Abstract

This article focuses on research into two ways of repairing holes found on parchment of Late Antique manuscripts. Their appearance and the reasons for these repairs are analysed and illustrated using the example of the Vienna Dioscorides, a Byzantine manuscript dated to 512. The reconstruction of the manufacturing method of thin Late Antique parchment prepared from lambskins shows clearly that these repairs were an important part of the production process and not subsequent repairs. Conservation of parchment may in some cases have a serious effect on the perception of this important technological evidence.

Zusammenfassung

Im Mittelpunkt dieses Artikels steht die Erforschung von zwei Arten der Reparatur von Löchern im Pergament spätantiker Handschriften. Ihr Aussehen und die Gründe für diese Reparaturen wurden analysiert und am Beispiel der byzantinischen Handschrift der Wiener Dioskurides aus dem Jahr 512 illustriert. Die Rekonstruktion des Herstellungsverfahrens von dünnem, spätantikem Pergament aus Lammhäuten zeigt deutlich, dass diese Reparaturen ein wichtiger Teil des Herstellungsprozesses waren und keine nachträglichen Reparaturen. Die Konservierung von Pergament kann sich in manchen Fällen gravierend auf die Wahrnehmung dieses wichtigen technologischen Zeugnisses auswirken.

1 Introduction

Most of us are familiar with fine parchment used for written and often opulently decorated medieval manuscripts, for example the famous Bible of king Wenceslaus IV from 1390 (Austrian National Library, Cod. 2759–2764) written in Prague on skilfully prepared calf parchment. It may come as a surprise to some of us that this type of parchment is a result of almost thousand years of development and that at the opposite end of this timeline, we would find very thin Late Antique sheep parchment which has unique characteristics and was prepared by a very peculiar method. While some recipes for the preparation of parchment from the medieval period have been preserved, little is known about the manufacture of parchment in the Late Antiquity (Johnson 1970). An example for Late Antique sheep parchment of the highest quality can be found in the Codex Vaticanus (The Vatican Library, Cod. Gr.1209), which was written in Greek in the Mediterranean around 350 AD at a time when parchment began to be regularly used as a substitute for papyrus.

2 Visual Analyses of Parchment

In the absence of written source literature, there are still ways to reconstruct the method of parchment production thorough visual analyses. These include observation of the traces of several types of tools which were left on the surface of parchment during its manufacture. Observations of the anatomy of the “beasts” visible on the parchment folia provide additional information about the animals whose skins have been processed, and also help us to understand the formation of the quires of manuscripts. The most complete understanding can be achieved in combination with experimental parchment making, as repeated successful experiments shed light on various theories. If parchment folia of the manuscript are well prepared and without defects, the possibility to understand the method of parchment production is extremely limited. On the other hand, visual analyses of folia that contain some imperfections, such as holes, tears, or an uneven surface, can yield surprising results.

Holes are one of the most common imperfections found on parchment. Smaller holes are usually left unnoticed but larger holes could cause complications in the next steps of the parchment-making process and seriously affect the final quality of the product.

A close observation of areas near the holes usually provides valuable information because this sensitive area differs from the rest of surface-treated parchment and can often help to understand how parchment was prepared, to identify the type of animal or to recognize hair and flesh side of the skin.

Until recently, the various imperfections that we find on the folia of parchment manuscripts, especially the holes, were interpreted only as “interesting features” which mainly received attention because of their sometimes bizarre shapes (and equally bizarre ways of repairs), respectively because of interactions between scribes and holes since scribes had to find a way to deal with the defective material (Kwakkel). One of the exceptions that underline the importance of the correct interpretation of the various traces in parchment is Christopher Clarkson’s pioneering article, aptly titled “The Nature of the Beast” (Clarkson 1992). If holes and other imperfections in parchment and repair methods are properly analysed, we might gain much more complex information about the technology of the manufacture of parchment, about the animals from which skins they were prepared and the history of the production of the manuscripts (Fiddyment et al. 2019).

