Abstract

Previous research on syntactic complexity is primarily focused on the synchronic distribution of clausal and phrasal features and the diachronic shift from clausal elaboration to phrasal compression. However, the interrelationship between clause complexity and phrase complexity remains unexplored. This study investigated syntactic complexity at different linguistic levels across three disciplinary groups (Social Sciences, Humanities and Natural Sciences) using a corpus of research article abstracts. Sentence complexity was measured by the number of clauses per sentence, clause complexity by the number of clausal constituents per clause, and nominal group (NG) complexity by the number of words per NG. The results show that: (1) sentences are the least complex in Natural Science (NS) texts; (2) clauses are also the least complex in NS, despite having the highest average number of clausal constituents; (3) NGs are the most complex in NS texts. Furthermore, the study found that NG complexity could be more accurately measured by the number of premodifiers of the head noun (HN) of the NG. These findings have important implications for instructing English as a Foreign Language (EFL) learners in discipline-specific academic writing.

1 Introduction

Phrase complexity and clause complexity are the two interrelated aspects of syntactic complexity in linguistics research. Previous studies indicate that clause complexity is often characteristic of spoken texts (e.g. Bardovi-Harlig 1992; Biber and Conrad 2009; de Haan 1989; Fang et al. 2006; Halliday 1987; Ortega 2003; Rimmer 2006), whereas phrase complexity is more typical of written texts (e.g. Biber and Clark 2002; Biber and Finegan 2001; Gray 2021). Within the written registers, academic articles tend to favor nominalization and noun phrase embedding, reducing reliance on full subordinate clauses (Halliday 2004; Gray 2015). Research (e.g. Biber 2006; Casal et al. 2021; Dong et al. 2023; Hyland 2009; Lu et al. 2021; Mazgutova and Kormos 2015; Pan and Zhou 2024; Staples et al. 2016) also shows that linguistic complexity varies across disciplines within the academic register. Articles in hard sciences are denser in information and more difficult to understand (Gray 2013, 2021), whereas soft sciences value stylistic variation and rhetorical sophistication (Becher and Trowler 2001) and tend to use longer sentences with detailed descriptions, qualifications, and elaborations (Hyland 2004).

However, previous studies did not further investigate the interrelationship between clause complexity and phrase complexity across different types of texts. According to Köhler (1986, 2012), language operates as a self-organizing and self-regulating dynamic system. Altmann (1980) thereby proposed the Menzerath-Altmann Law, that is, the constituent length is a function of the construct length. Based on this linguistics law, an increase in phrase complexity in English academic writing could be expected to result in a decrease in clause complexity.

The present study aims to examine the interrelationship between clause complexity and phrase complexity in English academic writing, alongside a comparison of the distributions of the syntactic features at different linguistic levels across disciplines. For this purpose, a corpus of 1,050 research article abstracts (350 each from Social Sciences (SS), Humanities, and Natural Sciences (NS)) was compiled. We first performed binomial logistic regression to test the regularity of the data distributions. Subsequently, the Menzerath-Altmann Law was applied to explore the interrelationship between syntactic complexities at different linguistic levels across disciplines.

2 Variations in syntactic complexity

Syntactic complexity is generally defined as the degree of diversity and sophistication of syntactic structures in discourse (e.g. Lu 2017; Ortega 2003). The variation in syntactic complexity occurs in the diachronic shift from clausal elaboration to phrasal compression and the synchronic distribution of the clausal and phrasal features.

Research (Atkinson 1999; Biber and Finegan 2001; Biber and Gray 2010, 2016; Biber et al. 2011) shows that written English has shifted away from clausal subordination toward noun phrase expansion. This shift is particularly prominent in academic writing (Casal and Lee 2019; Halliday 2004; Halliday and Martin 1993). According to Biber and Finegan (2001), written registers have become more condensed and lexically dense over time, whereas spoken registers maintain a reliance on clause complexity. Atkinson (1999) traced the evolution of scientific discourse, demonstrating how the style of scientific writing from the 17th century to the present day had become progressively more nominalized and denser, favoring noun phrase complexity over clause subordination. Gray (2015) found that academic articles favored nominalization and noun phrase embedding, reducing reliance on full subordinate clauses. Biber et al. (2016) examined the writing of native English-speaking university students and observed a decrease in clausal features alongside an increase in phrasal features as students progressed through their academic levels. Fang et al. (2006) examined how noun phrase structures in academic texts created challenges for students, emphasizing the role of nominalization and dense information packaging. Gardner et al. (2019) demonstrated that university students’ writing exhibited register-dependent variations, with lower-level writing using more clauses and advanced writing using more complex noun phrases.

Syntactic complexity also varies across academic disciplines (e.g. Biber et al. 2016; Hyland 2004; Lu et al. 2021). Research (e.g. Bardovi-Harlig 1992; Khany and Kafshgar 2016; Lu et al. 2021) shows that soft science texts exhibit greater clause complexity by employing more finite subordination, adverbial clauses, and coordination. Ziaeian and Golparvar (2022) assessed the fine-grained clause and phrase complexities in the discussion sections of research articles in Applied Linguistics, Chemistry, and Economics, revealing that soft science texts contained more complex clause structures (e.g. dependents per clause). Hyland (2015) also found that soft disciplines (e.g. History and English) used more clause dependents such as adverbial modifiers, conjunctions, and auxiliaries, compared to hard disciplines (e.g. Math, Physics, and Chemistry).

Phrase complexity is primarily examined through the analysis of noun phrases. Noun phrases are found to be more complex (e.g. dependents per noun) in hard science texts compared to soft science texts (Khany and Kafshgar 2016). Lu et al. (2021), in their study of research article introductions, found that hard science disciplines like Chemistry and Electrical Engineering employed more nominal and adjectival premodifiers, whereas soft science fields such as Anthropology and Sociology showed a greater reliance on prepositional and clausal postmodifiers. Further refining this distinction, Hu and He (2023) observed that even among premodifiers, nominal premodifiers are more frequent in hard science texts, while adjectival premodifiers are more common in soft science texts.

Clause complexity, as conceptualized in previous research, is typically realized through the expansion of clauses via coordination or subordination (i.e. dependents per clause), and hence it is an inter-clause relation. Phrase complexity, on the other hand, is achieved through the expansion of phrases by means of pre- or post-modification (i.e. dependents per noun). Therefore, an increase in noun phrase complexity does not necessarily result in a decrease in clause complexity in the traditional sense. This highlights an intermediate level of intra-clause complexity, which can be realized through the addition of clausal constituents (i.e. dependents per process verbal group) in the Hallidayan sense. In the present study, we therefore define inter-clause complexity as sentence complexity and intra-clause complexity as clause complexity.

3 Syntactic complexity in systemic functional linguistics

The basic analytic unit in systemic functional linguistics is the clause (Halliday 1994). A clause may consist of one or more groups or phrases, and a group may further comprise one or more words in terms of the rank-scale hypothesis (Halliday 1961). Clause complexity in the Hallidayan sense can be measured by the number of groups or phrases in a clause, and group complexity can be measured by the number of words in a group. Similarly, sentence complexity can be assessed by counting the number of clauses within a sentence. This is illustrated in Example (1) quoted from Halliday and Matthiessen (1999: 343):

| They shredded the documents before they departed for the airport. |

|

Their shredding of the documents preceded their departure for the airport. |

The sentence in Example (1a) consists of two clauses, whereas that in Example (1b) contains only one clause. Hence, Example (1a) is structurally more complex than Example (1b) at the sentence level. According to Halliday and Matthiessen (1999), the simple clause in Example (1b) is derived through the nominalization of the two simple clauses in Example (1a) and the verbalization of the conjunction group before. Nominalization leads to longer nominal groups (NGs), while verbalization results in the simple clause observed in Example (1b). From this perspective, the simplification of syntactic structures is closely related to the increasing complexity of NGs.

Halliday and Matthiessen (2014) distinguished between two types of linguistic complexity: grammatical intricacy and lexical density. The clause complex in Example (1a) is more complex than the simple clause in Example (1b) in terms of grammatical intricacy. Although both the two clauses in Example (1a) and the single clause in Example (1b) are simple clauses consisting of three clausal constituents, they differ in lexical density. Lexical density is calculated by dividing “the number of lexical items by the number of ranking clauses” (Halliday and Matthiessen 2014: 727). For example, the lexical density of Example (1a) is 3, whereas that of Example (1b) is 7. Therefore, even though the two examples exhibit similar clause complexity, the lexical density of Example (1a) is much lower than that of Example (1b).

The central constituent of a clause is the verbal group that realizes the process. This verbal group may govern NGs that realize its participants and adverbial groups or prepositional phrases that realize its circumstances. Generally, the more participant NGs or circumstance adverbial groups a process verbal group governs, the more complex the clause is. Nominal group (NG) complexity can be assessed in two ways. The central constituent of an NG is the head noun (HN), and the remaining constituents that are governed by the HN function as modifiers. The greater the number of modifiers an HN has, the higher the NG complexity is. The other way to measure the NG complexity is to count the number of words in an NG since groups are composed of words. In Example (1b), for example, both the HNs shredding and departure have two modifiers: one premodifier, one postmodifier. Each premodifier consists of one single word, while each postmodifier consists of three words. Therefore, these two NGs are equivalent in complexity in terms of both the number of functional elements and word count.

