Abstract

Cultural heritage encompasses the accumulation of both tangible and intangible assets left behind by a nation in the past and it is increasingly drawing the attention of researchers from various disciplines. The realm of cultural heritage tourism has witnessed transformative opportunities in travel modes due to disruptive innovations in interaction design. However, there is a paucity of comprehensive reviews on relevant studies. Therefore, there is a need for research that presents a thorough exploration of interaction design in cultural heritage tourism and outlines future research prospects. To address this gap, the current study utilizes CiteSpace software to conduct visual and quantitative analyses on 168 papers retrieved from the SCIE, SSCI, and AHCI indices on the Web of Science platform from the first publication in 2001 to the year 2023. The outcomes of this research offer a systematic summary, comprehensive categorization, and innovative perspectives and directions for future studies on the application of interaction design in cultural heritage tourism.

1 Introduction

Cultural heritage epitomizes a collective repository of extraordinary universal significance – a priceless legacy transmitted by our predecessors to subsequent generations. It stands as an irreplaceable and revered asset. Additionally, the global recognition of the tourism and cultural heritage industries as promising drivers of economic development is evident (De Beukelaer 2014). The United Nations World Tourism Organization (UN-WTO) has underscored the symbiotic relationship and interdependence between tourism and culture (Canton 2021). Concurrently, heritage tourism is recognized as the principal and swiftly expanding niche market within the tourism sector (Środa-Murawska et al. 2021), emphasizing the pivotal role of both tourism and heritage in catalyzing sustainable regional development (Barnes 2022).

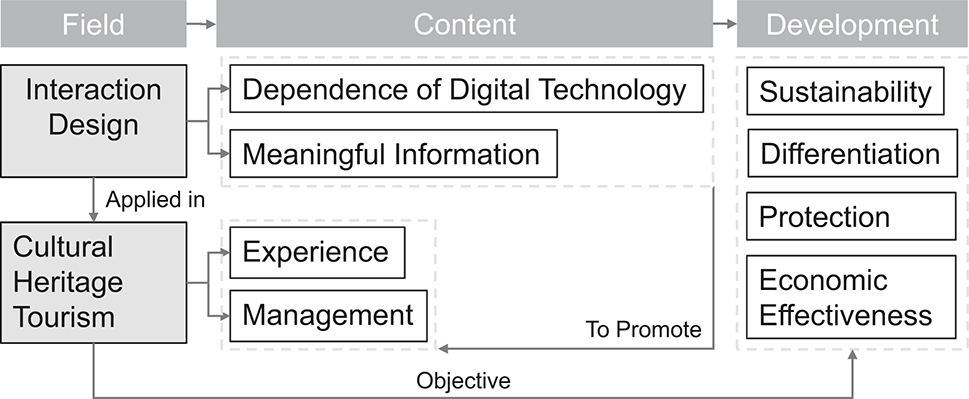

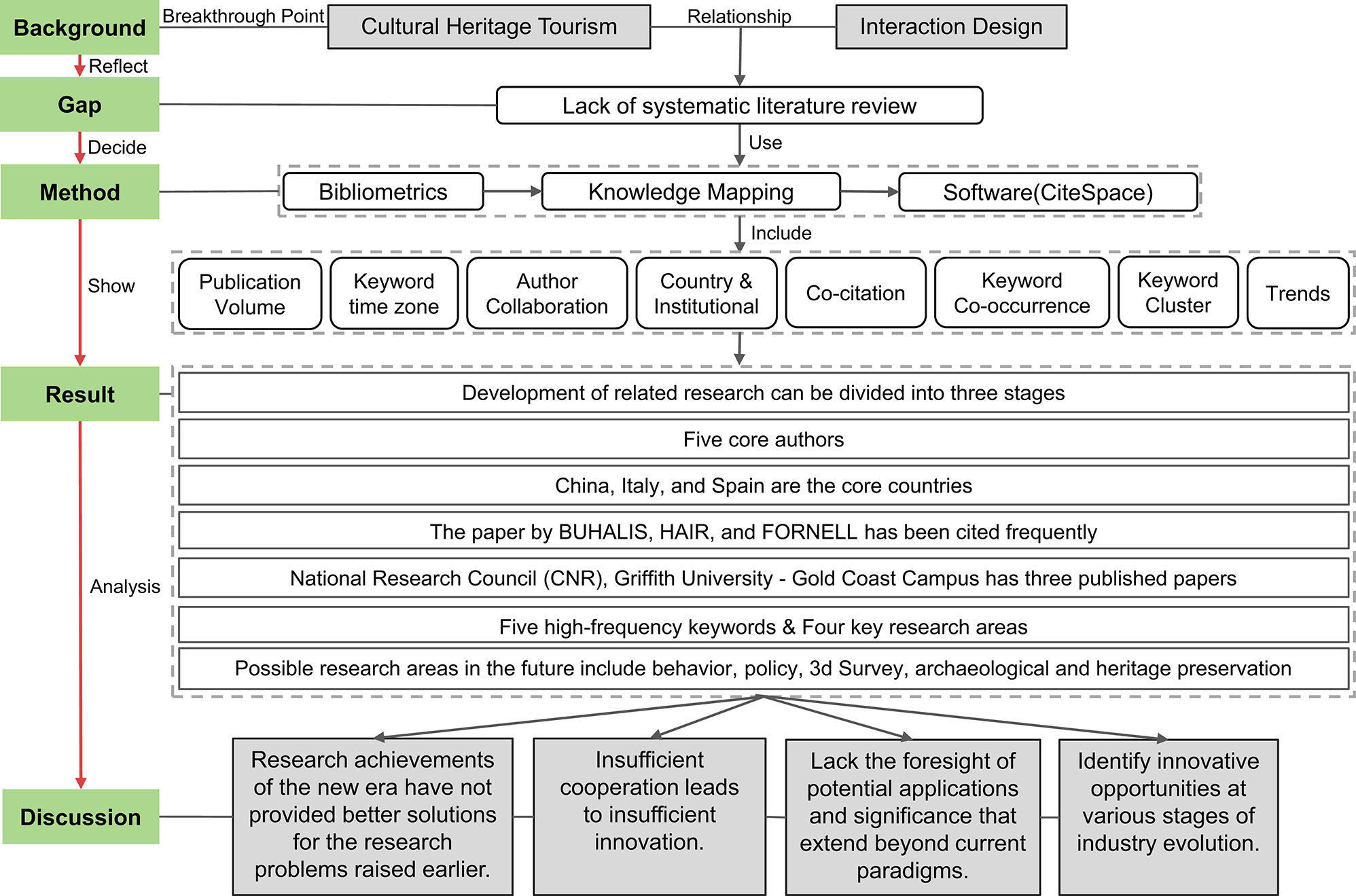

Nevertheless, recent years have witnessed the swift growth of the cultural tourism industry, accompanied by emerging challenges. An instance of this is the non-renewable nature of cultural heritage, which has historically been a focal point for achieving sustainable development in cultural heritage tourism (Zhang et al. 2023). The notion that attaining sustainable development goals is a crucial undertaking in tourism studies further underscores this concern (Zhu and Chiou 2022). On the other hand, amidst the ongoing development and evolution of information technology and the design service industry in the contemporary world, coupled with the continuous expansion of knowledge systems and technology, the significance of big data has assumed growing importance (Lee and Kang 2015). This contextual backdrop has resulted in an increasing reliance on technological tools for accessing digital cultural content, encompassing music, images, and various multimedia expressions (Bolin 2012). Simultaneously, researchers have observed that this shift presents novel perspectives for advancing cultural heritage tourism and its relationship to sustainable development and promotion. The study indicates that while data mining technology enables people to extract targeted information from the vast and intricate data landscape, challenges persist in the process of collecting big data. Extracting meaningful value from the data is not a direct process and, often, the data contains obscure information concealed at deeper levels (Oliverio 2018). From the researchers’ perspective, there is a demand for a systematic knowledge framework that combines people’s robust visual abilities with art and design (Yu 2021). This framework can intuitively portray the significance of data and information within cultural heritage tourism during the information interaction process (Yang and Liu 2022). Consequently, the necessity to enhance the convenience, intuitiveness, and efficiency of the information acquisition process through interaction has prompted the development of an interdisciplinary fusion with interaction design. This fusion has become a focal point for cultural heritage tourism researchers, particularly concerning the experience, management, and development of cultural heritage tourism (Guo et al. 2022) (refer to Figure 1).

Research knowledge framework of interaction design in cultural heritage tourism.

The term “interaction design” is commonly defined as the facilitation of interactions with artifacts or between individuals through the mediation of artifacts. The distinctiveness of the interaction design discipline lies in its emphasis on “behavior, function, and information” (Skublewska-Paszkowska et al. 2022). Also referred to as interactive design, interaction design entails the definition and design of the behavior of artificial systems. It encompasses the design of artificial products, the environment, and the behavior of the system, as well as the configuration of such acts to communicate design elements and definitions. Certain advantageous features in interaction design significantly contribute to enhancing sustainability, promoting diversity, addressing protection needs, and maximizing economic benefits within cultural heritage tourism. By leveraging these design elements, stakeholders can create more inclusive and engaging experiences that not only preserve cultural assets but also foster community involvement and sustainable practices, ultimately enriching the overall impact of tourism on cultural heritage (refer to Figure 1).

This study aims to address this gap by conducting an examination of the existing literature on the application of interaction design in cultural heritage tourism. Additionally, it is essential to critically analyze the extent of progress made in the development process of this field, as well as the challenges encountered along the way. This study lays the groundwork for both literature and theoretical research aimed at promoting the sustainable development of cultural heritage and cultural heritage tourism. By addressing previously overlooked issues and systematically organizing the existing knowledge structure, the research not only identifies gaps in current practices but also provides actionable insights for future advancements, ensuring a more sustainable and impactful approach for cultural heritage tourism. Utilizing bibliometric studies, this not only serves as a reference for related research but also offers practical guidance for application.

