Abstract

In this essay to honor Deborah Hensler, we summarize an update to her classic study on claiming behavior and explore its policy implications. More specifically, we empirically document how those with significant medical conditions utilize the civil liability system, particularly in terms of making claims against others, seeking the advice of legal professionals, and initiating litigation. We find that few who are injured or fall ill believe that another party is responsible, and even among that group, relatively few seek compensation against that party. Still fewer contact attorneys or file a lawsuit. Our findings have implications for the social welfare system, the role of tort law, and the way the selection of cases shapes the common-law. In particular, the significant non-random winnowing of the universe of harms litigated we observe can result in normatively undesirable path-dependence in the evolution of the common law.

1 Introduction

How do individuals recover losses associated with injuries and illnesses, if at all? This vital question lies at the root of important societal debates about the appropriate role of health insurance, tort law, the scope of workers’ compensation, as well as a wide range of important policy questions about the complex array of programs and policies that affect whether and to what degree an individual can recover injury- and illness-related losses. Remarkably, there is little recent empirical research in the United States that measures the extent and sources of compensation, benefits, and assistance that individuals may receive after they suffer personal harms.

To address this gap, we followed the method pioneered by Deborah Hensler[1] and conducted a survey-based measure of how losses associated with injuries and illnesses in the United States are addressed.[2] We intend to build a useful picture of the personal consequences of such losses, understand the steps that Americans typically take to offset their costs, and describe the roles of insurers, the litigation process, and other systems in ameliorating (or not) the financial and social effects of injuries and illnesses.

A RAND report detailing our findings and methods will be published in the near future. Here, we summarize the findings from our empirical study and explore some of the implications of these findings for tort theory.

Our chief finding is that a remarkably small fraction of what might be thought of as significant injuries or illnesses result in any litigation activity. This finding has implications for designing systems to ameliorate significant harms and understanding the role of tort law and the selection of cases for litigation.

2 Summary of Empirical Approach and Findings

Nearly one in five Americans experience what we defined as significant health issues annually, potentially leading to substantial pain, suffering, and economic loss. Understanding how individuals respond to significant injuries and illnesses, and how effective existing compensation mechanisms are, is crucial for designing better policies.

2.1 Approach

In February 2018, we conducted an initial screener survey administered to a nationally representative sample of 17,161 adult Americans to identify individuals who suffered significant injuries or illnesses in 2017 that met certain criteria. The respondents were members of a probability-based Internet panel developed and managed by what is now known as Ipsos Public Affairs that is widely used to conduct nationally-representative surveys. The significant conditions of interest to our study were defined by criteria such as taking four or more days off work or school, being unable to perform regular activities at home for four or more days, visiting a healthcare provider three or more times, spending at least one night in a hospital or other medical facility, or making at least one visit to the emergency department. A total of 2,967 panelists reported that they had at least one significant medical condition with onset or discovery in calendar year 2017, and provided some descriptive information about a total of 3,343 separate individual-specific conditions.

The first follow-up survey in May 2018 collected detailed information about each reported significant medical condition. The information collected included the manner of injury or illness onset; the extent and severity of the condition; the types of treatment received; the health-care related expenses incurred, paid, or still owed; work and school time lost; sources of money used to address the financial impacts of the condition; the panelist’s perception of responsibility, reasons for pursuing or not pursuing liability-based claims; the types and amounts of liability-based compensation received; satisfaction with processes and outcomes; and attitudes about the civil justice system. Because efforts to seek liability-based compensation can take months or years to develop, a second follow-up survey was distributed in August 2020. This one focused solely on questions related to responsibility, claiming, disputes, lawyer contact, and litigation in order to update what we already knew about these medical conditions from the 2018 survey.

Our analysis of the survey data covered the incidence rates of such conditions, the progression through the dispute pyramid from injury or illness onset to litigation, and the factors influencing each step – including blaming others, seeking compensation, and hiring attorneys. We also explored rates of use of the workers’ compensation system, health insurance, and paid leave, as well as factors affecting use of these support systems.

