Abstract

Context

Folate deficiency is often observed in patients with inflammatory diseases, raising questions about its role in knee osteoarthritis (OA) progression.

Objectives

This study aimed to assess the association of folate deficiency with the clinical and radiological severity of knee OA.

Methods

A prospective cross-sectional study was conducted from January 1, 2019 to January 1, 2020. Primary knee OA patients referred to orthopedic clinics in Zabol, Iran were included. Radiographic severity was gauged utilizing the Kellgren–Lawrence (KL) classification. For clinical severity, patients completed the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) questionnaire. IBM SPSS v.27 facilitated the statistical analysis.

Results

Forty-nine knee OA patients, averaging 67.45±13.44 years in age, were analyzed. Spearman correlation analysis revealed a negative correlation between folate levels and both WOMAC and KL scores. The correlation was stronger between folate and KL score (Spearman correlation coefficient: −0.75) than between folate and WOMAC total score (Spearman correlation coefficient: −0.46). Additionally, a significantly higher KL score was observed in patients with folate deficiency (p=0.004).

Conclusions

Our study highlights a significant correlation between folate deficiency and increased severity of OA, which is evident in radiological and clinical assessments. These findings suggest that folate plays a key role in OA pathogenesis and could be a modifiable factor in its management.

The most noticeable and debilitating symptom of osteoarthritis (OA) is pain. Symptomatic therapy remains the only available treatment for knee OA, making the understanding of pain causes crucial to the effective treatment of this prevalent condition [1]. The primary factors contributing to pain intensity are believed to be detrimental mechanical stress on the joint and inflammation, particularly synovitis [2].

One of the primary causes of knee OA is harmful mechanical stress across the knee joint [3]. The posture of the lower limbs is linked to knee OA discomfort. Lower limb malalignment and high body mass index (BMI) are risk factors for the development of knee arthritis due to their relationship with joint strain [4], [5], [6], [7], [8].

Moreover, it is widely recognized that inflammation is connected to the pathogenesis of knee OA. The release of degenerative compounds from the extracellular matrix of articular cartilage into the synovial fluid may primarily cause synovitis in OA, which is a secondary condition associated with changes in bone and cartilage [9]. This could expedite cartilage destruction. Because synovitis has been shown to be a potential marker for knee pain and a predictive variable for the structural and symptomatic progression of the disease, the role of synovitis in OA has recently garnered significant attention [10], [11], [12], [13], [14]. Previous studies have indicated a significant discrepancy between pain perception and radiographic OA.

Although knee OA is largely viewed as a mechanically driven disease, it is acknowledged that the presence of low levels of inflammation can lead to cartilage degeneration at certain stages of OA [11]. Numerous studies suggest that inflammatory complement activation and synovium inflammation are crucial factors in knee OA pathogenesis [12, 13].

Folate, a B vitamin (vitamin B9), serves as a cofactor for one-carbon transfer reactions. These reactions are involved in the synthesis of the amino acid methionine, DNA nucleotides, and in regulating homocysteine levels. Evidence suggests that these reactions play a role in generating and maintaining inflammatory responses. Folate deficiency is commonly observed in patients with inflammatory diseases [14].

The aim of this study was to evaluate the association of folate deficiency with the clinical and radiological severity of knee OA.

Methods

The present study is a prospective, cross-sectional study conducted from January 1, 2019, to January 1, 2020, after obtaining ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of Zabol University of Medical Sciences (IR.ZBMU.REC.1400.057).

All of the primary knee OA patients who were referred to orthopedic clinics in Zabol, Iran were included in research utilizing the simple and convenient sampling technique. Secondary cases of knee arthritis were excluded. All participants filled and signed a written informed consent form before participating in the study.

Patients’ data and diagrams were collected via questionnaires, and body diagrams were completed by the patients. The radiographic severity was assessed utilizing the Kellgren–Lawrence (KL) classification. Two independent orthopedic specialists interpreted the X-rays, and in cases where their interpretations differed, a radiologist made the final and correct interpretation. Patients were asked to fill the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) questionnaire to measure the clinical severity of their pain.