Lexical density does not necessarily correlate with NG complexity. Lexical density may increase with either the addition of clausal constituents or the expansion of group constituents. For example, the lexical density of Example (2a) is 3, and that of Example (2b) is 4. Both too in Example (2a) and regular in Example (2b) function within groups, thereby increasing the complexity of the groups. However, only in Example (2b) functions within the clause, contributing to the increase of clause complexity.

| They fly too quickly. (Halliday and Hasan 1976: 4) |

| I only took the regular course. (Halliday and Hasan 1976: 61) |

The present study investigated the relationship among sentence complexity, clause complexity, and NG complexity in the Hallidayan sense in English academic writing, and compared the distributions of syntactic complexities at different linguistic levels across academic disciplines. According to Halliday (2004: 147), single-clause sentences contain “one huge nominal”, whereas “nominal groups are very simple” in highly intricate sentences. The hypotheses underlying the research reported in this paper are as follows: (1) Sentence complexity is a function of clause complexity, and clause complexity is a function of NG complexity. (2) Sentences are more complex in soft science texts, whereas NGs are more complex in hard science texts, and clause complexity is not discipline sensitive.

If hypothesis (1) is attested, we can expect more constituents per clause in single-clause sentences and longer NGs in clauses with a smaller number of constituents. If hypothesis (2) is attested, we can expect more multi-clause sentences but fewer single-clause sentences in soft sciences texts than in hard science texts.

4 Methodology

4.1 Corpus

The present study is based on a corpus comprising three groups of research article abstracts. The abstract is the summarization of the research, including such rhetorical moves as introduction, purpose, method, results, and conclusion (Hyland 2000). To summarize the whole article in a limited space, the article writer is impelled to compose a text with “maximum efficiency, clarity and economy” (Swales and Feak 2009: xiii). As noted by Biber and Gray (2011), noun phrases contribute significantly to the compressed style of writing commonly observed in abstracts. Gray (2015) pointed out that abstracts showed the densest use of phrasal features, which serve as a strong indicator of NG complexity (Gray 2013). On the other hand, full sentences are used in abstracts with no inserted non-linguistic information such as figures and tables. This is reliable for calculating the clause constituents.

Abstracts show different linguistic characteristics across disciplines (Hyland 2004). Abstracts in NS texts (e.g. medicine, physics, and computer science) tend to use passive voice, emphasizing research methods and results while avoiding subjectivity (Pho 2008). Abstracts in SS texts (e.g. linguistics, education and management) more frequently employ active voice, highlighting research background and significance (Lores 2004). Abstracts in Humanities texts often incorporate more evaluative language, emphasizing the theoretical contributions of the research (Hyland and Tse 2005). Given the varied organizational patterns of abstracts across disciplines, the linguistic resources that influence the syntactic complexity in the construction of academic texts may similarly vary according to the disciplinary norms.

The abstracts used in the present study were extracted from research articles published between 2017 and 2022. In selecting abstracts for this study, we primarily followed the fundamental classification of disciplines into hard and soft sciences as outlined by Biglan (1973). Recognizing that this broad categorization may oversimplify the linguistic characteristics of individual disciplines, we further subdivided soft sciences into Humanities and SS. This approach allowed us to form three major disciplinary groups, encompassing specifically six disciplines: Humanities (e.g. Literature and History), SS (e.g. Business and Politics), and NS (e.g. Physics and Biology). See Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the corpus.

| Disciplinary group | Journals | No. of abstracts | No. of words |

|---|---|---|---|

| SocialSci. | Journal of Accounting & Economics | 54 | 6,433 |

| Journal of Management | 78 | 14,115 | |

| Journal of Marketing | 68 | 12,261 | |

| International Organization | 102 | 17,766 | |

| Political Communication | 48 | 8,182 | |

| Sub-total | 350 | 58,757 | |

| Humanities | Cliometrica | 60 | 9,565 |

| Journal of Global History | 66 | 10,416 | |

| Memory Studies | 74 | 10,807 | |

| Journal of Literary Semantics | 18 | 2,842 | |

| Poetics Today | 61 | 11,139 | |

| Journal of World Literature | 71 | 10,038 | |

| Sub-total | 350 | 54,807 | |

| NaturalSci. | ACS Photonics | 63 | 10,696 |

| Nanophotonics | 68 | 11,114 | |

| Quantum | 69 | 10,822 | |

| Cell Host & Microbe | 61 | 8,721 | |

| Cell Metabolism | 52 | 7,391 | |

| Nature Microbiology | 37 | 6,868 | |

| Sub-total | 350 | 55,612 | |

| Total | 1,050 | 169,176 |

4.2 Measures and data collection

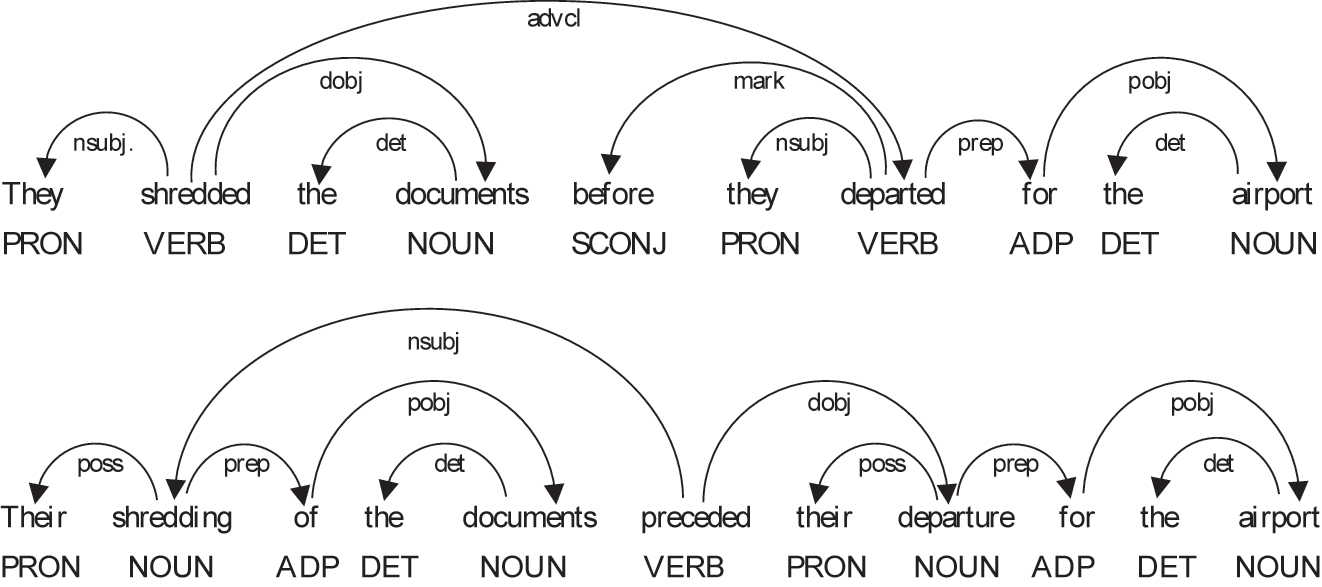

Dependency grammar describes the relationship between two words in a sentence, namely the governor and the dependent. This framework is valuable for uncovering linguistic features that may not be identifiable through traditional grammatical analyses (Kyle 2016). Hudson (1995, 2010) considered dependency analysis as a cognitive framework that can be quantified through dependency distance (DD). Since this binding operation is affected by the distance between two words, DD is considered closely related to syntactic complexity (Gibson 1998, 2000; Liu 2008) and serves as a measure of syntactic difficulty (Gao and He 2023; Hudson 1995; Jiang and Liu 2015). The longer the DD, the more difficult the syntactic analysis of a sentence (Jiang and Liu 2015; Liu et al. 2009). For example, the dependency structures of the two sentences in Example (1) can be visualized as Figure 1.

Dependency structures of Examples (1a) and (1b).

The mean DDs in Examples (1a) and (1b) are 1.77 and 1.6, respectively. Therefore, the syntactic complexity of Example (1a) is higher than that of Example (1b) in terms of mean DD. However, the DD-based analysis considers only the linear relationship between words in a sentence. A greater linear distance between the governor and the dependent indicates increased cognitive effort for the writer to establish the syntactic relationship between them.

Our rank-based analysis evaluates syntactic complexity at different linguistic levels. For example, the predicative verb shredded in Example (1a) functions as the root and governs another predicative verb departed. Accordingly, the sentence complexity of Example (1a) is 2. In contrast, the predicative verb preceded, which functions as the root in Example (1b), governs no other verbs, and so the sentence complexity of Example (1b) is 1. At the clause level, the process verbal group shredded in Example (1a) governs two participant NGs, while the process verbal group departed in Example (1b) governs one participant NG and one circumstance prepositional phrase. Consequently, the clause complexity of both Examples (1a) and (1b) is 3. The process verbal group preceded in Example (1b) governs two participant NGs, and hence the clause complexity of Example (1b) is also 3. However, the group complexities of the two clauses in Example (1a) are 1.33 and 1.67, respectively, while the clause complexity in Example (1b) is 3.67.

Oya (2013), in a study examining the mean DD across ten genres within a sub-corpus of the American National Corpus (ANC), found that journal articles typically exhibited the highest mean DD. Similarly, Wang and Liu (2017), using data from the British National Corpus (BNC), reported that although imaginative texts contained longer sentences with greater mean DDs, the overall mean DD of informative texts was higher than that of imaginative texts.

In the present study, we used a dependency treebank based on dependency grammar to count the root head verbs (HVs) as the number of sentences. We then extracted all the HVs that were governed by the root head verb (HV) in each sentence, and the two types of HVs together were considered as the number of clauses in the sentence. Similarly, the process verbal group in a clause and all the participant NGs and the circumstance adverbial groups or prepositional phrases governed by the process verbal group were taken as the number of constituents of this clause. We finally counted the DD between the HN of the participant NG and the first word of the NG, and the DD between the HN of the participant NG and the last word of the NG. The two sections added together were regarded as the complexity of NG in terms of the number of words. The HN and the number of pre- and post-modifier constituents governed by the HN can be regarded as the complexity of NG in terms of the number of functional elements. In the present study, we only investigated NG complexity in terms of the number of words.

