Abstract

This article addresses social stratification during the Ur III period (ca. 2100–2000 BCE), particularly in southern Babylonia. The social strata are analyzed as Weberian orders (Stände), also known as status groups. More specifically, this article focuses on un -il 2 as a serflike order in comparison to free citizens and enslaved people. While un -il 2 can be translated as “menial(s),” which is preferrable to how they are sometimes translated as “carrier(s),” the term may literally mean “people supporter(s).” un -il 2 were distinguished socially and economically from citizens and slaves, while sharing features with both. Like citizens, they were legally free, worked and probably lived with their families, and were compensated better than slaves and sometimes certain citizens. Like slaves, they were subjected to full-time mandatory work with often low compensation. Overall, they had less economic autonomy and stability than citizens but more so than slaves. As such, they can be considered serflike but not fully enslaved and are therefore a compelling example of people with statuses between citizens and slaves, economically and legally. While this article examines a variety of features regarding un -il 2 , their economic conditions are the most understood. Extensive details concerning subsistence and tenant lands are provided, especially their sizes and yields for citizens and un -il 2 . Unsurprisingly, citizens were allotted more subsistence land on average than un -il 2 were allotted. The plots citizens were allotted also tended to have better yields. Surprisingly, there is one known example of a wealthier un -il 2 renting tenant land, which was otherwise rented by mostly citizens. Based on these data, it is evident that citizens could generally sustain themselves and accumulate wealth, whereas most un -il 2 were impoverished, though not as much as slaves.

1 Introduction

The Ur III society[1] (ca. 2100–2000 BCE), especially in southern Babylonia, consisted of mainly three social strata: free citizens, serflike un -il 2 , and enslaved people.[2] People belonging to these strata were distinguished according to their shared rights and privileges or lack thereof. Based on these distinctions, these strata can be described as Weberian orders (Stände). Citizens were legally free and generally experienced economic autonomy and stability, whereas slaves were legally unfree and therefore deprived of economic autonomy and stability. Economic autonomy is understood here as the ability to make voluntary economic choices, especially with regard to work but also in terms of managing property or possessions. Economic stability is considered here as having enough resources to sustain oneself or one’s family and acquire wealth over time. un -il 2 , meaning “menial(s)” or perhaps literally “people supporter(s),” shared features with both citizens and slaves without being either. Like citizens, they were legally free, worked and probably lived with their families, and they could be compensated better than slaves and sometimes certain citizens. Like slaves, they were subjected to full-time mandatory work with often low compensation. As such, they can be considered serflike but not fully enslaved and are therefore a compelling example of people with statuses between citizens and slaves, economically and legally.

It is important to recognize the debate about distinguishing between serflike and enslaved people in the ancient Near East, which is addressed well by Laura Culbertson (2024: 243):

In any historical context, “slavery” can refer to a legal status, various types of coerced labor, or a broad metaphor for subjugation and exploitation; slavery can be an institutionalized phenomenon or a relative situation (see Engerman 2000: 480). … For example, one could consider slavery a single, unique category of servility, if a “porous” one (after Tenney 2017: 719). On the other hand, scholars could view all forms of forced and obligatory labor as variegated forms of slavery. In other words, slavery is either a narrow part of a range of servile categories, or an inclusive term for many. The answer is consequential. The former picture means slavery is a fairly negligible aspect of societies and suggests we employ a broader range of translations (“serf,” “servant,” etc.); the latter means slavery was endemic and widespread.

My approach is the former, which views slaves as legally owned in contrast to serflike un -il 2 , who were not legally owned as property though they were subjected to full-time and often poorly compensated mandatory work.[3] While it cannot be pursued further here, un -il 2 were similar to širkū and širkātu from mainly the Neo-Babylonian period, who were donated to temples and regarding whom Kristin Kleber (2011: 101) writes:

Širkus are often characterized as temple slaves, and it is generally held that their fate was better than that of other kinds of slaves because the temple gods, as owners, did not directly exercise rights of ownership. I argue that širkus were not slaves, in fact, but are better understood as institutional dependents whose limited freedom, in comparison with free citizens of a Babylonian town, was a result of their social subordination to an institutional temple household. …

In fact, these persons were never designated as temple “property” (makkūru), but were subordinate members of the temple households owing labor and services to the temple.

The fact that un -il 2 could be donated to temples makes this comparison particularly relevant. Bartash (in this issue) likewise argues that individuals donated to temples in third-millennium Babylonia were not slaves but rather “servants” of the deities.

In order to clarify the serflike qualities of the un -il 2 , I further articulate the nature of these Weberian orders and then compare distinctions between the orders, including their terminology, origins, family lives, housing, legal rights, and economic conditions. Due to the nature of the evidence, the distinctions between citizens, un -il 2 , and slaves are mostly apparent based on their economic conditions. This section addresses their occupations and employment arrangements, which involves estimating their incomes in order to approximate their sustenance based on barley. Overall, this study focuses on textual data from Umma, which is representative of southern Babylonia to some extent but not exhaustively.