3 Late Antique Parchment

My definition as well as the description and dating of Late Antique parchment rely on the visual examination of parchment in original manuscripts which were produced in the Mediterranean region in the territory of both the Western and Eastern Roman Empires (Appendix) and date mostly from the historical period of the fourth to seventh centuries. Until recently, the parchment of the Late Antique manuscripts was very often described as vellum (calf parchment), and in many records or articles this designation persists (Vnouček 2021). The preparation method of Late Antique parchment could only be properly understood by a thorough and detailed study of existing manuscripts and especially by repeated attempts to reconstruct them with the help of experimental parchment-making. Although it now seems that the method of manufacture of Late Antique parchment has been successfully revealed, a lot of details remain unknown or swathed in mystery (Vnouček 2019, et al. 2020, 2021).

The most typical characteristic of Late Antique parchment is that it is made from lambskins (skins of young sheep) whose epidermis (the upper layer on the hair side of skin) is peeled off after stretching the skin on a frame. Removal of the epidermis and thorough cleaning of the skin’s surface make both sides of the parchment exceptionally smooth and glossy. The hair and the flesh side of the parchment have almost the same colour which makes it difficult to distinguish them. The parchment is very thin (with a thickness in certain areas of the skin even as low as 0.045 mm) and therefore very reactive to changes of the humidity in the air. If parchment is preserved in its original condition (not affected by conservation treatment), thin folia start to curl almost immediately after the opening of the codex. One of most typical characteristics of Late Antique parchment is the “epidermal patch repair”, a specific form of hole repair which was implemented almost exclusively in this period. It was applied as a quick repair to randomly appearing holes in the skin that had already been stretched on the frame, while the belly button repair was applied to holes existing before the skin was stretched because the method must be thoroughly prepared. This article’s focus is on these two types of repairs. For a more detailed description of the preparation of parchment we refer to the article by Hofmann et al. in this issue of Restaurator.

It seems that the knowledge of preparation of Late Antique parchment has been gradually lost in the centuries after the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 in the same way as knowledge of some other highly specialized technologies which flourished during Late Antiquity and the Early Byzantine period.

3.1 Origins of Holes in Parchment

Before the methods of repairing holes in Late Antique parchment will be described, it is important to discuss how holes appear in parchment. It seems logical that defective skins with holes were avoided and sorted out shortly after the animals were skinned. As the lambs were slaughtered at a young age, it can be expected that their skins were without any blemish. However, holes might appear later, when the pelt which had been first soaked for several days in lime starts to be de-haired on the parchment-maker’s beam. Some small holes might already have come from the skinning of the animals but were for the time being hidden underneath the hair, while new holes can appear during the process of the cleaning of the flesh side of the skin by an improper movement of the parchment-maker operating the very sharp knife. In addition to the holes created during the cleaning process, there is the potential for new holes to appear when the skin is stretched on the frame.

A special risk for the creation of holes was posed by the flay cuts located on the flesh side of the skin, which originate from the skinning of the animal by the butcher. The flay cuts can be found especially around the animal’s belly and axillae. During the tensioning of the skin, flay cuts can appear in the places where the butcher’s knife penetrated too deep into the skin so that a hole developed unexpectedly; often in the shape of an eye (Tancous 1986) (Figure 1).

The Vienna Dioscorides, Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Cod. Med. gr. 1, fol. 236v. Repair patch over the hole created by the opening of one of the many flay cuts (in transmitted light).

Another type of hole can suddenly start to appear during the peeling of the epidermis. Again, holes are created mostly in areas of the former axillae and belly edges, where the skin is thinner. More holes can appear as a result of a combination of several factors, for example in a situation when the epidermis is peeled off over the area where flay cuts are located on the skin. Since holes enlarge quickly during the stretching of the skin, immediate reaction is required, otherwise holes can get out of control and the skin could be completely ruined.

