Abstract

While extensive research has explored the influence of emotions on students’ willingness to communicate (WTC) in face-to-face as well as online language classes, there is a notable gap in understanding how emotions such as shame, boredom, and enjoyment impact communication behavior in the context of a hybrid learning environment. To address this gap, the current study investigated the associations among shame, boredom, enjoyment, and WTC. It also examined whether WTC was predicted by the other three constructs, namely shame, boredom, and enjoyment. A total of 411 Saudi Arabian students completed four questionnaires. The results of structural equation modeling (SEM) revealed that the most significant factor influencing WTC was shame, followed by boredom. Unexpectedly, enjoyment did not influence students’ WTC. The implications of the obtained results are explained to educators to make efforts to enhance students’ emotional-communicative experiences in a hybrid learning environment.

1 Introduction

Over the past decades, an emphasis has been placed on the importance of the mode of delivery and learning context in learning the English language in non-native English-speaking contexts (Blake 2017). Consistent with prior work, like traditional classes, learning in virtual settings is affected by several psycho-affective factors (Bensalem et al. 2025; Wei and Xu 2021). An area that might be influenced by the mode of instruction is the concept of WTC, which refers to one’s readiness to enter into discourse at a specific time with a specific person or persons, using a language. (MacIntyre et al. 1998). It is one of the key determinants of learning success (Fathi et al. 2023). WTC has garnered a considerable amount of attention from language researchers due to its crucial role in enhancing learners’ communicative competence (Barrios and Acosta-Manzano 2025). In fact, it is one of the key predictors of communication behavior among learners (Elahi Shirvan et al. 2019; Pawlak and Mystkowska-Wiertelak 2015). The willingness of language learners to use the target language is caused by a wide variety of factors, some of which are psychological, others contextual, and some of which are linguistic (Khajavy et al. 2016). As noted by Mystkowska-Wiertelak and Pawlak (2017), WTC hinges upon a range of micro and macro factors in L2 education. The recent interest in exploring the impact of learners’ emotions on language learning has expanded to examining their dynamic role in communication behaviors and WTC (Barabadi et al. 2022; Barrios and Acosta-Manzano 2025; Chen et al. 2025; Derakhshan and Fathi 2024; Dewaele and Pavelescu 2019; Lee 2020; Lee and Hsieh 2019; Lin and Wang 2025). In their study, Bensalem et al. (2025) found EFL students’ WTC to be affected by emotional variables of grit, enjoyment, and boredom. However, such studies have not been conducted in multilingual contexts. Another construct, which has received insufficient scholarly attention in such contexts, especially in association with communication-related constructs is shame. Moreover, the possible interaction that shame may form with boredom, enjoyment, and WTC has not been thoroughly explored to date.

Although WTC has been the focal point of numerous studies, research has insufficiently addressed the specific role of discrete emotions such as shame, boredom, and enjoyment in shaping learners’ willingness to communicate. These emotions are theoretically significant because they capture different valences of learners’ affective experiences: shame as a self-conscious negative emotion that may inhibit communication, boredom as a disengaging emotion that reduces willingness to participate, and enjoyment as a positive activating emotion that can foster greater interaction and persistence (Yashima 2021). Understanding these three emotions is particularly relevant because they represent contrasting pathways through which affect influences communication behavior – either by constraining or facilitating students’ readiness to engage.

The rationale for investigating these emotions becomes stronger when considered in the context of blended learning. Unlike purely face-to-face or fully online modalities, blended environments combine synchronous and asynchronous modes of learning, which may intensify or mitigate the effects of emotions on learners’ WTC (Graham 2013). For example, the presence of digital mediation can exacerbate feelings of shame by reducing immediate interpersonal cues, heighten boredom through passive online content delivery, or amplify enjoyment by enabling flexible, interactive, and multimodal engagement. Thus, blended settings provide a distinctive context in which these emotions may function differently than in traditional learning environments. Therefore, this study seeks to model the impact of shame, boredom, and enjoyment on WTC in a blended learning environment, not merely because prior research is lacking, but because theoretical and pedagogical grounds suggest that these emotions are critical determinants of communication in such contexts. By clarifying how affective experiences influence students’ WTC in blended settings, the study may inform language teachers and educators of the nuanced role of emotions in technology-mediated classrooms, extending insights from face-to-face education to a learning mode that is increasingly central in higher education worldwide.

2 Literature review

2.1 Willingness to communicate (WTC)

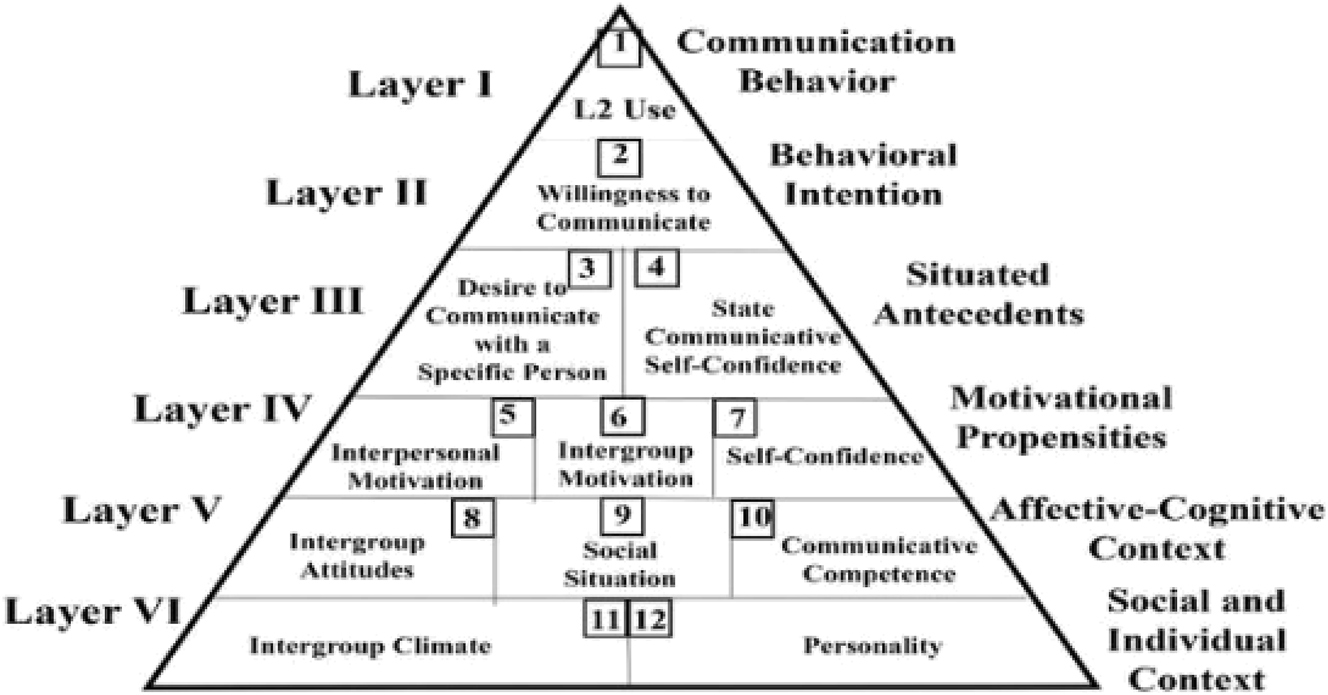

The construct of WTC originated in first language (L1) literature when it was introduced by McCroskey and Baer (1985). Initially, it was considered a stable individual trait, as outlined by McCroskey (1992). Through the work of MacIntyre et al. (1998), this concept was later integrated into language education research. Technically, WTC refers to “a readiness to enter into discourse at a particular time with a specific person or persons” (MacIntyre et al. 1998, p. 547). It is dynamic in nature since multilingual learners usually exhibit varying levels of WTC over time and in different situations. This disparity can be attributed primarily to a range of factors, including psychological, linguistic, and contextual differences (Khajavy et al. 2018). In an effort to illustrate that WTC can be influenced by various factors, MacIntyre et al. (1998) devised a model structured as a multilayered pyramid (Figure 1).

