Abstract

Atherosclerosis is an inflammatory disease where activated immune cells are recruited into the artery wall forming artery plaques. Interferon-γ released by T-cells causes macrophage synthesis and release of 7,8-dihydroneopterin, an antioxidant and CD36 down-regulator. 7,8-Dihydroneopterin scavenging of superoxide and hypochlorite generates neopterin, whose measurement has been used as a marker for inflammation in cardiovascular disease. With low oxidative stress levels, 7,8-dihydroneopterin is likely to be the predominant product leading to an underestimate of macrophage activation when measuring neopterin alone. Here we measure both total-neopterin (7,8-dihydroneopterin plus neopterin) and neopterin along with IL-1β, in cardiovascular disease patients presenting with stroke. Plasma neopterin and total neopterin were measured by HPLC in 61 stroke patients undergoing carotid endarterectomy surgery and 61 age-matched controls. Plasma IL-1β was measured by ELISA. Neopterin, total-neopterin, and 7,8-dihydroneopterin were all significantly higher in carotid surgery patients than age-matched controls. Total-neopterin showed the greatest difference between patients and controls (p ≤ 0.001). There was no significant difference in IL-1β levels between the stroke patients and healthy controls. The study shows that macrophage inflammation is elevated in cardiovascular disease patients presenting with stroke and the measurement of total neopterin is a more effective indicator of macrophage activation than neopterin alone.

Abbreviations

- CVD

-

cardiovascular disease

- IL-1β

-

interleukin-1β

- hsCRP

-

high sensitive C-reactive protein

- TIA

-

transitory ischemic attack

1 Introduction

Neopterin has been extensively used as a marker of inflammation in a range of conditions including cardiovascular disease (CVD) [1]. Neopterin is the oxidative product of 7,8-dihydroneopterin, generated by the scavenging of hypochlorite and superoxide [2]. Interferon activation of monocytes and macrophages causes the upregulation of the enzyme cyclohydrolase I which results in 7,8-dihydroneopterin generation within the cells. Both 7,8-dihydroneopterin and neopterin readily exchange across the cellular membranes via the nucleotide transports into the tissues and blood [3]. The detection of the highly fluorescent neopterin is therefore dependent on the oxidation of the 7,8-dihydroneopterin. It is likely that measuring only neopterin in CVD patient plasma may underestimate the level of inflammation occurring if the level of oxidative stress is low within the tissue.

7,8-Dihydroneopterin is a potent oxidant scavenger, capable of out competing the tocopherol (vitamin E) for peroxyl radicals [4]. 7,8-Dihydroneopterin appears to protect macrophage cells from oxidised low density lipoprotein cytotoxicity by scavenging superoxide and hydroxyl radicals [5]. CD36 is down regulated by 7,8-dihydroneopterin through possible inhibition of the lipoxygenase dependent activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPAR-γ) [6]. Both 7,8-dihydroneopterin and neopterin have been demonstrated to be present and generated in atherosclerotic plaques stimulated with γ-interferon [7].

Cardiovascular disease is an inflammatory condition involving the recruitment of immune cells into the artery wall [8]. Plasma neopterin has been shown to increase with the increasing severity of the condition [9]. Neopterin is suggested as a valuable prognostic biomarker in stroke patients, with increased levels associated with the risk of recurrent stroke and poor outcomes [10]. Neopterin has been used to monitor treatment effectiveness and disease progression in ischemic cerebrovascular diseases [11]. Serum neopterin levels are significantly elevated after acute ischemic stroke and are predictive of unfavorable clinical outcomes [12]. Elevated plasma neopterin levels are linked to a worse prognosis in ischemic stroke patients and indicative of further strokes. Plasma neopterin is as an independent predictor of mortality six months following ischemic stroke [13].

Interleukin-1β (IL-1β), an inflammatory cytokine, has been linked to several inflammatory disorders including rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, osteoarthritis, type 2 diabetes, gout, multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease, and cardiovascular disease [14], [15], [16], [17]. IL-1β is generated through the action of the inflammasome on IL-1. Like 7,8-dihydroneopterin, IL-1β, is secreted by macrophages as well as fibroblasts, B lymphocytes, natural killer cells, and smooth muscle cells, and likely contributes to the development of cardiovascular conditions [18]. Inhibiting IL-1β has proven to be an effective method for reducing hypertension by decreasing activity in the sympathetic nervous system [19], 20]. Notably, the neutralization of active IL-1β via an antibody in the Canakinumab Anti-Inflammatory Thrombosis Outcomes Study (CANTOS) led to a notable 17 % decrease in recurrent cardiovascular events [21]. Nevertheless, the specific mechanisms responsible for the cardiovascular benefits of anti-IL-1β treatment are not yet fully understood [22], 23] nor the possible connection with 7,8-dihydroneopterin/neopterin release in cardiovascular disease inflammation. It is unknown whether neopterin or 7,8-dihydroneopterin modulate inflammasome activation and therefore IL-1β expression. 7,8-Dihydroneopterin has been implicated in the downregulation of proteins such as CD36 which have been suggested to cause caspase 1 activation and inflammasome formation through the transport of cholesterol into the cells [24]. The comparison of IL-1β to total neopterin levels may provide further insight into the inflammatory process.

The measurement of just plasma neopterin as an indicator of cardiovascular disease progression, is not sufficient for wide clinical use as the amount of plasma neopterin measured is relatively variable from patient to patient. We suggest that a major factor affecting neopterin based analysis is that it needs to be oxidized to neopterin in vivo from the 7,8-dihydroneopterin originally released by the macrophages. The amount of neopterin generated from 7,8-dihydroneopterin is therefore affected by changing oxidant levels around the macrophages and in the patients’ circulation. In previous clinical studies of inflammation induced injury we have circumvented this problem by measuring both 7,8-dihydroneopterin and neopterin [25]. Neopterin is extremely fluorescent so by converting all the 7,8-dihydroneopterin to neopterin in a plasma sample using triiodide, “total neopterin can be measured” by liquid chromatography [26]. Measuring neopterin in oxidized samples and comparing the value to oxidized “total neopterin” provides a better assessment of immune cell activation.

On this basis, we have examined the plasma level of total neopterin and neopterin in patients presenting for carotid endarterectomy following a stroke to gain a better understanding of the level of inflammation and oxidative stress in these patients and examine whether total neopterin analysis provides a stronger statistical signal of CVD. These stroke patients represent a group of subjects who are experiencing CVD and not just elevated risk factors. We have also measured the plasma levels of IL-1β to see whether this additional marker could increase the utility of the analysis.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study participants

A total of 61 stroke patients presenting for carotid endarterectomy surgery at the Christchurch Hospitals Department of Surgery provided informed consent to participate in the study. Carotid endarterectomy patients were aged between 52 and 89 years and 41 % were female. Plasma from age-matched controls (n = 61) without a cardiovascular disease diagnosis were examined for comparison. Blood plasma samples for non-CVD patients (controls) were recruited by the Christchurch Heart Institute. Health status of the participants including smoking status, blood pressure, diabetes and other health conditions was noted (Table 1).

