Abstract

Background and aims

Systematic and regular pain assessment has been shown to improve pain management. Well-functioning pain assessments require using strategies informed by well-established theory. This study evaluates documented pain assessments reported in medical records and by patients, including reassessment using a Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) after patients receive rescue medication.

Methods

Documentation surveys (DS) and patient surveys (PS) were performed at baseline (BL), after six months, and after 12 months in 44 in-patient wards at the three hospitals in Östergötland County, Sweden. Nurses and nurse assistants received training on pain assessment and support. The Knowledge to Action Framework guided the implementation of new routines.

Results

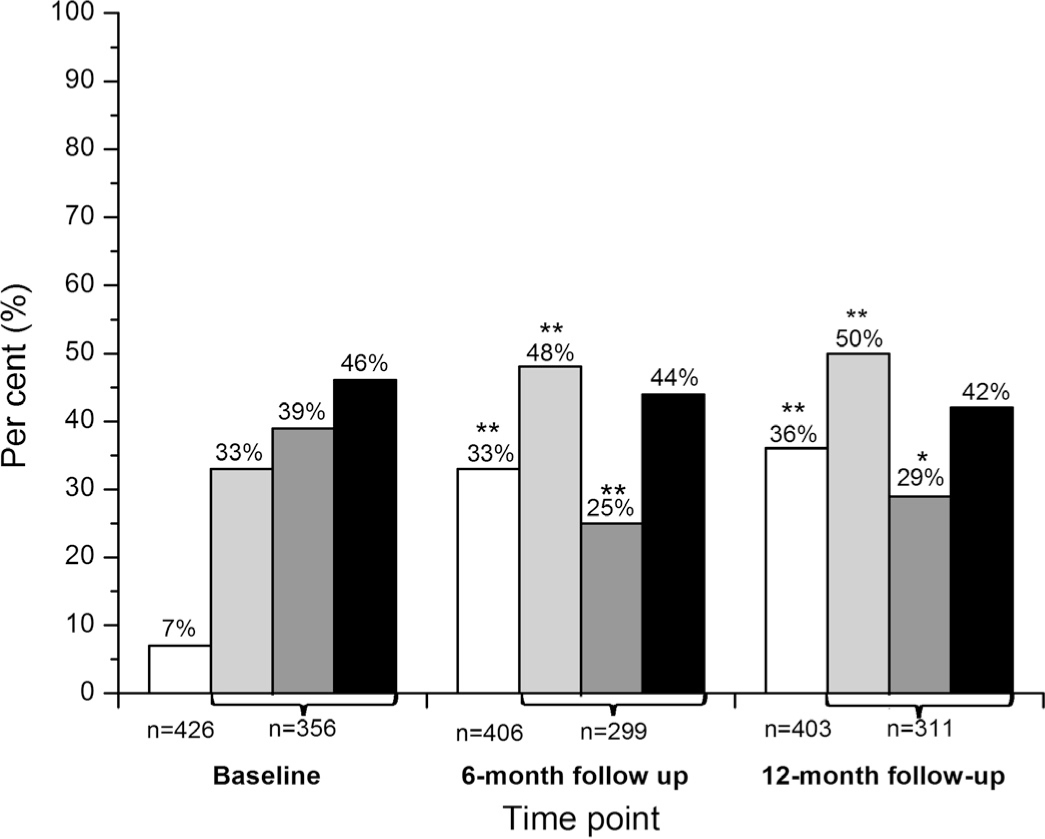

According to DS pain assessment using NRS, pain assessment increased significantly: from 7% at baseline to 36% at 12 months (p < 0.001). For PS, corresponding numbers were 33% and 50% (p < 0.001). According to the PS, the proportion of patients who received rescue medication and who had been reassessed increased from 73% to 86% (p = 0.003). The use of NRS to document pain assessment after patients received rescue medication increased significantly (4% vs. 17%; p < 0.001).

Conclusions

After implementing education and support strategies, systematic pain assessment increased, an encouraging finding considering the complex contexts of in-patient facilities. However, the achieved assessment levels and especially reassessments related to rescue medication were clinically unsatisfactory. Future studies should include nursing staff and physicians and increase interactivity such as providing online education support. A discrepancy between documented and reported reassessment in association with given rescue medication might indicate that nurses need better ways to provide pain relief.

Implications

The fairly low level of patient-reported pain via NRS and documented use of NRS before and 12 months after the educational programme stresses the need for education on pain management in nursing education. Implementations differing from traditional educational attempts such as interactive implementations might complement educational programmes given at the work place. Standardized routines for pain management that include the possibility for nurses to deliver pain medication within well-defined margins might improve pain management and increase the use of pain assessments. Further research is needed that examines the large discrepancy between patient-reported pain management and documentation in the medical recording system of transient pain.

1 Introduction

In modern health care, effectively controlling pain using pharmacological methods requires establishing standardized procedures to assess pain recommended in clinical guidelines. The need for high quality pain assessment is reflected in the high prevalence of severe pain in hospital patients [1,2,3].

Effective pain management improves recovery from cancer, surgery, and trauma [4,5,6] and decreases the risk of developing chronic back pain [7]. Compared to hospitalized patients in the USA hospitalized patients in Europe are less likely to undergo daily pain assessments [8,9,1]. A Swedish study on nursing documentation of postoperative pain management found that 60% of patients did not have their pain assessed using pain assessment tools and fewer than 10% had their pain assessed at least once a shift [10].

Although systematic and regular pain assessment has been shown to improve pain management [8,11,12], pain assessment does not always lead to better pain management [13,14,15]. To increase the use of systematic pain assessments, implementation of pain assessment routines should include staff education, participation, support, and feedback [16]. In addition, well-functioning pain assessment routines should be informed by well-developed theories such as action research theory [17,18].

If patients require additional pain relief medication, they should be reassessed and this reassessment should be documented [19]. There are two main types of transient exacerbation of pain: breakthrough pain (BTP) and episodic pain [20]. BTP is exacerbation of pain that occurs spontaneously or in response to a trigger [21] on a pain background and episodic pain is intermittent pain that occurs on a pain-free background [22]. Although transient exacerbation of pain is often managed with supplemental doses of analgesic rescue medications [19,20], health care professionals need more knowledge about transient pain such as BTP [23,24,25].

To this end, this study investigates the outcomes of implementation of new pain assessment routines established in an education and support programme for nurses and nurse assistants. These nurses and nurse assistants were working in in-patient wards of three hospitals located in Östergötland County, Sweden. To evaluate the outcomes of pain assessment routines, this study gathered data from medical records and a short patient questionnaire. The aim of this study was to answer the following questions:

Did an educational programme and support for nurses and assistant nurses change the use of a Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) and other pain assessment instruments/scales?

Did the frequency of pain assessment and of documentation concerning pain in the medical records improve as a consequence of the education and support programme?

Did the pain assessments and documentation in the medical records after receiving pain rescue medication improve as a consequence of the education and support programme?

