The flesh and the bones of cohesive devices: towards a comprehensive model

-

Emad A. S. Abu-Ayyash

Emad A. S. Abu-Ayyash John McKenny

ABSTRACT

Building on a 1976 model of cohesive devices, this article probes the literature on these linguistic tools with the aim of generating a comprehensive model of cohesion that can be used as an instrument for textual analysis across different text types. This article addresses two main questions: (1) what are the linguistic tools that can be incorporated into the 1976-model of cohesive devices in the creation of an operational model? and (2) what would such a comprehensive model of cohesive devices look like? The contributions of various scholars are examined to determine which elements might be considered as cohesive devices, apart from those introduced in the 1976 model. For almost all the categories within the lexico-grammar taxonomy presented in 1976, more elements are found that can play various cohesive roles in texts and that can be integrated into the 1976 model to form a more all-embracing one. To further illustrate this claim, examples from English and Arabic are used to present a new model of analysis applicable to various languages.

1. Transcription

The following transcription system will be used throughout the study.

a. Consonants

| Arabic letter | Transliteration | Articulatory features |

|---|---|---|

| ء | ’ | Glottal, voiceless stop |

| ب | b | Bilabial, voiced stop |

| ت | t | Alveolar, voiceless stop |

| ث | th | Interdental, voiceless fricative |

| ج | j | Alveo-palatal affricate |

| ح | H | Pharyngeal, voiceless fricative |

| خ | kh | Uvular, voiceless fricative |

| د | d | Alveolar. voiced stop |

| ذ | dh | Interdental, voiced fricative |

| ر | r | Interdental tril |

| ز | z | Alveolar, voiced fricative |

| س | s | Alveolar, voiceless fricative |

| ش | sh | Alveo-palatal, voiceless fricative |

| ص | S | Alveolar, voiceless fricative |

| ض | D | Alveolar, voiceless fricative |

| ط | T | Alveolar, voiceless fricative |

| ظ | Z | Interdental, voiced fricative |

| ع | ` | Pharyngeal, voiced fricative |

| غ | gh | Uvular, voiced fricative |

| ف | f | Labiodental, voiceless fricative |

| ق | q | Uvular, voiceless stop |

| ك | k | Velar, voiceless stop |

| ل | l | Interdental, lateral |

| م | m | Bilabial, nasal |

| ن | n | Interdental, nasal |

| ه | h | Glottal, voiceless fricative |

| و | w | Bilabial, semivowel |

| ي | y | Alveo-palatal, semivowel |

| ة | h,t | Glottal, voiceless fricative OR Alveolar, voiceless stop |

b. Vowels

| Vowels | Symbols | Articulatory feature | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short | ــــــَ | a | Low, central |

| ــــــُ | u | High; back | |

| ــــــِ | i | High; front | |

| Long | ا | aa | Low, central |

| و | uu | High, back | |

| ي | ii | High, front |

2. Introduction

Since its inception, Halliday and Hasan’s 1976 model of cohesive devices has brought to the fore vigorous interest in the relations that exist among the various parts of a text. The model has been considered a seminal tool of discourse and text analysis, and has been used in a huge body of research in English and Arabic (e.g., Abdul Rahman 2013; Ali 2016; Ashouri and Ashouri 2016; Crossley, Salsbury, and McNamara 2010; Granger and Tyson 2007; Karadeniz 2017; Leo 2012; Mohamed and Mudawi 2015; Rasheed and Abid 2016; Rostami, Gholami, and Piri 2016), and is viewed as the model for any linguistic analysis that goes beyond the sentence level. It is worth pointing out that the 1976 model has been applied on a number of languages, including German (Krein-Kühle 2002), Portuguese (Silveira 2008), and Persian (Parazaran 2015). On a cautious note, though, the mainstream research preferred to use the English version of the model, probably to guarantee more readerships, given that English has undeniably grown as a lingua franca across the globe. To its credit, Halliday and Hasan (1976) model in textual analysis has been considered the most comprehensive account of cohesive devices (Moreno 2003; Xi 2010). Chen (2008) adds that the model provides a well-developed taxonomy of cohesion. In accord with these views, Baker (2011) argues that the 1976 model is “the best known and most detailed model of cohesion available” (180).

By and large, cohesion has been classified into two major categories: grammatical cohesion and lexical cohesion. The reason behind this classification is that “cohesion is expressed partly through the grammar and partly through the vocabulary” (Halliday and Hasan 1976, 5). Grammatical cohesion is subdivided into four textual ties, which are reference, substitution, ellipsis, and conjunctions, whereas lexical cohesion involves vocabulary ties, such as reiteration and collocation. While the two main categories, grammatical and lexical cohesion, have remained unchanged since they were introduced in 1976, the subcategories, which include reference, substitution, ellipsis, conjunctions, repetition, and collocation, have undergone several changes and adaptations. These modifications to the original model of 1976 have been employed to create the instrument of the present paper and will be discussed thoroughly in the conceptual framework section.

The choice of cohesive devices as a linguistic analysis tool to investigate certain types of texts can be made for a variety of reasons. Firstly, it is cohesive devices that make a text (Bahaziq 2016) and therefore can be used as a tool to determine whether a sequence of sentences can or cannot be described as a text (Cook 2010; Hatch 1992; Thornbury 2005). Put differently, cohesive devices have the potent effect of maintaining text unity, thus creating the distinction between texts as unified wholes and disconnected sequences of sentences (Tanskanen 2006). Secondly, through cohesive devices, writers establish the logical organization and structure of information in all kinds of texts (Goldman and Murray 1989; Kuo 1995). Thirdly, cohesive devices are the only non-structural component of texts, and therefore constitute the sole instrument for non-structural, textual analysis (Halliday and Hasan 1976). Finally, cohesive devices are a fundamental linguistic tool that producers of texts use to help receivers decode, interpret, or understand their messages (Brown and Yule 1983).

The utilization of these devices, according to Halliday and Hasan (1976), will not only lead to but is also the only source of texture, the property of being a text. According to them, whenever the interpretation of a linguistic element is dependent on another, cohesion occurs. This dependency relationship is referred to as a tie (Halliday and Hasan 1976). A tie, therefore, refers to a single occurrence of cohesion, whether the two linguistic elements of the cohesive tie have the same referent or not. Consider the following examples where instances of cohesive ties are bold-faced:

| [1] | | John achieved the highest score in the test. He must have studied very well. |

| [2] | | John’s wife is a teacher at a community school. My wife is a nurse there. |

In [1], He refers to John, and both are the same person, and in [2], wife is repeated, yet the referent is different. In both instances, though, a cohesive tie holds, reference in the former and lexical repetition in the second.

Although four decades have passed now since the 1976-model of cohesion was introduced, the model has never gone out of date. On the contrary, rarely does one find an analysis of cohesive devices that does not refer to Halliday and Hasan (1976) model of cohesion, and indeed many studies rely on this same model right up to the present day. However, this model is not immutable. Therefore, acknowledging the seminal contribution of Halliday and Hasan (1976) to text analysis, this paper investigates whether their model can be adapted to accommodate other contributions, if any, that could contribute further to the linguistic analysis of cohesion.

3. Purpose of the study

This paper aims to build a comprehensive model of cohesion that can be used as a discourse analysis instrument in a wide variety of texts. To do so, the present study attempts to answer the following questions:

Based on the conceptual framework introduced in the present paper, what are the linguistic tools, if any, that can be incorporated into the 1976-model of cohesive devices?

What would a comprehensive model of cohesive devices look like?

4. Theoretical background

The linguistic analysis of cohesive devices is essentially rooted in Systemic Functional Grammar (SFG) Theory (Halliday 1978), which suggests five ordering principles of a language: Structure, system, stratification, instantiation, and metafunction. The following subsections explain these five principles and juxtapose the key ones with other grammar theories in order to gain more insight into how SFG underpins the analysis of this paper.

