Narrative structure, context and translation in Paulo Coelho’s O Alquimista in English, Arabic and Turkish

-

Sawsan A. Aljahdali

Abstract

The contentious bestsellerdom of Coelho’s O Alquimista (published in 1988) has not only placed it endurably on top of the prestigious bestseller lists, but also made it subject to severe criticism. With copyrights sold in 80 languages, the narrative creates a unique form of communication implementing a prolonged, interactive language–culture relationship, and recreating appealingly unique narrative structures addressing readers in new contexts. This study attempts a functional semantico–semiotic reading of the narrative structures of O Alquimista in English, Arabic and Turkish, relating the “recreated texts” to their sociocultural “context of interpretation”, and viewing them as the outcome of two separate acts of communication functioning successively on the same semantic content. The study argues that rediscoursing the narrative cross-culturally yields variant narrative structures, each constructed twice –internally, in the act of encoding through writing, and externally through the reader–text interaction in reading.

1. Introduction

Addressing the global theme of attaining one’s purpose in life simplistically has not only placed O Alquimista (published in 1988) on top of the prestigious bestseller lists for hundreds of weeks, it has also put it under fire by critics and scholars. With an upward trajectory of translations and sales, the narrative reached unprecedented rates of rights sold in 80 languages by 2014. The narrative was first written in Portuguese by a Brazilian writer who claims “to see the world with Brazilian eyes.” O Alquimista and its author now form a “publishing,” “social” and “cultural” phenomenon (Arias 2001; Hart 2004, 304, 311).

“Bestselling fiction,” “translation” and “culture” may lead interchangeably to each other in this case. In the discourse of bestsellers, factors symbiotically function – critical and cultural values, social and economic environments, and literary aesthetics – to turn this sort of fiction into an image (the term is Bloom’s) designed to satisfy contemporary tastes (Bloom 2008; Botting 2012). Any reading of popular fiction remains incomplete if one of the crucial elements – the world, the reader, and the text– is not considered; they “co-exist in a complex, dynamic relationship” (McCracken 1998, 2). Language remains the medium and is at the heart of this phenomenon; texts are linguistic objects communicating interpersonally with their readers (Hasan 1989; Simpson 2004; Toolan 2001). Language and culture entertain a prolonged, interactive relationship reflected in the language of verbal art (Butt and Lukin 2009; Halliday and Hasan 1985; Hasan 1989, 2009, [1986] 2011).

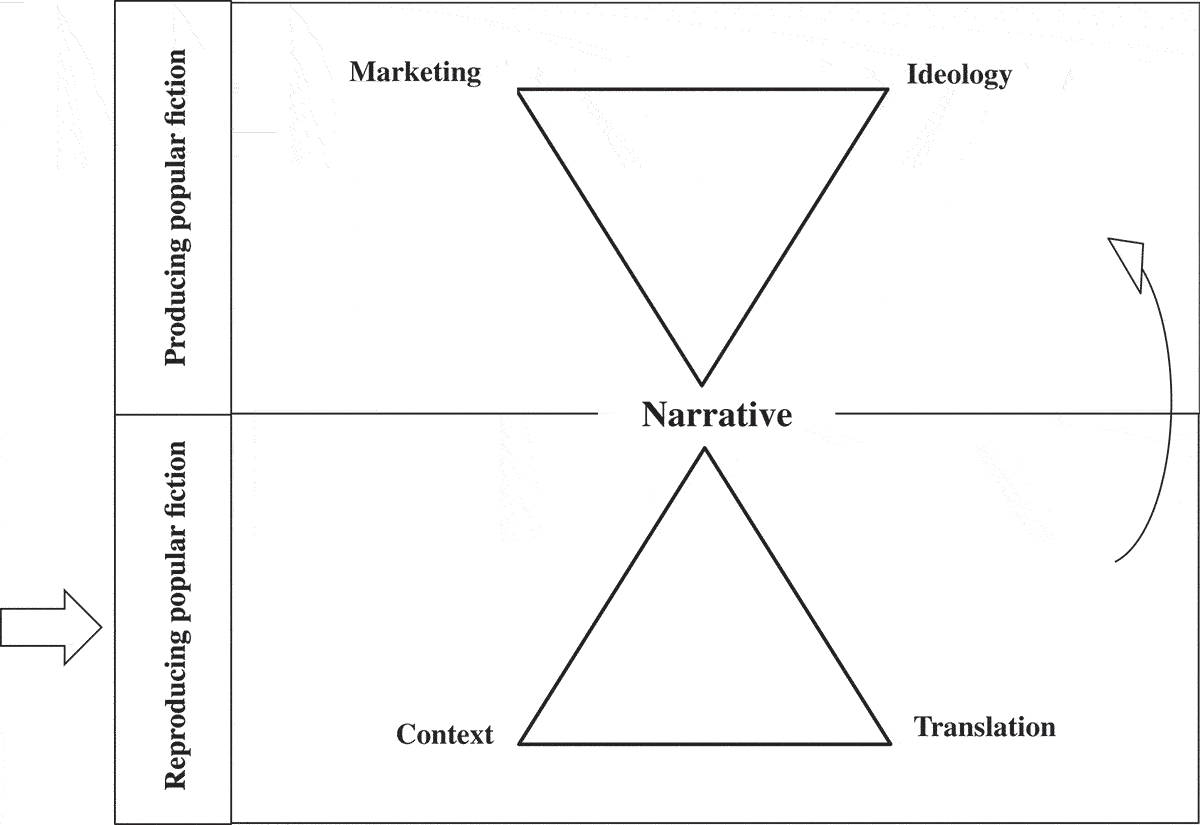

Translating these texts entails “mapping” their meanings between languages-in-contexts (Matthiessen 2001). A text is produced, a broader readership is given access, and, eventually, sales increase. Here, the other side of the coin is put on display as “[b]estsellers have two functions. The first is straightforwardly commercial: to make money. The second function is, loosely, ‘ideological’… [they] tap a specific cultural nerve and thereby serve as exercises in the management of social anxieties” (Botting 2012, 163, italics added). It, therefore, becomes possible to conceive of an indirect relationship behind creating a narrative, the circulation of its ideology, and bestsellerdom on one hand, and the recreated narrative, the act of translation, and the socio-semiotic contextual configurations (CCs) of the reading and writing acts on the other (Figure 1). Significance provided by mechanisms of narration may impinge to a large extent on the translator’s interaction with the text, particularly because such a preoccupation with attempting to appeal to “popular taste” requires an attentive rendering into the recreated narrative structures within the new contexts.

Bestselling narrative and influential factors in original and translation contexts.

This study takes as its main concern the interaction of the translator with the narrative text and, accordingly, his/her recreation of its narrative structure against the sociocultural background of the new context, assuming, following Yaktine (2005, 2006), that the narrative structure is constructed twice: internally, in writing, and externally in reading. The study examines these relations in the copyrighted translations of O Alquimista in English, Arabic and Turkish, therefore, positioning its implied readers in three contexts – the Occident, the Orient and the Turk.

2. Narration and translation: communication acts within the semiotics of context

No wonder a quick survey of responses to any narrative reveals opposing reader views elicited by their reading experience. The concept of narration may be a semantic rendezvous, denoting both the process of transmitting a narrative message and a medium through which communication occurs (Rimmon-Kenan [1983] 2002). This verbal communication involves two sorts of participants in an interaction exceeding the limits of the emitter–message–receiver borderline (Chatman 1978; Enkvist 1964; O’Toole 1982).

Narrating is an interactive process; so is receiving. A writer, through narration, creates a fictional world in which the narrator ushers the reader to the end of the story, where demands are made on the language to play infinite functions and to create the writer–reader relationships. In narratives, “language is not as clothing is to the body; it is the body.” Language is central to verbal art: it is “a point of departure” for the writer and “a point of entry” for the reader. Thus, narratives as texts are instances of the inclusive language system which is a social institution loaded with cultural implications. From here, their value emerges; texts instantiate culture (Butt and Lukin 2009; Chatman 1978; Halliday 1988, 1996; Hasan 1989, 91, 99; O’Toole 1982; (Rimmon-Kenan [1983] 2002; Toolan 2001).

Context is pivotal for the narrative interaction. Narrative texts are processed within two successive, albeit interlocking, contexts, “a context of creation” and “a context of interpretation,” in which the writer and the reader exchange roles in a dialogue of a special nature and the narrative message is refracted (Hasan 1989, 101–103; O’Toole 1982). The level of congruity or divergence between the reader’s context of interpretation and that of the creator facilitates and/or impedes the success of their communication (Hasan [1986] 2011, 1989). Cultural variation entails variation in semiotic potential, which in turn results in different CCs of situations and multiple semantic frameworks for a text. Text contextualisation is thus significant; a situation is meaningful in reference to culture, and cultures vary in codifying their semiotics. This creates a particular area of dissonance described by Hasan as semiotic distance (Halliday 1988; viii–ix; Hasan [1986] 2011, 1989; O’Toole 1982, 223–225; Spencer and Gregory 1964, 60, 100–103). Verbal art is a socio-semiotic construct, and a pragmatic consideration of literature will unearth an immanent cultural content artistically encapsulated in the text of this “self-contained” cultural “institution” (Spencer and Gregory 1964, 60). Culture is, therefore, given a semiotic dimension in any stylistic study of a literary text (Halliday 1988; Halliday and Hasan 1985; O’Toole 1982).