2 Weberian Orders during the Ur III Period: Citizens, un-il 2 , and Slaves

There are many ways that social stratification can be understood, and a Weberian approach works well for distinguishing between citizens, un -il 2 , and slaves during the Ur III period. Specifically, these distinct groups can be classified as Stände, which Max Weber (1978, II: 932 [originally published in 1921–1922]) defines as follows:

In contrast to classes, Stände (status groups) are normally groups. They are, however, often of an amorphous kind. In contrast to the purely economically determined “class situation,” we wish to designate as status situation every typical component of the life of men that is determined by a specific, positive or negative, social estimation of honor. This honor may be connected with any quality shared by a plurality, and, of course, it can be knit to a class situation: class distinctions are linked in the most varied ways with status distinctions. Property as such is not always recognized as a status qualification, but in the long run it is, and with extraordinary regularity. … But status honor need not necessarily be linked with a class situation. On the contrary, it normally stands in sharp opposition to the pretensions of sheer property.

Identifying Stände is challenging for several reasons, however, including debates about the meaning of honor and related terminology as well as the kinds of groups that can share statuses, such as castes and occupational groups, among others (Omodei 1982). Rather than basing Stände directly on shared honor, R. A. Omodei (1982: 199–200) provides a nuanced definition that is utilized here:

A status group can be defined as a group of people, who within a political community, may be distinguished by a shared level of access to valued rights and privileges, that is, they are a group of people who share similar status situations. Status situation refers to the configuration of rights and privileges, the positive or negative benefits of which are effectively claimed. The claim is ‘effective’ as long as it is socially legitimate, that is, secured or enforced by law or by custom, by the operation of structural or ideological factors.

There is a logical connection between status, so defined, and prestige. Members of a status group may come to share the same social estimation of ‘honour’ – to the extent that this is determined by status situation – and the same access to, or exclusion from restricted goods and services. This shared prestige or honour is derivative, not primary.

According to this definition, which builds on Weber’s, Ur III citizens, un -il 2 , and slaves can be described as Stände because the individuals belonging to each of these Stände shared claims to rights and privileges or the lack thereof, which were all maintained by laws or customs.

The translation of Weberian Stände is likewise complicated and disputed, however. Thomas Burger (1985: 37 n. 5), for example, discusses its translation accordingly:

Weber’s term ‘Stand’ (estate) has usually been translated as ‘status group’. This translation is defensible although there are no really strong reasons for preferring it to ‘estate’. If the common meaning of the latter is considered too misleading or restrictive to cover adequately the range of phenomena to which Weber refers (Bendix, 1960:85; Dahrendorf, 1959:6–7), then the most appropriate English equivalent would appear to be the old-fashioned term ‘order’, as in the expression ‘people of all orders and descriptions’.

Given these terminological challenges, the term “orders” is the best option for this treatment, and it is a term suggested as an alternative to “social classes” by Hervé Reculeau (2013: 998) for the awīlû, muškēnū, and wardū in the Laws of Hammurabi.

3 Distinctions between the Citizen, un-il2, and Slave Orders

3.1 Overview

The distinctions between citizens, un -il 2 , and slaves can be summarized according to essential features presented in Table 1.

Features of the citizen, un -il 2 , and slave orders during the Ur III period.

| Feature | Order | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citizen | un-il2 | Slave | ||

| Native terminologya | Male | dumu dab 5 -ba (“conscripted son”), (dumu/guruš) eren 2 (“[child / working adult male] troop member”), dumu GN/uru( ki ) (“son of GN / the city”), (guruš) dumu-gir 15 (“[working adult male] citizen”), (guruš) eren 2 gal(-gal) (“[working adult male] mature troop members”), (guruš) eren 2 tur(-tur) (“[working adult male] young troop members”) | (dumu/guruš) un -il 2 (“[child / working adult male] menial”), (guruš) un -il 2 gal-gal (“[working adult male] mature menials”), un guruš/PN (“menial working man / PN”), un -il 2 nita (“male menial”), un -il 2 tur(-tur) (“young menials”) | (guruš) arad 2 (“[working adult male] slave”), sag-rig 7 (“gifted one”)b |

| Female | dam eren 2 (“wife of a troop member”), (geme 2 /munus) dumu-gir 15 (“[working adult female / female] citizen”) | geme 2 ( un -il 2 ) (“working adult female [menial]”), un -il 2 (munus) (“[female] menial”) | geme 2 (sag-rig 7 ) (“[gifted] slave woman”), sag-rig 7 (“gifted one”) | |

| Origins | Birth (typically from a citizen mother), native population, former prisoners of war | Birth (typically from an un -il 2 mother), donation (?), impoverishment (?), punishment (?) | Birth (typically from an enslaved mother), debt slaves from impoverished citizens, chattel slaves from criminals, former prisoners of war, and interregional slave markets | |

| Family lives | Nuclear and extended families | Nuclear and extended families | Limited familial connections | |

