Abstract

This article builds upon research which analyses the reconstruction of cities in China as an integral part of image-making discourses competing to attract mobile capital. It extends that literature beyond urban places to urbanisation processes, examining the material and linguistic features of networks and discourses of new high-speed rail infrastructure Guangxi, a poorer, rural, multilingual and multiethnic region of the People’s Republic of China (China) in which tourism – propelled by high-speed trains – has become a pillar of economic development. It argues that these trains produce symbolically powerful discourses which contribute to cultural urbanisation across Guangxi, emplacing urban norms outside city limits in pursuit of profitable sameness, as tourism does not trade only upon difference. Local multilingualism, specifically, is erased as too different, a barrier to tourists’ (and tourism capital’s) mobility. Amongst other ramifications, this reproduces social distance and ideologically displaces local languages.

1 Approaching Guangxi’s tourism from overlapping literatures

This article treats discourses as formed of both linguistic and material semiotic resources. While it contributes to fusing linguistic and anthropological research into tourism, it builds specifically upon research analysing the reconstruction of cities in China as an integral part of image-making discourses which are, in themselves, integral in competing to attract mobile capital (e. g. Xu and Yeh 2005: 301). Constructing and representing “spectacular” (Broudehoux 2007: 383) material change is especially significant in these discourses’ creation of difference. So is change that can be discursively constructed as increasing mobility or otherwise increasingly urbanity, because these are valued in the “nationalisation of modernity” discourses which are not only dominant in Chinese tourism but moreover characteristic of contemporary “late Socialist” China itself (Nyíri 2010: 65). For over twenty years, these discourses have constructed urbanisation as indexing economic and moral development and modernity (Nyíri 2010: 80–81). The focus of this “city repositioning” literature, as Xu and Yeh (2005: 283) label it, is on the performativity of place, which dovetails with Thurlow and Jaworski’s (e. g. 2014) influential work on the touristic value of linguistic resources in place-making, and with Salazar’s (2012: 864) influential theorising of “tourism imaginaries” as “socially transmitted representational assemblages”. That is, to have profitable “place-products” (Xu and Yeh 2005: 286), governments and other commercial actors must transmit representational assemblages which shape incomers’ imagination of what can and should be visited. This article theorises these place repositioning discourses within the “hermeneutic circle” described in tourism studies (Urry 1990: 140; Urry and Larson 2011: 187; Thurlow and Jaworski 2014: 463). That is, as certain images become dominant, those then influence the future performance, and material landscaping, of place and difference: images reshape actual practice.

But which places to study? Places of mobility. This Special Issue’s editors identified that the linguistics of tourism literature could be extended by focusing on mobility, and specifically by following Urry and Larson’s (2011: 101) reformulation of Urry’s (1990) widely-cited, dialectical “tourist gaze” to foreground “networks and discourses” rather than tourists. This article responds by examining the material and linguistic features of networks and discourses through the case of new transport infrastructure, extending Urry and Larson (2011: 101–128) analysis by focusing on a “mobile place[s]” (Jaworski 2014) par excellence. Specifically, the case study is of high-speed rail in Guangxi, a relatively poor, rural, multilingual and multiethnic region of South-Central China in which tourism – propelled by high-speed trains – has become a pillar of economic development. And why Guangxi? First, the study focuses on Guangxi because it is undergoing material renovation and tourism-centered development on a regional rather than metropolitan scale, which assists in the intended foregrounding of urbanisation processes over urban places, in order to denaturalise and therefore open for inquiry the association between urban norms and actual cities. The lens of Chinese city repositioning literature focuses on how cities are made to appear worth visiting, moving to or investing in. This article widens the angle to urbanisation as a process potentially affecting and repositioning practices and values in all sorts of places, not only in cities. For clarity, the article also narrows to one key competition for mobile capital, tourism. The article posits that in the case of Guangxi, strategic image-making for the attraction of tourism dollars is being applied to the region rather than specific cities, but likewise relies on material reconstruction and its representation. The literature emphasises that competitive cities seek to create images of difference. But familiarity is also lucrative in luring outsiders, and difference can be expensive to produce. This article therefore asks, in what forms is sameness as well as difference discursively (re)produced to attract tourists to Guangxi? Moreover, this article treats language as crucial to transmitting tourism imaginaries of sameness or difference, foregrounding how language choices and representations of language are means of constructing identities, place-products and social distances or affinities (cf. Heller et al. 2014). Thus, homing in, it also asks what role does language play?

Second, the study focuses on Guangxi because it is a multilingual and diverse region associated with China’s officially-recognised minority ethnic groups, especially the Zhuang (as the following section develops). In this context, the discursive construction of marketable sameness and difference is particularly loaded, and potentially destructive, as it interacts with pre-existing, socially significant constructions of sameness and difference, making the questions above especially pertinent.

Given its questions, this article adopts analytic concepts from linguistic studies of place-making: first, linguistic/semiotic landscapes, the discourses of which comprise interrelating material and linguistic semiotics resources. Linguistic landscape studies focus on the representation and display or circulation of language as an environment, or aggregate, which (re)produces discourse with place-making and other normative implications. Such analyses address the semiotics of material production and expression (Kress and van Leeuwen 2006: 215; Cook 2015; Beetz and Schwab 2017: x), the emplacement of language (called geosemiotics: Scollon and Scollon 2003: 4), “the use of space as a semiotic resource in its own right” (Jaworski and Thurlow 2010: 1; Banda and Jimaima 2015) and the meaning of public display (e. g. Coupland 2012). Thus, the article is not only looking at linguistic data: it follows a bedrock of linguistic/semiotic landscape literature examining the interaction of linguistic and non-linguistic semiotic resources – including emplacement and other aspects of materiality – as integral in place-making and in constructing social orders, or what anthropologists might call “world-making” (Chio 2017: 419).

Kress and van Leeuwen (2006: 35) explain an important aspect of this landscape metaphor: landscapes beguilingly naturalise their socially-situated production. Given this social dimension, semiotic landscape analysis attends to power, aligning with Salazar’s (2012: 877) call, within anthropological literature, for attention to power in studies of the creation of tourism imaginaries. Looking at these trains and rail networks as part of semiotic landscapes thus brings agency and power into focus. A second concept, linguascaping, further foregrounds agency and power in semiotic landscape studies. Choices about language use and display (i. e. linguascaping) are strategic, processual “deployment[s]” of linguistic resources which do semiotic place-making work and language ideological work (Jaworski and Piller 2008: 304; Thurlow and Jaworski 2010; Chen 2016).

The article uses these linguistic landscape and linguascaping concepts in a multimodal discourse analysis of my photos, notes and collected texts from travels on Guangxi’s high-speed rail during sociolinguistic fieldwork in 2015. That fieldwork built on trips to Guangxi in 2011, 2013 and 2014 and was part of an “itinerant ethnography” (Schein 2000: 26–28) about Zhuang language policy and new mobilities (Grey 2017, 2018). This article’s data also includes contemporaneous advertising media in which the trains were represented, akin to Chio’s (2017: 419) data on “visualisations of how rural ethnic China is imagined by and for urban tourists”.

The article explains why the construction of a high-speed rail network and its representation are central to Guangxi’s competition for mobile capital. It then analyses how the material and linguistic semiotic resources connected with the new high-speed rail infrastructure in Guangxi disseminate and normalise urban linguistic and material practices for the benefit of tourism, discursively constructing and emplacing linguistic and other forms of sameness. The final section discusses social and linguistic implications, in conversation with the literature.