2 Material and methods

2.1 Procedures and design

In 2012, the research group received information about pain assessment routines primarily through regular contact with the Pain Resource Nurses (PRNs) for the three hospitals in Östergötland County. The PRNs serve as both a resource and change agents in disseminating information, interfacing with nurses, physicians, other members of the health care team, patients and families to facilitate quality pain management [26]. The information the PRNs provided included shortcomings and the main barriers to the implementation of regular pain assessment (i.e., lack of time, knowledge, assessment routines, and documentation as well as ongoing quality improvement studies and high turnover of staff). This information forms the base for the design of this study. As a result of this information, new pain assessment routines established in an education and support programme for nurses and nurse assistants at in-patient wards were implemented. We evaluated the situation at baseline (BL) (i.e., before implementation of the programme), at the six-month follow-up (FU-6m), and at the twelve-month follow-up (FU-12m). These data were collected using a documentation survey of the medical records (DS) and a patient survey (PS).

2.2 Implementation model

This study was guided by the Knowledge to Action framework (KTA) [27]. In the KTA framework, knowledge creation is described in terms of knowledge inquiry, knowledge synthesis, and knowledge tools/products. The KTA includes the following action steps: identify the problem; identify, review, and select knowledge; adapt knowledge to local context; assess barriers to knowledge use; select, tailor, and implement interventions; monitor knowledge use; evaluate outcomes; and sustain knowledge use.

2.3 Intervention

Between the BL and the FU-6m, the first author (AP) and a research nurse met with nurses and nurse assistants to inform them about the new pain assessment routines. To reach as many nurses and assistant nurses as possible, this informational and educational meeting was offered three times – two months in-between each meeting – at each ward (Fig. 1). Before the first two information and education meetings, all the nurses and nurse assistants at each hospital received an e-mail that described the project and invited them to participate (Fig. 1). Because the meetings coincided with the regular staff meetings, the new pain assessment routines were adapted to the local context. Several unit care managers suggested that the PRNs should conduct the third meeting to facilitate the implementation of routines. The PRNs also served as advisers, providing support for the new routines, encouraging the use of pain assessment and documentation, and setting a good example for the nurses and assistant nurses. In addition, the PRNs repeated the new routines during workplace meetings and supervised new and temporary employees regarding pain assessment routines.

Flowchart of implementation activities directed to heads of the wards, supporting nurses, nurses, and assistant nurses. PPP, PowerPoint presentation; BL, baseline.

The first author (AP), the research nurse, and the PRNs (the second repetition = third education and information meeting) used a PowerPoint presentation to introduce the study’s purpose and to provide education on pain and pain assessment.

The presentation included data that addressed the importance of relieving patient pain as for example post-operative pain can lead to complications such as pneumonia, myocardial infarction, and chronic pain conditions. The presentation therefore stressed that avoiding complications and alleviating suffering requires assessing pain using standardized pain assessment and documentation routines. NRS was selected as the pain assessment tool to been primarily used because it is easy to use in clinical practice, it is preferred by patients and health professionals [28], and it is frequently followed-up by phone. The NRS consists of rating the pain on a visual or imagined 11-point scale with the endpoints 0 (no pain) and 10 (worst pain imaginable), a design that makes followup easy and consistent. The presentation demonstrated how to use the NRS and emphasized that such pain assessment should be performed at least once per work shift (i.e., three times per 24 h) as well as before and after administering rescue medication for transient pain. The presentation also detailed how to document pain assessment using the electronic medical recording system, which had been recently adapted for the study and for the local contexts of each clinical department. At the end of the meeting, the ward-specific outcomes of the two BL surveys (i.e., DS and PS), which had been performed five to six weeks before the first meeting, were discussed. Finally, to clarify barriers for the new routines and to adapt the new routines to the local context and thereby facilitate their use, the nurses and nurse assistants were encouraged to discuss the advantages and disadvantages of the new pain assessment routines. To further ensure the use of the new routines, the PowerPoint presentation was e-mailed to all nurses and nurse assistants one week after the meetings. Three weeks later a reminder of the study was e-mailed to the nurses and nurse assistants to encourage the use of the new routines. As part of the implementation strategy, a poster was displayed in the staff room of each ward. When the project started, some information was provided on the Intranet; after six months, this information was supplemented with a short movie that reminded the nurses and nurse assistants of the project, including the NRS assessment. Information of the progress of the project was continuously delivered via the clinical departments’ Intranet.

Ten to 15 nurses attended each education session. In total, about 1200 nurses and nurse assistants participated in the educational programme.All eligible nurses and assistant nurses (approximately 2000) received the educational programme on two occasions in the form of PowerPoint presentation.

2.4 Setting and sample

Forty-four in-patient wards at the three hospitals (in Linköping, Norrköping, and Motala) of Östergötaland County participated in the study (Table 1). These hospitals are responsible for certain geographical areas of Östergötland. In addition, the hospital in Linköping is a university hospital, so it is responsible for research, health care education, and the most highly specialized care.

Medical specialities of the 44 in-patient wards that participated in the study.

| Surgical specialty (N = 18) | Number of wards | Non-surgical specialty (N = 26) | Number of wards |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ear, nose, and throat | 1 | Cardiology | 3 |

| Ophthalmology | 1 | Endocrine gastro intestinal | 1 |

| General surgery | 4 | General medical | 2 |

| Gynaecological | 2 | Geriatric | 3 |

| Hand and plastic surgery | 1 | Haematologist | 2 |

| Neurosurgical | 1 | Infectious | 2 |

| Orthopaedics | 5 | Intensive care | 4 |

| Thoracic surgical | 1 | Medical emergency | 1 |

| Urology | 1 | Neurological | 3 |

| Vascular surgery | 1 | Oncology | 1 |

| Pulmonary medical | 2 | ||

| Rehabilitation medicine | 1 | ||

| Renal medical medicine | 1 | ||

| Total | 18 | 26 |

Only three in-patient wards did not participate: the psychiatric wards (protected medical records), the emergency wards (short periods of care), and the paediatric wards (NRS is not applicable for children). Thus, this is a total study as it comprises most of the wards of the three included hospitals. No control wards was included in this study which was part of an ongoing quality assurance programme. All wards had at least one experienced PRN as part of their regular health care staff. Each unit care manager and the PRNs received information by e-mail on why and when (predetermined by the project leader) the new pain assessment routines would be implemented. The information also included instructions on how to complete the DS and how to distribute and inform the participants about the PS. The e-mail also included information about the upcoming intervention (i.e., information about the educational programme and about support for nurses and assistant nurses).

2.5 Measurements

The identifying and tailoring phases of the KTA were created using a documentation survey (DS) and a patient survey (PS) (Fig. 1). Hence, data were obtained both from the electronical medical records of all patients enrolled in the in-patient wards and from a brief paper survey concerning pain assessments answered by enrolled patients. To avoid bias, the DS was always answered one week before the PS.

The first author (AP), a research nurse, and ten PRNs created a pilot DS and PS. These pilot surveys were completed by five randomly selected nurses and five randomly selected patients completed. These participants provided verbal feedback about the surveys. Using this information and consensus discussions, we revised the surveys. This procedure was done twice before consensus was reached. The final DS included the items on current documentation on pain assessment in medical records (Table 2), and in the final PS the first question was: Have you experienced any pain during the hospitalisation period (yes/no)? The patients who answered “yes” were asked to answer four items on pain assessment for the previous 24 h (Table 2). According to KTA model, the PRNs were provided with a checklist regarding distribution and collection of surveys and the nurses were asked to inform the patients that their identity would be protected and their participation was voluntary (Fig. 1).

