Abstract

Context

Thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS) symptoms are prevalent and often confused with other diagnoses. A PubMed search was undertaken to present a comprehensive article addressing the presentation and treatment for TOS.

Objectives

This article summarizes what is currently published about TOS, its etiologies, common objective findings, and nonsurgical treatment options.

Methods

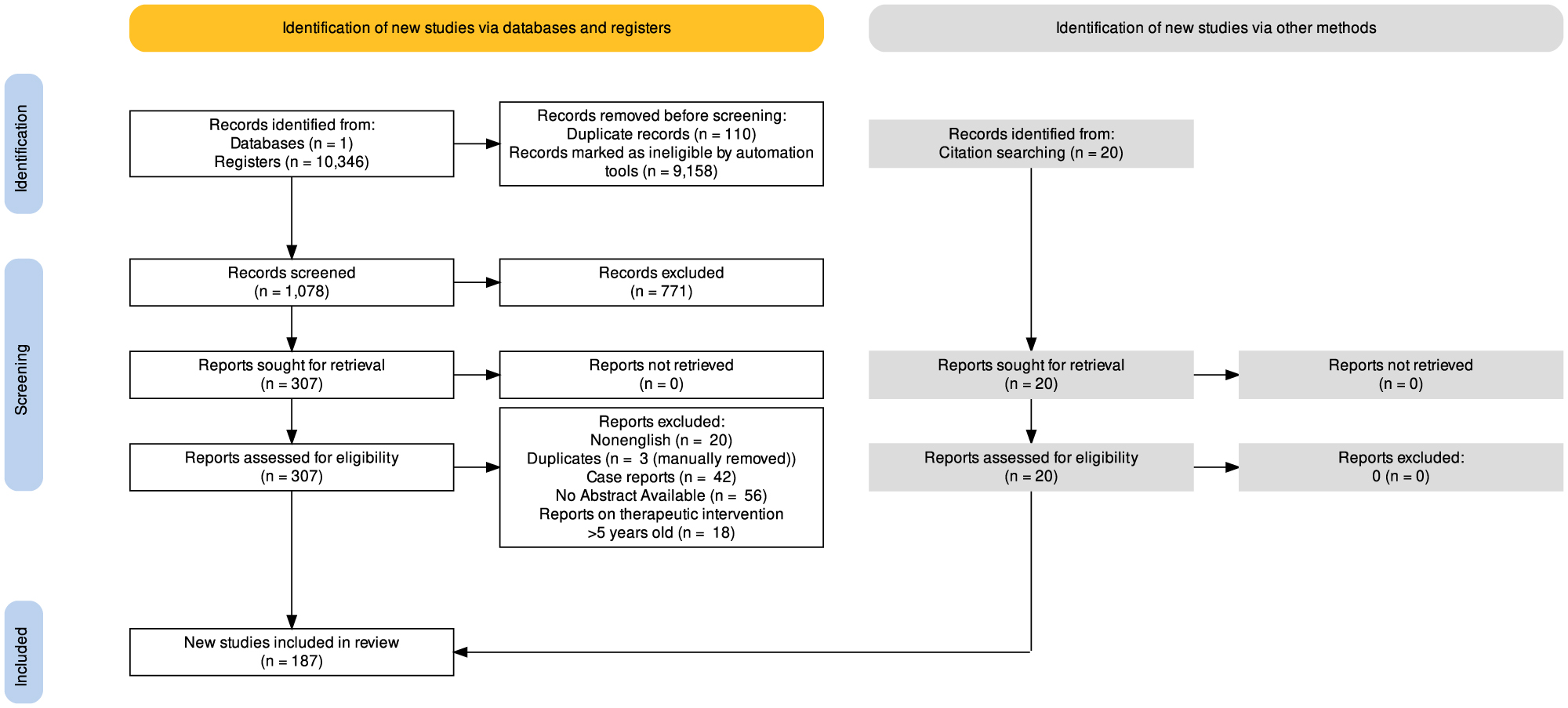

The PubMed database was conducted for the range of May 2020 to September 2021 utilizing TOS-related Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms. A Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) systematic literature review was conducted to identify the most common etiologies, the most objective findings, and the most effective nonsurgical treatment options for TOS.

Results

The search identified 1,188 articles. The automated merge feature removed duplicate articles. The remaining 1,078 citations were manually reviewed, with articles published prior to 2010 removed (n=771). Of the remaining 307 articles, duplicate citations not removed by automated means were removed manually (n=3). The other exclusion criteria included: non-English language (n=21); no abstracts available (n=56); and case reports of TOS occurring from complications of fractures, medical or surgical procedures, novel surgical approaches, or abnormal anatomy (n=42). Articles over 5 years old pertaining to therapeutic intervention (mostly surgical) were removed (n=18). Articles pertaining specifically to osteopathic manipulative treatment (OMT) were sparse and all were utilized (n=6). A total of 167 articles remained. The authors added a total of 20 articles that fell outside of the search criteria, as they considered them to be historic in nature with regards to TOS (n=8), were related specifically to OMT (n=4), or were considered sentinel articles relating to specific therapeutic interventions (n=8). A total of 187 articles were utilized in the final preparation of this manuscript. A final search was conducted prior to submission for publication to check for updated articles. Symptoms of hemicranial and/or upper-extremity pain and paresthesias should lead a physician to evaluate for musculoskeletal etiologies that may be contributing to the compression of the brachial plexus. The best initial provocative test to screen for TOS is the upper limb tension test (ULTT) because a negative test suggests against brachial plexus compression. A positive ULTT should be followed up with an elevated arm stress test (EAST) to further support the diagnosis. If TOS is suspected, additional diagnostic testing such as ultrasound, electromyography (EMG), or magnetic resonance imaging/magnetic resonance angiography (MRI/MRA) might be utilized to further distinguish the vascular or neurological etiologies of the symptoms. Initial treatment for neurogenic TOS (nTOS) is often conservative. Data are limited, therefore there is no conclusive evidence that any one treatment method or combination is more effective. Surgery in nTOS is considered for refractory cases only. Anticoagulation and surgical decompression remain the treatment of choice for vascular versions of TOS.

Conclusions

The most common form of TOS is neurogenic. The most common symptoms are pain and paresthesias of the head, neck, and upper extremities. Diagnosis of nTOS is clinical, and the best screening test is the ULTT. There is no conclusive evidence that any one treatment method is more effective for nTOS, given limitations in the published data. Surgical decompression remains the treatment of choice for vascular forms of TOS.

Compression of the neurovascular bundle supplying the upper extremities has been described in the literature under various terms. In 1861, Coote [1] was the first to excise a cervical rib through a supraclavicular approach to relieve the symptoms of compression of these structures. The term “thoracic outlet syndrome” (TOS) was first described in the literature by Peet et al. [2] in 1956, and in 2017, Otoshi et al. [3] reported that 32.8% of 1,288 male high school baseball players ages 15 to 17 who were screened for TOS during a preparticipation physical examination had symptomatic TOS. Given the higher-than-expected prevalence of symptoms reported by Otoshi et al. [3], a systematic literature review was conducted to identify the most common objective findings (clinical and diagnostic testing) and the most effective nonsurgical treatment options for TOS with the intent of presenting a comprehensive article addressing the following questions.

What are the common etiologies for TOS?

What are the most common objective findings for TOS in a clinical setting (e.g., physical exam, special tests, and diagnostic studies)?

What common treatments are available for TOS?

