Abstract

This paper explores diasporic identities enacted in the semiotic landscapes of Chinese restaurants. Informed by a materialist theory of signs and space, it presents an ethnography of three independent Chinese restaurants in Liverpool, UK. Geosemiotic analysis reveals that the three restaurants take three different approaches to the semiotic enactment of Chinese food(space): nominal display of Chineseness as family heritage, flexible assemblage of global Chineseness, and ethnocentric reproduction of nationalist Chineseness. We interpret these differences as acts of cultural distinctiveness, suggesting that the observed variation in the semiotic construction stems from the restaurateurs’ distinctive perceptions of Chinese food based on their varied diasporic histories and trajectories as well as different self-positionings vis-à-vis the UK and Greater China. The semiotic landscapes of Chinese restaurants thus showcase the heterogeneity of Chinese cuisine and diasporic identity, challenging homogeneous understandings of Chinese food and the Chinese diaspora. The study also highlights the semiotic complexes of ethnic restaurants, revealing signs as a covert mechanism for self-positioning, intra-ethnic differentiation, and customer selection.

1 Introduction

Ethnic restaurants play a significant role in diasporic communities, serving as vital cultural and social spaces. Research across multiple disciplines, including sociology, anthropology, and business studies, has demonstrated that studying ethnic restaurants offers important insights into not only food and culture (Lu and Fine 1995), but also migration, globalization, transnationalism, and diasporic identity (Abbots et al. 2016; Mankekar 2002; Sutton 2005), contributing to our understanding of ‘how the globalized movement of people, objects, narratives, and ideas is experienced and negotiated’ (Abbots et al. 2016: 115). For restaurateurs, in particular, these spaces function as both repositories of memories from the homeland and sites for negotiating identity and belonging in the host society.

One productive approach to studying diasporic identity is through semiotic analysis of ethnic restaurants. This involves exploring how semiotic landscapes, broadly understood as multiple meaning-making resources, including language, images, sounds, music, décor, space, etc. (Jaworski and Thurlow 2010; Shohamy 2015), are deployed in constructing a socially meaningful place which, in turn, shapes interactions and activities within them. An emerging body of research has examined the semiotic landscapes of ethnic restaurants in diverse contexts, such as Vietnamese Pho restaurants in Canada (Tran 2019), Chinese Wenzhou restaurants in Paris’s Chinatown (Lipovsky and Wang 2019), Thai restaurants in Germany (Androutsopoulos and Chowchong 2021), Chinese restaurants in ethnic enclaves in Australia (Xu and Wang 2021), Italian restaurants in the UK (Guzzo and Gallo 2019), and Korean restaurants in different cities worldwide (Lee 2022). These studies show how examining the semiotics of ethnic restaurants can enhance our understanding of national and ethnic identity, and the changing demography of diasporic communities.

Contributing to this line of inquiry, this study examines three independent Chinese restaurants in Liverpool, UK. While previous research has largely focused on Chinese ethnic restaurants in Chinatowns and other ethnic enclaves, emphasizing the construction of Chinese identity (Lipovsky and Wang 2019) and nostalgia (Yao 2020), this study highlights the diversity of diasporic identities and intra-ethnic differentiation. Informed by ethnographic work, our study delves into the multiple and varied ways restaurants function as integral parts of the life stories and diasporic histories of the restaurateurs. We show that the three Chinese restaurateurs adopt three different approaches to the semiotic enactment of Chineseness, which we explain through the notion of cultural distinctiveness, defined as the perceived, imagined and constructed differences that set one apart from others operating at both individual and group levels. We also draw upon the understanding that diasporic identity is not homogeneous; instead, it is dynamic, multiple, and shaped by varied orientations towards host and home societies, towards the past and present (Canagarajah and Silberstein 2012; Faist 2010; Woldemariam and Lanza 2015) and towards homogeneity and distinctiveness, as we argue in the paper. We draw upon observations and interviews to trace the itineraries (Scollon 2008) of signs in the restaurants, including outdoor signage, menus, deco, music, food, etc., taking a material ethnography approach which examines signs as ‘the material, symbolic and interactional artifacts of a sociolinguistics of mobility’ (Blommaert 2013b; Stroud and Mpendukana 2009: 363). In presenting a material ethnography of Chinese restaurants, we show how Chinese restaurants, as spatial, semiotic and cultural constructs, are shaped by and embody different approaches to cultural distinctiveness, as well as revealing how semiotic complexes can provide insights into the diversity and dynamics of the Chinese diasporic identity.

Specifically, this paper addresses the following questions: How do languages and other semiotic resources mediate the construction of Chinese restaurants? In what ways does the semiotic construction of Chinese restaurants reflect, as well as being shaped by, the restaurateur’s diasporic positionings and orientations to Chinese food? Below, we first provide a brief history of Chinese restaurants in the UK, followed by a discussion of the key theoretical and analytical notions we draw from, cultural distinctiveness and materialist theory of signs (Blommaert 2013b). We then introduce the research sites and methodology before presenting a semiotic analysis of the three restaurants, which reveals three distinctive ways of representing Chinese food, namely, nominal display of Chineseness as family heritage, flexible assemblage of global Chineseness, and ethnocentric reproduction of nationalist Chineseness. The paper concludes by discussing how these varied semiotic constructions of Chinese food(space) are mediated by the restaurateurs’ varied diasporic identities and self-positionings.

2 Chinese diaspora and Chinese restaurants in the UK: a brief history

The emergence of Chinese catering businesses in the recent history of UK was driven by the growing demand for ethnic food in post-World War II Britian (Song 2015: 66). While the early presence of Chinese in the UK can be traced to the 1880s, when Chinese people worked as seamen in port cities such as Liverpool and London, the emergence of relatively large number of Chinese catering businesses occurred after World War II in the 1950s and 1960s which were opened by Cantonese and Hokkien-speaking migrants who were escaping from deteriorating economic conditions in rural Hong Kong (Chau and Yu 2001). In 1985, about 90 % Chinese in the UK worked in the catering industry, with the percentage reduced to over 50 % in 1991 (Chau and Yu 2001: 109) as younger generations sought other professions.

This nature of early Chinese migration to the UK, that is, to work in the catering industry, has affected the way the Chinese community functions in British society. Chinese in the UK are both ‘geographically divided and socially divided’ (Chau and Yu 2001: 114–115), challenging conceptualizations such as ‘ethnic enclaves’ (Barabantseva 2015). Unlike in the US or Australia, where large numbers of Chinese migrants, initially driven by the Gold Rush, often reside in ethnic neighborhoods, or ethnic enclaves, Chinese in the UK were and remain geographically dispersed: There is no one British city or area where Chinese residents are the majority, and there are many instances which one grows up in the UK as the only Chinese person in the whole neighborhood (Song 2015). This geographically dispersedly distribution of the Chinese population helped avoid business competition as menus of these Chinese takeaways tend to be similar and easily replicable. Thus, Chinese restaurateurs tend to be the only Chinese residents in a neighborhood or place, serving local English-speaking customers with food adapted to British taste, such as sweet and sour Chinese dishes, and fish and chips. Another business strategy is to open Chinese businesses in the same geographical area, such as Chinatowns. In the competition to attract customers, it is important that businesses position themselves differently, usually by cooking a popular style of Chinese dish that distinguishes one restaurant from another (Chau and Yu 2001; Lu and Fine 1995). As we will show later in our analysis, this need to offer something different is one factor contributing to restauranteurs’ enactment of cultural distinctiveness.

Existing studies into the Chinese restaurants in the UK are limited and focus mostly on the early waves of Chinese migrants and Chinese restaurants. The available literature shows a similar dark picture: Chinese catering businesses are sites of exploitation, intra-ethnic conflicts, racial discrimination, hate crime, social exclusion, mental health issues (Adamson et al. 2009; Chau and Yu 2001; Chaudhry and Crick 2004; Lou and Zhu 2020; Parker 1994). Due to the association of Chinese people with Chinese food, they tend to be racialized and excluded from the mainstream society as ‘dispensable commodities’ (Chau and Yu 2001: 117); they are also excluded from their own ethnic groups due to intra-ethnic competition in the same catering industry – leading to ‘double social exclusion’ (Chau and Yu 2001: 120).