2 Current State and Motivation of Research

Within cultural heritage tourism, interaction design serves to enhance the appeal of destinations through the reinforcement of unique historical architecture, religious beliefs, traditional cuisine, and other cultural features, enticing tourists to engage in sightseeing and immersive experiences (Zhang et al. 2023). This trend underscores the strong interdisciplinary nature of research in this domain. A crucial initial step in advancing scientific interest involves analyzing the current state of both science and practice in the application of interaction design within cultural heritage tourism (Liu and Pan 2023).

State of the art was aimed to identify:

The current research status of interactive design in cultural heritage tourism.

The themes and motifs presented in the research on the application of interaction design in cultural heritage tourism.

Differences in centrality among relevant researchers, institutions, and countries.

The knowledge framework and types of related research are beneficial to different fields and industries.

3 Research Questions

Due to the lack of similar research in the field of interaction design in intangible cultural heritage tourism, based on the research motivation proposed in the research motivation section, the following research questions can be proposed:

What extent has the application of interactive design developed in cultural heritage tourism?

Which perspectives on research has been groundbreaking and landmark?

What are the most important topics and themes presented in the studies on the use of interaction design in cultural heritage tourism?

What is the knowledge of the field and how has the forefront of research evolved?

4 Materials and Methods

4.1 Selection of Data Sources

In selecting data sources, research is conducted on data retrieval based on SCIE, SSCI, and AHCI categories in the web of science platform. There are three main reasons for choosing these three data sources:

Owing to the multidisciplinary nature inherent in the scope of this research, encompassing the realms of natural sciences, humanities, social sciences, and the arts, a comprehensive approach is undertaken to ensure a diverse array of data sources.

Despite the comparatively novel nature of the subjects under investigation in this study and the limited number of related international studies, meticulous attention is directed towards maintaining consistency in keyword occurrence frequencies and rank order numbers within any given text (Funkhouser 1996).

To ensure the integrity and reliability of the data sources utilized, all citation databases in the realms of natural science, social sciences and humanities, notably the Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI), Arts and Humanities Citation Index (AHCI), and the Science Citation Index Expanded (SCIE), are systematically employed (Chen 2006).

In Wos search, first enter the subject words digital interaction, interactive media, interaction design, and digital interaction design, and connect them with “or.” Further search. Secondly, re-enter the search page, enter the themes heritage tourism, cultural tourism, cultural heritage tourism, and cultural heritage tourism, and connect them with “or.” Further search. Finally, select the first search content and the second search content from the search records of the advanced search, and connect them with “and.” Then select the publication type as article and the review article. The results show that the first article was published in 2001, and a total of 168 articles were selected as data analysis sources.

4.2 Selection and use of Research Instruments

This study utilized the CiteSpace 6.2.R6 visual analysis software, developed by Professor Chen Chaomei’s team at Drexel University. Grounded in scientometrics and knowledge visualization, this software possesses the capacity to objectively analyze extensive volumes of scientific literature data (Chen 2006). Researchers can employ CiteSpace for co-citation analysis, co-occurrence analysis, cluster analysis, and burst analysis of keywords within the realm of scientific investigation (Li and Hua 2018).

4.3 Content and Modalities of the Study

Count analysis is centered on the quantification of publications in the scholarly literature. It involves a comparative assessment of the number of articles published for each topical term, scrutinizing the publication frequency across various components addressed in this study. The examination extends to analyzing the congruence between each thematic term and the substantive content of the current investigation (refer to Table 1).

The data collection and analysis protocol.

| Research protocol | Retrieve results and contents |

|---|---|

| Research database | SCIE, SSCI, AHCI |

| Language | English, Croatian, Turkish |

| Publication type | Article, Review Article |

| Year span | January 1, 2001–December 31, 2023 |

| Retrieval criterion | Topic = “digital interaction (Topic) or interactive media (Topic) or interaction design (Topic) or digital interaction design (Topic)” and “heritage tourism (Topic) or cultural tourism (Topic) or cultural heritage tourism (Topic) or cultural heritage tour (Topic)” |

| Exclusion criteria | Early Access, Proceeding Paper |

| Inclusion criteria | Academic papers published on cultural heritage tourism (including online publications and review articles) |

| Number of samples | 168 |

| Software | CiteSpace 6.2.R6 |

| Analysis paths | Count analysis, collaboration analysis, co-citation analysis, co-occurrence analysis, cluster analysis |

Collaborative analysis in this context is dedicated to understanding how researchers collaborate to generate novel scientific knowledge (Aria and Cuccurullo 2017).

Co-occurrence analysis, a quantitative method, utilizes the frequency of term appearance across multiple articles within a database to construct the conceptual knowledge structure of a research domain, emphasizing its pivotal areas (Russo and Van der Borg 2002).

Co-citation analysis, another quantitative technique, involves evaluating interconnection relationships within a research field by considering the number of publications in which references, authors, or sources are co-cited together. Cluster analysis relies on the clustering method, which involves grouping a set of objects based on their similarities. Elements within a cluster exhibit a high degree of similarity, while differences between distinct clusters are pronounced (Tress and Tress 2001).

5 Discussion and Results

5.1 Analysis of Publication Volume

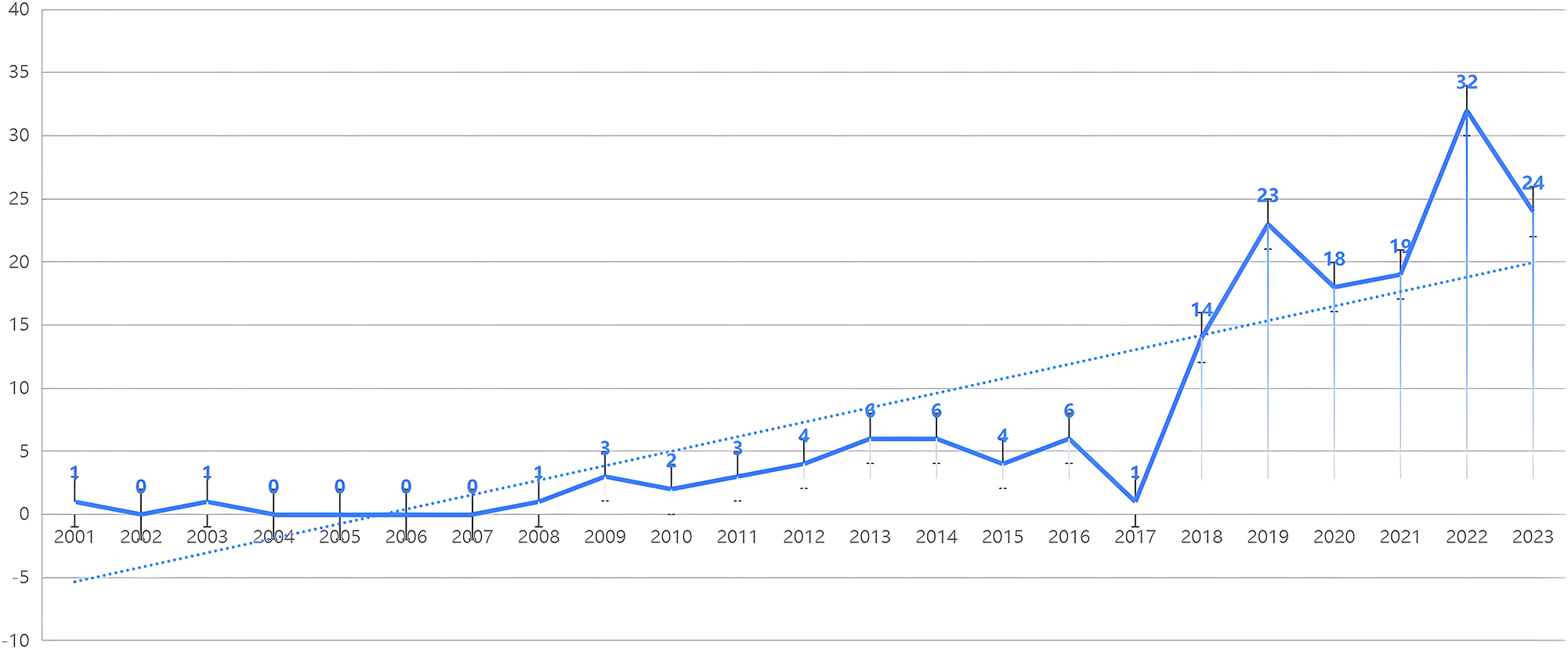

Analyzing the search outcomes in the Web of Science (WOS) (refer to Figure 2), we can obtain an initial comprehension of the trajectory of interactive design within cultural heritage tourism application research, indicative of a discernible upward trajectory in knowledge expansion.

Annual distribution of interaction design in cultural heritage tourism research publications from 2001 to 2023.

Analyzing the search outcomes in the Web of Science (WOS) (refer to Figure 2) reveals an initial understanding of the trajectory of interactive design within cultural heritage tourism research, showcasing a discernible upward trend in knowledge expansion. This developmental pattern can be categorized into three distinct stages. The initial stage, from 2001 to 2008, marked a nascent phase with a sparse publication, featuring only two articles over seven years. The inaugural article in 2001 was a pioneering contribution to the field, primarily focusing on the interactive model between humans and landscapes to elucidate the transitional landscape concept, thereby delving into the dynamics of human-landscape interaction. The subsequent phase, from 2009 to 2015, indicated gradual advancement, characterized by a steady yet modest annual increase in publications. Despite 2017 seeing only one publication, the period from 2016 to 2023 emerged as a phase of rapid expansion, culminating in a peak of 32 articles in 2022. Consequently, this surge in activity indicates that the field has attracted heightened attention from academic researchers during this intensified research period.