4.1. The principle of structure

Generally, structure is the concept that refers to the syntagmatic order of linguistic constituents (Fromkin, Rodman, and Hyams 2007). According to SFG, a syntagm is a mere “organic configuration of elements” that gives very little about meaning (Halliday and Matthiessen 2014, 39). The following is an example of a syntagm and how it works as far as parts and functions are concerned:

| [3] | |Syntagm: | the | famous | novelist | of | Algeria |

| |Grammatical class: | determiner | adjective | noun | preposition | noun | |

| |Function: | deictic | post-deictic | person | qualifier | ||

According to SFG, a syntagm is important because it presents an organic configuration in terms of grammatical classes and functions. Superficially, what SFG proposes about structure and its function does not differ substantially from what other grammar theories suggest. For example, Transformational-Generative Grammar (TGG) also identifies the organic elements of syntagms via phrase structural rules (Chomsky 1957). The grammatical classes of A car hit the man would be represented in the following way:

| [4] | |S |NP + VP |NP + V + NP |Det + N + V + Det + N |A car hit the man |

SFG and TGG also agree in that the layers of a syntagm are organized by the relationship “is part of”. In this respect, a morpheme is part of a word; a word is part of a phrase; a phrase is part of a clause.

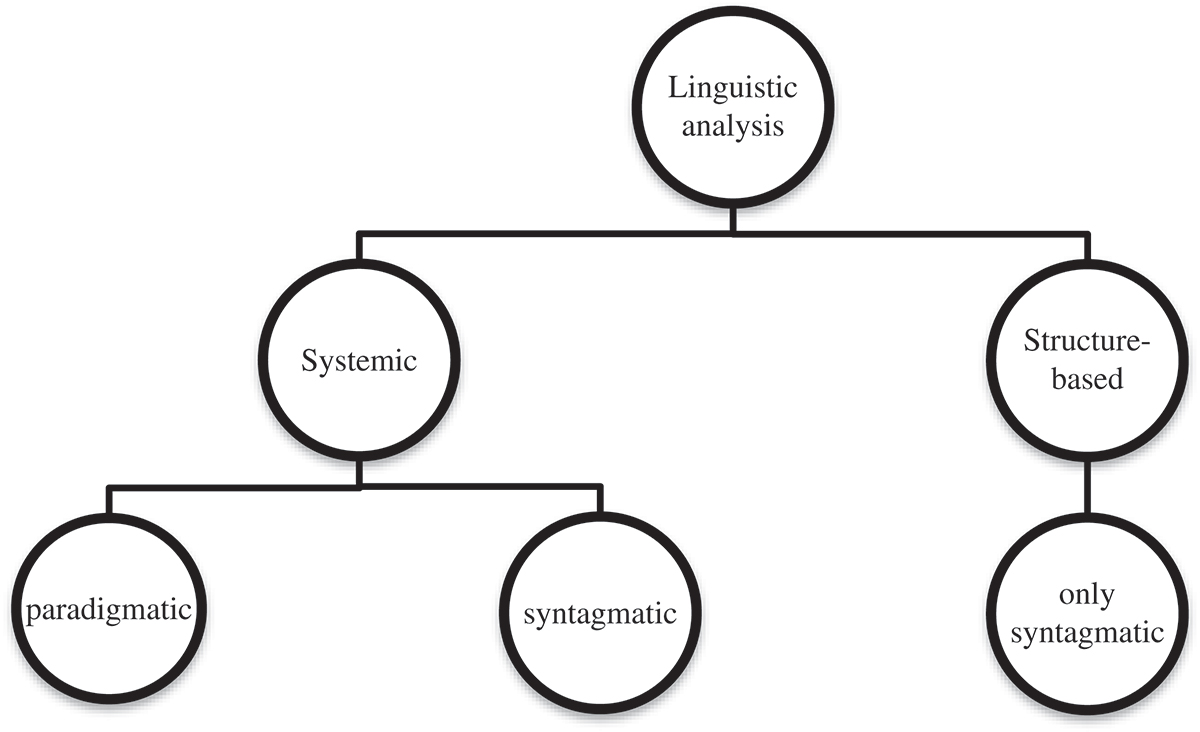

Emphasis on syntagms in linguistic analysis was shared by other grammar theories, such as Word Grammar (WG), which holds that information about and dependencies between individual words should be the basic component of any structural analysis (Hudson 2007). Despite the similarity between SFG, TGG, and WG in acknowledging the significance of structure, these theories are very different in the way they look at the function of structure. While TGG and WG propose that linguistic analysis should not exceed the syntagm, SFG does not consider structure as the core of linguistic analysis and suggests that analysis should transcend the sentence and consider the “system” (Halliday and Matthiessen 2014).

4.2. The principle of system

The principle of system can be considered the hallmark of SFG. The theory defines system as “the paradigmatic ordering in language” (Halliday and Matthiessen 2014, 22). Unlike structure, system involves ordering at the vertical axis rather than the horizontal. What matters in system is what could go instead of what, compared to what goes together with what, the principal ordering pattern of structure (Martin 2004). Holding the relation of what could go instead of what, system is about choices made in language and is one aspect of the meaning potential of language (Halliday and Hasan 1976; Halliday and Matthiessen 2014; Menfredi 2011). As noted earlier, SFG holds that linguistic analysis must go beyond the sentence (Halliday and Hasan 1976; Johnstone 2002; Jordan 2004; Thompson and Klerk 2002). Following from this, text and its evolvement from one clause to another is one of the main foci of SFG (Gee and Handford 2011).

Although it is occasionally, but not necessarily rightly, claimed that linguistic analysis done under the umbrella of SFG has been predominantly syntagmatic (Bateman 2008), SFG maintains that both syntagmatic and paradigmatic relations are important (Martin 2014). Halliday (2009) stresses that considering paradigmatic relations “does not mean that system is regarded as more important than structure…; it means that system is taken as the more abstract category, with structure as deriving from it” (64). At odds with SFG in this regard are a number of grammar theories which consider the sentence as the major unit – sometimes even the largest constituent (Greenbaum and Nelson 2002; Jackendoff 2002) – of linguistic analysis, and that linguistic analysis should stop there. TGG, for example, asserts that formal analysis is not possible beyond the sentence level (Coulthard 2014). In essence, this syntagm-and/or-paradigm variation stems from a deeper theoretical divide between syntax-only theories, represented by structure-oriented analysis of language on the one hand, and semantics-driven theories represented by structure- and system-based linguistic analysis on the other hand. To illustrate, theories that are driven by syntax, e.g., TGG, focus on structural, or syntagmatic configurations of language as the sole core of linguistic analysis (Carnie 2014; Hall 2005). At the centre of TGG lies a fundamental principle: “The notion ‘grammatical’ cannot be identified with ‘meaningful’ or ‘significant’ in any semantic level… [and] any search for a semantically based definition of ‘grammaticalness’ will be futile” (Chomsky 1957, 15). Although Chomsky’s 1981 Government and Binding (GB) Theory addressed lexical items as the atomic units of syntax (Black 1999), syntax was still the focus of linguistic analysis. SFG, which considers both syntagmatic and paradigmatic relations in texts, is driven by semantics (Stubbs 2014), and, therefore, links grammar to meaning making as configured through systems and networks of horizontal and vertical relations among various text elements. Figure 1 summarizes the above discussion about the syntagm–paradigm theoretical divide.

Systemic vs. structural linguistic analysis.