3.2 Epidermis Patches

Applying an epidermis patch over the hole is the fastest way to prevent uncontrolled enlargement of holes during tensioning of skins on the frame. For this purpose, the parchment-maker has a large amount of freshly removed epidermis tissue available which can be torn into smaller pieces and used as patches (Figure 2). The parchment-maker must apply the patch onto the problematic area very quickly. One larger patch can stabilize the formation of an accumulation of smaller holes. Larger individual holes might be repaired with one single patch, often of triangular shape.

The parchment-making experiment.

(a) Peeling of the epidermis layer from the hair side of the lambskin. (b) Epidermis gets easily ripped but smaller pieces can be reused for repairs. (c) Transparent epidermis tissue in water ready for the reuse as patches.

The epidermis patch is always applied on the hair side of the peeled skin. In a way, the epidermis layer is returned to its original position in the structure of the skin but placed in a different area on the grain surface. No additional glue is applied, as both parts of the future joint are adhered with a sticky viscous fluid called ground substance, which is part of the dermal structure (Reed 1972). A carefully applied patch will stick around the edges of the developing hole and immediately stabilize the area. Even though the epidermis tissue is very thin when it is glued back on the skin, it creates an extraordinarily strong laminate, which can withstand further stretching of the skin on the frame. Since peeled skin is very thin, the parchment dries quickly. If the patch is properly smoothed, the repair can withstand the rising tension connected with the final drying of the parchment (Vnouček 2019, 2021).

This type of repair can be also found in purple Late Antique manuscripts (Rabitsch 2020). My own experiments with parchment dyeing have shown that even if the parchment with the epidermis patch repairs is re-moistened with purple dye during dyeing in the vat for several minutes, the patch is not affected at all, and the dye penetrates right through both layers.

When the parchment is completely dry, the epidermis tissue becomes transparent. Despite its extreme thinness, it is strong enough to be written or painted on. It is also interesting to observe the mutual reaction of the parchment and the applied epidermis patch in Late Antique manuscripts. The epidermis patch always partly deforms the surface of the repaired parchment, creating a specific form of undulation that is well visible, especially with the help of raking light (Figures 3 and 4).

The parchment-making experiment.

(a) Dried epidermis patch on the hair side of the parchment (in raking light). (b) The flesh side of the parchment (in raking light). Notice how dried patch shapes the surface of the parchment. (c) The patch applied on the hole in the parchment that was later dyed purple.

The Vienna Dioscorides.

(a) Epidermis patch partly covered by the illumination on the hair side of the parchment, folio 35v. (b) Identical epidermis patch seen from the flesh side of the parchment, folio 35r. (c) Epidermis patch completely covered by the illumination on the hair side of the parchment, folio 2v (d) Identical epidermis patch seen from the flesh side of the parchment, folio 2r.

Visual analyses of repairs of parchment in about twelve Late Antique manuscripts lead me to the conclusion that the application of patches has a purely functional character. It aims to stabilize the endangered area of skin during the stretching on the frame. The patches are only applied during the wet stage of the process. The assumption that application of patches is not an aesthetic decision is also supported by examples of patches prepared from an epidermis with much darker pigmentation than the parchment on which it was applied. The parchment maker most probably did not have enough time to match the colours properly (Figure 5).

The Vienna Dioscorides.

(a) Remnants of unpeeled epidermis from skin of lamb with the dark hairs left on the lower margin of the folio 35v. (b) Epidermis patch from skin of lamb with the dark hairs applied on the folio 212v.

Spare removed epidermis can be pinned and stretched and left to dry so that it could be theoretically used for repairs on parchment in a dry stage. However, it would be necessary to use adhesive for this purpose, which would almost certainly leave some marks around the edges of the patch. I did not find any example of this potentially possible type of repair on parchment of the Late Antique manuscripts.

