–Stiglitz monopolistic competition: Each firm offers a product that is, from the consumers’ point of view, only imperfectly substitutable by other goods. Therefore, firms have some market power. Consumers’ preferences are given by

Maximizing the utility function [2] subject to the budget constraint, the demand for a particular variety of the differentiated good is given by

where

Firms facing this demand function maximize their profits. Therefore, they set their prices as a constant mark-up over marginal cost,

The price is higher if the elasticity of substitution is lower, i.e. if firms have more monopoly power.

Thus, pre-tax profits of firms are given by the following equation, with the second equality taking optimal price and quantity decisions into account[10]

The most efficient firms (i.e. the firms with the lowest marginal cost

Profits are taxed at a constant marginal rate

In reality, many regulations limit profit shifting. Such regulations have to target the means of profit shifting, i.e. transfer pricing or internal financing structures. Due to limited information, the government cannot fully differentiate between legitimate intra-firm transactions and profit shifting. It thus has to use broader rules that also hinder activities other than profit shifting.[12] A first example is thin capitalization rules, which dictate that only interest expenses of up to a certain fraction of profits can be subtracted from earnings for tax purposes for all firms. On the one hand, this limits the possibilities for profit shifting via debt. On the other hand, it increases all firms’ financing costs, as they have to comply with these rules or face higher tax rates, also if they did not intend to shift profits abroad. A second example is transfer pricing documentation requirements, which apply to all firms that are active internationally, also when they operate only in countries with similar tax rates.

In the model, the government of the home country can impose such regulations, which limit the maximum percentage of profits

Due to the fixed costs of production and profit shifting limitations, not all potential firms are productive enough to be in business. A zero-profit condition determines the cut-off value

Solving this condition for

If the tax rate in the home country or the cost of the limitation on profit shifting is higher, fewer firms are in the market. More firms are active in larger markets (as measured by

Every firm can incur a fixed cost f to shift some of its profits abroad.[15] As the most profitable firms have the most to gain from avoiding taxes, and given that the cost of profit shifting is fixed, only firms with marginal costs below a level

The left-hand side of eq. [8] represents the case in which the firm pays taxes only in the home country. On the right-hand side, it shifts profits into the tax haven. As the cost of profit shifting, f, is fixed, the firm always shifts as much of its profit abroad as is possible. It is assumed that the cost of profit shifting is not deductible from the firm’s taxable base.[17]

Inserting eq. [5] for the profits, the marginal cost level

Firms with marginal costs under

The cut-off values

Lastly, let us consider optimal quantities of the numeraire good

To look at this in more detail, consider the tax base in both countries (i.e. aggregate profits without deducting the burden imposed by the limitation on profit shifting). These are for the home country (

The tax base in the home country, eq. [11], can be interpreted as the sum of all profits (i.e. the tax base without any profit shifting,

What determines how much profit is shifted abroad on aggregate? The tax base in the tax haven rises if the tax difference between the two countries increases. It falls if firms have higher costs to shift profits (higher f) or if the demand for differentiated goods in the home market is lower (lower

Importantly, it is not always the case that a limitation on profit shifting leads indeed to less profit being shifted abroad on aggregate. Differentiating eq. [12] with respect to

The first term reflects the effects on the intensive margin, that is, the change in the amount of profit each firm shifts abroad. First, there is a direct effect

(Effectiveness of Limits on Profit Shifting) Stricter limitations on profit shifting do not necessarily lead to less profit shifted abroad on aggregate. Such regulations are only effective if the burden associated with them is relatively small.

By inspection of eq. [13] and using eqs [5], [9] and [10] it follows that

This result is driven by the market exit of some small firms, which occurs because of the compliance costs associated with regulations limiting profit shifting. To gauge the likelihood that such costs force some firms out of the market, let us consider some real-world numbers: In a survey of mid-sized US firms, Slemrod and Venkatesh (2002) find average tax compliance costs of $243,942. In a different sample, Blumenthal and Slemrod (1995) show that about 40% of compliance costs arise due to regulations concerning foreign-source income and are thus directly related to measures against profit shifting. There is also evidence that corporate tax compliance costs fall disproportionally on small firms (Sandford et al. 1989; Slemrod and Venkatesh 2002). For example, even the smallest firms in Slemrod and Venkatesh (2002) sample (firms with less than $5 million assets) report compliance costs of $105,467. Considering even smaller firms (less than 250 employees), Foreman-Peck, Makepeace, and Morgan (2006) find that tax compliance costs bear most heavily on the profitability of the smallest firms. In total, it is plausible that measures against profit shifting force some firms out of the market.