At the borderline of the syntagm/paradigm divide is the Applicative Universal Grammar Theory, which defines sentence structure as the network of syntagmatic and paradigmatic relations between sentence parts and all other expressions that can be substituted for these parts (Shaumyan 1987; Shaumyan and Segond 1994). This theoretical stand has found its way to the Arabic context as syntax and semantics were occasionally described in terms of structure and word order (Bahloul 2008; Holes 2004). This view of structure as encompassing both horizontal and vertical relations is an oversimplification of the broad divide between syntagm and paradigm on the one hand, and the underpinning distinction between syntactic orientation and semantic orientation to language on the other hand. SFG makes clear distinction between structure (sentence level) and system (text level) (Gee and Handford 2011). In order to put this within its wider context in the theory, SFG introduced the third principle, which is stratification.

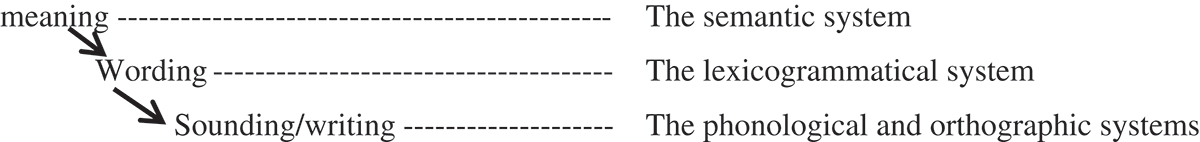

4.3. The principle of stratification

According to SFG, “language can be explained as a multiple coding system comprising three levels of coding, or strata” (Halliday and Hasan 1976). The three strata are (1) semantics, which is realized by (2) the lexico-grammar, which is realized by (3) sounding/writing. Figure 2 below outlines the three strata according to SFG as adapted from Halliday and Hasan (1976).

The three strata of language according to SFG.

According to SFG, semantics mediate between the context and the lexico-grammar (Teich 1999). Of particular interest to this paper is the second stratum, which is the lexico-grammar. One of the main propositions of SFG is that it considers lexis and grammar as the two ends of a single continuum, rather than two different entities. The only difference between vocabulary and grammar according to SFG is that the former expresses specific meanings and the latter expresses more general meanings (Halliday and Hasan 1976; Halliday and Matthiessen 2014). A lexicogrammar stratum can be presented in the form of a cline similar to the one in Figure 3.

Lexicogrammar cline.

As far as cohesive devices are concerned, they are distributed across the lexico-grammar cline, where reference, ellipsis, and substitution are grammatical; reiteration and collocation are lexical; and conjunctions somewhere between the two. These devices, which are part of the lexico-grammar stratum, play major roles in texts’ unity and organization. However, when considering the organization of language itself, the principle of instantiation has to be explained.

4.4. The principle of instantiation

According to SFG, any text is an instance of some underlying system. If someone does not know the system of the Arabic language, for example, a text written in that language may not have meaning to him/her. Halliday and Matthiessen (2014) compare system and text to climate and weather, respectively. Text is similar to weather in that it goes around us all the time affecting our daily lives, whereas system is analogous with climate since system underlies the impact of text. Halliday and Matthiessen (2014) state that “the relationship between system and text is a cline – the cline of instantiation” (27). The authors explain that while system represents the overall potential of language, text is the particular instance. Between the two there are intermediate patterns. A single text, or an instance of system, can be initially studied and then other texts that share certain criteria with it examined, describing this within text type. Looking at text type is seen as a movement along the instantiation cline from the instance pole to the system pole (Halliday and Matthiessen 2014). While the principle of instantiation is concerned with organization of language, the fifth principle of SFG is linked to the three metafunctions of language.

4.5. The principle of metafunction

SFG asserts that one primary function of language is to make sense of experiences, therefore construing human experience. Hence, language names and categorizes things. Language also develops categories into further taxonomies. For example, building is a category that includes houses, towers, schools, cottages, etc. Animal is another category that includes camels, lions, and so on. In Arabic, taxonomies can be categories of their own as well because they can be broken down into further taxonomies. For example, جمل/jamal/, meaning camel, which is a taxonomy of حيوان/Hayawaan/, meaning animal, can become a category in its own right as there are approximately a 100 sub-types for this animal in Arabic. Table 1 provides some examples of camel taxonomies in Arabic.

Camel categories/taxonomies in Arabic.

| The category/taxonomy of camel in Arabic | |

|---|---|

| Arabic name | Meaning in English |

| جمل/jamal/ | Male camel |

| ناقة/naaqah/ | Female camel |

| كوماء/kawmaa’/ | Camels with long humps |

| الغيهب/alghayhab/ | Camel with dark colour |

| المِغص/almighS/ | White camels |

According to SFG, the language function that involves construing human experience is called ideational. The second function of language is the interpersonal, which involves “enacting our personal and social relationships with the other people around us” (Halliday and Matthiessen 2014, 29). This function of language entails that a clause of grammar exceeds being a representation of some process as it also entails some kind of function, such as offering, expressing opinion, and informing, to name but a few. Akin to this view of the interpersonal metafunction of language, Bonyadi (2011) and Fowler (2003) maintain that language does not allow its users to say something without conveying some kind of attitude, or point of view towards what is being said.

The above two functions, construing experiences and enacting interpersonal relationships, call for a facilitating function, hence the textual function of language. This function enables the other two to construct sequences of discourse, organize the flow of ideas, and create cohesion (Halliday and Matthiessen 2014). The textual function of language is divided into structural, or syntagmatic, and non-structural, or paradigmatic, components. Cohesive devices, the focus of the present paper, are pinned into the non-structural component of the textual function of language as illustrated by SFG. In a nutshell, Halliday and Hasan (1976) explain that the ideational component of language expresses content, whether it is experiential or logical, that the interpersonal component represents the speaker’s attitudes and judgments, and that the textual component represents the forming of the text in the linguistic system. The time is probably ripe at this stage to illustrate the conceptual framework of cohesion, which will be utilized to build the new model of cohesion.

4.6. Conceptual framework of cohesion

The conceptual framework of the studies reviewed in this paper serves two main purposes. Firstly, it explains the concepts that constitute the core elements of the comprehensive model of analysis suggested by this study. Secondly, it highlights the developments and adaptations that have taken place since the 1976 model of cohesive devices was first introduced. According to Halliday and Hasan (1976), cohesion “…refers to relations of meaning that exist within the text, and that define it as a text” (4). The following conceptual framework of cohesive devices is primarily discussed in light of Halliday and Hasan (1976) lexico-grammatical model. The authors have identified five main categories of cohesion that can be grouped under grammatical cohesion (reference, substitution, and ellipsis), lexical cohesion (reiteration and collocation) and partly grammatical, partly lexical cohesion (conjunctions). The following review discusses all these categories and all the adaptations and additions that they have undergone since 1976.