This study contributes to the existing literature by documenting the current state of Chinese restaurants in the UK, where the second or third generation of British Chinese, as well as new waves of Chinese migrants arriving since the 1990s from mainland China, are working in the Chinese food catering businesses. As we will explain below, the combined theoretical perspectives of semiotic complexes and cultural distinctiveness are pivotal in revealing the diversity and dynamics of Chinese restaurants in the UK.

3 Cultural distinctiveness and semiotic complexes

As mentioned earlier, differentiation is a key business strategy among Chinese restaurants in the UK (Chau and Yu 2001; Lu and Fine 1995). However, the significance of ‘being different’ goes far beyond market positioning. It is also a central concern in the construction of both individual and group identities. Building on previous work by social psychologists on social identity (e.g., Vignoles et al. 2000) and sociolinguists and applied linguists on identity in contexts of mobility (e.g., Zhu 2017), this study brings in the notion of cultural distinctiveness. We approach the notion as both manifested in and shaped by semiotic complexes simultaneously and use it as a lens to understand restaurant owners’ construction of diasporic identities and business positioning.

The argument that distinctiveness, i.e., to be unique or different, is a fundamental human need is well established in social psychology. Brewer (1991), following uniqueness theories proposed by Snyder and Fromkin (1980), argues that this need co-exists with the need for assimilation. Being different and at the same time being similar to and validated by others, despite being paradoxical, is necessary to an individual’s notion of self. Vignoles et al. (2000) similarly recognize that the desire for distinctiveness (termed as the distinctiveness principle) operates at both individual and group levels. They argue that individual identity may derive from a combination of several multiple group identifications, and meaningful group affiliation can only happen if the group is perceived as distinct from others. This even applies to the most inclusive and broad group identities such as ‘citizen of the world’. These perspectives raise an important point about the links between group and individual distinctiveness – both are integral to the construction of identity, which is always defined in relation to others. Vignoles et al. (2000: 341) align with a social constructivist approach towards identity and argue that identity is ‘not constructed solely within the individual but emerges through an interaction of process of perception, cognition, and communication’. Therefore, it is the projection of distinctiveness in relation to others, rather than simply acquiring a sense of distinctiveness for oneself, that shapes identity.

These views resonate strongly with applied linguistic and sociolinguistic approaches to migration studies in the last two decades, which see identities entailing the juxtapositions between the self and the other, the personal and the social, stability and situated accomplishment, and product and process (Zhu 2017). Individuals manage their group memberships through a range of possibilities. Relevant to the theme of our study are the practice of heritaging (e.g., Blommaert 2013a) and traditionalization (e.g., Bauman 1992; Bucholtz and Hall 2005) where participants construct certain practices as traditions. De Fina (2013) shows how corporations employ heritaging, that is, emphasizing common cultural background and “authentic” customs and values, to market their products. Ben-Rafael (2013: 847) discusses that ‘collective identity building’ among diasporas depends on the degree of commitment to and solidarity people feel towards the same group (we as opposed to they) as well as on their use of shared semiotic repertoires. Even when individual interpretations may diverge, these practices work to ‘singularize’ the collective as a whole. These studies show that identities are not only constructed in the moment but also shaped through one’s strategic emphasis and choice, drawing on perceived or imagined (cultural) distinctiveness.

As a term, cultural distinctiveness has been loosely used in consumer research, referring to, for example, significant differences between one’s current cultural environment and the culture of origin (e.g., Torelli et al. 2017). Their findings reveal to what extent closeness or rivalries between groups could influence one’s cultural consumption and how cultural distinctiveness can be manipulated for commercial benefits. However, what constitutes cultural distinctiveness has typically been treated as something static or normative, building on stereotypical understanding of what a culture is or is not. In contrast, Jerry Won Lee (2022) contains the first attempt to investigate how cultural distinctiveness such as Koreaness can be located and (re)signified at a global scale through translingualism. Following Agha (2006), he situates linguistic and cultural encounters as semiotic encounters. One example is while Italian and French signage in a Korean town may seem to hold little apparent significance, their presence in Korean communities contrasts with Korean signs and therefore paradoxically contributes to the making of Koreaness. He further proposes the notion of semiotic precarity, a condition in which previously unremarkable cultural differences become remarkable and associations between a culture and its ‘typical’ semiotic works are destabilized. For him, semiotic precarity creates a moment to reexamine these associations and to consider why. An example of semiotic precarity is when a non-Korean’s rendering of a Korean script on signage prompts reflection on what the Korean script is ‘supposed’ to look like. He explains that efforts by cultural groups to differentiate themselves from one another through semiotic work are driven by a range of intentions from ‘innocuous celebrations of ethnic heritage to ritualistic exhibitions of ethnic exceptionalism’ (Front matter). Further along this line of investigation, Zhu (2026) examines Google Doodles concerning Chinese New Year/Lunar New Year, and explores the sociocultural, political and ideological factors shaping cultural distinctiveness and the politics of representation.

Drawing on these theoretical perspectives and taking a social constructivist approach to culture and identity, we define the notion of cultural distinctiveness in this study as the perceived, imagined and constructed differences that set one individual/group apart from others. It is relational, defined not in isolation but through contrast and comparison with other groups; it is semiotically represented, projected and recognized through semiotic complexes; it is materially grounded, in line with a materialist theory of signs which sees “as material forces subject to and reflective of conditions of production and patterns of distribution, and as constructive of social reality, as real social agents having real effects in social life (Blommaert 2013b: 38; see also Stroud and Mpendukana 2009: 363); it is historically situated and contingent, as signs emerge ‘from the assemblage of historical events, memories, and narratives reflecting these events, often handed down over generations’ (Lazar 2022; Kroon 2021: 275), and ‘comprises traces and sedimentations of identities and social practices’ (Stroud and Mpendukana 2012: 150); and finally, it can be politically conditioned, reflecting and reproducing different ideological stances and self-positionings. Seeing differences as perceived, imagined and constructed highlights the multiple dimensions through which cultural distinctiveness emerges: from contrast and comparison (perceived) to symbolic association (imagined), and while emphasizing that such differences are socially produced, maintained and reproduced through semiotic practices that define “us” versus “them” (constructed).

Before drawing upon the above concepts to analyze the three Chinese restaurants, we will next introduce our research site and methodology.

4 Research site and methodology

We conducted ethnographic fieldwork for 3 months from June to Aug 2023 in Liverpool, UK after gaining ethics approval at the first author’s institution. Liverpool is a port city in northwest England, located on the Mersey Estuary near the Irish Sea. It was home to Europe’s oldest Chinese community and oldest Chinatown dating back to the 1880s (Chau and Yu 2001). Today, Liverpool’s residents are from multiple ethnic backgrounds. The most recent national consensus in 2021 shows that 23 % of Liverpool residents are non-White. Its largest minority ethnic group is African, accounting for 2.6 % of Liverpool’s total population, followed by Chinese, who make up 1.8 % of all residents, totaling 8,841 in number (Liverpool City Council 2021).

Guided by our research focus on Chinese restaurants, the research team first searched on TripAdvisor, which listed 146 Chinese restaurants in Liverpool. We chose to focus on high streets around the Chinatown area and the city centre nearby due to the sizable number of Chinese restaurants there. We visited all Chinese restaurants in this area to explain the research project and seek consent. We did not purposefully include or exclude any Chinese restaurant when seeking consent. Participants were chosen based on their availability and willingness to participate. At the time of research, there were five Chinese restaurants in total inside Chinatown. Like most Chinatowns in the UK, Liverpool’s Chinatown is an area of commerce and does not constitute an ethnic enclave where large numbers of Chinese people live, like New York’s Chinatown (Song 2015: 67). Besides, Liverpool’s Chinatown has been in decline in recent years and businesses there struggled to survive and there was no attempt to revitalize Chinatown (The Economist 2018). On several visits during our fieldwork, Chinatown was empty. Many have opening hours from the evening till after midnight, catering to late-night drinking. Streets around Chinatown tend to be busier, with many different types of businesses lined up one after another, including restaurants of multiple culinary styles, such as Chinese, Korean, English, Vietnamese, and Italian, as well as pharmacies, convenience stores, and electronics shops.