5.2 Keyword Time Zone Analysis

5.2.1 Budding Stage (2001–2008)

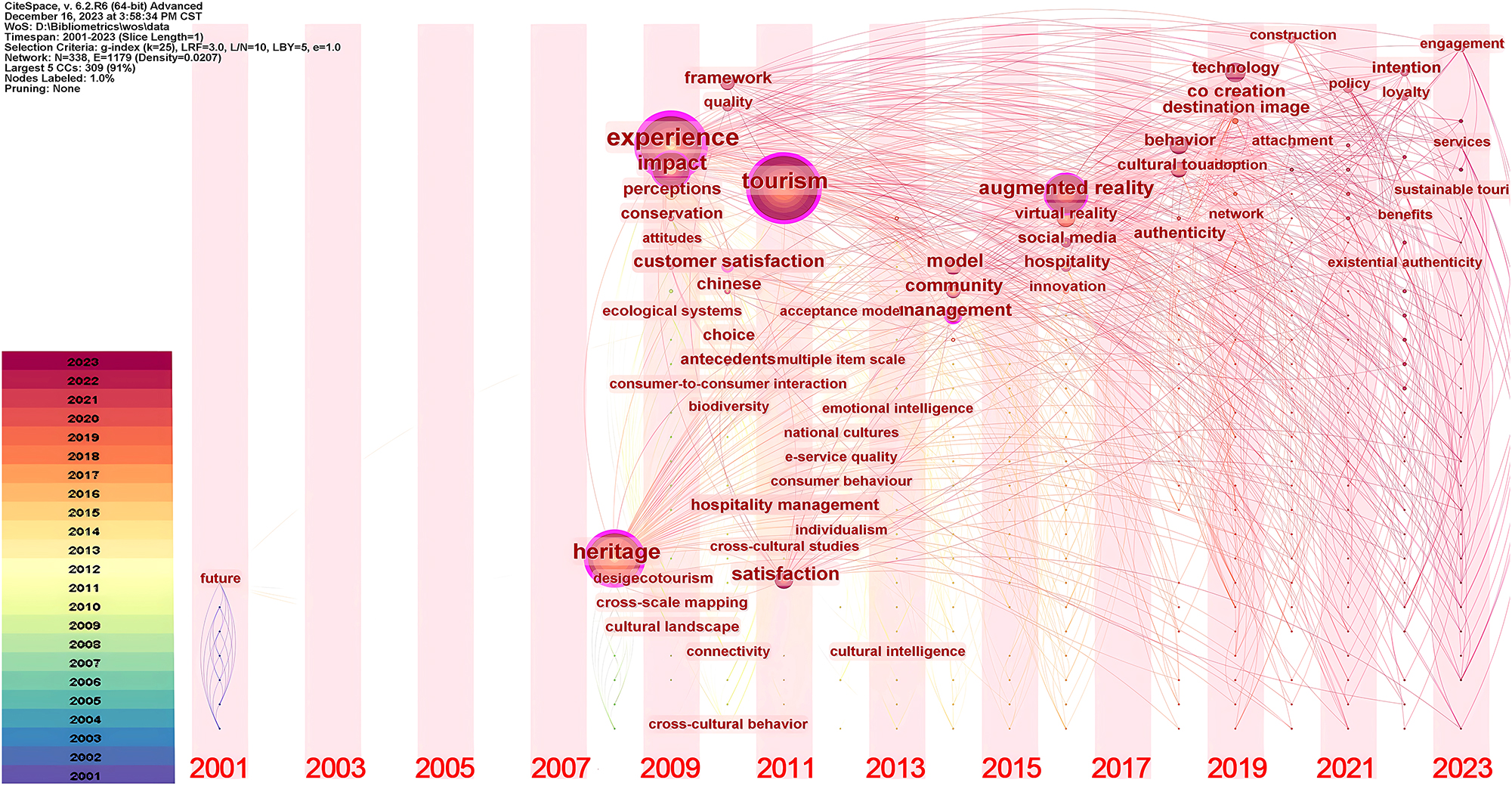

During the initial phase of the examined timeframe, noteworthy keywords encompassed terms like “future” and “landscape.” In 2008, a shift occurred with the introduction of keywords such as “interactive drama,” “design,” “guide,” “virtual characters,” and “adaptive applications.” Towards the conclusion of this phase, some researchers embarked on preliminary initiatives in interactive heritage tourism, substantiating the feasibility of their research and forecasting potential future advancements. This phenomenon is attributed to several factors. Firstly, the notion of cultural heritage gained prominence in the early twenty-first century, with a pivotal moment occurring on October 17, 2003, when the third-second General Conference of UNESCO ratified the Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage. Secondly, the progress of interaction design hinges on the advancements in digital technology, interactive devices, and network technology. These elements are presently undergoing research and development, with certain technological barriers yet to be overcome. The existing progress in related research is deemed insufficient to robustly underpin and propel the evolution of cultural heritage tourism. Lastly, as pertinent technologies advanced, researchers gradually delved into exploring novel opportunities and prospects that interactive design could offer for the advancement of cultural heritage tourism. In 2008, relevant research endeavors emerged, seeking to develop applications for cultural tourism guidance grounded in mobile devices. Character presentations were designed to incorporate a dramatic disposition, concurrently enhancing user credibility for the dissemination of historical and cultural content (Damiano et al. 2008) (refer to Figure 3).

Time zone of keyword of related research.

5.2.2 Stable Development Period (2009–2015)

During the initial phase of this stage, pivotal keywords include the impact elucidated by pertinent research, experiences, satisfaction, and perceptions pertaining to tourists’ emotions, with the introduction of themes such as conservation and Chinese heritage. In the subsequent middle and late stages, the focal points shift towards management, destination, and related aspects. These discernible shifts in emphasis underscore researchers’ heightened attention to the genuine sentiments of individuals within the interactive process, acknowledging the more positive research value inherent in this field concerning heritage conservation and Chinese heritage. Simultaneously, the integration of interaction design into specific domains of cultural heritage tourism, along with its practical applications, is a response to the burgeoning significance of sustainability in cultural tourism. Achieving sustainable development goals has become an essential objective within the field of tourism studies (Zhu and Chiou 2022). Researchers, in their pursuit to anticipate the benefits of interaction design for cultural heritage tourism, delve into specific themes such as shifts in tourists’ perceptions, alterations in tourism management, the efficacy of cultural heritage preservation, and the trajectory of China’s cultural heritage (refer to Figure 3).

5.2.3 Explosive Growth Period (2016–2023)

This phase witnesses a proliferation of keywords, spurred primarily by the intersection of interaction design with advancements in computer graphics technology. This collaboration fosters a direct interdisciplinary research relationship within cultural heritage tourism, giving rise to influential terms such as virtual reality and augmented reality. These high-value central keywords emerge prominently in the realm of cultural heritage tourism, shaping the landscape of interaction design and tourism experiences. Consequently, researchers redirect their focus towards keywords like authenticity and destination image, considering the transformative impact of new technologies on the interaction design and tourism experience. Simultaneously, a noteworthy phenomenon in this phase is the diversification of research fields. A multitude of keywords with low centrality values, previously absent in earlier phases, now come to the forefront. Examples include education, gamification, sustainable tourism, cultural consumption, casino city, food tourism, built vernacular heritage, autoethnography, and social media. This diversification is underscored by the presence of 162 keywords with a centrality value of 0, constituting 47.92 % of all keywords developed in the field thus far. This stage signifies a knowledge explosion, driven by the maturity of cultural heritage tourism research and its inherent diversity and interdisciplinarity. Furthermore, in the era of digital intelligence, the evolution of digital heritage services emerges as an inevitable trend, promising substantial environmental and economic benefits (refer to Figure 3).

5.3 Author Collaboration Analysis

Conducting an examination of core authors holds significant importance within the realm of quantitative analysis research. These extensively cited authors often possess affiliations with developers or research centers specializing in classification systems. Engaging with these well-established professionals not only facilitates access to valuable expertise but also opens doors to potential funding opportunities (Lourenço et al. 2010).

When examining the number of core authors, the study employs Price’s law to ascertain the extent to which publication volume identifies core authors within the pertinent field. The calculation formula for this purpose is as follows:

Among these, N1 denotes the minimum number of papers required to attain the status of a core researcher within the field while N max signifies the maximum number of papers published by any author in this research domain (Price, Monaghan). In accordance with this theoretical framework, six individuals stand out for having published the highest number of articles, each contributing two papers, hence, N max is established as 2. Calculations based on this model yield N1 = 1.059, indicating that the publication count for core researchers in the pivotal field should exceed one. The cumulative articles authored by core researchers in this study amount to 12, constituting 7.14 % of the overall publication count. As per the theoretical framework, achieving 50 % of articles published by core authors suggests the formation of a core author group in the relevant field.

