Abstract

Jürgen Habermas’s work is analyzed as an outstanding combination of hermeneutic sensitivity to different theories and systematic theory integration. Habermas’s theoretical method revolves around a problem-centered understanding of theory that interprets it as a response to specific problems. The methodological reconstruction of key texts shows that he used the distinction of theory and problem as an all-purpose device for interpretation, critique, and theory construction. This method is superior to other, more common ways of integrating theoretical plurality.

One of the reasons why it is difficult to build social theories of general relevance is the fragmentation of the theoretical landscape. Current social theory is challenged to develop ideas of general relevance in a landscape where theoretical interests, epistemic convictions, social-ontological assumptions, explanatory goals, and the vocabulary for the description of the social are heterogeneous. Until the 1990s, it was still plausible to describe the development of social theories as a discontinuous succession of ‘generational paradigms’ (Abbott 2001). Whereas sociology was, with perhaps an exception of a short phase of Parsonian dominance, never theoretically integrated, generational paradigms had allowed for some form of cumulative theory development ‘light’. It had allowed some scholars to spend an academic lifetime developing, challenging, or trying to refute an ambitious theoretical project that stood in clear opposition to other paradigms. However, the conflictual rivalry of competing paradigms that allowed for a partial epistemic orientation in social theory has given way to a much more heterogeneous and diffuse theoretical landscape. Currently, the contours of the theoretical debate are defined less by coherent paradigms than by loose ‘umbrella enterprises’ (Schneider 2021) that allow for much internal theoretical pluralism within.

The fragmentation of theoretical discourse is the condition of all social theoretic theorizing today. The sheer diversity of theoretical proposals, approaches, and methodologies cannot be reduced to a few fundamental epistemic disagreements anymore (see Schmitz and Schmidt-Wellenburg 2024) and there are currently no theorists with the social authority to set the agenda for most of their peers. This makes the scientific landscape more egalitarian and democratic, but it comes at the cost of orientation. Where to start if you want to continue something like the ‘sociological discourse of modernity’ (Nassehi 2009)? How to disrupt the orthodox consensus if all the priests are heretics already (see Bourdieu 1990)? While many of the reasons for fragmentation are structural, I believe that some of the ensuing problems can be addressed with a better methodology. In the following, I will first analyze how social coordination is usually achieved in contemporary sociological theory. The currently most successful formats for coordinating theoretical research seem to be social-theoretical ‘turns’, and I will explain why they fail. There is a much better alternative that is embedded in the theorizing techniques of many of the classical theorists but probably best exemplified in the work of Jürgen Habermas. I will methodologically reconstruct his theorizing technique, show its multifaceted application, and point out how it can be an effective instrument to deal with theoretical pluralism in a constructive fashion.[1]

1 Turning Down the Turns

Many established ways of approaching theoretical diversity are inadequate. Two widely-used practices are eclecticism and theorizing within so-called social-theoretical ‘turns.’ Eclectic theories selectively adopt concepts and claims from various traditions wherever they seem appropriate, but they ignore the question of theoretical compatibility. This leads to the use of theoretical terminology as a mere collection of theoretical terms, preventing the development of a clear perspective. The incoherence of eclecticist thought prevents it from playing a meaningful role in coordinating research. Even in the best case, eclecticist theorizing will suffer from the unclear meaning of its theoretical concepts; in the worst case, theories are reduced to their function as decorative material for catchy citations.

Turns are more sensitive to the problem of theoretical coherence. They concentrate most of their efforts on assembling elements drawn from different theories that are compatible with each other so that they can form a basis for new theoretical developments. Modeled after the influential linguistic turn in philosophy, social-theoretical turns primarily shift toward specific assumptions about the social. There are turns to many things: to relational ontology, to culture, to the visual, to affect, and so on, usually with some ambiguity whether the turners are proclaiming a general social theory or whether they just think a given subject is of special importance. One of the most influential turns in social theory – the turn to practice (Schatzki, Knorr-Cetina, and von Savigny 2005) – is a suitable example of the limits of this approach. It explicitly addresses theoretical diversity and tries to distill something like a common core in recent social theory. It arrives as a list of social theoretical ‘basic elements’ that are shared between different theoretical traditions (Reckwitz 2003; Schatzki 2002; Hui, Schatzki, and Shove 2017). Schatzki lists practical understandings, rules, a teleoaffective structure, and general understandings as elements of the infrastructure of practice (Schatzki 2002, 77). Reckwitz mentions bodily movements, things, practical knowledge, and routine (Reckwitz 2002). The goal of finding these common denominators among heterogeneous theories is to establish unity within diversity and thereby provide orientation for collective theoretical work.

However, this search for common theoretical ‘basic elements’ has two decisive disadvantages. First, the turn is naturally drawn to the smallest common denominator between social theories and to the most abstract way of conceptualizing the basic elements. If Bourdieu and the late Foucault are both claimed for the relevancy of ‘the body’ in social theory, all differences between the Foucauldian and the Bourdieusian concept of the body are erased and mashed into one. By subsuming more and more theories, the turn loses theoretical content instead of gaining it because its implicit method of theory comparison tends to the smallest common denominator. Second, the theoretical common ground is too narrow a basis for effectively coordinating research efforts. There is maybe some consensus about ‘what’ to look for among the turners, but they do not share a common logic of research; there is no shared idea about ‘how’ to do theory. The typical career of a turn starts by being proclaimed as an emerging social theoretic consensus only to quickly unravel into a multitude of very different appropriations. It ends after some time when its advocates realize that the central theoretical concepts of a turn have become empty gestures, offering little to no guidance for coordinating research (Anicker 2022).