3.3 Epidermis Patches in Late Byzantine and Greek Manuscripts

Parchment of later Byzantine and especially Greek manuscripts from the 10th - 13th centuries differs from the quality of the parchment used in early Byzantine manuscripts, but also shows certain similar characteristics. Parchment was made of sheepskin during that period but most of it was prepared in a much coarser way and the parchment is often very thick and oily. However, patches for hole repair are sometimes made from recycled epidermis membrane. In manuscripts, folios made of very thin parchment may be intermingled with folios made of thicker parchment. It may be concluded that some steps in the preparation of parchment, including the splitting of sheepskins, had been preserved in a modified form in the Late Byzantine period. However, these random examples cannot be compared in quality and in scale of production with the Late Antiquity period.

3.4 Belly Button Repair

The belly button repair is another technique for repairing holes in thin parchment. It is carried out during the wet stage of parchment preparation before the skin is stretched on the frame. The area around the hole is first seized, twisted, and tied around with a thread that is firmly knotted. When the parchment is stretched, a specific pattern reminiscent of a belly button appears on the hair side of the skin around the former hole. An additional epidermis patch placed over the area of the newly created belly button very often completes the repair. The ground substance in the epidermis patch acts as natural glue that secures the knot as the skin dries. After the skin on the frame has dried, the hardened knot is trimmed off with a sharp knife and a typical circular cut remains on the surface of the flesh side of the parchment. The repaired area is never completely flat, due to the distortion caused by the twisting of the skin (Figures 6 and 7). If the knot is not tightened enough, the skin will be partially loosened when it starts to dry and contract on the frame, which leads to the creation of additional smaller holes around the knot (Figure 10).

The parchment-making experiment. Two belly button repairs during the process.

(a) Two holes secured by knots on the flesh side of the wet parchment (before stretching). (b) Two secured holes seen on the hair side of wet parchment (before stretching). (c) One of the holes secured by an additional epidermis patch seen on the hair side of wet parchment (during stretching). (d) Final appearance of two holes secured by the belly button repairs on dry parchment.

The parchment-making experiment: belly button repair.

(a) Securing the knot before the removal on the flesh side of dry parchment. (b) Appearance of the cut on the surface of parchment after the knot was trimmed away.

No matter how complicated or even bizarre this type of repair may seem, it definitely worked well for sealing the holes in very thin Late Antique parchment. The same method was used successfully for repairing long tears in parchment. In this case, a series of belly button knots were placed along the tear in a row. Although this repair did not completely seal the tear, it fulfilled its function and joined the two parts of the parchment together (Vnouček 2019).

It should be noted that holes and especially tears in thin Late Antique parchment could not be sewn with a thread. The sewing method, which was successfully used later in the Middle Ages to repair holes and tears in skins does not work with thin peeled lambskins. Damaged lambskin can be sutured, but each needle puncture creates additional holes that enlarge when the skin is subjected to tension on the frame. When the parchment dries, the new holes act as a perforated line that divides the parchment into two parts.

4 The Vienna Dioscorides

The Vienna Dioscorides (Vienna, Austrian National Library, Cod. Med. gr. 1) is one of the earliest and most accurately dated example of a manuscript that contains both types of parchment repair. The manuscript was made in Byzantine (Constantinople) around 512 for the Imperial Princess Anicia Juliana of Byzantine, a dedication acrostic is on the verso of folio 6. It is a compendium of six pharmacological and scientific works: a herbarium, minor medical works, and books about birds. It is written in Greek uncial and contains 485 folios with more than 496 images of plants and animals. As one of the oldest illustrated manuscripts with a secure origin and date, this Greek codex is of particular importance in the history of art.