Methods

Following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines for systematic review (Figure 1), the authors conducted a search on PubMed spanning March 2020 through September 2021 utilizing the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms noted in Table 1. Because this is a literature review, it was IRB exempt and no funding or grants were utilized during this study. There were six authors involved in this process (AC, AG, AD, RF, RC, and VO). The articles were categorized into subtopics based on the questions posed and distributed to the individual authors as follows; AD and AC, common etiologies, and special tests; RC, radiographic studies and surgical treatments; RF and AG, OMM and manual treatments; VO, RF, and AC other treatment modalities. Articles from 2010 through 2020 were included in the final review process, and the authors were asked to look specifically at articles that helped answer the stated questions. The exclusion criteria included: citations without abstracts; non-English articles; case reports of TOS occurring from complications of fractures, medical or surgical procedures, reports of novel surgical approaches, or abnormal anatomy; and articles pertaining to treatment that were greater than 5 years old. The authors met every 6–8 weeks via Zoom or corresponded via email from May 2020 to December 2020 to discuss their progress and review any articles that were questionable. Disagreements were handled by reviewing the PRISMA guidelines and the original stated goals of the project, and by final review of the article in question by primary authors (AC and AG). The authors contributed to the writing of their assigned sections, and the final manuscript was compiled by AC and edited by AG, AD, and RF. Photos of special testing were provided by authors AD and RF, and consent from them was obtained to utilize their images. Given the large number of abstracts obtained from our original search on PubMed, no further databases were utilized.

Thoracic outlet preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram.

MeSH terms used.

| Thoracic outlet syndrome | Brachial plexus syndrome | Effort vein thrombosis | Cervical rib syndrome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pectoralis minor syndrome | Arterial thoracic outlet syndrome | Paget-Schroetter syndrome | Costoclavicular syndrome |

| Venous thoracic outlet syndrome | Scalene anticus syndrome | Hyperabduction syndrome | Shoulder hand syndrome |

| Treatment of thoracic outlet syndrome | Osteopathic manipulation for thoracic outlet syndrome | Diagnosis of thoracic outlet syndrome | Brachial plexus compression syndrome |

Results

An initial search on PubMed in May 2020 utilizing the MeSH terms listed in Table 1 without a specific date range identified a total of 10,346 articles. The same search was performed in June 2020 utilizing a date range from 2000 to 2021, and 1,188 articles were identified. Utilizing the PubMed Merge feature, 110 duplicates were identified and removed automatically. The remaining 1,078 articles were manually reviewed by the authors as stated in the Methods section, and those published prior to 2010 were removed (n=771). The remaining 307 articles were further reviewed, and duplicates not previously removed by automated means were removed manually (n=3). Articles were then excluded for the following reasons: non-English language (n=21); no abstracts available (n=56); and case reports of TOS occurring from complications of fractures, medical, or surgical procedures, reports of novel surgical approaches, or abnormal anatomy (n=42). Articles greater than 5 years old pertaining to therapeutic intervention (mostly surgical) were removed (n=18); however, articles pertaining specifically to osteopathic manipulative treatment (OMT) were sparse, and all references were utilized, regardless of publication date (n=6). After this review process, a total of 167 articles remained. The authors added a total of 20 articles that fell outside of the search criteria, because they considered them to be historic in nature with regard to TOS (n=8); these articles were related specifically to OMT (n=4) or were considered sentinel articles relating to specific therapeutic interventions (both medical and surgical) (n=8). A total of 187 articles were utilized in the final preparation of this manuscript. A final PubMed search was conducted in September 2021 prior to submission for publication to check for updated citations, and none were added. One article was added to the research library during the revision process, because it was published concomitant to our last search.

Etiology of thoracic outlet syndrome

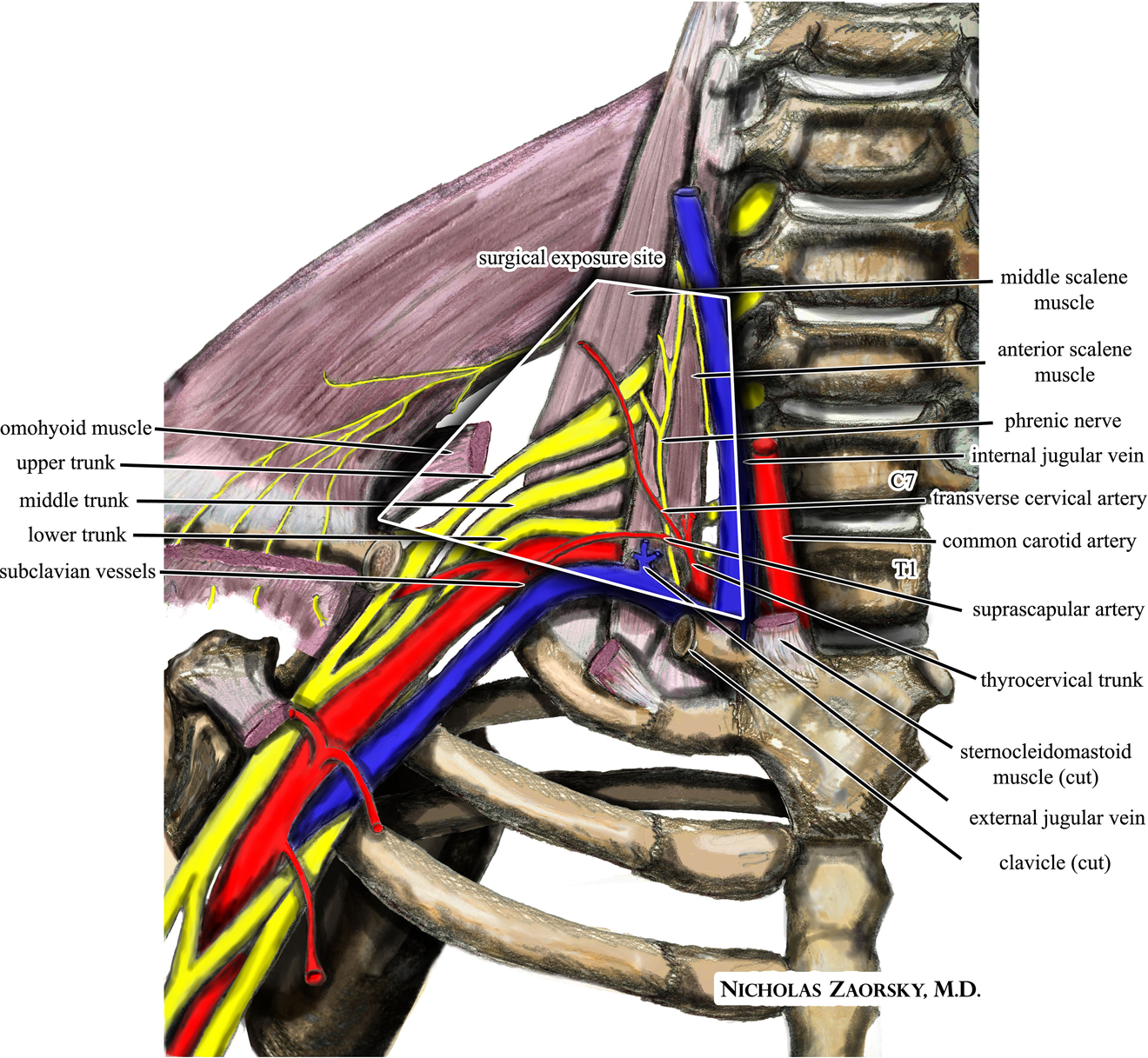

TOS is a global term utilized to describe a variety of symptoms associated with compression of the neurovascular bundle that traverses the space defined by the cervical column, upper ribs, and clavicle. The compression of these structures can lead to a multitude of clinical symptoms affecting the shoulder girdle, neck, and upper extremity (Figure 2) [4]. Anatomically, compression of the neurovascular bundle traditionally occurs at three specific areas with distinct landmarks:

Scalene triangle: compression occurs as the brachial plexus and traverses the space between the middle and anterior scalene muscles and the first rib.

