Rang clauses in modern mandarin Chinese: a Cardiff Grammar approach

-

Dajun Xiang

Dajun Xiang

ABSTRACT

This study investigates the rang clauses in modern mandarin Chinese from the Cardiff Grammar approach with the aim to answer a central question concerning the clauses, i.e., what are the syntactic functions of rang in the clauses? After reviewing previous studies and clarifying the basic notions established in the Cardiff Grammar, the study analyzes and discusses the syntax of the generally recognized four types of the clauses with the objective to match semantic functions to syntactic elements. The study shows that when rang expresses “concession,” it functions as a main verb, which expounds the Predicator of the clause; when it means “causation,” it is a causative verb, which expresses an “influential process,” with the nominal group following rang as the Subject of the embedded clause; when rang is equal to Chinese “bei,” it is a preposition, whose function is to introduce the Agent of the action and syntactically it together with its following nominal group forms a prepositional group, expounding the Complement of the clause; when rang expresses “wishes,” it functions as a Mood marker and syntactically it is analyzed as the direct element of the clause, i.e., Let Element.

1. Introduction

Rang clauses in modern mandarin Chinese refer to the Chinese clauses that contain the word Rang (让), as illustrated by the following examples1:

| (1) | 你 | 让 | 着 | 他 | 点 儿。 |

| ni | rang | zhe | ta | dian er. | |

| you | concede | he | a little. | ||

| “You should concede to him a little.” | |||||

| (2) | 这 | 颜 色 | 让 | 人 | 心 中 | 充 满 | 暖 意。 | (BCC_1986) |

| zhe | yan se | rang | ren | xin zhong | chong man | nuan yi | ||

| This | color | make | people | heart-in | fill | warmness. | ||

| “This color makes people feel warm in the heart.” | ||||||||

| (3) | 窗 户 | 让 | 大风 | 吹 | 坏 | 了 | 一扇。 |

| Chuang hu | rang | da feng | chui | huai | le | yi shan. | |

| window | by | high wind | blow | bad | a piece. | ||

| “A window has been blown out by the high wind.” | |||||||

| (4) | 让 | 我 们 | 永 远 | 在 | 一 起! |

| rang | wo men | yong yuan | zai | yi qi! | |

| let | we | forever | be | together! | |

| “Let us be together forever.” | |||||

In all the above clauses, rang seems to have different meanings and plays different grammatical functions. In (1), rang has the meaning of “concede or yield,” which can function as a verb. In (2), rang is with the meaning of “make (something happen),” which can be seen as a causative verb. In (3), the meaning of rang seems to be equal to the Chinese word bei (被), which functions as a passive marker roughly corresponding to the usage of English by. In (4), it seems that no exact lexical meaning can be found with rang and the only function of it seems to be a Mood marker. Rang originally means “concede,” which is a verb (Lv 1999: 461; Zhang 2005). However, in the process of grammaticalization, the full verb rang has altered its semantic range in some way, but its earlier meanings may coexist with later ones, resulting in “a certain lack of fit between form and interpretation” (Davies 1986, 247). Owing to the semantic and syntactic complexity of rang in modern mandarin Chinese, a great many studies have been carried out dealing with such clauses in the literature and various conclusions and explanations are obtained accordingly (e.g., Ding et al. 1999; Zhang 1980; Li 1986; Lv 1999; Zhu 1999; Fan 2000; Wang 2002; He 2004; Hu 2009). However, there does not appear to be a very self-contained investigation concerning the essential problem in the clauses, i.e., what basic structures they represent, and little attention has been paid to the typical insights into such clauses that can be derived from an analysis by drawing on Systemic Functional Linguistics (Matthiessen 1995; Halliday 2014).

The purpose of this paper is to conduct a comprehensive analysis of the rang clauses by matching semantic features to syntactic elements from the framework of the Cardiff Grammar (CG) – a model of Systemic Functional Linguistics (see Fawcett 1980, 2000, 2008; Fawcett, Tucker, and Lin 1993; Tucker 1998; He et al. 2015). Based on the analysis of the corpus data from three main Chinese corpora (i.e., Corpusonline, CCL, and BCC),2 it aims to answer a central question concerning the clauses, viz. what are the syntactic functions of rang in the clauses? In doing so, the essential problem that has been recognized and discussed in much of the literature can be properly handled.

Section 2 reviews how rang clauses have been accounted for in the literature, where different views concerning the structure of the clauses will be compared. Section3 makes a sketch of the basic notions and essential principles established in the CG’s syntactic analysis. Section 4 focuses on the functional syntactic analyses of the clauses, matching the acknowledged semantic functions to their corresponding syntactic elements. After the detailed analyses of the clauses, section 5 summarizes the major findings of the study and makes proposals for future research.

2. Previous studies of rang clauses

In modern mandarin Chinese, rang is a word used with very high frequency. Because of its semantic and syntactic complexity, it has interested many scholars from the Chinese linguistic fields and various aspects of rang clauses have been investigated. Generally, the related literature focuses on the grammatical functions of rang and its relevant syntactic structures. Though there is some consensus being reached, opinions vary regarding their corresponding syntax in previous studies. This section will review the previous studies according to the order of the examples listed in the introduction section, since these four examples are typical representatives of the controversial issues concerned in the literature.3

As, for example (1), it is generally agreed that the grammatical function of rang, in this case, is a verb, which expresses the meaning of “concession” (Lv 1999, 461). Throughout the literature, it seems that few disputes can be found with this kind of usage. According to the recognized consensus, the verb rang functions as the “Predicator” of the clause,4 and the related syntactic structure may vary according to the situation it is used in or as it is collocated with other words. Concerning example (1), the syntactic structure is that of “Subject+Predicator+Object,” where ni is the Subject, rang is the Predicator, ta is the Object. There are other syntactic elements in this clause, where zhe is the Auxiliary and dian er is the Adjunct. Since this kind of usage of rang has reached a consensus in the literature, we will not discuss it in detail anymore.

Regarding example (2), the grammatical function of rang and its corresponding structures have been the subject of much controversy. For the convenience of running the text, we will formalize example (2) as: ngp1+ rang+ngp2 + V+ ngp3,5 where ngp1 is zhe yan se, ngp2 is ren, V is chong man, and ngp3 is nuan yi. Li (2007, 27–29) holds the idea that rang in this case is a transitive verb, and the VP (i.e., V+ ngp3) is the Complement of the Object (i.e., ngp2). Thus, example (2) has the structure of “S(ngp1)+P(rang)+O(ngp2)+OC(V+ ngp3).”6 Ding et al. (1999, 100) propose that rang in this case is a common verb. And with their dichotomy approach, example (2) may have the structure of “S1(ngp1)+VP1 + S2(ngp2)+VP2,” where the verb rang together with the rest part of the clause forms VP1, and V together with ngp3 forms VP2. Similar to Ding et al., (1999) Lv (1999, 461–462) regards rang in the example as a bifunctional verb, i.e., the ngp2 is both the Object of rang and the Subject of the next V. According to his analysis, example (2) may have the structure of “S1(ngp1)+P1(rang)+O1/S2(ngp2)+P2(V)+O2(ngp3).” Shen, He, and Yang (2001) and some others (He and Wang 2002; He 2004) propose that rang in this case is a light verb and the embedded clause (i.e., “ngp2 + V+ ngp3”) is the Complement. Thus, example (2) in their analyses may have the structure of “S(ngp1)+V(rang)+C(ngp2 + V+ ngp3).” Different from all the above analyses, Zhu (1999: 182/204) argues that the causative rang should not be regarded as a verb but a preposition. In his proposal, example (2) is a special kind of “serial predicator construction,” where the preposition together with V forms a serial Predicator, and ngp2 and ngp3 are two different Objects. Zhang (1980) and Fan (2000) also regard this rang as a preposition. But different from Zhu, they propose that the preposition rang together with ngp2 should be treated as the Adjunct of the clause, which is used to modify the following predicate verb.