The items and answering alternatives for the patient (PS) and documentation (DS) surveys.

|

Patient survey (PS)

Documentation survey (DS)

|

2.6 Data collection

DS was used to document pain in all medical records the previous 24 h. A PRN in each ward completed the DS, which included four items (Table 2). Thus, the medical records of the patients who were enrolled in the ward were only reviewed by the predetermined PRN. One week after the DS, all patients competent in written and spoken Swedish and who were enrolled at a certain ward were asked to complete the PS. The PRN distributed and collected the PS (Fig. 1). Both the DS and PS were repeated at the two followups (FU-6m and FU-12m) using the same procedures. The two BL surveys were completed in November 2012.

2.7 Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS statistical programme for Windows (version 21.0). Descriptive statistics (%, mean±sd) are reported for outcomes. The Chi-square test was used to compare distribution between groups. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

3 Results

Using the DS, we surveyed the medical records of 2002 patients (BL: n = 687; FU-6m: n = 644; and FU-12m: n = 671). At all three time points, the mean age of these patients was 68±18 years. The PS was completed by 1432 patients (BL: n = 508; FU-6m: n = 467; and FU-12m: n = 457). The mean ages of these patients were 66±17 (BL), 67±17 (FU-6m), and 68±18 (FU-12m) years. The majority of these patients reported pain during hospitalization (BL: 70%; FU- 6m: 64%; and FU-12m: 68%). The corresponding figures from the DS were 62%, 63%, and 60%.

3.1 Use of NRS, other pain assessments, and frequency of assessment

According to the DS and PS, the percentage of patients who underwent pain assessment using the NRS increased significantly from BL to the follow-ups (Fig. 2). According to the PS, the percentage of patients who had been asked about current pain but who had not been asked to rate their pain intensity using a pain assessment scale/instrument decreased significantly. In addition, no significant changes were found from BL to the follow-ups for patients asked to rate their pain ≥3 times during the previous 24 h.

Changes in the use of NRS, in other pain assessments, and in frequency of assessment. PS only included those patients who reported any pain during the hospital period. White bars: pain assessment by NRS (DS). Light grey bars: pain assessment by NRS (PS). Dark grey bars: percentage of patients asked about current painbut not asked to use a pain assessment scale (PS). Black bars: percentage of patients asked about pain ≥3 times during the previous 24 h (PS). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.001.

3.2 Pain assessment and reassessment after rescue medication

According to the DS, the percentage of patients who received rescue medication was 32% for BL, 35% for FU-6m, and 34% for FU-12m. The corresponding figures for PS were 41%, 34%, and 49%. In the DS, transient pain (requiring rescue medicine) was operationally defined by the answer “yes” for the items in rescue medicine. In the PS, treatment of transient pain was defined as “yes” for the items in extra medicine.

According to the DS, the use of NRS after receiving rescue medication increased significantly at both follow-ups (Fig. 3). This increase was also the case for pain assessments with any pain assessments scale/instrument at all, including NRS. The percentage of patients who received rescue medication and who had been asked (PS) (not specifically with a pain assessment scale/instrument) if the medication alleviated the pain appropriately had increased significantly at the FU-12m. The percentage of patients with pain who had received rescue medication and who also had been asked (PS) (not specifically with a pain assessment scale/instrument) to inform the nurses or nurse assistants if the medication did not alleviate the pain in an appropriate way was unchanged at the follow-ups.

Changes of pain assessment and reassessment after rescue medication. White bars: pain assessments using NRS after receiving rescue medication (DS). Light grey bars: pain assessments with any pain assessments scale/instrument at all including NRS (DS). Dark grey bars: the percentage of patients (with pain previous 24 h) who received rescue medication and who had been asked (not specifically by the use of pain assessment scale/instrument) if the medication alleviated the pain appropriately (PS). Black bars: the percentage of patients (with pain previous 24 h) who had received rescue medication and who also had been asked (not specifically by the use of pain assessment scale/instrument) to inform the nurses or nurse assistants if the medication did not alleviate the pain in an appropriate way (PS). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.001.

4 Discussion

The majority of patients had pain and three important results were found:

Pain assessments using NRS or any other pain assessment scale/instrument increased significantly according to both surveys at FU-6m and FU-12m.

The documentation of reassessment after receiving rescue medication remained low.

A large discrepancy between management and documentation of transient pain was found.

As with our results, previous studies show that using NRS [29] and assessments similar to the NRS [30,18,31,32] with an education programme improve how nurses assess and document pain. Given the low level of documented use for NRS at BL in our study, the increase of about one-third of the patients assessed by NRS at FU-6m and FU-12m is encouraging since these changes represent behavioural changes in the complex contexts of in-patient facilities. However, we consider the results at FU-12m (DS: 36% and PS: 50%) too low from a clinical perspective although repeated education and support sessions might improve this unsatisfactory situation. These educational sessions are resource demanding although nontraditional educational strategies can be successful. For example, an interactive implementation programme in an oncology ward improved the use of a pain assessment tool from 50% to 83%, and patient’s records that documented pain increased from 29% to 75% [33].

In our study, nearly half of the patients reported that they had been asked about their pain but not asked to rate their pain using any instrument. This finding suggests that the health care providers attended to the patient’s pain, although the use of an assessment tool and the documentation of pain level may have helped optimize care.

The DS showed that evaluation of rescue medication with NRS was rarely performed at BL. Pain assessments using NRS had increased significantly at the two follow-ups but was still low (DS: 15% and 17%), and these results are in line with a study conducted in an emergency department of a university hospital [34]. In that study, 698 randomly selected medical records showed a surprising lack of documentation regarding pain assessments, pain treatments, and follow-ups. Such a result was also found in a study of emergency departments [35], a finding attributed to the format of the record keeping, a procedure that made it difficult to consistently document pain assessments. In the present study, it was not possible to differentiate between transient types of pain – i.e., BTP and episodic pain–because the source of the results regarding transient medication were nonspecific regarding the type of pain but focused on rescue medication received. In a large European study of 1241 nurses, less than half used any pain assessment instruments associated with BTP before medication, and many of these nurses found it difficult to differentiate between background pain and BTP [24]. On the other hand, another study reported that a minority of nurses did not use pain assessment tools in association with BTP in cancer patients, but the majority of nurses who used pain assessment tools found them useful [25]. Although nurses may have general knowledge of principles of pain management, they may lack opportunities to give efficient pain medications because of medico-legal requirements. This situation might interfere with the nurse’s motivation to reassess and document the outcome of pain medication (e.g., rescue medication). Implementation of standardized routines for post-operative pain management that include the possibility for the nurses to deliver pain medication within well-defined margins reduced the need for nurses to contact physicians, decreased pain intensity of patients, increased the number of pain assessments, and improved the knowledge of the nursing staff [36]. Moreover, physicians who proactively prescribe adequate analgesia enable nurses to deliver continual pain relief without consulting the physician, a finding also identified in a study that aimed to identify barriers, enablers, and current nursing knowledge regarding pain management [37]. Alternatively, nurses could regard some aspects of nursing care (e.g., reassessment after rescue medication) so fundamental that they do not even bother to document their actions [38]. The importance of reassessment documentation was shown in a model of pain severity development [39]. According to the model, the reassessment documentation within one hour of an intervention and the type of surgical procedure affected pain development. An aggregated proportion of 95% properly documented pain re-examinations was reached by application of a large-scale plan-do-check-act documentation of pain re-examinations and with improved evidence-based organisational policy, repetitive teaching meetings with bedside training, alterations in daily bedside records, and response [40].