| Housing | Privately owned or perhaps rented | Uncertain (perhaps housed by donors and supervisors or privately owned/rented) | Housed by owners | |

| Legal rights | General | Fullest extent | Probably limited | Least extent |

| Salability | Salable as debt slaves (resale abroad could be restricted) | Unsalable (?) | Salable as chattel slaves | |

| Manumission | Possible (more frequent than chattel slaves) | N/A (?) | Possible (less frequent than debt slaves) | |

| Economic conditions | Occupations | Any possible occupation | Most occupations except for most cultic and high-ranking administrative and managerial occupations | Resource extraction, construction and manufacturing as well as services, including domestic work |

| Typical Employment Arrangements | Part-time conscription (male individuals only), hiring, self-employment | Full-time conscription, minimal self-employment | Full-time slave labor (could be similar to conscription) | |

| Sustenance | Allotments of barley, wool, etc., subsistence and tenant lands, profits, wages | Allotments of barley, wool, etc., subsistence and minimal tenant lands | Allotments of barley, wool, etc. | |

-

aThe translations for these terms are mostly literal and given in the singular unless they are only used as plurals. Note that “son” in dumu dab5-ba and dumu GN/uru(ki) is figurative and indicates that they were citizen members. The use of “son” here is the same as in dumu-gir15 (literally “native child/son”). For how “son” indicates citizen membership, see Bartash and Pottorf in this issue. guruš and geme2 literally mean “working man” and “working woman,” respectively, though geme2 also usually indicates subordination as a servant or slave. These meanings are usually conveyed literally in these translations but not when geme2 means “slave woman.” For more on guruš and geme2 , see 3.2 Terminology. bThis term is discussed by Bartash (in this issue).

3.2 Terminology

The reading and meaning of un -il 2 are uncertain and not addressed fully here. The term is usually translated as “carrier(s)” and “menial(s),” but it may literally mean “people supporter(s)” or “those who support the people.” il 2 alone should be translated as “carrier(s),” however, and un -il 2 performed a wide range of tasks besides carrying.[4] “Menial(s),” which is based on its Akkadian equivalent, kinattu(m), works and is used here.[5] The suggested literal meaning, “people supporter(s)” or “those who support the people,” is based on reading this term as a dub-sar formation, meaning that un (“land” [read as kalam] or “people” [read as un]) would be the object of the verb il 2 (literally “carry” or figuratively “support”), so that it is analogous to ab-(ba-)il 2 (“father supporter(s)”) and ama-il 2 (“mother supporter(s)”).[6] Since these individuals were temporarily exempted from conscription to support their elderly and likely ailing parents (Steinkeller 2018), perhaps un -il 2 were permanently conscripted to support the people or land more generally – given the personal nature of ab-(ba-)il 2 and ama-il 2 , supporting the people is preferred to the land here. It may be pertinent that all three of these terms are abbreviated the same way: ab PN for an ab-(ba-)il 2 PN, ama PN for an ama-il 2 PN, and un PN for an un -il 2 PN.[7] This interpretation also has the same meaning as an epithet of Ninlil with the same signs, concerning which W. G. Lambert and Ryan Winters (2023: 98) write: “The ordinary meaning of UN-il2 in older texts (il2 could also be read ga6) is ‘worker,’ but it could also be here interpreted as an epithet ‘the one who carries the people/the land.’” However, this much-later epithet for Ninlil may not have had any similarity to un -il 2 as a social term. Given the uncertainty about this term, however, this is admittedly speculative, but it is striking in any case that d un -il 2 is an epithet for Ninlil.

Male un -il 2 considered to be adults (probably at least thirteen years old) can be referred to as guruš un -il 2 , rarely (guruš) un -il 2 gal-gal, un guruš, un PN, or un -il 2 . un -il 2 boys can be identified as un -il 2 tur(-tur) in contrast to (guruš) un -il 2 gal-gal and perhaps once as dumu un -il 2 . Male un -il 2 are called un -il 2 nita once in contrast to female un -il 2 called un -il 2 munus, which indicates that un -il 2 could also be gender neutral. Nevertheless, un -il 2 is overwhelmingly used for male individuals. Female un -il 2 considered to be adults (also probably at least thirteen years old) are occasionally described as geme 2 un -il 2 .[8] They are rarely referred to as simply un -il 2 . In the Girsu text MVN 6: 308 obv. ii 3, 7, 9, 11, and 14, a few women are conscripted to be un -il 2 of various locations.[9] In the Puzriš-Dagān text Ontario 2: 190 obv. 6–10 and 12, a woman is conscripted with her father and brothers, and they are all seemingly called un -il 2 . This may be focusing on the male un -il 2 , and they are also categorized as guruš un -il 2 and geme 2 (obv. 17–18).[10] Otherwise, un -il 2 women are labeled as geme 2 , and the un -il 2 order of their children is not usually specified. Unfortunately, given the use of geme 2 for female slaves, it may be impossible to differentiate many female un -il 2 and slaves unless they had explicitly un -il 2 sons.[11]