Moreover, CiteSpace 6.2.R6 employs an analysis framework wherein each author is represented as a node, with limited connections observed between these nodes. In software, the concept of centrality mainly refers to a method used to determine the importance of various elements (such as authors, publications, themes, etc.) in academic literature. CiteSpace uses centrality analysis to measure the central nodes (such as academic leaders and hot topics) in chemical technology networks. The higher the central value, the more academic activities are carried out around these authors, countries, institutions, etc. as the core. As depicted in Table 2, the centrality values are uniformly registered as 0, suggesting a lack of robust cooperative relationships and shared responsibilities among authors (Song et al. 2021). However, amidst this prevailing pattern, a segment of researchers has embraced collaborative publishing. Remarkable examples include the joint endeavors of Giovanni Cucinotta, Dario Giuffrida, and Vittoria Irene Calabro in publications such as “Digitization of Two Urban Archaeological Areas in Reggio Calabria (Italy): Roman Thermal and Greek Predictions” (Giuffrida et al. 2022), and “A Multi-Analytical Study for the Enhancement and Accessibility of Archaeological Heritage: The Churches of San Nicola and San Basilio in Motta Sant’Agata (RC, Italy)” (Giuffrida et al. 2021) (refer to Table 2).

Top six authors of papers in related research.

| Serial number | Count | Centrality | Authors | Proportion (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 0 | Cucinotta, Giovanni | 1.19 |

| 2 | 2 | 0 | Gannon, Martin Joseph | 1.19 |

| 3 | 2 | 0 | Chen, Chun-Ching | 1.19 |

| 4 | 2 | 0 | Rauschnabel, Philipp A | 1.19 |

| 5 | 2 | 0 | Campos, Ana Claudia | 1.19 |

| 6 | 2 | 0 | Shih, Naai-Jung | 1.19 |

5.4 Country and Institutional Analysis

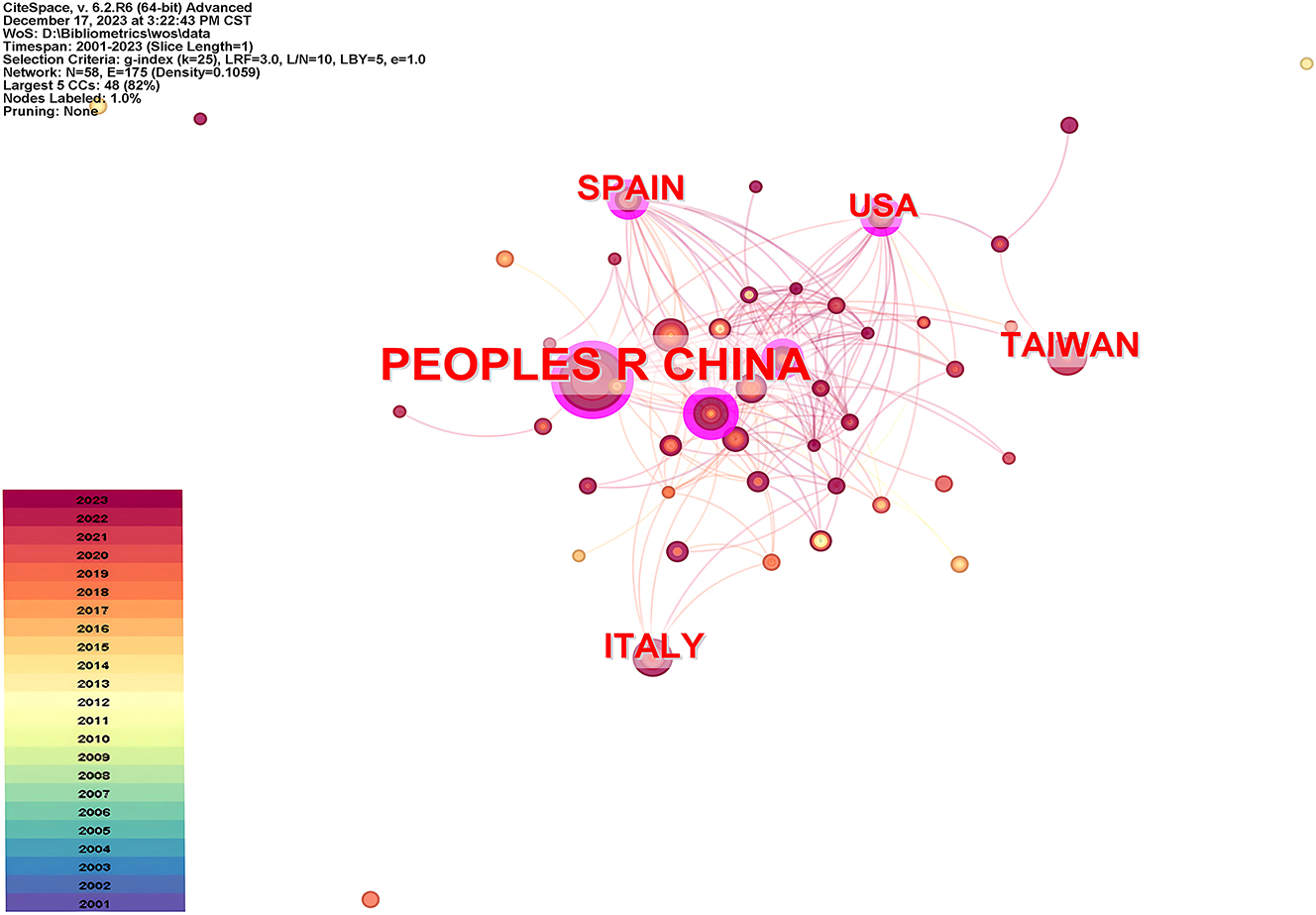

Based on country and region-specific statistics, the software generated a network comprising 58 nodes and 175 connections. This signifies the active participation of 58 countries in pertinent research endeavors as reflected in their published papers. The size of each node is indicative of the publication count for the respective country. The observed cooperation density rate across diverse countries engaged in related fields is calculated at 0.1059 (refer to Figure 4).

Cooperative relationship map of country in cultural heritage tourism research.

The data reveals a significant discrepancy in publication volumes, with China leading substantially by contributing 45 papers, constituting 26.78 % of the total. Italy, securing the second position, has 17 articles, representing 10.11 % of the overall count, followed closely by Taiwan, China, with 16 articles and a 9.52 % share. This notable disparity is attributed to the extensive cultural heritage bases in both China and Italy, facilitating easier identification of research entry points. Simultaneously, there is a lot of related research that needs to be invested. Rounding out the top five, Spain and the United States occupy the fourth and fifth positions with 15 and 13 articles, respectively (refer to Table 3).

Top nine countries and regions in related research.

| Serial number | Count | Centrality | Institution | Proportion (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 45 | 0.14 | China | 26.78 |

| 2 | 17 | 0 | Italy | 10.11 |

| 3 | 16 | 0.01 | Taiwan | 9.52 |

| 4 | 15 | 0.2 | Spain | 8.92 |

| 5 | 13 | 0.19 | USA | 7.73 |

| 6 | 12 | 0.1 | England | 7.14 |

| 7 | 11 | 0.05 | Australia | 6.54 |

| 8 | 8 | 0.05 | Portugal | 4.75 |

| 9 | 8 | 0.21 | Germany | 4.76 |

In terms of research centrality, Germany takes the lead with a centrality value of 0.21, followed by the United States at 0.19 and China at 0.14. Despite China boasting the highest number of publications, its centrality lags behind that of the United States, ranking fifth, and Germany, ranking eighth. This observation implies that Germany exhibits a substantial degree of collaboration and research cooperation within related research domains, closely followed by the United States (refer to Table 3).

A comprehensive understanding of the institutions engaged in cultural heritage tourism research is instrumental in elucidating the overall landscape of research in this field and fostering international collaboration among these entities (Zhang et al. 2023). Table 4 elucidates the outcomes of the selection of institutions for operational involvement and data collection within the software employed for this study. The table reveals a total of 199 network nodes, forming 189 inter-institutional cooperative connection lines, resulting in a cooperation density rate of 0.0096 within various countries’ domains. This signifies the participation of 199 institutions as the primary contributors to related research and paper publications, encompassing 189 subsidiary cooperative relationships among these entities. Regarding the quantity of published articles, Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche (CNR), Griffith University, and Griffith University Gold Coast Campus secure the top three positions, each with three articles. However, despite their prolific publication output, these institutions do not feature in the top three regarding the centrality of cooperative relationships with other institutions. Only Bundeswehr University Munich, Hong Kong Polytechnical University, and Sun Yat Sen University exhibit a centrality value of 0.01, while all other institutions register a centrality value of 0. This underscores that Bundeswehr University Munich, Hong Kong Polytechnical University, and Sun Yat Sen University maintain robust cooperative ties with other institutions (refer to Table 4).

Top six institutions in related research.

| Serial number | Count | Centrality | Institution |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | 0 | Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche (CNR) |

| 2 | 3 | 0 | Griffith University |

| 3 | 3 | 0 | Griffith University – Gold Coast Campus |

| 4 | 2 | 0.01 | Bundeswehr University Munich |

| 5 | 2 | 0.01 | Hong Kong Polytechnic University |

| 6 | 2 | 0.01 | Sun Yat Sen University |

5.5 Co-Citation Analysis

Co-citation analysis involves examining the co-citation relationship wherein a third scholarly paper cites two distinct literature works concurrently (Small 1973). The temporal scope for this analysis spans from 2001 to 2023. The findings of the data analysis are presented in Table 5.