Costoclavicular space: compression occurs in the space between the clavicle and the first rib.

Pectoralis minor space: the area formed from the pectoralis minor muscle anteriorly and the rib cage posteriorly. This area is not considered to be part of the thoracic outlet proper; however, entrapment of the neurovascular bundle within this space is included in the etiologies of the clinical syndromes associated with TOS and may be as common as entrapment at the scalene triangle [5].

An illustration of the relevant neurovascular anatomy in the anterior supraclavicular neurosurgical approach to the brachial plexus and subclavian vessels for thoracic outlet syndrome. This file is licensed under the creative commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license. Source: Nicholas Zaorsky, MD. Zaorsky, M. Thoracic outlet. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Wikipedia_medical_illustration_thoracic_outlet_syndrome_brachial_plexus_anatomy_with_labels.jpg.

(A) Upper limb tension test (ULTT) position 1. The patient may be seated or standing with arms abducted to 90° and elbows extended. (B) ULTT position 2. While in position 1, the patient is asked to extend their wrists. (C) ULTT position 3. The patient is shown with his head tilted to the right; repeat with head tilted to left to complete exam. (D) Elevated arm stress test (EAST) position 1. The patient may be seated or standing with arms abducted to 90° and elbows flexed. The shoulders should be externally rotated. (E) EAST position 2. Instruct the patient to continuously open and close their fists. (F) Adson’s test. While seated, the patient’s arm is abducted and externally rotated with the elbow extended. The examiner monitors the patient’s radial pulse as the patient is instructed to take a deep breath while rotating and slightly extending the head toward the side being tested.

The common etiologies of TOS have been classified as being either congenital, traumatic, or functionally acquired with the following being the most encountered:

Congenital: cervical or first rib.

Traumatic: whiplash injuries, motor vehicle accidents.

Functional: vigorous, repetitive upper-extremity activity [6].

Incidence of TOS

The clinical presentation divides TOS into three separate categories: neurogenic (nTOS), venous (vTOS), and arterial (aTOS). Based on surgical data collected over a 40-year period and encompassing more than 2,500 cases, the incidence of TOS has been reported as 95.0% nTOS, 3.0% vTOS, and 1.0% aTOS [7, 8]. Data published in 2020 by Illig et al. [9, 10] estimate the incidence of nTOS to be 25 per year in a metropolitan area of one million based on retrospective review of 526 patients referred for symptoms of TOS. In contrast, the prevalence of TOS in certain subpopulations has been estimated to be much higher. In 2017, Otoshi et al. [3] noted that 32.8% of 1,288 male baseball players (ages 15–17) had clinical symptoms of TOS on physical exam utilizing provocative maneuvers; however, the data regarding definitive diagnostic testing to confirm TOS in these patients were not discussed [3].

There were no studies that specifically looked at the incidence or prevalence of TOS based on age, gender, or ethnicity; however, the following observations have been noted; nTOS is more common in women; vTOS is more common in men; and aTOS affects both genders equally [6, 8].

Clinical presentation

Patients present with a constellation of symptoms that may manifest as pure neurological symptoms or vascular symptoms or a combination of both. Of the three forms of TOS, nTOS has been reported to represent up to 95.0% of cases [7, 8]. As such, early recognition of the signs and symptoms of nTOS is an important step in preventing disease progression and developing a proper treatment plan. Arriving at a diagnosis of nTOS begins with a proper history and physical examination, followed by special tests to confirm the diagnosis. Patients presenting with nTOS often have a history of neck trauma preceding their symptoms, with automobile accidents, postural decompensation, and repetitive work stress being the most common [11, 12].

Biomechanical factors should be taken into consideration and can serve as diagnostic tools, particularly those of the shoulder joint and pelvis. Muscle imbalance, such as hypertrophied pectoralis minor or hypertrophied scalene and sternocleidomastoid muscles, can directly contribute to the entrapment of the brachial plexus, subclavian artery, and vein. Pelvic alignment affects posture, including head, neck, and upper thoracic spine alignment, thus indirectly contributing to the function of the thoracic outlet. For example, an anterior pelvic tilt due to tight hip flexors may cause an increased lordosis of the lumbar spine and a compensatory kyphosis of the thoracic spine. This may contribute to the shoulders being rolled forward with shortening of the pectoralis minor muscles and tightening of the cervical muscles, ultimately entrapping the cervical brachial plexus and vasculature [12, 13]. Evaluating and treating overall posture and addressing muscle imbalances may help minimize entrapment and ease the symptoms of TOS. A trauma history can help focus the examination. For example, in patients who have undergone whiplash injury, abrupt flexion-extension motion may lead to instability of the atlantoaxial joint, causing the surrounding sternocleidomastoid and scalene muscles to shorten to compensate for the instability. Such a muscle imbalance could potentially lead to entrapment of the thoracic outlet structures [12].

Data on the incidence of specific symptoms was variable and often limited by small sample sizes; however, Sanders, Hammond, and Rao [8] reported the following incidence of symptoms with regard to the patients studied (n=50): paresthesias (98.0%), trapezius pain (92.0%), supraclavicular pain (76.0%), chest pain (72.0%), shoulder and arm pain (88.0%), and occipital headaches (76.0%). Balderman et al. [14] reported that the most common symptoms were upper-extremity pain (99.0%), the exacerbation of symptoms by arm elevation (97.0%), localized supraclavicular or subcoracoid tenderness to palpation (96.0%), and upper-extremity and/or hand paresthesias (94.0%) in new patient referrals (n=183, mean age 37.1). In their study, 107 (71.0%) of the patients were women [14].

Although the presenting symptoms associated with nTOS are highly variable and depend on the underlying etiology, the most common principal symptom is pain in the neck, upper back, shoulder, arm, and/or hand [8, 14]. This pain should be nonradicular in nature and be present during activities, as well as at rest [15]. Lastly, the pain should be reproducible by provocative testing, which is discussed below.

The presenting pain pattern can be utilized to further identify nTOS as that occurring due to compression of the upper (C5-C7) or lower (C8-T1) trunks of the brachial plexus. While patients can present with both upper and lower plexus involvement, Atasoy [16] noted that the lower and combined types comprised 85–90% of all TOS cases (n=750) presenting for surgical intervention of the same.

In patients presenting with upper plexus compression, symptoms are often supraclavicular with radiation to the ipsilateral face, head, upper chest, periscapular region, or radial nerve distribution [17]. Additionally, these patients may complain of hemicranial headaches and “stuffy” ears despite a negative otologic examination [18].

Patients with compression of the lower plexus, which is more common, will often present with complaints of pain along the ulnar side of the arm and hand accompanied by symptoms in the anterior shoulder and axilla [17]. Additionally, lower plexus injury may cause pain radiation into the anterior chest that can mimic cardiac angina, occipital headaches, and a sleeve-like numbness that awakens patients during the night [18].