With example (3), it is overwhelmingly recognized in the literature that rang is equal to the usage of Chinese word bei in passive clauses (Lv 1999: 462; Li 2001, 219), whose only function is to introduce the Agent of the action. As for the grammatical function of this rang, it is generally proposed that it is a preposition. As the common practice in Chinese grammar (Huang and Liao 2002: 91; Wang et al. 2006: 340; Zhu 2002, 60), this preposition together with its following nominal group will function as the Adjunct of the clause. With this idea in mind, rang da feng in example (3) will be analyzed as the Adjunct of the clause. Therefore, example (3) may have the structure of “S + A + P + O,” where chuang hu is the Subject, chui (huai le) is the Predicator, and yi shan is the Object. However, other views are also heard in the literature. Ding et al. (1999: 95/100-102) propose that this rang is a sub-verb. A “sub-verb” in their sense is a secondary verb, which is a subtype of verbs. There are two distinct features with this type of verb: one is that it is seldom used as the main part of the predicate; the other is that it should be followed by an Object. Thus, in Ding et al.’s analysis, rang da feng is part of the predicate and da feng is the Object of the sub-verb rang in example (3). In analyzing passive bei clauses, Wang (2002: 80–81/171) claims that bei in passive clauses is an auxiliary verb, but unfortunately no syntactic structures are given for this kind of bei clauses. From his claim, rang in example (3) may also be treated as an auxiliary verb. Besides these two different opinions, Lv (1999, 463) and Li (2001, 219–223) argue that when bei is used before a solid word (content noun), it is a preposition; when it is used before a verb, it is a passive auxiliary verb. According to this idea, rang may have similar qualities, that is if it is used before a verb, it could also be a passive auxiliary verb.

Finally, let us see what has been accounted for with example (4). Literature on this usage of rang can seldom be found unfortunately. It is only pointed out by Lv (1999, 462) that rang in this kind of clause is a verb, which is to express “wishes,” but no syntactic explanation has been offered. Adopting the CG’s framework, in their functional syntactic analysis of Chinese, He et al. (2015, 58) claim that this rang should be analyzed as Let Element, but no explication is given unfortunately.

From what has been reviewed above, diverse analyses have been proposed in the literature in terms of rang’s grammatical functions and its related syntactic structures. However, from the functional perspective, none of these competing views seem to have systematically matched the semantic functions to syntactic elements of the clauses.7 All these indicate that a function-oriented study is needed for shedding light on the very nature of the clauses. Before our functional analysis of the clauses, the basic notions and principles of syntactic description in the CG will be briefly introduced for the purpose of setting our theoretical framework.

3. Basic notions and principles of syntactic description in the Cardiff Grammar

Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL) is a linguistic approach that regards language as a social semiotic system. Being an important model of SFL, the general approach taken by the CG is functional rather than formal. However, this should not be taken as sanctioning the linguist to pay less attention to the problems of realizing meaning at the level of form. In Fawcett’s (2008, 15) opinion, a good functional theory of language should be strong at the levels of both function and form. The syntactic description at the level of form has also been a constant concern for linguists working in the CG’s framework, who try to answer the simple question: “How meanings are realized in form?” This section will first briefly outline the basic syntactic categories and relationships in the CG, and then the principles of syntactic description generally established in the CG will be introduced.

3.1. Basic syntactic categories and relationships in the Cardiff Grammar

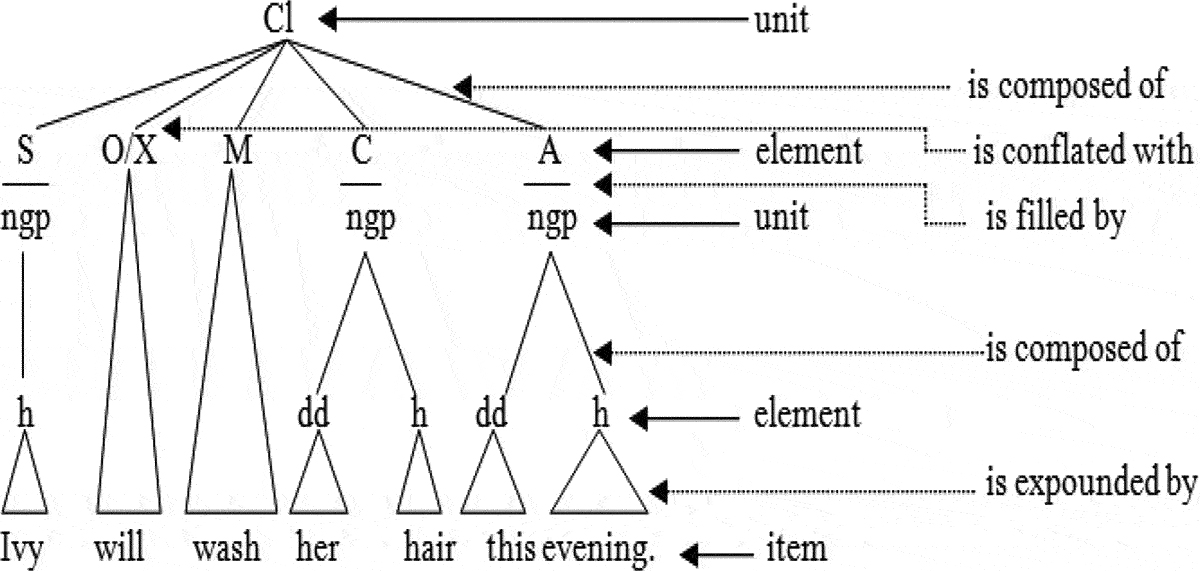

Three basic syntactic categories and four relationships are recognized in the CG (Fawcett 2000: 187–260, 2008, 73–75). As represented in Figure 1, the three basic categories are unit, element, and item, and the four basic relationships are componence, filling, exponence, and conflation.8 In Figure 1, at the top of the tree diagram is the unit of the clause, which in this example is composed of five elements, i.e. Subject, Operator/Auxiliary, Main Verb, Complement, and Adjunct. The Subject here is filled by a nominal group, which is composed of the element of head only and expounded by the item Ivy. The element of Operator is conflated with Auxiliary and together expounded by the item will. The Main Verb is expounded by the item wash. The clause element of Complement is filled by a nominal group, which is composed of another two elements, i.e., a deictic determiner (expounded by the item her) and a head (expounded by the item hair). The last clause element is an Adjunct, which is filled by a nominal group too, which again is composed of another two elements, a deictic determiner (expounded by the items this) and a head (expounded by the item evening).

The basic categories and relationships of syntax in the Cardiff Grammar.

As we can see from Figure 1, the CG has abolished the Hallidayan “multiple structures,” and adopted a single, integrated structure in its syntactic representation. The multifunctional nature of language is displayed in the representation of the meanings. Fawcett claims that it is the role of syntax to show the integration of these intermittent “strands of meaning” in a single structure (Fawcett 2000, 147). Thus, for example, the experiential meaning of “Ivy will wash her hair” is realized through the three elements of Subject, Main Verb, and Complement that express the choices in TRANSITIVITY, and the interpersonal meaning of “information giver” is realized through the two elements of Subject and Operator that express the choice of MOOD.

3.2. Basic principles of syntactic description in the CG

Generally, two principles are maintained in the CG’s syntactic description: (1) the principle of function-orientation; and (2) the principle of meaning-centeredness. The principle of function-orientation means that the perspective of syntactic description is functional rather than formal. This is determined by the nature of SFL, which is functional in orientation rather than formal (Halliday 2006, 443–444). Thus, when functional and formal criteria are in conflict, functional criteria are placed above formal criteria as long as they do not lose contact with the level of form (Fawcett 2008, 111). Let us compare example (5) and (6).

(5) Ivy gave Ike money.

(6) Ivy gave money to Ike.

According to Quirk et al. (1985, 59), example (5) has the structure of “S + V+ Oi+Od,”9 that is, Ike is an Indirect Object and money is a Direct Object; while example (6) has the structure of “S + V + O + A,” that is, money is still an Object, but to Ike is an Adjunct. In the CG, both (5) and (6) will have the same functional structure, i.e., “S + M + C + C.”10 This is because the CG maintains the rule that a Participant Role (PR) is a role that is “expected” by the Process (Fawcett 2008, 137). Since the Process of “give” in both examples is the same (i.e., “someone gives something to someone”), it will predict the same PRs. Thus, the PR played by Ike in both examples will be the same, no matter if it appears in the form of Ike or to Ike. This does not mean that the two examples have the same meaning. The difference between them can be explicated informationally. In normal context, the information focus in (5) falls on money, which may answer the question of “What did Ivy give Ike?”; while in (6), it falls on Ike, which may answer the question of “Who did Ivy give money to?” Therefore, from the CG’s perspective, we can claim that the traditional grammar’s way of analyzing to Ike into an Adjunct not an Object is depending on form rather than function, since in functional description of a language, the fact that a PR that is predicted by the Process is expressed as a prepositional group (in this case, to Ike) is not strong enough to turn a PR into a Circumstantial Role (CR).11

The principle of meaning-centeredness means in syntactic description the starting point is semantics or meaning rather than syntax itself. This principle is also determined by the nature of SFL, which is semantic rather than syntactic in orientation (Halliday 2006, 443–444), since SFL is a theory of language as choice between meanings. However, this does not mean that the syntax of a language is not to be accounted for in a functional linguistic theory, since the form level of syntax is most directly observable (Fawcett 2008, 15). To illustrate this principle, let us look at the CG’s syntactic analysis of example (7) and (8).