Top eight citation authors in related research.

| Serial number | Cited times | Centrality | Cited author name |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 13 | 0.17 | Buhalis |

| 2 | 11 | 0.03 | Hair |

| 3 | 11 | 0.04 | Fornell |

| 4 | 10 | 0.2 | Pine |

| 5 | 9 | 0.14 | Jung |

| 6 | 9 | 0.01 | Gössling |

| 7 | 8 | 0.22 | Cohen |

| 8 | 8 | 0 | Kim |

The preeminent authors in terms of citation frequency are Buhalis, Hair, and Fornell, with their respective articles being cited 13, 11, and 11 times. Notably, Buhalis’ publication titled “Metaverse marketing: How the metaverse will shape the future of consumer research and practice” has garnered significant attention (Dwivedi et al. 2023). In this work, Buhalis delves into the marketing implications of the Metaverse, specifically focusing on its impact on cultural tourism. He emphasizes the need for research to explore factors facilitating a seamless transition between physical and digital realms, as well as the facilitation of interactions with digital and physical resources (Lourenço et al. 2010). However, Buhalis does not have the highest centrality value (Centrality = 0.17) for articles published in the relevant field. Cohen’s article has only eight citations but has a centrality of 0.22. On the other hand, Kim’s article has eight citations but has a centrality of 0. In addition, Hair and Fornell also have a high citation count of 11 but their centrality is also relatively low, at 0.03 and 0.04, respectively. These data suggest that for researchers to enhance both the efficiency and impact of their work they must prioritize not only the innovation within their articles but also foster academic collaboration among authors. Such cooperation is crucial for boosting academic centrality and elevating the overall impact of their research. This approach facilitates the active and rapid formation of core research teams, ultimately leading to an increase in high-quality research output within relevant fields, thereby strengthening the scholarly community and advancing the discourse surrounding cultural heritage tourism.

5.6 Keyword Co-Occurrence Analysis

The selection of keywords for co-occurrence analysis serves as a pivotal data indicator for statistical and analytical purposes within the context of this study. The outcome reveals a total of 338 keywords pertinent to the research within the domain of software display (refer to Figure 5).

Co-occurrence map of keywords in cultural heritage tourism research.

Subsequently, the analytical procedure necessitates the exclusion of keywords identical to the search terms, along with the amalgamation of synonymous keywords. The tabulated findings, presented in Table 7, showcase the five most frequently encountered keywords, denoted by their respective frequencies: experience (30 occurrences), augmented reality (20 occurrences), satisfaction (9 occurrences), virtual reality (9 occurrences), and behavior (9 occurrences). Notably, the centrality values for the initial two keywords, experience (0.49) and augmented reality (0.14), are comparatively high. The remaining three keywords exhibit lower centrality values: satisfaction (0.05), virtual reality (0.03), and behavior (0.02) (refer to Table 6).

Five keywords in related research.

| Serial number | frequency | Centrality | Keywords |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 30 | 0.49 | Experience |

| 2 | 20 | 0.14 | Augmented reality |

| 3 | 9 | 0.05 | Satisfaction |

| 4 | 9 | 0.03 | Virtual reality |

| 5 | 9 | 0.02 | Behavior |

5.7 Experience

Experience is a multifaceted phenomenon defying concise definition, encapsulating a complex interplay of environmental, formal, and social factors that collectively shape a situation and confer it with value (Andrades and Dimanche 2018). Within the realm of tourist experiences facilitated through interactive processes, the ultimate objective is to craft enduring memories that visitors will fondly recall and share within their respective social networks (Neuhofer et al. 2012). Consequently, tourism organizations and destinations must strive to imprint experiences on the memory of visitors (Campos et al. 2016). Numerous researchers have embarked on innovative explorations within the domain of tourism interactive experiences. An examination of co-creation within cultural heritage tourism reveals that heightened levels of attention and memorability are intricately linked to specific cognitive and physical activities, underscoring the impact of on-site co-creation on directing a visitor’s focus. Furthermore, as the comprehension of experience deepens, scholars have introduced the concept of sustainable experiences in heritage tourism. Such experiences elicit profound, meaningful emotions and memories, fostering tourists’ commitment to destination sustainability through interactions with the natural and cultural environment, insights, views, and contextual activities. Strategies are devised for specific types of scenic areas to amplify visitor engagement experiences. From the current research, a large number of papers still focus on the improvement of tourism experience through new technologies, which is only an extension of existing research.

5.8 Augmented Reality

Augmented Reality (AR) technology is designed to process and display real-time three-dimensional (3D) data within a physical environment, providing a highly visual and interactive platform that facilitates access to and understanding of information relevant to cultural tourism. Technological advancements, such as AR, enable visitors to interact with a personalized environment (Jung et al. 2018). In the realm of cultural heritage tourism, AR is increasingly employed to enrich tourist experiences (De Vos and Witlox 2017). Furthermore, numerous historical artifacts and cultural heritage sites worldwide have been digitally preserved in 3D, effectively safeguarding them from potential damage by tourists. The broad applicability of AR is particularly significant in urban heritage tourism, where it, alongside virtual reality, offers a compelling avenue for heritage site preservation (De Vos et al. 2019). As far as current research is concerned, interactive design is only a manifestation of AR application in heritage tourism and cannot substantially improve efficiency through the design process.

5.9 Satisfaction

In cultural heritage travel, satisfaction encompasses the spectrum of positive or negative emotions experienced during a journey, coupled with a cognitive assessment of the overall trip (Chen et al. 2022). Given individuals’ inclination towards seeking happiness and contentment, the enjoyment derived from a travel experience can significantly shape attitudes towards the chosen mode of travel, consequently impacting future mode preferences (Ma Sabiote et al. 2012). Numerous studies have delved into the factors influencing travel satisfaction with the aim of enhancing overall travel experiences (Mazuryk and Gervautz 1996). For example, Carmen investigated the influence of cultural dimensions on the correlation between e-service quality and online tourist satisfaction. The study revealed that the impact of service quality dimensions on tourists’ satisfaction with online purchases is moderated by cultural dimensions such as uncertainty avoidance and individualism/collectivism (Jia et al. 2023). In empirical research on cultural tourism, technologies that facilitate visitors’ active engagement present opportunities for interactions among fellow visitors. From existing literature, it can be seen that relevant researchers have noticed that interaction design can provide new ideas for improving satisfaction with heritage tourism but current research has not considered this issue from the perspective of interaction design.

5.10 Virtual Reality

Virtual Reality (VR) encompasses various definitions, all interconnected with the fundamental concepts of simulation, interaction, and immersion. It represents a digital environment that serves as a simulation, enabling interaction and immersion so realistic that users perceive themselves as existing within that virtual world (Pagano et al. 2020). Advancements in information technology, particularly the rise of virtual reality and the emergence of the metaverse, have instigated a significant transformation in digital experiences, especially in the domain of cultural heritage tourism (Jia et al. 2023). The integration of virtual reality technologies in cultural heritage (CH) endeavors facilitates the creation of a more immersive and profound connection with visitors. Such tools have the capability to virtually reconstruct ancient life scenarios, enabling artifacts, landscapes, environments, and characters to coexist and interact in a cohesive manner (Jia et al. 2023). Existing research has focused too much on how this technology can be applied to heritage tourism but has overlooked how to shield the negative impact of VR through interactive processes.

5.11 Behavior

Current research on the adoption behavior of digital heritage services predominantly focuses on users’ assessments of behavioral outcomes (Acharya, Mekker, and De Vos 2023). Additionally, studies on travel behavior aim to enhance travel satisfaction by examining its connections with overall and domain-specific life satisfaction (Wu and Pearce 2016). In the domain of interactive and sensory affordances during cultural heritage tourism, Weiwei Jia emphasizes the significance of embodied cognition and psychological distance as parallel mediators in the influence of sensory affordances on adoption (Acharya et al. 2021). Life events and their influence on tourism behavior possess specific attributes, including variations in timing or duration (Damiano et al. 2008). Indeed, in the current stage of tourism evolution, researchers have abundant opportunities to explore the forces that mold the diverse behaviors of tourists, but due to professional limitations they neglected to study the impact of interaction design on tourist behavior from an interdisciplinary perspective.

The embodiment of these five main keywords predominantly explores tourists’ psychological experiences within the realm of tourism through the lenses of computer technology and psychology. Firstly, interaction design is primarily manifested in the development and application of virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR). These technologies enable the reproduction and artistic expression of cultural heritage through interactive design and the simulation of graphic and image technologies, effectively showcasing the coexistence of heritage across temporal and spatial dimensions. Secondly, whether examining human interactions, interactions with digital devices, or engagements with heritage landscapes, the focus lies on uncovering innovative sensations within the tourism experience to captivate tourists. This approach not only enhances memory but also facilitates or simplifies interactive behaviors rooted in original experiences, enriching the psychological landscape associated with past interactions. Consequently, it becomes evident that an increasing body of research has examined the practical significance of interaction design, particularly in its role in advancing cultural heritage tourism.