Numbness and/or paresthesia are common findings in patients with nTOS. Sanders et al. [8] found paresthesia to be present in 98.0% of the patients studied (n=50), with 58.0% of those involving all five fingers, 26.0% involving the fourth and fifth fingers, and 14.0% involving the first to third fingers. Patients will often describe this as a feeling of “numbness” or “tingling.”

Although isolated nTOS is not associated with compression of the subclavian artery, patients still may present with Raynaud’s phenomenon, which presents as a coolness of the hand with associated color changes. In contrast to aTOS, in which color changes and other symptoms are caused by arterial ischemia, Raynaud’s in the setting of nTOS is thought to be caused by an overactive sympathetic nervous system response triggered by irritation of sympathetic nerve fibers that run along the nerve roots of C8 and/or T1 and the lower trunk of the brachial plexus [8]. This anatomical relationship provides an opportunity for the use of manipulative treatment modalities that aim to decrease sympathetic tone to the upper limb.

Special tests

Within the physical examination, numerous special tests have been utilized to arrive at a diagnosis of nTOS. Of these, the most commonly utilized are the elevated arm stress test (EAST), upper limb tension test (ULTT), and Adson’s test [19]. It is important to note that although a single positive provocative test is not enough to diagnose nTOS, a negative ULTT provides strong evidence against the diagnosis of brachial plexus compression [20]. Supporting this are the results from Sanders et al. (n=50) [8], showing that of those patients with positive physical findings consistent with nTOS, 98.0% had a positive ULTT. Recommendations set forth by the Journal of Vascular Surgery in 2016, which set to standardize the diagnosis of nTOS, state that arriving at a diagnosis of nTOS is best achieved through the use of ULTT and EAST tests [9]. Although the Adson’s test when utilized alone has been shown to have a low specificity, Gillard et al. [21] showed a rise of the diagnostic specificity to 82.0% (n=48) when utilized in combination with the EAST test. A positive EAST test and Adson’s test may indicate vascular compression within the scalene triangle but should be interpreted with caution. Each of these tests are described in more detail in Table 2.

Most common clinical tests for thoracic outlet syndrome.

| Test | How to perform test | Patient response | Interpretation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper limb tension test (ULTT) | Position 1 |

|

|

|

| Position 2 |

|

|||

| Position 3 |

|

|||

| Elevated arm stress test (EAST) |

|

|

||

| Adson’s test |

|

|

|

|

-

nTOS, neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome.

Osteopathic structural exam

An osteopathic structural evaluation can reveal direct and indirect myofascial contributors to the TOS symptoms. A common component of postural decompensation that contributes to TOS begins with shoulder protraction in the anterior/inferior direction, which shortens the sternocleidomastoid and the scalene and pectoral muscles, and elevates the upper ribs, narrowing the costoclavicular space [22]. Cervical spine somatic dysfunctions can create facilitation of the nerve roots and affect the tone of the cervicobrachial musculature [23]. Kyphoscoliosis will increase the lordosis of the cervical spine and compress the thoracic outlet space. Thoracic vertebral somatic dysfunctions can create facilitation of the sympathetic innervation of the upper extremities, leading to increased muscular tone and vasoconstriction. Extension somatic dysfunctions of the upper thoracic spine are often associated with TOS symptoms of upper-extremity numbness. Sacral base dysfunction can cause compensatory lumbar scoliosis, which can increase the thoracic kyphosis. Like most structural diagnoses, thoracic outlet symptom etiology is often multifactorial [23]. Tissue texture changes and restrictions in the cervical spine from C2-C7, thoracic T1, rib 1, thoracic inlet, clavicle, and scalene muscle should be evaluated based on patient presentation.

Diagnostic testing for clinically suspected TOS

The diagnosis of TOS begins with a thorough history and physical exam. Imaging and electromyographic (EMG) studies are helpful to confirm the diagnosis, delineate between neurogenic and vascular TOS (arterial and venous), identify the site of compression, and rule out bony anatomical anomalies [6].

Radiographic studies

Initially, plain radiographs of the chest and cervical region may be performed to rule out anatomical abnormalities and structural variants such as cervical ribs, malunion of clavicular fractures, elongated transverse processes, or tumors within the thoracic cavity [15, 19, 24].

Further investigation requires the use of ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Per the 2015 American College of Radiology Appropriateness Criteria for imaging in the diagnosis of TOS, ultrasound is a cost-effective tool and visualization of the vessels is a strength, but the sonographic diagnosis of compressive effects upon the brachial plexus is challenging and may miss regional pathology, such as a Pancoast tumor or cervical spondylopathy [25]. Noncontrast MRI can be sufficient to diagnose nTOS, whereas magnetic resonance (MR) or CT angiography are the best modalities to confirm venous or arterial TOS [25].

To diagnose a vascular form of TOS with magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), there must be evidence of endothelial damage such as thrombi in the subclavian or axillary vein, fixed stenosis at a site of compression, or engorged collateral veins for vTOS. For aTOS, there is usually an aneurysm in the subclavian artery, fixed stenosis at the compression site, thrombi, signs of emboli in the corresponding extremity, or larger than normal collateral arteries. A major indicator of both vTOS and aTOS is vessel narrowing with abduction of the affected arm [26].

It is important to note that images should be taken in both the neutral position (supine with arms to the side) and in a hyperabducted position (arms above head and externally rotated) for the diagnosis of TOS. Narrowing of the subclavian vein diameter by 50% and subclavian artery by 30% during abduction is diagnostic of vTOS and aTOS, respectively [27].

nTOS is mostly a clinical diagnosis, although edema and the loss of fat surrounding the brachial plexus with arm abduction is usually evident on MRI [26].

Electrodiagnostic studies

Patients presenting with TOS can present with upper and lower trunk or mixed findings, and the importance of a complete clinical history and physical examination cannot be overstated. Once anatomical variants, structural abnormalities, and direct compression of the brachial plexus have been ruled out as the source of symptoms, EMG can be useful in differentiating the source of upper and lower trunk symptoms and confirming the diagnosis.

Electrodiagnostic data obtained in patients with surgically verified nTOS noted evidence of axonal loss and diminished nerve conduction amplitude in the distribution of the medial antebrachial cutaneous (MABC) nerve, which relies almost solely on fibers from T1. Abnormalities were also seen in nerve conduction of the median motor nerve, particularly the motor innervation to the thenar muscles, which rely mostly on T1 fibers and less on those from C8 [28].

Given these findings, electrodiagnostic testing appears useful in confirming the clinical findings consistent with lower trunk involvement. A comprehensive electrodiagnostic examination of the involved limb with contralateral comparison studies is imperative to diagnose this disorder accurately [28]. For example, in a patient presenting with numbness and paresthesia over the ulnar portion of the forearm, the expectation would be to find a diminished amplitude in MABC nerve conduction and abnormalities in the median motor distribution. Similarly, abnormalities in the median motor nerve supply are often seen on nerve conduction studies in patients with thenar atrophy because the thenar muscles rely primarily on T1 fibers [29].

Treatment options for TOS

Treatment for TOS may begin with conservative measures; however, arterial and venous forms often require more aggressive treatments, because they often present with signs of venous obstruction and/or limb ischemia [30]. The authors would like to point out that due to the relative rarity of TOS, reported data regarding conservative treatment options for TOS, specifically nTOS, is based primarily on retrospective clinical observations and case reports. No randomized controlled studies were noted within our search parameters.