It should be pointed out that terms guruš and geme 2 have been debated with regard to whether they refer to serflike or enslaved people (Culbertson 2024: 244). In Ur III texts, guruš is used for one or more men performing mandatory or sometimes hired work (Table 3) without specifying their orders. If it was important for administrative reasons to specify their orders, citizens can be guruš dumu-gir 15 or guruš eren 2 , un -il 2 can be guruš un -il 2 or un guruš, and slaves can be guruš arad 2 .[12] geme 2 is likewise utilized for one or more women performing mandatory or rarely hired work, and they were mostly un -il 2 and slaves since citizen women were usually self-employed in domestic work.[13] However, in the Girsu text HLC 3: 374 pl. 141, citizen women subjected to penal labor are called dam eren 2 (rev. i 18), dumu-gir 15 (obv. ii 20), and geme2 dumu-gir 15 (rev. ii 3), but they are also summarized as geme 2 (rev. ii 6) along with geme 2 a-ru-a (rev. ii 5) and geme2 lu2 (rev. ii 4). The geme 2 a-ru-a (“donated working woman” in the singular) were mostly or only un-il 2 (3.3 Origins), and the geme 2 lu 2 (literally “working woman of a person” or contextually “slave woman of a person” in the singular) were personal slaves.[14]

3.3 Origins

Individuals belonging to all three orders could inherit their orders at birth from their mothers (Pottorf 2022: 112–14), but the other reasons why individuals became un -il 2 are less certain. The most likely origin is that they were impoverished families of the native population, perhaps for several preceding generations. They may have developed as an order from carriers and related individuals who were likewise serflike during the Early Dynastic period, and they are first clearly attested during the Sargonic period.[15] Many donated (a-ri-a / a-ru[-a]) individuals were un -il 2 , but it is unclear whether this was causal or not.[16] Otherwise, there is some possible evidence that citizens could become un -il 2 as a punishment (Pottorf 2022: 116–20). For example, ASJ 9, p. 315 4 may document a citizen named Lu-Šara who was penalized with work as an un -il 2 because another un -il 2 named Šaraisa fled from his custody.[17] If this is true, it is not clear how long this punishment lasted.[18]

3.4 Family Lives

While there are some uncertainties about un -il 2 families, male and female un -il 2 worked or were at least registered with their nuclear and extended families of the same gender, though sons sometimes worked or were registered with their mothers (and possible sisters). Unfortunately, it is not always clear whether sons who worked or were registered with their mothers were un -il 2 or slaves because of the ambiguity of the term geme 2 . Some sons may have been registered with their mothers because they were very young. However, young sons were mostly registered with their fathers because it was expected that they would work with their male relatives when they were old enough. Other sons may have worked or been registered with their mothers perhaps because their fathers were deceased or otherwise disconnected from their families (maybe as fugitives). This is especially the case if the sons were considered adults, which is rare.[19] Even if un -il 2 men did not have fathers, most of them worked with male citizens and un -il 2 because of the kind of work they were conscripted to perform. Some male un -il 2 were identified with matronymics rather than patronymics for possibly similar reasons, which was more common for them than for citizens. There is also rare evidence that daughters could work or be registered with their fathers, again for maybe similar reasons.[20] Based on the sizes of families of male un -il 2 only, their entire immediate families appear to have averaged between four and six individuals, which is about the same for citizens. It is difficult, however, to find evidence that male and female un -il 2 lived together as families, but it is assumed that they did. One kind of indirect evidence is that mostly male un -il 2 , like male citizens, could be temporarily exempted from conscription to support their elderly and perhaps ailing fathers and mothers. This was an important exemption from conscription that was probably not available to slaves, and it is demonstrative of how citizens and un -il 2 could maintain families in a way that slaves could not (Pottorf 2022: 122–36, 196).[21]

3.5 Housing

There is no clear evidence of how un -il 2 were housed. It is possible that they were housed by their donors if they were donated (Bartash in this issue). Some Early Dynastic and Sargonic texts indicate that individuals conscripted full time could live with or near their supervisors or where they worked. Interestingly, Debate between Winter and Summer 209 mentions the building of houses for un -il 2 , but this is not very helpful because it may not be relevant and does not indicate who owned these houses. Whether they could own or rent private housing or were housed by those upon whom they were dependent, their typical housing was probably smaller and overall worse than the typical housing for citizens (Pottorf 2022: 148–50). This is because most un -il 2 were impoverished (Table 6), but a few un -il 2 had incomes large enough to probably afford housing similar to or even better than what citizens generally owned (Graph 1).