The multilayered pyramid model WTC (MacIntyre et al. 1998).

One of the components of this model is a fundamental layer that incorporates stable macrosocial and psychological characteristics within the context of both the individual and the social setting. According to Dewaele (2019), the highest layers of the pyramid are comprised of dynamic proximal psychological and contextual variables. These variables include affective-cognitive context, motivational propensities, and contextual antecedents. As a result, WTC emerges as a construct that is formed by a multitude of intrapersonal and interpersonal elements that interact with one another. When learners are given the opportunity to communicate, these elements converge to affect their determination to either join in a conversation or retreat from it (MacIntyre et al. 2020). Furthermore, these factors collectively influence the decision of a speaker to engage in communication.

Fostering WTC in the target language has become a key objective in language training (Dewaele 2019). This is because the focus of language learning and teaching has shifted toward communication over the past few decades (Dewaele 2019; Khajavy et al. 2018; MacIntyre et al. 2020). The significance of WTC has spurred numerous studies delving into its nature and exploring various variables that influence learners’ choices to either initiate or avoid communication (Feng et al. 2025; Henry and MacIntyre 2023; MacIntyre et al. 2025). Some studies focused on affective variables, notably anxiety (e.g., Barrios and Acosta-Manzano 2025; Kruk 2022) and motivation (e.g., Lee and Drajati 2019; Ye and Hu 2025). With the rise of the positive psychology (PP) movement, scholars have started exploring the impact of positive variables on WTC, namely grit (Bensalem et al. 2023; Fathi et al. 2021), while others have examined the role of enjoyment on learners’ communication behavior (Fattahi et al. 2023). Two other emotions that have not been examined enough are boredom, which has a debilitative effect on WTC (Kruk 2022), and shame (Cook 2006; Galmiche 2017).

2.2 Foreign language enjoyment (FLE)

Over the course of more than four decades, a significant amount of research in the field of SLA has focused on negative emotions, particularly anxiety (Dewaele and MacIntyre 2016; Fathi et al. 2023). Researchers have then been encouraged to explore the impact of positive emotions on language teaching and learning skills and practices in light of the move toward incorporating PP into SLA (Ghiasvand and Sharifpour 2024; Jin and Zhang 2021). In their seminal study, Dewaele and MacIntyre (2014) developed the concept of foreign language enjoyment (FLE) in response to the growing interest in positive emotions. FLE refers to “a complex emotion capturing interacting dimensions of challenge and perceived ability that can reflect the human drive for success in the face of difficult tasks” (Dewaele and MacIntyre 2016, p. 216). Jiang and Dewaele (2019) distinguished between two categories of FLE: private and societal FLE. Private FLE refers to subjective experiences such as feelings of pride, satisfaction, and a sense of achievement, whereas social FLE includes elements such as sharing classroom stories, laughter, and good engagement with teachers and peers. Additionally, Jin and Zhang (2019) proposed a third sub-dimension, teacher-supported FLE, which denotes the learner’s opinion of the teacher as friendly and supportive. Theoretically, FLE is supported by Fredrickson’s (2003) broaden-and-build theory, which is the foundation of the positive psychology movement in language acquisition. This theory emphasizes the impact and contribution of positive emotions on other positive emotions and on academic outcomes in learners. Based on this theory, several studies were carried out in order to investigate the role that FLE plays in the communication behavior of students. For example, Dewaele (2019) identified FLE as one of the positive predictors of WTC among students enrolled in English classes in Spain. In the Iranian context, Fathi et al. (2023) examined the possible impact of L2 self, intercultural communicative competence, and FLE among a group of 601 intermediate Iranian EFL learners. The results of their study revealed that the ideal L2 self, intercultural communicative competence, and FLE were direct predictors of WTC. Similar findings were reported by (Ebn-Abbasi et al. 2022) who discovered that FLE is a predictor of WTC among Iranian EFL students attending government and private schools. In the same Iranian educational setting, Fattahi et al. (2023) investigated the influence of FLE and boredom on the WTC of learners, who were enrolled in online sessions. Their results pointed out that FLE helped to alleviate, to a certain extent, the effects of boredom that learners encountered when participating in their online courses. In the Saudi context, Alrabai (2024) tested a model of WTC among Saudi college EFL students. The results indicated that FLE had a minor positive influence on WTC, supporting the claims made by Dewaele and Dewaele 2018; MacIntyre et al. 2019; Teimouri 2017, all of whom proposed that a strong sense of enjoyment is a crucial requirement for learners to demonstrate WTC. Despite these influential studies, the interaction of these constructs in blended learning settings has received scant attention, so far.

2.3 The construct of foreign language learning boredom (FLLB)

The construct of Foreign Language Learning Boredom (FLLB) has recently garnered increased attention in the field of language learning and instruction, and it has emerged as a subject that is particularly significant for researchers (Derakhshan et al. 2024; Solhi et al. 2024, 2025). Research on boredom was initiated in the Polish context, and then it captured the attention of scholars in other settings, such as China, Turkey, and Iran. Li et al. (2023) defined boredom as a state of disengagement resulting from a lack of interest in and involvement in language learning (Kruk et al. 2021). In their research, Li et al. (2023) considered boredom as a condition of disengagement characterized by a lack of interest and involvement in language acquisition (Kruk et al. 2021). This condition is characterized by a combination of negative emotions, including disappointment, inattention, dissatisfaction, annoyance, and a diminished sense of vitality (Kruk and Zawodniak 2018). FLLB is a prevalent issue in educational settings, exerting a substantial impact on student motivation, engagement, and academic performance (Daniels et al. 2015; Derakhshan et al. 2021). In the context of language learning, FLLB can be categorized into two types: trait boredom and state boredom. When an individual consistently experiences or has a stable disposition towards boredom during language learning activities or class attendance, it is referred to as “trait boredom” (Wang 2023). On the other hand, “state boredom” is a transient and situational experience triggered by specific circumstances (Putwain and Pescod 2018). FLLB is a phenomenon that can be categorized based on both situational and personal factors. It is a subjective experience that varies depending on the individual and their specific context. In other words, boredom has different roots and outcomes as substantiated by previous studies (Pawlak et al. 2025). It has gained more attention, especially in the context of online instruction after the COVID-19 pandemic (Dewaele and Li 2021). Although correlations have been reported for boredom and factors such as WTC (Fathi et al. 2023; Kruk 2022), grit (Alrabai 2024), and enjoyment (Wang et al. 2021), there is a dearth of evidence on its interplay with shame.

2.4 Shame

Galmiche (2017) coined the term foreign language classroom shame, which is intricate, dynamic, self-evaluative, and notably debilitating and paralyzing. It emerges specifically in the classroom and may affect students regardless of their level of the target language proficiency. According to Galmiche (2017), shame is made up of a number of different aspects that are intertwined with one another, including the beliefs, self-perceptions, feelings, emotions, and personality traits of the learner, socio-cultural and contextual particularities, and other stakeholders’ influence (Galmiche 2017). Due to the complexity of this emotional experience, individuals may feel high levels of anxiety, avoidance, or disengagement from the process of learning and using a foreign language. Additionally, shame is a variable that contributes to a persistently decreased sense of self and a view of an identity that is faulty (Galmiche 2018). Previous research indicates that shame has a significantly detrimental impact on students’ language learning process. Specifically, a number of studies indicate that shame appears to hinder students’ willingness to use language (Galmiche 2017; Galmiche 2018; Teimouri 2018). For example, a significant link was found between the likelihood of experiencing shame in multilingual contexts and WTC, according to the findings of Teimouri’s (2018) study, which was conducted on Iranian students majoring in English. In the same vein, students who were prone to feelings of shame indicated a strong unwillingness to participate in activities that took place within the English classroom, as demonstrated by Galmiche’s (2017) research.

In general, shame has been found to be connected with avoidance and withdrawal behavior in communication, as noted by Cook (2006) and Galmiche (2017). These findings align with the concept of shame in the area of psychology. Not only is the phenomenological sensation of wishing to hide or disappear, or even feelings of wanting to cease to exist, associated with shame, but it is also tied to a loss of the ability to communicate, as stated by Lewis (2019). Shame is a multifaceted concept. It is vital to explore more deeply the significance of this emotion when coupled with other variables in SLA because of the enormous impact that shame has on an individual’s readiness to discuss their thoughts and feelings.

