Abstract

The study aimed to address a research gap pertaining to establishing the role of personality traits in foreign language learning. Particularly, the aim of this paper was to examine the link between the personality trait of Conscientiousness and the L2 willingness to communicate, when mediated by language anxiety, and moderated by gender. The participants were 590 secondary school students whose responses to a questionnaire allowed to test a moderated mediation model, assessing language anxiety as a mediator, and gender as a moderator in the Conscientiousness-L2 WTC link. The established results suggest that the positive link between Conscientiousness and L2 WTC is slightly weakened with the mediation of language anxiety, being negatively related to language anxiety, that, in turn, negatively predicts L2 WTC. Moreover, the link under consideration is strongly moderated by gender, which proves that conscientious females are more willing to communicate in a foreign language, in spite of the influence of language anxiety. This research can be regarded a significant step towards a better understanding of the direct and indirect effect of personality traits on FL-specific factors.

1 Introduction

Every individual is characterized by a specific way of thinking, behaving and feeling that constitute personality. In order to capture its complexity, a Big Five model has been proposed. According to it, every individual can be described on the spectrum of five broad, independent traits (dispositions): Openness to experience, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness and Neuroticism (OCEAN) (e.g., McCrae and Costa 2003). Conscientiousness is one of the Big Five traits we focus on in this study. According to its most popular definition, the personality trait of Conscientiousness is “socially prescribed impulse control that facilitates task-and goal-directed behavior, such as thinking before acting, delaying gratification, following norms and rules, and planning, organizing and prioritizing tasks” (John and Srivastava 1999: 121). For this reason, this personality trait is characterized by prioritizing non-immediate goals, such as the need for achievement and work commitment or dutifulness, as well as obeying rules, represented by moral thoroughness and carefulness (DeYoung 2015). It follows that highly conscientious individuals are demanding, righteous and self-disciplined. They also tend to be strong-minded, achievement-oriented and industrious, sometimes on the verge of ‘workaholism’ (Costa and McCrae 1992), as well as skilled in managing anxiety (Fan 2020). Conversely, the individuals low in Conscientiousness are regarded as careless, impulse-driven, unstable and lack self-discipline (McCrae and Costa 2003). Importantly, it is speculated that low levels of the trait are not only connected with negative self-perceptions, but also with a proneness to failures and poor coping that produce anxiety (Kotov et al. 2007).

In the academic domain, this personality trait is consistently viewed as the strongest predictor of academic performance, regardless of educational level (e.g., Theobald et al. 2018; Vedel and Poropat 2017). Conscientious students generally have better grades (Trautwein et al. 2015), and a better perception of abilities, leading to a positive attitude towards the specific subject, as well as an interest in it. They engage in effective academic behaviours – they put effort on their homework (Göllner et al. 2017), devote more time to studying, and follow deadlines (Tackman et al. 2017), demonstrating a positive attitude to school (Denissen et al. 2007). As far as gender is concerned, it is argued that in spite of similar levels of cognitive ability in men and women, females tend to demonstrate higher levels of Conscientiousness (e.g., Iimura and Taku 2018; Mac Giolla and Kajonius 2019). They have a greater inclination to value perfectionism, and score higher on the measures of order, self-discipline and dutifulness (Varanarasama et al. 2019). This difference is mainly attributed to biological (innate sex differences) and social-psychological causes (social expectations pertaining to the social roles) (Verbree et al. 2022). It is generally argued that as the trait seems important for maintaining positive interpersonal relationships, it may therefore be more evolutionally pronounced in females than in males (Iimura and Taku 2018).

Also, in the area of foreign language learning the benefits of Conscientiousness have been confirmed, mostly due to the fact that the hard work embedded in the trait is firmly related to a strong sense of competence, which appears to be especially important in language learning (Furnham et al. 2011). It follows that higher levels of the trait generally allow conscientious students to achieve more in the SLA field (Novikova et al. 2020), as they effectively acquire foreign language writing, reading, grammar, and spelling (Piechurska-Kuciel 2018), as revealed in their grades in English as a foreign language (Meyer et al. 2019). It follows that thanks to their planned and structured behaviour positively impacting the acquisition of FL skills, conscientious students also effectively manage their negative affect (Javaras et al. 2012). They experience lower levels of speaking anxiety (Babakhouya 2019; Vural 2019), and, consequently, greater levels of speaking confidence (Khany and Ghoreyshi 2013).

A factor of great importance for the development of FL proficiency is L2 willingness to communicate (WTC), often conceptualized as “a readiness to enter into discourse at a particular time with a specific person or persons, using a L2” (MacIntyre et al. 1998: 547). It needs to be borne in mind that foreign language communication, requiring the use of a language that has not been fully mastered, induces a growing number of negative experiences, and significantly limits the spontaneity embedded in the volitional character of interpersonal communication. For this reason, L2 WTC can be conceptualized as a language-specific phenomenon, operating across various timescales, viewed from dynamic (state) and trait-like perspectives (Henry et al. 2024). For the purpose of this paper, L2 WTC is viewed as a stable (trait-like) inclination to communicate in the foreign language, that is formed over time in the context of formal education. As proposed in the pyramid model of L2 WTC (MacIntyre et al. 1998), it is formed by a variety of influential factors of a proximal (e.g., desire to communicate and communicative self-confidence) and distal nature (e.g., intergroup climate and personality). Contrary to proximal influences, personality represents long-term, stable processes whose effects are partly established a prori, due to heredity (MacIntyre 2020). It operates in the background, exerting a distal and subtle influence on the communication in the foreign language.

The empirical research on L2 WTC as a particularly prominent variable underlying L2 use (see the pyramid model; MacIntyre et al. 1998) appears to confirm this claim to a great extent (e.g., MacIntyre et al. 1998 Shirvan et al. 2019). Viewed from the trait-like perspective, it has been demonstrated that L2 WTC facilitates foreign language use (Lee et al. 2022), helping students cultivate their communicative competence (Chen et al. 2022), as well as communicative confidence (Alrabai 2022). The concept in question also shows significant links to a variety of cultural, political, social, identity, motivational, emotional, and pedagogical issues (MacIntyre 2020). These include aspects of L2 motivation (Lao 2020), such as the ideal L2 self, that strongly predict L2 WTC due to its focus on an ideal image of a skilled language speaker (Shen et al. 2020; Teimouri 2017). Among other factors, the most influential are negative and positive emotions which underlie the psychological background for the FL use. A significant string of research has confirmed the negative relationship between L2 WTC and language anxiety (e.g., Kalsoom et al. 2020; Zhou et al. 2023). On the other hand, the positive affect, as represented by foreign language enjoyment is positively related to L2 WTC (Sadoughi and Hejazi 2023). It allows students to willingly participate in classroom interaction (Cao 2022), through neutralizing the negative effect of language anxiety (Bensalem 2022). As far as personality is concerned, a positive, though weak, relationship of Conscientiousness and L2 willingness to communicate has been detected, with the reservation that this personality trait holds no predictive power for the readiness to communicate in the foreign language (Šafranj and Katić 2019). It stands in opposition to the findings of Adelifar et al. (2016), who conclude that people with a great desire toward progress, discipline, responsibility and success focus on their own personal development, abstaining from communicating with others. Moreover, also no relationship between L2 WTC and Conscientiousness has been detected (Zohoorian et al. 2022). Finally, it appears that gender is a significant predictor of L2 WTC, with females who are more willing to communicate in the foreign language due to their positive attitudes, alongside various social and cultural stereotypes (Yetkin and Özer 2022). Nevertheless, certain qualitative, gender-specific differences have also been found, according to which females are willing to communicate with a focus on meaningfulness, and males – on competence (Amiryousefi 2018).