3.6 Legal Rights

The legal rights of un -il 2 are likewise uncertain. They are not mentioned in the Laws of Ur-Namma, and they are not explicitly identified in legal texts. Their absence in the Laws of Ur-Namma could be because they were understood to be legally free, but these laws were neither comprehensive nor a completely accurate codification of laws during the Ur III period.[22] They may have had more rights than slaves but perhaps less than citizens. In comparison to slaves, they could have had substantially more possessions, at least in terms of barley. Their full-time conscription meant that they lacked mobility like slaves. There is no clear evidence that they were salable, but further prosopographical analyses could indicate otherwise (Pottorf 2022: 157).[23] Bartash (in this issue) draws attention to the fact that donated individuals could not be sold, which was perhaps the case for un-il2 , especially if they were donated.

3.7 Economic Conditions

3.7.1 Occupations

While occupations were largely dependent on gender and parentage, orders also impacted individuals’ occupations. Citizens could have any possible occupation, but slaves were limited to mostly arduous occupations involved in resource extraction, such as cultivation, construction and manufacturing, such as cereal grinding and weaving, as well as services, such as boat towing. Slaves in private households also performed a range of domestic tasks. un -il 2 , however, could have many of the same occupations as citizens, but they were not known to have had many cultic and high-ranking administrative and managerial occupations (Pottorf 2022: 162–73). The percentages of conscripted citizen and un -il 2 men according to these occupational categories, as attested in Umma inspections and related texts are given in Table 2.[24]

Percentages of conscripted citizen and un -il 2 men according to occupational categories in Umma inspections and related texts.

| Occupational category | Order | |

|---|---|---|

| Citizen | un-il2 | |

| Resource extraction | ∼60.89 % | ∼59.01 % |

| Construction and manufacturing | ∼17.45 % | ∼27.74 % |

| Services | ∼8.9 % | ∼9.52 % |

| Administration and management | ∼12.76 % | ∼3.73 % |

Adults counted here were probably between the ages of thirteen and fifty or so, and they were notated as full time ( aš c ) or half time (½ c ).[25] Overall, it is clear that most un -il 2 were engaged in resource extraction, which was often the least compensated, whereas they were rarely conscripted for administrative and managerial occupations, which were usually the most compensated (Pottorf 2022: 229–31). Whether they were citizens or un -il 2 , individuals involved in construction and manufacturing as well as services experienced a wide range of compensations depending on their specific occupations. For example, in terms of construction and manufacturing, potters were compensated with ∼3.73 times less subsistence land on average than brewers, and, with regard to services, snake charmers were compensated with ∼6.55 times less subsistence land on average than physicians (Pottorf 2022: 230).

3.7.2 Employment Arrangements

3.7.2.1 Overview

There are five kinds of employment arrangements detailed in Table 3, including conscription, penal labor, and slave labor, which are mandatory, as well as hiring and self-employment, which are voluntary.[26] Employers were usually institutional, specifically provincial and temple, households and large, especially royal, private households with personnel, which are called administrative households for simplicity’s sake, or smaller private households, which may have included one or more slaves. The details of these employment arrangements are particularly dependent on Umma texts.

Employment arrangements in Ur III Umma.

| Requirement | Employment arrangement | Employer | Workers | Scheduling | Compensation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mandatory | Conscription | Administrative households | Usually male citizens | Regularly part time, temporary exemption for parental support | Minimum or above-minimum allotments, depending on occupation |

| un -il 2 | Regularly full time, temporary exemption for parental support | ||||

| Penal labor | Administrative households | Any individual | As desired (?) or regularly full time | Usually minimum allotments | |

| Slave labor | Administrative households | Usually female slaves and sometimes their enslaved male children | Regularly full time | Usually minimum allotments | |

| Private households | Slaves | As desired or regularly full time (?) | Probably minimum allotments | ||

| Voluntary | Hiring | Probably only citizen households (administrative and private) and individuals | Probably only citizens (mostly male) | As desired | Wages better than conscription allotments but often nonnegotiable |

| Self-employment | Workers employ themselves | Probably only citizens (others in minimal amounts) | As desired | Variable profits or uncompensated benefits |

3.7.2.2 Mandatory Work: Conscription, Penal Labor, and Slave Labor

Most male citizens with the exception of individuals with certain cultic and high-ranking administrative and managerial occupations were conscripted along with all un -il 2 .[27] When citizens were conscripted, they typically received fifteen days off every month, unless they were conscripted for cultivation when they only had these days off for three to four months a year.[28] It is possible that some of their workdays were actually festival days, which they may have had regularly throughout the year.[29] Overall, they were conscripted part time and therefore experienced significantly more economic autonomy than un -il 2 and especially slaves. un -il 2 were conscripted full time – female un -il 2 usually received five to six days off each month, if not more in rare circumstances, whereas male un -il 2 received three days off each month, but only during the same months that citizens received fifteen days off. Like citizens, some of their workdays may have been festival days. It is important to note that while male citizens and un -il 2 had fewer days off when conscripted for cultivation, they could be assigned different work from year to year, which would have limited their most-demanding work. As mentioned before, usually male citizens and un -il 2 could be temporarily exempted from conscription to support their parents, which was probably not a possibility for those subjected to penal labor or slave labor (Pottorf 2022: 201–16).