A numerical simulation in Section 4 will shed some more light on this result. First, however, I derive and discuss the conditions that determine the optimal tax rates and limitation on profit shifting in the following section.

3 Optimal Tax Policies

3.1 Optimization of the Tax Haven

The tax haven sets its tax rate

Solving eq. [14] yields the tax haven’s best response function,

The tax haven reacts to stricter limitations on profit shifting (lower

3.2 Optimization of the Home Country

The home country can decide about two policy instruments, the tax rate and the degree to which it restricts profit shifting. The government employs both instruments in a way that maximizes social welfare. The revenue raised from corporate taxation is used to finance the public good,

Note that income I consists of labor income L and (after-tax) profit income. The fixed costs of profit shifting, f, are paid by all

The first-order conditions for the optimal limitation on profit shifting and the optimal tax rate are

Due to the analytical complexity of the model, these first-order conditions cannot be solved explicitly for

First, to interpret the effects of such a regulation better, eq. [17] can be rewritten as

using that

The first term of eq. [19] captures the effect that limiting profit shifting has on consumption. This term is always positive, showing that stricter regulations (lower

The main advantage of a regulation that limits profit shifting is supposedly that less profits are shifted abroad. The change in the volume of profits shifted has two effects, which are captured in the second term of eq. [19]. First, stricter profit shifting rules increase tax revenues in the home country. Second, less income is lost to tax payments in the tax haven (from the home country’s point of view, taxes paid on profits in the tax haven are a pure loss, as they neither generate tax revenue nor profit income). Moreover, as shown by the third term of eq. [19], if fewer firms shift profits, less profit income is lost due to the fixed cost f, which firms incur to shift profits. Note, however, that it is not clear whether such a rule really leads to less profits being shifted abroad (see Proposition 1).

The fourth term of eq. [19] reflects that as fewer firms are in the economy, fewer firms incur the fixed costs of production, c. As this cost is tax deductible, this also has implications for tax revenue. Lastly, the strictness of regulations influences the severity of the burden that is associated with such a limitation on profit shifting. First, lowering

(Welfare effects of regulations to limit profit shifting) The welfare effects of strengthening a limitation on profit shifting are ambiguous and given by eq. [19]. Besides the positive effect of keeping profits in the country, such a regulation has further effects due to the market exit of some firms. This decreases competition and makes consumers worse off as they have fewer varieties from which to choose, but may increase tax revenue (see Proposition 1).

Next, let us consider the effects of a change of the tax rate in the home country,

The first term again captures the effect on consumption: If the tax rate is higher, it is more difficult to be profitable enough to stay in the market despite the excess burden of regulations to limit profit shifting. Thus, a higher tax rate implies fewer varieties in the market, thereby decreasing welfare. The second term captures the effect of a tax rate increase on tax revenues. First, there is a direct effect: For a given tax base, a higher tax rate implies higher revenues.[20] However, there is also a negative indirect effect, as the tax base decreases because the higher tax rate leads to more profit shifting. The additional profit shifting also implies that income is “lost” in the tax haven, because more profits are taxed there. This effect is represented by the third summand of eq. [20]. As more firms incur the fixed costs of profit shifting, income is further reduces, as the fourth term shows. Lastly, there also is a positive effect of market exit due to higher tax rates: As fewer firms are active, the dead weight loss of the limitation on profit shifting affects fewer firms and fewer firms have to pay the fixed costs of production.

These various effects allow no clear conclusion whether limiting profit shifting is desirable, given that it imposes costs on all firms. To see the effects of such a limitation more clearly, the next section looks at some numerical simulations of the modeled economy.

4 Numerical Analysis

4.1 Simulation of Proposition 1

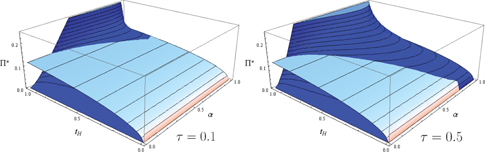

The theoretical model has shown that it is not clear that a regulation that limits profit shifting always succeeds in its aim of decreasing the amount of profits that is shifted to a tax haven (see Proposition 1). In the following, numerical simulations will illustrate this. Their results are shown in Figure 1.