2 An Alternative: Hermeneutic, Problem-Centered Theorizing

Given the challenges posed by theoretical fragmentation, Habermas offers a compelling alternative. A tendency to isolate individual aspects in the reception has obscured one of the dimensions in which it is particularly worthwhile to learn from Habermas: his integrative method of linking systematic, problem-centered theory-building with hermeneutic interpretation. Habermas’s work is characterized by integrating heterogeneous intellectual movements and facilitating dialogue among research traditions that develop without reference to one another.

Habermas is strongly influenced by the tradition of philosophical hermeneutics. While he asserts the emancipatory significance of reflection against its conservative implications (Habermas 1971), he nevertheless adopts its fundamental stance. In particular, he is influenced by a historical-interpretative mode of thought that treats the continuation of tradition and innovation as mutually dependent and understands the present as a site for selectively and creatively engaging with traditions (Habermas 1988a, 23–4). Consequently, Habermas systematically regards the history of theory as a resource for contemporary theoretical endeavors. The genealogy of theory renders the contemporary theoretical self-understanding transparent in its contingent historicity. Unlike Foucault, Habermas does not aim at the revelatory effect of exposing arbitrariness beneath the veil of necessity, but rather at rediscovering forgotten alternatives. In Knowledge and Human Interest the development of theory is itself seen as some kind of learning process whose “abandoned stages” can be retraced to “recover the forgotten experience of reflection” (Habermas 2001, 9). Awareness of past solutions to problems of scientific world-disclosure and world-explanation allows one to distance oneself from the present and draw alternative lessons from the history of reflection (see also Habermas 2019, 23–39). In addition to the ‘vertical’ historicist orientation toward the history of ideas, he also branches out his theory horizontally across many different fields of scholarship. His material interest in finding “the unity of reason in the plurality of its voices” (Habermas 1988b) forced Habermas to become a truly interdisciplinary scholar, fluently moving between philosophy and multiple social sciences. Operating orthogonally to disciplinary differentiation, he had to integrate thoughts from very different fields that were built on heterogeneous theoretical underpinnings and epistemic interests.[2]

Habermas was, therefore, perhaps more than most of his contemporaries, confronted with the problem of theoretical pluralism. Being committed to the conviction that the discourse of the Western enlightenment and even its theological precursors can be reconstructed as a complex cultural learning process (Habermas 2019), he needed to cover vast terrain in the history of ideas. Although Habermas himself has made only cursory remarks about his method and has never positioned himself as a methodologist of theory construction, his writings do reveal an underlying method for productively processing theoretical material. This method can be understood as a combination of hermeneutic interpretation and systematic, problem-centered theory integration. In The Theory of Communicative Action (TCA), Habermas calls this “the history of theory with systematic intent” (Habermas 1981, 201). He does not view ‘classical’ theories as outdated precursors but rather as still-relevant attempts to capture key aspects of the emergence of modern society. While these theories are historically contextualized, they are nevertheless treated as substantively contemporary. This dual movement – taking theories seriously as interlocutors while situating them in the historical context of influential intellectual movements – commits Habermas to a systematic, comprehensive, and critical reading of classical theory.

The guiding assumption of contemporaneity implies treating these theories as contributions to still-relevant questions, which may be incomplete or no longer fully adequate in certain respects but whose insights have helped shape our current level of reflection. Existing theories have something to teach us because they reveal the possibilities open to thought. From their history – both their achievements and their errors – we can learn which positions we can still uphold today and which questions remain relevant within the disciplinary horizon. The history of theory thus becomes readable like a Bildungsroman, whose stages represent necessary steps in the development of thought. Instead of distancing prior theoretical thought, the effect of Habermas’s theoretical technique is to present his theory as its natural culminating point. In this regard, it is similar to the Hegelian spirit that propels itself forward by negating its prior phases. However, in terms of the thoroughness with which he addresses prior theoreticians’ work, he is more on the side of hermeneutics and especially the dialectics of question and answer, as it was developed by Gadamer (1960), whereas the systematicity of his convergence theorizing resembles Parsons’s strategy in his seminal study on action theory (Parsons 1937). His method, though likely more inherited than explicitly chosen, represents the most advanced synthesis of hermeneutics and systematic theory-building to date. While certainly something gets lost by abstracting from the thicket of material premises that underly Habermas’s work, there is also clarity and orientation to be gained by distilling the methodical core of his technique of theorizing.

3 Theory and Problem as the Methodical Foundation of Habermas’s Method

The following explication of a theoretical method is not intended as a revolutionary proposal. Rather, it recalls an aspect of theoretical practice that once belonged to the tacit knowledge widely shared among theorists, but which has receded into obscurity in recent decades. This implicit method of productively engaging with heterogeneous social theories can be traced across a wide range of thinkers. Its significance was recognized by figures such as Merton and Parsons, Bourdieu and Luhmann, Popper, Toulmin, Gadamer, and many others (Anicker 2020; Schneider 1991). Nonetheless, I argue that Habermas’s theoretical practice deserves particular attention, as his work is especially attuned to the challenges posed by theoretical pluralism.

At the core of Habermas’s method lies a problem-based understanding of theory that requires an analytic distinction between a theory and the problem that it addresses. According to this metatheoretical paradigm, to understand a theory means to understand how it can be seen as an answer to a question or, alternatively, a solution to a problem (for the general applicability of this scheme, see Anicker 2024). So, what does it mean to say that theories are answers to questions? It means that a theory is something that has a purpose; it is directed to something. This problem-dependence of interpretation is taken to be not only a contingent method of theory interpretation but an explication of the very concept of understanding (Gadamer 1960). Thus, this is the method that everyone is already using to some degree, whether they realize it or not. However, unconscious users are like intuitive reasoners – getting it right in many cases but prone to confusion and error when faced with complexity. The directedness of solutions to problems is essential for scientific theories. A mere understanding of theories as systems of interconnected propositions is insufficient because we can only understand the theory if we understand its purpose. Conversely, we could not make sense of the claim that someone understood a theory but not what it is for.