In total, three restaurateurs gave consent for research, hence the three restaurants in the present research. Table 1 below shows their profiles. The three restaurants are located near Chinatown and are within less than 3 min’ walk from each other. They are independent medium-sized businesses with similar price tags. The owners told us during fieldwork that it was the low season now (June to Aug 2023) as many people would have gone overseas for summer holidays. In other words, their main customers are local residents as opposed to tourists to the city.

The profiles of the three restaurants.

| Owner(s) background | Business history | Waiting staff composition | Main customers | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Restaurant 1 | 2nd generation British Chinese and her Malaysian Chinese husband in their early 60s | Over 50 years | 2 waiting staff: 1 local English and 1 British Chinese (the owner) | Mainly English-speaking customers |

| Restaurant 2 | 3rd generation British Chinese in their 30s | Less than 10 years | 3 local English waiting staff | Mainly English-speaking customers |

| Restaurant 3 | 1st generation migrant from mainland China in their 50s | Almost 20 years | 3 waiting staff, who are 1st and 2nd generation migrants from mainland China | Mixture of English-speaking and Chinese-speaking customers |

Data were collected using multiple methods, including regular visits to and observations at these businesses, field notes, interviews with waiting staff and owners, photos, and business websites online. Interviews were conducted in the language preferred by the interviewees. English was used in Restaurants 1 and 2, and Chinese was used in Restaurant 3. The interview data were presented in the original language used during interviews and, where relevant, accompanied by English translation by the authors. All names (person and restaurant) mentioned below are pseudonyms. It is the research ethical requirements to protect the identity of the participants. Due to the size of the three restaurants, disclosing the full names of the restaurants could easily lead to the identification of the restaurateurs/working staff interviewed. Thus, for research ethics reasons, where images are used for analysis, details that could lead to the identification of the restaurant and hence our participants working in there are blurred. Where blurred details are relevant for analysis, we have provided descriptions of such images in texts without compromising anonymity. In analyzing the signs, we conducted geosemiotic analysis (Scollon and Scollon 2003), that is, ‘the study of the social meaning of the material placement of signs and discourses and of our actions in the material world’ (Scollon and Scollon 2003: 2), including place semiotics (the meaning system of spatial organization), visual semiotics (the multimodal meaning-making resources used in visual representation and interpretation), and interaction order (social relationships). This geosemiotic analysis is complemented by ethnographic interviews and observational fieldnotes to explore the ‘different historicities’ and ‘therefore fundamentally different indexical loads’ (Blommaert 2013b: 11) of semiotic resources. As we will explain, the three cases illustrate three distinctive ways of enacting Chineseness, reflecting the restaurateurs’ different personal and migration histories as well as self-positioning.

5 Findings

5.1 Restaurant 1

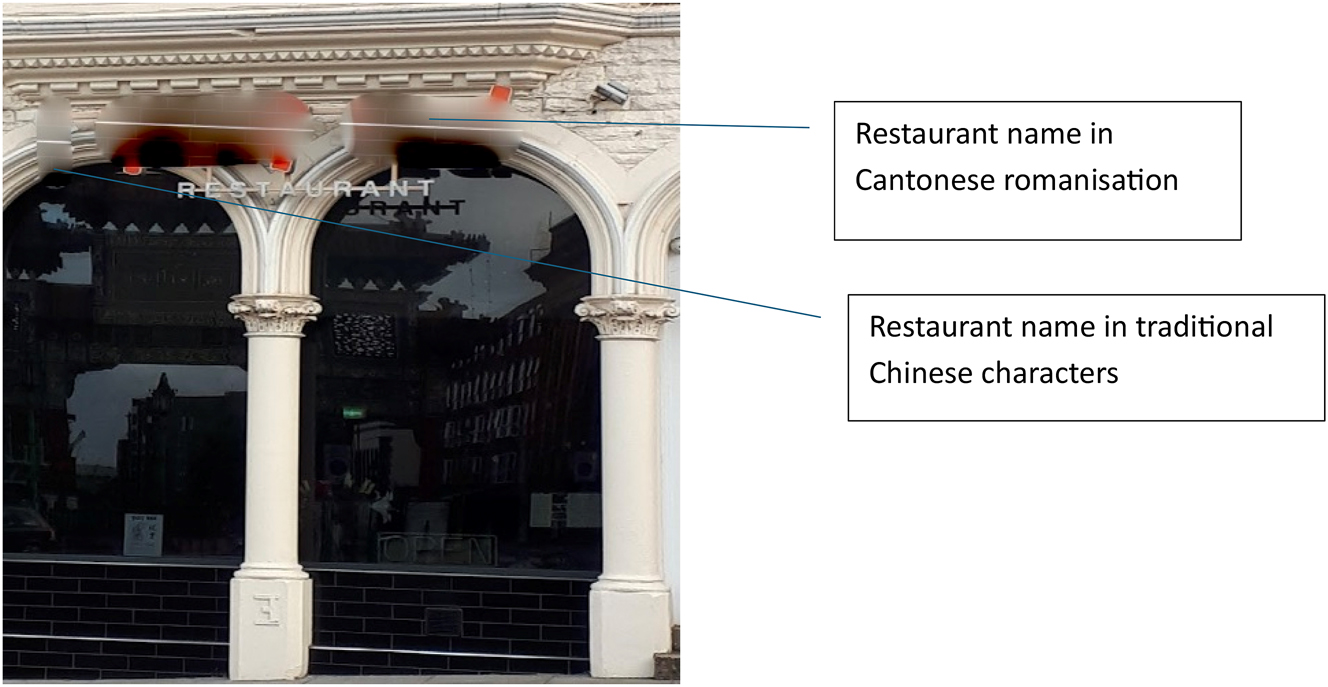

The first restaurant’ semiotic landscapes are characterized by nominal display of Chineseness, meaning that there are limited signs used to index Chineseness, and Chineseness can even be undesirable in practice. The façade of the restaurant is not easily recognizable as a Chinese restaurant. Located just around the corner of a crossroad overlooking the arch of Chinatown, the façade contains minimal signage (see Figure 1), with the name of the restaurant displayed in the top in three segments. The most visibly salient segment is the two words in Cantonese romanization. Displayed in large capitalized red letters in the top center position. The size, color, and positioning of the two words mark them out as the most visible part of the restaurant name. Right beneath it is another segment of its name, displayed in English ‘restaurant’ in small capital letters in white – the same color as the wall. Upon closer examination, there is another segment of the restaurant name displayed in traditional Chinese characters. But it is easily overlooked due to its size and color: it is placed on the left in a small white font, displayed from top to down, and in the same color as the wall. From a visual semiotics perspective (Scollon and Scollon 2003), the design of the restaurant name foregrounds its Cantonese romanization name through its font size and color, indicating that its intended viewers are from English-speaking backgrounds, as the Chinese characters have relatively little visibility due to size and color.

Facade of restaurant 1.

The restaurant name reflects family heritage, as the owners explained to us, which was also briefly explained on their restaurant’s website. The owners were a couple who inherited the business from the wife’s father. The wife explained that ‘My dad used to work as a chef at a high-end restaurant in Hong Kong with this same name, so he kept it when he opened his own restaurant in Liverpool, and it’s always been like this since’. The sign is thus a product of re-semiotization and recontextualization (Iedema 2001), with a sign originally written in traditional Chinese characters in Hong Kong being reinscribed into Cantonese romanization for English-speaking customers in the UK, projecting the restaurant’s distinctive positioning. The sign acquires new indexical meanings in this context of migration, highlighting her dad’s professionalism and prestige as a former top-end restaurant chef, and pointing backwards to its original context as a nostalgic display of ‘home’. But such indexical meanings would only be noticeable for people familiar with the family’s migration history; other visitors may simply read it as a token of Chineseness. The salient display of Cantonese romanization thus has the effect of demarcating the space, indicating that its intended recipients are English-speakers. This is exactly the case based on our observations. We did not see any Chinese customers during any of our visits, a point we will return to later.

