Resumen

La fibrosis hepática se desarrolla como respuesta a la presencia de daño hepático crónico de diferentes etiologías, provocando un desequilibrio entre la síntesis y degeneración de la matriz extracelular y la desregulación de diversos mecanismos fisiológicos. En los estadios iniciales de las patologías crónicas, el hígado posee una elevada capacidad de regeneración, por lo que la detección temprana de la fibrosis hepática resulta esencial. En este contexto, es preciso contar con herramientas sencillas y económicas que permitan detectar la fibrosis hepática en sus fases iniciales. Para evaluar la fibrosis hepática, se han propuesto multitud de biomarcadores séricos no invasivos, tanto directos, como el ácido hialurónico o las metaloproteasas, como indirectos. Así mismo, se han desarrollado diversas fórmulas que combinan dichos biomarcadores junto con parámetros demográficos, como el índice FIB-4, el índice de fibrosis en la enfermedad de hígado graso no alcohólico (NFS, por sus siglas en inglés), la prueba ELF o el score de fibrosis Hepamet (HFS, por sus siglas en inglés). En el presente manuscrito, realizamos una revisión crítica del valor diagnóstico y pronóstico de los diferentes biomarcadores séricos y fórmulas actualmente existentes.

Introducción

La fibrosis hepática se desarrolla como consecuencia de la presencia de daño hepático crónico de diversas etiologías, entre las que se encuentran la hepatitis vírica, el abuso de alcohol, las enfermedades metabólicas como la enfermedad del hígado graso no alcohólico (NAFLD, de sus siglas en inglés), actualmente llamada enfermedad hepática esteatósica asociada a disfunción metabólica (MASLD, de sus siglas en inglés) [1], las enfermedades autoinmunes y las enfermedades hepáticas colestásicas [2, 3]. Esta patología se desarrolla debido a la desregulación del mecanismo fisiológico de remodelado, la activación de los miofibroblastos, y la formación de una cicatriz fibrótica que, con el tiempo, puede acabar produciendo cirrosis [4]. En todas las patologías de fibrosis hepática, se produce un desequilibrio entre la síntesis y la degeneración de la matriz extracelular (MEC), que afecta a la estructura y propiedades del hígado [5]. Aunque el hígado tiene una gran capacidad de regeneración, cuando el daño es persistente, dicha regeneración evoluciona hacia enfermedades crónicas como la fibrosis, que se caracteriza por la acumulación excesiva de MEC [6, 7]. La fibrosis hepática puede ser reversible, especialmente cuando se encuentra en sus fases iniciales [4], antes de que se desarrolle cirrosis y se produzca un fallo orgánico. De este modo, resulta crucial establecer un tratamiento adecuado lo antes posible. Tal como se demuestra en los estudios tanto en modelos experimentales como en pacientes, la regeneración del hígado se ve limitada en la enfermedad hepática avanzada [8].

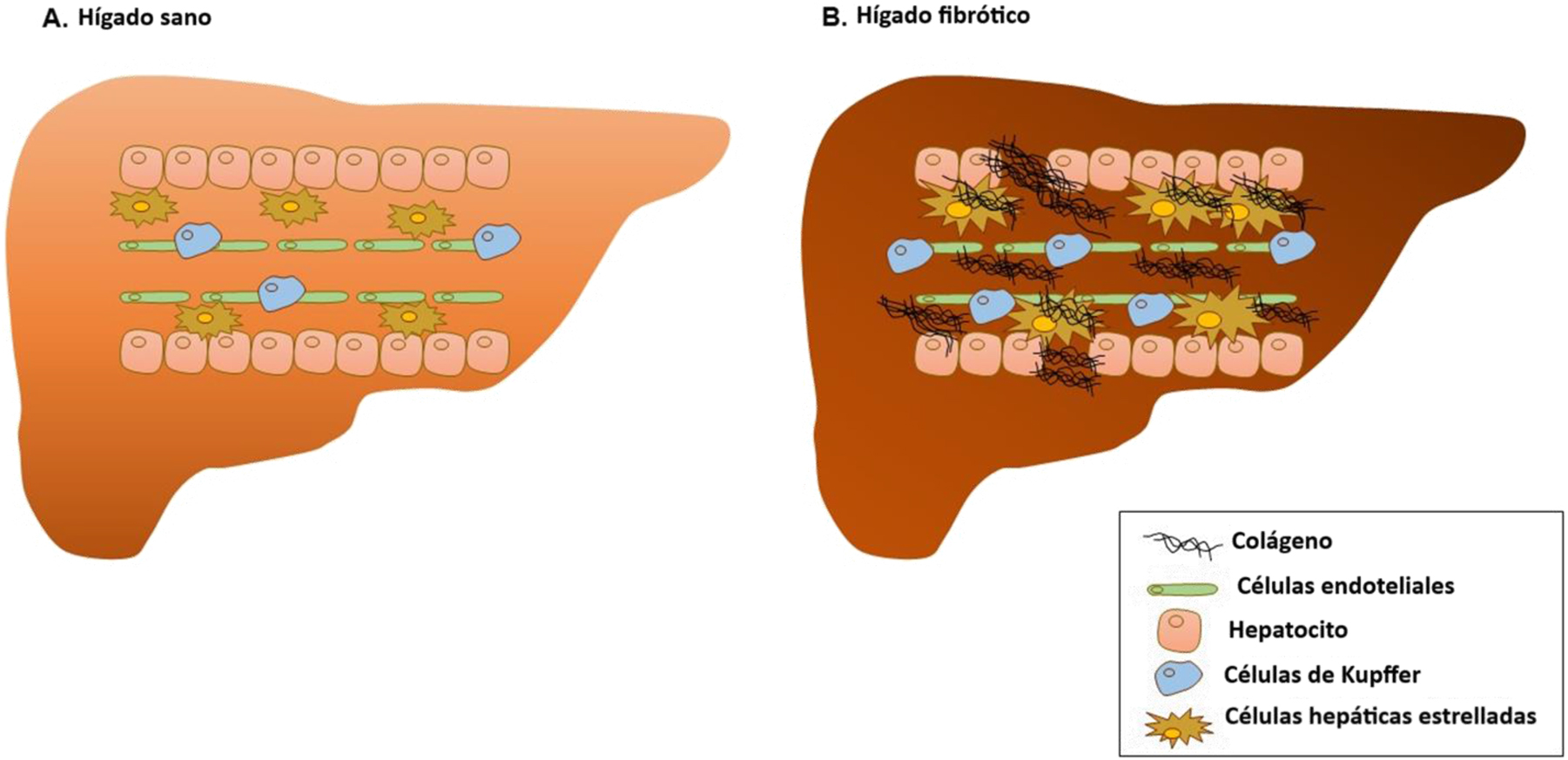

El daño hepático produce una lesión a nivel de los hepatocitos y afecta a la homeostasis, provocando inflamación [9]. Esta situación provoca una respuesta proinflamatoria de las células de Kupffer, así como la infiltración de las células inmunes, que favorecen la activación y diferenciación de las células estrelladas hepáticas (CEH) en miofibroblastos productores de colágeno [10, 11]. Las CEH controlan la remodelación de la MEC, un proceso que suelen equilibrar los mecanismos antifibróticos, que desactivan el miofibroblasto o estimulan su apóptosis [10]. En las enfermedades hepáticas crónicas, la activación del miofibroblasto provoca una reducción de las metaloproteinasas (MMP, por sus siglas en inglés), la elevación de los inhibidores de MMP (TIMP), y la secreción de la proteína de unión a Mac-2 con aglutinina positiva de Wisteria floribunda (WFA+-M2BP) [12], que están implicadas en la degradación de la MEC. Las MMP son las principales enzimas implicadas en la degradación de la MEC, teniendo las TIMP capacidad para regular las actividades proteolíticas de las MMP en los tejidos [13]. Así mismo, las CEH activadas son los factores que más contribuyen a la acumulación de colágeno en el espacio de Disse, provocando el engrosamiento gradual de dicho espacio, y por tanto un incremento de la presión portal. Como consecuencia, se produce una acumulación excesiva de colágeno, que afecta a la capacidad de regeneración de la matriz, derivando en un incremento de la rigidez hepática [14] (Figura 1).

Diferencias entre un hígado sano y un hígado fibrótico.

Actualmente, el método de referencia para evaluar el grado de fibrosis hepática sigue siendo la biopsia hepática, en la que se aplican diversos sistemas de puntuación histopatológica, como METAVIR, que es la más utilizada, en la que se establecen cuatro fases de evolución de la fibrosis hepática: F0, sin fibrosis; F1, fibrosis leve (fibrosis portal sin septos); F2, fibrosis moderada (fibrosis portal con escasos septos); F3, fibrosis avanzada (numerosos septos sin cirrosis); y F4, cirrosis [15]. Las limitaciones de la biopsia hepática son ampliamente conocidas: invasividad de la técnica, mala tolerancia, variabilidad en la toma de muestras, coste elevado, y variabilidad interobservador en la interpretación [16]. En este contexto, es necesario desarrollar e incluir otros biomarcadores no invasivos para el diagnóstico y evaluación de la evolución de la enfermedad hepática.

En este manuscrito hemos llevado a cabo una revisión crítica de los biomarcadores séricos de fibrosis hepática. Los biomarcadores directos son aquellos relacionados con el proceso de formación y degradación de la MEC o con la patogénesis molecular de la fibrogénesis y la fibrinólisis. Por otra parte, los biomarcadores indirectos se definen como aquellos parámetros bioquímicos que reflejan alteraciones en la función hepática y daño hepático [17].

Biomarcadores indirectos

Enzimas hepáticas

La alanina aminotransferasa (ALT) y la aspartato aminotransferasa (AST) proporcionan información sobre el daño al hepatocito. Los pacientes con enfermedad hepática avanzada presentan niveles reducidos de ALT [18], asociados a una elevación de AST y de la ratio AST/ALT [19]. Además, hasta el 80 % de los pacientes con MASLD presentan concentraciones normales de aminotransferasa, por lo que este parámetro no se considera fiable como factor predictivo de enfermedad hepática avanzada [20]. Existe evidencia de que los pacientes con alteraciones en el metabolismo de la glucosa y resistencia a la insulina y con niveles normales de ALT, podrían desarrollar MASLD. Del mismo modo, los niveles normales de aminotransferasas no deben excluir la realización de estudios complementarios, como pruebas de imagen o una biopsia hepática [21]. La ratio AST/ALT se ha utilizado tradicionalmente para determinar el riesgo de cirrosis en pacientes con hepatitis vírica crónica [22, 23], esteatothepatitis no alcohólica (NASH), enfermedad hepática alcohólica (ALD) [24, 25] y cirrosis biliar primaria (CBP) [26]. Sin embargo, actualmente, las diferentes fases de la fibrosis no se pueden identificar meramente con el uso de este cociente, ya que no distingue entre fibrosis moderada y grave [27, 28].