The relation between theory and problem is one of mutual interpretation. The problem provides the framework of relevance within which the theoretical vocabulary of a theory acquires meaning – it articulates the cognitive interest and specific presuppositions of the theory (see e.g. Abend 2020). It also restricts the frame of relevancy: there are many true and generally interesting propositions in a theory that are still not relevant for its problem-based interpretation. At the same time, theories interpret their central problem by framing it in a particular way. For example, Talcott Parsons was very explicit that the central problem of his sociology is the explanation of social order (Parsons 1937). This makes the theory interpretable as a solution to the problem of order, while the meaning of the problem of social order gets specified by Parsons’ theoretical commitments as an explanation of the interpenetration of normative values and behavioral tendencies (Münch 1988).

While the analytic distinction of theory and problem is, first of all, a device for theory interpretation, it is also of excellent use for theory comparison and theory integration (Anicker 2017; Schneider 1996). Scientific problems can usually be formulated at a level of generality that allows different theories to be understood as competing or complementary solutions to the same problem. It makes a difference whether you think of the problem of social order from a Parsonian, a Bourdieusian, or an ethnomethodological perspective – but there is certainly some sense in claiming that these perspectives all have something to say about this problem. They share the problem, even if their vocabularies are incommensurable.[3] In contrast to the quest for common theoretical commitments in social-theoretical turns, the distinction between a theory and its central problem makes it possible to observe convergent problems between theories without necessarily claiming a theoretical convergence between them. The theoretical assumptions need not be translatable into one another. This distinction between a theory and its problem leads to similar advantages as the switch from substantial concepts to function concepts on the level of theoretical propositions (Cassirer 1910). If you compare theories by asking, ‘What do two theories have in common?’, you will maybe be able to find some common ground, but it will shrink if you extend your analysis to more theories. The more you include, the more trivial your theoretical synthesis becomes (just like species concepts become thinner and less informative the more different kinds they subsume). We saw this problem in the example of the turns. A problem-centered view on theories allows to refer theories to each other on a very general level (problem convergence) without losing specificity on the level of the theoretical vocabularies. Theoretical concepts channeling thought in specific directions are just as central as the problem awareness guiding reflection. Generalizing systematization and detailed hermeneutics can be pursued simultaneously. Thus, relations among different theories can be established, even if there are few material assumptions they share – they speak in different tongues to the same question.

Habermas employs the differentiation between problem statements and theory with great flexibility. In the following, I will draw on examples from his work to illustrate different uses he makes of the hermeneutic method of theory comparison and theory development. There are four main functions that the theory-problem-scheme serves in Habermas’s theorizing: they are, first, to interpret theories, second, to provide an abstract overview over the theoretical discourse, third, to criticize theories in the light of insufficient problem solutions and, fourth, to systematically integrate theories by relating their problems and vocabularies to each other. Usually, these functions blend into each other seamlessly in Habermas’s writings, but the following examples are picked with an eye to them foregrounding one function above others for illustrative purposes.

3.1 Theory Interpretation and Recombining Theories and Problems

Habermas uses the distinction of theory and problem constantly to interpret theories. By measuring the theories against standards inherent to their objectives, the interpretation gains an objectivity that detaches it from the authors’ subjective self-understanding. Habermas can claim, for example, that he understood Mead’s theory “maybe a bit better” (Habermas 1988c, 215) than the author himself. The objectifying effect of seeing theories as solutions to problems allows seeing the vocabulary of any theory as one option among others that could be improved upon or even abandoned in favor of a superior alternative. In The Theory of Communicative Action (TCA), Habermas takes up Mead’s problem statement – how does symbolic gesture-based communication emerge from a stimulus-response-based form of behavioral coordination? – but draws on Wittgenstein’s rule-following theory to clarify this transition from behavior to rule-governed (symbolic) action (cf. Habermas 1981, 27–40). Wittgenstein’s conceptual framework allows for a more precise answer to Mead’s question – a simple argumentative move that would be inaccessible without the distinction between theory and problem statement.

3.2 Overview and Ordering of Theoretical and Empirical Discourses

Habermas’s ability to systematize huge swaths of literature and reconstruct debates is unparalleled in sociological theory. This skill benefits greatly from the problem-focused scheme of interpretation. A simple example can be found in the introduction to The Philosophical Discourse of Modernity. Habermas employs an abstract problem to establish a shared question that the philosophical discourse of modernity is supposed to revolve around. Modern thinking, according to Habermas, is committed to the immanence of philosophical normativity and the loss of transcendent certainty of epistemic, normative, and aesthetic standards – modernity must draw its normativity from itself (cf. Habermas 1988a, 15). He refines this problem by restating it in terms of the question of how cultural and societal modernization relate to each other.[4] Cultural modernization refers to the institutions of modernity (law, education, science, religion, and so on), while societal modernization means the systemic rationalization of technology, administration, and the economy. The central question thus becomes in what way the participants in the philosophical discourse of modernity conceptualize cultural and systemic development – and whether they still see processes of cultural learning in place that can be defended as a source of legitimacy (cf. Habermas 1988a, 31). This problem focus allows Habermas to provide a frame that can be alluded to throughout his complex study of different authors, to present the contemporary philosophical discourse of modernity in terms of the opposition between “neoconservative” and “postmodern” currents (Habermas 1988a, 9–13), and thereby prepare the ground for his own theoretical positioning.

