Magical Names: Tracing Religious Changes in Egyptian Magical Texts from Roman and Early Islamic Egypt

-

Raymond Korshi Dosoo

“To weave the magic of a thing, you see, one must find its true name out.”

– Ursula Le Guin, The Tombs of Atuan (1971)

1 Names in Magical Papyri

1.1 Knowing the Unknowable

“O great god… whose name is unknown… I know your name”, reads a paradoxical invocation in a second-century Demotic magical papyrus.[1] It is a common trope that names are crucial in magic – practitioners know the names of the beings they call upon, must correctly name the people whom their practices are intended to harm and help – yet they also pose significant problems for scholars. We have so many names – of gods, of angels, of real people – but what do they mean, and how much can they tell us? Does a papyrus mentioning a being named “Horus” in the eighth century tell us that the ancient Egyptian god was still worshipped hundreds of years after the triumph of Christianity and the Arab conquest?[2] Does the naming of the spirit of a dead man as Antinous mean that the writer is addressing the divinised lover of Hadrian?[3] Does the naming of an amulet’s wearer as “Mary” tell us that she was a Christian?

The purpose of this study is to explore a few of these possible questions in detail. Specifically, I hope to contribute to the ongoing dialogue about the ability of papyri, analysed statistically, to help us to trace religious change in Egypt.[4] This dialogue began with the work of Roger Bagnall in 1987, in which he suggested that onomastic data from a sample of papyri could be used to date the key moment of Christianisation – when Christians became a majority of the population of Egypt – to the fourth century.[5] Critical reflections on his approach by Ewa Wipszycka prompted several later responses to Bagnall, although he did not explicitly offer a substantially revised estimate.[6] In 2013 Mark Depauw and Willy Clarysse took up Bagnall’s basic methodology, but significantly expanded the corpus to over 50,000 papyri for which onomastic data had been gathered in Trismegistos and the Duke Database of Documentary Papyri.[7] Their work suggested a slightly later date for the Christianisation of Egypt, in the mid-fifth century – something already anticipated by Bagnall in one of the publications which followed since his original article,[8] and perhaps also by one of the responses by Wipszycka.[9] The work of Depauw and Clarysse has provoked its own critical reflections; the most significant, perhaps, is that of David Frankfurter, who has questioned what exactly “Christianisation” or “conversion” means – what degree of participation or belief is necessary to qualify an individual as Christian? – and the extent to which a personal name can measure this.[10]

In this study I will use Depauw and Clarysse’s method to examine the onomastic patterns revealed by the magical papyri dating from the second to twelfth centuries CE. While the magical papyri offer a far smaller corpus than that used in their earlier study, they are nonetheless of interest, being a completely distinct dataset, which therefore has the potential to either confirm or complicate their findings. At the same time, by looking beyond the fifth-century endpoint of previous work, this study may reveal other patterns, most notably, that of conversions to Islam. While this was not a question addressed in the work of either Bagnall or Depauw and Clarysse, it was the focus of a 1979 study by Richard Bulliet, which drew upon onomastic data from Arabic biographies;[11] Bulliet’s work study was, in fact, cited as an inspiration by Bagnall.[12] Bulliet suggested that the key moment of Islamicisation – when Muslims became the majority in Egypt – took place in the ninth century, a conclusion broadly supported by other scholars who have explored the question in the last fifty or so years.[13]

At the same time, the magical texts also contain rich evidence for what we could cautiously call belief – as performative objects, intended to effect change, they imply a belief in their efficacy, and, since they generally call upon specific deities to do so, the use of a magical text could be considered a religious act connected to specific traditions.[14] Thus the second key question of this study is that of the names of deities in magical texts – to which traditions (Greek, Egyptian, Christian, Muslim) do they belong, how do references to them change over time, and how does religious content relate to the names of the people using them? Put more bluntly – did “pagans”, Christians, and Muslims use magical texts conforming to their religious identity? The problems raised by Frankfurter and others about the difficulties of defining and imputing belief in the context of personal names all apply here, and are even more serious, but it is nonetheless a question worth exploring.[15]

I should also note that I am not the first to explore this question. Walter Shandruk presented his own analysis of the onomastic data from magical papyri in 2012.[16] This study attempts to build upon his previous work in four ways. First, the corpus I am able to present here is considerably larger than that available to him, and extends the dataset, as already noted, beyond the Arab conquest. Secondly, for this corpus I am able to offer slightly better dating, and a few small corrections, to his understanding of some of the texts, in particular those written in Coptic.[17] Thirdly, Shandruk’s study was published before that of Depauw/Clarysse, which refined Bagnall’s findings and methodology, and which I adopt here. Lastly, I offer a different method of attempting to describe the religious content of the papyri, based on the presence or absence of categories of named gods rather than a binary division into Christian/non-Christian. Shandruk’s study remains valuable, offering a different perspective and approach, whose findings this study tends to confirm.

1.2 Describing the Corpus of Magical Papyri

The texts I refer to here as the “magical papyri” belong primarily to the “long first millennium” – they appear in Greek in the first century BCE, existing alongside similar Demotic texts, although the published Demotic examples of these date to, and disappear after, the second and third centuries CE.[18] In the fourth century, they are joined by texts written in Coptic, the latest stage of the native Egyptian language. The number of Greek texts declines in the fifth century, and they disappear from Egypt by the eighth. Manuscripts in Coptic become the majority by the sixth century, and continue to be produced until around the twelfth century, at which point it seems that Arabic almost completely replaced Coptic as the language of magic in Egypt.[19]

The corpus shows clear similarities in its language, mechanisms, goals and practices to older corpora – primarily Egyptian ritual texts, but also the Akkadian āšipūtu corpus, both attested at least two thousand years earlier, and the few older Greek texts which survive on metal supports from the sixth century BCE onwards.[20] Nonetheless, the genre of Graeco-Egyptian magic seems to be somewhat distinct from these in a few ways – the most notable are the use of distinctive voces magicae and charaktēres, magical words and magical signs, both of which are attested in the corpus by the first century CE.[21] While the Demotic texts often show a closer affinity to older Egyptian material, they also show clear signs of borrowing from the Greek-language tradition, as Jacco Dieleman’s careful work has demonstrated.[22] The religious content of this early material is primarily Egyptian, Greek, and to a lesser extent, Jewish – gods such as Anubis, Helios (likely to be understood as a Greek name for the Egyptian sun god), Hekate, and Sabaoth often appear in the same manuscripts. While the fourth, and even more so, the fifth century, seem to see a shift towards a more Christian model of magic, many of the underlying practices and ritual types remain the same, with the same technical terms and magical names often being found in Graeco-Egyptian and Christian magical texts. It is fairly certain that the texts which survive on papyri from Egypt also existed elsewhere in the Roman Empire and beyond at the same time – texts on more durable supports such as metal, as well as the later mediaeval manuscript tradition, and contemporary literary texts testify to this – but how closely these would have mirrored those found in Egypt remains an open question.[23]

It has become something of a truism that magic is difficult to define. I use the term here to refer to the specific ritual and textual tradition to which the Egyptian magical papyri belong.[24] Theoretically defining the borders of this category nonetheless remains difficult, but there is generally little disagreement among papyrologists about which texts belong to it. The central texts of the category show distinctive genre characteristics – in addition to the voces magicae and charaktēres these include certain recurrent phrases (“I invoke you”, “yea, yea, quickly, quickly”) and ritual actions.[25] This formal definition overlaps with a second, functional definition – magical papyri are generally those which describe or are produced in the course of private rituals intended to protect individuals or their property (amulets), heal or cast out demons (exorcism), to harm others (curses), to divine the future, or aid the person for whom the ritual is carried out in other ways – giving them general good luck (favour), manipulating others (favour before a superior, separating a couple), and so on.[26] This second criterion is more problematic, since these goals are shared by a wide range of private (as well as public) rituals: are all divinatory or exorcistic rituals magic? Are all objects which were believed to protect the bearer – including crosses or holy water – magic? This problem, though theoretically important, is less crucial for this study, since the texts which I use here generally meet both formal and functional criteria, although I will occasionally highlight edge cases where it is more difficult to be sure that we are seeing a single (albeit broad) tradition of practice. Note that the definitions offered here – which are attempts to formalise the heuristic categories used by papyrologists – do not clearly relate to the concerns of anthropological/sociological discussions of magic which tend to dominate theoretical discussions to this day.[27] The Frazerian question of whether the texts are magical because they manipulate inanimate magical forces or threaten gods is not relevant to the discussion here,[28] and while the rituals they attest to are private, this is not necessarily an essential feature, and they are not primarily defined by their social marginality or their inversion of social values, as a Durkheimian model, of the sort best known from the work of Marcel Mauss and Henri Hubert, would suggest.[29] These concerns are latecomers to the study of ancient magic, and their influence was not felt on the field until after the corpus had been well defined.[30]