Índice APRI

En el pasado, se solía calcular el la ratio AST/plaquetas (índice APRI) [25], [26], [27], [28], [29] para evaluar si los pacientes con VHC presentaban fibrosis hepática o no, así como para diferenciar las distintas fases de fibrosis hepática de la cirrosis [30, 31]. Recientemente, se ha propuesto un índice APRI modificado (m-APRI), que incorpora la edad y los niveles de albúmina sérica a la fórmula APRI (Tabla 1) [32]. Se ha demostrado que este m-APRI mejora la predicción de fibrosis avanzada y cirrosis en la hepatitis vírica [33].

Scores utilizados en la evaluación y estadificación de la fibrosis hepática.

| Score/índice | Fórmula |

|---|---|

| APRI | AST (UI/L)/valor AST en el límite superior de normalidad (UI/L)/recuento de plaquetas (109/L)×100 |

| m-APRI | (Edad (años)×(AST (UI/L)/valor AST en el límite superior de normalidad(UI/L))/ (Albúmina × recuento de plaquetas(109/L))×100 |

| BARD score | AST/ALT>0,8 2 puntos |

| IMC>28 1 punto | |

| Diagnóstico de diabetes 1 punto | |

| Índice forns | 7,811−(3,131×ln(recuento de plaquetas(109/L)))+(0,781×In(GGT (UI/L)))+(3,467×ln(Edad (años)))−(0,014×(colesterol (mg/dL))) |

| FIB-4 | AST (UI/L)×Edad (años)/(recuento de plaquetas(109/L)×√(ALT (UI/L)) |

| NFS | −1,675+(0,037×Edad (años))+(0,094×IMC (kg/m2))+(1,13×GAA/diabetes (sí=1, no=2))+(0,99×ratio AST/ALT)−(0,013×plaquetas (109/L))−(0,66×albúmina (g/dL)) |

| FibroTest | (4,467×log (α2-MG))−(1,357×log (haptoglobina))+(1,017×log (GGT))+(00,281×Edad (años))+(1,737×log (bilirrubina total))−(1,184×apoA1)+(0,301×sexo (masculino=1, femenino=0))−5,540 |

| Fibrometer NAFLD | (04,184×glucosa (mmol/L))+(00,701×AST (UI/L))+(00,008×ferritina (μg/L))−(00,102×plaquetas (109/L))−(00,260×ALT (UI/L))+(00,459×peso corporal (kg)+00,842 Edad (años))+11,6226 |

| Hepascore | Y/(1+Y) |

| Donde Y=exp (−4,185818−(00,249×Edad)+(0,7464×sexo)+(10,039×α2-MG)+(00,302×HA)+(00,691×bilirrubina total)−(00,012×GGT)) | |

| HFS | 1/(1+e[5,390−0,986×Edad [45–64 años]−1,719×Edad [≥65 años]+0,875×Sexo masculino−0,896×AST [35–69 UI/L]−2,126×AST [≥70 UI/L]−0,027×Albúmina [4–4,49 g/dL]−0,897×Albúmina [<4 g/dL]−0,899×HOMA−R [2−3,99 sin Diabetes Mellitus]−1,497×HOMA−R [≥4 sin Diabetes Mellitus]−2,184×Diabetes Mellitus−0,882×plaquetas×1,000/μL [155−219]−2,233×plaquetas×1,000/μL [<155]), |

| Índice Benlloch | 1/1+e−12,698+(0,097×(ratio Albúmina/proteínas totales))−(1,356×(tiempo de protrombina))−(0,004×(AST))−(0,02×(tiempo desde trasplante hepático)) |

| ADAPT score | exp (log10 ((Edad×PRO-C3)/√Recuento de plaquetas)+diabetes (0=ausente; 1=presente) |

| ELF | 2,494+0,846 ln(HA)+0,735 ln(PIIINP)+0,391 ln(TIMP-1) |

| Modelo CHI3L1 | 0,032×AST−0,012×plaquetas+0,012×HA+0,846×log10 (CHI3L1)−4,752 |

| M2BPGi COI | ([M2BPGi]muestra−[M2BPGi]control negativo)/([M2BPGi]control positivo−[M2BPGi]control negativo) |

-

α2-MG, alfa 2 macroglobulina; ALT, alanina aminotransferasa; ApoA1, apolipoproteína A1; APRI, índice de relación AST/plaquetas; AST, aspartato aminotransferasa, IMC, índice de masa corporal; CHI3L1, proteína 1 similar a quitinasa 3; ELF, enhanced liver fibrosis; GGT, gamma-glutamiltranspeptidasa; AH, ácido hialurónico; HFS, score de fibrosis de Hepamet; HOMA-R, evaluación del modelo homeostático de resistencia a la insulina; m-APRI, APRI modificado; M2BPGi, isómero de glicosilación de la proteína de unión a Mac-2; M2BPGi COI, índice de corte del isómero de glicosilación de la proteína de unión Mac-2; NFS, score de fibrosis hepática de la enfermedad del hígado graso no alcohólico; GAA, glucosa alterada en ayunas; PIIINP, propéptido del procolágeno tipo III; TIMP-1, inhibidor de metaloproteinasas de matriz tipo 1.

BARD score

Este score fue propuesto por Harrison y col. e incluye la presencia de diabetes mellitus tipo 2, el índice de masa corporal (IMC) del paciente y la actividad de las enzimas hepáticas en suero, determinada a través de la relación AST/ALT [34]. En los pacientes con MASLD, BARD tiene un valor predictivo negativo (VPM) elevado del 96 % [34]. Recientemente, Park y col. [35], han descrito en pacientes con MASLD la asociación entre fibrosis hepática avanzada, evaluada mediante la puntuación BARD, y un mayor riesgo de enfermedad cardiovascular y mortalidad, sugiriendo su relación con la inflamación miocárdica y el ictus isquémico.

Forns index

El índice de Forns es un sistema de puntuación que combina la edad, la gamma-glutamil transferasa (GGT), el colesterol y el recuento de plaquetas, cuya utilidad ha sido demostrada en la identificación de pacientes con hepatitis C crónica sin fibrosis hepática moderada [36]. Así mismo, el índice Forns ha sido validado en pacientes con MASLD confirmada mediante biopsia, en poblaciones de pacientes con enfermedad hepática crónica sin cirrosis descompensada o carcinoma hepatocelular [37]. Romero y col [38], obtuvieron una precisión del 95,2 % con el índice Forns a la hora de predecir fibrosis moderada, y del 91,7 % en la detección de fibrosis avanzada en pacientes con el genotipo 1 de hepatitis C crónica (CHC). De este modo, existe evidencia de que el índice Forns es un factor predictivo de morbilidades y mortalidad en pacientes con MASDL, similar a APRI [39].

FIB-4

FIB-4 es un índice basado en la edad, la actividad de AST y ALT en suero y la concentración de plaquetas (Tabla 1). Este es probablemente el índice sérico más ampliamente utilizado en el cribado inicial de la fibrosis hepática, estando recomendado su uso en las guías de práctica clínica para la MASLD, como la Guía de Práctica sobre la evaluación clínica y manejo de la enfermedad de hígado graso no alcoholico de la American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) [1, 40]. El punto de corte más aceptado para FIB-4 para detectar fibrosis avanzada es 2,67 [41], aunque algunos estudios lo incrementan hasta 3,25 [42] (Tabla 2). Itakura y col [43] establecieron la tasa de precisión del FIB-4 en 71 % para el diagnóstico de cirrosis por infección por el VHB, y 75 % en pacientes con infección por el VHC. Aunque en diversos meta-análisis también se ha concluido que FIB-4, así como APRI, fueron moderadamente efectivos para la evaluación de la fase de fibrosis en la hepatitis B crónica [44], [45], [46], FIB-4 mostró mayor precisión diagnóstica que APRI, a la hora de predecir fibrosis moderada o avanzada o un diagnóstico de cirrosis [46]. Tal como demuestran distintos estudios, FIB-4 posee un elevado valor diagnóstico a la hora de evaluar la cirrosis y la fibrosis moderada o grave [47], [48], [49], [50], [51], [52], [53], [54]. FIB-4 es una herramienta útil en el cribado de la fibrosis hepática, debido a su viabilidad y elevado VPN [55]. Así mismo, se ha propuesto un punto de corte de 1,3 para descartar la fibrosis hepática avanzada [56]. Por otro lado, su especifidad para la fibrosis avanzada es menor en pacientes ≥65 años, derivando en una mayor tasa de falsos positivos, por lo que el punto de corte para el FIB-4 en este grupo de edad se ha elevado a 2 [57]. Aunque la utilidad de este biomarcador para descartar fibrosis hepática avanzada en pacientes con patologías de gran prevalencia, como la diabetes o la MASLD no se puede descartar únicamente en función del FIB-4. De este modo, en caso de elevada sospecha, se recomienda la evaluación o empleo de otros métodos más específicos [58, 59].