The Cantonese romanization and traditional Chinese characters on the façade turn out to be the only signs indexical of Chineseness in the whole of the restaurant. The absence of Chineseness is immediately perceivable upon entering the restaurant, in contrast to the overt displays of Chinese cultural elements often found in Chinese restaurants overseas (e.g., Yao 2020). The only Chinese elements are located at the very back of the restaurant, near the checkout desk/wine shelves, where an arch draped with small bamboo trees and small red lanterns can be seen. Due to the layout of the space, these cultural elements are easily missed unless one pays close attention to the back section of the restaurant. When asked about the interior décor, the owners explained that they hired local English decorators for the interior design, as they preferred a minimalist style. As a result, Chineseness is absent in the restaurant’s overall aesthetic, with Chineseness only visible in the ‘backstage’ (Scollon and Scollon 2003).

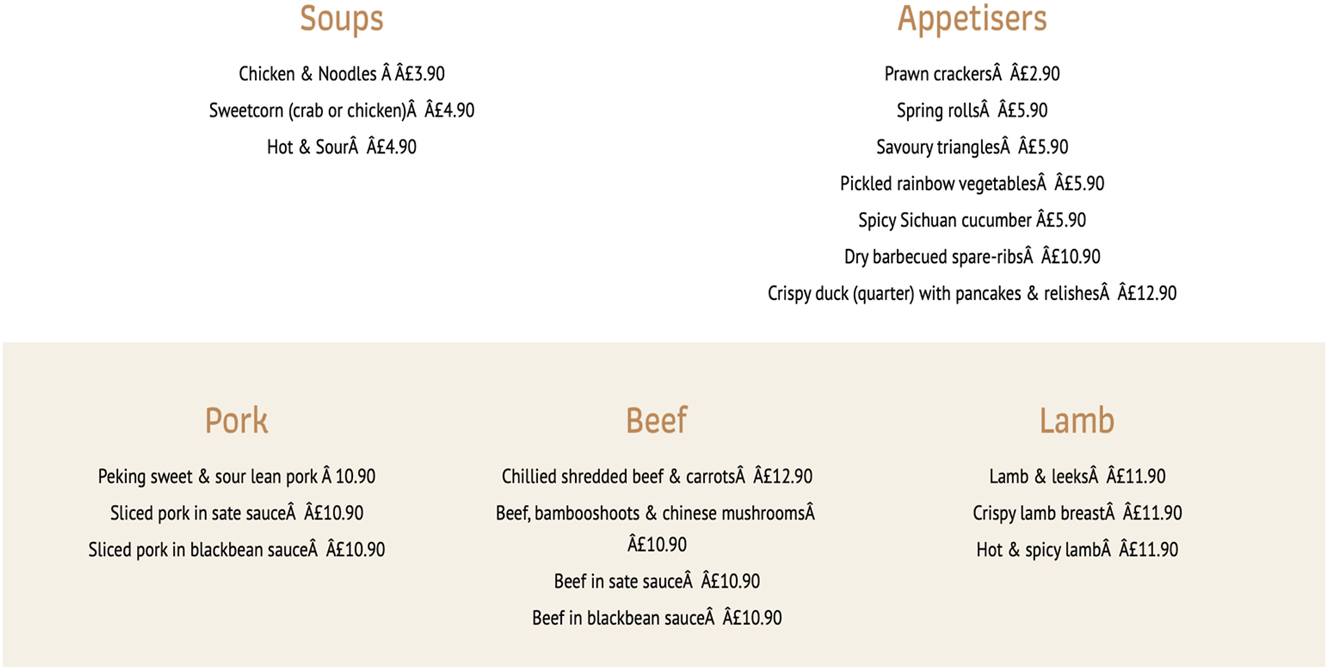

The semiotic erasure of Chineseness is also evident due to the absence of the Chinese language. We observe an interactional order mediated by the English language only. Both the physical menu used in the restaurant and the one displayed on its website are in English only (see Figure 2), suggesting again that English-speaking customers are the targeted customers. This English-speaking environment is further reflected in the staff composition, with the only hired customer-facing staff member being a white English speaker. The absence of Chineseness is also evident in the restaurant’s guestbook kept near the counter. The guestbook contains messages from customers, carefully selected and printed by the owners to mark the restaurant’s 40th anniversary. All the messages were written in English only, and the owners proudly noted that many of their patrons today remain local regulars. Thus, by not using or displaying any Chinese language, the restaurant implicitly constructs itself as a place for English speakers.

Menu of restaurant 1.

Such English-oriented customer selection is also evident in the activities the restaurant organizes and promotes, which are also showcased on its website. As one of the oldest restaurants in Liverpool, it features images of well-known celebrities who have dined there and highlights events such as wine tastings. Notably, there are no Chinese people or Chinese-themed events featured on the website, and again, all content is presented in English only. In this way, the restaurant offers an English-speaking customer base a ‘Chinese’ dining experience adapted to English taste and with minimal engagement with Chinese cultural elements and language, typical of culinary touristic experience catered for local customers (Long 2013). The absence of Chinese language and cultural references can also be interpreted as a strategy to exclude Chinese customers, as we will explain below.

The self-positioning of the restaurant as a Chinese restaurant for English-speaking customers is also shown in the food served, and in how the restaurateurs characterize their food. The menu reveals that the restaurant offers a wide range of Chinese dishes, from ‘Peking’ to ‘Sichuan’ to ‘sweet and sour’. When asked how they would characterize their food, the owners emphasized that it represents ‘our individual style’. As one of them explained below in Extract 1:

Extract 1:

Our food is based on the cooking style of my father-in-law, who worked in Beijing, Shandong, and Hong Kong before moving to the UK. I learned from him, and our cooking style is unique – it’s our individual style.

Their characterization of the food here as ‘individual style’ shows how personal histories and cross-generational learning shape their culinary approach, distinct from the idea of authenticity as being tied to a national or regional cuisine (see also Dalal 2024). Like other semiotic elements intended for English-speaking customers in this restaurant, this ‘unique’ cooking style is also tailored to appeal to that audience. When asked whether they ever had Chinese customers, they replied that they are ‘anti-Chinese’:

Extract 2:

We do not like Chinese customers, actually, we are anti-Chinese – they tend to be picky, and would say they don’t like this, don’t like that, it’s not what they expected.

This statement above positions the restaurateurs (‘we’) and Chinese customers (‘they’) as opponents when it comes to evaluating what Chinese food should be like. Their ‘anti-Chinese’ stance here also reaffirms our earlier analysis of the signage, which indexes English speakers as targeted customers. Such dislike of Chinese customers strikes a stark contrast to their like of English-speaking customers, as shown in their publicized display of close bond with English-speaking customers, e.g., through customer books and on their website, as mentioned above. Practices like this reinforce their self-positioning as a Chinese food provider for the English-speaking population. Such dislike of Chinese customers is also reminiscent of the findings by Moufakkir (2019) which shows that Chinese restaurant staff prefer English over Chinese customers in Chinatown in London.

Thus, the semiotics of the restaurant, as shown in the exterior and interior design, the menu, the staff composition, and the language used, showcases a distinctive approach to enacting Chineseness through nominal display of Chineseness, and such semiotic designs de facto helps the owners to target English-speaking customers as their preferred ones. Their self-positioning as a Chinese restaurant for English customers remains unchanged during and after Covid-19 when Chinese catering businesses were disproportionally affected due to anti-Chinese racism (Parveen 2020). The owners noted that their business suffered a dramatic downturn since Covid-19, with their customer volume being only about a third of that before Covid-19, and they have been struggling to recover – they were opening only three days a week on limited hours and hired only one waiting staff. Due to the poor performance of the business, they were considering early retirement and had listed the property for sale. And yet, they do not think their struggle with business has anything to do with anti-Chinese racism, as they explained below:

Extract 3:

Interviewer: So, you talked about the difficulties in COVID-19, and we are aware that during COVID-19 there’s certain hatred towards the Chinese community. Do you think you have, or your restaurant have been influenced by this kind of hatred or?

Owner: Funny enough, I was interviewed about this during COVID time. OK, yeah, about the anti-Chinese, that was happening in in Australia that was happening in America, and it was even happening in London or parts of England. But fortunately, Liverpool is such that that sort of racist racism doesn’t. I don’t say it doesn’t exist. Yeah, but it doesn’t happen, OK? It doesn’t happen like [in] Liverpool.

