Abstract

This paper draws on an emerging perspective in Systemic Functional Semiotics on the role of contextual resources in organising language and semiosis. Here we look specifically to resources of mode as they resonate with resources for textual meaning-making in language. Therein we foreground a particular contextual system called juncture. This system concerns the potential to mean through demarcating information into coherent chunks of information. To explore the role of sound in demarcation, we focus especially on resources which we call punctuatives, described in this paper as relatively short, sharp, transient sounds which fall outside standard phonemic models of English. We include both non-pulmonic vocal sounds such as clicks and percussives, embodied beat gestures contacting various kinds of surface, and slightly less transitory sounds such as whistles. These resources reflect the diversity of contexts explored, which include storytelling, classroom discourse and sports coaching. Although the precise sonic resources vary between these contexts, we are able to show that the way the resources are used is relatively stable. Punctuatives are frequently found to co-occur with other semiotic resources which function to organise and chunk segments of spoken text.

1 Sound and text

Whenever we talk or write, we organise the information in our texts in highly systematic ways. Whether intentionally or below the level of consciousness, we readily chunk meanings into coherent bites, link them together and enable a flow or shift of information in text to help underpin a smoothly coherent text. In Systemic Functional Semiotics (SFS), resources for organising text in this regard are often grouped together within what Halliday (e.g. Halliday and Matthiessen 2014) calls the textual metafunction. Textual meanings are pervasive in language and non-linguistic semiosis, but unlike ideational meanings – which consider how we build our experience through, in broad terms, ‘content’ meanings – and to a lesser extent interpersonal meanings – meanings associated with building social interaction and expressing feelings – textual meanings largely work below the level of consciousness and are typically difficult to make explicit. This has meant that resources oriented to textual meaning are often backgrounded in linguistic and semiotic description, or when they are made explicit, are positioned as a kind of ‘add on’ to the more central ideational meanings at play. Nonetheless, in Systemic Functional work textual meanings are in principle just as central to meaning-making as all other meanings and so must be understood if we wish for a comprehensive understanding of language and semiosis.

In this paper we focus on a range of resources that have typically been occluded from linguistic and semiotic description thus far (though not without exceptions, discussed below), that have primarily textual meaning. These resources are short, sharp typically transient though extendable sounds that we will call punctuatives. These resources comprise both non-pulmonic vocal sounds that typically fall outside standard phonemic models of English such as clicks and percussives, sounds generated from embodied beat gestures contacting various kinds of surface and slightly less transitory sounds such as whistles. We will argue that, although the specific resources that are drawn upon vary across contexts, each punctuative discussed in this paper realises general patterns of what Doran et al. (2024) call demarcation – resources to demarcate different chunks of information in the flow of text at different levels of generality.

The bringing together of both vocal sound and non-vocal sound in conjunction with language will be used to support the argument of scholars such as van Leeuwen (1999, 2025) who call for a multimodal phonology, arguing that there is not a sharp distinction between ‘linguistic’ and ‘non-linguistic’ sound, but rather that there is a continuity between semiotic understandings of sound in language and sound in what is normally considered multimodal discourse, ranging from resources such as prosodic voice quality used to build emotion (e.g. Ariztimuño 2024, 2025; Caldwell 2014a, 2014b; Doran et al. 2021; Logi 2025; van Leeuwen 1999, 2025), and more distant resources such as music (e.g. Han 2025) and film sound (Ngo 2025). At the same time, this paper will illustrate that there is not a sharp distinction between the sonic meaning-making that we will describe in this paper and the physical or spatial meaning-making typically associated with gesture. This will align with recent SFS developments in paralinguistic body-language (e.g. Cléirigh 2011; Hood and Hao 2021; Logi et al. 2022; Ngo et al. 2022) and contribute to more fully understanding Abercrombie’s (1965) assertion that sonic meaning-making is a process of ‘phonetic empathy’, whereby the perception of speech is one of a confluence of sound and bodily movement (see van Leeuwen [2025] in particular).

We will begin the paper with a discussion of clicks and percussives in English, drawing on detailed work by Wright (2007, 2011a, 2011b) and Ogden (2013) from a conversation analysis-oriented perspective on phonetics. In particular, we will focus on the role of clicks and percussives in signalling some sort of shift in a conversation such as a new turn. This discussion will lay the foundation for introducing the two main notions that will underpin this paper. The first will be the notion of punctuatives: short, sharp yet potentially extendable sounds that are often used to break up different stretches of text. The term punctuatives will be used to bring together the vocal clicks and percussives described by Wright and Ogden in terms of their articulatory phonetics with non-vocal sounds arising from contact between two physical objects (e.g. a clap, finger click, a pen hitting a desk etc.), whistles such as used in sport and other similar sounds. Wright and Ogden’s descriptions of clicks and percussives will then be interpreted Systemic Functionally in terms of what Doran et al. (2024) and Doran and Ariztimuño (2026) call demarcation – as a resource for breaking up text into coherent informational chunks. Demarcation will be introduced as emanating from Systemic Functional Linguistics’ (SFL) register variable mode and described as a generalised system for interpreting textual usages of a wide range of different language and semiotic features, including punctuatives.

Using these two perspectives, the paper will then step through three distinct contexts to illustrate that punctuatives are pervasive (even if they have not yet been recognised as such) and variable (in terms of their production and their full suite of meanings), but also very similar in terms of their textual use as means of realising demarcation in text. The three contexts that we will focus on are story-telling, classroom teaching and sports coaching. The descriptions in each of these studies arise from distinct projects run by each author, and so the paper reports on parallel observations that have occurred in the course of their studies. In storytelling, arising from a project reported in Ariztimuño (2024, 2025; Ariztimuño et al. 2022), the focus will be on the use of clicks and percussives occurring in what Ariztimuño (2024) describes as rests, to separate different sections of a story or distinguish different characters’ voices. In classroom teaching, arising from a project reported in Hood (2020), Hood and Maggiora (2016), Hood and Hao (2021), Hao and Hood (2019), and Ngo et al. (2022), the focus will be on what we will call contact beats – where a teacher beats their fist, hand, pen or some other object onto another surface in a way that makes a noise in a highly systematic way. In sports coaching, arising from a project reported in Doran et al. (2021), Doran and Ariztimuño (2026), and Doran (2026), the focus will again first consider contact beats, this time in terms of claps and hand slaps on the playing ball, but also whistles. Taken together with the clicks and percussives of conversation, these different contexts will illustrate the significant place that punctuatives hold in our embodied sonic meaning-making and their unity in terms of demarcation. But despite the similarity of their generalised function, these examples will also illustrate that the diversity of punctuatives show variation in terms of marking different sized chunks of text, and in terms of how they couple with other meanings, especially interpersonal meanings. The goal of this paper then is to highlight a broad family of semiotic resources that are typically occluded from our understanding of spoken language but are nonetheless pervasive and richly functional across the contexts of our lives.

2 Clicks and percussives in conversational English

In this section, we will overview the observations of Wright (2007, 2011a, 2011b) and Ogden (2013) in relation to the use of clicks and percussives in English. The function of this overview is to illustrate that there is a regular use of non-phonemic sounds in English (what Pillion [2019] describes as ‘paraphonemic’ sounds) that are used to demarcate sections of talk in interaction. These paraphonemic sounds will then be described from a more generalised sound semiotic perspective as specific examples of a broader class of what we call ‘punctuatives’ that function similarly to chunk spoken text.

Focusing on interactive conversation, Wright observes that rather than being either absent in English by virtue of not being part of the standard phonemic inventory, idiosyncratic in an individual’s speech, or ‘merely’ realising affective reactions, clicks are used systematically in English to support the development of conversation. The main function of clicks, according to Wright (2007: 209) (and further supported by Ogden [2013] who extends this to percussives), is to “demarcate the onset of new and disjunctive sequences”.[1]

Phonetically, clicks are non-pulmonic ingressive stops that arise by virtue of a double closure of the tongue in the mouth – a velaric closure at the back of the mouth and an articulatory closure toward the front of the mouth (e.g. a lateral, alveolar-dental or bilabial articulation) (Catford 1977). Percussives are, following Pike (1943: 103–105), sounds produced by the opening and closing of the articulators themselves – such as the opening and closing of lips that occurs at the beginning of a turn.

Acoustically, where audible, clicks and percussives tend to give short, sharp sounds similar to stops that can only be extended through repetition. Focusing on clicks, Wright (2007) and Ogden (2013) observe that primarily bilabial (ʘ) and alveolar (!) clicks occur to realise demarcative meanings.