Puntos de corte de los biomarcadores séricos de fibrosis hepática establecidos en la literatura.

| Score/índice | Pacientes/cohorte | Diagnóstico | Predice/descarta | AUC | Punto de corte | Sensibilidad, % | Especifidad, % | VPP, % | VPN, % | Referencias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AST/ALT | MASLD | Fibrosis avanzada | Predice | 0,83 (0,74–0,91) | >0,8 | 74 | 78 | 44 | 93 | [60] |

| APRI | Pacientes con hepatitis vírica crónica | Fibrosis significativa | Predice | 0,72 (0,69–0,75) | >0,5 | 79,9 | 48,4 | 67,3 | 64,4 | [61] |

| MASLD | Fibrosis avanzada | Predice | 0,67 (0,54–0,8) | >1 | 27 | 89 | 37 | 84 | [60] | |

| Cirrosis | Predice | 0,77 (0,73–0,81) | >2 | 45,2 | 88,4 | 38,7 | 90,9 | [61] | ||

| mAPRI | MASLD | Fibrosis avanzada | Predice | 0,84 (0,78–0,89) | >5,84 | 77,8 | 79,8 | 75,7 | 81,6 | [32] |

| Cirrosis | Predice | 0,83 (0,74–0,87) | >9 | 67,3 | 85,7 | 67,3 | 85,7 | [32] | ||

| BARD | MASLD | Fibrosis avanzada | Predice | 0,77 (0,68–0,87) | >2 | 89 | 44 | 27 | 95 | [60] |

| Índice de forns | ALD | Fibrosis avanzada | Predice | 0,83 (0,78–0,89) | >6,9 | 67 | 89 | 55 | 93 | [62] |

| FIB-4 | MASLD (edad<65) | Fibrosis avanzada | Descarta | 0,86 (0,78–0,94) | ≤1,3 | 85 | 65 | 36 | 95 | [42, 60] |

| Predice | >3,25 | 26 | 98 | 75 | 85 | [60] | ||||

| MASLD (edad>65) | Fibrosis avanzada | Predice | NI | >2 | 77 | 70 | 12 | 98 | [57] | |

| Pacientes con coinfección de VIH/VHC | Fibrosis avanzada | Descarta | 0,737 | <1,45 | 66,7 | 71,2 | 38 | 89 | [47] | |

| Predice | >3,25 | 26 | 96,6 | 64,5 | 82,6 | [47] | ||||

| Fibrosis avanzada | Descarta | 0,802 (0,758–0,847) | <1,3 | 74 | 71 | 43 | 90 | [41] | ||

| Predice | >2,67 | 33 | 98 | 80 | 83 | [41] | ||||

| NSF | MASLD | Fibrosis avanzada | Descarta | 0,81 (0,71–0,91) | <-1,455 | 78 | 58 | 30 | 92 | [60] |

| Predice | >0,676 | 33 | 98 | 79 | 86 | [60] | ||||

| Fibrosis avanzada | Descarta | 0,84 (0,81–0,88) | <-1,455 | 77 | 71 | 52 | 88 | [63] | ||

| Predice | >0,676 | 43 | 96 | 82 | 80 | [63] | ||||

| Fibrotest | Pacientes con hepatitis vírica crónica | Fibrosis significativa | Predice | 0,78 (0,75–0,81) | >0,48 | 67,4 | 75,3 | 78,7 | 63,1 | [61] |

| Pacientes con hepatitis vírica crónica | Cirrosis | Predice | 0,82 (0,79–0,85) | >0,74 | 62,6 | 84,4 | 40,1 | 93,1 | [61] | |

| Gp73 | Pacientes con VHB crónica | Significant liver inflammation | Predice | 0,806 (0,748–0,856) | >85,7 ng/mL | 43,59 | 97,18 | 89,5 | 75,8 | [64] |

| Pacientes con VHB crónica | Fibrosis significativa | Predice | 0,742 (0,679–0,799) | >84,49 ng/mL | 30,70 | 96,23 | 89,74 | 56,35 | [64] | |

| HFS | MASLD | Fibrosis avanzada | Descarta | NI | <0,12 | 74,6 | 75,5 | 49,8 | 90,1 | [65] |

| Predice | NI | ≥0,47 | 34,6 | 96,7 | 77,2 | 81,9 | [65] | |||

| Índice DE Benlloch | Pacientes trasplantados con VHC crónica | Fibrosis significativa | Descarta | 0,84 | ≤0,2 | 87 | 71 | 49 | 95 | [66] |

| Fibrosis significativa | Predice | 0,84 | ≥0,8 | 17 | 99 | 80 | 79 | [66] | ||

| HA | Patologías hepáticas crónicas | Fibrosis avanzada | Predice | NI | >90 μg/L | 80,4 | 70,2 | 86,7 | 59,8 | [67] |

| Patologías hepáticas crónicas | Cirrosis | Predice | NI | >210 μg/L | 96,2 | 85,3 | 65,4 | 98,8 | [67] | |

| PCIIINP | Patologías hepáticas crónicas | Fibrosis avanzada | Predice | NI | >90 μg/L | 82 | 60,8 | 83,5 | 58,4 | [67] |

| Patologías hepáticas crónicas | Cirrosis | Predice | NI | >150 μg/L | 76,4 | 68,7 | 40,4 | 91,3 | [67] | |

| CIV | Patologías hepáticas crónicas | Fibrosis avanzada | Predice | NI | >75 μg/L | 63,1 | 83,8 | 90,4 | 48,4 | [67] |

| Patologías hepáticas crónicas | Cirrosis | Predice | NI | >90 μg/L | 80 | 75,8 | 47,8 | 93,2 | [67] | |

| PRO-c3 | ALD | Fibrosis avanzada | Predice | 0,85 (0,79–0,90) | >15,6 | 81 | 73 | 38 | 95 | [62] |

| Pacientes con VHC crónica | Fibrosis avanzada | Predice | 0,72 (0,65–0,78) | >20,2 | 71,4 | 71,9 | NI | NI | [68] | |

| ADAPT score | ALD | Fibrosis avanzada | Predice | 0,88 (0,83–0,93) | >6,328 | 86 | 78 | 44 | 97 | [62] |

| MASLD | Fibrosis avanzada | Predice | 0,86 (0,79–0,91) | >6,328 | NI | NI | 48,4 | 96,6 | [69] | |

| CHI3L1 o YKL-40 | MASLD | Fibrosis avanzada | Predice | 0,764 | >165 μg/L | 70 | 76,8 | NI | NI | [70] |

| ALD | Fibrosis avanzada | Predice | NI | >330 μg/L | 88,5 | 50,8 | NI | NI | [71] | |

| VHB | Fibrosis avanzada | Predice | 0,97 | >68,75 μg/L | 95,2 | 89,7 | NI | NI | [72] | |

| VHC | Fibrosis avanzada | Predice | 0,809 | >186,4 μg/L | 78 | 81 | NI | NI | [73] | |

| M2BPGi COI | VHB | Fibrosis significativa | Predice | 0,653 (0,608–0,698) | >0,25 | 74,8 | 47,3 | NI | NI | [74] |

| VHB | Fibrosis avanzada | Predice | 0,59 (0,50–0,67) | ≥3,0 | 18,8 | 98,5 | NI | NI | [75] | |

| Predice | 0,795 (0,743–0,848) | >0,45 | 69,6 | 74,1 | NI | NI | [74] | |||

| VHB | Cirrosis | Predice | 0,914 (0,815–1) | >0,96 | 83,3 | 92,7 | NI | NI | [74] | |

| ELF | Patologías hepáticas crónicas | Severe fibrosis | Predice | 0,86 (0,83 - 0,89) | ≥10,48 | 62 | 89 | 73 | 83 | [76] |

| Fibrosis hepática (cohorte EUROGOLF) | Fibrosis leve | Predice | NI | >7,7 | 85 | 38 | NI | NI | [77] | |

| Fibrosis hepática (cohorte EUROGOLF) | Fibrosis avanzada | Predice | NI | >9,8 | 65 | 90 | NI | NI | [77] | |

| Fibrosis hepática (cohorte EUROGOLF) | Cirrosis | Predice | NI | ≥11,3 | 38 | 97 | NI | NI | [77] | |

| VHB | Advance fibrosis | Predice | NI | >9,8 | 62 | 66 | 55 | 72 | [78] | |

| Hepascore | VHC | Fibrosis significativa | Predice | 0,81 | ≥0,55 | 82 | 65 | 70 | 78 | [79] |

| Pacientes con hepatitis vírica crónica | Fibrosis significativa | Predice | 0,78 (0,75–0,80) | >0,5 | 52,9 | 86,3 | 83,7 | 57,9 | [61] | |

| VHC | Fibrosis significativa | Predice | 0,852 (0,778–0,926 | >0,5 | 67 | 92 | NI | NI | [80] | |

| VHC | Fibrosis avanzada | Predice | 0,957 (0,918–0,995) | >0,5 | 95 | 81 | NI | NI | [80] | |

| VHC | Cirrosis | Predice | 0,938 (0,872–1,000 | >0,84 | 71 | 89 | NI | NI | [80] | |

| Pacientes con hepatitis vírica crónica | Cirrosis | Predice | 0,86 (0,83–0,88) | >0,84 | 59 | 87,4 | 43,2 | 92,9 | [61] | |

| Fibrometers | Pacientes con hepatitis vírica crónica | Fibrosis significativa | Predice | 0,79 (0,76–0,81) | >0,411 | 83,1 | 57,1 | 72 | 71,8 | [61] |

| Pacientes con hepatitis vírica crónica | Cirrosis | Predice | 0,86 (0,83–0,89) | >0,442 | 43,9 | 95 | 58,1 | 91,5 | [61] |

-

ALT, alanina aminotransferasa; APRI, índice de relación AST/plaquetas; AST, aspartato aminotransferasa; AUC, área bajo la curva; CHI3L1, proteína 1 similar a quitinasa 3; ELF, Enhanced Liver Fibrosis; Gp73, proteína 73 de Golgi; HA, ácido hialurónico; HFS, score de fibrosis Hepamet; VHB, virus de la hepatitis B; VHC, virus de la hepatitis C; M2BPGi COI, punto de corte del isómero de glicosilación de la proteína de unión Mac-2; NAFLD, enfermedad del hígado graso no alcohólico; NFS, score de fibrosis NAFLD; VPN, valor predictivo negativo; NI, no informado; OELF, ELF original; PIIINP, propéptido N-terminal de procoledadn tipo III; VPP, valor predictivo positivo.

NAFLD score de fibrosis

NAFLD score considera los mismos parámetros que el FIB-4, añadiendo el IMC, la presencia o no de diabetes y la albúmina (Tabla 1). Su uso viene recomendado para el diagnóstico de fibrosis hepática avanzada, en la guía de práctica clínica de la EASL-EASD-EASO [81] para el manejo de MASLD, ya que este score tiene un área bajo la curva (AUROC) >0,8, similar al del FIB-4 (Tabla 2) [60, 63]. Sin embargo, a pesar de su viabilidad, aún se considera que, tanto FIB-4 como NFS, son herramientas subóptimas, ya que presentan una proporción considerable de falsos positivos y falsos negativos cuando se aplican a la población general, por lo que únicamente deberían ser empleados en las poblaciones de riesgo [82].

Fibrotest

FibroTest™ (Biopredictive Paris) consiste en un panel de marcadores, entre los que se encuentran la α2-macroglobulina sérica, apolipoproteína A1, haptoglobina, bilirrubina total y GGT, ajustadas por edad y sexo [83] (Tabla 1). Fibrotest ha sido validado para la estadificación de la fibrosis hepática en enfermedades hepáticas comunes, como la hepatitis B crónica [84], la enfermedad hepática alcohólica [85], y la MASLD [83]. En un metaanálisis reciente [86], se concluyó que Fibrotest tiene un rendimiento aceptable en la detección de cirrosis (AUC 0,92) en los pacientes con MASLD. Sin embargo, ha mostrado una precisión limitada a la hora de predecir fibrosis moderada y avanzada (AUROC=0,77 para las dos patologías). Degos y col. obtuvieron resultados similares en pacientes con hepatitis vírica crónica [61] (Tabla 2). No obstante, Fibrotest presenta buenos valores predictivos para el diagnóstico de fibrosis hepática en pacientes con MASLD, por lo que se incluye en las guías de práctica clínica de la EASL-EASD-EASO [81], así como para la supervivencia sin mortalidad relacionada con enfermedad hepática, mortalidad relacionada con patologías cardíacas y supervivencia global [87].