The graphs clarify how the tax policy of the home country affects the aggregate amount of profits shifted abroad. It compares the aggregate value of profits shifted abroad in the case with a limitation on profit shifting (dark plane) and without such a limitation (light plane). The optimal response of the tax haven (i.e. the optimal

Aggregate profits shifted abroad, with a limitation imposed (dark plane) and without such a limitation (light plane). Parameter values:

On the two axes with the independent variables are

The graphs clarify that only for some combinations of

4.2 Simulation of Proposition 2

Lastly, let us consider the welfare effects, which were described in Section 3 and summarized in Proposition 2. A numerical analysis of the model confirms that it is not always optimal to limit profit shifting if this entail costs for all firms.

However, the simulations also show that if a limitation is welfare-increasing at all, then the government should set is as strict as possible, i.e. set

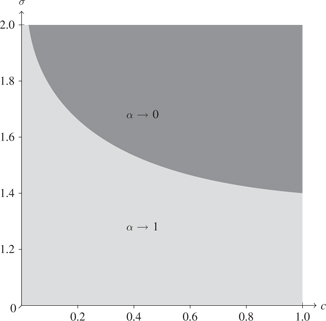

It depends on the characteristics of the economy (i.e. on parameters) whether a country chooses to prohibit profit shifting or not. Figures 2 and 3 show how market and firm characteristics influence whether profit shifting should be barred.

Prohibiting profit shifting for different market characteristics. Parameter values:

Figure 2 summarizes the results of simulations comparing welfare without a limitation on profit shifting (i.e.

Profit shifting should not be limited with a regulation that imposes costs on all firms if there are relatively many firms in a relatively uncompetitive market. If the elasticity of substitution is low, then it is more important for consumers to have as many firms in the market as possible. Hence, the utility loss of losing additional varieties is higher. In contrast to what might be the first intuition, this effect is stronger when many firms are in the market (low fixed costs c), because the additional fixed costs of limiting profit shifting become more important when other fixed costs are low.

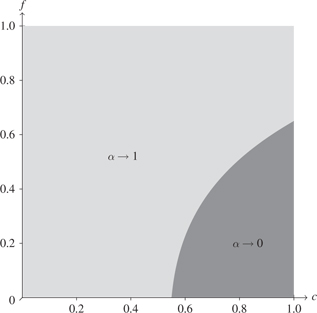

Prohibiting profit shifting for different firm characteristics. Parameter values:

A further interesting aspect is the interplay of the different firm characteristics, namely fixed costs c and the costs of profit shifting, f, which is depicted in Figure 3. It is intuitive that the benefit from limiting profit shifting is smaller if few firms shift profits due to high costs f, especially because the burden imposed by regulation to hinder this falls on all firms. However, high fixed costs c make it more likely that profit shifting should be limited. If fixed costs are high, the market consists mainly of highly profitable firms, which are more likely to shift profits abroad, thus increasing the benefit of limiting profit shifting.

The degree of firm heterogeneity also influences whether profit shifting should be prohibited or not. Heterogeneity is measured by

5 Conclusion

This article has analyzed the various effects and welfare implications of limiting profit shifting. It points out that regulations that aim to limit profit shifting may curb competition by forcing some firms out of the market. By rendering the remaining firms more profitable, it is possible that more profits are shifted abroad on aggregate after the introduction of a regulation that is supposed to prohibit or limit profit shifting.

In the introduction it was mentioned that such measures, e.g. thin capitalization rules, have increasingly been introduced or strengthened during the last years. The model also offers explanations for this by clarifying the effect of different parameters on the likelihood that limiting profit shifting increases welfare. It becomes clear that lower costs of profit shifting, which may have resulted from increasing financial integration, make limiting profit shifting more beneficial.

Funding statement: Funding: Financial support from the Bavarian Graduate Program in Economics is gratefully acknowledged.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Carsten Eckel, Clemens Fuest, Andreas Haufler, Sebastian Krautheim, seminar and conference participants in Munich and Uppsala and two anonymous referees for helpful comments and suggestions.