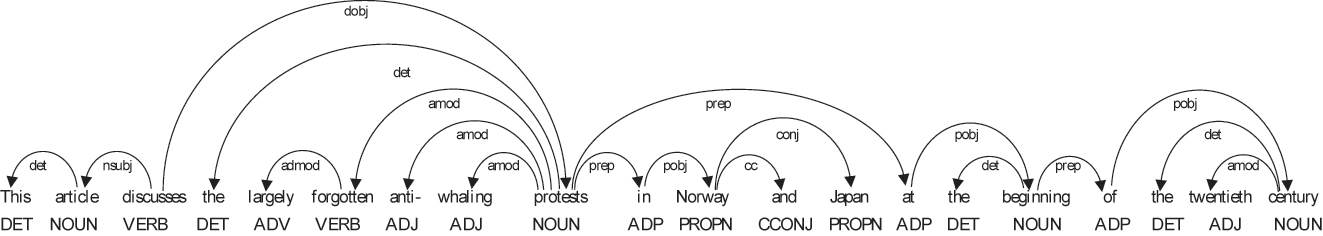

The spaCy (Honnibal and Montani 2019) was employed to examine the dependency relations within each sentence. See Example (3), and its dependency structure is shown in Figure 2.

Dependency structures of Example (3).

| This article discusses the largely forgotten anti-whaling protests in Norway and Japan at the beginning of the twentieth century. (Humanities) |

The sentence in Example (3) consists of one clause, and hence the complexity of this sentence is 1. This clause consists of three constituents, the root HV discusses governing two participant NGs, and hence the complexity of this clause is 3. Since we were discussing the relationship between clause complexity and NG complexity, we only counted the lengths of participant NGs. In Example (3), the DD between the HN article and the determiner this in the subject NG is 1, and hence the complexity of this NG is 2. The object NG is relatively complicated. The DD between the object HN protests and the first word the of the NG is 5, and that between this HN and the last word century is 11. The HN, combined with the five preceding and eleven following words, results in a 17-word NG. Thus, the complexity of this NG is 17. The average NG complexity in this clause is therefore 9.5.

In total, we collected 6,721 sentences, consisting of 13,815 clauses, which further consist of 39,435 clausal constituents. See Table 2.

Data collected from the corpus.

| SocialSci. | Humanities | NaturalSci. | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sentences | 2,414 | 1,981 | 2,326 | 6,721 | |

| Clauses | 5,418 | 4,074 | 4,323 | 13,815 | |

| Clausal constituents | Processes | 5,418 | 4,074 | 4,323 | 13,815 |

| Participants | 6,524 | 4,622 | 5,215 | 16,361 | |

| Circumstances | 3,352 | 2,889 | 3,018 | 9,259 | |

4.3 Data analysis

We first examined the regularity of the distributions of the data and compared the distributional patterns across the three disciplinary groups by performing Binomial distribution regression analyses using Altmann Fitter. In the present study, we employed the Negative Binomial, Hyperbinomial, and Extended Positive Binomial distribution models for the analyses. The formulas for these three Binomial distribution models are presented below:

where parameters k and p represent the dispersion degree and the success probability, respectively. A larger k value indicates a more concentrated distribution pattern with less dispersion, while a higher p value indicates a high success probability.

where parameter n represents the largest observed number of constituents per construct. Parameter m is the baseline probability, which determines the overall position of the distribution. Parameter q is a correlation parameter: When q = 0, the numbers are independent, whereas when q > 0, there is a clustering effect among the numbers.

where Z(n, p, α) is a normalization constant that ensures that the sum of all probabilities equals 1. Parameter n denotes the largest observed number of constituents per construct, while parameters p and α are the baseline probability and the exponential adjustment parameter, respectively.

We investigated the interrelationship between construction complexity and constituent complexity using the Menzerath-Altmann Law (Altmann 1980). This linguistic principle describes a general inverse relationship between the size of a linguistic construct and the size of its components. The relationship is mathematically modeled by the following formula:

where variable x represents the size of the whole unit, and y represents the average size of the subunits.

This function integrates a power-law and an exponential decay. When x is small, the power function y = ax b predominates, which controls the initial growth or decay rate of the function. As x increases, the exponential function takes over, which causes the function to rapidly decay and approach zero. Parameter a in the function is a scaling constant that determines the initial value or height of the curve on the y-axis. Parameter b influences the initial rate of growth or decay. If b > 0, the curve initially stretches upward rapidly as x increases. A larger b results in a faster decrease in y as x increases. Conversely, if b < 0, the curve decreases rapidly as x grows. If b = 0, the function becomes a pure exponential decay y = ae−cx. Parameter c controls the rate of exponential decay. A larger c indicates a faster decay, while a smaller c indicates a slower decay.

Statistical tests were conducted in SPSS 29 to compare the frequencies of data across different disciplinary groups and assess the significance of observed differences. We first performed normality tests on each dataset. For data that met the normality assumption, we applied the t-test. If the variances of the two groups of data were unequal, the Welch’s t-test was utilized. For data that did not meet normality, the Kruskal-Wallis H test was employed. Differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

Additionally, we employed the Chi-squared test in SPSS 29 to examine the distributions of data across disciplinary groups and to assess whether the differences were statistically significant. A significant difference between the variables was indicated if the χ2 value exceeded the critical threshold or if p < 0.05.

5 Results

5.1 Sentence complexities across disciplinary groups

Based on the data shown in Table 2, the average number of clauses per sentence is 2.24 in SS texts, 2.06 in Humanities texts, and 1.86 in NS texts. The Shapiro-Wilk test revealed that the number of clauses per sentence in all the three groups significantly deviated from a normal distribution (p < 0.001). Therefore, we employed the Kruskal-Wallis H test as the primary analytical method. This test revealed a significant difference among the disciplinary groups (H = 126.813, df = 2; p < 0.001). Post-hoc pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni adjustment demonstrated that all pairwise differences were statistically significant (p < 0.001).

To verify the robustness of this finding, we also conducted a Welch ANOVA, which is insensitive to violations of homogeneity of variances. The results corroborated the initial finding, showing a significant difference among the disciplinary groups (Welch’s F = 74.792, df1 = 2, df2 = 4,333.668, p < 0.001). In conclusion, SS texts exhibited the highest sentence complexity, significantly greater than that of Humanities texts, which in turn were significantly more complex than NS texts.

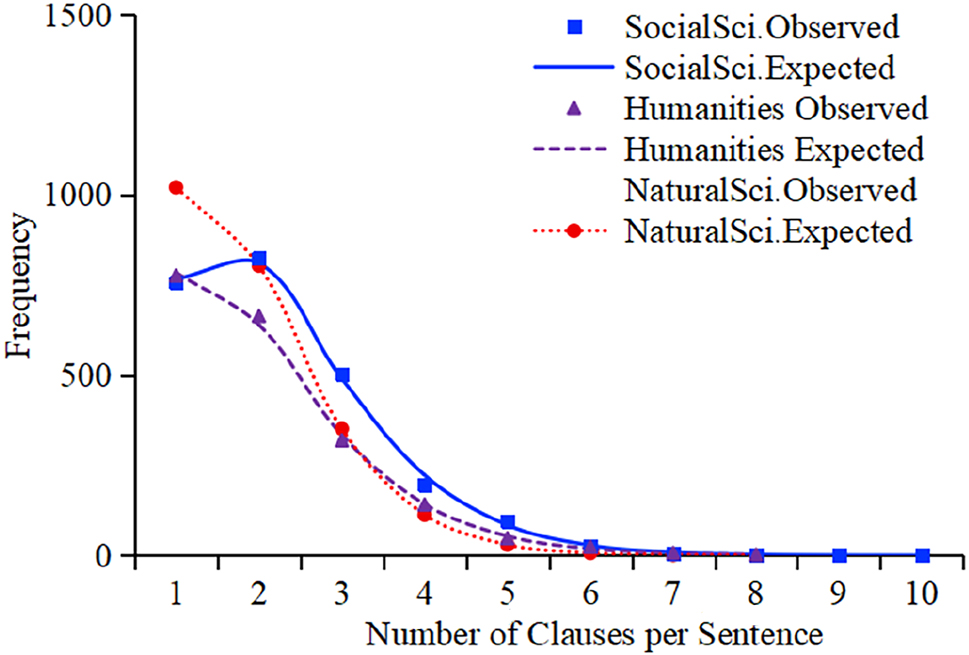

The lower average number of clauses per sentence in NS texts aligns with our expectation that there are relatively more single-clause sentences in NS texts than in the other two disciplinary groups. Table 3 and Figure 3 illustrate the distribution of the clause counts per sentence, and the results of the Negative Binomial distribution analyses are shown in Table 4.

Observed and Negative Binomial expected frequencies of clauses per sentence across three disciplinary groups.

| SocialSci. | Humanities | NaturalSci. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed | Expected | Observed | Expected | Observed | Expected | |

| 1 | 758 | 765.91 | 776 | 783.88 | 1,009 | 1,020.42 |

| 2 | 824 | 810.69 | 664 | 639.55 | 827 | 803.16 |

| 3 | 503 | 490.57 | 319 | 334.43 | 353 | 351.45 |

| 4 | 197 | 222.72 | 141 | 142.21 | 100 | 112.85 |

| 5 | 96 | 84.29 | 48 | 53.53 | 26 | 29.66 |

| 6 | 25 | 28.08 | 24 | 18.58 | 7 | 6.76 |

| 7 | 6 | 8.51 | 7 | 6.09 | 3 | 1.38 |

| 8 | 3 | 2.39 | 2 | 2.73 | 1 | 0.31 |

| 9 | 1 | 0.63 | – | – | – | – |

| 10 | 1 | 0.21 | – | – | – | – |

Negative Binomial fits for the number of clauses per sentence.