2.2 To What Extent Do Significant Injuries and Illnesses Result in Litigation and How Do Lawyers Affect That Process?

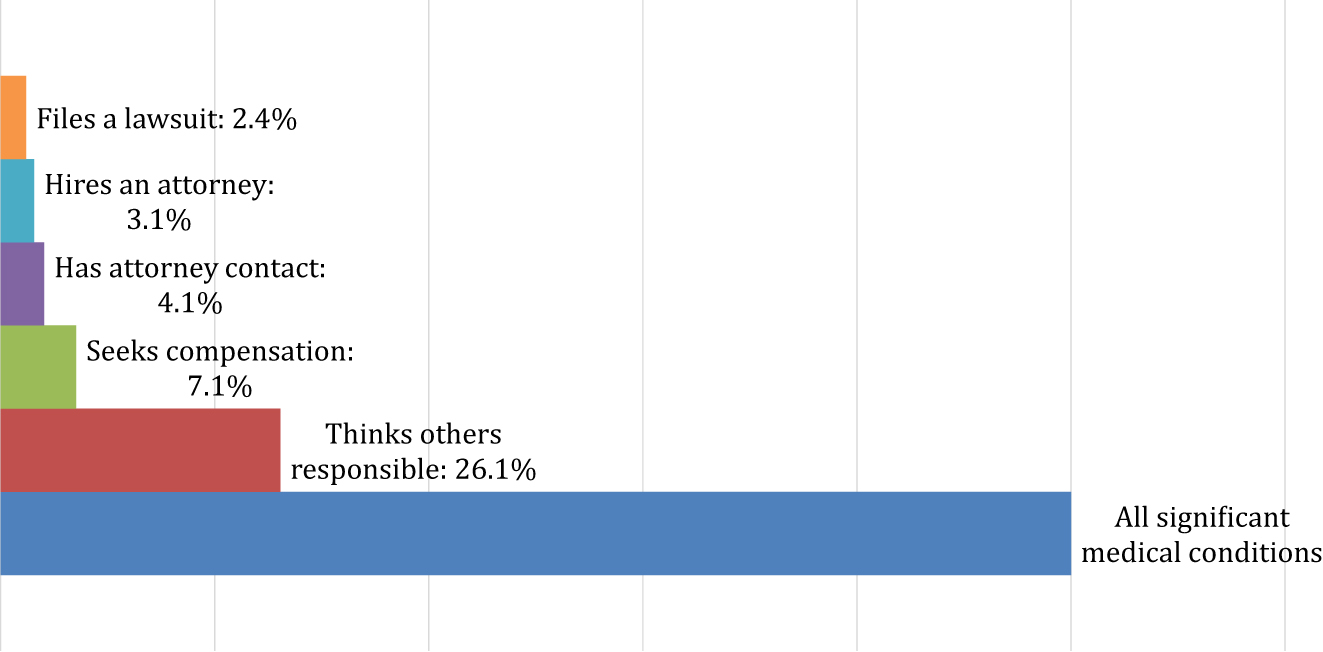

One of our primary goals was to determine to what extent significant injuries and illnesses give rise to litigation. To do so, we use the concept of the dispute pyramid, a way researchers have conceptualized the stages by which tortious harms can lead to litigation. In our version of the pyramid (see Figure 1), someone incurring a significant injury or illness may initially believe that another party was fully or partially responsible for the medical condition. Continuing to move up through the levels of the pyramid, the agrreved individual could then decide to actively seek tort compensation, contact a lawyer for advice, hire counsel, and ultimately file a lawsuit. We report the relative volume of each layer of the dispute pyramid below:

Dispute pyramid for significant injuries and illnesses. Values reflect follow-up survey weights. Unweighted Ns excluding non-responses: responsibility = 2,636; compensation seeking = 589; attorney contact = 126; attorney hire = 74; lawsuit filing = 121. Some respondents reporting the filing of a lawsuit may have done so without hiring counsel.

We find a significant drop-off in every step of the dispute pyramid process – from believing that another party was responsible, to seeking compensation from the responsible party, to filing a lawsuit.[3] For the entire universe of significant illnesses and injuries that our respondents faced, 26 percent resulted in the belief that another party was responsible, 7 percent had such belief and sought compensation from that entity, and only 2.4 percent filed a lawsuit.

We also wanted to understand the role of lawyers. We found that 4.1 % of respondents had contact with an attorney with 3.1 % hiring one.

We found that the first two steps in the pyramid are where the most falloff occurs. Respondents believed that someone else might have been responsible in about a quarter of injuries and illnesses (26.1 %). Even with a belief that someone else might have been responsible, most respondents did not seek compensation from the party (or parties. Less than three out of 10 of those injuries and illnesses in which another was viewed as responsible 27.0 %) resulted in the respondent seeking compensation from responsible parties.

There is somewhat less drop-off once compensation is sought. Of the respondents who sought compensation from a responsible party, 57.7 % attempted to get help from an attorney. About three-quarters (77.2 %) of people who contacted an attorney hired counsel and about three-quarters 76.0 %) of people who hired an attorney filed a lawsuit.

