Abstract

The study examines the classroom practices of four STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) teachers in an EMI higher education programme in China, investigating how they utilise diverse language resources to recalibrate epistemic frameworks in a knowledge (co)construction process. Drawing on class observations and interviews, the study moves beyond the flexibility of language use in EMI lessons to explore the intricate relationships between languages, semiotics, and knowledge systems in EMI teaching. The findings reveal that EMI teachers employed varied translanguaging strategies to facilitate knowledge co-construction, leveraging teachers’ and students’ existing knowledge as valuable learning resources. The epistemic diversity of bilingual teachers and students was recognised as an asset, breeding opportunities for knowledge development with a glocal grounding in EMI. Nonetheless, the study also highlights the need for greater support in raising teachers’ critical awareness of the ideologies underlying EMI and enhancing recognition of the transknowledging value of translanguaging pedagogy.

1 Introduction

English has been increasingly adopted as a medium of instruction (EMI) worldwide as part of the internationalisation of higher education. Scholarly interest has focused on EMI policies and practices in higher education, particularly their educational, linguistic, and ideological impacts – especially in regions such as Asia and Europe where English is not the first language and bilingualism or multilingualism is common. EMI policies often sustain linguistic tensions, as English monolingual ideologies prevail, reinforcing social inequality in education and affecting bilingual competence (e.g. Rafi and Morgan 2024; Song and Lin 2020). While EMI facilitates knowledge dissemination, it has also been implicated in perpetuating Anglo-Eurocentric perspectives, marginalising indigenous knowledge systems, and devaluing teachers’ and students’ L1 for knowledge construction (Gu and Lee 2019; Heugh 2021; Song 2023).

In response to these concerns, EMI research has increasingly focused on translanguaging – the flexible use of diverse multilingual and multimodal resources for communication and meaning-making in educational settings (García and Li 2014). Relevant studies have extensively explored students’ and teachers’ perceptions of translanguaging in EMI (e.g. Kuteeva 2020; Sahan et al. 2025) and bi/multilingual teachers’ translanguaging practice and their policy implications (e.g. Ou et al. 2024; Rahman and Singh 2022). Research highlights the positive effect of translanguaging on EMI students’ content learning (e.g. Wang and Curdt-Christiansen 2019) and language development (e.g. Mbirimi-Hungwe 2016). As a response to English monolingual ideologies, translanguaging has been recognised for its decolonising power and ability to empower multilingual users (e.g. de Los Ríos and Seltzer 2017; García et al. 2021). It also supports knowledge plurality and fosters locally situated knowledge production (Song and Lin 2020).

Recently, scholars have expanded this critical discourse by introducing transknowledging – a process that involves informal and formal uses of translanguaging alongside a two-way exchange of knowledge systems (Heugh 2021). The concept addresses global inequalities in knowledge production and elevates indigenous knowledge mediated by minority languages (García et al. 2021; Santos 2014). Transknowledging extends the scope of translanguaging by highlighting the transformative role of languages and semiotics (Lemke and Lin 2022). As Li Wei (2022: 180) argues, “translanguaging is … fundamentally reconstitutive of the power structures between named languages, knowledge systems, and pedagogic practices.” In EMI contexts, Kubota (2021) urges researchers to move beyond language flexibility to examine EMI teachers’ and students’ actual learning experiences, subjectivities, and knowledge equity. Responding to this call, a growing scholarly attention in East Asian and European higher education has been paid to how teachers employ translanguaging pedagogy to decentre American/European-centric content knowledge and promote epistemic justice in EMI curricula (Paulsrud et al. 2021; Song 2023). Nonetheless, further research is needed to understand how transknowledging unfolds in discipline-specific EMI classrooms, particularly in STEM fields, and how EMI teachers employ moment-by-moment translanguaging strategies to enable transknowledging and facilitate student learning.

This classroom-based study addresses this gap by investigating the role of translanguaging in bilateral knowledge exchange in EMI-STEM classes at a higher education institution in Mainland China. EMI-STEM classrooms were selected due to EMI’s widespread adoption in STEM disciplines, notably in China (Jablonkai and Hou 2021), and the contrasting scarcity of knowledge on translanguaging pedagogy within such classroom settings (Ou and Gu 2024). Grounded in translanguaging and transknowledging theories, this study explores classroom language use and teaching practices of four teachers from different STEM subjects, closely examining the process by which these teachers navigate diverse linguistic and semiotic resources and integrate students’ L1 knowledge systems to enhance dynamic knowledge co-construction and epistemic justice.

The study was guided by the following research questions:

RQ1:

How do STEM teachers in a Chinese EMI higher education institution engage in translanguaging practices within their classroom teaching?

RQ2:

How do their translanguaging pedagogies impact students’ knowledge construction?

This study aims to uncover the strategies, challenges, and transformative potential of translanguaging in advancing transknowledging within EMI education. It has significant implications for promoting a more inclusive and equitable approach to knowledge production, particularly in STEM disciplines, where the intersection of language and specialised content knowledge is pivotal. The findings are hoped to contribute to the ongoing dialogue on translanguaging, transknowledging, and epistemic justice in higher education, with a specific focus on the dynamic context of Chinese EMI-STEM classrooms. By closely examining STEM teachers’ classroom practices and understanding their needs, this study seeks to inform EMI curriculum and policymaking from a translanguaging perspective and guide relevant teacher training.

2 Translanguaging and knowledge co-construction in EMI

Affixing ‘trans-’ to languaging, translanguaging theory aligns with notions like flexible multilingualism, emphasising fluid, dynamic language practices and an open view of communication (see Li 2018, for a systematic review). Recent developments in translanguaging theory also highlight the role of non-linguistic resources – traditionally categorised as multimodalities, objects, and other environmental/material resources – as integral, agentive components of communication repertoires (cf. Canagarajah 2018). In EMI contexts, translanguaging is a “normative practice” (Simungala and Jimaimato 2021: 1,655) for teachers and students, facilitating communication and learning. It has been identified as an effective tool for increasing linguistic legitimacy and cultural diversity in English-dominant academic settings (e.g. Gu et al. 2024; Ou and Gu 2024; Tsou and Baker 2021). It is also considered a transformative pedagogy (Lemke and Lin 2022) that addresses challenges in content knowledge construction and language development (Lin 2019).

Knowledge production is a key site of socio-political power, shaped by colonisation, imperialism, and neo-imperialism (Chen 2010). As translanguaging researchers argue, EMI is value-bearing in that English serves as a framework that categorises knowledge, cultures, and people. It constructs a system where English speakers are perceived as “metropolitan, educated, knowledgeable, desirable, and progressive,” while non-English speakers are often marginalised as “uneducated and underdeveloped whose existing knowledge acquired through other languages is backward and disposable” (Li 2022: 179). Research shows that translanguaging in EMI legitimises the linguistic and cultural repertoires of teachers and students, drawing on their educational and social experiences to create new epistemic frameworks, alternative perspectives, and new teacher/learner identities (e.g. Li 2022; Ou and Gu 2022; Song and Lin 2020). Its transformative impact has been documented in different contexts, such as Iraq (Alhasnawi 2021), China (Fang and Liu 2020), and South Africa (Mbirimi-Hungwe 2021).