Transient pain requires the reassessment of pain after giving rescue medication (e.g., according to the guidelines developed by the European Oncology Nursing Society for pain management in cancer patients) [41]. Unfortunately, our results show that the reassessment after giving rescue medication remained deficient despite the project’s repetitive efforts, which included education and support.

The results of the PS showed that the proportion of patients who were asked if rescue medication had helped was already high at BL and remained high at follow-ups. Thus, our results show a discrepancy between action of pain management and documentation in the medical records. Similar results were reported in a study using focus group interviews with nursing staff; only one-third of the patients who had experienced problems were documented in the medical records and the nursing staff had more knowledge than was documented [42]. A similar discrepancy between knowledge and documentation was reported by an academic primary clinic [43]. The nurses in our study might have had more knowledge about the patient’s reports of the effect of rescue medication than was documented. On the other hand, a study that assessed the agreement between data retrieved from interviews with nurses and data from electronic medical records found that majority of the assessed variables (pain, dyspnoea, nausea, and treatment variables) ranged from moderate to good levels of agreement [44].

The KTA framework proved to be valuable as it informed the implementation process. However, the KTA framework does not provide details about how to tailor the implementation strategies and other sources were also used. The implementation in this large study concerned three hospitals and different types of wards. Furthermore, the drop-out rates were small for DS and relatively small for PS, which may indicate generalizability. The internal validity may have been affected by the fact that the survey questions were self-formulated and not validated. The questions, however, were designed and adapted based on repeated feedback from staff and patients, and explanations of possibly unfamiliar terms and concepts were thoroughly provided with text and pictures.

Since pain is a subjective experience, it is unclear how the participants with widely varying underlying causes of hospitalization perceived the word “pain”, which occurred several times in the PS. The initial question about pain during hospitalization may allow for responses that consider other dimensions, such as anxiety. Patients who had received long-term treatment on the ward may have underestimated their pain if they only experienced pain on a single occasion during their hospital stay.

We do not know how well informed PRNs were about the DS survey questions and how carefully the medical records were read. Motivation and time limitations may certainly come into play. However, PRNs received in advance a detailed checklist about distribution and collection of PS as well as the procedure for completing the DS. All 44 PRNs responsible for the data collection from the medical records using DS registered the required data without asking for support from project staff and the surveys were collected at the right time. We therefore assume that the PRNs did not experience difficulty in understanding the questions in the DS or in distributing the PS. However, the fact that the PRNs helped implement the intervention and then collected data is a limitation of the study. It was important to conduct the surveys on predetermined and different days known only to the project management and PRNs since the two surveys were intended to reflect the most common pain assessments and their documentation. We assume that the information given to the PRNs before the start of the project was sufficiently clear concerning this issue. Undoubtedly, this study is built on the project management having great confidence in the professionalism of the PRNs.

Only the nurses and assistant nurses who were on duty and had time to attend the meeting were given the verbal training. To reduce the impact of missed training, the training was repeated twice on each ward. Unfortunately, we do not know in detail what proportion of staff received the verbal training. On the other hand, the PowerPoint files from the verbal training were e-mailed to all nurses and assistant nurses employed on the participating wards. Moreover, the educational component was limited and might have been improved with the use of more interactivity such as online support. In addition, due to financial constraints, physicians were not included in this study.

5 Conclusions

The implementation of the new pain assessment protocol resulted in significant behavioural improvements. That is, systematic pain assessment increased, which is encouraging when considering the complex contexts of wards. However, the assessment levels, especially reassessment related to rescue medication, were not satisfactory from a clinical perspective. To improve the results, it may be necessary to include the physicians working at the wards and to increase the interactivity and support for the education component. The discrepancy between documented and reported transient pain might indicate a need to change the way nurses provide pain relief.

Implications

The fairly low level of patient-reported and documented use of NRS before and 12 months after the educational programme stresses the need for education on pain management in nursing education. Non-traditional educational strategies such as interactive implementations might complement educational programmes given at the work place. Standardized routines for pain management that include the possibility for nurses to deliver pain medication within well-defined margins might increase pain management and the use of pain assessments. The large discrepancy between patient-reported transient pain management and documentation in the medical recording system of transient pain needs further study.

Ethical issues

Collection of the data was part of the on-going quality assurance programme of the hospitals, so it constituted part of the routine medical records and patient monitoring system. The study was approved by the director of the County Council and by the heads of the clinical departments. The researchers carefully trained the PRNs on principles of clinical research. They were informed verbally and in writing about ethical guidelines set for medical research.

Verbal and written information about the quality assurance programme was given to all eligible patients. This information stressed that participation was voluntary and that non-participation did not affect present or future treatment and promised anonymity. Informed verbal consent was obtained from all patients that participated in the study. The informed consent was verbal; that is, the PRNs believed that the participating patients understood their rights and the aim of the study. All data were secured in locked archives and all possible identifications were deleted before analyses. Hence, the ethical guidelines set for medical research by the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki [45] were followed.

Highlights

Systematic pain assessment in wards increased after an education programme and support.

However, the pain assessment levels were not satisfactory.

The discrepancy between documented and reported transient pain should be decreased.

Interactive implementations might complement educational programmes at the work place.

DOI of refers to article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.sjpain.2017.04.004.

-

Funding: This study was supported by a grant from the research funds of the Östergöland County Council. The funder had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, preparation of the manuscript, or decision to publish.

-

Conflict of interest: None.