Language anxiety (LA) is another factor of great significance in the context of foreign language learning. It is conceptualized as “a distinct complex of self-perceptions, beliefs, feelings, and behaviours arising from the uniqueness of the language learning process” in the classroom (Horwitz et al. 1986: 27). The unique situation of learning a foreign language induces the activation of specific anxiety that significantly disrupts the quality and quantity of the SLA process. Repeated occurrences of anxiety taking place at the onset of the FL learning process have a tendency to solidify into a situational-specific anxiety (MacIntyre and Gardner 1989). Hence, this form of anxiety includes features of state anxiety (a response to an anxiety-producing stimulus), as well as trait anxiety (a relatively stable personality characteristic demonstrated as anxiety proneness) (Spielberger 2010). However, according to a recent meta-analysis, language anxiety should be treated more like a trait-like than state-like concept due to its stable nature that may vary with foreign languages, but not with age (Drakulić 2015) or measuring scales (Hsiao and Tseng 2022). The original theoretical model of anxiety views it as a product of three universal types of performance anxieties: communication apprehension, test anxiety and a fear of negative evaluation (Horwitz et al. 1986). Nevertheless, language anxiety cannot be treated as a sum of its parts, but as an independent construct, coupling performance concerns with distress of being unable to be authentic due to linguistic limitations (Horwitz 2017). Under the influence of anxiety, students fall victims to uncurbed worry over a looming fiasco, excessive distress about others’ opinion, and self-evaluation (Dewaele 2013). Other cognitive effects include diminishing enthusiasm and motivation, together with weakening one’s will to communicate in the foreign language (Piechurska-Kuciel 2008). Altogether, the negative effects of language anxiety are found to be numerous in relation to various aspects of student functioning, such as language learning and achievement. According to a recent meta-analysis that examined the variable measured with various instruments, the link between language anxiety and academic achievement in foreign language courses is moderately negative in reference to general and skill-specific achievement (Botes et al. 2020; Teimouri et al. 2019; Zhang 2019). Altogether, the link between anxiety and language achievement is found to be moderate with language anxiety accounting for learners’ performance by about 10–15 % (Hsiao and Tseng 2022). On the other hand, there are studies proving no effect between language anxiety and academic results (Tóth 2021).

As to the association of language anxiety and Conscientiousness, some studies confirm the link between the two variables, demonstrating the effectiveness of the trait in managing language anxiety (Bialayesh et al. 2017; Fan 2020; Lahuerta 2014). However, contradictory findings are also proposed, demonstrating that high Conscientiousness is related to high language anxiety (Gargalianou et al. 2015), as is also demonstrated in the case of perfectionism (Gregersen and Horwitz 2002). This research ambiguity is further augmented by study findings doubting the existence of this relationship (e.g., Hussain et al. 2022). As far as the link between language anxiety and gender is concerned, no effect is found (Marx 2019; Rabadi and Rabadi 2022; Wang and Zhang 2021). This finding is confirmed by a meta-analysis carried out by Piniel and Zólyomi (2022), who conclude that in spite of the female tendency to declare higher levels of language anxiety, gender does not play a significant role shaping the variable. In spite of that, significant gender differences are still reported (Bensalem 2019; Dewaele et al. 2016; Inada 2021; Piechurska-Kuciel 2012).

2 Research rationale

The main aim of the study is to investigate the links between Conscientiousness and L2 willingness to communicate, as mediated by language anxiety. An additional focus is to include the role of gender in controlling the focal relationship.

Our research was guided by several hypotheses. First, we speculated that Conscientiousness was positively connected with L2 willingness to communicate (H1), owing to the theoretical grounding of L2 WTC, whereby a distal influence of personality on L2 use immediately preceded by L2 WTC is speculated (MacIntyre et al. 1998). Conscientious individuals are hard-working and well-organized (Jackson et al. 2010), which means that their industriousness and self-discipline may be helpful in attaining higher proficiency levels in the lengthy process of foreign language learning. Consequently, their higher achievement, confirmed by several studies (e.g., Meyer et al. 2019; Novikova et al. 2020; Piechurska-Kuciel 2018) may be helpful in gaining higher levels of L2 WTC, as demonstrated in the study by Šafranj and Katić (2019).

In the same vein, we assumed that Conscientiousness was negatively related to language anxiety (H2.1). Our speculation was informed by the research on the positive effect of Conscientiousness on managing negative affect (Javaras et al. 2012), as well as on language anxiety (Fan 2020). The organization and discipline facets attributed to the trait may produce good study habits and a readiness to learn, that are in turn augmented by conscientious students’ metacognitive regulation, inducing their laboriousness, aspirations, energy, and determination (Öztürk 2021). Stamina, and self-regulation, beneficial for successful foreign language acquisition (He 2019; Jackson and Park 2019), may protect conscientious students from the anxiety produced by the risks embedded in the language learning process. At the same time, we predicted that language anxiety was negatively related to L2 WTC (H2.2). The experienced anxiety in the situation of communication in a foreign language causes an increase in the sense of failure probability or a sense of self-esteem threat due to focusing on the opinion of others towards oneself. This translates into a decrease in motivation to learn, and, in particular, to communicate in the foreign language (Botes et al. 2020; Dewaele 2013; Piechurska-Kuciel 2008; Teimouri et al. 2019; Zhang 2019).

Aside from that, we also expected that the LA levels would mediate the link between the trait and L2 WTC (H3). It has been proposed that personality traits do not impact foreign language-related phenomena directly, but through proximal constructs that are more closely related to behaviour (Ożańska-Ponikwia et al. 2020; Piechurska-Kuciel et al. 2024). For this reason, we believed that the influence of Conscientiousness on L2 WTC, even when inconspicuous, would be more consistently exposed by introducing into the equation a foreign language-specific construct of language anxiety. Its ties with Conscientiousness are not firmly established (Bialayesh et al. 2017; Fan 2020; Gargalianou et al. 2015), similarly to its links with another L2-specific construct, L2 WTC, that appear to be positive in terms of correlation (Šafranj and Katić 2019) or non-existent (Adelifar et al. 2016). For this reason, there is a need to clarify these relationships, positing that language anxiety attenuates the positive effects of Conscientiousness on L2 WTC.

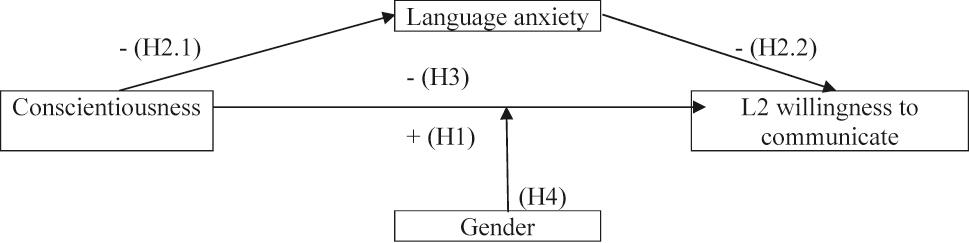

Finally, the impact of gender on the above relationship must be taken into consideration. It is hereby proposed that the higher levels of this personality trait attributed to females (e.g., Iimura and Taku 2018) may give way to their greater sensitivity to negative emotions (i.e., language anxiety), harnessing their L2 willingness to communicate (H4). Females outperform males in the academic domain owing to their behavioural tendencies that underpin Conscientiousness, which is a beneficial trait for educational success, and which is often favoured by teachers (Verbree et al. 2022). Apart from that, females reveal a tendency to be more willing to communicate in the foreign language (e.g., Inada 2021; Yetkin and Özer 2022). However, we believed that these strong advantages of females may fail when impacted by language anxiety that wreaks havoc with their effective language acquisition. Below, all the mentioned hypotheses are presented, together with Graph 1 that shows a model of the relationships hypothesized in this study.

Moderated mediation model for the relationship between Conscientiousness and L2 WTC with language anxiety as the mediator and gender as the moderator.

H1: Conscientiousness is positively connected with L2 willingness to communicate.

H2.1: Conscientiousness is negatively related to language anxiety.

H2.2: Language anxiety is negatively related to L2 WTC.

H3: LA mediates the link between Conscientiousness and L2 WTC.

H4: Conscientious females experience higher L2 WTC, even when under the influence of language anxiety.

3 Methods

3.1 Participants

The research cohort included 590 students (383 females and 207 males). They were recruited from 23 randomly selected classes of the six secondary grammar schools in Opole, an urban centre located in a Poland. Their age ranged from 18 to 21 (mean age: 18.50; SD = 0.53). Most of them lived in the city (N = 298; 50.5 %), one-third – in villages (N = 186; 31.5 %), and rest – in little towns (N = 106; 18.0 %). They attended the last grade of secondary education, with three to six h a week of compulsory English instruction. Their level of proficiency was intermediate to upper intermediate (the B1+ level of competence according to Common European Framework of Reference for Languages; CEFR). The participants reported learning English as their foreign language from two to nine years (Mean = 10.94; SD = 2.5). 30 % of them had been learning it up to 9 years, two-thirds declared learning it from ten to 12 years, and the remaining 20 % – from 13 to 19 years. Apart from English, they also studied another foreign language: German, French, Italian or Russian.