Sample collection

Blood samples were collected from patients by trained phlebotomists following an overnight fast to avoid any potential food-induced changes in serum folate levels. Approximately 5 mL of venous blood was drawn from each participant and collected in an ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) tube. Blood samples were immediately centrifuged for 10 min at 4,000 rpm, and the separated serum was stored at −80 °C for further analysis. Folate levels were determined utilizing the Quantaphase Folate Radioassay Kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Folate deficiency was defined as a level below 4 ng/mL.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed utilizing IBM SPSS v.27 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics for normally distributed variables are presented as mean±standard deviation (SD). The independent t test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) were utilized to compare quantitative variables between groups. The inter-rater reliability was assessed utilizing the intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) with a two-way mixed model of absolute agreement.

To assess the relationship between WOMAC/KL scores and folate level, we utilized multivariate linear regression models. Each model included WOMAC/KL scores as the dependent variable and folate levels as the independent variable, adjusted for potential confounding factors like BMI, sex, age, physical activity, smoking, education, alcohol consumption, vitamin D, and ferritin levels.

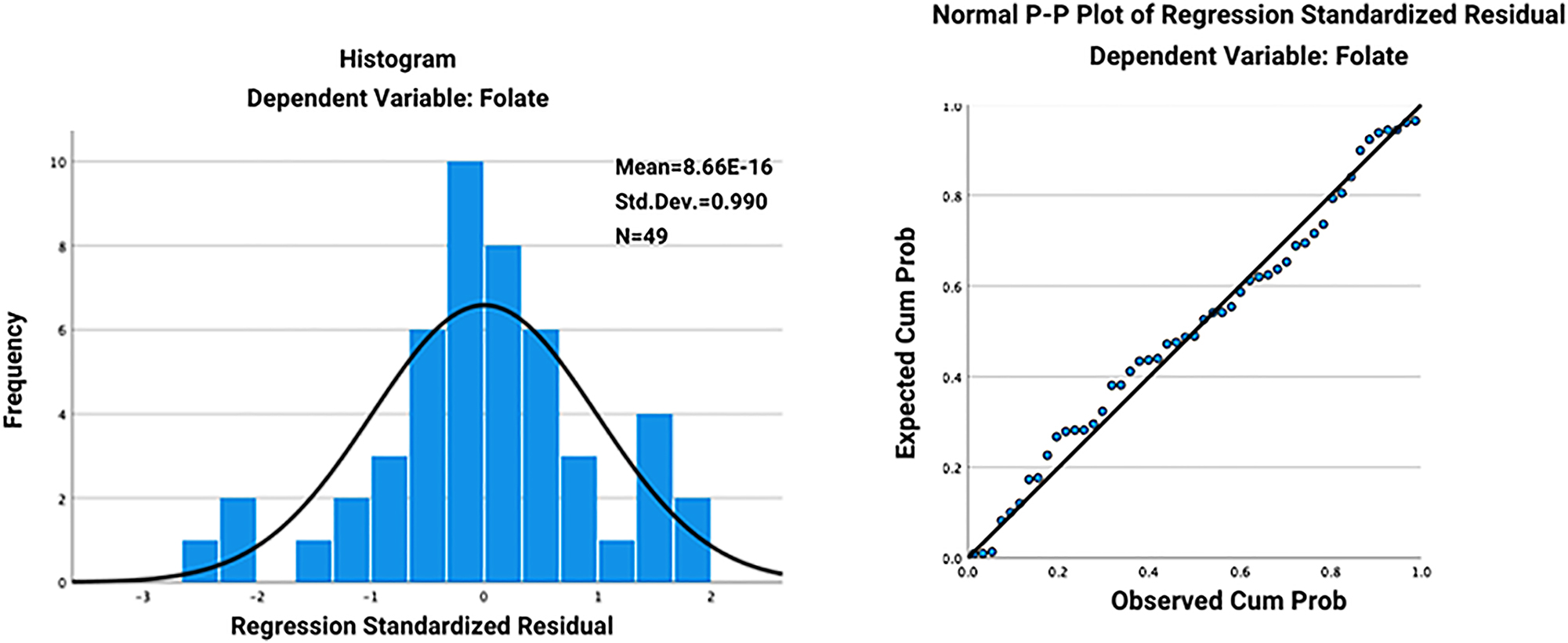

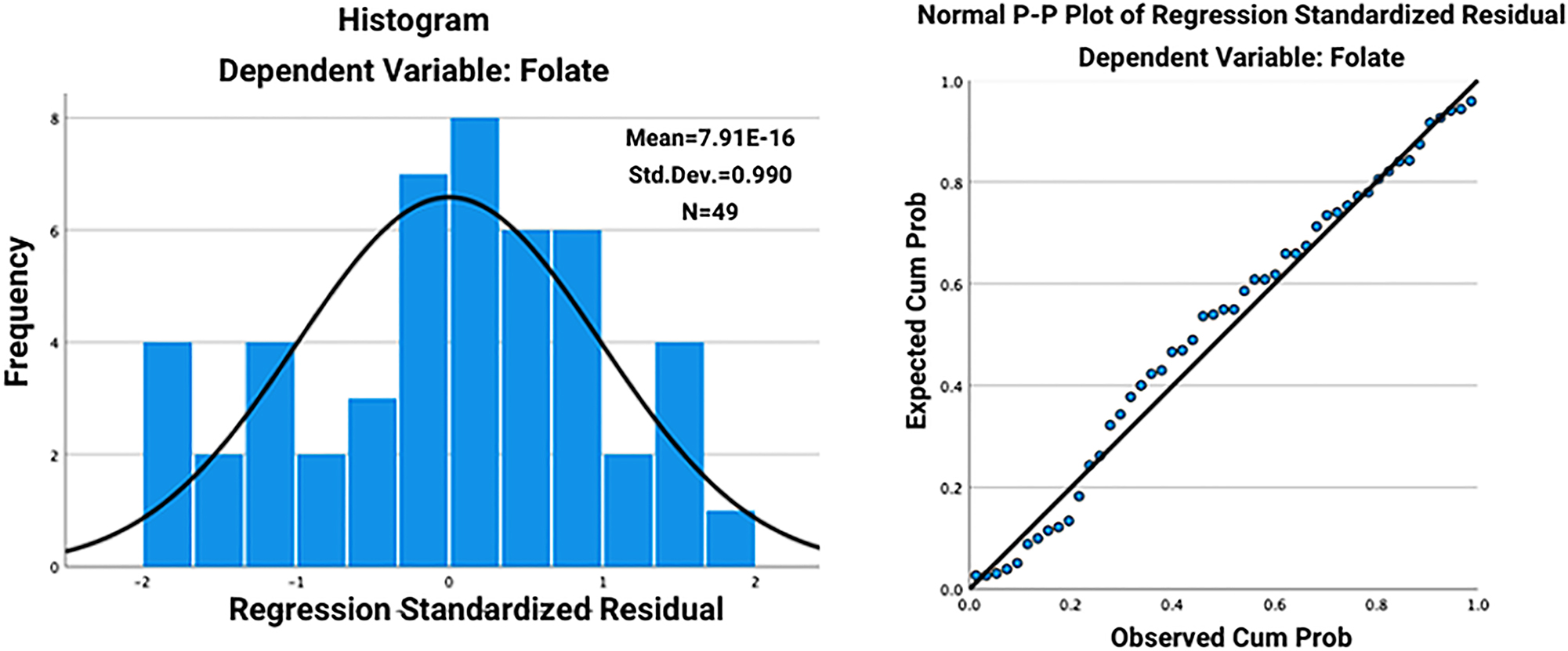

Tables 1–3 present the results of these multivariate linear regression models. The models were assessed for the assumptions of linearity, independence of errors, homoscedasticity, unusual points, and normality of residuals. We inspected the normal probability plots of the regression standardized residual for normality, as well as the histograms (Figures 1 and 2).