Here, in portraying Liverpool through a discourse of exceptionalism, that is, anti-Chinese racism is happening everywhere, but not in Liverpool, the owner displays strong pride in their local identity. By positioning themselves as a restaurant for the local English community, the owners constructed a distinctive diasporic identity that orients towards local English identity while framing Chinese food purely as a matter of personal family history. In taking this approach, the restaurant maintains little, if not non-existent, ties to the Chinese community in the UK or elsewhere. And since their relationship with the local English-speaking community was primarily based on the provision of food, it reinforces the orientalist stereotype of Chinese people as food providers in the UK (Parker 1994). This transactional relationship between the owners and their customers rendered them vulnerable and ‘dispensable’ (Chau and Yu 2001: 119), especially at times of rising anti-Chinese sentiments. A few months after our fieldwork, we learnt that the restaurant was permanently closed.

5.2 Restaurant 2

The second restaurant showcases a semiotic construction of cultural distinctiveness via a flexible assemblage of global Chineseness, that is, Chinese food is perceived and constructed by flexibly drawing upon a wide range of culinary types and traditions worldwide, which the restaurateur considers to be Chinese. The owner is a 3rd generation British Born Chinese with his ancestral family immigrating from Hong Kong. The restaurant’s name is in English only, consisting of an English word and a number displayed in green on the façade. The name did not come across as being indexical of Chineseness until the owners explained to us what the name means as below:

Extract 4:

The name of our restaurant takes its inspiration from Chinese Kungfu, especially the eternal stage of peace and unity.

Later, as we Googled to find more about the restaurant name, we discovered that it is also the name of a popular Kungfu movie made in Hong Kong in the 1970s. This cultural reference derives from the owner’s strong interest in Chinese Kungfu. Thus, the name indexes the owner’s personal identity as a Kungfu master, and his cultural links to Chinese martial art, but such indexicalities would only be noticeable for viewers very familiar with Chinese Kungfu. For many viewers, like us in the research team, without such knowledge about Kungfu or the movie, the sign would only serve an informative function, indexing the restaurant. However, the links between the restaurant and Chinese Kungfu become clearer inside the restaurant.

Upon entering, the restaurant has a bar area and then a seating area. While the decoration in the bar area is modern and sleek and does not showcase any culturally specific features, Chinese elements are immediately noticeable in the dining area, including displays of lion dance heads, calligraphy, and photos of Chinese sceneries (Figure 3). When asked about these decorations, the owner explained the intentions and meanings behind these signs:

Extract 5:

Owner: The Asian or Chinese elements like the Asia or Hong Kong, and the traditional characters, yeah, so my dad wrote that. My dad’s very good at that. OK, so [we] incorporate many Asian or some Chinese elements.

Interviewer: Yeah, it’s like it’s like art, like little art gallery here.

Owner: Yeah. So, everything, I want to show that, even though we’re not in China, a lot of the arts is still going, so you can see it’s the real stuff, not just pictures. Yeah, yeah. But not just something you find on this print, we can do it, we do the lion dance, we can do it. We want to do Kung Fu, we do it, so I hope it gives people confidence when they have the food.

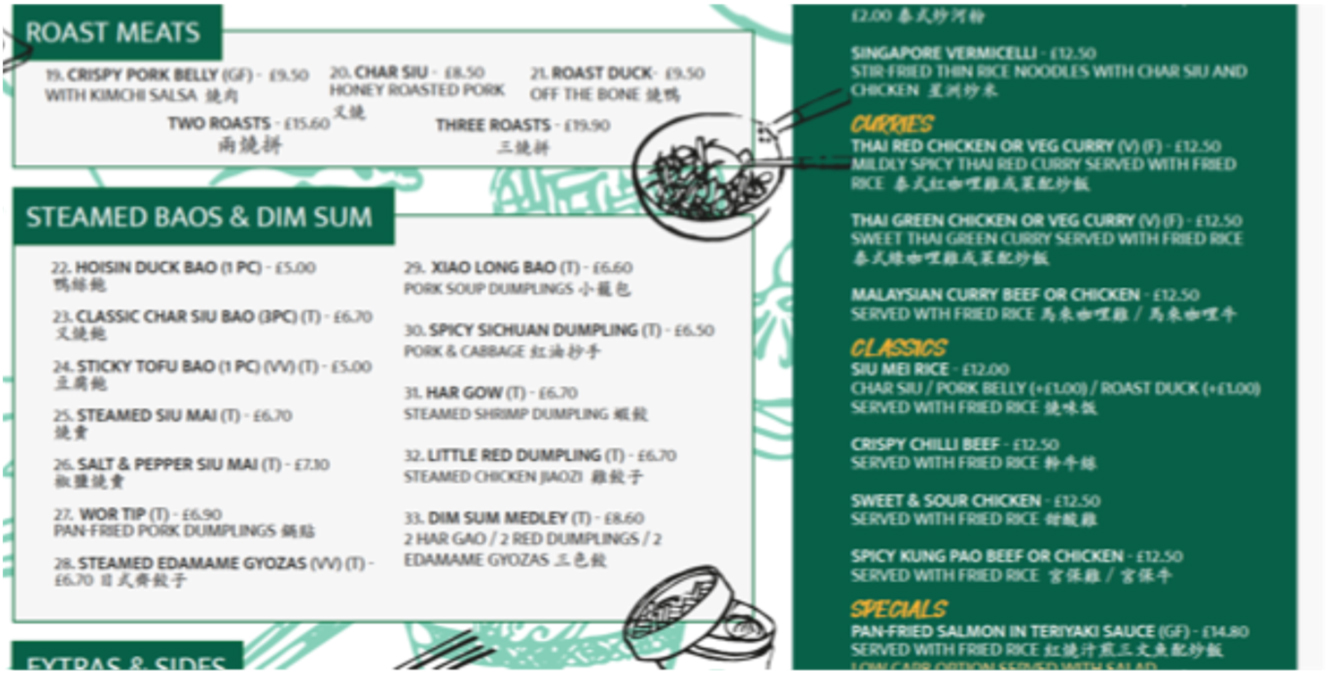

Screenshot of restaurant 2’s website.

According to the owner, incorporating ‘Chinese elements’ helps present a ‘real’ experience for customers. These decorations thus function as signs that can invoke indexical associations of authentic Chinese culture among its customers. The owner also stressed that this is not just for display ‘on this print’, but something they actually do. In other words, they are not just displaying Chinese culture as a decorative commodity on the wall but also actually performing Chineseness by teaching Chinese lion dance and Kungfu, as they have also advertised on their website, highlighting these as authentic parts of their life.

As explained on their website (Figure 3), their lion dance and Kungfu are ‘traditional’ and ‘local’ at the same time. Thus, this cultural performance is not just about showcasing diasporic links with ancestral home Hong Kong from the past but also about being part of the local community in Liverpool now via its membership in a local martial arts school. Therefore, the inclusion of Chinese lion dance is not simply a nostalgic display and commodification of ethnic culture from home; it also constructs a distinctive understanding of Chineseness as being local, i.e., an integral part of a multicultural and multi-ethnic city. Therefore, lion dance and lion heads decorations here have dual indexicalities, pointing to both ancestral home and local culture, past and present, showcasing and performing a distinctive diasporic identity that is both English and Chinese.

Such enactment of cultural distinctiveness is also shown in the restaurateur’s reflection below in Extract 6, where he explained how his diasporic identity has shaped his understanding of Chinese food:

Extract 6:

I’ll call [myself] BBC, so British born Chinese, yeah. Because of my background, because I was born here as well. So, I think I have a nice maybe understanding of the local market. So, I consider myself almost like half, almost half English and then half Chinese. So sometimes sometimes it is too too authentic, then it’s not too suitable for the Western people, but so my, my my target audience is still kind of local, local UK based people…I would say that you you want to reach wider customers. You you want to keep the authenticity of course, and do some, you know relative requirements and the adaptation to some local [customers].

Moving from his self-identification as a ‘BBC’ to reflecting on food provision as a balancing act between ‘keeping the authenticity’ and not being ‘too authentic’, the restaurateur here perceives and constructs Chinese food via a juxtaposition of uniqueness (‘authentic’) and assimilation (‘adaptation’), resonating with the key principle of cultural distinctiveness.

