A randomized study comparing plasma concentration of ropivacaine after local infiltration analgesia and femoral block in primary total knee arthroplasty

-

Fatin Affas

, Eva-Britt Nygårds

Abstract

Pain after total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is difficult to control. A recently developed and increasingly popular method for postoperative analgesia following knee and hip arthroplasty is Local Infiltration Analgesia (LIA) with ropivacaine, ketorolac and epinephrine. This method is considered to have certain advantages, which include administration at the site of traumatized tissue, minimal systemic side effects, faster postoperative mobilization, earlier postoperative discharge from hospital and less opioid consumption. One limitation, which may prevent the widespread use of LIA is the lack of information regarding plasma concentrations of ropivacaine and ketorolac.

The aim of this academically initiated study was to detect any toxic or near-toxic plasma concentrations of ropivacaine and ketorolac following LIA after TKA.

Methods

Forty patients scheduled for primary total knee arthroplasty under spinal anaesthesia, were randomized to receive either local infiltration analgesia with a mixture of ropivacaine 300 mg, ketorolac 30mg and epinephrine or repeated femoral nerve block with ropivacaine in combination with three doses of 10mg intravenous ketorolac according to clinical routine. Plasma concentration of ropivacaine and ketorolac were quantified by liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS).

Results

The maximal detected ropivacaine plasma level in the LIA group was not statistically higher than in the femoral block group using the Mann–Whitney U-test (p = 0.08). However, the median concentration in the LIA group was significantly higher than in the femoral block group (p < 0.0001; Mann–Whitney U-test).

The maximal plasma concentrations of ketorolac following administration of 30mg according to the LIA protocol were detected 1 h or 2 h after release of the tourniquet in the LIA group: 152–958 ng/ml (95% CI: 303–512 ng/ml; n = 20). The range of the plasma concentration of ketorolac 2–3 h after injection of a single dose of 10mg was 57–1216 ng/ml (95% CI: 162–420 ng/ml; n = 20).

Conclusion

During the first 24 h plasma concentration of ropivacaine seems to be lower after repeated femoral block than after LIA. Since the maximal ropivacaine level following LIA is detected around 4–6 h after release of the tourniquet, cardiac monitoring should cover this interval. Regarding ketorolac, our preliminary data indicate that the risk for concentration dependent side effects may be highest during the first hours after release of the tourniquet.

Implication

Femoral block may be the preferred method for postoperative analgesia in patients with increased risk for cardiac side effects from ropivacaine. Administration of a booster dose of ketorolac shortly after termination of the surgical procedure if LIA was used may result in an increased risk for toxicity.

1 Introduction

Pain after TKA is difficult to control. A recently developed and increasingly popular method for postoperative analgesia following knee and hip arthroplasty is Local Infiltration Analgesia (LIA) with ropivacaine, ketorolac and epinephrine [1]. This method is considered to have certain advantages, which include administration at the site of traumatized tissue, minimal systemic side effects, faster postoperative mobilization, earlier postoperative discharge from hospital and less opioid consumption [1,2,3,4,5]. One limitation, which may prevent the widespread use of LIA is lack of knowledge regarding potential toxicity resulting from excessive plasma concentrations of ropivacaine. Although the manufacturer (Astra-Zeneca) recommends 300mg ropivacaine as a maximum dose for infiltration, much larger doses are often used [2,3,4,5,6]. Ropivacaine is a long-acting local anaesthetic agent similar to bupivacaine [7]. It is considered to be less toxic to the central nervous system and the cardiovascular system [7,8]. The risk of cardiac arrhythmia is shared with all local anaesthetics and depends on the plasma concentration. Signs of toxicity may be observed at 1500 ng/ml [7]. Intra-articular doses of 150mg ropivacaine in the knee joint result in amaximal total plasma concentration of 1175 ng/ml [9]. The typical dose of ropivacaine in LIA is 300mg administered over 30 min. Thus, the plasma concentration of ropivacaine following LIA may reach the threshold for neural and cardiovascular toxicity.

Maximum tolerated doses of local anaesthetics in combination with epinephrine administered by infiltration have not yet been established [10].

Ketorolac is a non-selective cyclooxygenase inhibitor, which has been used for postoperative analgesia during almost twenty years [11]. Local administration affords similar or better pain relief than systemic administration [12]. However, especially postoperatively, there is a dose- and plasma-concentration-dependent risk of renal side effects with decreased glomerular filtration in addition to an increased risk of peptic ulcer and bleeding. The peak plasma concentration of ropivacaine and ketorolac following intra- and peri-articular infiltration is presumably reached later than that following i.v. administration. However, extensive surgical trauma and soft-tissue dissection may increase systemic absorption during major orthopedic surgery. This effect may be delayed by the use of a thigh tourniquet during surgery [13].

The aim of the present randomized, single-site clinical trial was to collect data on the plasma concentration of ropivacaine and ketorolac during two different routine protocols of post operative pain relief in patients scheduled for primary knee arthroplasty in order to detect any toxic or near-toxic plasma concentrations. One group (LIA) received intra- and peri-articular injection of ropivacaine, ketorolac and epinephrine and the other a femoral block with ropivacaine and i.v. injection of ketorolac according to clinical routine.

2 Patients and methods

The present academically initiated randomized trial was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration II and approved by the Regional Research Ethics Committee at the Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm (2006/397-31/4) and by the Swedish Medical Products Agency. The enrolment period started in December 2006 and lasted until February 2008.