(7) He raised the problem again.

(8) He brought up the problem again.

According to traditional grammar, up in example (8) will be analyzed as Adjunct. This analysis is to a great degree based on form not meaning. We know that brought up in (8) means virtually the same thing as raise in (7), except that they may be used in different registers. From the CG’s perspective, brought up in (8) realizes the same Process of “raising” in (7), because semantically they expect almost the same PRs. The difference between them is that in example (8) a single Process (at the level of meaning) is realized in more than one word (at the level of form). In order to solve this “phrasal verb” problems in traditional grammars, Fawcett (2008, 184) proposed another clause element, i.e., Main Verb Extension (MEx), which functions as an “extension” of the Main Verb (M). This clause element together with the Main Verb jointly expresses a Process. Thus, in example (7), the Process is typically expressed in the M raised; while in (8), the same Process is jointly expressed in the M brought and MEx up. Thus, from the CG’s perspective, up is not an Adjunct but a MEx realizing part of the Process.

It is not always easy to draw a distinct line between the two principles mentioned above. What the two principles remind us is that more attention of meaning has been maintained in the CG’s syntactic analysis, because meaning is realized by form and syntactic analysis serves for meaning analysis. In the ensuing section, the syntax of rang clauses will be investigated from the CG’s perspective, and we will see whether typical insights into such clauses that can be derived from an analysis by drawing on the CG.

4. The syntax of rang clauses: a Cardiff Grammar perspective

As reviewed in section 2 above, there is no really satisfying account of the syntactic functions of rang and its related structures in the literature. Based on the principles established in the CG’s syntactic description, this section is devoted to the functional syntax of the clauses with the aim to match semantic features to syntactic elements. In order to comprehensively and systematically explore the functional syntax of the clauses, 5000 samples of rang clauses in the three main Chinese corpora have been investigated. Through careful manual analysis of the functions and semantics of rang tokens in the corpora, four basic categories of rang usages have been found, i.e., “concession” usage, “causation” usage, “bei” usage and “wish” usage. In the following four subsections, the syntax of each usage will be discussed in detail from the CG’s perspective.

4.1. The syntax of rang clauses expressing “concession”

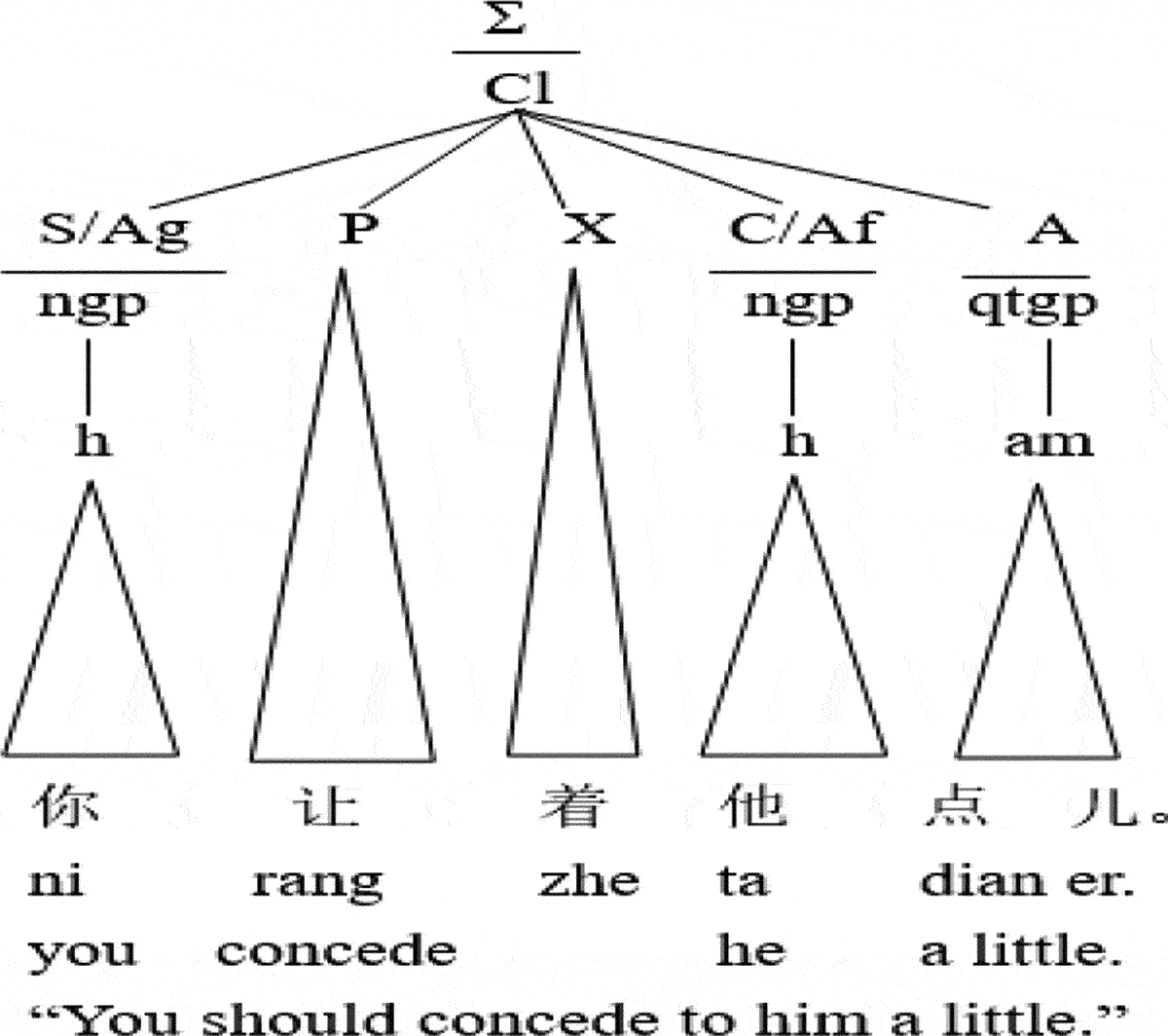

This “Concession” usage of rang is the most common one in the corpora, accounting for 46% of the samples. It is often used in situations like competition, argumentation, and entertainment, etc., which means giving advantages to others such as tui rang (退让, concede) and qian rang (谦让, yield), or avoiding something such as bi rang (避让, avoid), etc. Syntactically, this usage of rang is usually followed by a nominal Complement such as rang lu (让路, give the way to), rang zuo (让座, give up one’s seat to), and sometimes followed by two Complements such as rang ta yi ci ji hui (让他一次机会, give him an opportunity). As reviewed in section 2, a consensus has been reached regarding the grammatical function of this rang, i.e., it is a verb, which serves the function of the Predicator. Since this kind of usage of rang seldom causes disputes in the literature, no more discussion will be elaborated. And we just analyze the syntax of this kind of rang clause from the CG’s perspective in order to show how the structure will be represented functionally. Since the rang clause of example (1) mentioned in the introduction section is a typical one expressing “concession” meaning, we will not seek new examples for our illustration (see Figure 2).12

The analysis of rang clauses expressing “concession”.

As we can see from Figure 2, we analyze rang in (1) as a Predicator, which expresses Process meaning. From the perspective of transitivity,13 the Predicator rang in the clause realizes an “action process,” which expects two PRs. Thus, the Subject, which is filled by a nominal group and expounded by the item ni, is conflated with the PR of Agent; the Complement, which is filled by a nominal group and expounded by the item ta, is conflated with the PR of Affected. In this clause, zhe is an Auxiliary, marking present tense; and dian er is a quantity group, which fills the Adjunct of the clause.

4.2. The syntax of rang clauses expressing “causation”

This kind of rang usage is also used frequently, taking 34% of the data collected. Here “causation” is used in a broad sense, including meanings like “allowance,” “tolerance,” and “permission” etc. As reviewed in section 2, the causative meaning and its related syntax of rang have been the subject of much controversy in the literature. Some have treated rang as a transitive verb (Li 2007, 27–29), a common verb (Ding et al. 1999, 100), a bifunctional verb (Lv 1999, 461–462), a light verb (Shen, He, and Yang 2001), and there are still others who analyze it as a preposition (Zhu 1999:182; Zhang 1980; Fan 2000). Because these scholars assign different grammatical functions to this rang, various syntactic structures have been offered for different purposes. Taking example (2) to illustrate, let us comment the analyses conducted in the literature to see whether they have consistently matched semantic features to syntactic elements.