While I refer to the documents examined here as papyri, I use this in the larger sense of “papyrological documents”, which includes manuscripts written on parchment, leather, wood, and lead. I only use documents from Egypt here; a study which took in magical texts from other parts of Europe, north Africa, and west Asia would certainly be worthwhile, but the texts from Egypt offer us sources from a single geographical area with continuous attestation for a thousand years, providing a degree of resolution impossible elsewhere. I restrict my study here to Greek and Coptic texts; there are no published Demotic magical papyri from this period which include personal names, and my own failings in Arabic, and the lack of a full corpus of Arabic magical papyri, prevent me from including these sources.[31] I must also exclude carved gems for slightly different reasons; while these often clearly belong to the same broad tradition as the magical papyri, and occasionally contain personal names,[32] very few of them have provenances, or can be dated with even the loose precision of magical papyri, and so they are far less useful for a study of onomastics which focuses on diachronic change in a specific geographic area.[33] While texts written in Hebrew and Aramaic are absent from this corpus, a study of personal names in magical texts from the Cairo Genizah already exists, carried out by Gideon Bohak and Ortal-Paz Saar in 2015; many of these texts are contemporary with the latest Coptic ones considered here, and often show much overlap in practice.[34]

Within the corpus, we can define two types of manuscripts. The first is formularies or handbooks, manuscripts which provide the means to carry out rituals – invocations to be spoken, images to be copied, and/or instructions for ritual actions. These include some of the largest and best-known magical papyri which contain dozens of ritual instructions – the large codex that is the Great Magical Papyrus of Paris,[35] the five-metre-long London-Leiden Demotic Magical Papyrus[36] – but most of the surviving examples are short, containing only one or a few recipes.[37] The second type are known as applied, activated, or documentary magical papyri, or ‘finished products’; these are rituals created in the course of rituals – amulets to be worn or fixed to walls, curse tablets or love spells to be buried, and so on. It is this second category with which we will be primarily concerned with here; unlike most formularies, these contain the names of the specific individuals with whom they are concerned, and hence the onomastic data which interests us.

1.3 Named Individuals in Magical Papyri

Magical names may contain several different categories of names. In formularies, the sections to be copied or recited typically contain a “generic name marker”, which indicates where the names of specific individuals are to be copied:

ἄγε μοι τὴν

τῆς

πρὸς ἐμέ, τὸν

τῆς

Bring to me NN, daughter of NN, to my side, NN, son of NN

PGM IV ll. 1579 – 1580 (GEMF 57; KYP M3; IV CE)

This usually consists of the word translated here as NN – in Greek and Coptic deina (usually abbreviated as

, i. e. δ(ε)ῖ(να)), in Demotic and Coptic mn/nim; these are regularly followed by a second NN, indicating the name of a parent, usually the mother.[38] In Greek and Coptic these are often followed by the word koina (“usual”), probably to be understood as meaning something like “fill in as usual”.[39] In practice, relatively few of the recipes in formularies are represented in surviving applied texts;[40] this does not necessarily mean that they were never performed, but is rather an indice that the surviving record is a very small fraction of the manuscripts ever produced – perhaps something in the order of one in eighty-thousand.[41] Nonetheless, applied texts do show evidence of having been copied from similar models, containing the sequence of personal name + parent’s name, usually in the places we would expect from formularies, although in a few instances, the placement is more idiosyncratic, suggesting an emendation on the part of the copyist during the creation of the object.[42] In other cases, applied texts may copy the generic name marker, with the copyist apparently unaware that it should be replaced, or else perhaps creating it without a particular individual in mind, although in this case, a more generic phrase, such as “the one who carries this” (ὁ φορῶν), in the case of amulets, should probably have been substituted.[43]

, i. e. δ(ε)ῖ(να)), in Demotic and Coptic mn/nim; these are regularly followed by a second NN, indicating the name of a parent, usually the mother.[38] In Greek and Coptic these are often followed by the word koina (“usual”), probably to be understood as meaning something like “fill in as usual”.[39] In practice, relatively few of the recipes in formularies are represented in surviving applied texts;[40] this does not necessarily mean that they were never performed, but is rather an indice that the surviving record is a very small fraction of the manuscripts ever produced – perhaps something in the order of one in eighty-thousand.[41] Nonetheless, applied texts do show evidence of having been copied from similar models, containing the sequence of personal name + parent’s name, usually in the places we would expect from formularies, although in a few instances, the placement is more idiosyncratic, suggesting an emendation on the part of the copyist during the creation of the object.[42] In other cases, applied texts may copy the generic name marker, with the copyist apparently unaware that it should be replaced, or else perhaps creating it without a particular individual in mind, although in this case, a more generic phrase, such as “the one who carries this” (ὁ φορῶν), in the case of amulets, should probably have been substituted.[43]

The identity of the individual whose name is to be inserted varies depending on the purpose of the ritual. For amulets and healing texts, the text will contain the name of the client for whom it is created. For curses and separation spells, it will contain the name of the target(s), and less often, the client. Love spells will typically contain the names of both clients and targets. All of these will usually be accompanied by the name of the mother (matronym), less often the name of the father (patronym). A small group of curses in Greek dating to the second to fourth centuries contain the names of the dead individual with whom they are buried, and whom they therefore call upon to enact the curse. These cases seem to be idiosyncratic, with at least one providing clear evidence that the copyist inserted a personal name where the exemplar from which the text was copied read “O corpse-demon, whoever you may be”.[44] Christopher Faraone has suggested that this practice of naming the dead spirits, a feature of the pan-Mediterranean binding curse tradition found only in Egypt, may draw upon the older Pharaonic practice of writing letters to dead relatives.[45] Since these names are so rare, I will not consider them in the study here.

The names of deities or other culturally significant figures which appear in texts are treated somewhat differently in them. There are only a few cases where we find phrases comparable to “NN god”, in which the copyist is to insert a deity of their choice; more often the texts seem to be composed with specific deities in mind, and to be intended to be copied without being changed, although there is some evidence that copyists might deliberately change the beings invoked, or, more often, simply change the names of less common deities by miscopying.[46] These deities may appear in the texts in several roles. They may be invoked, that is, called upon to fulfill the request contained in the formula. They may be invoked by, that is, used as an authority by which a different invoked being is commanded to obey. They may be otherwise mentioned in an argument or historiola – that is, they may be mentioned as part of a narrative passage or epithet without being directly invoked, or their name may simply appear as part of a sequence of names which are apparently intended to increase the formula’s power.[47] Finally, they may be mentioned as hostile beings against whom the invoked being or other agent is to act – a demon causing disease or possession, for example. In this study, my analysis will not, for the most part, consider the role of the deity in the text – rather, I will simply look for mentions of them, since a mention, regardless of their role, does perhaps indicate that the copyist had access to them, and hence perhaps the cosmology they were part of. Finally, it is worth noting a problem with identifying divine names. Magical papyri often contain many voces magicae, the majority of which are apparently unique; even those which seem to be variants of a single name may show significant divergences from one another. It is not even clear if voces magicae are always names; certain texts imply that these were sometimes instead understood to be phrases in a divine language, which contained other classes of words alongside proper nouns.[48] In practice, my analysis here will only take into account the commonly recurring voces, such as Akramakhamari, which usually, though not always, seem to have been understood as names, and whose variants are relatively easy to recognise.[49]

We may briefly note a final way in which individuals appear in magical papyri – as the authors of texts, or as the sources of particular variants of texts (credited in marginalia or integrated notes). These figures – deities such as Hermes-Thoth, or legendary sages, such as Solomon, Orpheus, and Democritus – do not generally appear in the amulets which concern us here, in which the texts are never credited to a particular author.[50]

1.4 Shandruk’s “Christian Use of Magic in Late Antique Egypt”

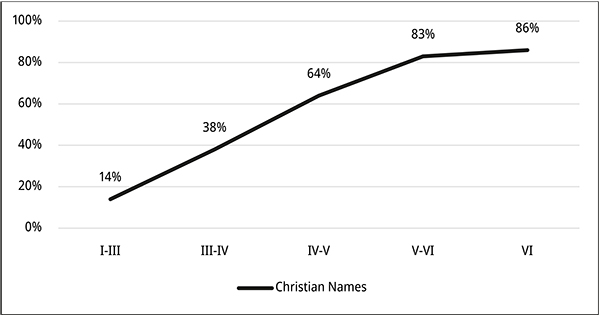

As noted above, Walter Shandruk performed a similar analysis in 2012, looking at 70 applied magical texts in Greek and Coptic dating from the first to the sixth centuries CE.[51] Using the criteria of Bagnall’s original article, he identified 28 of the clients as Christian, and found that Christians likely crossed the threshold into being a majority (64 %) by the fourth to fifth century, becoming a significant majority (83 %) by the fifth to sixth.[52] Interestingly, these findings agree more closely with the later study of Depauw and Clarysse than that of Bagnall (whose methodology Shandruk used), with its smaller corpus.