Analogous to the system of language, the system of verbal art, as perceived by Hasan (1989), incorporates three strata ordered respectively in a bottom-up manner as verbalisation, symbolic articulation and theme. It is at the level of verbalisation that the two semiotic systems of language and verbal art intersect. The deautomatised patterning of the patterns (Halliday 1996; Hasan 1989) occupies the area of symbolic articulation. These patterns are accumulated in a process of motivated selection to further promote meanings through the socio–textual interaction at the level of theme. Thus, an in-depth stylistic reading process allows the reader access to the ultimate level of meaning of a text while ascending through levels accessed and manifested by one another (Butt 1988; Butt and Lukin 2009; Hasan 1989).

Translation creates the communicative, interactive environment essential for the transportability of literature. It is a semiotic rather than a mere linguistic process, conducted on several layers of sign–language–culture interaction; translated literature is thus a semiotically transposed human product. The processes of reading and rewriting occur in a special meta-context with contextual variables peculiar to each act of translation. The translator is thus expected to belong to an environment that unconsciously shapes and crucially influences his/her linguistic habits and modes of textual interpretation; the careful reading of the source language text is unquestionably mirrored in his/her choices (Baker 2000, 258–259; Bassnett 2002; Chatman 1978; Dusi 2000; Malmkjær 2004, 16, 22; Matthiessen 2001, 111–113; Muhawi 2000; Petrilli 1992; Sontag 2007). And as translators (writers) as well as their readers get immersed in an interactive dialogue surmounting the borders of the “seemingly disjunctive cultural and linguistic entities” (Wilson 2007), this interaction forms the reader’s first experience with the text, and an engagement with what seems for him/her to be a dialogue with the original author.

Translating involves a complex process of refraction in a mediated interlingual, intercultural communicative transposition (Malmkjær 2004; Reiss [1971] 2000). The translator is proposed to belong to “a special category of communicator” in a “secondary communication” that is “conditioned by another, previous act” (Hatim and Mason 1997, 2). Linkage and separateness are simultaneously upheld for this communicative act in relation to the previous one, while inferiority and subservience are by no means ratified (Bassnett 2002; Hatim and Mason 1997; Nelson and Wilson 2013). Bassnett (2002) highlights the pragmatic role of translation, and outlines the author/translator/reader relationship in the two “separate but linked chains” of Author–Text–Receiver = Translator–Text–Receiver (45). Hatim and Mason (1997) explicate the pseudo-contrariety of the two complementary features (namely linkage and separateness), stressing that the translator “works on the verbal record of an act of communication … and seeks to relay perceived meaning values [“across cultural and linguistic boundaries”] to a (group of) target language receiver(s) as a separate act of communication” (vii, 1, italics added).

3. Narrative structure: an overview

In order to demarcate the direction in which we are going in our investigation of the narrative structure, we need to call upon a sound delineation of the term along narratological, poetic, semiotic and related lines. Despite the broadness of its scope, “narrative structure” represents only one aspect of the narrative text in its interactive sense; the others include both intertextual interactions of the narrative with other texts, and contextual interactions with sociological and sociosemitic values (Yaktine 2006).

A cursory look at the Dictionary of Narratology (Prince 2003) reveals that the narrative structure is not allocated an entry; rather, the term is presented as an example of a structural unity created by the ensemble of compositional networks under the entry “structure” (95). A structuralist–semiotic shade is thus overlain, disregarding both the functionality of these networks in creating the totality of the text in context and the possibility of having the narrative structured and restructured through writing and reading, respectively. Overcoming such a segregation, Hasan affirms that text structure is governed by two agencies – genre and context – and that the “structure” forms the link between the internal texture and external context hence creating a higher-order semantic unity (Butt 1988; Halliday and Hasan 1985; Hasan 1989).

O’Toole (1982) and Yaktine (2005, 2006) correspondingly, yet antithetically, pertinently relate the internal with the external in their designations of the narrative structure. For O’Toole, the “unity and coherence of internal patterning” shape the acts of communication of encoding (writing) and decoding (reading). He proposes that the socio-semiotic values of the structural elements functionally contribute, in an integrative complementary manner, to the construction of the narrative structure, the highest-order semantic level. Yaktine, on the other hand, stresses that the structure of a narrative is created twice: internally, through discoursing the story in writing; and externally, through creating a unique socio-semiotic space with each reader–text interaction. The two approaches converge though in their rejection of the concept of arbitrariness with regard to the choices of narrative elements and linguistic patterns involved in the construction of narrative structures. Concordantly, building on Leech and Short (2007), Boase-Beier (2014) affirms that the narrative structure is iconic of the situation. Therefore, within context, the narrative structure is genuinely semiotic (Chatman 1978); or, to put it more accurately, the narrative structure may be a social semiotic that genuinely connects the narrative texture and context.

4. Recreated narrative structure(s) in the light of multiple contextualisations

4.1. Contexts of creation and interpretation: backdropping the semiotic distance

Translating O Alquimista with its present contentious state complicates the situation further: the context of creation positions Coelho’s translators’ multiply-refracted perceptions of world cultures within three cultural and ideological contexts. The burden of creativity in reproducing an appealing version is duplicated when the deep readers and co-authors are already celebrities with outstanding oeuvre and pre-existing audiences. Careful choice of translators and publishers in the three contexts notably highlight the circumspect attendance of Sant Jordi Asociados, the international presenter of Coelho’s rights, to the details of the cross-cultural transference acts. The list of renowned names recreating the narratives, individually or collaboratively, includes celebrated novelists, poets, literary, published and professional translators.

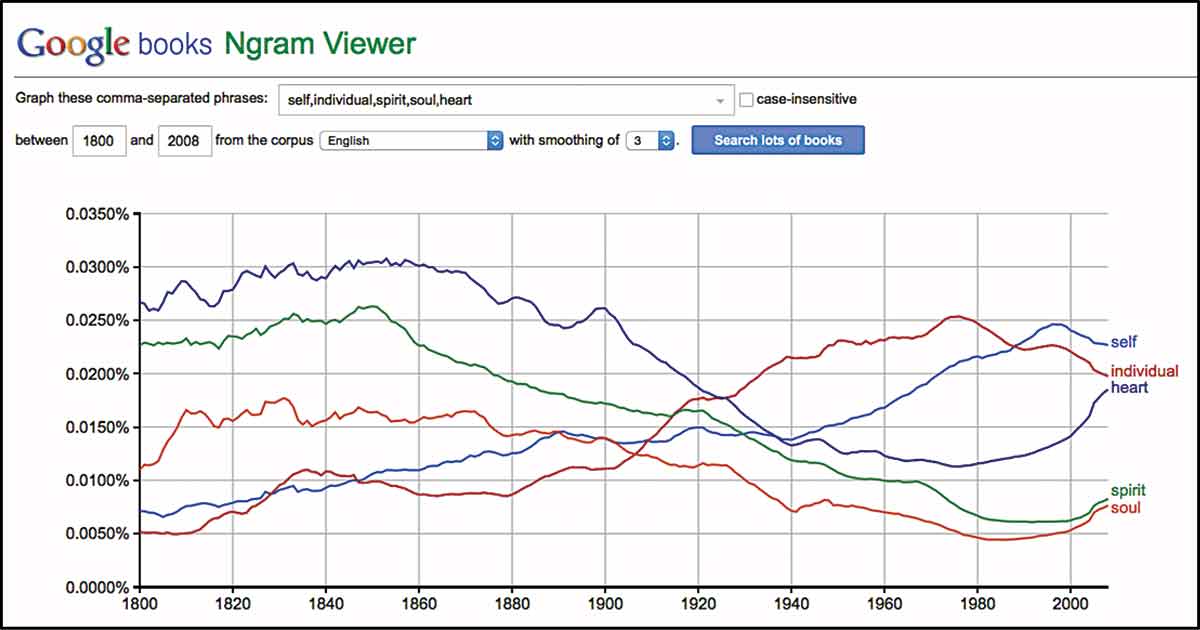

The spectrum of the sociocultural hues of the East, the West and the contrastively unique Turkey creates the contexts of interpretation. English, Arabic and Turkish belong to three distinct language families – Indo-European, Afro-Asiatic and Turkic. The Ethnologue annexes the word “Christian” to the English language category; yet the increasing concern with the individual and the Self and the diminishing interest in the soul and spirit can be perspicuously demonstrated in this context (Figure 2). The problem of dichotomising the spiritual and the material may not literally exist for Arabs who are very attached to their religion. The complexity resides in how to recreate a neutral, unprejudiced view of Arabs and their culture. The challenge is special in the Turkish context where the political, ideological, cultural and religious dualisms breed clashing tendencies toward the East and the West (Alver 2013; Argon 2014; Göknar 2008, 472–477, 501–503; Gürçağlar 2008, 49–50, 86–87; Paker 2004, 6, 13; Stone 2010, 236).