2.5 Combined emotions and WTC

Considering that learners rarely experience one single emotion at a time (Fattahi et al. 2023), students may enjoy one aspect of language learning, such as reading a new text, while suffering from boredom when engaged in critical analysis of the same text (Dewaele et al. 2022). Therefore, numerous studies on WTC involved combining and examining a number of constructs in order to determine their relative impact on students’ communication behavior. Driven by the PP movement, recent studies (Ebn-Abbasi et al. 2022; Li et al. 2022) have set out to examine enjoyment combined with other variables, namely grit (Alrabai 2024), boredom (Li et al. 2022), and anxiety (Barrios and Acosta-Manzano 2025).

One of the aims of these investigations was to determine the relative importance of each predictor. There were no studies that examined the combined effects of shame, FLLB, and FLE but rather on the combined variables of FLE and FLLB, which have yielded inconsistent results regarding the impact of each variable. Wang et al. (2021) found that FLE had a stronger correlation with WTC, both in and outside of the classroom, when compared to FLLB. In a separate study, Li et al. (2022) found a stronger correlation between FLE and WTC compared to the correlation between FLLB and WTC. Nevertheless, Fattahi et al. (2023) discovered a substantial impact of FLLB on WTC, while Alrabai (2024) identified FLE as a small yet significantly positive predictor of WTC, with FLLB having no significant predictive power. The varying results in these studies may be attributed to differences in the educational contexts under investigation as well as the mode of learning (face-to-face vs. online). Additionally, the use of inadequate statistical tools, such as regression coefficients, could be a contributing factor. Regression coefficients may not always offer a precise ranking of predictors, particularly when they are correlated, as noted by Tonidandel and LeBreton (2011). Motivated by these shortcomings, this study was conducted in the context of blended language learning, as explained below.

2.6 The current study

Previous studies have found negative significant correlations between shame, FLLB, and WTC (Li et al. 2022; Teimouri 2018; Wang et al. 2021) and positive significant relationships between FLE and WTC (e.g., Li et al. 2022; Wang et al. 2021). However, there has been little research into an indirect association between these predictive variables. Investigating potential intricate relationships among emotion variables is of paramount importance (Dewaele et al. 2022). This study sets out to address two gaps in the literature. First, we aim at extending the line of research regarding the variables that may act as predictors of WTC by proposing a model that includes not only FLLB and FLE but also shame. In addition, previous studies examining predictors of WTC were conducted either face-to-face or online.

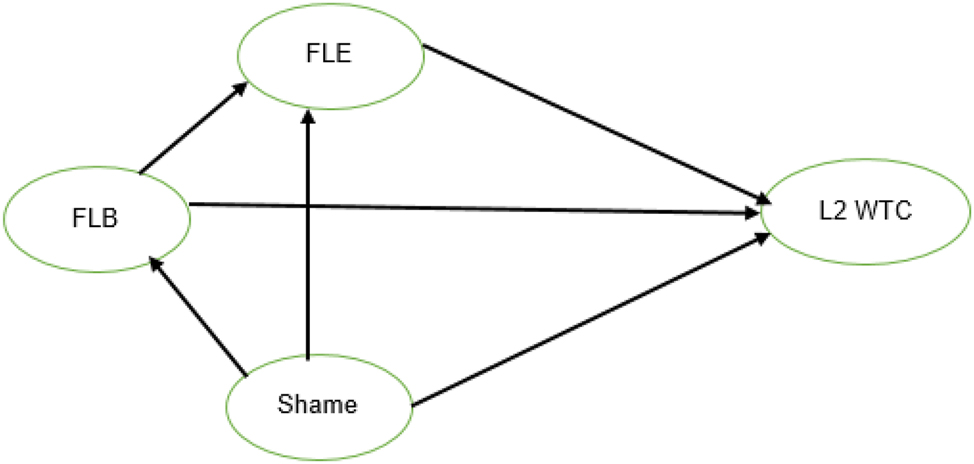

Taken together, the reviewed studies provide a clear theoretical basis for the proposed hypotheses. Prior research has shown that shame, as a self-conscious, inhibiting emotion, tends to suppress learners’ communicative behaviors, making it reasonable to expect a negative link between shame and WTC in hybrid classes (H1). Building on evidence that foreign language learning boredom (FLLB) often co-occurs with negative emotions and diminishes engagement, it is plausible that the effect of shame on WTC is partially transmitted through boredom (H2), while boredom itself can directly reduce WTC (H3). Conversely, the literature on reciprocal influences among emotions suggests that the impact of boredom on WTC may also be mediated by shame, given their shared role in undermining confidence and willingness to interact (H4). Finally, although enjoyment (FLE) is typically considered a positive driver of communication, findings in blended and technology-mediated contexts highlight the possibility that enjoyment may not always translate into greater WTC due to increased cognitive load or contextual barriers (e.g., fragmented interaction or performance pressures), thus warranting the expectation of a negative predictive link in this setting (H5). These justifications, grounded in empirical and theoretical insights, clarify the rationale for each hypothesis and situate them within the broader affective framework of WTC in hybrid learning environments. The current study, however, examines the interactions between these variables in a blended learning environment. Based on previous research, the following hypotheses were proposed, as shown in Figure 2.

H1. Shame will negatively predict WTC in hybrid language learning classes.

H2. The association between shame and WTC in hybrid language learning classes will be mediated by FLLB.

H3. FLLB will negatively predict WTC in hybrid language learning classes.

H4. The association between FLLB and WTC in hybrid language learning classes will be mediated by shame.

H5. FLE will negatively predict WTC in hybrid language learning classes.

WTC model.

3 Methods

3.1 Participants and context

A total of 411 multilingual students from several campuses of a public university in Saudi Arabia participated in this study. Participants were enrolled in courses offered in a hybrid format, implemented by university officials as a post-COVID-19 strategy to gradually reintroduce in-person instruction. The sample consisted predominantly of females (80.26 %), with males comprising 19.8 %. Participants’ ages ranged from 18 to 27 (M = 21.76, SD = 2.56). The students represented two major academic tracks: English-related programs (61.5 %) and medical programs (38.5 %). While English and medical students may differ in academic objectives, motivations, and classroom experiences, both groups were enrolled in the same hybrid learning environment, allowing for an examination of the effects of teacher immediacy and rapport across diverse disciplines. Including both majors provides a broader understanding of how affective and relational factors influence resilience in hybrid learning contexts. Participants were distributed across academic years, with 35.8 % in their first year, 33.4 % in their sophomore year, 18.7 % in their third year, and 12.1 % in their fourth year. All participants completed the survey voluntarily after providing formally signed consent forms. It is important to acknowledge, however, that combining English and medical students may introduce variability due to differences in prior language experience, learning objectives, and engagement strategies. Future research may consider examining these groups separately or including major as a moderating variable to further clarify potential differential effects.

3.2 Instruments

3.2.1 WTC scale

To assess participants’ WTC, a short version of Weaver (2005) WTC scale was used. It included five items using a 5-point Likert scale, with ‘1’ indicating a clear absence of desire and ‘5’ indicating a clear state of preparedness. The reliability of WTC was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, resulting in a value of 0.91, as stated in Table 1.

Descriptive statistics, reliability, normality, and correlations (N = 411).

| Mean | SD | (α) | Skewness | Kurtosis | Correlation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||||||

| 1. FLE | 3.94 | 0.76 | 0.92 | −0.11 | −0.45 | 1.00 | |||

| 2. FLLB | 2.63 | 0.93 | 0.91 | 0.17 | −0.22 | −0.578** | 1.00 | ||

| 3. Shame | 2.61 | 1.04 | 0.89 | 0.15 | −0.53 | −0.254** | 0.479** | 1.00 | |

| 4. WTC | 3.70 | 1.25 | 0.91 | −0.01 | −0.44 | 0.293** | −0.422** | −0.529** | 1.00 |

-

**p < 0.01.

3.2.2 Foreign language enjoyment scale

The FLE was assessed by employing a modified version of Botes et al.’s (2021) Short Form of the Foreign Language Enjoyment Scale (S-FLES), wherein each item specifically referred to English class. The scale utilized in this study is derived from Dewaele and MacIntyre’s (2014) original 21-item scale. It consists of nine items specifically designed to measure positive emotions experienced during second-language learning. The S-FLES considers three sub-scales, namely ‘instructor recognition’, ‘individual pleasure’, and ‘societal pleasure’. The items were answered using a 5-point Likert scale. The scale showed a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.92.