3.2 Instruments

The informants’ Conscientiousness was measured by means of the 20-item International Personality Item Pool representation of the Goldberg markers for the Big-Five factor structure, called the IPIP scale (Goldberg 1992). This scale was designed to assess individual differences in Conscientiousness, one of the five major dimensions of personality, which includes traits such as organization, diligence, and dependability. It consisted of 20 items (ten positively and ten negatively worded items, which were then key reversed). The answer format was a 5-point Likert scale, from 1 – strongly disagree to 5 – strongly agree. The minimum number of points on the scale was 20, while the maximum was 100, with higher scores indicating greater Conscientiousness. The scale’s reliability in this study was measured in terms of Cronbach’s alpha, ranging the level of α = 0.87, indicating strong internal consistency and suggesting that the scale effectively measures a coherent construct.

The L2 willingness to communicate was measured by means of two aggregated scales: Willingness to communicate in the classroom and Willingness to communicate outside the classroom (MacIntyre et al. 2001). These scales were selected due to their robust theoretical foundation and frequent use in second language acquisition research. They measured the students’ readiness to enter communication tasks in the classroom and outside school in the four skill areas by means of 54 items. The participants indicating how willing they would be to communicate in given contexts, from 1 – almost never willing, 2 – sometimes willing, 3 – willing half of the time, 4 – usually willing, to 5 – almost always willing. The minimum number of points was 27, while the maximum was 135, with higher scores indicating a higher level of willingness to communicate. Reliability analysis using Cronbach’s alpha confirmed a high level of internal consistency (α = 0.94), supporting the scale’s robustness in measuring WTC.

The Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety Scale (Horwitz et al. 1986) estimated the degree to which students felt anxious during language classes. This instrument assesses students’ anxiety levels related to language learning in classroom settings, covering aspects such as fear of negative evaluation, communication apprehension, and test anxiety. The Likert scale used ranged from 1 – I totally disagree to 5 – I totally agree. The minimum number of points was 33, the maximum was 165, with higher scores indicating greater anxiety. The scale’s reliability in this study was α = 0.94, confirming its suitability for assessing foreign language anxiety.

Additionally, sociodemographic variables (gender, age and place of residence) and the duration of foreign language learning were controlled, for potential confounding factors. These variables were included as they have been found in previous research to interact with both personality traits and second language acquisition variables (e.g., Piechurska-Kuciel 2014, 2018).

3.3 Procedure/analyses

The data collection procedure took place in the six grammar schools. After the schools’ headmasters had given their consent, the classes in which the research was to take place were randomly selected from the list of eligible classes (three to four in each school depending on availability). In each class, the students were informed about the purpose of the research and granted full confidentiality. They could withdraw from the study without any consequences, at any time. All the participants gave their oral consent and were then asked to fill in the questionnaire. The time given for the activity was 15–45 min. The participants were instructed to give sincere answers without taking excessive time to think. A short statement introducing a new set of items in an unobtrusive manner preceded each part of the questionnaire.

The data were analysed with IBM SPSS STATICTICS v.28. Descriptive analyses were conducted to determine the basic distribution and central tendency of the analysed variables. These analyses provided a foundational understanding of the levels of Conscientiousness, L2 Willingness to Communicate (WTC), and language anxiety among participants. The Central Limit Theorem applies for the various distinguished variables, so despite the lack of normal distribution, the Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to discover the initial relationships between the variables. Pearson’s r was preferred over non-parametric alternatives (such as Spearman’s rho) because it allows for greater interpretability in linear relationship assessments and is robust when applied to large datasets, even when normality assumptions are slightly violated. In order to verify the hypothesis about the connection between Conscientiousness and L2 WTC with the meditating role of language anxiety and moderating role of gender, the moderated mediation analysis using the PROCESS v3.2 macro (Hayes 2017) was performed. Mediation analysis was employed to explore the indirect effect of Conscientiousness on L2 WTC through language anxiety. The logic behind this analysis is that individuals high in Conscientiousness might experience less anxiety in foreign language learning contexts, which in turn might enhance their willingness to communicate. Moderation analysis was incorporated to determine whether the mediating effect of language anxiety differed by gender. Given that previous research suggests that males and females may experience language learning anxiety differently, testing for moderation allowed for a deeper understanding of whether the indirect effect of Conscientiousness on L2 WTC varied across gender groups. Moderated mediation integrates these two techniques, testing whether the strength of the mediation effect depends on the moderator (gender). This allowed us to assess not only the main effects but also the conditional processes governing these relationships. To estimate the direct, indirect and conditional effects, the bootstrap method was used for 5,000 trials; confidence intervals were bias corrected. This method was chosen because it does not rely on normality assumptions and provides bias-corrected confidence intervals, making it more suitable for complex models. A heteroscedasticity consistent standard error and covariance matrix estimator (HC3) was used. The HC3 estimator helps to increase the robustness of standard errors, reducing the risk of Type I and Type II errors. Independent variables were mean centred prior to analysis. The statistical significance was set at 0.05.

4 Results

The preliminary analysis of the results showed that gender does not differentiate the results obtained in terms of the link between Conscientiousness and WTC. However, there were statistically significant differences in the level of LA, where the females achieved significantly higher scores than the males. The effect obtained is strong (η2 = 0.30) (see Table 1 for details). Regarding the correlation between the included variables, the analysis showed a significant negative relationship between Conscientiousness and LA (r = −0.19) and a positive relationship with WTC (r = 0.17). This means that with greater Conscientiousness, anxiety levels decrease and WTC increases. It should be noted, however, that although the obtained relationships are significant, the effect is small. In the case of LA, the association with L2 WTC is significant and negative (r = −0.31), suggesting that L2 WTC decreases with increasing anxiety. When the gender of the respondents is taken into account, the results are slightly different. The relationship between conscientiousness and L2 WTC is no longer significant in the group of males (r = 0.11), while the relationship between LA and L2 WTC is twice as strong in the group of females than males (rF = −0.37 vs. rM = −0.18). Detailed data is presented in Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and relationships between the analyzed variables.

| Variable | Group | N | M (SD) | r (1) | r (2) | r (3) | Significance of differences between genders |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conscientiousness (1) | General | 590 | 73.37 (9.66) | – | −0.19*** | 0.17*** | t(588) = 0.88; p = 0.38; η2 = 0.08 |

| Male | 218 | 73.83 (10.48) | – | −0.15* | 0.11 | ||

| Female | 372 | 73.10 (9.15) | – | −0.20*** | 0.20*** | ||

| Language anxiety (2) | General | 590 | 81.02 (22.19) | −0.19*** | – | −0.31*** | t(588) = −3.51; p < 0.001; η2 = 0.30 |

| Male | 218 | 76.86 (20,91) | −0.15* | – | −0.18* | ||

| Female | 372 | 83.45 (22.59) | −0.20*** | – | −0.37*** | ||

| L2 willingness to communicate (3) | General | 494 | 162.12 (45.87) | 0.17*** | −0.31*** | – | t(492) = −0.105; p = 0.29; η2 = 0.09 |

| Male | 178 | 159.22 (44.27) | 0.11 | −0.18* | – | ||

| Female | 316 | 163.74 (46.74) | −0.20*** | −0.37*** | – |

-

M, mean; SD, standard deviation; r, Pearson’s coefficient level between variables; t, t-test result; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