An N-gram view of the recurrence of self, individual, heart, spirit and soul in Google books in the period between 1800 and 2008. Source: Michel et al 2010

4.2. Story: semantic considerations

An insightful understanding of the dispositional reconstruction of the story elements on the discursive level uncovers the mechanisms in which the three different discourses operate to allocate variable degrees of significance to their narrative resources (O’Toole 1982). The three translations are copyrighted by Sant Jordi Asociados, which would considerably assure their direct transposition from the original Portuguese text. Any alterations or adjustments in the translations are thus attributed to the translators’ external narrative structures created after their exposure to the same semantic content.

A distributional-integrative approach to the story events reveals that the story can be broken down into 57 episodes. Each of these episodes forms a minimal semantic unit present in all three versions, and a section of varying length is devoted to each episode. Taking the reader along two material and spiritual story lines framed with a specific epilogue and prologue, the narrative metaphorically utilises the proclaimed aim of the journey to serve other spiritual ends, yielding hence an immanent structure built in the shade of the physical one (Table 1). The two lines meet at a point in Episode 25, which is cardinal for the physical line and simultaneously functions spiritually to facilitate bringing out the inferentially-conceived-of alchemist.

Story bifurcation, episodic distribution and narrative sites.

| Narrative site | Story Bifurcation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Movement | Code | Location | Physical story line (Seeking buried treasure) | Spiritual story line (Spiritual transformation) | |||

| 1 | E’ | Alfayoum | 1 | The alchemist reading Narcissus’ story | |||

| 2 | A | Andalusia: fields | 2 | The dream recurring | 5 | Aimless sheep | |

| 3 | The merchant daughter | 6 | Evil thoughts against sheep | ||||

| 4 | Excitement and worry | 7 | Setting purpose | ||||

| 8 | Father–son argument | ||||||

| 9 | The interest of living with a dream | ||||||

| 3 | B | Andalusia: Tarifa | 10 | Dream interpretation | 12 | The greatest lie and Melchizedek | |

| 11 | Before meeting the girl | 13 | King of Salem and dream pursuit | ||||

| 15 | Payment, freedom and wisdom | 14 | Taking the decision | ||||

| 16 | Starting off the journey | ||||||

| 4 | C | C1 | Tangier: plaza | 17 | First day in Tangier | 18 | Realizing the universal language |

| 5 | C2 | Tangier: crystal shop | 19 | The crystal merchant | 21 | Dream of travel | |

| 20 | A new job | ||||||

| 22 | Reconsidering a dream | ||||||

| 23 | Enormous success | ||||||

| 6 | C3 | Tangier: way to the caravan | 24 | Departing the crystal shop | |||

| 25 | Restoring an original dream | ||||||

| 26 | The Englishman | ||||||

| 27 | Warehouse conversation | ||||||

| 7 | D | Sahara Desert: from Tangier to Alfayoum | 31 | Reading alchemy | 28 | Caravan: swearing and commitment | |

| 29 | Life of the caravan | ||||||

| 30 | Warning of war and Soul of the World | ||||||

| 32 | Complication vs. simplicity | ||||||

| 33 | Life teaches alchemy | ||||||

| 34 | Fear | ||||||

| 35 | Peace | ||||||

| 8 | E | Alfayoum | 36 | First appearance of the alchemist | 38 | Meeting at the well and hawks | |

| 37 | Oasis and Fatima | 42 | The alchemist putting the traveller on the road | ||||

| 39 | Courage of a stranger reading omens | 43 | Discovering life in the desert | ||||

| 40 | Encounter with the alchemist | ||||||

| 41 | Invasion | ||||||

| 44 | Farewell to Fatima | ||||||

| 9 | D’ | D’1 | Sahara Desert: from Alfayoum to Giza | 48 | Alarm of death | 45 | Soul of the World and the heart |

| 46 | Communicating with the heart | ||||||

| 47 | Strength of the soul | ||||||

| 10 | D’2 | Sahara Desert: military camp | 49 | Bargaining life | 50 | Desert and heart: the same language | |

| 51 | Getting ready for the display | 52 | Supernatural display | ||||

| 53 | Astonishment of success | ||||||

| 11 | D’3 | Sahara Desert: at the monastery | 54 | Alchemist’s destiny | 55 | Dreams and role of a man | |

| 12 | F | Giza | 56 | Digging at the pyramids | |||

| 13 | A’ | Andalusia: fields | 57 | The treasure | |||

The claimed simplicity of style presenting the canonical fable in fact enshrouds a highly symbolic structure and discursive complexity; allusion is made to a blend of mystical beliefs from the East and West surpassing the material in search of knowledge, spiritual love and complete transcendence (Alaoui 2012; Erbay and Özbek 2013; Muraleedharan 2011; Soni 2014).

4.3. Title: a paratextual discursive key to constructing narrative structure

Story bifurcation is, in fact, suggested at the outset by the title as the first stylistic choice with which the reader comes in contact. As a paratext, the title forms “a secondary signal” to which the narrative text (as a totality) is linked. The externality of this paratext does not inhibit its high functionality though. It functions pragmatically on the text level as an interface of the two internal and external narrative structures and hence orients the reader–text relationship (Genette 1997; Yaktine 2006). Accordingly, the polyseme of alchemy with its related senses facilitates both encompassing the two acts of physical transmutation and spiritual transformation within one narrative content and directing the reader’s interaction with the text along these two lines.

The definition of alchemy, though built on shared grounds, subsumes variant socio-semiotic implications in the three contexts. The majority of English dictionaries define alchemy as a philosophical pseudoscience or con artistry within the material, physical frame of transmuting metals into gold, and seeking the “grand panacea” and longevity.1 While reference is occasionally made to magic and supernatural powers, the speculative aspect is scarcely acknowledged.2 The word in such usage corresponds incompletely to the Arabic ones (al-sīmyā’,al-kīmyā’ and al-khīmyā’), which agree in most primary senses, with some lexical subtleties for each. To differentiate between the spiritual and material aspects of the science, al-khīmyā’, which can hardly be found in Arabic dictionaries, is of an Egyptian-Greek origin and refers to alchemy, while the Arabic al-kīmyā’ denotes the material aspect of transmutation together with modern chemistry. Al-sīmyā’ derives from the Arabic root s.w.m and encompasses a wider lexical scope (sign, mark, facial expressions, magic and early chemistry) and extends to include some speculative religious and philosophical premises. It is worth mentioning that al-khīmyā’ was brought back to scientific ground during the heyday of the scientific movement in the Arab and Islamic world (corresponding to the Middle Ages in Europe), and taken afterwards to Europe through Spain under the name al-kīmyā” (Al-Hassan n.d.; Bin-Shattooh 2009; Daffah 2003; Kaadan and Qawiji n.d.).3 Examining the senses of the Arabic word sīmyā’ serves to unlock the proposed senses provided by the Turkish title Simyacı in the present context. In Turkish, two loan words stand for “alchemy”: simya (from the Arabic sīmyā”) and alşimi (from the French alchimie). Simyacı consists of simya and a suffix -ici denoting “persons who are professionally or habitually concerned with, or devoted to, the object, person, or quality denoted by the basic words” (Lewis 2000, 55–56).4

In the light of alchemy, motivated selections of stylistic, discursive and (para)textual devices collaborate with the title to heighten the material aspects and meet the expectations of the Occident Self. Coelho’s idiosyncratic prefatory Gospel epigraph, which is kept in Arabic and Turkish, is excluded in English – an omission that correlates with several discursive instances presenting the protagonist’s dismissive view of religion and religious practices. Coelho’s “syncretic, self-invented form [of Catholicism]” (Goodyear 2007) employs, without adherence to static interpretations of doctrines or any form of commitment to practice, a Jungian view of alchemy postulating that the aim of alchemy is individuation (Dash 2012, 2013; Mongy 2005). One’s purpose in life, which is called destiny in an older version of the English translation, has been re-translated as a Personal Legend (Coelho 1992, 2009, 2014). Juxtaposed to the boy’s purpose, this legend foregrounds the mystical and magical nature of alchemy, which “promises that whatever is sought – love, money, inspiration – can be readily attained” (Goodyear 2007). A special patterning of the religious lexis attenuates the spiritual aspect further in Turkish to meet the secularist expectations of Westernisation and uprooting the Ottoman Turks. The neutralised Old Turkic word Tanrı, the only lexical item accepted by the Kemalian government (1932–1950) to replace the Islamic Allāh in the Muslim call for prayers (Göknar 2008; Gürçağlar 2009), substitutes for most of the Islamic and Christian expressions referring to God in the narrative.

