A 41-year-old man with bipolar disorder, hypertension, and polysubstance use presented to an outpatient dermatology clinic in October 2022 for treatment of dissecting cellulitis of the scalp and hidradenitis suppurativa (HS). He reported an “HS lesion” on his right lateral thigh that was solid, painful, and would “burst” a few times per year for the previous five years. On examination, the patient had a 3.2 × 2.5 cm shiny brown tumor with overlying central scale and mild crust (Figure 1). The patient underwent a punch biopsy and received a one-time empiric treatment with intralesional corticosteroid for possible keloid. Punch biopsy revealed parakeratosis with hemorrhage within the stratum corneum, epidermal hyperplasia and dermal neoplasm composed of atypical spindle cells exhibiting marked pleomorphism, increased mitotic activity, and bizarre nuclei. Extravasated blood, as well as multinucleated foamy cells containing hemosiderin, were present. The differential diagnosis based on clinical and preliminary histologic information included atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX), pleomorphic dermal sarcoma (PDS), leiomyosarcoma, and atypical fibrous histiocytoma (AFH).

A brown tumor, 3.2 × 2.5 cm in size, on the right lateral thigh.

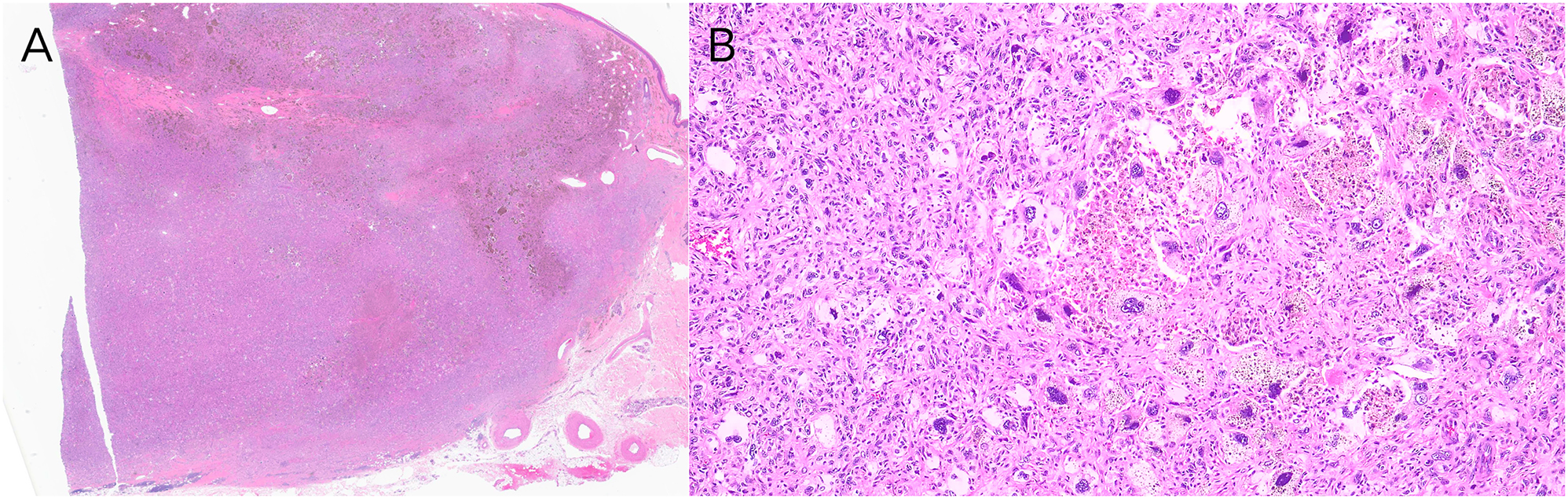

Subsequent narrow excision revealed a large, circumscribed intradermal and superficial subcutaneous proliferation of mononuclear cells, many with enlarged, pleomorphic nuclei (Figure 2A), many multinucleated fibrocytes and histiocytes, some distributed between thickened, sclerotic collagen bundles with abundant siderophages and hemosiderin deposition. Centrally, there were dilated vessels with red blood cells and focal necrosis. Scattered atypical mitoses were present (Figure 2B). Around the periphery, there was focal fat trapping and entrapment of ropey collagen bundles. The plump-spindled cells, many with prominent nucleoli, were arranged primarily in a storiform to short fascicular pattern. Tumor cells were CD68+, CD163+, CKCKT-, SOX-10-, Desmin-, and CD34-. Taken together, the features of this large, circumscribed intradermal and subcutaneous histiocytic proliferation with pleomorphic cells were felt to be most similar to those seen in AFH (dermatofibroma with “monster cells”). However, given the large size of the neoplasm, significant degree of nuclear pleomorphism, and mitotic activity, PDS remained difficult to exclude. Close clinical monitoring was recommended. Unfortunately, the patient was lost to follow-up and died two years after initial presentation from cardiac arrest unrelated to the tumor.