3.2.3 Foreign language learning boredom scale

FLLB was assessed using an eight-item subset of the Achievement Emotions Questionnaire developed by Pekrun et al. (2011). The questionnaire items were modified to reflect the unique context of language learning. Participants were asked to rate their level of agreement with the statements on a 5-point scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” With Cronbach’s alpha rating of 0.91, the scale indicated a high level of reliability.

3.2.4 Shame scale

To assess students’ levels of shame, a shortened version of the Achievement Emotions Questionnaire (Bieleke et al. 2021), was used in this study. The five item- survey items included statements such as “I get a sense of folly when I speak in class” and “I feel a deep sense of shame when I become aware of my lack of skill”. The scale was very reliable, as evidenced by Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.89.

3.3 Data collection procedure

In line with research objectives, the researchers examined the literature and used four validated scales on the constructs of concern. They were converted to an online survey for the participants’ convenience rather than printed versions. Upon getting approval for the research protocol from the Institutional Review Board (IRB), 450 college students were invited to voluntarily participate in the study. Of these students, after a week, 411 agreed to participate in the study and submitted their questionnaires completely in the due time. The questionnaires were in English and the way each scale would be responded was explained at the outset of the survey. The goal of the study was also described to the participants. As the survey was online, the researchers gave the students an assurance of their privacy and confidentiality of information. The participants were also informed that they possess the right to withdraw from the study at any point. To observe ethics in research, a consent form was provided at the beginning of the survey. With singing that, the participants expressed their willingness to fill out the survey voluntarily. After two weeks, a sample of 411 valid questionnaires were collected from the participants. Their responses were checked and prepared for the final quantitative analyses, explained below.

3.4 Data analysis

The data analysis was conducted utilizing IBM SPSS 26 and AMOS 24. Preliminary analyses were conducted by calculating kurtosis, skewness, and descriptive statistics in the first stage. Normality assessment was conducted through the examination of skewness and kurtosis values, both falling within the acceptable range of −2 and +2, as per Kunnan (1998), affirming the data’s normal distribution. Furthermore, the reliability of each scale was determined using alpha coefficients, with values exceeding 0.70, indicating a satisfactory level of internal consistency. The hypothesized associations among the variables were examined by the application of structural equation modeling (SEM). Prior to examining the interdependence of variables in a structural model, Hair et al. 2012 advised validating the measurement models of these variables by confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Regarding the model evaluation, Maximum Likelihood was employed along with other fit indices. The indices utilized in this study encompassed χ2/df, Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). Furthermore, we utilized the bootstrapping method, as proposed by Shrout and Bolger (2002), to assess the statistical significance of indirect effects. In order to achieve this objective, a total of 2000 bootstraps were created, and confidence intervals for both the lower and upper limits were computed as well (Hayes 2017).

4 Results

4.1 Descriptive statistics

The statistical measures, including means, standard deviations, coefficient alphas, skewness and kurtosis values, and correlations of all variables, are displayed in Table 1. Results demonstrate a significant correlation between shame, boredom, enjoyment, and WTC. The WTC exhibited the most robust negative association with shame (r = −0.526, p < 0.001). Moreover, boredom showed the second highest negative correlation with WTC (r = −0.422, p < 0.001). The connection with enjoyment was the lowest, and it was positive but small (r = 0.293, p < 0.001).

4.2 Structural equation modelling (SEM)

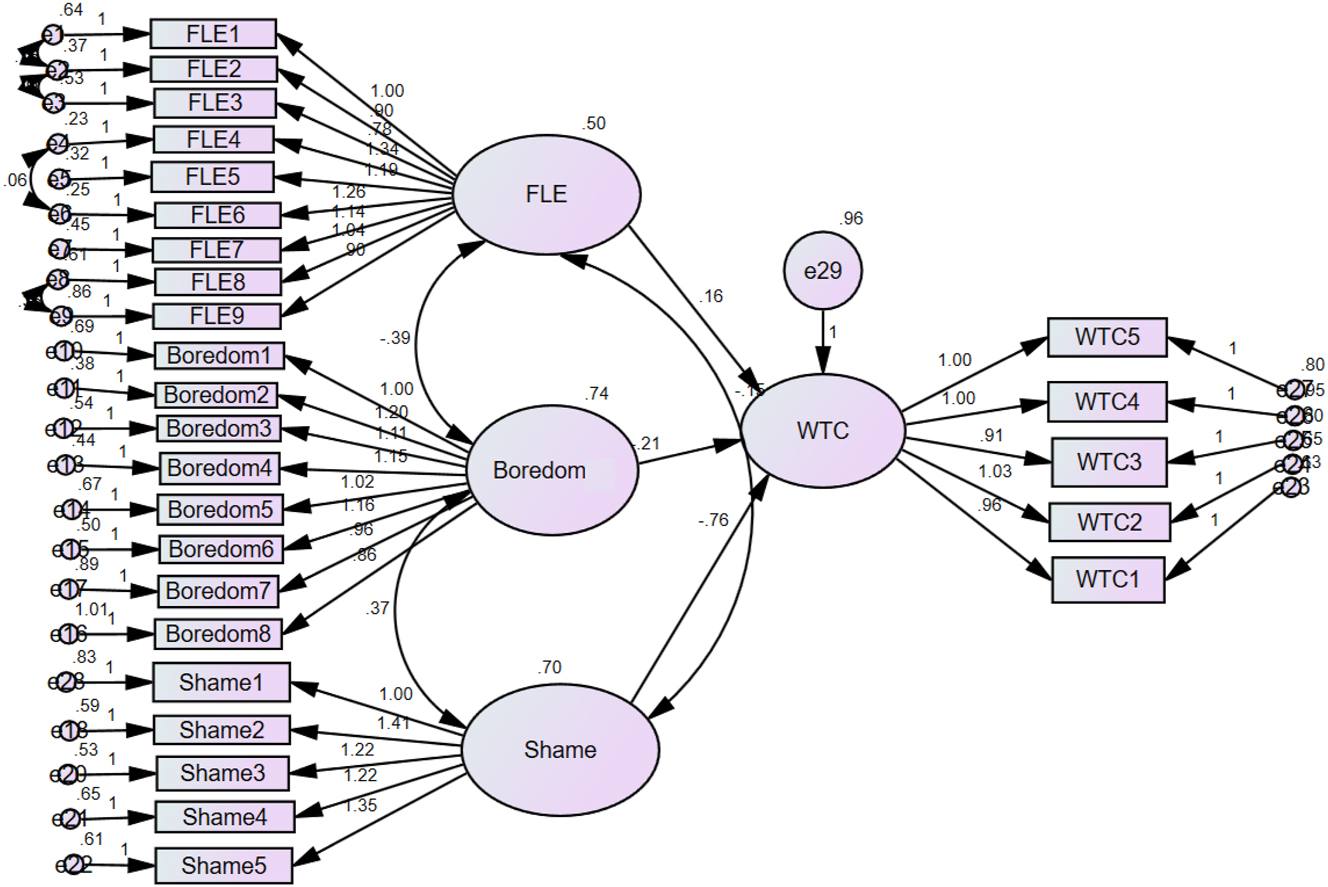

The self-report scales underwent an examination of construct validity using CFA (Figure 3). Goodness-of-fit indices were employed to assess the appropriateness of the measurement models. This evaluation includes testing the measurement models of shame, boredom, enjoyment, and WTC. As indicated in Table 2, the models exhibited a good fit to the data. AMOS was used to build a structural equation model, which was then used to investigate the correlations between FLE, FLLB, Shame, and WTC (see Figure 2). If the values of the goodness-of-fit (GFI) indices, such as the Tucker and Lewis (1973) index (TLI) and the confirmatory fit index (CFI), are equal to or greater than 0.90, the model fit is considered acceptable (Hu and Bentler 1999). In addition, a normed chi-square value less than 3 indicates an acceptable fit (Hu and Bentler 1999). The model is also considered to have an adequate fit if the standardized root mean square residual (RMR) computed by AMOS is less than 0.05 and the root mean square error approximation (RMSEA) values are lower than 0.08 (Byrne 2013). Table 2 shows that the fit indices for the model are within acceptable ranges.