Physical therapy

Physical therapy (PT) is one of the more popular, nonsurgical treatment choices. PT treatments begin by frequent, daily stretching of the muscles that could contribute to TOS, like the pectoralis minor, scalenes, and the other muscles of the neck and shoulder [6, 12, 20, 24, 31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39]. PT also consists of modifications to daily activities to keep symptom exacerbation at a minimum [24]. Some suggest avoiding provocative activities and arm positions, instead proposing PT programs that strengthen muscles of the pectoral girdle and help restore normal posture [40]. Postural correction and nerve glides are also utilized to provide some relief to patients [31, 35, 41, 42].

PT to strengthen weakened shoulder girdle muscles can be incorporated into the treatment plan [12, 32, 37, 39, 41], [42], [43], but is not always found to be effective, as muscle hypertrophy can contribute to further compression of the structures causing TOS symptoms [20]. In athletes, Warrick and Davis note that PT is a core component of conservative treatment for nTOS [44]. They report that activity modification is needed to limit repetitive overhead movement, with the evaluation of posture, biomechanics, and individual patterns of muscle use and tendon shortening as the focus of therapy [44].

Osteopathic manipulative medicine

OMT is another option for patients presenting with TOS; however, the literature search for TOS and OMT or osteopathic manipulation was limited, resulting in just four manuscripts and two case studies. Techniques such as high-velocity/low-amplitude, muscle energy, counterstrain, myofascial release, and the Still technique can all correct dysfunctions that are present and contributing to the TOS symptoms [45, 46].

Injections

Several articles describe the use of local anesthetics injected directly into the scalene or pectoralis minor muscles as both a diagnostic and therapeutic modality utilized specifically for nTOS [9, 15, 44]. The theory behind these injections is that these areas are common sites for compression of the brachial plexus, and the alleviation of pain utilizing these injections identifies the site of compression while potentially relieving symptoms [15].

Trigger point injections

Trigger point injections may offer relief to patients presenting with trigger point pain patterns or hypertonic muscles contributing to the compression of thoracic outlet neurovascular structures [31, 47].

Botulism injections

Botulism injections can be utilized to treat nTOS due to muscle hypertonicity. Patients whose compression is due to other causes, such as cervical rib or fibrous bands, are unlikely to respond to botulinum toxin (BoNT [Botox]) injections [48]. Botulinum injections into the scalenes may be recommended [30, 39]; however, Povlsen and Povlsen [49] concluded that there is moderate evidence to suggest that Botox injections into the scalene muscles have no benefit over placebo for improvement in pain or disability, although they may improve paresthesias in the long term in people with TOS of any type.

Ultrasound-guided deep nerve hydrodissection

Although not specific to nTOS, Lam et al. [50] reported efficacy of ultrasound-guided deep nerve hydrodissection of the stellate ganglion, brachial plexus, cervical nerve roots, and paravertebral spaces utilizing D5W as an alternative management in patients (n=26, 50% female) with complex regional pain syndrome with favorable results. Pain reduction 5 min after the last injection was 97.0% ± 6.9% in cases of acute pain and 87.7% ± 9.8% in cases of chronic pain (p=0.04) [50]. The mean improvement in the Numeric Pain Rating Scale (NPRS) at the 2-month posttreatment follow-up was 5.8 ± 1.9 points for cases of acute pain (8.0 ± 1.3 to 2.2 ± 0.7) and 6.5 ± 1.7 points for cases of chronic pain (p=0.385) [50].

Acupuncture

Hwang et al. [43] looked at traditional medicine approaches to the treatment of TOS and suggest that acupuncture has been reported to alleviate pain by the rebalancing of energy (Qi) and blood circulation in the meridians in diseases with multifactorial etiology, with positive effects on patients with TOS.

The authors would like to emphasize again that PT and OMT, as well as the other conservative therapies discussed, should not be attempted in suspected vTOS or aTOS when there are signs or symptoms of venous occlusion or limb ischemia until proper evaluation is completed.

Pharmacological treatments

Pharmacological treatments can be utilized in conjunction with the therapies described above or as standalone treatments. nTOS patients can take medications and receive nerve blocks and corticosteroids (either systemically or locally injected) to help decrease pain symptoms [6, 19, 24, 33, 37, 38, 41, 42, 51, 52]. Analgesics (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs] or opioids) have been suggested for neuropathic pain, while muscle relaxants, anticonvulsants, and/or antidepressants as adjuvant have also been suggested [43].

Patients with vTOS are often treated with anticoagulation therapy and thrombolysis [34, 36, 53, 54]. Lee et al. [55] reported outcomes in 64 patients with vTOS utilizing a treatment protocol of catheter-directed thrombolysis, anticoagulation, and decompression and resection of the first rib in those patients with persistent symptoms as follows. A total of 29 patients (45.0%) required first rib resection within the first 3 months postthrombolysis; of the 35 patients (55%) treated successfully with thrombolysis and anticoagulation, 8 (23.0%) developed a recurrent thrombotic event in the same extremity (mean follow-up 13 months) and required further intervention, whereas the remaining 27 (77.0%) remained symptom-free after a mean follow-up of 55 months.

Due to symptoms of limb ischemia and the potential for significant tissue necrosis, most treatments for aTOS are surgical, with the only preoperative intervention being a catheter-directed thrombolysis [30, 56]. In general, when considering the options for all forms of vTOS, anticoagulation alone is generally not recommended and the combination of thrombolysis, decompressive surgery, and anticoagulation has a better prognosis and overall outcome for these patients [54, 55].

Surgical interventions for thoracic outlet syndrome

Surgery is the ultimate treatment recommended if conservative interventions fail to improve nTOS or if the patient presents with a vascular form of TOS requiring immediate decompression [54, 57], [58], [59]. Surgery for the decompression of TOS can be accomplished in several ways. The two main approaches are through the axillary or supraclavicular regions. If the etiology for compression is hypertrophied scalene muscles or a cervical rib, then the supraclavicular decompression is utilized, which involves exploration of the supraclavicular brachial plexus, neurolysis, removal of fibrotic bands, scalenectomy, primary first rib resection, and overlooked cervical ribs [60]. Complication rates reported for this procedure are relatively low; however, the data are limited by the sample size and a lack of randomized control studies.

If the site of compression is closer to the axilla, which happens when the pectoralis minor attachment to the coracoid process pulls down on the branches of the brachial plexus, then the transaxillary incision is preferred [20]. The transaxillary approach is also utilized to treat TOS patients with a compression at the first rib or cervical rib.

Surgery for nTOS is recommended only after more conservative measures, such as OMT and PT, have failed to improve symptoms or when the patient begins to develop significant disability [61].

Discussion

Compression of the neurovascular bundle supplying the upper extremities has been described by various terms, but the term “thoracic outlet syndrome” (TOS) was coined 1956 and remains the current standard [2]. The most common etiologies of TOS can be classified as either congenital, traumatic, or functional [6]. There are three classifications of TOS based on the clinical presentation: neurogenic (nTOS), venous (vTOS), or arterial (aTOS), with nTOS being the most common. There is no reported data specific to the incidence or prevalence of TOS based on age, gender, or ethnicity; however, there does seem to be a consensus that nTOS is more common in females, whereas vTOS is more common in men, while aTOS occurs equally among men and women [5, 6, 8].

The most common presenting symptoms of TOS include paresthesia, trapezius pain, supraclavicular pain, chest pain, shoulder and arm pain (alone or exacerbated by arm elevation), and occipital headaches [8, 14]. Because nTOS is much more common that the other forms, it is important for primary care physicians to keep nTOS in their differential for patients presenting with cervical pain, shoulder pain, upper arm pain, and/or paresthesia [6].