References

[1] Wadensten B, Frojd C, Swenne CL, Gordh T, Gunningberg L. Why is pain still not being assessed adequately? Results of a pain prevalence study in a university hospital in Sweden. J Clin Nurs 2011;20:624–34.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Visentin M, Zanolin E, Trentin L, Sartori S, de Marco R. Prevalence and treatment of pain in adults admitted to Italian hospitals. Eur J Pain 2005;9:61–7.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Jabusch KM, Lewthwaite BJ, Mandzuk LL, Schnell-Hoehn KN, Wheeler BJ. The pain experience of inpatients in a teaching hospital: revisiting a strategic priority. Pain Manag Nurs 2015;16:69–76.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Costantini R, Affaitati G, Fabrizio A, Giamberardino MA. Controlling pain in the post-operative setting. Int J Clin Pharmacol Therap 2011;49:116–27.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Lewis KS, Whipple JK, Michael KA, Quebbeman EJ. Effect of analgesic treatment on the physiological consequences of acute pain. Am J Hosp Pharm 1994;51:1539–54.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Sinatra R. Causes and consequences of inadequate management of acute pain. Pain Med 2010;11:1859–71.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Valat JP, Goupille P, Rozenberg S, Urbinelli R, Allaert F. Acute low back pain: predictive index of chronicity from a cohort of 2487 subjects. Spine Group of the Societe Francaise de Rhumatologie. Joint Bone Spine 2000;67:456–61.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Purser L, Warfield K, Richardson C. Making pain visible: an audit and review of documentation to improve the use of pain assessment by implementing pain as the fifth vital sign. Pain Manag Nurs 2014;15:137–42.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Zoega S, Ward SE, Sigurdsson GH, Aspelund T, Sveinsdottir H, Gunnarsdottir S. Quality pain management practices in a university hospital. Pain Manag Nurs 2015;16:198–210.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Idvall E, Ehrenberg A. Nursing documentation of postoperative pain management. J Clin Nurs 2002;11:734–42.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Silva MA, Pimenta CA, Cruz Dde A. Pain assessment and training: the impact on pain control after cardiac surgery. Revista da Escola de Enfermagem da U S P 2013;47:84–92.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Anwar ul H, Hamid M, Baqir M, Almas A, Ahmed S. Pain assessment and management in different wards of a tertiary care hospital. JPMA 2012;62:1065–9.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Chapman CR, Stevens DA, Lipman AG. Quality of postoperative pain management in American versus European institutions. J Pain Palliative Care Pharmacotherapy 2013;27:350–8.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Nworah U. From documentation to the problem: controlling postoperative pain. Nursing Forum 2012;47:91–9.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Wells N, McDowell MR, Hendricks P, Dietrich MS, Murphy B. Cancer pain management in ambulatory care: can we link assessment and action to outcomes? Supportive Care Cancer 2011;19:1865–71.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Ista E, van Dijk M, van Achterberg T. Do implementation strategies increase adherence to pain assessment in hospitals? A systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud 2013;50:552–68.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Bourbonnais FF, Perreault A, Bouvette M. Introduction of a pain and symptom assessment tool in the clinical setting – lessons learned. J Nurs Manag 2004;12:194–200.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Simons J, MacDonald LM. Changing practice: implementing validated paediatric pain assessment tools. J Child Health Care 2006;10:160–76.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Zeppetella G. Impact and management of breakthrough pain in cancer. Curr Opin Support Palliative Care 2009;3:1–6.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Zeppetella G, Ribeiro MD. Opioids for the management of breakthrough (episodic) pain in cancer patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006:Cd004311.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Davies AN, Dickman A, Reid C, Stevens AM, Zeppetella G. The management of cancer-related breakthrough pain: recommendations of a task group of the Science Committee of the Association for Palliative Medicine of Great Britain and Ireland. Eur J Pain 2009;13:331–8.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Haugen DF, Hjermstad MJ, Hagen N, Caraceni A, Kaasa S. Assessment and classification of cancer breakthrough pain: a systematic literature review. Pain 2010;149:476–82.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Rhiner MI, von Gunten CF. Cancer breakthrough pain in the presence of cancer-related chronic pain: fact versus perceptions of health-care providers and patients. J Supportive Oncol 2010;8:232–8.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Rustoen T, Geerling JI, Pappa T, Rundstrom C, Weisse I, Williams SC, Zavratnik B, Wengstrom Y. How nurses assess breakthrough cancer pain, and the impact of this pain on patients’ daily lives – results of a European survey. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2013;17:402–7.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Fitch MI, McAndrew A, Burlein-Hall S. A Canadian online survey of oncology nurses’ perspectives on the defining characteristics and assessment of break-through pain in cancer. Can Oncol Nurs J 2013;23:85–99.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Crawford CL, Boller J, Jadalla A, Cuenca E. An integrative review of pain resource nurse programs. Crit Care Nurs Quarterly 2016;39:64–82.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Graham ID, Logan J, Harrison MB, Straus SE, Tetroe J, Caswell W, Robinson N. Lost in knowledge translation: time for a map? J Contin Educ Health Prof 2006;26:13–24.Search in Google Scholar

[28] Yazici Sayin Y, Akyolcu N. Comparison of pain scale preferences and pain intensity according to pain scales among Turkish Patients: a descriptive study. Pain Manag Nurs 2014;15:156–64.Search in Google Scholar

[29] de Rond M, de Wit R, van Dam F. The implementation of a Pain Monitoring Programme for nurses in daily clinical practice: results of a follow-up study in five hospitals. J Adv Nurs 2001;35:590–8.Search in Google Scholar

[30] Zhang CH, Hsu L, Zou BR, Li JF, Wang HY, Huang J. Effects of a pain education program on nurses’ pain knowledge, attitudes and pain assessment practices in China. J Pain Symptom Manage 2008;36:616–27.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Phelan C. An innovative approach to targeting pain in older people in the acute care setting. Contemp Nurse 2010;35:221–33.Search in Google Scholar

[32] Ger LP, Chang CY, Ho ST, Lee MC, Chiang HH, Chao CS, Lai KH, Huang JM, Wang SC. Effects of a continuing education program on nurses’ practices of cancer pain assessment and their acceptance of patients’ pain reports. J Pain Symptom Manage 2004;27:61–71.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Ang E, Chow YL. General pain assessment among patients with cancer in an acute care setting: a best practice implementation project. Int J Evid Based Healthc 2010;8:90–6.Search in Google Scholar

[34] Lewen H, Gardulf A, Nilsson J. Documented assessments and treatments of patients seeking emergency care because of pain. Scand J Caring Sci 2010;24:764–71.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Todd KH, Ducharme J, Choiniere M, Crandall CS, Fosnocht DE, Homel P, Tanabe P. Pain in the emergency department: results of the pain and emergency medicine initiative (PEMI) multicenter study. J Pain 2007;8:460–6.Search in Google Scholar

[36] Erlenwein J, Studer D, Lange JP, Bauer M, Petzke F, Przemeck M. Process optimization by central control of acute pain therapy: implementation of standardized treatment concepts and central pain management in hospitals. Anaesthesist 2012;61:971–83.Search in Google Scholar

[37] Pretorius A, Searle J, Marshall B. Barriers and enablers to emergency department nurses’ management of patients’ pain. Pain Manag Nurs 2015;16:372–9.Search in Google Scholar

[38] Frank-Stromborg M, Christensen A, Do DE. Nurse documentation: not done or worse, done the wrong way – Part II. Oncol Nurs Forum 2001;28:841–6.Search in Google Scholar

[39] Samuels JG, Eckardt P. The impact of assessment and reassessment documentation on the trajectory of postoperative pain severity: a pilot study. Pain Manag Nurs 2014;15:652–63.Search in Google Scholar

[40] Gordon DB, Rees SM, McCausland MR, Pellino TA, Sanford-Ring S, Smith-Helmenstine J, Danis DM. Improving reassessment and documentation of pain management. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2008;34:509–17.Search in Google Scholar

[41] Wengstrom Y, Geerling J, Rustoen T. European Oncology Nursing Society break-through cancer pain guidelines. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2014;18:127–31.Search in Google Scholar

[42] Adamsen L, Tewes M. Discrepancy between patients’ perspectives, staff’s documentation and reflections on basic nursing care. Scand J Caring Sci 2000;14:120–9.Search in Google Scholar

[43] Krebs EE, Bair MJ, Carey TS, Weinberger M. Documentation of pain care processes does not accurately reflect pain management delivered in primary care. J Gen Intern Med 2010;25:194–9.Search in Google Scholar

[44] Steindal SA, Sorbye LW, Bredal IS, Lerdal A. Agreement in documentation of symptoms, clinical signs, and treatment at the end of life: a comparison of data retrieved from nurse interviews and electronic patient records using the Resident Assessment Instrument for Palliative Care. J Clin Nurs 2012;21:1416–24.Search in Google Scholar

[45] World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013, 310:2191-4.Search in Google Scholar

© 2017 Scandinavian Association for the Study of Pain

Articles in the same Issue

- Scandinavian Journal of Pain

- Editorial comment

- Glucocorticoids – Efficient analgesics against postherpetic neuralgia?