One of the main functions that Wright and Ogden observe is what Wright (2007) calls ‘New Sequence Indexing’ clicks, where ‘clicks were found in the disjunctive initiation of a new sequence after a preceding sequence had been collaboratively closed down’. An example given by Wright is as follows, with the New Sequence Initiation click indicated by the bilabial click [ʘ] in bold toward the beginning of the second-last turn:[2]

| N: | you leave Wincanton about three o’clock and get back about two in the morning |

| L: | oh |

| N: | and work full time on top of that |

| L: | oh dear |

| N: | but it’s a lot easier now huh |

| L: | yes I’m sure |

| (0.2) | |

| L: | hm [ʘ] okay well I’ll tell Andrew and uhm (0.3) I’m sure – and he was going to give you a ring anyway before Sunday |

| N: | That’s right yeah |

In this example, the bilabial click works to help realise a shift in the conversation from an interaction focusing on negotiating evaluative meanings about N’s life (– but it’s a lot easier now, – yes, I’m sure), to a future-oriented sequence about speaking to Andrew. As we observe below for storytelling, the click also occurs following a pause.[3]

Notably, the click also occurs before two instances of what Martin (1992), extending Halliday and Hasan’s (1976) description, classes as internal additive connexions: well and ok. As Martin (1992: 219) describes, internal additive connexions are “used to demarcate stages in a text” and are regularly used to frame a new stretch of language in some sense. In this way, these connexions mirror Wright’s description of the function of the bilabial click in the example above and so can perhaps be seen to be working with the click to mark this shift. Wright (2007: 1070) also notes that the stretch of language immediately preceding clicks in her study “are routinely closed down” through a range of devices and that listeners “always accept the disjunctive change in sequence” marked by clicks. All of this suggests that clicks function alongside a range of other linguistic features to demarcate distinct stretches of text in spoken language. Thus in Section 3 below, we will introduce a generalised model of demarcation described by Doran and Ariztimuño (2026) to account for this.

As Ogden (2013) notes, the new sections of talk that clicks mark are often new turns in a conversation. This is illustrated in Example (2) from (Ogden 2013: 307), involving a dialogue between a radio presenter and a listener. In this case, we are concerned with the alveolar click (!) in bold at the start of I’s turn:[4]

| P | what’s on offer at the market then today. |

| I | [!] well we’ve got lots of cheeses |

| we’ve got pancakes | |

| very traditional continental dishes. |

In this instance speaker I once again combines a click [!] with an additive connexion well to demarcate a new stretch of text – in this case a new turn.

Each of Ogden (2013), Wright (2007) and Gil (2013) note that demarcation of new sequences is not the only function that clicks perform in English. Indeed they each note that they often perform an interpersonal function of indicating an affective stance, or what in SFL we can describe as presenting attitude (Martin and White 2005). For instance, Ogden (2013) describes the following alveolar click at the beginning of D’s first turn, as being used to indicate a negative stance – a rejection of M’s negative self-evaluation:[5]

| M | Obviously I didn’t do a good enough |

| D | [!] |

| M | job of raising you. |

| D | bah stop that |

In this instance, Ogden argues that the [!] functions with the full second turn to strongly reject M’s negative self-evaluation, and that it occurs considerably earlier than other non-stance taking clicks so as to reject M’s attitude itself – occurring immediately after didn’t do a good enough. This reflects a broader observation we will show in this paper that percussives, of which these clicks are one example, often do interpersonal work in relation to both evaluative attitude and dialogic speech function, in addition to their textual demarcative work. It is however notable that most of Ogden’s (2013) examples classed as ‘stance-taking’ also occur at the beginning of a new turn or sequence. If they were purely evaluative, we would expect them to be more variably realised in terms of position.[6] This suggests that these types of clicks are multifunctional – that they do both demarcation work and stance-taking work at the same time. This aligns closely with discussion in our examples of punctuatives more generally that while the textual function of demarcation is in some sense the primary or most consistent use of punctuatives, they are often used additionally to signal a range of interpersonal meanings, whether that be in relation to attitude (evaluative stance-taking) or exchange (managing dialogue and interaction).

As a final note in relation to the use of clicks and percussives in English, Ogden (2013) also observes that clicks often occur in conjunction with physical body movement, such as turning a head to remove eye gaze. While Ogden does not give many examples, those that are given suggest that ‘paraphonemic’ clicks work with ‘paralinguistic’ body language to jointly realise meanings. For our purposes, this hints at the embodied nature of such sounds, and the continuum on which they occur from purely sonic, oral sounds to largely non-oral bodily sounds arising from tapping things against surfaces (contact beats). Indeed we will show that contact beats, among other sounds, are regularly used in other contexts in a comparable manner to these clicks in terms of their demarcative function.

In this sense, we can recognise clicks and percussives as one type of what we will call punctuative sounds. Punctuative sounds are relatively short, sharp, transient sounds outside the standard phonemic models of English. Taking a sound semiotic view (or in van Leeuwen’s [2025] terms, a multimodal phonological view), punctuatives include a range of initiations above and beyond purely oral initiations. In addition to non-pulmonic vocal sounds such as clicks and percussives, this includes beat gestures and physical objects contacting various types of surfaces, and slightly less transitory sounds such as whistles. In short, our class of punctuatives aims to bring together similar sounds made across the body so as to show their similarity in function across contexts. In doing so, we aim to contribute to van Leeuwen’s (2025) emphasis on the embodied nature of sound and the continuity between the sounds of language and those typically not considered language.