2.3 What Leads People to Blame Others, Seek Compensation, and Use the Civil Justice System to Seek Compensation?

A necessary precondition to filing most lawsuits (and the first step up from the harm-causing incident itself in the dispute pyramid) is blaming, i.e., believing that another party was at least partially responsible for causing the injury or illness or making it worse.[4] When the injuries and illnesses were medical treatment-related, work-related, product-related, or motor vehicle-related, individuals were more likely to believe that another party was responsible.

The consequences of the injury and illness also were correlated with the blaming rate. Conditions that resulted in payment of medical expenses, use of health insurance, work-related losses, changes in general health, impacts on household work, and impacts on quality of life had much higher blaming rates than conditions that did not. We also observed preliminary evidence supporting our hypothesis that lack of health insurance may make it more likely that a person with a significant health condition takes that first step on the pyramid – blaming others. While the overall blaming rate was 26.1 %, the blaming rate for those who used health insurance to pay medical expenses (23.7 %) was lower than the average. The rate for those who did not use health insurance to pay for medical expenses (27.3 %) was higher than average.

The next step to litigation is seeking compensation from responsible parties (the second step in the dispute pyramid). Here, the context of the injury or illness was important. As we observed with blaming, medical treatment-related, work-related, product-related, and motor vehicle-related injuries and illnesses had much higher rates of compensation seeking compared to the overall average. While severity of injury or illness was not associated with blaming, severity was associated with seeking compensation: between 26 % and 40 % of individuals who described their injuries or illnesses as not serious at all, not too serious, somewhat serious, and very serious sought compensation, whereas 93.4 % of respondents who suffered an extremely serious injury or illness sought compensation.

We asked those individuals who blamed others but did not seek compensation why they didn’t seek compensation. The most common reasons cited reflect respondents’ belief that seeking compensation did not seem to be the right thing to do or was not necessary (e.g., “received all of the monetary help I needed from other sources”, “just an accident and no one was really at fault,” “didn’t want to start trouble”). Other common reasons reflect a sort of informal cost-benefit analysis: Respondents thought that seeking compensation might not be worth it if the relative costs of the process are high or relative benefits are low or because other sources of compensation are available (e.g., “didn’t think anyone could prove how I became ill or injured,” “wasn’t worth the effort I’d have to put in,” “the whole process would be too expensive”).

We also examined the rate at which individuals contacted an attorney for those who decided to seek compensation (another step on the compensation pyramid). We found that 43.3 % of respondents who sought compensation from a responsible party contacted an attorney for assistance with this effort. We found no correlation between income and contacting or hiring an attorney for assistance seeking compensation. We asked individuals who contacted an attorney how they found their attorneys. The most common ways people found an attorney were through recommendations from family, a friend or coworker, and through TV, internet, the radio, or newspaper. As compared to ICJ-Hensler respondents, our survey respondents were more likely to find attorneys through legal advertising and much less likely to find attorneys through personal recommendations.

Interestingly, the injured survey respondents we polled were much more likely to be turned away by the attorneys they contacted when compared to the ICJ-Hensler respondents of 1988–89 (53 % turned away vs. 22 % turned away). When we asked the turned-away respondents why they were turned away, we observed an informal cost-benefit analysis, this time on the part of the attorneys. Attorneys were unlikely to take a case if they believed litigation costs outweighed benefits to the injured or ill party and/or the potential attorney (e.g., “too difficult or expensive to prove the seriousness of the injury or illness,” “too difficult or expensive to prove that the injuries or illnesses were related to what happened,” “too difficult or expensive to prove that some other person or some other company was legally responsible for what happened,” “couldn’t get enough money to make it worthwhile,” “too expensive to take this kind of case to court”).

Just under three-quarters (73.5 %) of people who contacted an attorney hired an attorney[5] and just over three-quarters (77.6 %) of people who hired an attorney filed a lawsuit.

2.4 Do Individuals Suffering from Illnesses and Injuries Use the Workers’ Compensation System to Cover Losses?

We found that workers’ compensation was not often utilized for injuries and illnesses that occurred on the job: only 29 % of those who were injured or became ill on the job filed worker’s compensation claims. When we asked people who were injured or became ill on the job why they didn’t file a workers’ compensation claim, the most common reason people gave was that “it wasn’t anyone’s fault”. This is surprising, because workers’ compensation is explicitly a no-fault system that does not require the worker to show fault as a precondition for compensation.

Frankly, we are somewhat puzzled by our findings. One possibility is that workers’ wrongly believe that they must show fault in order to seek compensation. This suggests that education might increase use of workers’ compensation.