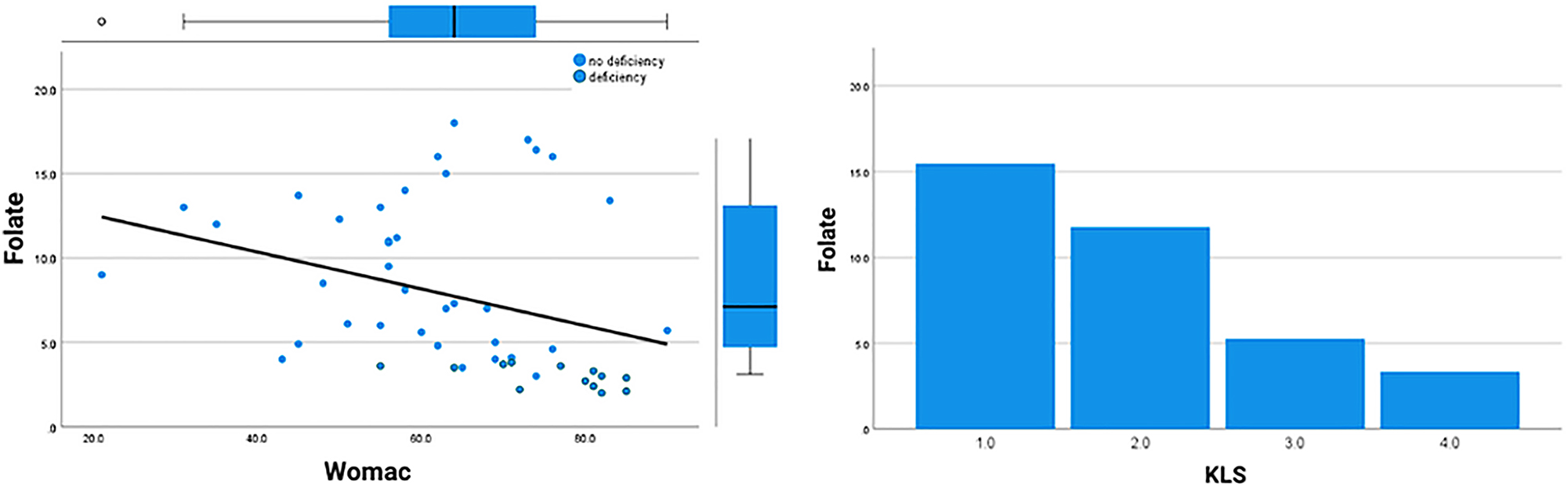

Correlations between radiological and clinical scores and folate levels.

The histogram (A) and normal probability plots (B) of the regression standardized residual for the relationship between folate level and Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) score.

The histogram (A) and normal probability plots (B) of the regression standardized residual for the relationship between folate level and Kellgren–Lawrence (KL) score.

The Spearman correlation coefficient was utilized to examine the relationship between nonnormally distributed quantitative variables. A p value <0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

This study analyzed patients with knee OA symptoms (n=49), with a mean age of 67.45±13.44 years (range, 45–83 years). The sample included 26 (53.1 %) male participants, and the rest (23 [46.9 %]) were females. The patients’ mean scores for pain, stiffness, and daily function were 15.57±2.79, 4.32±1.68, and 37.71±6.65, respectively, with a mean total score of 67.6±7.49 (Table 1).

The average daily performance score for the women surveyed was higher (35.69±6.19) than for the men (33.84±7.04), whereas the mean scores for joint pain and stiffness were higher in men (12±2.75 vs. 4.53±1.50). Furthermore, women with knee pain had a higher overall WOMAC score than men, although none of these differences were statistically significant.

Only the daily performance score of OA patients was strongly correlated with age (p<0.05). The research indicated that as patients’ age increases, their everyday performance conditions deteriorate more severely (correlation coefficient: −0.023). However, age, pain, stiffness, or the patients’ total score did not show any significant statistical association.

In addition, there was no statistically significant relationship between the patients’ BMI and any of the pain, stiffness, daily function, or total score scales.

According to the study’s findings, there was no statistically significant correlation between the total score of patients with various grades of KL and the scales of pain, joint stiffness, and daily function. A pairwise assessment of WOMAC component scores among those with various stages of the disease demonstrated that there were no significant differences in pain, stiffness, function, or total score across groups of patients with varying degrees of OA (Table 1).