Analytical model of classification of patients with CVD versus age matched controls.

| Variables | CVD patients (n = 61) | Non-CVD patients (n = 61) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | M = 43, F = 18 | M = 43, F = 18 |

| Age | Min – 52, Max – 89 | Min – 52, Max – 90 |

| Average age | 75 | 75 |

| Smoking (%) | 31 % | 46.7 % |

| High blood pressure | 70 % | 69.3 % |

| Blood pressure | Min – 102/61 | Min – 102/96 |

| Max – 193/74 | Max – 230/120 | |

| Diabetes status (%) | 13 % | 4.8 % |

| BP lowering meds | 62.3 % | 43.5 % |

| Cancer | No data | 29 % |

| Lipid lowering meds | 100 % | 16.1 % |

| Anti-thrombotic meds | 100 % | 19.3 % |

2.2 Sample collection and processing

For stroke patients scheduled for surgery, 5 ml of venous blood was drawn into a citrate tube before anesthetic administration as part of surgery. The blood samples were immediately placed on ice and transported to the University of Canterbury for processing within 2 h of collection. The blood was centrifuged at 2,000 rpm for 10 min at 5 °C. The resulting plasma was aliquoted into sample tubes and promptly frozen at −80 °C until analysis. The control samples were collected in dry ice and immediately stored in −80 °C until further analysis.

2.3 Sample preparation and measurement of neopterin and total neopterin by HPLC

The plasma samples were defrosted and then diluted with and equal volume of ice cold 100 % HPLC grade acetonitrile (ratio 50:50). The mixture was vortexed for 30 s and centrifuged at 20,000g for 10 min at 1 °C to remove plasma protein. The collected supernatant was divided to two portions, one that was directly injected to the HPLC for neopterin analysis, while in the second portion, 7,8-dihydroneopterin was oxidized to neopterin with acidic triiodide as described [26]. After stopping the triiodide induced oxidation with ascorbic acid and further centrifugation, the sample were injected into the HPLC to measure the total neopterin. For both neopterin and total neopterin, 10 μl of treated plasma was analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) on an automated Shimadzu LC20 system with autosampler using a Phenomenex NH2-amino column through a mobile phase consisting of 28 % buffer A (10 mM ammonium acetate with 0.3 % formic acid) and 72 % of acetonitrile at 1 ml/min. Eluted neopterin was detected by fluorescence at an excitation wavelength of 353 nm and an emission wavelength of 438 nm. Peaks were integrated using the Shimadzu analysis software.

Plasma IL-1β levels were measured using the Duo Set Ancillary Reagent Kit sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) supplied by RD systems as specified by the manufacturer.

2.4 Geological information

This study was conducted in Christchurch, New Zealand. All the patients from the cohort were operated on at the Christchurch Hospital, Christchurch, New Zealand and were under the care of the Department of Vascular Surgery.

2.5 Statistical analysis

The collected data was analyzed using GraphPad Prism version 9.0.0 for Windows, a software developed by GraphPad Software based in San Diego, California, USA (www.graphpad.com). Multiple linear regression was used to evaluate the importance of neopterin, total neopterin, 7,8-dihydroneopterin, and IL-1β in determining the inflammatory status of patients with cardiovascular disease, considering their lifestyle and health condition. Independent t-test was used to identify any disparities between two groups, and Pearson’s correlation coefficient to assess the connections between variables. The significance threshold was set at a p < 0.05.

Ethical approval: The research related to human use has been complied with all the relevant national regulations, institutional policies and in accordance the tenets of the Helsinki Declaration and has been approved by the authors’ Institutional Review Board or equivalent committee. Ethics approval (CTY/01/04/036) was obtained from the New Zealand Upper South B Ethics Committee.

Informed consent: Informed consent has been obtained from all individuals included in this study.

3 Results

Blood plasmas were analyzed for neopterin, total neopterin, 7,8-dihydroneopterin and IL-1β levels. The patients and controls were compared based on gender, age, diabetic status, smoking status, whether previously treated for high blood pressure or not.