3.3 Constructing Polarities Between Theories to Find Some Middle Ground

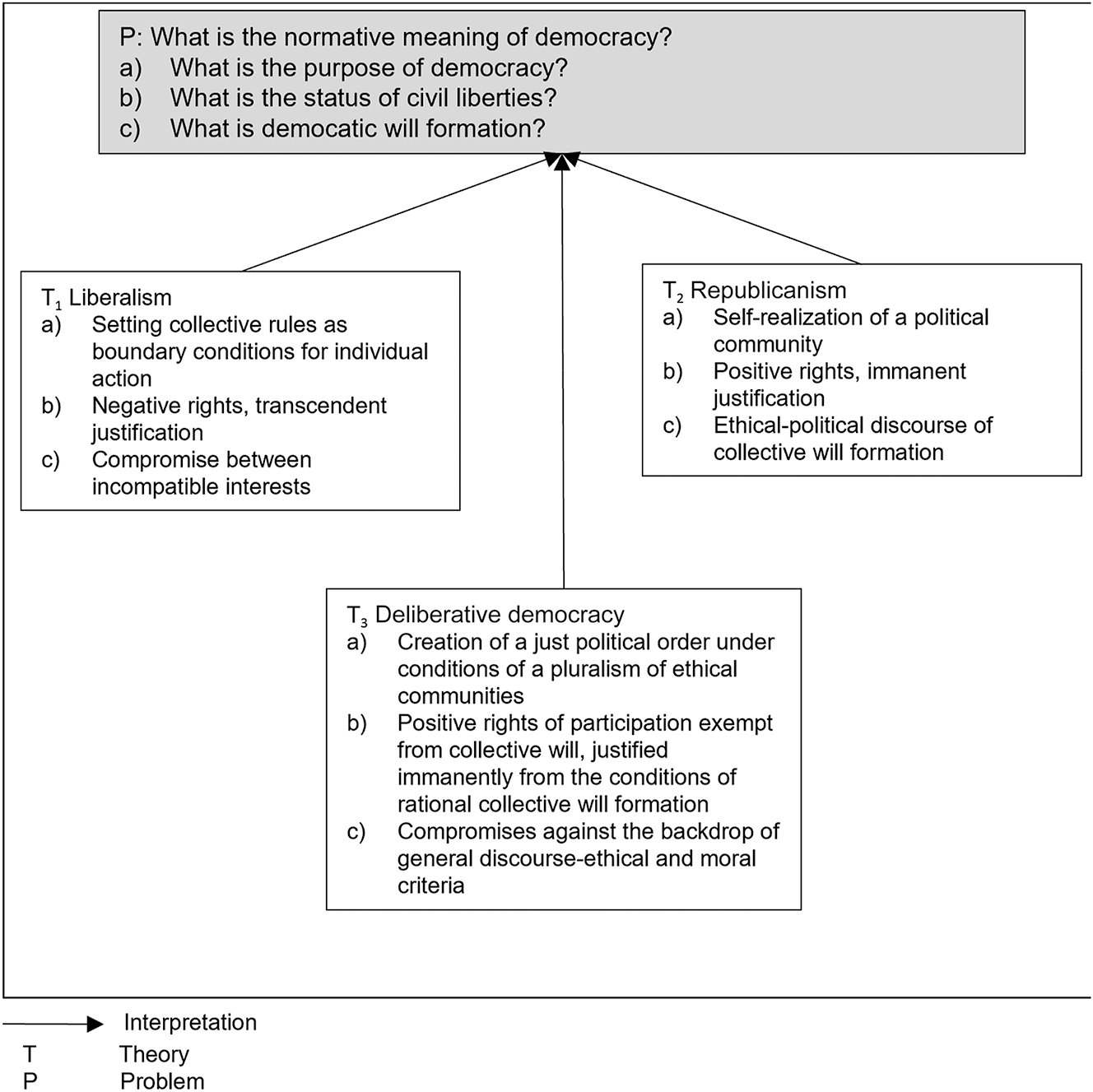

Habermas uses problem-based comparisons between theories not only for ordering discourse but also to develop his position as a synthesis of opposing traditions that keeps their strengths and avoids their weaknesses (similar to Hegelian Aufhebung). This is particularly evident in the influential article Three Normative Models of Democracy (Habermas 1994). In this paper, Habermas delineates his normative foundation for deliberative democracy theory by presenting it as a mediating synthesis between the liberal and republican traditions.

Liberalism and republicanism are interpreted as competing and mutually incompatible responses to the question of the normative meaning of democracy. While republicanism conceives democracy as a form of self-realization for an ethical community, liberalism views it as a regulatory mechanism for managing shared and conflicting interests within a collective of private individuals. Whereas liberalism conceptualizes civil rights as ‘negative’ rights – protections against state intervention – republicanism frames rights, particularly participatory rights, as enabling mechanisms for political participation; they are ‘positive’ rights that serve as both expressions and instruments of a political community’s self-realization. These positions also reflect differing views on the foundation of civil rights: Whereas liberals claim an extralegal basis for fundamental political rights, republicans see them as rooted in the collective will of a political-ethical community (Habermas 1994, 1–3).

Habermas builds upon this problem-based opposition between liberal and republican democratic theory to introduce deliberative democracy as a third alternative – one that does not simply stand alongside the other two but instead synthesizes and transcends their conflicting tendencies. His theoretical approach is positioned within the conceptual space revealed by the mutual critique of the two traditions. Liberals might argue that republicanism fails to sufficiently secure the principles of the rule of law because legal rights are treated as a contingent product of collective will-formation. However, the inverse critique of liberalism holds that the pre-political validity of fundamental freedoms cannot ultimately be justified within the secular discourse of modernity that knows no other principles than those inherent in collective will formation.