Parameters and goodness-of-fit results of Negative Binomial distribution for the number of clauses per sentence.

| Disciplinary group | Size | μ | k | p | Variance | R 2 | C | χ 2 | DF | P(χ2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SocialSci. | 2,414 | 2.244 | 6.973 | 0.848 | 1.467 | 0.999 | 0.003 | 7.248 | 5 | 0.203 |

| Humanities | 1,981 | 2.057 | 3.548 | 0.770 | 1.371 | 0.999 | 0.002 | 4.218 | 5 | 0.516 |

| NaturalSci. | 2,326 | 1.859 | 8.936 | 0.912 | 0.934 | 0.999 | 0.003 | 5.889 | 4 | 0.208 |

Table 3 and Figure 3 show that the data from all the three disciplinary groups exhibit a typical positive skew (right-skewed distribution). This indicates that the majority of sentences contain a relatively low number of clauses, concentrated on the left side of the distribution (1–3 clauses per sentence), while only a small number of sentences possess a large number of clauses, resulting in a long tail extending to the right.

Table 4 shows that all the three groups of data exhibit excellent fits to the Negative Binomial model (R2 > 0.998), demonstrating consistent statistical patterns in sentence structure across disciplinary groups. The smallest k value in Humanities texts (k = 3.548) indicates that the distribution of the numbers of clauses per sentence has the highest degree of dispersion and is the most heterogeneous in Humanities texts. This indicates that Humanities texts exhibit the greatest variability in sentence complexity, containing both a large number of single-clause sentences and a considerable proportion of complex sentences as well. The k values for both SS texts (k = 6.973) and NS texts (k = 8.936) are relatively large and similar in magnitude. This indicates that the distributions of the number of clauses per sentence in these two disciplinary groups are more concentrated and uniform compared to the Humanities group. In particular, the sentence lengths in NS texts are the most regular and exhibit the least fluctuation. The analysis reveals a clear complexity gradient: SS texts have the most complex sentences with medium dispersion, Humanities texts display moderate complexity sentences but the highest structural variation, indicating more flexible styles, while NS texts present the simplest structure with high regularity, typical of academic writing.

5.2 Clause complexities across disciplinary groups

Drawing on the above research on sentence complexity, which suggests that the number of clauses per sentence is the largest in SS texts and the smallest in NS texts, we could anticipate the largest number of clausal constituents in NS texts.

As shown in Table 2, we collected 39,435 clausal constituents from the corpus. The average number of constituents per clause is 2.82 in SS texts, 2.84 in Humanities texts and 2.91 in NS texts. The Shapiro-Wilk test revealed that the number of clauses per sentence for all the three groups significantly deviated from a normal distribution (p < 0.001). Therefore, we employed the Kruskal-Wallis H test as the primary analytical method. The test revealed a significant difference among the three disciplinary groups (H = 15.325, df = 2; p < 0.001). Post-hoc analysis with Bonferroni adjustment revealed that the difference between SS texts and Humanities texts was not significant (p = 1.000). However, the constituent numbers per clause in both SS texts and Humanities texts were significantly lower than those in NS texts (p < 0.001; p = 0.017 < 0.05). Therefore, SS texts and Humanities texts were statistically comparable in terms of the number of clausal constituents, and both were significantly lower than NS texts.

To verify the robustness of this finding, a Welch ANOVA was also conducted. The results corroborated the initial finding, showing a significant difference among the disciplinary groups (Welch’s F = 8.511, df1 = 2, df2 = 8,843.734, p < 0.001). Post-hoc analysis with LSD also showed significant differences between SS texts and NS texts (p < 0.001) and between Humanities texts and NS texts (p = 0.005 < 0.05), whereas no significant difference was found between SS texts and Humanities texts (p = 0.312 > 0.05). In conclusion, clauses in NS texts were more complex than those in SS and Humanities texts, consistent with our expectation that clauses would exhibit the highest level of complexity in NS texts.

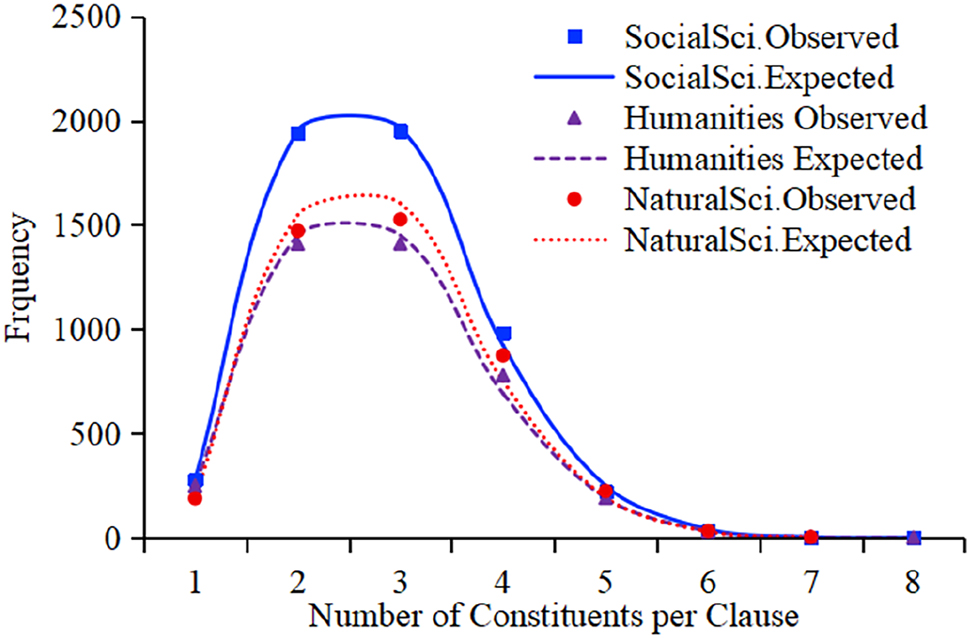

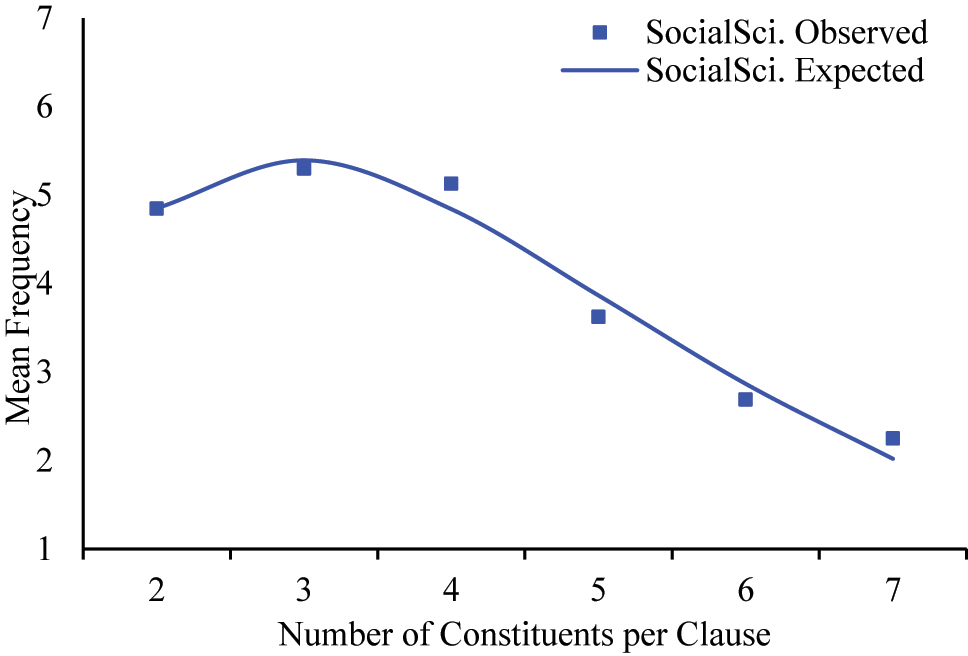

Next, we compared the distributions of the number of constituents per clause in the three disciplinary groups. The Hyperbinomial distribution model was used to fit the data in SS and Humanities texts. See Table 5 and Figure 4, and the results of the goodness-of-fit test are presented in Table 6.

Observed and Hyperbinomial expected frequencies of constituents per clause across three disciplinary groups.

| SocialSci. | Humanities | NaturalSci. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed | Expected | Observed | Expected | Observed | Expected | |

| 1 | 281 | 282.79 | 249 | 255.97 | 189 | 189.00 |

| 2 | 1,941 | 1,953.39 | 1,410 | 1,449.47 | 1,472 | 1,493.02 |

| 3 | 1,952 | 1,964.46 | 1,411 | 1,450.50 | 1,526 | 1,519.91 |

| 4 | 985 | 923.52 | 778 | 691.96 | 875 | 825.21 |

| 5 | 223 | 248.72 | 191 | 190.52 | 224 | 252.02 |

| 6 | 33 | 40.83 | 30 | 32.10 | 34 | 41.05 |

| 7 | 2 | 4.06 | 4 | 3.28 | 3 | 2.79 |

| 8 | 1 | 0.23 | 1 | 0.19 | – | – |

Hyperbinomial fits for the number of constituents per clause.