- Original experimental

- Effect of intrathecal glucocorticoids on the central glucocorticoid receptor in a rat nerve ligation model

- Editorial comment

- Important new insight in pain and pain treatment induced changes in functional connectivity between the Pain Matrix and the Salience, Central Executive, and Sensorimotor networks

- Original experimental

- Salience, central executive, and sensorimotor network functional connectivity alterations in failed back surgery syndrome

- Editorial comment

- Education and support strategies improve assessment and management of pain by nurses

- Clinical pain research

- Using education and support strategies to improve the way nurses assess regular and transient pain – A quality improvement study of three hospitals

- Editorial comment

- The interference of pain with task performance: Increasing ecological validity in research

- Original experimental

- The disruptive effects of pain on multitasking in a virtual errands task

- Editorial comment

- Analyzing transition from acute back pain to chronic pain with linear mixed models reveals a continuous chronification of acute back pain

- Observational study

- From acute to chronic back pain: Using linear mixed models to explore changes in pain intensity, disability, and depression

- Editorial comment

- NSAIDs relieve osteoarthritis (OA) pain, but cardiovascular safety in question even for diclofenac, ibuprofen, naproxen, and celecoxib: what are the alternatives?

- Clinical pain research

- Efficacy and safety of diclofenac in osteoarthritis: Results of a network meta-analysis of unpublished legacy studies

- Editorial comment

- Editorial comment on Nina Kreddig’s and Monika Hasenbring’s study on pain anxiety and fear of (re) injury in patients with chronic back pain: Sex as a moderator

- Clinical pain research

- Pain anxiety and fear of (re) injury in patients with chronic back pain: Sex as a moderator

- Editorial comment

- Intraoral QST – Mission impossible or not?

- Clinical pain research

- Multifactorial assessment of measurement errors affecting intraoral quantitative sensory testing reliability

- Editorial comment

- Objective measurement of subjective pain-experience: Real nociceptive stimuli versus pain expectation

- Clinical pain research

- Cerebral oxygenation for pain monitoring in adults is ineffective: A sequence-randomized, sham controlled study in volunteers

- Editorial comment

- Association between adolescent and parental use of analgesics

- Observational study

- The association between adolescent and parental use of non-prescription analgesics for headache and other somatic pain – A cross-sectional study

- Editorial comment

- Cancer-pain intractable to high-doses systemic opioids can be relieved by intraspinal local anaesthetic plus an opioid and an alfa2-adrenoceptor agonist

- Clinical pain research

- Spinal analgesia for severe cancer pain: A retrospective analysis of 60 patients

- Editorial comment

- Specific symptoms and signs of unstable back segments and curative surgery?

- Clinical pain research

- Symptoms and signs possibly indicating segmental, discogenic pain. A fusion study with 18 years of follow-up

- Editorial comment

- Local anaesthesia methods for analgesia after total hip replacement: Problems of anatomy, methodology and interpretation?

- Clinical pain research

- Local infiltration analgesia or femoral nerve block for postoperative pain management in patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty. A randomized, double-blind study

- Editorial

- Scientific presentations at the 2017 annual meeting of the Scandinavian Association for the Study of Pain (SASP)

- Abstracts

- Correlation between quality of pain and depression: A post-operative assessment of pain after caesarian section among women in Ghana

- Abstracts

- Dynamic and static mechanical pain sensitivity is associated in women with migraine

- Abstracts

- The number of active trigger points is associated with sensory and emotional aspects of health-related quality of life in tension type headache

- Abstracts

- Chronic neuropathic pain following oxaliplatin and docetaxel: A 5-year follow-up questionnaire study

- Abstracts

- Expression of α1 adrenergic receptor subtypes by afferent fibers that innervate rat masseter muscle

- Abstracts

- Buprenorphine alleviation of pain does not compromise the rat monoarthritic pain model

- Abstracts

- Association between pain, disability, widespread pressure pain hypersensitivity and trigger points in subjects with neck pain

- Abstracts

- Association between widespread pressure pain hypersensitivity, health history, and trigger points in subjects with neck pain

- Abstracts

- Neuromas in patients with peripheral nerve injury and amputation - An ongoing study

- Abstracts

- The link between chronic musculoskeletal pain and sperm quality in overweight orthopedic patients

- Abstracts

- Several days of muscle hyperalgesia facilitates cortical somatosensory excitability

- Abstracts

- Social stress, epigenetic changes and pain

- Abstracts

- Characterization of released exosomes from satellite glial cells under normal and inflammatory conditions

- Abstracts

- Cell-based platform for studying trigeminal satellite glial cells under normal and inflammatory conditions

- Abstracts

- Tramadol in postoperative pain – 1 mg/ml IV gave no pain reduction but more side effects in third molar surgery

- Abstracts

- Tempo-spatial discrimination to non-noxious stimuli is better than for noxious stimuli

- Abstracts

- The encoding of the thermal grill illusion in the human spinal cord

- Abstracts

- Effect of cocoa on endorphin levels and craniofacial muscle sensitivity in healthy individuals

- Abstracts

- The impact of naloxegol treatment on gastrointestinal transit and colonic volume

- Abstracts

- Preoperative downregulation of long-noncoding RNA Meg3 in serum of patients with chronic postoperative pain after total knee replacement

- Abstracts

- Painful diabetic polyneuropathy and quality of life in Danish type 2 diabetic patients

- Abstracts

- “What about me?”: A qualitative explorative study on perspectives of spouses living with complex chronic pain patients

- Abstracts

- Increased postural stiffness in patients with knee osteoarthritis who are highly sensitized

- Abstracts

- Efficacy of dry needling on latent myofascial trigger points in male subjects with neck/shoulders musculoskeletal pain. A case series

- Abstracts

- Identification of pre-operative of risk factors associated with persistent post-operative pain by self-reporting tools in lower limb amputee patients – A feasibility study

- Abstracts

- Renal function estimations and dose recommendations for Gabapentin, Ibuprofen and Morphine in acute hip fracture patients

- Abstracts

- Evaluating the ability of non-rectangular electrical pulse forms to preferentially activate nociceptive fibers by comparing perception thresholds

- Abstracts

- Detection of systemic inflammation in severely impaired chronic pain patients, and effects of a CBT-ACT-based multi-modal pain rehabilitation program

- Abstracts

- Fixed or adapted conditioning intensity for repeated conditioned pain modulation

- Abstracts

- Combined treatment (Norspan, Gabapentin and Oxynorm) was found superior in pain management after total knee arthroplasty

- Abstracts

- Effects of conditioned pain modulation on the withdrawal pattern to nociceptive stimulation in humans – Preliminary results

- Abstracts

- Application of miR-223 onto the dorsal nerve roots in rats induces hypoexcitability in the pain pathways

- Abstracts

- Acute muscle pain alters corticomotor output of the affected muscle stronger than a synergistic, ipsilateral muscle

- Abstracts

- The subjective sensation induced by various thermal pulse stimulation in healthy volunteers

- Abstracts

- Assessing Offset Analgesia through electrical stimulations in healthy volunteers

- Abstracts

- Metastatic lung cancer in patient with non-malignant neck pain: A case report

- Abstracts

- The size of pain referral patterns from a tonic painful mechanical stimulus is increased in women

- Abstracts

- Oxycodone and macrogol 3350 treatment reduces anal sphincter relaxation compared to combined oxycodone and naloxone tablets

- Abstracts

- The effect of UVB-induced skin inflammation on histaminergic and non-histaminergic evoked itch and pain

- Abstracts

- Topical allyl-isothiocyanate (mustard oil) as a TRPA1-dependent human surrogate model of pain, hyperalgesia, and neurogenic inflammation – A dose response study

- Abstracts

- Dissatisfaction and persistent post-operative pain following total knee replacement – A 5 year follow-up of all patients from a whole region

- Abstracts

- Paradoxical differences in pain ratings of the same stimulus intensity

- Abstracts

- Pain assessment and post-operative pain management in orthopedic patients

- Abstracts

- Combined electric and pressure cuff pain stimuli for assessing conditioning pain modulation (CPM)

- Abstracts

- The effect of facilitated temporal summation of pain, widespread pressure hyperalgesia and pain intensity in patients with knee osteoarthritis on the responds to Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs – A preliminary analysis

- Abstracts

- How to obtain the biopsychosocial record in multidisciplinary pain clinic? An action research study

- Abstracts

- Experimental neck muscle pain increase pressure pain threshold over cervical facet joints

- Abstracts

- Are we using Placebo effects in specialized Palliative Care?

