Abstract

This paper focuses on vocalisations in the microlanguage of a man with a severe intellectual disability named Bodhi, who is functionally nonverbal. To make meaning, Bodhi deploys a variety of modes of expression, including non-speech vocalisations. These have received little attention, other than looking at his use of intonation. In this paper we begin to explore how his vocalisations contribute to meaning and how we might map the meaning making variations occurring in his vocalisations. We build on Dreyfus’ model of nonverbal communication and Ariztimuño’s system of vocal features to show the contributions of sound to Bodhi’s microlanguage. Dreyfus’ model focuses on Bodhi’s self-initiated system of exchanges, which privileges the interpersonal as the key driver of his communication. The main vocal qualities Bodhi uses to make his meanings relate to pitch height, loudness, tempo and tension. The paper will explore how the tendencies of association between these vocal qualities and meanings can provide further tools of interpretation for his communication partners. As such, this paper will set the foundations to enhance the understanding of Bodhi’s spoken communication and potentially act as an example of how to explore the spoken communication of others who rely on nonverbal communication and thus, hopefully, improve the quality of their interactions.

1 Introduction

Spoken communication comprises a set of complementary resources which are typically anchored in a language shared by the interactants of a specific context of communication. From a Systemic Functional Semiotic (SFS) perspective, this shared spoken language can be modelled “as a three-level coding system” with a (discourse) semantics stratum, a lexicogrammatical stratum and a phonological stratum (Halliday 2003 [1977]: 83). The interpretation of meanings in spoken communication depends, therefore, on a shared understanding of meanings realised by an array of choices taking place at each stratum. Furthermore, spoken language interacts with different semiotic resources (images, gestures, facial expression, music, noise, etc.) to create meanings which can only be fully interpreted by considering the complementarity of these semiotic resources in the creation of meaning in spoken communication (Ariztimuño 2024; Martin 1992; Matthiessen 2007). But what happens when only one of the communication partners uses the typical three-level coding system of speech and the other relies mainly on a two-level coding system consisting of meanings in one stratum and different expression resources in the other? This paper focuses on this situation by focusing on the spoken communication that takes place between communication partners who are speakers of English and a man, Bodhi, who communicates with a restricted set of word approximations and a variety of other modes of expression including vocalisations, pictures, gestures and other semiotic resources. Bodhi is a 30-year-old man with a severe intellectual disability who is functionally nonverbal but who loves to communicate. His mother Shoshana Dreyfus, a systemic functional linguist, has been trying to support him to improve his communication for many years and as part of that endeavour, has been using systemic functional linguistics (SFL) to describe his multimodal multifunctional communication. This paper is the next iteration in that description process.

Prior to this paper, Bodhi’s meaning making potential has been described in a number of ways (see Dreyfus 2007, 2013), first examining both Bodhi’s different modes of communication that he deploys to make his meanings (in SFL terms, his expression plane) and the kinds of meanings he makes (in SFL terms, his content plane). However, in terms of the expression plane, other than an examination of the tones Bodhi uses in his microlanguage (following Halliday 1984) (Dreyfus 2013), no attention has been paid to the many other aspects of his vocalisations. As Bodhi uses vocalisations with almost every move he makes, we seek to explore how these vocalisations contribute to meaning and how we might map the meaning making variations occurring in his vocalisations, by deploying Systemic Functional Linguistic systems other than intonation (Halliday 1967; Halliday and Greaves 2008). This paper thus examines the ways sound is used as part of the meaning making ensemble in the communication of one man with a severe intellectual disability who is functionally nonverbal.

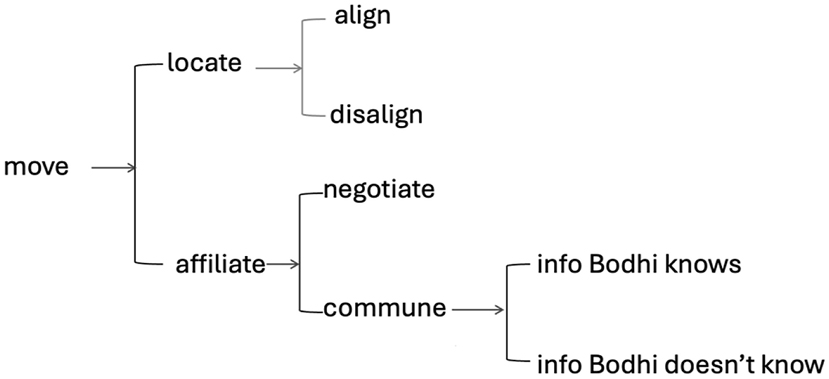

To do this, we build on the model of nonverbal communication developed by Dreyfus (2013) and the system of vocal qualities developed by Ariztimuño (2024, 2025). Dreyfus’ (2013) model focuses on Bodhi’s self-initiated system of exchanges and this paper further explores Bodhi’s use of phonological resources to construe two types of initiating meanings: those oriented to the locating type and those oriented to the affiliating type (see Figure 2 below). The locating meanings are where Bodhi names the people he wishes to interact with (and thus to have as part of his affiliation community), whereas the affiliating meanings are where he enacts different kinds of activities and actions with his communication partners. In this latter type, we also explore additional meanings Bodhi makes which show his engagement in the unfolding of communication exchanges and demonstrate how the interpersonal is the key driver of his main communication moves.

For Bodhi’s locating meanings, we describe his sound realisation in terms of the lowest phonological ranks, the phoneme and the syllable at the articulation domains (Bowcher and Debashish 2019; Matthiessen 2021), because these are word approximations (sounds that are close to the phonological realisation of a word, e.g. Mum is realised as /mʌm or bʌm/). In contrast, his affiliating meanings, which are not word approximations, are typically realised by a combination of vocal features that bundle together at what we are arguing is Bodhi’s microlanguage highest phonological rank; the ‘sounding unit’ (described in detail in Section 4). In analysing these using Ariztimuño’s (2024, 2025) vocal qualities system, we have found that the main subsystems Bodhi uses to show differences in affiliating meanings are pitch height, loudness, tempo and tension.

In the following sections of this paper, we explore preliminary tendencies of association between the meanings Bodhi makes and the vocal qualities he uses. We first describe Bodhi’s communication resources, and his communication system, following and extending Dreyfus (2013). We then describe the aspects of the vocal qualities system that Bodhi draws on in his meaning making to come up with an initial description of vocal profiles for each of Bodhi’s moves. The overall aim is to provide further tools of interpretation for Bodhi’s communication partners and hopefully exemplify future areas of research for the semiosis of other functionally nonverbal communicators. As such, we hope this paper will set the foundations for enhancing understanding of Bodhi’s communication and thus improve the quality of his interactions with others.

2 Describing Bodhi’s communication

Bodhi is a truly multimodal communicator. His multimodal ensemble of resources includes gestures, sounds/vocalisations, sign language, artefacts, actions, behaviour and eye gaze (Dreyfus 2013). Gestures include such actions as pointing to things he wants to talk about. Sounds include two clear word approximations (Mum and Dad) and a range of vowel sounds that indicate he’s communicating about something (see Section 6). Bodhi’s sign language includes a small number of signs he can manage. These are the signs for yes, more, please and toilet. Artefacts cover things he points to, such as a cup or bottle for a drink, picture symbols from the Boardmaker™ program, photos on his iPad and his PODD (Pragmatically Organised Dynamic Display) communication program which is loaded onto his iPad. Actions include leading someone somewhere while behaviour refers to what are commonly known as ‘behaviours of concern’[1] (Chan 2015; Chan et al. 2011) such as kicking or banging a door to show he wants to go out. Eye gaze refers to the fact that when Bodhi is communicating with someone, he looks directly at them.

In modelling Bodhi’s communication, the focus has always been on proficiency – what CAN he do with all those semiotic resources to ensure communication, rather than on deficiency – what he can’t do (Dreyfus 2013). And while Bodhi cannot speak in words, he can certainly understand them and requires that the communication partner transmodalise his multimodal communication move (Dreyfus 2007). In some sense, this is like asking for a linguistic service (Ventola 1987), where Bodhi requires the communication partner to say back to him in words what he has just communicated multimodally (see Dreyfus 2007 for a more detailed description of this). To illustrate, Example (1), named ‘The waterfall’ (audio file available in the Supplementary Material as Audio 1), includes an extract from an exchange between Bodhi and his communication partner where this transmodalisation is evident.

| The waterfall | ||

| Bodhi: | // ʌ //2 | |

| (Bodhi looks through his pictures, finds & points to the picture “beach”, looks at the CP*) | ||

| CP: | Uh, you wanna go round to the beach? | |

| Bodhi: | // ɪ // | |

| // ɪ // | ||

| (points to picture, looks at CP) | ||

| CP: | (overlapping) Are you telling me you want to go round to the beach? | |

| Bodhi: | // ɪ // | |

| (points to the waterfall) | ||

| CP: | That’s the waterfall! | |

| Note: *CP means communication partner. | ||

- 2

We have used the International Phonetic Alphabet to create a broad transcription of Bodhi’s vocalisations.

The waterfall example shows Bodhi and his communication partner, his mother Shooshi, working together to construe the meaning he is trying to make, which in this case, is to tell Shooshi that the waterfall looks like a beach. Bodhi communicates his move multimodally and Shooshi transmodalises it by repeating it back in words. Working with Bodhi like this to jointly construct meaning, as it were, relies on a high degree of mutuality (Klotz 2001), a willingness to enter his world and negotiate with him the meanings he is trying to make (Dreyfus 2007).

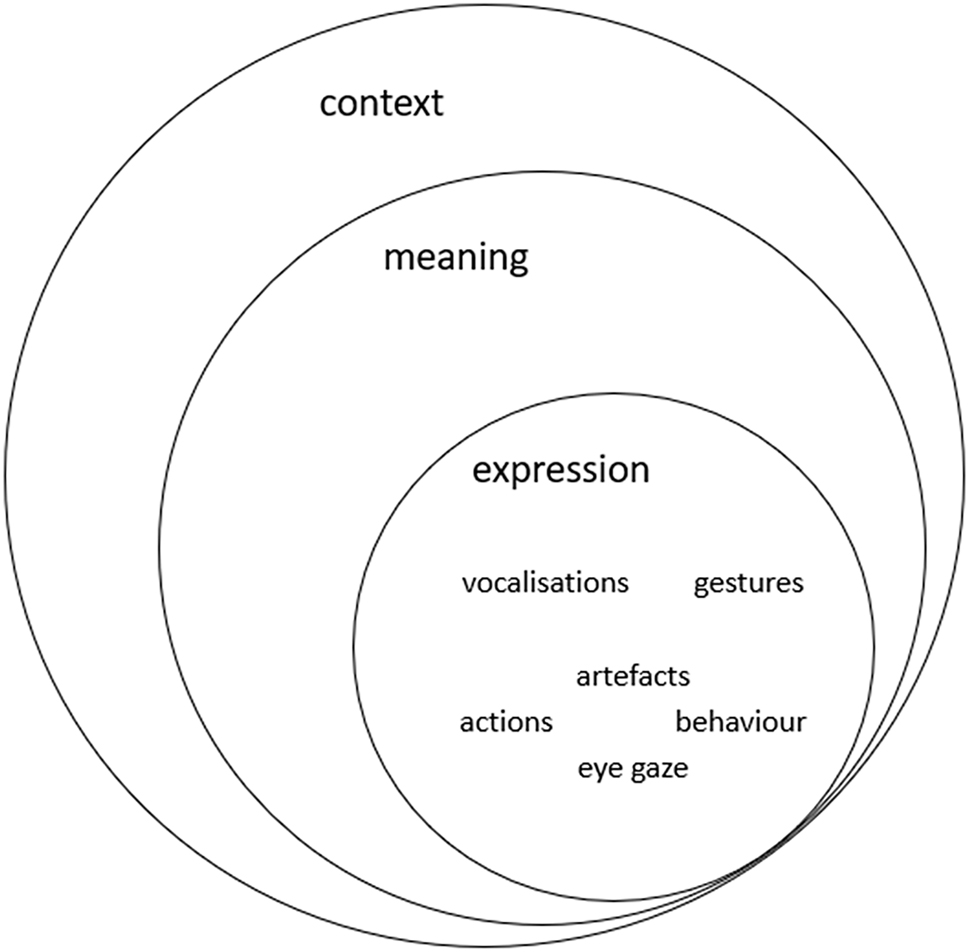

A key challenge to explore and describe Bodhi’s communication is our tendency as linguists to apply our known model of language to Bodhi’s unique communication. However, our fully-fledged tri-stratal model of language evolves from a previous simpler bi-stratal model of protolanguage (Halliday 1975). As such, we take these existing models of language and protolanguage to inform our description of Bodhi’s stratified model of multimodal communication, including the variety of multimodal resources he uses to share meaning with his communication partners in specific contexts. This realisational connection between meanings and multimodal expression can be visually represented as per Figure 1.

Bodhi’s stratified model of multimodal communication.

The cotangential circles used in Figure 1 follow the SFL representation of language as a stratified meaning-making system where meaning is realised by the realisation of wording in sound (Halliday 2003 [1992]: 357). As such, language works together with other semiotic resources in an interconnected way as it both influences and is influenced by context (see Halliday 2003 [1977]; Martin 1992; Matthiessen 2007). Bodhi’s stratified model of multimodal communication employs the same metaphorical representation to show how Bodhi makes meanings, which are influenced by the context in which he is interacting, as well as by the expression resources he has available at that particular moment. To illustrate, the interactions we have analysed for this paper show Bodhi interacting inside his house, in a car and outside in the open air. These different locations offer Bodhi different expression resources to realise his meanings. For example, while his house and open-air spaces afford him the possibility to move closer or farther away from his communication partner, this is not possible when he is in the car. Further, the person he is communicating with also affords him different resources as not all his communication partners are familiar with the different meanings he communicates either vocally or by means of visual aids and gestures. It could be argued that the success of Bodhi’s communication is greatly influenced by his communication partner, the location in which he is communicating and how many communication resources he has available to communicate with. We could argue that Bodhi’s stratified model of multimodal communication shares the context and most of his expression resources with many of his communication partners but the meanings he communicates, and the interpretation of certain vocalisations, are only accessible to the communicator partners who are most familiar with him and his communication. This is not uncommon with nonverbal multimodal communicators whose most intimate communication partners are used to their idiosyncratic ways of communicating (Dreyfus 2013).

When Bodhi’s communication is successful, we have identified two main types of functional meanings Bodhi shares with his communication partner: locating meanings, which identify and name people, things and places, and affiliating meanings, which involve requests for actions or the provision and request of information, all in the service of creating bonds with other humans (Dreyfus 2013).

3 Bodhi’s meaning making systems

The main consideration in describing Bodhi’s multimodal multifunctional communication is to view it on its own terms (Martin 2011) rather than to overlay systems used to describe the spoken and written modes of English onto a different kind of communication system. Given Bodhi is highly communicative, initiating over 60 % of all interactions that he is involved with (Dreyfus 2013), his system of communication is developed on what Bodhi shows us he wants to communicate about. As such, this system draws on affiliation and bonding theory after Knight (2010) and Zappavigna (2011). Both Knight and Zappavigna have shown how people frequently negotiate their alignment with each other to form social bonds which others can respond to, commune over or affiliate around. They can also reject those bonds. In Bodhi’s case, he proposes bonds for his various communication partners to resolve. Based on the discourse semantic system for spoken communication, exchange structure analysis (after Martin 1992; Sinclair and Coulthard 1975; Ventola 1987), this model has presented a new way for thinking about the way people with intellectual disability and complex communication needs, like Bodhi, negotiate their social environment with the conversational moves they make.

As Figure 2 shows, the entry point for Bodhi’s communication system is a move, which is initiated by him. The first type of move is named ‘locate’, which mainly communicates who Bodhi wishes or does not wish to be a part of his communication experience in any particular moment. This move is realised by means of different expression resources, such as Bodhi pointing at a photo of a person, his use of word-like vocalisations to name people (described in detail in Section 6) or his use of waving off gestures to show the people he does not want to be present. The locate system is designed to capture Bodhi’s need to work out who is and who isn’t available to bond with. Many nonverbal people with intellectual disabilities like Bodhi have little control over what happens in their lives and little opportunity to ‘talk’ about who comes and goes from their lives and yet we know this is important to them (NPDCC 2009), in the same way it is important to any person to know who they’re going to be seeing. As such, Bodhi regularly initiates with these moves. The first type of locate move is named ‘align’; this is where Bodhi is trying to find out who is present or will be present in the future. This kind of exchange is resolved by the communication partner telling Bodhi whether they or someone else will or won’t be present. The following exchange in Table 1 (audio file available in the Supplementary Material as Audio 2), shows Bodhi going out in the car with his father Mark and trying to work out who else in the family is coming.

Bodhi’s self-initiated communication system.

Who’s coming?

| Moves | Person | Text | Gloss | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Locate | Align | Bodhi | // dæd // // dæd // // dæd // // dæd // | Dad’s coming in the car |

| Confirm align | Mark | Yes you’re going with Dad in the car | ||

| Align | Bodhi | // bʌm // // bʌm // | Is Mum coming? | |

| Check | Mark | Is Mum coming? | ||

| Align | Bodhi | // ɪ // // ʌ // | Is Davi (his brother) coming? | |

| Confirm align | Mark | No Davi’s not coming. Mum’s not coming | ||

In this exchange, after Bodhi names his dad as if to acknowledge his presence in the shared experience, he then asks whether his mum is coming and then whether his older brother is coming, using the vowel sound he makes for his brother (// ʌ //). Note that there are other moves, referred to as tracking moves (Martin 1992) such as the ‘check’ move, which interrupt the exchange to sort something out before being able to proceed. The check move is where the communication partner is checking whether they have understood Bodhi correctly. If they have, Bodhi moves onto something else, as shown above where Bodhi is happy with Mark’s response about whether his mum is coming and so moves on to ask about his brother.

The second type of locate move is called ‘disalign’. This refers to Bodhi’s desire to remove people from his community when he thinks they shouldn’t be there or doesn’t want them there. Bodhi makes this move regularly, for example, when support workers at his home finish their shift and new ones come on shift. This move is realised by Bodhi waving people off or even pushing them towards the door when their shift is finished.

The next type of subsystem is named ‘affiliate’, which shows Bodhi’s intent to enact different affiliating functions that will guide his communication partner to provide him with things or information he wants, and to share meanings with him. Affiliate is divided into two moves, ‘negotiate’ and ‘commune’. Negotiate captures Bodhi’s moves to get people to do things with him and for him – i.e. negotiating goods-&-services. Bodhi enacts this kind of move regularly, using a variety of modes of expression, such as pointing to pictures of what he wants while vocalising. For example, he will point to a picture of a drink when he wants one or to a picture of an activity he wants to do while vocalising. This kind of move is resolved by the communication partner doing what he wants. The communication partner’s resolving move has been named ‘comply’.

The commune move covers Bodhi’s desire to bond with people by getting them to say stuff (i.e. information) to and for him. It is further divided into ‘info Bodhi knows’ and ‘info Bodhi doesn’t know’. ‘Info Bodhi knows’ refers to when he makes a multimodal move such as in the waterfall example above, where he is already communicating the experiential content of the multimodal move he is making and wants the communication partner to transmodalise it, detailed further below. ‘Info Bodhi doesn’t know’ refers to when he doesn’t know the answer to what he is asking. Both of these can be seen in the example in Table 2 (audio available in the Supplementary Material as Audio 3), which shows a sequence of small exchanges when Bodhi is being picked up from his home by his mum Shooshi and accompanying them is a film maker called Brian, who will be videoing Shooshi’s and Bodhi communication. Bodhi has not met the film maker before and wants to know who he is and if he’s coming.

Brian and his camera.

| Moves | Person | Text | Gloss | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exchange 1 Affiliate |

Commune (info Bodhi doesn’t know) | Bodhi | // ɪ // (pointing and looking towards Brian) | What’s your name? |

| Empathise | Shooshi | Brian | ||

| Confirm | Bodhi | // ɪ // | Ok | |

| Elaborate | Shooshi | Bodhi, Brian’s going to use his camera while we go out. Ok? He’s going to be using his camera | ||

| Confirm | Bodhi | // ʌ // // ʌ // // ʌ // // ʌ // | Ok | |

| Exchange 2 affiliate | Commune (info Bodhi doesn’t know) | Bodhi | // ɪ // // ɪ // // ɪ // (looking and tapping Brian?) | Are you coming with us Brian? |

| Clarify/ explain to CP | Shooshi | He wants to know if you’re coming | ||

| Empathise | Brian | Yes, yes I’m coming | ||

| Resolved | Bodhi | // m // (smiles) | Ok | |

| Exchange 3 Affiliate |

Commune (info Bodhi knows) | Bodhi | // ʊ // // ʊ //(tapping the camera) | Brian’s got a film camera |

| Empathise | Shooshi | And he’s using his camera. He’s going to bring his camera. That’s right. | ||

In the Brian and his camera example, Bodhi initiates the first exchange by pointing to Brian, who he has never seen before, vocalising and looking across at his mum Shooshi to ask her to tell him who Brian is – info Bodhi doesn’t know the answer to. Shooshi responds with an empathise move by telling Bodhi Brain’s name. Bodhi’s next move is a confirm, where he shows he is satisfied with her response (as shown below, our phonological analysis confirms this). Shooshi then elaborates on her empathise move to explain to Bodhi that Brian will be coming with them and using his camera to film them. Bodhi then initiates a new exchange by vocalising and tapping Brian to ask Brian if he is, in fact, coming with them, again info Bodhi doesn’t know, or wants confirmed. As Brian is new to Bodhi and doesn’t understand his undifferentiated communication moves, Shooshi then makes a clarifying move to explain to Brian what Bodhi wants to know. Brian then responds with an empathise move, saying that he is, in fact, coming, to which Bodhi responds with a resolve move by smiling and vocalising a satisfied sound. Bodhi then initiates a third exchange by vocalising and tapping the camera. This move is info he does know as he is telling Shooshi that Brian has a camera which he is going to use. Shooshi empathises by transmodalising Bodhi’s move about Brian using his camera.

As illustrated in this example, major communication partner moves are also given particular names in this system. When Bodhi is communing (both info he does know and info he doesn’t know), the communication partner’s response is named ‘empathise’, as they need to bond empathically with him, articulating in words what he has communicated multimodally. Only communication partners who know him intimately or those who have been trained in this distinction are able to respond appropriately. When Bodhi is negotiating, the communication partner’s response move is named ‘comply’, as they need to carry out an action he wants. Bodhi has response moves, such as ‘replay’, when the communication partner hasn’t understood him and so he replays his move to try to get them to have another go at understanding him; ‘confirm’, when he is satisfied with the communication partner’s response; and ‘encourage’, when he’s excited and happy and this encourages the communication partner to continue communicating with him. Finally, as can be seen in the example above, Bodhi also has a final move in exchanges he has initiated, which shows he is happy with how the exchange has proceeded and considers it resolved. We thus named this move ‘resolved’.

4 Bodhi’s sound semiotic resources

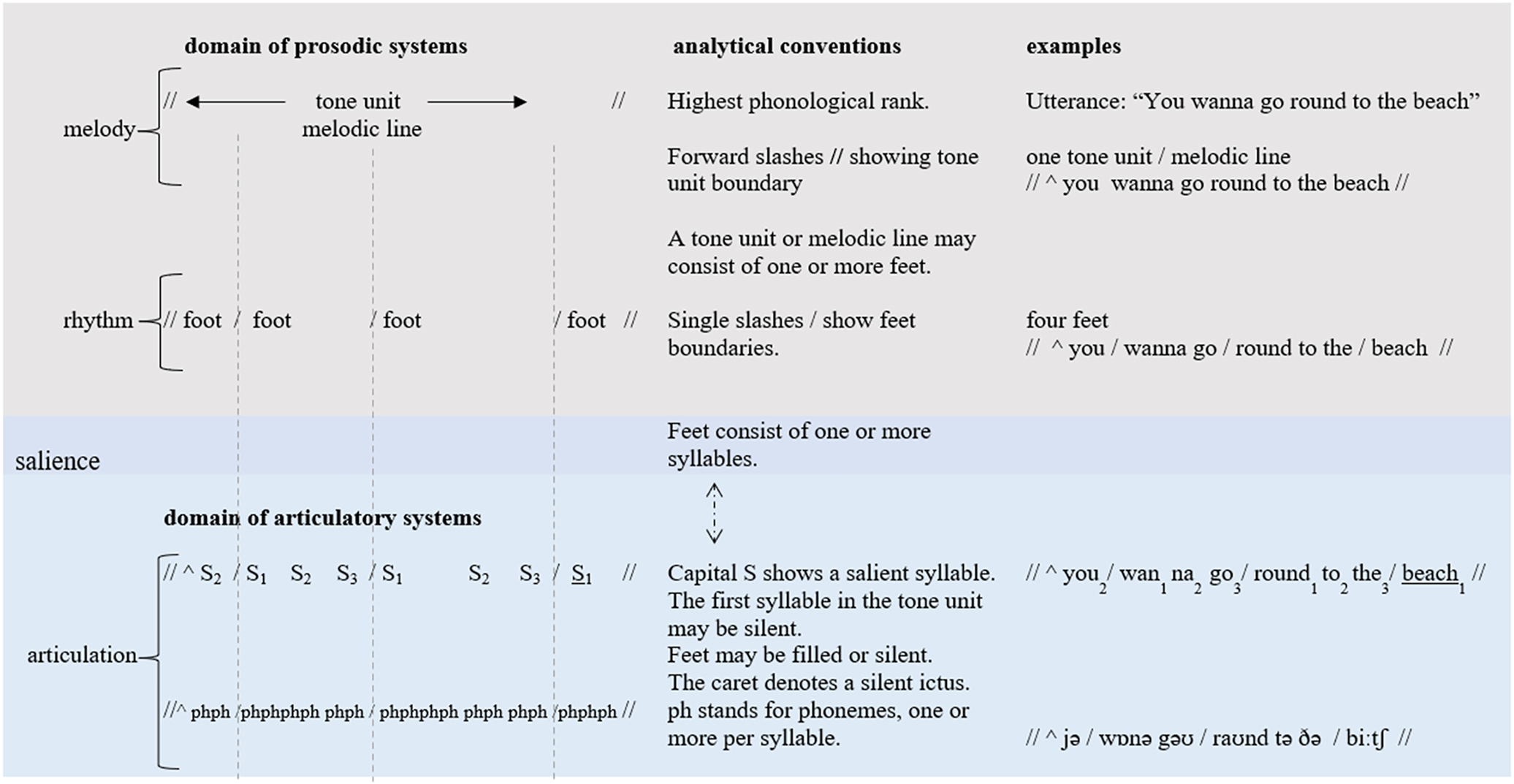

To further understand Bodhi’s meaning making resources, we focus here on Bodhi’s vocalisations because they work together with other semiotic resources to realise his locating and affiliating meanings. To describe how Bodhi represents different people he’s communicating about within the ‘locate’ system, we briefly explore phonemic distinctions, such as the word-approximations he uses to name his dad and mum, which fall within what has been described as the domains of articulatory systems with SFL (e.g. Halliday et al. 1964; Matthiessen 2021; Tench 2011). The more varied affiliating moves Bodhi enacts are described in detail via a selection of vocal features proposed by Ariztimuño (2024, 2025), described within the prosodic phonological rank. While these two phonological levels have been explored in SFL for English language users (e.g. Halliday 1967, 1970; Halliday and Greaves 2008; Lukin and Rivas 2020; O’Grady 2020; Ramírez-Verdugo 2021; Smith 2008; Tench 1996; van Leeuwen 1992), we argue that Bodhi’s vocalisations can be mapped out with adjustments to this existing sound description. We first describe the phonological ranks for English with an example from one of Bodhi’s communication partners in Figure 3 before moving on to consider what Bodhi’s phonological ranks look like.

Phonological ranks for English with analytical conventions and examples (adapted from Bowcher and Debashish 2019: 176).

Figure 3 shows a comprehensive picture of the phonological domains and the analytical conventions, accompanied by examples that show how the highest ranks are constituted by units at lower ranks. As such, along the top horizontal axis we can see the domains followed by the conventions and the examples, whereas along the left side of the vertical axis the ranks extend from the highest at the top to the lowest at the bottom. Under the domain of the prosodic systems (top half) is the tone unit, which refers to a melodic line (Halliday and Greaves 2008) that includes an initial “intake of air – and a potential final pause” (Tench 1976: 13) and the foot, which refers to “one strong, or salient, syllable together with any weak syllable(s) following on” (Halliday and Matthiessen 2014: 12). The bottom half of Figure 3 shows the articulatory systems, constituted by the syllable and the phoneme – “with the syllable as a ‘gateway’ between the prosodic and the articulatory domains” (Matthiessen 2021: 301, emphasis in the original). The prototypical prosodic systems in speech are rhythm, intonation and salience (Halliday and Matthiessen 2014), and these tend to operate over longer stretches of speech than the articulatory systems (e.g. backness and height for English vowel sounds; and place, manner, laterality and voicing for English consonant sounds [Matthiessen 2021]).[3] When we examine the communication partner’s utterance “You wanna go round to the beach” (from Example 1 above) and included in the ‘examples’ column in Figure 3, we can see how each phonological level can be mapped onto the sounds used. As such, we can describe this utterance as having one tone unit consisting of four feet, nine syllables and twenty-one phonemes. In contrast to this, Bodhi’s use of meaningful sounds does not exploit the range of systems that have been used to describe English.

At the articulatory level, Bodhi’s phoneme repertoire consists of three consonant sounds /d, b, m/ and five vowel sounds /ɪ, æ, ʌ, ɜ, ʊ/, which he tends to accompany with a nasal release. His syllable structure is either a consonant/vowel/consonant syllable word-like vocalisation such as /mʌm/ or a single vowel vocalisation which tends to be nasalised. At the prosodic level, Bodhi’s main realisation consists of a melodic unit that is formed by one foot consisting of one syllable such as // ɪ //. Further, if we analyse his vocalisations using the prototypical prosodic systems of rhythm, intonation and salience (Halliday and Matthiessen 2014), the meanings that are associated with these systems in English appear to be irrelevant to the meanings intended by Bodhi we describe in this paper. This is mainly the case because his prosodic unit, which we call the ‘sounding unit’, consists of one syllable preceded and followed by silence and produced in a rather narrow pitch range.[4] These characteristics differ from the variable structure of the English tone unit, which tends to be realised by more than one syllable with varied rhythmical structures and choices in tone movement. In this sense, Bodhi’s sounding unit shows a stable realisation that cannot be interpreted as showing differences in terms of the intonation systems of tonality, tonicity, and tone.[5]

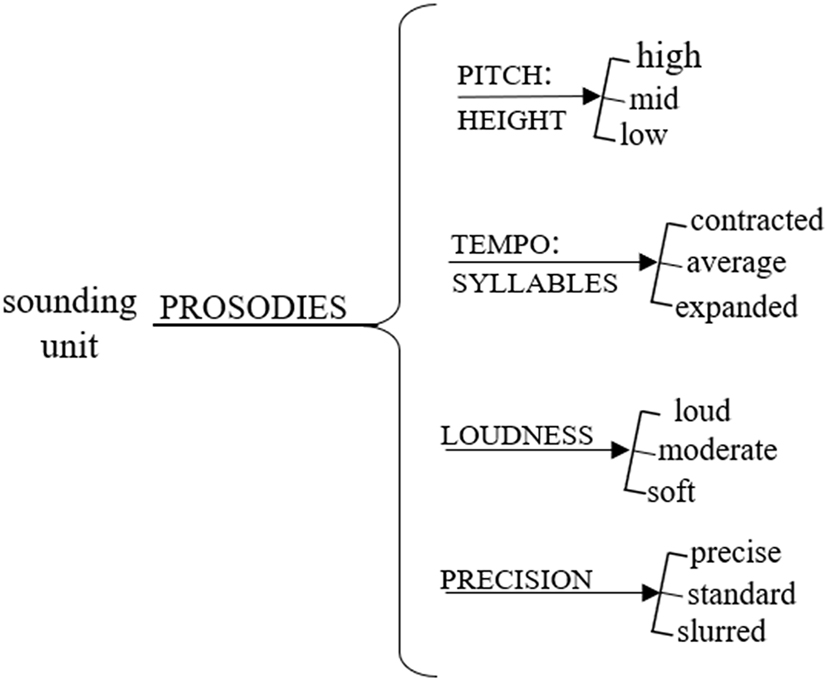

A key system of phonological choices beyond intonation that shows promise for describing Bodhi’s sound meaning-making potential is the system of prosodies (Ariztimuño 2024, 2025), which is developed within the system network for vocal qualities. Ariztimuño (2024, 2025) developed this system as a toolkit for describing a set of simultaneous choices that create “a cluster of features from different prosodic systems”, which Halliday (2003 [1992]: 107) defines as “a selection expression”. The features within the system of vocal qualities are organised into four main subsystems: prosodies, voice qualities, rests and voice qualifications. Since Bodhi seems to make use of a limited set of vocal resources, in this paper we focus on those four sound variables that help describe his vocalisations: pitch: height, tempo: syllables, loudness and precision. These form part of the system of prosodies and are represented as graded choices in a ‘more or less’ cline rather than an ‘either/or’ bipolar scale (van Leeuwen 2022), depicted in Figure 4 as three-pronged oppositions. This allows our description of Bodhi’s tendencies to select, for example, pitch: height: ‘high’ to ‘mid’ when communing about info he knows in contrast with pitch: height: ‘high’ when communing about info he doesn’t know.

Bodhi’s selection of meaning making prosodies (adapted from Ariztimuño 2024, 2025).

The system of prosodies represents phonological choices that are not determined by the physiological characteristics of a person’s vocal apparatus but rather are the role they play in the creation of meaning within a community of speakers. In a sense, these choices can be perceived by any member of a speech community as they fall “above the threshold of audibility” (Pike 1943: 31, as cited in Crystal and Quirk 1964: 32) in such a way that members of that community consider the replacement of a feature by another in the bundle or the lack of a feature in the bundle as “different” in meaning” (Crystal and Quirk 1964: 33). In Bodhi’s case, only highly familiar members of his community, such as his mother, father, and brothers are usually able to identify the slight changes in his prosodic bundle of pitch: height, tempo: syllables, loudness, and precision as distinctive and thus meaningful. This paper attempts to describe these changes perceptually rather than by using software acoustic descriptions as this is how Bodhi’s communication partners intuitively distinguish his sounding meaning making.

The changes in pitch we focus on for Bodhi’s vocalisation resources refer to the auditory sensation we perceive when we hear his voice vibrating at different regular rates; the faster his vocal cords vibrate, the higher the pitch we hear him produce (Brown 2014). This auditory perception is scaled in terms of how high we perceive his placement of the voice: i.e. its height. pitch: height was coded as a scale from ‘high’ to ‘mid’ to ‘low’ depending on the perception of the height of Bodhi’s sounding unit, which, as mentioned, consists of one syllable. The perceptual interpretation and coding of different levels of height depend not only on our familiarity with Bodhi’s indexical identity but also on co-textual choices of pitch. That is, a sounding unit was perceived as ‘high’, ‘mid’ or ‘low’ in relation to the height perceived in the previous utterance. It is important to mention that while the feature of pitch can also be explored in terms of pitch: range, and thus coded as ‘wide’, ‘medial’ or ‘narrow’, depending on “the width of range perceived in the tone movement the speaker produces” (Ariztimuño et al. 2022: 345), this feature has not been considered as relevant for Bodhi’s vocalisation resources as his use of pitch width appears to be consistently narrow. The perceptual description of pitch can also be interpreted as the acoustic phenomenon associated with the frequency of repetition of air pressure peaks, acoustically measured in hertz (Hz hereafter) (Halliday and Greaves 2008). However, while measures in Hz were taken to corroborate challenging instances in our analysis using acoustic measurements in Praat software (version 6.1.38) (Boersma and Weenink 2021) with the command ‘move cursor to maximum pitch’,[6] the aim of this study is provide perceptual descriptions that can be interpreted by Bodhi’s communication partners (and hopefully by other nonverbal communication partners) without the aid of acoustic analysis.

Bodhi’s selection of different pitch levels combines with choices that show varied syllable extensions, which are represented in the system of tempo: syllables (Ariztimuño 2024, 2025). This set of choices describes our perception of the speed of delivery taken to articulate a single syllable. As Bodhi varies the length of his syllables, some syllables are longer while others are shorter than his typical vocalisation. This perceived variation of the extension of time of a single syllable has been classified as ‘expanded’, ‘average’, and ‘contracted’ (Ariztimuño 2024, 2025). Like all the other variables, these values were perceptually classified considering both Bodhi’s tendencies and the context of production.

Another key feature of variation in Bodhi’s vocalisation is loudness, which covers the perception of the volume of speech. Differences in how loud or soft we hear sounds are “brought about by an increase in air pressure from the lungs” (Cruttenden 2008: 22). While these tend to correspond acoustically to the amplitude of the vibration, Bodhi’s sounding units were perceptually classified according to the three points in the loudness scale: ‘loud’, ‘moderate’ and ‘soft’. In cases where our perceptual interpretation needed corroboration, we used Praat to measure differences in intensity in decibels (dB), using the command ‘get intensity’. The final feature we used to describe Bodhi’s use of vocalisation as a meaning-making resource was precision. This feature refers to the tension of articulation (Roach et al. 1998) and appears to be very active and productive for Bodhi. Three features that show differences in precision can be identified in the cline: ‘precise’, ‘standard’ and ‘slurred’ (Ariztimuño 2024 and this issue). The ‘precise’ feature codes instances where Bodhi tenses his articulation of the sounding unit. The feature of ‘standard’ shows cases where no audible tension is perceived, while the ‘slurred’ feature is rarely used by Bodhi and refers to cases where sounds were perceived as relaxed and effortless.

To see Bodhi’s deployment of vocal resources in context, we illustrate all the above-listed features through an example of Bodhi communicating with his father about going up and down a set of steps at the park. In this example in Table 3 (audio available in the Supplementary Material as Audio 4), Bodhi has led his father Mark to the steps and wants to tell him he’s going to go down the steps.

Going down the steps.

| Turn | Move | Person | Text | Prosodies | Gloss |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Commune (info Bodhi knows) | Bodhi: | // ʊ //(points to picture, looks at CP) | Mid, average-extended, moderate, standard | I’m going to go down the steps |

| 2 | Empathise | CP: | More steps | ||

| 3 | Replay commune (info he knows) | Bodhi: | // ɪ // // ɪ //(points to picture, looks at CP) | Mid to high, average, moderate, precise Mid to high, contracted, loud, precise |

I’m going to go down the steps |

| 4 | Empathise | CP: | Steps going down | ||

| 5 | Replay commune (info Bodhi knows) | Bodhi: | // ɪ //(points to picture, looks at CP) | High, extended, moderate, precise | I’m going to go down the steps |

| 6 | Empathise | CP: | Going down the steps | ||

| 7 | Resolved | Bodhi: | // ɪ //(turns and goes down the steps) | Low, average, soft, standard-slurred | |

| 8 | CP: | (Breathes out) |

The above example consists of an eight-move exchange where Bodhi initiates with a clear aim: to tell his father Mark he is going to go down the steps in front of him. However, Mark is not empathising with the right words and Bodhi replays his move until Mark says the right words. While all Bodhi’s sounding units are typically made up of one-vowel-sound syllables, either // ʊ // or // ɪ //, meaningful variation can be observed in his selection of prosodies. These different choices are, in fact, part of what guides his father to verbalise alternate interpretations of Bodhi’s multimodal move. We can see this clearly, for example, in the shifts in pitch level across his turns as he replays his move. These go from mid to mid to high to high and then finally to low, when he is satisfied with Mark’s response. Additionally, these choices are bundled with changes in all three other variables of tempo (with examples of the three features: extended, average and contracted), loudness (shifting from moderate to loud to moderate again to end in soft) and precision (moving from standard to precise to standard-slurred). These kinds of changes represent a key point in our analysis as they show Bodhi’s tendencies to shift vocalisation choices to make affiliating different meanings.

5 Methodology

The data used for the study of Bodhi’s sound semiosis is a selection of exchanges extracted from 23 minutes of sound and video files. These have been collected over years and form the basis for ongoing study of Bodhi’s communication. The ethics clearance for the collection and analysis of this data began in 2002, with a PhD study and has continued over the years with various grants and research projects. The current ethics clearance is granted by the University of Wollongong Human Research Ethics Committee. Consent was provided by the participants and the person with disability’s guardian to use the data for publication. The data were analysed using a top-down approach, starting from the discourse semantic perspective of exchanges, examining the different moves they realise within Bodhi’s self-initiated system of exchanges. For the phonological analysis, the videos and/or audio recordings were transcribed into the writing system of English, Bodhi’s vocalisations were transcribed using IPA broad transcription to describe his use of phonemes as realisations of locating meanings. The video and audio files were then imported into NVivo (version 14) and codes were created to include all the features in the move systems and all the values for the four prosodies systems: pitch: height, tempo: syllables, loudness and precision. After all the selected exchanges were coded, a query was run to look for patterns and tendencies of association among the moves and the vocal qualities. The results, presented in Section 6, show the value of attending more closely to the sounds Bodhi uses in relation to locating and affiliating meanings and how this can help distinguish between his delicate choices.

6 Results

For the results of the phonological analysis, we first examine the locating moves of align (where Bodhi is sorting out who is in his community to bond with) and disalign (where Bodhi is excluding people from his bonding community). We then move onto the affiliating moves of negotiate (where Bodhi is negotiating with a communication partner what he wants to do with them) and commune (where Bodhi is aiming to bond with people over sharing information with him verbally – either info he doesn’t know or info he does know). We also consider Bodhi’s confirm, encourage and resolved moves.

6.1 Locating moves

For the locating moves, articulation (syllable and phoneme) is a key resource which appears to be limited due to both the number of phonemes identified in Bodhi’s repertoire and to the single syllable constitution of his sounding unit. Bodhi uses his phonemic choices to realise meanings interpreted as locate: align, which show him sharing with his communication partner the names of the people who are or will be part of his bonding community. Examples of this include two three-phoneme word-like articulations, /dæd/to name his father and /mʌm/ or /bʌm/ to name his mother. It is interesting to note that Bodhi’s word approximations have changed over time. When he was young and there were no iPads and iPhoto type programs, Bodhi used vowel approximations for his favourite people. Once photo technology became available, he was able to point to photos of people rather try to vocalise their name, which gave him a precision of meaning that had otherwise not been available to him. As such, his word approximations have narrowed.

Figure 5 includes the whole range of articulatory realisations Bodhi uses or has used to align with people.

Articulation as a resource for realising Bodhi’s align move.

As can be seen in Figure 5, Bodhi’s phoneme repertoire is restricted and so is the number of people he names through vocalisations. However, Bodhi use of other semiotic resources such as pictures and photos communicates who he is aligning with, while he uses gestures and movements as articulation resources for disaligning.

A further restriction in Bodhi’s use of articulation is connected to the fact that his sounding unit is comprised of only one syllable. If we go back to the example in Table 3 – Audio 4 and focus on the communication partner’s moves (reproduced as Example (3) below), we can perceive how changes in tonicity, i.e. the information focus in a tone unit, can also afford speakers the possibility to shape the locating meanings they represent.

| Bodhi: | // ʊ // (points to picture, looks at CP) |

| CP: | // 1 more *steps // |

| Bodhi: | // ɪ //// ɪ // (points to picture, looks at CP) |

| CP: | // 1 Steps going *down // |

| Bodhi: | // ɪ // (points to picture, looks at CP) |

| CP: | // 1 Going *down the steps // |

| Bodhi: | // ɪ // (turns and goes down the steps) |

| CP: | (Breathes out) |

While the communication partner, his father Mark, is also restricting the length and complexity of his tone units (two feet each with a maximum of four syllables per tone unit), he is still able to shift the focus to the right bit of information that Bodhi expected in the order he expected. The interpretation would be that Bodhi wanted Mark to describe Bodhi as the implicit actor that was about to perform the action of ‘going down the steps’, with an emphasis on ‘down’ as the only key meaning worth highlighting in the experience. This affordance to foreground or background pieces of experience by making them more or less salient phonologically is not available in Bodhi’s phonological sounding unit which because it is made up of only one syllable/foot.

However, analysing Bodhi’s vocalisations in terms of prosodies allows us to distinguish the different affiliating moves with a greater level of delicacy than what we obtain from looking only at articulation.

6.2 Affiliating moves

For affiliating moves, Bodhi deploys different semiotic resources, including the use of gestures and artifacts to enact his meanings. These might be to negotiate with his communication partner to do something for and with him, to show he is communing about info he knows, to prompt the communication partner to empathise about info he doesn’t know, to encourage his communication partner to keep talking, to confirm the communication partner is going in the right direction or to resolve a section of the exchange. A key resource Bodhi uses in these affiliating moves is vocalisation. While his intonation choices (Dreyfus 2007) show slight movements that differ in width from the ones used in English and thus might be harder to interpret perceptually, the changes in his use of prosodies are more noticeable and thus easier to decipher.

To describe the results that we obtained when exploring Bodhi’s affiliating moves, we first present a quantitative overview (Table 4) before illustrating the tendencies observed from a qualitative perspective in one exchange.

Prosodies and moves preliminary association.

| prosodies Affiliate move (69) |

Pitch: Height | Tempo: Syllable | Loudness | Precision | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Mid | Low | Expanded | Average | Contracted | Loud | Moderate | Soft | Precise | Standard | Slurred | |

| Negotiate (12) | 67 | 33 | 0 | 92 | 8 | 0 | 67 | 33 | 0 | 83 | 17 | 0 |

| Commune info he knows (15) | 67 | 33 | 0 | 80 | 20 | 0 | 53 | 47 | 0 | 87 | 13 | 0 |

| Commune info he doesn’t know (17) | 88 | 12 | 0 | 83 | 17 | 0 | 76 | 24 | 0 | 94 | 6 | 0 |

| Encourage (4) | 100 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 50 | 25 | 75 | 25 | 0 |

| Confirm (7) | 0 | 100 | 0 | 43 | 57 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 24 | 86 | 0 |

| Resolved (14) | 14 | 7 | 79 | 43 | 43 | 14 | 0 | 14 | 86 | 21 | 72 | 7 |

Table 4 shows the preliminary tendencies of association between the features selected for each of the four prosodic variables: pitch height, tempo in syllables, loudness and precision, and Bodhi’s affiliating initiation moves: negotiate, commune info he knows and info he doesn’t know as well as his other affiliating moves: encourage, confirm and resolve.

Along the top axis of Table 4 are the vocal features used to analyse Bodhi’s vocalisations while along the vertical axis (on the left) are the moves from his system. The numbers in brackets represent the total of instances analysed. The numbers for each value (e.g. high, mid or low for pitch: height) show the frequency of occurrence in percentages. The colours highlight the highest percentages and thus the tendencies for each move. Even though all tendencies of association are shared in Table 4, only those with more than 10 instances are explained below.

These preliminary results indicate how Bodhi’s selection of certain bundles of features tends to associate with a particular move. For example, of the three moves of negotiate, commune info he knows and commune info he doesn’t know, it is commune info Bodhi doesn’t know that is the most consistent, with a clear tendency (higher than 75 % for all variables) of high, expanded, loud and precise. This result can be interpretated considering that these features tend to be more audible and striking, thus implying higher urgency to have his move resolved, probably because he doesn’t know the answer to the information he’s seeking. Both the other commune move (info he does know – which is when he is communicating multimodally the information he is asking the CP to transmodalise for him), and his negotiate move are still inclined towards the highest end in pitch height, tempo in syllables, loudness and precision, however they do show variation in their phonological realisation with high to mid for pitch height and loud to moderate for loudness. In other words, they sound slightly softer, lower and less urgent. While these are slight differences, they are key for the communication partner to perceive and interpret in combination with other contextual and multimodal resources in order to be successful in their communication with Bodhi.

In contrast, Bodhi’s resolved move is marked by a clear shift in the vocal features compared to all other moves. It is low in pitch height in 79 % of the cases; less definite in the syllable tempo, including all values for the variable (expanded for 43 % of the cases but just as much for the average value and even contracted in 14 % of the instances); soft in 86 % of the cases and with a standard precision in most cases (72 %). This contrastive selection of choices allows the CP to be more efficient in interpreting when their response to Bodhi’s requests have been successful.

We now show a set of exchanges between Bodhi and his brothers, Nadav and Kai, while in the car, driving to go to the beach (audio available in the Supplementary Material as Audio 5). As such, Table 5 describes the one-minute interaction, including the number of turns in the first column, the move carried out by the interlocutor in the second, the person talking in the third, the text in the fourth and Bodhi’s selection of prosodies in the last column. The example in Table 5 illustrates the delicate qualitative work implied in analysing individual moves for each turn and how the differences foregrounded by the quantitative results manifest in this specific context of communication. The differences in the values selected for each variable have been visualised using graded shades of four colours, one for each prosody.

We are going for a swim.

| Turn | Move | Person | Text | Prosodies | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pitch height | Tempo in syllables | Loudness | Precision | ||||

| 1 | Negotiate | Bodhi | // ɪ //(pointing to swimming picture, looking at Kai) | High | Expanded | Loud | Precise |

| 2 | Check | Nadav | Do you want to go for a swim? | ||||

| 3 | Confirm | Bodhi | // ɪ //(pointing to swimming picture, looking at Kai and then turning to look at Nadav) | Mid | Expanded | Moderate | Standard |

| 4 | Comply | Nadav | We can go for a swim. | ||||

| 5 | Elaborate | Nadav | Hopefully you’ve got some swimmers in your bag. We all brought our swimmers | ||||

| 6 | Commune info Bodhi knows | Bodhi | // ɪ //(looking at Nadav and smiling) | Mid | Expanded | Moderate | Precise |

| 7 | Empathise | Nadav | Yeah. We’re going for a swim at Kiama | ||||

| 8 | Resolved | Bodhi | //ʌ // (happy face) | Low | Expanded | Soft | Standard |

| 9 | Empathise | Nadav | We’re going to the beach | ||||

| 10 | Check | Nadav | Is that what you want me to say? | ||||

| 11 | Encourage | Bodhi | // ʊ // | High | Expanded | Moderate | Precise |

| 12 | Empathise | Nadav | We’re going to the beach. | ||||

| 13 | Elaborate | Nadav | for a swim | ||||

| 14 | Empathise | Kai | we’re gonna… we’re gonna the beach Bodhi | ||||

| 15 | Clarification question | Nadav | Or d’you wanna go in a pool? | ||||

| 16 | Confirm | Bodhi | // ʌ // (smiling/laugh) | Mid | Average | Moderate | Precise |

| 17 | Empathise | Nadav |

There’s no pool in Kiama.

Only the beach. |

||||

| 18 | Commune info he doesn’t know | Bodhi | // ɪ //(flips through his pictures and points to ramp) | High | Expanded | Loud | Precise |

| 19 | Check | Nadav | D’you wanna swim with your. | ||||

| 20 | Commune info he doesn’t know | Bodhi | (Flips through his pictures to find ‘ramp’) points and removes his finger | ||||

| 21 | Clarification question | Nadav | What’s that? (can’t see the picture) | ||||

| 22 | Clarification question | Nadav | Ramp? | ||||

| 23 | Empathise | Nadav | There might be a ramp | ||||

| 24 | Encourage | Bodhi | // ʌ // (claps repeatedly and smiles) | High | Expanded | Moderate | Precise |

| 25 | Replay empathise | Nadav | There might be a ramp | ||||

| 26 | Resolved | Bodhi | // ʌ // (claps and starts turning around to Kai) | Low | Average | Soft | Standard |

| 27 | Empathise | Nadav | There’ll be lots of stairs | ||||

| 28 | Commune info he knows | Bodhi | // ɪ // (looking at Kai) | High | Expanded | Loud | Precise |

| 29 | Empathise | Kai | There might be a ramp Bodhi | ||||

| 30 | Question | Kai | D’you think/Maybe there’s a ramp at Kiama? | ||||

| 31 | Commune info he knows | Bodhi | // ɪ //(flips through his pictures and points to steps) | High | Average | Moderate | Precise |

| 32 | Empathise | Kai | Oh there’ll definitely be steps at Kiama | ||||

| 33 | Encourage | Bodhi | (Claps and smiles and rocks happily) | ||||

| 34 | Empathise | Nadav | There’ll be lots of steps | ||||

| 35 | Empathise | Kai | There’ll definitely be steps at Kiama. | ||||

| 36 | Empathise | Kai | Yeah | ||||

| 37 | Encourage | Bodhi | // ɪ // (claps and smiles and rocks happily) | High | Expanded | Loud | Precise |

| 38 | Empathise | Kai | We’re gonna go on lots of stairs | ||||

| 39 | Resolved | Bodhi | // ʌ // | Mid | Contracted | Soft | Slurred |

| 40 | Empathise | Kai | Lots of stairs, Bodhi. Lots of stairs. | ||||

| 41 | Empathise | Nadav | Gonna go up and down, up and down | ||||

| 42 | Resolved | Bodhi | // hɪ // (smiles) | Low | Expanded | Soft | Precise |

In this set of exchanges, we see Bodhi happily communicating with his brothers about where they are going and what they’ll be doing when they get there. Bodhi initiates different places and activities with his picture cards and his brothers respond by transmodalising into words the pictures he’s pointing to and expanding on them to empathise and build the bonds he is proposing. Because they know he loves ramps and steps, they are offering more empathising around these things, which increases his joy, as can be seen in his encourage moves.

If we focus on Bodhi’s turns, we can see that he deploys all the move choices we have described in this paper. He initiates the exchange with a negotiate move, intended to get his brothers to take him somewhere. This move is realised phonologically by a sounding unit made up of one foot, one syllable and one phoneme, // ɪ //. The key features for understanding Bodhi’s move as negotiate are the result of understanding how the ensemble of visual and vocal cues work together. As such, this move is realised by a cluster of high pitch, expanded syllable tempo, loud volume and precise articulation. Bodhi’s communication partners who are highly familiar with his use of vocalisation in tandem with other semiotic resources can be successful in interpreting and wording his meanings and in perceiving changes in moves realised by the selection of other clusters of prosodies such as what happens in turn 3. Here, Bodhi confirms that he wants to go for a swim and this move can be interpreted by the shifts in three of the four variables: pitch height from high to mid, loudness from loud to moderate and precision from precise to standard. These changes work together with his pointing to the swimming picture and his looking around to both his brothers.

The slight but meaningful shifts in Bodhi’s prosodies are also supported by the fact that his communication partners don’t always respond in the same way to his vocalisations. Turns 6 and 7 show this as Nadav offers the expected response (empathise) to Bodhi’s commune move looking for information he already knows. This success is acknowledged by Bodhi’s following resolved move, which is clearly vocalised with low pitch, soft loudness and standard precision with just one value remaining the same (expanded syllable tempo) as his selections for his previous move. There are four instances of a resolved move in this exchange, all of which are produced with low pitch and one or two other selections of the value that requires a lesser degree of energy to be articulated: slurred for precision, soft for loudness and contracted for tempo in syllables. This illustrates how flexible and productive Bodhi’s choices are and how alert his communication partner needs to be in order to perceive these slight vocal differences, which realise so much meaning.

This flexibility is also visible when we explore the way Bodhi responses to his communication partner’s empathise move. While he might choose to select the vocal qualities we just described for a resolved move, he might also prefer to select values more towards the most energy demanding end of the graded prosodic variables, vocalising a move with high pitch, expanded tempo, loud or moderate loudness and precise precision to show support and positive evaluation towards his communication partner with his encourage move (see turn 11, 24 and 37).

7 Concluding discussion

The paper has aimed to show how attending to the vocal qualities Bodhi uses when making his meanings can help distinguish the types of move he is making. By exploring the four vocal qualities of pitch height, tempo in syllables, loudness and precision, we were able to find patterns in sounds that enable us to distinguish between both different kinds of initiation moves within Bodhi’s affiliate subsystem and different kinds of response moves. Table 6 shows Bodhi’s vocal profiles for the initiating moves from the affiliate subsystem. Along the top axis are the vocal features while along the left side are the three initiating affiliate moves of negotiate, commune info Bodhi knows and commune info Bodhi doesn’t know.

Vocal profile for Bodhi’s moves.

| Moves | Pitch height | Tempo in syllables | Loudness | Precision |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negotiate | High to mid | Expanded | Moderate to loud | Precise |

| Commune info Bodhi knows | High to mid | Expanded | Loud/moderate | Precise |

| Commune info Bodhi doesn’t know | High | Expanded | Loud | Precise |

As can be seen from Table 6, there are slight differences in the tendencies of vocal features for each of the three initiating moves within the affiliate system. Negotiate and commune info Bodhi knows are very similar, with the only difference being that within the feature of loudness, negotiate tends to be moderate rather than loud whereas commune info Bodhi knows tends to be loud or moderate almost equally. This is a very fine-grained distinction. The more obvious distinction comes with the commune info Bodhi doesn’t know move, which tends to be both high in pitch and loud. This would indicate that Bodhi is quite firm about wanting to find out information he doesn’t know as he increases the height and loudness in this move. This corresponds with findings about people with disabilities needing to know what is going on in their life, regardless of whether they can speak or not (NPDCC 2009).

We now move onto the vocal profiles for Bodhi’s response moves of encourage, confirm and resolve. To recap, encourage is where Bodhi urges the communication partner on with a happy excited move; confirm is where he shows he gets the communication partner’s move and resolved is the final move he makes in an exchange to show it is finished.

Table 7 shows that the vocal features of Bodhi’s response moves not only differ from each other but are also very different from his initiation moves. Encourage, as an excited move, is shown through its high pitch, expanded tempo, precise articulation and varied loudness. This indicates that the more excited Bodhi is, the higher the pitch of his vocalisation. In contrast to this, the confirm move has a mid pitch height, an average tempo, with moderate loudness and standard precision. It is thus a midway sound across all features. Finally, the resolved move has low pitch height, expanded or average tempo, is soft in loudness and has standard precision. The two most distinguishing features are, therefore, pitch height and loudness. Overall, when Bodhi initiates, he wants to be noticed and heard, showing his strong desire to communicate his meanings. The variability of his moves occurs mostly in pitch height and loudness which are vocal features that English speakers use to enhance the audibility of their messages (Cruttenden 2008). This in turn could reflect the depth of Bodhi’s desire to bond with people.

Vocal profiles of Bodhi’s response moves.

| Moves | Pitch height | Tempo in syllables | Loudness | Precision |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Encourage | High | Expanded | Varied | Precise |

| Confirm | Mid | Average | Moderate | Standard |

| Resolved | Low | Expanded/average | Soft | Standard |

Overall, applying an SFL perspective to attend to Bodhi’s vocalisations adds to our ability to make sense of his meaning making. In combination with his move system, we can better distinguish different kinds of moves. This is critically important when supporting him to be able to make the meanings he wants to make, with the people he wants to make them with, when he wants to make them. It is our hope that Bodhi’s communication description will inspire more work that showcases the communication strategies deployed by other people who are functionally nonverbal but nonetheless are multimodal multifunctional communicators.

Funding source: University of Wollongong

Award Identifier / Grant number: 888/008/452

-

Research ethics: The conducted research obtained ethical approval from the University of Wollongong Human Research Ethics Committee (approval number 2024/088).

-

Informed consent: Verbal consent was obtained from all individuals and their legal guardians included in the study.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Material.

References

Ariztimuño, Lilián I. 2024. The multi-semiotic expression of emotion in storytelling performances of Cinderella: A focus on verbal, vocal and facial resources. Wollongong: University of Wollongong PhD thesis.Search in Google Scholar

Ariztimuño, Lilián I. 2025. How do we communicate emotions in spoken language? Modelling affectual vocal qualities in storytelling. Journal of World Languages. (Epub ahead of print). https://doi.org/10.1515/jwl-2025-0041.Search in Google Scholar

Ariztimuño, Lilián I., Shoshana Dreyfus & Alison R. Moore. 2022. Emotion in speech: A systemic functional semiotic approach to the vocalisation of affect. Language, Context and Text: The Social Semiotics Forum 4(2). 335–373.10.1075/langct.21012.ariSearch in Google Scholar

Boersma, Paul & David Weenink. 2021. Praat: Doing phonetics by computer (version 6.0.38). https://www.fon.hum.uva.nl/praat/ (accessed 5 November 2025).Search in Google Scholar

Bowcher, Wendy L. & Meena Debashish. 2019. Intonation. In Geoff Thompson, Wendy L. Bowcher, Lise Fontaine & David Schönthal (eds.), The Cambridge handbook of systemic functional linguistics, 171–203. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781316337936.009Search in Google Scholar

Bowcher, Wendy L. & Bradley A. Smith. 2014. Systemic phonology: Recent studies in English. London: Equinox.Search in Google Scholar

Brown, Adam. 2014. Pronunciation and phonetics: A practical guide for English language teachers. London: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Chan, Jeffrey. 2015. Challenges to realizing the convention on the rights of persons with disabilities (CRPD) in Australia for people with intellectual disability and behaviours of concern. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law 23(2). 207–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/13218719.2015.1039952.Search in Google Scholar

Chan, Jeffrey, French Phillip & Webber Lynne. 2011. Positive behavioural support and the UNCRPD. International Journal of Positive Behavioural Support 1(1). 7–13.Search in Google Scholar

Cruttenden, Alan. 2008. Gimson’s pronunciation of English. London: Hodder Education.Search in Google Scholar

Crystal, David & Randolph Quirk. 1964. Systems of prosodic and paralinguistic features in English. The Hague: Mouton de Gruyter.10.1515/9783112414989Search in Google Scholar

Dreyfus, Shoshana. 2007. When there is no speech: A case study of the nonverbal multimodal communication of a child with an intellectual disability. Wollongong: University of Wollongong PhD thesis.Search in Google Scholar

Dreyfus, Shoshana. 2013. Life’s a bonding experience: A framework for the communication of a non-verbal intellectually disabled teenager. Journal of Interactional Research in Communication Disorders 4(2). 249–271. https://doi.org/10.1558/jircd.v4i2.249.Search in Google Scholar

Halliday, Michael A. K. 1967. Intonation and grammar in British English. The Hague: Mouton de Gruyter.10.1515/9783111357447Search in Google Scholar

Halliday, Michael A. K. 1970. Language structure and language function. In John Lyons (ed.), New horizons in linguistics, 140–165. Harmondsworth: Penguin.Search in Google Scholar

Halliday, Michael A. K. 1975. Learning how to mean. London: Edward Arnold.10.1016/B978-0-12-443701-2.50025-1Search in Google Scholar

Halliday, Michael A. K. 2003 [1977]. The context of linguistics. In Jonathan J. Webster (ed.), On language and linguistics: Volume 3 in the collected works of M. A. K. Halliday, 74–91. London: Continuum.Search in Google Scholar

Halliday, Michael A. K. 1984. Language as code and language as behaviour: A systemic-functional interpretation of the nature and ontogenesis of dialogue. In Robin, P. Fawcett, Michael A. K. Halliday, Sydney, M. Lamb & Adam, Makkai (eds.), The semiotics of culture and language, Volume 1: Language as social semiotic, 3–35. London: Frances Pinter.Search in Google Scholar

Halliday, Michael A. K. 2003 [1992]. How do you mean? In Jonathan J. Webster (ed.), On language and linguistics: Volume 3 in the collected works of M. A. K. Halliday, 352–368. London: Continuum.Search in Google Scholar

Halliday, Michael A. K. & William S. Greaves. 2008. Intonation in the grammar of English. London: Equinox.Search in Google Scholar

Halliday, Michael A. K. & Christian M. I. M. Matthiessen. 2014. Halliday’s introduction to functional grammar, 4th edn. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780203783771Search in Google Scholar

Halliday, Michael A. K., Angus McIntosh & Peter Strevens. 1964. The linguistic sciences and language teaching. London: Longmans.Search in Google Scholar

Jorgensen, Mikaela, Karen Nankervis & Jeffrey Chan. 2023. ‘Environments of concern’: Reframing challenging behaviour within a human rights approach. International Journal of Developmental Disabilities 69(1). 95–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/20473869.2022.2118513.Search in Google Scholar

Klotz, Jani. 2001. Denying intimacy: The role of reason and institutional order in the lives of people with intellectual disabilities. Sydney: University of Sydney PhD Thesis.Search in Google Scholar

Knight, Naomi K. 2010. Wrinkling complexity: Concepts of identity and affiliation in humour. In Monika Bednarek & James R. Martin (eds.), New discourse on language: Functional perspectives on multimodality, identity and affiliation, 35–58. London: Continuum.Search in Google Scholar

Lukin, Annabelle & Lucía Inés Rivas. 2020. Prosody and ideology: A case study of one news report on the 2003 invasion of Iraq. Language, Context and Text: The Social Semiotic Forum 3(2). 302–334.10.1075/langct.20006.lukSearch in Google Scholar

Martin, James R. 1992. English text: System and structure. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/z.59Search in Google Scholar

Martin, James R. 2011. Multimodal semiotics: Theoretical challenges. In Shoshana Dreyfus, Susan Hood & Maree Stenglin (eds.), Semiotic margins: Meaning in multimodalities, 243–270. London: Continuum.Search in Google Scholar

Matthiessen, Christian M. I. M. 2007. The multimodal page. In Terry Royce & Wendy L. Bowcher (eds.), New directions in the analysis of multimodal discourse, 1–62. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.Search in Google Scholar

Matthiessen, Christian M. I. M. 2021. The architecture of phonology according to systemic functional linguistics. In Takashi Kazuhiro, Wang Canzhong & Diana Slade (eds.), Systemic functional linguistics, part I: Volume 1 in the collected works of Christian M. I. M. Matthiessen, 288–338. Sheffield: Equinox.Search in Google Scholar

National People with Disabilities and Carer Council (NPDCC). 2009. Shut out: The experience of people with disabilities and their families in Australia. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.Search in Google Scholar

O’Grady, Gerard. 2010. A grammar of spoken English: The intonation of increments. London: Continuum.Search in Google Scholar

O’Grady, Gerard. 2020. Is there a role for prosody within register studies, and if so what and how? Language, Context and Text: The Social Semiotic Forum 2(1). 59–90. https://doi.org/10.1075/langct.00021.ogr.Search in Google Scholar

Pike, Kenneth L. 1943. Phonetics: A critical analysis of phonetic theory and a technic for the practical description of sounds. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.10.3998/mpub.9025Search in Google Scholar

Ramírez-Verdugo, María Dolores. 2021. L2 intonation discourse: Research insights. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781003041351Search in Google Scholar

Roach, Peter, Roger Stibbard, John Osborne, Arnfield Simon & Jane Setter. 1998. Transcription of prosodic and paralinguistic features of emotional speech. Journal of the International Phonetic Association 28(1–2). 83–94. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0025100300006277.Search in Google Scholar

Sinclair, John & Malcolm Coulthard. 1975. Towards an analysis of discourse: The English used by teachers and pupils. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Smith, Bradley A. 2008. Intonation systems and register: A multidimensional exploration. Sydney: Macquarie University PhD thesis.Search in Google Scholar

Tench, Paul. 1976. Double ranks in a phonological hierarchy. Journal of Linguistics 12. 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0022226700004783.Search in Google Scholar

Tench, Paul. 1996. The intonation systems of English. London: Cassell.Search in Google Scholar

Tench, Paul. 2011. Transcribing the sound of English: A phonetic transcription workbook for words and discourse. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511698361Search in Google Scholar

van Leeuwen, Theo. 1992. Rhythm and social context: Accent and juncture in the speech of professional radio announcers. In Paul Tench (ed.), Studies in systemic phonology, 231–262. London: Frances Pinter.Search in Google Scholar

van Leeuwen, Theo. 2022. Multimodality and identity. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781003186625-2-3Search in Google Scholar

Ventola, Eija. 1987. The structure of social interaction: A systemic approach to the semiotics of service encounters. London: Frances Pinter.Search in Google Scholar

Zappavigna, Michele. 2011. Ambient affiliation: A linguistic perspective on Twitter. New Media & Society 13(5). 788–806. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444810385097.Search in Google Scholar

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/jwl-2025-0040).

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter and FLTRP on behalf of BFSU

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.