Translanguaging has been shown to enhance students’ subject content understanding. By leveraging all available linguistic resources, university teachers can engage students in key concepts, contextualise knowledge with local examples, and deepen understanding (Rahman and Singh 2022; Wang and Curdt-Christiansen 2019). In STEM contexts, translanguaging has been identified as a crucial tool for knowledge construction and teacher-student interactions (e.g. Alhasnawi 2021; Rahman and Singh 2022). STEM teachers prioritise content learning in EMI (Roothooft 2022) and often see themselves as subject specialists rather than language tutors (Block and Moncada-Comas 2022). Furthermore, transepistemic and transcultural processes have been observed in EMI classes, highlighting the need to enhance both teachers’ and students’ transepistemic awareness (Gu et al. 2023; Song 2023). In the following section, the theoretical notions of translanguaging and transknowledging are discussed, and their relevance to this study is elaborated.

3 Theoretical framework: translanguaging and transknowledging

Within the framework of translanguaging as a practical theory, “multilinguals do not think unilingually in a politically named linguistic entity, even when they are in a ‘monolingual mode’ and producing one nameable language only for a specific stretch of speech or text” (Li 2018: 18). In this view, translanguaging emphasises that languages are historically, politically, and ideologically constructed and serves as a theoretical guide to understanding human beings’ creative and dynamic language practices (Li 2018). The concept of multilingualism has been redefined to recognise individuals’ awareness of named languages and their underlying rule and structures as well as their abilities to naturally draw on “bits and pieces” of linguistic resources from their repertoires and use them flexibly for communication.

Heugh (2021: 43–44) proposes the notion of “transknowledging,” signalling “the knowledge exchange and production process” and argues that translanguaging practices evoke “two-way exchanges of knowledge systems.” Transknowledging regards knowledge as historically, ideologically, and socio-culturally situated and mediated by languages and semiotics. Heugh (2021:45) further argues for the “complementary and systematic use of translanguaging pedagogies” and culturally responsive pedagogies (Osborne et al. 2020) to facilitate reciprocal knowledge exchange and production. As Heugh (2025) notes in another contribution to this special issue, transknowledging – though not always acknowledged – is consistently evident in classrooms in the Global South, where teachers promote the use of translanguaging for knowledge exchange. It can encourage students to contest the “universal” logics and assumptions rooted in colonialism and recongise the knowledge systems embedded in local/indigenous languages. Therefore, translanguaging and transknowledging approaches are particularly relevant to promoting educational equity in EMI contexts, as they foster language and epistemic diversity, value the resources of different communities, and empower students by acknowledging their agency and voice.

From a translanguaging and transknowledging perspective, we are able to develop an in-depth understanding of the diverse knowledge construction processes in EMI classrooms by examining how teachers and students draw on their shared linguistic and semiotic resources, human agents, and artefacts in a coordinated and integrated manner (Lin et al. 2020). Moreover, we can explore the moment-to-moment transepistemic process and examine whether and how teachers agentively construct glocal ecologies in knowledge construction that “delink from the colonial praxis of knowing” (Song and Lin 2020: 252) and relink the local and global (Rose et al. 2022).

4 The study

The study was conducted at an interdisciplinary STEM institute within a top-tier comprehensive university in Southeast China. The institute provides four undergraduate, three master’s, and one doctoral programme in mathematics, physics, chemistry, and biological sciences. The institute envisions itself as an internationalised EMI faculty that fosters collaborations with overseas world-class universities and adopts “an English-based bilingual teaching” (quoted from the institute’s policy text). The university website statistics show that the institute admits approximately 60 undergraduate students, 60 postgraduate students, and 60 doctoral students per year, with the postgraduate programmes open to international students. Most faculty members are of Chinese descent, but all have obtained postgraduate degrees abroad (primarily in English-speaking countries).

For this article, we drew on class observations and individual interviews with four STEM teachers during the spring semester in 2021. The teachers (pseudonyms: Ye, Ming, Zhao, and Jerry) were sampled for their varied linguistic and educational backgrounds, teaching experiences, and specialised disciplines (Table 1). Specifically, Ye, Ming, and Zhao are Mandarin L1 speakers and teaching-research fellows, while Jerry – an experienced full-time teaching staff without research duty – is an English-Cantonese bilingual who completed his education and teaching career outside Mainland China. All of them taught at least two undergraduate courses during the study, with all students being Mandarin L1 speakers from Mainland China. Each teacher was observed for two 90 minutes' classes of the same course. Field notes were taken during the observations. With permission, all the observed classes were also video-recorded except Zhao’s, where the second author documented the detailed classroom interactions and teaching activities through field notes. After the observations, teachers participated in semi-structured interviews about their perceptions and strategies of EMI teaching and students’ learning outcomes. Each interview lasted 30–60 minutes, was recorded, and transcribed by an independent researcher for further analysis. To help the teachers fully express themselves, the interviews were conducted in their L1 (English for Jerry and Mandarin Chinese for the others). Chinese transcripts were translated into English by the authors when cited in the article.

Demographics of the STEM teachers.

| Teacher | Gender | Self-reported language ability | Discipline | Education background | Teaching experience (year) | Courses (EMI) | The observed classes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ye | Male | Mandarin Chinese (L1) English (working proficiency) |

Physics | Undergraduate (China) Postgraduate (Hong Kong) |

6 | Material characterisation; semiconductor physics (undergraduate level) | Material characterisation |

| Ming | Female | Mandarin Chinese (L1) English (working proficiency) |

Chemistry | Undergraduate (China) Postgraduate (the UK) |

3 | Chemistry (undergraduate level) | Analytical chemistry |

| Zhao | Female | Mandarin Chinese (L1) English (working proficiency) |

Physiochemistry | Undergraduate (China) Postgraduate (the USA) |

6 | Polymer physiochemistry (undergraduate level) | Macromolecules diffraction |

| Jerry | Male | English (L1) Cantonese (L1) Mandarin Chinese (intermediate-level, not for academic communication) |

Microbiology | Undergraduate (Canada) Postgraduate (Hong Kong; the UK) Post-doc: the UK |

27 | Microbiology; biotechnology; monocular-biology and recombinant DNA (all undergraduate level) | Microbiology |

Following linguistic ethnography traditions, data analysis was ongoing and concurrent with data collection. Initial analysis occurred during observations, focusing on each teacher’s use of linguistic and non-linguistic resources in moment-by-moment classroom interaction and their effects on student learning. Coding was guided by translanguaging and transknowledging theories, with descriptive, conceptual, and simultaneous codes noted in the field notes. After fieldwork, interview transcripts, field notes, and video-recordings of EMI classes were assembled and analysed holistically, linked for triangulation and a comprehensive understanding of ethnographic complexity (Copland and Creese 2015). This approach ensured that interpretations of classroom interactions were co-constructed from both participant and researcher perspectives. Only representative classroom moments where teachers justified their actions and motives of language use were included for further analysis and data presentation.