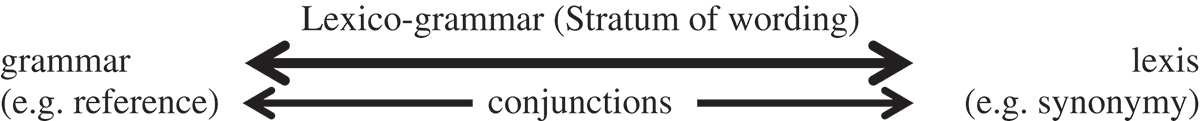

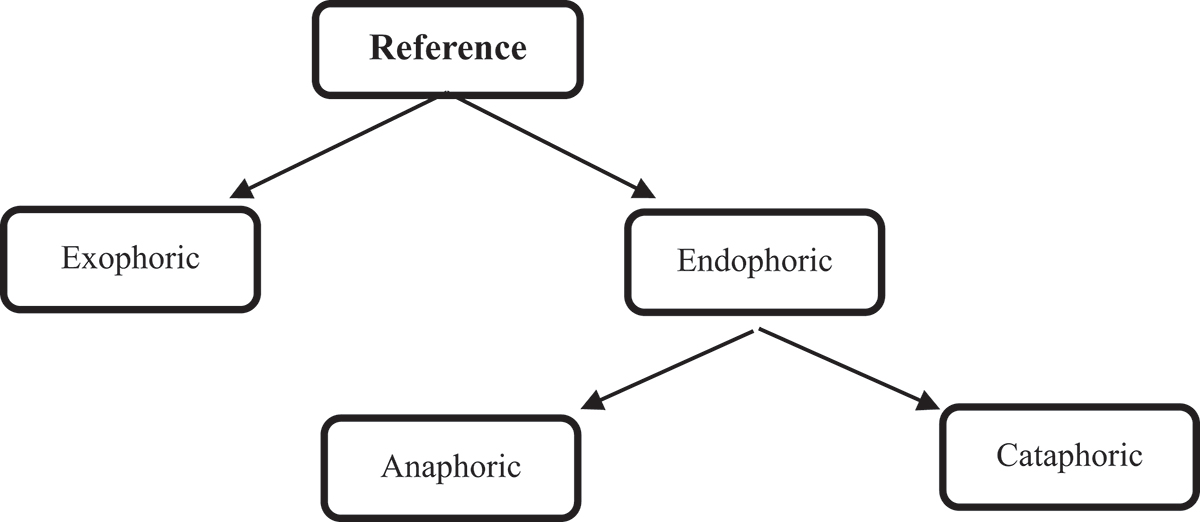

4.7. Reference

According to Halliday and Hasan (1976), reference involves the use of textual elements that cannot be decoded in their own right. The authors identify personals, demonstratives, and comparatives as examples of this category. They explain that these items fall within two broad reference types, exophoric and endophoric. The latter, according to them, can be further divided to anaphoric and cataphoric. Figure 4 is a rough representation of these categories.

Types of reference (Halliday and Hasan 1976).

According to Widdowson (2004), exophoric reference looks outside the text to decode the identity of the linguistic item being referred to. Consider the following example:

| [5] | |The three boys went there together. |

The two referring items, The and there, in [5] cannot be decoded except by going outside the text to consider the specific context, or the shared world between the speaker/writer and the hearer/reader. It is immediately clear, though, that Halliday and Hasan’s model addresses exophoric reference as exclusively situational, and context specific. However, exophora quite often extends beyond the situation to encompass society and culture. Therefore, Paltridge (2012) introduces homophoric reference, “where the identity of the item can be retrieved by reference to cultural knowledge, in general, rather than the specific context of the text” (116). Following is an example from Arabic:

| [6] | |العراقية | التشوبي | طريقة | على | أيديهم | شبكوا |

| |/al`iraaqiyyah/ | /atshuubi/ | /Tariiqat/ | /`alaa/ | /’aydiihim/ | /shabakuu/ | |

| |Iraqi | Chobi | way | on | their hands | put together |

In [6] it is not possible to decode the referent of the Iraqi Chobi without knowledge of the Iraqi culture, particularly in this instance that the Chobi is a folkloric Iraqi dance, usually performed in weddings and particular celebrations. Since this decoding process requires knowledge of culture, rather than the specific context of the statement, reference is homophoric.

Figure 5 presents the adapted types of reference based on Halliday and Hasan (1976) and Paltridge (2012).

Types of reference .

Endophoric reference, on the other hand, involves ties within the text and can be anaphoric, where the interpretation of the linguistic item involves moving back, or cataphoric, where decoding the reference calls for a forward movement in the text (Halliday and Hasan 1976). Consider the following examples:

| [7] | |Linda finished her research project. She had worked day and night to finish it on time. |

| [8] | |He had no choice. John worked hard and finished the project. |

In [7] all the boldfaced referring items are instances of anaphora since they can only be interpreted by going back in the text, whereas in [8] He is cataphoric because its interpretation involves moving forward in the text.

Cutting (2008) adds that endophora can be represented in terms of associative, co-textual relations in addition to the direct anaphoric and cataphoric representations. By way of elaboration, Cutting (2008) introduces the following example (10):

| [9] | |Youtube is a popular video sharing website where users can upload, view and share video clips. |

In example [9], in order to infer that video sharing, meaning public viewing online, is NOT physically passing DVDs to friends, readers have to rely on their knowledge of the “presuppositional pool of ‘website’” (Cutting 2008, 10). Associative endophora, then, entails that a noun phrase is linked to entities that are associated with another noun phrase in the same text. Since this type of endophora was not introduced in the 1976 model of cohesion, it will be added to the model that will be developed in this paper. Figure 6 incorporates this adaptation.

Halliday and Matthiessen (2014) divide reference expressions into two major groups: co-reference, where what is presupposed is the same referent, and comparative reference, where the presupposed is another referent of the same class. Personal and demonstrative pronouns are examples of co-reference, whereas comparative adjectives and adverbs are examples of comparative reference.

In Arabic, all the above categories of reference hold; nevertheless, English and Arabic are very much different in their linguistic structures and textual features (Alfadly and Aldeibani 2013), which is conspicuous in the number of personal pronouns in both languages (Wightwick and Gaafar 2005). While English, for example, has 7 subject pronouns, Arabic has 14. Table 2 illustrates the categories of subject pronouns in both languages.

Subject pronouns in English and Arabic.

| English subject pronoun | Corresponding Arabic pronoun(s) | Meaning of the Arabic pronoun |

|---|---|---|

| I | أنا/’anaa/ | First person singular |

| We | نحن/naHnu/ | First person plural |

| He | هو/huwa/ | Third person singular masculine (people) |

| She | هي/heya/ | Third person singular feminine (people) |

| It | هو/huwa/ | Third person singular masculine (things) |

| هي/heya/ | Third person singular feminine (things) | |

| You | أنتَ/’anta/ | Second person singular masculine |

| أنتِ/’anti/ | Second person singular feminine | |

| أنتما/’antuma/ | Second person dual masculine and feminine | |

| أنتم/’antum/ | Second person plural masculine | |

| أنتن/’antunna/ | Second person plural feminine | |

| They | هم/hum/ | Third person plural masculine |

| هن/hunna/ | Third person plural feminine | |

| هما/humaa/ | Third person dual masculine and feminine |

Even a cursory glance at Table 2 will confirm the observation made by Wightwick and Gaafar (2005, 15) that: “Arabic has more pronouns than English since it has different versions for masculine and feminine, singular and plural, and even special dual pronouns for two people or things.” It is immediately clear from Table 2 that it has two functionally corresponding pronouns in Arabic, you five, and they three. The bigger number of Arabic personals does not mean that identifying referential ties in Arabic is more complicated than in English since in both languages the referent of the pronoun can be decoded exophorically, homophorically, or endophorically. Still, the above set of personal pronouns contains a major difference between the two languages as far as this type of tie is concerned. This difference will be delineated in the following sections.