Highlighting the spiritual input is essential in addressing Arabic people and cautiously leading Muslim Turks in the reading process. While the title esteems the Arab scientific history, Coelho’s appreciation of the Arab-Islamic literary tradition is intensified in his preface to al-Khīmiyā’ī that narrates the germination of the story idea with an allusion to Ernest Hemingway’s Santiago of The Old Man and the Sea, rejecting implicitly any other possible reference or prejudiced interpretation (See section 4.5) (Coelho 2013). These directing acts are accompanied by two important adjustments. Firstly, some religious expressions, e.g. the Muslim Allāh and the Christian Al-Rabb, are coordinated with a quoted Qur’ānic verse replacing the paraphrase in English and Turkish (Episode 29), and employed to further contextualise the text. Secondly, and more importantly, the prejudicial attitude against Muslim religious practices is obliterated; the deprecatory word “infidels” has undergone a complex process of adjustment (see Section 4.5). In the Turkish context, mysticism, Sufism, luck and superstition occupy a position. Consequently, the Arabic loan word Simyacı is of more appeal to the Turkish reader than the less common, rigid, and materialism-oriented French Alşimist. The Pyramids image on the book cover – reinforced by alchemical ideograms in the twenty-fifth anniversary edition – best retrieves the mystical, metaphysical ends of the human monomyths and esoteric journeys (Erbay and Özbek 2013; Mongy 2005). Throughout the text, the reader is led by the Ç.N.’s (i.e. çevirmenin notları, translator’s notes) that, presuming a non-Christian reader, delineate Biblical terms.

4.4. Spatiotemporal relations discoursed and redisoursed

Accommodating the above-mentioned units against the narrative “rarely arbitrary” spatiotemporal backdrop is inescapably essential in creating syntagmatic relations within the composite of units and providing the values against which the character is portrayed and/or judged (O’Toole 1982). A sort of tension is created from the beginning allowing the two strands of the physical and spiritual plots to interweave; the title and the proleptic Greek myth in the Prologue get the reader, while awaiting the aforementioned alchemist, unconsciously immersed in the transformation of the new alchemist, Santiago. In fact, the proposed linearity of the chronological narration of O Alquimista is not precisely held; the narrative incorporates a number of digressions that disclose a broad spectrum of intertextual interactions collaborating with the few analeptic anachronies to disturb the alignment of the chronological disposition of events on the story and discourse levels (Alaoui 2012; Mongy 2005; Nasr-Allah 1999). On the (con)textual level, time is “unspecified” or, rather, obscured (Ibrahim 2013), creating the essential fantastic world characteristic of bestsellers and allowing room for the implementation of alchemy as a motif. The narrative alludes, historically speaking, to an era after the Spanish Reconquista in 1492, which corresponds to the realm of the Memluk Sultanate (1250–1517) when the “Islamic Egypt’s glory reached its zenith” (Perry 2004, 51–52). Alfayoum, nonetheless, is historically misrepresented as living in a primitive era providing the land of fantasy.

4.4.1. Narrative placement and interpersonal positioning

The opening clause of the narrative (Episode 2) presents an explicit realisation of what Hasan (1996) calls the Placement Act – a placement that provides an interesting case in the three versions. Character particularisation is attained explicitly, unconventionally abruptly, with a declarative relational clause with two definite nominal groups as Participants. The clause is, again unexpectedly, duplicated in the Arabic and Turkish Epilogue (Episode 57) with a deictic change in the former and identical enunciation in the latter. It is completely excluded in the English Epilogue. The clause reads as (Coelho 1996,17, 2009; 3):

(Eng) The boy’s name was Santiago.

(Tr) Delikanlının adı Santiago idi.

Delikanlı-nın ad-ı Santiago idi

Young man-GEN name-3rdPOSS Santiago PAST-3rd-SING.

The clause is semantically disintegrated and grammatically different to the surrounding context. To open a path of communication with the narratee before distancing him temporally (Hasan 1996), the clause takes the simple past tense in English and Turkish for the present of the discourse. The past of the past tense is used to refer to events and states past to the discourse time. This latter tense is realised by had as a Finite in English, and by -miş for the inferential past tense or -mişti for the pluperfect past in Turkish. This interpersonal deixis is different in Arabic: the simple present tense is used instead in this introductory clause as present of the discourse, while the narration of the following states and events that are past to the discourse takes both the simple past and past of the past. The opening clause appears in the simple present as (Coelho 2013, 23):

(Ar) Ism-uh-u Santyāghū.

Name-3rdPOSS-NOM Santiago

His name (is) Santiago.

The absence of the Process element does not, conventionally, obscure tense (Matthiessen 2001; Saadany 2005); rather, restoring the verbal group, and hence tense, in the Epilogue contrastively demystifies tense in the above clause (Coelho 2013, 195):

(Ar) Kāna ism-uh-u Santyāghū.

Be-PAST Name-3rdPOSS-NOM Santiago

His name was Santiago.

This use of tense may be strategic in catching attention. Such a Placement may be contrasted with its introductory counterpart in Arabic philosophical essays which tends to catch the reader’s interest by presenting an “intentionally vague” element in the introduction (Attention Catcher) before drawing logical links between the title and the argument statement (Saadany 2005). This stylistically unfamiliar introductory clause in the narrative may thus function collaboratively with the Prologue and preceding paratexts to both catch the reader’s attention and/or deliberately distance him from the text. Any narrated (mis-)presentation of the protagonist’s refraction of the Arab’s acquaintance may thus be justified and a sense of appreciation of the lenses of the original Brazilian writer may be created.

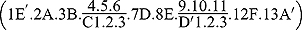

4.4.2. Reproducing the semiotics of space

The journey proceeds not only in time but also, more importantly, in space. Inconsistency of time frames advises against utilising time as a tool for both segmenting the narrative discursively and textually and making inferences on the construction of the narrative structures. Place instead may provide the criterion that would function properly to serve this end. Consequently, the 57 episodes can be accommodated within 13 movements, and thus be distributed along the narrative sites in which narration takes distinct modes and lexicogrammatical features (see Table 1). Guided by Halliday and Hasan (1985) and Yaktine (2005), delineating the site-movement correlations aids in devising the following formula that would set a structural potential according to which the different constructions of the internal structures in the three versions are explored.

*(‘) denotes a second(ary) placement

Interestingly, the divergent treatments of the internal narrative structures and recreations of the external ones by the translators yield a varying number of sections allotted to these episodes. While the English version is divided into 47 sections, the number decreases to 43 in Arabic and rises to 54 in Turkish. The varying number of sections demonstrates how each translator segments the total narrative semantics into functions and how his/her interaction with these functions, according to dissimilar criteria, produces variant structures and provides the reader with a further customised version to interact with.