In addition, a multiple case analysis method (Stake 2006) was employed to analyse and report our data. Focusing on the quintain – translanguaging pedagogical practices and transknowledging process in EMI teaching – we investigated across the four teachers’ cases to look for specific translanguaging pedagogical strategies in each class and compare their teaching experiences and beliefs for similar or contrasting patterns and their effects on students’ language and content learning. From these combined and comparative insights, we could address the complex problems within EMI-STEM teachers’ translanguaging practices for knowledge construction in their local contexts.

5 Findings

The four teachers understood that their institute adopts a flexible EMI policy: while teaching materials (e.g. textbooks, slides) and assessment must be in English, teachers have autonomy in classroom language use. All of them supported this translanguaging-oriented EMI policy, having learned from experience that English-only teaching is challenging for their students, most of whom are Chinese undergraduates with no prior EMI exposure. To support both content knowledge learning and language development, the four teachers drew on their different linguistic, cultural and subject backgrounds to develop distinct translanguaging practices for knowledge co-construction: strategic English-dominated translanguaging (Jerry), embodied performance drawing on academic English and material resources (Ye), translanguaging in response to knowledge construction flow (Ming), and translanguaging to validate L1 knowledge systems (Zhao). In the following, we analyse these translanguaging pedagogies and explore the teachers’ underlying EMI language ideologies in turn.

5.1 Jerry: strategic English-dominated translanguaging for students’ academic English development

Jerry differs from the other teachers as a native English speaker and “foreign scholar” who developed his epistemic framework entirely outside China. He strategically adopted an English-dominated translanguaging approach, incorporating everyday and academic English, minimal Chinese, and multimodal resources in the classroom. Our observations show Jerry had highly interactive teacher-student engagement, despite speaking only English in class. His students actively asked questions, responded immediately to Jerry’s prompts, and initiated discussions – entirely in English. They also used semiotic and environmental resources to express ideas, such as writing answers on the whiteboard in English, circling key points for emphasis, and other strategies.

Like the other teachers, Jerry was aware of the students’ (insufficient) academic English proficiency. Therefore, he intentionally provided the Chinese translation of some important thematic terms to help students understand the content knowledge and strengthen their acquisition of technical terms, as illustrated in Figure 1:

Jerry providing Chinese translation to the thematic term.

In the interview, Jerry explained his choice of Chinese translation:

Jerry: In my first year of teaching, I didn’t use any of those. Then I realised that many students didn’t understand the English terms. So, I started looking for these so-called “Chinese translations,” even though I wasn’t sure if they are accurate or not.

Amy: Do you think the students understand better?

Jerry: They understand better – because already have the background knowledge, but in Chinese. When I introduce an English term and ask “Have you learned this before?” they shak their heads. But when I give them the Chinese translation, they immediately respond, “oh, okay!” They actually know the concept; they just don’t recogise the English word for it.

The excerpt above reflects Jerry’s awareness of how students’ L1 Chinese knowledge of concepts, methods, and reasonings support their EMI learning. Despite his limited (academic) proficiency in Chinese, he used Chinese translations to activate students’ prior content knowledge and facilitate their learning in English. His decision to incorporate Chinese translations for thematic and technical terms stemmed from his teaching experience in EMI classrooms, where he observed that translation helped students establish cognitive links between knowledge constructed in Chinese and English, thereby enabling transknowledging (Heugh 2021).

In addition to using Chinese translations, Jerry frequently checked students’ understanding and clarified concepts using “simpler” English. In the following example, he builds semantic connections between words while explaining the thematic concept of “homodimer.”

Jerry: It’s found by the proteins known as the CDE-one homodimer. You know the term “homo”? I think I have talked about this one. “Homo” means the same, “hetero” is different. Homodimer simply indicates dimers two, which means the same protein. … It is called primosome transmission felicity. Do you know “felicity”? Accuracy. So, unfortunately, sometimes scientists cannot use the term to indicate a particular function, they do not use the term “accuracy.” They use the term “felicity” because they can’t be managed by protein, they can’t be affected by the DNA sequence, they can’t be affected by many other factors.

Along with introducing the semantic relationship of antonyms, “homo” and “hetero,” Jerry also used synonyms (“accuracy”) to help students understand the academic term “felicity” in the context of “transmission felicity.” This approach bridges students’ everyday L2 vocabulary with academic discourse specific to the subject. His translanguaging pedagogy and transknowledging not only move between different linguistic knowledge systems but also within the same language, guiding students from everyday to academic English in EMI settings.

Jerry’s teaching reflects an explicit language-learning objective for EMI students. In the interview, he expressed concerns about students’ ability to produce academic English at an appropriate level, particularly in written exams. As he noted:

Jerry: The problem will probably be the students’ performance in the final exam. Even though this cohort seems to understand the material for now, whether they truly comprehend the exam questions is another matter.

To address this, Jerry provided additional English writing exercises for his students. He also introduced weekly online exercises and pre-class quizzes to track their progress and better prepare them for EMI lessons. These measures allowed him to adjust the content and difficulty of upcoming sessions based on students’ learning outcomes.

Jerry’s lack of proficiency in his students’ L1 (Mandarin Chinese) and his limited familiarity with their epistemic framework, compared to his local colleagues, both constrained and shaped his teaching strategies. Unlike local Chinese teachers, he could not provide immediate verbal translations for technical terms or key concepts. Instead, he employed alternative strategies to support students’ knowledge construction, such as weekly quizzes to monitor their comprehension and structured writing exercises to strengthen their academic English. Relying less on Chinese, Jerry actively engaged students through multimodal resources, using visual aids to reinforce his explanations. He also helped students bridge their everyday L2 vocabulary (e.g. accuracy) with academic terminology (e.g. felicity), making explicit connections between word meanings and subject-specific language.