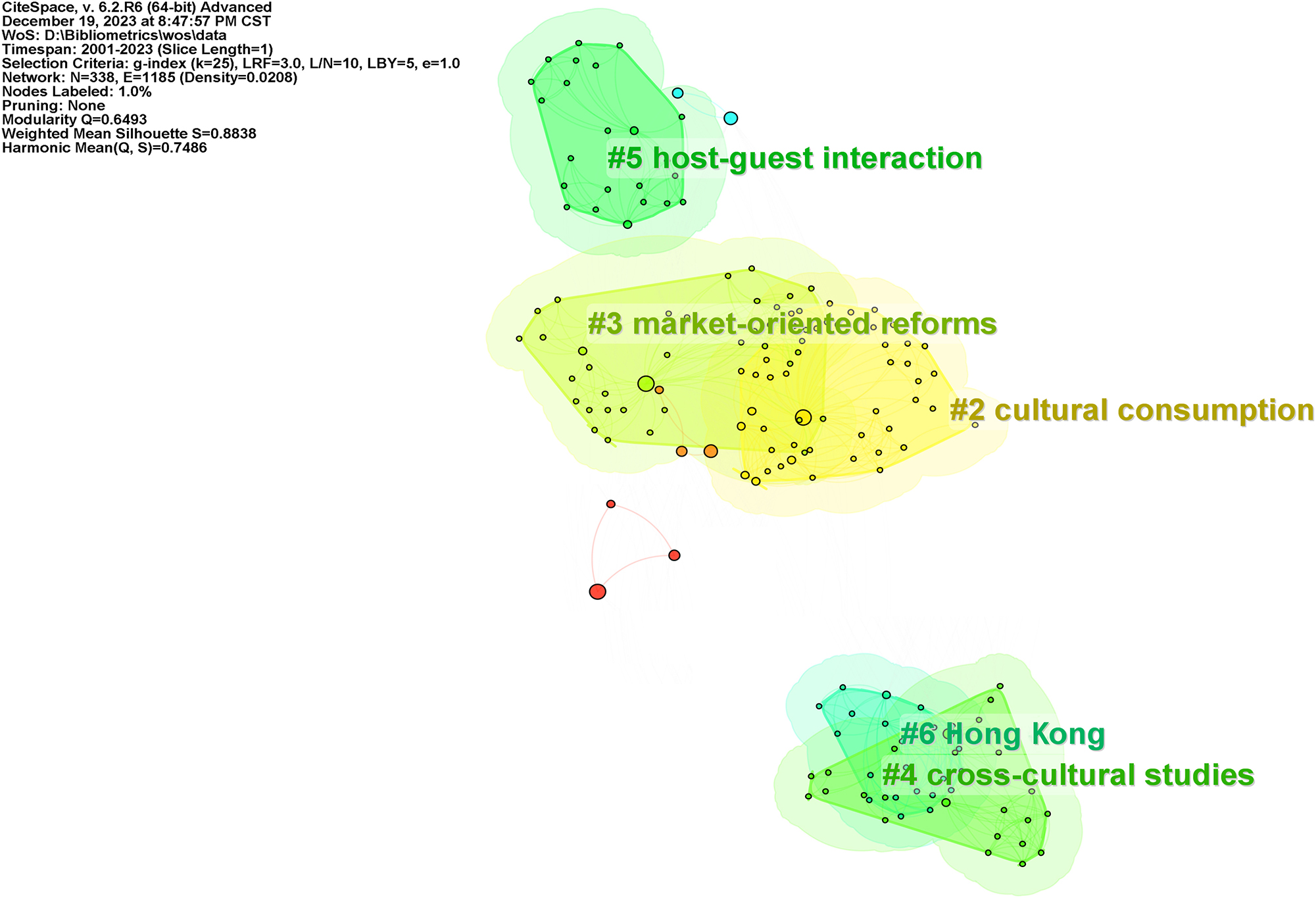

5.12 Keyword Cluster Analysis

In the software, point and cluster analysis, and then enter K, keywords can be integrated in order to do keyword cluster analysis by using log-likelihood ratio (LLR). The result shows that Modularity Q = 0.6493 and Sihouette = 0.8838. CiteSpace provides modularity and silhouette metrics based on network structure and clustering clarity, namely module value (Q value) and average contour value (S value), which can serve as a basis for evaluating the effectiveness of graph drawing. Generally speaking, the Q value is generally within the interval (o, 1), and a Q > 0.3 indicates that the divided community structure is significant. When the S value is 0.7, clustering is efficient and convincing, and if it is above 0.5 clustering is generally considered reasonable. After analysing, the software shows the clustered keywords in 13 categories. Then the study removes the clustering terms that are the same as the theme, keywords, and then removes the clustering terms with smaller size values and smaller article bases which will present five more important clustering keywords, which are #2 cultural consumption, #3 market-oriented reform, #4 cross-cultural studies, #5 host-guest interaction, and #6 Hong Kong (refer to Figure 6 and Table 7). Due to the lack of typical research direction for “Hong Kong” as a keyword, it will not be specifically discussed in the study.

Cluster of keyword in related research (note: The # number in the figure represents the ID of the software generated cluster of keywords).

Information of top 5 terms in related research.

| Cluster ID | Size | Silhouette | Year | Top term |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| #2 | 43 | 0.874 | 2019 | Cultural consumption |

| #3 | 41 | 0.908 | 2015 | Market-oriented reform |

| #4 | 26 | 0.875 | 2012 | Cross-cultural studies |

| #5 | 23 | 0.916 | 2017 | Host-guest interaction |

5.13 Cultural Consumption

Cultural consumption plays a pivotal role in enhancing residents’ consumption quality and bolstering domestic demand (Liu et al. 2021). The augmentation of tourism consumption exhibits a positive correlation with the enhancement of residents’ cultural proficiency, income escalation, and the advancement of cultural industries (Richards 1996). The utilization of interaction design bears a direct association with the cultural consumption behaviors exhibited by tourists in the context of cultural heritage tourism, emerging as a crucial component in stimulating consumption within the tourism economy. Furthermore, Kesgin extended the consumer-based model of authenticity by introducing sincere hospitality as a relational encounter between host and guest. This interaction influences social engagement, interaction, and memorability within the unique context of a living history site, demonstrating its efficacy in discerning visitors based on their on-site purchases.

5.14 Market-Oriented Reform

Market-oriented reform exerts a profound influence on the operational flexibility and capital structure adjustments within the cultural heritage tourism industry, consequently shaping the trajectory and impetus of its development (Zhou and Sotiriadis 2021). The focus on interaction design is inherently aligned with market-oriented reforms, serving as a catalyst to unlock the inherent value of cultural heritage tourism and elevate the tourism experience and consumption within pertinent markets. Within the sphere of industrial convergence in cultural heritage tourism, empirical evidence indicates a positive correlation between labor convergence and the industry. Simultaneously, a negative relationship emerges between government involvement and convergence when accounting for control variables in econometric models. In terms of moderating effects, the interplay between information and communications technologies and market-oriented reforms demonstrates a positive correlation with industrial convergence (Nicholls 2011).

5.15 Cross-Cultural Studies

Interactions among customers from diverse cultures wield a potentially profound influence on customer satisfaction. The recognition of both commonalities and distinctions existing between cultures is widely acknowledged as pertinent to comprehending consumer behavior and perceptions within the realm of cultural heritage tourism (Batat and Prentovic 2014). A study has undertaken the analysis of online tourism advertisements on platforms like YouTube, Vimeo, and Dailymotion, focusing on the cultural contexts of the UK, France, and Serbia. Employing a qualitative approach rooted in visual methods, the research identifies sustainable tourism dimensions and discourses within each context. This exploration utilizes intra- and intertextual analysis, embodying a design grounded in systems thinking (Liu-Lastres and Cahyanto 2021).

5.16 Host-Guest Interaction

Host-guest interactions play a pivotal role in the tourism sector and manifest in diverse contexts, such as interactions between tour guides and tourists, interactions among locals and visitors, and interactions between online visitors and systems, among others (Dadfar et al. 2013). Within the realm of customer-service provider engagements customers emerge as co-producers of service, and the quality of service encounters can be significantly augmented through the implementation of personalized service marketing strategies. Notably, empirical findings indicate that guides actively embrace sustainable tourism practices, drawing upon their local religious wisdom and experiences in a concerted effort to foster harmonious relationships between hosts and guests (Pu et al. 2023). This collaborative engagement between hosts and guests contributes to the co-creation of value, particularly in the context of local sustainable tourism practices.

Through the four primary themes identified in the keyword cluster analysis, it is evident that researchers have approached the enhancement of cross-cultural identity and the mitigation of barriers between hosts and guests from the perspective of interaction design. The ultimate aim of related research is to improve both the quality and quantity of cultural consumption in a market-oriented context. Driven by this objective, it becomes clear that researchers have successfully proposed and developed innovative content through interactive design within the realm of cultural heritage tourism. This emphasis on interaction design not only fosters deeper connections between diverse cultural identities but also enhances the overall tourist experience, thereby contributing to a more inclusive and dynamic cultural landscape.

5.17 Trends in Related Research

Within this examination, the Burstness panel was employed, with the Threshold set at 0.1 and the Minimum Duration at 2, resulting in the identification of 20 noteworthy developments in keyword research. Subsequently, keywords sharing common themes and those with intensity values below 0.7 were excluded, leading to the identification of 16 distinct trends in keyword development.

Upon scrutinizing the outcomes, it becomes evident that “Virtual Reality” emerges as the term with the highest Strength value, signifying a greater abundance of associated articles and heightened attention from publishers and researchers in this particular domain. Conversely, domains such as “Behavior,” “Policy,” “3D Survey,” and “Archaeological and Heritage Preservation” have only recently garnered research focus, predicting that they will be central areas of interest for researchers, remaining prominent until 2023. This observation implies that the identified research entry points will persist as primary directions in the forthcoming period (refer to Table 8).