Appendix: Simulation Results

Table 1 states some results of numerical simulations of the model. The fixed parameters are

Results of the numerical simulation.

| Parameters | ||||||||||||||||

| c | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.5 |

| f | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

|

|

1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

|

|

1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

|

|

0.99 | 0.20 | 0.99 | 0.87 | 0.97 | 0.26 | 0.96 | 0.85 | 0.79 | 0.88 | 0.94 | 0.89 | 0.80 | 0.85 | 0.89 | 0.86 |

|

|

0.43 | 0.09 | 0.36 | 0.37 | 0.35 | 0.10 | 0.26 | 0.29 | 0.53 | 0.60 | 0.64 | 0.59 | 0.46 | 0.45 | 0.46 | 0.43 |

|

|

1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

It becomes clear that is always either optimal not to limit profit shifting at all (

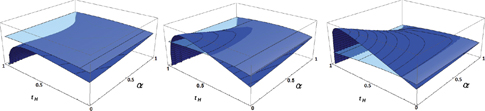

3D plots of simulated welfare levels, varying

The graphs clarify that it is not always welfare increasing to introduce a limitation on profit shifting: In the graph on the left, welfare with such a limitation is always lower than in the benchmark case where profit shifting is not limited. If such a rule should be introduced, it is optimal to set it as strict as possible (that is, at the left side of the graph).

Welfare is depicted for different values of the elasticity of substitution,

References

Axtell, R. L. 2001. “Zipf Distribution of U.S. Firm Sizes.” Science293:1818–20.10.1126/science.1062081Suche in Google Scholar

Baldwin, R. E. , and T.Okubo. 2009a. “Tax Reform, Delocation and Heterogeneous Firms.” Scandinavian Journal of Economics111:741–64.10.1111/j.1467-9442.2009.01582.xSuche in Google Scholar

Baldwin, R. E. , and T.Okubo. 2014. “Tax Competition with Heterogeneous Firms.” Spatial Economic Analysis9:309–26.10.1080/17421772.2014.930164Suche in Google Scholar

Bauer, C. J. , R.Davies, and A.Haufler. 2014. “Economic Integration and the Optimal Corporate Tax Structure with Heterogeneous Firms.” Journal of Public Economics110:42–56.10.1016/j.jpubeco.2013.12.001Suche in Google Scholar

Bauer, C. J. , and D.Langenmayr. 2013. “Sorting into Outsourcing: Are Profits Taxed at a Gorilla’s Arm’s Length?” Journal of International Economics90:326–36.10.1016/j.jinteco.2012.12.002Suche in Google Scholar

Becker, J. 2013. “Taxation of Foreign Profits with Heterogeneous Multinational Firms.” The World Economy36:76–92.10.1111/j.1467-9701.2012.01474.xSuche in Google Scholar

Beer, S. , and J.Loeprick. 2014. “Profit Shifting: Drivers of Transfer (Mis)Pricing and the Potential of Countermeasures.” International Tax and Public Finance. doi:10.1007/s10797-014-9323-2Suche in Google Scholar

Blouin, J. , H.Huizinga, L.Laeven, and G.Nicodème.2014. “Thin Capitalization Rules and Multinational Firm Capital Structure.” CESifo Working Paper Series 4695, CESifo Group Munich.10.2139/ssrn.2398815Suche in Google Scholar

Blumenthal, M. , and J. B.Slemrod. 1995. “The Compliance Cost of Taxing Foreign-Source Income: Its Magnitude, Determinants, and Policy Implications.” International Tax and Public Finance2:37–53.10.1007/BF00873106Suche in Google Scholar

Buettner, T. , M.Overesch, U.Schreiber, and G.Wamser. 2012. “The Impact of Thin Capitalization Rules on the Capital Structure of Multinational Firms.” Journal of Public Economics96:930–8.10.1016/j.jpubeco.2012.06.008Suche in Google Scholar

Buslei, H. , and M.Simmler.2012. “The Impact of Introducing an Interest Barrier. Evidence from the German Corporation Tax Reform 2008.” Discussion Paper 1215, DIW.10.2139/ssrn.2111316Suche in Google Scholar

Davies, R. B. , and C.Eckel. 2010. “Tax Competition for Heterogeneous Firms with Endogenous Entry.” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy2:77–102.10.1257/pol.2.1.77Suche in Google Scholar