5.2 Ye: teaching as embodied performances drawing on academic English and material resources

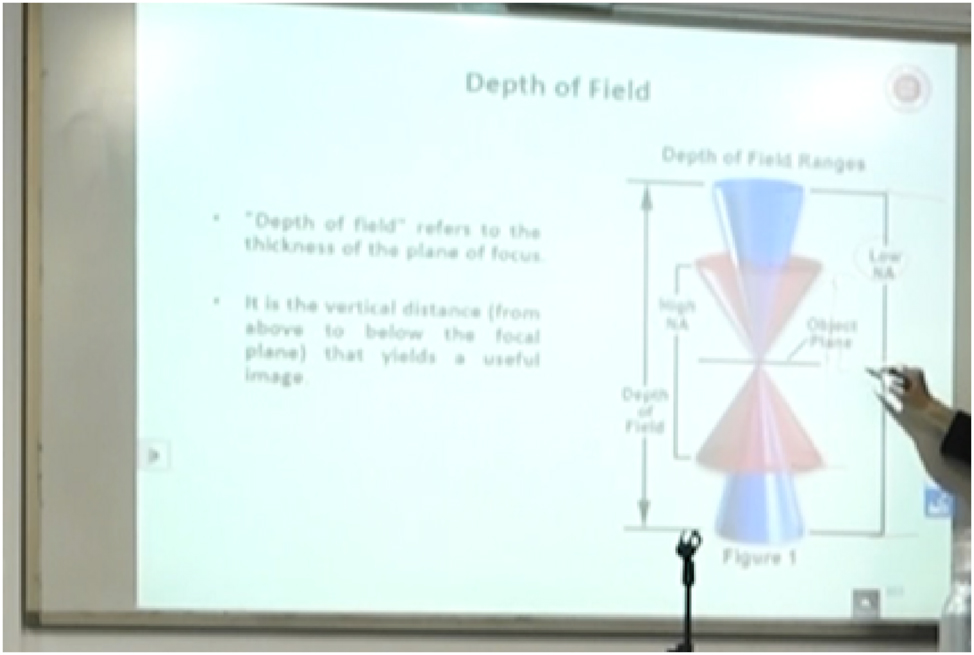

Ye’s EMI instructions present an embodied teaching that integrates both linguistic and non-linguistic resources, including academic English, Chinese, and various multimodal resources such as diagrams, charts, drawing, circling, colours, and physical gestures. In Ye’s classroom, PowerPoint slides were projected directly onto the whiteboard. While he minimised his Chinese use (reserving it only for translations of specific thematic concepts), he primarily communicated in English, using whiteboarding to visually express his ideas. For example, in the following excerpt, Ye elaborated on a schematic graph by drawing notes on the slide, and actively engaged with the content displayed (Figure 2):

Ye: Why we introduce this idea? Because in the optical axis, for different objective lenses, we have different depths of field, you can see here are two examples. One example is the objectives with highly reactive. So here is highly reactive, the red one. And an objective lens with lowly reactive. That is a blue one. You will find that if we have an objective lens with highly reactive, that’s a vertical distance from above to below, the distance will be shorter. If we have a lowly reactive, then you will see that, here LH, high, and LL, low. This one will be longer.

Ye drawing notes on the slide to elaborate the schematic graph.

Ye illustrated semantic relationships, such as attribute antonyms like “highly reactive” versus “lowly reactive” and “longer” versus “shorter” distance, by using two objects with contrasting attributes. In another example of a semantic relationship, colour attribution, he used “blue” and “red.” These relationships between thematic concepts helped students master thematic patterns (Lemke 1990; Lin and Lo 2017). Ye’s knowledge-building process was not merely reliant on verbal explanations; it also incorporated material resources, such as drawings, diagrams, visuals, and gestures. In particular, Ye actively used diagrams to show varying colours, distances, and levels of reactivity, for meaning-making and knowledge construction. He mainly adopted “monologue strategies” (Lemke 1990) to lecture on thematic concepts and their semantic relationships, fostering students’ understanding of thematic patterns, i.e., the subject knowledge itself.

In sum, Ye made his teaching an embodied activity through translanguaging practices featuring an interactive and integrated use of academic English, digital multimodalities and body movements for meaningful instructions. He used a range of semantic relationships to clarify content knowledge and engaged his body alongside verbal and multimodal resources to convey his ideas. While his pedagogical approach effectively assisted students in navigating the intricate knowledge structure of academic English, his strong focus on near-monolingual English instruction limited opportunities for transknowledging to take place in his classroom.

5.3 Ming: translanguaging as a response to knowledge construction flow

Different from Jerry and Ye, Ming used more Chinese in her teaching. Our observation shows that Ming did not simply use Chinese for translating certain scientific terminologies; rather, she flexibly deployed Chinese as a pedagogical resource for elaborating knowledge, connecting sentences, giving instructions, and managing the class. Her translanguaging pedagogy demonstrates a strategic use of multilingual resources to ensure a smooth flow of knowledge co-construction between herself and students. Ming was attentive to students’ moment-to-moment comprehension, continuously adjusting her language to meet their cognitive needs.

Translanguaging and transknowledging occurred in “real-time meaning-making” (Lin 2019: 8), utilising different styles, registers, and semiotic resources. This is reflected in Ming’s pedagogical practice where meaning was constructed within dialogues:

Ming: So, here we use the Z expression, right? So, in this case, how can we find Z?

The students: From 表格 [the table]?

Ming: 直接從表格裏是吧?[Directly from the table, right?] 直接從表格裏的95%, 就可以找到Z了,這些都是一一對應的, okay? [You can find Z directly from the 95% in the table. One by one corresponding, okay?] 只有在T表格裏面他才跟 probability 有關係,在 Z 表格裏面,是跟 number of measurement 是沒有關係的, 因爲我們已經知道了他的總體的標準變量是多少了。[It is related to the probability only in the T table. In the Z table, it is independent of the number of measurements, since we’ve already known the total number of its standard variable.] So, we find the Z data from the Z table, which is 0.95, right? And then the sigma, which is 0.05, then also divided by square root of three. Then we get a confidence interval expression, like this, right?

In this extract, when students answered in Chinese, Ming immediately switched to Chinese to follow the students’ language and knowledge construction flow, explaining the calculations based on the rule presented in English. She then naturally switched back to English to continue explaining terms like “Z data” “sigma,” and “confidence interval,” guiding students through the content in academic English.

Transknowledging occurred as Ming activated students’ various linguistic-epistemic systems at both the global and local levels for knowledge co-construction. While the consistent use of academic English exposed students to global academic conventions and frameworks mandated by the EMI curriculum, Ming’s incorporation of both everyday and academic Chinese connected learning to its local grounding. Specifically, using daily Chinese facilitated students in surmounting pontential language hurdles and enabled their deeper engagement with abstract concepts. Moreover, Ming employed academic Chinese terminologies (e.g. 標準變量) to connect students to prior disciplinary knowledge in their L1, facilitating the integration of both L1 and L2 knowledge systems. Ming’s teaching may foster a glocal knowledge system among students, allowing them to link local knowledge with global frameworks without prioritising one over the other, potentially enhancing intercultural competence (i.e., appreciating the value of diverse knowledge traditions), critical thinking, and multi-directional knowledge flow.