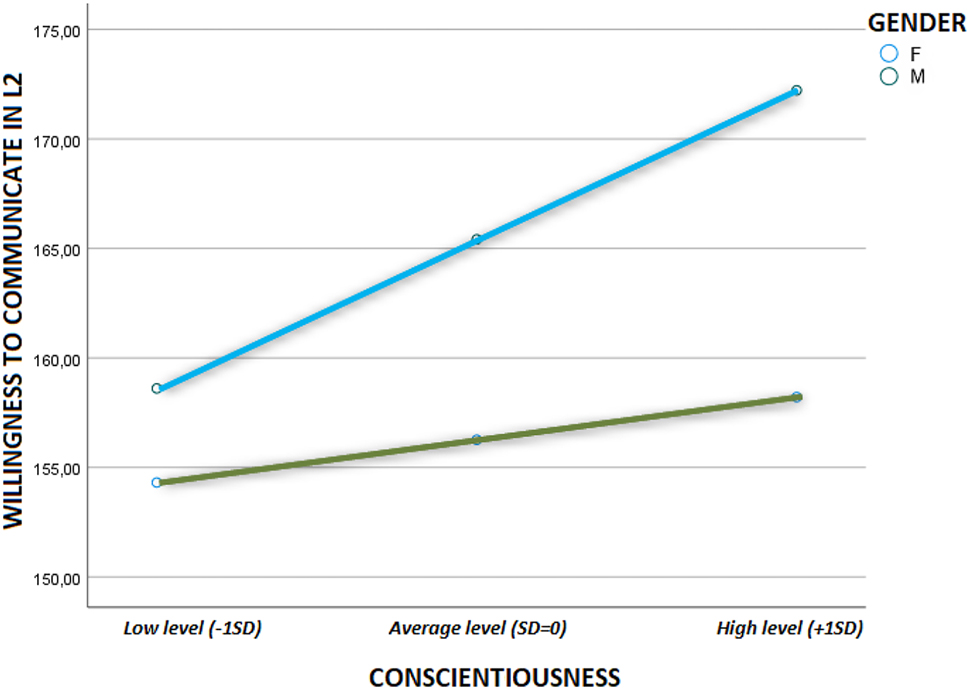

In order to verify the hypotheses resulting from the theoretical model (see Graph 1), moderated mediation was conducted, where Conscientiousness was the independent variable, L2 WTC was the dependent variable, LA was the mediator, and the gender of the respondents – the moderator of the relationship between Conscientiousness and L2 WTC. The analysis showed that a higher level of Conscientiousness is associated with a larger level of WTC (β = 0.16; t = 3.04; p < 0.01; path c in Table 2). This result confirms the assumptions resulting from Hypothesis 1 (H1). Moreover, Conscientiousness is a significant and negative predictor of language anxiety (β = −0.15; t = −3.04; p < 0.01; path a in Table 2) and that language anxiety is negatively associated with L2 WTC (β = −0.33; t = −6.87; p < 0.01; path b in Table 2). This means that with a greater level of Conscientiousness, LA decreases but at the same time, a larger level of LA significantly reduces the level of WTC. The obtained result confirms both hypotheses – H2.1 and H2.2. The mediating effect of language anxiety on the relationship between Conscientiousness and L2 WTC was also confirmed (H3), as adding LA to the model reduced the strength of the relationship between the variables (β = 0.11; t = 2.18; p < 0.05; path c′ in Table 2). The last verified hypothesis was the assumption that the gender of students moderates the relationship between Conscientiousness and L2 WTC (H4). The conducted analysis showed that although the interaction effect is statistically insignificant (β = 0.23; t = 1.03; p = 0.31; path X*W in Table 2), in the case of females a significant conditioned direct effect of Conscientiousness on the WTC is established (βF = 0.37; tF = 2.36; pF < 0.05 vs. βM = 0.05; tM = 51; pM = 0.61; see Table 2 and Graph 2). This result supports the hypothesis that gender moderates the relationship of Conscientiousness with L2 WTC (when language anxiety is also controlled), as females with higher levels of Conscientiousness also have a higher WTC, while for males, levels of Conscientiousness have no significant relationship with the L2 WTC. Detailed results of the analysis are presented in Table 2. The graph above represents the relationship between Conscientiousness and L2 WTC in reference to gender (Graph 2).

Conscientiousness and L2 WTC moderated mediation results.

| Model path | L2 willingness to communicate (N = 494) |

|---|---|

| X → M (a) | β = −0.15** CI: −0.63; −0.13 |

| M → Y (b) | β = −0.33*** CI: −0.85; −0.47 |

| X*W | β = 0.23 CI: −0.49; 1.55 |

| X → Y (c) | β = 0.16** CI: 0.28; 1.33 |

| X (M) → Y (c′) | β = 0.11* CI: 0.06; 1.05 |

| Indirect effect X on Y | β = 0.25 CI: 0.09; 0.45 |

| Conditional direct effect (a × b) × Wmales | β = 0.05 CI: −0.61; 1.04 |

| Conditional direct effect (a × b) × Wfemales | β = 0.37 CI: 0.13; 1.37 |

-

X, predictor (conscientiousness); M, mediator (language anxiety); W, moderator (gender); Y, willingness to communicate in the foreign language (L2 WTC); a–c′, paths; X*W, interaction between conscientiousness and gender (moderation indicator); β, standardized coefficients; CI, 95 % confidence intervals for unstandarized coeffitients *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Conditional direct effect of students’ gender in the Conscientiousness-L2 WTC relationship.

5 Discussion

The primary aim of this paper was to verify several hypotheses, focusing on the relationship between Conscientiousness and L2 willingness to communicate, when mediated by language anxiety, and controlled by gender.

According to the first hypothesis, Conscientiousness was positively related to L2 willingness to communicate (H1). Indeed, the theoretical relationship, though distal (MacIntyre et al. 1998), is confirmed empirically. The results of our study partly corroborate the findings of Šafranj and Katić (2019), demonstrating a weak correlation between the two variables. For this reason, it can be reliably maintained that the abilities encompassed by Conscientiousness (carefulness, diligence, compliance, stamina, deliberation, and self-discipline) induce a readiness to communicate in the foreign language. The decision to enter into a communicative act performed in a language that one has not mastered is often likened to ‘crossing the Rubicon’ (e.g., MacIntyre 2020). The clash between one’s perceived communicative abilities and fear of being judged induces a conflicted state of mind, consisting of being attracted to danger and pushed away from it at the same time. It thus follows that conscientious students are likely to make positive attributions about the effectiveness of their own abilities of dealing with the danger connected with communication in a foreign language. It is also revealed in the study that Conscientiousness can be treated as a positive predictor of L2 WTC, contrary to the study by Šafranj and Katić (2019), where no prediction was detected. However, the effect is quite small (β = 0.16**), which tends to be a regular occurrence in SLA studies (Dewaele 2012). The manifestations of the direct effects of personality traits on FL classroom behaviour may appear obscure or insignificant due to the change of language, which is responsible for the constant reorganization of the individual’s sense of self through an identity construction (Jang 2009), as well as the ambiguity embedded in the process of foreign language learning. Its significance is embedded in the centrality of the requirement to actively use the foreign language in spite of one’s limited proficiency, which produces “ambivalent states of mind” with students feeling both willing and unwilling to communicate (MacIntyre et al. 2011: 81). Understandably, defining the relationship between Conscientiousness and L2 WTC can constitute a reliable point of reference for explicating the role of personality traits in SLA.

As to the next, dual hypothesis, we speculated that Conscientiousness was negatively related to language anxiety (H2.1), and that language anxiety was negatively related to L2 WTC (H2.2). Both predictors turned out negative and significant, though the strength of the predictive value of Conscientiousness is smaller in comparison to that of language anxiety. Again, this can be explained in reference to the value of general (Conscientiousness) versus foreign language learning-specific factors (language anxiety). These findings demonstrate the role of emotions in the foreign language learning process. In the case of Conscientiousness, connected with a lower average level of negative affect (Komulainen et al. 2014), it can be deduced that the trait allows for an effective management of language anxiety, due to its links with the ability to create more positive achievement-related experiences (Ching et al. 2014), like perseverance despite the fears and anxieties experienced. It appears that the trait, connected with regulating internal urges and developing self-discipline, allows students to consciously manage their language learning process, together with controlling negative affect, as represented by language anxiety. As to the impact of this negative emotion on L2 willingness to communicate, its effect on the L2 willingness to communicate is unquestionably considerable, as substantiated empirically in a string of studies (e.g., Botes et al. 2020; Teimouri et al. 2019; Zhang 2019). This result can be ascribed to several factors. First of all, both tested factors are foreign language learning domain-specific, which allows for an adequate measuring of the range of effects. Aside from that, the activation of anxiety is likely to augment ambiguity connected with the feelings of being un-/willing to communicate in the foreign language, depriving learners of chances to practise their communication skills. At the same time, language anxiety decreases L2 self-confidence, an immediate predecessor of L2 WTC, interfering with language comprehension and production. In effect, under the influence of this negative emotion, when the student’s linguistic abilities and reliance on them are decreased, the natural reaction is to withdraw the decision to initiate communication.