The theory of deliberative democracy situates itself between these two positions: It exempts fundamental rights from arbitrary democratic decision-making but does not ground them in a pre-political notion of reason. Rather, it embeds their justification within the constitutive conditions of political discourse itself (see also Habermas 1989, 1992). A similar approach applies to the collective aims of democracy and the mechanisms of political consensus-building. While deliberative democracy rejects the strong consensus expectations of republicanism concerning a collective democratic way of life, it also avoids conceding to liberalism’s insistence on the irreconcilability of conflicts of interest. Whereas liberalism sees democracy as a process of bargaining between private interests, republicanism envisions it as the formation of a collective will through ethical-political discourse. Deliberative democracy is then introduced as a mediating (but more liberal-leaning) position: a process of compromise formation that is guided by collective discourse-ethical principles.

The following schema provides a (simplified) overview of the resulting contrast between the traditions and the development of the deliberative model from the opposition between republicanism and liberalism (Figure 1).

Deliberative democracy as middle ground (created by the author).

3.4 Theory Critique

Habermas employs problem-oriented theory interpretation for critique: He examines to what extent existing theories can systematically address those problems whose relevance emerges from the historical development of the discipline – and he bases his critique on the diagnosis of either insufficient problem awareness or inadequate problem resolution. A good example is a manuscript whose German title can be translated as On Theory Comparison in Sociology: The Case of Theories of Social Evolution (Habermas 1995).[5] It was originally presented as part of a joint lecture with Klaus Eder at the 1974 Kassel Conference of Sociologists. The topic of the lecture was set by the broader theme of the conference: the explanation of social evolutionary processes. Other speakers on the same topic included Niklas Luhmann, Karl-Dieter Opp, and Karl Hermann Tjaden, whose system-theoretical, behavioral-theoretical, and Marxist alternatives provided points of contrast for Habermas.

Habermas utilizes this for critically delineating his approach from competing theories. He begins his lecture with the assertion that no adequate theory of social evolution has yet been developed (129). He then uses his contribution as a programmatic outline, deriving his problem statement precisely from the deficiencies of existing approaches. In his analysis (likely also influenced by the composition of the Kassel panel), he considers three competing approaches to his problem:

Historical Materialism (Tjaden)

Rational Choice Theory (Opp)

Functionalist Systems Theory (Luhmann)

Habermas makes his first theoretical commitment by adopting the goals and also, more or less, the problem statement of historical materialism – the theory of social evolution should be able to explain developmental stages of society (he mentions high cultures, class societies, and global society, cf. 129–39). However, this affirmation of the problem statement is compatible with a clear rejection of historical materialism’s specific problem solution:

I do not see, on the other hand, why these intentions should oblige me to more or less dogmatically adopt the construction principles and specific assumptions of a theory rooted in the 19th century … (130)

Thus, Habermas pursues historical materialism not by adhering to its theoretical assumptions but by continuing its problem statement. This way of defining the problem is then used as a yardstick for his own theory development and for the critique of the rivaling approaches presented in Kassel. His claims are exemplary for the differentiated uses of the distinction of theory and problem for critique:

Rational Choice Theory (that he calls ‘behavioral theory’) fails to even pose the relevant problems

Historical Materialism poses the right problems but fails to solve them due to its outdated Marxist theoretical assumptions.

Systems Theory fails to theoretically justify the relationship between problem and solution

This array of critical remarks exhausts the basic logical possibilities of the scheme of theory and problem: The critique can either target the problem awareness of a theory (that may be unable to address relevant problems), or the solution to the problem (e.g. untenable theoretical claims or theoretical incoherence) or the relation between theory and problem. This latter option, that Habermas uses in his criticism of Systems Theory is maybe the most interesting. Habermas argues that Luhmann’s theory is ‘overly abstract,’ to the point that “the selection of reference problems can no longer be theoretically justified” (141). The implicit criterion of this critique is the understanding, that theories need to coordinate and specify their reference problems through their social-theoretical vocabulary in such a way that the selection of problems is constrained rather than left arbitrary. In his view, good theory construction ought to be conceived as a process of gradually reducing theoretical arbitrariness by committing to increasingly specific problem statements and solutions.

3.5 Theory Integration and Theory Construction

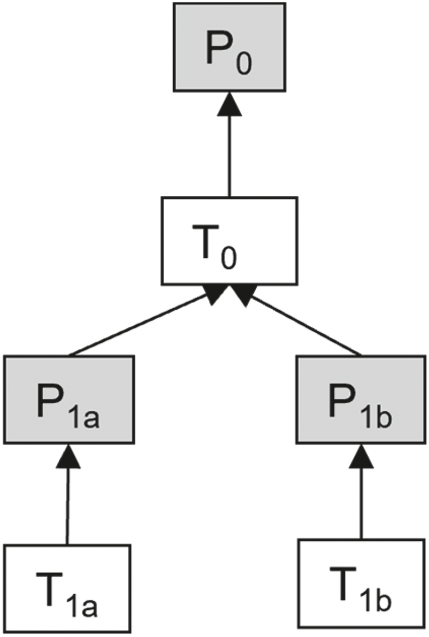

The problem-oriented integration of theories is of central importance for the theoretical architecture of The Theory of Communicative Action (TCA). A key methodological advantage in the problem-oriented search for convergence is that theories can be connected not only through the similarity of their fundamental categories or merely shared reference problems (theories as responses to the same question) but also through a more abstract integration of their reference problems – understanding theories as responses to different questions that, nonetheless, relate to a broader epistemic interest (see the following scheme) (Figure 2).

Complex relation between two theories (created by the author).