A second possible explanation for the reluctance of workers to file a workers’ compensation claim is that there are societal norms against filing claims in the absence of fault. Finally, a third possibility is that our survey is picking up illnesses like the common cold and flu that employees believe they contracted at work. These illnesses, even if contracted at work would not traditionally be thought of as compensable by the workers’ compensation system.

2.5 To What Extent Do Individuals Who Suffer from Illnesses and Injuries Use Other Forms of Compensation (Insurance, Paid Leave)?

We observed wide usage of medical insurance to cover medical expenses. 72.9 % of respondents used some type of health insurance to pay for medical expenses. We did not observe wide variation in use of health insurance by income level. Comparing our survey results with ICJ-Hensler study results, we observed that health insurance is slightly more utilized to cover injury-related medical expenses today as compared to 30 years ago (74 % vs. 67 %, respectively).

We also observed modest use of paid sick leave and vacation days to cover work losses. 42.3 % of the injuries and illnesses captured in our survey resulted in a work loss – for example, missing days of work or stopping work completely.[6] Unsuprisingly, paid sick leave and paid vacation days were by far the most common ways people covered work losses, with 47.1 % of work loss covered by paid sick leave and 21.1 % of work losses covered by paid vacation days.

3 Policy Implications

3.1 Understanding the Claiming and Compensation Process and Reforms That Affect Them

First, we observe a significant incidence of serious illness and injury that befalls our nationally representative respondents. Our survey found that almost one in five Americans suffers such a hardship. On the one hand, this rate of injury or illness is unsurprising – sickness and injury are an oft noted part of the human condition. On the other, the fact that one in five Americans suffer from a significant illness or injury in any given year has real policy implications. Policies that are designed to improve societal welfare either in the civil justice system or elsewhere must account for this significant rate of illness and injury. If the rate of injury and illness were appreciably smaller, the size of our health insurance, workers’ compensation system and our civil justice system could be smaller, and other methods to compensate those individuals might be viable. The frequency and magnitude of injuries and illnesses highlights the important role that compensatory systems play.

Second, in the vast majority of significant injuries and illnesses (74.2 %) victims do not believe that other parties were responsible, much less claim against them. As a result, the civil justice system is largely irrelevant as a means of compensation for these losses.[7] The tiny percentage of injuries and illnesses for which tort suits are filed highlights the vital role of institutions outside the civil justice system -- the health insurance system to cover medical costs and other programs (sick leave, workers’ compensation, social security, and unemployment insurance) to cover losses when significant illness or injury occurs. Of course, seeking compensation from responsible parties occurs with the implicit threat of litigation so tort judgements surely influence the process of seeking that compensation. But since victims usually believe that no one was responsible for their harm, even the indirect effects of tort play a small role in compensating individuals for their losses. That is to say, the civil justice system makes a terrible social welfare insurance system simply because it compensates such a tiny fraction of the universe of individuals that are injured or ill.[8]

3.2 Debates About the Role of Tort Law

What do our findings contribute to debates about tort law? How should tort law affect regulation and what is the best way to conceptualize tort either descriptively or normatively? We address these questions in this section.

3.2.1 Justification for Tort Law

While a thorough discussion of the theory of torts is outside the scope of this paper, some of our findings are relevant to this debate. In general, there are three broad theories of tort: the economic, corrective justice, and civil recourse with many variations.[9] Each theory also has descriptive (how can tort law best be described?) and normative (what should tort law be?) versions. Due to the precedential nature of law, the descriptive can imply the normative. While there has been considerable argument about the best theory of tort law based on doctrine (corrective justice theorists, for example, argue that the lack of a duty to intervene to prevent a loss is inconsistent with a theory of tort law that is primarily about efficient safety), there has been little argument about tort theory based on empirical evidence about the civil justice system.[10] We begin to remedy this absence below by developing some of the theoretical implications of our empirical findings.

3.2.1.1 Economic Theories of Tort Law

The economic theory of tort law broadly views tort law as a mechanism for providing efficient incentives for safety in a world of scarce resources. Society implicitly or explicitly allows considerable risk-taking and harm-causing behaviors, but tort is a critical mechanism for internalizing the externalities of the risk created by these behaviors so that actors take account of these costs.[11] The descriptive version of this theory argues that judges have been, in their common-sensical way, making decisions that roughly optimize the sum of accident costs and the costs of accident reducing behavior. Normatively, some economic theorists advocate for a strict-liability rule[12] while others argue that the negligence rule leads to efficient levels of accident-reducing behavior.[13]

Does tort law create efficient economic incentives for injury and illness reducing precautions? Can or should tort be viewed as a form of decentralized economic regulation? Our conclusions on these points are limited by the fact that we do not have any independent measure of the extent to which the injuries and illnesses we observe are the result of tortious action under existing tort law.