Primary care physicians should recognize that arriving at the diagnosis of TOS starts with a comprehensive history and physical exam. TOS should be considered as a potential diagnosis in all patients presenting with neck, shoulder girdle, and upper-extremity pain and/or paresthesia. Once the clinical suspicion for TOS has been raised, provocative testing can be utilized as an aid in arriving at the diagnosis. The use of a single clinical provocative test in isolation has been shown to lack specificity, with a high number of false positives [15]. However, when utilized in combination, specificity values rise, and the results can be interpreted with more confidence by the practitioner [21]. Based on the available research, the best initial clinical test to aid in arriving at a diagnosis of TOS is the ULTT because a negative test suggests against brachial plexus compression [20]. A positive ULTT should be followed up with an EAST to further support the diagnosis. All patients presenting with signs and symptoms of either arterial or venous compression should be evaluated urgently to prevent limb ischemia and/or other complications from developing.

When TOS is suspected, diagnostic testing such as X-ray, ultrasound, MRI/MRA, or EMG may be utilized to further clarify the area of compression and rule out the other potential etiologies of the symptoms [6]. EMG appears useful in nTOS to confirm the clinical findings consistent with lower trunk involvement, but a comprehensive electrodiagnostic examination of the involved limb with contralateral comparison studies is imperative to diagnose this disorder accurately [28, 62]. MR and CT angiography are the preferred modalities to identify the area of compression and guide surgical treatment in vascular forms of TOS [26, 27].

The initial treatment options for nTOS are often conservative; however, anticoagulation and surgical decompression remain the treatment of choice for vascular versions of TOS [54, 57, 58]. Surgery in nTOS is considered for refractory cases only [61].

The quantity of the reported data on the effective conservative management of nTOS utilizing a single modality is limited. Based on this limitation, there is no conclusive evidence that any one method is more effective because there is a lack of randomized control studies comparing various single modalities or combinations of modalities. However, based on the available literature and the authors’ experiences, the best conservative approach to nTOS may be a combination of OMT, other manual modalities, and a home exercise regimen. Evaluating the whole body and treating individual somatic dysfunctions that may be directly or indirectly contributing to the neurovascular compression helps alleviate nTOS symptoms.

This study summarizes the clinical presentation and the appropriate clinical testing utilized for the diagnosis of TOS, and it outlines nonsurgical treatment modalities from various disciplines. It also brings attention to the fact that there are limited published studies pertaining to the use of OMT for TOS in clinical practice.

The authors encountered and recognized several limitations during this review process that suggest the need for future research regarding this topic, which hindered them from making a definitive recommendation regarding the appropriate nonsurgical treatment for TOS.

First, the authors utilized a single database (PubMed) to search for publications given the plethora of citations generated in the initial search. The various names utilized to describe TOS and the lack of uniformity in utilizing the term “thoracic outlet syndrome” (TOS) in the published literature required a careful review of the published citations to makes sure that these articles truly reflected the compression of the neurovascular bundle supplying the upper extremities and were not due to other etiologies.

Second, given the varying presentation of TOS and the multifactorial etiologies, homogeneity of the available data was lacking, because most of the data regarding incidence, patient demographics, and outcomes are based on a retrospective analysis of surgical cases from individual practices and/or hospital databases. There is also a deficiency in the reporting of the incidence of TOS with regards to gender, ethnicity, and etiology because most studies cite the same article by Sanders, Hammond, and Rao [8], which focused on a retrospective analysis of surgical cases within the same practice. The paucity of data on the incidence, demographics, and outcomes in patients with TOS treated nonoperatively presents a challenge when attempting to develop standardized diagnostic criteria and treatment protocols applicable to the general population.

Finally, Otoshi et al. [3] was able to provide evidence that the inclusion of special testing for TOS in a specific population suggested a higher incidence of TOS than what had been previously reported, but these cases were not confirmed with follow-up diagnostic testing. This study brought attention to the use of special testing in populations at risk for the development of TOS, but more definitive data are needed to determine the overall incidence of TOS in specific patient populations.

Per the authors’ experiences, TOS is most likely being addressed and treated by clinicians without being labeled as TOS. Uniformity of diagnostic terminology is needed, and the lack of randomized control studies comparing nonoperative treatment options and outcomes for TOS highlights the need for future research addressing these issues.

Conclusions

The most common etiologies of TOS can be classified as either congenital, traumatic, or functional. There are three classifications of TOS based on the clinical presentation; neurogenic (nTOS), venous (vTOS), and arterial (aTOS), with nTOS being the most common.

The most common presenting symptoms of TOS include paresthesia, trapezius pain, supraclavicular pain chest pain, shoulder and arm pain (alone or exacerbated by arm elevation), and occipital headaches. It is important for physicians to keep TOS in their differential for patients presenting with head, cervical, shoulder, or upper arm pain and/or paresthesia. Early identification of TOS in a patient presenting with shoulder girdle and upper-extremity pain with or without numbness can help treat the disorder and/or prevent progression and worsening severity. Arriving at the diagnosis of TOS starts with a comprehensive history and physical exam. The ULTT appears to be the best screening tool for TOS, so primary care physicians should consider adding this test to their physical exam when evaluating patients with shoulder girdle and upper-extremity pain. Additional diagnostic testing such as X-ray, ultrasound, MRI/MRA, or EMG may be utilized if needed to further clarify the area of compression and rule out other potential etiologies of the symptoms. Patients presenting with signs and symptoms of either arterial or venous compression should be evaluated urgently to prevent limb ischemia and/or other complications from developing. A combination of conservative therapeutic modalities (e.g., PT, OMT, therapeutic injections) for the treatment of nTOS is recommended, although research is lacking as to which one is the most effective modality.

-

Research funding: None reported.

-

Author contributions: All authors provided substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; A.C.C., A.G., A.D., and R.F. drafted the article or revised it critically for important intellectual content; A.C.C. and A.G. gave final approval of the version of the article to be published; and all authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

-

Competing interests: None reported.

References

1. Coote, ST. Bartholomew’s Hospital. Good recovery in the case of recent removal of an exostosis from the transverse process of one of the cervical vertebræ. Article. Lancet 1861;77:409. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(02)45595-X.Search in Google Scholar

2. Peet, RM, Henriksen, JD, Anderson, TP, Martin, GM. Thoracic-outlet syndrome: evaluation of a therapeutic exercise program. Proc Staff Meet Mayo Clin 1956;31:281–7.Search in Google Scholar

3. Otoshi, KSK, Kato, K, Sato, R, Igari, T, Kaga, T, Shishido, H, et al.. The prevalence and characteristics of thoracic outlet syndrome in high school baseball players. Health 2017;9:1223–34. https://doi.org/10.4236/health.2017.98088.Search in Google Scholar

4. Zaorsky, M. Thoracic outlet. Available from: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php? title=File:Wikipedia_medical_illustration_thoracic_outlet_syndrome_brachial_plexus_anatomy_with_labels.jpg&oldid=569109684.Search in Google Scholar

5. Sanders, R, Thoracic outlet syndrome: general considerations. Rutherford’s Vascular Surgery 9th Edition, chapter 120. Netherlands, Amsterdam: Elsevier Inc.; 2019:1607–18 pp.Search in Google Scholar

6. Jones, MR, Prabhakar, A, Viswanath, O, Uritis, I, Green, J, Kendrick, J, et al.. Thoracic outlet syndrome: a comprehensive review of pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Pain Ther 2019;8:5–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40122-019-0124-2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