Fig. 1: Estimate of percentage of Christians in applied magical texts after Shandruk (2012) 46; a 1.5 multiplier has been applied to the raw percentages to account for Christians who cannot be identified by their names.

In the second part of his study, he then classified the magical texts as Christian or non-Christian. Christian papyri were defined as those containing Old and New Testament figures, citations of the New Testament or Christian apocrypha, Christian doctrinal or liturgical statements, or Christian symbols.[53] Shandruk concluded his analysis by finding that Christians did not display a different use of magical texts from non-Christians: prior to the fourth-fifth century religious transition, they were attested as using both Christian and non-Christian magic. The major change was rather a temporal one, as Christian magical papyri appeared in the fourth century, and then became predominant after the fifth century, changing both the content and the types of texts, with amuletic (protective and healing) texts being more common than aggressive (curse and erotic) texts after Egypt became predominantly Christian.

As Shandruk notes, the interest of this study lies not only in its approach to onomastics, but also in its clarification of the relationship between Christians and the use of magic. As is well known, the Christian traditions were, very nearly from the beginning, consistently opposed to the practice of magic by their adherents.[54] From the Pauline letters (e. g., Galatians 5.19 – 21) to the Didache to later canons, Christians are forbidden to practice magic, an injunction repeated and elaborated upon in numerous theological texts and sermons, inherited in part from contemporary Graeco-Roman norms, and in part from injunctions in the Torah against practices translated into the Greek Septuagint using terms such as mageia, pharmakeia and their cognates.[55] At the same time, there are, of course, numerous outsider sources by authors, such as the second-century philosopher Celsus, which accuse Christians of practicing magic, and the accusation was well enough known to Christians that governors in Christian hagiographies repeatedly (albeit wrongly) accuse saints of being magicians.[56] Yet even insider Christian sources confirm that some Christians did practice magic – the canons themselves provide evidence that Christians, including clerics, needed to be forbidden from doing so, and we find very similar sermons complaining of magical practices, such as the recourse to amulets, by Christian flocks from authors across the Roman world in the fourth to sixth centuries – from Ephraim in Syria and Shenoute in Egypt to John Chrysostom in Constantinople and Caesarius of Arles in Gaul.[57] Their definition of magic is perhaps slightly different from ours – amulets containing Biblical texts are explicitly contrasted with forbidden amulets by authors such as Augustine and Chrysostom – but it is clear that their definition would have included many of the more “central” instances of magical texts – those with voces magicae and invocations taking non-canonical forms, and those intended to heal as well as curses and love spells.[58] Shandruk’s study of names in magical papyri would thus seem to confirm this picture, including the fact that Christians were indeed using the same magical practices as their non-Christians neighbours in the early centuries CE.

At the same time, Shandruk’s study raises some of the more general problems of the subjects he approaches – identifying Christians based on their names, and distinguishing Christian and “non-Christian” material objects. As Frankfurter, and others, such as Wipszycka and Malcolm Choat before him have stressed, names are usually given by parents rather than chosen by children, so that while, en masse, changing onomastic patterns might attest to patterns of conversion, it is more difficult to use individual names to discern the religious identities of those with those names.[59] This goes not only for individuals identified as Christians using Bagnall’s methods, but also for those not identifiable as such based on their names, many of whom would likely have been Christians, especially in the later fourth and fifth centuries. This is a serious problem, and one I will discuss at greater length below.

The second problem is that of identifying texts as Christian or non-Christian. While Shandruk’s approach is a rich one, taking into account features of both content and materiality, I find the binary classification somewhat misleading. For example, the sixth-century SM 19 has no scribal marks such as the cross, or names of Christian figures, and thus no explicitly Christian features; it is thus a “non-Christian” text by his definition. But it dates to the sixth century, a period that we would expect to be almost entirely Christian in context, and apart from unique voces magicae, the only recognisable named deities are Damnameneus and Akramakhamari, neither of whom belong to contemporary or near-contemporary Greek or Egyptian cults. Of the two, only Damnameneus has a clear origin, as one of the members of the Idaean dactyls, but the frequent appearance of his name alone in such amulets suggests that the name was rather transmitted through and borrowed from the well-known apotropaic sequence known as the Ephesia Grammata, the “Ephesian letters”.[60] Akhramakhamari is known only from magical texts and Christian “gnostic” texts;[61] both he and Damnameneus are found both in pre-fourth century Greek magical and in Coptic magical texts as late as the eighth century.[62] Later the text invokes “the one who sits over the cherubim and seraphim” – a clear reference to the Jewish-Christian god, originating in the Bible, and taken up in liturgical texts.[63] While references to gods sitting over the cherubim are present in older Graeco-Egyptian magical texts, they are also found, and indeed more common, in later Christian magical texts.[64] Far from being clearly “non-Christian”, then, the text has features found in both pre- and post-fifth century, Christian Egypt. Even more striking is the case of SM 10, a third or fourth century amulet for a woman whose mother’s name, Sara, suggests she may have been a Christian; it contains an image of an ouroboros and mention of the common voces Semesilam, Albanathanalba, Akhramakhamari, and Sesengen Barpharanges, and Phre (Egyptian pꜣ rꜥ, “the sun (god)”), but seems to primarily invoke the Jewish god, named as Adonai Eloai Sabaoth, and his angels Ouriel, Michael, Gabriel, Souriel, and Raphael. My impression is that this amulet would have been understood as entirely acceptable by many Christians, who would have seen its voces magicae as simply secret names for God and his angels, yet, according to Shandruk’s criteria, it is once again non-Christian.[65]

Measuring the religious belonging of a text in a way which can be incorporated into a statistical analysis is therefore not an easy or uncontroversial proposition. In this study I will attempt to do so by focusing on the frequency of particular names over time, such as Damnameneus or cherubim. This has the disadvantage, compared to Shandruk’s approach, of neglecting scribal features such as the use of crosses, but these latter are perhaps better understood, in at least some cases, as indices of the training of the scribe than the religious identity or content of the text – a later eighth century narrative charm centring around a story about of Horus and Isis begins with two crosses, and adds two more at the end of the recto and of the text.[66] The crosses indicate that this manuscript was certainly produced by a copyist trained in a Christian environment, but the contents are not straightforwardly describable as Christian. Focusing on names, though imperfect as an approach, nonetheless allows a more nuanced classification of texts – rather than imposing a Christian/non-Christian binary, it is able to consider all the different names present in particular manuscripts, and understand texts as potentially drawing simultaneously upon multiple religious traditions, of which Christianity may be one.