The parchment of this manuscript has been prepared by the Late Antique method; see also the article by Hofmann et al. in this issue. Although the quality of the parchment differs in some respects from that of other contemporary Late Antique manuscripts, it has all the main expected features. Probably the most striking observation is the visible difference in colour between the hair side, which is often more yellowish, and the flesh side, which is very white. Visual observation and eZooMS analysis identified the parchment as sheepskin with the characteristic features of Late Antique production. The epidermis has been peeled off and the holes are repaired with both epidermis patches and the belly button repair. The dimensions of the folia vary a lot throughout the text block, ranging from about 370 to 391 mm in length and from 300 to 320 mm in width. Some folia have uneven edges, as many skins have been used to their utmost limits, including parts of the animal’s belly and flanks. The position of the former flanks of the animals in the text block of the manuscript varies a lot, as large areas of bellies are often included. These areas can be found either at the front margins, indicating a vertical position of the spine of the animal, or at the lower margins indicating a horizontal position of the animal spine. Quite unusual, flanks of the animals can also be found at the top margins of some folios. This means that skins of large and smaller animals of different age were combined without specific order. This is also confirmed by the wide variety of thickness measurements, which range from 0.104 to 0.181 mm. The quality of the parchment throughout the text block is not very consistent and it seems to have been assembled from different batches of parchment.

Originally, most of the holes were repaired using transparent epidermis patches: A total of 157 holes of various sizes, on six of which parts of the illustrations are preserved. The Vienna Dioscorides also contains nine very interesting and some quite large examples of belly button repairs (Figure 8). The ratio of these two types of repairs is about 17:1, which roughly corresponds to the proportion of these two types of repairs in some other Late Antique manuscripts.

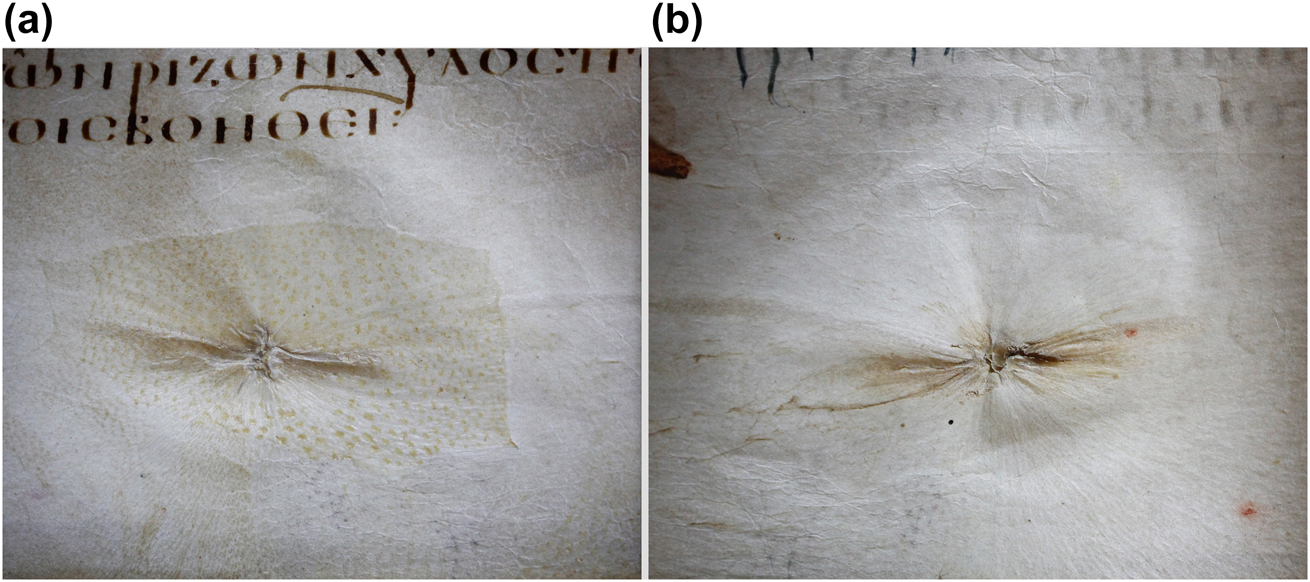

The Vienna Dioscorides, folio 175.