Proteína de Golgi 73 (Gp73)

GP73 es una proteína transmembrana liberada por células dañadas, cuyos niveles séricos se encuentran elevados en los pacientes con patologías hepáticas crónicas [88–90]. Se sabe que GP73 está sobreexpresada en pacientes con cirrosis hepática [90], poseyendo un elevado valor diagnóstico en la cirrosis hepática [91, 92]. Recientemente, en pacientes con cirrosis compensada, se ha observado una relación entre niveles elevados de GP73 y peores resultados clínicos, como la descompensación, el desarrollo de hepatocarcinoma, y mortalidad relacionada con patología hepática [93, 94]. Su uso también ha sido validado en pacientes con MASLD [95], ALD y hepatitis vírica [64, 88, 96], lo que demuestra su utilidad para el diagnóstico de fibrosis y cirrosis avanzada, presentando un valor diagnóstico mayor que los índices FIB-4 y APRI [97].

Score de fibrosis Hepamet (HFS)

HFS es un nuevo score recientemente propuesto, validado en una población europea multicéntrica caucásica con MASLD confirmada mediante biopsia, que incluye la edad, el sexo, la diabetes, el modelo homeostático para evaluar la resistencia a la insulina (HOMA-IR), AST, albúmina, y las plaquetas [65]. Según el equipo que lo desarrolló, HFS identifica a los pacientes con fibrosis avanzada con mayor precisión que los índices FIB-4 y NFS. Aunque se trata de un nuevo score, diversos estudios han validado sus puntos de corte [98–100] y verificado que HFS es el que muestra mayor precisión diagnóstica y mayor valor predictivo negativo, si se compara con los índices NFS y FIB-4 en pacientes con esteatosis hepática metabólica [101]. Además, HFS es tan fiable como NFS y FIB-4 en la predicción de cirrosis, eventos hepáticos a largo plazo, hepatocarcinoma y mortalidad global, con un mayor rendimiento en la predicción de fibrosis moderada y grave. Esto puede explicarse por la inclusión de la presencia de diabetes en su fórmula o el HOMA-IR en los pacientes no diabéticos [102]. Por otro lado, niveles elevados de HFS (punto de corte 0,12) están relacionados con un mayor riesgo de desarrollar diabetes mellitus 2 e hipertensión arterial en pacientes con MASLD, eventos que ni NFS ni FIB-4 pudieron predecir [103].

OWLiver

La prueba metabolómica patentada OWLiver® (One Way Liver S.L., Bilbao, España) es un análisis de sangre en ayunas que se emplea para determinar el grado de desarrollo de MASLD, mediante la medición de un panel de biomarcadores séricos de triacilgliceroles combinado con el IMC, que representan la grasa e inflamación en el hígado [104]. Los triacilgliceroles se miden mediante cromatografía líquida de alta resolución combinada con espectrometría de masas (UHPLC-MS), considerando posteriormente todos los resultados en un algoritmo, del que se obtiene una puntuación final OWLiver® [105] Owliver distingue entre un hígado normal y fibrosis hepática MASLD, con un AUROC de 0,90 y una elevada sensibilidad, lo que implica una reducida tasa de falsos negativos [106]. Este score también distingue la esteatosis simple de la esteatohepatitis, tal como se muestra en el estudio de validación prospectivo, en el que se había diagnosticado previamente a los pacientes mediante biopsia hepática [104]. Según Bril y col [107], comparadas con la biopsia hepática, las pruebas OWLiver® Care y OWLiver® mostraron un rendimiento subóptimo en pacientes con diabetes mellitus tipo 2. La falta de estudios comparativos entre OWLiver® y otros scores de fibrosis hepática no invasivos, sumado a la complejidad de la metodología, dificultan su implementación en la práctica clínica.

Índice de Benlloch

El índice Benlloch es un modelo creado para evaluar a los pacientes con VHC crónico sometidos a trasplante hepático. El propósito del índice Benlloch es evaluar si es necesario o no iniciar una terapia antiviral, así como realizar un seguimiento estrecho de este grupo de pacientes, con el fin de determinar si está indicado un retrasplante [66]. Este índice se basa en cuatro biomarcadores indirectos, entre los que se incluyen AST, tiempo de protrombina, relación albúmina/proteína total, y tiempo transcurrido desde el trasplante hepático (Tabla 1). Se ha demostrado su eficacia con respecto a la biopsia hepática en pacientes con HVC crónica sometidos a trasplante hepático, habiendo mostrado un poder de discriminación aceptable a la hora de distinguir la fibrosis significativa de la avanzada [66].

Biomarcadores directos

Proteínas de la matriz extracelular

Ácido hialurónico

El ácido hialurónico (AH) es un componente esencial de la matriz extracelular, con una elevada presencia en el hígado [108]. El AH es secretado por diversos tipos de células. Las células del revestimiento sinovial y las CEH son las responsables de su síntesis en el hígado, mientras que las células endoteliales sinusoidales participan en su degradación [109]. Las concentraciones séricas de AH se encuentran elevadas en las enfermedades hepáticas asociadas a la fibrosis, como ALD [109, 110], MASLD [111–113], VHC [114–116], VHB [108, 117], y coinfección de VIH-VHC [118, 119]. De este modo, se puede emplear como biomarcador no invasivo para evaluar la presencia de fibrosis hepática y realizar un seguimiento de la progresión de la enfermedad [109, 120].

Propéptido N-terminal del procolágeno tipo III

En un estudio reciente se ha identificado al propéptido N-terminal del procolágeno tipo III (PCIIINP), uno de los principales componentes del tejido conectivo, como un buen marcador de fibrosis hepática en pacientes con diabetes tipo 2 [121]. Los niveles séricos de PCIIINP se encuentran elevados en los pacientes con ALD o VHC y está correlacionado con el estadio de fibrosis hepática [122–124]. Así mismo, existe evidencia de que los niveles plasmáticos de PCIIINP son superiores a los índices APRI o FIB-4 como marcadores no invasivos para la estadificación de la fibrosis hepática en niños y adolescentes con MASLD confirmada mediante biopsia [125].

Laminina y colágeno tipo IV

El colágeno tipo IV (CIV) y la laminina (LN) han sido ampliamente estudiados en pacientes con ALD, hepatitis viral y MASLD [111, 126]. Del mismo modo, los niveles séricos de CIV y LN están correlacionados con la fase fibrótica de la infección por VHC y algunos estudios los identifican como biomarcadores no invasivo precisos de fibrosis hepática e inflamación hepática [127]. Por otro lado, la LN posee un menor valor diagnóstico que el AH y el CIV [128].

Algunos autores proponen emplear conjuntamente el AH, PCIIINP y CIV como biomarcadores para un diagnóstico más preciso de fibrosis hepática en diferentes patologías hepáticas crónicas [67]. Por otro lado, Stefano y col observaron que CIV puede predecir la presencia de fibrosis moderada y avanzada en pacientes con MASLD, al haber mostrado mejor AUROC que LN, AH y PCIIINP [129].

Sitio de escisión de la N-proteasadel PIIINP

El sitio de escisión de la N-proteasadel PIIINP (PRO-C3) es un marcador sistémico de la formación de colágeno III y de actividad fibroblástica. Así, está directamente relacionado con el desarrollo de fibrosis hepática. Se ha demostrado que este marcador detecta la fibrosis hepática, el índice de progresión y la respuesta a tratamiento en pacientes con enfermedad hepática crónica [68, 130–132]. Inicialmente, se confirmó que PRO-C3 distingue la fibrosis moderada de la severa en pacientes con CHC, e identifica a los pacientes con CHC con progresión de fibrosis con mayor precisión que la prueba habitual, FibroTest [68]. Así mismo, se ha observado que, en la población con ALD y MASLD, la utilidad de PRO-C3 aumenta cuando se emplea un algoritmo llamado ADAPT score, que incluye en su fórmula la edad, la presencia de diabetes y el recuento de plaquetas (Tabla 1) [62, 69]. ADAPT score es superior a APRI, FIB-4 y NFS, presentando además la ventaja de poder estratificar la fibrosis y la cirrosis, al contrario que otros biomarcadores no invasivos, que solo proporcionan resultados dicotómicos [69].

Metaloproteinasas de la matriz (MMP) e inhibidor tisular de metaloproteinasas (TIMP)

TIMP-1 era la única metaloproteinasa que se podría considerar como un factor predictivo independiente de fibrosis histológica, tal como se demostró en un estudio en pacientes con MASLD [133]. Sin embargo, Livzan y col. señalan a TIMP-2 como un posible marcador no invasivo para el diagnóstico de fibrosis hepática en pacientes con MASLD, al haber mostrado una buena correlación con la gravedad de la fibrosis [134]. Boeker y col. observaron que MMP-2 también se puede emplear para detectar la cirrosis con gran eficacia en pacientes con VHC crónica, con mayor valor diagnóstico que el AH o TIMP-1 [135]. Además, se ha propuesto la relación MMP-2/TIMP-1 como un indicador de respuesta a tratamiento con inferón-γ en pacientes con CHC, habiendo sido descrita una mayor reducción de dicha relación en los pacientes con buena respuesta, frente a los que no respondieron o no recibieron tratamiento [136]. Munsterman y col. describieron mayores niveles de TIMP-1 y TIMP-2 en pacientes con fibrosis grave que en aquellos con fibrosis leve o la ausencia de fibrosis en pacientes con MASLD. Así mismo, los autores observaron que MMP-9 era el único componente de MEC que se correlacionaba con la gravedad de la inflamación [137]. Recientemente, se ha identificado a MMP-7 como un marcador independiente de fibrosis hepática, capaz de mejorar el valor diagnóstico en pacientes con MASLD de edad avanzada, si se combina con la prueba mejorada de fibrosis hepática (Enhanced Liver fibrosis, ELF) [138].