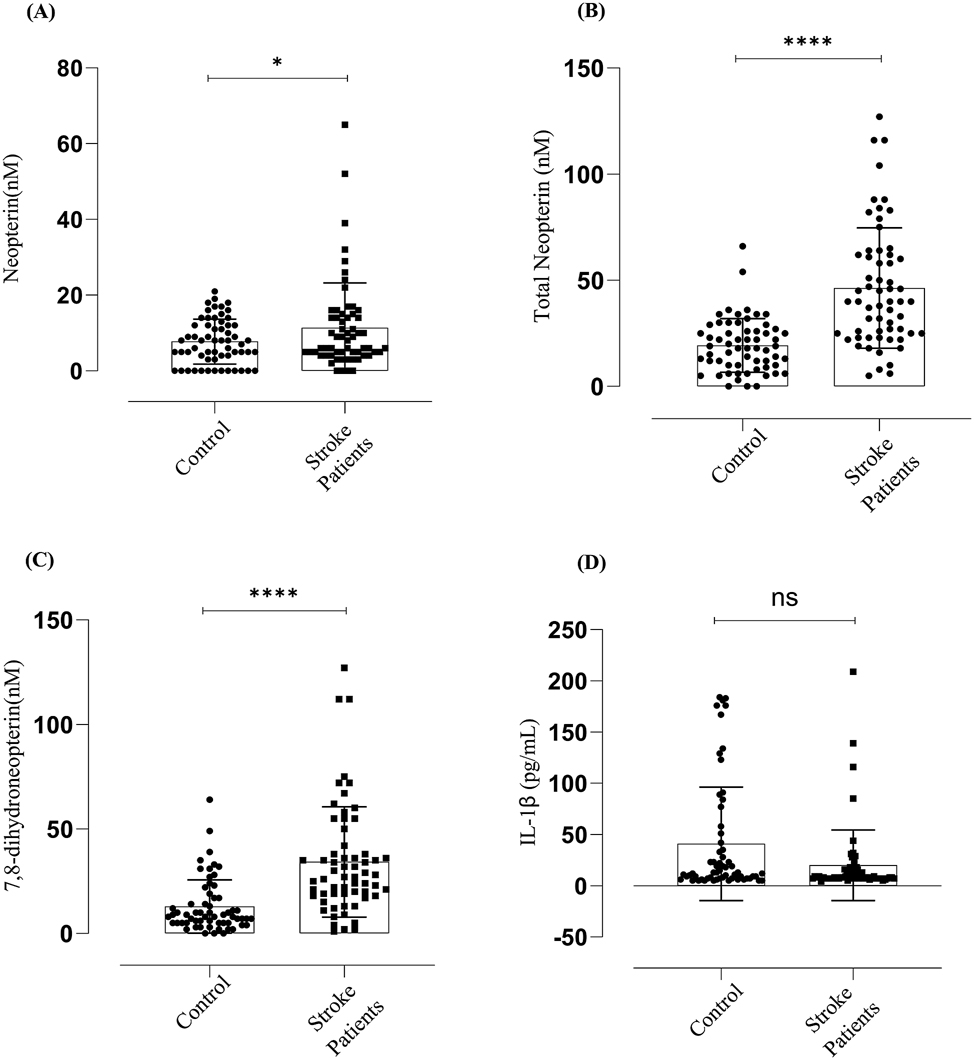

Patients who presented with stroke and admitted for endarterectomy surgery had higher plasma levels of neopterin compared to control (control mean 7.7 nM vs stroke mean 11.3 nM, p = 0.0372) (Figure 1A). The difference between controls and stroke patients was higher for total neopterin (control mean 19.29 nM vs stroke mean 46.37 nM, p = 0.0001) (Figure 1B). Subtracting the neopterin from total neopterin gives 7,8-dihydroneopterin plasma concentration which also was higher in the stroke patients compared to the controls (control mean 12.9 nM vs Stroke mean 34.24 nM) (Figure 1C). The primary finding shows a significant amount of the macrophage neopterin release is not detected using the classical analysis as much of the material is the non-fluorescent 7,8-dihydroneopterin. The data does confirm that cardiovascular disease patients have a significantly higher incidence of oxidative stress, measured as neopterin and immune activation measured at total neopterin compared to control population.

Neopterin, total neopterin, 7,8-dihydroneopterin and IL-1β measured in endarterectomy plasma versus gender matched control plasma. CVD increases oxidative stress and activates macrophages to produce 7,8-dihydroneopterin, but IL-1β levels are not significantly different between the controls and the patients. The results are displayed as mean SD. Neopterin (N = 122, M = 86, F = 36). The significant levels are indicated as p ≤ 0.001 = (****), p ≤ 0.0372 = (*) between the control versus patients. Lines and boxes represent median and interquartile ranges.

Surprisingly, the IL-1β levels (Figure 1D) were not significantly different between the controls and the patients. The mean value for the controls was 40.7 pg/ml compared to the stroke patients mean value of 19.9 pg/ml with a confidence interval of −37.40 to −4.335 which means the difference was not significant. The controls showed a larger spread of values with a standard deviation of 54.96 with the stroke patients having a standard deviation of 34.1.

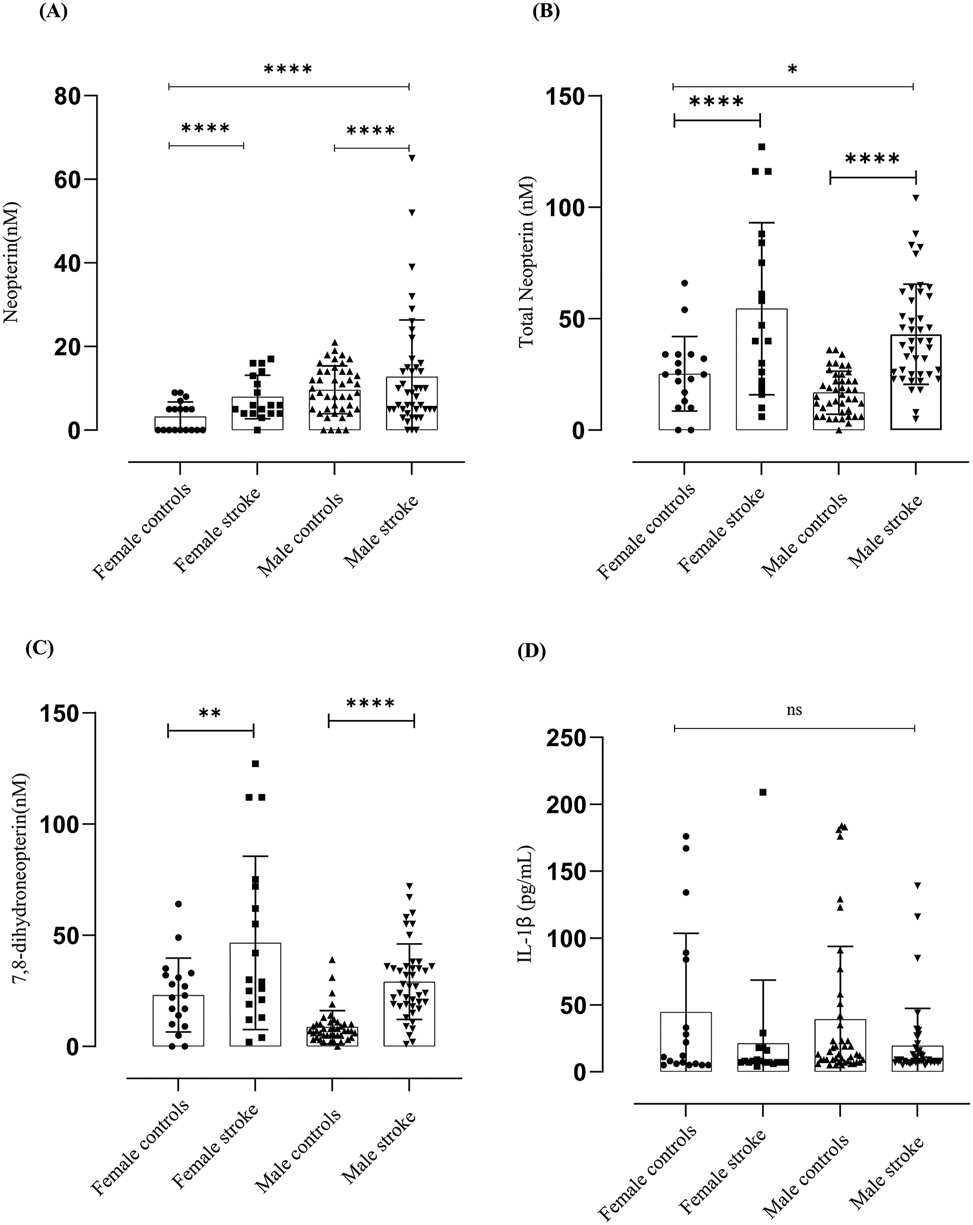

When comparing male patients to female stroke patients male subjects showed higher levels than female subjects (male mean stroke 13.075 nM, female mean stroke 7.944 nM) (Figure 2A).