Inclusion criteria: Adult patients (older than 18 years) with osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis scheduled for primary unilateral elective total knee arthroplasty, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification I–III.

Exclusion criteria: Allergy or intolerance to one of the study drugs, renal insufficiency, epilepsy, language difficulty, mental illness, dementia, QT-interval on Electro Cardio Graph (ECG) > 450ms before start.

After oral and written informed consent, 40 patients scheduled for primary unilateral total knee arthroplasty under spinal anaesthesia were randomly assigned into two groups of postoperative pain management immediately prior to the surgical procedure:

Femoral block (Group F) received ropivacaine (Narop®, Astra-Zeneca) av i.v. ketorolac (Toradol®, Roche) at the PACU and group LIA received peri- and intraarticular infiltration with ropivacaine + ketorolac (Toradol®, Roche) and epinephrine (Adrenalin®, NM Pharma).

2.1 Randomization

The randomization sequence was determined by mixing 40 tickets, 20 labelled “F” and 20 labelled “LIA” in sealed opaque envelopes and drawing one envelop at a time. The envelopes were consecutively numbered from 1 to 40 (Christina Olofsson and Eva-Britt Nygårds). Information of the procedure for postoperative pain relief for the first patient was found in envelop 1 and for the second patient in envelop 2 and so on.

2.2 Procedure

Antithrombotic therapy with low molecular weight heparin, enoxaparinnatrium (Klexane®, Aventis Pharma) 40mg started 12 h before spinal anaesthesia and was given for at least 5 days. Before induction of spinal anaesthesia monitoring of oxygen saturation, blood pressure and electrocardiogram (ECG) was started. Sedation was induced with midazolam (Midazolam®, Alpharma) 1–2mg i.v. or propofol (Propofol®, Abbot). Puncture for spinal anaesthesia was at level L2–3 or L3–4. Isobaric bupivacaine (Marcain Spinal®, Astra-Zeneca) 5mg/ml at a volume of 3 ml was injected with the patient lying with the operating side upwards. All patients had a urinary bladder catheter, inserted after spinal anaesthesia and removed the day after surgery. All patients received 2 g dicloxacillin i.v. before surgery.

The TKA-procedure was performed following inflation of a thigh tourniquet, which was inflated just before skin incision and released after wound closure. The release of the tourniquet is time zero “0” in the LIA group.

Group F received a femoral nerve block directly after spinal anaesthesia.

Patients were placed in the supine position. Under sterile condition, the pulse of the femoral artery was identified, the needle (Plexolong Nanolin cannula facette 19G×50mm®, Pajunk) connected to a nerve stimulator (Simplex B®, Braun: serial no. 17002) set up to deliver 1.2mA was inserted cephalad 45 angle to skin at the level of femoral crease 1–1.5cm lateral to the femoral artery pulse [14]. The femoral nerve was identified by eliciting quadriceps muscle contractions (“dancing patella”). The current was gradually reduced to achieve twitches of the quadriceps muscle at 0.2–0.4mA and the catheter (StimuLong Sono®, Pajunk) was advanced through the needle.

The connection of the nerve stimulator was changed from needle to catheter and stimulation intensity was started at 1.2mA until the desired motor response was obtained. Thereafter, the intensity was reduced to 0.2–0.4 mA. The catheter was secured in place with transparent dressing (Tegaderm®, 3 M). After negative blood aspiration 30 ml ropivacaine 2mg/ml (Narop) was injected followed by 15 ml ropivacaine 2mg/ml 4 hourly for 24 h (total dose ropivacaine 240 mg/24 h). Group F received ketorolac (Toradol) 10mg intravenously in the Post Anaesthetic Care Unit (PACU), and again after 8 h and 16 h. The total dose of ropivacaine during 24 h was 240mg and the total dose of ketorolac was 30 mg.

Group LIA received peri-and intra-articular infiltration with a mixture of 150 ml ropivacaine (2 mg/ml), 1ml ketorolac (30 mg/ml), and 5ml epinephrine (0.1 mg/ml) (total volume 156 ml). This solution was prepared by the operation nurse prior to the start of the surgical procedure. The solution was given sequentially; 30 ml was injected intracutaneously at the start of the operation, 80 ml was injected into the posterior part of the capsule, close to the incision line, in the vastus intermedius and lateralis and around the collateral ligaments before cementation, and 46 ml was instilled through an intraarticular catheter (epidural catheter gauge 16) inserted at the end of the surgical procedure. The total dose of ropivacaine during the first postoperative 24 h was 300mg and the total dose of ketorolac was 30 mg.

In the recovery room all patients were provided with a patient controlled analgesia (PCA) morphine pump (Abbott Pain Manager®, Abbott Laboratories) programmed to give an intravenous bolus of morphine 2mg/dose on demand with a lock-out time of 6 min and maximum dose of 35 mg/4 h. All patients were introduced to the PCA-technique and encouraged to use it as often as needed. After 24 h PCA pump use was verified by a print out of all doses of morphine and their time of administration. In addition to PCA all patients received paracetamol (1 g×4), either orally (Alvedon®, Astra Zeneca) or i.v. (Perfalgan®, Bristol-Myer Squibb).

Electro Cardio Graph (ECG) was performed preoperatively, 2 h after the end of surgery in the recovery room and 24 h postoperatively in the ward.

All patients received postoperative physiotherapy, which started the morning after operation.