Aside from studying the independent effects of Conscientiousness and language anxiety on L2 WTC, we hypothesised that language anxiety would mediate the personality trait-L2 WTC link (H3). The mediation, though quite weak, was confirmed, proving that the impact of Conscientiousness on L2 WTC is still significant, though slightly weakened by the inclusion of the impact of language anxiety on this relationship. These results are not surprising, as even well-organized and disciplined students, such as those characterised by higher levels of Conscientiousness who suffer from language anxiety, may fall victims to the impact of negative emotions. As proposed above, the impact of personality traits on language FL-related phenomena may be reliably assessed by means of the mediation of other domain-specific constructs (Ożańska-Ponikwia et al. 2020; Piechurska-Kuciel et al. 2024). The inclusion of language anxiety has enabled the role of Conscientiousness in shaping the L2 WTC to be consistently assessed, verifying inconsistent, to-date empirical results (e.g., Adelifar et al. 2016; Fan 2020; Šafranj and Katić 2019). The present study results firmly establish that the indirect effect of Conscientiousness on L2 WTC is considerable (β = 0.25), proving that personality traits exert an unwavering impact even on FL-specific behaviour. Altogether, the characteristics embedded in Conscientiousness (competence, order, dutifulness, achievement-striving, self-discipline and deliberation) are helpful in effective language acquisition, exposing the value of organization and discipline, stimulating the production of self-regulated learning, good study practices and a readiness to learn (Piechurska-Kuciel 2020; He 2019; Jackson and Park 2020). It follows that impulse control, identified with Conscientiousness, can be treated as a serious predictor of beneficial FL-related behaviour, captured by achievement striving and the drive to excel (Mike et al. 2015), enabling the student to reach long-term and rule-based goals. In this way students can perceive themselves as agents of their FL development, able to endure challenges and setbacks, as well as the emotional pitfalls created by ubiquitous language anxiety, leading to ultimate success in learning the foreign language.

Last, but not least, we speculated that the links between Conscientiousness and L2 WTC, when mediated by language anxiety, are gender dependent (H4). The results prove that significant differences between the genders are observed. In the case of males, no effect is observed, whereas in the case of females – a serious alteration can be noted. They not only declare significantly higher levels of Conscientiousness, but also those of L2 WTC, which supports the existing findings devoted to the link between gender and the personality trait (e.g., Mac Giolla and Kajonius 2019; Varanarasama et al. 2019), especially in reference to facets related to increased organization and diligence (Wehner and Schils 2021). This tendency also pertains to the link between gender and L2 WTC, demonstrating higher L2 WTC in females (e.g., Inada 2021; Yetkin and Özer 2022). Nevertheless, in spite of females generally being more sensitive to anxiety (Hantsoo and Epperson 2017), the conflicting results pertaining to gender differences in levels of language anxiety (e.g., Inada 2021; Piniel and Zólyomi 2022; Rabadi and Rabadi 2022) appear quite perplexing, and require clarification. The results of the present study consistently demonstrate the significance of gender in the mediated link between Consciousness and L2 WTC. Thanks to the moderated mediation analysis, more nuanced relationships can be investigated, providing an opportunity to investigate contingent and indirect effects at the same time (Edwards and Konold 2020). Thus, the main merit of this study consists in proving that conscientious females are more willing to communicate in a foreign language, even when experiencing language anxiety. In spite of our expectations, even the higher language anxiety levels declared by them do not exert a harmful impact on this relationship. This finding confirms the importance of gender and personality for the successful development of the foreign language learning process. This study area is generally described to be dominated by women, especially in Western countries (Slik et al. 2015), who display certain advantages for verbal and written language in childhood (Burman et al. 2008), and in their later years (Parsons et al. 2005). Although the research on sex differences in SLA is still inconclusive (Montero-SaizAja 2021), high Conscientiousness levels can be regarded as a game changer, playing the role of a solid foundation for female superiority in this domain.

The study is not free from limitations that need to be addressed. The biggest weakness can be attributed to the significantly reduced possibility of generalizing the results. This is mostly caused by the cross-sectional nature of the research that analyzed the questionnaire responses of the participants. Although such data is reliable and legitimate, it did not cater for triangulation. Moreover, the studied cohort came from a single geographical location. For this reason, caution is necessary when generalizing the results to various educational settings. Moreover, the application of moderated mediation also limits interpretations to non-causal inferences. Another study limitation may call for a less biased participant selection procedure. Most respondents were city dwellers, which might allow them for a fuller access to a range of facilities that might assist them in a successful foreign language development, as well as in a more effective management of language anxiety (Piechurska-Kuciel 2012). Last but not least, the foreign language under our scrutiny was English – the language with greatest popularity in secondary grammar school in the country, which might have influenced our results.

6 Final comments

Our findings, supporting some aspects of the previous research studies, suggest a certain mechanism through which the factors under consideration may be related; however, longitudinal research is needed to determine whether the direction of the correlations may differ from what is assumed in our theoretical model. Assisted by experimental and longitudinal perspectives, more varied and nuanced research designs would help to clarify the suggested causal pathways. Additionally, including qualitative data would certainly enrich the understanding of the role of personality traits in the field of foreign language learning, as well as help to triangulate data. As our study examines factors of a stable, trait-like nature, it would be interesting to investigate the longitudinal effects of personality traits over a longer period of time, such as the whole length of secondary school education, to establish a temporal precedence. Thanks to this approach, causal processes that relate selected predictors to clearly cut outcomes could be established.

Despite several limitations, our findings can be regarded as a significant step towards a better understanding of the direct and indirect effect of personality traits on FL factors. Conscientious students appeared to be willing to communicate in a foreign language. At the same time, they suffered from lower levels of language anxiety that significantly suppressed that willingness. Nevertheless, it was conscientious females, who appeared to resist the negative influence of language anxiety, and remained ready to initiate communication in a language they had not fully mastered. Consequently, several pedagogical implications of the research results may be envisaged. As language anxiety is yet again found to be a destructive force hampering the foreign language learning process, as widely confirmed in the literature of the field, the beneficial effects of Conscientiousness for L2 WTC also suffer from its negative influence. As many anxiety interventions have not yet been scientifically verified, it may be speculated that the primary indication for lowering language anxiety levels through arousing more positive emotions, like enjoyment, can be regarded mostly favourable (MacIntyre and Wang 2022). Another valuable finding exposes Conscientiousness as a significant factor protecting females’ willingness to communicate from negative effects of language anxiety. Obviously, gender is beyond any pedagogical interventions; nevertheless, an exciting path for pedagogical interventions is offered by the finding that Conscientiousness can be altered through cognitive behaviour therapy (Magidson et al. 2014). Such intervention might be quite challenging for most foreign language teachers; nevertheless, a conscious focus on developing skills and practices embedded in Conscientiousness, e.g., thoroughness, organization or diligence, may enable especially male students to develop a more responsible, and at the same time reliable approach to foreign language learning.

The results increase our understanding of the importance of being conscientious in the process of second language acquisition, especially in reference to gender. As “[b]eing willing to communicate is part of becoming fluent in a second language, which often is the ultimate goal” for those who aspire to master a foreign language (MacIntyre and Doucette 2010: 1), conscientious females seem to have more chances for eventual success. However, to end on a good note, levels of Conscientiousness could be refined by completing a sequence of tasks over a regulated period of time, even when the individual is not motivated to change (Hudson 2021). Thus, it can be inferred that, in spite of female superiority in the area of language learning, consistent pedagogical interventions are likely to make a difference for all students.