Neopterin, total neopterin, 7,8-dihydroneopterin and IL-1β measured in endarterectomy plasma versus gender matched control plasma. The results are displayed as mean SD. Neopterin (N = 122, M = 86, F = 36). The significant levels are indicated as p ≤ 0.001 = (***) between the control versus patients and between male and females p ≤ 0.001 = (****). Total neopterin (N = 122, M = 86, F = 36). The significant levels are indicated as p ≤ 0.001 = (***) between the control versus patients and between male and females p ≤ 0.001 = (****). The 7,8-dihydroneopterin levels was calculated by subtracting the neopterin values from the total neopterin values. The results are displayed as mean SD. Total neopterin (N = 122, M = 86, F = 36). The significant levels are indicated as p ≤ 0.0019 = (***) between the control versus patients. Lines and boxes represent median and interquartile ranges.

With total neopterin the reverse was apparent where male female patients had a higher total neopterin compared to male stroke patients (male mean 44.32 nM, female mean 54.5 nM) Figure 2B). This could be due to the levels of 7,8-dihydroneopterin contributing to the total neopterin levels male stroke mean 30.02 nM female stroke mean 46.55 nM) (Figure 2C). The same trend is seen with the age matched control subjects. No significant difference was measured between male and female subjects in the measured IL-1β levels.

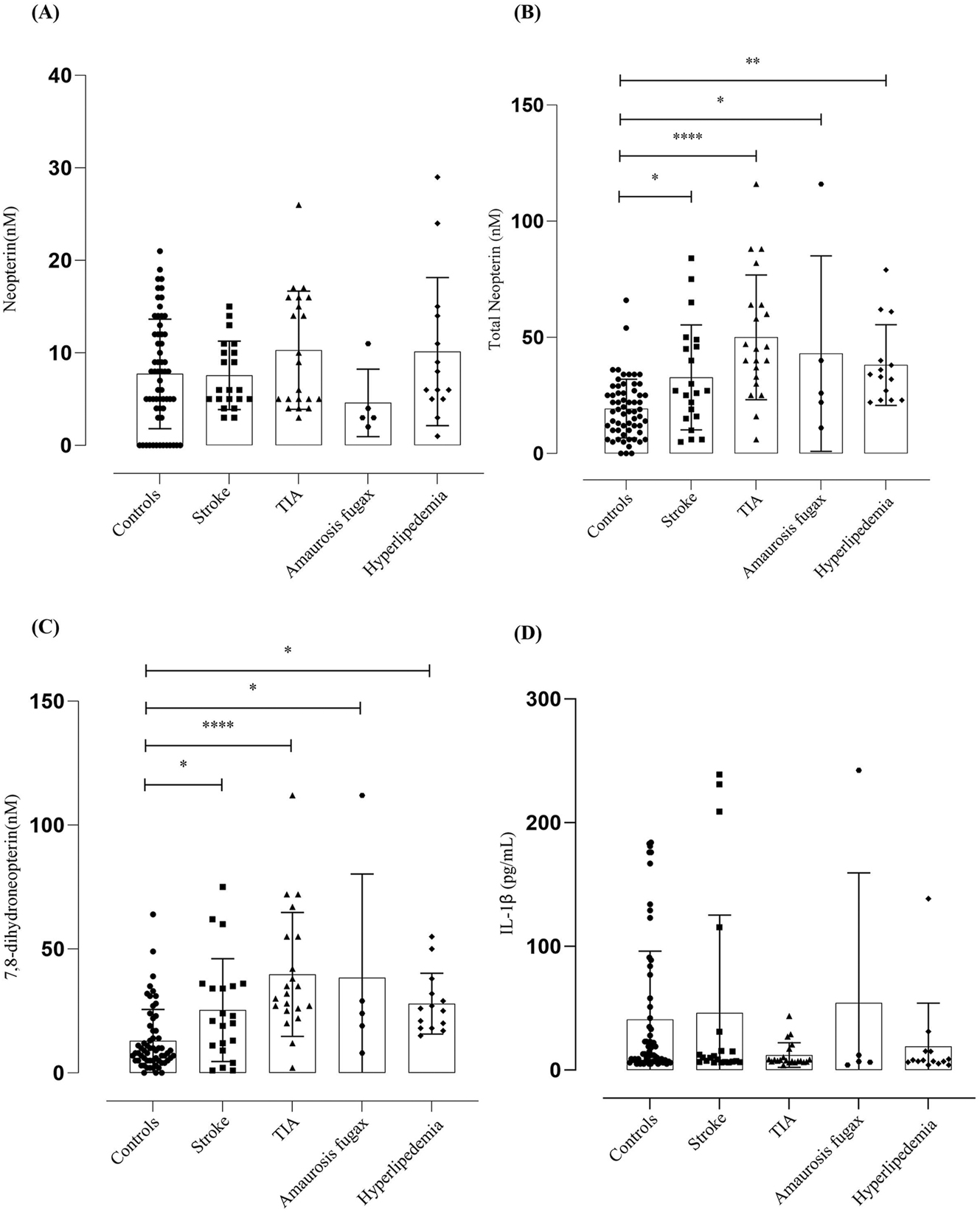

The patients who underwent endarterectomy were presented on admission with different forms of CVD like stroke, transitory ischemic attack (TIA), amaurosis fugax, and non-vascular conditions like hyper lipidemia. The neopterin and IL-1β levels did not show any significance among different conditions in comparison to the control group (Figure 3A and D), but the total neopterin levels were significantly higher in patients who suffered TIA p ≤ 0.001, amaurosis fugax and other non-vascular conditions p ≤ 0.0211 (Figure 3B). The 7,8-dihydroneopterin levels were significantly elevated among patients with TIA p ≤ 0.001, amaurosis fugax p ≤ 0.0059 (Figure 3C).

Neopterin, total neopterin, 7,8-dihydroneopterin and IL-1β measured in patients presented with different conditions. The results are displayed as mean SD. Control (N = 61), stroke (N = 21), TIA (N = 21), amaurosis fugax (N = 5), other conditions (N = 14). The significance levels are indicated as control versus other conditions on admission, the total neopterin were indicated as TIA p ≤ 0.001 = (****), amaurosis fugax and other non-vascular conditions p ≤ 0.0211 = (*) and the 7,8-dihydroneopterin levels indicated as TIA p ≤ 0.001 = (****), amaurosis fugax p ≤ 0.0059 = (*). Lines and boxes represent median and interquartile ranges.