2.3 Blood samples

Blood samples for ropivacaine and ketorolac plasma concentration were drawn from a vein in the arm not used for i.v. infusions, or from a radial-artery cannula used for patient monitoring. Blood sampling was started 20 min after injecting ropivacaine in the femoral catheter in group F (Time zero “0” in femoral group). In the LIA group the release of the tourniquet was time zero “0”. The first sample was taken at 20 min. Additional samples were taken at 40 and 60 min and 2, 4, 6, 12, 24 h. The 12-h samples were taken only in four patients due to the inconvenient sampling time. The blood samples were centrifuged directly, plasma-separated and immediately frozen and stored at −20 °C until assayed.

2.4 Quantification of ropivacaine and ketorolac

The reference materials ropivacaine and the internal standard bupivacaine were obtained from AstraZeneca, Södertälje, Sweden. The reference material ketorolac trometamol was obtained from USP, Rockville, MD, USA and the internal standard ketobemidon-d4 was a gift from Prof. Ulf Bondesson (Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Uppsala, Sweden).

Ropivacaine was quantified by LC–MS using Agilent 1100 MSD (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA). Ketorolac was quantified by LC–MS/MSconsisting of aWaters Acquity UPLC (Ultra-performance liquid chromatograph) connected to a Quattro Premier XE tandem mass spectrometer. The limit of quantification was 10 ng/ml for each compound and the maximal calibrated range was 10,000 ng/ml. Analytical details are provided by the corresponding author upon request.

2.5 Statistical analysis

The sample size of this study was based on the power for detection of a significant difference in pain intensity published as a separate article [15]. A sample size of 20 in each group has an 80% power to detect a difference between means of 1.0 with a significance level (α) of 0.05 (two-tailed) using the unpaired Student’s t-test.

The aim of the study was to determine if the plasma concentration of ropivacaine and ketorolac after LIA reaches toxic or near-toxic levels. Thus, mainly descriptive statistics with focus on maximal plasma concentration are presented. The maximal concentration of ropivacaine of each patient in the LIA group was compared to the maximal concentration of each patient in the femoral block group by unpaired t-test.

Graphpad Prizm 5.02 for Windows www.graphpad.com was used for statistical analysis and the graphs.

3 Results

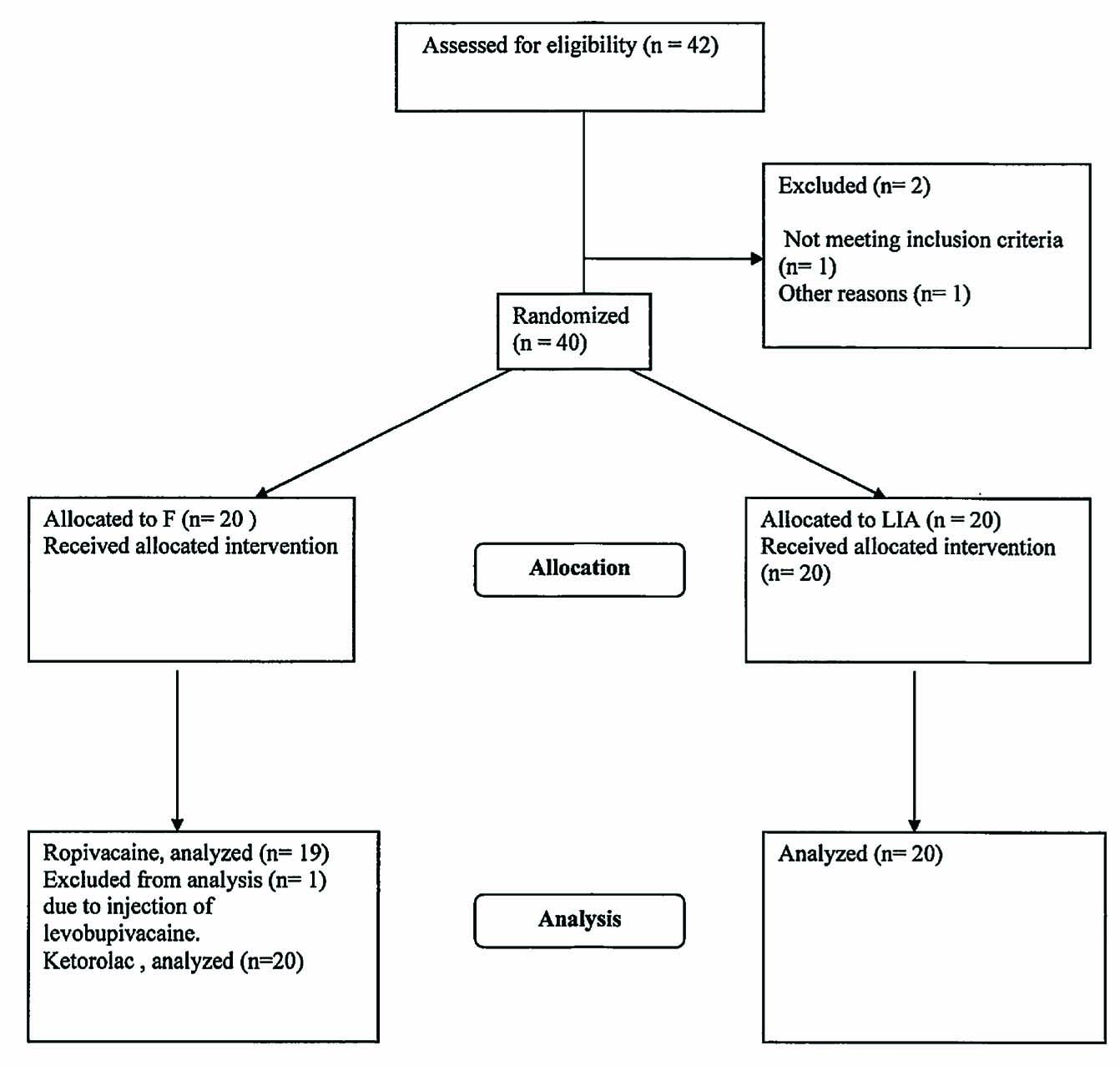

The demographic characteristics were similar in both groups (Table 1). Plasma concentration of ropivacaine and ketorolac from one patient in the femoral group was excluded from the study since levobupivacaine was injected instead of ropivacaine due to a misunderstanding. Data on the ketorolac concentration of one patient in the LIA group is not available (Fig. 1).