Parameters and goodness-of-fit results of Hyperbinomial distribution for the number of constituents per clause.

| Disciplinary group | Size | μ | m | q | Variance | R 2 | C | χ 2 | DF | P(χ2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SocialSci. | 15,294 | 2.823 | 0.200 | 0.172 | 0.946 | 0.999 | 0.0016 | 8.809 | 3 | 0.0319 |

| Humanities | 11,585 | 2.844 | 0.253 | 0.179 | 1.033 | 0.996 | 0.0034 | 13.850 | 3 | 0.0031 |

| NaturalSci. | 12,556 | 2.905 | 0.184 | 0.205 | 0.998 | 0.990 | 0.0080 | 34.717 | 3 | 0.0000 |

It can be seen from Table 6 that the three groups of data exhibit significant differences in clause complexity. SS texts demonstrate the most concentrated distribution pattern of clause constituents (Variance = 0.946) and the lowest mean value (2.82), indicating highly standardized clause structures and formalized expressions. Humanities texts display the greatest variability and diversity in clause composition (Variance = 1.033). The relatively lower goodness-of-fit (P(χ2) = 0.0031) suggested flexible and dynamic structures.

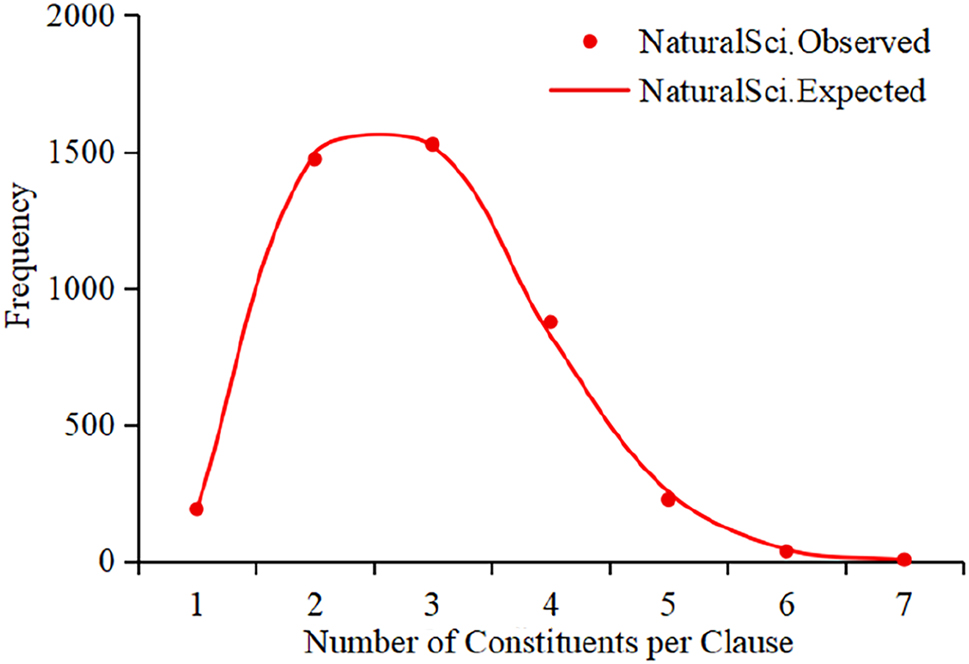

However, the Hyperbinomial distribution model did not adequately fit the data for NS texts (P(χ2) = 0.000). Therefore, we fitted the NS data using the Extended Positive Binomial distribution model. See Figure 5 and Table 7.

Extended Positive Binomial fits for the number of constituents per clause in NS texts.

Parameters and goodness-of-fit results of Extended Positive Binomial distribution for the number of constituents per clause in NS texts.

| Disciplinary group | Size | μ | p | a | Variance | R 2 | C | χ 2 | DF | P(χ2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NaturalSci. | 12,556 | 2.905 | 0.298 | 0.956 | 0.998 | 0.999 | 0.0018 | 7.667 | 3 | 0.0534 |

Figure 5 and Table 7 show that the Extended Positive Binomial model provided an excellent fit, indicating an underlying structure distinct from the other two disciplinary groups. Generally, NS texts exhibit a distinctive pattern characterized by a high mean value and a simple distribution model. Further analysis revealed significantly fewer single-constituent clauses with concentrated frequency in medium-complexity clauses containing 2 to 4 constituents. This central distribution pattern supports high information density while maintaining syntactic clarity, reflecting the rhetorical paradigm of NS writing, which prioritizes precision, conciseness, and replicability.

This comparative analysis effectively elucidates the distinctive characteristics across the three disciplinary groups, particularly resolving the apparent paradox of NS texts exhibiting the highest complexity despite their simpler distribution model.

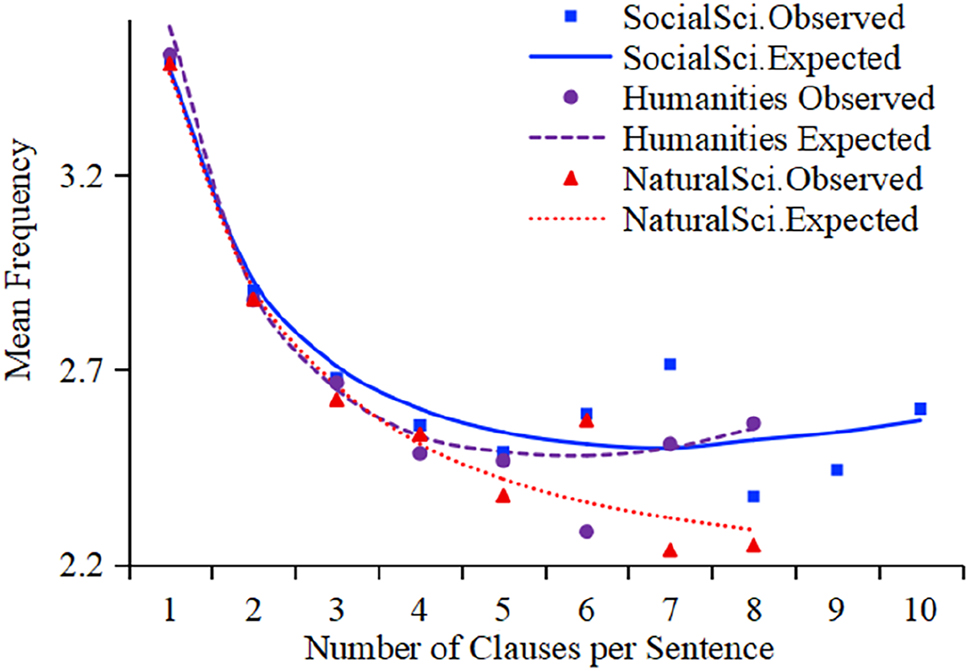

However, this conclusion may not be fully reliable due to the functional relationship between sentence complexity and clause complexity. Therefore, we further investigated the relationship between the number of clauses in a sentence and the mean number of constituents per clause within that sentence. Based on the preceding cross-disciplinary analyses, we could expect the most complex clauses to appear in NS texts. See Table 8 and Figure 6, and the results of the nonlinear regression analysis using the Menzerath-Altmann Law are presented in Table 9.

Observed and Menthrath-Altmann Law expected frequencies of the mean number of constituents per clause in a sentence across three disciplinary groups.

| SocialSci. | Humanities | NaturalSci. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed | Expected | Observed | Expected | Observed | Expected | |

| 1 | 3.496 | 3.47 | 3.509 | 3.58 | 3.485 | 3.46 |

| 2 | 2.903 | 2.93 | 2.879 | 2.90 | 2.881 | 2.91 |

| 3 | 2.679 | 2.71 | 2.667 | 2.65 | 2.623 | 2.66 |

| 4 | 2.558 | 2.60 | 2.486 | 2.53 | 2.535 | 2.51 |

| 5 | 2.490 | 2.54 | 2.467 | 2.49 | 2.377 | 2.42 |

| 6 | 2.587 | 2.51 | 2.285 | 2.48 | 2.571 | 2.36 |

| 7 | 2.714 | 2.50 | 2.510 | 2.50 | 2.238 | 2.32 |

| 8 | 2.375 | 2.52 | 2.563 | 2.55 | 2.250 | 2.29 |

| 9 | 2.444 | 2.54 | – | – | – | – |

| 10 | 2.600 | 2.57 | – | – | – | – |

Menthrath-Altmann Law fits for the mean number of constituents per clause in a sentence.

Parameters and goodness-of-fit results of the Menthrath-Altmann Law for the number of constituents per clause.

| Disciplinary group | a | b | c | Adjusted R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SS | 3.318 | −0.310 | −0.046 | 0.906 |

| Humanities | 3.328 | −0.405 | −0.072 | 0.966 |

| NS | 3.374 | −0.287 | −0.026 | 0.950 |

Although the value of parameter a is slightly larger in NS texts compared with the other two groups of texts, the starting frequency is the smallest (3.462) in NS texts. The lowest absolute values of parameters b and c in NS texts indicate that the number of constituents per clause decreases the most slowly when the number of constituents per clause is small and increases the most slowly when the number is large. The highest absolute values of parameters b and c in Humanities texts imply that, for less complex sentences, the number of clausal constituents decreases the fastest in Humanities texts, and for more complex sentences, it increases the fastest. This means that when the sentence structure becomes more complex (i.e. the number of clauses increases), the internal structure of each clause is significantly simplified.