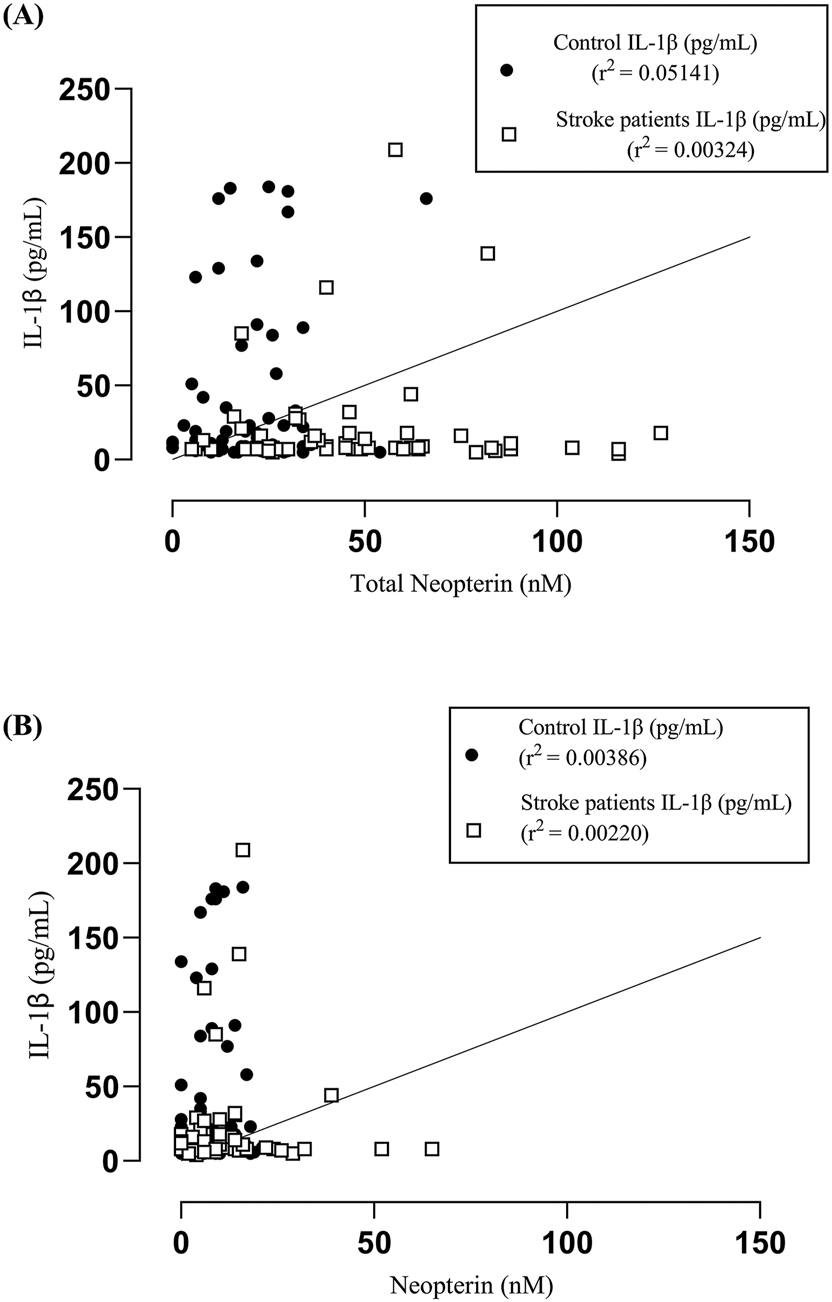

In analysis A, control subjects exhibited a slightly higher R 2 value (0.005141) compared to patients (0.00324), whereas in analysis B, control subjects had an R 2 of 0.00386, slightly surpassing patients with an R 2 of 0.00220.

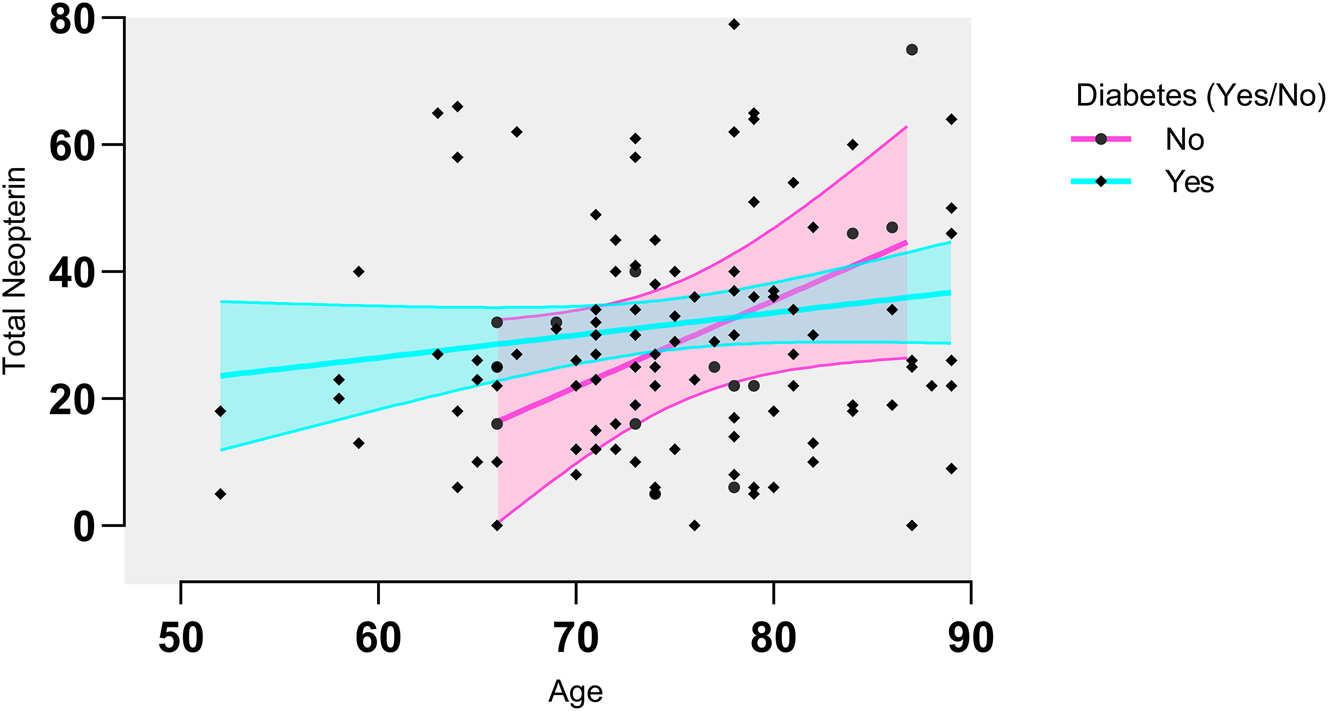

There was a significant difference between the controls and patients in the total neopterin levels and the difference between the diabetics and non-diabetics and their age significantly affected the total neopterin levels (Figure 4). 7,8-dihydroneopterin was significantly affected between control and patients showing the activation of macrophages in CVD (Figure 2C). It was also statistically affected by diabetes status, high blood pressure and age proving all these as risk factors (Tables 2–4).