Desai, M. A. , C. F.Foley, and J.Hines. 2006. “The Demand for Tax Haven Operations.” Journal of Public Economics90:513–31.10.1016/j.jpubeco.2005.04.004Suche in Google Scholar

Dreßler, D. , and U.Scheuering.2012. “Empirical Evaluation of Interest Barrier Effects.” Discussion Paper 12-046, ZEW, Mannheim.10.2139/ssrn.2112117Suche in Google Scholar

Egger, P. , W.Eggert, and H.Winner. 2010. “Saving Taxes through Foreign Plant Ownership.” Journal of International Economics81:99–108.10.1016/j.jinteco.2009.12.004Suche in Google Scholar

Foreman-Peck, J. , G.Makepeace, and B.Morgan. 2006. “Growth and Profitability of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises: Some Welsh Evidence.” Regional Studies40:307–19.10.1080/00343400600725160Suche in Google Scholar

Haufler, A. , and M.Runkel. 2012. “Firms’ Financial Choices and Thin Capitalization Rules under Corporate Tax Competition.” European Economic Review56:1087–103.10.1016/j.euroecorev.2012.03.005Suche in Google Scholar

Haufler, A. , and F.Stähler. 2013. “Tax Competition in a Simple Model with Heterogeneous Firms: How Larger Markets Reduce Profit Taxes.” International Economic Review54:665–92.10.1111/iere.12010Suche in Google Scholar

Heckemeyer, J. H. , and M.Overesch.2013. “Multinationals’ Profit Response to Tax Differentials: Effect Size and Shifting Channels.” Discussion Paper 13-045, ZEW, Mannheim.10.2139/ssrn.2303679Suche in Google Scholar

Hines, J. R. , and E. M.Rice. 1994. “Fiscal Paradise: Foreign Tax Havens and American Business.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics109:149–82.10.2307/2118431Suche in Google Scholar

Homburg, S. 2007. “Germany’s Company Tax Reform Act of 2008.” Finanzarchiv63:591–612.10.1628/001522107X269041Suche in Google Scholar

Hong, Q. , and M.Smart. 2010. “In Praise of Tax Havens: International Tax Planning and Foreign Direct Investment.” European Economic Review54:82–95.10.1016/j.euroecorev.2009.06.006Suche in Google Scholar

Huizinga, H. , and L.Laeven. 2008. “International Profit Shifting Within Multinationals: A Multi-Country Perspective.” Journal of Public Economics92:1164–82.10.1016/j.jpubeco.2007.11.002Suche in Google Scholar

Krautheim, S. , and T.Schmidt-Eisenlohr. 2011. “Heterogeneous Firms, `Profit Shifting’ FDI and International Tax Competition.” Journal of Public Economics95:122–33.10.1016/j.jpubeco.2010.10.008Suche in Google Scholar

Langenmayr, D. , A.Haufler, and C. J.Bauer. 2015. “Should Tax Policy Favor High- or Low-Productivity Firms?” European Economic Review73:18–34.10.1016/j.euroecorev.2014.10.005Suche in Google Scholar

Lohse, T. , and N.Riedel.2013. “Do Transfer Pricing Laws Limit International Income Shifting? Evidence from European Multinationals.” Working Paper 1307, Oxford University Centre for Business Taxation.10.2139/ssrn.2334651Suche in Google Scholar

Melitz, M. J. 2003. “The Impact of Trade on Intra-industry Reallocations and Aggregate Industry Productivity.” Econometrica71:1695–725.10.1111/1468-0262.00467Suche in Google Scholar

Mintz, J. M. , and A. J.Weichenrieder. 2010. The Indirect Side of Direct Investment. CESifo Book Series. Cambridge, USA: MIT Press.10.7551/mitpress/9780262014496.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

OECD. 2013. “White Paper on Transfer Pricing Documentation.” www.oecd.org/ctp/transfer-pricing/white-paper-transfer-pricing-documentation.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

Overesch, M. , and G.Wamser. 2010. “Corporate Tax Planning and Thin-Capitalization Rules: Evidence from a Quasi-experiment.” Applied Economics42:563–73.10.1080/00036840701704477Suche in Google Scholar

Pflüger, M. , and J.Suedekum. 2013. “Subsidizing Firm Entry in Open Economies.” Journal of Public Economics97:258–71.10.1016/j.jpubeco.2012.07.002Suche in Google Scholar