In the scheme below, two theories T1a and T1b are not related by mapping their theoretical vocabularies onto each other (which may be incommensurable), but rather by demonstrating how their respective problems arise as natural consequences of a more general theory (T0) that responds to an overarching theoretical problem. This possibility of problem-mediated theory integration (for problem-mediated theory comparison, see Anicker 2017) allows for quite complex theoretical constructions. I will use one of Habermas’s more challenging theoretical ideas as an example for this: The dual concept of society. My primary interest here is not the (undoubtedly controversial) conceptual design itself, but rather the method of theory integration underlying it.

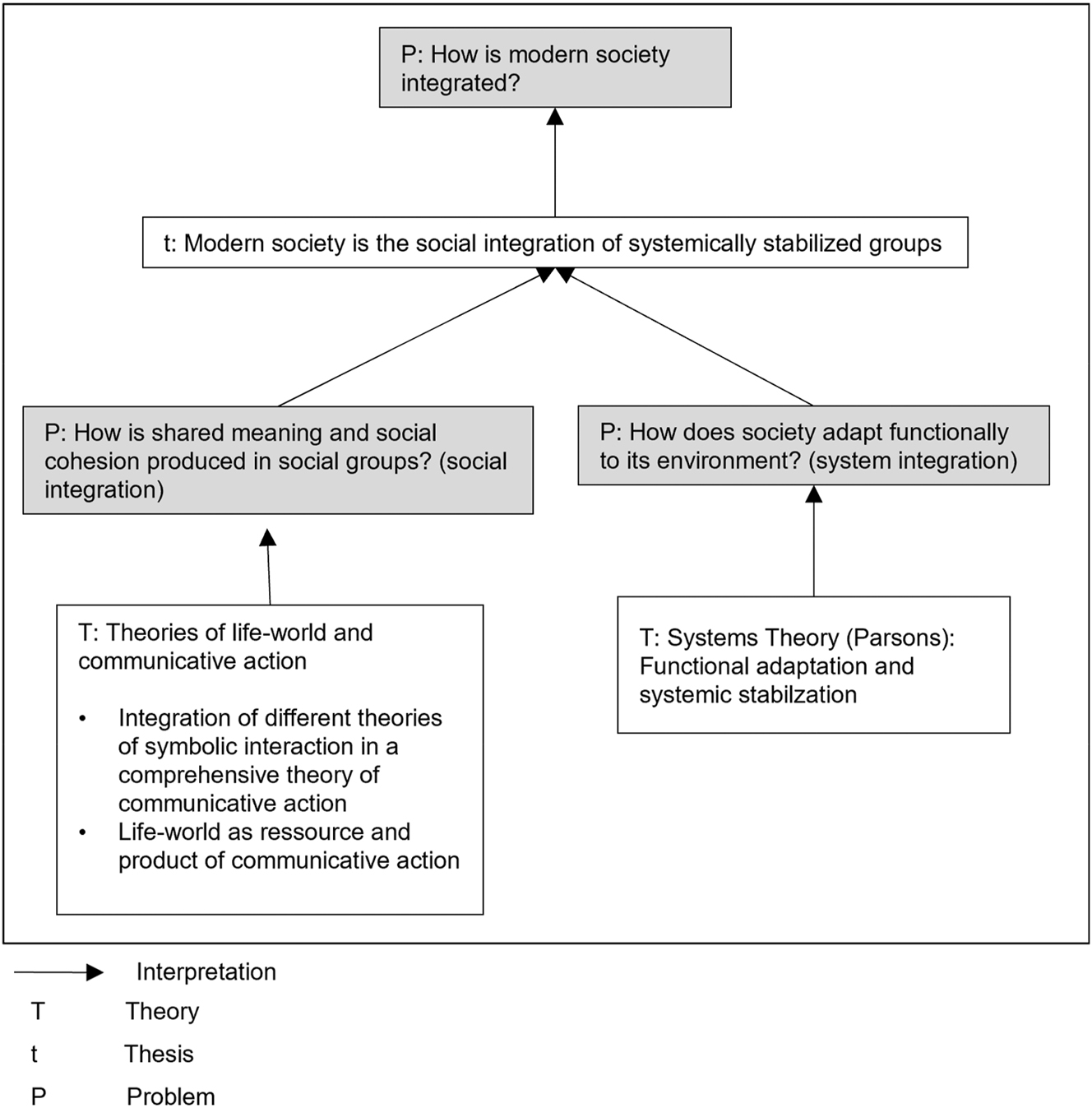

What Habermas attempts to do in the TCA is to reconcile two traditions in sociology that are usually conceived as opposing methodological principles: holistic functionalism and individualist action theory. The theory of the society in the TCA emerges from the synthesis of these two traditions. Both theoretical traditions are interpreted in detail and critically on the level of their most influential authors and only brought together in a second step of systematic theory development. This division of labor between hermeneutics and systematicity is reflected in the structure of the TCA. While most of the chapters contain hermeneutically sensitive but also critical discussions of philosophical and sociological traditions, the systematic theory development takes place in the Zwischenbetrachtungen (interim reflections). In the hermeneutic parts of the TCA, Habermas uses the form of theory critique that is familiar from the above scheme of problem-based criticism. To integrate both perspectives, he (a) contests both theories’ claims that both already provide the foundations of a general social theory and (b) tries to interpret them in ways that make them compatible with each other. Through the problem-based critique of both theoretical strands, he tries to show that action theory reaches its limits when society is conceived exclusively as a lifeworld. System theoretic functionalism, on the other hand, needs action theory to identify learning mechanisms and conditions of functional differentiation in the life-world (see already Habermas 1995, 134). On their own, Habermas claims, they do not offer a satisfactory theory of modernity. His interpretation of the traditions suggests that they have mutual blind spots and a potential for complementarity: One is strong where the other is weak.