Proteína 1 similar a la quitinasa 3 (CHI3L1)

CHI3L1, también llamada YKL-40, es una proteína secretada por los macrófagos, neutrófilos, células musculares lisas vasculares, y células tumorales, entre otras, aunque su expresión en el hígado es mayor que en otros tejidos. CHI3L1 realiza diversas funciones, como promover la degradación de la matriz extracelular y la remodelación de los tejidos [139]. Los niveles de CHI3L1 se han relacionado con el grado de fibrosis hepática en pacientes con MASLD [70], ALD [71], VHB [72], y VHC [73]. Huang y col. demostraron que CHI3L1 es un buen marcador a la hora de identificar fibrosis sustancial (AUC=0,94) y fibrosis avanzada (AUC=0,96). Así mismo, determinaron que CHI3L1 es superior al AH, PCIIINP, LN, y CIV para dicho propósito [140]. Saitou y col [73] observaron que los niveles séricos de CHI3L1 son superiores a otros marcadores no invasivos de fibrosis, como CIV, AH, y PCIIINP, a la hora de distinguir la fibrosis avanzada de la fibrosis leve, con un AUC de 0,809, en pacientes con infección de VHC. Así mismo, los autores observaron que dichos niveles se reducían tras la terapia. Se ha propuesto un modelo de CHI3L1, habiéndose demostrado que es superior a los índices APRI y FIB-4, en la predicción de la fibrosis moderada, en pacientes con VHB con niveles de ALT dos veces por debajo del límite superior del rango de normalidad [141].

Isómero de glicosilación de proteínas de unión a Mac‐2 (M2BPGi)

M2BPGi es una glicoproteína producida por las CHE, que funciona como mensajera entre las CEH y las células de Kupffer, promoviendo la fibrogénesis [142]. Así, se ha recomendado su uso, al ser un biomarcador preciso para la estadificación de la fibrosis hepática [143, 144]. Los niveles de M2BPGi se expresan en la literatura como un punto de corte, y su utilidad en la fibrosis hepática se ha validado en diversos estudios en pacientes con diferentes patologías, como VHC [145], VHB [75, 146] (Tabla 2), hepatitis autoinmune [147], NASH [148], MASLD [111, 149], atresia biliar [150], cirrosis biliar primaria [151], colangitis esclerosante primaria [152] y mortalidad en la cirrosis hepática [153]. En un estudio en pacientes con VHB, M2PBGi mostró correlación con el grado de fibrosis (F0–F4) y fue superior al recuento de plaquetas, AH, PCIIINP, TIMP-1, FIB-4, APRI, y ELF score, a la hora de establecer el grado de fibrosis moderada [154]. Se obtuvieron resultados similares al comparar la relación AST/ALT, APRI, y FIB-4 en la detección de fibrosis hepática avanzada [74]. Además, estudios recientes describen M2BPGi como biomarcador para el seguimiento de los pacientes con fibrosis hepática [155–159]. A los pacientes con niveles elevados de M2BPGi tras tratamiento antiviral se les debe realizar un seguimiento estrecho para detectar el posible desarrollo de hepatocarcinoma [155, 160]. Además, en un estudio en pacientes con VHC, M2BPGi fue superior a FIB-4, a la hora de distinguir los diferentes grados de fibrosis tras tratamiento con antivirales de acción directa [161].

Aunque la utilidad de estos biomarcadores directos está demostrada, su sensibilidad y especifidad aumentan cuando se usan conjuntamente [124], superando las de los algoritmos o scores como ELF, Hepascore o Fibrometer, descritos a continuación.

Fórmulas O índices calculados empleando proteínas de la matriz extracelular

Enhanced liver fibrosis (ELF)

ELF es una prueba de sangre patentada (Siemens Healthineers, Erlagen, Alemania) que mide tres moléculas implicadas en el metabolismo de la matriz hepática (TIMP-1, PIIINP y AH), proporcionando un score que refleja la gravedad de la fibrosis hepática. Desde su aparición como el ELF original (OELF), el algoritmo se ha visto sometido a diversas modificaciones, como la eliminación del parámetro de la edad, habiéndose establecido diferentes puntos de corte [162, 163]. ELF ha mostrado una buena precisión en la predicción de la fibrosis hepática [77, 164], habiendo sido validado en diferentes patologías hepáticas crónicas como ALD [165], MASLD [166], cirrosis biliar primaria [167] e infección de hepatitis vírica [78, 168, 169]. Esta prueba es capaz de distinguir entre fibrosis grave, moderada y ausencia de fibrosis, con un AUC de 0,90, 0,82, y 0,76 respectivamente [170] (Tabla 2). Además, al igual que APRI y FIB-4, existe evidencia de la utilidad de ELF en la identificación temprana de pacientes con riesgo elevado de recurrencia de hepatitis C tras el trasplante hepático [171]. En pacientes con patología hepática crónica, existe una posible relación entre niveles elevados de ELF y peores resultados clínicos, lo que sugiere un valor pronóstico [76]. La guía de práctica clínica para la evaluación clínica y manejo de la MASLD de la AASLD recomienda su uso como prueba específica de segunda línea, siendo comparable a FibroScan en la evaluación de la fibrosis hepática [1, 172]. Sin embargo, en la interpretación de los resultados, y con el fin de minimizar la variabilidad de la prueba, hay que tener en cuenta diversos factores de influencia, como el sexo, la edad y el momento en que se realiza la prueba sanguínea [173].

Hepascore

Hepascore fue inicialmente validado para predecir los diferentes grados de fibrosis en pacientes con VHC. Esta prueba combina variables sociodemográficas como la edad y el sexo, con parámetros sanguíneos, entre los que se incluyen la bilirrubina, la gamma-glutamil transferasa, el AH y la α2-macroglobulina [80] (Tabla 1). Actualmente, es un algoritmo ampliamente utilizado para la detección de fibrosis moderada en multitud de patologías hepáticas crónicas [79, 174, 175]. Huang y col. [174] demostraron que Hepascore tiene mayor valor diagnóstico en la fibrosis moderada y avanzada en pacientes con CHC, CHB y ALD, que en aquellos con MASLD y coinfección de VIH y hepatitis vírica. Así mismo, se ha comparado con otros scores, mostrando valores diagnósticos considerablemente mayores en los pacientes con ALD que APRI y FIB-4, aunque similares a los de FibroTest y Fibrometer [85]. Por otro lado, en un grupo aleatorizado de pacientes alcohólicos, Chrostek y col. [176] concluyeron que Hepascore posee un valor diagnóstico inferior al de APRI, Forns y FIB-4, al emplear Fibrotest como matriz para comparar sus valores diagnósticos. Sin embargo, en pacientes con MASLD, Hepascore es capaz de identificar la fibrosis hepática avanzada [177]. Hepascore también ha demostrado capacidad para predecir con exactitud los riesgos a largo plazo de eventos como descompensación y hepatocarcinoma, siendo ambos causa de mortalidad relacionada con enfermedad hepática en pacientes con disfunción metabólica asociada a MASLD [178]. Sin embargo, se observan una variación interindividual biológica en los niveles de AH en sangre extraídasin ayunas, tanto en sujetos sanos como en pacientes con patologías hepáticas, por lo que el sistema Hepascore se debería emplear con cautela en las determinaciones puntuales o en el seguimiento clínico [179].

FibroMeters

FibroMeters es una familia de paneles patentados formados por biomarcadores sanguíneos con diversas características, cuya flexibilidad permite adaptarlos a la causa de la enfermedad hepática crónica [180]. Estos incluyen biomarcadores directos como AH, α2-macroglobulina y biomarcadores indirectos como tiempo de protrombina, plaquetas, AST, ALT, GGT, bilirrubina, urea, ferritina, y otros datos como edad, peso corporal y sexo (Tabla 1). Los paneles de FibroMeters se desarrollaron y validaron inicialmente para establecer el grado de fibrosis en pacientes con CHB o hepatitis C crónica (CHC) [181] y MASLD [182]. Según Calès y col. [180], la prueba FibroMeter para la estadificación de la fibrosis en el CHC mostró un AUROC significativamente mayor que Fibrotest, Hepascore, APRI y FIB-4. En un metaanálisis en pacientes con CHC, FibroMeter demostró su superioridad con respecto a FibroTest y Hepascore en términos de valor diagnóstico global [183]. El FibroMeter estándar se amplió para mejorar su valor diagnóstico en la cirrosis, empleando coeficientes específicos con los mismos parámetros clínicos y sanguíneos que el FibroMeter estándar, resultando en un VPP del 100 % en los pacientes con VHC [184]. Además, en pacientes con MASLD, FibroMeter ha demostrado mayor precisión en el diagnóstico de la fibrosis moderada que APRI o NFS [185]. Los FibroMeter de segunda y tercera generación (V2G y V3G, respectivamente) fueron originariamente desarrollados para el diagnóstico de fibrosis moderada en pacientes con hepatitis C [186], aunque en los últimos años han sido validados también en pacientes con MASLD [182, 187]. La última versión es la elastografía de transición controlada mediante vibración (VCTE), que es una combinación de FibroMeter V3G y TE [188]. Es la prueba con la mayor precisión diagnóstica para la detección de fibrosis avanzada, frente a Fibrometer VG2 y Fibrometer MASLD [189], superando también a NFS y TE en el diagnóstico de fibrosis hepática grave en pacientes con MASLD [190]. Sin embargo, Guillaume y col. [187] obtuvieron la misma precisión para ELF y FibroMeterV2G en pacientes con MASLD. Además, FibroMeter VCTE posee una buena precisión diagnóstica, similar a la de TE, en la predicción de fibrosis grave en pacientes con hepatitis autoinmune, siendo incluso mejor en la colangitis biliar primaria, tal como observaron Zachou y col [191].