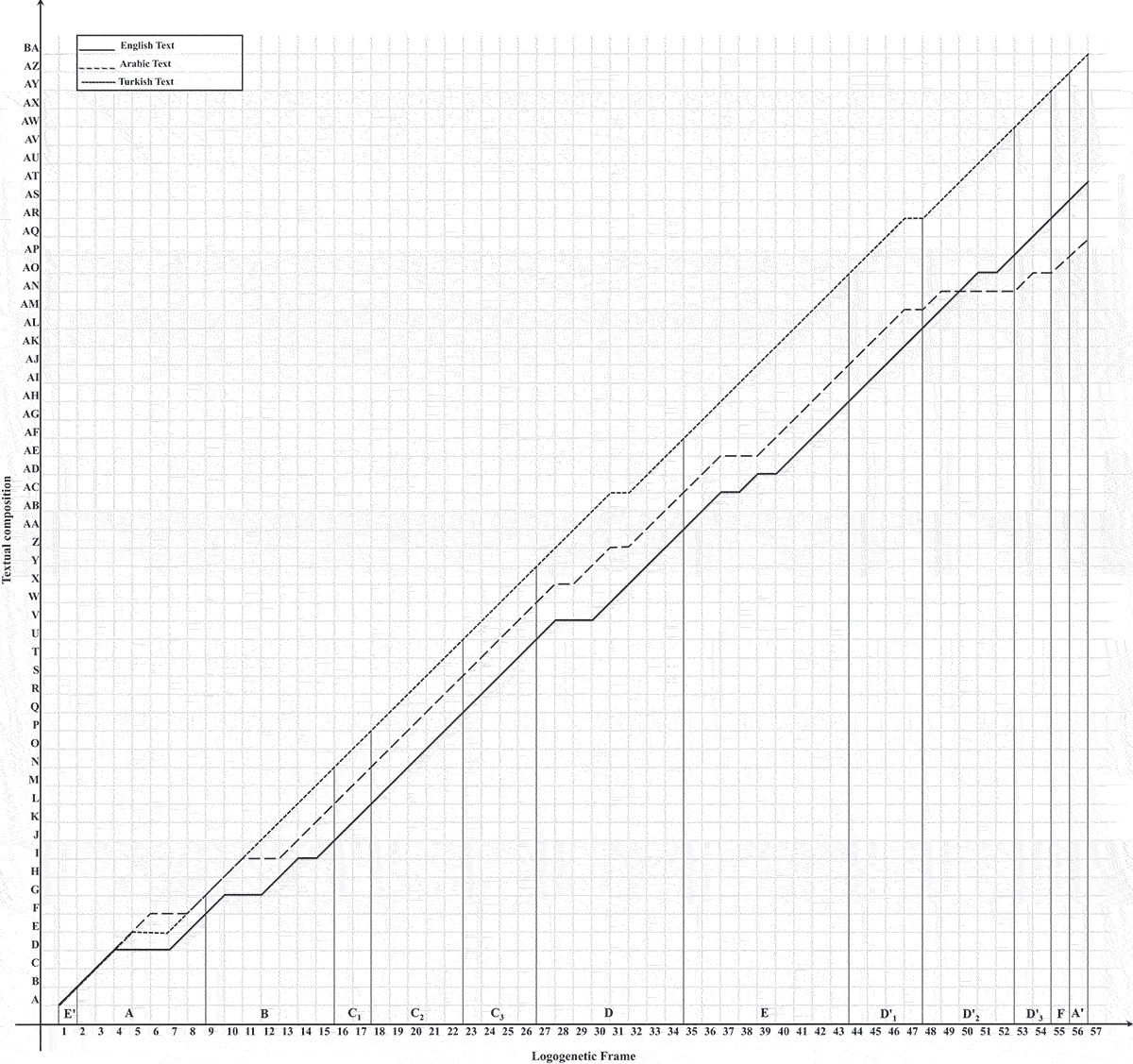

The sections vary in length considerably; however, each is devoted to one specific semantic unit, extending over a varying duration and conceived of and internalised variably. Correlating sections with sites in the light of the above formula, we come to conclude the existence of the following structural potentials for the three versions that can be visually presented as in Figure 3:

A comparative view of the textual and discursive construction of the narrative structures in the three versions.

(Eng)

(Ar)

(Tr)

A comparative view of the above structural compositions reveals the stretching and/or shortening of the episodic disposition, functionality perception, textual segmentation, and consequently the prolonged and/or elided duration and impact of the reader’s engagement with the text within a space-limit. Simyacı, with its generosity of sectioning, creates a complex of interest and intrigue through a gradual gaining of momentum, sharing a generic feature with the Turkish telenovelas (a culture-specific form of popular fiction) where the “overlapping intrigues … are highlighted by the end of each episode” (Buccianti 2010). Juxtaposed as such, Simyacı may be viewed as further securing cultural accommodation. This may set the rationale behind segmenting Movement 10D2, for instance, into five sections. Tension in 10D2 is created for the Arab reader by both the idea of transcendence and locale; engrossment of the Arab reader in the desert may require an uninterrupted mode of narration. The English version, however, disregards these considerations and rather depends on a time-based account of the events in the camp hence providing sectioning on a daily basis.

4.5. Dramatis personae in the three contexts: a socio-semiotic view

Coelho’s characters are symbolic as well (Alaoui 2012; Hart 2004; Nakagome 2014) – a fact that pushes our argument further for the significance of semiotic distance in modulating the semiotic act of translating. Starting from the selectivity exercised on the characters in relation to setting and theme up to the (absence of) naming, O Alquimista utilises the deictic aspect of proper names to specifically delineate its characters.

The protagonist’s name in O Alquimista presents an interesting case both on the narrative and translation scales. As a way of appealing more to the reader’s dreams and individuation, scarcity of naming amplifies the character’s attainment of Personal Legends and hence reinforces through relative anonymity that Personal Legends apply to the readers themselves (Nakagome 2014). Right after introducing Santiago, he is positioned in a setting alluding to a history behind the naming and characterisation. Santiago, as a name, can hardly be remembered afterwards, as almost all instances of reference to the protagonist come in one of the following expressions – the boy, the shepherd, the young Arab, the Spanish boy, or their equivalents in Arabic and Turkish.

Metaphorically, once mentioned in Episode 2, the protagonist’s name scarcely recurs in the three texts, urging a distinctive interaction on the reader’s side. Santiago recurs with a dual significance in English: narrative and iconographic. The reader is reminded of the name later (Episodes 17 and 40) upon comparing the Moors in their prayer and the alchemist on his horse to the José Gambino statue in Santiago de Compostela – the “infidels” beneath Santiago Matamoros’ white horse (Coelho 2009, 34, 109). The name recurs thrice in Arabic and Turkish; yet, through its monosemous reference to the boy, the Spanish iconicity is camouflaged.5

The statue has its spiritual, historical and political value in the Spanish discourse as “medieval iconology.” The legendary identity of St. James, the patron saint, is three-fold: the apostle, the pilgrim (Santiago Peregrino), and the knight (Santiago Matamoros) (Chapman 2012; Tiffany 2002). The Spanish phrase, Santiago Matamoros, encompasses Iago (lit., “James” or “Joseph”); and Matamoros, a compound of matar (v.tr. “to kill, to slaughter”) and moro (“Moorish, Moor, Arab, pejorative term referring to a North African or Arab person”). St. James (the Moor-Slayer) is said to appear in a vision in the battlefield against the Moors in the Spanish Reconquista giving it “a divine approval” (García 2009, 69, 74, 77; Herwaarden, Shaffer, and Gardner 2003, 463–465; Lanzi and Lanzi 2004, 64; Moore 1996).6

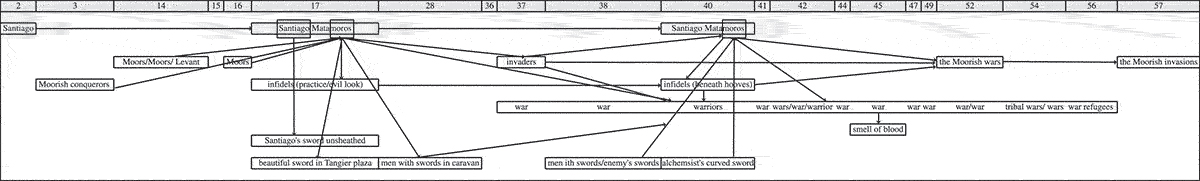

Santiago and Santiago Matamoros significantly connect throughout the English text with other lexical items in a lexical chain; the chain is, however, eloquently broken in Arabic and Turkish. Despite the complicated English attitude toward the knightly aspect of the legend, the translation sets and intensifies the image against the backdrop of the war against the Moors defusing any prejudicial stance against the English people or Santiago Matamoros. The allegorical function of this name suggests, through the chain, an upsetting, bloody image of the disparaged Muslim moros (see Figure 4), appertaining to an Arab stereotype drawn by Orientalists presenting them as thieves, indolent, fierce, illiterate and naïve (Alaoui 2012; Tooti 2006). Insistence on the knightly name may underscore the protagonist’s attitude and may echo the recurrent voices of the Christian community in his area/era.

Protagonist’s name in a lexical chain developing the narrative structure in English.

Cognizant of the hazard of recreating the same presentation to the Arab reader, the rediscoursed Arabic narrative desperately needs to break the chain. A rather neutral version thematically disintegrates the above correlated senses, creating smaller chains with an autonomous image in each. The image of Santiago Matamoros is linked to “malefactors,” and Santiago as a name is delimited to the boy. Reference to Saint James is made through the Latin version of the name, i.e. Jacobus (Chapman 2012), in its Arabic form Yaʿqūb, with the Syriac mār (lit., “saint, lord and martyr”) as a title.7 The Arab subconscious is thus directed to the way to Santiago de Compostela, Ṭarīqu Māri Yaʿqūb. This adjustment is not attributed to the difficulty of transliterating the name; the complexity relies rather in the need for neutralising, or rather reversing, the pejorative value of “the infidels” and other words. The paragraph first mentioning Santiago Matatmoros in Tangier is completely deleted from the text; the second in Alfayoum is adjusted: St. James, the palmer and apostle, defeats the malefactors. Instead of presenting Arabs as “invaders” in Spain, as described in English, or portraying them bloodily, the warrior chain – be they virtuous or transgressing – encompasses all warriors in one word, muḥārib “warrior” (pl. muḥāribūn); war is given a spiritually-inspired dimension as a virtuous way of living.

Cohesive devices used in transferring the identity of St. James in Turkish may yield a peaceful, unbiased translation that will assure the Turkish reader of any religious background. While breaking the direct link to the protagonist’s name, the identity of St. James as an apostle is highlighted in two ways: through reference to his ancestors, Zebedioğlu Aziz Yakub’un heykelini görürdü – “He saw the statue of St. James, son of Zebedee”; and Zebedioğlu Aziz Yakub’un heykelini anımsadı – “He remembered the statue of St. James, son of Zebedee”; and through a translator’s note uncovering the identity of this figure as a martyred apostle (Coelho 1996, 51, 125, translation mine). The less pejorative or rather neutral “imansız” (faithless, unbeliever, atheist) is used instead to refer to the Moors. The translator tries to keep a balance in representing Arabs by invoking both negative and positive senses; the thief in Tangier is an Arap çocuk, “Arab child, chap”; yet, Fatima’s pride as an Arab girl is with the mücahitler (champions of Islam, warriors), a word with an Arabic origin deriving from cihat (Ar. jihād, i.e. (Islam) holy war). The vast majority of Turks are Muslims who highly value the Islamic conquests in several parts of Asia, Europe and Africa.