Total neopterin analysis for the diabetics, the total neopterin appears to be increasing with age, while for the non-diabetics the opposite appears to be true. A correlation analysis was done and correlation was found between neopterin and diabetes. Total neopterin levels were significantly different between diabetics and non-diabetics (p = 0.0491) and the effect was significantly modified by age (p = 0.1343).

Statistical significance to neopterin in different conditions.

| Covariance name | p value (significance) |

|---|---|

| Smoking | 0.1902 (ns) |

| Diabetes | 0.1930 (ns) |

| High BP | 0.2964 (ns) |

| Control versus patients | 0.0016 (*) |

Statistical significance to total neopterin in different conditions.

| Covariance name | p value (significance) |

|---|---|

| Smoking | 0.3743 (ns) |

| Diabetes | 0.0491 (*) |

| High BP | 0.1270 (ns) |

| Control versus patients | 0.001 (****) |

Statistical significance to 7,8-dihydroneopterin in different conditions.

| Covariance name | p value (significance) |

|---|---|

| Smoking | 0.4469 (ns) |

| Diabetes | 0.0163 (**) |

| High BP | 0.0575 (**) |

| Control versus patients | 0.0011 (****) |

Additionally, the correlation between serum IL-1β levels and total neopterin did not yield significant findings for both control subjects (p = 0.0789) and patients (p = 0.6629). Similarly, no significant correlation was observed between serum IL-1β levels and neopterin for both groups, with control subjects reporting p = 0.6342 and patients p = 0.7194. These results suggest a lack of association between serum IL-1β levels and total neopterin or neopterin levels in both control subjects and patients (Figure 5).

Correlation analysis between serum IL-1β versus total neopterin and neopterin between carotid endarterectomy patients and age and gender matched controls. A Pearson correlation analysis gave an R 2 = 0.005141 for the control subjects and R 2 = 0.00324 for the patients (A). A Pearson correlation was performed with an R 2 = 0.00386 for the control subjects and R 2 = 0.00220 for the patients (B). There was no significant between serum IL-1β levels and total neopterin (control-p = 0.0789, patients-0.6629) and neopterin (control-p = 0.6342, patients-0.7194).

4 Discussion

This study investigated the efficacy of plasma total neopterin as a means of assessing monocyte/macrophage cell activation in patients with cardiovascular disease presenting with stroke. IL-1β measurements were incorporated to provide additional insights into the inflammatory status of the patients. The comparison between the age-matched controls and the stroke patients clearly demonstrates that measuring the total output of the activated macrophages, as total neopterin (neopterin plus 7,8-dihydroneopterin), provides a stronger indicator of immune cell activation than neopterin alone (Figure 1). In comparing the means values of age matched control versus stroke patients, the difference observed for neopterin was only 1.6 nM, whereas for total neopterin, it was much larger difference 11.4 nM. Based on the measurement of total neopterin, it was found that 22 patients had plasma levels higher than one standard deviation above the mean of the control subjects’ neopterin levels. When comparing the data, it was found that only three patients exhibited higher levels of neopterin above the first standard deviation from the mean, in contrast to the control group. Neopterin is known to be a stable end point in the oxidation cascade [27] while 7,8-dihydroneopterin thought to be more susceptible to further oxidation during circulation and sample storage. Despite this, we have managed to successfully measure significant and varying levels of 7,8-dihydroneopterin in the plasma. We have previously shown that plasma samples remain relatively stable during collection and storage with no significant loss of 7,8-dihydroneopterin to non-neopterin oxidation products, such as 7,8-dihydroxanthopterin and xanthopterin [28]. Within the blood and tissue, a conducive reducing environment exists, which restricts oxidative stress to specific areas where inflammation and varying levels of superoxide and neopterin generation are present, such as plaque. According to the findings of this study of stroke patients with comparison to age matched controls, neopterin measurements alone may underestimate the levels of inflammation occurring. This is likely due to the level of oxidative stress within the plaque being too low to oxidise significant amounts of the 7,8-dihydroneopterin released by the macrophage cells. The stroke patients and considerable elevated 7,8-dihydroneopterin levels overall compared to the controls (Figure 1C).

Our analysis revealed a noteworthy correlation between gender and neopterin and total neopterin levels. In the study, it was observed that female carotid endarterectomy patients had higher levels of total neopterin (mean of 54.5 nM) and 7,8-dihydroneopterin (mean of 46.55 nM) compared to male stroke patients (mean of 44.32 nM and 30.02 nM, respectively). Based on the observation, it can be inferred that females might exhibit a higher level of macrophage activation (Figure 2A). An evident discrepancy was observed in the overall neopterin levels between the control group and the patients, as illustrated in Figure 2B. This discrepancy between genders highlights the complex interplay between gender, macrophage activation, and oxidative stress in the context of CVD. Neopterin levels were found to be higher in male subjects compared to female subjects (Figure 2A), (mean neopterin level of 13.07 nM for males and 7.944 nM for females). Based on this observation, it can be inferred that male subjects might undergo a higher level of oxidative stress when faced with atherosclerotic lesions.

There is a statically significant difference between the control group and the stroke patients neopterin levels suggesting a general increase in oxidative stress as 7,8-dihydroneopterin is oxidised to neopterin (Tables 2–4) though this was small. It was surprising there was no significant correlation with smoking, diabetes, or high blood pressure statuses for the neopterin or total measurements but there was a correlation for 7,8-dihydroneopterin with diabetes and high blood pressure (Tables 3 and 4).

Diabetes is a significant risk factor for stroke, particularly ischemic stroke. Patients with stroke who have uncontrolled glucose levels experience increased mortality rates and have worse outcomes after the stroke [29]. Even with patients presenting with transient ischemic attacks with high blood sugar levels have a high incidence of severe stroke [30]. With our cohort of stroke patients, we can see that diabetic patients have an increased level of total neopterin which increases with age indicating increasing inflammation (Figure 4).

The stroke patients studied had a range of clinical presentation including cerebral obstructive stroke, TIA, amaurosis fugax, as well as additional cardiovascular related conditions of ischemic heart disease (IHD) and hyperlipidemia. The levels of neopterin did not show any significant differences across the different conditions when compared to the control group (Figure 3), but for all presentation of stroke there was a significant increase in total neopterin and 7,8-dihydroneopterin indicating the underlying inflammatory nature of CVD.