Conclusiones

El diagnóstico temprano de fibrosis hepática en sus fases iniciales es esencial para garantizar una intervención clínica precisa y prevenir la progresión de fibrosis hepática a cirrosis y carcinoma hepatocelular. Así mismo, es importante diagnosticarla lo antes posible, ya que la fibrosis hepática está asociada a una mayor mortalidad global a largo plazo, necesidad de trasplante hepático y eventos hepáticos [192]. Los biomarcadores séricos se postulan como una excelente opción, ya que permiten un seguimiento continuado y son menos invasivos que la biopsia hepática. Todas estas escalas no invasivas, incluyendo los biomarcadores séricos directos e indirectos, poseen mayor sensibilidad, pero peor especificidad, por lo que deberían ser utilizadas para descartar a los pacientes con MASLD sin fibrosis avanzada [81], evitando así la realización de biopsias hepáticas innecesarias. Por sí solas, estas escalas no resultan válidas para establecer un diagnóstico preciso. El empleo de estos biomarcadores séricos e índices indirectos como primer paso, o la combinación de biomarcadores séricos con índices de fibrosis específicos, como ELF, o combinados con FibroScan o TE, son estrategias fiables recomendadas en las guías de práctica clínica para la estadificación de la fibrosis hepática en pacientes con diferentes patologías [16], siendo además un proceso diagnóstico económico. Además, algunos de estos biomarcadores, como FIB-4 o NFS son herramientas sencillas y económicas cuya implementación podría influir considerablemente en la identificación de pacientes con fibrosis hepática en sus fases iniciales, momento en el cual se puede revertir dicha patología [193, 194]. Aunque la totalidad de estos biomarcadores no invasivos e índices han sido estudiados en población de riesgo, podrían utilizarse en el cribado de grupos de pacientes de atención primaria, como pacientes con diabetes mellitus tipo 2, patologías relacionadas con el abuso del alcohol, factores de riesgo metabólico, o elevación de enzimas hepáticas, ya que sigue existiendo una amplia prevalencia de las enfermedades hepáticas crónicas entre la población general [195]. Por esta razón, la American Diabetes Association (ADA) y la European Associations for the Study of Diabetes (EASD), of the Liver (EASL) and of Obesity (EASO) recomiendan realizar un cribado de fibrosis hepática en todos los pacientes con diabetes mellitus tipo 2 [196, 197]. De este modo, todos los laboratorios deberían evaluar y definir la mejor estrategia diagnóstica, en consenso con los clínicos, con el fin de alcanzar el mejor rendimiento diagnóstico en su población diana.

Agradecimientos

Se agradece a la Dra. María Romero por sus aportaciones al manuscrito.

-

Aprobación ética: No procede.

-

Consentimiento informado: No procede.

-

Contribución de los autores: Todos los autores han aceptado la responsabilidad de todo el contenido de este manuscrito y han aprobado su presentación.

-

Conflicto de interés: Los autores declaran no tener ningún conflicto de interés.

-

Financiación del proyecto: Ninguno declarado.

-

Disponibilidad de los datos: No procede.

-

Nota de artículo: El artículo original puede encontrarse aquí: https://doi.org/10.1515/almed-2023-0081.

Referencias

1. Rinella, ME, Neuschwander-Tetri, BA, Siddiqui, MS, Abdelmalek, MF, Caldwell, S, Barb, D, et al.. AASLD practice guidance on the clinical assessment and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2023;77:1797–1835. https://doi.org/10.1097/HEP.0000000000000323. 36727674.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

2. Hernandez-Gea, V, Friedman, SL. Pathogenesis of liver fibrosis. Annu Rev Pathol 2011;6:425–56. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130246.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Wiegand, J, Berg, T. The etiology, diagnosis and prevention of liver cirrhosis: part 1 of a series on liver cirrhosis. Dtsch Arzteblatt Int 2013;110:85–91. https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.2013.0085.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

4. Kisseleva, T. The origin of fibrogenic myofibroblasts in fibrotic liver. Hepatology 2017;65:1039–43. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.28948.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

5. Rockey, DC, Bell, PD, Hill, JA. Fibrosis – a common pathway to organ injury and failure. N Engl J Med 2015;373:96. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc1504848.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Ortiz, C, Schierwagen, R, Schaefer, L, Klein, S, Trepat, X, Trebicka, J. Extracellular matrix remodeling in chronic liver disease. Curr Tissue Microenviron Rep 2021;2:41–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43152-021-00030-3.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

7. Iredale, JP, Benyon, RC, Pickering, J, McCullen, M, Northrop, M, Pawley, S, et al.. Mechanisms of spontaneous resolution of rat liver fibrosis. Hepatic stellate cell apoptosis and reduced hepatic expression of metalloproteinase inhibitors. J Clin Invest 1998;102:538–49. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci1018.Suche in Google Scholar

8. Rodimova, S, Mozherov, A, Elagin, V, Karabut, M, Shchechkin, I, Kozlov, D, et al.. Effect of hepatic pathology on liver regeneration: the main metabolic mechanisms causing impaired hepatic regeneration. Int J Mol Sci 2023;24:9112. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24119112.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

9. Reeves, HL, Friedman, SL. Activation of hepatic stellate cells – a key issue in liver fibrosis. Front Biosci J Virtual Libr 2002;7:d808–26. https://doi.org/10.2741/a813.Suche in Google Scholar

10. Elpek, GÖ. Cellular and molecular mechanisms in the pathogenesis of liver fibrosis: an update. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:7260–76. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i23.7260.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

11. Zhou, W-C, Zhang, Q-B, Qiao, L. Pathogenesis of liver cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:7312–24. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i23.7312.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

12. Higashi, T, Friedman, SL, Hoshida, Y. Hepatic stellate cells as key target in liver fibrosis. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2017;121:27–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addr.2017.05.007.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

13. Duarte, S, Baber, J, Fujii, T, Coito, AJ. Matrix metalloproteinases in liver injury, repair and fibrosis. Matrix Biol 2015;44–46:147–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matbio.2015.01.004.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

14. Moreira, RK. Hepatic stellate cells and liver fibrosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2007;131:1728–34. https://doi.org/10.5858/2007-131-1728-hscalf.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Lee, JH, Joo, I, Kang, TW, Paik, YH, Sinn, DH, Ha, SY, et al.. Deep learning with ultrasonography: automated classification of liver fibrosis using a deep convolutional neural network. Eur Radiol 2020;30:1264–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-019-06407-1.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Castera, L, Friedrich-Rust, M, Loomba, R. Noninvasive assessment of liver disease in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology 2019;156:1264–81.e4. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2018.12.036.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

17. Chin, JL, Pavlides, M, Moolla, A, Ryan, JD. Non-invasive markers of liver fibrosis: adjuncts or alternatives to liver biopsy? Front Pharmacol 2016;7:159. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2016.00159.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

18. Sorrentino, P, Tarantino, G, Conca, P, Perrella, A, Terracciano, ML, Vecchione, R, et al.. Silent non-alcoholic fatty liver disease – a clinical-histological study. J Hepatol 2004;41:751–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2004.07.010.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

19. De Ritis, F, Coltorti, M, Giusti, G. An enzymic test for the diagnosis of viral hepatitis: the transaminase serum activities. Clin Chim Acta 1957;2:70–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/0009-8981(57)90027-x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Mofrad, P, Contos, MJ, Haque, M, Sargeant, C, Fisher, RA, Luketic, VA, et al.. Clinical and histologic spectrum of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease associated with normal ALT values. Hepatology 2003;37:1286–92. https://doi.org/10.1053/jhep.2003.50229.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Fracanzani, AL, Valenti, L, Bugianesi, E, Andreoletti, M, Colli, A, Vanni, E, et al.. Risk of severe liver disease in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with normal aminotransferase levels: a role for insulin resistance and diabetes. Hepatology 2008;48:792–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.22429.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

22. Williams, ALB, Hoofnagle, JH. Ratio of serum aspartate to alanine aminotransferase in chronic hepatitis relationship to cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 1988;95:734–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0016-5085(88)80022-2.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Sheth, SG, Flamm, SL, Gordon, FD, Chopra, S. AST/ALT ratio predicts cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Am J Gastroenterol 1998;93:44–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.044_c.x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

24. Nyblom, H, Berggren, U, Balldin, J, Olsson, R. High AST/ALT ratio may indicate advanced alcoholic liver disease rather than heavy drinking. Alcohol Alcohol 2004;39:336–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agh074.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

25. Sorbi, D, Boynton, J, Lindor, KD. The ratio of aspartate aminotransferase to alanine aminotransferase: potential value in differentiating nonalcoholic steatohepatitis from alcoholic liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol 1999;94:1018–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01006.x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

26. Nyblom, H, Björnsson, E, Simrén, M, Aldenborg, F, Almer, S, Olsson, R. The AST/ALT ratio as an indicator of cirrhosis in patients with PBC. Liver Int 2006;26:840–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1478-3231.2006.01304.x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

27. Guéchot, J, Boisson, RC, Zarski, J-P, Sturm, N, Calès, P, Lasnier, E, et al.. AST/ALT ratio is not an index of liver fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C when aminotransferase activities are determinate according to the international recommendations. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol 2013;37:467–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinre.2013.07.003.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

28. Wai, C-T, Greenson, JK, Fontana, RJ, Kalbfleisch, JD, Marrero, JA, Conjeevaram, HS, et al.. A simple noninvasive index can predict both significant fibrosis and cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 2003;38:518–26. https://doi.org/10.1053/jhep.2003.50346.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

29. Tsochatzis, EA, Crossan, C, Longworth, L, Gurusamy, K, Rodriguez-Peralvarez, M, Mantzoukis, K, et al.. Cost-effectiveness of noninvasive liver fibrosis tests for treatment decisions in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 2014;60:832–43. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.27296.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

30. Martin, J, Khatri, G, Gopal, P, Singal, AG. Accuracy of ultrasound and noninvasive markers of fibrosis to identify patients with cirrhosis. Dig Dis Sci 2015;60:1841–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-015-3531-1.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

31. Usluer, G, Erben, N, Aykin, N, Dagli, O, Aydogdu, O, Barut, S, et al.. Comparison of non-invasive fibrosis markers and classical liver biopsy in chronic hepatitis C. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2012;31:1873–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-011-1513-6.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

32. Huang, C, Seah, JJ, Tan, CK, Kam, JW, Tan, J, Teo, EK, et al.. Modified AST to platelet ratio index improves APRI and better predicts advanced fibrosis and liver cirrhosis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol 2021;45:101528. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinre.2020.08.006.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

33. Zhao, Y, Thurairajah, PH, Kumar, R, Tan, J, Teo, EK, Hsiang, JC. Novel non-invasive score to predict cirrhosis in the era of hepatitis C elimination: a population study of ex-substance users in Singapore. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2019;18:143–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hbpd.2018.12.002.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

34. Harrison, SA, Oliver, D, Arnold, HL, Gogia, S, Neuschwander-Tetri, BA. Development and validation of a simple NAFLD clinical scoring system for identifying patients without advanced disease. Gut 2008;57:1441–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.2007.146019.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

35. Park, J, Kim, G, Kim, B-S, Han, K-D, Kwon, SY, Park, SH, et al.. The associations of hepatic steatosis and fibrosis using fatty liver index and BARD score with cardiovascular outcomes and mortality in patients with new-onset type 2 diabetes: a nationwide cohort study. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2022;21:53. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-022-01483-y.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

36. Forns, X, Ampurdanès, S, Llovet, JM, Aponte, J, Quintó, L, Martínez-Bauer, E, et al.. Identification of chronic hepatitis C patients without hepatic fibrosis by a simple predictive model. Hepatology 2002;36:986–92. https://doi.org/10.1053/jhep.2002.36128.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