First, we deny the view that rang, in this case, is a preposition, since we can still find lexical meanings of “causation” in it. If it is indeed a preposition, it will be categorized as a function word (see Wang et al. 2006, 281). But from our analysis of the corpus data, the causative meaning is till obvious to see. Thus, although the meaning of causative rang is grammaticalized to some degree, it is still too radical to treat it as a preposition. We thus argue that rang in this sense is still a verb as mostly agreed in the literature. Let us first comment Li’s structural analysis. In Li (2007, 27–29), example (2) has the structure of “S + P + O+ OC.” Semantically, this analysis means that the nominal group ren is the object that is caused or affected by the process of “rang,” and the event of “chong man nuan yi” is used to supply more information about the resulting state of ren. From what is expressed in example (2), we know that what the agent zhe yan se caused is not just a particular target ren, but a whole event. We can only ask questions like “what is caused by this color?” but not “what is caused to the people by this color?” In other words, this example means “someone or something causes an event,” not “someone or something causes someone.” Thus, Li’s analysis to some degree does not match semantic features to syntactic elements. Let us see Lv’s analysis of treating rang as a bifunctional verb. His analysis means that the nominal group ren is of two roles, i.e., it is both the Object of rang and the Subject of the following verb chong man. However, from what just mentioned above, ren chong man nuan yi forms an independent event, which means that ren should not be the Object of rang. We can say “ren xin zhong chong man nuan yi (people feel warm in the heart),” but cannot say “zhe yan se rang ren (this color makes people).” Therefore, Lv’s analysis of this example is also not based on meaning but to some degree on form. Compared to the two analyses just discussed above, the light verb analysis proposed by Shen, He, and Yang (2001) and others (He and Wang 2002; He 2004) is to some degree acceptable, since it treads the VP as a whole event. However, as we know from functional perspective rang does not behave like a light verb, since it still carries content meaning of “causation.”

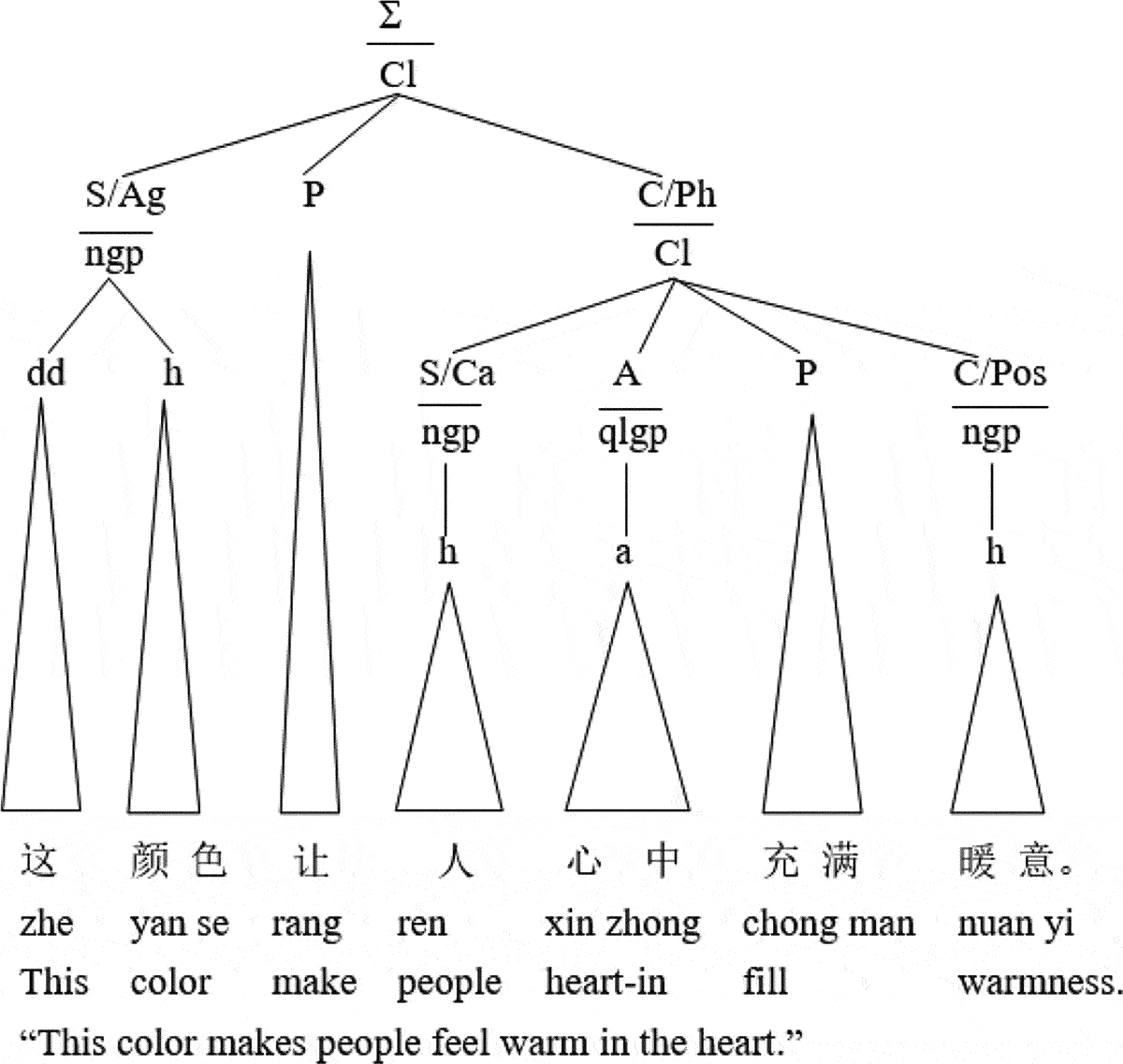

From the CG’s perspective, the so-called “causative construction” is a type of “influential process” in transitivity in the sense that “someone or something causes some event.” According to Fawcett (2011) and He (2014), an “influential process” is a Process that influences another Process, i.e., it is a “process-influencing” Process. It is “influential” in that it seriously affects our interpretation of the process in the dependent event, i.e., the process in the clause that fills the phenomenon. From the CG’s perspective, a causative verb often has the Process meaning of “someone causes something,” that is, a causative verb normally expects two PRs. One is the causer, and the other is the event that is caused by the causer. The CG assigns these two PRs as Agent and Phenomenon, respectively, where the Phenomenon is often expressed by an embedded clause. Thus, taking example (2) to illustrate, the syntax of rang clauses expressing “causation” can normally be represented in Figure 3 below.14

The analysis of rang clauses expressing “causation”.

As Figure 3 shows, we analyze the causative rang as a Predicator. The Predicator expects two PRs, where the PR of Agent is conflated with the Subject, and the PR of Phenomenon is conflated with the Complement. In this clause, the Subject is filled by a nominal group, which is composed of two elements: one is the deictic determiner expounded by the item zhe, and the other is the head expounded by the item yan se. The Complement is filled by another clause. This embedded clause is composed of four elements, where the Predicator expresses a relational Process, which expects two PRs: the Carrier and the Possessed. The Carrier is conflated with the Subject ren, and the Possessed is conflated with the Complement nuan yi.

Our analysis of the causative rang and its related syntactic structure is based on the meaning of rang. From our analysis, this kind of rang clause often consists of three syntactic elements, i.e., Subject, Predicator, and Complement. The nominal group following rang should not be regarded as the Complement of the matrix clause, but as the Subject of the embedded clause. This kind of analysis is thus more function-oriented and meaning-centered.

4.3. The syntax of rang clauses expressing “bei”

This passive “bei” usage of rang accounts for 12% in the samples chosen. As described in section 2, there are mainly three views proposed in the literature regarding the grammatical function of this passive rang: a preposition (Lv 1999: 462; Li 2001, 219), a sub-verb (Ding et al. 1999, 95) and an auxiliary verb (Wang 2002, 80). And because of the different views concerning it, different structures are assigned to this kind of rang clause. We agree with the first view that the passive rang is a preposition. We know that in Chinese language most prepositions are derived from verbs in the process of semantic change or grammaticalization. Since semantically this “bei” usage of rang is completely different from its original meaning of “concession” and “causation,” and its only function in the clause is to introduce the Agent of the action, this kind of usage should be categorized differently. However, we do not agree with the corresponding syntactic analysis of analyzing rang together with its following nominal group as an Adjunct, since this kind of analysis is completely based on form rather than function.