Comparison of KL grades with the WOMAC scales in the studied patients.

| Variable | Grade I (mean rank) | Grade II (mean rank) | Grade III (mean rank) | Grade IV (mean rank) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain | 20.17 | 27.34 | 23.50 | 29.90 | 0.57 |

| Stiffness | 29.83 | 20.50 | 25.95 | 29.40 | 0.39 |

| Daily performance | 36.58 | 24.47 | 23.95 | 17.40 | 0.13 |

| Overall score | 34 | 24.16 | 24.05 | 21.10 | 0.40 |

-

KL, Kellgren–Lawrence; WOMAC, Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index.

Correlation between WOMAC/KL scores and folate levels

The results of the Spearman correlation analysis showed a negative correlation between the folate level and both WOMAC and KL scores. However, this correlation was much stronger between folate and KL score (Spearman correlation coefficient: −0.75) compared to folate and WOMAC total score (Spearman correlation coefficient: −0.46) (Table 2, Figure 3).

Spearman correlation between WOMAC/KL scores and folate level.

| Variable | Spearman correlation coefficient | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| WOMAC score | −0.46 | <0.001 |

| KL score | −0.75 | <0.001 |

-

KL, Kellgren–Lawrence; WOMAC, Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index.

The KL score was significantly higher among patients with folate deficiency (p=0.004). Although the mean WOMAC score among folate-deficient (FD) patients was higher, this difference was not significant (Table 3, Figure 1).

The association between WOMAC/KL scores and folate deficiency.

| Variable | Folate deficiency (13) | No folate deficiency (36) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean WOMAC score | 75.7±8.9 | 59.6±14.2 | 0.19 |

| Mean KL score | 3.62±0.4 | 2.3±0.9 | 0.004 |

-

KL, Kellgren–Lawrence; WOMAC, Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index.

Discussion

Folate, also known as vitamin B9, plays a crucial role in many biological processes, including nucleotide synthesis, amino acid metabolism, and methylation reactions. Deficiencies in folate can lead to several health complications such as megaloblastic anemia, cardiovascular disease, and potentially certain types of cancers [15, 16]. Additionally, adequate folate levels have been indicated by several studies as a prerequisite for the improvement of the processes associated with inflammation [15], [16], [17].

Inflammation is a key player in OA pathogenesis. It regulates the catabolism and anabolism of the knee joint through different factors released from synoviocytes and chondrocytes. Chemokines and cytokines are also essential for this process [18]. Importantly, folate deficiency can influence this inflammatory cascade. It has been shown to reduce T cell proliferation and cause a decrease in CD8+ T lymphocytes, which play a critical role in immune responses [19].

Considering the role of inflammation in OA and the effect of folate on immune response, it is plausible that folate deficiency could influence OA severity. Indeed, our study showed that both radiological (KL score) and clinical symptoms (WOMAC) increased significantly among patients with low levels of folate. This association was only significant for KL score, suggesting a possible link between folate levels and radiological changes seen in OA.

This aligns with the findings of Xu et al. [19], who reported a significant association between folate deficiency and radiological severity of knee OA. Their study, however, did not evaluate the association of folate with the clinical characteristics of OA, therefore highlighting the novelty of our study in providing a more comprehensive understanding of the potential role of folate in OA.

Specifically, recent studies have demonstrated that synoviocytes cultivated under FD conditions exhibit elevated reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and increased cytosolic Ca2+ release, leading to apoptotic lethality [20]. This mechanistic insight is consistent with our results, suggesting that folate deficiency contributes to OA pathogenesis not only through impaired immune response but also by directly exacerbating cellular stress and apoptosis in joint tissues.

In addition, Hong et al. [21] found that higher levels of folate were associated with a reduced risk of OA, notably in weight-bearing joints such as the knee and spine, and this protective effect was observed in both males and females. The consistency of these findings across different study designs reinforces the hypothesis that folate plays a significant role in mitigating OA pathogenesis. This convergence of evidence highlights folate’s potential as a modifiable factor in OA management and prevention. The protective effect of folate against OA progression, as indicated in both studies, suggests that folate supplementation could be a beneficial intervention in OA in reducing the risk or severity of OA in critical joints, underlining its role in preserving the integrity of chondrocytes and synoviocytes [20, 21]. On the other hand, the identification of succinate dehydrogenase (SDH)/complex II as a major site for ROS production under FD conditions offers a potential therapeutic target to mitigate these effects [20].