Top emerging keywords in cultural heritage tourism research, 2002 to 2020.

| Keywords | Year | Strength | Begin | End | 2001–2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indicators | 2009 | 1.23 | 2009 | 2010 | ▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▃▃▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂ |

| Chinese | 2010 | 1.03 | 2010 | 2014 | ▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▃▃▃▃▃▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂ |

| Hospitality Management | 2011 | 1.19 | 2011 | 2013 | ▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▃▃▃▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂ |

| Cross-Cultural Studies | 2011 | 1.11 | 2011 | 2014 | ▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▃▃▃▃▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂ |

| Perceptions | 2009 | 1.58 | 2012 | 2016 | ▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▃▃▃▃▃▂▂▂▂▂▂▂ |

| Management | 2014 | 1.23 | 2014 | 2016 | ▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▃▃▃▂▂▂▂▂▂▂ |

| Model | 2014 | 1.22 | 2014 | 2018 | ▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▃▃▃▃▃▂▂▂▂▂ |

| Community | 2014 | 0.91 | 2014 | 2015 | ▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▃▃▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂ |

| Destination | 2014 | 0.8 | 2014 | 2019 | ▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▃▃▃▃▃▃▂▂▂▂ |

| Virtual Reality | 2016 | 3.49 | 2016 | 2020 | ▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▃▃▃▃▃▂▂▂ |

| Innovation | 2016 | 1.42 | 2016 | 2019 | ▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▃▃▃▃▂▂▂▂ |

| Satisfaction | 2010 | 1.02 | 2018 | 2020 | ▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▃▃▃▂▂▂ |

| Behavior | 2018 | 1.28 | 2020 | 2023 | ▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▃▃▃▃ |

| Policy | 2021 | 2.32 | 2021 | 2023 | ▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▃▃▃ |

| 3d Survey | 2021 | 0.92 | 2021 | 2023 | ▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▃▃▃ |

| Archaeological and Heritage Preservation | 2021 | 0.92 | 2021 | 2023 | ▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▃▃▃ |

The foremost trend in terms of intensity, as indicated by a value of 3.49, revolves around “Virtual Reality,” reaching its pinnacle between 2016 and 2020. This surge aligns with the advancing maturity of digital technologies. Notably, conventional modes of information presentation, such as text and images, are gradually being supplanted by interactive and immersive formats. This transformative shift presents opportunities for mitigating psychological distance, thereby enhancing engagement and connection with the presented content.

6 Discussion and Conclusions

This study starts from the relationship between cultural heritage tourism and interaction design in the literature to fill the gap in research in this field. This study employed Citespace software to analyze 168 papers retrieved from the Web of Science, focusing on aspects such as publication volume, keyword time zone analysis, author collaboration, country and institutional analysis, co-citation analysis, and keyword co-occurrence trends, while also organizing the resultant key data. The findings from this analysis not only reflect the degree and trajectory of research development but also critically highlight existing research challenges, thereby fostering a more comprehensive exploration of ideas in cultural heritage research through interaction design (refer to Figure 7).

The research structure and framework.

Firstly, the research landscape in related fields has evolved through three distinct stages: the initial stage (2001–2008), the stable development stage (2009–2015), and the explosive growth stage (2016–2023). Each stage reflects research outputs shaped by varying social contexts, policy environments, and technological advancements. Analysis of these stages reveals that existing research predominantly focuses on the intersections between the heritage tourism industry and computer technology, with cultural consumption driven by marketization serving as the core theme. In these topics and stages of development, literature research reflects certain discussions. The research advancements of the contemporary era have yet to offer more effective solutions to the longstanding research challenges previously identified. These advancements cannot contribute to resolving the isolating dynamics between individuals and heritage landscapes observed in earlier research. These inquiries underscore the importance of continuity and relevance in the application of interaction design within cultural heritage tourism, emphasizing the need for discussions that extend beyond contemporary profit-driven perspectives.

Secondly, in terms of collaborative relationships, the study identified five authors with high centrality. Secondly, countries such as China, Italy, and Spain have made the greatest contributions in related fields. Meanwhile, papers published by authors such as Buhalis, Hair, and Fornell have a high number of citations. These cooperative relationships illustrate significant collaborative achievements and positive interrelations, particularly emphasizing the volume of publications and the richness of cultural heritage resources, alongside the innovation and academic prominence of the respective papers. While abundant cultural heritage tourism resources correlate with an increase in publication volume within related fields, they do not inherently dictate the innovative quality of the research outputs. The level of innovation exhibited in a paper is influenced not only by the originality of its content but also by its academic centrality, which encompasses the presence of a core research team and the extent of academic collaboration. High-quality and quantitatively advantageous academic partnerships are instrumental in fostering innovative advancements in the interactive design applied to cultural heritage tourism. Thus, to enhance the quantity, quality, and innovation of research in this area, it is imperative to prioritize regions rich in cultural heritage tourism resources while simultaneously strengthening collaborative research efforts and academic partnerships among authors, institutions, and nations.

Thirdly, five high-frequency keywords mainly appeared in the research analysis, namely experience, augmented reality, satisfaction, virtual reality, and behavior. These keywords covers the main content of research in this field. The research content encapsulated by these keywords illustrates that scholars have engaged in interdisciplinary inquiries aligned with contemporary trends, whether from technical or ideological vantage points. This body of work highlights the establishment of meaningful connections between individuals and cultural heritage tourism, emphasizing critical factors such as usefulness, usability, emotionality, and sustainability. However, existing studies have often overlooked the interactive dynamics between people, whether direct or mediated through digital platforms. Consequently, it is essential for researchers to consider the intricate relationships between humans and digital machines, as well as the interplay of interdisciplinary perspectives across temporal boundaries, in the forthcoming stages of research.

Fourthly, the findings from the Keyword cluster analysis reveal that, despite the multifaceted nature of the cultural heritage tourism industry, research outputs primarily concentrate on cultural consumption, market-oriented reform, cross-cultural studies, and host-guest interaction. This indicates that the application of interaction design within cultural heritage tourism significantly enhances these four dimensions while simultaneously offering innovative insights that can steer the industry’s development in a more constructive direction. Therefore, examining the cultural heritage tourism sector through the lens of interaction design allows for the exploration of diverse facets of its developmental trajectory, identifying innovative opportunities at various stages of industry evolution. This approach not only broadens the scope for researchers to pursue new research directions but also fosters the innovative advancement of cultural heritage tourism as a whole.

Nevertheless, this study is subject to certain constraints. Firstly, the corpus comprises a modest 168 papers, reflecting the emergent nature of this research direction and its relatively late focus. The selection process prioritized the more authoritative and academically esteemed Web of Science (WOS) platform.

References

Acharya, S., M. Mekker, and J. De Vos. 2023. “Linking Travel Behavior and Tourism Literature: Investigating the Impacts of Travel Satisfaction on Destination Satisfaction and Revisit Intention.” Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives 17: 100745. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trip.2022.100745.Search in Google Scholar

Andrades, L., and F. Dimanche. 2018. “Co-creation of Experience Value: A Tourist Behaviour Approach.” In Creating Experience Value in Tourism, 83–97. Wallingford: CAB International.10.1079/9781786395030.0083Search in Google Scholar

Aria, M., and C. Cuccurullo. 2017. “Bibliometrix: An R-Tool for Comprehensive Science Mapping Analysis.” Journal of Informetrics 11 (4): 959–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2017.08.007.Search in Google Scholar

Barnes, S. J. 2022. “Heritage Protection and Tourism Income: The Tourism Heritage Kuznets Curve.” Tourism Review 77 (6): 1455–71. https://doi.org/10.1108/tr-03-2022-0125.Search in Google Scholar

Batat, W., and S. Prentovic. 2014. “Towards Viral Systems Thinking: A Cross-Cultural Study of Sustainable Tourism Ads.” Kybernetes 43 (3/4): 529–46. https://doi.org/10.1108/k-07-2013-0147.Search in Google Scholar

Bolin, G. 2012. “Introduction: Cultural Technologies in Cultures of Technology.” In Cultural Technologies, 1–15. Routledge.10.4324/9780203117354Search in Google Scholar

De Beukelaer, C. 2014. “The UNESCO/UNDP 2013 Creative Economy Report: Perks and Perils of an Evolving Agenda.” The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society 44 (2): 90–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/10632921.2014.895789.Search in Google Scholar

Campos, A. C., J. Mendes, P. O. do Valle, and N. Scott. 2016. “Co-creation Experiences: Attention and Memorability.” Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 33 (9): 1309–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2015.1118424.Search in Google Scholar

Canton, H. 2021. “World Tourism Organization—UNWTO.” In The Europa Directory of International Organizations 2021, 393–7. Routledge.10.4324/9781003179900-60Search in Google Scholar

Chen, C. 2006. “CiteSpace II: Detecting and Visualizing Emerging Trends and Transient Patterns in Scientific Literature.” Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 57 (3): 359–77. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.20317.Search in Google Scholar

Chen, Z., D. van Lierop, and D. Ettema. 2022. “Travel Satisfaction with Dockless Bike-Sharing: Trip Stages, Attitudes and the Built eEvironment.” Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment 106: 103280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2022.103280.Search in Google Scholar

Dadfar, H., S. Brege, and S. S. Ebadzadeh Semnani. 2013. “Customer Involvement in Service Production, Delivery and Quality: The Challenges and Opportunities.” International Journal of Quality and Service Sciences 5 (1): 46–65. https://doi.org/10.1108/17566691311316248.Search in Google Scholar

Damiano, R., C. Gena, V. Lombardo, F. Nunnari, and A. Pizzo. 2008. “A Stroll with Carletto: Adaptation in Drama-Based Tours with Virtual Characters.” User Modeling and User-Adapted Interaction 18: 417–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11257-008-9053-1.Search in Google Scholar

Dwivedi, Y. K., L. Hughes, Y. Wang, A. A. Alalwan, S. J. Ahn, J. Balakrishnan, J. Wirtz, et al.. 2023. “Metaverse Marketing: How the Metaverse Will Shape the Future of Consumer Research and Practice.” Psychology and Marketing 40 (4): 750–76. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21767.Search in Google Scholar

Funkhouser, E. T. 1996. “The Evaluative Use of Citation Analysis for Communication Journals.” Human Communication Research 22 (4): 563–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.1996.tb00379.x.Search in Google Scholar

Giuffrida, D., V. Mollica Nardo, D. Neri, G. Cucinotta, I. V. Calabrò, L. Pace, and R. C. Ponterio. 2021. “A Multi-Analytical Study for the Enhancement and Accessibility of Archaeological Heritage: The Churches of San Nicola and San Basilio in Motta Sant’Agata (RC, Italy).” Remote Sensing 13 (18): 3738. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs13183738.Search in Google Scholar