Ming was also sensitive to students’ language needs, adjusting her translanguaging practices based on content difficulty and students’ familiarity. She provided bilingual versions of some material to reinforce content knowledge:

Ming: How can we do the testing? For example, how can we compare certain results from your measurements to the true value. Right? And how can we evaluate the results from 2 types of management. Right? 就是説我們要怎麽去評價, 比如說我們檢測出一個結果, 我們要怎麽去評價你這個結果跟真實值有沒有一個明顯的差別? [That is, how can we evaluate, for example, if we detect a result, how can we evaluate that your result is not significantly different from the true value?] 以及如果是兩次實驗, 兩種不同的檢測, 他們之間有沒有區別? [Also, if there are two experiments with two different tests, are there any differences between them?] We know that we usually write down the state of a kind of measurement results like the confidence interval, the expression, right? That’s how we express the results, right? But how can we compare if these two results are identical, or similar, or if there’s a significant difference or not?

In the example above, Ming gradually put forward the knowledge point in three stages: starting in English with an immediate “Chinese translation.” It is important to note that her English and Chinese explanations were related but not identical; Chinese served to elaborate the idea with an example. She then continued in English, using a specific example for presenting measurement results, the “confidence interval.” This is followed by a question on comparing two results and introducing “similar” as a synonym for “identical” to link students’ everyday L2 language to more academic vocabulary. This approach demonstrates how Ming used translanguaging to gradually build meaning – a flow in the “shorter-timescale processes” (Lin et al. 2020: 71) at the local level – catering to both student knowledge construction and language development at the global level.

Furthermore, Ming often incorporated scientific videos in English, such as one on the T-est (Figure 3) after her lecture on the same concept. She explained:

Ming played an English video on T-test.

Ming used the video for dual purposes: enhancing the students’ understanding of the content and exposing them to “standard” academic English. Her reference to “standard” reflects her self-identification as a STEM professional rather than an English language expert, aligning with an English native-speakerist language ideology common among EMI teachers (Block and Moncada-Comas 2022). Perhaps without full awareness of the transknowledging value of her translanguaging pedagogy, Ming, on the one hand, engaged her students in glocal knowledge construction, encouraging their knowledge development in both academic Chinese and English epistemic systems, but on the other hand reinforced the dominant status of “standard” English in EMI teaching. This contradictory practice may undermine the effectiveness of transknowledging. As Heugh (2025: 11) notes, transknowledging can be implicitly activated when translanguaging pedagogy is used, but it cannot be harnessed unless “equibalanced, two-or-multiple way linguistic and epistemic exchanges are deliberatively facilitated” (emphasis added by authors).

5.4 Zhao: translanguaging as a process of validating L1 knowledge systems

Among the four teachers, Zhao used the most Chinese in classroom teaching. She prioritised students’ content knowledge construction over exposure to academic English, reasoning that her course was “an advanced-level course where students even struggled to understand the knowledge in their L1” (quoted from the interview). Her translanguaging practice integrates Chinese verbal resources for communication and comprehension with students, while employing English written resources (i.e., texts on the slides) to visualise scientific terminologies and theories. Verbally, she used English sparingly, primarily repeating words from the slides. The follow-up interview explores her motivation for this translanguaging strategy:

Zhao: I am fine with teaching in English only, but the students cannot learn much. There are so many technical terminologies that they need to look up in dictionaries very often if no Chinese explanation is provided. Actually, they have acquired some related knowledge in Chinese in the same subject or other subjects before. The ways of reasoning and theorising are different between English and Chinese knowledge systems. So you may find the Chinese textbooks thinner than the English ones. For them to learn more quickly, I think we should provide Chinese textbooks as well. The students can also learn different ways of thinking and reasoning. If everything is in English, they may spend most of the time understanding the meaning of the terms rather than the content. … I provided the slides and learning materials in English, so students can learn related English after class.

Of the four teachers, Zhao is the only one who explicitly invoked transknowledging in the classroom, emphasising linguistic citizenship (Stroud 2001) within Chinese academia and encouraging students to draw from both L1 and L2 epistemic systems for EMI learning. For instance, when explaining the two interconnected concepts of “diffraction” and “in phase” to students, Zhao said:

其實 diffraction 就是光的繞射, 疊加的後果就是 in phase. [In fact, diffraction is the diviation of light, and the result of superposition of diffraction is in phase.] In phase 就是英文已經說的很清楚了就是 [the meaning of In phase is well explained in English; it is] “difference in the length of the path travelled leads to difference in phase and the phase difference produces a change in amplitude” (reading the English definition on the PowerPoint slide).

Zhao strategically bridged students’ knowledge across two linguistic-epistemic systems – academic Chinese and English in the field of polymer physiochemistry – to facilitate students’ understanding of the two different concepts. She first introduced “diffraction” with its Chinese translation, using “其實…就是” (in fact, it is) to connect the concept to students’ prior L1 knowledge. The Chinese term for “diffraction” (i.e., 光的繞射) is particularly intuitive for Chinese students, as its literal meaning directly conveys the concept, allowing for immediate comprehension. Zhao then moved on to explain the relationship between “diffraction” and “in phase,” incorporating both everyday Chinese and academic Chinese (i.e., 疊加). When defining “in phase,” she referenced its original academic English definition from the course material, believing it to be self-explanatory. This dynamic approach allowed her to navigate multiple epistemic systems without prioritising one over another, fostering a glocal grounding for EMI learning that maximised teaching effectiveness based on student comprehension.

Although Zhao was confident about her English proficiency and EMI teaching ability, she intentionally used more Chinese to help students understand the relationship between scientific terms, reducing time spent deciphering English definitions. Notably, she challenged English monolingualism in EMI knowledge construction and exercised linguistic citizenship in classroom teaching. For example, while explaining scientific thematic concepts, she found some English definitions unnecessarily complicated:

Zhao: 這個米勒指數用英語解釋起來很復雜。 [It is complicated to explain the Miller indices in English.] (referring to the English definition on the PowerPoint slide) 其實它很簡單。 [In fact, it is a very simple concept.] (then she provided explanations in Chinese)

Zhao compared Chinese and English knowledge systems in EMI teaching. Recognising the potential difficulty of English definitions, she prompted students to consider whether an equivalent Chinese explanation already existed in their knowledge repertoire. Rather than treating the English academic framework as the only and the best, Zhao acknowledged the distinct ways of thinking, reasoning, and theorising embedded in different linguistic-epistemic systems. She validated both systems and conveyed this open ideology of knowledge construction to her students. Therefore, her translanguaging practice was not merely a remedial measure to compensate for students’ limited English proficiency but a form of transknowledging – a validating and decolonising process of knowledge construction (cf. Li 2022) – that legitimised students’ linguistic repertoire and L1-based academic knowledge.