Patient demographics.

| Femoral block | LIA | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex (M/F)[a] | 8/11 | 11/9 |

| Age mean (range) | 69 (53–88) | 67 (29–85) |

| Weight (kg) | 83 ± 13 | 78 ± 18 |

| Height (cm) | 168 ± 9 | 171 ± 11 |

| BMI | 27 | 27 |

| ASA I/II/III | 2/8/9 | 3/7/10 |

| RA/OA[b] | 3/16 | 6/14 |

-

Values are expressed as mean (range) or mean±SD.

Consort flow chart.

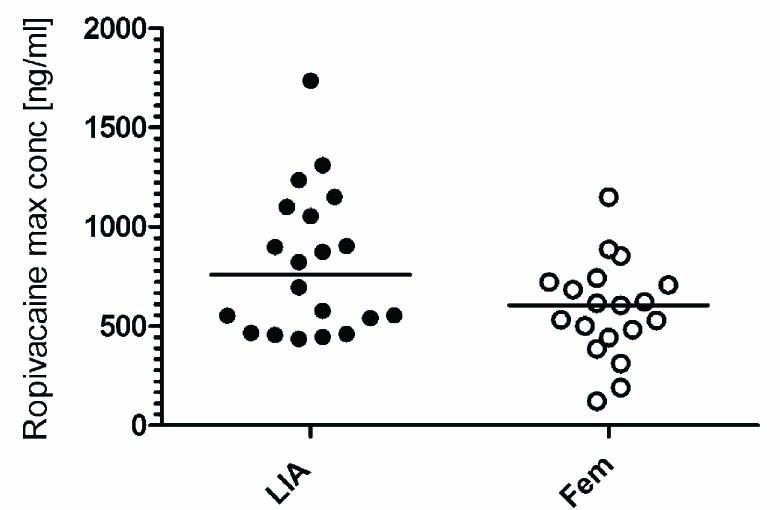

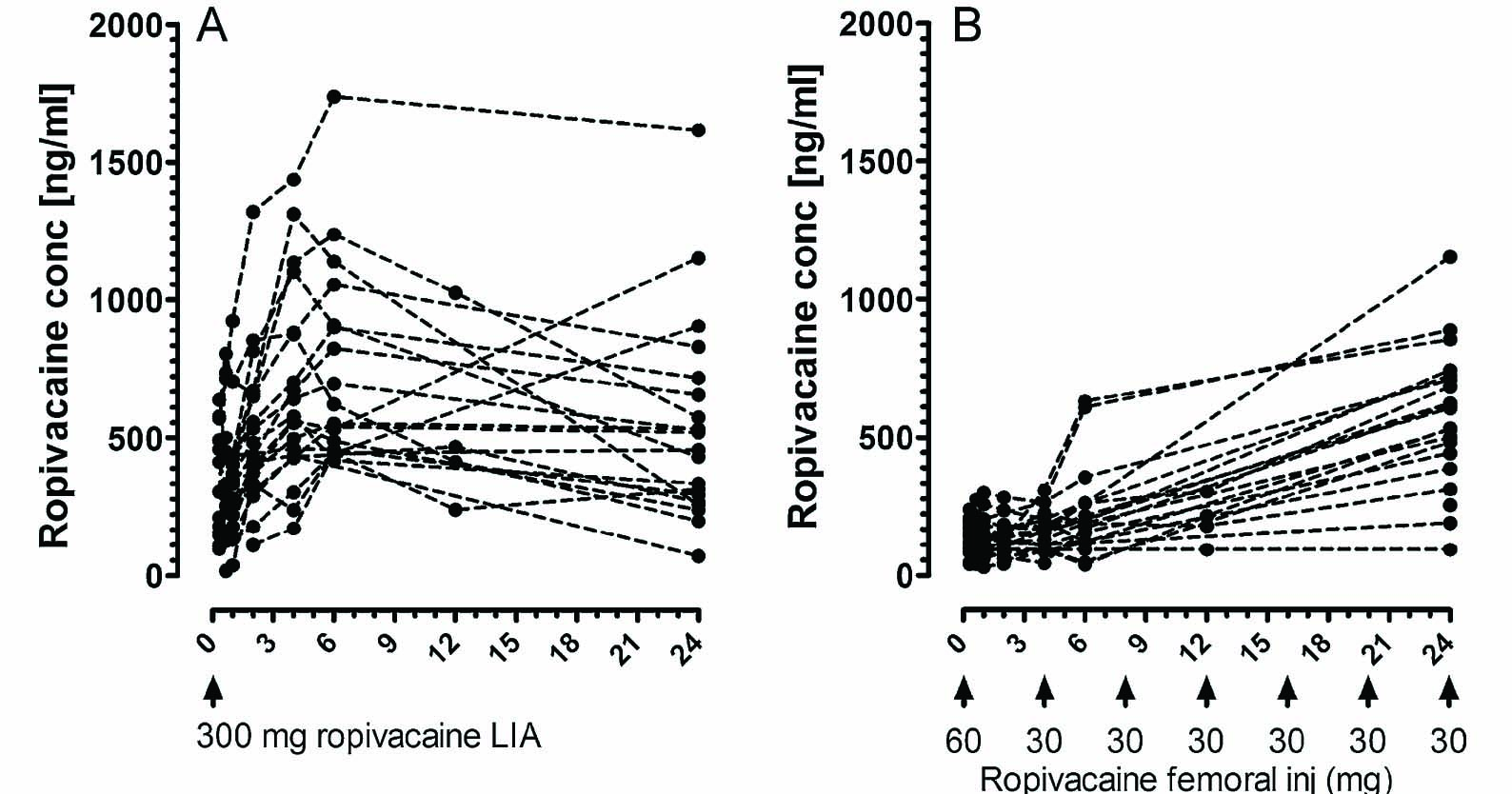

Similar maximal plasma concentrations of ropivacaine were detected in the LIA group and in the femoral block group during the first 24 h (Fig. 2, Table 2). Maximal plasma concentrations in the LIA group were detected at 4 or 6 h after injection (Fig. 3A). In the femoral block group, the highest levels were often detected at 24 h (Fig. 3B).

Maximal detected concentration of ropivacaine during 24 h. Data expressed as maximal concentration for each patient. The line indicates the median. No statistical difference was detected between the LIA and femoral block group.

Total plasma concentration of ropivacaine during 24 h. (A) LIA group (n = 20). In this group zero “0” refers to release of the tourniquet. The LIA group received 300mg ropivacaine. (B) Femoral block group (n = 19). In this group time zero “0” refers to completion of the first injection for femoral block (60 mg), the following doses (30mg every 4 h) are indicated in the figure.