References

Adelifar, Maryam, Zachra Jafarzadeh, Gholamreza Abbasnejhad & Ahmadreza Shoa Hasani. 2016. The relationship between personality traits and WTC in EFL context. Journal of Studies in Social Sciences and Humanities 2(2). 45–54.Suche in Google Scholar

Alrabai, Fakieh. 2022. Teacher communication and learner willingness to communicate in English as a foreign language: A structural equation modeling approach. Saudi Journal of Language Studies 2(2). 45–67. https://doi.org/10.1108/SJLS-03-2022-0043.Suche in Google Scholar

Amiryousefi, Mohammad. 2018. Willingness to communicate, interest, motives to communicate with the instructor, and L2 speaking: A focus on the role of age and gender. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching 12(3). 221–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/17501229.2016.1170838.Suche in Google Scholar

Babakhouya, Youssef. 2019. The Big Five personality factors as predictors of English language speaking anxiety: A cross-country comparison between Morocco and South Korea. Research in Comparative and International Education 14(4). 502–521. https://doi.org/10.1177/17454999198947.Suche in Google Scholar

Bensalem, Elias. 2019. Multilingualism and foreign language anxiety: The case of Saudi EFL learners. Learning and Teaching in Higher Education: Gulf Perspectives 15(2). 47–60. https://doi.org/10.18538/lthe.v15.n2.314.Suche in Google Scholar

Bensalem, Elias. 2022. Impacto del disfrute y la ansiedad en la voluntad de comunicarse de los estudiantes del idioma inglés. Vivat Academia. Revista de Comunicación 155(2). 91–111. https://doi.org/10.15178/va.2022.155.e1310.Suche in Google Scholar

Bialayesh, Soraya, Alireza Homayoumi, Masoumeh Nasiri Kenari & Z. Shafian. 2017. Relationship between personality traits with language anxiety among bilinguals. European Psychiatry 41S(S406). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.01.334.Suche in Google Scholar

Botes, Eloisa, Jean-Marc Dewaele & Samuel Greiff. 2020. The foreign language classroom anxiety scale and academic achievement: An overview of the prevailing literature and a meta-analysis. Journal for the Psychology of Language Learning 2(1). 26–56. https://doi.org/10.52598/jpll/2/1/3.Suche in Google Scholar

Burman, Douglas D., Tali Bitan & James R. Booth. 2008. Sex differences in neural processing of language among children. Neuropsychologia 46(5). 1349–1364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.12.021.Suche in Google Scholar

Cao, Guihua. 2022. Toward the favorable consequences of academic motivation and L2 enjoyment for students’ willingness to communicate in the second language (L2WTC). Frontiers in Psychology 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.997566.Suche in Google Scholar

Chen, Xuemel, Jean-Marc Dewaele & Tiefu Zhang. 2022. Sustainable development of EFL/ESL learners’ willingness to communicate: The effects of teachers and teaching styles. Sustainability 14(1). 1 https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010396.Suche in Google Scholar

Ching, Charles M., A. Timothy Church, Marcia S. Katigbak, Jose Alberto S. Reyes, Junko Tanaka-Matsumi, Shino Takaoka, Hengsheng Zhang, Jiliang Shen, Rina Mazuera Arias, Brigida Carolina Rincon & Fernando A. Ortiz. 2014. The manifestation of traits in everyday behavior and affect: A five-culture study. Journal of Research in Personality 48. 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2013.10.002.Suche in Google Scholar

Costa, Paul T. & Robert R. McCrae. 1992. Manual for the revised NEO personality inventory (NEO-PIR) and NEO five-factor inventory (NEO-FFI). Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.Suche in Google Scholar

Denissen, Jaap J. A., Nicole R. Zarrett & Jacquelynne S. Eccles. 2007. I like to do it, i’m able, and I know I am: Longitudinal couplings between domain-specific achievement, self-concept, and interest. Child Development 78(2). 430–447. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01007.x.Suche in Google Scholar

Dewaele, Jean-Marc. 2012. Personality: Personality traits as independent and dependent variables. In Sarah Mercer, Stephen Ryan & Marion Williams (eds.), Psychology for language learning, 42–57. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.10.1057/9781137032829_4Suche in Google Scholar

Dewaele, Jean-Marc. 2013. The link between foreign language classroom anxiety and psychoticism, extraversion, and neuroticism among adult bi- and multilinguals. The Modern Language Journal 97(3). 670–684. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2013.12036.x.Suche in Google Scholar

Dewaele, Jean-Marc, Peter MacIntyre, Carmen Boudreau & Livia Dewaele. 2016. Do girls have all the fun? Anxiety and enjoyment in the foreign language classroom. Theory and Practice of Second Language Acquisition 2(1). 41–64.Suche in Google Scholar

DeYoung, Colin G. 2015. Cybernetic Big Five theory. Journal of Research in Personality 56. 33–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2014.07.004.Suche in Google Scholar

Drakulić, Morana. 2015. The ‘unforgettable’ experience of foreign language anxiety. Journal of Education, Culture and Society 6(1). 120–128. https://doi.org/10.15503/jecs20151.120.128.Suche in Google Scholar

Edwards, Kelly D. & Timothy R. Konold. 2020. Moderated mediation analysis: A review and application to school climate research. Practical Assessment, Research and Evaluation 25(1). https://doi.org/10.7275/16436623.Suche in Google Scholar

Fan, Jiayin. 2020. Relationships between five-factor personality model and anxiety: The effect of Conscientiousness on anxiety. Open Journal of Social Sciences 8(8). https://doi.org/10.4236/jss.2020.88039.Suche in Google Scholar

Furnham, Adrian, Eva Rinaldelli-Tabaton & Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic. 2011. Personality and intelligence predict arts and science school results in 16 year olds. Psychologia: An International Journal of Psychological Sciences 54(1). 39–51. https://doi.org/10.2117/psysoc.2011.39.Suche in Google Scholar

Gargalianou, Vasiliki, Katrin Muehlfeld, Diemo Urbig & Arjen Van Witteloostuijn. 2015. The effects of gender and personality on foreign language anxiety among adult multilinguals. Schumpeter discussion papers 2015-002, 1–40. Wuppertal: University of Wuppertal, Schumpeter School of Business and Economics.Suche in Google Scholar

Goldberg, Lewis R. 1992. The development of markers for the Big-Five factor structure. Psychological Assessment 4(1). 26–42. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.4.1.26.Suche in Google Scholar

Göllner, Richard, Rodica I. Damian, Norman Rose, Marion Spengler, Trautwein Ulrich, Benjamin Nagengast & Brent W. Roberts. 2017. Is doing your homework associated with becoming more conscientious? Journal of Research in Personality 71. 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2017.08.007.Suche in Google Scholar

Gregersen, Tammy & Elaine K. Horwitz. 2002. Language learning and perfectionism: Anxious and non-anxious language learners’ reactions to their own oral performance. The Modern Language Journal 86(4). 562–570. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-4781.00161.Suche in Google Scholar

Hantsoo, Liisa & C. Neill Epperson. 2017. Anxiety disorders among women: A female lifespan approach. Focus: Journal of Life Long Learning in Psychiatry 15(2). 162–172. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.focus.20160042.Suche in Google Scholar

Hayes, Anfrew F. 2017. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.Suche in Google Scholar

He, Tung-hsien. 2019. Personality facets, writing strategy use, and writing performance of college students learning English as a foreign language. Sagę Open 9(3). https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440198614.Suche in Google Scholar

Henry, Alastair, Cecilia Thorsen & Peter D. MacIntyre. 2024. Willingness to communicate in a multilingual context: Part two, person-context dynamics. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 45(4). 1033–1048. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2021.1935975.Suche in Google Scholar

Horwitz, Elaine K. 2017. On the misreading of Horwitz, Horwitz, and Cope (1986) and the need to balance anxiety research and the experiences of anxious language learners. In Christina Gkonou, Mark Daubney & Jean-Marc Dewaele (eds.), New insights into language anxiety, 31–47. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.10.2307/jj.22730706.6Suche in Google Scholar

Horwitz, Elaine K., Michael B. Horwitz & Joann Cope. 1986. Foreign language classroom anxiety. The Modern Language Journal 70(2). 125–132. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.1986.tb05256.x.Suche in Google Scholar

Hsiao, Tsung-Yuan & Wen-Ta Tseng. 2022. A meta-analysis of test-retest reliability in language anxiety research: Is language anxiety stable or variable? Sage Open 12(4). https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440221134619.Suche in Google Scholar

Hudson, Nathan W. 2021. Does successfully changing personality traits via intervention require that participants be autonomously motivated to change? Journal of Research in Personality 95. 104160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2021.104160.Suche in Google Scholar

Hussain, Wajid, Syeda Razia Bukhari, Zia Ullah, Anayat Ullah & Taraq Waheed Khan. 2022. The relationship between English language speaking anxiety and Big Five personality factors: A study of university students from the twin metropolitan cities of Pakistan. Journal of Positive School Psychology 6(8). 9897–9907.Suche in Google Scholar