Considering our results, checking folate levels in OA patients could be recommended as part of the evaluation process. While this does not establish a causal relationship due to the cross-sectional nature of our study, it does suggest a potential area for future research and intervention.

Our study had several limitations. First, the sample size was relatively small. Our second limitation is the lack of consideration for varus and valgus alignments in relation to OA severity. These biomechanical factors significantly impact joint stress, pain, and motion, and their exclusion from analysis may limit the comprehensiveness of our findings. Future research should incorporate these mechanical aspects to provide a more holistic understanding of OA progression and treatment efficacy. Lastly, although we focused on the role of folate in OA, a comprehensive understanding of vitamin metabolism, including aspects such as mean corpuscular volume (MCV) and homocysteine levels, could provide a more thorough insight into the patients’ metabolic state.

Conclusions

Our study highlights a significant correlation between folate deficiency and increased severity of OA, which is evident in radiological and clinical assessments. These findings suggest that folate plays a key role in OA pathogenesis and could be a modifiable factor in its management.

-

Research ethics: The protocol of the present study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Zabol University of Medical Sciences (IR.ZBMU.REC.1400.057).

-

Informed consent: All patients provided written informed consent form prior to participation.

-

Author contributions: All authors provided substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; all authors drafted the article or revised it critically for important intellectual content; all authors gave final approval of the version of the article to be published; and all authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

-

Competing interests: None declared.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: The raw data can be obtained on request from the corresponding author.

References

1. Felson, DT. The sources of pain in knee osteoarthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2005;17:624–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.bor.0000172800.49120.97.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Dieppe, PA, Lohmander, LS. Pathogenesis and management of pain in osteoarthritis. Lancet 2005;365:965–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(05)71086-2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Sanghi, D, Avasthi, S, Mishra, A, Singh, A, Agarwal, S, Srivastava, RN. Is radiology a determinant of pain, stiffness, and functional disability in knee osteoarthritis? A cross-sectional study. J Orthop Sci 2011;16:719–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00776-011-0147-y.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Zhang, W, Nuki, G, Moskowitz, RW, Abramson, S, Altman, RD, Arden, NK, et al.. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis: part III: changes in evidence following systematic cumulative update of research published through January 2009. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2010;18:476–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2010.01.013.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Sharma, L, Song, J, Felson, DT, Cahue, S, Shamiyeh, E, Dunlop, DD. The role of knee alignment in disease progression and functional decline in knee osteoarthritis. J Am Med Assoc 2001;286:188–95. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.286.2.188.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Felson, DT, Goggins, J, Niu, JB, Zhang, YQ, Hunter, DJ. The effect of body weight on progression of knee osteoarthritis is dependent on alignment. Arthritis Rheum 2004;50:3904–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.20726.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Moyer, RF, Birmingham, TB, Chesworth, BM, Kean, CO, Giffin, JR. Alignment, body mass and their interaction on dynamic knee joint load in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2010;18:888–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2010.03.017.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Lee, R, Kean, WF. Obesity and knee osteoarthritis. Inflammopharmacology 2012;20:53–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10787-011-0118-0.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Ayral, X, Pickering, EH, Woodworth, TG, Mackillop, N, Dougados, M. Synovitis: a potential predictive factor of structural progression of medial tibiofemoral knee osteoarthritis e results of a 1 year longitudinal arthroscopic study in 422 patients. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2005;13:361–7.10.1016/j.joca.2005.01.005Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Inoue, R, Ishibashi, Y, Tsuda, E, Yamamoto, Y, Matsuzaka, M, Takahashi, I, et al.. Knee osteoarthritis, knee joint pain and aging in relation to increasing serum hyaluronan level in the Japanese population. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2011;19:51–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2010.10.021.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Dainese, P, Wyngaert, KV, De Mits, S, Wittoek, R, Van Ginckel, A, Calders, P. Association between knee inflammation and knee pain in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2022;30:516–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2021.12.003.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Korchi, AM, Cengarle-Samak, A, Okuno, Y, Martel-Pelletier, J, Pelletier, JP, Boesen, M, et al.. Inflammation and hypervascularization in a large animal model of knee osteoarthritis: imaging with pathohistologic correlation. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2019;30:1116–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvir.2018.09.031.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Conaghan, PG, Cook, AD, Hamilton, JA, Tak, PP. Therapeutic options for targeting inflammatory osteoarthritis pain. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2019;15:355–63. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41584-019-0221-y.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Jones, P, Lucock, M, Scarlett, CJ, Veysey, M, Beckett, EL. Folate and inflammation–links between folate and features of inflammatory conditions. J Nutr Intermed Metab 2019;18:100104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnim.2019.100104.Search in Google Scholar