3 Juncture and demarcation

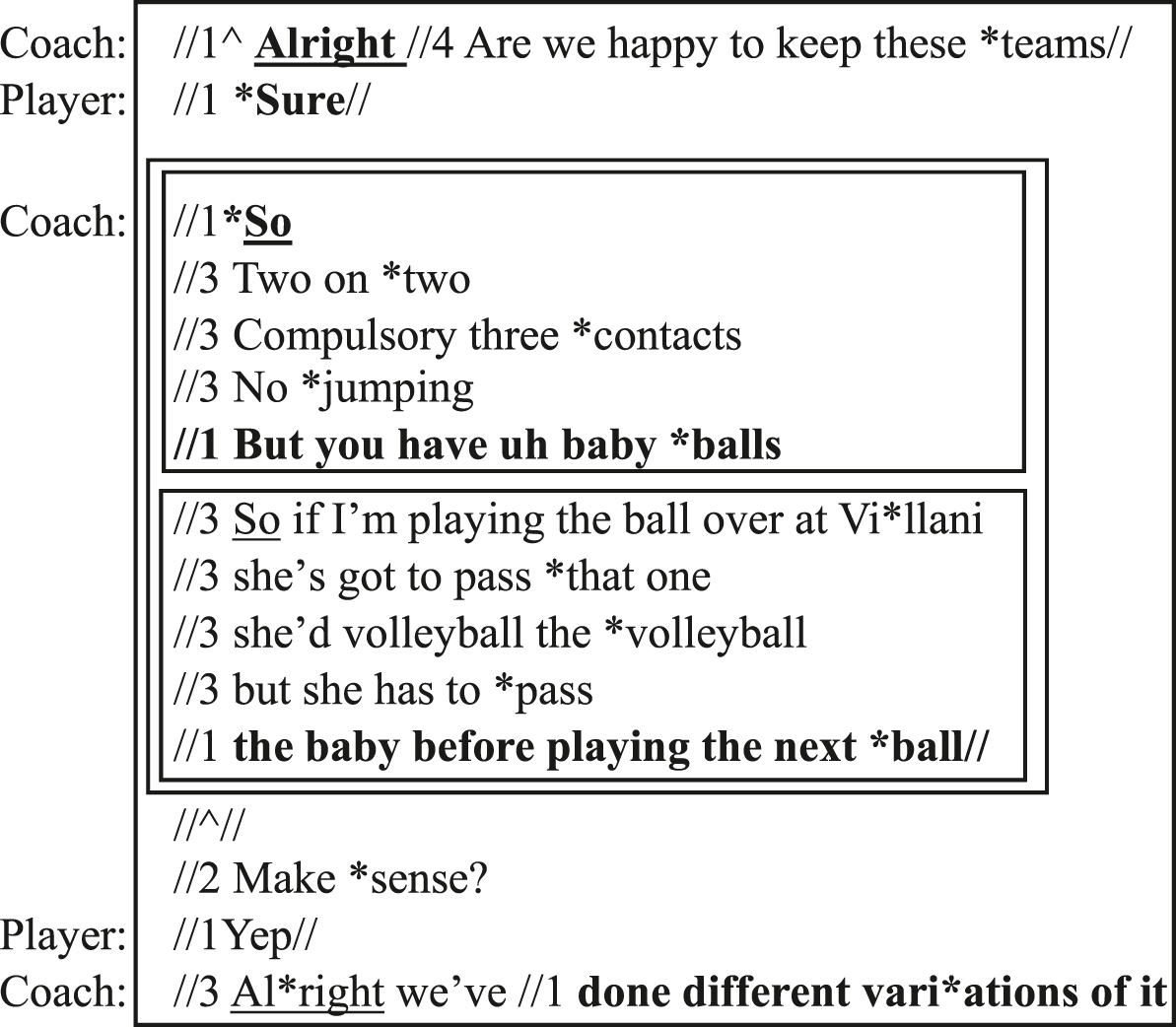

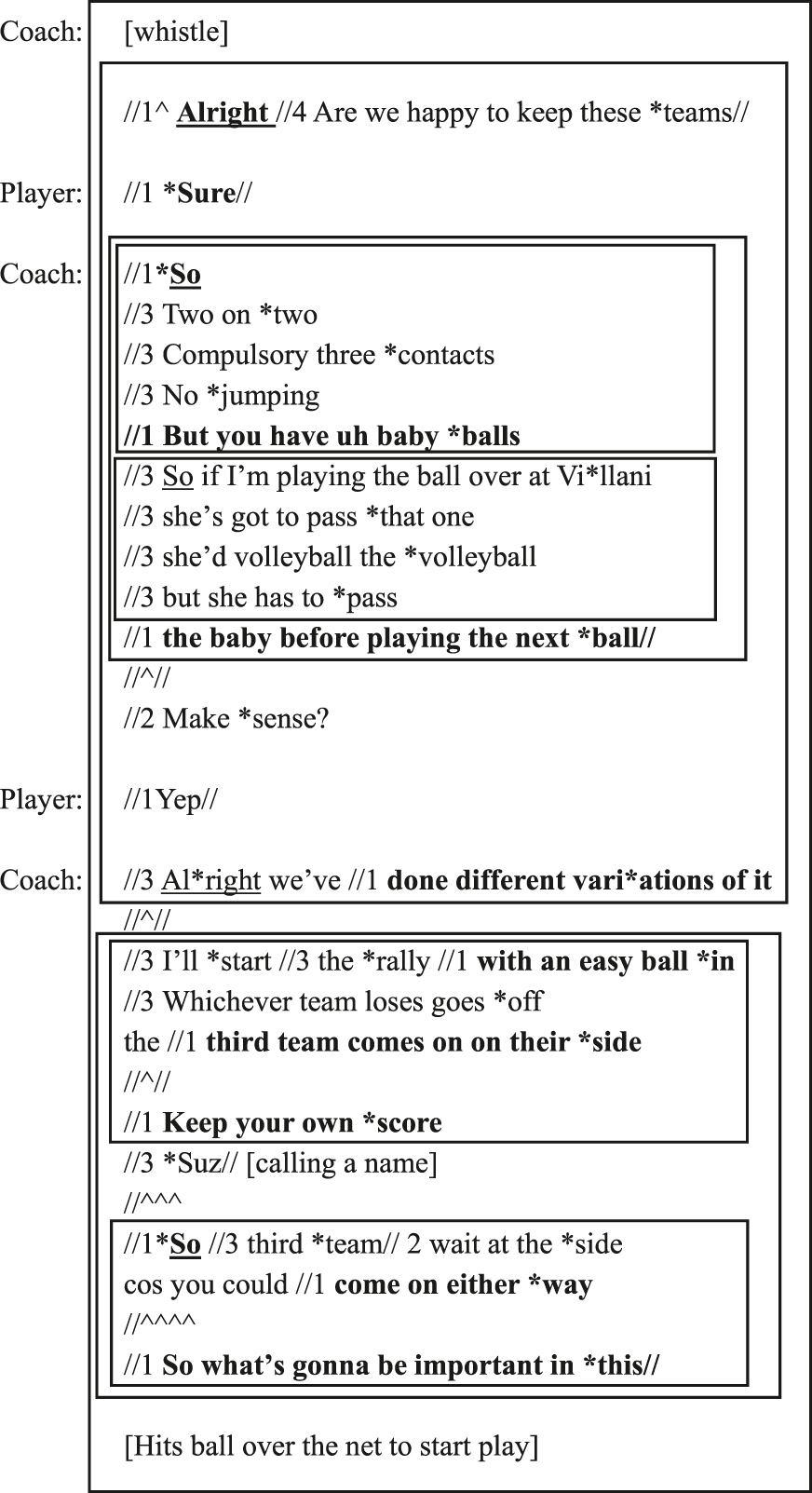

To interpret the function of punctuatives in this paper, we will draw on Doran et al.’s (2024) and Doran and Ariztimuño’s (2026) description of juncture. Juncture describes an abstract set of resources for breaking up text into coherent chunks, either by virtue of demarcating distinct stretches of language or multimodal discourse into distinct chunks or by marking that a chunk of information is being sustained. In spoken language, demarcation and sustaining are regularly realised through phonology – in particular through intonation and tone groups (see van Leeuwen [2025] who illustrates that rhythm also functions to demarcate text). Example (4) from Doran and Ariztimuño (2026: 153) illustrates this through the choice of tone. This text is spoken by a volleyball coach giving instructions to a set of players to start a drill. We have drawn on Halliday and Greaves’ (2008) conventions for marking intonation, whereby tone groups (the main unit of intonation) are marked by double slashes //…//. The choice of tone is marked by numbers at the beginning of the tone group, with asterisks indicating where the main tones occur. The relevant tones for us here are tone 1 (in bold), a falling tone typical of statements, and tone 3 a relatively flat tone, typical of lists. In examples further into the paper, we also mark silent beats within the rhythm of the text (Abercrombie 1965) with a caret ^.

| Coach: | //1*So |

| //3 Two on *two | |

| //3 Compulsory three *contacts | |

| //3 No *jumping | |

| //1 But you have uh baby *balls | |

| //3 So if I’m playing the ball over at Vi*llani | |

| //3 she’s got to pass *that one | |

| //3 she’d volleyball the *volleyball | |

| //3 but she has to *pass | |

| //1 the baby before playing the next *ball// |

In this excerpt, following the opening underlined So on tone 1 (which we will return to below), there is a sequence of relatively flat tone 3s, followed by a tone 1; and then another sequence of tone 3s, culminating in another tone 1. As Halliday notes, tone 3 is typically used to set up paratactic relations between clauses (relations of coordination) and so is often used to build a clause complex,[7] with tone 1 often being used to end the complex. In terms of juncture, the sequence of tone 3s thus sustains a chunk of information, before the tone 1 demarcates the end of the chunk. In Example (4) above, we see that there are two chunks of information that are demarcated by tone 1s and held together by tone 3s: one that gives the rules: So, two on two, compulsory three contacts, no jumping, but you have baby balls, and one that illustrates what this looks like: So if I’m playing the ball over to Villani, she’s got to pass that one, she’d volleyball the volleyball, but she has to pass the baby before playing the next ball.

Importantly, it is not just tone choices that function to demarcate or sustain chunks of information. As Example (4) illustrates, conjunctions realising internal connexion (Halliday and Hasan 1976; Hao 2020; Martin 1992) are often used to demarcate the beginning of chunks. In this case, both chunks begin with so (underlined in Example (4)). Indeed, there is a wide range of resources that typically work together to demarcate or sustain chunks. Doran and Ariztimuño (2026) for example illustrate tone choices, connexion, participant identification and thematic patterns all working together in this regard, with no suggestion that this is an exhaustive list. As we have flagged, the use of punctuatives such as the clicks and percussives of Wright’s (2007) and Ogden’s (2013) studies can be interpreted as functioning in a similar way, especially as their studies showed that they work with internal connexions such as well (though unfortunately their studies did not systematically illustrate rhythm or intonation to help investigate how clicks intersected with these key resources).

A second feature of juncture that is relevant for this paper is the fact that chunks of information can be grouped together to form larger chunks – what Doran and Ariztimuño (2026) call a hierarchy of demarcation. This is illustrated in Example (5), which slightly expands the text from Example (4), adding in a handful of turns that come before and after it. When adding in the text before and after, we see that, although the two chunks from Example (4) do different things (one specifying the rules and the other illustrating them), from another perspective they function together to overview how the training drill will work. We can justify this, among other things, by the fact that the following turns make sense? and alright we’ve done different variations of it refer back to the two chunks together (i.e. through text reference; via ellipsis in make sense? and it in Alright we’ve done different variations of it). In this sense, the two informational chunks of Example (4) come together to comprise another, larger chunk. In addition, the turns before and afterward function to demarcate a larger chunk that sets up the drill, marked at the beginning and end with clauses that use the internal connexion alright.[8] There are thus three layers of demarcation that occur: a layer involving the two chunks in Example (4); a larger layer where these two chunks function together; and finally a layer that includes both of these plus the stretch of text up to the turns that start with alright. This hierarchy is illustrated by the nested boxes in Example (5).

In principle, there can be any number of layers within a text’s hierarchy of demarcation. For example, we could ‘zoom in’ further into Example (5), to consider the fact that each tone group effectively chunks up the text into smaller informational units (as Halliday described it; Haliday and Greaves 2008), which are governed by the system of tonality. We could then zoom in even further to how feet demarcate smaller chunks of information (Abercrombie 1965; van Leeuwen 2025); or even further and look at how syllable structures demarcate smaller chunks of information (Cléirigh 1998). Indeed Catford’s (1977: 226–229) illustration of this type of periodic segmentation through phonetic patterns shows the rich suite of juncture resources at play, phonologically speaking.