The lack of significant increase of IL-1β was unexpected as inflammasome activation is usually though as part of the inflammation mechanism. The effect of neopterin or 7,8-dihydroneopterin on inflammasome activation and IL-1β expression is unclear. Increased CD36 levels have been linked to increased inflammasome activation via increased uptake of cholesterol and the formation of cholesterol [31]. CD36 has been shown to be down regulated by 7,8-dihydroneopterin [31]. The clinical data in this study though showed no difference in IL-1β levels between patients and controls and therefore no link between 7,8-dihydroneopterin levels and inflammasome activation. We also found no correlation between neopterin or total neopterin and IL-1β with either the control or stroke patients (Figure 5).

IL-1β levels in ischemic stroke and aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) are generally lower in serum compared to levels in cerebral spinal fluid (CSF), indicating an intrathecal source likely influenced by the severity of ischemic injury [32], 33]. Studies have consistently found elevated IL-1β levels in the CSF of patients with acute ischemic stroke or SAH, indicating a localized CNS inflammatory response [32]. A lack of significant variation between serum IL-1β levels between ischemic stroke patients and controls has been previous reported [34] which support our own findings. It is possible the level of inflammasome activation within the plaque is insufficient to raise the IL-1β levels significant in the plasma and is part of a localized tissue response.

It is disappointing that despite the extensive research demonstrating neopterin utility as a marker of worsening cardiovascular disease (CVD) in patients, this analytical approach has not been adopted in clinical management. Part of this problem may relate to the convenience of high sensitive C-reactive protein (hsCRP) analysis which though indicative may not be as strongly predictive. Measurement of plasma neopterin alone is only indicative as the data here also has shown. Total neopterin, as shown in this study gives a stronger signal of inflammation in stroke patients. The key problem though is that inflammation occurs within a patient for a variety of reasons, not just CVD so the clinical context of the patient needs to be considered. In measuring IL-1β we had intended to increase the utility of the patient neopterin and total neopterin analysis, but the IL-1β levels were not significant between the groups. Though total neopterin gives a clearer signal of elevated inflammation, additional biochemical markers or improved vascular imaging are required to indicate CVD in a patient. Total neopterin still makes a valuable marker of inflammation in stroke patients and potential other presentation of CVD. As neopterin levels have been shown to indicate increasing severity CVD, we expect that the use of total neopterin analysis would provide a more reliable marker of patients that require more elaborate treatment and monitoring.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the technical support staff in the School of Biological Sciences and the Clinical Staff of the Department of Vascular surgery. This paper is dedicated to the memory of Dr Siddarth Raajasekar’s grandfather Krishnamoorthy Srirangan for his support and encouragement, who passed away during this manuscript preparation.

-

Financial support: This work was partly funded through a project grant from the Neurological Foundation of New Zealand and Student Research Support from the School of Biological Sciences, University of Canterbury.

-

Author contributions: Siddarth Raajasekar contributed to experimental design, data collection, results interpretation, figure preparation, manuscript preparation and editing. Justin Roake and Ruth Benson coordinated sample collection from stroke patients and editing of the manuscript. Vicky Cameron and Anna Pillbrow collected the age match control samples and contributed to the manuscript editing. Elena Moltchanova directed and carried out some of the statistical analysis of data. Steven Gieseg contributed to experimental direction, design, data interpretation, manuscript preparation and editing. He was principal investigator and supervisor of the research and was responsible for the securing the funding.

-

Conflicts of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

1. Pacileo, M, Cirillo, P, De Rosa, S, Ucci, G, Petrillo, G, Musto D’Amore, S, et al.. The role of neopterin in cardiovascular disease. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis 2007;68:68–73. https://doi.org/10.4081/monaldi.2007.454.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Baxter-Parker, G, Prebble, HM, Cross, S, Steyn, N, Shchepetkina, A, Hock, BD, et al.. Neopterin formation through radical scavenging of superoxide by the macrophage synthesised antioxidant 7, 8-dihydroneopterin. Free Radic Biol Med 2020;152:142–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2020.03.002.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Janmale, T, Genet, R, Crone, E, Flavall, E, Firth, C, Pirker, J, et al.. Neopterin and 7,8-dihydroneopterin are generated within atherosclerotic plaques. Pteridines 2015;26:93–103. https://doi.org/10.1515/pterid-2015-0004.Search in Google Scholar

4. Gieseg, SP, Esterbauer, H. Low density lipoprotein is saturable by pro-oxidant copper. FEBS Lett 1994;343:188–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/0014-5793(94)80553-9.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Gieseg, SP, Amit, Z, Yang, YT, Shchepetkina, A, Katouah, H. Oxidant production, oxLDL uptake, and CD36 levels in human monocyte-derived macrophages are downregulated by the macrophage-generated antioxidant 7,8-dihydroneopterin. Antioxidants Redox Signal 2010;13:1525–34. https://doi.org/10.1089/ars.2009.3065.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Ghodsian, N, Yeandle, A, Gieseg, SP. Foam cell formation but not oxLDL cytotoxicity is inhibited by CD36 Down regulation by the macrophage antioxidant 7,8-dihydroneopterin. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2021;133:105918. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocel.2021.105918.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Prebble, H, Cross, S, Marks, E, Healy, J, Searle, E, Aamir, R, et al.. Induced macrophage activation in live excised atherosclerotic plaque. Immunobiology 2018;223:526–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imbio.2018.03.002.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Libby, P. Inflammation and cardiovascular disease mechanisms. Am J Clin Nutr 2006;83:456S–60S. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/83.2.456s.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Meng, L-l, Cao, L. Serum neopterin levels and their role in the prognosis of patients with ischemic stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Neurosci 2021;92:55–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2021.07.033.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Alme, KN, Ulvik, A, Askim, T, Assmus, J, Mollnes, TE, Naik, M, et al.. Neopterin and kynurenic acid as predictors of stroke recurrence and mortality: a multicentre prospective cohort study on biomarkers of inflammation measured three months after ischemic stroke. BMC Neurol 2021;21:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-021-02498-w.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

11. Ulvi, H, Emre, H, Demir, R, Aygul, R, Varoğlu, A, Kara, F. Neopterin levels in patients with cerebrovascular disease. Eurasian J Med 2008;40:79–82.Search in Google Scholar

12. Xie, J, Qiu, X, Ji, C, Liu, C, Wu, Y. Elevated serum neopterin and homocysteine increased the risk of ischemic stroke in patients with transient ischemic attack. Pteridines 2019;30:59–64. https://doi.org/10.1515/pteridines-2019-0009.Search in Google Scholar