The traditions are brought together in the second interim reflection of TCA. Habermas integrates the competing theoretical paradigms of systems theory and theories of action by relating them to specific problem areas within a “two-tiered” social theory (Habermas 1981, 225–93). On the level of theoretical convergence, he argues that action theory is naturally drawn toward a paradigm of communicative action (and thereby away from individual actors as the methodological reference point of analysis), which makes it more compatible with the methodological premises of functionalism (Habermas 1981, 182–228). By adopting the theoretical thesis that societies should be understood as “systemically stabilized networks of action within socially integrated groups” (1981, 228), Habermas effectively splits the classical problem of social order into two distinct variants (see already Lockwood 1964): the problem of system integration (Parsons, and also Marx) and the problem of social integration (action theory, especially communicative action).

Action theories, especially in their symbolic interactionist form, are applied only to the problem of social integration; the symbolic reproduction of ‘society-as-lifeworld’, whereas Parsons’s Systems Theory serves to describe especially the stabilization forms of order that escape the intentional horizon of society’s members – ‘society-as-system’. The reframing of the problems of both theoretical strands as sub-problems of a dual concept of society allows for a form of intellectual division of labor, while maintaining the distinctiveness of the respective theoretical vocabularies and their different problem focus. The following diagram provides a (highly simplified) overview of the resulting theory architecture (Figure 3).

Habermas’s theory of society as a problem-based theory synthesis (created by the author).

4 Conclusions

The fragmentation of theory in philosophy, sociology, and many other social sciences has reached proportions that require considerable synthetic effort for anyone who wishes to incorporate theoretical diversity productively and do theory that is relevant beyond a small niche. However, the widespread tendency to coordinate theoretical research through the orchestration of social-theoretical turns is ill-suited to this task. I argued that Habermas’s interdisciplinary and historicist theorizing offers a superior model for combining hermeneutic sensitivity to the nuances of theories with strong systematic-theoretical ambitions.

I reconstructed the core of Habermas’s theoretical method as revolving around the distinction of theory and problem. Theories are understood as solutions to problems. This separates a theory’s meaning from the intentions of its author and makes relating and comparing theories to each other possible. The methodological reconstruction of some key texts shows that Habermas used this as an all-purpose device: for interpretation, for critique, and for theory construction. By relating different theoretical positions to a common problem and selectively integrating them, a form of theory development emerges that builds upon existing ideas but creates something new through the comparison and critique of these positions. Habermas inherited many aspects of his practical theoretical understanding from predecessors. Nonetheless, there is no doubt that his work, due to the transparency of its theory construction and the breadth of its syntheses, stands as an impressive example of the possibilities of hermeneutic-systematic theory-building.

References

Abbott, Andrew Delano. 2001. The Chaos of Disciplines. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.Search in Google Scholar

Abend, Gabriel. 2020. “Making Things Possible.” Sociological Methods & Research: 0049124120926204. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124120926204.Search in Google Scholar

Anicker, Fabian. 2017. “Theorienvergleich als methodologischer Standard der soziologischen Theorie.” Zeitschrift für Soziologie 46 (2): 71–88. https://doi.org/10.1515/zfsoz-2017-1005.Search in Google Scholar

Anicker, Fabian. 2020. “Theoriekonstruktion durch Theorienvergleich – eine soziologische Theorietechnik.” Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie 72: 567–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11577-020-00715-x.Search in Google Scholar

Anicker, Fabian. 2022. “Wohin wenden nach den Turns? Eine wissenschaftssoziologische und forschungslogische Betrachtung am Beispiel des „Turn to Practice“.” Zeitschrift für Soziologie 51 (4): 350–64. https://doi.org/10.1515/zfsoz-2022-0020.Search in Google Scholar

Anicker, Fabian. 2024. “Der Kern des Theorizing – zur allgemeinen Methode theoretischer Forschung.” In Die Praxis Soziologischer Theoriebildung, edited by Fabian Anicker, and André Armbruster, 279–309. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.10.1007/978-3-658-44055-8_11Search in Google Scholar

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1990. Homo Academicus. Cambridge: Polity Press.Search in Google Scholar

Cassirer, Ernst. 1910. Substanzbegriff und Funktionsbegriff. Untersuchungen über die Grundfragen der Erkenntniskritik. Berlin: Bruno Cassirer.Search in Google Scholar

Gadamer, Hans-Georg. 1960. Wahrheit Und Methode: Grundzüge Einer Philosophischen Hermeneutik. Tübingen: J.C.B. Mohr.Search in Google Scholar

Habermas, Jürgen. 1971. “Zu Gadamers ,Wahrheit und Methode.” In Hermeneutik Und Ideologiekritik, edited by Karl-Otto Apel, 45–56. Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp.Search in Google Scholar

Habermas, Jürgen. 1981. Theorie des Kommunikativen Handelns. Band 2. Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp.Search in Google Scholar

Habermas, Jürgen. 1988a. Der Philosophische Diskurs Der Moderne. Zwölf Vorlesungen. Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp.Search in Google Scholar

Habermas, Jürgen. 1988b. “Die Einheit der Vernunft in der Vielfalt ihrer Stimmen.” In Nachmetaphysisches Denken. Philosophische Aufsätze, 153–86. Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp.Search in Google Scholar

Habermas, Jürgen. 1988c. “Individuierung durch Vergesellschaftung. Zu George Herbert Meads Theorie der Subjektivität.” In Nachmetaphysisches Denken, 187–241. Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp.Search in Google Scholar

Habermas, Jürgen. 1989. “Volkssouverränität Als Verfahren.” Merkur 43 (484): 465–77.Search in Google Scholar

Habermas, Jürgen. 1992. Faktizität Und Geltung. Beiträge Zur Diskurstheorie des Rechts und des demokratischen Rechtsstaats. Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp.Search in Google Scholar