Iimura, Shuhei & Kanako Taku. 2018. Gender differences in relationship between resilience and Big Five personality traits in Japanese adolescents. Psychological Reports 121(5). 920–931. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033294117741654.Suche in Google Scholar

Inada, Takako. 2021. Are there gender differences in anxiety and any other factors among English as a foreign language (EFL) college students in Japan? International Medical Journal 28(1). 90–93.Suche in Google Scholar

Jackson, Daniel O. & Simon Park. 2019. Self-regulation and personality among L2 writers: Integrating trait, state, and learner perspectives. Journal of Second Language Writing 49. 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2020.100731.Suche in Google Scholar

Jackson, Joshua J., Dustin Wood, Bogg Tim, Kate E. Walton, Peter D. Harms & Brent W. Roberts. 2010. What do conscientious people do? Development and validation of the behavioral indicators of conscientiousness (BIC). Journal of Research in Personality 44(4). 501–511. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2010.06.005.Suche in Google Scholar

Jang, Eun-Young. 2009. A window on identity: Diary study for understanding English language learners’ identity construction. English teaching 64(3). 53–78. https://doi.org/10.15858/engtea.64.3.200909.53.Suche in Google Scholar

Javaras, Kristin N., Stacey M. Schaefer, Carien M. van Reekum, Regina C. Lapate, Lawrence L. Greischar, David R. Bachhuber, Gayle Dienberg Love, Carol D. Ryff & Richard J. Davidson. 2012. Conscientiousness predicts greater recovery from negative emotion. Emotion 12(5). 875–881. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028105.Suche in Google Scholar

John, Oliver P. & Sanjay Srivastava. 1999. The Big Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. In Lawrence A. Pervin & Oliver P. John (eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research, 2nd edn., 102–138. New York: Guilford Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Kalsoom, Ammara, Niaz Hussain Soomro & Zahid Hussain Pathan. 2020. How social support and foreign language anxiety impact willingness to communicate in English in an EFL classroom. International Journal of English Linguistics 10(2). https://doi.org/10.5539/ijel.v10n2p80.Suche in Google Scholar

Khany, Reza & Marzieh Ghoreyshi. 2013. The nexus between Iranian EFL students’ Big Five personality traits and foreign language speaking confidence. European Online Journal of Natural and Social Sciences: Proceedings 2(2s), 601–611.Suche in Google Scholar

Komulainen, Emma, Katarina Meskanen, Jari Lipsanen, Jari Marko Lahti, Pekka Jylhä, Tarja Melartin, Marieke Wichers, Erkki Isometsä & Jesper Ekelund. 2014. The effect of personality on daily life emotional processes. PLoS One 9(10). e110907. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0110907.Suche in Google Scholar

Kotov, Roman, David Watson, Jennifer P. Robles & Norman B. Schmidt. 2007. Personality traits and anxiety symptoms: The multilevel trait predictor model. Behaviour Research and Therapy 45(7). 1485–1503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2006.11.011.Suche in Google Scholar

Lahuerta, Ana Cristina. 2014. Factors affecting willingness to communicate in a Spanish university context. International Journal of English Studies 14(2). 39–55. https://doi.org/10.6018/j.193611.Suche in Google Scholar

Lao, Tiffany Laiyin. 2020. The relationship between ESL learners’ motivation, willingness to communicate, perceived competence, and frequency of L2 use. Studies in Applied Linguistics and TESOL 20(2). 36–56. https://doi.org/10.52214/salt.v20i2.7475.Suche in Google Scholar

Lee, Ju Seong, Kilryoung Lee & Chen Hsieh Jun. 2022. Understanding willingness to communicate in L2 between Korean and Taiwanese students. Language Teaching Research 26(3). 455–476. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168819890825.Suche in Google Scholar

Mac Giolla, Erik & Petri J. Kajonius. 2019. Sex differences in personality are larger in gender equal countries: Replicating and extending a surprising finding. International Journal of Psychology 54(6). 705–711. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12529.Suche in Google Scholar

MacIntyre, Peter D. 2020. Expanding the theoretical base for the dynamics of willingness to communicate. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching 10(1). 111–131. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2020.10.1.6.Suche in Google Scholar

MacIntyre, Peter D., Carolyn Burns & Alison Jessome. 2011. Ambivalence about communicating in a second language: A qualitative study of French immersion students’ willingness to communicate. The Modern Language Journal 95(1). 81–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2010.01141.x.Suche in Google Scholar

MacIntyre, Peter D., Richard Clément, Zoltán Dörnyei & Kimberly A. Noels. 1998. Conceptualizing willingness to communicate in a L2: A situational model of L2 confidence and affiliation. The Modern Language Journal 82(4). 545–562. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.1998.tb05543.Suche in Google Scholar

MacIntyre, Peter D. & Jesslyn Doucette. 2010. Willingness to communicate and action control. System 38(2). 161–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2009.12.013.Suche in Google Scholar

MacIntyre, Peter D. & Robert C. Gardner. 1989. Anxiety and second-language learning: Toward a theoretical clarification. Language Learning 39(2). 251–275. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-1770.1989.tb00423.x.Suche in Google Scholar

MacIntyre, Peter D., Keith MacMaster & Susan C. Baker. 2001. The convergence of multiple models of motivation for second language learning: Gardner, Pintrich, Kuhl, and McCroskey. In Zoltán Dörnyei & Richard Schmidt (eds.), Motivation and second language acquisition, 461–492. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawai’i, Second Language Teaching and Curriculum Center.Suche in Google Scholar

MacIntyre, Peter D. & Lanxi Wang. 2022. Anxiety. In Shaofeng Li, Phil Hiver & Mostafa Papi (eds.), The Routledge handbook of second language acquisition and individual differences, 1st edn., 175–189. Routledge.10.4324/9781003270546-15Suche in Google Scholar

Magidson, Jessica F., Brent W. Roberts, Anahi Collado-Rodriguez & C. W. Lejuez. 2014. Theory-driven intervention for changing personality: Expectancy value theory, behavioral activation, and conscientiousness. Developmental Psychology 50(5). 1442–1450. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030583.Suche in Google Scholar

Marx, Nicholas. 2019. Age and gender on foreign language anxiety: A case of junior high school English learners in Japan. Kanazawa Seiryo University Bulletin of the Humanities 3(2). 33–42.Suche in Google Scholar

McCrae, Robert R. & Paul T. Costa. 2003. Personality in adulthood: A five-factor theory perspective. New York: Guilford Press.10.4324/9780203428412Suche in Google Scholar

Meyer, Jennifer, Johanna Fleckenstein, Jan Retelsdorf & Olaf Köller. 2019. The relationship of personality traits and different measures of domain-specific achievement in upper secondary education. Learning and Individual Differences 69. 45–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2018.11.005.Suche in Google Scholar

Mike, Anissa, Kelci Harris, Brent W. Roberts & Joshua J. Jackson. 2015. Conscientiousness. In J. D. Wright (ed.), International encyclopedia of the social and behavioral sciences, 2nd edn., 658–665. Elsevier.10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.25047-2Suche in Google Scholar

Montero-SaizAja, Alejandra. 2021. Gender-based differences in EFL learners’ language learning strategies and productive vocabulary. Theory and Practice of Second Language Acquisition 7. 83–107. https://doi.org/10.31261/TAPSLA.8594.Suche in Google Scholar

Munezane, Yoko. 2016. Motivation, ideal self and willingness to communicate as the predictors of observed L2 use in the classroom. EUROSLA Yearbook 16. 85–115. https://doi.org/10.1075/eurosla.16.04mun.Suche in Google Scholar

Novikova, Irina A., Nadezhda S. Berisha, Alexey L. Novikov & Dmitriy A. Shlyakhta. 2020. Creativity and personality traits as foreign language acquisition predictors in university linguistics students. Behavioral Sciences 10(1). 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs10010035.Suche in Google Scholar

Ożańska-Ponikwia, Katarzyna, Ewa Piechurska-Kuciel & Katarzyna Skałacka. 2020. Emotional intelligence as a mediator in the relationship between neuroticism and L2 achievement. Applied Linguistics Review 14(1). 67–86. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2020-0008.Suche in Google Scholar