7. Hussain, MA, Aljabri, B, Al-Omran, M. Vascular thoracic outlet syndrome. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2016;28:151–7. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.semtcvs.2015.10.008.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Sanders, RJ, Hammond, SL, Rao, NM. Diagnosis of thoracic outlet syndrome. J Vasc Surg 2007;46:601–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2007.04.050.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Illig, KA, Donahue, D, Duncan, A, Freischlag, J, Gelabert, H, Johansen, K, et al.. Reporting standards of the Society for Vascular Surgery for thoracic outlet syndrome. J Vasc Surg 2016;64:e23-35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2016.04.039.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Illig, KA, Rodriguez-Zoppi, E, Bland, T, Muftah, M, Jospitre, E. The incidence of thoracic outlet syndrome. Ann Vasc Surg 2021;70:263–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avsg.2020.07.029.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Abdallah, M, Wehbe, MR, Elias, E, Kutoubi, MA, Sfeir, R. Pectoralis minor syndrome: case presentation and review of the literature. Case Rep Surg 2016;2016:8456064. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/8456064.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

12. Levine, NA, Rigby, BR. Thoracic outlet syndrome: biomechanical and exercise considerations. Healthcare 2018;6:68. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare6020068.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

13. Sucher, BM, Heath, DM. Thoracic outlet syndrome--a myofascial variant: Part 3. Structural and postural considerations. J Am Osteopath Assoc 1993;93:340–5.10.7556/jaoa.1993.93.3.334Search in Google Scholar

14. Balderman, J, Holzem, K, Field, BJ, Bottros, M, Abuirqeba, V, et al.. Associations between clinical diagnostic criteria and pretreatment patient-reported outcomes measures in a prospective observational cohort of patients with neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome. J Vasc Surg 2017;66:533–44.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2017.03.419.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Povlsen, S, Povlsen, B. Diagnosing thoracic outlet syndrome: current approaches and future directions. Diagnostics 2018;8:92–101. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics8010021.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

16. Atasoy, E. A hand surgeon’s further experience with thoracic outlet compression syndrome. J Hand Surg Am 2010;35:1528–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhsa.2010.06.025.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Hooper, TL, Denton, J, McGalliard, MK, Brismée, JM, Sizer, PSJr. Thoracic outlet syndrome: a controversial clinical condition. Part 1: anatomy, and clinical examination/diagnosis. J Man Manip Ther 2010;18:74–83. https://doi.org/10.1179/106698110x12640740712734.Search in Google Scholar

18. Kuwayama, DP, Lund, JR, Brantigan, CO, Glebova, NO. Choosing surgery for neurogenic TOS: the roles of physical exam, physical therapy, and imaging. Diagnostics 2017;7:31–43. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics7020037.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

19. Kuhn, JE, Lebus, VG, Bible, JE. Thoracic outlet syndrome. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2015;23:222–32. https://doi.org/10.5435/jaaos-d-13-00215.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Sanders, RJ, Annest, SJ. Thoracic outlet and pectoralis minor syndromes. Semin Vasc Surg 2014;27:86–117. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.semvascsurg.2015.02.001.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Gillard, J, Pérez-Cousin, M, Hachulla, E, Remy, J, Hurtevent, JF, Vinckier, L, et al.. Diagnosing thoracic outlet syndrome: contribution of provocative tests, ultrasonography, electrophysiology, and helical computed tomography in 48 patients. Joint Bone Spine 2001;68:416–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1297-319x(01)00298-6.Search in Google Scholar

22. Sucher, BM. Thoracic outlet syndrome--a myofascial variant: Part 1. Pathology and diagnosis. J Am Osteopath Assoc 1990;90:686–96, 703–4.10.1515/jom-1990-900811Search in Google Scholar

23. Dobrusin, R. An osteopathic approach to conservative management of thoracic outlet syndromes. J Am Osteopath Assoc 1989;89:1046–50, 1053–7.10.1515/jom-1989-890814Search in Google Scholar

24. Weaver, ML, Lum, YW. New diagnostic and treatment modalities for neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome. Diagnostics 2017;7:4–11. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics7020028.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

25. Moriarty, JMBD, Broderick, DF, Cornelius, RS, Dill, KE, Francois, CJ, Gerhard-Herman, MD, et al.. ACR appropriateness criteria imaging in the diagnosis of thoracic outlet syndrome. J Am Coll Radiol 2015;12:438–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacr.2015.01.016.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

26. Raptis, CASS, Thompson, RW, Fowler, KJ, Bhalla, S. Imaging of the patient with thoracic outlet syndrome. Imaging of the patient with thoracic outlet syndrome. Radiographics 2016;36:984–1000. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.2016150221.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

27. Ghouri, MA, Gupta, N, Bhat, AP, Thimmappa, N, Saboo, S, Khandelwal, A, et al.. CT and MR imaging of the upper extremity vasculature: pearls, pitfalls, and challenges. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther 2019;9(1 Suppl):S152–73.. https://doi.org/10.21037/cdt.2018.09.15.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

28. Tsao, BE, Ferrante, MA, Wilbourn, AJ, Shields, RW. Electrodiagnostic features of true neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome. Muscle Nerve 2014;49:724–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.24066.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

29. Ferrante, MA, Ferrante, ND. The thoracic outlet syndromes: Part 1. Overview of the thoracic outlet syndromes and review of true neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome. Muscle Nerve 2017;55:782–93. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.25536.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

30. Masocatto, NO, Da-Matta, T, Prozzo, TG, Couto, WJ, Porfirio, G. Thoracic outlet syndrome: a narrative review Síndrome do desfiladeiro torácico: uma revisão narrativa. Rev Col Bras Cir 2019;46:e20192243. https://doi.org/10.1590/0100-6991e-20192243.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

31. Sanders, RJ, Annest, SJ. Pectoralis minor syndrome: subclavicular brachial plexus compression. Diagnostics 2017;7:57–68. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics7030046.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

32. Ligh, CA, Schulman, BL, Safran, MR. Case reports: unusual cause of shoulder pain in a collegiate baseball player. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2009;467:2744–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-009-0962-z.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

33. Ohman, JW, Thompson, RW. Thoracic outlet syndrome in the overhead athlete: diagnosis and treatment recommendations. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2020;13:457–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12178-020-09643-x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

34. Yagi, S, Mitsugi, M, Sangawa, T, Akaike, M, Sata, M. Paget-Schroetter syndrome in a baseball pitcher. Int Heart J 2017;58:637–40. https://doi.org/10.1536/ihj.16-447.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

35. Lee, JH, Choi, HS, Yang, SN, Cho, WM, Lee, SH, Chung, HH, et al.. True neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome following hyperabduction during sleep – a case report. Ann Rehabil Med 2011;35:565–9. https://doi.org/10.5535/arm.2011.35.4.565.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

36. Alla, VM, Natarajan, N, Kaushik, M, Warrier, R, Nair, CK. Paget-schroetter syndrome: review of pathogenesis and treatment of effort thrombosis. West J Emerg Med 2010;11:358–62.Search in Google Scholar

37. Aisen, PS, Aisen, ML. Shoulder-hand syndrome in cervical spinal cord injury. Paraplegia 1994;32:588–92. https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.1994.93.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

38. Rosen, PS, Graham, W. The shoulder-hand syndrome: historical review with observations on seventy-three patients. Can Med Assoc J 1957;77:86–91.Search in Google Scholar

39. Laulan, J. Thoracic outlet syndromes. The so-called “neurogenic types”. Hand Surg Rehabil 2016;35:155–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hansur.2016.01.007.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