13. Anwaar, I, Gottsäter, A, Lindgärde, F, Mattiasson, I. Increasing plasma neopterin and persistent plasma endothelin during follow-up after acute cerebral ischemia. Angiology 1999;50:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/000331979905000101.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Braddock, M, Quinn, A. Targeting IL-1 in inflammatory disease: new opportunities for therapeutic intervention. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2004;3:330–40. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd1342.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Dinarello, CA. Therapeutic strategies to reduce IL-1 activity in treating local and systemic inflammation. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2004;4:378–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coph.2004.03.010.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Dinarello, CA, Biologic basis for interleukin-1 in disease. 1996.87, 2095, 147, https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.v87.6.2095.bloodjournal8762095.Search in Google Scholar

17. Haybar, H, Shokuhian, M, Bagheri, M, Davari, N, Saki, N. Involvement of circulating inflammatory factors in prognosis and risk of cardiovascular disease. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2019;132:110–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yjmcc.2019.05.010.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Lopez-Castejon, G, Brough, D. Understanding the mechanism of IL-1β secretion. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2011;22:189–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cytogfr.2011.10.001.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

19. Avolio, E, Pasqua, T, Di Vito, A, Fazzari, G, Cardillo, G, Alò, R, et al.. Role of brain neuroinflammatory factors on hypertension in the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Neuroscience 2018;375:158–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2018.01.067.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Qi, J, Zhao, XF, Yu, XJ, Yi, QY, Shi, XL, Tan, H, et al.. Targeting interleukin-1 beta to suppress sympathoexcitation in hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus in Dahl salt-sensitive hypertensive rats. Cardiovasc Toxicol 2016;16:298–306. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12012-015-9338-7.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Everett, B, Everett, BM, Thuren, T, MacFadyen, JG, Chang, WH, Ballantyne, C, et al.. Antiinflammatory therapy with canakinumab for atherosclerotic disease. N Engl J Med 2017;377:1119–31. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1707914.Search in Google Scholar

22. Moore, KJ. Targeting inflammation in CVD: advances and challenges. Nat Rev Cardiol 2019;16:74–5. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41569-018-0144-3.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

23. Ridker, PM, Everett, BM, Pradhan, A, MacFadyen, JG, Solomon, DH, Zaharris, E, et al.. Low-dose methotrexate for the prevention of atherosclerotic events. N Engl J Med 2019;380:752–62. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1809798.Search in Google Scholar

24. Kotla, S, Singh, NK, Rao, GN. ROS via BTK-p300-STAT1-PPARγ signalling activation mediates cholesterol crystals-induced CD36 expression and foam cell formation. Redox Biol 2017;11:350–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2016.12.005.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

25. Baxter-Parker, G, Roffe, L, Moltchanova, E, Jefferies, J, Raajasekar, S, Hooper, G, et al.. Urinary neopterin and total neopterin measurements allow monitoring of oxidative stress and inflammation levels of knee and hip arthroplasty patients. PLoS One 2021;16:e0256072. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0256072.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

26. Baxter-Parker, G, Chu, A, Petocz, P, Samman, S, Gieseg, SP. Simultaneous analysis of neopterin, kynurenine and tryptophan by amine-HPLC shows minor oxidative stress from short-term exhaustion exercise. Pteridines 2019;30:21–32. https://doi.org/10.1515/pteridines-2019-0003.Search in Google Scholar

27. Lindsay, A, Baxter-Parker, G, Gieseg, SP. Pterins as diagnostic markers of mechanical and impact-induced trauma: a systematic review. J Clin Med 2019;8:1383. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8091383.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

28. Baxter-Parker, G, Roffe, L, Cross, S, Frampton, C, Hooper, GJ, Gieseg, SP. Knee replacement surgery significantly elevates the urinary inflammatory biomarkers neopterin and 7,8-dihydroneopterin. Clin Biochem 2019;63:39–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2018.11.002.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

29. Mosenzon, O, Cheng, AY, Rabinstein, AA, Sacco, S. Diabetes and stroke: what are the connections? J Stroke 2023;25:26–38. https://doi.org/10.5853/jos.2022.02306.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

30. Chen, R, Ovbiagele, B, Feng, W. Diabetes and stroke: epidemiology, pathophysiology, pharmaceuticals and outcomes. Am J Med Sci 2016;351:380–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjms.2016.01.011.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

31. Ghodsian, N, Yeandle, A, Hock, BD, Gieseg, SP. CD36 down regulation by the macrophage antioxidant 7,8-dihydroneopterin through modulation of PPAR-γ activity. Free Radic Res 2022;56:1–27 (just-accepted). https://doi.org/10.1080/10715762.2022.2114904.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

32. Jin, J, Duan, J, Du, L, Xing, W, Peng, X, Zhao, Q. Inflammation and immune cell abnormalities in intracranial aneurysm subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH): relevant signaling pathways and therapeutic strategies. Front Immunol 2022;13:1027756. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.1027756.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

33. Sobowale, OA, Parry-Jones, AR, Smith, CJ, Tyrrell, PJ, Rothwell, NJ, Allan, SM. Interleukin-1 in stroke: from bench to bedside. Stroke 2016;47:2160–7. https://doi.org/10.1161/strokeaha.115.010001.Search in Google Scholar

34. Clausen, BH, Wirenfeldt, M, Høgedal, SS, Frich, LH, Nielsen, HH, Schrøder, HD, et al.. Characterization of the TNF and IL-1 systems in human brain and blood after ischemic stroke. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2020;8:1–17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40478-020-00957-y.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Neopterin interactions with magic atom number coinage metal nanoclusters: A theoretical study

- High expression of folate metabolic pathway gene MTHFD2 is related to the poor prognosis of patients and may apply as a potential new target for therapy of NSCLC

- Changes and imbalance of Th1 and Th2 immune response in pediatric patients with seasonal allergic conjunctivitis

- Extracellular spermidine attenuates tryptophan breakdown in mitogen-stimulated peripheral human mononuclear blood cells

- Plasma total neopterin and neopterin levels are significantly elevated in stroke patients before carotid endarterectomy surgery

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Neopterin interactions with magic atom number coinage metal nanoclusters: A theoretical study

- High expression of folate metabolic pathway gene MTHFD2 is related to the poor prognosis of patients and may apply as a potential new target for therapy of NSCLC

- Changes and imbalance of Th1 and Th2 immune response in pediatric patients with seasonal allergic conjunctivitis

- Extracellular spermidine attenuates tryptophan breakdown in mitogen-stimulated peripheral human mononuclear blood cells

- Plasma total neopterin and neopterin levels are significantly elevated in stroke patients before carotid endarterectomy surgery