- Abstracts

- Prevalence and pattern of helmet-induced headache among Danish military personnel

- Abstracts

- Aquaporin 4 expression on trigeminal satellite glial cells under normal and inflammatory conditions

- Abstracts

- Preoperative synovitis in knee osteoarthritis is predictive for pain 1 year after total knee arthroplasty

- Abstracts

- Biomarkers alterations in trapezius muscle after an acute tissue trauma: A human microdialysis study

- Abstracts

- PainData: A clinical pain registry in Denmark

- Abstracts

- A novel method for investigating the importance of visual feedback on somatosensation and bodily-self perception

- Abstracts

- Drugs that can cause respiratory depression with concomitant use of opioids

- Abstracts

- The potential use of a serious game to help patients learn about post-operative pain management – An evaluation study

- Abstracts

- Modelling activity-dependent changes of velocity in C-fibers

- Abstracts

- Choice of rat strain in pre-clinical pain-research – Does it make a difference for translation from animal model to human condition?

- Abstracts

- Omics as a potential tool to identify biomarkers and to clarify the mechanism of chronic pain development

- Abstracts

- Evaluation of the benefits from the introduction meeting for patients with chronic non-malignant pain and their relatives in interdisciplinary pain center

- Observational study

- The changing face of acute pain services

- Observational study

- Chronic pain in multiple sclerosis: A10-year longitudinal study

- Clinical pain research

- Functional disability and depression symptoms in a paediatric persistent pain sample

- Observational study

- Pain provocation following sagittal plane repeated movements in people with chronic low back pain: Associations with pain sensitivity and psychological profiles

- Observational study

- A longitudinal exploration of pain tolerance and participation in contact sports

- Original experimental

- Taking a break in response to pain. An experimental investigation of the effects of interruptions by pain on subsequent activity resumption

- Clinical pain research

- Sex moderates the effects of positive and negative affect on clinical pain in patients with knee osteoarthritis

- Original experimental

- The effects of a brief educational intervention on medical students’ knowledge, attitudes and beliefs towards low back pain

- Observational study

- The association between pain characteristics, pain catastrophizing and health care use – Baseline results from the SWEPAIN cohort

- Topical review

- Couples coping with chronic pain: How do intercouple interactions relate to pain coping?

- Narrative review

- The wit and wisdom of Wilbert (Bill) Fordyce (1923 - 2009)

- Letter to the Editor

- Unjustified extrapolation

- Letter to the Editor

- Response to: “Letter to the Editor entitled: Unjustified extrapolation” [by authors: Supp G., Rosedale R., Werneke M.]

Articles in the same Issue

- Scandinavian Journal of Pain

- Editorial comment

- Glucocorticoids – Efficient analgesics against postherpetic neuralgia?

- Original experimental

- Effect of intrathecal glucocorticoids on the central glucocorticoid receptor in a rat nerve ligation model

- Editorial comment

- Important new insight in pain and pain treatment induced changes in functional connectivity between the Pain Matrix and the Salience, Central Executive, and Sensorimotor networks

- Original experimental

- Salience, central executive, and sensorimotor network functional connectivity alterations in failed back surgery syndrome

- Editorial comment

- Education and support strategies improve assessment and management of pain by nurses

- Clinical pain research

- Using education and support strategies to improve the way nurses assess regular and transient pain – A quality improvement study of three hospitals

- Editorial comment

- The interference of pain with task performance: Increasing ecological validity in research

- Original experimental

- The disruptive effects of pain on multitasking in a virtual errands task

- Editorial comment

- Analyzing transition from acute back pain to chronic pain with linear mixed models reveals a continuous chronification of acute back pain

- Observational study

- From acute to chronic back pain: Using linear mixed models to explore changes in pain intensity, disability, and depression

- Editorial comment

- NSAIDs relieve osteoarthritis (OA) pain, but cardiovascular safety in question even for diclofenac, ibuprofen, naproxen, and celecoxib: what are the alternatives?

- Clinical pain research

- Efficacy and safety of diclofenac in osteoarthritis: Results of a network meta-analysis of unpublished legacy studies

- Editorial comment

- Editorial comment on Nina Kreddig’s and Monika Hasenbring’s study on pain anxiety and fear of (re) injury in patients with chronic back pain: Sex as a moderator

- Clinical pain research

- Pain anxiety and fear of (re) injury in patients with chronic back pain: Sex as a moderator

- Editorial comment

- Intraoral QST – Mission impossible or not?

- Clinical pain research

- Multifactorial assessment of measurement errors affecting intraoral quantitative sensory testing reliability

- Editorial comment

- Objective measurement of subjective pain-experience: Real nociceptive stimuli versus pain expectation

- Clinical pain research

- Cerebral oxygenation for pain monitoring in adults is ineffective: A sequence-randomized, sham controlled study in volunteers

- Editorial comment

- Association between adolescent and parental use of analgesics

- Observational study

- The association between adolescent and parental use of non-prescription analgesics for headache and other somatic pain – A cross-sectional study

- Editorial comment

- Cancer-pain intractable to high-doses systemic opioids can be relieved by intraspinal local anaesthetic plus an opioid and an alfa2-adrenoceptor agonist

- Clinical pain research

- Spinal analgesia for severe cancer pain: A retrospective analysis of 60 patients

- Editorial comment

- Specific symptoms and signs of unstable back segments and curative surgery?

- Clinical pain research

- Symptoms and signs possibly indicating segmental, discogenic pain. A fusion study with 18 years of follow-up

- Editorial comment

- Local anaesthesia methods for analgesia after total hip replacement: Problems of anatomy, methodology and interpretation?