CFA model of the FLE, shame, boredom, and WTC scales.

Goodness-of-fit indices for the CFA model for all variables.

| χ 2 /df | CFI | TLI | SRMR | RMSEA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 2.617 | 0.914 | 0.910 | 0.061 | 0.069 |

Shame had the largest significant direct positive effect on learner WTC with a medium size effect (β = −0. 43, t = −9.169, p < 0.001), followed by a small effect of FLLB (β = −0.17, t = −3.016, p < 0.05). However, the effect of FLE on students’ WTC was weak and did not have statistical significance (β = 0.09, t = 1.754, n.s). A close examination of the paths among predictors revealed a significant correlation between FLLB and FLE (r = 0.58, p < 0.001) and shame (r = 0.48, p < 0.001). Also, the correlational path between shame and FLE was significant (r = −0.25, p < 0.001). In sum, the results of the SEM analysis indicated that boredom and shame were significant predictors of students’ WTC, while enjoyment was not a predictor.

In addition, we examined multiple pathways connecting latent variables to assess their direct and indirect impacts on WTC (see Table 3). First, a mediation analysis was performed to investigate if FLLB had an indirect impact on the association between shame and WTC. The mediation model had negative and statistically significant indirect effects (β = −0.126; p < 0.01), as well as a negative and significant total effect (β = −0.639; p < 0.001). FLLB served as a mediator in the connection between shame and WTC since the 95 % confidence interval for the indirect impacts did not include the value of zero (95 % CI [−0.199; −0.069]). Similarly, a mediation analysis was performed to investigate if FLE had an indirect impact on the connection between shame and WTC. The mediation model had negative and statistically significant indirect effects (β = −0.052; p < 0.001). Consequently, FLE played a partial role in mediating the connection between shame and WTC. Nevertheless, the combined influence of the FLE and FLB did not have a significant indirect effect on WTC (β = −0.030; n.s).

Mediation model results.

| 95 % confidence interval | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | P | Lower | Higher | |

| Direct effects | ||||

| Shame → WTC | −0.441 | <0.001 | −0.562 | −0.318 |

| FLB → WTC | −0.294 | <0.001 | −0.698 | −0.636 |

| Indirect effects | ||||

| Shame → FLB → WTC | −0.126 | <0.001 | −0.199 | −0.069 |

| Shame → FLE → WTC | −0.052 | <0.001 | −0.095 | −0.021 |

| Shame → FLB → FLE →WTC | −0.030 | 0.069 | −0.073 | 0.003 |

| FLB → shame → WTC | −0.274 | <0.001 | −0.370 | −0.188 |

| FLB → FLE → WTC | −0.057 | 0.170 | −0.698 | −0.636 |

| FLB → shame→ FLE → WTC | 0.0010 | 0.08 | −0.470 | −0.219 |

| Total effects | ||||

| Shame → WTC | −0.639 | <0.001 | −0.744 | −0.526 |

| FLB → WTC | −0.569 | <0.001 | −0.698 | −0.441 |

Other pathways were investigated to determine if shame and FLE had an indirect impact on the connection between FLLB and WTC, either separately or jointly. The findings showed that shame had an indirect negative and statistically significant effect on the connection between FLLB and WTC (β = −0.274; p < 0.001). However, the overall effect was negative and significant (β = 0.569; p < 0.001). Thus, FLLB played a role in partially mediating the connection between shame and WTC. Furthermore, the 95 % confidence interval for the indirect impacts did not include the value of zero (95 % CI [−0.370; −0.188]). However, FLE did not have any significant indirect influence on WTC (β = −0.057; n.s). Regarding total effects, the effect of shame on WTC was found to be significant, indicating a large effect size (β = −0.639, 95 % CI: [−0.744, −0.526]). In the same vein, FLLB exerted a significant overall impact (β = −0.569, 95 % CI: [−0.698, −0.441]) with a large effect size on learner WTC.

5 Discussion

This study aimed to test a model of WTC in relation to learners’ shame, FLLB, and FLE in a blended language-learning setting. According to the results of SEM analysis, first, it was discovered that shame had a direct, negative, and significant influence on the WTC, hence confirming H1. These results align with Teimouri’s (2018) findings, which indicate a significant and negative link between shame and WTC. The results of this study provide evidence that aligns with Galmiche’s (2017) assertion that shame has a detrimental effect on the motivation of second language learners to utilize the second language. It would thus appear that the negative role of WTC can help explain students’ reluctance to engage in classroom activities in general and activities that involve communication because of their proneness to experience shame.

Second, the current study found that boredom has a direct, negative, and significant impact on WTC. The quantitative analyses provided evidence of a significant negative effect of FLLB on WTC, thus confirming hypothesis H3. Participants who experienced higher levels of boredom throughout the online language learning lesson demonstrated a decreased probability of participating in communication using the target language. Given that FLLB is typically defined as a condition of disconnection or disengagement (Pawlak et al. 2020) and active involvement and conversation in the class are seen as means of engagement and learning, it is not surprising that there is a negative correlation with WTC. This finding corroborates the results of Fattahi et al.’s (2023) research, which indicated a negative association between FLLB and WTC in an online environment.

Unexpectedly, the SEM model indicated that enjoyment was not a predictor of WTC, rejecting H5. This finding contradicts previous research that has consistently shown the significant role of FLE as a predictor of WTC (e.g., Boudreau et al. 2018; Fathi et al. 2023; Lee 2020; Lee et al. 2022). Prior research has suggested that a strong sense of enjoyment in the language learning process is an essential requirement for second language learners to exhibit a willingness to communicate in the target language (MacIntyre et al. 2019). The above-mentioned finding is partially in contrast with PP principles and the broaden-and-build theory of emotions, which argue that positive emotions lead to and foster other positive emotions. However, in the present study, FLE could not predict WTC, as a positive language learning outcome. Unlike the present research, several investigations have identified FLE as a significant factor in predicting WTC (Alrabai 2024; Li et al. 2022; Wang et al. 2021). A potential explanation for this atypical discovery could be attributed to the specific circumstances of the language learning classroom in this research-instruction did not occur in a traditional face-to-face environment, which was a new experience for all students. A large number of students who experienced blended learning tended to prefer the in-class mode of learning since it was linked to in-class lessons with heightened motivation and increased interest (Wright 2017). This connection was attributed to better comprehension, the appreciated interaction within the classroom involving the lecturer and peers, and the valuable input received from the instructor (Owston et al. 2019). According to Fathi et al. (2023), students expressed dissatisfaction with the absence of in-person teaching and the unstimulating environment of online classrooms, which led to unpleasant feelings. Furthermore, in the context of blended learning, students perceived teachers as the primary source of authority in the learning process (Pei et al. 2024). This dynamism put pressure on the student-teacher relationship and raised doubts about the effectiveness of digital tools in facilitating complex and in-depth discussions (Pei et al. 2024). The presence of such an atmosphere may diminish students’ experience of pleasure, as seen by reduced social enjoyment resulting from interactions with teachers and peers (Botes et al. 2021). The absence of social connection inherent in this context, along with the limited opportunities for face-to-face exchanges, may have resulted in a diminished influence of enjoyment and an amplified impact of boredom. Hence, the integration of blended learning increased the possibility of student disengagement, withdrawal from learning, and boredom, while simultaneously decreasing the probability of experiencing delight. These factors, together, led to a reduced desire to communicate in the target language.