(a) Belly button repair seen from the hair side of parchment. (b) Belly button repair seen from the flesh side of parchment.

4.1 Conservation Treatment by Otto Wächter

In the 1960s, the manuscript received a very thorough restoration treatment by Otto Wächter at the conservation workshop of the Austrian National Library in Vienna. Folios were moistened and relaxed, stretched and sprayed with a consolidation solution, and missing parts of the folios were filled in with new parchment. Some of the original patch repairs of holes were reinforced by a layer of goldbeater’s skin (Wächter 1962).

In his article discussing the conservation of the manuscript, Wächter did not specifically describe the original method of parchment preparation, or the type of the animal skins used. He assumed that repairs of holes had been carried out using goldbeater’s skin which was applied with parchment glue on finished dry parchment as part of the preparation for writing and painting of the illustrations.

Conservation treatment of original hole repairs in Late Antique manuscripts is a specific problem. Due to the extent of conservation of the Vienna Dioscorides and drastic alteration that occurred to the parchment, it can be expected that almost none of the major original repairs of the parchment has been preserved completely intact. However, because a transparent goldbeater’s skin was used for mending holes, the result of the repair remains visually “transparent”. Due to the transparency of both materials, it is possible to distinguish the two individual layers of repairs. The new repair patches from goldbeater’s skin have mostly rectangular shapes and therefore do not conflict with the uneven shape of original patches prepared from epidermis tissue. In addition, the original epidermis patch is easily recognizable because it always contains partially visible hair follicle patterns, which is one of its typical features, while goldbeater’s skin, which is made from the appendices of cattle, is completely transparent and without any pattern on the surface. It seems that Wächter did not remove the damaged parts of original patches during his conservation treatment but only supported them with this new material. This can be seen at least in areas where parts of the illustrations (paintings of flowers) are preserved on the surface of the epidermis repair patches (Figures 9 and 10).

The Vienna Dioscorides, folio 242.

(a) Detail of damaged original repair patch (the fragment with painting over it) reinforced by the goldbeater’s skin during the conservation treatment in 1960. Seen from the flesh side of parchment. (b) Damaged original epidermis patch (irregular triangular shape) was reinforced by a patch prepared from the goldbeater’s skin (deltoid shape). Seen from the hair side of parchment.

The Vienna Dioscorides, folio 88v. Loose belly button repair which had opened up with small holes (seen from the hair side of parchment). The overlapping repair patch with goldbeater’s skin was applied during conservation treatment in 1960.

4.2 Problems with Conservation Treatment of Holes and Their Original Repairs

The empty holes on the folia of parchment manuscripts seem to have attracted the attention of bookbinders and later conservators for a long time. Covering complete and undamaged holes is a rather curious practice, as most of these imperfections are not harmful in terms of preservation. Perhaps this has to do with a change in aesthetic perceptions in a period when manuscripts were restored to look “even better” than when they were newly made. Some of these types of repairs might have been introduced during rebinding of manuscripts as early as the Renaissance and continued until almost the last quarter of the 20th century.

A major problem is the use of opaque parchment or paper patches typically using the full thickness of parchment, which partially obscure the evidence of the repair process (Vnouček et al. 2020, 44) (Figure 11)

The Codex Bezae, Cambridge University Library, MS Nn.2.41., folio 199v. New opaque repair patch applied over the hole during conservation treatment by Sandy and Elizabeth Cockerell in years 1962–1965. The rest of the original epidermis repair patch is visible around the hole on the hair side of the parchment. Reproduced by kind permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library.

An even worse situation occurs when entire parchment folia are covered by various lamination methods, including the use of silk gauze (Figure 12a and b). There is no doubt that these types of conservation treatments, mostly executed in the 1960s, aimed at preserving the text, often heavily damaged by ink corrosion, but unfortunately, they were undertaken at all costs and often with counterproductive results. In addition to covering the holes and obscuring various traces of parchment production, the original appearance of the parchment surface, its natural flexibility and other important characteristics have been lost forever.