Maximal ropivacaine plasma concentration during 24 h [ng/ml].

| Range | Mean (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| LIA, n = 20 | 435–1735 | 813 (644–982) |

| Femoral block, n = 19 | 122–1151 | 567 (450–684) |

The maximal detected ropivacaine plasma level in the LIA group was not statistically higher than in the femoral block group using Mann–Whitney U-test (p = 0.08). However, the median concentration in the LIA group (95% CI: 376–611 ng/ml) was significantly higher than in the femoral block group (95% CI: 124–183 ng/ml) (<0.0001; Mann–Whitney U-test).

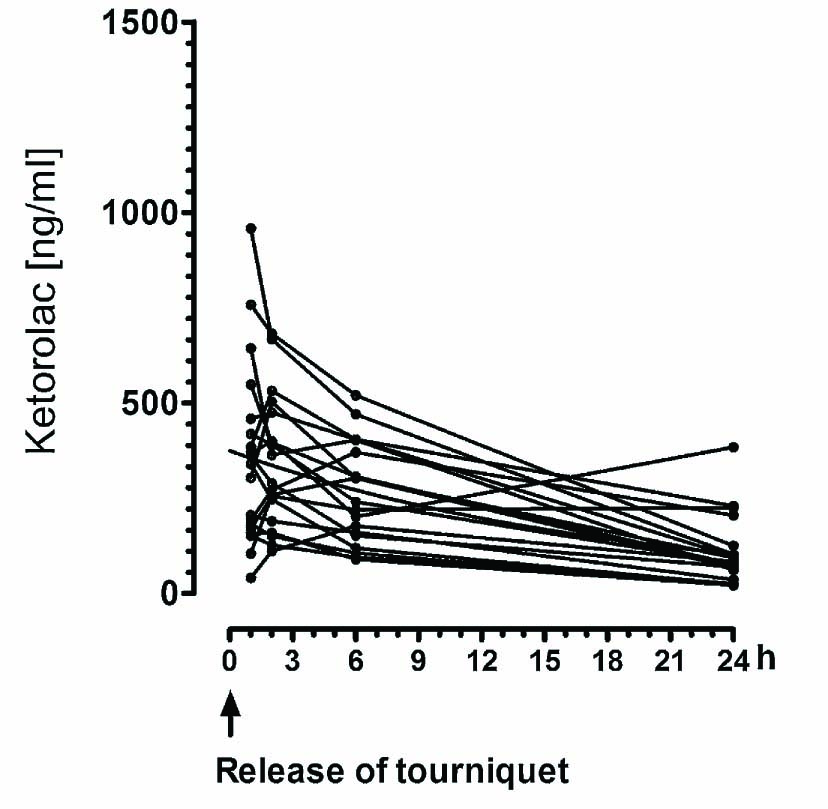

The range of the maximal plasma concentrations of ketorolac 1 h or 2 h after release of the tourniquet in the LIA group was 152–958 ng/ml (95% CI: 303–512 ng/ml; n = 20) (Fig. 4). The femoral block group received three doses of i.v. ketorolac 10 mg. Due to the fact that the i.v. injection of ketorolac at the PACU was performed at different time points depending on the arrival of the patient, we cannot present a proper concentration curve for ketorolac. The range of the plasma concentration of ketorolac 2–3 h after injection of a single dose of 10mg was 57–1216 ng/ml (95% CI: 162–420 ng/ml; n = 20). At 24 h, 2–3 h after injection of the third dose of ketorolac 10mg the range of the plasma concentration was 10–529 ng/ml (95% CI: 145–285 ng/ml).