15. Kolb, AF, Petrie, L. Folate deficiency enhances the inflammatory response of macrophages. Mol Immunol 2013;54:164–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molimm.2012.11.012.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Jones, P, Lucock, M, Scarlett, CJ, Veysey, M, Beckett, EL. Folate and inflammation-links between folate and features of inflammatory conditions. J Nutr Intermed Metab 2019;18:100104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnim.2019.100104.Search in Google Scholar

17. Yakut, M, Üstün, Y, Kabaçam, G, Soykan, I. Serum vitamin B12 and folate status in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Eur J Intern Med 2010;21:320–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2010.05.007.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Chow, YY, Chin, KY. The role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis. Mediators Inflamm 2020;2020:8293921. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8293921.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

19. Xu, H, Shin, MH, Kang, JH, Choi, SE, Park, DJ, Kweon, SS, et al.. Folate deficiency is associated with increased radiographic severity of osteoarthritis in knee joints but not in hand joints. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2023;41:1149–54. https://doi.org/10.55563/clinexprheumatol/69k9xr.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Hsu, HC, Chang, WM, Wu, JY, Huang, CC, Lu, FJ, Chuang, YW, et al.. Folate deficiency triggered apoptosis of synoviocytes: role of overproduction of reactive oxygen species generated via NADPH oxidase/mitochondrial complex II and calcium perturbation. PLoS One 2016;11:e0146440. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0146440.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

21. Hong, H, Chen, L, Zhong, Y, Yang, Z, Li, W, Song, C, et al.. Associations of homocysteine, folate, and vitamin B12 with osteoarthritis: a Mendelian randomization study. Nutrients 2023;15:1636. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15071636.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- General

- Review Article

- Research integrity and academic medicine: the pressure to publish and research misconduct

- Medical Education

- Original Article

- Perception of opioids among medical students: unveiling the complexities and implications

- Commentary

- Diversity in osteopathic medical school admissions and the COMPASS program: an update

- Musculoskeletal Medicine and Pain

- Original Article

- The association of folate deficiency with clinical and radiological severity of knee osteoarthritis

- Neuromusculoskeletal Medicine (OMT)

- Original Article

- The effects of osteopathic manipulative treatment on pain and disability in patients with chronic low back pain: a single-blinded randomized controlled trial

- Pediatrics

- Original Article

- Associations of social determinants of health and childhood obesity: a cross-sectional analysis of the 2021 National Survey of Children’s Health

- Clinical Image

- Calciphylaxis

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- General

- Review Article

- Research integrity and academic medicine: the pressure to publish and research misconduct

- Medical Education

- Original Article

- Perception of opioids among medical students: unveiling the complexities and implications

- Commentary

- Diversity in osteopathic medical school admissions and the COMPASS program: an update

- Musculoskeletal Medicine and Pain

- Original Article

- The association of folate deficiency with clinical and radiological severity of knee osteoarthritis

- Neuromusculoskeletal Medicine (OMT)

- Original Article

- The effects of osteopathic manipulative treatment on pain and disability in patients with chronic low back pain: a single-blinded randomized controlled trial

- Pediatrics

- Original Article

- Associations of social determinants of health and childhood obesity: a cross-sectional analysis of the 2021 National Survey of Children’s Health

- Clinical Image

- Calciphylaxis