5. Conclusion

The dynamicity of the mutually interactive triad of translation, context and narrative structure comes to the fore in the context of bestsellers and in the light of the above premises. The story has been concordantly reproduced with variable semantic ramifications and unique versions of re-discoursing; each is justified by the semiotics of value systems within the receiving culture. These mirror both the translator’s sense of external narrative structures (the translator as reader) and their internal structures (the translator as writer). Both perspectives impinge largely on the reader’s interaction with narrative.

Structuring the narrative in O Alquimista is bound to space rather than time; hence, foregrounding space as a further criteria tool in scrutinising the narrative structure individually or comparatively. Starting with the title that creates particular “narrative positions” (Boase-Beier 2014), the translators interact variably both semiotically and textually with the spatiotemporal and characteriological elements of the narrative: altering considerably the episodic dispositions and typographical proportions; reshaping the cohesive factors, inclusive of the lexical chain of naming and portraying; and adjusting tense resources and the interpersonal positioning with the reader.

The reproduced versions strive to particularly preserve Coelho’s renowned preoccupation with simplicity and appeal to popular taste. Heedfully attended and contextualised, each of these narratives structures becomes iconic of the norms of the new contexts. The English version teleologically neutralises the spiritual semantic content and heightens the individualist purport, emphasising a sense of self-actualisation on this mystical-material ground. In Arabic, the translation surmounts the difficulty of safely engaging the reader with a portrait of his/her own identity and culture refracted by “Brazilian eyes”; evading senses of bigotry on discourse and textual levels, and approaching the Arab reader amicably. The Turkish text can be sufficiently interpolated within its meta-context as it confronts the challenge of “the [present-day] complex ‘who-ness’ of Turks and Turkey” (Paker 2004, 13). A uniflow drift of emotions and ideas is created toward the East while a sense of the West is activated. Spirituality is given prominence; yet, linguistic patterns are modulated to satisfy the secularist trends, yielding a version assuring the Turkish reader of any background.

Funding statement: This work was supported by the Saudi Government and King AbdulAziz University.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks are due to my Principal and Associate Supervisors at Macquarie University, A/P David Butt and Dr Annabelle Lukin, for their invaluable advice and constant support; to the Saudi Government and King AbdulAziz University for granting me the Ph.D. scholarship; to my endlessly supportive parents; to Mrs Nevine Wahbe, an Egyptian translator, for the insightful discussions on translation issues; and to my dear friends Ms Salwa Alyami and Mrs Rabab Hashem for the interesting discussions and reflections on ideas in this script.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

- 1.

American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, 5th ed., s.v. “alchemy.” http://www.thefreedictionary.com/alchemy (acessed 29 July 2015).

Collins English Dictionary, s.v. “alchemy.” http://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/alchemy?showCookiePolicy=true (accessed 29 July 2015).

- 2.

Ologies & -Isms. s.v. “alchemy.” http://www.thefreedictionary.com/alchemy (accessed 29 July 2015).

Dictionary of Unfamiliar Words by Diagram Group, s.v. “alchemy.” http://www.thefreedictionary.com/alchemy (accessed 29 July 2015).

Merriam-Webster Dictionary, s.v. “alchemy.” http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/alchemy (accessed 29 July 2015).

Random House Kernerman Webster’s College Dictionary, s.v. “alchemy.” http://www.thefreedictionary.com/alchemy (accessed 28 July 2015).

- 3.

Al-Rā’id: muʻjamun lughawīyyun ʻasrīyyun ruttibat mufradātuhu wifqan li-ḥurūfihā al-’ūlā, comp. Jubran Masood (Beirut: Dar el-Ilm Lilmalayin, 1992), s.v. “sīmyā’.”

Muʿjam al-Lughati al-ʿarabīyyati al-Muʿāṣirah, comp. Ahmad Mukhtar Omar (Cairo: ʿālam Al-Kutub, 2008), s.v. “sīmyā’.”

Lisānu Al-ʿarab, 7th ed., s.v. “sīmyā’.” Dar Sadir, 2003. http://library.islamweb.net/newlibrary/display_book.php?idfrom=4068&idto=4068&bk_no=122&ID=4075 (accessed 4 February 2015).

Online Etymology Dictionary, s.v. “alchemy.” http://www.etymonline.com/abbr.php?allowed_in_frame=0 (accessed 2 February 2015).

- 4.

Etimoloji Türkçe, s.v. “simya.” http://www.etimolojiturkce.com/kelime/simya (accessed 29 July 2015).

Güncel Türkçe Sözlük, s.v. “alşimi.” Türk Dil Kurumu, 2006. http:// tdk.gov.tr/index.php?option = com_gts&arama = gts&guid = TDK.GTS.5513d8be4d05a8.64438136 (accessed 2 February 2015).

Güncel Türkçe Sözlük, s.v. “simya.” Türk Dil Kurumu, 2006. http://tdk.gov.tr/index.php?option=com_gts&arama=gts&guid=TDK.GTS.5513d57fe8c167.12823946 (accessed 29 July 2015).

Sesli Sözlük, s.v. “simya.” http://www.seslisozluk.net/simya-nedir-ne-demek/ (accessed 29 July 2015).

Türkçe Sözlük Ara-Bul, s.v. “alşimi.” Dil Derneği, 2012. http://www.dildernegi.org.tr/TR,274/turkce-sozluk-ara-bul.html (accessed 29 July 2015).

Türkçe Sözlük Ara-Bul, s.v. “simya.” Dil Derneği, 2012. http://www.dildernegi.org.tr/TR,274/turkce-sozluk-ara-bul.html (accessed 29 July 2015).

- 5.

New World Encyclopedia, s.v. “infidel.” http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Infidel (accessed 31 July 2015).

- 6.

Collins Complete Spanish Electronic Dictionary, s.v. “matar.” Harper Collins Publishers, 2011. http://www.spanishdict.com/translate/matar (accessed 29 July 2015).

Webster’s New World Concise Spanish Dictionary, s.v. “moro.” Harrap Publishers Limited, 2006. http://www.spanishdict.com/translate/moro (accessed 20 July 2015).

- 7.

Iʿrif Kanīsatak Iʿrif Lughatak: Qāmūs Al-Muṣṭalahāt al-Kanasīyyah, comp. Tadars Malti (Cairo: Matbaat Al-Okhwah Al-Misriyyin, 1991), s.v. “mār.”

References

Al-Rā’id: muʻjamun lughawīyyun ʻasrīyyun ruttibat mufradātuhu wifqan li-ḥurūfihā al-’ūlā . Compiled by Jubran Masood . Beirut : Dar el-Ilm Lilmalayin , 1992 . Suche in Google Scholar

Alaoui M. H. 2012 . “ Tanāṣṣ al-ḥaky fī riwāyati Al-Khīmyāʼī aw Paulo Coelho sāriqu “ḥulumu al-ʿarab” .” Al-Andalus Magreb 19 : 9 – 30 . Suche in Google Scholar

Al-Hassan A. n.d. “ Al-Kīmyāʼ wa al-khīmyāʼ wa al-taqniyatu al-kīmyāʼiyyah .” In Tarjamāt Markaz Ibn al-Banna al-Maraakishi . Translated by Kanzah Fathi Accessed February13 2015 . http://www.albanna.ma/Article.aspx?C=5634 Suche in Google Scholar

Alver A. 2013 . “ Orhan Pamuk’un Kar Romanında Doğu ve Batı Kimlikle Arasındaki Etkileşime Analitik Bakış .” Turkish Studies: International Periodical for the Languages, Literature and History of Turkish or Turkic 8 ( 13 ). http://www.turkishstudies.net/Makaleler/1833224244_28AlverAhmet-arm-469-482.pdf 10.7827/TurkishStudies.5635Suche in Google Scholar

Argon K. 2014 . “ How Can Turkish Islamic Fine Arts Help Us Understand Higher Spirituality? ” HuffPost Religion . Accessed 1106 2014 . http://www.huffingtonpost.com/kemal-argon/turkish-islamic-fine-arts_b_5085071.html Suche in Google Scholar

Arias J. 2001 . Paulo Coelho: Confessions of a Pilgrim (Biography) . Translated by Anne McLean . Sydney : Harper Collins Publishers . Suche in Google Scholar

Baker M. 2000 . “ Towards a Methodology for Investigating the Style of a Literary Translator .” Target 12 ( 2 ): 241 – 266 . doi: 10.1075/target . Suche in Google Scholar