While we have no independent measure of whether an injury or illness was caused by a tort, other scholars have overcome this obstacle in the medical malpractice context by having medical professionals review medical records for evidence of clear medical errors. They found that only 2–4% of medical errors result in litigation.[14] We have no reason to believe that the rate of litigated torts is significantly higher in our sample but we do not know.[15]

Nor do we know whether the injuries and illnesses we observe are the result of what should be defined as torts (if torts were defined optimally as a means of efficiently reducing harm-causing behavior by taking cost-justified precautions), whether or not they are under existing legal standards. Consistent with our observations, it is at least theoretically possible that potential tortfeasors are taking appropriate precautions and that the relatively low rate of blaming, claiming, and litigation that we observe reflects the absence of tortious behavior (whether that is defined under current standards or optimal standards). One might cite the very absence of claiming and litigation as evidence that these injuries and illnesses were not the result of tortious behavior. After all, if these were viable claims, why would they not have been brought? On the other hand, the unavailability of legal services, the lack of knowledge of tortfeasors’ action and the considerable work and potential social opprobrium that a plaintiff might face might be more plausible alternative explanations. Therefore, it seems to require many heroic assumptions to believe that we live an optimal Panglossian world of efficient accident prevention.

While we have no independent measure as to whether a particular injury or illness was caused by a tort, we did find that injuries and illnesses that are more likely to result from torts lead to higher rates of blaming and compensation seeking. The survey asked respondents about the context of significant injuries or illnesses, focusing on four common types of tort liability claims: motor vehicle incidents, product-related harms, employment conditions, and medical or dental treatment issues. In these contexts, people were much more likely to believe someone else was responsible for their significant illness or injury: medical treatment (51.6 %), work conditions (53.1 %), products liability (58.6 %), and motor vehicle accidents (64.5 %) compared to the overall average (26.1 %). Additionally, people were more likely to seek compensation for these types of injuries and illnesses (46–80 %) compared to the overall average (33.2 %).

Whether or not the injuries and illnesses we observe were caused by torts under existing law is a separate question from whether tort law could be used to create economically efficient means to reduce the significant burden of injury and illness that we observe. On this point, we are necessarily agnostic. On the one hand, the sheer scale of the injuries and illnesses we observe may suggest that some systematic efforts at harm reduction could be incentivized by tort liability. But given the enormous diversity of causes of harm and illness, it is hard to draw strong conclusions.[16]

As a normative goal, some theorists have argued for strict tort liability – that actors should be liable through tort to pay for the cost of the harms they cause regardless of fault. Our findings illustrate the significant change that would be required to adopt such a principle. Of the conditions for which respondents believed that another party was at least partially responsible, only 32.1 % resulted in the respondent seeking compensation from the responsible party.

Similarly, prior to the economic theorists of tort law, Fleming James argued for an insurance justification for tort law liability on the grounds that it could spread the risk that might be catastrophic if borne by a single person.[17] But, as noted above, given the small percentage of incidents that even result in a claim against another party, much less compensation, the tort system does not make a very good social insurance system.[18]

3.2.1.2 Corrective Justice

Partly in reaction to economic theorists of tort, some have suggested that tort should be viewed as a means of effectuating corrective justice and that tort law should be interpreted by judges (and legislators) accordingly. They argue that economic accounts of tort law are unable to explain key structural elements of tort like its focus on the relationship between the harmed plaintiff and the harm-causing defendant.[19] They also point out various doctrines that are difficult to explain on the economic theory of tort law, like the absence of a good Samaritan duty – a duty to intervene to help someone when it can be done at low cost or risk to oneself. Instead, they argue, tort law is a means of accomplishing Aristotle’s category of corrective justice (i.e. restoring balance by ensuring that injury inflicted by one person is compensated by the party that caused it) and focusing on the unity of the doing and the suffering.[20]

We observe a moral blame component in how our respondents view compensation which is broadly supportive of a corrective justice account of tort law. One of the leading reasons that our respondents provide for not seeking compensation is that no one was responsible. Similarly, even in the workers’ compensation context which, by design, does not require fault, respondents cite the absence of fault as a reason not to seek compensation to which they appear to be entitled.[21] This curiosity either suggests confusion about the system or a deeper moral intuition about the foundational role of responsibility and fault in the legal system (including workers’ compensation).[22]

As was true for our discussion of the normative version of the economic theory of tort law, we did not collect data on whether the defendant’s actions violated an ideal conception of the duties required by corrective justice, so our conclusions are necessarily hedged. Still, we observed a relatively large percentage of incidents in which our respondents felt another was responsible yet did not seek compensation. This suggests the corrective justice function of tort is limited in its efficacy. This conclusion has normative implications for the attractiveness of corrective justice as a normative guide to tort.