Öztürk, Nesrin. 2021. The relation of metacognition, personality, and foreign language performance. International Journal of Psychology and Educational Studies 8(3). 103–115. https://doi.org/10.52380/ijpes.2021.8.3.329.Suche in Google Scholar

Parsons, Thomas D., Albert R. Rizzo, Cheryl van der Zaag, Jocelyn S. McGee & J. Galen Buckwalter. 2005. Gender differences and cognition among older adults. Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition 12. 78–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/13825580590925125.Suche in Google Scholar

Piechurska-Kuciel, Ewa. 2008. Language anxiety in secondary grammar school students. Opole: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Opolskiego.Suche in Google Scholar

Piechurska-Kuciel, Ewa. 2012. Gender-dependent language anxiety in Polish communication apprehensives. Studies in Second Language Learning & Teaching. Special Issue: Affect in Second Language Learning 2 (2). 227–248. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2012.2.2.6Suche in Google Scholar

Piechurska-Kuciel, Ewa. 2014. Attributions in high and low willingness to communicate. Anglica Wratislaviensia LII. 131–148.Suche in Google Scholar

Piechurska-Kuciel, Ewa. 2018. Openness to experience as a predictor of L2 WTC. System 72. 190–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2018.01.001.Suche in Google Scholar

Piechurska-Kuciel, Ewa. 2020. The big five in SLA. Cham: Springe2r.10.1007/978-3-030-59324-7Suche in Google Scholar

Piechurska-Kuciel, Ewa. 2023. Empirical verification of the relationship between personality traits and EFL attainments. In Małgorzata Baran-Łucarz, Anna Czura, Małgorzata Jedynak, Anna Klimas & Agata Słowik-Krogulec (eds.), Contemporary issues in foreign language education, 215–230. Cham: Springer.10.1007/978-3-031-28655-1_12Suche in Google Scholar

Piechurska-Kuciel, Ewa, Katarzyna Ożańska-Ponikwia & Katarzyna Skałacka. 2024. Language anxiety mediates the link between Agreeableness and self-perceived foreign language skills. Moderna Språk 118(3). 131–143. https://doi.org/10.58221/mosp.v118i3.14845.Suche in Google Scholar

Piniel, Katalin & Anna Zólyomi. 2022. Gender differences in foreign language classroom anxiety: Results of a meta-analysis. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching 12(2). 173–203. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2022.12.2.2.Suche in Google Scholar

Rabadi, Reem I. & Alexander D. Rabadi. 2022. Anxiety in learning German as a foreign language: Its association with learners variables. Dirasat: Human and Social Sciences 49(4). 410–424. https://doi.org/10.35516/hum.v49i4.2091.Suche in Google Scholar

Sadoughi, Majid & S. Yahya Hejazi. 2023. How can L2 motivational self system enhance willingness to communicate? The contribution of foreign language enjoyment and anxiety. Current Psychology 43. 2173–2185. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04479-3.Suche in Google Scholar

Šafranj, J. & M. Katić. 2019. Five personality traits and willingness to communicate. Andragogija 65(1). 69–81. https://doi.org/10.19090/ps.2019.1.69-81.Suche in Google Scholar

Shen, Siying, Diana Mazgutova & Gareth McCray. 2020. Exploring classroom willingness to communicate: The role of motivating future L2 selves. International Journal of Educational Methodology 6(4). 729–743. https://doi.org/10.12973/ijem.6.4.729.Suche in Google Scholar

Shirvan, Majid Elahi, Gholam Hassan Khajavy, Peter D. MacIntyre & Tahereh Taherian. 2019. A meta-analysis of L2 willingness to communicate and its three high-evidence correlates. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research 48(6). 1241–1267. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10936-019-09656-9.Suche in Google Scholar

Slik, Frans W. P., Roeland W. N. M. van Hout & Job J. Schepens. 2015. The gender gap in second language acquisition: Gender differences in the acquisition of Dutch among immigrants from 88 countries with 49 mother tongues. PLoS One 10(11). e0142056. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0142056.Suche in Google Scholar

Spielberger, Charles D. 2010. State-trait anxiety inventory. In Irving B. Weiner & W. Edward Craighead (eds.), The corsini encyclopedia of psychology, 1. Hoboken: Wiley.10.1002/9780470479216.corpsy0943Suche in Google Scholar

Tackman, Alison M., Sanjay Srivastava, Jennifer H. Pfeifer & Mirella Dapretto. 2017. Development of conscientiousness in childhood and adolescence: Typical trajectories and associations with academic, health, and relationship changes. Journal of Research in Personality 67. 85–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2016.05.002.Suche in Google Scholar

Teimouri, Yasser. 2017. L2 selves, emotions, and motivated behaviors. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 39(4). 681–709. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263116000243.Suche in Google Scholar

Teimouri, Yasser, Julia Goetze & Luke Plonsky. 2019. Second language anxiety and achievement: A meta-analysis. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 41(2). 363–387. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263118000311.Suche in Google Scholar

Theobald, Maria, Henrik Bellhäuser & Margarete Imhof. 2018. Identifying individual differences using log-file analysis: Distributed learning as mediator between conscientiousness and exam grades. Learning and Individual Differences 65. 112–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2018.05.019.Suche in Google Scholar

Tóth, Andrea. 2021. The effect of anxiety on foreign language academic achievement. Hungarian Educational Research Journal 12(2). 193–201. https://doi.org/10.1556/063.2021.00098.Suche in Google Scholar

Trautwein, Ulrich, Lüdtke Oliver, Nicole Nagy, Anna Lenski, Alois Niggli & Inge Schnyder. 2015. Using individual interest and conscientiousness to predict academic effort: Additive, synergistic, or compensatory effects? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 109(1). 142–162. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000034.Suche in Google Scholar

Varanarasama, Eswari, Avanish Kaur Gurmit Singh & Kavitha Nalla Muthu. 2019. The relationship between personality and self-esteem towards university students in Malaysia. Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research (ASSEHR) 34. 410–414. https://doi.org/10.2991/acpch-18.2019.97.Suche in Google Scholar

Vedel, Anna & Arthur E. Poropat. 2017. Personality and academic performance. In Virgil Zeigler-Hill & Todd K. Shackelford (eds.), Encyclopedia of personality and individual differences, 1–9. Cham: Springer.10.1007/978-3-319-28099-8_989-1Suche in Google Scholar

Verbree, Anne-Roos, Lisette Hornstra, Lientje Maas & Leoniek Wijngaards-de Meij. 2022. Conscientiousness as a predictor of the gender gap in academic achievement. Research in Higher Education 64. 451–472. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-022-09716-5.Suche in Google Scholar

Vural, Haldun. 2019. The relationship of personality traits with English speaking anxiety. Research in Educational Policy and Management 1(1). 55–74. https://doi.org/10.46303/repam.01.01.5.Suche in Google Scholar

Wang, Xue & Wei Zhang. 2021. Psychological anxiety of college students’ foreign language learning in online course. Frontiers in Psychology 12. 598992. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.598992.Suche in Google Scholar

Wehner, Caroline & Trudie Schils. 2021. Who are the low educational achievers? An analysis in relation to gender, emotional stability and conscientiousness. Applied Economics 53(46). 5354–5368. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2021.1922592.Suche in Google Scholar

Yetkin, Ramazan & Zekiye Özer. 2022. Age, gender, and anxiety as antecedents of willingness to communicate: Turkish EFL context. Acuity: Journal of English Language Pedagogy, Literature and Culture 7(2). 195–205.10.35974/acuity.v7i2.2800Suche in Google Scholar

Zhang, Xian. 2019. Foreign language anxiety and foreign language performance: A meta-analysis. The Modern Language Journal 103(4). 763–781. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12590.Suche in Google Scholar

Zhou, Li, Yiheng Xi & Katja Lochtman. 2023. The relationship between second language competence and willingness to communicate: The moderating effect of foreign language anxiety. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 44(2). 129–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2020.1801697.Suche in Google Scholar

Zohoorian, Zahra, Zeraatpishe Mitra & Narges Khorrami. 2022. Willingness to communicate, Big Five personality traits, and empathy: How are they related? Canadian Journal of Educational and Social Studies 2(5). 17–27. https://doi.org/10.53103/cjess.v2i5.69.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.