These findings suggest that the number of constituents per clause is the largest in Humanities texts while the smallest in NS texts. This result does not support our expectation that the clauses are the most complex in NS texts. The reason for the largest average number of constituents per clause in NS texts achieved from the above research is that there are more single-clause sentences in NS texts and single-clause sentences have a relatively larger number of constituents per clause. Taking sentence complexity into consideration, we concluded that clauses were also the least complex in NS texts. This means that the syntactic structure within Humanities texts exhibited the most significant dynamic tension, while that of NS texts demonstrated the highest degree of stability.

5.3 NG complexities across disciplinary groups

The study in the previous section conforms to our hypothesis that the sentence complexity is a function of clause complexity in terms of the number of constituents, but this relationship does not show obvious differences across the three disciplinary groups. However, the non-significant difference between the numbers of clausal constituents across disciplinary groups does not necessarily mean non-significant differences between the complexities of the constituents. In this section, we investigated the complexity of clausal constituents across the three disciplinary groups.

According to the Mentherath-Altmann Law, the clause length is a function of the average length of the clausal constituents. Since a clause may consist of participant NGs, process verbal groups and circumstance adverbial groups or prepositional phrases, the length of any clausal constituent is potentially a function of the clause length. Therefore, in the present study, we focused only on the complexity of participant NGs, as complex NGs are a distinctive feature of academic language. We hereby could anticipate the most complex NGs in NS texts among the three disciplinary groups.

As shown in Table 2, we collected 16,361 participant NGs in total from the three disciplinary groups. The mean length of NGs is the largest in Humanities texts (6.16) while the smallest in SS texts (5.01), with that in NS texts (5.98) in between. The Shapiro-Wilk and Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests indicated that the distributions of the numbers of words per NG in SS texts (D = 0.190, df = 6.524, p < 0.001), Humanities texts (W = 0.794, df = 4.622, p < 0.001), and NS texts (D = 0.145, df = 5,215, p < 0.001) all significantly deviated from normality. Consequently, the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis H test revealed a significant difference between the disciplinary groups (H = 209.149, df = 2; p < 0.001). Post-hoc pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni adjustment demonstrated that all pairwise differences were statistically significant (p < 0.001). NS texts exhibited the highest NG complexity, significantly higher than humanities texts, which in turn were significantly more complex than SS texts. This aligns with our expectation that the average length of NGs is the largest in NS texts.

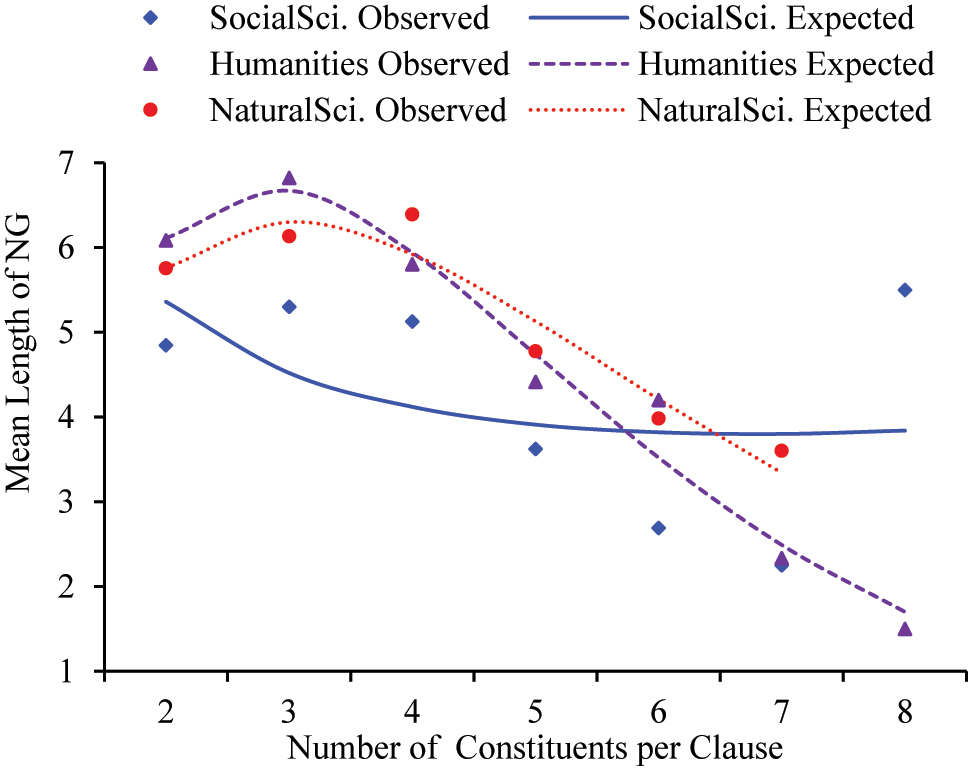

The reason for the relatively smaller average NG length in NS texts than in Humanities texts could be related to clause complexity. We then compared the average NG lengths in different lengths of clauses across the three disciplinary groups. See Table 10 and Figure 7, and the results of the non-linear regression analysis using the Menthrath-Altmann Law are shown in Table 11.

Observed and Menthrath-Altmann Law expected lengths of participant NGs per clause across three disciplinary groups.

| SocialSci. | Humanities | NaturalSci. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed | Expected | Observed | Expected | Observed | Expected | |

| 2 | 4.847 | 5.36 | 6.084 | 6.11 | 5.756 | 5.76 |

| 3 | 5.300 | 4.52 | 6.822 | 6.67 | 6.133 | 6.30 |

| 4 | 5.127 | 4.12 | 5.800 | 5.94 | 6.392 | 5.92 |

| 5 | 3.624 | 3.91 | 4.413 | 4.74 | 4.775 | 5.13 |

| 6 | 2.689 | 3.82 | 4.200 | 3.52 | 3.983 | 4.21 |

| 7 | 2.250 | 3.80 | 2.333 | 2.49 | 3.600 | 3.34 |

| 8 | 5.500 | 3.84 | 1.500 | 1.70 | – | – |

Menthrath-Altmann Law fits for the mean length of NGs per clause.

Parameters and goodness-of-fit results of Menthrath-Altmann Law for the length of NGs per clause.

| Disciplinary group | a | b | c | Adjusted R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SS | 6.980 | −0.661 | −0.097 | 0.203 |

| Humanities | 6.289 | 1.722 | 0.611 | 0.971 |

| NS | 5.593 | 1.285 | 0.431 | 0.927 |

It can be seen that all the data in Humanities texts and in NS texts fit the Menthrath-Altmann Law well. The larger b value in Humanities texts indicates that the length of NGs increases more rapidly to the peak point when the number of clausal constituents is smaller. The larger c value in Humanities texts indicates that the length of NGs decays more rapidly when the number of clausal constituents is larger. That is, the relatively smaller c value in NS texts indicates that the mean length of NGs in NS texts remains higher with the increase of the number of clausal constituents.

The data in SS texts, however, does not fit well. This inconsistency might be due to the extreme outlier in the clause with eight clausal constituents. See Example (4):

| However, quantitative researchers of conflict have long relegated the study of sex and gender inequality as a cause of war to a specialized group of scholars, despite overwhelming evidence that the connections are profound and consequential. (SS_1775) |

The HV relegated in Example (4) governs two participant NGs, two circumstance adverbial groups, and three circumstance prepositional phrases, totaling eight clausal constituents. The subject NG, quantitative researchers of conflict, consists of four words and the object NG, the study of sex and gender inequality, consists of seven words, respectively, resulting in the mean NG length of 5.5 in the eight-constituent clause. With this outlier excluded, the data in SS texts fit the Menzerath-Altmann Law well (a = 4.860, b = 1.815, c = 0.630, R2 = 0.973). See Figure 8:

Menthrath-Altmann Law fits for the mean length of NGs per clause in SS texts.

This aligns with our hypothesis that the distributions of the three groups of data conform to the Menzerath-Altmann Law. We concluded from the above analysis that, although the mean length of the NGs in Humanities texts was slightly longer than those in NS texts, the NGs in the more complex clauses were comparatively longer in NS texts than in the other two disciplinary groups.

6 Discussion

We investigated syntactic complexity at the sentence, clause and group levels based on the rank-scale hypothesis proposed by Halliday (1961). The findings include: (1) the sentences are the least complex in NS texts while the most complex in SS texts but with medium dispersion, and Humanities texts display moderately complex sentences with the highest structural variation; (2) clauses are the most complex in Humanities texts while the least complex in NS texts although the average number of constituents per clause is the largest in NS texts; (3) NGs are the most complex in NS texts although the mean length of the NGs is slightly larger in Humanities texts than in NS texts. These findings generally support our hypothesis that the number of clausal constituents is a function of the number of clauses within a sentence and the mean length of NGs is a function of the number of clausal constituents within a clause. However, the findings do not always support our hypothesis regarding discipline distributions.

Single-clause sentences dominate in NS texts. As data shows, the number of constituents in a single-clause sentence is larger than the average number of constituents per clause in a multi-clause sentence. The reason for the largest average number of clausal constituents in NS texts is the largest number of single-clause sentences. A single-clause sentence always requires an explicit subject, but not all secondary clauses require explicit subjects. This might have resulted in the increase of the average number of clausal constituents in NS texts. For example:

| The advanced dynamic addressability could fuel relevant applications beyond proof-of-concept demonstrations. (NS_8) |

| The article illustrates how a social movement against social injustices and inequalities enacted and engaged with decolonial repertoires of action. (Humanities_13) |

The single-clause sentence in Example (5a) consists of three constituents, i.e. one verbal group and two participant NGs, and the number of constituents per clause is 3. The sentence in Example (5b) is a clause complex of projection in the Hallidayan sense (Halliday 1994), consisting of three verbal groups, two participant NGs and two circumstance prepositional phrases, and hence the average number of constituents per clause is 2.33. This aligns with previous research on syntactic complexity in academic writing (e.g. Gardner et al. 2019; He and Yang 2018; He and Zhang 2024), which suggests that Humanities texts are characterized by complex sentence structures while NS texts are marked by simple clauses.