And we could of course ‘zoom out’ to longer stretches of text, and how they draw on chunks such as those in Example (5) to build larger chunks of information. As we zoom like this, we can notice that different resources tend to be used to demarcate different sized units in the hierarchy of demarcation. Tone choices, for example, tend to demarcate relatively small chunks of a few clauses at a time, whereas connexion choices can range in their scope. In the example above (and indeed in the larger data set from which it comes), the internal connexion so tends to mark smaller chunks within larger chunks marked by alright. Similarly, although Wright (2007) and Ogden (2013) do not show extended text examples that allow easy interpretation in this regard, it seems that the clicks they studied tend to demarcate chunks of a few clauses at a time (comparable to the sos above).

If we zoom out on the text we looked at in Examples (4) and (5) a little further (shown in Example (6)), we see that other resources are brought in to demarcate larger chunks in this sporting context. This whole text functions as a protocol genre setting up a training drill in volleyball. Immediately after this, the players start playing the drill; immediately before this, the players were playing another drill. The shift between the action of the drills themselves to the talking in this text is marked very clearly – but not by language as such, but by a whistle in the first instance, and the coach hitting a ball over the net to start play in the second instance.

Although they are not language, the choices of whistling and slapping a ball over a net are meaningful, and they function in very similar ways to the linguistic resources that we just described. They demarcate quite distinctly the beginning and end of the instructions for the coming drill.

It is resources such as these that we wish to describe in this paper. We argue that a wide range of these resources occur across contexts, but they have a unity in form – being short, relatively sharp but extendable sounds often occurring jointly with embodied action of a similar nature – and a unity in function, that of realising demarcation. It is these resources that we call punctuatives. The rest of the paper will illustrate such punctuatives by looking at three contexts. First it will look at storytelling, where there is an abundance of clicks and percussives used to demarcate distinctive chunks, either to show a shift in story phases or a change in characters. We will then look at classroom discourse and focus in particular on what will be described as ‘contact beats’, where a teacher contacts a desk with a pen or another physical object to make sound and to demarcate their spoken language. We will finally look again at the sporting context that we have used in this section, exploring in more detail the use of whistles and contact beats onto equipment such as balls.

4 Punctuatives in storytelling: clicks and percussives

The use of clicks and percussives are extensive not only in conversation but also in monologic storytelling performances. To see this, this section will focus on stories told by six professional storytellers (four from the UK and two from Australia) which were recorded as part of a larger study reported in Ariztimuño (2024). While these texts are monologic in the sense of having only one speaker, these storytelling performances engage in a virtual dialogic experience with their potential audience which is mediated by a video recording. This allows for a rather conversational tone not only between the storyteller and their audience but also in the impersonated interactions between the characters in the story (see Logi 2025). The characteristics of this data allow us to explore punctuatives in the semiotic resources at play in the video, including the inherently multi-semiotic spoken language (Matthiessen 2009), together with paralanguage (Martin and Zappavigna 2019; Ngo et al. 2022).

The use of punctuatives was explored in a total of 105 min of video recorded performances of the story of Cinderella which accounted for 13,739 words. We were able to identify 55 punctuatives in the data, out of which clicks were observed to be the most frequent with 38 instances, followed by percussives with 14 instances and finally finger clicks with 3 instances. Like for the punctuatives we have seen thus far in the conversational data, most of the punctuatives in the storytelling data also help realise demarcation across all six storytellers in the dataset. But they do so in slightly different ways.

One regular function of clicks in the storytelling data involves helping mark shifts in the phases of storytelling performances (Ariztimuño 2024; Rose 2020). This is in particular the case when shifting to a new event following a character’s reaction to a previous event. As with the conversational examples we saw above, the clicks in these examples work closely with internal additive connexions that Martin (1992: 218–221) observes are closely oriented toward genre staging, such as ‘now’, ‘anyway’, and ‘well’. Examples (7) and (8) from two different storytellers illustrate this for shifts from reaction phases to event phases. In these instances, they use bilabial clicks shown through the IPA symbol [ʘ]:

| reaction | // 1 ^ But *she knew // 1 ^ that really she was only a *servant. |

| // ^ [ʘ] | |

| event | // 1 *Anyway // 1 ^ it was time for the *dancing, // 1 ^ and the prince took her to the *dance floor |

| reaction | //1^ and the *stepmom / ^ //1 and the *sisters / ^ // 1 hated her *for it. |

| // ^ ^ ^ [ʘ] | |

| event | // 1 There came a *time // 1 ^ when the *prince and the // 4 king of the *land // 1 held a *ball. |

Though a common pattern, clicks are not restricted to marking shifts between phases in these stories. They also regularly occur within phases to help transition the text within smaller chunks. In the following example, for instance, the click works with the internal additive connexion Now, to shift between Cinderella’s perception of her stepmother and stepsisters, and the broader village’s conception of them, within a larger description phase focusing on these characters:

| Narrator: | // 3 Ever since she was *young, |

| // 1 she’d been *picked on by her | |

| // 1 *stepmother and her | |

| // 3 * two | |

| // 1 step *sisters. | |

| // ^ ^ [ʘ] | |

| // 3 *Now, | |

| // 5 ^ a lot of *people in the | |

| // 1 *village | |

| // 1 called them the *ugly sisters |

As the examples thus far show, the use of clicks in this monologic data often parallel the functions of those that occur within turns in the conversational data above. But as we will see, clicks do more than this.

Another common function of clicks in this data involves helping to show shifts in impersonated personae. In these texts, the storytellers commonly impersonate the characters using a range of vocal and facial features (Ariztimuño 2024, 2025; Logi 2025). This means that they often need to shift between multiple personae in quick succession. To support this, storytellers regularly use a click at the point of shift, for example when moving between two characters being impersonated or between the storyteller’s mediation (Ariztimuño 2024) and a character. Example (10) illustrates one storyteller’s shift in characters from impersonating the Fairy Godmother to Cinderella and back to the Fairy Godmother. The storyteller precedes the second change in character with an alveolar click shown in IPA (International Phonetic Alphabet) with the symbol [!]. This click appears not only to separate the character’s impersonation but also to be reinforcing the Fairy Godmother’s determination to get Cinderella to the ball. Here we have marked the personae that the storyteller is using in the left-hand column, but it should be emphasised that it is the same speaker throughout.

| Fairy Godmother: | // 1 ^ Would you like to go to the *ball my dear? |

| Cinderella: | // 1 *Yes, |

| // 1 ^ yes *please. | |

| // 1 *Please. | |

| Fairy Godmother: | // 2 [!] ^Al*right then, |

| // 3 run to the *garden | |

| // 1 ^ and fetch a *pumpkin. |

In Example (11), by contrast, the storyteller shifts between impersonating Cinderella’s Stepmother and intervening as the storyteller to share her own perspective and evaluation of the situation. When she shifts from being the Stepmother to being the Storyteller, she marks this with a two-beat silent rest and a bilabial click. This stretch occurs immediately after it is explained the Stepmother makes Cinderella do ‘all the most menial tasks around the house’:

| Stepmother: | // 1 ‘Cinderella, scour the *dishes, |

| // 1 Cinderella, wash the *floor, | |

| // 1 Cinderella, do the *laundry, | |

| // 1 Cinderella, clean the *boots, | |

| // 3 Cinder*ella, | |

| // 3 Cinder*ella, | |

| // 1 Cinder*ella.’ | |

| //^ ^ [ʘ] | |

| Storyteller: | // 13 *Poor Cinder*ella. |

The use of clicks to shift personae is a regular feature of these texts across storytellers, as illustrated by Example (12), spoken by a different storyteller shifting from their Narrator personae to impersonating the Fairy godmother:

| Narrator: | // 2 And she * did |

| // 1 Cinderella’s make up all by her*self. | |

| // ^^^ [ʘ] | |

| Fairy godmother: | //1 ‘*Now, |

| //1 you can go to the *ball, Cinderella,’ | |

| //1 said the fairy *godmother. |

Percussives in this context, while limited to fewer instances (14 cases), appear to perform similar functions to clicks. Examples (13) and (14), for instance, show two storytellers who use an alveolar percussive formed by the separation of the articulators, which, following Ogden (2013) we shall transcribe as [t↓], and a bilabial percussive, which, again following Ogden (2013), we will transcribe as [p↓].[9]

| Narrator: | // 1 ^ and then off they went to the *ball |

| // ^ [t↓] | |

| // 5 ^ and they left her there by the *fire | |

| // 5 ^ in the *cinders. |

| Narrator: | // 4 ^ for he *said, |

| Prince: | // 4 ^ ‘Whoever’s foot fits this *slipper, |

| // 1 I will *marry her. | |

| // 3 ^ No matter who she *is, | |

| // 1 ^ I will *marry her.’ | |

| // ^ ^ [p↓] | |

| Narrator: | // 1 ^ And so of *course, |

| // 4 ^ e*ventually, | |

| // 3 ^ he *got | |

| // 1 ^ to the house of the stepmother, the stepsisters and Cinder*ella. |

The examples illustrate the use of percussives to demarcate smaller chunks of events within one event phase (Example (13)) and to separate a character’s voice from that of the narrator (Example (14)). It is interesting to notice how these percussives work together with additive conjunctions, which distinguish different stretches of language, while clearly linking them as well. This could suggest that they work to demarcate relatively small chunks, while at the same time indicating that a larger chunk is being sustained. As noted above, it is likely that although each of the punctuatives described in this paper do similar demarcative work, they can be distinguished by, among other things, the size of the chunks which they demarcate. In this sense, it appears that percussives tend to demarcate smaller chunks than clicks, perhaps also reflecting their less intrusive acoustic form (in terms of, say, loudness and intensity).

Extending beyond vocal sounds, the storytellers also make use of embodied resources for similar demarcative functions. In the data examined here, there are three clear examples of this when a storyteller snaps his fingers – what we will call here a finger click. Example (15) illustrates the use of the finger click to demarcate a shift from a negative evaluative comment from the storyteller’s perspective to a direct address to his potential audience where he anticipates a positive outcome for Cinderella. We have marked the finger click with  .

.

| Storyteller: | // 1 Poor Cinder*ella |

// ^ [ ] ] |

|

| // 3 *But | |

| // 4 do you *know |

We have ended this section with the embodied finger click so as to illustrate its parallels with the vocal punctuatives – clicks and percussives – in conversation and storytelling. As noted above, following Abercrombie (1965), vocal sound is not purely sonic – it is the confluence of both embodied physical action (e.g. of the articulators) and the sound that is produced. For vocal sounds, this is more easily seen for percussives than clicks, where the sounds are those produced by the movement of the articulators themselves. But if we consider vocal sounds in these terms, then there is no large step toward considering physical actions such as fingers clicks along these lines – there is a confluence of sound and body movement, it is just that the ‘articulators’ and ‘initiation’ have shifted from the vocal tract to the hand. In the following section we will see that this shift toward sonic and punctuative meaning-making of the hand is just as systematic and pervasive as the vocal punctuatives we have seen so far. We will do this by shifting from storytelling to classroom teaching.

5 Punctuatives in classroom teaching

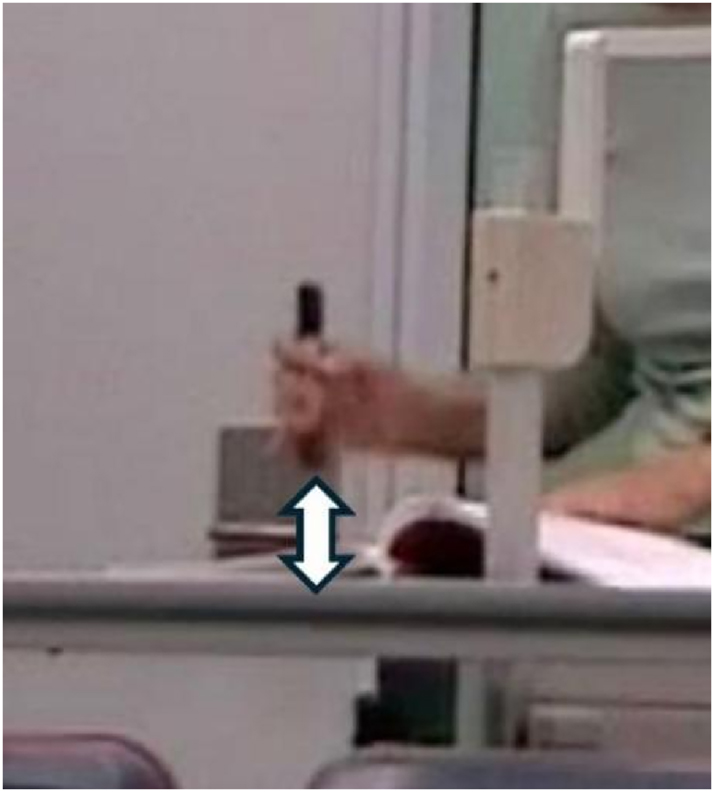

In this section we focus on a category of non-vocal punctuative sounds generated through embodied beat gestures as they make contact with various kinds of surface, referred to as contact beats. The key question addressed is the semiotic potential of these resources. More specifically, we look to identify ways in which the non-vocal sounds generated by contact beats play a role in demarcating chunks of information in the flow of spoken language in pedagogic settings.

Analyses of audio-visual data from tertiary-level classroom teaching and face-to-face lecturing reveal ways in which embodied contact beats are implicated in the production of non-vocal sounds. These include (1) the tapping of a held object onto a hard surface, (2) the pounding of a fisted hand (with or without a held object) against an open supine palm, and (3) a singular horizontal clapping of hands. Each of these contact beats synchronise with the rhythm of English, occurring on the beat (typically on a silent beat). This indicates their integration with the spoken language, rather than being an independent, free-wheeling set of semiotic choices. As will be discussed, the nature of the embodied actions and the impacted surfaces can generate non-vocal sounds of varying loudness.

Throughout this section, illustrative instances of each type of contact beat will be shown visually in relation to phonological transcriptions of its co-textual speech. In these examples, clapping is represented as an emoji clap [ ], tapping as a pen-holding emoji [

], tapping as a pen-holding emoji [ ], and pounding as an emoji hammer [

], and pounding as an emoji hammer [ ]. Given that the non-vocal sounds are generated by what is referred to as a type of beat, it is unsurprising to find that their convergence with the rhythms of spoken text leads to a degree of textual prominence.

]. Given that the non-vocal sounds are generated by what is referred to as a type of beat, it is unsurprising to find that their convergence with the rhythms of spoken text leads to a degree of textual prominence.

We will begin with tapping, which involves a teacher tapping a pen or other object on a table. This is illustrated in Figure 1, where a teacher holds a marker pen in the fist of her right hand, and contacts it with the hard surface of a desktop. The inserted bi-directional arrow visualises the embodied activity of tapping.

Tapping contact beat.

This instance occurs at the end of a long stretch in which the teacher is explaining the construction of a paragraph in a language lesson, shown in Example (16a). In this example, the tapping beat is represented by a pen-holding emoji [ ]. Like with other instances we have seen, the tap occurs following the end of a chunk indicated by a falling tone 1 and a series of silent beats, and just before an additive internal connexion signifying a new chunk – in this case, okay.

]. Like with other instances we have seen, the tap occurs following the end of a chunk indicated by a falling tone 1 and a series of silent beats, and just before an additive internal connexion signifying a new chunk – in this case, okay.

| […] |

| //3 looking at / those / *words |

| //3 ^ we can / *see |

| //1 ^ / how the / paragraph’s co-/ *nnected |

| //3 ^ / and we can / *see |

| //1 ^ / what it’s a-/ *bout |

| / ^ / ^ / ^ / ^ |

| //1 okay so / there’s a repe-/ *tition if you / like |

| //2 *yeah |

| //1 there’s a repe-/ tition of / ^ / ^ of / those / ^ of / those / *themes |

| / ^ / ^ / ^ / ^ |

/ ^[ ] ] |

| //1 ^ o / *kay |

| / ^ / ^ / ^ / ^ / ^ |

As discussed by Martin (1992: 219), okay is one of a small handful of internal additive connexions that function to “organis[e] discourse on a global level […] fram[ing] a text generically, with a schematic structure” such as marking “the opening and closing of a step in a lecture”. In this sense, okay typically demarcates larger chunks than we saw in the conversation and storytelling data above. The immediate tap before the okay, following as it does a number of silent beats, strongly suggests that the two work together, with the tap in particular functioning to highlight the demarcation underway. In addition by using a tap, rather than, say, a click or percussive, the teacher is perhaps iconically reflecting the size of this demarcation by virtue of it generating the loudest sound of the punctuatives identified in this paper thus far due to the contact of a hard object on a hard surface.

Indeed in this instance, the significance of such a tap is apparently recognised by a student as suggesting that they have come to a break in the lesson. We can see this by the fact that immediately following the example above, the teacher responds to a student by saying:

| //2 what did you / *say |

| //2 *break time |

| / ^ / ^ |

| //2 did I / *hear that |

| [Omitted here is a brief playful dialogic exchange with one of the students, after which the teacher continues] |

| //1 o-kay |

| //5 ^ it / is nearly / break time / *actually |

| //3 ^ we’re / gonna stop / *there |

| //3 ^ we’re /gonna look at / ^ / language of com-/ *parison again |

| //1 ^ and / then we’re gonna / do a little / practice /*writing |

| //3 ^ so let’s / take a quick / *break |

| //2 ^ al / *right |

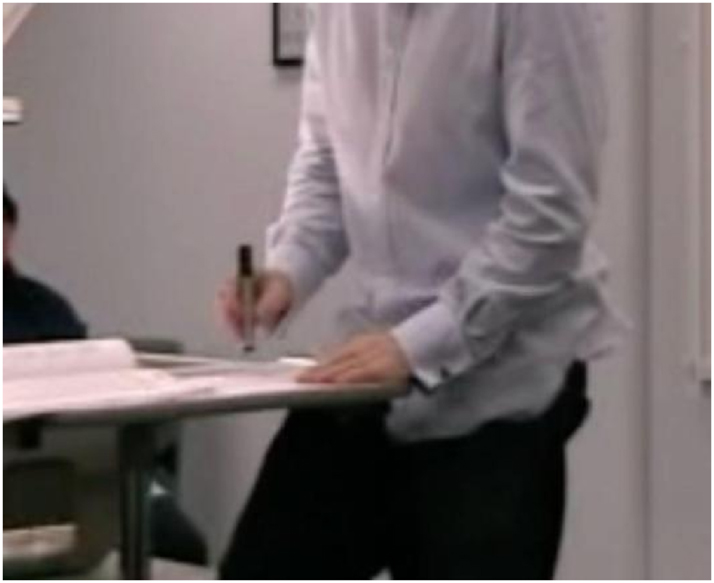

Although this example shows an instance of a large chunk being demarcated by a tap, Example (17) shows that tapping beats do not always demarcate as large a chunk. In this example, a different teacher uses a pen to produce two quick taps in succession that together fit within a silent beat. Figure 2 illustrates the tapping that occurs. As in Figure 1, the teacher in Figure 2 holds a marker pen in the right hand and makes contact with the hard surface of a desktop. However the two examples are contrasted by virtue of the shape of the hand. In Figure 2, the marker pen is held between fingers and thumb, whereas in Figure 1, it is held in a fist. Although both allow for tapping, the different ways in which the pens are held enable differences in the force applied to the table and thus the relative loudness of the beat. In Figure 1 above the fist produces a significantly louder sound than in Figure 2, and as we saw, it functions to demarcate a large chunk of the text. The softer tapping of Figure 2, by contrast, demarcates a smaller chunk. This is illustrated in Example (17), which shows the spoken co-text in which the tap occurs.

Tapping contact beat.

//3 now we’re / gonna / ^[ ] con-/ *tinue with these ones ] con-/ *tinue with these ones |

| //3 after the / *break |

In this instance, a double tap [ ] inserted into the text is rapidly produced within a singular silent beat. In doing so, it functions to place a marker about the oncoming proposal of continue with these ones after the break. This both brackets it off informationally from the previous text, and supports the textual prominence of both ‘con*tinue’ and ‘after the *break’.

] inserted into the text is rapidly produced within a singular silent beat. In doing so, it functions to place a marker about the oncoming proposal of continue with these ones after the break. This both brackets it off informationally from the previous text, and supports the textual prominence of both ‘con*tinue’ and ‘after the *break’.

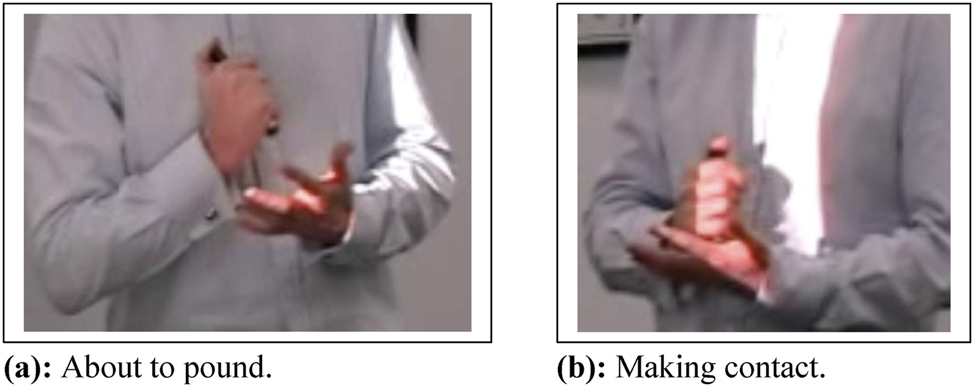

Contrasting with the tapping of hard objects onto a desk are instances where teachers pound a fist into the open palm their other hand, with or without a held object. The images in Figure 3(a) and (b) capture an example of this type of pounding of a fist into the open palm of a hand.

Pounding a fist into the open palm of a hand.

The generated sound arises due to contact between the fisted hand and the surface of the supine palm. As such, it is low in volume yet typically still audible in a classroom space where students are in relative proximity to the teacher. This is less so in a larger space, but is compensated for by the visible forceful actions in the enactment of the contact beats – actions recognised as making noise.

Example (18) illustrates multiple instances of pounding contact beats in a lecturer’s speech, indicated by hammer emoji [ ].

].

| //1 ^ we’ll need to go / *over that / ^ / ^ |

//1 later to-/*day[ ] ] |

//3 ^ al-/*right[ ] ] |

/ ^[ ] / ^[ ] / ^[ ] ] |

| //3 ^ well I / think we might / *finish there |

| //3 just take a / *break |

In this instance, the discourse of the first two tone groups signal a forthcoming shift in the content of a lesson – from a chunk of information already discussed (‘that’), to one to be reinforced (‘go over’) at a future time (‘later today’). The first instance of the non-vocal sound of pounding [ ] converges with the tonic prominence in the bolded syllable of ‘to*day’. Another syncs with the tonic prominence bolded in ‘al-/*right[

] converges with the tonic prominence in the bolded syllable of ‘to*day’. Another syncs with the tonic prominence bolded in ‘al-/*right[ ]’, an additive connexion that we have already seen frequently associates with the boundary of a chunk. An additional two pounding contact beats in sync with the rhythm of two silent beats, further support a pending demarcation. This is also supported ideationally, through the naming of a likely occurrence (‘finish’) and an activity entity (‘a break’) in the final two tone groups.

]’, an additive connexion that we have already seen frequently associates with the boundary of a chunk. An additional two pounding contact beats in sync with the rhythm of two silent beats, further support a pending demarcation. This is also supported ideationally, through the naming of a likely occurrence (‘finish’) and an activity entity (‘a break’) in the final two tone groups.

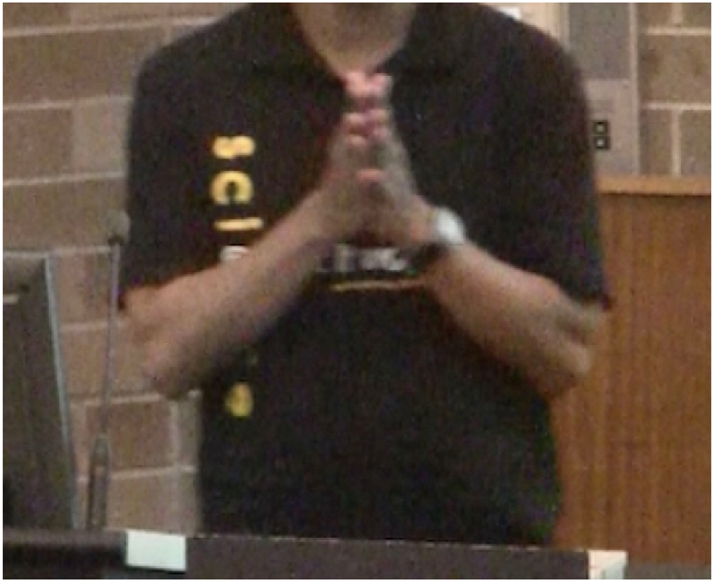

The final contact beat to discuss in this section involves a clap – a not uncommon feature of the tertiary lecturing that occurs in this dataset. Figure 4 captures the moment a biochemistry lecturer claps his hands.

Clap contact beat.

This clap occurs across a short episode of spoken discourse, shown in Example (19).

| //1 okey / *dokey |

^[ ] ] |

| / ^ / ^ / ^ / ^ |

| //1 ^ a / little / early but we / might get / *started // |

As with previous examples, the clap in Example (19) occurs in conjunction with the additive connexion //1 okey / *dokey //, in this case a colloquial expression which supports an interpretation akin to ‘readiness’. This is followed by the coded clapping sound  positioned as convergent with the rhythm of a silent beat. Here, the clap (plus okey dokey and the silent beats) functions to demarcate a boundary between a sustained chunk of student chatter as they settle into the lecture theatre, and the commencement of the lecture proper. This demarcation is of a significantly larger-sized chunk of speech than we saw with the clicks and percussives in previous sections, marking as it does a shift from the pre-lecture gathering to the lecture-proper (i.e. marking the beginning of the coming hour of relatively monologic speech). This clap perhaps best illustrates the tendency we noted above, where vocal punctuatives (percussives and clicks) tend to demarcate smaller, localised chunks of information (with the softer percussives tending to mark smaller chunks than the slightly louder clicks), and the louder and more bodily-oriented contact beats tend to demarcate larger chunks of text – in this case, a whole lecture.[10]

positioned as convergent with the rhythm of a silent beat. Here, the clap (plus okey dokey and the silent beats) functions to demarcate a boundary between a sustained chunk of student chatter as they settle into the lecture theatre, and the commencement of the lecture proper. This demarcation is of a significantly larger-sized chunk of speech than we saw with the clicks and percussives in previous sections, marking as it does a shift from the pre-lecture gathering to the lecture-proper (i.e. marking the beginning of the coming hour of relatively monologic speech). This clap perhaps best illustrates the tendency we noted above, where vocal punctuatives (percussives and clicks) tend to demarcate smaller, localised chunks of information (with the softer percussives tending to mark smaller chunks than the slightly louder clicks), and the louder and more bodily-oriented contact beats tend to demarcate larger chunks of text – in this case, a whole lecture.[10]

6 Punctuatives in sports coaching

With the discussion so far illustrating the continuity between clicks and percussive vocal punctuatives and non-vocal contact-beat punctuatives, we can return to our sports coaching example given in Section 2 above. Like in the classroom, claps and a range of other contact beats are relatively common occurrences in the sport data reported in Doran et al. (2021) and Doran and Ariztimuño (2026), but here we want to focus on the examples we saw above that demarcate the beginning and end of the training drill set up in beach volleyball, replayed as Example (20). Before and after this stretch of language, the players are doing the actual physical actions of the training drills, where language is dependent on the action (what in SFL is often called ‘language-in-action’ (Martin 1992), ‘language-as-ancillary’ (Halliday and Hasan 1985) or what van Leeuwen (2025) suggests could be called ‘para-actional’ language; see Doran et al. 2021) in contrast to paralinguistic action. What marks the shift from the initial action to this chunk of language is a whistle (which, in lieu of a whistle emoji, we have marked with  ), and what marks the shift from the text to the next phase of action is the coach underarm hitting the ball over the net (marked with

), and what marks the shift from the text to the next phase of action is the coach underarm hitting the ball over the net (marked with  ).

).

| Coach: | [ ] ] |

| //1^ Alright //4 Are we happy to keep these *teams// | |

| Player: | //1 *Sure// |

| Coach: | //1*So |

| //3 Two on *two | |

| //3 Compulsory three *contacts | |

| //3 No *jumping | |

| //1 But you have uh baby *balls | |

| //3 So if I’m playing the ball over at Vi*llani | |

| //3 she’s got to pass *that one | |

| //3 she’d volleyball the *volleyball | |

| //3 but she has to *pass | |

| //1 the baby before playing the next *ball// | |

| //^// | |

| //2 Make *sense? | |

| Player: | //1Yep// |

| Coach: | //3 Al*right we’ve //1 done different vari*ations of it |

| //^// | |

| //3 I’ll *start //3 the *rally //1 with an easy ball *in | |

| //3 Whichever team loses goes *off | |

| the //1 third team comes on on their *side | |

| //^// | |

| //1 Keep your own *score | |

| //3 *Suz// [calling a name] | |

| //^^^ | |

| //1*So //3 third *team// 2 wait at the *side | |

| cos you could //1 come on either *way | |

| //^^^^ | |

| //1 So what’s gonna be important in *this// | |

[ ] ] |

While clearly doing demarcation work, each of these instances are at the boundary of what we have described as punctuatives in this paper. In terms of the whistle, it of course primarily orients toward producing a loud sound and works to begin this stretch (and in other instances, end a stretch of language or play). However unlike the punctuatives in this paper, it is not necessarily short and sharp – it is in fact potentially considerably extendable. This extension allows it to be manipulated into different tones and rhythms, signifying different meanings (though each doing demarcation). In the dataset for this study, the unmarked whistle choice is a relatively short sharp bleet, similar to the other punctuatives; this is what occurs in Example (20). But an alternative choice is a longer whistle that begins with a high intensity burst, lowering in intensity through the middle of the whistle, and then raising again at the end (like an extended tone 4 in English). This whistle is typically used to end things – not just small chunks, but whole training sessions or games. For example, in a training set in volleyball, each point will typically be ended by the unmarked whistle, but the end of the set itself will often be marked with this extended whistle, signifying that players should leave the court. A third choice in whistle involves sudden but repeated high intensity blasts. This whistle is used to indicate urgency in ending whatever is going on, often due to some sort of danger. In volleyball for instance it can occur if a ball is rolling along a court under where someone is jumping (a very dangerous situation). The significance of these choices for us is that this highlights that while punctuatives show some unity in terms of their form (being non-phonemic combinations of sound and bodily action) and some unity in their meaning in terms of demarcation, they do allow for significant variation within these parameters. Indeed we have already seen this in the difference between the stretches typically demarcated by percussives, clicks and contact beats.

Looking now at the coach hitting the ball over the net at the end, it is arguable that this should not be counted as ‘meaningful sound’ (as a classification as a punctuative would suggest), but rather simply be seen as non-semiotic bodily action (what Martin and Zappavigna [2019] call ‘somatic’ behaviour). That is, we should simply consider it part of the chunk of action that occurs after the language and leave it out of a sound semiotic consideration. This, however, pushes to one side its clear functioning in the linguistic text to demarcate the boundary of the set-up of the training drill and its shift to the playing itself (Doran and Ariztimuño 2026). That is, as we have already noted, it clearly realises demarcation and so is best seen as semiotic. In addition, a view of it as purely action that occludes its sound is comparable to a view of clicks and percussives that view them as only sound without a consideration of the body movement. Such a view sheers off understandings of these clicks and percussives from the finger clicks and contact beats we have described in this paper. This is a view we have tried to argue against throughout this paper – that when viewed as a confluence of sound and body movement, there is a continuity between clicks, percussives, finger clicks, taps, pounds, claps and in this case, the slapping of the ball over the net. Being a shift toward language-in-action, where language (and broader semiosis) is dependent on the action rather than vice versa, it is not surprising that the bodily movement is in some sense primary in this instance; but it still functions with the sound. But the final reason for considering the coach hitting the ball over the net is that that coach could alternatively have simply thrown the ball over the net – something that would have produced much less sound (and indeed would likely have produced a more accurate throw). There has thus been a choice to slap the ball over the net and thus produce sound – choice being a key feature of semiosis in the Systemic Functional interpretation. Thus, when looking from ‘above’ in Halliday’s terms, slapping the ball over the net realises meaning in terms of demarcation; from below, it brings together sound and bodily action; and from ‘around’ it signifies one of at least two possible choices. It is thus meaningful, and in our terms is considered a punctuative.

7 Punctuatives in a multimodal phonology

We have spent time stepping through the reasons why we consider the coach hitting the ball over the net as meaningful as it goes to the heart of the argument in this paper, and indeed in research that probes the boundary between meaning and behaviour. Our argument in this paper is that a broad conception of meaning as indicated by our focus on demarcation, allows us to bring in a wider range of things as meaningful than we otherwise could, and to understand their systematic use across contexts. This aligns with van Leeuwen’s (2025) argument for a multimodal phonology and Abercrombie’s (1965) for a ‘phonetic empathy’. But it also provides a pathway for understanding physical behaviour as meaning. Just as a student in Section 5 recognises a tap of a pen on a desk as indicating that it was time for a break in a class; players on a sports field can recognise bodily movements of their coach or fellow/opposition players as indicating actions that are about to occur (a pass, a hit, a side-step, etc.) (Doran et al. 2026). Being able to interpret sound and behaviour in terms of its oppositions between different choices, its physical/sonic manifestation and its realisation in terms of broader patterns of meaning, allows us to build an expansive semiotics that brings together both primarily linguistic sources of meaning with primarily physical, behavioural sources of meaning.

We have also seen that although punctuatives do similar things in similar ways, they also show significant variation. They vary of course in terms of their ‘articulation’ and ‘initiation’ and thus their sound and bodily movement, but they also vary in terms of their function. We have noted multiple times that there is a tendency for the softer, less intrusive vocal sounds to demarcate smaller chunks (with percussives typically demarcating smaller chunks than clicks), and the louder, non-vocally produced punctuatives such as the contact beats to demarcate larger chunks. But we have also seen that most of these punctuatives are multi-functional. In the case of contact beats, we saw that in addition to demarcating chunks, a number of these marked informational prominence; in the case of clicks and percussives, we saw that in monologue, some tended to shift story phases, while others tended to mark the difference between personae, and in dialogue, they often function to mark shifts in dialogic exchange; and in the case of whistles and the ball being hit over the net, these additionally mark interpersonal proposals to stop or start play. The punctuatives that we have put forward in this paper are diverse and do a wide range of things – things that with more exploration, we can begin to unravel.