37. Nabi, O, Lacombe, K, Boursier, J, Mathurin, P, Zins, M, Serfaty, L. Prevalence and risk factors of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and advanced fibrosis in general population: the French Nationwide NASH-CO study. Gastroenterology 2020;159:791–3.e2. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2020.04.048.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

38. Romero Gómez, M, Ramírez Martín del Campo, M, Otero, MA, Vallejo, M, Corpas, R, Castellano-Megías, VM. Comparative study of two models that use biochemical parameters for the non-invasive diagnosis of fibrosis in patients with hepatitis C. Med Clin 2005;124:761–4. https://doi.org/10.1157/13075845.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

39. Hagström, H, Talbäck, M, Andreasson, A, Walldius, G, Hammar, N. Ability of noninvasive scoring systems to identify individuals in the population at risk for severe liver disease. Gastroenterology 2020;158:200–14. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2019.09.008.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

40. Cusi, K, Isaacs, S, Barb, D, Basu, R, Caprio, S, Garvey, WT, et al.. American Association of Clinical Endocrinology Clinical Practice Guideline for the diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in primary care and Endocrinology clinical settings: co-sponsored by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD). Endocr Pract 2022;28:528–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eprac.2022.03.010.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

41. Anstee, QM, Lawitz, EJ, Alkhouri, N, Wong, VW-S, Romero-Gomez, M, Okanoue, T, et al.. Noninvasive tests accurately identify advanced fibrosis due to NASH: baseline data from the S℡LAR trials. Hepatology 2019;70:1521–30. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.30842.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

42. Srivastava, A, Gailer, R, Tanwar, S, Trembling, P, Parkes, J, Rodger, A, et al.. Prospective evaluation of a primary care referral pathway for patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol 2019;71:371–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2019.03.033.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

43. Itakura, J, Kurosaki, M, Setoyama, H, Simakami, T, Oza, N, Korenaga, M, et al.. Applicability of APRI and FIB-4 as a transition indicator of liver fibrosis in patients with chronic viral hepatitis. J Gastroenterol 2021;56:470–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-021-01782-3.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

44. Xu, X-Y, Wang, W-S, Zhang, Q-M, Li, J-L, Sun, J-B, Qin, T-T, et al.. Performance of common imaging techniques vs serum biomarkers in assessing fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis B: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Clin Cases 2019;7:2022–37. https://doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i15.2022.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

45. Xu, X-Y, Kong, H, Song, R-X, Zhai, Y-H, Wu, X-F, Ai, W-S, et al.. The effectiveness of noninvasive biomarkers to predict hepatitis B-related significant fibrosis and cirrhosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy. PLoS One 2014;9:e100182. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0100182.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

46. Xiao, G, Yang, J, Yan, L. Comparison of diagnostic accuracy of aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index and fibrosis-4 index for detecting liver fibrosis in adult patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Hepatology 2015;61:292–302. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.27382.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

47. Sterling, RK, Lissen, E, Clumeck, N, Sola, R, Correa, MC, Montaner, J, et al.. Development of a simple noninvasive index to predict significant fibrosis in patients with HIV/HCV coinfection. Hepatology 2006;43:1317–25. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.21178.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

48. Kim, BK, Kim, DY, Park, JY, Ahn, SH, Chon, CY, Kim, JK, et al.. Validation of FIB-4 and comparison with other simple noninvasive indices for predicting liver fibrosis and cirrhosis in hepatitis B virus-infected patients. Liver Int 2010;30:546–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1478-3231.2009.02192.x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

49. Kim, BK, Kim, SA, Park, YN, Cheong, JY, Kim, HS, Park, JY, et al.. Noninvasive models to predict liver cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Liver Int 2007;27:969–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1478-3231.2007.01519.x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

50. Poynard, T, Bedossa, P. Age and platelet count: a simple index for predicting the presence of histological lesions in patients with antibodies to hepatitis C virus. METAVIR and CLINIVIR Cooperative Study Groups. J Viral Hepat 1997;4:199–208. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2893.1997.00141.x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

51. Bedossa, P, Poynard, T. An algorithm for the grading of activity in chronic hepatitis C. The METAVIR Cooperative Study Group. Hepatology 1996;24:289–93. https://doi.org/10.1053/jhep.1996.v24.pm0008690394.Suche in Google Scholar

52. Group TFMCS, Bedossa, P. Intraobserver and interobserver variations in liver biopsy interpretation in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 1994;20:15–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.1840200104.Suche in Google Scholar

53. Dittrich, M, Milde, S, Dinkel, E, Baumann, W, Weitzel, D. Sonographic biometry of liver and spleen size in childhood. Pediatr Radiol 1983;13:206–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00973157.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

54. Batts, KP, Ludwig, J. Chronic hepatitis. An update on terminology and reporting. Am J Surg Pathol 1995;19:1409–17. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000478-199512000-00007.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

55. Roh, YH, Kang, B-K, Jun, DW, Lee, C, Kim, M. Role of FIB-4 for reassessment of hepatic fibrosis burden in referral center. Sci Rep 2021;11:13616. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-93038-6.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

56. Moolla, A, Motohashi, K, Marjot, T, Shard, A, Ainsworth, M, Gray, A, et al.. A multidisciplinary approach to the management of NAFLD is associated with improvement in markers of liver and cardio-metabolic health. Frontline Gastroenterol 2019;10:337–46. https://doi.org/10.1136/flgastro-2018-101155.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

57. McPherson, S, Hardy, T, Dufour, J-F, Petta, S, Romero-Gomez, M, Allison, M, et al.. Age as a confounding factor for the accurate non-invasive diagnosis of advanced NAFLD fibrosis. Am J Gastroenterol 2017;112:740–51. https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2016.453.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

58. Canivet, CM, Costentin, C, Irvine, KM, Delamarre, A, Lannes, A, Sturm, N, et al.. Validation of the new 2021 EASL algorithm for the noninvasive diagnosis of advanced fibrosis in NAFLD. Hepatology 2023;77:920–30. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.32665.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

59. Hagström, H, Talbäck, M, Andreasson, A, Walldius, G, Hammar, N. Repeated FIB-4 measurements can help identify individuals at risk of severe liver disease. J Hepatol 2020;73:1023–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2020.06.007.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

60. McPherson, S, Stewart, SF, Henderson, E, Burt, AD, Day, CP. Simple non-invasive fibrosis scoring systems can reliably exclude advanced fibrosis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Gut 2010;59:1265–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.2010.216077.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

61. Degos, F, Perez, P, Roche, B, Mahmoudi, A, Asselineau, J, Voitot, H, et al.. Diagnostic accuracy of FibroScan and comparison to liver fibrosis biomarkers in chronic viral hepatitis: a multicenter prospective study (the FIBROSTIC study). J Hepatol 2010;53:1013–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2010.05.035.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

62. Madsen, BS, Thiele, M, Detlefsen, S, Kjærgaard, M, Møller, LS, Trebicka, J, et al.. PRO-C3 and ADAPT algorithm accurately identify patients with advanced fibrosis due to alcohol-related liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2021;54:699–708. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.16513.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

63. Angulo, P, Hui, JM, Marchesini, G, Bugianesi, E, George, J, Farrell, GC, et al.. The NAFLD fibrosis score: a noninvasive system that identifies liver fibrosis in patients with NAFLD. Hepatology 2007;45:846–54. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.21496.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

64. Wei, M, Xu, Z, Pan, X, Zhang, X, Liu, L, Yang, B, et al.. Serum GP73 – an additional biochemical marker for liver inflammation in chronic HBV infected patients with normal or slightly raised ALT. Sci Rep 2019;9:1170. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-36480-3.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

65. Ampuero, J, Pais, R, Aller, R, Gallego-Durán, R, Crespo, J, García-Monzón, C, et al.. Development and validation of Hepamet fibrosis scoring system – a simple, noninvasive test to identify patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with advanced fibrosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020;18:216–25.e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2019.05.051.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

66. Benlloch, S, Berenguer, M, Prieto, M, Rayón, JM, Aguilera, V, Berenguer, J. Prediction of fibrosis in HCV-infected liver transplant recipients with a simple noninvasive index. Liver Transpl 2005;11:456–62. https://doi.org/10.1002/lt.20381.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

67. Xie, S-B, Yao, J-L, Zheng, R-Q, Peng, X-M, Gao, Z-L. Serum hyaluronic acid, procollagen type III and IV in histological diagnosis of liver fibrosis. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2003;2:69–72.Suche in Google Scholar

68. Nielsen, MJ, Veidal, SS, Karsdal, MA, Ørsnes-Leeming, DJ, Vainer, B, Gardner, SD, et al.. Plasma Pro-C3 (N-terminal type III collagen propeptide) predicts fibrosis progression in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Liver Int 2015;35:429–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.12700.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

69. Daniels, SJ, Leeming, DJ, Eslam, M, Hashem, AM, Nielsen, MJ, Krag, A, et al.. ADAPT: an algorithm incorporating PRO-C3 accurately identifies patients with NAFLD and advanced fibrosis. Hepatology 2019;69:1075. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.30163.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

70. Kumagai, E, Mano, Y, Yoshio, S, Shoji, H, Sugiyama, M, Korenaga, M, et al.. Serum YKL-40 as a marker of liver fibrosis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Sci Rep 2016;6:35282. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep35282.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

71. Tran, A, Benzaken, S, Saint-Paul, M-C, Guzman-Granier, E, Hastier, P, Pradier, C, et al.. Chondrex (YKL-40), a potential new serum fibrosis marker in patients with alcoholic liver disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2000;12:989–93. https://doi.org/10.1097/00042737-200012090-00004.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

72. Jiang, Z, Wang, S, Jin, J, Ying, S, Chen, Z, Zhu, D, et al.. The clinical significance of serum chitinase 3-like 1 in hepatitis B – related chronic liver diseases. J Clin Lab Anal 2020;34:e23200. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcla.23200.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

73. Saitou, Y, Shiraki, K, Yamanaka, Y, Yamaguchi, Y, Kawakita, T, Yamamoto, N, et al.. Noninvasive estimation of liver fibrosis and response to interferon therapy by a serum fibrogenesis marker, YKL-40, in patients with HCV-associated liver disease. World J Gastroenterol 2005;11:476–81. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v11.i4.476.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

74. Mak, L-Y, Wong, DK-H, Cheung, K-S, Seto, W-K, Lai, C-L, Yuen, M-F. Role of serum M2BPGi levels on diagnosing significant liver fibrosis and cirrhosis in treated patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Clin Transl Gastroenterol 2018;9:e163. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41424-018-0020-9.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