- Clinical pain research

- Local infiltration analgesia or femoral nerve block for postoperative pain management in patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty. A randomized, double-blind study

- Editorial

- Scientific presentations at the 2017 annual meeting of the Scandinavian Association for the Study of Pain (SASP)

- Abstracts

- Correlation between quality of pain and depression: A post-operative assessment of pain after caesarian section among women in Ghana

- Abstracts

- Dynamic and static mechanical pain sensitivity is associated in women with migraine

- Abstracts

- The number of active trigger points is associated with sensory and emotional aspects of health-related quality of life in tension type headache

- Abstracts

- Chronic neuropathic pain following oxaliplatin and docetaxel: A 5-year follow-up questionnaire study

- Abstracts

- Expression of α1 adrenergic receptor subtypes by afferent fibers that innervate rat masseter muscle

- Abstracts

- Buprenorphine alleviation of pain does not compromise the rat monoarthritic pain model

- Abstracts

- Association between pain, disability, widespread pressure pain hypersensitivity and trigger points in subjects with neck pain

- Abstracts

- Association between widespread pressure pain hypersensitivity, health history, and trigger points in subjects with neck pain

- Abstracts

- Neuromas in patients with peripheral nerve injury and amputation - An ongoing study

- Abstracts

- The link between chronic musculoskeletal pain and sperm quality in overweight orthopedic patients

- Abstracts

- Several days of muscle hyperalgesia facilitates cortical somatosensory excitability

- Abstracts

- Social stress, epigenetic changes and pain

- Abstracts

- Characterization of released exosomes from satellite glial cells under normal and inflammatory conditions

- Abstracts

- Cell-based platform for studying trigeminal satellite glial cells under normal and inflammatory conditions

- Abstracts

- Tramadol in postoperative pain – 1 mg/ml IV gave no pain reduction but more side effects in third molar surgery

- Abstracts

- Tempo-spatial discrimination to non-noxious stimuli is better than for noxious stimuli

- Abstracts

- The encoding of the thermal grill illusion in the human spinal cord

- Abstracts

- Effect of cocoa on endorphin levels and craniofacial muscle sensitivity in healthy individuals

- Abstracts

- The impact of naloxegol treatment on gastrointestinal transit and colonic volume

- Abstracts

- Preoperative downregulation of long-noncoding RNA Meg3 in serum of patients with chronic postoperative pain after total knee replacement

- Abstracts

- Painful diabetic polyneuropathy and quality of life in Danish type 2 diabetic patients

- Abstracts

- “What about me?”: A qualitative explorative study on perspectives of spouses living with complex chronic pain patients

- Abstracts

- Increased postural stiffness in patients with knee osteoarthritis who are highly sensitized

- Abstracts

- Efficacy of dry needling on latent myofascial trigger points in male subjects with neck/shoulders musculoskeletal pain. A case series

- Abstracts

- Identification of pre-operative of risk factors associated with persistent post-operative pain by self-reporting tools in lower limb amputee patients – A feasibility study

- Abstracts

- Renal function estimations and dose recommendations for Gabapentin, Ibuprofen and Morphine in acute hip fracture patients

- Abstracts

- Evaluating the ability of non-rectangular electrical pulse forms to preferentially activate nociceptive fibers by comparing perception thresholds

- Abstracts

- Detection of systemic inflammation in severely impaired chronic pain patients, and effects of a CBT-ACT-based multi-modal pain rehabilitation program

- Abstracts

- Fixed or adapted conditioning intensity for repeated conditioned pain modulation

- Abstracts

- Combined treatment (Norspan, Gabapentin and Oxynorm) was found superior in pain management after total knee arthroplasty

- Abstracts

- Effects of conditioned pain modulation on the withdrawal pattern to nociceptive stimulation in humans – Preliminary results

- Abstracts

- Application of miR-223 onto the dorsal nerve roots in rats induces hypoexcitability in the pain pathways

- Abstracts

- Acute muscle pain alters corticomotor output of the affected muscle stronger than a synergistic, ipsilateral muscle

- Abstracts

- The subjective sensation induced by various thermal pulse stimulation in healthy volunteers

- Abstracts

- Assessing Offset Analgesia through electrical stimulations in healthy volunteers

- Abstracts

- Metastatic lung cancer in patient with non-malignant neck pain: A case report

- Abstracts

- The size of pain referral patterns from a tonic painful mechanical stimulus is increased in women

- Abstracts

- Oxycodone and macrogol 3350 treatment reduces anal sphincter relaxation compared to combined oxycodone and naloxone tablets

- Abstracts

- The effect of UVB-induced skin inflammation on histaminergic and non-histaminergic evoked itch and pain

- Abstracts

- Topical allyl-isothiocyanate (mustard oil) as a TRPA1-dependent human surrogate model of pain, hyperalgesia, and neurogenic inflammation – A dose response study

- Abstracts

- Dissatisfaction and persistent post-operative pain following total knee replacement – A 5 year follow-up of all patients from a whole region

- Abstracts

- Paradoxical differences in pain ratings of the same stimulus intensity

- Abstracts

- Pain assessment and post-operative pain management in orthopedic patients

- Abstracts

- Combined electric and pressure cuff pain stimuli for assessing conditioning pain modulation (CPM)

- Abstracts

- The effect of facilitated temporal summation of pain, widespread pressure hyperalgesia and pain intensity in patients with knee osteoarthritis on the responds to Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs – A preliminary analysis

- Abstracts

- How to obtain the biopsychosocial record in multidisciplinary pain clinic? An action research study

- Abstracts

- Experimental neck muscle pain increase pressure pain threshold over cervical facet joints

- Abstracts

- Are we using Placebo effects in specialized Palliative Care?

- Abstracts

- Prevalence and pattern of helmet-induced headache among Danish military personnel

- Abstracts

- Aquaporin 4 expression on trigeminal satellite glial cells under normal and inflammatory conditions

- Abstracts

- Preoperative synovitis in knee osteoarthritis is predictive for pain 1 year after total knee arthroplasty

- Abstracts

- Biomarkers alterations in trapezius muscle after an acute tissue trauma: A human microdialysis study

- Abstracts

- PainData: A clinical pain registry in Denmark

- Abstracts

- A novel method for investigating the importance of visual feedback on somatosensation and bodily-self perception

- Abstracts

- Drugs that can cause respiratory depression with concomitant use of opioids

- Abstracts

- The potential use of a serious game to help patients learn about post-operative pain management – An evaluation study

- Abstracts

- Modelling activity-dependent changes of velocity in C-fibers

- Abstracts

- Choice of rat strain in pre-clinical pain-research – Does it make a difference for translation from animal model to human condition?

- Abstracts

- Omics as a potential tool to identify biomarkers and to clarify the mechanism of chronic pain development

- Abstracts

- Evaluation of the benefits from the introduction meeting for patients with chronic non-malignant pain and their relatives in interdisciplinary pain center

- Observational study

- The changing face of acute pain services

- Observational study

- Chronic pain in multiple sclerosis: A10-year longitudinal study

- Clinical pain research

- Functional disability and depression symptoms in a paediatric persistent pain sample

- Observational study

- Pain provocation following sagittal plane repeated movements in people with chronic low back pain: Associations with pain sensitivity and psychological profiles

- Observational study

- A longitudinal exploration of pain tolerance and participation in contact sports

- Original experimental

- Taking a break in response to pain. An experimental investigation of the effects of interruptions by pain on subsequent activity resumption

- Clinical pain research

- Sex moderates the effects of positive and negative affect on clinical pain in patients with knee osteoarthritis

- Original experimental

- The effects of a brief educational intervention on medical students’ knowledge, attitudes and beliefs towards low back pain

- Observational study

- The association between pain characteristics, pain catastrophizing and health care use – Baseline results from the SWEPAIN cohort

- Topical review

- Couples coping with chronic pain: How do intercouple interactions relate to pain coping?

- Narrative review

- The wit and wisdom of Wilbert (Bill) Fordyce (1923 - 2009)

- Letter to the Editor

- Unjustified extrapolation

- Letter to the Editor

- Response to: “Letter to the Editor entitled: Unjustified extrapolation” [by authors: Supp G., Rosedale R., Werneke M.]