Zhao’s pedagogical strategies were well-received by students. Our observation shows that her class had the most dynamic teacher-student interactions among the four participants. This was likely due to her flexible use of Chinese, personal engagement with students in their L1, and openness to the Chinese epistemic system in EMI learning.

6 Discussion

This study examined how STEM teachers with different linguistic repertoires and perspectives on EMI teaching navigated linguistic and semiotic resources in their classrooms and recalibrated teachers’ and students’ knowledge frameworks in a knowledge (co)construction process in a Chinese higher education institution. Our analysis focused on teachers’ moment-by-moment translanguaging pedagogical practices in STEM-EMI classrooms, exploring the intricate relationships between languages, semiotics, and knowledge systems. Consistent with previous research, our findings suggest that all participants employed translanguaging pedagogically to facilitate knowledge co-construction (Lin and He 2017; Wu and Lin 2019). Different languages, semiotics, and modes are intertwined in teacher-learner interactions, supporting meaning-making through scientific explanations, semiotic relations, and thematic content structuring (Lin and Lo 2017). Translanguaging created an affording space for students to actively engage in knowledge co-construction by raising questions, responding to teacher prompts, and providing explanations – drawing on multiple linguistic resources and epistemic systems.

Ming and Zhao appeared to more strategically integrate their shared linguistic repertoires with students in knowledge co-construction (Canagarajah 2018; Lin 2019). Ming’s translanguaging pedagogy was evident in her gradual content explanations in both English and Chinese. She also translanguaged at key points, using L1 everyday language as a bridge before providing explanations in L2 and L1 academic language. By doing so, she mobilised verbal resources beyond rigid language boundaries, creating a fluid knowledge construction flow in both teacher-dominant monologues and interactive dialogues. Notably, she rarely used L2 everyday language, possibly due to her insufficient competence in L2 daily communication. Zhao, in contrast, more frequently employed L1 everyday/academic language alongside L2 everyday language. While L2 academic language appeared in PowerPoint slides, it was used exclusively when the teacher deemed the information self-explanatory (e.g. the definition of “in phase”). Zhao’s approach reflected her belief that content learning should take precedence in advanced-level courses, as well as her recognition of the role of Chinese epistemic framework in facilitating students’ content knowledge development.

In contrast, Jerry’s and Ye’s classrooms were more English-dominant. Ye blended verbal resources with body movements, creating an embodied learning experience for physics in academic English. Jerry, who shared limited linguistic and cultural commonground with students, relied more on thematic development strategies (Lemke 1990) to bridge everyday and academic English for knowledge construction.

A reciprocal relationship between language use and interaction patterns also emerged from our analysis. Student engagement was higher in Jerry’s and Zhao’s classes, despite their contrasting language choices – Jerry using predominantly English and Zhao predominantly Chinese. The findings indicate that greater L1 use is associated with increased classroom interaction (Pun and Macaro 2019), possibly because teachers are more comfortable using everyday L1 for discussions, personal engagement, and topic explorations with students.

Although English structures knowledge in EMI (Li 2022), transknowledging – a reciprocal translation and exchange of knowledge and epistemic systems (Heugh 2021) – was either implicitly or explicitly exercised in the observed EMI classrooms. All four teachers, despite varying degrees of linguistic flexibility, recognise the importance of mobilising students’ L1 knowledge to scaffold L2-based learning. However, while they acknowledged differences between L1 and L2 epistemic frameworks, not all of them fully grasped the potential and value of translanguaging pedagogy for transknowledging and the development of a glocal knowledge system. A glocal epistemic framework emerges when students integrate knowledge systems across local and global scopes of academics through EMI learning. For instance, Ming flexibly incorporated L1 everyday and academic language into her teaching, allowing students to engage with multiple linguistic-epistemic systems. However, she perceived this as a necessary compromise due to her and her students’ limited English proficiency, urging students to watch an English video to learn the “standard” English version of the same topic. In contrast, Zhao demonstrated greater awareness of the pedagogical value of recognising diverse epistemic systems, leveraging transknowledging through “care for words” (Heugh this issue) and advocating linguistic citizenship within Chinese academia. This highlights a key concern: the pervasive and corrosive ideology of English native-speakerism in EMI risks reducing translanguaging to a mere pedagogical tool for attaining “standard” English, rather than legitimising multilingual users’ linguistic and knowledge repertoires.

Nonetheless, the role of translangugaing in EMI is shaped by multiple factors, including institutional policies of EMI, lecturers’ pedagogical beliefs, and teacher identities (Ou and Gu 2024). Providing space for different “named” languages in EMI does not automatically empower L1 (Canagarajah 2022; Li 2022). It is crucial to raise both teachers’ and students’ awareness of the raciolinguistic ideologies underlying EMI to achieve greater equity across languages, cultures, and knowledge systems (Kubota 2021). Ming’s case illustrates how the ideology of “standard” English might discourage students from expressing themselves freely, reinforcing raciolinguistic norms (Li 2022). A more balanced ideological perspective – one that equally values L1 and L2 knowledge systems – would allow EMI teachers to maximise the scaffolding potential of students’ L1 knowledge systems.

The findings suggest an emerging epistemic ecology in STEM classrooms, where teachers and students actively draw on existing knowledge in a co-constructive process, and where bilingual teachers’ and students’ epistemic diversity is recognised as an asset. Translanguaging is not simply an additive of different languages (Li 2022); it entails reconstituting and restructuring power relations between languages, knowledge systems, and pedagogic ideologies. For instance, in Zhao’s class, the use of Chinese not only supported students’ comprehension but also empowered students to challenge English monolingualism in content knowledge construction, fostering a more equitable perception of their L1 epistemic systems. Researchers theorise this as delinking from the colonial praxis of knowing (Song and Lin 2020) and relinking with new meanings, possibilities, and alternatives (Canagarajah 2022). Relinking is a sociopolitical process requiring continuous reflection on “dominant ideologies, and established discourses” that shape not only the dominant epistemologies but also “the representation of resistant epistemologies” (Canagarajah 2022: 2). As observed in this study, STEM teachers often used translanguaging as a bridge to L2 and, sometimes a “standard” L2 knowledge rather than as a means to establish an alternative knowledge system. While this does not harm, moving beyond clear divides and boundaries of knowledge and epistemic systems could enable multilingual teachers and students to co-construct new knowledge systems, integrating diverse cultural and intellectual traditions on an equitable basis. The empirical findings of this study echo Canagarajah’s (2022: 5) observation that “relinking and delinking will therefore be iterative and ongoing, involving constant self-questioning and recalibration, as new alternatives are imagined.” EMI, with its flexibility in adopting translanguaging practices, offers a productive space for educators to explore multiple epistemic values, subjectivities, pedagogical approaches, and affective engagements within a broader academic community.