The analysis not only identified the direct effects of the variables being studied but also uncovered their indirect effects on WTC. Firstly, our study demonstrated that shame had an impact on WTC through the influence of FLLB, thereby confirming H2. This suggests that learners, who are more prone to have a sense of shame are more likely to experience FLLB, supporting H4, which causes them to refrain from engaging in communication. Similarly, boredom affected WTC via the mediation of shame. These findings suggest the strong effect of negative emotions, which tend to neutralize positive emotions, namely enjoyment, as suggested by Bensalem 2022. Specifically, the simultaneous impact of boredom, a frequently encountered emotion among students (Pekrun et al. 2010), and shame, a pervasive emotion (Teimouri 2018), undermines students’ pleasure and leads to their unwillingness to communicate in the target language.

5.1 Implications

In the current study, we found that shame and FLLB influenced the WTC of college students in a hybrid learning environment. Such findings have implications for foreign language instructors. Given the fact that shame can be debilitating and contribute to students’ involvement in communication, language teachers should strive to devise appropriate strategies to help eliminate or alleviate shame triggers. They need to be attentive to students’ facial expressions who may be either frustrated or not fully comprehending. These students need to be approached quietly, assessed for their understanding, and reassured. In addition, instructors should avoid grouping lower-achieving students together since that can lead to exposure to students’ weaknesses – a trigger of shame. In this regard, according to Marzano et al. (2001), ability grouping can have detrimental effects on students if not done properly. Marzano et al. (2001) posit that effective learning groups should encompass specific elements. These include the active involvement of every group member, the assignment of valid roles with clearly defined standards, individual and collective investment in task completion or learning goals, and shared accountability among all group members. Building shame resilience is not an easy task, but instructors should try to avoid triggering shameful incidents, which can make it much harder for students to surmount the experience. Instructors should establish a safe learning environment where students are continuously reminded of what could be successful. Expressions such as “you can do it, you make a difference” are important countermeasures to shame.

Another implication is to raise awareness among instructors about the detrimental effects of boredom, which is not always caused by learners’ laziness but rather by the classroom environment (Pawlak et al. 2020). Teachers should design meaningful activities that allow students to communicate with their classmates in the target language. These activities have to involve real-life situations that students enjoy. Li (2021) suggests offering learners the autonomy to choose activities and discussion topics, thereby avoiding tasks that are either overly challenging or insufficiently challenging. Furthermore, employing stimulating online games and activities that elicit feelings of accomplishment and satisfaction (Cavanagh 2016) can serve as an effective approach to alleviate the effects of boredom among students. Finally, teachers could enhance their computer literacy to mitigate disruptions related to information technology in the classroom, as recommended by Derakhshan et al. (2021).

6 Conclusion, limitations, and future directions

Based on the results of this study it can be claimed that learners’ emotions play a critical role in shaping their communication behavior. Moreover, the unexpected finding regarding the non-significant role played by FLE on students WTC indicates that the combination of two strong negative emotions, such as shame and boredom, may contribute to depriving students of enjoyment in their language classes. Therefore, the role of instructors is instrumental in mitigating the detrimental effects of negative emotions and helping students enjoy their language learning journey. Like other studies, the present investigation had some limitations. Firstly, the use of quantitative self-report scales may not effectively capture respondents’ true levels of a certain concept, which could undermine the reliability of the collected data. Therefore, it may be necessary to conduct more research that includes qualitative data in order to gain a more detailed knowledge of the connections between the examined variables. Furthermore, the data for the study were collected exclusively from a single university inside a particular country, which restricts the applicability of the findings to other multilingual contexts. In addition, the study did not account for the participants’ proficiency level, which could limit the generalizability of the findings. Hence, it is advisable to conduct more iterations of the research in different settings, using larger groups of students who possess varying degrees of skill in the target language. The longitudinal and dynamic interplay of the four constructs is also an interesting line of research in the future. Finally, future researchers are recommended to test the extracted model in other contexts and in light of innovative approaches to the study of emotions including retrodicitve qualitative modeling, latent profile analysis, time-series analysis, complexity theory, and the idiodynamic method.

Funding source: Deanship of Scientific Research, Northern Border University

-

Research ethics: The researchers got an approval from appropriate institutions prior to conducting this study.

-

Informed consent: All subjects gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

-

Research funding: This study is funded by the deanship of scientific research at Northern Border University, Arar, Saudi Arabia.

-

Data availability: The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

References

Alrabai, F. 2024. Modeling the relationship between classroom emotions, motivation, and learner willingness to communicate in EFL: Applying a holistic approach of positive psychology in SLA research. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 45(7). 2465–2483. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2022.2053138.Suche in Google Scholar

Barabadi, E., G. H. Khajavy, J. R. Booth, M. Rahmani Tabar & M. R. Vahdani Asadi. 2022. The links between perfectionistic cognitions, L2 achievement and willingness to communicate: Examining L2 anxiety as a mediator. Current Psychology 42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-04114-7.Suche in Google Scholar

Barrios, E. & I. Acosta-Manzano. 2025. Factors predicting classroom WTC in English and French as foreign languages among adult learners in Spain. Language Teaching Research 29(1). 88–111. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688211054046.Suche in Google Scholar

Bensalem, E., A. S. Thompson & F. Alenazi. 2023. The role of grit and enjoyment in EFL learners’ willingness to communicate in Saudi Arabia and Morocco: A cross-cultural study. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 46. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2023.2200750.Suche in Google Scholar

Bensalem, E. 2022. The impact of enjoyment and anxiety on English-language learners’ willingness to communicate. Vivat Academia 155. 91–111. https://doi.org/10.15178/va.2022.155.e1310.Suche in Google Scholar

Bensalem, E., A. Derakhshan, F. H. Fahad Hamed Alenazi, A. S. Thompson & R. Harizi. 2025. Modeling the contribution of grit, enjoyment, and boredom to predict English as a foreign language students’ willingness to communicate in a blended learning environment. Perceptual and Motor Skills 132(1). 144–168. https://doi.org/10.1177/00315125241289192.Suche in Google Scholar

Bieleke, M., K. Gogol, T. Goetz, L. Daniels & R. Pekrun. 2021. The AEQ-S: A short version of the achievement emotions questionnaire. Contemporary Educational Psychology 65. 101940. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101940.Suche in Google Scholar

Blake, R. J. 2017. Technologies for teaching and learning L2 speaking. In C. A. Chapelle & S. Sauro (eds.), The handbook of technology and second language teaching and learning, 107–117. Washington, DC: John Wiley & Sons.10.1002/9781118914069.ch8Suche in Google Scholar

Botes, E., J.-M. Dewaele & S. Greiff. 2021. The development of a short-form foreign language enjoyment scale. The Modern Language Journal 105(4). 858–876. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12741.Suche in Google Scholar

Boudreau, C., P. D. MacIntyre & J.-M. Dewaele. 2018. Enjoyment and anxiety in second language communication: An idiodynamic approach. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching 8(1). 149–170. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2018.8.1.7.Suche in Google Scholar

Byrne, B. M. 2013. Structural equation modeling with AMOS. Hove (UK): Psychology Press.10.4324/9781410600219Suche in Google Scholar

Cavanagh, S. R. 2016. The spark of learning: Energizing the college classroom with the science of emotion. West Virginia, USA: West Virginia University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Chen, Y., Y. Zhi & A. Derakhshan. 2025. Integrating artificial intelligence (AI) into the English as a foreign language classroom: Exploring its impact on Chinese English students’ achievement emotions and willingness to communicate (WTC). European Journal of Education 60. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.70157.Suche in Google Scholar

Cook, T. 2006. An investigation of shame and anxiety in learning English as a second language. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Los Angeles, CA: University of Southern California.Suche in Google Scholar

Daniels, L. M., V. M. C. Tze & T. Goetz. 2015. Examining boredom: Different causes for different coping profiles. Learning and Individual Differences 37. 255–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2014.11.004.Suche in Google Scholar

Derakhshan, A. & J. Fathi. 2024. Longitudinal exploration of interconnectedness through a cross-lagged panel design: Enjoyment, anxiety, L2 willingness to communicate, and L2 grit in English language learning. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 46. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2024.2393705.Suche in Google Scholar

Derakhshan, A., M. Kruk, M. Mehdizadeh & M. Pawlak. 2021. Boredom in online classes in the Iranian EFL context: Sources and solutions. System 101. 102556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2021.102556.Suche in Google Scholar