1.5 Known Copyists, Owners, and Users of Magical Papyri

Before examining the names in applied magical texts en masse, it is worth briefly reviewing named individuals who copied, owned, and used surviving magical papyri, about whom archaeological context or other information allows us to say a little more, in order to provide a richer picture of who these people might have been. I exclude here individuals known from literary texts, such those named in Zacharias of Mytilene’s Life of Severos of Antioch,[67] and authors such as Galen and other medical writers, who reproduce or describe magical recipes which they owned or had encountered.[68]

The earliest individual known to me is Aurēlius Philammōn, whose notebook survives in the form of an idiosyncratic codex dating to the years 357 – 359.[69] Philammōn was responsible for the collection of the tax known as the annonia militaris in the area of Hermopolis, and though most of the texts in his notebook relate to this practice, others consist of trial reports – perhaps for the study of law, or to read for entertainment, in the fashion of modern detective or court dramas[70] – and nearly twenty magical texts. The most recent editors suggest that he may have been collecting these as evidence for a trial in which their original owners would be charged with magic,[71] but there is no clear reason to think this from the way the texts are copied – they are laid out like other magical recipes, and have no annotations or comments highlighting features of legal interest. It is likewise not clear why he would have copied them in full for this purpose rather than simply making brief notes or confiscating the originals; the possession of magical texts itself was a crime according to contemporary Roman law, so by including them in his own notebook in the context of a legal persecution of magic, Philammōn could have been running a risk himself.[72] It seems more likely, as Christopher Faraone has suggested, that he intended to use the texts for his own purposes.[73] They consist of a fairly typical range of interests – a victory charm, a silencing curse, a love spell, a favour charm, and several healing procedures using Homeric verses. Two of the healing charms are specifically for healing female complaints –breasts or uterine pain, and uterine bleeding, and Faraone notes that these may have been intended to help the women of his household.[74] In terms of their content, it is difficult to classify these texts as “pagan” or “Christian”; there are several typical voces magicae, but few names which can be associated with any cults. On one page we find Iaō, Abrasax, and perhaps Albanathanalba,[75] but these names are too ubiquitous in Graeco-Egyptian, as well as Christian magic, to interpret in the absence of other indicators. There is an unmistakeably Egyptian god, the solar scarab deity Khepri, in the Hellenised form Khphuris, but its context – in a short sequence of voces magicae including Lailam and Semesilam – makes it difficult to see a deep connection to Egyptian theology.[76] The editors note that “Apollo” features in one text, but this is in a Homeric citation, and thus not particularly telling;[77] the Homeric epics continued to be read (and used for magic) by Christians into the Middle Ages and beyond.[78] The favour spell does contain an invocation to Helios, but the format – a chairetismos consisting of a series of acclamations beginning “hail” (khaire) is very familiar from later Christian texts, and the sun (hēlios) continued to play an important role in Christianity, as a personified celestial body who was part of God’s creation, rather than a deity.[79] While the text later refers to the almighty (pantokratōr) it is not clear that this title is applied to the sun, and it later contains several typically Jewish-Christian names – Iaō, Sabaōth, and Mikhaēl. Once again, this text would not be out of place in a later handbook written in either Greek or Coptic. I thus agree with the authors that it is unclear if the codex should be classified as “pagan” or “Christian”, and it tends rather to suggest that such a classification would not necessarily meaningful.[80] Philammōn’s name likewise gives no clear idea of his religious affiliation. The original Philammōn was a semi-divine musician of the heroic age, whose name many have been interpreted in the Roman period as a theophoric name containing the name of the god Amun in its hellenised form Ammōn,[81] but our Philammōn might have been named after an older family member of the same name rather than the hero or god. His father’s name, Hermes, is likewise theophoric. There are thus no onomastic grounds for thinking Philammōn was Christian, but neither would it have been unlikely; he served as an imperial functionary in an Egypt ruled by a Christian emperor, Constantius II, and living as a Christian might have been advantageous for his career, regardless of his personal beliefs. The work of Depauw and Clarysse would tend to suggest that just under half of the inhabitants of Egypt were Christian at the time the codex was copied;[82] there is thus a strong chance that Philammōn was Christian, even though he used magical texts which were not explicitly Christian, but the chance is not so strong as to be a certainty.

The next named magic users are inhabitants of the town of Kellis, in the Dakhla Oasis, 350 kilometres west of the Nile Valley. They were residents of Area A House 4, living among at least two extended families consisting of at least 36 individuals, attested in the late fourth century.[83] These inhabitants were highly literate, and when they abandoned their house in the 390s, left behind part of a large archive of material written in Greek, Coptic, and Syriac.[84] Among these manuscripts are several magical texts, both formularies and applied texts. One handbook contains a list of healing procedures, which incorporate various voces magicae, two of which may perhaps be identified as the names of the Egyptian deities Ptah and Renenutet.[85] One of the recipes has been recopied as an amulet for Pamour son of Lo, a family member known from other texts.[86] Two other damaged amulets have been found in the house, one for Pamour[87] – either the son of Lo, or a different individual with the same name (rather common in Kellis)[88] – and another for a woman probably called Elake, a name and individual otherwise unknown.[89] Finally, there is a spell to separate a couple, copied as part of a letter by a man named Valens to another named Pshai, the latter known to have been a member of the household, on Pshai’s request; he likely intended to use it himself.[90] This text is more clearly Jewish or Christian, calling upon the Jewish god and referring to several of his Biblical deeds. The individuals who used these texts do not seem to have worked primarily as magicians, or any other type of ritual practitioner; rather they appear to have been literate artisans and traders, primarily concerned with the production and sale of textiles.[91] As in the case of Philammōn, these were texts which they may have simply wanted to use themselves, either for personal or familial gain, or as a side practice. What is most interesting about these individuals, however, is that we know from their correspondence, and other documents, that they were practicing Manichaeans. Again, magical practice and religious identity does not neatly align; the healing recipes are typical of older Graeco-Egyptian magic, and although the separation spell could be seen as Christian – and Manichaeans in the Roman Empire seem to have at least partially identified as Christian[92] – it is not clearly the product of a specifically Manichaean community. The names of the household likewise leave their religious identity almost invisible. Of the 36 individuals apparently belonging to the household, only 6 (16.7 %) have recognisably Christian names, such as Iōhannes (John), or Makarios.[93] Interestingly, all but one of these belong to closely-related members of one of the families – the other family, to which Pamour and Pshai both belonged, have one member with a Christian name (Andreas) in the youngest attested generation, with most members instead using the recurrent family names of which Pamour and Pshai are two examples, and of which at least the latter originated in the local native Egyptian cults.[94] The two families, despite both apparently being Manichaean and exactly contemporary, show very different onomastic practices: the religious affiliation of Pamour’s family are onomastically invisible, while those of Iōhannes’ family are immediately obvious, albeit pointing to a generically Christian, rather than specifically Manichaean, identity.

From the late fifth century is the archive of Phoibammōn of Naqlun, a hermit who lived in a hermitage just over a kilometre from the Monastery of the Archangel Gabriel.[95] Among his papers, in Greek and Coptic, are three magical texts, only one of which has been published – an applied curse against a man named Biktōr (i. e., Victor).[96] The text invokes various angels, including Atrakh and Moutrakh, described as being the great angels on the right and left of the sun. Although it does not mention orthodox Christian figures, the centrality of angels is suggestive of the Christian context to which it certainly belongs. A second text contains an image of an animal-headed figure, reminiscent of donkey-headed figures of Seth-Typhon sometimes found in separation spells and curses; the triangular form of the manuscript is perhaps suggestive of the former, since there is at least one other Coptic separation spell in the form of a triangle, perhaps intended to evoke the form of a knife which might “cut” a relationship.[97] The last text is a series of recipes in Greek and Coptic for healing various conditions and for reconciling a man with his unfaithful wife.[98] These are all written in different hands, and so while it is not certain that Phoibammōn himself, and/or his disciple(s), used them, it is quite possible that they did. Phoibammōn would thus be a clear example of a Christian religious professional, specifically a monk, who did practice magic – something attested by Church canons, and often assumed to be the norm for magical practitioners in Christian Egypt by modern scholars.[99] As an anchorite, we would expect Phoibammōn to be a devoted Christian, even if, at this remove of time, we cannot be certain about the exact content of his beliefs. Again, though, his name would not reveal this – it is a theophoric name referring to the syncretised solar deities Phoebus and Amun.[100] In his case, however, it is almost certain that he is named after one of the two martyr saints of this name, who were widely venerated in Egypt from the fifth or sixth century onwards.[101] This increasing prominence of saint names of pagan origin from the fifth century onwards is something we must be aware of, a feature not taken into account in the model of Depauw/Clarysse, which focused on the fourth to fifth centuries.[102]

The next figure is Dioskoros of Aphrodito, the estate manager, lawyer, notary, and poet of sixth-century Aphrodito whose huge archives, in Greek and Coptic, provide us with significant information about his family and home region.[103] Despite his name, referring to the divine twins the Dioskoroi, we know he was a Christian;[104] his father, Apollos, likewise lacks a name which we can conclusively label as Christian. It is nonetheless likely that they do have Christian namesakes – Apollos named after the figure of the same name from the book of Acts (18.24 – 27),[105] Dioskoros after the Patriarch of Alexandria whose episcopacy lasted from 444 – 458.[106] Among Dioskoros’ archive is a brief prayer to God for protection from demons, whose style and contents are very close to other magical texts, invoking the Lord Almighty, Iaō Sabaō Brinthaō.[107] Though not necessarily orthodox in its formulation, it is clearly Christian. It is unclear if Dioskoros composed it himself, drawing inspiration from amulets he had seen, or copied it from a pre-existing source, and whether he intended to use it, or had copied it only for its interesting style and vocabulary. It is worth noting that Dioskoros, like the patriarch who was his namesake, was likely a member of the majority Miaphysite (later “Coptic”) branch of the church in Egypt, considered a heretical offshoot by the Chalcedonian Church which enjoyed imperial support.[108] The subtle, albeit deeply meaningful, theological differences which divided these groups are likewise not apparent in this text.