Total plasma concentration of ketorolac in the LIA group. The LIA group received 30mg ketorolac. In this group zero “0” refers to release of the tourniquet.

4 Discussion

The maximal plasma concentration of ropivacaine using the LIA protocol seems to be higher than after femoral block.

Plasma levels of ropivacaine following peri-and intraarticular injection according to the LIA protocol may approach toxic levels during the first 4–6 h. However, since we did not analyze the plasma concentration between 6 and 12, and 12 and 24 h, we cannot exclude the possibility that some individuals displayed maximal levels later than 6 h after induction of LIA. This delayed peak was not expected and despite insufficient data on the exact time of maximal plasma concentration from the present study, it may be wise to consider cardiac monitoring for at least 6 h after surgery—a timepoint when most patients are transferred to ordinary wards without routine cardiac monitoring.

The plasma concentration of ropivacaine after repeated femoral block was higher than expected and in contrast to a common belief, the ropivacaine plasma level tended to accumulate during the first 24 postoperative hours using the present protocol. Since the plasma level of ropivacaine after femoral block had not started to decline at 24 h we cannot exclude the possibility of higher ropivacaine levels after 24 h.

The range of maximal plasma levels following LIA and following repeated femoral block displayed a considerable overlap. However, approximately one-third of the LIA group displayed ropivacaine levels higher than 1 μg/ml, as compared to only one individual following repeated femoral block.

Despite the finding of higher plasma concentrations of ropivacaine following LIA, we got no indication of adverse cardiac or CNS events. ECG monitoring two hours after ending the infiltration of local anaesthetic showed no arrhythmic effect of ropivacaine. Unfortunately we did not monitor the ECG around 4–6 h after LIA during the highest detected ropivacaine levels. Central nervous and cardiovascular ropivacaine toxicity has been detected in healthy volunteers at plasma concentrations of 1–2 μg/ml following intravenous infusion [7,8]. However, studies on peripheral and central blocks have reported higher plasma concentrations (2–4.2 μg/ml) without adverse reactions [16,17]. The ropivacaine concentrations observed in the present study were below the established toxic threshold for most of our patients although a few reached a plasma concentration of 1.4–1.7 μg/ml.

We are aware of a growing popularity of bolus doses or continuous infusions to top up preoperative wound infiltration of local anaesthetic after total knee arthroplasty [1,2,18,19]. Since the maximum concentration of ropivacaine was reached around four to six hours after giving the total dose, adding a bolus dose of local anaesthetic early in the postoperative period may result in potentially hazardous concentrations.

Periarticular administration of 30mg ketorolac according to the LIA procedure seems to lead to a plasma concentration similar to that three hours following either a single intravenous injection of 10mg or three hours after three injections of 10mg separated by 8 h. Thus, our data may indicate that both routes result in similar exposure to ketorolac or at least similar maximal levels of ketorolac. However, since the data points are sparse our present study cannot determine whether higher plasma levels of ketorolac are reached with local infiltration anaesthesia or with repeated intravenous administration.

Our data indicate that the common clinical routine of adding oral or intravenous NSAIDs a few hours after terminating the surgical procedure if LIA was used may increase the risk of concentration-dependent side effects of ketorolac.

4.1 Study limitations

One obvious limitation of the present study is that the data collected on the plasma concentration of ropivacaine and ketorolac following administration with LIA did not cover the peak plasma concentration in most patients, and the data are insufficient to permit proper pharmacokinetic analysis. Thus our data are hypothesis generating rather than hypothesis testing. Unfortunately we did not analyze the free concentration of ropivacaine, nor plasma α1-acid glycoprotein. The latter is increased after surgery and binds to ropivacaine and bupivacaine [19] and may prevent the rise of the free and pharmacologically active fraction of the local anaesthetic. These aspects are the focus of ongoing studies.

Plasma concentrations of ketorolac appeared to be similar regardless of route of administration.

However, the plasma samples were not optimized to cover peak concentration after repeated intravenous administration in the femoral block group.

Unselective cyclooxygenase inhibitors (NSAIDs) may decrease renal function and inhibit platelet function and cannot be used for all patients [20]. In the present study we did not detect increased bleeding or decreased renal function using routine clinical monitoring. Thus we cannot exclude a minor increase of postoperative bleeding. However, a previous study also in patients with TKA has assessed the risk for postoperative bleeding with ketorolac [21]. Four intravenous doses of ketorolac 30mg every 6 h (total 120 mg/24 h) did not result in a marked increase of postoperative bleeding monitored as decreased hematocrite.

Possible renal side effects of ketorolac have been assessed in healthy, well hydrated patients anaesthetized with sevoflurane. Neither renal glomerular nor tubular dysfunction was detected [22]. However, elderly patients are at greater risk for renal side effects and in order to address this issue in depth, a randomised trial with a control group not treated with unselective COX-inhibitors would be needed.

The present experimental protocol using different dosing intervals and doses was not designed to determine whether ketorolac carries a higher risk for adverse effects after peripheral administration or after intravenous administration.

The LIA technique has been shown to result in a long lasting pain relief and reduced need for opioid analgesics [1,2,23]. The average pain intensity in the LIA group and the femoral block group was around 2 on a VAS scale in both groups, details are presented in a separate publication [15].