Derakhshan, A., J. Fathi, M. Pawlak & M. Kruk. 2024. Classroom social climate, growth language mindset, and student engagement: The mediating role of boredom in learning English as a foreign language. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 45(8). 3415–3433. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2022.2099407.Suche in Google Scholar

Dewaele, J.-M. 2019. The effect of classroom emotions, attitudes toward English, and teacher behavior on willingness to communicate among English foreign language learners. Journal of Language and Social Psychology 38(4). 523–535. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X19864996.Suche in Google Scholar

Dewaele, J.-M. & L. Dewaele. 2018. Learner-internal and learnefr-external predictors of willingness to communicate in the FL classroom. Journal of the European Second Language Association 2(1). 24. https://doi.org/10.22599/jesla.37.Suche in Google Scholar

Dewaele, J. M. & C. C. Li. 2021. Teacher enthusiasm and students’ social-behavioral learning engagement: The mediating role of student enjoyment and boredom in Chinese EFL classes. Language Teaching Research 25. 922–945. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688211014538.Suche in Google Scholar

Dewaele, J.-M. & P. D. MacIntyre. 2014. The two faces of Janus? Anxiety and enjoyment in the foreign language classroom. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching 4. 237–274. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2014.4.2.5.Suche in Google Scholar

Dewaele, J.-M. & P. D. MacIntyre. 2016. Foreign language enjoyment and foreign language classroom anxiety: The right and left feet of the language learner. In T. Gregersen, P. D MacIntyre & S. Mercer (eds.), Positive psychology in SLA, 215–236. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.10.2307/jj.30945667.12Suche in Google Scholar

Dewaele, J.-M. & L. M. Pavelescu. 2019. The relationship between incommensurable emotions and willingness to communicate in English as a foreign language: A multiple case study. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching 15(1). 66–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/17501229.2019.1675667.Suche in Google Scholar

Dewaele, J.-M., K. Saito & F. Halimi. 2022. How teacher behaviour shapes foreign language learners’ enjoyment, anxiety and attitudes/motivation: A mixed modelling longitudinal investigation. Language Teaching Research 29(4). 1580–1602. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688221089601.Suche in Google Scholar

Ebn-Abbasi, F., M. Nushi & N. Fattahi. 2022. The role of l2 motivational self system and grit in EFL learners’ willingness to communicate: A study of public school vs. private English language institute learners. Frontiers in Education 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.837714.Suche in Google Scholar

Elahi Shirvan, M., G. H. Khajavy, P. D. MacIntyre & T. Tahereh. 2019. A meta-analysis of L2 willingness to communicate and its three high-evidence correlates. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research 48. 1241–1267.10.1007/s10936-019-09656-9Suche in Google Scholar

Fathi, J., F. Mohammaddokht & S. Nourzadeh. 2021. Grit and foreign language anxiety as predictors of willingness to communicate in the context of foreign language learning: A structural equation modeling approach. Issues in Language Teaching 10(2). 1–30. https://doi.org/10.22054/ILT.2021.63362.627.Suche in Google Scholar

Fathi, J., M. Pawlak, S. Mehraein, H. M. Hosseini & A. Derakhshesh. 2023. Foreign language enjoyment, ideal L2 self, and intercultural communicative competence as predictors of willingness to communicate among EFL learners. System 115. 103067. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2023.103067.Suche in Google Scholar

Fattahi, N., F. Ebn-Abbasi, E. Botes & M. Nushi. 2023. Nothing ventured, nothing gained: The impact of enjoyment and boredom on willingness to communicate in online foreign language classrooms. Language Teaching Research 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688231194286.Suche in Google Scholar

Feng, E., C. Li, P. D. MacIntyre & J. M. Dewaele. 2025. Language attitude and willingness to communicate: A longitudinal investigation of Chinese young EFL learners. Learning and Individual Differences 118. 102639. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2025.102639.Suche in Google Scholar

Fredrickson, B. L. 2003. The value of positive emotions: The emerging science of positive psychology is coming to understand why it’s good to feel good. American Scientist 91. 330–335. https://doi.org/10.1511/2003.26.330.Suche in Google Scholar

Galmiche, D. 2017. Shame and SLA. Apples – Journal of Applied Language Studies 11(2). 25–53. https://doi.org/10.17011/apples/urn.201708233538.Suche in Google Scholar

Galmiche, D. 2018. The role of shame in language learning. Journal of Languages, Texts, and Society 2. 99–129.Suche in Google Scholar

Ghiasvand, F. & P. Sharifpour. 2024. “An L2 education without love is not education at all”: A phenomenographic study of undergraduate EFL students’ perceptions of pedagogical love. Asian-Pacific Journal of Second and Foreign Language Education 9(14). 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40862-023-00233-1.Suche in Google Scholar

Graham, C. R. 2013. Emerging practice and research in blended learning. In M. G. Moore (ed.), Handbook of distance education, 333–350. Cambridge: Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

Hair, J. F., M. Sarstedt, C. M. Ringle & J. A. Mena. 2012. An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 40. 414–433. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-011-0261-6.Suche in Google Scholar

Hayes, A. F. 2017. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression based approach. New York: Guildford Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Henry, A. & P. D. MacIntyre. 2023. Willingness to communicate, multilingualism and interactions in community contexts. Bristol: Channel View Publications.10.21832/HENRY1944Suche in Google Scholar

Hu, L. T. & P. M. Bentler. 1999. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 6. 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118.Suche in Google Scholar

Jiang, Y. & J.-M. Dewaele. 2019. How unique is the foreign language classroom enjoyment and anxiety of Chinese EFL learners? System 82. 13–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2019.02.017.Suche in Google Scholar

Jin, Y. & L. J. Zhang. 2019. A comparative study of two scales for foreign language classroom enjoyment. Perceptual and Motor Skills 126(5). 1024–1041. https://doi.org/10.1177/0031512519864471.Suche in Google Scholar

Jin, Y. & L. J. Zhang. 2021. The dimensions of foreign language classroom enjoyment and their effect on foreign language achievement. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 24. 948–962. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2018.1526253.Suche in Google Scholar

Khajavy, G. H., B. Ghonsooly, A. Hosseini & C. W. Choi. 2016. Willingness to communicate in English: A microsystem model in the Iranian EFL classroom context. Tesol Quarterly 50(1). 154–180. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.204.Suche in Google Scholar

Khajavy, G. H., P. D. MacIntyre & E. Barabadi. 2018. Role of the emotions and classroom environment in willingness to communicate. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 40(3). 605–624. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0272263117000304.Suche in Google Scholar

Kruk, M. 2022. Dynamicity of perceived willingness to communicate, motivation, boredom and anxiety in second life: The case of two advanced learners of English. Computer Assisted Language Learning 35(1–2). 190–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2019.1677722.Suche in Google Scholar

Kruk, M. & J. Zawodniak. 2018. Boredom in practical English language classes: Insights from interview data. In L. Szymański, J. Zawodniak, A. Łobodziec & M. Smoluk (eds.), Interdisciplinary views on the English language, literature and culture, 177–191. Zielona Góra: Uniwersytet Zielonogórski.Suche in Google Scholar

Kruk, M., M. Pawlak & J. Zawodniak. 2021. Another look at boredom in language instruction: The role of the predictable and the unexpected. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching 11(1). 15–40. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2021.11.1.2.Suche in Google Scholar

Kunnan, A. J. 1998. An introduction to structural equation modelling for language assessment research. Language Testing 15(3). 295–332. https://doi.org/10.1191/026553298675279428.Suche in Google Scholar

Lee, J. S. 2020. The role of grit and classroom enjoyment in EFL learners’ willingness to communicate. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 43(5). 452–468. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2020.1746319.Suche in Google Scholar

Lee, J. S. & N. A. Drajati. 2019. Affective variables and informal digital learning of English: Keys to willingness to communicate in a second language. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology 168–182. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.5177.Suche in Google Scholar

Lee, J. S. & J. C. Hsieh. 2019. Affective variables and willingness to communicate of EFL learners in in-class, out-of-class, and digital contexts. System 82. 63–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2019.03.002.Suche in Google Scholar