The final two individuals to be mentioned here are the copyists of substantial Coptic magical texts dating to the tenth and eleventh centuries, Iōhannes and Raphaē, who each identify themselves as deacons in texts dating to 967 and 1035 respectively.[109] Little else is known of them; Iōhannes calls himself a “servant of Michael” – probably indicating that he belonged to an institution dedicated to the archangel apparently located in the otherwise unknown site of Pcellēt, almost certainly in the Faiyum.[110] In contrast to the earlier individuals we have considered, Iōhannes and Raphaē have clearly Christian names (forms of John and Raphael), and their belonging to the Church is confirmed by their profession of deacon. The texts they copied are clearly Christian in inspiration; Iōhannes copies several invocations and prayers addressed to, and often said to be composed by, Christian superhuman figures, including the Trinity and saints.[111] Raphaē copies a list of procedures to be used in conjunction with the Psalms, a type of magic common in the later Christian and Jewish communities of the Near East and Europe.[112] At the same time, it is unclear what their relationship with the texts was – were they copied for their own use, or, like most surviving manuscripts with colophons, for patrons who paid for the reproduction of texts to be dedicated in the library of a religious institution?[113]

This overview has further emphasised some of the problems already raised when reviewing Shandruk’s work – most of the individuals discussed here were Christians, but few would have been identified as such based on their names alone. The texts they use are likewise often difficult to clearly characterise as “pagan”, “Christian”, or “non-Christian”, although most include Jewish-Christian figures, as well as those known exclusively from the magical tradition, and, in the case of the Kellis texts, a few Graeco-Egyptian deities. This would tend to confirm the impression that it was the types of texts available to users which changed over time, with Christians driving this change, but nonetheless using those texts available in their time and place regardless of their religious elements.

2 Personal Names in Magical Papyri

2.1 Overview of Corpus

It is now time to examine the names found in magical texts from Egypt. The Kyprianos Database of Ancient Ritual Texts and Objects was created by the project Coptic Magical Papyri: Vernacular Religion in Late Roman and Early Islamic Egypt in 2018, and as of the first of January 2022, it contained 162 applied magical manuscripts from Egypt written in Greek (97 manuscripts) and/or Coptic (67 manuscripts),[114] dating to between the second and twelfth centuries CE and containing personal names. This is the largest existing corpus of magical texts in these languages, including all the examples from the major published corpora, as well as numerous examples published individually, and several manuscripts which remain unpublished at present, but whose contents are well enough known to me to have allowed the extraction of the relevant data. There are no published applied magical texts in Demotic or Hieratic containing personal names from this period known to me,[115] and while it might have been desirable to include Arabic texts, these have not yet been systematically added to Kyprianos, and in any case, would likely be less useful for the purposes of determining religious change for reasons discussed in detail below (2.3). As noted above, these ‘applied texts’ are those created in the course of a specific ritual, as opposed to handbooks (or formularies) which contain instructions for carrying out rituals.

Note that some texts had to be excluded from the analysis. These include those which are duplicates – produced for a single client, often by a single scribe, and containing identical or near identical texts; these are understood here as single datapoints spread across two or more manuscripts.[116]

Analysis of ritual purposes in the corpus of applied magical texts containing personal names in Greek and Coptic dating from the second to twelfth centuries CE.

Superordinate Category | Subordinate Category | Number of Texts |

Amuletic | Healing/Protection | 88 |

Favour | 4 | |

Total Amuletic | 92 | |

Aggressive | Curse | 35 |

Love | 27 | |

Separation | 7 | |

Total Aggressive | 69 | |

Divination | 1 | |

Total | 162 | |

The purposes of most of these manuscripts may be divided into two overarching categories – amuletic and aggressive – each further subdivided into more precise types. One manuscript did not fit into either of these categories – this is SM 66 (KYP M889; TM 92331; III–IV CE), a bowl inscribed with an invocation for a spirit to enter an individual named Alexandros in a divination ritual. While divination rituals of this type are common in the Graeco-Egyptian magical corpus, they do not generally require the creation of a written text which specifies their purpose – more common are amulets to protect the practitioner during the performance of rituals[117] – and so this would appear to be the only surviving example of an applied divinatory text.

Amuletic texts include those intended to protect or heal the user from diseases, demons, the evil eye, harmful magic, and so on as well as those intended to bring favour – that is, general good luck, charisma, success, or favour before a superior. Aggressive texts are in turn subdivided into three categories: curses, intended to harm or incapacitate an enemy; love spells, intended to make the target fall in love with and/or submit to the sexual desires of the user; and separation spells, intended to separate a couple, or cause strife between friends or family members.

Before discussing the basic diachronic tendencies of the corpus, it is worth highlighting one of its features that makes it more problematic to use for onomastic analysis than documentary texts, that of dating. Magical formularies rarely, and applied texts never, specify the date of their production, and applied texts are very rarely written as palimpsests upon documentary texts which might contain this information – as objects intended to be imbued with power, it seems that scribes usually preferred to use fresh supports.[118] This means that the entire corpus may only be dated palaeographically, usually within 1 – 2 centuries for Greek texts; with Coptic texts, the dating may be even less precise, with editors at times only suggesting manuscripts are “early”, for example, or even declining to propose dates. The Coptic Magical Papyri project has managed to improve upon the dating of many of the manuscripts studied here, but the problem still remains – we are dealing with a picture of religious change with a resolution of one to two centuries. By contrast, modern demographers prefer to use five-year blocks.[119] However, the names contained by the manuscripts are only used as dating criteria in exceptionally rare cases,[120] and so we should not expect the results to reflect pre-existing assumptions about the distribution of names; rather, if the datings are incorrect, we would expect randomness.

Fig. 2: Number of applied magical manuscripts containing personal names per century in Greek and Coptic.

While the manuscripts date to between the second and twelfth centuries CE, their distribution over time is not consistent. Greek manuscripts are attested in significant numbers from the second until the sixth century, at which point their numbers decline significantly, and almost completely disappear by the eighth. This is more or less what we would expect – the Arab conquest in 642 separated Egypt from the Greek-speaking Eastern Roman Empire, and established Arabic as a competing elite language, whose use in the administration was introduced and gradually enforced over the course of the eighth century. Coptic texts appear in the fourth century,[121] and co-exist alongside Greek ones, overtaking them in the seventh century before declining over the eleventh and twelfth centuries as the population becomes increasingly Islamicised – with Christians converting to Islam – and Arabised – with even those who remained Christian increasingly speaking and writing in Arabic.[122] We may note that this pattern is slightly different than that found in magical texts as a whole – previous analyses which included formularies have found Coptic overtaking Greek in the sixth century;[123] it is likely the case that Greek applied texts – generally shorter than the recipes contained in formularies, and susceptible to mechanical copying rather than requiring advanced reading skills – might have continued to be produced for longer in Egypt than Greek formularies.

Fig. 3: Change in content of surviving applied manuscripts in Greek and Coptic over time (percentages).

If we look at the temporal distribution of amuletic and aggressive texts, we can clearly see the pattern already noted by Shandruk – the decline of aggressive practices over time.[124] While aggressive applied texts dominate the second and third centuries, by the fourth they are in steady decline, and by the fifth they have been relegated to about 20 % of the corpus, remaining at approximately this level until their disappearance in the twelfth century. As Shandruk suggests, we might see here a shift brought about by the Christianisation of Egypt – a move away from the aggressive techniques which would be harder to justify within a Christian worldview.

Fig. 4: Change in content of surviving applied manuscripts in Greek and Coptic over time.