Sandford, C. , M.Godwin, P.Hardwick, and D.Collard. 1989. Administrative and Compliance Costs of Taxation. Fiscal Publications.Suche in Google Scholar

Slemrod, J. B. , and M.Blumenthal. 1996. “The Income Tax Compliance Cost of Big Business.” Public Finance Review24:411–38.10.1177/109114219602400401Suche in Google Scholar

Slemrod, J. B. , and V.Venkatesh.2002. “The Income Tax Compliance Cost of Large and Mid-Size Businesses.” Paper 914, Ross School of Business.10.2139/ssrn.913056Suche in Google Scholar

Weichenrieder, A. J. 2009. “Profit Shifting in the EU: Evidence from Germany.” International Tax and Public Finance16:281–97.10.1007/s10797-008-9068-xSuche in Google Scholar

Weichenrieder, A. J. , and M.Ruf2013. “CFC Legislation, Passive Assets and the Impact of the ECJ’s Cadbury-Schweppes Decision.” CESifo Working Paper Series No. 4461, CESifo Group Munich.Suche in Google Scholar

Weichenrieder, A. J. , and H.Windischbauer.2008. “Thin-Capitalization Rules and Company Responses. Experience from German Legislation.” CESifo Working Paper Series No. 2456, CESifo Group Munich.10.2139/ssrn.1299533Suche in Google Scholar

©2015 by De Gruyter

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Advances

- Turf and Illegal Drug Market Competition between Gangs

- Do Environmental Regulations Increase Bilateral Trade Flows?

- A Macroeconomic Model of Imperfect Competition with Patent Licensing

- Contributions

- Heterogeneous Effects of Informational Nudges on Pro-social Behavior

- Limiting Profit Shifting in a Model with Heterogeneous Firm Productivity

- Public Education, Accountability, and Yardstick Competition in a Federal System

- Social Status, Conspicuous Consumption Levies, and Distortionary Taxation

- Optimal Regulation of Invasive Species Long-Range Spread: A General Equilibrium Approach

- Cooperation or Competition? A Field Experiment on Non-monetary Learning Incentives

- Geographic Mobility and the Costs of Job Loss

- Supply Chain Control: A Theory of Vertical Integration

- Lexicographic Voting: Holding Parties Accountable in the Presence of Downsian Competition

- Topics

- The Transmission of Education across Generations: Evidence from Australia

- Tying to Foreclose in Two-Sided Markets

- Smoking within the Household: Spousal Peer Effects and Children’s Health Implications

- The Dynamics of Offshoring and Institutions

- Long-Run Effects of Catholic Schooling on Wages

- The Interdependence of Immigration Restrictions and Expropriation Risk

- The Effects of Extensive and Intensive Margins of FDI on Domestic Employment: Microeconomic Evidence from Italy

- Are You There God? It’s Me, a College Student: Religious Beliefs and Higher Education

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Advances

- Turf and Illegal Drug Market Competition between Gangs

- Do Environmental Regulations Increase Bilateral Trade Flows?

- A Macroeconomic Model of Imperfect Competition with Patent Licensing

- Contributions

- Heterogeneous Effects of Informational Nudges on Pro-social Behavior

- Limiting Profit Shifting in a Model with Heterogeneous Firm Productivity

- Public Education, Accountability, and Yardstick Competition in a Federal System

- Social Status, Conspicuous Consumption Levies, and Distortionary Taxation

- Optimal Regulation of Invasive Species Long-Range Spread: A General Equilibrium Approach

- Cooperation or Competition? A Field Experiment on Non-monetary Learning Incentives

- Geographic Mobility and the Costs of Job Loss

- Supply Chain Control: A Theory of Vertical Integration

- Lexicographic Voting: Holding Parties Accountable in the Presence of Downsian Competition

- Topics

- The Transmission of Education across Generations: Evidence from Australia

- Tying to Foreclose in Two-Sided Markets

- Smoking within the Household: Spousal Peer Effects and Children’s Health Implications

- The Dynamics of Offshoring and Institutions

- Long-Run Effects of Catholic Schooling on Wages

- The Interdependence of Immigration Restrictions and Expropriation Risk

- The Effects of Extensive and Intensive Margins of FDI on Domestic Employment: Microeconomic Evidence from Italy

- Are You There God? It’s Me, a College Student: Religious Beliefs and Higher Education