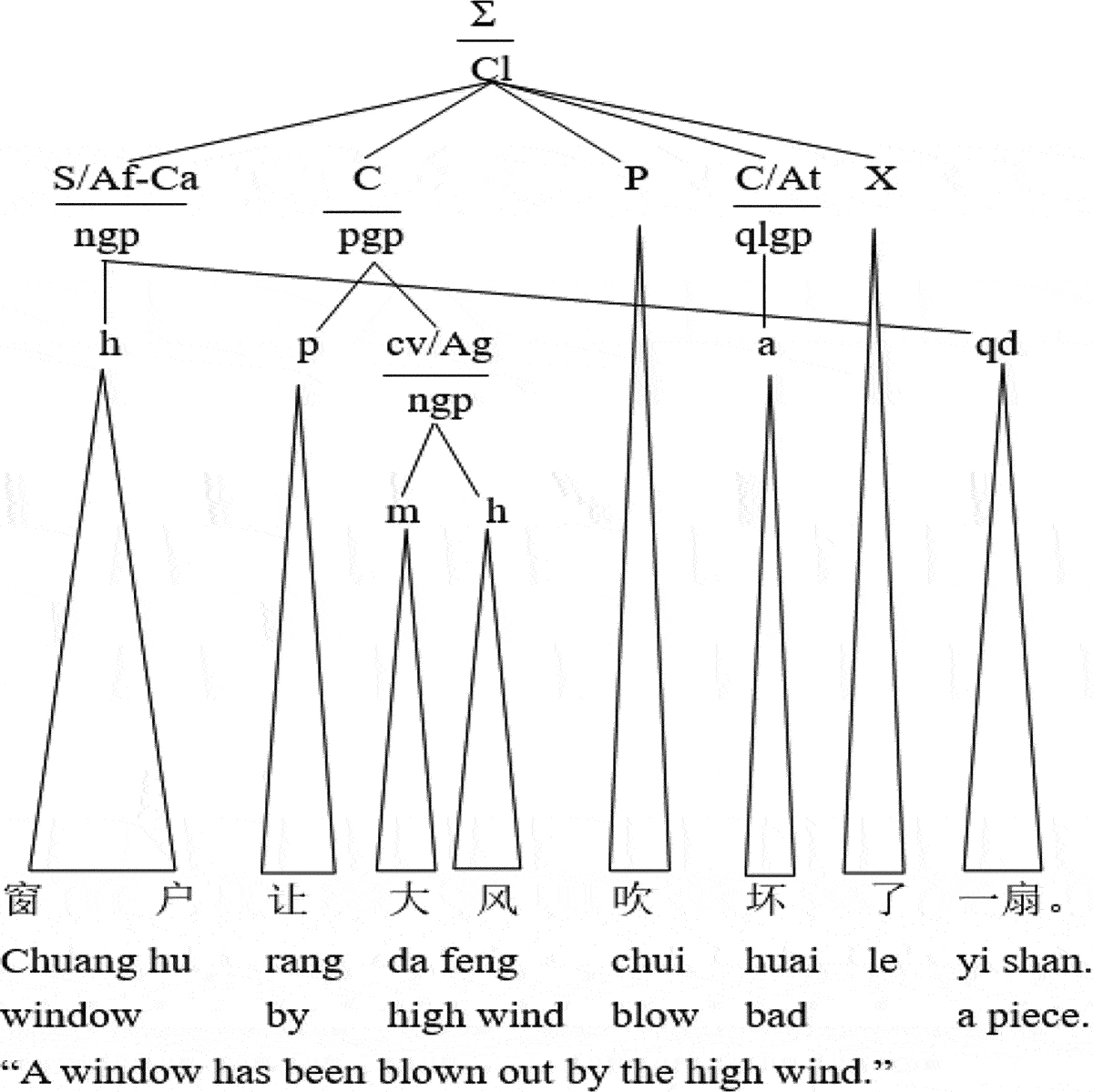

Let us take example (3) to illustrate. In the clause, semantically it is generally agreed that da feng plays the role of Agent. If we agree that it is the Agent, it means that it is a PR instead of a CR. Since a PR is typically conflated with Subject or Complement, we should not analyze rang da feng as an Adjunct. Thus, treating rang da feng as an Adjunct of the clause is a kind of form-centered analysis. In other words, although the PR of Agent predicted by the Process of “chui” is expressed as a prepositional group, it is not sufficiently strong to turn a PR into a CR, because rang has no meaning in its own right. It is merely the passive marker that is introduced automatically whenever a PR that typically occurs as the second (or third) PR in a clause is “promoted” to be the Subject Theme. Thus, rang is not there as the result of a choice in a system to have a meaning realized in rang, but merely as a by-product of the decision to make “chuang hu” the Subject Theme. According to the CG, the functional syntax of example (3) can be represented in Figure 4 below.15

The analysis of rang clauses expressing “bei”(1).

As we can see from Figure 4, we analyze chui as the Predicator. Semantically, this Predicator expresses a relational process, which expects three PRs. The Subject, which is filled by the nominal group yi shan chuan hu, is conflated with the PR of Affected-Carrier.16 The first Complement, which is filled by a prepositional group rang da feng, is conflated with the PR of Agent. More specifically, this Agent is conflated with the completive of the prepositional group. The second Complement, which is filled by a quality group huai, is conflated with the PR of Attribute. In this clause, le is an Auxiliary, marking past tense.

Our analysis of the prepositional group of rang da feng in this case as a Complement rather than an Adjunct have maintained the basic principles of “functional orientation” and “meaning centeredness” in functional description of the syntax. This is because the PR played by “da feng” in the event of “chui” is inherently unchanged, although it happens to be appeared in the form of a prepositional group. This tells us that not all prepositional groups are to be analyzed as Adjuncts. According to the CG’s criteria, only 32% of prepositional groups fill Adjunct, whereas 52% of them fill Complements (Fawcett 2008, 111).

One more point to mention, when discussing the connections and differences between rang and bei, Lv (1999, 463) and Li (2001, 219–223) argue that when bei is used before a solid word (content noun), it is a preposition, when it is used before a verb, it is a passive auxiliary verb. That is to say, bei in bei da (被打, be hit) and bei jie shou (被接受, be accepted) should be treated as auxiliary verbs. Lv claims that rang does not have this kind of usage. However, through careful examination of the three main Chinese corpora, we find that this usage of rang is indeed very infrequent, but there are some examples (see example (9)).

| (9) a. | 我 | 怎 | 会 | 让 | 抓住 | 的 | 呢? |

| wo | zen | hui | rang | zhua zhu | de | ne? | |

| I | how | can | by | capture | |||

| “How can I be captured?” | |||||||

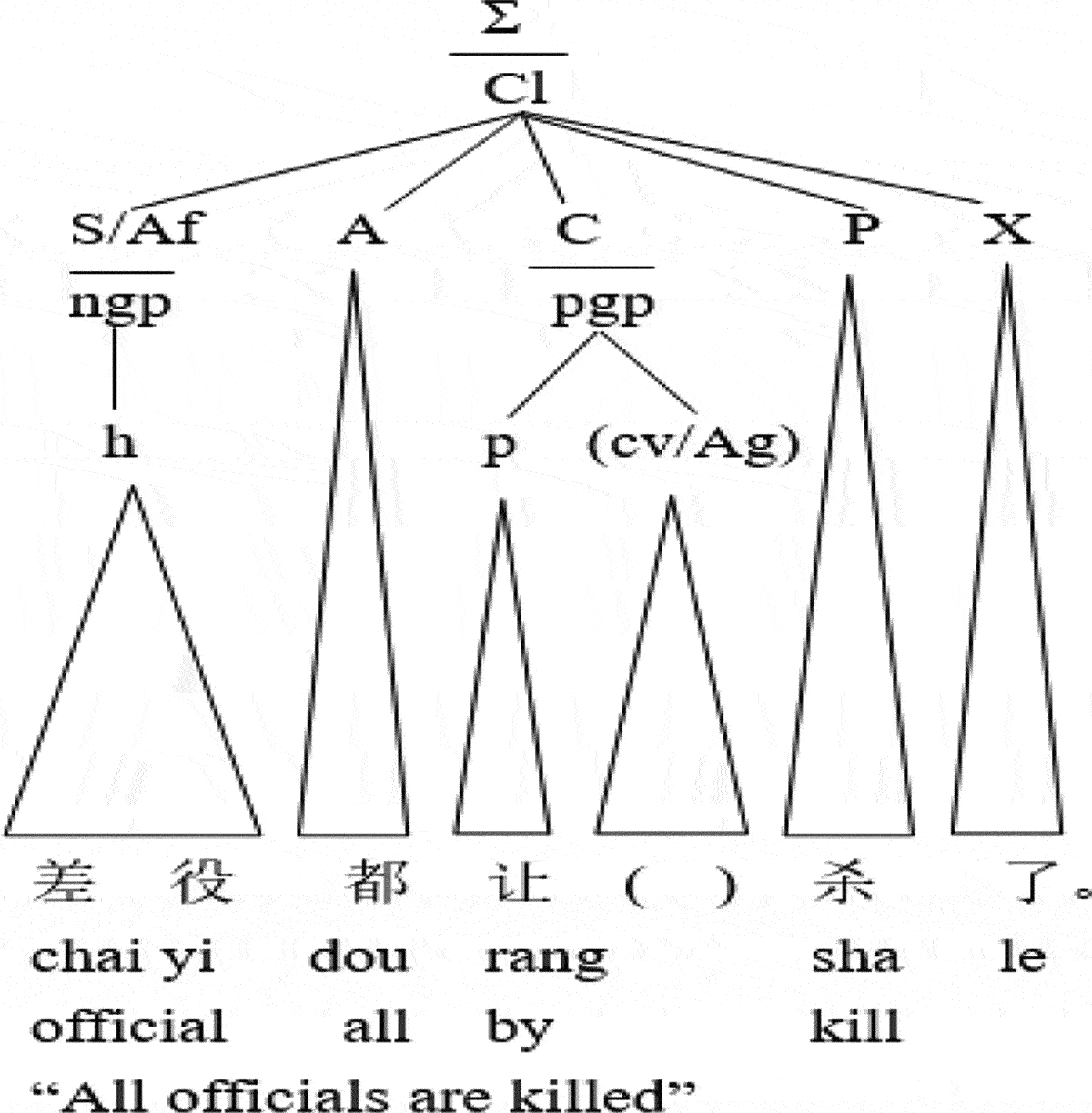

| b. | 差役 | 都 | 让 | 杀 | 了。 |

| chai yi | dou | rang | sha | le | |

| official | all | by | kill | ||

| “All officials are killed” | |||||

According to Lv’s (1999, 463) and Li’s (2001, 219–223) idea, rang in example (9) may have similar qualities and should be treated as passive auxiliary verbs. This kind of analysis is clearly influenced by the analysis of English passive constructions. In an English passive construction, it typically has the form of “be+V-ed,” where “be” is a passive Auxiliary. But in Chinese language, this passive “be” does not exist. Thus, from functional perspective, we argue that this kind of analysis is putting form before function. From example (3), we know that the function of rang in passive usage is to introduce the Agent of the action and this rang function has not been changed in example (9). Although the Agents of the actions in example (9) are not shown at the level of form, they are still recoverable from the context, that is, still semantically existed. This kind of linguistic phenomenon is well-known in passive constructions, where sometimes the doer of the action is omitted for different discourse purposes. From the CG’s perspective, this kind of omitted Agent is a kind of covert PR. Therefore, functionally rang in example (9) is no different from example (3), which should also be analyzed as a preposition. The only difference between them is that the Agent introduced by rang in example (9) is covert. Thus, taking example (9b) to illustrate, the syntax of rang clauses of this kind can be represented in Figure 5 below.

The analysis of rang clauses expressing “bei” (2).

As illustrated in Figure 5, in this clause, the Predicator expounded by the item sha expresses an Action Process, which expects two PRs, i.e., “someone kills someone or something.” The Subject, which is filled by a nominal group chai yi, is conflated with the role of Affected. The Complement is filled by a prepositional group, where the covert PR of Agent is conflated with a covert completive.17 In this clause, there are some other syntactic elements. The item dou expounds the Adjunct, and le expounds the Auxiliary marking past tense. Our analysis of rang in this case still as a preposition not an Auxiliary has maintained the principles established in the CG’s functional syntactic description, i.e., it is based on meaning and function, not on form.

4.4. The syntax of rang clauses expressing “wishes”

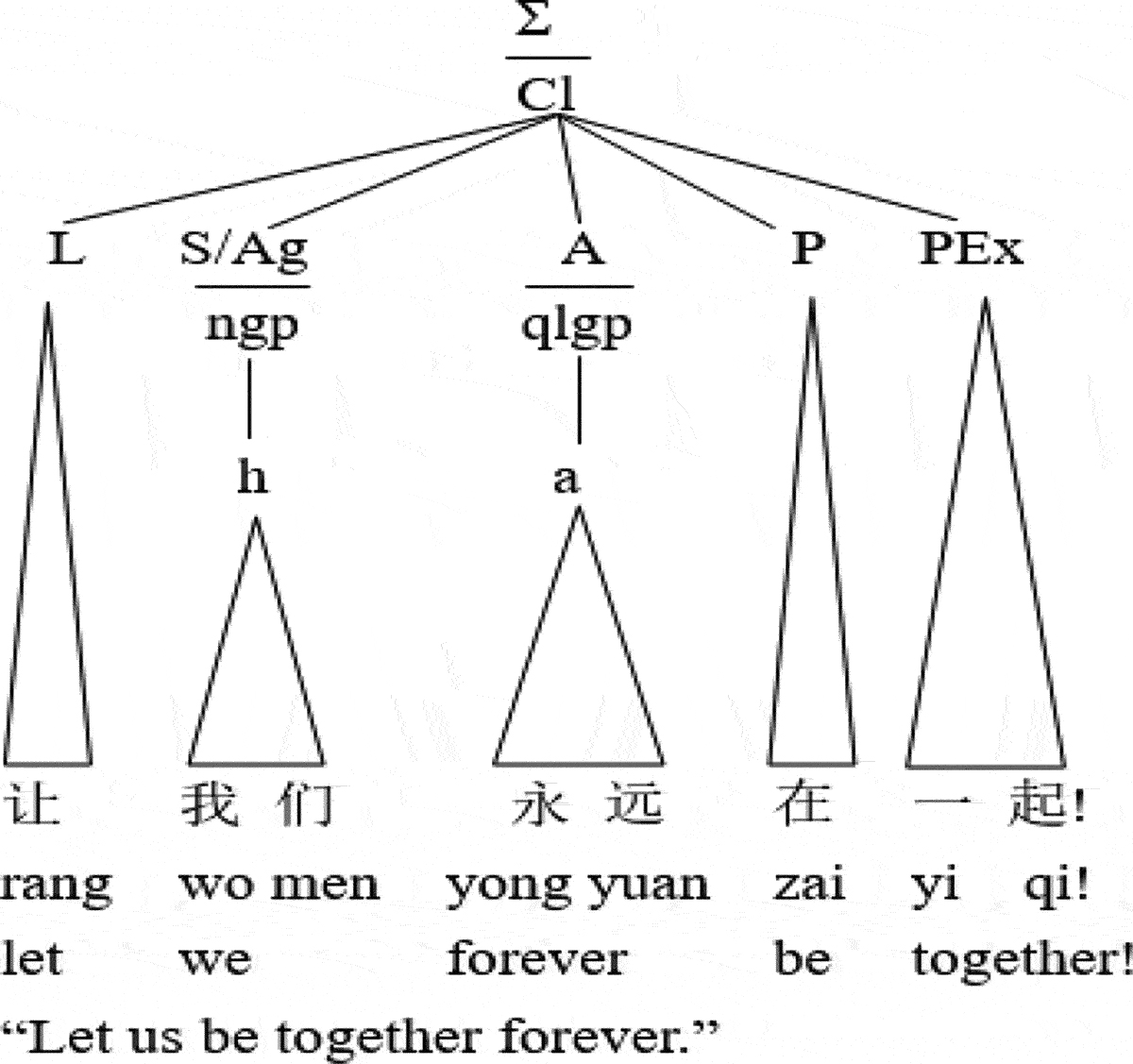

Here the meaning of “wishes” is also used in a broad sense, including meanings like “appealing,” “calling for” and “proposing.” Examples like Rang wo men tuan jie qi lai! (让我们团结起来!Let’s get united!), Rang wo zai shuo yi bian. (让我再说一遍, Let me repeat again!), and Rang ta qu ba! (让它去吧, Let it go.) are all included in this category. In our analysis of the corpus data, this kind of rang usage accounts for 8% of the corpus data. As example (4) shows, rang with this usage does not have the meaning of “concession” and “causation,” and does not have the meaning of “bei” either. As reviewed in section 2, this kind of rang usage has not attracted the attention from scholars in the Chinese linguistic field. Very little literature can be referred to. We only find that Lv (1999, 462) treats it as a verb and He et al. (2015, 58) regard it as a Let Element, but no explanations are given. Semantically, rang in this kind of clause has been deprived of lexical meaning, and is also different from the prepositional usage. Syntactically speaking, no syntactic elements can be inserted before rang, i.e., we cannot insert a Subject for rang in this kind of clause (*ni rang wo men yong yuan zai yi qi is ungrammatical). So, functionally, rang in this kind of clause does not behave like a verb or a preposition, which is only a Mood marker expressing “wishes.” There are similar issues in English (see example (10)).

(10) a. Let’s go.b. Let Ivy eat it!

In example (10), let is deprived of lexical meaning, and also used as a Mood marker of the clauses. Functionally, Fawcett (2008, 162) proposes that let in example (10) should not be analyzed as Operator or Main Verb; instead it should be regarded as an independent element of the clause, i.e., Let Element (abbreviated as L).18 We claim that the CG’s recognition of Let Element is theoretically significant, which has enriched the structural elements in realizing MOOD meaning. More importantly, this Let Element will solve many practical problems in functional syntactic description of some linguistic phenomenon as well. With this Let Element, the syntactic analysis for the so-called let-construction will be more compatible with the grammatical properties the construction displays, and the semantic functions to syntactic elements of the construction will be more systematically and consistently matched.

Adopting Fawcett’s (2008, 162) and Xiang and Liu (2018) analyses of “let’s clauses” in English, we claim that rang in this kind of usage should also be promoted to be the direct element of the clause, since it is uniquely used in modern mandarin Chinese and its only function is to be a Mood marker expressing “wishes.” Thus, the functional syntax of this kind of rang clause can be illustrated in Figure 6. below.

The analysis of rang clauses expressing “wishes”.

As is shown in Figure 6, we analyze rang in this clause as a direct element of the clause, i.e., Let Element. In this clause, the Predicator expounded by the item zai and Predicator Extension expounded by the item yi qi together express an Action Process, which expects one inherent PR, i.e., the Agent. The Subject, which is filled by an nominal group and expounded by the item wo men, is conflated with the PR of Agent. In this clause, yong yuan is a quality group, which fills the Adjunct of the clause. Based on the CG, our categorization of this new syntactic element of rang, i.e., Let Element, has enriched the structural elements in realizing MOOD meaning in Chinese and solved the practical problems of treating it as a verb in the literature. With this Let Element, the syntactic analysis is more compatible with the grammatical properties this usage of rang displays. Thus, the semantic function to syntactic element of this rang clause is more systematically and consistently matched.

5. Conclusion

This study investigates the rang clauses in modern mandarin Chinese within the framework of the Cardiff Grammar with the aim to solve the essential problem: what basic functional structures they represent. In the literature, two grammatical functions of rang have been generally recognized and various syntactic suggestions proposed. However, none seems to match the acknowledged semantic functions to their corresponding syntactic elements systematically. In SFL, the CG is an important model, which maintains two basic principles in its syntactic description: (1) the principle of function-orientation; and (2) the principle of meaning-centeredness. Adhering to the basic principles, we have identified four types rang clauses in the three main Chinese corpora, i.e., “concession” (46%), “causation” (34%), “bei” (12%), and “wishes” (8%). When rang is with the meaning of “concession,” it functions as a main verb, which expounds the Predicator of the clause, and the related syntactic structure may vary according to the situation it is used in or as it is collocated with other words. When it has the meaning of “causation,” it functions as a causative verb, which expounds the Predicator too. This kind of rang normally expresses an “influential process,” with the nominal group following rang as the Subject of the embedded clause. When rang is with the “bei” usage, it is a preposition, whose function is to introduce the Agent of the action. Syntactically it together with its following nominal group forms a prepositional group, which expounds the Complement of the clause rather than the Adjunct, since it is normally conflated with an inherent PR rather than a CR. Finally, when rang expresses “wishes,” its only function is being a Mood marker. Syntactically, we analyze it as the direct element of the clause, i.e., Let Element.

In our analysis of the clauses, we try to be systematic and consistent with the evidence from the linguistic data in the Chinese corpora. However, some other concerns related to the diverse uses of the clause (e.g., discourse purpose) have not been investigated in the present study (see example (11)).

| (11) | 我 | 让 | 你 | 哭! |

| wo | rang | ni | ku! | |

| I | let | you | cry! | |

| “I warn you that you do not cry!” | ||||

In example (11), the real meaning of the rang clause is actually quite distinct from its literal meaning. Some scholars (e.g., Xu 2007; Deng 2012) have investigated the semantic motivations of this kind of rang clauses, but no syntax has been offered. How to match the semantic functions and syntactic elements of this kind of rang clause functionally is still to be discussed. And to our knowledge, there is little literature available. As Halliday (1976, 26) points out, the internal organization of language is not arbitrary but embodies a positive reflection of the functions that language has evolved to serve in the life of social man. Much work remains to be done in exploring the functional variations, distributional patterns, and social-cultural connotations of rang clauses discussed above.

The present study is a functional syntactic analysis of rang clauses with the aim to match semantic functions to syntactic elements. The study indicates that some typical insights have been offered to the very nature of the clauses from the framework of the CG, which is function-oriented and meaning-centered. We cannot expect to understand the forms of language without considering the meanings of language and vice versa (Fawcett 2008, 37). Chinese is a language which is generally considered difficult by grammatical analysts. This difficulty is very often reflected in the fact that descriptions and explanations about certain aspects of the Chinese grammar do not comply with each other. This study highlights and makes explicit the principles informed by the CG in describing and modelling the Chinese language, giving privilege to function and meaning, and also matching semantic functions to syntactic elements. Ultimately, the present study will shed light on other controversial issues in Chinese language description especially for its functional syntax, and even on research fields for typological studies.

Funding source: Hunan Federation of Social Sciences

Award Identifier / Grant number: XSP20YBZ036

Funding statement: This work was supported by the Hunan Federation of Social Sciences [grant number XSP20YBZ036].

About the author

Dajun Xiang Ph.D., is an associate professor at the College of International Education, Jishou University, Hunan Province, China. He has published 1 academic book and 15 articles home and abroad. His main research interest includes systemic functional linguistics, discourse analysis and foreign language teaching.

Notes

- 1.

Except for example (2), all other examples in this section are from Lv (1999, 461–463). For our purpose of this study, tense, aspect, mood and other grammatical markers and measure words are just omitted in the line of word by word translation, since no equivalents can be found in English.

- 2.

Corpusonline is developed by State Language Commission; CCL refers to Center for Chinese Linguistics PKU, which is developed by PeKing University; BCC refers to BLCU Corpus Center, which is developed by Beijing Language and Culture University.

- 3.

Since opinions vary in the literature, we will only review some representative views proposed by some influential figures.

- 4.

Following the systemic tradition, the first letter of the functional element will be capitalized. We use “Predicator” rather than “main verb”, because in Chinese language the “Predicator” is not always realized by a main verb. Sometimes it can be realized by an adjective, even a clause (see He et al. 2015, 38–43). Also note that we use “Predicator”, not “Predicate”, because the latter term has been used in traditional grammar and formal grammar, where it is roughly equivalent to VP, or Verb Phrase.

- 5.

Key: ngp1 = nominal group 1; ngp2 = nominal group2; V = verb; ngp3 = nominal group 3. And for our purpose of the discussion, we will ignore the Adjunct xin zhong.

- 6.

Key: S = Subject; P = Predicator; O = Object; Oc = Object Complement; S1 = Subject 1; S2 = Subject 2; VP1 = Verb Phrase 1; VP2 = Verb Phrase 2; O2 = Object 2; C = Complement.

- 7.

The specific reasons for our claim will be elaborated in section 4 when giving our own functional analysis.

- 8.

Key: Cl = Clause; O = Operator; X = Auxiliary; M = Main verb; h = head; dd = deictic determiner.

- 9.

key: Oi = Indirect Object; Od = Direct Object.

- 10.

Traditional grammars make a distinction between “Objects” and “Complements” and, within “Objects”, between “Direct Objects” and “Indirect Objects”. Yet in SFL, they are all treated as “Complements”, since SFL uses an even fuller and more discriminating set of functionally motivated categories, i.e. the set of types of Participant Role, to account for these distinctions.

- 11.

In the CG, a PR is typically conflated with Subject or Complement, and a CR is typically conflated with Adjunct (Fawcett 2008, 138).