The patterns are slightly different, though, when we distinguish the different kinds of aggressive practices. Amuletic texts remain the most common for all periods, except for the second century, when they are outnumbered by love spells. The use of amuletic texts would seem to follow the overall pattern of the attestation of the corpus – peaking in the fifth century and then declining, with a smaller peak in the tenth. Love spells are quite well attested in the second through fourth centuries, then decline considerably; there is only one published applied Coptic love spell.[125] Separation spells, though less common, show a rather different pattern – they are best attested in Coptic manuscripts of the sixth and seventh, and then tenth centuries. Curses are fairly well attested from the fourth century onwards, with a noticeable decline in the sixth century, and then a small peak in the tenth, following the general trends of the corpus. These tendencies seem more difficult to explain by reference to Christianisation – why do curses peak in the fifth century, and why do separation spells only appear in significant numbers after Christianisation? There are a number of possible answers; many of the fifth century curses seem closer to Henk Versnel’s category of prayers for justice than the earlier Greek binding curses, and are highly Christian in their worldview; there may have been a brief window in which Egyptian Christians decided that these represented legitimate, and non-magical practices.[126] It may also be that separating the object of your affection from an existing partner was seen as safer than trying to attract them directly under Christian hegemony, and the stricter laws of the post-Diocletianic Roman order.[127] Separation spells, like curses, typically contain only the names of the targets, in contrast to love spells, which also contain the name of the client for whom they are made, rendering the finding of one of these objects potentially dangerous for the commissioner. At the same time, it is worth noting that formularies from the post-fifth century Christian period – overwhelmingly in Coptic – provide ample evidence for ongoing interest in aggressive magic.[128] It is possible that these generated traces which are invisible in the archaeological record: while some prescribe creating texts to be buried, this is often at the victim’s house rather than in a grave, and, since most of the archaeological work in Egypt focuses on tomb and temple sites, these would be less likely to be found. Indeed, the object to be deposed at the victim’s house is often not a text at all, but rather a liquid or other substance over which a formula has been spoken.[129] The shift may therefore be less one of the type of practice than of the nature of practice – from graveyards to domestic deposition sites, and from written texts to empowered unwritten objects.

In terms of geographical origin, the distribution follows the tendencies of manuscripts from first millennium Egypt more generally; the majority have no precise provenance recorded, while large numbers come from Oxyrhynchus (or Middle Egypt more broadly), which saw considerable excavation in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, with smaller but still significant numbers from the Faiyum and the Theban region, likewise areas with large ancient settlements in marginal locations which were heavily exploited by archaeologists and treasure hunters over the last two centuries. Smaller numbers come from other locations in Egypt, with only one, a metal curse tablet found in Alexandria, from Egypt north of Cairo.

Applied magical texts in Coptic and Greek by provenance (where known).

Origin | No. of texts |

Middle Egypt (inc. Oxyrhynchus) | 25 |

Faiyum | 14 |

Theban Region (inc. “Upper Egypt”) | 11 |

Hermopolis/Antinoopolis | 6 |

Achmim (Panopolis)/Atripe | 5 |

Heracleopolite Nome | 3 |

Memphis /Cairo/Saqqara | 3 |

Kellis | 3 |

Asyut (Lycopolis) | 2 |

Alexandria | 1 |

2.2 Personal Names and Methodology

The names of human (as opposed to superhuman) individuals contained in these texts have been divided into four categories – clients and targets, and parents of clients and parents of targets. The basic results are as follows: 371 named individuals were identified in the corpus, of whom 139 were clients, 93 targets, 87 the parents of clients, 50 the parents of targets, and 2 the grandmothers of clients. Since some individuals had multiple names, the number of names was higher than the number of individuals, and as a result there were 378 name tokens (that is, instances of names). However, since names are often recurrent, this could be reduced to 268 unique name types, of which 136 were female, 120 male, 1 either male or female, and 11 of uncertain gender. This discrepancy in gender is largely due to the gender of parents – because most named parents are mothers, the corpus contains 162 males, and 200 females. Yet, if we examine the data statistically, removing this bias, we can see that male names are slightly more diverse than female names – a random sample of 100 men would have 74.7 different names, whereas 100 women would have only 68.5 names; we will see that in certain subgroups the divergence is greater still.

In terms of gender balance more broadly, 98 clients were male, and 44 female, while of client parents, 6 were male, and at least 81 female.[130] Of targets, 56 were male, 37 female, and one of undetermined gender, while of target parents, 3 were male, and at least 43 female.[131] There are a few initial comments to make here. First, men are better represented among both clients and targets than women, and this generally follows the trend in ancient written sources, in which women tend to be mentioned in smaller numbers than men. However, the scale of this imbalance is far less marked than in many other textual genres;[132] women are relatively well represented in magic. The high representation of men as clients might seem surprising, since literary texts and depictions in mummy portraits tend to associate the wearing of amulets with women and children rather than adult men, and the type of text in which most clients are named is indeed amulets.[133] On the one hand, this is likely an indicator that the literary picture is (at least in part) describing a masculine ideal rather than the reality, but this may also suggest that many amulets were commissioned by parents for male children – there are some examples for which this is almost certainly the case[134] – so that their predominance may be a sign of a culture which tended to value male children more than female ones.[135] The higher representation of women among the targets of aggressive texts is in part due to the fact that most (though not all) surviving love spells are produced by men targeting women,[136] and in part due to the fact that women feature fairly regularly as the victims of curses by both men and women, pointing to their prominence in roles – public or private – in which they came into conflict with people who might be moved to attack them. It is worth noting that some texts contain many names; this is principally the case in separation spells (which always name at least two victims to be separated) and curses (which may contain long lists of enemies), although occasionally amulets intended to protect households may list every member of the family.[137]

The fact that most individuals in magical texts are identified by their mother’s, rather than their father’s, name (i. e., a matronym rather than a patronym) is well known, and has been traced to the Pharaonic magical tradition, from which it spread to the international Graeco-Egyptian magical practice in the Roman period.[138] Of the 130 individuals identified by a parental name whose gender may be identified with certainty, 121 (93.1 %) are identified by a matronym, and only 9 (6.9 %) by a patronym: matronyms are overwhelmingly more common. Patronyms are used for 6 of 89 men (6.7 %) and 3 of 41 women (7.3 %), suggesting that the gender of the client was not a particularly relevant consideration when deciding between matronym and patronym.[139] It is difficult to see any patterns in the few cases that use patronyms – they are a mixture of aggressive and amuletic texts, intended for both men and women, and occur in both early (second to third century) and very late (twelfth century) texts. In two cases, they are amulets whose contents are closer to orthodox Christian prayers than typical magical texts, perhaps suggesting that their atypicality in the use of a patronym may relate to their atypicality in terms of content.[140] One love spell for a man targeting another man uses patronyms for both, which might suggest a deliberate decision to avoid women’s names in a same-sex erotic context.[141] In a final case, one of the relatively rare examples of a woman using a love spell against a man, she is identified by a patronym; we might imagine that in using it she is being masculinised, to fit with the more masculine role of a love spell commissioner.[142] These suggestions are highly speculative, however, and, in particular in the case of the last example, I suspect we are simply dealing with an outlier. It is worth noting that there is a slight difference here between Christian and Jewish magic – the study by Bohak and Saar found that in the magical texts of the Cairo Genizah, matronyms were more common than patronyms, but to a lesser degree – matronyms were found in 72 % of texts where parental names are given, and patronyms in 40.7 % – and so fathers are mentioned far more often than in the corpus considered here.[143]

While this analysis of gender dynamics has revealed some interesting patterns, we are more concerned here with “imputed religious affiliation”, and more specifically, whether we can impute a likely Christian or Muslim identity to an individual based on the consideration of their own name and the name(s) of their parents. For our purposes here, we will consider an individual to be likely to be a Christian if either their own name, their parent’s name, or both, are identifiably Christian. Here I follow the methodology of Depauw and Clarysse, who refined that of Bagnall. Note that in both of these earlier studies, the names of fathers were generally the only names available for parents, since mothers are rarely mentioned in documentary texts.

The basic categories of names considered as Christian are:

Old and New Testament Names[144]

Names of figures from the Christian canonical books. Excluded, however, are the names Apollos and Stephanos, who despite being those of characters from the New Testament, were common pre-Christian names, derived from the god Apollo and the word for “crown” respectively. Note that Old Testament names could also have been borne by Jews, but Bagnall, Depauw, and Clarysse consider their numbers to have been too few in Egypt to make a statistical difference following the revolts of 115 – 117.[145]

Abstract Names[148]

Names derived from key Christian concepts, such as Anastasios (from anastasis, “resurrection”) and Epiphanios (from epiphaneia, “epiphany”).