4.8. Ellipsis

Ellipsis is a cohesive device that involves the omission of linguistic items which can be retrieved from another clause (Hoey 2001). Because of the omission feature, “ellipsis can be thought of as a ‘zero’ tie because the tie is not actually said” (Hatch 1992, 225), yet something is presupposed by means of what has been expunged (Halliday and Matthiessen 2014). The 1976 model of cohesion identified three types of ellipsis, which are nominal, verbal, and clausal, a categorization that has been broadly acknowledged by a number of authors and researchers (e.g., Jabeen, Mehmood, and Iqbal 2013; McCarthy 1991). Following are examples that represent the three categories of ellipsis:

| [10] | |It wasn’t Dexter’s fault, her anger. It was her own. (From Pavone’s The Expats, 141) |

| [11] | |She can do it. I am sure she can. |

| [12] | |Has he arrived? Yes. |

In [10], the ellipsis is nominal since the deleted item is the noun fault. [11] is an example of a verbal ellipsis with part of the verb deleted, and finally, [12] is an instance of clausal ellipsis since the entire clause that normally follows Yes in such answers is deleted. As for Arabic, all the three types of ellipsis exist, yet with some difference vis-à-vis nominal ellipsis, which is not common in Arabic except when the subject of the sentence is dropped in certain cases, which will be discussed later when talking about Arabic as a pro-drop language. As for verbal ellipsis, [11] can be translated to Arabic maintaining the verbal ellipsis as follows: تستطيع أن تفعل ذلك. أنا متأكد أنها تستطيع/tastaTii`u ’an taf`ala dhaalik. ’anaa muta’akkidun ’annahaa tastaTii`/, deleting أن تفعل ذلك/’an taf`ala dhaalik/, which is equivalent to “do it” in [11]. The clausal ellipsis instance in [12] can also be rendered as is in Arabic as follows: هل وصل؟ أجل./hal waSala? ’ajal/, thus crossing out the same parts deleted in English.

Despite the agreement on the three broad categories of ellipsis, a number of issues have emerged regarding this cohesive device. One of those issues is whether ellipsis is always anaphoric or not. A number of researchers emphasize that ellipsis can be merely described in terms of anaphora because the omitted item(s) can only be retrieved by moving backward in the text (Halliday and Hasan 1976; Halliday and Matthiessen 2014), like the movement done in [10], [11], and [12] above. In accordance with this claim, Crystal (2006, 43) maintains that ellipsis “can be recovered only from the preceding discourse.” However, Jones (2012) and McCarthy (1991) confirm that English does have cataphoric ellipsis; McCarthy (1991) provides the following example (43):

| [13] | |If you could, I’d like you to be back here at five thirty. |

Retrieving what has been omitted after could requires a forward movement. Accordingly, ellipsis can be used cataphorically in front-placed subordinate clauses. In Arabic, ellipsis can be described in terms of cataphora, too. The following is an example from Arabic; the English word-for-word translation is also provided.

| [14] | |الانتقال إلى البيت الجديد | قراري أنا، | يكن | لم |

| |/alintiqaal ’ilaa albayt aljadiid/ | /qaraari ’anaa/ | /yakun/ | /lam/ | |

| |Moving to the new house | my decision, | was | not |

The Arabic statement in [14] is functionally equivalent in English to it was not my decision, moving to the new house. In order to retrieve the speaker’s decision, one needs to move forward in the text, which makes this statement an example of cataphoric ellipsis.

Ellipsis was subject to further investigation when Thomas (1987) added more details to the category of verbal ellipsis by further dividing it into two types as far as form is concerned: echoing and auxiliary contrasting. While the former involves using part of the verbal phrase that is just before the omitted part, the latter involves changing the grammatical set of the auxiliary verb into another. The following are examples of echoing and auxiliary contrasting presented, respectively, in [15] and [16]:

| [15] | |A: Are they moving to a new house? |B: Yes, they are. |

| [16] | |A: Are they moving to a new house? |B: They already have. |

As far as Arabic is concerned, it differs from English in that it is a pro-drop language, which means that the subject pronoun can be deleted because Arabic’s rich verbal morphology allows for this, in what is sometimes referred to as zero anaphora (Ryding 2005). Consider the following example:

| [17] | |كثيراً | يزورها | ولذلك | بجدته، | مولع | أحمد |

| |/athiiran/ | /yazuuruhaa/ | wa lidhaalik/ | /bijaddatihi/ | /muula`/ | /’aHmad/ | |

| |alot | visits her | so | of his grandmother, | fond | Ahmed |

It is immediately clear that he, the subject pronoun, of the verb visits is dropped from the Arabic text, which is still grammatically correct in Arabic. This means that in Arabic, this cohesive tie, which is the deleted-yet-retrievable subject pronoun, does not have to be physically present in the text. In English, a statement like “Ahmed is fond of his grandmother, so visits her a lot” is ungrammatical, whereas in Arabic it is grammatical.

4.9. Substitution

Substitution is very much similar to ellipsis except that an explicit indication is given that something has been deleted (Halliday and Matthiessen 2014). Put differently, it is a structural relationship that involves the replacement of one item by another (Jabeen, Mehmood, and Iqbal 2013). Like ellipsis, substitution falls into three categories: nominal, verbal, and clausal. The following are some examples:

| [18] | |I bought a big bag. My sister preferred to buy a small one. | |

| [19] | |Go to the party. You will enjoy your time if you do. | |

| [20] | |You look tired. If so, please, feel free to go home. | |

In [18] one replaces the noun bag, and it is, therefore, an instance of nominal substitution. [19] contains an example of verbal substitution with do substituting for go to the party. Finally, so in [20] replaces an entire clause, You look tired or You are tired which is why it is an instance of clausal substitution. In Arabic, the three substituting items, one, do, and so, exist at the levels of form and function, with the words واحدة/waaHida/, تفعل/taf’al/and كذلك/kadhaalika/that can function the same as the three substituting items in [18], [19], and [20], respectively. Halliday and Matthiessen (2014) maintain that one and do are the most common nominal and verbal substitution items, respectively, whereas so and not are the most common for clausal substitution. However, other words can be used to substitute. For example, McCarthy (1991) provides the following example in which the same is used to substitute a noun:

| [21] | |She chose the roast duck; I chose the same (45). |

The substituting item in [21] can be functionally rendered in Arabic using two words, such as الشيء نفسه/ashshay’a nafsahu/, which can be literally translated into the same thing, thus adding one more word “thing”, which was not structurally necessary in English.

There are still two issues to consider with this cohesive device. The first one is whether it is always anaphoric as claimed by Halliday and Hasan (1976) and Halliday and Matthiessen (2014). In fact, there is no reference to substitution as a cataphoric device in the literature so far. However, in certain types of texts, it seems, one can be cataphoric when it is preceded by a demonstrative this. In this case, one no longer replaces a noun but a general idea. Following is an example from a New York Times op-ed:

| [22] | |The Italians got this one right. Last week,…Their tweets,…, included… |

In this example, this one refers forward to the Italians tweets that mock ISIS’s warning of heading to Rome. The point is that in certain cases, substitution can be cataphoric. The second point is that the lexical items introduced in this section one, do, and so are not always substitutive. On this, Salkie (1995) provides the following examples (36):

| [23] | |One and three make four. |If you do the right thing, you will be fine. |I’m so glad you could come. |

This realization also has grounds in Arabic as واحد/waaHid/(Arabic for one) can have a numeric value, تفعل/taf`al/(Arabic for do) can have the mere function as the main verb in the sentence, and جِدّاً/jiddan/(Arabic for so) can function as a modifier, meaning very.

4.10. Conjunctions

This particular category of cohesive devices has undergone several adaptations since its introduction by Halliday and Hasan in 1976 (Ahangar, Taki, and Rahimi 2012). The reason for this could be that it is not easy to produce an exhaustive list of the entire range of conjunctions (McCarthy 1991). Therefore, the 1976-model of conjunctions, which consisted only of the categories of adversatives, additives, causal, and temporal, went on an adding-up spree that may never come to a decisive end. Halliday and Matthiessen (2014) expanded the four types of conjunctions into nine by adding apposition (e.g., in other words, for example), clarification (e.g., in short, by the way), variation (e.g., instead, except for that), comparative (e.g., similarly, in a different way) and respective (e.g., in this respect, elsewhere). Locke (2004) added one more category, listing, and argues that temporal conjunctions, such as first and second, can also serve listing purposes since they can be used to list the elements of an argument. These expressions, representing the category of listing, are acknowledged to have identical functions in Arabic, too (Lahlali 2009). Table 3 presents the 10 categories of conjunctions with examples from English with Arabic alongside. These categories and examples are adapted from Halliday and Matthiessen (2014), Haywood and Nahmad (1993), Lahlali (2009) and Locke (2004).