Such perception of Chinese food and its targeted customer base is semiotically reproduced in the menu. The menu in the restaurant was in English only, but they also have a bilingual English-Cantonese version online (Figure 4). We see that the English language was given prominence in the design of the menu, with English placed above traditional Chinese characters, highlighting that its main customers would be English-speaking. Customer-facing staff are all local white English people, creating an English-speaking dining environment. However, different from Restaurant 1, Chinese is not completely absent. The owner told us, while their targeted customers are local English, they were adding Cantonese to the menu, as they were hoping to attract more Chinese customers.

Menu of restaurant 2.

Apart from the choice of language, the name of the food also points to semiotic adaptations for its intended customers. For example, dumplings were given various names, such as ‘little red dumpling’, ‘dim sum medley’. As the owner explained below in Extract 7,

Extract 7:

So, our customers are kind of Western people, so my expectation is that all the different variations of dumplings, I don’t expect them to know everything … And if I could call all those dumplings, it makes the menu look really boring.

Such modifications of the names of food are thus strategically used to attract English-speaking customers, as also noted in Korean ethnic restaurants in the USA (Long 2013). The menu also includes other popular Asian dishes, such as Malaysian, Singaporean, and Thai dishes. Below, the owner explained again his understanding of authentic food.

Extract 8:

I want it to be authentic. So, I just want like I want the best of the Hong Kong dishes, best of the maybe maybe like a few Thai dishes and some of the like Chinese dishes. So not not like, not really a fusion. But more like just just like, OK, I want stuff from here. Some from there, some from there. this is my idea.

The above quote shows how ‘authentic’ Chinese food is imagined and constructed in ways shaped by not just host and ancestral home societies, but also by a commercial interest oriented towards an understanding of Chinese food in the wider sense of Chinese food in Hong Kong, in Chinese diaspora in Asia, and Asian food in general, illustrating flexible assemblage of Chineseness based on ethnicity, as opposed to nationality (Faist 2010).

Overall, the authenticity of Chineseness is ambivalently and strategically enacted in this restaurant, highlighting and showcasing close ties to Chinese communities in both the UK and Asia. This flexible assemblage of varied Chineseness and varied Chinese food and culture demonstrates the multiplicity, flexibility and dynamics of diasporic positioning, which are strategically enacted in semiotic designs to attract targeted customers.

5.3 Restaurant 3

The third Chinese restaurant embraces a normative and nationalist approach towards cultural distinctiveness, specifically, an ethnocentric view of Chinese food as it is practiced in mainland China. Originally a certified chef from mainland China, the owner came to the UK as a skilled migrant in the 1990s. He took great pride in being one of early migrants from mainland China, when visa sponsorship to the UK was normally exclusively granted to the exceptional elites. After working for a few years as a chef in the UK, he started his own business. He is passionate about the preservation and spread of Chinese food culture in the UK and was pivotal in setting up a British Chinese food association just before we met for this research.

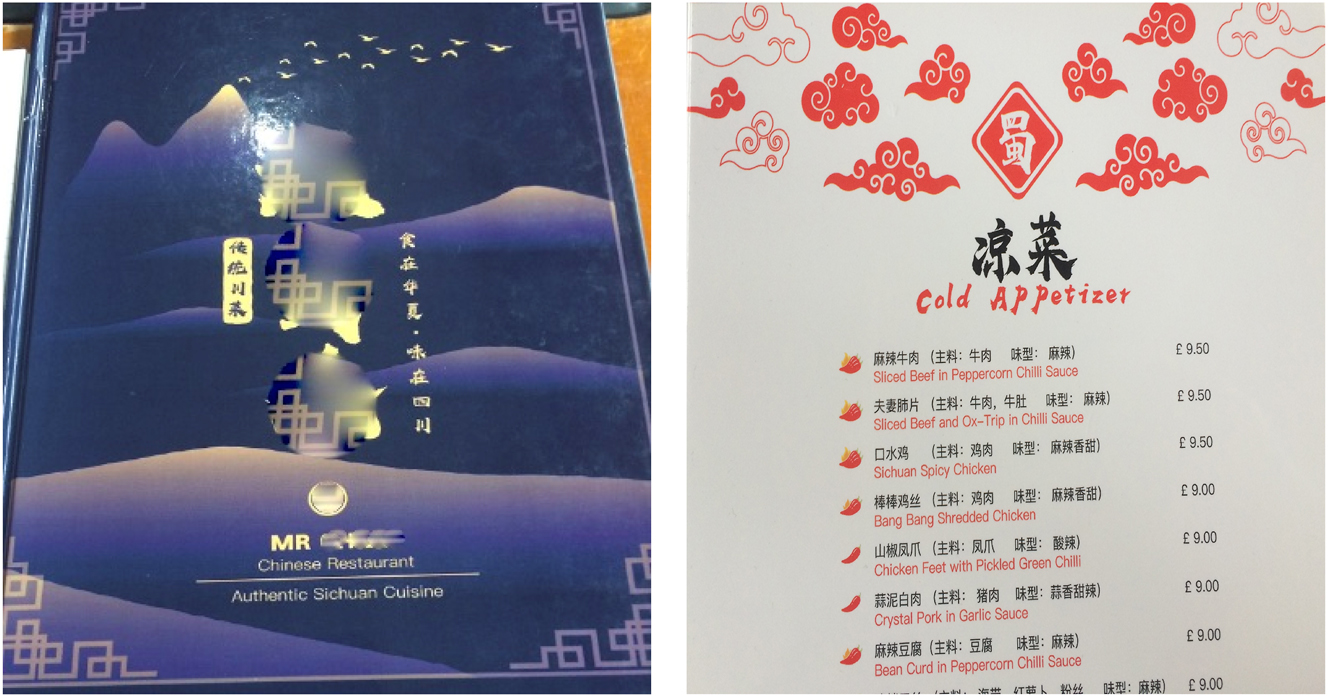

The restaurant has a bilingual name in English and simplified Chinese, shown on the façade on a bright red board – the color that indexes Chineseness (Figure 5). On the top is its Chinese-English bilingual name, with the simplified Chinese character in white and its English name ‘Mr [name]’ in black and white. The Chinese character named the regional variety of the food served – Sichuan food, and the English name reflects the flavor often associated with this cuisine style of spicy food. On the lower line is ‘Chinese restaurant’ in English in smaller font in capitalized letters. The Chinese name of the restaurant was repeated on the front door, and the cuisine style was also written in Chinese immediately to the left of the front door, again using a red background – the positioning and salience of the writing highlights the authenticity ‘正宗’ of the Chinese food (Cheng et al. 2024) in the restaurant.

Front of restaurant 3.

The Chineseness of the restaurant is immediately visible upon entering (Figure 6). The ceiling is decorated with several large Chinese lanterns and the walls are full of large calligraphies and paintings. We also observed that the background music played in the restaurants were always popular Chinese songs, and there was a TV on the wall, showing with no sound a Chinese news channel. The composition of working staff also highlights the Chineseness of the restaurant, different from restaurants 1 and 2. All waiting staff are Chinese, with one being a BBC bilingual in English and Chinese.

Interior of restaurant 3.

The salient Chineseness of the restaurant is also shown in the menu (Figure 7), which we were told was custom-designed by menu designers in mainland China. The menu book features in large fonts the Chinese name of the restaurant with traditional Chinese design patterns on the edge. On the menu, Chinese language was used above English in a larger font, the order of display highlighting the salience of Chineseness. The Chinese design pattern was also immediately visible inside the menu book with its red lucky clouds. Again, Chinese is placed above English, highlighting the prominence of Chinese. In Extract 9 below, the owner stressed the importance of serving authentic food, which he meant being ‘original/原汁原味’ and being the same as that in China:

Extract 9:

我觉得中餐就是要原汁原味, 我的原材料, 菜单, 再到厨师都必须要选择和国内一样的

Chinese food should be original, the ingredients, menu, and chef, they must be the same as in China.

我在国内怎么做的, 在英国也是这样做的

I would do it in the same way here in the UK, as I would in China.

Menu of restaurant 3.