Excluded from Bagnall’s original list are:

Names of Christian Emperors[149]

These are analysed by Depauw and Clarysse as representing dynastic loyalty rather than religious affiliation on the part of parents who choose these names.

Martyr and Saint Names[150]

These names are generally not explicitly Christian in origin – many of the most popular, such as Phoibammōn and Anoup, are theophoric names referring to Egyptian or Greek deities – and only became popular after the fifth century onwards, as Christianity became more established; for this reason, they are not particularly useful for imputing religious identity during the third and fourth centuries, when the process of conversion probably began to take place. This exclusion, necessary in a study which reproduces the work of Depauw and Clarysse, poses problems when discussing periods after the fifth century, as will be discussed in more detail below.

Certain other miscellaneous names[151]

To this, I have added the category of names which can be identified with some certainty as Arabic in origin, referred to subsequently as Arab names. There may be a few more which are too ambiguous for certain identification.[152] A thorough study of Arabic-origin names in Coptic is a vital desideratum, since the subject is considerably understudied.[153] Such names begin to appear in Coptic papyri already in the seventh century, shortly after the Arab Conquest, but their presence likely indicates several overlapping factors.[154] The first is the presence of individuals of recent Arab origin, in most cases likely Muslim, but potentially also Christian; individuals with Christian names found in Egyptian documentation may be recent Christian Arab immigrants, who might be onomastically indistinguishable from ‘native’ Egyptian Christians.[155] The second possibility is that of Egyptian converts to Islam, who would adopt an Arabic personal name (ism) which might, in practice, be used alongside their older ‘Christian’ (i. e., Graeco-Coptic) name.[156] These individuals seem to often continue to use Coptic in, for example, letters, since it might remain the mother tongue of their families for a few generations. The third phenomenon is that of the Arabisation of Egyptian Christians, who increasingly began to adopt Arabic-origin names without converting to Islam. The fourth is that of non-Christian, non-Muslim inhabitants of Egypt, including Jews, who also used Arabic names, often in conjunction with, for example, Hebrew names.[157] Disentangling these different factors is extremely difficult. Maghed Mikhail suggests that onomastic Arabisation began in the ninth, and became more common in the tenth century.[158] In two thirteenth century Coptic marriage contracts we have cases of deacons and priests, certain Christians, with distinctively Arabic names, although they are mentioned alongside others with more traditionally Christian (i. e., Graeco-Coptic) names such as Iōhannes and Pisente (= Pisentius).[159] The use of Coptic by individuals with Arabic-origin names is attested as early as the eighth century; these individuals are generally assumed to be converts to Islam, but this is rarely explicit in the letters themselves.[160] One factor which may help us is that, as Bulliet notes, certain Arabic names with a strong Islamic significance seem to have been particularly common among recent converts – Muḥammad, Aḥmad, ʿAlī, al-Ḥasan, and al-Ḥusayn – and several of these are among the names we find in the magical texts.[161] On the other hand, there are certain Arabic names, such as ʿAbd al-Masīḥ (عبد المسيح “Slave of Christ”) which indicate a more or less certain Christian identity; this latter is attested in Coptic documents by tenth or eleventh century.[162] Other names, in particular Biblical names such as Ibrāhīm (=Abraham), Ismāʿīl (=Ishmael), and Yūsuf (=Joseph), also mentioned by Bulliet as common for converts, are more ambiguous, and might be used by Christians, Jews, or Muslims, with an Arabic form perhaps indicating linguistic Arabisation, but not necessarily conversion.[163]

Another problem is posed by the different types of names used by mediaeval Arabic speakers. In their study of Arabic documents from an eleventh-century Faiyum, Christian Gaubert and Jean-Michel Mouton note that of the hundred or so Christians mentioned, all but two had a traditional Graeco-Coptic personal name (ism, pl. asmā), but that some used an Arabic nickname (kunya) in certain contexts.[164] These nicknames are likewise unhelpful for determining religion, since it seems that Muslims, Christians, and Jews might use the same nicknames. A similar phenomenon is found in the laqab (pl. alqāb; honorific) used by women, usually of the form sitt al-XX (“lady of XX”); as Reem Alrudainy, Mathieu Tillier, and Naïm Vanthieghem note, these names were “used by high-ranking women to avoid revealing their ism and thus not to undermine their decency”.[165] More or less identical alqāb are found among Christian, Jewish, and Muslim women from Egypt.[166]

All of this means that any conclusions about the Islamicisation, and even Arabisation, of the population more generally based on the presence of Arab names must be made cautiously. Nonetheless, as I discuss below, my impression is that the patterns which emerge are significant, and while these must be subject to correction by future studies, I think they do tell us something about the processes of Egyptians converting to Islam and using Arabic in their daily lives. There are 12 names which I can confidently classify as Arabic in origin, of which only one, Ahmēt, occurs more than once; these are listed and briefly discussed in Table 3.

Arab names in applied magical Manuscripts from Egypt in Coptic.

Name: Aptellah Source: P.Berlin 8503 (Beltz (1984) no. III 23; KYP M495; TM 99586; VIII–IX CE) Form in papyrus: ⲁⲡⲧⲉⲗⲗⲁϩ (ro ll. 34, 60; vo. l. 5); ⲁⲡⲧⲁⲗⲗⲁϩ (ro ll. 44 – 45) Arabic form: عبد الله Arabic transliteration: ʿAbd Allāh Role: client |

Name: Ahmēt Source: a) P.Heid.Inv. Kopt. 544b (Quecke (1963) no. 1; KYP M365; TM 98048; X–XI CE); b) Louvre E 14251 (KYP M3734; unpublished; Edfu, likely X–XI CE) Form in papyrus: ⲁϩⲙⲏⲧ (a l. 16; b l. 25 et al.) Arabic form: احمد Arabic transliteration: Aḥmad Role: a) client; b) father of target Comments: Cf. the same name in the letter P.Lond.Copt. I 584 l. 2 (perhaps VIII–IX CE). Ahmēt (a)’s mother is named Mariam (ⲙⲁⲣⲓⲁⲙ), which could be suitable for either a Christian or a Muslim; here I err on the side of caution and consider it as “Christian” in my analysis.[167] |

Name: Alhōseein Source: Louvre E 14251 (see above) Form in papyrus: ⲁⲗϩⲱⲥⲉⲉⲓⲛ (l. 25 et al.) Arabic form: الحسين Arabic transliteration: Al-Ḥusayn Role: target |

Name: Cauhare Source: Louvre E 14.250 (Drioton (1946); KYP M367; TM 99997; X CE) Form in papyrus: ϭⲁⲩϩⲁⲣⲉ (ro. ll. 10 – 11 et al.); [ϭⲁⲩϩⲁ]ⲣⲉϩ (ro l. 22) Arabic form: جوهرة Arabic transliteration: Ǧawhara Role: target and mother of target Comments: Cf. Drioton (1946) 481. |

Name: Ḫarip Source: Cambridge UL T-S 12.207 (Crum (1902); TM 99585; KYP M534; Cairo, X–XI CE Form in papyrus: ϧⲁⲣⲓⲡ (l. 2 et al.) Arabic form: غريب Arabic transliteration: Ġarīb Role: target Comments: The Arabic form here is that proposed by Crum (1902). Its apparent meaning (“strange”, “foreign”), might make it resemble a pseudonym, but it is attested in several Arabic papyri.[168] Note that غ in Coptic is usually rendered by gamma, kappa, or even kjima, whereas khai would normally be expected for خ (cf. Richter (2017) 518). |

Name: Harōn Source: Os.Mil.Vogl. inv.1 & Leiden F 1965/8.5 (see Dosoo (2021d); TM 874161 & 99589; KYP 535 & 1159 (X CE?) Form in papyrus: ϩⲁⲣⲱⲛ (Os.Mil.Vogl. inv.1 ll. 34, 66 – 67; Leiden F 1965/8.5 concave ll. 19 – 20, 39 – 40, convex ll. 20 – 21, 39, 78) Arabic form: هارون Arabic transliteration: Hārūn Role: target Comments: Two manuscripts containing variants of the same text, written in the same hand, and so treated as a single manuscript here. The normal Coptic form of the name, equivalent to English ‘Aaron’, would seem to be ⲁⲣⲱⲛ (TM NamVar ID 52920), from the Greek Ἀ(α)ρών (TM NamVar IDs 7857 & 29217). The forms with an initial hori (TM NamVar IDs 52407, 52409 & 113316) likely represent the Arabic form Hārūn; all the precisely dated attestations post-date 642 CE. Harōn’s mother, Tkouikira, has a Graeco-Coptic name. |