Types of conjunctions.

| Conjunctions | English examples | Arabic examples |

|---|---|---|

| Appositive | that is | أي/’ay/ |

| Clarifying | at least | على الأقل/`alaa al’aqall/ |

| Additive | and | وَ/wa/ |

| Adversative | but | لكن/laakin/ |

| Varying | as for | أمّا/’ammaa/ |

| Matter | here | هنا/hunaa/ |

| Manner | similarly | بالمثل/bilmithl/ |

| Spatio-temporal | then, when | ثمّ/thumma/, لمّا/lammaa/, |

| Causal-conditional | so, so that, if, because | فـَ/fa/, لِ/li/, إن/’in/, لأن/li’anna/, |

| Listing | first | أوّلاً/’awwalan/ |

The above sets should not lead to the conclusion that English and Arabic have entirely identical sets of cohesive devices because each language has its own particular system. For example, the one-letter conjunctions وَ/wa/ and فـَ/fa/may have a variety of English correspondences belonging to different sets based on the context they are used in (Abu-Chacra 2007; Haywood and Nahmad 1993).

4.11. Lexical cohesion

According to Smith (2003), lexical cohesion is a seminal contribution of Halliday and Hasan (1976) as it has enabled linguists to find patterns of lexical co-occurrence in texts. However, the two categories of lexical cohesive devices, reiteration and collocation, which appeared in Halliday and Hasan’s 1976 model, witnessed several adjustments, which have been integrated into the model suggested in this paper. Basically, all the developments and adjustments to the 1976 model maintained the category of reiteration, which involves repetition of the same word, while some of them have raised questions about collocation, describing examples of it as arbitrary co-occurrences, thus excluding them from lexical cohesion analysis (Hasan 1984; McCarthy 1988), or including them with certain adjustments that seek to systematize them, yet acknowledging the difficulty of doing so (Tanskanen 2006). It has been agreed, though, that collocation generally refers to the association that links the words that co-occur, or that have the tendency to occur with each other (Sinclair 1991; Stubbs 2001). One development at the level of reiteration is that introduced by Hoey (1991), who divided repetition to two categories, namely simple lexical repetition, such as a girl/girls and complex lexical repetition, referred to by de Beaugrande and Dressler (1981) as partial recurrence, such as drug/drugging. Scott and Tribble (2006) view repetition as a cohesive device in terms of keyness, whereby lexical items that reflect what the text is about are reiterated to signal their importance. One of the most comprehensive models of lexical cohesion has been developed by Halliday and Matthiessen (2014), who have divided lexical cohesion into five categories, which are repetition, synonymy/antonymy, hyponymy, meronymy, and collocation. It might be claimed that this 2014 model is built on a previous categorization introduced by Martin (1992), a classification that encompassed all the lexical types included in the 2014 model except for collocation. Therefore, the general classification of the 1976-model still holds yet with the addition of synonymy/antonymy, meronymy, and hyponymy as categories within it. Within the category of synonymy/antonymy, Halliday and Matthiessen (2014) have maintained the subcategory of general nouns, firstly introduced by Halliday and Hasan (1976), thus introducing lexical items, such as thing, stuff, and place, which can be synonymous with other lexical items in the text in certain situations. This particular group has been referred to in the literature using various terminology, such as signaling nouns (Flowerdew 2003) and shell nouns (Aktas and Cortes 2008). It should be noted here that the subset of synonymy/antonymy has been emphasized as a major cohesive type in Arabic as it is usually used to express a wide range of meanings (Parkinson 2006). Table 4 shows some examples of lexical cohesive devices in English and Arabic.

Lexical cohesive devices in English and Arabic.

| Lexical cohesive device | English examples | Arabic examples |

|---|---|---|

| Repetition | patterns…patterns | نماذج/namaadhij/…نماذج/namaadhij/ |

| Synonymy | big, huge | كبير/kabiir/, ضخم/Dakhm/ |

| Antonymy | tall, short | طويل/Tawiil/, قصير/qaSiir/ |

| Hyponymy | fruit, apple | فواكه/fawaakih/, تفاحة/tuffaaHah/ |

| Meronymy | tree, branch | شجرة/shajarah/, غصن/ghuSn/ |

| Collocation | horse, neighing | حصان/HiSaan/, صهيل/Sahiil/ |

4.12. Parallelism

This cohesive device was not introduced either in Halliday and Hasan (1976) or in Halliday and Matthiessen (2014) models. Yet, parallelism, which by and large refers to the repetition of a certain form or structure for the purposes of emphasis and insistence (de Beaugrande and Dressler 1981), has been acknowledged as a cohesive device by many scholars and authors (e.g., Neumann 2014). As for Arabic, Dikkins, Hervey, and Higgins (2002) assert that parallelism as a cohesive device typically involves repetition of the same grammatical category or categories, and that it is not as common in English as it is in Arabic. If this claim is true, it can explain the absence of this device from the 1976 model and from several other subsequent models of cohesion in English. Adding emphasis to this point, the authors suggest that Arabic-to-English translators should therefore be advised to use summary phrases instead of retaining all the elements of the source Arabic parallels when rendering parallel structures from Arabic to English. This study has added parallelism to the model suggested in this paper because it is acknowledged as a cohesive device not only by English scholars (e.g., de Beaugrande and Dressler 1981) but also by Arabic researchers (e.g., Aziz 2012).

In his analysis of the poetry of the famous Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darweesh, Sultan (2011) cites a number of examples where the poet employs parallel structures as cohesive devices. One of these examples can be found in [24] below, where the form “imperative + adverbial phrase” is repeated in a parallel structure.

| [24] | |خذيني تحت عينيكِ/khudhiinii taHta `aynayki/take me under your eyes |خذيني أينما كنتِ/khudhinii ’aynamaa kunti/take me wherever you are |خذيني كيفما كنتِ/khudhinii kayfamaa kunti/take me however you are |

Following from the above discussion on the developments of the categories of cohesive devices since they were introduced in 1976, it becomes obvious that in order for a model to be comprehensive it should consider all these changes. This does not mean that all studies have to use such a comprehensive model in their analysis of cohesive devices as whether to use it in its entirety depends on the research questions and purposes.

5. Comprehensive model of cohesive devices

In order to build a model of cohesion that can be used across languages and across a variety of genres, there are two issues to be stressed. Firstly, the new model has to build on, rather than supplant the framework that was introduced in Halliday and Hasan (1976). The reason behind this strong recommendation for continuity is that the four-decade-old model has stood the test of time and is still used today by a significant number of authors and researchers. To continue to use the model in its original form or in a modified form means that the researcher engages in dialogue with a formidable body of research throughout which the findings are comparable and mutually interpretable. The investigations within this paradigm are replicable. This is a very rich tradition of language analysis which is, at the same time, open to innovation and the introduction of new more nuanced tools. Secondly, the new model which we wish to present in this paper needs to include all the adaptations and additions that have taken place since the 1976-model was introduced. This degree of comprehensiveness empowers the text and discourse analyst to engage more subtly with a wider variety of text types and across a number of languages. Any use of the new model gains the full benefit of intertextuality while retaining the scope to innovate.

Based on the conceptual framework discussed in the previous section, a comprehensive model of cohesive devices is presented in Table 5.