The direct analgesic effect in the surgical field and the addition of epinephrine, which prolongs the action of the local anaesthetic agent are obvious reasons. Our findings also raise the possibility of a prolonged action due to considerable systemic concentrations of the local anaesthetic 24 h after the administration of ropivacaine. During the past thirty years preclinical and clinical studies have reported analgesic effects of intravenously administered sodium channel blockers. It is still unclear whether intravenously administered sodium channel blockers can affect acute postoperative pain. Conflicting results after perioperative intravenous infusion of lidocaine have been presented [24,25,26]. Lidocaine is the most commonly used local anaesthetic for intravenous infusion in clinical studies, due to its lower cardio toxicity compared with long-acting sodium channel blockers. It has a brief effect and most trials terminate the infusion shortly after the end of the operation, which prevents accumulation. Ropivacaine has a similar mechanism of action as lidocaine and it seems reasonable to assume that also ropivacaine may have systemic effects as well. We are not aware of the use of lidocaine in LIA after total knee or hip arthroplasty.

We did not investigate the effect of compression bandage [13] on the distribution of ropivacaine and ketorolac and it is hard to predict how compression of the lower limb would affect the systemic distribution of ropivacaine and ketorolac. A lower blood flow may slow down the time to reach concentration equilibrium between the leg and the systemic circulation. However, a lower volume of the leg may increase the systemic concentration slightly.

5 Conclusion

The risk for concentration dependent side effects of ropivacaine may be higher after local administration according to the LIA protocol than using repeated femoral block. Since the maximal ropivacaine level following LIA is detected around 4–6 h after release of the tourniquet, cardiac monitoring should during this period be considered. Regarding ketorolac, our preliminary data indicate that the risk for concentration dependent side effects may be highest during the first hours after release of the tourniquet. The common routine of administration of a booster dose of ketorolac shortly after termination of the surgical procedure, if LIA was used, may result in an increased risk for toxicity. Our data do not indicate that local administration of ketorolac is a safer alternative than repeated intravenous injection and similar restrictions should be applied for both routes.

DOI of refers to article: 10.1016/j.sjpain.2011.11.003.

-

Conflict of interest: None.

Acknowledgements

This academically conducted clinical trial was supported by funds of the Karolinska Institutet and research funds of the Stockholm county (ALF).

References

[1] Kerr D, Kohan L. Local infiltration analgesia: a technique for the control of acute postoperative pain following knee and hip surgery: a case study of 325 patients. Acta Orthop 2008;79:174–83.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Andersen L, Husted H, Otte K, Kristensen B, Kehlet H. High-volume infiltration analgesia in total knee arthroplasty: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2008;52:1331–5.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Bianconi M, Ferraro L, Traina G, Zanoli G, Antonelli T, Guberti A, Ricci R, Massari L. Pharmacokinetics and efficacy of ropivacaine continuous wound instillation after joint replacement surgery. Br J Anaesth 2003;91:830–5.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Lombardi AJ, Berend K, Mallory T, Dodds K, Adams J. Soft tissue and intra-articular injection of bupivacaine, epinephrine, and morphine has a beneficial effect after total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2004;12:5–30.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Röstlund T, Kehlet H. High-dose local infiltration analgesia after hip and knee replacement—what is it, why does it work, and what are the future challenges? Acta Orthop 2007;78:159–61.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Andersen L, Kristensen B, Husted H, Otte K, Kehlet H. Local anesthetics after total knee arthroplasty: intraarticular or extraarticular administration? A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Acta Orthop 2008;79:800–5.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Scott D, Lee A, Fagan D, Bowler G, Bloomfield P, Lundh R. Acute toxicity of ropivacaine compared with that of bupivacaine. Anesth Analg 1989;69:563–9.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Knudsen K, Beckman Suurküla M, Blomberg S, Sjövall J, Edvardsson N. Central nervous and cardiovascular effects of i. v. infusions of ropivacaine, bupivacaine and placebo in volunteers. Br J Anaesth 1997;78:507–14.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Ng H, Nordström U, Axelsson K, Perniola A, Gustav E, Ryttberg L, Gupta A. Efficacy of intra-articular bupivacaine, ropivacaine, or a combination of ropivacaine, morphine, and ketorolac on postoperative pain relief after ambulatory arthroscopic knee surgery: a randomized double-blind study. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2006;31:26–33.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Rosenberg P, Veering B, Urmey W. Maximum recommended doses of local anesthetics: a multifactorial concept. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2004;29:564–75.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Brocks D, Jamali F. Clinical pharmacokinetics of ketorolac tromethamine. Clin Pharmacokinet 1992;23:415–27.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Rømsing J, Møiniche S, Ostergaard D, Dahl J. Local infiltration with NSAIDs for postoperative analgesia: evidence for a peripheral analgesic action. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2000;44:672–83.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Andersen L, Husted H, Otte K, Kristensen B, Kehlet H. A compression bandage improves local infiltration analgesia in total knee arthroplasty. Acta Orthop 2008;79:806–11.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Winnie A, Ramamurthy S, Durrani Z. The inguinal paravascular technic of lumbar plexus anesthesia: the 3-in-1 block. Anesth Analg 1973;52:989–96.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Affas F, Nygårds EB, Stiller CO, Wretenberg P, Olofsson C. Pain control after total knee arthroplasty: a randomized trial comparing local infiltration anesthesia and continuous femoral block. Acta Orthop; 2011May11. [Epub ahead of print].Search in Google Scholar