7 Conclusions

This study expands the ongoing transknowledging dialogue in EMI research (e.g. Song 2023) by moving beyond language flexibility to investigate teachers’ real-life practices and the complex interplay of languages, semiotics, and knowledge systems in EMI classrooms. The findings identified diverse translanguaging pedagogical strategies used by STEM teachers with varying linguistic repertoires and EMI beliefs, eliciting various forms of transknowledging processes. These include (1) establishing cognitive linkages between content knowledge across languages (English and Chinese), registers (academic and everyday language), and modalities (visuals and body movements); (2) developing the flow of content knowledge development and language learning through dialogical translanguaging, as well as (3) decolonising EMI curricula by integrating local languages and epistemic systems. In these classrooms, teachers and students drew on L1 knowledge for teaching/learning, recognising the epistemic advantages of bilingualism. However, the findings suggest the need for greater support in moving beyond rigid epistemic boundaries to establish alternative, glocally grounded knowledge systems.

These insights have important implications for EMI teachers, curriculum developers, and policymakers. Teachers who fully leveraged their linguistic repertoires fostered greater interactivity and dialogue in their teaching, highlighting the role of translanguaging in meaning-making and student engagement. Moreover, the multi-case analysis reveals a “translanguaging dilemma”: in EMI classrooms where L1 Chinese dominates, students may have fewer opportunities to develop L2 academic proficiency; conversely, in EMI settings without a shared L1, students’ linguistic resources remain underutilised in meaning-making. Therefore, EMI teacher support should be tailored to the linguistic and cultural backgrounds of both teachers and students, addressing their specific challenges and needs.

This study examined four cases of knowledge (co)construction in EMI-STEM classrooms at a Mainland Chinese university. Future research should extend this exploration across different STEM disciplines and investigate students’ learning processes and outcomes. A quantitative approach could provide a more direct representation between translanguaging and content as well as the language learning effect, laying an empirical foundation for further research. Additionally, longitudinal ethnographic studies could capture the evolving nature of language practices, interactions, meaning-making, and knowledge construction, offering deeper insights into the factors shaping translanguaging in EMI contexts.

Funding source: General Research Fund by Research Grant Council, Hong Kong

Award Identifier / Grant number: 18621622

Acknowledgement

We thank General Research Fund (GRF) by Research Grant Council, Hong Kong (Project No.: 18621622) for funding this research.

-

Conflict of interest: We have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

Alhasnawi, Sami. 2021. Teachers’ beliefs and practices with respect to translanguaging university mathematics in Iraq. Linguistics and Education 63. 100930. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2021.100930.Suche in Google Scholar

Block, David & Balbina Moncada-Comas. 2022. English-medium instruction in higher education and the ELT gaze: STEM lecturers’ self-positioning as NOT English language teachers. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 25(2). 401–417. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2019.1689917.Suche in Google Scholar

Canagarajah, Suresh. 2018. Translingual practice as spatial repertoires: Expanding the paradigm beyond structuralist orientations. Applied Linguistics 39(1). 31–54. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amx041.Suche in Google Scholar

Canagarajah, Suresh. 2022. Challenges in decolonizing linguistics: The politics of enregisterment and the divergent uptakes of translingualism. Educational Linguistics 1(1). 25–55. https://doi.org/10.1515/eduling-2021-0005.Suche in Google Scholar

Chen, Kuan-Hsing. 2010. Asia as method: Toward deimperialization. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.10.2307/j.ctv11smwwjSuche in Google Scholar

Copland, Fiona & Angela Creese. 2015. Linguistic ethnography: Collecting, analysing and presenting data. London: Sage.10.4135/9781473910607Suche in Google Scholar

de Los Ríos, Cati V. & Kate Seltzer. 2017. Translanguaging, coloniality, and English classrooms: An exploration of two bicoastal urban classrooms. Research in the Teaching of English 52(1). 55–76. https://doi.org/10.58680/rte201729200.Suche in Google Scholar

Fang, Fan & Yang Liu. 2020. ‘Using all English is not always meaningful’: Stakeholders’ perspectives on the use of and attitudes towards translanguaging at a Chinese university. Lingua 247. 102959. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2020.102959.Suche in Google Scholar

García, Ofelia, Nelson Flores, Kate Seltzer, Wei Li, Ricardo Otheguy & Jonathan Rosa. 2021. Rejecting abyssal thinking in the language and education of racialized bilinguals: A manifesto. Critical Inquiry in Language Studies 18(3). 203–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427587.2021.1935957.Suche in Google Scholar

García, Ofelia & Wei Li. 2014. Translanguaging: Language, bilingualism, and education. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.10.1057/9781137385765_4Suche in Google Scholar

Gu, Mingyue Michelle & Chi-kin John Lee. 2019. “They lost internationalization in pursuit of internationalization”: Students’ language practices and identity construction in a cross-disciplinary EMI program in a university in China. Higher Education 78. 389–405. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-018-0342-2.Suche in Google Scholar

Gu, Mingyue Michelle, Chi-kin John Lee & Tan Jin. 2023. A translanguaging and trans-semiotizing perspective on subject teachers’ linguistic and pedagogical practices in EMI programme. Applied Linguistics Review 14(6). 1589–1615. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2022-0036.Suche in Google Scholar

Gu, Mingyue Michelle, Zhen Jennie Li & Lianjiang Jiang. 2024. Navigating the instructional settings of EMI: A spatial perspective on university teachers’ experiences. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 45(2). 564–578. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2021.1914064.Suche in Google Scholar

Heugh, Kathleen. 2021. Southern multilingualism, translanguaging and transknowledging in inclusive and sustainable education. In Philip Harding-Esch & Hywel Coleman (eds.), Language and the sustainable development goals, 37–47. London: British Council.Suche in Google Scholar

Heugh, Kathleen. 2025. Southern multilingualism and translanguaging: Towards restoring plurality in applied linguistics and education. Applied Linguistics Review. 1–27.10.1002/9781405198431.wbeal0782.pub2Suche in Google Scholar

Jablonkai, Reka R. & Jie Hou. 2021. English medium of instruction in Chinese higher education: A systematic mapping review of empirical research. Applied Linguistics Review 1–30, https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2021-0179.Suche in Google Scholar

Kubota, Ryuko. 2021. Critical antiracist pedagogy in ELT. ELT Journal 75(3). 237–246. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccab015.Suche in Google Scholar

Kuteeva, Maria. 2020. Revisiting the ‘E’in EMI: Students’ perceptions of standard English, lingua franca and translingual practices. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 23(3). 287–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2019.1637395.Suche in Google Scholar