2 Guangxi: A world apart

To begin, I present two photos setting the scene (Figures 1 and 2; all photographs reproduced in this article are my own, from 2015). Together with the images analysed later in the article, these may assist readers envisage the semiotic landscapes of Guangxi.

Guangxi’s historic and contemporary diversity makes the incoming of new connections, practices and technologies (including languages) potentially disruptive of its sociolinguistic environment but also of its image. Guangxi has long been constructed by and for Chinese (Han) and Western tourists as remote and exotically peopled (see e. g. Tapp and Cohn’s 2003 historic, pictorial travelogues). Its inhabitants were typically seen by imperial citizens as tribal “夷” [barbarians] (Mullaney 2011: 1). A related construction of Guangxi as an unspoiled, natural idyll ascended in the twentieth century (Turner 2010: 53), although the guang in Guangxi, meaning expanse, has been highlighting the region’s lack of hubs for over a millennium. Even with twentieth-century technologies of transport and communication, Guangxi remained relatively disconnected from the capital and trade routes.

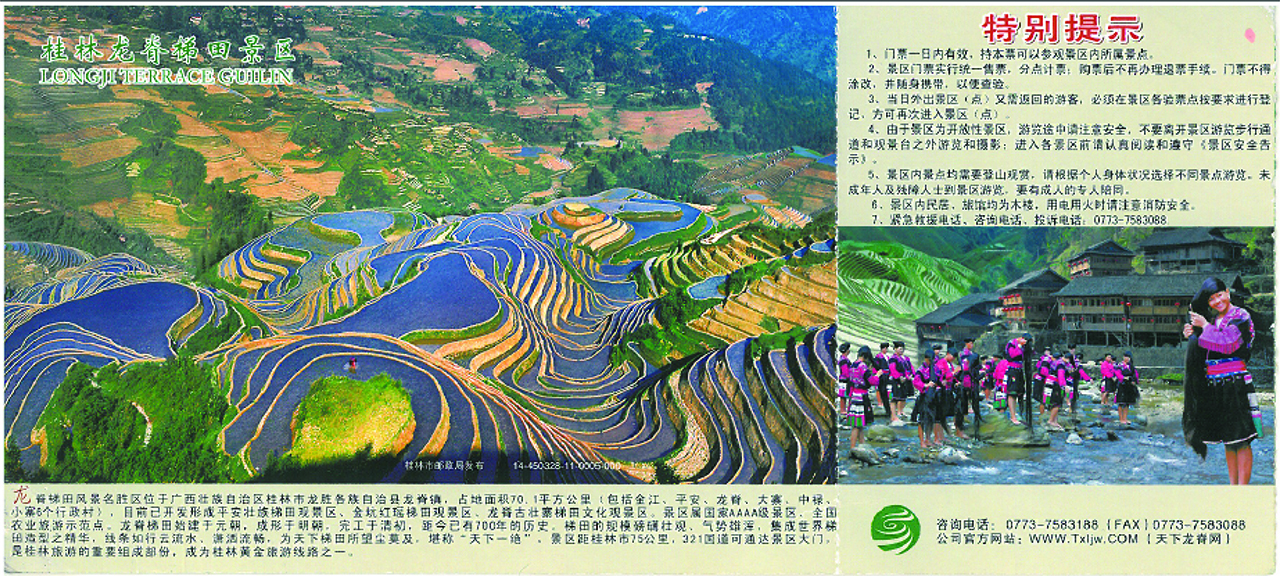

Imaginaries of the idyll repurpose Guangxi’s remoteness and socio-ethnic diversity as indices of tranquility and heritage, an immobile world apart from the modern bustle. In recent decades, this construction of Guangxi as emplaced and embodied natural and cultural heritage has been aided by government-propagated discourses attempting the “ethnicisation of the national geography” (Nyíri 2010: 65) for tourism-led development. Figure 3 is part of my ticket to enter into a state-run region of mountain villages and farms near Guilin now zoned for tourism. Its imagery of terraced mountains and costumed women combing unusually long hair exemplifies this discursive representation of the co-location of beautiful and visibly exotic landscapes and people.

Tourists pass “停车管 //Parking Lot” sign within the Longji Terrace ticketed tourist zone, Guangxi.

Scan of ticket for Longji Terrace tourist zone, Guangxi.

Moreover, Guangxi is a region where diverse minority languages including Zhuang, as well as Mandarin topolects, have long been spoken and still are (CASS Institute of Linguistics et al., 2012). Given some are officially minority varieties and some are not, the article uses the inclusive term local languages. Since the mid twentieth-century, the national standard variety of Mandarin, Putonghua, has also spread through the region, and most Zhuang speakers now also speak Putonghua/another variety of Mandarin (Chen 2005: 19–20). Like many Guangxi locals, tourists from elsewhere in China likely speak Putonghua/Mandarin topolects (Zhou 2012). However, as is well-known from tourism world-wide, a shared lingua franca between locals and tourists does not preclude the construction of a local language as a heritagising or exoticising feature of a place, or as central to locals’ perceptions of their own distinctiveness. In these regards, Zhuang, in particular, remains socially significant in Guangxi.

The Zhuang dialects originated in Guangxi (Li and Huang 2004: 239) and Zhuang is the most-spoken official minority language in China today, with roughly 10 million speakers (Ager 2016; Grey 2018: 8). Zhuang bears a legacy of being constructed as the defining characteristic when the government officially constituted the Zhuangzu minority group in the 1950s (Kaup 2000: 127 quoting government classifier Fei Xiaotong; compare the historic non-recognition of Zhuang: Barlow 1989: 33–34). Shared language legitimised the newly-classified Zhuangzu as a “plausible communit[y]” (Mullaney 2011: 69–91). Zhuang language was, therefore, crucial to the ensuing government discourses and activities aimed at entrenching a Zhuangzu identity (see Kaup 2000: 87; Grey 2018: 28–30), including promoting the name “Zhuang” (cuengh in Zhuang). Speaking Zhuang remained integral to the “imagined community” (Anderson’s 1991) underpinning many young Zhuangzu participants’ identity in my own twenty-first century study (Grey 2017). Zhuang, or Standard Zhuang at least, is also still important to the government as a linguistic emblem. The inclusion of Standard Zhuang on certain public texts in Guangxi (such as street names in Guangxi’s capital city, Nanning) is largely not to convey information: while Standard Zhuang was developed last century to bridge dialectal differences, it has not been developed into a lingua franca, nor widely taught as a writing system. Rather, displaying a (very limited) amount of Zhuang in some Guangxi cities represents local people, to honour and symbolically include them, and to heritagise place-products and create affinity between the government and the people (Grey 2017: 299–306). Nevertheless, although the government continues to emblematically deploy Zhuang, the language’s public presence in Guangxi is being overwhelmed by the presence of Mandarin, and English, in both governmental and commercial discourses, particularly in urban landscapes (Grey 2017: 250, 293–297). Even the Zhuang on Nanning’s bilingual street-name signage is not necessarily recognised by Zhuang speakers as Zhuang because they have developed the expectation of not seeing Zhuang in public (Grey 2017: 325–334). Finally, Zhuang is nowadays less likely to be spoken in Guangxi’s cities than its rural areas, not only because migrants to Guangxi – typically non-Zhuang speakers – are concentrated in cities. Guangxi’s urban schools offer less Zhuang-medium instruction than rural schools, typically none. Some Zhuang-speaking families in cities are deliberately not transmitting Zhuang within the home in the “zero-sum” belief that it detracts from children’s acquisition of Putonghua and English (Grey 2017: 392–395). Overall, my research has found that Zhuang is still a socially significant identity resource but in educational and urban places it is discursively constructed, especially by semiotic landscapes, as dissociated from urbanity, commerce and modernity. This article offers a complementary window on how the significance, and value, of Zhuang is changing in other places and through other emplaced discourses. It looks at the trains as vehicles for discursive navigation through the tensions between how Guangxi was and is imagined, and that which it aspires to become.

This tension has been identified by Guangxi’s Party Chief:

There are 49 poor counties in Guangxi with about 7.9 million people living under the national poverty line[…] But the beauty of the places they live in is beyond imagination[…] Therefore developing tourism, a shortcut to[…] integrating [Guangxi’s people] into the modern world, bears different meanings to Guangxi.’ (Li 2013)

This “different meaning” is that Guangxi must preserve rather than change its pre-modern landscapes to achieve the economic growth and connectedness which counts as development and modernity. The Party Chief’s speech goes on to identify Guangxi’s other distinguishing feature: diversity of peoples and cultures; this too must be preserved yet developed. Chio (2017:419) similarly observes that rural Chinese peoples’ “greatest economic resource is their perceived sociocultural differences from socio-politically dominant urban and mainstream conditions”. Thus, tourism in Guangxi must leverage the profitable “axes of difference” upon which Chio (2014:204) argues much of South China’s tourism relies: rural-urban, ethno-cultural minority-majority, and poor-rich. Imaginaries of Guangxi’s immobility emerge from centuries of discursive constructions, described above, of Guangxi and its people as remote from the capital and other conurbations of East China, not only geographically but normatively. Therefore, in distinguishing itself along the three axes, Guangxi must offer its version of that which Salzar (2012:875) calls “global tourism imaginaries of local immobility”, including economic immobility as well as cultural and temporal immobility (i. e. traditional heritage).

3 Trains in the remaking of Guangxi for tourism

Satisfying tourists’ expectations of natural, sociocultural and temporal difference means indexing pre-modern (vis pre-urban) practices and inaccessibility, but the new rail network offers intercity and interprovincial access to most of Guangxi. Thus, repositioning Guangxi within tourist imaginaries now entails a discursive reconciliation between the norms and practices of urbanity and rurality; affluence and poverty; and mainstream and minority culture. The stakes of this repositioning are high, as tourism is “expected to contribute 30% [of Guangxi’s GDP] by 2020” (Li 2013). This section analyses the indispensability of high-speed rail in Guangxi’s tourism-led regional development, and then the repositioning discourses of the high-speed rail.

Guangxi’s high-speed network opened in December 2014. Its lines emanate from cities in the affluent and industrial East (High-speed rail in China 2018) which already had high-speed connections and which are junctions for international networks. For example, the first line comprised hundreds of kilometers of new track and 23 stations (including that shown in Figure 4), quartering train travel time between Guangxi’s capital and Guangzhou, the most-populous mega-metropolis in China (Nanning–Guangzhou high-speed railway 2018). Guangzhou is now also linked by high-speed rail to Guilin, Guangxi’s major tourism gateway (famous for natural karst and river sites within and surrounding the city). Although non-existent a few years ago, these trains are now a consistent presence, with 48 trains in each direction daily between Guilin and Guangzhou (China Travel Guide 2018). This busy network is dense, too: five high-speed lines had opened across Guangxi by 2018, with stations in all but three of fourteen prefectures and high-speed infrastructure in one more prefecture under construction (Guangxi Government 2018). (Route map: http://chinatrain12306.com/travel/guangxi-by-rail.htm.)

Construction around Nanning’s new high-speed terminus.

The high-speed network’s construction and operation are overseen by the state-owned enterprise, China Rail, and government-funded (南宁至广州铁路[Nanning-Guangzhou Railway] 2008). The trains service both Guangxi locals and outsiders; high-speed passengers in Guangxi out-numbered the region’s permanent residents by a factor of six during 2014–2018 (Guangxi Government 2018), suggesting an influx. Not all passengers come for tourism, but many do. Chio (2014: 3–4) outlines a Central Government campaign, commencing in 2006, to develop rural tourism nationwide as leisure for China’s urbanites, which built upon the 1990s’ government development of sites and creation of national holidays (Nyíri 2010: 62–63). In Guangxi, however, tourism grew especially after high-speed rail came in: Xinhua (High-speed trains drive Guangxi’s development 2018) reports that Guilin received 38 million tourists in 2014 but, since its high-speed connection, now receives over double that number annually. When the high-speed network was extended in 2018 to connect Guilin to Hong Kong, Guilin’s visitor numbers from Hong Kong and Macau outstripped 2017’s numbers by 39%. These are mainly tourists from elsewhere in China: for example, in 2016, Guangxi’s “domestic tourists grew by 20.1% [year-on-year] to 404 million, generating revenue of RMB404.8 billion (+ 29.1%)” (HKTDC 2018). High-speed rail increases “capital city/gateway zones” (Han and Cheer 2018:159) which allow tourists to spread, and spend, across Guangxi.

While slower trains, buses and planes previously connected Guangxi to the rest of China, “only one rail route passed through Guangxi” before its first high-speed line (High-speed trains 2018). Conventional train and plane travel times could not facilitate tourists making short trips into Guangxi, nor enable anyone to squeeze in as many destinations across Guangxi as can now be included. Further, planes were too expensive for many until recent increases in middle class wealth. Because high-speed trains “challeng[e] th[e] canonised method of travel” they will change tourists’ expectations of Guangxi, incorporating new sites, just as Turner (2010: 80) argued of Guangxi’s earlier transport upgrades, and as Urry (1990) argued generally about motorised transport shaping touristic practices of visual consumption.

The government-led expansion of Guangxi’s tourism and its transport infrastructure are integrated with initiatives to develop Guangxi as a bridge to South-East Asia. These include holding the annual China-ASEAN Expo in Guangxi since 2004 (Macau Trade and Investment Promotion Institute 2018), opening a China-ASEAN free trade zone in Guangxi in 2010, and the current high-speed upgrade of track from Guangxi into Vietnam. Further, new tourism and transport infrastructure together feed the projected 10 billion RMB worth of a Guangxi-Guizhou-Guangdong “high-speed railway economic belt experimental area of cooperation” (High-speed trains 2018). Thus, while the new trains in Guangxi sit within a larger, and increasing, high-speed network, they are not incidentally traversing Guangxi. They have been constructed in Guangxi for Guangxi. The article now turns to how these trains construct Guangxi, and tourism within it.

3.1 Material transforming and linguascaping the landscape

In “up-scaling” (Blommaert 2007) junctions in Guangxi beyond local or regional scales the new network manifests a physically layered hierarchy of “progress”: the high-speed trains and their tracks physically dominate over the older, slower trains and pre-existing built environment, which are often at lower elevation (e. g. Figure 5). This material layering offers a semiotic affordance of the modern and urban taking over. Similarly, the future, both as a time scale and an ontology of progress, is also materialised by the infrastructure, as many stations have been built but not yet put to full use, anticipating growth. For example, on one trip between Guilin and Shenzhen, I wrote:

New 肇庆东 [Zhaoqing East] station. Still [as at previous stations] 4 double platforms and another high-speed rail [train] pulling out, but no visible urban centre, just a few 2-3 storey residences across some fields. (field note 16.6.2015)

Slow train, paddies and residences in Liuzhou, Guangxi, seen from high-speed train.

Suddenly, this hamlet has been furnished with a building which does not conform to the local architectural vernacular but instead to uniform standards emanating from outside Guangxi which coordinate station architecture on a national scale. This is not the first time outside architectural forms and materials have transformed this area. Central planning means many rural hamlets’ buildings conform to the brick, breeze-block and blue-roof styles found across China; architecture is already an index of central control. However, these stations exhibit material newness, grandeur of scale (e. g. cantilevered steel canopies) and non-local textures (e. g. shiny marble steps) which are consistent with China’s contemporary urban architecture.

This alignment with urban material norms is also achieved through the stations’ displays of bilingual Mandarin-English signage, some of which is visible from outside the stations. The linguascaping of stations is different to that of typical hamlets in that it increases the amount of text displayed and of alphabetic writing, and in the materials of signage. The locally typical textual displays – Mandarin characters on flappy red banners and painted on lime-washed walls – contrast with the durable, precisely fabricated, blue and grey metal and plastic of station signage, not to mention their alphabetic writing. I note that some English toponyms on these signs are loanwords, so they could be treated as Mandarin in its Romanised orthography, but other station signage unambiguously included English (e. g. “Tickets”). Such (read-as-)bilingual signage aligns with the linguistic norms of major Chinese cities’ linguistic landscapes. That signage, in turn, orients to international norms by including the Roman alphabet, which is strongly associated with – and sometimes assumed to be – English. I found other Romanised orthography on signage in China was recognised as English even when it was not, partly because people expected to see English on signage (Grey 2017: 325–328).

These linguistic norms are also reproduced within the carriages. Mandarin and English dominate the signage, announcements and tourism texts on board. For example, signs read “小心夹手// Risk of Pinching Hand” on the carriages’ sliding doors, and there are bilingual Mandarin-English tray-table warnings facing each passenger. Similarly, each carriage has a scrolling digital sign (Figure 6) which alternates between Mandarin and English versions of the same content, including safety warnings, speed, and upcoming stations. It is coordinated with pre-recorded bilingual audio announcements.

Scrolling digital sign and two carriage screens.

These texts prioritise Mandarin speakers who also speak/recognise English rather than English-speaking visitors who do not speak Mandarin, because certain information is only expressed in Mandarin. For example, in written and audio modes the authorities chose to transliterate rather than fully translate toponyms into English. This resulted in “Nanningdong” rather than “Nanning East” being written on the scrolling sign, where “dong” means East (东) (partially visible in Figure 2), and in “shenzhenbei railway station” instead of “shenzhen north railway station” being spoken in the audio announcements, where “bei” means North (北). The intended audience are Mandarin speakers who can understand written “dong” and spoken “bei”. Paid advertising within the trains likewise anticipates a Mandarin-speaking readership, using Mandarin for most informational content. For example, I observed Mandarin-medium advertisements for a local bank on macassars on the carriage seats. These only included English within a bilingual logo, where English could serve as a visual index of global commerce for Chinese customers. In addition, the trains’ interiors were absent of local languages (whether Zhuang, Dong, Cantonese, etc). This is consistent with urban linguistic landscapes in Guangxi (and elsewhere in China) and consistent with both commercial and governmental discourses in Guangxi, in which even the most prestigious local language, Zhuang, is rarely included or displayed (Grey 2017: 237–322).

Main road passing a major railway terminus in Guilin City, Guangxi.

The dominance of Mandarin anticipates a preponderance of Mandarin-speaking domestic tourists, assuming and reproducing Mandarin as the best lingua franca. The trains do not stop at Guangxi’s borders so the use and display of the national language may not surprise readers. However, these trains should be recognised as yet another vehicle for naturalising the association between Mandarin and modernity and mobility, and the disassociation of these from local languages. These linguascaping choices construct (Standard) Mandarin as in-place in Guangxi and the whole national to which these train lines extend, although Guangxi remains linguistically highly diverse and has regional and interprovincial lingua francas. The linguascaping constructs local languages as out of place on board and immobile, too localised to travel. Further, this linguascaping positions travelers as non-speakers of local varieties; the linguascaping disallows a passenger to embody being a Zhuang (or other local language) user. This is consistent with an absence of representations of locals as tourists or passengers, which the article discusses below. The point is not (only) that language choice is a tool in the politics of national unity through homogeneity. Rather, this article’s emphasis is on the trains and stations manifesting and permanently emplacing a discursive disassociation between Zhuang and urbanite practices of tourism and mobility.

Moreover, the “semiotic aggregates” (Scollon and Scollon 2003: 23) of the stations and train interiors orient to urban norms, emplacing new urban built environments into non-urban, less-urban and older urban areas. Jaworski and Yeung (2010: 153) consider that “the presence or absence of certain languages […] contributes to shaping a city’s sense of place” in relation to Hong Kong, and others affirms their point in other cities. A linguascape characterised by the presence Mandarin-English (asymmetric) bilingualism and the absence of local languages contributes to the sense of urban place in China, and that sense is recreated within these high-speed trains. The trains thus stretch “the city” through the countryside, keeping the city proximate to travelers on board.

Furthermore, including English on safety and direction signage is a norm of international tourism, and by following this norm, the trains are linguascaped to have an ambiance of global travel. The free in-train magazine, Journey 旅途, (Figure 7) is a key linguascaping resource. Its content participates in discourse, as does its choice of asymmetric Mandarin-English bilingualism, and its materiality. It is a familiar material object which mirrors a more established travel artefact, in-flight magazines. It replicates their procurement method and placement (provided free in each seat pocket) and their materiality of printing (A4, glossy paper stock, colourful graphics).

Covers of two editions of Journey 旅途 magazine printed in one, collected on-board in Guangxi.

Most importantly, Journey 旅途 follows the content conventions identified by Thurlow and Jaworski (2003:584) in their study of in-flight magazines: “a blend of travel brochure, lifestyle magazine, corporate catalogue and information leaflet”. Journey 旅途’s content covers all four conventions. For example, the May-June 2015 edition’s feature about high-speed rail connections to cities with universities in Guangxi was clearly a travel text, but it was also an information leaflet and an investment-promoting corporate text, as was that edition’s China-ASEAN Expo cover story. Lifestyle content in that edition included spreads about Chinese fine art and ASEAN nations’ cuisines.

Thurlow and Jaworski’s (2003) study of in-flight magazines’ global discourses argues that text and imagery of the in-flight genre orient to global norms and thus serve as identity resources to enact belonging to a mobile, global elite. Being mobile for leisure is an integral practice of this identity. The lifestyle content just mentioned exemplifies the in-train magazine indexing global and elite tourism practices and facilitating their embodiment by high-speed rail passengers, as readers. Thurlow and Jaworski (2003:579, 602) could have been talking of this in-train magazine rather than in-flight magazines when they argued those magazines not only “espouse a global lifestyle” in which consumption and mobility are crucial, but they are “instruments for representing the world […] as already globalised”. The positioning of high-speed rail travel as a practice of global travel is explicitly affirmed within the magazine: it has a regular section with the bilingual running header “Travel the World 旅途天下”. This header, as well as its bilingualism, denote the global scale. It implies that this magazine has an on-board readership who are potential world travelers. Positioning these passenger-readers as globe-trotters and sophisticated cosmopolites in the international mould also constructs China as a global place with people who partake in Global North practices of travel, cultural appreciation and consumption. The high-speed trains’ expensive and high-tech materiality, and their presence across previously remote and less modernised parts of the country, echoes this construction of global-elite China. The in-train magazine is, thus, a combination of linguistic and material semiotic resources for constructing train travel as a version of global and elite mobility.

Furthermore, both the material renovation of the physical landscape through the new rail infrastructure and its linguascaping emplace juxtapositions between urban and rural places, visible for both passengers and those outside. Riding or watching the high-speed trains thus offers new geosemiotic affordances of contrast, which become embodied in touring. These contributions to the semiotic aggregates through which the trains pass and in which their infrastructure is now fixed amplify differences in mobility, modernity and language. They make prominent the socially salient divisions: rich/poor, modern/pre-modern and future/past. The prestigious (first-listed) sides of these divisions are wrapped together in the urban imaginary in pervasive, global discourses which are reflected in advertising discourses representing Guangxi and its trains.

3.2 Representation: Trains in texts

The increased rail mobility for tourists through Guangxi allows more tourists to see more aspects of Guangxi and then describe or digitally remediate these to others, probably on the apps favored by Chinese tourists, WeChat and Ctrip (Han and Cheer 2018:176), which I note are under-studied. This propels the hermeneutic circle; however, the circle is also propelled by remediation by the state and state corporations. Guangxi Tourism Authority (GTA) and China Rail Corporation, amongst others, have significant power to assemble linguistic and material semiotic resources to strategically shape Guangxi’s image, particularly through advertisements. Analysing this advertising allows us to look at what the new connectedness means to stakeholders invested in developing Guangxi’s attractiveness to urbanite travelers. My analysis finds these promotional discourses emphasise the renovated materiality of Guangxi. Outsiders’ expectations of natural and exotic Guangxi are likely already formed by long-standing discourses, but representations of modernity and connectedness need to be introduced to the tourist imaginaries of Guangxi. To this end, high-speed rail is becoming an icon of Guangxi.

The key text which I use to illustrate this is a then-new GAT musical video advertisement for Guangxi played in 2015 by China Rail on repeat on screens inside each high-speed carriage. The video cut together iconic representations of the material features of local traditional lifestyles and landscapes, with representations of generic modern lifestyles and landscapes, sometimes even combining tropes in one scene. Figures 8–10 are photographs of a carriage’s ceiling-mounted television showing three consecutive scenes from this video, all with simplified character subtitles.

Lead singer receives tea, 2015 GAT video.

Singers at a high-speed platform in exotic costumes, 2015 GAT video.

Aerial shot of karst mountains, 2015 GAT video.

This video is significantly different from earlier GTA video advertisements, for example 2007’s Beautiful Scenery in Guangxi, which reinforced the region’s reputation for “beautiful scenery and colorful ethnic minorities” (Turner 2010: 55). Turner (2010: 155) found that singing minority people in outdoor settings was a trope in Guangxi tourism media, both printed and audiovisual. The 2015 video clearly conforms to those conventions, reproducing the visual discourses of people in colourful costumes singing, dancing, and practicing traditional tea-farming, as well as the iconic karst, river and rice-terrace scenes that dominate Guangxi’s representation in tourism discourses (Turner 2010: 53). However, this time the video jumps between those images and fast-forward footage of passengers walking through the new train stations, moving escalators, uniformed high-speed rail staff, aerial footage panning across urban areas, and blurred neon lights on roads. These are images indexing modern cities.

The video also offers new, integrative images. Figures 9 offers an example of one such scene. Here, the lead singer has changed from her various traditional costumes into a contemporary Western wedding dress and stands on a platform beside a high-speed train, singing with her troupe, who are in traditional costumes which have been spectacularised (Thurlow and Jaworski 2014: 482) with bright fabrics and large hats. Another recurring, integrative image in this video shows a high-speed train whooshing through a field of costumed tea-pickers.

Not only the brightly-clad, dancing women on the platform but also the neon lights and fast motion spectacularise these representations of daily urban life. Within a remote and heritage-laden tourism imaginary, this generic built environment can serve as spectacular and distinctive unlike, for instance, Beijing’s spectacular architecture (Broudehoux 2007) which is represented to seek differentiation from an already-urban imaginary. The 2015 GAT video’s aerial footage and shots of trains zooming past vegetation explicitly locate these urban places and practices within natural, rural landscapes, which the to-and-fro between urban and natural images also implies. Thus, the video meets commercial and state tourism policy incentives for rural Chinese peoples to be noticeably – indeed, spectacularly – ethnic and non-urban, but it also represents Guangxi as urbane and connected.

However, although the video cuts together two sets of indices, it does not represent minority people riding the trains. Rather, they are discursively constructed as in place in rural scenes doing traditional activities, or decorating platforms. They are, thus, landscape features to be visually consumed, and the video’s camera perspectives position viewers as consuming Guangxi visually in passing. This is heightened because the video’s viewers are simultaneously actually consuming the exterior landscape visually in passing. The costumes, dance moves, round tulou farm houses and tea-picking depicted in the 2015 video all index South China’s minority peoples and emphasise that they are distinct from the mainstream, but do not represent distinct peoples. Singing and subtitling in Mandarin, and the non-representation of any local languages, further elides specific identities. Rather, the video reproduces generic representations of ethno-tourism discourses in South China. For instance, the use of beautiful young women as the “faces” of local minorities who represent the region is an element which I observed in this and other Guangxi advertising, affirming Turner’s (2010: 155) analysis of Guangxi tourism discourses and Schein’s (2000) analysis of the gendering of “internal orientalism” discourses in China. Dance is another trope in these existing discourses. Thus, in this video, when the lead singer, the costumed choir and even the tea-pickers dance but urbanites and passengers do not; it reproduces the construction of dancing as an embodiment of minority heritage, and represents social division.

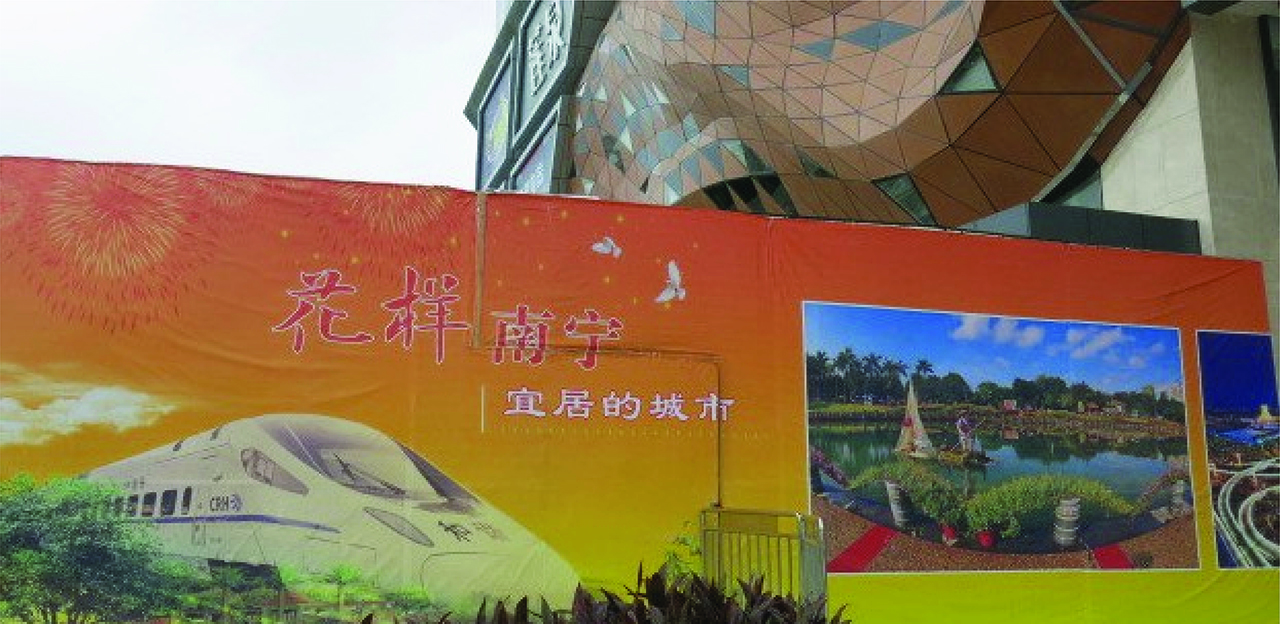

The iconisation of high-speed rail to renew the tourist imaginary of Guangxi is built up across multiple advertising discourses which construct these trains as urban. For example, outside a new mall built near the new high-speed rail terminus in Guangxi’s capital, Nanning, shown in Figure 4, I photographed the billboard in Figure 11. Its un-named producer appears to be a government invested in attracting residents to Nanning. (The central, regional and municipal governments share this interest, so it is not essential to pinpoint which authored this billboard.) The billboard can be translated as “Blossoming Nanning, [a] livable city”; it conveys that this city is rooted in a gardened template which makes it more pleasant and healthy than the typical concrete jungle. The billboard features a recognisable image of a high-speed train surrounded by green vegetation, which the word choice 花 [blossom(ing)] echoes. As in the video, the place is made distinct by an image of high-speed rail and urbanity located within nature.

Billboard at new mall near high-speed rail terminus, Nanning City.

Another discourse in which the connectedness that the new network creates is constructed as making Guangxi distinct and attractive is found in advertising directed specifically at high-speed rail passengers, and encountered in their free seat-pocket magazine. As noted above, the May-June 2015 edition of this magazine that I collected included a multi-page infomercial emphasising how the new trains connect places within Guangxi with institutions of higher education. The section included a map of high-speed lines across Guangxi with labels naming cities and universities. Part of the heading exhorts readers to “坐着高铁去学校!” [Ride the high-speed rail to get to school!].

This section found not only that high-speed trains are becoming a visual icon of Guangxi, at least in government advertising directed at attracting mobile capital, but also that the image strategy now seeks to combine natural and ethnic distinctiveness with generic modern urbanity (including high-speed rail). Ethnic Others spectacularise Guangxi’s landscapes rather than being represented as urbane, mobile people, and local languages are not represented at all by the state in advertising Guangxi’s place-products.

4 Findings in conversation with the literature

Returning the to the underpinning questions, sameness is being produced and reproduced in material and linguistic discourses in which the high-speed rail integrally participates and which it invests with symbolic power. This sameness is normalisation towards urban built environments, urban linguistic landscapes and non-minority culture. The difference on which Guangxi trades is as a place that exhibits modernity and pre-modernity, unlike Guangxi’s previous strategy of constructing a pre-modern image, and unlike the hyper-modern image that city repositioning literature identifies major Chinese cities as creating. However, the representations do not imagine minority people and cultures as modern or mobile. Iconising rail infrastructure and emphasising Guangxi’s urbanisation and connectedness does not necessarily undermine tourism sites’ authenticity. Zhu (2015:596–605) argues that the importance of maintaining material oldness is a powerful ideological imposition from “Western” cultures and international organisations which the Chinese state reproduces for interrelated tourism and nation-building reasons. That is, oldness and localness are not the only meaningful indices of authenticity. I argue that in the “dynamic process of authentication” (Zhu 2015: 596) in China today, the materiality of new, government-funded infrastructure and of being networked to the wider nation can themselves be resources for authenticating a tourism destination: state and market endorsement is provided in material form in the new network, and this authenticity is represented in advertising.

What role does language play in the discursive construction of Guangxi as place with attractive tourism destinations, then? Regarding local languages including Zhuang, their absence is a linguascaped semiotic resource. The Guangxi-specific tailoring of media within the trains, apparent in my data, reinforces the claim that there is agency behind the linguascaping, not neutral nature; local languages are not merely absent, they were not chosen. The linguascaping and representations construct these trains as places within which local people and languages are out of place; tourism is not embodied through local languages or by their speakers. By contrast, the presence of (Standard) Mandarin and English are linguascaping tools that produce urban-like places aligned with urban norms, which are themselves globalised. Overall, the linguascapes and representations examined in this article construct Guangxi as less multilingual than it is, representing it as spectacularly yet non-specifically multicultural. Thus, the symbolic power of the high-speed rail is invested in processes of “erasure” (Irvine and Gal 2000:39) of local linguistic diversity. Tourism anthropologists note of China that the state “salvage[s]” some practices and landscapes which fit with a multicultural imaginary, but not those believed to be “too primitive” or too emphatic of “local ethnic identity” (Nyíri 2010:64, quoting Oakes 1998). This article adds that local multilingualism does not fit China’s multicultural tourism imaginary. The non-use of local languages for constructing difference is not only because this simplification suits the rapid pace, and visual preference, of consumption in high-speed tourism. Language can be visually consumed, as the previous emblematising of written Zhuang in Guangxi, amongst other examples, indicates. Rather, I argue that local languages are erased following beliefs about their dissociation from modern life, and furthermore so that diversity – negatively evaluated as complication rather than complexity – is reduced to allow the for “consumption” of difference (Chio 2014: 205) in a touristic paradigm. This is because it makes practices and place-product more easily knowable and lowers barriers to (incoming) mobility. For example, linguascaping which aligns high-speed travel with the globalised tourism genres of in-flight magazines and bilingual signage, as well as replicating urban language and materiality norms, facilitates travelers to “move with as little disruption[…] as possible”, which Thurlow and Jaworski (2003: 599) identify as an integral “home-from-home” theme in tourism place-making. That is, outsiders can embody Guangxi’s locality and experience the Other without leaving the comfort of their own urban, linguistic norms. I therefore suggest that linguistic diversity is being constructed as mere noise, rather than language, which is a seminal ideological and perceptual distinction in a soundscape. Given the value that Thurlow and Jaworski’s (2010) have already established attaches to silence as a place-making feature of (elite) tourism, we can understand why this “noisiness” is not strategic to perform or represent.

Moreover, these are discourses with symbolic power (Bourdieu 1991), so they will disseminate norms. This symbolic power derives from the powerful author/sponsor: both the high-speed rail and Guangxi’s development of tourism are led by the central government. It also derives from the prestige of high market value: the high-speed fares are expensive compared to slower trains or buses. For example, Guilin to Shenzhen fares range from USD56 to USD110, while the fare on a slow train taking that route is USD20 (www.travelchinaguide.com). The materiality of the discourses amplifies this prestige and further invests the discourses with symbolic power, as does the cultural authority of deliberate uniformity, along with the physical layering and futurism discussed above. The high-speed rail’s linguascaped departures from the conventional use of emblematic Zhuang in Guangxi, and its other discursive constructions of place and tourism, therefore have normative ramifications.

Powerfully discursively constructing tourists and locals as sharing Mandarin-dominant language practices and norms of linguistic display shapes the tourist gaze (I prefer tourist tongue). Train-travelling tourists are encouraged by the trains’ discourses to expect Mandarin to be in place and usable across Guangxi, and to not anticipate or perhaps even notice linguistic diversity. The hermeneutic circle theory predicts tourism practices will then elide these languages to meet the imaginary, which I argue will further devalue local languages in Guangxi’s sociolinguistic economy. In a seminal sociolinguistic work about globalised economies, using a Canadian case study, Heller (2003: 190) identifies an economic change, particularly in tourism, towards language having the potential to be a “marketable commodity” distinct from an identity resource. However, if languages are constructed an unmarketable, as local languages seem to be in these discourses in Guangxi, this surely erodes their symbolic power (applying the economic logic proposed by Bourdieu 1977), reducing their affordances as an identity resource. Moreover, given the zero-sum belief about language learning, the low commercial value of local languages in Guangxi tourism further incentivises language shift to the outsider language, rather than rewarding multilingualism (cf. Heller 2003: 190). The high-speed rail facilitates outsiders – especially tourists – to make use of Guangxi, and in doing so reshapes locals’ use of their material, locational, cultural and linguistic resources for profit. This is an important – and problematic – cultural urbanisation ramification of the trains: they are vehicles transmitting norms not only beyond China’s major cities’, but beyond the rail network. These trains produce symbolically powerful discourses which construct tourism in Guangxi, and Guangxi as a place-product, as culturally urbanised while still naturally distinct and alive with heritage.

While some tourists come from Guangxi – still mainly from cities, as urban residents are comparatively wealthy – the article analysed why they alone cannot account for Guangxi tourism’s growth. Moreover, even Guangxi urbanite tourists distribute urban norms which originated outside Guangxi in national and international hubs. Let me draw attention to the similarity between cultural and linguistic normalisation through urbanites’ tourism and another mobility that the state uses for cultural normalisation: labor migration. “Peasants” migrate temporarily to cities, therein adopt urban norms, then disseminate them in their home communities (Nyíri 2010: 79). There is further work to be done in this vein synthesising studies of the multiple processes of cultural – rather than geographic – urbanisation.

The final argument of this article is that this normalisation towards the urban not only devalues but renders out-of-place linguistic diversity in Guangxi. This new network’s mobility, connectedness and urbanity are not equally available as representations, indices or identity resources. Rather, its discourses further distance non-urban language practices, places and lifestyles from prestigious and market-valued language practices, places and lifestyles. Constructing the practices of outsiders as more valuable than those of locals reproduces socially salient divisions between rural and urban people and between degrees of mobility and as such does further social “distancing work” (Chio 2014:204), although high-speed rail collapses physical distance. I argue that this discursive construction of these differences remains socially salient not despite but because urban, modern norms are being brought into closer proximity to older, local ones by high-speed rail travel. These divisions are maintained not only to service visiting urbanites’ needs as to limited dislocation, but to maintain the distinctions that tourists expect to see and embody. If the network and its discourses collapsed rather than replicating social divisions, not only would profitable distinction be lost but tourists’ consumption of place and culture would become uncomfortably self-referential.

Funding statement: This work was supported by the Macquarie University (Grant Number: Department of Linguistics Research Development Fun, Funder Id: http://dx.doi.org/10.13039/501100001230).

Acknowledgements

My thanks to the Special Issue editors and reviewers for their feedback.

References

Ager, S. 2016. Zhuang (Vaƅcueŋƅ/Vahcuengh). Omniglot: The online encyclopedia of writing systems and languages. Retrieved from http://www.omniglot.com/writing/zhuang.htm.Search in Google Scholar

Anderson, B. 1991. Imagined communities. London: Verso.Search in Google Scholar

Banda, F. & H. Jimaima. 2015. The semiotic ecology of linguistic landscapes in rural Zambia. Journal of Sociolinguistics 19/5(2015). 643–670.10.1111/josl.12157Search in Google Scholar

Barlow, J. 1989. The Zhuang minority in the Ming era. Ming Studies 1989(1). 15–45.10.1179/014703789788763976Search in Google Scholar

Beetz, J. & V. Schwab. 2017. Material discourse—Materialist analysis. Lanham: Lexington Books.Search in Google Scholar

Blommaert, J. 2007. Sociolinguistic scales. Intercultural Pragmatics 4(1). 1–19.10.1515/IP.2007.001Search in Google Scholar

Bourdieu, P. 1977. The economics of linguistic exchanges. Social Science Information 16(1). 645–688.10.1177/053901847701600601Search in Google Scholar

Bourdieu, P. 1991. Language and symbolic power (J. Thompson Ed.). Cambridge: Polity Press.Search in Google Scholar

Broudehoux, A-M. 2007. Spectacular Beijing: The conspicuous construction of an Olympic metropolis. Journal of Urban Affairs 29(4). 383–399.10.1111/j.1467-9906.2007.00352.xSearch in Google Scholar

CASS Institute of Linguistics, CASS Institute of Ethnology and Anthropology, and City University of Hong Kong Language Information Sciences Research Centre. 2012. 中国语言地图集 [Language Atlas of China]. Beijing: Commercial Press.Search in Google Scholar

Chen, H. 2005. 广西语言文字使用情况调查报告 [Report on the Investigation into the Circumstances of Language and Script Usage in Guangxi]. In Chen & Li (eds.), 广西语言文字使用问题调查与研究 [Investigation and Research on the Subject of Guangxi Languages and Scripts’ Usage], 16–23. Nanning: Guangxi Education Press.Search in Google Scholar

Chen, X. 2016. Linguascaping the Other: Travelogues’ representations of Chinese languages. Multilingua 35(5). 513–534.10.1515/multi-2014-1026Search in Google Scholar

China Travel Guide. 2018. Guangzhou – Guilin Train. https://www.travelchinaguide.com/china-trains/high-speed/guangzhou-guilin.htm (accessed 12 July 2018).Search in Google Scholar

Chio, J. 2014. A landscape of travel: The work of tourism in rural ethnic China. Seattle: University of Washington Press.Search in Google Scholar

Chio, J. 2017. Rendering rural modernity: Spectacle and power in a Chinese ethnic tourism village. Critique of Anthropology 37(4). 418.10.1177/0308275X17735368Search in Google Scholar

Cook, V. 2015. Meaning and material in the language of the street. Social Semiotics 25(1). 81–109.10.1080/10350330.2014.964025Search in Google Scholar

Coupland, N. 2012. Bilingualism on display: The framing of Welsh and English in Welsh public spaces. Language in Society 41(1). 1–27.10.1017/S0047404511000893Search in Google Scholar

Grey, A. 2017. How do language rights affect minority languages in China? An ethnographic investigation of the Zhuang minority language under conditions of rapid social change. PhD, Macquarie University, Australia. http://www.languageonthemove.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Grey_Zhuang_language_rights.pdfSearch in Google Scholar

Grey, A. 2018. A polity study of minority language management in China focusing on Zhuang. Current Issues in Language Planning 20(5). 443–502. doi: 10.1080/14664208.2018.1502513.Search in Google Scholar

Guangxi Government. 2018. Five years on, Guangxi’s high-speed rail statistics in a nutshell, on Guangxi, China. http://en.gxzf.gov.cn/2018-12/29/c_313322.htm (accessed 20 February 2019).Search in Google Scholar

Han, X. & J. Cheer. 2018. Chinese tourist mobilities and destination resilience: Regional tourism perspectives. Asian Journal of Tourism Research 3(1). 159–187.10.12982/AJTR.2018.0006Search in Google Scholar