Lee, J. S., N. M. Yeung & M. B. Osburn. 2022. Foreign language enjoyment as a mediator between informal digital learning of English and willingness to communicate: A sample of Hong Kong EFL secondary students. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2022.2112587.Suche in Google Scholar

Lewis, M. 2019. The self-conscious emotions and the role of shame in psychopathology. In V. LoBue, K. Pérez-Edgar & K. A. Buss (eds.), Handbook of emotional development, 311–350. Nature Switzerland AG: Springer.10.1007/978-3-030-17332-6_13Suche in Google Scholar

Li, C. 2021. A control–value theory approach to boredom in English classes among university students in China. The Modern Language Journal 105(1). 317–334. Portico https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12693.Suche in Google Scholar

Li, C., J.-M. Dewaele, M. Pawlak & M. Kruk. 2022. Classroom environment and willingness to communicate in English: The mediating role of emotions experienced by university students in China. Language Teaching Research 29(5). 2140–2160. 136216882211116 https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688221111623.Suche in Google Scholar

Li, C., J.-M. Dewaele & Y. Hu. 2023. Foreign language learning boredom: Conceptualization and measurement. Applied Linguistics Review 14(2). 223–249. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2020-0124.Suche in Google Scholar

Lin, J. & Y. Wang. 2025. Exploring Chinese university students’ foreign language enjoyment, engagement and willingness to communicate in EFL speaking classes. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 12. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04948-z.Suche in Google Scholar

MacIntyre, P., R. Clement, Z. Dornyei & K. Noels. 1998. Conceptualizing willingness to communicate in a L2: A situational model of L2 confidence and affiliation. The Modern Language Journal 82. 545–562. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.1998.tb05543.x.Suche in Google Scholar

MacIntyre, P. D., T. Gregersen & S. Mercer. 2019. Setting an agenda for positive psychology in SLA: Theory, practice, and research. The Modern Language Journal 103(1). 262–274. Portico https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12544.Suche in Google Scholar

MacIntyre, P. D., T. Gregersen & S. Mercer. 2020. Language teachers’ coping strategies during the Covid-19 conversion to online teaching: Correlations with stress, wellbeing and negative emotions. System 94. 102352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2020.102352.Suche in Google Scholar

MacIntyre, P., A. Panahi & H. Mohebbi. 2025. Peter D. Macintyre’s 35-year research contribution to psychology, language education and communication: A systematic review. Language Teaching Research Quarterly 48. 297–336. https://doi.org/10.32038/ltrq.2025.48.18.Suche in Google Scholar

Marzano, R. J., D. J. Pickering & J. E. Pollock. 2001. Classroom instruction that works: Research-based strategies for increasing student achievement. Alexandria: ASCD.Suche in Google Scholar

McCroskey, J. C. 1992. Reliability and validity of the willingness to communicate scale. Communication Quarterly 40. 16–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/01463379209369817.Suche in Google Scholar

McCroskey, J. C. & J. E. Baer. 1985. Willingness to communicate: The construct and its measurement. Paper Presented at the Annual Convention of the Speech Communication Association, Denver, CO.Suche in Google Scholar

Mystkowska-Wiertelak, A. & M. Pawlak. 2017. Willingness to communicate in instructed second language acquisition: Combining a macro- and micro-perspective. Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.10.21832/9781783097173Suche in Google Scholar

Owston, R., D. N. York & T. Malhotra. 2019. Blended learning in large enrolment courses: Student perceptions across four different instructional models. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology 35. 29–45. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.4310.Suche in Google Scholar

Pawlak, M. & A. Mystkowska-Wiertelak. 2015. Investigating the dynamic nature of L2 willingness to communicate. System 50. 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2015.02.001.Suche in Google Scholar

Pawlak, M., M. Kruk & J. Zawodniak. 2020. Investigating individual trajectories in experiencing boredom in the language classroom: The case of 11 Polish students of English. Language Teaching Research 26(4). 598–616. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168820914004.Suche in Google Scholar

Pawlak, M., A. Derakhshan, M. Mehdizadeh & M. Kruk. 2025. Boredom in online English language classes: Mediating variables and coping strategies. Language Teaching Research 29(2). 509–534. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688211064944.Suche in Google Scholar

Pei, L., C. Poortman, K. Schildkamp & N. Benes. 2024. Teachers’ and students’ perceptions of a sense of community in blended education. Education and Information Technologies 29. 2117–2155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-023-11853-y.Suche in Google Scholar

Pekrun, R., T. Goetz, L. M. Daniels, R. H. Stupnisky & R. P. Perry. 2010. Boredom in achievement settings: Exploring control–value antecedents and performance outcomes of a neglected emotion. Journal of Educational Psychology 102(3). 531–549. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019243.Suche in Google Scholar

Pekrun, R., T. Goetz, A. C. Frenzel, P. Barchfeld & R. P. Perry. 2011. Measuring emotions in students’ learning and performance: The achievement emotions questionnaire (AEQ). Contemporary Educational Psychology 36(1). 36–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2010.10.002.Suche in Google Scholar

Putwain, D. W. & M. Pescod. 2018. Is reducing uncertain control the key to successful test anxiety intervention for secondary school students? Findings from a randomized control trial. School Psychology Quarterly 33(2). 283–292. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000228.Suche in Google Scholar

Shrout, P. E. & N. Bolger. 2002. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods 7(4). 422–445. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.7.4.422.Suche in Google Scholar

Solhi, M., A. Derakhshan, M. Pawlak & B. Ünsal. 2024. Exploring the interplay between EFL learners’ L2 writing boredom, writing motivation, and boredom coping strategies. Language Teaching Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688241239178.Suche in Google Scholar

Solhi, M., A. Derakhshan & B. Ünsal. 2025. Associations between EFL students’ L2 grit, boredom coping strategies, and regulation strategies: A structural equation modeling approach. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 46(2). 224–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2023.2175834.Suche in Google Scholar

Teimouri, Y. 2017. L2 selves, emotions, and motivated behaviors. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 39(4). 681–709. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263116000243.Suche in Google Scholar

Teimouri, Y. 2018. Differential roles of shame and guilt in L2 learning: How bad is bad? The Modern Language Journal 102(4). 632–652. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12511.Suche in Google Scholar

Tonidandel, S. & J. M. LeBreton. 2011. Relative importance analysis: A useful supplement to regression analysis. Journal of Business and Psychology 26(1). 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-010-9204-3.Suche in Google Scholar

Tucker, L. R. & C. Lewis. 1973. A reliability coefficient for maximum likelihood factor analysis. Psychometrika 38. 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02291170.Suche in Google Scholar

Wang, Y. 2023. Probing into the boredom of online instruction among Chinese English language teachers during the Covid-19 pandemic. Current Psychology. 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-04223-3.Suche in Google Scholar

Wang, H., A. Peng & M. M. Patterson. 2021. The roles of class social climate, language mindset, and emotions in predicting willingness to communicate in a foreign language. System 99. 102529. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2021.102529.Suche in Google Scholar

Weaver, C. 2005. Using the Rasch Model to develop a measure of second language learners’ willingness to communicate within a language classroom. Journal of Applied Measurement 6. 396–415.Suche in Google Scholar

Wei, X. & Q. Xu. 2021. Predictors of willingness to communicate in a second language (L2 WTC): Toward an integrated L2 WTC model from the socio‐psychological perspective. Foreign Language Annals 55(1). 258–282. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12595.Suche in Google Scholar

Wright, B. M. 2017. Blended learning: Student perception of face-to-face and online efl lessons. Indonesian Journal of Applied Linguistics 7(1). 64. https://doi.org/10.17509/ijal.v7i1.6859.Suche in Google Scholar

Yashima, T. 2021. Willingness to communicate in an L2. The Routledge Handbook of the Psychology of Language Learning and Teaching. 260–271. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429321498-23.Suche in Google Scholar

Ye, X. & G. Hu. 2025. Effects of motivational interventions on EFL learners’ willingness to communicate, self-confidence, and anxiety: An experimental study. Language Teaching Research. 13621688251367858. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688251367858.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.