Any individual could be subjected to minimally compensated penal labor for a variety of reasons. For example, though female citizens were not usually conscripted, they could be subjected to penal labor when their male relatives did not fulfill their obligated conscription (n. 14). These citizens would have been deprived of their economic autonomy and stability, at least temporarily. The details of slave labor in private households are not well attested, but female slaves and their children in administrative households were subjected to slave labor alongside conscripted female un -il 2 . In these cases, they also received the same number of days off (Pottorf 2022: 208–10, 248–51).

When individuals were compensated with allotments by administrative households for mandatory work, they could have been allotted barley monthly and wool or garments annually, in addition to other commodities. Otherwise, they were allotted shares of subsistence land ([gan 2 ] šuku) that yielded barley annually, in addition to other commodities. The typical monthly allotments of barley (in sila 3 [∼1 L]) for male and female individuals according to their age brackets in Umma are provided in Table 4.[30] While these allotments were typical, there were other amounts as well, and individuals subjected to penal labor could be allotted less than usual.

Typical monthly allotments of barley for male and female individuals performing mandatory work in administrative households according to their age brackets in Umma.

| Approximate age bracket | Monthly allotment of barley (in sila3) according to gender | |

|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | |

| 0 to 6 | 10/15/20 | 10/15 |

| 6 to 13 | 20/30/40 | 20/25 |

| 13 to 50 | 60/75 | 30/40 |

| 50+ | 40/50 | 20 |

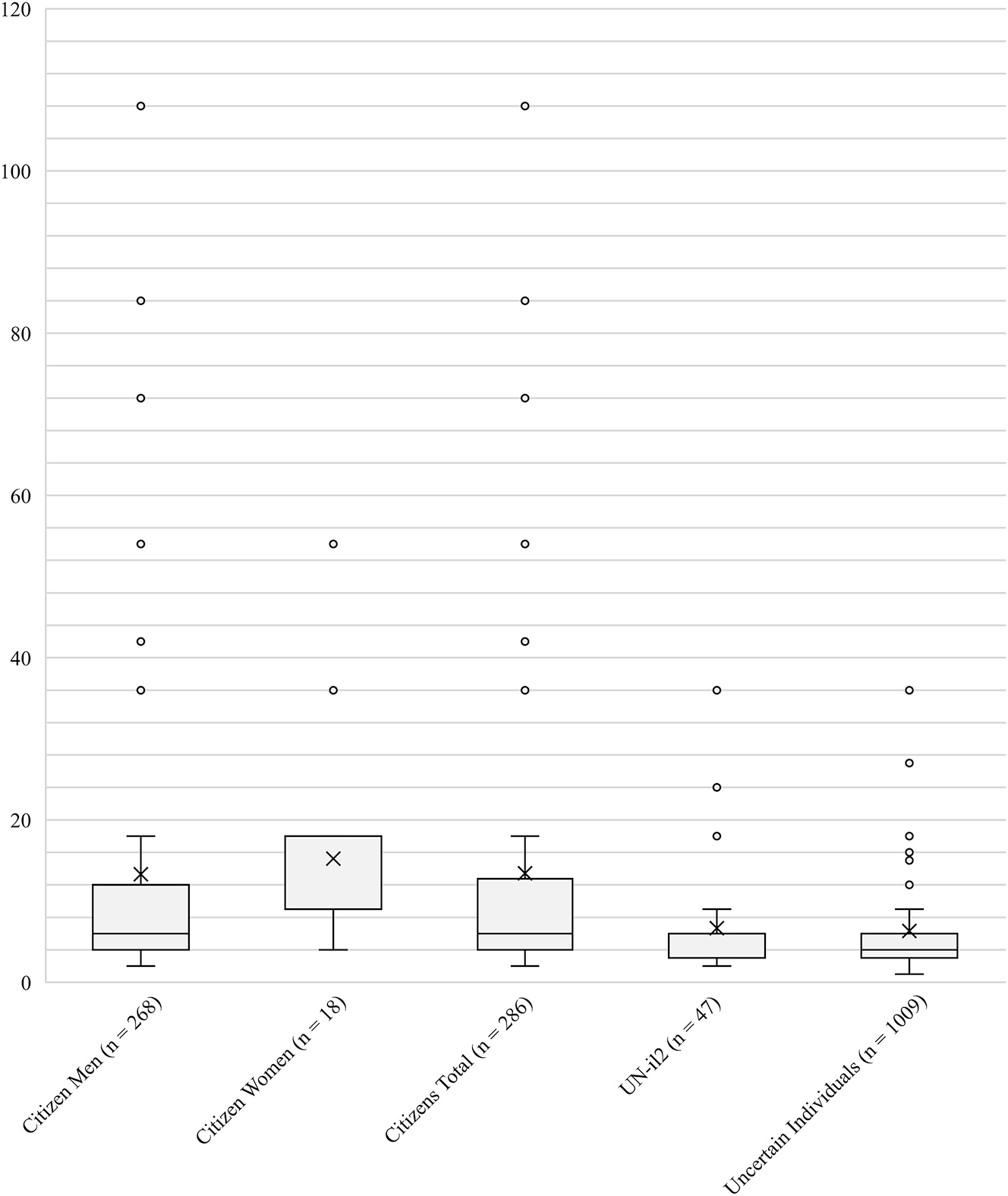

The vast majority of citizen men were allotted shares of subsistence land that sustained themselves and their families, and the rest were allotted barley monthly. Some citizen women who held cultic occupations or were in high-ranking families were also allotted subsistence land.[31] Interestingly, the Nippur text AuOr 40, p. 259 10 details an ereš-dingir priestess who rented her subsistence land as tenant land. Only about half of un -il 2 men were also allotted subsistence land for themselves and their families, whereas the rest of the un -il 2 and all slaves were allotted barley monthly (Pottorf 2022: 180–83, 219–27). The subsistence-land sizes (in iku [∼0.35 ha]) for most citizens (excluding exceptional individuals like the governor) and un -il 2 in Umma are visualized in Graph 1.[32]

Subsistence-land sizes (in iku) for most citizens and un -il 2 in Umma.