A comprehensive model of cohesive devices.

| Cohesive devices instrument |

|---|

| Reference Endophoric reference (anaphoric and cataphoric) Exophoric reference Homophoric reference Associative references |

| Ellipsis (anaphoric and cataphoric) nominal – verbal (auxiliary contrasting and echoing) – clausal |

| Substitution (anaphoric and cataphoric) nominal – verbal – clausal |

| Conjunctions appositive – clarifying – additive – adversative – varying – matter – manner – spatio-temporal – causal-conditional – listing |

| Lexical cohesion Repetition (simple/complex) – synonymy/antonymy – collocation – hyponymy – meronymy |

| Parallelism (adjacent; distant) |

6. Conclusion

Although Halliday and Hasan (1976) introduced a seminal model of cohesive devices that have been used intensively in textual analysis over four decades now, it is time to include the contributions of other authors and resources in the 1976 model to come up with a new taxonomy for text analysis. Digging into a myriad of studies on the matter, the present paper has found that a number of elements can be integrated into the Hallidyan classification, for example homophoric reference and associative reference. Other additions have enriched our understanding of certain elements; a case in point in this regard is the further classification of verbal ellipsis into auxiliary contrasting and echoing. The category of ellipsis also witnessed a major development with the introduction of cataphoric ellipsis, since this category was believed to be only anaphoric. The category of conjunctions expanded from 4 elements to 11, and the new category of parallelism has been integrated into the new model. Nevertheless, the findings of the present paper should not be considered rigidly final, and as long as language evolves, more and more studies should be conducted to adapt linguistic models accordingly.

About the authors

Emad A. S. Abu-Ayyash is an assistant professor at the British University in Dubai. His research interests include discourse analysis, TESOL and translation.

John McKenny is an assistant professor at the British University in Dubai. His research interests include corpus linguistics, teaching writing and dialectology.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

Abdul RahmanZ. A.2013. “The Use of Cohesive Devices in Descriptive Writing by Omani Student-Teachers.” Sage Open3 (4): 1–10. doi:10.1177/2158244013506715.Search in Google Scholar

Abu-ChacraF.2007. Arabic: An Essential Grammar. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780203088814Search in Google Scholar

AhangarA. A., G.Taki, and M.Rahimi. 2012. “The Use of Conjunctions as Cohesive Devices in Iranian Sport Live Radio and TV Talks.” SKASE Journal of Theoretical Linguistics9 (2): 56–72.Search in Google Scholar

AktasR. N., and V.Cortes. 2008. “Shell Nouns as Cohesive Devices in Published and ESL Student Writing.” Journal of English for Academic Purposes7 (1): 3–14. doi:10.1016/j.jeap.2008.02.002.Search in Google Scholar

AlfadlyH. O., and A. A.Aldeibani. 2013. “An Analysis of Some Linguistic Problems in Translation between Arabic and English Faced by Yemeni English Majors at Hadramout University.” Journal of Islamic and Human Advanced Research3 (1): 15–26.Search in Google Scholar

AliM. E. E.2016. “Using Cohesive Devices during the Course of Lectures ‘The Lecture’s Role’.” International Research Journal of Social Sciences5 (5): 33–36.Search in Google Scholar

Al-ShahawiS. A. M.2012. “Camels in Arabic and Islamic Culture.” Al-Daei Journal. Accessed 0404, 2015. http://www.darululoom-deoband.com/arabic/magazine/tmp/1328163423fix4sub3file.htm.Search in Google Scholar

AshouriK., and S.Ashouri. 2016. “Analysis of Cohesive Devices and Collocations in English Textbooks and Teachers’ Attention to Them in Azad University of Foreign Languages in Iran.” Indian Journal of Fundamental and Applied Life Sciences6 (2): 17–22.Search in Google Scholar

AzizR. N.2012. “Parallelism as a Cohesive Device in English and Arabic Prayers: Contrastive Analysis.” الأستاذ201 (1): 353–371.Search in Google Scholar

BahaziqA.2016. “Cohesive Devices in Written Discourse: A Discourse Analysis of a Student’s Essay Writing.” English Language Teaching9 (7): 112–119. doi:10.5539/elt.v9n7p112.Search in Google Scholar

BahloulM.2008. Structure and Function of the Arabic Verb. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780203945568Search in Google Scholar

BakerM.2011. In Other Words. 2nd ed. London: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

BatemanJ. A.2008. “Systemic Functional Linguistics and the Notion of Structure: Unanswered Questions, New Possibilities.” In Meaning in Context, edited by J. J.Webster, 24–58. London: Continuum.Search in Google Scholar

BlackC. A.1999. A Step-by-Step Introduction to the Government and Binding Theory of Syntax. Dallas: Summer Institute of Linguistics.Search in Google Scholar

BonyadiA.2011. “Linguistic Manifestations of Modality in Newspaper Editorials.” International Journal of Linguistics3 (1): 1–13. doi:10.5296/ijl.v3i1.799.Search in Google Scholar

BrownG., and G.Yule. 1983. Discourse Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

CarnieA.2014. “Formal Syntax.” The Routledge Handbook of Discourse Analysis. Accessed January13, 2015. http://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9781315852515.ch15.Search in Google Scholar

ChenJ.2008. “An Investigation of EFL Students’ Use of Cohesive Devices.” Asia Pacific Education Review5 (2): 215–225.Search in Google Scholar

ChomskyN.1957. Syntactic Structures. Berlin: Mouton De Gruyter.10.1515/9783112316009Search in Google Scholar

CookG.2010. Discourse. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

CoulthardM.2014. An Introduction to Discourse Analysis. 3rd ed. Abingdon: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

CrossleyS. A., T.Salsbury, and D. S.McNamara. 2010. “The Role of Lexical Cohesive Devices in Triggering Negotiations for Meaning.” Issues in Applied Linguistics18 (1): 55–80.10.5070/L4181005124Search in Google Scholar

CrystalD.2006. How Language Works. London: Penguin Books.Search in Google Scholar

CuttingJ.2008. Pragmatics and Discourse. New York: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

de BeaugrandeR., and W. U.Dressler. 1981. Introduction to Text Linguistics. London: Longman.10.4324/9781315835839Search in Google Scholar

DikkinsJ., S.Hervey, and I.Higgins. 2002. Thinking Arabic Translation. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780203167120Search in Google Scholar

FlowerdewJ.2003. “Signalling Nouns in Discourse.” English for Specific Purposes22 (4): 329–346. doi:10.1016/S0889-4906(02)00017-0.Search in Google Scholar

FowlerR.2003. Linguistics and the Novel. London: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

FromkinV., R.Rodman, and N.Hyams. 2007. An Introduction to Language. Boston: Thomson Wadsworth.Search in Google Scholar

GeeJ. P., and M.Handford. 2011. “Systemic Functional Linguistics.” The Routledge Handbook of Discourse Analysis. Accessed January13, 2015. http://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9780203809068.ch2.Search in Google Scholar

GoldmanS., and J.Murray. 1989. Knowledge of Connectors as Cohesive Devices in Text: A Comparative Study of Native English and ESL Speakers. Santa Barbara: University of California.10.21236/ADA213269Search in Google Scholar

GrangerS., and S.Tyson. 2007. “Connector Usage in the English Essay Writing of Native and Non-Native EFL Speakers of English.” World Englishes15 (1): 17–27. doi:10.1111/j.1467-971X.1996.tb00089.x.Search in Google Scholar

GreenbaumS., and G.Nelson. 2002. An Introduction to English Grammar. Harlow: Pearson Education Limited.Search in Google Scholar

HallC.2005. An Introduction to Language and Linguistics. London: Continuum.Search in Google Scholar

HallidayM. A. K.1978. Language as Social Semiotic. London: Edward Arnold.Search in Google Scholar

HallidayM. A. K.2009. “Methods – Techniques – Problems.” In Continuum Companion to Systemic Functional Linguistics, edited by M. A. K.Halliday and J. J.Webster, 59–86. London: Continuum.Search in Google Scholar

HallidayM. A. K., and R.Hasan. 1976. Cohesion in English. London: Longman.Search in Google Scholar