Liber Pastoralis S. Gregorii, Troyes, Bibliothèque Municipale, MS 504, f. 26r.

(a) The belly button repair covered by the silk gauze after the conservation of manuscript in BNF in Paris in 1960. Flesh side of the parchment. (b) Despite the conservation treatment is still possible to observe that repaired area is never completely flat creating on the hair side of the parchment protrusion in the shape of little volcano.

5 Conclusion

The two types of repairs described in this article are characteristic not only of the parchment of the Vienna Dioscorides but also appear quite often in other manuscripts produced in the sixth and seventh century in Italy. Because parchment of very early Late Antique manuscripts from the 4th century is almost without imperfections, it can be assumed that a more frequent occurrence of these two types of repairs is somehow associated with the decline of parchment production. The specific practices of producers in different geographical areas and the use of skins from specific breeds of animals may also play a key role. Observation of one of these types of repair can almost serve as identification of Late Antique parchment. Moreover, it seems that individual stages of the development or improvement of distinct types of parchment repair might perhaps even help to an approximate dating of the production of manuscripts.

Unless absolutely necessary, the original holes and other imperfections in the parchment should not be covered or modified during the conservation treatment but should be treated with particular care to keep them intact for future research as important evidence of the technology of manufacture of parchment. This applies to manuscripts of all types, not just those produced during the Late Antique period.

Funding source: Innovation Horizon 2020 http://dx.doi.org/10.13039/501100000781

Award Identifier / Grant number: 787282

Acknowledgments

The text of this article is based in part on information from a dissertation The Language of Parchment. Tracing the evidence of changes in the methods of manufacturing parchment for manuscripts with the help of visual analyses, submitted to the University of York in 2019. The author wishes to express his thanks to all libraries and institutions that allowed him to study the original manuscripts (see also Appendix). Special thanks go to Gillian Fellows-Jensen for her careful corrections to my English text, Sigrid Eyb-Green and both peer reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions.

-

Research funding: The text was further expanded with new results obtained from the Beasts to Craft (B2C) research project. This project has received funding from the European Union’s EU Framework Programme for Research and Innovation Horizon 2020 under Grant Agreement No. 787282.

List of studied Late Antique manuscripts

Manuscripts studied in original:

Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS 286 (Gospels of St. Augustine)

Cambridge, Cambridge University Library, MS Nn. 2. 41. (Codex Bezae)

Cividale, Museo Archeologico, CXXXVIII (Codex Furojuliensis)

Oxford, Bodleian Library, Auct. D. 2. 14 (Gospels of St. Augustine)

Prague, Metropolitan Chapter Library, Cim 1 (Gospel of St. Mark)

Rosanno Calabro, Museo dell’ Arcivescovado, (Codex Purpureus Rossanensis)

Uppsala, University Library, DG 1, (Codex Argenteus)

Vatican City, Bibliotheca Apostolica Vaticana, Cod. Gr. 1209 (Codex Vaticanus B), Vat. Lat. 7223 (Codex Claromontanus h)

Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Cod. Med. gr. 1 (The Vienna Dioscurides), Cod. Theol. gr. 31 (Vienna Genesis)

Troyes, Bibliothèque Municipale MS 504 (Pastoral care by Pope Gregory)

Manuscripts studied in digitized form:

London, British Library, Add. MS 4372 (Codex Sinaiticus), Royal MS 1 D VIII. (Codex Alexandrinus), Harley MS 1775 (Harley Gospels)

References

Clarkson, C. 1992. “Rediscovering Parchment: The Nature of the Beast. Paper Conservator Vellum and Parchment.” The Journal of the Institute of Paper Conservation 16: 5–26.10.1080/03094227.1992.9638571Search in Google Scholar

Fiddyment, S., M.D. Teasdale, J. Vnouček, É. Lévêque, A. Binois, and M.J. Collins. 2019. “So You Want to Do Biocodicology? A Field Guide to the Biological Analysis of Parchment.” Heritage Science 7: 35, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-019-0278-6.Search in Google Scholar