Although these data are reliable to some extent, the vast majority of sizes were for individuals with unknown orders. The middle 50 percent of citizen men and un -il 2 were allotted 4 to 12 iku and 3 to 6 iku, respectively. It is probably the case that many of the uncertain individuals allotted 3 iku were un -il 2 and those allotted 6 iku were citizens. While it is difficult to precisely account for this, it can be roughly estimated that the middle 50 percent of citizen men and un -il 2 were allotted 6 to 12 iku and 3 to 4 iku, respectively. As these data indicate unsurprisingly, un -il 2 were allotted significantly less than citizens, though it is remarkable that they could be allotted as much as 36 iku. The few un -il 2 with larger subsistence-land sizes would have had more economic autonomy than most un -il 2 , at least in terms of managing their possessions. Although un -il 2 were allotted about twice as less on average than citizens, this was probably because they tended to have low-compensation occupations rather than because they were un -il 2 .

Besides determining the sizes of subsistence-land shares that citizens and un -il 2 were usually allotted, it is important to consider their yields (in sila 3 /iku). At Ur III Girsu-Lagaš, the average yield for subsistence land was under ∼333 sila 3 /iku (Maekawa 1986: 116). Noemi Borrelli (2013: 27) states the following about this yield average in comparison to the higher yield average for domain land:

The cultivation of sustenance plot[s] was conducted with the equipment granted by the institutions, which provided the plowing team and the seeds. The productivity level of the šuku plots of the household of Namhani was lower than the one retrieved for the domain land and it seems to be usually lower than 20 gur per bur3 [∼333 sila 3 /iku]. Whether or not there was an implicit practice of assigning land with low productivity level to temple personnel is still under debate.

Though there may have been several reasons for this difference in yield averages, perhaps a significant reason is that the subsistence-land yields were probably artificial if they were calculated after factoring in cultivation costs, such as animal fodder, equipment, and seeds, among others. This means that they would not have been the actual yields of the fields but administratively reduced yields. It may have also been the case that these artificial yields were altered based on individuals’ orders, occupations, or other circumstances. For simplicity’s sake, these possibly artificial yields are hereafter referred to as simply yields. Otherwise, it would also make sense to assign more-productive land to be domain land so that some of its yield could be used to cover the cultivation costs of subsistence land. Either way, it is assumed here that the recipients of subsistence land were allotted the entirety of their reported yields without any deducted costs.