The authenticity of food is thus constructed based on his homeland. However, there is also adaptation done to cater to non-Chinese customers: towards the end of the menu are several pages of set menus. We were told that these can make it easier for customers when they are not familiar with how to order Chinese food. The current chef of the restaurant also explained that he would adjust the level of spiciness for non-Chinese customers. Upon several visits, we noticed that the restaurants always had customers from different backgrounds. Thus, the design of the menu has customers with different preferences for Chinese food in mind.

The owner is keen on promoting authentic Chinese food and spoke of Chinese food as a source of national pride – linking it to the potential impact of Chinese culture overseas. As he put it below,

Extract 10:

中餐代表中国的形象, 要利用食物来扩大中国文化的影响力。

Chinese food represents the national image of China. We should use Chinese food as a tool to enhance the influence and impact of Chinese culture.

Through his perception and construction of Chinese food as ‘the national image of China’, and as ‘a tool to enhance the influence and impact of Chinese culture’, the owner was simultaneously constructing his own stance and self-positioning as a patriotic Chinese national, highlighting his diasporic links to his homeland, and his dedication to the promotion of Chinese food as Chinese culture overseas. The representation of Chinese food here thus aligns predominantly with that of mainland China, reproducing the official discourse of Chinese food as China’s soft power (Zreik 2023).

6 Conclusions

In this paper, we have presented a material ethnography of three Chinese restaurants in Liverpool, UK, focusing on their semiotic landscapes to reveal how cultural distinctiveness and diasporic identities are enacted in connection with their consumer selection strategies and self-positionings towards UK and Greater China. Drawing upon multiple sources of data, including public signage, menus, layout, decorations, languages, paintings, restaurant websites, and interviews, we traced the historicity of signs and showed that the semiotics of Chinese restaurants are shaped by owners’ varied interpretations of Chinese food, which in turn stems from their different migration histories, trajectories of mobility, and self-positioning. Each restaurant takes different approaches in their semiotic enactment of Chineseness: nominal display of Chineseness as family heritage, flexible assemblage of global Chineseness and ethnocentric reproduction of nationalist Chineseness. The study thus highlights the agentive role of semiotics in constructing the heterogeneity of diasporic identities and the cultural distinctiveness of Chinese food overseas. It showcases how Chineseness, in its multiple semiotic forms, is strategically performed or downplayed in the representation and construction of Chinese food, demonstrating how ‘textual and semiotic artefacts and objects’ are ‘sites where global and local perceptions and representations of subjectivities come together’ (Stroud and Mpendukana 2012: 150).

The semiotic-cultural distinctiveness of the three restaurants also reflects different histories and waves of Chinese migration to the UK. While existing literature has mostly focused on early waves of Chinese migrants in the catering industry, documenting Chinese restaurants as sites of exploitation and discrimination, this paper showcases three different restaurants as they engage in three distinctive ways of doing and negotiating Chineseness. To some extent, the three restaurants represent three distinctive business strategies reflective of three different historical times. The first restaurant’s self-positioning as a Chinese restaurant for local English customers represents early waves of Chinese businesses in the UK, which tend to reproduce its own dispensability and subjugation as a ‘Chinese food’ provider for English people (Chau and Yu 2001). The second restaurant reflects the flexibilityand dynamics of Chineseness based on a broad and flexible conceptualization of Chinese food culture. The third restaurant reflects a new wave of migrants from mainland China whose ethnic identity is synonymous with their national identity and who aim to reproduce and promote authentic Chinese food culture overseas. Semiotic landscapes thus reflect the changes across time in different waves of Chinese migration to the UK, especially in how they construct their diasporic identity through doing cultural distinctiveness as they variedly orient to, or position themselves against, Chinese communities in the UK, China, and elsewhere, resulting in the co-existence of multiple Chineseness (Gao 2021) in the UK today. These different enactments of cultural distinctiveness in semiotic landscapes are thus historically contingent, reflecting different ways of doing Chineseness across time and space.

This paper also reveals signs as a covert mechanism for self-positioning, intra-ethnic differentiation, and customer selection in restaurants. Semiotically enacted cultural distinctiveness functions as a filter for targeting and excluding customers from different language and ethnic backgrounds. Signs as acts of cultural distinctiveness are thus agentive in shaping social reality and can be ideologically embedded in the social structures of inclusion and exclusion. A material ethnographic study of the signs of ethnic restaurants can inform us about the changes in ethnic communities across generations and the subtle ways diaspora position themselves differently in relation to their own ethnic groups, to their place of residence, and to their ancestral home. As the semiotics of restaurants reveal how restaurateurs position themselves in terms of their diasporic identity and cultural distinctiveness, they are also (re)defining what Chinese food is, who would consume it, and what Chinese food means.

Funding source: Research England

Award Identifier / Grant number: Participatory Research Support Funding

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Jin Dai and Ye Tian for their assistance with data collection. Shuang Gao would like to thank Jakob Klein and colleagues for their helpful feedback on an earlier version of the paper presented at the SOAS Food Studies Centre.

-

Conflict of interest: None declared.

-

Research funding: Research England, Participatory Research Support Funding, University of Liverpool.

References

Abbots, Emma-Jayne, Jakob Klein & James Watson. 2016. Approaches to food and migration: Rootedness, being and belonging. In J. Klein & J. Watson (eds.), The handbook of food and anthropology, 115–132. London: Bloomsbury.10.5040/9781474298407.0013Suche in Google Scholar

Adamson, Sue, Bankole, Cole, Gary, Craig, Basharat Hussain, Luana Smith, Ian Law, Carmen Lau, Chak-Kwan Chan, Tom, Cheung. 2009. Hidden from public view? Racism against the UK Chinese population. https://essl.leeds.ac.uk › min_quan_finished_report.Suche in Google Scholar

Agha, Asif. 2006. Language and social relations. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511618284Suche in Google Scholar

Androutsopoulos, Jannis & Akra Chowchong. 2021. Sign-genres, authentication, and emplacement: The signage of Thai restaurants in Hamburg, Germany. Linguistic Landscape 7(2). 204–234. https://doi.org/10.1075/ll.20011.and.Suche in Google Scholar

Barabantseva, Elena. 2015. Seeing beyond an ‘ethnic enclave’: The time/space of Manchester Chinatown. Identities 23(1). 99–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/1070289x.2015.1016522.Suche in Google Scholar

Bauman, Richard. 1992. Contextualization, tradition, and the dialogue of genres: Icelandic legends of the Kraftaskáld. In Alessandro Duranti & Charles Goodwin (eds.), Rethinking context: Language as an interactive phenomenon, 125–145. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Ben-Rafael, Eliezer. 2013. Diaspora. Current Sociology Review 61(5-6). 842–861. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392113480371.Suche in Google Scholar

Blommaert, Jan. 2013a. Complexity, accent, and conviviality: Concluding comments. Applied Linguistics 34(5). 613–622. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amt028.Suche in Google Scholar

Blommaert, Jan. 2013b. Ethnography, superdiversity and linguistic landscapes: Chronicles of complexity. Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.10.2307/jj.27080070Suche in Google Scholar

Brewer, Marilynn B. 1991. The social self: On being the same and different at same time. Personality and Social Psychology Bullet 17. 475–482. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167291175001.Suche in Google Scholar

Bucholtz, Mary & Kira Hall. 2005. Identity and interaction: A sociocultural linguistic approach. Discourse Studies 7. 585–614. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445605054407.Suche in Google Scholar

Canagarajah, Suresh & Sandra Silberstein. 2012. Diaspora identities and language. Journal of Language, Identity and Education 11(2). 81–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348458.2012.667296.Suche in Google Scholar

Chau, Ruby C. M. & Sam W. K. Yu. 2001. Social exclusion of Chinese people in Britain. Critical Social Policy 21(1). 103–125. https://doi.org/10.1177/026101830102100103.Suche in Google Scholar

Chaudhry, Shiv & Dave Crick. 2004. The business practices of small Chinese restaurants in the UK: An exploratory investigation. Strategic Change 13(1). 37–49. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsc.655.Suche in Google Scholar

Cheng, Denian, Joanna Fountain, Christopher Rosin & Xiaomeng Lucock. 2024. Interpreting Chinese concepts of authenticity: A constructivist epistemology. Tourism Management 103. 104908. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2024.104908.Suche in Google Scholar