Lemke, Jay L. 1990. Talking science: Language, learning, and values. Norwood, N.J.: Ablex Pub Corp.Suche in Google Scholar

Lemke, Jay L. & Angel M. Y. Lin. 2022. Translanguaging and flows: Towards an alternative conceptual model. Educational Linguistics 1(1). 134–151. https://doi.org/10.1515/eduling-2022-0001.Suche in Google Scholar

Li, Wei. 2018. Translanguaging as a practical theory of language. Applied Linguistics 39(1). 9–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amx039.Suche in Google Scholar

Li, Wei. 2022. Translanguaging as a political stance: Implications for English language education. ELT Journal 76(2). 172–182. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccab083.Suche in Google Scholar

Lin, Angel M. Y. 2019. Theories of trans/languaging and trans-semiotizing: Implications for content-based education classrooms. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 22(1). 5–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2018.1515175.Suche in Google Scholar

Lin, Angel M. Y. & Peichang He. 2017. Translanguaging as dynamic activity flows in CLIL classrooms. Journal of Language, Identity and Education 16(4). 228–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348458.2017.1328283.Suche in Google Scholar

Lin, Angel M. Y., Yanming (Amy) Wu & Jay L. Lemke. 2020. ‘It takes a village to research a village’: Conversations between Angel Lin and Jay Lemke on contemporary issues in translanguaging. In Sunny Man Chu Lau & Saskia Van Viegen (eds.), Plurilingual pedagogies, 47–74. Cham: Springer International Publishing.10.1007/978-3-030-36983-5_3Suche in Google Scholar

Lin, Angel M. Y. & Yuen Yi Lo. 2017. Trans/languaging and the triadic dialogue in content and language integrated learning (CLIL) classrooms. Language and Education 31(1). 26–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2016.1230125.Suche in Google Scholar

Mbirimi-Hungwe, Vimbai. 2016. Translanguaging as a strategy for group work: Summary writing as a measure for reading comprehension among university students. Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies 34(3). 241–249. https://doi.org/10.2989/16073614.2016.1250352.Suche in Google Scholar

Mbirimi-Hungwe, Vimbai. 2021. An insight into South African multilingual students’ perceptions about using translanguaging during group discussion. Applied Linguistics 42(2). 252–268. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amaa012.Suche in Google Scholar

Osborne, Sam, Karina Lester, Katrina Tjitayi, Rueben Burton & Makinti Minutjukur. 2020. Red Dirt Thinking on first language and culturally responsive pedagogies in Aṉangu schools. Rural Society 29(3). 204–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/10371656.2020.1842597.Suche in Google Scholar

Ou, Wanyu Amy & Mingyue Michelle Gu. 2022. Competence beyond language: Translanguaging and spatial repertoire in teacher-student interaction in a music classroom in an international Chinese University. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 25(8). 2741–2758. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2021.1949261.Suche in Google Scholar

Ou, Wanyu Amy & Mingyue Michelle Gu. 2024. Teacher professional identities and their impacts on translanguaging pedagogies in a STEM EMI classroom context in China: A nexus analysis. Language and Education 38(1). 42–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2023.2244915.Suche in Google Scholar

Ou, Wanyu Amy, Mingyue Michelle Gu & Chi-kin John Lee. 2024. Learning and communication in online international higher education in Hong Kong: ICT-mediated translanguaging competence and virtually translocal identity. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 45(5). 1732–1745. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2021.2021210.Suche in Google Scholar

Paulsrud, BethAnne, Zhongfeng Tian & Jeanette Toth (eds.), 2021. English-medium instruction and translanguaging. Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.10.2307/jj.22730560Suche in Google Scholar

Pun, Jack & Ernesto Macaro. 2019. The effect of first and second language use on question types in English medium instruction science classrooms in Hong Kong. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 22(1). 64–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2018.1510368.Suche in Google Scholar

Rafi, Abu Saleh Mohammad & Anne-Marie Morgan. 2024. A pedagogical perspective on the connection between translingual practices and transcultural dispositions in an Anthropology classroom in Bangladesh. International Journal of Multilingualism 21(1). 236–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2022.2026360.Suche in Google Scholar

Rahman, Mohammad Mosiur & Manjet Kaur Mehar Singh. 2022. English Medium university STEM teachers’ and students’ ideologies in constructing content knowledge through translanguaging. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 25(7). 2435–2453. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2021.1915950.Suche in Google Scholar

Roothooft, Hanne. 2022. Spanish lecturers’ beliefs about English medium instruction: STEM versus humanities. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 25(2). 627–640. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2019.1707768.Suche in Google Scholar

Rose, Heath, Kari Sahan & Sihan Zhou. 2022. Global English medium instruction: Perspectives at the crossroads of global englishes and EMI. Asian Englishes 24(2). 160–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/13488678.2022.2056794.Suche in Google Scholar

Sahan, Kari, Nicola Galloway & Jim McKinley. 2025. English-only’ English medium instruction: Mixed views in Thai and Vietnamese higher education. Language Teaching Research 29(2). 657–676. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688211072632.Suche in Google Scholar

Santos, Boaventura de Sousa. 2014. Epistemologies of the South: Justice against epistemicide. London: Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

Simungala, Gabriel & Hambaba Jimaima. 2021. Multilingual realities of language contact at the University of Zambia. Journal of Asian and African Studies 56(7). 1644–1657. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021909620980038.Suche in Google Scholar

Song, Yang. 2023. “Does Chinese philosophy count as philosophy?”: Decolonial awareness and practices in international English medium instruction programs. Higher Education 85. 437–453. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-022-00842-8.Suche in Google Scholar

Song, Yang & Angel M. Y. Lin. 2020. Translingual practices at a Shanghai university. World Englishes 39(2). 249–262. https://doi.org/10.1111/weng.12458.Suche in Google Scholar

Stake, Robert E. 2006. Multiple case study analysis. New York: The Guilford Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Stroud, Christopher. 2001. African mother-tongue programmes and the politics of language: Linguistic citizenship versus linguistic human rights. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 22(4). 339–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434630108666440.Suche in Google Scholar

Tsou, Wenli & Will Baker. 2021. English-medium instruction translanguaging practices in Asia. Singapore: Springer.10.1007/978-981-16-3001-9Suche in Google Scholar

Wang, Weihong & Xiao Lan Curdt-Christiansen. 2019. Translanguaging in a Chinese-English bilingual education programme: A university-classroom ethnography. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 22(3). 322–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2018.1526254.Suche in Google Scholar

Wu, Yanming (Amy) & Angel M. Y. Lin. 2019. Translanguaging and trans-semiotising in a CLIL biology class in Hong Kong: Whole-body sense-making in the flow of knowledge co-making. Classroom Discourse 10(3–4). 252–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/19463014.2019.1629322.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.