Histopathology of the brown tumor. (A) Hematoxylin & eosin, original magnification ×1.25. Narrow excision of large, circumscribed, deeply extending intradermal and superficial subcutaneous proliferation of atypical spindled cells. (B) Hematoxylin & eosin, original magnification ×10. Excision with atypical spindled cells exhibiting marked pleomorphism, increased mitotic activity, and bizarre nuclei.

Diagnostic criteria of these rare entities is an ongoing debate. Other spindled neoplasms must be excluded, including melanoma, squamous cell carcinoma, angiosarcoma, and leiomyosarcoma [1], 2]. While leiomyosarcomas typically present on extremities as red-brown nodules or plaques with a range from low-grade to high-grade lesions, these are positive for desmin whereas this case was not. Distinguishing AFH, AFX, and PDS from each other is challenging. There are no specific stains/tests distinguishing AFX from PDS [3], 4]. The histologic features of AFX/PDS overlap with AFH, including variable pleomorphic spindled cells in a collagenous stroma, high mitotic activity, necrosis, and infiltration into superficial subcutaneous fat [1], 2], 5]. Key distinctive features of AFH include no evidence of significant actinic damage or solar elastosis and identifying classic features of dermatofibroma: spindle cells arranged in a storiform pattern with thickened collagen bundles at the periphery of the lesion [5]. AFH has been proposed to be recategorized under PDS as a low-grade sarcoma given that two of 21 cases had metastasis in the largest study to date [5]. However, the authors of that study reaffirm AFH is a distinct clinical and histopathologic entity that is benign, and categorizing AFH as a low-grade sarcoma would result in significant overtreatment [5].

AFX/PDS lie on a spectrum. AFX is confined to the dermis, composed of pleomorphic epithelioid, spindled, and multinucleated giant cells arranged in sheets and fascicles without necrosis [2]. In contrast, PDS, which is synonymous with undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma of the skin (can also be referred to as cutaneous undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma, cUPS, or previously pleomorphic variant of malignant fibrous histiocytoma [MFH]), extends to the subcutis, exhibits tumor necrosis, and may have lymphovascular and perineural infiltration [2], 6]. Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (not of the skin) describes a group of soft tissue sarcomas that may involve deeper soft tissue structures [6] and have a high risk of metastasis and recurrence. Mohs micrographic surgery or wide local excision remain the treatment of choice for AFX/PDS [7].

Clinically, AFX/PDS affects sun-damaged areas of the head and neck in older adults, presenting as rapidly enlarging dome-shaped or ulcerated nodules [1], 6], whereas AFH presents on extremities of young/middle-aged adults as a solitary, firm, cystic cutaneous nodule [5]. In our case, the tumor was slow-growing (>5 years), sun-protected, in a young/middle-aged patient, and histopathologically had features of classic dermatofibroma at the periphery, consistent with AFH. It is less likely to be an atypical case of PDS. However, given that AFH remains a highly debated entity in dermatopathology, we suggest shared decision-making with the patient regarding referral to a multidisciplinary cutaneous oncology conference and consideration for imaging to assess for metastasis. Regardless, margin control and close monitoring for recurrence is paramount [5], 7].

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: The authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: None declared.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

1. Beer, TW, Drury, P, Heenan, PJ. Atypical fibroxanthoma: a histological and immunohistochemical review of 171 cases. Am J Dermatopathol 2010;32. https://doi.org/10.1097/dad.0b013e3181c80b97.Search in Google Scholar

2. Miller, K, Goodlad, JR, Brenn, T. Pleomorphic dermal sarcoma: adverse histologic features predict aggressive behavior and allow distinction from atypical fibroxanthoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2012;36:1317–26. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0b013e31825359e1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Hanlon, A, Stasko, T, Christiansen, D, Cyrus, N, Galan, A. LN2, CD10, and ezrin do not distinguish between atypical fibroxanthoma and undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma or predict clinical outcome. Dermatol Surg 2017;43:431–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/DSS.0000000000001000.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Koelsche, C, Stichel, D, Griewank, KG, Schrimpf, D, Reuss, DE, Bewerunge-Hudler, M, et al.. Genome-wide methylation profiling and copy number analysis in atypical fibroxanthomas and pleomorphic dermal sarcomas indicate a similar molecular phenotype. Clin Sarcoma Res 2019;9:2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13569-019-0113-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

5. Kaddu, S, McMenamin, ME, Fletcher, CDM. Atypical fibrous histiocytoma of the skin: clinicopathologic analysis of 59 cases with evidence of infrequent metastasis. Am J Surg Pathol 2002;26:35–46. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000478-200201000-00004.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Bowe, CM, Godhania, B, Whittaker, M, Walsh, S. Pleomorphic dermal sarcoma: a clinical and histological review of 49 cases. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2021;59:460–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjoms.2020.09.007.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Jibbe, A, Worley, B, Miller, CH, Alam, M. Surgical excision margins for fibrohistiocytic tumors, including atypical fibroxanthoma and undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma: a probability model based on a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol 2022;87:833–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2021.09.036.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.