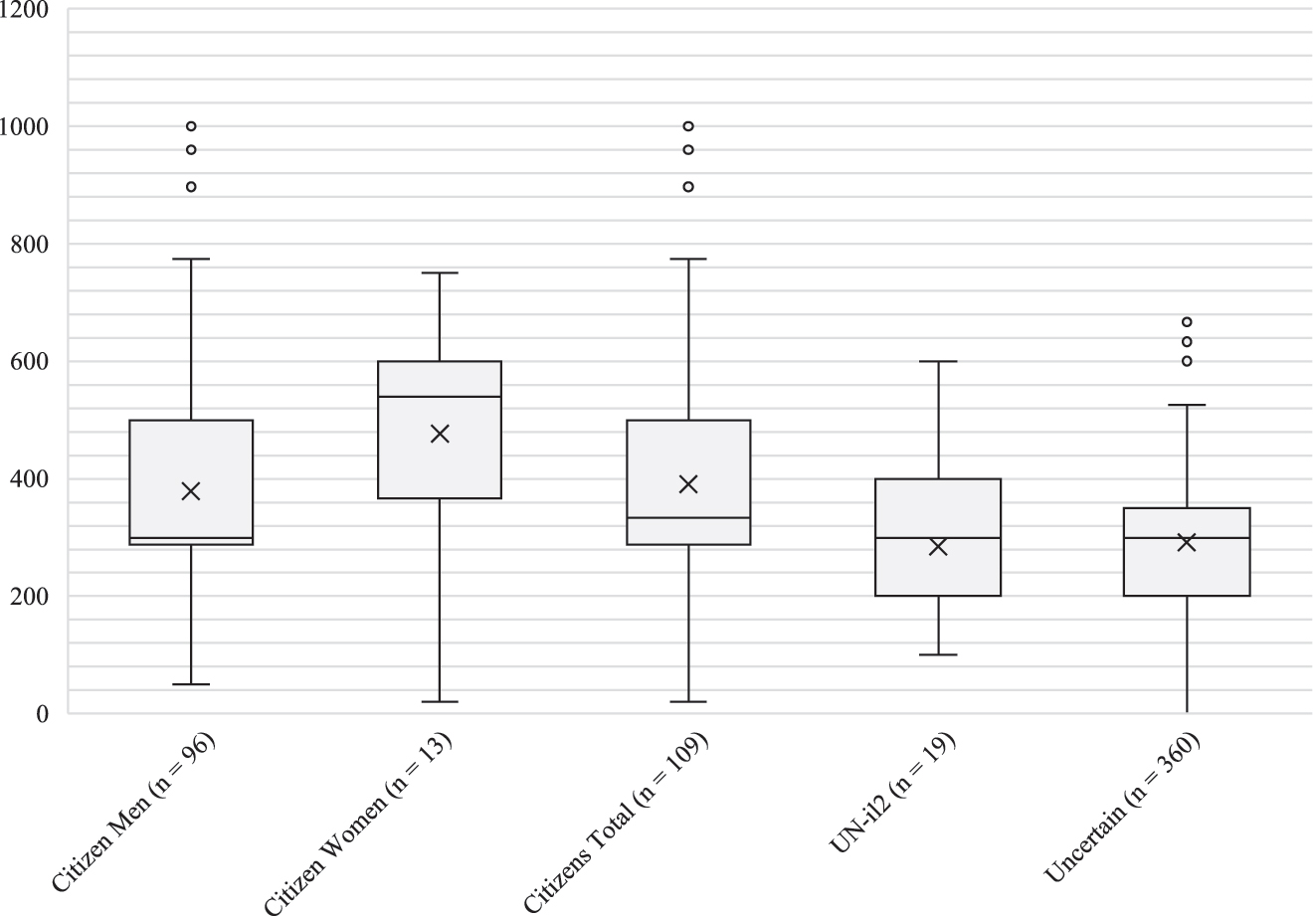

As for citizens and un -il 2 in Umma with known subsistence-land sizes, it is possible to compare their yields, as seen in Graph 2.[33] While the data are unevenly spread, the median yields for everyone but citizen women are 300 sila 3 /iku or a little less, which fits well with the average yield of under ∼333 sila 3 /iku at Ur III Girsu-Lagaš. It is difficult to detect reliable trends based on these uneven data, but it seems that citizens generally had better yields than un -il 2 . The few citizen women with subsistence land apparently had higher yields on average, probably due to their privileged positions described above. It is possible that occupations played a significant role in whether yields were above or below the median. For example, the median yield for scribes or individuals with scribal training (Steinkeller 2017b: 53–54) was 500 sila 3 /iku, and the highest yield was ∼774 sila 3 /iku.[34] They and other individuals with administrative and managerial occupations probably tended to have the highest yields overall. If the middle 50 percent of citizen and un -il 2 men had conservative yields of 300 to 450 sila 3 /iku and 200 to 350 sila 3 /iku, respectively, then these citizen men could have received 1,800 to 5,400 sila 3 of barley annually, whereas these un -il 2 men could have received 600 to 1,400 sila 3 of barley annually.

Subsistence-land yields (in sila 3 /iku) for most citizens and un -il 2 in Umma.

3.7.2.3 Voluntary Work: Hiring and Self-Employment

Citizens, especially male individuals, were able to hire themselves out when they were not conscripted, but perhaps un -il 2 and especially slaves could not do so. When citizen men were hired, they were usually paid daily wages of 6 sila 3 in barley, though they could probably have been paid more when demand was higher for harvests or if they were hired for highly skilled work, such as craftworking (Pottorf 2022: 251–56). If they were paid 6 sila 3 daily, it was three times the daily amount of the monthly allotment of 60 sila 3 many men received while conscripted. Although it is difficult to know how often citizen men would have hired themselves out a year, it could have been between 30 and 120 days a year. This estimate assumes that they could have hired themselves out half a thirty-day month minus five days for festival days and days off for as few as three months or as much as a whole twelve-month year.[35] If so, they could have been paid between about 200 and 750 sila 3 annually, which are both rounded up to account for possibly higher wages in some cases. It is not certain how many male citizens per family hired themselves out and what wages younger individuals may have earned, so this is probably a conservative estimate. It is possible that female citizens could hire themselves out, but this needs further study.

Self-employment is significantly less attested than the other employment arrangements, given the nature of the evidence, though it was ubiquitous. