Abstract

The Fuller Brooch is considered the earliest English representation of the five senses. The central character, representing sight, is thought to also hold one or more figurative meanings, linked to ideas and concepts that were current in King Alfred’s cultural context. These figurative meanings were presumably meant to be emphasised and clarified by the two objects this figure is holding. So far, however, these have not been satisfactorily interpreted, with most scholars tentatively identifying them as plants or cornucopias. This study makes a case for these objects to be torches, embodying the concept of light, so central in the theme of the oculi mentis ‘eyes of the mind’ and in Alfred’s ideas of wisdom and learning. The relevance of divine light in the Alfredian cultural framework emerges clearly from the translations into English of the Soliloquia, of the Consolatio Philosophiae and of the Regula pastoralis. Evidence also emerges from the iconography of the inluminatio ‘illumination’ of the oculi mentis for the acquisition of divine wisdom featuring in the Utrecht Psalter (and its later copies), and from the iconographical connection between torches, light and God that can be seen in the historiated initial of one of the hymns of the Durham Hymnal.

1 Introduction

The late-ninth-century[1] Fuller Brooch (see Figure 1), now in the British Museum, in London,[2] is considered by recent scholarship as one of the objects that very likely originated within Alfred’s circle (Kempshall 2001; Pratt 2003; Webster 2003a). The similarity between the central character on the Fuller Brooch and the character on the so-called Alfred Jewel[3] was noticed by Bakka already in 1966 (277–282); Pratt, Kempshall and Webster, however, have shown that the connection between the Fuller Brooch and the beliefs and works that can be tightly linked with King Alfred is much stronger than has ever been thought, based not only on style but also on intellectual content (Webster 2003 a: 87), featuring “symbolic iconographies of a kind close to Alfred’s own ideas about spiritual education and Christian kingship” (Webster 2003 a: 81).[4]

The main decorative motif of the Fuller Brooch has been interpreted as a personification of the five senses,[5] within the broader context of God’s Creation, and with the sense of sight – characterised by huge, emphasised eyes – given preeminence and appearing in the centre of the brooch.[6] There are no doubts that this central, anthropomorphic figure represents sight.[7] Given its prominence in the arrangement of the five senses, however, scholars have tended to attribute further figurative values to this central character. These additional values must be sought within a Christian framework, as the small cross clearly marked on the front of the character’s robe, interpreted by some scholars as a pallium, attests.[8] The very shape of the field in which the character has been placed, with four protruding ends, forming the arms of a square cross, also suggests a Christian interpretation. As to what these additional values might be, opinions vary, although most scholars seem to favour an interpretation of this iconographical element as wisdom[9] or Christ, or as a combination of both figurative meanings.[10]

One element that might help clarify the imagery intended by the maker or the commissioner of the brooch is the mysterious pair of objects that the central figure appears to be holding in a so-called Osiric pose. They consist of two long, tubular structures ending in flowing protuberances. This detail seems to have baffled scholars for a long time, and there is presently no agreement on what kind of objects they may be, although some sorts of plants or flowers,[11] possibly protruding from cornucopias,[12] seem to be the most accepted candidates. Wright (2007: 174) points out that “their prominence suggests they are symbolic attributes of the figures who hold them”;[13] it is difficult, however, to explain why cornucopias or plants should be so relevant to a representation of sight, and the identification of these two mysterious objects and their meaning remains, as Pratt (2003: 220) concedes, “a very open question”.[14]

The present study makes a case for these mysterious objects to represent torches, in connection with the concept of light, which was a pivotal part of the theme of the oculi mentis ‘eyes of the mind’, so dear to King Alfred and his scholarly helpers. After all, light is of primary importance to all human beings, and this importance is also revealed by its metaphoric[15] use in language. As Scott (2018: 77) states at the beginning of his chapter on light, in his exploration of the Universe:

Light is an essence of human existence, the primary way most people experience their world.[16] Its importance makes light a natural metaphor for creation, for understanding, for life itself. The heavens are ‘a shining firmament.’ God created light before all else. When a human is born, she ‘sees the light of day.’ We believe what we see ‘with our own eyes.’ We understand when we ‘see the light.’ We persevere if we see ‘light at the end of the tunnel.’ Tales of near death focus on a bright light calling the nearly departed to an afterlife. Light is a primal energy that represents life. It is clarity, truth, and safety. Darkness is danger; darkness is the underworld; darkness is death.

Divine light was a key concept in the context of Alfredian’s philosophy, in a time of moral darkness and danger, and torches may be considered an apt metaphor to represent this concept figuratively. This study explores the way in which this iconographic element is exploited here and in other contexts to represent, figuratively, the ability to see truth – in obscure times – through the light of divine wisdom.

2 The Fuller Brooch within the Theme of the oculi mentis

More than one scholar (Kempshall 2001; Pratt 2003; Webster 2003 a; Wilcox 2006) have underlined how some of the works and translations traditionally held to stem from the Alfredian cultural agenda[17] insist on the patristic metaphorical theme of the ‘eyes of the mind’ (Latin oculi mentis; OE modes eagan).[18] The eyes of the mind are illuminated by wisdom, thereby allowing the intellect to perceive divine truth. This concept emerges very clearly from the Old English translation of Augustine’s Soliloquia, where this process is explained in detail in parts of the work that are independent from the source text. A key passage reads:

Ac swa swa þeos gesewe sunne ures lichaman æagan onleoht, swa onliht se wisdom ures modes æagan, þæt ys, ure angyt; and swa swa þæs lichaman æagan halren beoð, swa hy mare gefoð þæs leohtes þære sunnan; swa hyt byð æac be þæs modes æagan, þæt is, andgit. Swa swa þæt halre byð, swa hyt mare geseon mæg þære æccan sunnan, þæt is, wysdom (Carnicelli 1969: Book 1, p. 78, l. 3–8).

‘But just as the visible sun gives sight to the eyes of our body, so wisdom gives sight to the eyes of our mind, that is, our understanding/intellect. And just as the eyes of our body are healthier when they receive more of the sun’s light, so it is also with the eyes of the mind, that is, understanding/intellect. The healthier that is, the more it may see of the eternal sun, which is wisdom’.[19]

This passage establishes a parallelism between the vision of the eyes of the body and that of the eyes of the mind. The eyes of the body provide physical sight by means of physical light, that is the visible sun, allowing men to perceive corporeal reality. The eyes of the mind, conversely, provide intellect/understanding by means of the light of wisdom, that is the eternal sun (=God), allowing men to perceive divine truth. This parallelism can be summarised in the table below:

Instrument Eyes of the Body Eyes of the Mind

Physical vision Intellect / understanding

Empowering Element Light given by the visible sun Light given by the eternal sun / God / wisdom

Target Corporeal reality Divine truth = God

God, in this view, is both the target and the empowering element, because it is only through God’s light that man can perceive truth and God himself, who is the eternal light.

Light is therefore a key element in the whole process, since the light of wisdom and the light of God must illuminate the intellect (= the modes eagan ‘eyes of the mind’) so that it can perform its function. It is like necessary fuel. This relevance is also stressed in the Preface to the translation of the Soliloquia, where the author expresses confidence that God will illuminate the eyes of his mind (mines modes eagan ongelihte ‘illuminate the eyes of my mind’) to let him understand the right path and lead him to eternal glory:

Swa ic gelyfe eac þæt he gedo for heora ealra earnunge, ægðer ge þisne weig gelimpfulran gedo þonne he ær þissum wes, ge hure mines modes eagan to þam ongelihte þæt ic mage rihtne weig aredian to þam ecan hame, and to þam ecan are, and to þare ecan reste þe us gehaten is þurh þa halgan fæderas (Carnicelli 1969: Preface, from p. 47, l. 16 to p. 48, l. 3).

‘[A]s I believe He will, through the merits of all these [saints], both make this present road easier than it was before, and in particular will illuminate the eyes of my mind so that I can discover the most direct way to the eternal home and to eternal glory and to the eternal rest which is promised to us through those holy fathers.’ (Keynes and Lapidge 1983: 138–139)

The theme of the modes eagan and the relevance of light within the theme are well attested also in the translation of Boethius’s Consolatio Philosophiae and in the translation of Gregory’s Regula pastoralis.[20] In the translation of the Consolatio Philosophiae, for example, God is asked explicitly to illuminate the eyes of the mind with his light, and let the just ultimately see God:

Forgif us þonne hale eagan ures modes þæt we hi þonne moton afæstnian on þe, and todrif ðone mist þe nu hangað beforan ures modes eagum, & onliht þa eagan mid ðinum leohte; forþam ðu eart sio birhtu ðæs soðan leohtes, and þu eart sio sefte ræst soðfæstra, and ðu gedest þæt hi ðe gesioð (Godden and Irvine 2009: vol. 1, p. 318, ch. 33, l. 244–248).

‘Grant us then healthy eyes of our mind that we may fasten them on you, and drive away the mist that now hangs before the eyes of our mind, and illuminate the eyes [of our mind] with your light; because you are the brightness of the true light, and you are the soft rest of the just, and you grant that they see you.’

Wilcox’s analysis of the modes eagan commonplace in the Old English translations of Gregory’s Regula pastoralis, Augustine’s Soliloquia and Boethius’s Consolatio Philosophiae demonstrates that this theme was actually reinforced in the vernacular Old English works and used even more cogently and profusely than in the original Latin texts (Wilcox 2006: 187). She shows how this notion revolves around the concepts of light and illumination, and around a light vs. dark opposition, both in the vernacular texts and in their sources. She also discusses how relevant and functional this concept was for Alfred’s idea of wisdom and for his conception of the duties of a pious ruler.

The relevance of the concept of light in the Alfredian cultural framework is also apparent in the studies of other scholars. While analysing Alfred’s use of Gregory’s Regula pastoralis, Kempshall (2001: 124) remarks: “the sense of sight is the understanding with which he [i. e. the ruler] sees wisdom, the light of truth. [...] Those in the highest authority are like eyes, using the light of knowledge to see ahead.”[21]

Pratt’s own words, discussing Alfred’s agenda, assign a key role to the concept of light in Alfred’s vision, in which, he states, Alfred could perceive himself simultaneously as the wise King Solomon, and as wisdom itself, that is “the divine lord, who illuminates all with his light, like the sun”:

Alfred’s own learning made it credible for him to represent simultaneously both wisdom himself – that is, the divine lord who illuminates all with his light, like the sun – and also the wise King Solomon, to whom all the earth had come, like the Queen of Sheba, in order to hear his wisdom. (Pratt 2003: 193)

Pratt (2003: 212–216) and Webster (2003a: 87) agree that this pursuit of temporal and spiritual wisdom, which is the central core of the oculi mentis/modes eagan theme, is suggested also by the iconography of the Fuller Brooch. In Webster’s words:

It is not difficult to see how such an unusual item, carrying a very structured message about the pursuit of wisdom, might have made a suitable emblem not just of temporal status but also an exemplar of the search for spiritual wisdom upon which earthly power depends. (Webster 2003 a: 87)

It would seem hardly surprising, therefore – given the relevance of the concept of light in the oculi mentis/modes eagan theme, and particularly within the Alfredian cultural framework – to find a depiction of this ‘divine light’ on the Fuller Brooch, in connection with the concepts of sight, the modes eagan, and the pursuit of wisdom. In fact, it is exactly this divine light that distinguishes the physical sight of the lichaman eagan ‘eyes of the body’ from the spiritual sight of the modes eagan ‘eyes of the mind’.[22]

In my reading, this divine light is depicted, on the Fuller Brooch, in the shape of torches, which are intuitively connected to light and sight, since, through the brightness produced by their fiery tongues, torches allow human beings to see in the dark, when the sun no longer shines. They are a replacement for the light of the sun, allowing men to see in times of darkness. Here darkness is to be intended in a spiritual sense, on the basis of the light/darkness opposition which is part of the patristic oculi mentis commonplace, as explained above, and torches are meant to represent wisdom, that is the ‘divine light’ that allows the modes eagan to perceive truth and dispel darkness/blindness.

This iconography is by no means exclusive to the Fuller Brooch: it is also found in Carolingian Psalters portraying God bestowing his light on the psalmist’s eyes, as will be shown in the next sections (3–4), discussing the iconography of torches in Carolingian and early English manuscripts and other objects.

3 The Iconography of Torches in Early English Manuscripts

Although no representation of torches[23] in Early English manuscripts resembles the Fuller Brooch’s mysterious objects identically, the same is true for cornucopias[24] or sceptres or even flowers or plants. Torches, however, are also depicted, in other manuscripts/sources, as being made up of similar long, thick, tubular structures ending in an inverted-cone shape, from which a multitude of tongue-like elements protrude. Examples can be found in illustrations featuring in a number of manuscripts from Early Medieval England. For instance, a torch is held by the Virgo zodiac sign within a calendar in London, British Library, Arundel 60, fol. 5 v.[25] Ælfric’s translation of Genesis in London, British Library, Cotton Claudius B.IV, features, on fols. 3 r,[26] 27r[27] and 38 r,[28] respectively: anthropomorphic representations of the sun and the moon, each carrying a torch; Abraham dreaming of a smoky furnace surrounded by nine torches; Abraham carrying a torch while leading Isaac to the place of sacrifice. An anthropomorphic representation of the moon holds two torches, one in each hand, within the Aratea, in London, British Library, Cotton Tiberius B.V (fols. 2–73 and 77–85), fol. 47 r.[29] A scene of the Crucifixion, filling a whole page in London, British Library, Cotton Titus D.XXVII, on fol. 65 v, shows anthropomorphic representations of sun and moon, holding a torch each, above the cross.[30] Various torches appear within the illustrations of the Psalter in London, British Library, Harley 603, on fols. 7 r,[31] 15 r,[32] 33 r,[33] 59r[34] and 71v[35]. Finally, an anthropomorphic figure holds two torches, one in each hand, in a historiated initial in the hymn “Invocatio ad sanctam trinitatem”, in Durham, Cathedral Library, B.III.32, on fol. 2 r.[36] All these torches are drawn differently, but they share the same basic elements listed above. So there is a certain amount of similarity, at least between the structure of torches and the objects portrayed on the Fuller Brooch. Bruce-Mitford showed in 1974 that a close representation of these protruding elements found on the Fuller Brooch, with rounded tips with two horizontal strokes, could be observed in some plant-like decorations in the Abingdon sword (1974: 315). The same pattern, however, is found in the feathers of the peacocks in the ring of Æthelwulf (see Pratt 2003: 208), and it is therefore not exclusive to plants. Moreover, the tongue-like elements from the Abingdon sword emerge from the stem at different heights, like the leaves of a plant from a stem, while on the Fuller Brooch these protruding elements all start from the same level. This peculiar feature of the objects depicted on the Fuller Brooch has parallels in the depictions of the flames of the torches featuring in the illustrations listed above.

In many of these illustrations, torches are used figuratively to represent natural light. Heavenly bodies emitting light, like the sun and the moon, are frequently personified, that is depicted as anthropomorphic characters holding torches, as in the Genesis creation scene in London, British Library, Cotton Claudius B.IV, fol. 3 r; in the Aratea in London, British Library, Cotton Tiberius B.V (fols. 2–73 and 77–88), fol. 47 r (the moon here holding two torches), and in the Crucifixion scene in London, British Library, Cotton Titus D.XXVII, fol. 65 v. In a Carolingian witness of Martianus Capella’s De nuptiis, from Tours, dated to the middle of the ninth-century (Bamberg, Staatsbibliothek, Msc.Class.5, fol. 9v), Astrologia is also depicted as holding two torches (here both in one hand), representing the sun and the moon.

In some cases, torches are portrayed in the hands of the creator of both light and light-emitting heavenly bodies, that is God himself. In a Psalter illustration from London, British Library, Harley 603, fol. 33 r, for example, God is portrayed holding both the sun and a torch, presumably representing the light of the sun or the moon.[37]

There are some illustrations, however, that clearly depict torches as representations of wisdom as ‘divine light’, allowing human beings to see truth and escape fear and dangers. This use is particularly evident in the illustrations of the ninth-century Carolingian Utrecht Psalter,[38] as well as in its later English ‘copies’[39] – that is the Harley Psalter,[40] Eadwine Psalter,[41] and Paris Psalter,[42] – which will be discussed in the following section.

4 The Use of Torches to Represent ‘Divine Light’ in the Utrecht Psalter and in its English Copies

A torch used as a representation of ‘divine light’ appears in two illustrations of the Utrecht Psalter, where it is held by God, who pours the light coming from its flames onto the psalmist’s eyes. In the illustration to Psalm 12 (13), on fol. 7 r (see Figure 2), the psalmist is portrayed facing and indicating some enemies equipped with bows, arrows, spears and shields.[43] A ray issuing from God’s torch illuminates the eyes of the psalmist. The text of the Psalm (v. 1–5) clarifies the figurative meaning of the torch:

1 [...] Usquequo Domine oblivisceris me in finem? Usquequo avertis faciem tuam a me?

2 Quamdiu ponam consilia in anima mea, dolorem in corde meo per diem?

3 Usquequo exaltabitur inimicus meus super me?

4 Respice, exaudi [MS et exaudi] me Domine Deus meus. Inlumina oculos meos ne umquam obdormiam in mortem [MS morte].

5 Nequando dicat inimicus meus: Praevalui adversus eum. Qui tribulant me, exultabunt si motus fuero. (Weber and Fisher 1969: 780–782)[44]

1 ‘How long, O Lord, wilt thou forget me unto the end? How long dost thou turn away thy face from me?

2 How long shall I take counsels in my soul, sorrow in my heart all the day?

3 How long shall my enemy be exalted over me?

4 Consider, and hear me, O Lord my God. Enlighten my eyes that I never sleep in death.

5 Lest at any time my enemy say: I have prevailed against him. They that trouble me will rejoice when I am moved.’ [45]

The psalmist seeks protection in God against his enemies, who in the image are portrayed as physical warriors with military weapons. These enemies are the psalmists’s internal struggles, that is, his thoughts and sorrows. This protection, we are told, must come in the shape of divine light illuminating his eyes (Inlumina oculos meos ‘Enlighten my eyes’), and allowing him to flee from death. The only way in which a light illuminating the eyes of the psalmist can save him from death is by allowing him to ‘see’ (and comprehend) divine truth; to ‘see’ the essence of God/Christ; to ‘see’ the right path and escape damnation. The expressions inimicus meus ‘my enemy’ and mortem ‘death’ must therefore be intended primarily, here, in a moral sense. And the light is clearly, once again, divine wisdom, allowing the intellect (that is, the eyes of the mind) to perceive truth. A similar image of God pouring the light of a flaming torch onto the psalmist’s eyes, again as an illustration to Psalm 12 (13), appears in the Harley Psalter, fol. 7 r; the Eadwine Psalter, fol. 21 r; the Paris Psalter, fol. 21 r; and – in a much simplified version and context – in the Odbert Psalter, fol. 19 v,[46] and in the Bury St Edmund Psalter, fol. 28 r.[47] In the Odbert Psalter, the artist added a tiny inscription as a caption beside the illustration, above the psalmist’s head, reading inlumina oculos ‘enlighten my eyes’ (Noel 1996: 131; see Figure 6). Bolens (2022: 14) has noted that the shape of the flames in this illustration, in the Utrecht Psalter and its copies, is rather unusual, as they project sideways and downwards towards the psalmist, a feature which is also visible on the Fuller Brooch.[48]

The same ‘protective’ function of this divine light is reiterated on fol. 15 r of the Utrecht Psalter, where Psalm 26 (27) begins with the words Dominus inluminatio mea, et salus mea, quem timebo? ‘The Lord is my light and my salvation, whom shall I fear?’ (Weber and Fisher 1969: 798). The illustration of this Psalm (see Figure 3) depicts God holding both a torch and the hand of the psalmist. The hand of God, appearing from the sky, emits some rays which touch the torch and then descend on the psalmist’s head. The enemies of the psalmist fall from their horses (as a consequence).[49] The illustration makes clear that it is the light coming from the torch held by God that protects the psalmist, because it has been endowed with ‘divine light’, that is divine wisdom, illuminating and thus saving the psalmist. The same illustration is found in the Harley Psalter, fol. 15 r; the Eadwine Psalter, fol. 44 v; and the Paris Psalter, fol. 44 v.

The Utrecht Psalter was very likely produced in the Benedictine monastery of Hautvillers, near Rheims (Goldschmidt 1892 and Durrieu 1895). Although it is dated to the first half of the ninth century (c. 816–833),[50] and can therefore be thought to derive from a historical context revolving around the characters of Emperor Louis the Pious, his eldest son Lothair, and his counsellor Ebbo (Archbishop of Rheims), the manuscript can also be connected with Charles the Bald’s circle. As van der Horst states, there is evidence that the manuscript was well known to the artists that were active in Charles the Bald’s Court School around the middle of the ninth century (1996: 23–34 and 82). The representation of the bestowing of ‘divine light’ featuring in the Utrecht Psalter as an illustration to Psalm 26 (27) analysed above is also portrayed on one of the ivory plaques that may have once covered the Prayerbook of Charles the Bald,[51] and that certainly stem from his Court School. Here the torch is clearly visible but the rays emanating from the Hand of God have been omitted (see Figure 4), probably as it was difficult for the artist to carve them.[52] The ivory plaque shows that this protective ‘divine light’ was a key concept within Carolingian culture in general and at Charles the Bald’s Court School in particular.

The illustrations in the Utrecht Psalter therefore very likely represented some conceptual interpretations of the Psalms that were still current at Charles’s Court School, and presumably influenced those intellectual figures that had cultural relationships with that court or with its wide affiliations. Among these figures, we can count also King Alfred and his scholarly helpers.

Van der Horst considers the possibility that the Utrecht Psalter might have reached England much earlier than the year 1000, perhaps even during Alfred’s life, via Charles’s daughter Judith:

It is not known how and why the manuscript came to be in Canterbury in the first place. It is generally believed to have arrived around the year 1000 [...]. But it cannot be excluded that the Utrecht Psalter was in England even earlier than that, because England frequently had close contacts with Europe in the ninth and tenth centuries. For example, in 856 Aethelwulf, King of Wessex and father of King Alfred, married Judith, the daughter of Charlemagne’s grandson Charles the Bald. [...] perhaps it [i. e. the Utrecht Psalter] had even been in the possession of Charles’s daughter Judith, given in marriage to the English king. (van der Horst 1996: 34)

Even without taking into account the possibility of an early arrival of the Utrecht Psalter itself in England, for which we have no evidence, the influence of its iconography might have reached England already in the ninth century. The young Alfred spent some time at the court of Charles the Bald with his father, around 856, and he could have seen the Utrecht Psalter on that occasion. We know for certain, however, that even later King Alfred had contacts with Charles’s entourage and with Rheims, since he had a correspondence with Fulco, a palace cleric of Charles, later abbot of Saint-Bertin and archbishop of Rheims (883).[53] Fulco then sent Grimbald from Saint-Bertin to Wessex, where Alfred appointed him as one of his scholar-helpers.

Pratt (2003) and Webster (2003a: 102) also dwell on the connection that can be made between the beliefs, the literary works and the objects that can be ascribed to Alfred’s cultural milieu, and those pertaining to Charles’s Court School. Even the admiration for the wise King Solomon, they argue, was partly mediated through Carolingian models. And it is possible that these models also included the iconography of torches to represent ‘divine light’, as featured in the Utrecht Psalter and in Charles the Bald’s Court School’s ivory cover mentioned above.

Both Kempshall (2001: 118) and Webster (2003a: 102), moreover, underline Alfred’s love of the Psalms, which can also be inferred from the Vita Ælfredi. It is a fact, after all, that a prose translation of the first fifty Psalms was produced within King Alfred’s cultural agenda, and possibly by the king himself.[54] Alfred was therefore undoubtedly very familiar with the concepts of ‘enlightenment’ and ‘divine light’ which emerge from the Psalms.

The Utrecht Psalter’s torches certainly influenced artist F (Noel 1995: 212–213) working on the Harley Psalter, where some further representations of divine torches, along the same conceptual lines, appear in illustrations on fol. 59 r for Psalm 115 (116),[55] and on fol. 71 v for Psalm 139 (140).[56] In the latter case, in particular, God holds two torches, one in each hand, as on the Fuller Brooch (see Figure 5).[57] And again he pours the flames on the psalmist, to enlighten his eyes, thus protecting him from his enemies. In Ohlgren’s words:

In the center, the Psalmist, being attacked by enemies with ropes (v. 6) who also have serpents issuing from their mouths (v. 4), cries out to God, who, leaning out of his mandorla, pours the contents of a flaming torch on the Psalmist (v. 8). (Ohlgren 1986: no. 169/112).

Artist F was very innovative. His work technique is analysed extensively by Noel (1995: 77–88), who concludes that “he looked very hard at Utrecht’s images, and adapted motifs from other Psalms to his requirements”. In this case, in particular, he creates a new divine-torches scene by conflating the slim torches from Utrecht Psalms 12 (13) and 26 (27) (Figures 2 and 3), and the divine-torch scene from the Odbert/Bury tradition, with its conspicuous torch held upside down.[58] The psalmist invokes God’s protection,[59] and this protection once again is granted in the shape of a (huge) flame coming from God, holding two torches, one in each hand. The parallel with the Fuller Brooch is striking, and although the Harley Psalter is much later, this illustration proves that the concept of the ‘divine light’ could be equally expressed with two torches. It also shows that artist F deemed it necessary to deviate from his source in order to put greater emphasis on this concept.[60]

Summing up, Alfred’s circle’s intellectual focus on the oculi mentis and the role of ‘enlightenment’ and ‘divine light’ in this process, as highlighted above, make torches plausible candidates for the objects held by sight on the Fuller Brooch. This interpretation seems reinforced by the iconography of this ‘divine light’ as emerging from the Utrecht Psalter (and its adapted ‘copies’), also on the basis of the close cultural connections that can be observed between Alfred’s cultural milieu and Charles the Bald’s Court School.

The iconography of this morally enlightening function of the flaming torch, however, is not limited to the Utrecht Psalter and its derivatives: it can also be seen in Cotton Tiberius C.VI, fol. 18 v,[61] in a full-page miniature preceding the prefaces to the Psalter, where Christ is portrayed holding a cross, a book and a flaming, horn-shaped torch, and in the historiated initial of the hymn “Invocatio ad sanctam trinitatem” in the Durham Hymnal, which will be analysed in the next section (5), where God/Light holds a torch in each hand, as in the Harley Psalter, fol. 71 v, and on the Fuller Brooch.[62]

5 The Hymn Invocatio ad sanctam trinitatem in the Durham Hymnal

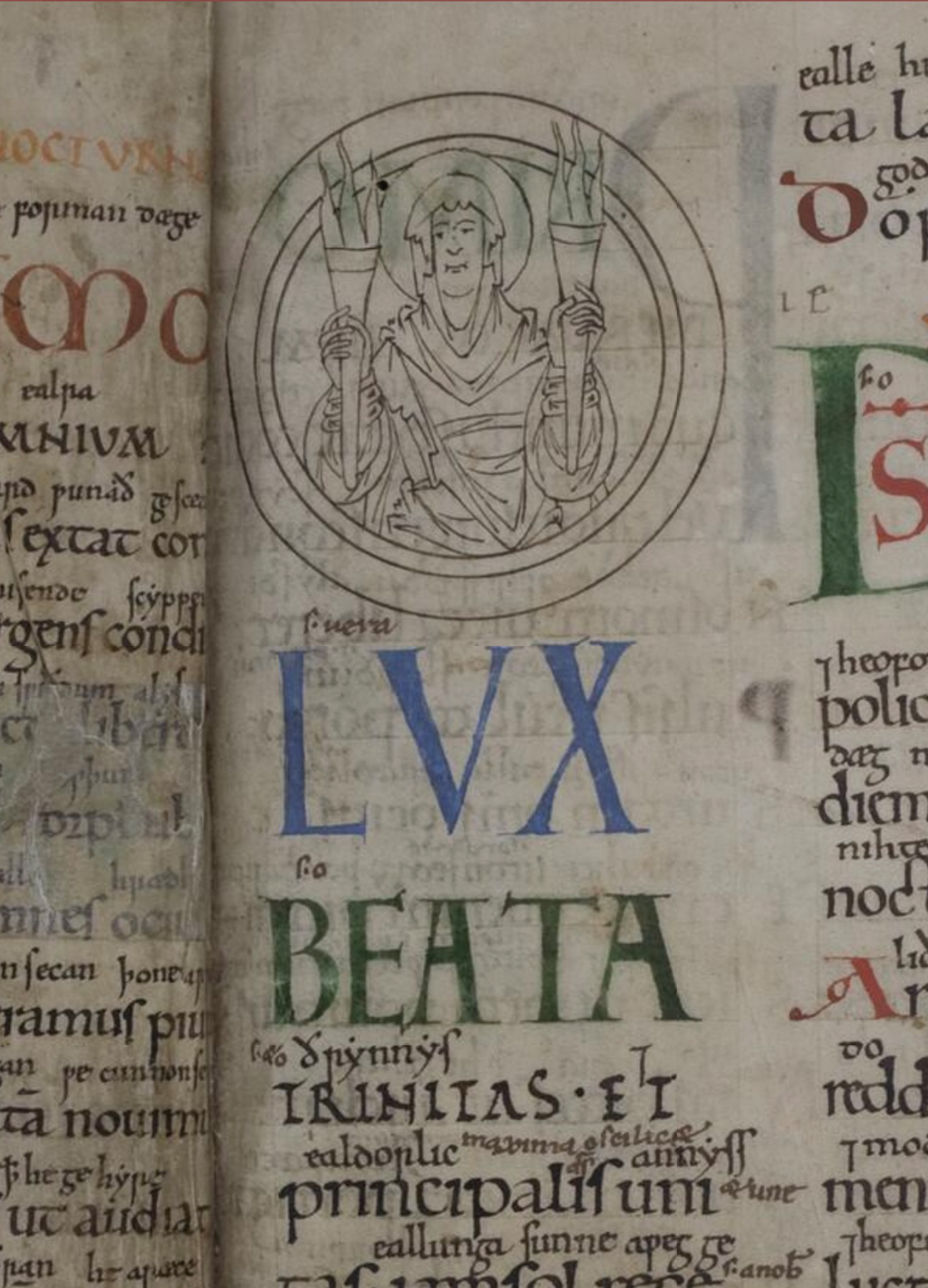

Another important contribution to my argument comes from an eleventh-century Canterbury hymnal now in Durham (Cathedral Library, B.III.32), where the first hymn (“Invocatio ad sanctam trinitatem”, beginning with the words O lux beata Trinitas, fol. 2r) is introduced by a historiated initial ‘O’ containing a depiction of a character holding two burning torches, and which closely resembles the iconography found on the Fuller Brooch (see Figure 7).[63] The Latin word LUX ‘light’ appears right beneath the image, as if it were a modern caption. The first stanza of this vesper hymn – meant to be sung on Saturday evening (Milfull 1996: 475) – discusses the way in which, once the sun has gone down and darkness has stepped in, human beings have to turn to God for enlightenment and reassurance. The Trinity of Light (Lux, beata Trinitas) becomes the sun in times of darkness, brightening the life of men and reassuring their hearts through its powerful light (Lat. lumen, translated as leoht in the accompanying Old English continuous interlinear gloss):

O LUX, BEATA TRINITAS

ET PRINCIPALIS UNItas,

iam sol recedit igneus;

infunde lumen cordibus.

eala þu [...] þu eadige þrynnes

⁊ ealdorlic annys

eallunga sunne aweggewit seo fyrenne

onageot ł asænd leoht heortum

‘O Light, blessed Trinity

and sovereign Unity,

already the fiery sun is setting;

[therefore] fill our hearts with light.’ (Milfull 1996: 109)[64]

Temple (1976) and Ohlgren (1986) have interpreted the character found in the initial ‘O’ as a “personification of light”, in the shape of a female figure;[65]Keefer (2007: 99), however, has challenged this view and claims that “it could as readily represent not a female but one of the Persons of the Trinity as well”. She observes that “it is God who holds all images of the lighted torch in London, British Library, Harley 603” and also in Vatican City, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Reg. lat. 12, fol. 28 r. The topic, argument and invocation of the hymn would seem to confirm that this person might figuratively represent both light and God/Christ/Holy Spirit at the same time, since there is obviously a complete overlap between the Trinity and light, as they are combined in one entity (Lux, beata Trinitas ‘Light, blessed Trinity’).

Thus the Trinity is here understood as light chasing away darkness and allowing human beings to see at night, when the sun is gone. Night makes human beings vulnerable, and represents, also figuratively, a time of fear and turmoil. The light of the Trinity comforts men and allows them to overcome both their fear and the dangers of dark times, saving their bodies and souls.[66]

Although much later than the Fuller Brooch, this historiated initial shows that the iconography of a character holding two torches in order to represent the ability to see and overcome dangers with the help of divine light was not limited to the Psalter, but could also feature in other types of texts. It also shows that the imagery of a lighted torch, with the ability to chase away darkness, would make a very suitable metaphor to represent Alfred’s aspirations and preoccupations as a king. In a ninth-century historical and cultural context, characterised by the urge to fight against a widespread cultural decay, with Viking attacks heavily threatening the political, religious and social stability of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, the image of a divine light allowing the king and his people to see the right path, through wisdom and the protection of God, and be led to safety and salvation, would have been very powerful. This protective element is well aligned with the protective function of the divine torches that can be found in the Utrecht Psalter and its later copies.

6 Conclusions

The sense of sight is central to the iconography of the Fuller Brooch, where it should be considered as a representation not only of physical vision, but also and primarily of the human intellect (the oculi mentis ‘eyes of the mind’), aiming to see God through wisdom.[67] The patristic commonplace of the oculi mentis was very central to the theological and philosophical beliefs pertaining to King Alfred’s cultural circle, and was very tightly connected with the concept of the illuminatio ‘illumination’, that is, the bestowing of divine light on the (spiritual) eyes of human beings, to make their intellect able to see spiritual truths and God himself. The brooch seems to embody Alfred’s main ideas of education and moral and political behaviour very closely. As Webster very aptly sums up:

The brooch, superb in its craftmanship and subtle in its intellectual content, is a powerful embodiment of Alfred’s ideas about the importance of wisdom and its acquisition – by himself, by his nobility, by his clergy and by the next generation who would govern after him. Its seriousness of import is so close to Alfred’s thinking that it is hardly possible to see it as other than commissioned by the king himself – if not for his own personal use, then for one of those among his family, entourage, or churchmen who were also dedicated to the pursuit of wisdom. (Webster 2014: 66).

Divine light was a pivotal element within the process of illumination of the oculi mentis, and therefore a concept very firmly associated with spiritual sight, as the Old English translations of the Soliloquia, the Consolatio Philosophiae and the Regula pastoralis clearly show. The two still mysterious objects that the central character on the Fuller Brooch holds must be linked to the concept of spiritual sight and to the elements of the oculi mentis commonplace. Given the relevance of the concept of divine light in the illuminatio process, and given the shape of these objects on the brooch, resembling torches found in other early medieval English manuscripts, a case can be made for these unidentified objects to represent the torches of divine light, turning physical sight into spiritual perception.

This divine light, within the process of illumination and divine protection, can also be observed, iconographically, in the same form of torches, in the Utrecht Psalter and in other objects stemming from Charles the Bald’s Court School, such as an ivory plaque replicating the Utrecht illustration to Psalm 26 (27). This similarity reinforces this interpretation. Moreover, given the political and cultural connections between the courts and cultural circles of Charles the Bald and King Alfred, it appears reasonable to surmise that the Utrecht Psalter might have acted as a source of inspiration,[68] albeit indirectly, mediated through close contacts with the Court School of Charles the Bald.[69]

In my view, the central focus of the object is wisdom, good leadership and salvation: all concepts that were very relevant to King Alfred and his circle. Divine light is the empowering element; torches are its physical representations. The central character is probably hard to define because he may represent simultaneously – in a multilayer mode so typical of early English art – physical sight, spiritual sight, light, wisdom, God, and also perhaps King Alfred or Archbishop Plegmund[70] themselves. The protective function of the divine light, as the historiated initial ‘O’ of the hymn “Invocatio ad sanctam trinitatem”, in the Durham Hymnal, suggests, was probably also intended as much needed to guide and defend, in times of spiritual darkness, the king, his people, and late ninth-century Anglo-Saxon kingdoms from Viking attacks.[71]

The Fuller Brooch © The Trustees of the British Museum

Illustration of Psalm 12 in Utrecht, Universiteitsbibliotheek, Psalterium Latinum (Hs. 32), fol. 7r (detail) © Utrecht, Universiteitsbibliotheek

Illustration of Psalm 26 in Utrecht, Universiteitsbibliotheek, Psalterium Latinum (Hs. 32), fol. 15r (detail) © Utrecht, Universiteitsbibliotheek

The ivory bookcover (Schweizerisches Nationalmuseum Zürich, AG 1311) derived from the Utrecht Psalter’s illustration to Psalm 26 © Schweizerisches Nationalmuseum

Illustration of Psalm 139 in London, British Library, Harley 603, fol. 71 v (detail) © British Library Board

Illustration of Psalm 12 in Boulogne-sur-Mer, Bibliothèque Municipale des Annonciades, 20, fol. 19v (detail) © Bibliothèque Municipale de Boulogne-sur-Mer

Historiated initial in Durham, Cathedral Library, B.III.32, fol. 2 r (detail). Reproduced by kind permission of the Chapter of Durham Cathedral © Dean and Chapter of Durham Cathedral

Works Cited

Bakka, Egil. 1966. “The Alfred Jewel and Sight”. Antiquaries Journal 46: 277–282. 10.1017/S0003581500053294Search in Google Scholar

Bately, Janet M. 2009. “Did King Alfred Actually Translate Anything? The Integrity of the Alfredian Canon Revisited.” Medium Ævum 78: 189–215.10.2307/43632837Search in Google Scholar

Blurton, T. Richard. 1997. The Enduring Image: Treasures from the British Museum. London: The British Council. Search in Google Scholar

Bolens, Guillemette. 2022. “Kinesic Intelligence, Medieval Illuminated Psalters, and the Poetics of the Psalms”. Studia Neophilologica (online): 1–24.10.1080/00393274.2022.2051733Search in Google Scholar

Bosworth, Joseph and T. Northcote Toller (eds.). 1898–1921. An Anglo-Saxon Dictionary. Oxford, Oxford University Press. Available in an online version at <https://bosworthtoller.com/>.Search in Google Scholar

Bruce-Mitford, Rupert L. S. 1956. “Late Saxon Disc-Brooches”. In: Donald B. Harden (ed.). Dark-Age Britain, Studies presented to E. T. Leeds. London: Methuen. 173–190.Search in Google Scholar

Bruce-Mitford, Rupert L. S. 1974. Aspects of Anglo-Saxon Archaeology: Sutton Hoo and Other Discoveries. New York: Gollancz.Search in Google Scholar

Carnicelli, Thomas A. (ed.). 1969. King Alfred’s Version of St. Augustine’s Soliloquies. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Caseau, Béatrice. 2014. “The Senses in Religion: Liturgy, Devotion, and Deprivation”. In: Richard G. Newhauser (ed.). A Cultural History of the Senses in the Middle Ages. London: Bloomsbury. 89–110.10.5040/9781474233156.ch-004Search in Google Scholar

Chazelle, Clelia. 1997. “Archbishops Ebo and Hincmar of Reims and the Utrecht Psalter”. Speculum 72: 1055–1077.10.2307/2865958Search in Google Scholar

Discenza, Nicole Guenther and Paul E. Szarmach (eds.). 2014. A Companion to Alfred the Great. Leiden: Brill.10.1163/9789004283763Search in Google Scholar

Douay-Rheims Bible = The Challoner Revision of the Douay-Rheims Bible. 1899. Ed. Rev. Richard Challoner. Baltimore, MD: John Murphy. <http://www.intratext.com/x/eng0011.htm>.Search in Google Scholar

Durrieu, Paul. 1895. L’origine du manuscrit célèbre dit le Psautier d’Utrecht. Paris: Leroux.Search in Google Scholar

Fasolini, Diego. 2005. “‘Illuminating’ and ‘Illuminated’ Light: A Biblical-Theological Interpretation of God-as-Light in Canto XXXIII of Dante's Paradiso”. Literature and Theology 19: 297–310.10.1093/litthe/fri039Search in Google Scholar

Fera, Rosa Maria. 2012. “Metaphors for the Five Senses in Old English Prose”. The Review of English Studies 63: 709–731.10.1093/res/hgr012Search in Google Scholar

Gallagher, Robert. 2019. “King Alfred and the Sibyl: Sources of Praise in the Latin Acrostic Verses of Bern, Burgerbibliothek, 671”. Early Medieval Europe 27: 279–298.10.1111/emed.12331Search in Google Scholar

Gameson, Richard. 1992. “Manuscript Art at Christ Church, Canterbury, in the Generation after St Dunstan”. In: Nigel Ramsey, Margaret Sparks and Tim W. T. Tatton-Brown (eds.). St Dunstan: His Life, Times and Cult. Woodbridge: Boydell. 187–220.Search in Google Scholar

Gannon, Anna. 2005. “The Five Senses and Anglo-Saxon Coinage”. Anglo-Saxon Studies in Archaeology and History 13: 97–104.10.2307/j.ctt1w0df0s.11Search in Google Scholar

Gneuss, Helmut, and Michael Lapidge. 2014. Anglo-Saxon Manuscripts: A Bibliographical Handlist of Manuscripts and Manuscript Fragments Written or Owned in England up to 1100. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.10.3138/9781442616288Search in Google Scholar

Godden, Malcolm. 2007. “Did King Alfred Write Anything?”. Medium Ævum 76: 1–23.10.2307/43632294Search in Google Scholar

Godden, Malcolm. 2009. “The Alfredian Project and Its Aftermath: Rethinking the Literary History of the Ninth and Tenth Centuries”. Proceedings of the British Academy 162: 93–122.10.5871/bacad/9780197264584.003.0005Search in Google Scholar

Godden, Malcolm and Susan Irvine (eds.), with a chapter on the Metres by Mark Griffith and contributions by Rohini Jayatilaka. 2009. The Old English Boethius: An Edition of the Old English Versions of Boethius’s De Consolatione Philosophiae. 2 vols. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Goldschmidt, Adolf. 1892. “Der Utrechtpsalter”. Repertorium für Kunstwissenschaft 15: 156–169.10.1515/9783111441702-013Search in Google Scholar

Hindley, Katherine. 2016. “Sight and Understanding: Visual Imagery as Metaphor in the Old English Boethius and Soliloquies”. In: Annette Kern-Stähler, Beatrix Busse and Wietse de Boer (eds.). The Five Senses in Medieval and Early Modern England. Leiden/Boston, MA: Brill. 21–35.Search in Google Scholar

Hinton, David A. 1974. A Catalogue of the Anglo-Saxon Ornamental Metalwork 700–1100 in the Department of Antiquities Ashmolean Museum. Oxford: Clarendon.Search in Google Scholar

Hinton, David A. 2008. The Alfred Jewel and Other Late Anglo-Saxon Decorated Metalwork. Oxford: Ashmolean Museum.Search in Google Scholar

Hoek, Michelle C. 1997. “Anglo-Saxon Innovation and the Use of the Senses in the Old English Physiologus Poems”. Studia Neophilologica 69: 1–10.10.1080/00393279708588191Search in Google Scholar

van der Horst, Koert. 1996. “The Utrecht Psalter: Picturing the Psalms of David”. In: Koert van der Horst, William Noel and Wilhelmina C. M. Wüstefeld (eds.). The Utrecht Psalter in Medieval Art: Picturing the Psalms of David. Tuurdijk: Hes. 23–84.10.1163/9789004613416_008Search in Google Scholar

Howlett, David R. 1974. “The Iconography of the Alfred Jewel”. Oxoniensia 39: 44–52.Search in Google Scholar

Keefer, Sarah Larratt. 2007. “Use of Manuscript Space for Design, Text and Image in Liturgical Books Owned by the Community of St Cuthbert”. In: Sarah Larratt Keefer and Rolf H. Bremmer (eds.). Signs on the Edge: Space, Text and Margin in Medieval Manuscripts. Paris/Leuven/Dudley, MA: Peeters. 85–115.Search in Google Scholar

Kempshall, Matthew. 2001. “No Bishop, No King: The Ministerial Ideology of Kingship and Asser’s Res gestae Aelfredi”. In: Richard Gameson and Henrietta Leyser (eds.). Belief and Culture in the Middle Ages: Studies presented to Henry Mayr-Harting. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 106–127.Search in Google Scholar

Keynes, Simon and Michael Lapidge (eds.). 1983. Alfred the Great: Asser’s Life of King Alfred and Other Contemporary Sources. London/New York: Penguin.Search in Google Scholar

Laplantine, François. 2005. Le social et le sensible: Introduction à une anthropologie modale. Paris: Téraèdre. Search in Google Scholar

Lausberg, Heinrich. 1998. Handbook of Literary Rhetoric: A Foundation for Literary Study. Leiden, Boston, MA, and Köln: Brill.10.1163/9789004663213Search in Google Scholar

Milfull, Inge B. (ed.). 1996. The Hymns of the Anglo-Saxon Church: A Study and Edition of the ‘Durham Hymnal’. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Musto, Jeanne-Marie. 2001. “John Scottus Eriugena and the Upper Cover of the Lindau Gospels”.Gesta 40: 1–18.10.2307/767192Search in Google Scholar

Nelson, Janet L. 1997. “‘sicut olim gens Francorum ... nunc gens Anglorum’: Fulk’s Letter to Alfred Revisited”. In: Jane Roberts and Janet L. Nelson, with Malcolm Godden (eds.). Alfred the Wise: Studies in Honour of Janet Bately on the Occasion of Her Sixty-Fifth Birthday. [...]. Cambridge: Brewer. 135–144.10.4324/9780429243196-5Search in Google Scholar

Noel, William. 1995. The Utrecht Psalter. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Noel, William. 1996. “The Utrecht Psalter in England: Continuity and Experiment”. In: Koert van der Horst, William Noel and Wilhelmina C. M. Wüstefeld (eds.). The Utrecht Psalter in Medieval Art: Picturing the Psalms of David. Tuurdijk: Hes. 121–165.10.1163/9789004613416_011Search in Google Scholar

O’Brien O’Keeffe, Katherine. 2016. “Hands and Eyes, Sight and Touch: Appraising the Senses in Anglo-Saxon England”. Anglo-Saxon England 45: 105–140.10.1017/S0263675100080248Search in Google Scholar

Ohlgren, Thomas H. (ed.). 1986. Insular and Anglo-Saxon Illuminated Manuscripts. An Iconographic Catalogue c. A.D. 625 to 1100. New York and London: Garland.Search in Google Scholar

O’Neill, Patrick (ed.). 2001. King Alfred’s Old English Prose Translation of the ‘First Fifty Psalms’. Cambridge, MA: Medieval Academy of America Books. Search in Google Scholar

Panofsky, Dora. 1943. “The Textual Basis of the Utrecht Psalter Illustrations”. The Art Bulletin 25: 50–58.10.2307/3046861Search in Google Scholar

Pratt, David. 2003. “Persuasion and Invention at the Court of King Alfred the Great”. In: Catherine E. Cubitt (ed.). Court Culture in the Early Middle Ages: The Proceedings of the First Alcuin Conference. Turnhout: Brepols. 189–221.10.1484/M.SEM-EB.3.3825Search in Google Scholar

Scott, Thomas R. 2018. The Universe as It Really Is: Earth, Space, Matter, and Time. New York: Columbia University Press.10.7312/scot18494Search in Google Scholar

Temple, Elżbieta. 1976. Anglo-Saxon Manuscripts, 900–1066. London: Harvey Miller.Search in Google Scholar

Treharne, Elaine M. 1991. “‘They should not worship devils . . . which neither can see, nor hear, nor walk’: the Sensibility of the Virtuous and The Life of St. Margaret”. Proceedings of the PMR Conference 15: 221–236.Search in Google Scholar

Weber, Robert (ed.). 1953. Le psautier romain et les autres anciens psautiers latins. Rome: Abbaye Saint-Jérôme; Vatican City: Libreria Vaticana.Search in Google Scholar

Weber, Robert and Bonifatius Fisher (eds.). 1969. Biblia Sacra: Iuxta Vulgatam Versionem. Stuttgart: Württembergische Bibelanstalt.Search in Google Scholar

Webster, Leslie and Janet Backhouse. 1991. The Making of England: Anglo-Saxon Art and Culture, AD 600–900. London: British Museum.Search in Google Scholar

Webster, Leslie. 2003 a. “Aedificia nova: Treasures of Alfred’s Reign”. In: Timothy Reuter (ed.). Alfred the Great: Papers from the Eleventh-Centenary Conferences. Aldershot: Ashgate. 79–103.Search in Google Scholar

Webster, Leslie. 2003 b. “Encrypted Visions: Style and Sense in the Anglo-Saxon Minor Arts, AD 400–900”. In: Catherine E. Karkov and George Hardin Brown (eds.). Anglo-Saxon Styles. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. 11–30.Search in Google Scholar

Webster, Leslie. 2014. “The Art of Alfred and His Time” In: Nicole Guenther Discenza and Paul E. Szarmach (eds.). A Companion to Alfred the Great. Leiden: Brill. 47–81.10.1163/9789004283763_004Search in Google Scholar

Wilcox, Miranda. 2006. “Alfred’s Epistemological Metaphors: eagan modes and scip modes”. Anglo-Saxon England 35: 179–217.10.1017/S0263675106000093Search in Google Scholar

Woolgar, Christopher M. 2006. The Senses in Late Medieval England. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.10.1093/oso/9780199273492.003.0013Search in Google Scholar

Wright, Charles D. 2007. “Why Sight Holds Flowers: An Apocryphal Source for the Iconography of the Alfred Jewel and Fuller Brooch”. In: Alastair J. Minnis and Jane E. Roberts (eds.). Text, Image, Interpretation: Studies in Anglo-Saxon Literature and Its Insular Context in Honour of Éamonn Ó Carragáin. Turnhout: Brepols. 169–186.10.1484/M.SEM-EB.3.3796Search in Google Scholar

Wüstefeld, Wilhelmina C. M., in cooperation with William Noel and Koert van der Horst. 1996. “Catalogue”. In: Koert van der Horst, William Noel and Wilhelmina C. M. Wüstefeld (eds.). The Utrecht Psalter in Medieval Art: Picturing the Psalms of David. Tuurdijk: Hes. 167–255.Search in Google Scholar