Johnson, G. R. 1970. “Ancient and Medieval Accounts of the ‘Invention’ of Parchment.” California Studies in Classical Antiquity 3: 120–2.10.2307/25010602Search in Google Scholar

Kwakkel, E. Parchment (The Good, the Bad and the Ugly). https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/medieval-world/medieval-book/making-medieval-book/a/parchment-the-good-the-bad-and-the-ugly (accessed February 7, 2022).Search in Google Scholar

Rabitsch, S., I. Boesken Kanold, and C. Hofmann. 2020. “Purple Dyeing of Parchment.” In The Vienna Genesis: Material Analysis and Conservation of a Late Antique Illuminated Manuscript on Purple Parchment, edited by Hofmann, C., 71–101. Wien: Böhlau.10.7767/9783205210580.71Search in Google Scholar

Reed, R. 1972. Ancient Skins, Parchments and Leathers, 16–9. London and New York: Seminar Press.Search in Google Scholar

Tancous, J. 1986. Skin, Hide and Leather Defects, 2nd ed. Cincinnati: Leather Industries of America Laboratory University of Cincinnati and Leather Industries of America, Inc.Search in Google Scholar

Vnouček, J. 2019. The Language of Parchment. Tracing the Evidence of Changes in the Methods of Manufacturing Parchment for Manuscripts with the Help of Visual Analyses. Ph.D. thesis. York: University of York.Search in Google Scholar

Vnouček, J., S. Fiddyment, A. Quandt, S. Rabitsch, M. Collins, and C. Hofmann. 2020. “The Parchment of the Vienna Genesis: Characteristics and Manufacture.” In The Vienna Genesis: Material Analysis and Conservation of a Late Antique Illuminated Manuscript on Purple Parchment, edited by Hofmann, C., 35–69. Wien: Böhlau.10.7767/9783205210580.35Search in Google Scholar

Vnouček, J. 2021. “Not all that Shines like Vellum Is Necessarily So.” Care and Conservation of Manuscripts 17: 27–59.Search in Google Scholar

Wächter, O. 1962. “The Restoration of the Vienna Dioscorides.” Studies in Conservation 7 (1): 22–6.10.1179/sic.1962.005Search in Google Scholar

© 2022 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Preface

- Editorial

- Original Works

- The Vienna Genesis: An Example of Late Antique Purple Parchment

- Dyeing Parchment Infills

- Novel Approaches for Opaque Reconstituted Parchment

- Iron Gall Ink Corrosion on Parchment. Preliminary Evaluation of Treatment Methods Using Aqueous Solutions

- Hole Repairs as Proof of a Specific Method of Manufacture of Late Antique Parchment

- Technical Notes

- Investigating the Properties of Folded Parchment – A Preliminary Study

- Non-Invasive Physico-Chemical and Biological Analysis of Parchment Manuscripts – An Overview

- Original Work

- Insights From the NANOforArt Project: Application of Calcium-Based Nanoparticle Dispersions for Improved Preservation of Parchment Documents

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Preface

- Editorial

- Original Works

- The Vienna Genesis: An Example of Late Antique Purple Parchment

- Dyeing Parchment Infills

- Novel Approaches for Opaque Reconstituted Parchment

- Iron Gall Ink Corrosion on Parchment. Preliminary Evaluation of Treatment Methods Using Aqueous Solutions

- Hole Repairs as Proof of a Specific Method of Manufacture of Late Antique Parchment

- Technical Notes

- Investigating the Properties of Folded Parchment – A Preliminary Study

- Non-Invasive Physico-Chemical and Biological Analysis of Parchment Manuscripts – An Overview

- Original Work

- Insights From the NANOforArt Project: Application of Calcium-Based Nanoparticle Dispersions for Improved Preservation of Parchment Documents