Based on the data shown in Table 2, the average number of participant NGs is 1.204 in SS texts, 1.135 in Humanities texts and 1.206 in NS texts. The reason for the relatively larger number of participant NGs in SS texts might be that there are many finite secondary clauses with explicit subjects in SS texts, and the reason for the relatively smaller number of participant NGs in Humanities texts might be that there are many finite or non-finite secondary clauses without explicit subjects. For example:

| Suspicion of activist arguments weakens the impact on attitudes and voting; industry argument suspicion has limited impact, though it does increase the likelihood of voter switching. (SS_168) |

| Beyond displaying the intricate relationship between future and past in collective memory, the case highlights how this operation only works to further neglect the racism and unresolved pasts entrenched in the myth of exceptionalism that motivated the Capitol Riot. (Humanities_41) |

There are three finite clauses in Example (6a), each containing two participant NGs. There are also three clauses in Example (6b), two finite and one non-finite, containing three participant NGs and four circumstances. The larger number of circumstances in Example (6b) can also explain the reason for the largest average number of constituents per clause in Humanities texts among the three disciplinary groups. We can see from the data shown in Table 2 that the average number of circumstances per clause is the largest in Humanities texts (0.709), but the smallest in SS texts (0.619), with that in NS texts (0.698) in between.

The NG complexity in Humanities texts and in NS texts supports our hypothesis that the mean length of NGs in a clause is a function of the number of clausal constituents in that clause, but that in SS texts does not support our hypothesis. As Example (3) shows, the number of circumstances influences the pattern of the mean length of the NGs. There are a total of five circumstances in the single-clause sentence in Example (7). This is inconsistent with the smallest average number of circumstances in SS texts.

Another factor that may have an influence on the length of NGs is that the HN of an NG may have premodifiers and/or postmodifiers. A premodifier is realized as a word or word complex, and a postmodifier is realized as a phrase or a clause. A phrase or a clause modifying an HN in an NG is the rank-shift use (Halliday 1961). A postmodifier phrase or clause has its own syntactic structure. They contribute to the phrasal features and clausal features, respectively (Biber and Conrad 2009; Biber and Gray 2010, 2016). The phrasal features are not directly related to phrase complexity, nor are the clausal features directly related to clause complexity.

Therefore, it is inappropriate to take the number of words in an NG as the NG complexity, and the NG complexity should better be measured by the number of premodifier words. Excluding the postmodifiers, the mean lengths of the NGs are 2.01 in SS texts, 2.12 in Humanities texts, and 2.24 in NS texts. The Shapiro-Wilk and Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests indicated that the distributions of the numbers of words per NG in SS texts (D = 0.237, df = 6,524, p < 0.001), Humanities texts (W = 0.853, df = 4,622, p < 0.001) and NS texts (D = 0.221, df = 5.215, p < 0.001) all significantly deviated from normality. Non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis H test revealed a significant difference between the disciplinary groups (H = 187.447, df = 2; p < 0.001). Post-hoc pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni adjustment demonstrated that all pairwise differences were statistically significant (p < 0.001). NS texts exhibited the highest NG complexity, significantly higher than humanities texts, which in turn were significantly more complex than SS texts. This aligns with our expectation that the average length of NGs excluding the postmodifiers of the HNs is the largest in NS texts.

7 Conclusions

This study investigated syntactic complexity across different disciplinary groups of academic writing. Based on the rank-scale hypothesis, we hypothesized that the number of clauses per sentence is a function of the number of groups or phrases per clause, and the number of groups or phrases per clause is a function of the number of words per group. We further hypothesized that sentences are more complex in soft science texts, whereas NGs are more complex in hard science texts. To test these hypotheses, we measured linguistic complexity using a dependency treebank in dependency grammar. Clause counts were determined by identifying the root verb of each sentence and all verbs governed by the root verb, while group counts were determined by the clausal constituents governed by the process verbal group of each clause.

The corpus-based study shows that sentences are the least complex in NS texts, while the most complex in Humanities texts, clauses are also the least complex in NS texts, although the average number of constituents per clause is the largest in NS texts, and NGs are the most complex in NS texts. The reason for the inconsistency between the average number of clausal constituents and the clause complexity is that single-clause sentences dominate in NS texts, and sentences with a larger number of clauses tend to have more clausal constituents in soft science texts. Research also shows that NG complexity can be better measured by the number of premodifiers of the HN. This is because premodifiers are realized as words that function within the NGs, and postmodifiers are the rank-shift use of prepositional phrases or clauses which have their own clausal structures and function to increase the complexity at the clause level.

The findings of this study have important implications for discipline-specific English academic writing instruction. They underscore the necessity of prioritizing NG compression in writing NS texts, while emphasizing clausal elaboration in writing SS and Humanities texts. Consequently, English academic writing pedagogy should equip writers with the skills to strike a discipline-appropriate equilibrium between linguistic complexity and readability. A scaffolded instructional sequence is proposed, commencing with exercises that target clausal expansion, progressing to the integration of noun modifiers, and culminating in the use of nominalization to realize a shift from clauses to condensed NGs. This sequenced strategy supports the development of a sophisticated academic style by guiding students from a reliance on clausal complexity toward the mastery of NG complexity.

However, this study is constrained by the specific corpus, which may lack representativeness, and the results might not be fully applicable to other contexts. Furthermore, this study takes construct length as a measure of linguistic complexity, without considering construct diversity or construct types. Future research could incorporate these aspects to provide a comprehensive picture of linguistic complexity, for example, to investigate different types of participant NGs and their modifier preferences at the group level, different types of process verbal groups at the clause level, and different interdependent or logico-semantic relationships between clauses at the sentence level.

Award Identifier / Grant number: 24&ZD250

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Conflict of interest: The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: This work was supported by the Major Program of the National Fund of Philosophy and Social Science of China (grant number 24&ZD250).

-

Data availability: The author confirms that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

References

Altmann, Gabriel. 1980. Prolegomena to Menzerath’s law. Glottometrika 2(2). 1–10.Search in Google Scholar

Atkinson, Dwight. 1999. Scientific discourse in sociohistorical context: The philosophical transactions of the royal society of London, 1675–1975. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.Search in Google Scholar

Bardovi-Harlig, Kathleen. 1992. A second look at T-unit analysis: Reconsidering the sentence. TESOL Quarterly 26. 390–395. https://doi.org/10.2307/3587016.Search in Google Scholar

Becher, Tony & Paul R. Trowler. 2001. Academic tribes and territories: Intellectual enquiry and the cultures of disciplines, 2nd edn. Buckingham: The Society for Research into Higher Education & Open University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Biber, Douglas. 2006. University language: A corpus-based study of spoken and written registers. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/scl.23Search in Google Scholar

Biber, Douglas & Victoria Clark. 2002. Historical shifts in modification patterns with complex noun phrase structures. In Teresa Fanego, Javier Pérez-Guerra & María José López-Couso (eds.), English historical syntax and morphology, 43–66. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.Search in Google Scholar

Biber, Douglas & Susan Conrad. 2009. Register, genre, and style. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511814358Search in Google Scholar

Biber, Douglas & Edward Finegan. 2001. Diachronic relations among speech-based and written registers in English. In Susan Conrad & Douglas Biber (eds.), Variation in English: Multi-dimensional studies, 66–83. London: Longman.Search in Google Scholar

Biber, Douglas & Bethany Gray. 2010. Challenging stereotypes about academic writing: Complexity, elaboration, explicitness. Journal of English for Academic Purposes 9. 2–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2010.01.001.Search in Google Scholar

Biber, Douglas & Bethany Gray. 2011. Grammatical change in the noun phrase: The influence of written language use. English Language and Linguistics 15(2). 223–250. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1360674311000025.Search in Google Scholar

Biber, Douglas & Bethany Gray. 2016. Grammatical complexity in academic writing: Linguistic change in writing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511920776Search in Google Scholar

Biber, Douglas, Bethany Gray & Kornwipa Poonpon. 2011. Should we use characteristics of conversation to measure grammatical complexity in L2 writing development? TESOL Quarterly 45(1). 5–35. https://doi.org/10.5054/tq.2011.244483.Search in Google Scholar

Biber, Douglas, Bethany Gray & Shelley Staples. 2016. Predicting patterns of grammatical complexity across textual task types and proficiency levels. Applied Linguistics 37. 639–668. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amu059.Search in Google Scholar

Biglan, Anthony. 1973. The characteristics of subject matter in different academic areas. Journal of Applied Psychology 57. 195–203. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0034701.Search in Google Scholar

Casal, J. Elliott & Joseph J. Lee. 2019. Syntactic complexity and writing quality in assessed first-year L2 writing. Journal of Second Language Writing 44. 51–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2019.03.005.Search in Google Scholar

Casal, J. Elliott, Xiaofei Lu, Xixin Qiu, Yuanheng Wang & Genggeng Zhang. 2021. Syntactic complexity across academic research article part-genres: A cross-disciplinary perspective. Journal of English for Academic Purposes 52. 100996. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2021.100996.Search in Google Scholar

de Haan, Pieter. 1989. Postmodifying clauses in the English noun phrase: A corpus-based study. Amsterdam: Rodopi.10.1163/9789401207768Search in Google Scholar