40. Köknel Talu, G. Thoracic outlet syndrome. Agri 2005;17:5–9.Search in Google Scholar

41. Nichols, AW. Diagnosis and management of thoracic outlet syndrome. Curr Sports Med Rep 2009;8:240–9. https://doi.org/10.1249/JSR.0b013e3181b8556d.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

42. Rached, R, Hsing, W, Rached, C. Evaluation of the efficacy of ropivacaine injection in the anterior and middle scalene muscles guided by ultrasonography in the treatment of Thoracic Outlet Syndrome. Rev Assoc Med Bras 2019;65:982–7. https://doi.org/10.1590/1806-9282.65.7.982.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

43. Hwang, JH, Ku, S, Jeong, JH. Traditional medicine treatment for thoracic outlet syndrome: a protocol for systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Medicine (Baltim) 2020;99: e21074. https://doi.org/10.1097/md.0000000000021074.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

44. Warrick, A, Davis, B. Neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome in athletes – nonsurgical treatment options. Curr Sports Med Rep 2021;20:319–26. https://doi.org/10.1249/jsr.0000000000000854.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

45. Yuschak, E, Haq, F, Chase, S. A case of venous thoracic outlet syndrome: primary care review of physical exam provocative tests and osteopathic manipulative technique considerations. Cureus 2019;11:e4921. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.4921.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

46. Sucher, BM. Ultrasonography-guided osteopathic manipulative treatment for a patient with thoracic outlet syndrome. J Am Osteopath Assoc 2011;111:543–7. https://doi.org/10.7556/jaoa.2011.111.9.543.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

47. Alvarez, DJ, Rockwell, PG. Trigger points: diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician 2002;65:653–60.Search in Google Scholar

48. Magill, ST, Brus-Ramer, M, Weinstein, PR, Chin, CT, Jacques, L. Neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome: current diagnostic criteria and advances in MRI diagnostics. Neurosurg Focus 2015;39:E7. https://doi.org/10.3171/2015.6.Focus15219.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

49. Povlsen, BHT, Povlsen, SD. Treatment for thoracic outlet syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;11:CD007218. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007218.pub3.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

50. Lam, SKH, Reeves, KD, Cheng, AL. Transition from deep regional blocks toward deep nerve hydrodissection in the upper body and torso: method description and results from a retrospective chart review of the analgesic effect of 5% dextrose water as the primary hydrodissection injectate to enhance safety. BioMed Res Int 2017;2017:7920438.10.1155/2017/7920438Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

51. Kim, YW, Kim, Y, Kim, JM, Hong, JS, Lim, HS, Kim, HS. Is poststroke complex regional pain syndrome the combination of shoulder pain and soft tissue injury of the wrist? a prospective observational study: STROBE of ultrasonographic findings in complex regional pain syndrome. Medicine (Baltim) 2016;95:e4388. https://doi.org/10.1097/md.0000000000004388.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

52. Mowat, AG. Treatment of the shoulder-hand syndrome with corticosteroids. Ann Rheum Dis 1974;33:120–3. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.33.2.120.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

53. Mall, NA, Van Thiel, GS, Heard, WM, Paletta, GA, Bush-Joseph, C, Bach, BRJr. Paget-schroetter syndrome: a review of effort thrombosis of the upper extremity from a sports medicine perspective. Sport Health 2013;5:353–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/1941738112470911.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

54. Hangge, P, Rotellini-Coltvet, L, Deipolyi, AR, Albadawi, H, Oklu, R. Paget-Schroetter syndrome: treatment of venous thrombosis and outcomes. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther 2017;7(3 Suppl):S285–90. https://doi.org/10.21037/cdt.2017.08.15.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

55. Lee, JTKJ, Harris, EJ, Haukoos, JS, Olcott C. Long-term thrombotic recurrence after nonoperative management of Paget-Schroetter syndrome. J Vasc Surg 2006;43:1236–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2006.02.005.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

56. Moore, R, Wei Lum, Y. Venous thoracic outlet syndrome. Vasc Med 2015;20:182–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/1358863x14568704.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

57. Hempel, GK, Shutze, WP, Anderson, JF, Bukhari, HI. 770 consecutive supraclavicular first rib resections for thoracic outlet syndrome. Ann Vasc Surg 1996;10:456–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02000592.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

58. Hooper, TL, Denton, J, McGalliard, MK, Brismée, JM, Sizer, PSJr. Thoracic outlet syndrome: a controversial clinical condition. Part 2: non-surgical and surgical management. J Man Manip Ther 2010;18:132–8. https://doi.org/10.1179/106698110x12640740712338.Search in Google Scholar

59. Caputo, FJ, Wittenberg, AM, Vemuri, C, Driskill, M, Earley, J, Rastogi, R, et al.. Supraclavicular decompression for neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome in adolescent and adult populations. J Vasc Surg 2013;57:149–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2012.07.025.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

60. Terzis, JK, Kokkalis, ZT. Supraclavicular approach for thoracic outlet syndrome. Hand 2010;5:326–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11552-009-9253-0.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

61. Balderman, J, Abuirqeba, AA, Eichaker, L, Pate, C, Earley, J, Bottros, M, et al.. Physical therapy management, surgical treatment, and patient-reported outcomes measures in a prospective observational cohort of patients with neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome. J Vasc Surg 2019;70:832–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2018.12.027.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

62. Ferrante, MA, Ferrante, ND. The thoracic outlet syndromes: Part 2. The arterial, venous, neurovascular, and disputed thoracic outlet syndromes. Muscle Nerve 2017;56:663–73. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.25535.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2022 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Paralympic golf movement: the links between inclusion and treating the whole person to regain function

- General

- Original Article

- The effects of wearing a mask on an exercise regimen

- Medical Education

- Original Articles

- Promoting cultural competency and osteopathic medicine awareness among premedical students through a summer premedical rural enrichment program

- The effect of postgraduate osteopathic manipulative treatment training on practice: a survey of osteopathic residents

- Musculoskeletal Medicine and Pain

- Original Article

- Optimizing chronic pain management through patient engagement with quality of life measures: a randomized controlled trial

- Pediatrics

- Original Article

- Asthma medications in schools: a cross-sectional analysis of the Asthma Call-back Survey 2017-2018

- Public Health and Primary Care

- Review Article

- Thoracic outlet syndrome: a review for the primary care provider

- Clinical Image

- Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome

- Letter to the Editor

- Comments on “Mini-medical school programs decrease perceived barriers of pursuing medical careers among underrepresented minority high school students”

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Paralympic golf movement: the links between inclusion and treating the whole person to regain function

- General

- Original Article

- The effects of wearing a mask on an exercise regimen

- Medical Education

- Original Articles

- Promoting cultural competency and osteopathic medicine awareness among premedical students through a summer premedical rural enrichment program

- The effect of postgraduate osteopathic manipulative treatment training on practice: a survey of osteopathic residents

- Musculoskeletal Medicine and Pain

- Original Article

- Optimizing chronic pain management through patient engagement with quality of life measures: a randomized controlled trial

- Pediatrics

- Original Article

- Asthma medications in schools: a cross-sectional analysis of the Asthma Call-back Survey 2017-2018

- Public Health and Primary Care

- Review Article

- Thoracic outlet syndrome: a review for the primary care provider

- Clinical Image

- Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome

- Letter to the Editor

- Comments on “Mini-medical school programs decrease perceived barriers of pursuing medical careers among underrepresented minority high school students”