- 12.

key: ξ = sentence; Ag = Agent; Af = Affected; qtgp = quality group; am = amount.

- 13.

For more information on the CG’s transitivity system and how the PRs are analyzed, see Fawcett (2011).

- 14.

key: Ca = Carrier; a = apex; Pos = Possessed; qlgp = quality group.

- 15.

Key: pgp = prepositional group; p = preposition; cv = completive; m = modifier; qd = quantifying determiner; Af-Ca = Affected-Carrier; At = Attribute.

- 16.

Note that although the head of the nominal group chuang hu and its quantifying determiner yi shan are discontinuous at the form level, this does not affect the fact that they are semantically an unseparated unity. Also note here, Affected-Carrier means a compound PR, which is both the Affected and the Carrier.

- 17.

According to the CG, the covert element is represented in round brackets syntactically.

- 18.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported.

References

DaviesE.1986. The English Imperative. London: Croom Helm.Suche in Google Scholar

DengC. L.2012. “‘Jiao/rang’ De Zhuguanxing Yongfa Ji Kuozhan Jizhi [The Subjective Usage of ‘Jiao/rang’ and Expansion Mechanism].” Language Teaching and Linguistics Studies1: 60–67.Suche in Google Scholar

DingS. S., S. X.Lv, R.Li., D. X.Sun, X. C.Guan, J.Fu., S. Z.Huang, and Z. W.Chen. 1999. Xiandai Hanyu Yufa Jianghua [Lectures on Modern Chinese Grammar]. Beijing: Commercial Press.Suche in Google Scholar

FanX.2000. Lun “Zhishi” Jiegou [On “Causative” Construction]. Beijing: Commercial Press.Suche in Google Scholar

FawcettR. P.1980. Cognitive Linguistics and Social Interaction: Towards an Integrated Model of a Systemic Functional Grammar and the Other Components of a Communicating Mind. Heidelberg: Julius Groos.Suche in Google Scholar

FawcettR. P.2000. A Theory of Syntax for Systemic Functional Linguistics. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/cilt.206Suche in Google Scholar

FawcettR. P.2008. Invitation to Systemic Functional Linguistics through the Cardiff Grammar: An Extension and Simplification of Halliday’s Systemic Functional Grammar. London: Equinox.Suche in Google Scholar

FawcettR. P.2011. “Problems and Solutions in Identifying Processes and Participant Roles in Discourse Analysis Part 1: Introduction to a Systematic Procedure for Identifying Processes and Participant Roles.” In Annual Review of Functional Linguistics, edited by G. W.Huang and C. G.Chang, 34–87. Beijing: Higher Education Press.Suche in Google Scholar

FawcettR. P., G. H.Tucker, and Y. Q.Lin. 1993. “The Role of Realization in Realization: How a Systemic Grammar Works.” In From Planning to Realization in Natural Language Generation, edited by H.Horacek and M.Zock, 114–186. London: Pinter.Suche in Google Scholar

HallidayM. A. K.1976. “Functions and Universals.” In Halliday: System and Function in Language, edited by G.Kress, 26–35. London: Oxford University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

HallidayM. A. K.2006. “Systemic Theory.” In Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics, edited by K.Brown, 443–447. 2nd ed. London: Elsevier.10.1016/B0-08-044854-2/02051-4Suche in Google Scholar

HallidayM. A. K.2014. Halliday’s Introduction to Functional Grammar. 4th ed. London and New York: Routledge.10.4324/9780203783771Suche in Google Scholar

HeW.2014. “‘Bi-functional Constituent Constructions’ in Modern Mandarin Chinese: A Cardiff Grammar Approach.” Language Sciences42: 43–59.10.1016/j.langsci.2013.12.001Suche in Google Scholar

HeW., S. W.Gao., B. B.Jia., J.Zhang, and J. N.Qiu. 2015. Functional Syntactic Analysis of Chinese. Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press.Suche in Google Scholar

HeY. J.2004. “Lun Shiyijv De Leixingxue Tezheng [On the Typological Features of Causatives].” Linguistic Sciences1: 29–42.Suche in Google Scholar

HeY. J., and L. L.Wang. 2002. “Lun Hanyu Shiyijv [On Chinese Causatives].” Chinese Language Learning4: 1–9.Suche in Google Scholar

HuD. M.2009. “‘Shuirang’ Wenjv Yanjiu [A Study of ‘Shuirang’ Questions].” Chinese Teaching in the World2: 191–201.Suche in Google Scholar

HuangB. R., and X. D.Liao. 2002. Xiandai Hanyu [Modern Chinese]. Beijing: Higher Education Press.Suche in Google Scholar

LiJ. X.2001. Li Jinxi Xuanji [The Collected Works of Li Jinxi]. Changchun: Northeast University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

LiJ. X.2007. Xinzhu Guoyu Wenfa [Newly Compiled National Language Grammar]. Changsha: Hunan Education Press.Suche in Google Scholar

LiL. D.1986. Xiandai Hanyu Jvxing [Sentence Patterns in Modern Chinese]. Beijing: Commercial Press.Suche in Google Scholar

LvS. X.1999. Xiandai Hanyu Babaici [Eighty Hundred Words in Modern Chinese]. Beijing: Commercial Press.Suche in Google Scholar

MatthiessenC. M. I. M.1995. Lexicogrammatical Cartography: English Systems. Tokyo: International Language Sciences Publishers.Suche in Google Scholar

QuirkR., S.Greenbaum., G.Leech, and J.Svartvik. 1985. A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. London: Longman.Suche in Google Scholar

ShenY., Y. J.He, and G.Yang. 2001. Shengcheng Yufa Lilun Yu Hanyu Yufa Yanjiu [Theory of Generative Grammar and Chinese Grammar Study]. Harbin: Helongjiang Education Press.Suche in Google Scholar

TuckerG. H.1998. The Lexicogrammar of Adjectives: A Systemic Functional Approach to Lexis. London: Cassell Academic.Suche in Google Scholar

WangL.2002. Wang Li Xuanji [The Collected Works of Wang Li]. Changchun: Northeast University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

WangL. J., J. M.Lu., H. Q.Fu., Z.Ma, and P. C.Su. 2006. Xiandai Hanyu [Modern Chinese]. Beijing: Commercial Press.Suche in Google Scholar

XiangD. J.2016. “The Syntax of Let Construction in English: A Systemic Functional Approach.” International Journal of Language and Linguistics3: 89–95.10.11648/j.ijll.20160403.11Suche in Google Scholar

XiangD. J., and C. Y.Liu. 2018. “The Semantics of MOOD and the Syntax of the Let’s-construction in English: A Corpus-based Cardiff Grammar Approach.” Australian Journal of Linguistics4: 549–585.Suche in Google Scholar

XuW. D.2007. “Zhaoyuanhua Zhong Biao ‘Xiaoji Jinzhi’ De ‘Rang’zijv [The ‘Negative and Forbidding’ Rang Clauses in Zhaoyuan Dialect].” Studies of the Chinese Language4: 359–363.Suche in Google Scholar

ZhangJ.1980. Xinbian Xiandai Hanyu [Newly Compiled Modern Chinese]. Shanghai: Shanghai Education Press.Suche in Google Scholar

ZhangJ. Y.2005. “‘Rang’ Yufahua Guochengde Gean Fenxi [A Case Study of the Grammaticalization Process of ‘Rang’].” Overseas Chinese Education4: 22–28.Suche in Google Scholar

ZhuC. Q.2002. Xiandai Hanyu Yufa Jiaocheng [A Course for Modern Chinese Grammar]. Beijing: University of International Business and Economics Press.Suche in Google Scholar

ZhuD. X.1999. Zhu Dexi Wenji [The Collected Works of Zhu Dexi]. Beijing: Commercial Press.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2020 Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Article

- Full realization principle for the identification of ideational grammatical metaphor: nominalization as example

- Exploring lexical bundles in recent published papers in the field of applied linguistics

- Rang clauses in modern mandarin Chinese: a Cardiff Grammar approach

- Human-nature relationships in experiential meaning: transitivity system of Chinese from an ecolinguistic perspective

- Book Review

- English as a Lingua Franca in Japan: towards multilingual practices

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Article

- Full realization principle for the identification of ideational grammatical metaphor: nominalization as example

- Exploring lexical bundles in recent published papers in the field of applied linguistics

- Rang clauses in modern mandarin Chinese: a Cardiff Grammar approach

- Human-nature relationships in experiential meaning: transitivity system of Chinese from an ecolinguistic perspective

- Book Review

- English as a Lingua Franca in Japan: towards multilingual practices