© 2022 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Dieses Werk ist lizensiert unter einer Creative Commons Namensnennung 4.0 International Lizenz.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Frontmatter

- Light and Divine Wisdom: An Alternative Interpretation of the Iconography of the Fuller Brooch

- Tu beoð gemæccan: The Key Concept of Maxims I Representing One of the Fundamental Principles of the World Order

- Wulf and Eadwacer Reloaded: John of Antioch and the Starving Wife of Odoacer

- Sensational News about Nature: Risk and Resilience in Satirical Ozone Poetry of the Victorian Era

- Influences of George Gordon Byron on Asdren

- Construction of Identity/World and ‘Symbolic Death’: A Lacanian Approach to William Golding’s Pincher Martin

- The Anatomist of Love and Disease in Jeanette Winterson’s Written on the Body

- Conventions of the Ungendered Narrative

- “In My Mind’s Eye”: On the Relocation of Hamlet’s Story by Michael Almereyda

- ‘Force’ and ‘Chi’: Duality, Identity, and Struggle in Star Wars and Buchi Emecheta’s Kehinde

- Anxious Dynamics of Exile and the Ambivalence of Arab American Identity in Diana Abu-Jaber’s Crescent: Critical Reflections and Contemplations

- Between Remembering and Confession: A Refugee Narrative in Dina Nayeri’s Refuge

- Orfeo: A Posthuman Modern Prometheus. Uncommon Powers of Musical Imagination

- On Literary Apathy: Forms of Dis/Affection in My Year of Rest and Relaxation (2018)

- Reviews

- Roberta Frank. 2022. The Etiquette of Early Northern Verse. Conway Lectures in Medieval Studies 2010. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, xxx + 265 pp., $ 65.00.

- Claire Breay and Joanna Story (eds.), with Eleanor Jackson. 2021. Manuscripts in the Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms: Cultures and Connections. Dublin: Four Courts Press, xvii + 256 pp., numerous colour illustr., € 58.50.

- Mark Amsler. 2021. The Medieval Life of Language: Grammar and Pragmatics from Bacon to Kempe. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 264 pp., 2 figures, 2 tables, € 106.00.

- Alexandra Barratt and Susan Powell (eds.). 2021. The Fifteen Oes and Other Prayers: Edited from the Text Published by William Caxton (1491). Middle English Texts 61. Heidelberg: Winter, xxxvi + 54 pp., € 44.

- Carolin Gebauer. 2021. Making Time: World Construction in the Present-Tense Novel. Narratologia 77. Berlin/Boston, MA: De Gruyter, xvii + 378 pp., 5 tables, 5 illustr., € 99.95.

- Kai Wiegandt. 2019. J. M. Coetzee’s Revisions of the Human: Posthumanism and Narrative Form. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, ix + 280 pp., € 90.94.

- Linda K. Hughes, Sarah Ruffing Robbins and Andrew Taylor with Heidi Hakimi-Hood and Adam Nemmers (eds.). 2022. Transatlantic Anglophone Literatures, 1776–1920: An Anthology. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 808 pp., 60 illustr., £ 29.99/$ 39.95.

- Juliane Braun. 2019. Creole Drama: Theatre and Society in Antebellum New Orleans. Writing the Early Americas 4. Charlottesville, VA/London: The University of Virginia Press, 280 pp., 12 illustr., $ 69.50.

- Lisa Gotto. 2021. Passing and Posing between Black and White: Calibrating the Color Line in U. S. Cinema. Film Studies. Bielefeld: transcript, 247 pp., 30 figures, € 49.00.

- Daniel Stein. 2021. Authorizing Superhero Comics: On the Evolution of a Popular Serial Genre. Studies in Comics and Cartoons. Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Press, xv + 315 pp., 28 illustr., $ 34.95.

- Books Reviewed: Anglia 140 (2022)

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Frontmatter

- Light and Divine Wisdom: An Alternative Interpretation of the Iconography of the Fuller Brooch

- Tu beoð gemæccan: The Key Concept of Maxims I Representing One of the Fundamental Principles of the World Order

- Wulf and Eadwacer Reloaded: John of Antioch and the Starving Wife of Odoacer

- Sensational News about Nature: Risk and Resilience in Satirical Ozone Poetry of the Victorian Era

- Influences of George Gordon Byron on Asdren

- Construction of Identity/World and ‘Symbolic Death’: A Lacanian Approach to William Golding’s Pincher Martin

- The Anatomist of Love and Disease in Jeanette Winterson’s Written on the Body

- Conventions of the Ungendered Narrative

- “In My Mind’s Eye”: On the Relocation of Hamlet’s Story by Michael Almereyda

- ‘Force’ and ‘Chi’: Duality, Identity, and Struggle in Star Wars and Buchi Emecheta’s Kehinde

- Anxious Dynamics of Exile and the Ambivalence of Arab American Identity in Diana Abu-Jaber’s Crescent: Critical Reflections and Contemplations

- Between Remembering and Confession: A Refugee Narrative in Dina Nayeri’s Refuge

- Orfeo: A Posthuman Modern Prometheus. Uncommon Powers of Musical Imagination

- On Literary Apathy: Forms of Dis/Affection in My Year of Rest and Relaxation (2018)

- Reviews

- Roberta Frank. 2022. The Etiquette of Early Northern Verse. Conway Lectures in Medieval Studies 2010. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, xxx + 265 pp., $ 65.00.

- Claire Breay and Joanna Story (eds.), with Eleanor Jackson. 2021. Manuscripts in the Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms: Cultures and Connections. Dublin: Four Courts Press, xvii + 256 pp., numerous colour illustr., € 58.50.

- Mark Amsler. 2021. The Medieval Life of Language: Grammar and Pragmatics from Bacon to Kempe. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 264 pp., 2 figures, 2 tables, € 106.00.

- Alexandra Barratt and Susan Powell (eds.). 2021. The Fifteen Oes and Other Prayers: Edited from the Text Published by William Caxton (1491). Middle English Texts 61. Heidelberg: Winter, xxxvi + 54 pp., € 44.

- Carolin Gebauer. 2021. Making Time: World Construction in the Present-Tense Novel. Narratologia 77. Berlin/Boston, MA: De Gruyter, xvii + 378 pp., 5 tables, 5 illustr., € 99.95.

- Kai Wiegandt. 2019. J. M. Coetzee’s Revisions of the Human: Posthumanism and Narrative Form. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, ix + 280 pp., € 90.94.

- Linda K. Hughes, Sarah Ruffing Robbins and Andrew Taylor with Heidi Hakimi-Hood and Adam Nemmers (eds.). 2022. Transatlantic Anglophone Literatures, 1776–1920: An Anthology. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 808 pp., 60 illustr., £ 29.99/$ 39.95.

- Juliane Braun. 2019. Creole Drama: Theatre and Society in Antebellum New Orleans. Writing the Early Americas 4. Charlottesville, VA/London: The University of Virginia Press, 280 pp., 12 illustr., $ 69.50.

- Lisa Gotto. 2021. Passing and Posing between Black and White: Calibrating the Color Line in U. S. Cinema. Film Studies. Bielefeld: transcript, 247 pp., 30 figures, € 49.00.

- Daniel Stein. 2021. Authorizing Superhero Comics: On the Evolution of a Popular Serial Genre. Studies in Comics and Cartoons. Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Press, xv + 315 pp., 28 illustr., $ 34.95.

- Books Reviewed: Anglia 140 (2022)