Dalal, Sanghamitra. 2024. “How authentic is your curry”? Performing curry and diasporic identity in Naben Ruthnum’s curry: Eating, reading, and race. Food, Culture and Society 27(2). 297–309. https://doi.org/10.1080/15528014.2024.2334094.Suche in Google Scholar

De Fina, Anna. 2013. Top-down and bottom-up strategies of identity construction in ethnic media. Applied Linguistics 34(5). 554–573. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amt026.Suche in Google Scholar

Faist, Thomas. 2010. Diaspora and transnationalism: What kind of dance partners. Diaspora and transnationalism: Concepts, theories and methods, 11, 9–34. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Gao, Shuang. 2021. Chineseness as competing discourses. In S. Gao & X. Wang (eds.), Unpacking discourses on chineseness: The cultural politics of language and identity in globalizing China, 1–12. Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.10.2307/jj.22730711.4Suche in Google Scholar

Guzzo, Siria & Anna Gallo. 2019. Diasporic identities in social practices: Language and food in the Loughborough Italian community. In G. Balirano & S. Guzzo (eds.), Food across cultures. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.10.1007/978-3-030-11153-3_4Suche in Google Scholar

Iedema, Rick. 2001. Resemiotization. Semiotica 137. 23–39.10.1515/semi.2001.106Suche in Google Scholar

Jaworski, Adam & Crispin Thurlow. 2010. Introducing semiotic landscapes. Semiotic landscapes: Language, image, space, 1–40. London, New York: Continuum.Suche in Google Scholar

Kroon, Sjaak. 2021. Language policy in public space: A historical perspective on Asmara’s linguistic landscape. Journal of Eastern African Studies 15(2). 274–296. https://doi.org/10.1080/17531055.2021.1904703.Suche in Google Scholar

Lazar, Michelle. 2022. Semiotic timescapes. Language in Society 51(5). 735–748. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0047404522000641.Suche in Google Scholar

Lee, Jerry Won. 2022. Locating translingualism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781009105361Suche in Google Scholar

Lipovsky, Caroline & Wei Wang. 2019. Wenzhou restaurants in Paris’s Chinatowns: A case study of Chinese ethnicity within and beyond the linguistic landscape. Journal of Chinese Overseas 15(2). 202–233. https://doi.org/10.1163/17932548-12341402.Suche in Google Scholar

Liverpool City Council. 2021. Ethnicity - Census 2021. https://liverpool.gov.uk/council/key-statistics-and-data/census-2021/ethnicity/.Suche in Google Scholar

Long, Lucy. 2013. Culinary tourism: A folkloristic perspective on eating and otherness. In Culinary tourism, 20–50. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky.Suche in Google Scholar

Lou, Jackie & Hua Zhu. 2020. Elephant in the room: Impact of Covid-19 on Chinatown. In Presentation in international symposium ‘responses of local communities to Covid19: Exploring issues of trust in the context of risk and fear’, hosted online by University of Paris and Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, December, 2020.Suche in Google Scholar

Lu, Shun & Gary Alan Fine. 1995. The presentation of ethnic authenticity: Chinese food as a social accomplishment. The Sociological Quarterly 36(3). 535–553. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-8525.1995.tb00452.x.Suche in Google Scholar

Mankekar, Purnima. 2002. “India Shopping”: Indian grocery stores and transnational configurations of belonging. Ethnos 67(1). 75–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/00141840220122968.Suche in Google Scholar

Moufakkir, Omar. 2019. The liminal gaze: Chinese restaurant workers gazing upon Chinese tourists dining in London’s Chinatown. Tourist Studies 19(1). 89–109. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468797617737998.Suche in Google Scholar

Parker, David. 1994. Encounters across the counter: Young Chinese people in Britain. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 20(4). 621–634. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183x.1994.9976457.Suche in Google Scholar

Parveen, Nazia. 2020. Restaurants are no longer empty: Visitors slowly return to UK’s Chinatowns. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/03/restaurants-are-no-longer-empty-visitors-slowly-return-to-uks-chinatowns.Suche in Google Scholar

Scollon, Ron. 2008. Discourse itineraries: Nine processes of resemiotization. Advances in discourse studies, 243–254. London: Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

Scollon, Ron & Suzie Scollon. 2003. Discourses in place: Language in the material world. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780203422724Suche in Google Scholar

Shohamy, Elana. 2015. LL research as expanding language and language policy. Linguistic Landscape 1(1-2). 152–171. https://doi.org/10.1075/ll.1.1-2.09sho.Suche in Google Scholar

Snyder, Charles R. & Howard L. Fromkin. 1980. Uniqueness: The human pursuit of difference. New York: Plenum Press.10.1007/978-1-4684-3659-4Suche in Google Scholar

Song, Miri. 2015. The British Chinese: A typical trajectory of ‘integration’? In Chinese migration to Europe: Prato, Italy, and beyond, 65–80. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.10.1057/9781137400246_4Suche in Google Scholar

Stroud, Christopher & Sibonile Mpendukana. 2009. Towards a material ethnography of linguistic landscape: Multilingualism, mobility and space in a South African township. Journal of Sociolinguistics 13(3). 363–386. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9841.2009.00410.x.Suche in Google Scholar

Stroud, Christopher & Sibonile Mpendukana. 2012. Material ethnographies of multilingualism: Linguistic landscapes in the township of Khayelitsha. Multilingualism, discourse, and ethnography, 151–164. New York, Oxon: Routledge.10.4324/9780203143179-22Suche in Google Scholar

Sutton, David. 2005. Synesthesia, memory, and the taste of home. In Carolyn Korsmeyer (ed.), The taste culture reader: Experiencing food and drink, 304–316. Berg: Bloomsbury Publishing.Suche in Google Scholar

The Economist. Liverpool’s chinatown. vol. 427, no. 9094, 2018, p. 30.Suche in Google Scholar

Torelli, Carlos J., Rohini Ahluwalia, Shirley Y. Y. Cheng, Nicholas J. Olson & Jennifer L. Stoner. 2017. Redefining home: How cultural distinctiveness affects the malleability of in-group boundaries and brand preferences. Journal of Consumer Research 44(1). 44–61.10.1093/jcr/ucw072Suche in Google Scholar

Tran, Tu Thien. 2019. Pho as the embodiment of Vietnamese national identity in the linguistic landscape of a Western Canadian city. International Journal of Multilingualism 18(1). 73–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2019.1604713.Suche in Google Scholar

Vignoles, Vivian L., Xenia Chryssochoou & Glynis M. Breakwell. 2000. The distinctiveness principle: Identity, meaning, and the bounds of cultural relativity. Personality and Social Psychology Review 4(4). 337–354.10.1207/S15327957PSPR0404_4Suche in Google Scholar

Woldemariam, Hirut & Elizabeth Lanza. 2015. Imagined community: The linguistic landscape in a Diaspora. Linguistic Landscape 1(1/2). 172–190. https://doi.org/10.1075/ll.1.1-2.10wol.Suche in Google Scholar

Xu, Samantha Zhan & Wei Wang. 2021. Change and continuity in Hurstville’s Chinese restaurants: An ethnographic linguistic landscape study in Sydney. Linguistic Landscape 7(2). 175–203. https://doi.org/10.1075/ll.20007.xu.Suche in Google Scholar

Yao, Xiaofang. 2020. Material narration of nostalgia: The linguistic landscape of a rural township in Australia. Sociolinguistic Studies 14(1-2). 7–31. https://doi.org/10.1558/sols.37218.Suche in Google Scholar

Zhu, Hua. 2017. New orientations to identities in mobility. In Suresh Canagarajah (ed.), The routledge handbook of migration and language, 117–132. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781315754512-7Suche in Google Scholar

Zhu, Hua. 2026. Translanguaging and interculturality: Critical issues in researching language, culture, and communication. In Li Wei, Prem Phyak, Jerry Won Lee & Ofelia Garcia (eds.), Handbook of translanguaging, 491–510. Wiley-Blackwell.Suche in Google Scholar

Zreik, Mohamad. 2023. Stirring up soft power: The role of Chinese cuisine in China’s cultural diplomacy. In K. Kankaew (ed.), Global perspectives on soft power management in business, 292–306. IGI Global Scientific Publishing.10.4018/979-8-3693-0250-7.ch015Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.