75. Hur, M, Park, M, Moon, H-W, Choe, WH, Lee, CH. Comparison of non-invasive clinical algorithms for liver fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis B to reduce the need for liver biopsy: application of enhanced liver fibrosis and Mac-2 binding protein glycosylation isomer. Ann Lab Med 2022;42:249–57. https://doi.org/10.3343/alm.2022.42.2.249.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

76. Parkes, J, Roderick, P, Harris, S, Day, C, Mutimer, D, Collier, J, et al.. Enhanced liver fibrosis test can predict clinical outcomes in patients with chronic liver disease. Gut 2010;59:1245–51. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.2009.203166.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

77. Day, J, Patel, P, Parkes, J, Rosenberg, W. Derivation and performance of standardized enhanced liver fibrosis (ELF) test thresholds for the detection and prognosis of liver fibrosis. J Appl Lab Med 2019;3:815–26. https://doi.org/10.1373/jalm.2018.027359.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

78. Wong, GL-H, Chan, HL-Y, Choi, PC-L, Chan, AW-H, Yu, Z, Lai, JW-Y, et al.. Non-invasive algorithm of enhanced liver fibrosis and liver stiffness measurement with transient elastography for advanced liver fibrosis in chronic hepatitis B. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014;39:197–208. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.12559.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

79. Becker, L, Salameh, W, Sferruzza, A, Zhang, K, ng Chen, R, Malik, R, et al.. Validation of hepascore, compared with simple indices of fibrosis, in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection in United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009;7:696–701. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2009.01.010.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

80. Adams, LA, Bulsara, M, Rossi, E, DeBoer, B, Speers, D, George, J, et al.. Hepascore: an accurate validated predictor of liver fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C infection. Clin Chem 2005;51:1867–73. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2005.048389.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

81. European Association for the Study of the Liver EASLEuropean Association for the Study of Diabetes EASDEuropean Association for the Study of Obesity EASO. EASL–EASD–EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol 2016;64:1388–402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2015.11.004.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

82. Graupera, I, Thiele, M, Serra-Burriel, M, Caballeria, L, Roulot, D, Wong, GL-H, et al.. Low accuracy of FIB-4 and NAFLD fibrosis scores for screening for liver fibrosis in the population. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022;20:2567–76.e6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2021.12.034.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

83. Munteanu, M, Tiniakos, D, Anstee, Q, Charlotte, F, Marchesini, G, Bugianesi, E, et al.. Diagnostic performance of FibroTest, SteatoTest and ActiTest in patients with NAFLD using the SAF score as histological reference. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2016;44:877–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.13770.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

84. Salkic, NN, Jovanovic, P, Hauser, G, Brcic, M. FibroTest/fibrosure for significant liver fibrosis and cirrhosis in chronic hepatitis B: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2014;109:796–809. https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2014.21.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

85. Naveau, S, Gaudé, G, Asnacios, A, Agostini, H, Abella, A, Barri-Ova, N, et al.. Diagnostic and prognostic values of noninvasive biomarkers of fibrosis in patients with alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology 2009;49:97–105. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.22576.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

86. Vali, Y, Lee, J, Boursier, J, Spijker, R, Verheij, J, Brosnan, MJ, et al.. FibroTest for evaluating fibrosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Med 2021;10:2415. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10112415.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

87. Munteanu, M, Pais, R, Peta, V, Deckmyn, O, Moussalli, J, Ngo, Y, et al.. Long-term prognostic value of the FibroTest in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, compared to chronic hepatitis C, B, and alcoholic liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2018;48:1117–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.14990.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

88. Yao, M, Wang, L, Leung, PSC, Li, Y, Liu, S, Wang, L, et al.. The clinical significance of GP73 in immunologically mediated chronic liver diseases: experimental data and literature review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2018;54:282–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12016-017-8655-y.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

89. Yang, S-L, Zeng, C, Fang, X, He, Q-J, Liu, L-P, Bao, S-Y, et al.. Hepatitis B virus upregulates GP73 expression by activating the HIF-2α signaling pathway. Oncol Lett 2018;15:5264–70. https://doi.org/10.3892/ol.2018.7955.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

90. Xu, Z, Liu, L, Pan, X, Wei, K, Wei, M, Liu, L, et al.. Serum Golgi protein 73 (GP73) is a diagnostic and prognostic marker of chronic HBV liver disease. Medicine 2015;94:e659. https://doi.org/10.1097/md.0000000000000659.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

91. Xu, Z, Shen, J, Pan, X, Wei, M, Liu, L, Wei, K, et al.. Predictive value of serum Golgi protein 73 for prominent hepatic necroinflammation in chronic HBV infection. J Med Virol 2018;90:1053–62. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.25045.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

92. Marrero, JA, Romano, PR, Nikolaeva, O, Steel, L, Mehta, A, Fimmel, CJ, et al.. GP73, a resident Golgi glycoprotein, is a novel serum marker for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2005;43:1007–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2005.05.028.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

93. Gatselis, NK, Tornai, T, Shums, Z, Zachou, K, Saitis, A, Gabeta, S, et al.. Golgi protein-73: a biomarker for assessing cirrhosis and prognosis of liver disease patients. World J Gastroenterol 2020;26:5130–45. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v26.i34.5130.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

94. Ke, M-Y, Wu, X-N, Zhang, Y, Wang, S, Lv, Y, Dong, J. Serum GP73 predicts posthepatectomy outcomes in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Transl Med 2019;17:140. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-019-1889-0.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

95. Li, Y, Yang, Y, Li, Y, Zhang, P, Ge, G, Jin, J, et al.. Use of GP73 in the diagnosis of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and the staging of hepatic fibrosis. J Int Med Res 2021;49:03000605211055378. https://doi.org/10.1177/03000605211055378.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

96. Cao, Z, Li, Z, Wang, H, Liu, Y, Xu, Y, Mo, R, et al.. Algorithm of Golgi protein 73 and liver stiffness accurately diagnoses significant fibrosis in chronic HBV infection. Liver Int 2017;37:1612–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.13536.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

97. Cao, Z, Li, Z, Wang, Y, Liu, Y, Mo, R, Ren, P, et al.. Assessment of serum Golgi protein 73 as a biomarker for the diagnosis of significant fibrosis in patients with chronic HBV infection. J Viral Hepat 2017;24:57–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/jvh.12786.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

98. Rigor, J, Diegues, A, Presa, J, Barata, P, Martins-Mendes, D. Noninvasive fibrosis tools in NAFLD: validation of APRI, BARD, FIB-4, NAFLD fibrosis score, and Hepamet fibrosis score in a Portuguese population. Postgrad Med 2022;134:435–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/00325481.2022.2058285.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

99. Zambrano-Huailla, R, Guedes, L, Stefano, JT, de Souza, AAA, Marciano, S, Yvamoto, E, et al.. Diagnostic performance of three non-invasive fibrosis scores (Hepamet, FIB-4, NAFLD fibrosis score) in NAFLD patients from a mixed Latin American population. Ann Hepatol 2020;19:622–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aohep.2020.08.066.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

100. Higuera-de-la-Tijera, F, Córdova-Gallardo, J, Buganza-Torio, E, Barranco-Fragoso, B, Torre, A, Parraguirre-Martínez, S, et al.. Hepamet fibrosis score in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease patients in Mexico: lower than expected positive predictive value. Dig Dis Sci 2021;66:4501–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-020-06821-2.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

101. Tafur Sánchez, CN, Durá Gil, M, Alemán Domínguez Del Río, A, Hernández Pérez, CM, Mora Cuadrado, N, de la Cuesta, SG, et al.. The practical utility of non-invasive indices in metabolic hepatic steatosis. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr 2022;69:418–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.endien.2022.06.009.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

102. Younes, R, Caviglia, GP, Govaere, O, Rosso, C, Armandi, A, Sanavia, T, et al.. Long-term outcomes and predictive ability of non-invasive scoring systems in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol 2021;75:786–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2021.05.008.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

103. Ampuero, J, Aller, R, Gallego-Durán, R, Crespo, J, Calleja, JL, García-Monzón, C, et al.. Significant fibrosis predicts new-onset diabetes mellitus and arterial hypertension in patients with NASH. J Hepatol 2020;73:17–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2020.02.028.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

104. Alonso, C, Fernández-Ramos, D, Varela-Rey, M, Martínez-Arranz, I, Navasa, N, Van Liempd, SM, et al.. Metabolomic identification of subtypes of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology 2017;152:1449–61.e7. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2017.01.015.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

105. Cantero, I, Elorz, M, Abete, I, Marin, BA, Herrero, JI, Monreal, JI, et al.. Ultrasound/Elastography techniques, lipidomic and blood markers compared to Magnetic Resonance Imaging in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease adults. Int J Med Sci 2019;16:75–83. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijms.28044.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

106. Mayo, R, Crespo, J, Martínez-Arranz, I, Banales, JM, Arias, M, Mincholé, I, et al.. Metabolomic-based noninvasive serum test to diagnose nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: results from discovery and validation cohorts. Hepatol Commun 2018;2:807–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep4.1188.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

107. Bril, F, Millán, L, Kalavalapalli, S, McPhaul, MJ, Caulfield, MP, Martinez-Arranz, I, et al.. Use of a metabolomic approach to non-invasively diagnose non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Obes Metab 2018;20:1702–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/dom.13285.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

108. Rostami, S, Parsian, H. Hyaluronic acid: from biochemical characteristics to its clinical translation in assessment of liver fibrosis. Hepat Mon 2013;13:e13787. https://doi.org/10.5812/hepatmon.13787.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

109. Gudowska, M, Cylwik, B, Chrostek, L. The role of serum hyaluronic acid determination in the diagnosis of liver diseases. Acta Biochim Pol 2017;64:451–7. https://doi.org/10.18388/abp.2016_1443.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

110. Stickel, F, Poeschl, G, Schuppan, D, Conradt, C, Strenge-Hesse, A, Fuchs, FS, et al.. Serum hyaluronate correlates with histological progression in alcoholic liver disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2003;15:945–50. https://doi.org/10.1097/00042737-200309000-00002.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

111. Mizuno, M, Shima, T, Oya, H, Mitsumoto, Y, Mizuno, C, Isoda, S, et al.. Classification of patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease using rapid immunoassay of serum type IV collagen compared with liver histology and other fibrosis markers. Hepatol Res 2017;47:216–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/hepr.12710.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

112. Sowa, J-P, Heider, D, Bechmann, LP, Gerken, G, Hoffmann, D, Canbay, A. Novel algorithm for non-invasive assessment of fibrosis in NAFLD. PLoS One 2013;8:e62439. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0062439.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central