HallidayM. A. K., and M. I. M.Matthiessen. 2014. An Introduction to Functional Grammar. 4th ed. London: Edward Arnold.10.4324/9780203783771Search in Google Scholar

HasanR.1984. “Coherence and Cohesive Harmony.” In Understanding Reading Comprehension: Cognition, Language, and the Structure of Prose, edited by J.Flood, 181–219. Newark: International Reading Association.Search in Google Scholar

HatchE.1992. Discourse and Language Education. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

HaywoodJ. A., and H. M.Nahmad. 1993. A New Arabic Grammar of the Written Language. London: Lund Humphries.Search in Google Scholar

HoeyM.1991. Patterns of Lexis in Texts. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

HoeyM.2001. Textual Interaction: An Introduction to Written Discourse Analysis. London: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

HolesC.2004. Modern Arabic Structures, Functions, and Varieties. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.Search in Google Scholar

HudsonR.2007. Language Networks: The New Word Grammar. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

JabeenI., A.Mehmood, and M.Iqbal. 2013. “Ellipsis, Reference and Substitution as Cohesive Devices: The Bear by Anton Chekhov.” Academic Research International4 (6): 123–131.Search in Google Scholar

JackendoffR.2002. Foundations of Language: Brain, Meaning, Grammar, Evolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198270126.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

JohnstoneB.2002. Discourse Analysis. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.Search in Google Scholar

JonesR. H.2012. Discourse Analysis. Abingdon: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

JordanG.2004. Theory Construction in Second Language Acquisition. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing.10.1075/lllt.8Search in Google Scholar

KaradenizA.2017. “Cohesion and Coherence in Written Texts of Students of Faculty of Education.” Journal of Education and Training Studies5 (2): 93–99. doi:10.11114/jets.v5i2.1998.Search in Google Scholar

Krein-KühleM.2002. “Cohesion and Coherence in Technical Translation: The Case of Demonstrative Reference.” Linguistica Antverpiensia1 (1): 41–53.Search in Google Scholar

KuoC.-H.1995. “Cohesion and Coherence in Academic Writing: From Lexical Choice to Organization.” RELC Journal26 (1): 47–62. doi:10.1177/003368829502600103.Search in Google Scholar

LahlaliE.2009. How to Write in Arabic. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.Search in Google Scholar

LeoK.2012. “Investigating Cohesion and Coherence Discourse Strategies of Chinese Students with Varied Lengths of Residence in Canada.” TESL Canada Journal29 (6): 157–180. doi:10.18806/tesl.v29i0.1115.Search in Google Scholar

LockeT.2004. Critical Discourse Analysis. London: Continuum International Publishing Group.Search in Google Scholar

MartinJ. R.1992. English Text: System and Structure. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/z.59Search in Google Scholar

MartinJ. R.2004. “Grammatical Structures: What Do We Mean?” In Applying English Grammar, edited by C.Coffin, A.Hewings, and K.O’Halloran, 57–76. London: Arnold.Search in Google Scholar

MartinJ. R.2014. “Evolving Systemic Functional Linguistics: Beyond the Clause.” Functional Linguistics1 (1): 3–24. doi:10.1186/2196-419X-1-3.Search in Google Scholar

McCarthyM.1988. “Some Vocabulary Patterns in Conversation.” In Vocabulary and Language Teaching, edited by R.Carter and M.McCarthy, 181–200. London: Longman.Search in Google Scholar

McCarthyM.1991. Discourse Analysis for Language Teachers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

MenfrediM.2011. “Systemic Functional Linguistics as a Tool for Translation Teaching: Towards a Meaningful Practice.” International Journal of Translation13 (1): 49–62.Search in Google Scholar

MohamedS. Y. S., and A. K.Mudawi. 2015. “Investigating the Use of Cohesive Devices in English as the Second Language Writing Skills.” International Journal of Recent Scientific Research6 (4): 3484–3487.Search in Google Scholar

MorenoA.2003. “The Role of Cohesive Devices as Textual Constraints on Relevance: A Discourse-as-Process View.” International Journal of English Studies3 (1): 111–165.Search in Google Scholar

NeumannS.2014. Contrastive Register Variation. Berlin: De Gruyter.10.1515/9783110238594Search in Google Scholar

PaltridgeB.2012. Discourse Analysis. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.Search in Google Scholar

ParazaranS.2015. “Investigating Grammatical Cohesive Devices: Shifts of Cohesion in Translating Narrative Text Type.” International Journal of Foreign Language Teaching and Research3 (10): 63–82.Search in Google Scholar

ParkinsonD. B.2006. Using Arabic Synonyms. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

RasheedS., and F.Abid. 2016. “A Comparative Study of Lexical Cohesive Devices Used by L1 and L2 Urdu Speakers.” Language in India16 (4): 190–297.Search in Google Scholar

RostamiG., H.Gholami, and S.Piri. 2016. “A Contrastive Study of Cohesive Devices Used in Pre-University and Headway Textbooks.” Journal of Applied Linguistics and Language Research3 (2): 136–147.Search in Google Scholar

RydingK. C.2005. Modern Standard Arabic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

SalkieR.1995. Text and Discourse Analysis. London: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

ScottM., and C.Tribble. 2006. Textual Patterns: Key Words and Corpus Analysis in Language Education. Philadelphia: John Benjamins.10.1075/scl.22Search in Google Scholar

ShaumyanS.1987. A Semiotic Theory of Language. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.Search in Google Scholar

ShaumyanS., and F.Segond. 1994. “Long-Distance Dependencies and Applicative Universal Grammar.” In 15th Conference on Computational Linguistics, edited by M. Nagao, 853–858. Kyoto: Kyoto University.10.3115/991250.991285Search in Google Scholar

SilveiraR.2008. “Cohesive Devices and Translation: An Analysis.” Cadernos de Traducao1 (2): 421–433.Search in Google Scholar

SinclairJ.1991. Corpus, Concordance, Collocation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

SmithC.2003. Modes of Discourse: The Local Structures of Texts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511615108Search in Google Scholar

StubbsM.2001. Words and Phrases: Corpus Studies of Lexical Semantics. Oxford: Blackwell.Search in Google Scholar

StubbsM.2014. “Semantics.” The Routledge Companion to English Studies. Accessed January14, 2015. http://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9781315852515.ch14.Search in Google Scholar

SultanG. S.2011. “Parallelism in Mahmoud Darweesh Poem (A Lover from Palestine).” Journal of College of Basic Education Research11 (2): 361–377.Search in Google Scholar

TanskanenS. K.2006. Collaborating Towards Coherence: Lexical Cohesion in English Discourse. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/pbns.146Search in Google Scholar

TeichE.1999. Systemic Functional Grammar in Natural Language Generation. London: Cassell.Search in Google Scholar

ThomasA.1987. “The Use and Interpretation of Verbally Determinate Verb Group Ellipsis in English.” IRAL – International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching25 (1–4): 1–14. doi:10.1515/iral.1987.25.1-4.1.Search in Google Scholar

ThompsonS., and V.Klerk. 2002. “Dear Reader: A Textual Analysis of Magazine Editorials.” Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies20 (1–2): 105–118. doi:10.2989/16073610209486301.Search in Google Scholar

ThornburyS.2005. Beyond the Sentence: Introducing Discourse Analysis. Oxford: Macmillan Education.Search in Google Scholar

WiddowsonH.2004. Text, Context, Pretext. Malden: Blackwell Publishing.10.1002/9780470758427Search in Google Scholar

WightwickJ., and M.Gaafar. 2005. Easy Arabic Grammar. New York: McGraw-Hill.10.1007/978-1-137-14586-4Search in Google Scholar

XiY.2010. “Cohesion Studies in the Past 30 Years: Development, Application and Chaos.” Language, Society and Culture31: 139–147.Search in Google Scholar

© 2017 Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.