Giuffrida, D., V. M. Nardo, D. Neri, G. Cucinotta, V. I. Calabrò, L. Pace, and R. C. Ponterio. 2022. “Digitization of Two Urban Archaeological Areas in Reggio Calabria (Italy): Roman Thermae and Greek Fortifications.” Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 43: 103441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2022.103441.Search in Google Scholar

Guo, Y., Z. Y. R. Xu, M. T. Cai, W. X. Gong, and C. H. Shen. 2022. “Epilepsy with Suicide: A Bibliometrics Study and Visualization Analysis via CiteSpace.” Frontiers in Neurology 12: 823474. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2021.823474.Search in Google Scholar

Jia, W., H. Li, M. Jiang, and L. Wu. 2023. “Melting the Psychological Boundary: How Interactive and Sensory Affordance Influence Users’ Adoption of Digital Heritage Service.” Sustainability 15 (5): 4117. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054117.Search in Google Scholar

Jung, T. H., H. Lee, N. Chung, and M. C. tom Dieck. 2018. “Cross-cultural Differences in Adopting Mobile Augmented Reality at Cultural Heritage Tourism Sites.” International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 30 (3): 1621–45. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijchm-02-2017-0084.Search in Google Scholar

Lee, J.-G., and M. Kang. 2015. “Geospatial Big Data: Challenges and Opportunities.” Big Data Research 2 (2): 74–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bdr.2015.01.003.Search in Google Scholar

Li, X., and L. Hua. 2018. “A Visual Analysis of Research on Information Security Risk by Using CiteSpace.” IEEE Access 6: 63243–57. https://doi.org/10.1109/access.2018.2873696.Search in Google Scholar

Liu, H., S. Lu, X. Wang, and S. Long. 2021. “The Influence of Individual Characteristics on Cultural Consumption from the Perspective of Complex Social Network.” Complexity 1: 7404690. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/7404690.Search in Google Scholar

Liu, S., and Y. Pan. 2023. “Exploring Trends in Intangible Cultural Heritage Design: A Bibliometric and Content Analysis.” Sustainability 15 (13): 10049. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151310049.Search in Google Scholar

Liu-Lastres, B., and I. P. Cahyanto. 2021. “Exploring the Host-Guest Interaction in Tourism Crisis Communication.” Current Issues in Tourism 24 (15): 2097–09. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1817876.Search in Google Scholar

Lourenço, P. B., F. Peña, and M. Amado. 2010. “A Document Management System for the Conservation of Cultural Heritage Buildings.” International Journal of Architectural Heritage 5 (1): 101–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/15583050903318382.Search in Google Scholar

Ma Sabiote, C., D. Ma Frias, and J. Alberto Castañeda. 2012. “E-Service Quality as Antecedent to E-Satisfaction: The Moderating Effect of Culture.” Online Information Review 36 (2): 157–74. https://doi.org/10.1108/14684521211229011.Search in Google Scholar

Mazuryk, T., and M. Gervautz. 1996. “Virtual Reality-History, Applications, Technology and Future.” Vienna University of Technology, Vienna 10 (6).Search in Google Scholar

Neuhofer, B., D. Buhalis, and A. Ladkin. 2012. “Conceptualising Technology Enhanced Destination Experiences.” Journal of Destination Marketing & Management 1 (1–2): 36–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2012.08.001.Search in Google Scholar

Nicholls, R. 2011. “Customer – to – Customer Interaction (CCI): A Cross-Cultural Perspective.” International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 23 (2): 209–23. https://doi.org/10.1108/09596111111119338.Search in Google Scholar

Oliverio, J. 2018. “A Survey of Social Media, Big Data, Data Mining, and Analytics.” Journal of Industrial Integration and Management 3 (3): 1850003. https://doi.org/10.1142/s2424862218500033.Search in Google Scholar

Pagano, A., A. Palombini, G. Bozzelli, M. De Nino, I. Cerato, and S. Ricciardi. 2020. “ArkaeVision VR Game: User Experience Research Between Real and Virtual Paestum.” Applied Sciences 10 (9): 3182. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10093182.Search in Google Scholar

Pu, P., L. Cheng, W. H. M. S. Samarathunga, and G. Wall. 2023. “Tour Guides’ Sustainable Tourism Practices in Host-Guest Interactions: When Tibet Meets the West.” Tourism Review 78 (3): 808–33. https://doi.org/10.1108/tr-04-2022-0182.Search in Google Scholar

Richards, G. 1996. “Production and Consumption of European Cultural Tourism.” Annals of Tourism Research 23 (2): 261–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(95)00063-1.Search in Google Scholar

Russo, A. P., and J. Van Der Borg. 2002. “Planning Considerations for Cultural Tourism: A Case Study of Four European Cities.” Tourism Management 23 (6): 631–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0261-5177(02)00027-4.Search in Google Scholar

Skublewska-Paszkowska, M., M. Milosz, P. Powroznik, and E. Lukasik. 2022. “3D Technologies for Intangible Cultural Heritage Preservation—Literature Review for Selected Databases.” Heritage Science 10 (1): 3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-021-00633-x.Search in Google Scholar

Small, H. 1973. “Co-citation in the Scientific Literature: A New Measure of the Relationship between Two Documents.” Journal of the American Society for Information Science 24 (4): 265–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.4630240406.Search in Google Scholar

Song, H., P. Chen, Y. Zhang, and Y. Chen. 2021. “Study Progress of Important Agricultural Heritage Systems (IAHS): A Literature Analysis.” Sustainability 13 (19): 10859. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131910859.Search in Google Scholar

Środa-Murawska, S., E. Grzelak-Kostulska, J. Biegańska, and L. S. Dąbrowski. 2021. “Culture and Sustainable Tourism: Does the Pair Pay in Medium-Sized Cities?” Sustainability 13 (16): 9072. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13169072.Search in Google Scholar

Tress, B., and G. Tress. 2001. “Capitalising on Multiplicity: A Transdisciplinary Systems Approach to Landscape Research.” Landscape and Urban Planning 57 (3–4): 143–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0169-2046(01)00200-6.Search in Google Scholar

De Vos, J., and F. Witlox. 2017. “Travel Satisfaction Revisited. On the Pivotal Role of Travel Satisfaction in Conceptualising a Travel Behaviour Process.” Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 106: 364–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2017.10.009.Search in Google Scholar

De Vos, J., T. Schwanen, V. Van Acker, and F. Witlox. 2019. “Do Satisfying Walking and Cycling Trips Result in More Future Trips with Active Travel Modes? an Exploratory Study.” International Journal of Sustainable Transportation 13 (3): 180–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/15568318.2018.1456580.Search in Google Scholar

Wu, M., and P. L. Pearce. 2016. “Tourism Blogging Motivations: Why Do Chinese Tourists Create Little Lonely Planets?” Journal of Travel Research 55 (4): 537–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287514553057.Search in Google Scholar

Yang, C., and T. Liu. 2022. “Social Media Data in Urban Design and Landscape Research: A Comprehensive Literature Review.” Land 11 (10): 1796. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11101796.Search in Google Scholar

Yu, C. 2021. “Retracted Article: Climate Environment of Coastline and Urban Visual Communication Art Design from the Perspective of GIS.” Arabian Journal of Geosciences 14: 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12517-021-06692-5.Search in Google Scholar

Zhang, S., J. Liang, X. Su, Y. Chen, and Q. Wei. 2023. “Research on Global Cultural Heritage Tourism Based on Bibliometric Analysis.” Heritage Science 11 (1): 139. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-023-00981-w.Search in Google Scholar

Zhou, C., and M. Sotiriadis. 2021. “Exploring and Evaluating the Impact of ICTs on Culture and Tourism Industries’ Convergence: Evidence from China.” Sustainability 13 (21): 11769. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132111769.Search in Google Scholar

Zhu, X., and S.-C. Chiou. 2022. “A Study on the Sustainable Development of Historic District Landscapes Based on Place Attachment Among Tourists: A Case Study of Taiping Old Street, Taiwan.” Sustainability 14 (18): 11755. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811755.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Moving into 2025

- Articles

- New Contributions to Iron Gall Ink Inspection Protocols Using Open Source Surface Analysis and Digital Imaging

- Passing Down Local Memories: Generativity and Photo Donations in Preservation Institutions

- Oral History Metadata and AI: A Study from an LGBTQ+ Archival Context

- Exploring Design Aspects of Online Museums: From Cultural Heritage to Art, Science and Fashion

- Can Social Media Pave the Way for the Preservation and Promotion of Heritage Sites?

- Exploring the Potential of Mobile Phone Applications in the Transmission of Intangible Cultural Heritage Among the Younger Generation

- The Application of Interaction Design in Cultural Heritage Tourism: A Systematic Literature Review

- List of Reviewers

- PDT&C Peer-Reviewers in 2023–2024

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Moving into 2025

- Articles

- New Contributions to Iron Gall Ink Inspection Protocols Using Open Source Surface Analysis and Digital Imaging

- Passing Down Local Memories: Generativity and Photo Donations in Preservation Institutions

- Oral History Metadata and AI: A Study from an LGBTQ+ Archival Context

- Exploring Design Aspects of Online Museums: From Cultural Heritage to Art, Science and Fashion

- Can Social Media Pave the Way for the Preservation and Promotion of Heritage Sites?

- Exploring the Potential of Mobile Phone Applications in the Transmission of Intangible Cultural Heritage Among the Younger Generation

- The Application of Interaction Design in Cultural Heritage Tourism: A Systematic Literature Review

- List of Reviewers

- PDT&C Peer-Reviewers in 2023–2024