Bassnett S. 2002 . Translation Studies . 3rd ed. London : Routledge . 10.4324/9780203427460Suche in Google Scholar

Bin-Shattooh A. 2009 . “ Malāmiḥu al-Tafkīri al-Sīmiyā’iyy fī al-Lughati ʿinda al-Jāḥiẓ min khilāli al-Bayāni wa al-Tabiyīn .” MA Diss. , Universite Kasdi Merbah-Ouargla , Algeria . Suche in Google Scholar

Bloom C. 2008 . Bestsellers: Popular Fiction since 1900 . Hampshire : Palgrave Macmillan . 10.1057/9780230583870Suche in Google Scholar

Boase-Beier J. 2014 . “ Translation and the Representation of Thought: The Case of Herta Muller .” Language and Literature 23 ( 3 ): 213 – 226 . doi: 10.1177/0963947014536503 . Suche in Google Scholar

Botting F. 2012 . “ Bestselling Fiction: Machinery, Economy, Excess .” In The Cambridge Companion to Popular Fiction , edited by D. Glover and S.McCracken , 159 – 174 . New York : Cambridge University Press . 10.1017/CCOL9780521513371.011Suche in Google Scholar

Buccianti A. 2010 . “ Dubbed Turkish Soap Operas Conquering the Arab World: Social Liberation or Cultural Alienation? ” Arab Media & Society 10 (Spring). Accessed 12 August 2015. http://www.arabmediasociety.org/index.php?article=735&p=0 . Suche in Google Scholar

Butt D. 1988 . “ Randomness, Order and the Latent Patterning of Text .” In Functions of Style , edited by D. Birch and M.O’Toole . London : Pinter Publishers . Suche in Google Scholar

Butt D. , and A.Lukin . 2009 . “ Stylistic Analysis: Construing Aesthetic Organisation .” In Continuum Companion to Systemic Functional Linguistics , edited by M. A. K. Halliday and J. J.Webster . London : Continuum . Suche in Google Scholar

Chapman A. 2012 . Patrons and Patron Saints in Early Modern English Literature 21 . New York : Routledge . 10.4324/9780203077542Suche in Google Scholar

Chatman S. 1978 . Story and Discourse: Narrative Structure in Fiction and Film . Ithaca : Cornell University Press . Suche in Google Scholar

Coelho P. 1992 . The Alchemist . Translated by Alan Clarke . London : Harper Collins . Suche in Google Scholar

Coelho P. 1996 . Simyacı . Translated by Özdemir İnce . Istanbul : Can Sanat Yayınları . Suche in Google Scholar

Coelho P. 2009 . The Alchemist . Translated by Alan Clarke . London : Harper Collins . Suche in Google Scholar

Coelho P. 2013 . Al-Khīmyā’ī . Translated by Jawad Saydawi . Beirut : All Prints Distributors & Publishers . Suche in Google Scholar

Coelho P. 2014 . The Alchemist . Translated by Alan Clarke . New York : HarperCollins . Suche in Google Scholar

Daffah B. 2003 . “ ʻIlmu al-sīmiyā’ fi al-turāthi al-ʻarabī .” Al-Turath Al-ʻarabi 91 : 68 – 79 . Suche in Google Scholar

Dash R. K. 2012 . “ Alchemy of the Soul: A Comparative Study of Hermann Hesse’s Siddhartha and Paulo Coelho’s The Alchemist .” Search: A Journal of Arts, Humanities and Management 2 : 17 – 23 . Suche in Google Scholar

Dash R. K. 2013 . “ Is Postmodernism Dead? ” Language in India 13 ( 4 ): 235 – 246 . http://www.languageinindia.com/april2013/rajendrakumarpostmodernism.pdf . Suche in Google Scholar

Dusi N. 2000 . “ Translating, Adapting, Transposing .” Applied Semiotics, A Learned Journal of Literary Research on the World Wide Web 9 ( 24 ): 82–94. http://french.chass.utoronto.ca/as-sa/ASSA-No24/index.html . Suche in Google Scholar

Enkvist N. E. 1964 . “ On Defining Style: An Essay in Applied Linguistics .” In Linguistics and Style , edited by J. Spencer . Oxford : Oxford University Press . Suche in Google Scholar

Erbay N. , and E.Özbek . 2013 . “ Mistik ve metafizik bağlamda bir yolculuk üçlemesi: ‘Hüsn Ü Aşk- Hacının Yolu- Simyacı’ .” Turkish Studies - International Periodical for the Languages, Literature and History of Turkish or Turkic 8 ( 1 ): 1355 – 1374 . Suche in Google Scholar

García J. D. 2009 . “ St. James the Moor-Slayer, a New Challenge to Spanish National Discourse in the Twenty-First Century .” International Journal of Iberian Studies 22 ( 1 ): 69 – 78 . doi: 10.1386/ijis.22.1.69/1 . Suche in Google Scholar

Genette G. 1997 . Palimpsests: Literature in the Second Degree . Translated by Channa Newman and Claude Doubinsky . Nebrasaka : University of Nebrasaka . Suche in Google Scholar

Göknar E. 2008 . “ The Novel in Turkish: Narrative Tradition to Nobel Prize .” In The Cambridge History of Turkey: Turkey in the Modern World , edited by R. Kasaba , 472 – 503 . New York : Cambridge University Press . 10.1017/CHOL9780521620963.018Suche in Google Scholar

Goodyear D. 2007 . “ The Magus: The Astonishing Appeal of Paulo Coelho .” The New Yorker - Life and Letters , May 07 . http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2007/05/07/the-magus . Suche in Google Scholar

Gürçağlar Ş. T. 2008 . The Politics and Poetics of Translation in Turkey, 1923-1960 . Amsterdam : Rodopi . 10.1163/9789401205306Suche in Google Scholar

Gürçağlar Ş. T. 2009 . “ The Muslim Call to Prayer in Turkish .” Archived radio broadcast by M. Zijlstra, July 11 2009. ABC Radio National, Australia . http://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/linguafranca/the-muslim-call-to-prayer-in-turkish/3060298 . Suche in Google Scholar

Halliday M. A. K. 1988 . “ Foreword to Functions of Style .” In Funtions of Style , edited by D. Birch and M.O’Toole . London : Pinter Publishers . Suche in Google Scholar

Halliday M. A. K. 1996 . “ Linguistic Function and Literary Style: An Inquiry into the Language of William Golding’s The Inheritors. .” In The Stylistics Reader: From Roman Jakobson to the Present , edited by J. J. Weber , 56 – 86 . London : Hodder Arnold . Suche in Google Scholar

Halliday M. A. K. , and R.Hasan . 1985 . Language, Context, and Text: Aspects of Language in a Social-semiotic Perspective . Melbourne, VIC : Deakin University . Suche in Google Scholar

Hart S. M. 2004 . “ Cultural Hybridity, Magical Realism, and the Language of Magic in Paulo Coelho’s The Alchemist .” Romance Quarterly 51 ( 4 ): 304 – 312 . doi: 10.3200/RQTR.51.4.304-312 . Suche in Google Scholar

Hasan R. 1989 . Linguistics, Language and Verbal Art . Oxford : Oxford University Press . Suche in Google Scholar

Hasan R. 1996 . “ The Nursery Tale as a Genre .” In Ways of Saying: Ways of Meaning: Selected Papers of Ruqaiya Hasan , edited by C. Cloran , D.Butt, and G.Williams , 51 – 72 . London : Cassell . Suche in Google Scholar

Hasan R. 2009 . “ Wanted: A Theory for Integrated Sociolinguistics .” In The Collected Works of Ruqaiya Hasan, Volume 2: Semantic Variation , edited by J. J. Webster , 5 – 40 . London : Equinox . Suche in Google Scholar

Hasan R. [1986] 2011 . “ The Implications of Semantic Distance for Language in Education .” In The Collected Works of Ruqaiya Hasan, Volume 3: Language and Education: Leaning and Teaching in Society , edited by J. J. Webster , 73 – 98 . Sheffield : Equinox . Suche in Google Scholar

Hatim B. , and I.Mason . 1997 . The Translator as Communicator . London : Routledge . Suche in Google Scholar

Herwaarden J. , W.Shaffer, and D.Gardner . 2003 . Between Saint James and Erasmus: Studies in Late-medieval Religious Life: Devotion and Pilgrimage in the Netherlands . Leiden : Brill . Suche in Google Scholar

Iʿrif Kanīsatak Iʿrif Lughatak: Qāmūs Al-Mu ṣṭ alahāt al-Kanasīyyah . Compiled by Tadars Malti . Cairo : Matbaat Al-Okhwah Al-Misriyyin , 1991 . Suche in Google Scholar

Ibrahim Y. R. 2013 . “ Riḥlatu al-Baḥthi ʿan al-Kanz bayna Bahaa Taher and Paulo Coelho .” Ḥawliyyāt ʼĀdāb Ain Shams 41 : 85 – 142 . Suche in Google Scholar