Name: Mahēt Source: Vienna K 7089 (Stegemann (1933 – 4) no. 15; KYP M246; TM 91407; X–XI CE) Form in papyrus: ⲙⲁ/ϩ\ⲏⲧ (l. 2) Arabic form: مهد (?) Arabic transliteration: Mahid (?) Role: client Comments: We might alternatively understand an erroneous writing of Muḥammad; cf. ⲙⲁϩⲙⲏⲧ in P.Lond.Copt. I 664 l. 1. Mahēt’s mother is named Zoe (ⲥⲱⲏ). As discussed below, this is likely a generic placeholder. |

Name: Mouflēh al-Pahapani Source: P.Berlin 8503 (see above) Form in papyrus: ⲙⲟⲩϥⲗⲏϩ ⲁⲗⲡⲁϩⲁⲡⲁⲛⲓ (ro ll. 18 – 19, 46 – 47, 51, 58; vo ll. 3, 4); ⲁⲡⲁϩⲁⲡⲁⲛⲓ (ro ll. 31 – 32); ⲁⲗⲡⲁϩⲁⲗⲡⲁⲛⲓ (ro l. 49); ⲁⲡⲡⲁϩⲁⲛⲓ (ro l. 53) Arabic form: مفلح Arabic transliteration: Mufliḥ Role: target Comments: Beltz (1984, no. III 23) understands ⲙⲟⲩϥⲗⲏϩⲁⲗⲡⲁϩⲁⲡⲁⲛⲓ as a single long name, but the first element is clearly the name Mufliḥ; the second element, difficult to identify, is likely a nisbah prefixed by the definite article al‐. |

Name: Poulpehe Source: EES 39 5B.125/A (Alcock (1982); KYP M280; TM 98045; Oxyrhynchus, XI CE) Form in papyrus: ⲡⲟⲩⲗⲡⲉϩⲉ (ll. 15, 24, 41) Arabic form: ابو البهاء Arabic transliteration: Abu l-Bahā Role: client Comments: The original editor read the name as ⲡⲟⲩⲗⲡⲉϩⲉⲡⲩⲥ (Alcock 1982), but the last element is in fact ⲡ-υ(ἱό)ς “the son”; he nonetheless recognised that the first element of the name might be Abu, whose full writing is ⲁⲡⲟⲩ (cf. Legendre (2014) 342; but cf. also fn. 157); the second element is likely bahā (بهاء “splendour”); cf. the same name in P.Heid.Arab. II 11 l. 21 right margin (XII CE) and the numerous Judaeo-Arabic attestations in the Cairo Genizah, transcribed as אבו אלבהא.[169] The mother’s name, Zarra (ⲍⲁⲣⲣⲁ) is likely a form of Sarah, and could be appropriate either for a Christian or a Muslim; here I err on the side of caution and consider it as “Christian” in my analysis. Cf. the similar female laqab Sitt al-Bahā, attested for a Christian Egyptian woman in a marriage contract of 1246 CE (see fns. 157, 164). |

Name: Seinape Source: P.Mil.Vogl.Copt.inv. 22 (van der Vliet (2005a); KYP M67; TM 91345; Luxor, X–XI CE) Form in papyrus: ⲥⲉⲓⲛⲁⲡⲉ (l. 16) Arabic form: زينب Arabic transliteration: Zaynab Role: client Comments: The mother’s name is lost; it begins with sigma. For the identification of the name as Zaynab, see van der Vliet (2005a). The final epsilon is unexpected. |

Name: Sit el-Khoul Source: Cambridge UL T-S 12.207 (see above) Form in papyrus: ⲥⲓⲧ ⲉⲗⲭⲟⲩⲗ (ll. 1 – 2 et al.) Arabic form: ست الكل Arabic transliteration: Sitt al-Kull Role: mother of target Comments: The Arabic form here is that proposed by Crum (1902). Despite its rather surprising meaning (“Mistress over Everyone”), superficially implying a generic name along the lines of “Eve”,[170] names of the form “Sitt al-”, including Sitt al-Kull, are well-attested in the Arabic-speaking world.[171] |

Name: Sōliman Source: Vienna K 7092 (Stegemann (1933 – 4) no. 1; KYP M249; TM 91410; X–XI CE) Form in papyrus: ⲥⲱⲗⲓⲙⲁⲛ (l. 12) Arabic form: سليمان Arabic transliteration: Sulaymān Role: client Comments: King Solomon is considered a key figure in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, and so derivatives of the name would be equally appropriate for members of any of the three faiths. Nonetheless, the normal Greek and Coptic (and hence, early Christian and Jewish) form is Σολομῶν, whereas the vocalisation here is that of the Arabic form (cf. Legendre (2014) 334, 348). |

Outside of these four categories are a fifth category of “miscellaneous” names; Bagnall distinguished some of these as explicitly “pagan”, but I prefer to describe them as those to which no religious identity can be imputed with any degree of certainty.[172] I should briefly note that this classification system, focused on the question of the transition to Christianity in Egypt, leaves unexplored many other questions upon which onomastic analysis might shed light.

Name Category Frequencies in the Corpus.

Name category | No. of names | No. of individuals | Average no. of individuals per name | |

All names | 268 | 371 | 1.4 | |

Unmarked | 220 | 281 | 1.3 | |

Christian | 36 | 77 | 2.1 | |

Old/New Testament | 22 | 52 | 2.4 | |

Anon. Theophoric | 10 | 16 | 1.6 | |

Abstract | 4 | 9 | 2.3 | |

Arab | 12 | 13 | 1.1 | |

While we cannot look into every name in detail, it is worth briefly noting the frequencies of the different categories (Table 4). We can see considerable imbalance between the different categories of names. Most names in the corpus are nearly unique – each name being borne by 1.4 individuals, and this is even more visible for the “unmarked” names, with each borne by 1.3 individuals. In practice, 211 of the 268 names have one attestation, 27 have two attestations, 17 have three, and 13 have four to six. The Arab names, as we have noted, are very rare, with each borne by 1.1 individuals – only Ahmēt appears twice. The Christian names are more frequent, with each borne by 2.1 individuals; in practice, the “anonymous theophoric” names are not particularly frequent – only Theodora appears more than twice, and as a category they each appear 1.6 times. The Testamental and “abstract” names are much more frequent, with each borne by 2.4 and 2.3 individuals respectively.

Fig. 5: Number of attestations for names attested more than three times in the corpus.

If we look at the thirty names which appear three or more times in the corpus, the reasons for these patterns become clearer. Of the four most common names, each appearing six times, three are Christian – Maria, Mariam, and Sophia; indeed the fourth, Thekla should probably be considered a Christian name, even if it is not classified as such by Depauw and Clarysse, and the same goes for Biktōr and Mēnas, two of the next most frequent names.[173] We may also observe that Maria and Mariam, two variants of the same Hebrew name,[174] are by far the most frequent, and that Sophia, the only one of the “abstract” names to appear in the top 30 names, is almost single-handedly responsible for the high average value of this category. Of the remaining common names, a large proportion are Testamental names – Iakōb, Iōhannes, Anna, Iōhanna, and Sara. Zōē, likewise frequent, is a slightly different case – as discussed further below, it likely refers to the Biblical Eve as the mother of all humankind, rather than representing a real personal name. The overall impression is that Christians drew upon a smaller range of names which were borne by more people, and that this tendency was even more marked for women – of the marked Christian names for men, each is borne by an average of 1.5 individuals, close to the corpus average of 1.4, whereas marked Christian female names are borne by an average of 2.8 individuals. In most cases, these are names from the Old or New Testament, particularly Mary. While, as discussed below, analysing such patterns poses problems of interpretation, we might see this as a result on the one hand of a centralisation of ideological power – a large number of deities, virtues, and so on replaced by a smaller cultural repertoire under Christian domination – and on the other, perhaps, the broader range of social roles which men might occupy, reflected by the larger repertoire of names which might express their parents’ hopes for their character, as opposed to the relatively restricted social role expected of women, who tend to be named after Biblical paradigms of purity and motherhood, in particular the Virgin Mary.