Heller, M. 2003. Globalization, the new economy, and the commodification of language and identity. Journal of Sociolinguistics 7(4). 473–492.10.1111/j.1467-9841.2003.00238.xSearch in Google Scholar

Heller, M., A. Jaworski & C. Thurlow. 2014. Introduction: Sociolinguistics and tourism–mobilities, markets, multilingualism. Journal of Sociolinguistics 18(4). 425–458.10.1111/josl.12091Search in Google Scholar

“High-speed trains drive Guangxi’s development”. (2018). 29 November 2018, Xinahua/CGTN. https://news.cgtn.com/news/3d3d414f314d544f30457a6333566d54/share_p.htmlSearch in Google Scholar

HKTDC. 2018. Guangxi: Market profile. http://china-trade-research.hktdc.com/business-news/paper/Facts-and-Figures/Guangxi-Market-Profile/ff/en/1/1X000000/1X06BURR.htmSearch in Google Scholar

Irvine, J. & S. Gal. 2000. Language ideology and linguistic differentiation. In Paul V. Kroskrity (ed.), Regimes of language: Ideologies, polities, and identities, 35–83. Santa Fe: School of American Research Press.Search in Google Scholar

Jaworski, A. 2014. Mobile language in mobile places. International Journal of Bilingualism 18(5). 524–533.10.1177/1367006913484207Search in Google Scholar

Jaworski, A. & I. Piller. 2008. Linguascaping Switzerland: Language ideologies in tourism. In Miriam A. Locher & Jürg Strässler (eds.), Standards and norms in the English language, 301–321. Berlin: De Gruyter.10.1515/9783110206982.2.301Search in Google Scholar

Jaworski, A. & C. Thurlow. 2010. Introducing semiotic landscapes. In Adam Jaworski & Crispin Thurlow (eds.), Semiotic landscapes: Language, image, space, 1–40. London: Continuum.Search in Google Scholar

Jaworski, A. & S. Yeung. 2010. Life in the Garden of Eden: The naming and imagery of residential Hong Kong. In Eliezer Ben-Rafael, Elana Shohamy & Monica Barni (eds.), Linguistic landscape in the city, 153–181. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.10.21832/9781847692993-011Search in Google Scholar

Kaup, K. 2000. Creating the Zhuang: Ethnic politics in China. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers.10.1515/9781626373228Search in Google Scholar

Kress, G. & T. van Leeuwen. 2006. Reading images: The grammar of visual design, 2nd edn. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780203619728Search in Google Scholar

Li, X. & Q. Huang. 2004. The introduction and development of the Zhuang writing system. In Zhou Minglang & Sun Hongkai (eds.), Language policy in the People’s Republic of China: Theory and practice since 1949, 239–256. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.10.1007/1-4020-8039-5_13Search in Google Scholar

Li, Y. 2013. Tourism to become key for Guangxi. China Daily 4 July 2013. http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/travel/2013-07/04/content_16724226.htm. (accessed 13 July 2018).Search in Google Scholar

Macau Trade and Investment Promotion Institute. 2018. Market Briefing – Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region. https://www.ipim.gov.mo/en/publication/market-briefing-guangxi-zhuang-autonomous-region/ (accessed 13 July 2018).Search in Google Scholar

Mullaney, T. 2011. Coming to terms with the nation: Ethnic classification in modern China. Berkeley: University of California Press.10.4000/chinaperspectives.5586Search in Google Scholar

Nyíri, P. 2010. Mobility and cultural authority in contemporary China. Seattle: University of Washington Press.Search in Google Scholar

Salazar, N. 2012. Tourism Imaginaries: A Conceptual Approach. Annals of Tourism Research 39(2). 863–882.10.1016/j.annals.2011.10.004Search in Google Scholar

Schein, L. 2000. Minority rules: The Miao and the feminine in China’s cultural politics. Durham: Duke University Press.10.2307/j.ctv11688nqSearch in Google Scholar

Scollon, R. & S. Scollon. 2003. Discourses in place: Language in the material world. Abingdon: Routledge.10.4324/9780203422724Search in Google Scholar

Tapp, N. & D. Cohn. 2003. The tribal peoples of South West China. Bangkok: White Lotus.Search in Google Scholar

Thurlow, C. & A. Jaworski. 2003. Communicating a global reach: Inflight magazines as a globalizing genre in tourism. Journal of Sociolinguistics 7. 579–606.10.1111/j.1467-9841.2003.00243.xSearch in Google Scholar

Thurlow, C. & A. Jaworski. 2010. Silence is golden: Elitism, linguascaping and ‘anti-communication’ in luxury tourism discourse. In Adam Jaworski & Crispin Thurlow (eds.), Semiotic landscapes: Language, image, space, 187–218. London: Continuum.Search in Google Scholar

Thurlow, C. & A. Jaworski. 2014. ‘Two hundred ninety-four’: Remediation and multimodal performance in tourist placemaking. Journal of Sociolinguistics 18(4). 459–494.10.1111/josl.12090Search in Google Scholar

Turner, J. (2010). Cultural performances in the Guangxi tourism commons: A study of music, place, and ethnicity in Southern China. PhD, Indiana University, United States of America. http://pqdtopen.proquest.com/doc/734607419.html?FMT=AISearch in Google Scholar

Urry, J. 1990. The tourist Gaze: Leisure and travel in contemporary societies. London: Sage.Search in Google Scholar

Urry, J. & J. Larsen. 2011. The tourist Gaze 3.0. London: Sage.10.4135/9781446251904Search in Google Scholar

Xu, J. & A. Yeh. 2005. City repositioning and competitiveness building in regional development: New development strategies in Guangzhou, China. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 29(2). 283–308.10.1111/j.1468-2427.2005.00585.xSearch in Google Scholar

Zhou, M. 2012. Introduction: The contact between Putonghua (Modern Standard Chinese) and minority languages in China. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 2012(215). 1–17.10.1515/ijsl-2012-0026Search in Google Scholar

Zhu, Y. 2015. Cultural effects of authenticity: Contested heritage practices in China. International Journal of Heritage Studies 21(6). 594–608. DOI: 10.1080/13527258.2014.991935.Search in Google Scholar

“南宁至广州铁路今日开工 投资总额 410 亿元” [‘Nanning-Guangzhou Railway started construction today with a total investment of 41 billion yuan’]. 2008. 9 November 2008. Sina News. http://news.sina.com.cn/c/2008-11-09/174716618528.shtml.Search in Google Scholar

© 2020 Alexandra Grey, published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Introduction: Tourism spaces at the nexus of language and materiality

- Tourist tongues: High-speed rail carries linguistic and cultural urbanisation beyond the city limits in Guangxi, China

- Basque gastronomic tourism: Creating value for Euskara through the materiality of language and drink

- The scarf, language, and other semiotic assemblages in the formation of a new Chinatown

- Spectacular sea turtles: Circuits of a wildlife ecotourism discourse in Hawai‘i

- The materialization of language in tourism networks

- Tourism tensions and sociolinguistic change

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Introduction: Tourism spaces at the nexus of language and materiality

- Tourist tongues: High-speed rail carries linguistic and cultural urbanisation beyond the city limits in Guangxi, China

- Basque gastronomic tourism: Creating value for Euskara through the materiality of language and drink

- The scarf, language, and other semiotic assemblages in the formation of a new Chinatown

- Spectacular sea turtles: Circuits of a wildlife ecotourism discourse in Hawai‘i

- The materialization of language in tourism networks

- Tourism tensions and sociolinguistic change