Kaadan A. N. , and S.Qawiji . n.d. “ Jābir Ibn Ḥayyān wa ʻilm al-khīmīyā’ (ʻilm al-ṣanʻah) .” International Society for the History of Islamic Medicine . http://www.ishim.net/ankaadan6/jaber.htm . Suche in Google Scholar

Lanzi F. , and G.Lanzi . 2004 . Saints and Their Symbols: Recognizing Saints in Art and in Popular Images . Minnesota : Liturgical Press . Suche in Google Scholar

Leech G. , and M.Short . 2007 . Style in Fiction: A Linguistic Introduction to English Fictional Prose . Harlow : Pearson Education . Suche in Google Scholar

Lewis G. 2000 . Turkish Grammar . 2nd ed. New York : Oxford University Press . Suche in Google Scholar

Malmkjær K. 2004 . “ Translational Stylistics: Dulcken’s Translations of Hans Christian Andersen .” Language and Literature 13 ( 1 ): 13 – 24 . doi: 10.1177/0963947004039484 . Suche in Google Scholar

Matthiessen C. M. I. M. 2001 . “ The Environments of Translation .” In Exploring Translation and Multilingual Text Production: Beyond Content , edited by E. Steiner and C.Yallop , 41 – 124 . Berlin : Mouton de Gruyter . Suche in Google Scholar

McCracken S. 1998 . Pulp: Reading Popular Fiction . Manchester : Manchester University Press . Suche in Google Scholar

Michel Jean-Baptiste , Yuan KuiShen, Aviva P.Aiden, AdrianVeres, Matthew K.Gray, Joseph P.Pickett, DaleHoiberg, DanClancy, PeterNorvig, JonOrwant, StevenPinker, Martin A.Nowak, and Erez LiebermanAiden 2010 . “ Quantitative Analysis of Culture Using Millions of Digitized Books .” Science . doi: 10.1126/science.1199644 . Suche in Google Scholar

Mongy Y. 2005 . “ Khuṭūṭun naqdīyyatun ḥamrā’ 2: Tajalliyyātu al-maʻrifati al-bāṭinīyyati fi [khīmyā’ī] Paulo Coelho: Al-adātu al-siḥrīyyatu ka-muḥarrikun li-fiʻli al-ishrāq .” Lucifer . Accessed January30 2005 . http://altculture.blogspot.com.au/2005_01_01_archive.html Suche in Google Scholar

Moore P. R. 1996 . “ Shakespeare’s Iago and Santiago Matamoros .” Notes and Queries 43 ( 2 ): 162 – 163 . doi: 10.1093/nq/43.2.162 . Suche in Google Scholar

Muʿjam al-Lughati al-ʿarabīyyati al-Muʿā ṣirah . Compiled by Ahmad Mukhtar Omar . Cairo : ʿālam Al-Kutub , 2008 . Suche in Google Scholar

Muhawi I. 2000 . “ Between Translation and the Canon: The Arabic Folktale as Transcultural Signifier .” Fabula 41 ( 1–2 ): 105 – 118 . doi: 10.1515/fabl.2000.41.1-2.105 . Suche in Google Scholar

Muraleedharan M. 2011 . “ Multi-Disciplinary Dimensions in Paulo Coelho’s Novel The Alchemist .” Journal of Literature, Culture and Media Studies 3 ( 5–6 ): 53 – 63 . Suche in Google Scholar

Nakagome P. T. 2014 . “ Hope or Literary Value: Different Keys to Read Literature .” Paper presented at the 6th Global Conference: Hope in the 21st Century , Prague , March 14–16 . Suche in Google Scholar

Nasr-Allah I. 1999 . “ Al-Riwāyatu wa al-rāwī 2: Sāḥiru al-Saḥrā’: Ḥīna tamḍī al-riwāyahtu bi-l-rāwī ilā arḍin taʻrifuhā .” Al-Jazirah Newspaper , March 18 . http://www.al-jazirah.com/1999/19990318/cu3.htm . Suche in Google Scholar

Nelson B. , and R.Wilson . 2013 . “ Perspectives on Translation .” Humanities Australia 4 : 35 – 43 . Suche in Google Scholar

O’Toole M. 1982 . Structure, Style and Interpretaion in the Russian Short Story . New Haven : Yale University Press . Suche in Google Scholar

Paker S. 2004 . “ Reading Turkish Novelists and Poets in English Translation: 2000–2004 .” Translation Review 68 ( 1 ): 6 – 14 . doi: 10.1080/07374836.2004.10523859 . Suche in Google Scholar

Perry G. E. 2004 . The History of Egypt . Westport : Greenwood Press . Suche in Google Scholar

Petrilli S. 1992 . “ Translation, Semiotics and Ideology .” TTR. Etudes sur le texte et ses transformations 5 ( 1 ): 233 – 264 . Suche in Google Scholar

Prince G. 2003 . Dictionary of Narratology . Lincoln : University of Nebrasaka Press . Suche in Google Scholar

Reiss K. [1971] 2000 . “ Type, Kind and Individuality of Text: Decision making in Translation .” In The Translation Studies Reader , edited by L. Venuti , 160 – 171 . London : Routledge . Suche in Google Scholar

Rimmon-Kenan S. [1983] 2002 . Narrative Fiction . London : Routledge . 10.4324/9780203426111Suche in Google Scholar

Saadany H. 2005 . “ A Study of the Concept of Transitivity in British English and Modern Standard Arabic: A Systemic Functional Approach .” PhD Diss. , Helwan University , Helwan . Suche in Google Scholar

Simpson P. 2004 . Stylisitcs: A Resource Book for Students . London : Routledge Taylor and Francis Group . 10.4324/9780203496589Suche in Google Scholar

Soni S. 2014 . “ Life Realized through Riddles: A Study of Paulo Coelho’s The Alchemist .” MIT International Journal of English Language & Literature 1 ( 2 ): 85 – 91 . Suche in Google Scholar

Sontag S. 2007 . “ The World as India: The St. Jerome Lecture on Literary Translation .” In At the Same Time: Essays and Speeches . London : Hamish Hamilton . Suche in Google Scholar

Spencer J. , and M.Gregory . 1964 . “ An Approach to the Study of Style .” In Linguistics and Style , edited by J. Spencer . Oxford : Oxford University Press . Suche in Google Scholar

Stone L. 2010 . “ Inside Turkish Literature: Concerns, References, and Themes .” Turkish Studies 11 ( 2 ): 235 – 250 . doi: 10.1080/14683849.2010.483864 . Suche in Google Scholar

Tiffany G. 2002 . “ Shakespeare and Santiago De Compostela .” Renascence 54 ( 2 ): 87 – 107 . doi: 10.5840/renascence200254221 . Suche in Google Scholar

Toolan M. 2001 . Narrative: A Critical Linguistic Introduction . London : Routledge . Suche in Google Scholar

Tooti A. 2006 . “ Al-Kīmyāī wa al-fikratu al-ṣifr .” Al-Warshah: Al-Haqiqah wa al-Wajh al-akhar . http://alwarsha.com/ . Suche in Google Scholar

Wilson R. 2007 . “ The Fiction of the Translator .” Journal of Intercultural Studies 28 ( 4 ): 381 – 395 . doi: 10.1080/07256860701591219 . Suche in Google Scholar

Yaktine S. 2005 . Taḥlīlu Al-Khiṭābi Al-Riwā’ī: Al-Zaman, Al-Sard, Al-Tabʼīr . Casabalnca & Beirut : Al-Markaz Al-Thaqāfī Al-ʿarabī . Suche in Google Scholar

Yaktine S. 2006 . Infitāḥu al-Naṣṣi al-Riwā’ī . Casablanca & Beirut : Al-Markaz Al-Thaqāfī Al-ʻarabī . Suche in Google Scholar

© 2016 Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Editorial

- Translation across time in East and West encounters: an overview

- Article

- Doing translation history and writing a history of translation: the main issues and some examples concerning Portuguese culture

- Translating erased history: Inter-Asian translation of the national Changgeuk company of Korea’s Romeo and Juliet

- From the Far East to the Far West. Portuguese Discourse on Translation: A case study of Camilo Pessanha

- Translating politeness cues in Philippine missionary linguistics: “Hail, Mister Mary!” and other stories

- Translating otherness: images of a Chinese city

- Narrative structure, context and translation in Paulo Coelho’s O Alquimista in English, Arabic and Turkish

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Editorial

- Translation across time in East and West encounters: an overview

- Article

- Doing translation history and writing a history of translation: the main issues and some examples concerning Portuguese culture

- Translating erased history: Inter-Asian translation of the national Changgeuk company of Korea’s Romeo and Juliet

- From the Far East to the Far West. Portuguese Discourse on Translation: A case study of Camilo Pessanha

- Translating politeness cues in Philippine missionary linguistics: “Hail, Mister Mary!” and other stories

- Translating otherness: images of a Chinese city

- Narrative structure, context and translation in Paulo Coelho’s O Alquimista in English, Arabic and Turkish