[16] Salonen M, Haasio J, Bachmann M, Xu M, Rosenberg P. Evaluation of efficacy and plasma concentrations of ropivacaine in continuous axillary brachial plexus block: high dose for surgical anesthesia and low dose for postoperative analgesia. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2000;25:47–51.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Stringer B, Singhania A, Sudhakar J, Brink R. Serumandwounddrain ropivacaine concentrations after wound infiltration in joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2007;22:884–92.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Toftdahl K, Nikolajsen L, Haraldsted V, Madsen F, Tønnesen E, Søballe K. Comparison of peri- and intraarticular analgesia with femoral nerve block after total knee arthroplasty: a randomized clinical trial. Acta Orthop 2007;78:172–9.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Tucker G. Pharmacokinetics of local anaesthetics. Br J Anaesth 1986;58:717–31.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Souter A, Fredman B, White P. Controversies in the perioperative use of nonsterodial antiinflammatory drugs. Anesth Analg 1994;79:1178–90.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Fragen RJ, Stulberg SD, Wixson R, Glisson S, Librojo E. Effect of ketorolac tromethamine on bleeding and on requirements for analgesia after total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1995;77(7):998–1002.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Laisalmi M, Teppo AM, Koivusalo AM, Honkanen E, Valta P, Lindgren L. The effect of ketorolac and sevoflurane anesthesia on renal glomerular and tubular function. Anesth Analg 2001;93(5):1210–3.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Essving P, Axelsson K, Kjellberg J, Wallgren O, Gupta A, Lundin A. Reduced hospital stay, morphine consumption, and pain intensity with local infiltration analgesia after unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Acta Orthop 2009;80:213–9.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Cassuto J, Wallin G, Högström S, Faxén A, Rimbäck G. Inhibition of postoperative pain by continuous low-dose intravenous infusion of lidocaine. Anesth Analg 1985;64:971–4.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Groudine S, Fisher H, Kaufman RJ, Patel M, Wilkins L, Mehta S, Lumb PD, et al. Intravenous lidocaine speeds the return of bowel function, decreases postoperative pain, and shortens hospital stay in patients undergoing radical retropubic prostatectomy. Anesth Analg 1998;86:235–9.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Koppert W, Weigand M, Neumann F, Sittl R, Schuettler J, Schmelz M, Hering W. Perioperative intravenous lidocaine has preventive effects on postoperative pain and morphine consumption after major abdominal surgery. Anesth Analg 2004;98:1050–5.Search in Google Scholar

© 2011 Scandinavian Association for the Study of Pain

Articles in the same Issue

- Editorial comment

- Keeping an open mind: Achieving balance between too liberal and too restrictive prescription of opioids for chronic non-cancer pain: Using a two-edged sword

- Educational case report

- Chronic non-cancer pain and the long-term efficacy and safety of opioids: Some blind men and an elephant?

- Editorial comment

- National versions of fibromyalgia questionnaire: Translated protocols or validated instruments?

- Original experimental

- Validation of a Finnish version of the Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (Finn-FIQ)

- Editorial comment

- The impact of chronic pain—European patients’ perspective over 12 months

- Original experimental

- The impact of chronic pain—European patients’ perspective over 12 months

- Editorial comment

- Pressure pain algometry — A call for standardisation of methods

- Original experimental

- Experimental pressure-pain assessments: Test-retest reliability, convergence and dimensionality

- Editorial comment

- High prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and pain sensitization in two Scandinavian samples of patients referred for pain rehabilitation

- Clinical pain research

- The traumatised chronic pain patient—Prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder - PTSD and pain sensitisation in two Scandinavian samples referred for pain rehabilitation

- Editorial comment

- Local infiltration analgesia (LIA) and repeated bolus or continuous infusion peripheral nerve blocks for acute postoperative pain: Be ware of local anaesthetic toxicity, especially in elderly patients with cardiac co-morbidities!

- Clinical pain research

- A randomized study comparing plasma concentration of ropivacaine after local infiltration analgesia and femoral block in primary total knee arthroplasty

- Editorial comment

- Computer work can cause deep tissue hyperalgesia: Implications for prevention and treatment

- Original experimental

- Deep tissue hyperalgesia after computer work

Articles in the same Issue

- Editorial comment

- Keeping an open mind: Achieving balance between too liberal and too restrictive prescription of opioids for chronic non-cancer pain: Using a two-edged sword

- Educational case report

- Chronic non-cancer pain and the long-term efficacy and safety of opioids: Some blind men and an elephant?

- Editorial comment

- National versions of fibromyalgia questionnaire: Translated protocols or validated instruments?

- Original experimental

- Validation of a Finnish version of the Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (Finn-FIQ)

- Editorial comment

- The impact of chronic pain—European patients’ perspective over 12 months

- Original experimental

- The impact of chronic pain—European patients’ perspective over 12 months

- Editorial comment

- Pressure pain algometry — A call for standardisation of methods

- Original experimental

- Experimental pressure-pain assessments: Test-retest reliability, convergence and dimensionality

- Editorial comment

- High prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and pain sensitization in two Scandinavian samples of patients referred for pain rehabilitation

- Clinical pain research

- The traumatised chronic pain patient—Prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder - PTSD and pain sensitisation in two Scandinavian samples referred for pain rehabilitation

- Editorial comment

- Local infiltration analgesia (LIA) and repeated bolus or continuous infusion peripheral nerve blocks for acute postoperative pain: Be ware of local anaesthetic toxicity, especially in elderly patients with cardiac co-morbidities!

- Clinical pain research

- A randomized study comparing plasma concentration of ropivacaine after local infiltration analgesia and femoral block in primary total knee arthroplasty

- Editorial comment

- Computer work can cause deep tissue hyperalgesia: Implications for prevention and treatment

- Original experimental

- Deep tissue hyperalgesia after computer work