Dong, Jihua, Hao Wang & Buckingham Louisa. 2023. Mapping out the disciplinary variation of syntactic complexity in student academic writing. System 113. 102974. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2022.102974.Search in Google Scholar

Fang, Zhihui, Mary J. Schleppergrell & Beverly E. Cox. 2006. Understanding the language demands of schooling: Nouns in academic registers. Journal of Literacy Research 38. 247–273. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15548430jlr3803_1.Search in Google Scholar

Gao, Nan & Qingshun He. 2023. A corpus-based study of the dependency distance differences in English academic writing. Sage Open 13(3). 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440231198408.Search in Google Scholar

Gardner, Sheena, Hilary Nesi & Biber Douglas. 2019. Discipline, level, genre: Integrating situational perspectives in a new MD analysis of university student writing. Applied Linguistics 40(4). 646–674. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amy005.Search in Google Scholar

Gibson, Edward. 1998. Linguistic complexity: Locality of syntactic dependencies. Cognition 68. 1–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0010-0277(98)00034-1.Search in Google Scholar

Gibson, Edward. 2000. The dependency locality theory: A distance-based theory of linguistic complexity. In Alec Marantz, Yasushi Miyashita & Wayne O’Neil (eds.), Image, language, brain: Papers from the first mind articulation project symposium, 95–126. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.10.7551/mitpress/3654.003.0008Search in Google Scholar

Gray, Bethany. 2013. More than discipline: Uncovering multi-dimensional patterns of variation in academic research articles. Corpora 8(2). 153–181. https://doi.org/10.3366/cor.2013.0039.Search in Google Scholar

Gray, Bethany. 2015. On the complexity of academic writing: Disciplinary variation and structural complexity. In Viviana Cortes & Eniko Csomay (eds.), Corpus-based research in applied linguistics: Studies in honor of Doug Biber, 49–78. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/scl.66.03graSearch in Google Scholar

Gray, Bethany. 2021. The register-functional approach to grammatical complexity: Theoretical foundation, descriptive research findings, application. New York: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Halliday, Michael A. K. 1961. Categories of the theory of grammar. WORD 17(2). 241–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/00437956.1961.11659756.Search in Google Scholar

Halliday, Michael A. K. 1987. Spoken and written modes of meaning. In Rosalind Horowitz & S. Jay Samuels (eds.), Comprehending oral and written language, 55–82. New York: Academic Press.10.1163/9789004653436_006Search in Google Scholar

Halliday, Michael A. K. 1994. An introduction to functional grammar, 2nd edn. London: Arnold.Search in Google Scholar

Halliday, Michael A. K. 2004. Language and knowledge: The “unpacking” of text. In Jonathan J. Webster (ed.), Collected works of M. A. K. Halliday, vol. 5: The language of science, 24–48. London: Continuum.Search in Google Scholar

Halliday, Michael A. K. & Ruqaiya Hasan. 1976. Cohesion in English. London: Longman.Search in Google Scholar

Halliday, Michael A. K. & James R. Martin. 1993. Writing science: Literacy and discursive power. London: Falmer Press.Search in Google Scholar

Halliday, Michael A. K. & Christian M. I. M. Matthiessen. 1999. Construing experience through meaning: A language-based approach to cognition. London: Continuum.Search in Google Scholar

Halliday, Michael A. K. & Christian M. I. M. Matthiessen. 2014. Halliday’s introduction to functional grammar, 4th edn. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780203783771Search in Google Scholar

He, Qingshun & Bingjun Yang. 2018. A corpus-based study of the correlation between text technicality and ideational metaphor in English. Lingua 203. 51–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2017.10.005.Search in Google Scholar

He, Qingshun & Qianqian Zhang. 2024. A corpus-based study of live grammatical metaphor in English academic writing. Studia Neophilologica 96. 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/00393274.2024.2373728.Search in Google Scholar

Honnibal, Matthew & Ines Montani. 2019. spaCy 2: Natural language understanding with bloom embeddings, convolutional neural networks and incremental parsing (version 2.0.18). https://spacy.io (accessed 10 November 2025).Search in Google Scholar

Hu, Yiyang & Qingshun He. 2023. A corpus-based study of the distributions of adnominals across registers and disciplines. Journal of Quantitative Linguistics 30(2). 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/09296174.2023.2209487.Search in Google Scholar

Hudson, Richard. 1995. Measuring syntactic difficulty. London: University College, London.Search in Google Scholar

Hudson, Richard. 2010. An introduction to word grammar. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511781964Search in Google Scholar

Hyland, Ken. 2000. Disciplinary discourses: Social interactions in academic writing. London: Longman.Search in Google Scholar

Hyland, Ken. 2004. Disciplinary discourses: Social interactions in academic writing. Michigan: The University of Michigan Press.Search in Google Scholar

Hyland, Ken. 2009. Academic discourse: English in a global context. London: Continuum.Search in Google Scholar

Hyland, Ken. 2015. Genre, discipline, and identity in academic writing. Journal of English for Academic Purposes 19. 32–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2015.02.005.Search in Google Scholar

Hyland, Ken & Polly Tse. 2005. Hooking the reader: A corpus study of evaluative that in abstracts. English for Specific Purposes 24(2). 123–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2004.02.002.Search in Google Scholar

Jiang, Jingyang & Haitao Liu. 2015. The effects of sentence length on dependency distance, dependency direction, and the implications – Based on a parallel English-Chinese dependency treebank. Language Sciences 50. 93–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langsci.2015.04.002.Search in Google Scholar

Khany, Reza & Neda B. Kafshgar. 2016. Analysing texts through their linguistic properties: A cross-disciplinary study. Journal of Quantitative Linguistics 23(3). 278–294. https://doi.org/10.1080/09296174.2016.1169848.Search in Google Scholar

Köhler, Reinhard. 1986. Zur linguistischen synergetik. struktur und dynamik der lexik. Bochum: Brockmeyer.Search in Google Scholar

Köhler, Reinhard. 2012. Quantitative syntax analysis. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9783110272925Search in Google Scholar

Kyle, Kristopher. 2016. Measuring syntactic development in L2 writing: Fine-grained indices of syntactic complexity and usage-based indices of syntactic sophistication. Atlanta, GA: Georgia State University PhD thesis.Search in Google Scholar

Liu, Haitao. 2008. Dependency distance as a metric of language comprehension difficulty. Journal of Cognitive Science 9(2). 159–191. https://doi.org/10.17791/jcs.2008.9.2.159.Search in Google Scholar

Liu, Haitao, Richard Hudson & Zhiwei Feng. 2009. Using a Chinese treebank to measure dependency distance. Corpus Linguistics and Linguistic Theory 5(2). 161–174. https://doi.org/10.1515/cllt.2009.007.Search in Google Scholar

Lores, Rosa. 2004. On RA abstracts: From rhetorical structure to thematic organization. English for Specific Purposes 23(3). 280–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2003.06.001.Search in Google Scholar

Lu, Xiaofei. 2017. Automated measurement of syntactic complexity in corpus-based L2 writing research and implications for writing assessment. Language Testing 34(4). 493–511. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265532217710675.Search in Google Scholar

Lu, Xiaofei, J. Elliott Casal & Yingying Liu. 2021. The rhetorical functions of syntactically complex sentences in social science research article introductions. Journal of English for Academic Purposes 49. 100832. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2019.100832.Search in Google Scholar

Mazgutova, Diana & Judit Kormos. 2015. Syntactic and lexical development in an intensive English for academic purposes programme. Journal of Second Language Writing 29. 3–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2015.06.004.Search in Google Scholar

Ortega, Lourdes. 2003. Syntactic complexity measures and their relationship to L2 proficiency: A research synthesis of college-level L2 writing. Applied Linguistics 24(4). 492–518. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/24.4.492.Search in Google Scholar

Oya, Masanori. 2013. Degree centralities, closeness centralities, and dependency distances of different genres of texts. In Selected papers of the 17th conference of Pan-Pacific Association of applied linguistics, 42–53.Search in Google Scholar

Pan, Fan & Xinyi Zhou. 2024. Are research articles becoming more syntactically complex? Corpus-based evidence from research articles in applied linguistics and biology (1965–2015). Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies 42(4). 554–571. https://doi.org/10.2989/16073614.2024.2333280.Search in Google Scholar

Pho, Phuong Dzung. 2008. Research article abstracts in applied linguistics and educational technology: A study of linguistic realizations of rhetorical structure and authorial stance. Discourse Studies 10(2). 231–250. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445607087010.Search in Google Scholar

Rimmer, Wayne. 2006. Measuring grammatical complexity: The Gordian knot. Language Testing 23(4). 497–519. https://doi.org/10.1191/0265532206lt339oa.Search in Google Scholar

Staples, Shelley, Jesse Egbert, Douglas Biber & Bethany Gray. 2016. Academic writing development at the university level: Phrasal and clausal complexity across level of study, discipline, and genre. Written Communication 33(2). 149–183. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741088316631527.Search in Google Scholar

Swales, John M. & Christine B. Feak. 2009. Abstracts and the writing of abstracts. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.10.3998/mpub.309332Search in Google Scholar

Wang, Yaqin & Haitao Liu. 2017. The effects of genre on dependency distance and dependency direction. Language Sciences 59. 135–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langsci.2016.09.006.Search in Google Scholar

Ziaeian, Elahe & Seyyed E. Golparvar. 2022. Fine-grained measures of syntactic complexity in the discussion section of research articles: The effect of discipline and language background. Journal of English for Academic Purposes 57. 101116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2022.101116.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter and FLTRP on behalf of BFSU

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.