3.2.1.3 Civil Recourse

Civil recourse theory builds on the observations of corrective justice and accepts its critique of the economic theories of tort. It also shares corrective justice theorists focus on tort as being fundamentally about a relational wrong between harmed plaintiff and harm-causing defendant.[23] A key difference between corrective justice theorists and civil recourse theorists is the role of remedy. For corrective justice theorists, the remedy (e.g. tort compensation) is the means by which the wrong is righted. For civil recourse theorists, the remedy is an incentive for plaintiffs to undertake the sometimes difficult task of confronting the wrongdoer and the point of tort is broader than merely righting a specific wrong. Goldberg and Zipursky argue that since the state has a monopoly on violence and has prohibited vigilantism and other forms of self-help, it has an obligation to provide a legal mechanism – a civil recourse. They note that in many instances, remedies are wholly inadequate to actually remedy harms or accomplish corrective justice.[24]

On the one hand, our findings support civil recourse theory’s more modest goals for tort law – not to actually accomplish corrective justice (or economic efficiency) but merely provide a procedural mechanism that can theoretically be pursued. The low rates of blaming, claiming and litigation that we observe are broadly consistent with the bare existence of a procedural mechanism to seek redress. Yet at some point, one wonders if a partly chimerical right of civil recourse leads to a satisfying theory of tort. The version of civil recourse theory that our findings support seems unsatisfying in providing any kind of normative guidance.[25] And the equitable implications of a theory of tort that guarantees only theoretical procedural access to redress are troubling if only the privileged have the means to pursue.

3.2.2 Tort and Regulation

Does tort law act as an important adjunct to the regulatory administrative state? What do our findings say, if anything, about the relationship between tort and regulation? Here our findings are limited but important. Tort plays a direct role in a very small fraction of injuries and illnesses, even when the victim believes that another party is responsible. This suggests it has a limited direct role in creating deterrence. Nevertheless, the threat or shadow of tort liability may significantly shape behavior even in the absence of much actual litigation or even claiming at least in some contexts (e.g. dram shop liability, product design).

Still, the paucity of claiming, coupled with the well-documented obstacles to bringing a claim[26] suggest that the tort system should not be viewed as a wholesale substitute for the regulation of risky activity. Perhaps it is best viewed as a limited but usefully independent system to create incentives for safety.[27] Tort cannot replace legislation or regulation of risks but can buttress both processes. And because it is a common-law process and does not rely upon legislation, rulemaking, or enforcement it may be better able to identify and create incentives to govern novel risks or emerging technologies.

3.3 Effect of Health Insurance Changes on Compensation and the Claiming Process

We anticipated that the passage of the Affordable Care Act and the wider debate about the importance of health insurance would have significantly increased health insurance as a mechanism for compensating victims as compared to the ICJ-Hensler study 30 years ago in 1991. Surprisingly, the difference in the use of health insurance is relatively small. In 1991, the ICJ-Hensler study found that 67 % of respondents used health insurance for medical expenses related to injuries.[28] In comparison, when we looked at medical conditions in our data that were defined as injuries we found 72.9 %, an increase of 5.9 %. So, while there was an increase, it was more modest than we expected. The finding also highlights the fact that 27.1 % of our respondents with a significant injuries did not use health insurance for their medical expenses. Recent estimates of the rate of uninsured in the United States are approximately 8 %.[29] We are uncertain as to the reasons for this relatively low rate of utilization of insurance and further research on this topic would be useful.

3.4 Implications on the Selection of Cases for Litigation and the Common-Law

The selection of cases for litigation has implications for the development of the common law. If only certain types of cases (or cases with particular litigants) are litigated to finality, the court of final appeal will only receive briefing on those cases and may have limited information about the effect of their rulings on the larger universe of cases that are not appealed to their court. Given the financial and time cost of extensive litigation, some have suggested that deep-pocketed repeat player litigants influence the common-law to their advantage in this way.

But this outsized influence over the common law could also be true for specific categories of cases. If motor vehicle injury cases or injuries occurring in the home, for example, were often litigated to finality, tort law might be shaped by the particular problems raised therein.

And while many have noted the greater influence of cases litigated to final resolution, it is true at every level of the dispute pyramid. If only certain types of injuries and illness are likely to result in a victim that identifies another party as responsible, only those types of risks will be subject to litigation and shape the common law. If only certain types of injuries and illnesses result in claims against other parties, only those types of risks will be able to shape the common law. Throughout the litigation process, there is a truncation of the universe of risks that shape the common law. This winnowing process results in a tiny fraction of potential risks being presented to the court of finality.[30] While there is considerable theorizing about the way this common law process functions, there is little empirical examination of this dynamic.

To the extent the common law shapes public and professional (lawyer) values about when a case is worth pursuing, there may be a self-reinforcing dynamic between the cases that shape the common law and the public/professional opinion. That is, if the public only believes that certain types of cases are worth pursuing (e.g. serious cases that involve some moral blameworthiness), those are the only cases that will be seen by the courts and the only cases that are reported in the media or that have appellate opinions written. Similarly, if lawyers only believe that certain categories of cases are worth bringing, they will also shape the cases the courts see.[31] In this way, norms about what makes a worthy case can be perpetuated and create a feedback loop.

And there is no particular reason to believe that this dynamic – perpetuation of certain kinds of litigation and truncation of other cases courts see – will yield normatively desirable legal rules.[32] For all the genius of the common law, even the most conscientious judge can’t know what she never sees.[33] There may be evolution as litigants and creative lawyers push new variations, but there may also be considerable undesirable path-dependence in the evolution of the common-law.[34]

While some legal theorists have noted the potential impact on the selection of cases for litigation on the common law, none have attempted to couple their observations with actual data about the process. So, what insight do our findings yield on this shaping process and how it might affect the development of the common law? Below, we proceed step-by-step through the dispute pyramid truncation process and discuss its implications.

As noted above, a precondition for litigation is usually believing that another party is responsible. This occurs in 24.4 % of cases in our sample. Injuries and illness that were medical treatment-related, work-related, product-related, and motor vehicle-related were more likely to result in the victim believing that another party was responsible.[35] Similarly, the consequences of the injury or illness were also important. Conditions that resulted in payment of medical expenses, use of health insurance, work-related losses, changes in general health, impacts on household work, and impacts on quality of life had much higher blaming rates (though self-described severity did not make a difference). Hence injuries and illnesses of those types and from those contexts are more likely to shape the development of the common law.

At this level of the dispute pyramid the selection effects seem mostly intuitive – cases with more obvious responsible parties and effects are more likely to lead to claiming and thus the possibility of litigation and effect on the common law. As noted above, the obviousness of the responsible parties is a self-reinforcing phenomenon. Victims of motor-vehicle crashes are more likely to bring lawsuits because of the well-developed infrastructure for bringing those lawsuits which, in turn, results in a well-developed body of law and social expectations around those harms. In contrast, many harms that occur within the household lack similar infrastructures and narratives of compensation.

This pattern of self-reinforcement is inconsistent with theories of the common law that suggest that new claims are most likely to be brought in the uncertain areas of the law such that the common law gradually clarifies more and more uncertain legal doctrine. In the real world we observe claims progress because there are existing avenues for those claims that both victims and lawyers are familiar with. Legal doctrine is at least partially shaped by the crucible of the selection of these cases for litigation.

The next step of truncation on the path to litigation in the dispute pyramid is not just believing another party is responsible but seeking compensation from that party. This occurs in only 6.3 % of the incidents we observe in our sample, and 32.1 % of incidents in which another party was believed responsible.

Here we found that the context and severity of the injury or illness was important. While between 26 % and 40 % of individuals who described their harms as not serious at all, not too serious, somewhat serious, and very serious sought compensation, 93.4 % of respondents who suffered an extremely serious injury or illness sought compensation. As with the finding-another-party-responsible-stage, medical treatment-related, work-related, product-related, and motor vehicle-related injuries and illnesses had much higher rates of seeking compensation compared to the overall average.

We also looked at reasons that respondents did not pursue compensation when they believed that another party was responsible to identify additional sources of truncation for the universe of cases that shape the common law. Most of the responses centered around a sense that seeking compensation was something to be generally avoided and that it may not be worth the effort or that they had already received assistance from other sources.

Next, we looked at the rate of contacting an attorney for those who sought compensation. About half contacted an attorney, but interestingly 46 % were turned away by attorneys, typically due to cost of litigation.

We did not collect data on the subsequent winnowing of cases that shape the common law during the litigation process – the decision to appeal the outcome of the trial and the decision of appellate courts to publish a precedential opinion.

Overall, we observe enormous non-random winnowing from the overall universe of potential disputes to the tiny fraction that shape the common-law of torts. What effects does this process have?

First, the threshold perception that another party may be responsible is partly the result of existing societal norms and institutions of claiming and blaming rather than any extra-legal truth of responsibility. In many potential cases, the would-be plaintiff felt that either no one was to blame or that it would not be worth the effort. This is a function of norms and institutions. We are accustomed to blaming others for automobile injuries and other drivers in particular – not typically car manufacturers or road construction authorities. This is partly a result of the path-dependent evolution of our system of compensation for automobile injuries. It is possible that tort law helps shape our collective responsibilities. As we have observed, responsibility or fault is often a prerequisite to pursuing a tort claim. But the causal arrow may point in both directions – tort may help create that sense of fault.

A similar self-reinforcing pattern is true among lawyers’ decision to take a case and file a lawsuit. Certain kinds of cases are worth taking because they are “good” cases. One of the necessary conditions for a case to be worth taking is some precedent for that kind of claim.

Second, we observed and collected data only about the truncation of cases among potential plaintiffs. There are different dynamics of truncation on the defense side. On the one hand, defendants obviously cannot choose which plaintiffs sue them. But because some defendants are repeat-players, insurers, most obviously, they may have more opportunities to choose which cases to settle and which cases to litigate. These effects are outside the scope of our research but likely have important interactions with the effects we observed.

4 Conclusions

In this Essay, we documented the considerable toll of significant injury and illness and the various means that individuals receive compensation, with a particular focus on the claiming and litigation process. Overall, we note significant attrition at every step of the dispute resolution process, from the initial perception that another may be responsible to the decision to claim, to retaining a lawyer to filing a lawsuit. We hope that this evidence will influence a range of policy debates that are too often based on anecdote rather than evidence. That said, much important empirical research on claiming and compensation remains to be conducted so that the role of the civil justice system in providing corrective justice, efficient incentives, and compensation to the injured and ill can be improved.

We also explored the impact of our findings on questions about the role of tort law and the evolution of the common law and began to explore the theoretical implications of our empirical findings. We found that our empirical findings were difficult to reconcile with strong versions of either the descriptive or normative economic or corrective justice theories of tort law though the absence of data as to whether the injuries or illnesses were caused by a tort limits our conclusions. We also discussed the way that the radical truncation of disputes throughout the process shapes the cases that create the common law.

Deborah Hensler has been a pioneer in the employment of modern social scientific methods to study questions with important doctrinal and policy implications. When she published her first report on claiming in 1991, empirical methods in legal academic scholarship were rare indeed. Today, it is more common to find legal scholars employing empirical methods but so doing is still more the exception than the rule. We hope this Essay demonstrates the fruitfulness of employing simple empirical methods to shed light on even theoretical legal questions. Doing so would truly honor Professor Hensler’s remarkable legacy.

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Science Foundation and the RAND Institute for Civil Justice for funding this research. We want to thank Alex Wu, Ellen Bublick, Greg Keating and the Board of Advisors for the RAND Institute for Civil Justice for their excellent and thought-provoking suggestions. Finally, we want to thank Deborah Hensler for inspiring this research and being a wonderful guide and mentor.

-

Research funding: This work was supported by the National Science Foundation and the RAND Institute for Civil Justice for funding this research.

© 2025 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Introduction

- Complex and International Litigation and Empirical Litigation Studies: Festschrift in Honor of Professor Deborah Hensler, Editors’ Introduction

- Articles

- Empirical Tort Law (and Theory) – An Essay in Honor of Deborah Hensler

- Pulling Back the Curtain on the Federal Class Action

- The (Un)intended Consequences of Legal Transplants: A Comparative Study of Standing in Collective Litigation in Five Jurisdictions

- Essays

- Deborah Hensler and the Institute for Civil Justice Striving to Speak Truth to Power in the Tort Reform Debate

- Stories, Individuals, Statistics, Aggregation, Torts, and Social Justice: Deborah Hensler’s Aspirations for Law

- Deborah Hensler: A Teacher of Judges

- Reflections on a “Data-Driven” Life in Law

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Introduction

- Complex and International Litigation and Empirical Litigation Studies: Festschrift in Honor of Professor Deborah Hensler, Editors’ Introduction

- Articles

- Empirical Tort Law (and Theory) – An Essay in Honor of Deborah Hensler

- Pulling Back the Curtain on the Federal Class Action

- The (Un)intended Consequences of Legal Transplants: A Comparative Study of Standing in Collective Litigation in Five Jurisdictions

- Essays

- Deborah Hensler and the Institute for Civil Justice Striving to Speak Truth to Power in the Tort Reform Debate

- Stories, Individuals, Statistics, Aggregation, Torts, and Social Justice: Deborah Hensler’s Aspirations for Law

- Deborah Hensler: A Teacher of Judges

- Reflections on a “Data-Driven” Life in Law