Habermas, Jürgen. 1994. “Three Normative Models of Democracy.” Constellations 1 (1): 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8675.1994.tb00001.x.Search in Google Scholar

Habermas, Jürgen. 1995. “Zum Theorienvergleich in der Soziologie: am Beispiel der Theorie der sozialen Evolutionstheorie.” In Zur Rekonstruktion Des Historischen Materialismus. 6th ed. edited by Jürgen Habermas, 129–43. Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp.Search in Google Scholar

Habermas, Jürgen. 2001. Erkenntnis und Interesse. Mit einem neuen Nachwort. Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp.Search in Google Scholar

Habermas, Jürgen. 2019. Auch Eine Geschichte Der Philosophie, Vol. 2. Berlin: Suhrkamp.Search in Google Scholar

Hui, Allison, Theodore R. Schatzki, and Elizabeth Shove, eds. 2017. The Nexus of Practices: Connections, Constellations, Practitioners. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781315560816Search in Google Scholar

Kuhn, Thomas S. 1982. “Commensurability, Comparability, Communicability.” PSA: Proceedings of the Biennial Meeting of the Philosophy of Science Association 1982 (2): 668–88. https://doi.org/10.1086/psaprocbienmeetp.1982.2.192452.Search in Google Scholar

Lockwood, David. 1964. “Social Integration and System Integration.” In Explorations in Social Change, edited by George K. Zollschan, and Walter Hirsch, 244–57. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.Search in Google Scholar

Münch, Richard. 1988. Theorie des Handelns: Zur Rekonstruktion der Beiträge von Talcott Parsons, Emile Durkheim und Max Weber. 1. Aufl. Suhrkamp-Taschenbuch Wissenschaft 704. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.Search in Google Scholar

Nassehi, Armin. 2009. Der Soziologische Diskurs Der Moderne. Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp.Search in Google Scholar

Parsons, Talcott. 1937. The Structure of Social Action. A Study in Social Theory with Special Reference to a Group of Recent European Writers. New York: Free Press.Search in Google Scholar

Reckwitz, Andreas. 2002. “Toward a Theory of Social Practices: A Development in Culturalist Theorizing.” European Journal of Social Theory 5 (2): 243–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/13684310222225432.Search in Google Scholar

Reckwitz, Andreas. 2003. “Grundelemente einer Theorie sozialer Praktiken: Eine sozialtheoretische Perspektive.” Zeitschrift für Soziologie 32 (4): 282–301. https://doi.org/10.2307/23772286.Search in Google Scholar

Schatzki, Theodore R. 2002. The Site of the Social : A Philosophical Account of the Constitution of Social Life and Change. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=91595&site=ehost-live (accessed July 30, 2020).Search in Google Scholar

Schatzki, Theodore R., Karin Knorr-Cetina, and Eike von Savigny, eds. 2005. The Practice Turn in Contemporary Theory. London: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Schmitz, Andreas, and Christian Schmidt-Wellenburg. 2024. “Viele Theorien, ein, Theorizing’? Eine Rekonstruktion des deutschen Feldes soziologischer Theorie.” In Anicker and Armbruster, Vol. 2024, 311–47.10.1007/978-3-658-44055-8_12Search in Google Scholar

Schneider, Wolfgang Ludwig. 1991. Objektives Verstehen. Rekonstruktion Eines Paradigmas: Gadamer, Popper, Toulmin, Luhmann. Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag.Search in Google Scholar

Schneider, Wolfgang Ludwig. 1996. “Die Komplementarität von Sprechakttheorie und systemtheoretischer Kommunikationstheorie. Ein hermeneutischer Beitrag zur Methodologie von Theorievergleichen.” Zeitschrift für Soziologie 25 (4): 263–77. https://doi.org/10.1515/zfsoz-1996-0402.Search in Google Scholar

Schneider, Wolfgang Ludwig. 2021. “Social Theory.” In Soziologie: Sociology in the German-Speaking World : Special Issue Soziologische Revue 2020, edited by Betina Hollstein, Rainer Greshoff, Uwe Schimank, and Anja Weiß, 467–82. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter Oldenbourg.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Editorial: Work and Democracy in Conflict

- Focus:Work and Democracy in Conflict

- Political Spillovers of Worker Representation: With or Without Workplace Democracy?

- Workplaces as Schools of Democratic Resilience? Conceptual Considerations About the Spillover Effect

- Challenging Democratic Deficit at Work Through Humoristic Criticism: Perspectives from Turkey’s Highly Qualified Employees

- Workplace Democracy Democratized: The Case for Participative and Elected Management

- Mondragon Cooperatives and the Utopian Legacy: Economic Democracy in Global Capitalism

- Plural Cooperativism. The Material Basis of Democratic Corporate Governance

- General Part

- Between Hermeneutics and Systematicity: The Habermasian Method of Theorizing

- Discussion

- McMahan on the War Against Hamas

- A Reply to Statman’s Defense of Israel’s War in Gaza

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Editorial: Work and Democracy in Conflict

- Focus:Work and Democracy in Conflict

- Political Spillovers of Worker Representation: With or Without Workplace Democracy?

- Workplaces as Schools of Democratic Resilience? Conceptual Considerations About the Spillover Effect

- Challenging Democratic Deficit at Work Through Humoristic Criticism: Perspectives from Turkey’s Highly Qualified Employees

- Workplace Democracy Democratized: The Case for Participative and Elected Management

- Mondragon Cooperatives and the Utopian Legacy: Economic Democracy in Global Capitalism

- Plural Cooperativism. The Material Basis of Democratic Corporate Governance

- General Part

- Between Hermeneutics and Systematicity: The Habermasian Method of Theorizing

- Discussion

- McMahan on the War Against Hamas

- A Reply to Statman’s Defense of Israel’s War in Gaza