-

Research ethics: For the sports coaching data, ethics approval was obtained from the University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee (Project number 2019/783). For the storytelling data, ethics approval was obtained from the University of Wollongong Social Sciences Human Research Ethics Committee (Project number 2020/466). For the classroom data, ethics approval was obtained from the University of Technology Sydney.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

References

Abercrombie, David. 1965. Studies in linguistics and phonetics. London: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Ariztimuño, Lilián I. 2024. The multi-semiotic expression of emotion in storytelling performances of Cinderella: A focus on verbal, vocal and facial resources. Wollongong: The University of Wollongong PhD thesis.Search in Google Scholar

Ariztimuño, Lilián I. 2025. How do we communicate emotions in spoken language? Modelling affectual vocal qualities in storytelling. Journal of World Languages. (Epub ahead of print). https://doi.org/10.1515/jwl-2025-0041.Search in Google Scholar

Ariztimuño, Lilián I., Shoshana Dreyfus & Alison R. Moore. 2022. Emotion in speech: A systemic functional semiotic approach to the vocalisation of affect. Language, Context and Text: The Social Semiotics Forum 4(2). 335–374.10.1075/langct.21012.ariSearch in Google Scholar

Caldwell, David. 2014a. The interpersonal voice: Applying appraisal to the rap and sung voice. Social Semiotics 24(1). 40–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10350330.2013.827357.Search in Google Scholar

Caldwell, David. 2014b. A comparative analysis of rapping and singing: Perspectives from systemic phonology, social semiotics and music studies. In Wendy L. Bowcher & Bradley Smith (eds.), Recent studies in systemic phonology, vol. I: Focus on the English language, 271–299. London: Equinox.Search in Google Scholar

Catford, John C. 1977. Fundamental problems in phonetics. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Cléirigh, Chris. 1998. A selectionist model of the genesis of phonic texture: Systemic phonology & universal Darwinism. Sydney: The University of Sydney PhD thesis.Search in Google Scholar

Cléirigh, Chris. 2011. Gestural and postural semiosis: A systemic-functional linguistic approach to “body language”. Unpublished manuscript.Search in Google Scholar

Doran, Y. J. 2026. Using systemic functional linguistics to explore the language of sport. In Kieran File, David Caldwell & Lindsey Meân (eds.), The Bloomsbury handbook of language and sport. London: Bloomsbury.Search in Google Scholar

Doran, Y. J. & Lilián I. Ariztimuño. 2026. Demarcating information: Setting up drills and giving instructions in sport. In Andrew S. Ross, David Caldwell & Y. J. Doran (eds.), Language in sport: Real-time talk in training and games, 141–166. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781003458661-8Search in Google Scholar

Doran, Y. J., David Caldwell & Andrew S. Ross. 2021. Language in action: Sport, mode and the division of semiotic labour. Language, Context & Text: The Social Semiotics Forum 3(2). 274–301.10.1075/langct.20009.dorSearch in Google Scholar

Doran, Y. J., David Caldwell & Andrew S. Ross. 2026. Language in sport: Wherefore and where to? In Andrew S. Ross, David Caldwell & Y. J. Doran (eds.), Language in sport: Real-time talk in training and games, 228–235. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781003458661-12Search in Google Scholar

Doran, Y. J., J. R. Martin & Michele Herrington. 2024. Rethinking context: Realisation, instantiation and individuation in systemic functional linguistics. Journal of World Languages 10(1). 177–220. https://doi.org/10.1515/jwl-2023-0051.Search in Google Scholar

Gil, David. 2013. Para-linguistic usages of clicks. In Matthew S. Dryer & Martin Haspelmath (eds.), The world atlas of language structures online. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. https://wals.info/chapter/142 (accessed 10 October 2025).Search in Google Scholar

Halliday, M. A. K. & Ruqaiya Hasan. 1976. Cohesion in English. London: Longman.Search in Google Scholar

Halliday, M. A. K. & Ruqaiya Hasan. 1985. Language, context, text: Aspects of language in a social semiotic perspective. Geelong: Deakin University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Halliday, M. A. K. & Christian M. I. M. Matthiessen. 2014. Halliday’s introduction to functional grammar, 4th edn. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780203783771Search in Google Scholar

Halliday, M. A. K. & William S. Greaves. 2008. Intonation in the Grammar of English. London: Equinox.Search in Google Scholar

Han, Joshua. 2025. On the politics of “sound studies” and “music theory” and the implications of its importation into research on sound and music semiotics. Journal of World Languages. (Epub ahead of print). https://doi.org/10.1515/jwl-2025-0049.Search in Google Scholar

Hao, Jing. 2020. Analysing scientific discourse from a systemic functional perspective: A framework for exploring knowledge-building in biology. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781351241052Search in Google Scholar

Hao, Jing & Susan Hood. 2019. Valuing science: The role of language and body language in a health science lecture. Journal of Pragmatics 139. 200–215.10.1016/j.pragma.2017.12.001Search in Google Scholar

Hood, Susan. 2020. Live lectures: The significance of presence in building disciplinary knowledge. In J. R. Martin, Karl Maton & Y. J. Doran (eds.), Accessing academic discourse: Systemic functional linguistics and legitimation code theory, 211–235. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780429280726-8Search in Google Scholar

Hood, Susan & Jing Hao. 2021. Grounded learning: Telling and showing in the language and paralanguage of a science lecture. In Karl Maton, J. R. Martin & Y. J. Doran (eds.), Teaching science: Knowledge, language, pedagogy, 226–256. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781351129282-13Search in Google Scholar

Hood, Susan & Patricia Maggiora. 2016. A lecturer at work: Language, the body and space in the structuring of disciplinary knowledge in law. In Helen de Silva Joyce (ed.), Language at work: Analysing language use in work, education, medical and museum contexts, 108–128. Newcastle upon Tyne, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.Search in Google Scholar

IPA [International Phonetic Association]. 1999. Handbook of the international Phonetic Association. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9780511807954Search in Google Scholar

Logi, Lorenzo. 2025. War(n/m)ing the room: The role of vocal sound semiotics in nuancing comedian-audience relations. Journal of World Languages. (Epub ahead of print). https://doi.org/10.1515/jwl-2025-0038.Search in Google Scholar

Logi, Lorenzo, Michele Zappavigna & J. R. Martin. 2022. Bodies talk: Modelling paralanguage in systemic functional linguistics. In David Caldwell, John S. Knox & J. R. Martin (eds.), Appliable linguistics and social semiotics: Developing theory from practice, 487–506. London: Bloomsbury.10.5040/9781350109322.ch-27Search in Google Scholar

Martin, J. R. 1992. English text: System and structure. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/z.59Search in Google Scholar

Martin, J. R. & Peter R. R. White. 2005. The language of evaluation: Appraisal in English. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.Search in Google Scholar

Martin, J. R. & Michele Zappavigna. 2019. Embodied meaning: A systemic functional perspective on paralanguage. Functional Linguistics 6(1). 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40554-018-0065-9.Search in Google Scholar

Matthiessen, Christian M. I. M. 2009. Multisemiosis and context-based register typology. In Eija Ventola & Arsenio Jesús Moya Guijarro (eds.), The world told and the world shown: Multisemiotic issues, 11–38. London: Palgrave Macmillan.Search in Google Scholar

Ngo, Thu. 2025. Language of film as literature: Developing metalanguage for talking about film sounds for language arts classes. Journal of World Languages. (Epub ahead of print). https://doi.org/10.1515/jwl-2025-0042.Search in Google Scholar

Ngo, Thu, Susan Hood, J. R. Martin, Clare Painter, Bradley A. Smith & Michele Zappavigna. 2022. Modelling paralanguage using systemic functional semiotics: Theory and application. London: Bloomsbury.10.5040/9781350074934Search in Google Scholar

Ogden, Richard. 2013. Clicks and percussives in English conversation. Journal of the International Phonetic Association 43(3). 299–320. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0025100313000224.Search in Google Scholar

Pike, Kenneth L. 1943. Phonetics: A critical analysis of phonetic theory and a technic for the practical description of sounds. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press.10.3998/mpub.9025Search in Google Scholar

Pillion, Betsy. 2019. Acoustic properties of para-phonemic sounds: Clicks in American English. In Sasha Calhoun, Paola Escudero, Marija Tabain & Paul Warren (eds.), Proceedings of the 19th international congress of phonetic sciences, Melbourne, Australia 2019, 2660–2664. Canberra, Australia: Australasian Speech Science and Technology Association Inc.Search in Google Scholar

Rose, David. 2020. The baboon and the bee: Exploring register patterns across languages. In J. R. Martin, Y. J. Doran & Giacomo Figueredo (eds.), Systemic functional language description: Making meaning matter, 273–306. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781351184533-9Search in Google Scholar

van Leeuwen, Theo. 1999. Speech, music, sound. Basingstoke: Macmillan.10.1007/978-1-349-27700-1Search in Google Scholar

van Leeuwen, Theo. 2025. Sound bites: Avenues for research in the study of speech, music, and other sounds. Journal of World Languages. (Epub ahead of print). https://doi.org/10.1515/jwl-2025-0037.Search in Google Scholar

Wright, Melissa. 2005. Studies of the phonetics-interaction interface: Clicks and interactional structures in English conversation. York: University of York PhD thesis.Search in Google Scholar

Wright, Melissa. 2007. Clicks as markers of new sequences in English conversation. In Jürgen Trouvain & William J. Barry (eds.), Proceedings of the 16th international congress of phonetic sciences, 1069–1072. Saarbrücken, Germany: Universität des Saarlandes.Search in Google Scholar

Wright, Melissa. 2011a. On clicks in English talk-in-interaction. Journal of the International Phonetic Association 41(2). 207–229. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0025100311000144.Search in Google Scholar

Wright, Melissa. 2011b. The phonetic-interaction interface in the initiation of closings in everyday English telephone calls. Journal of Pragmatics 43. 1080–1099. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2010.09.004.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter and FLTRP on behalf of BFSU

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.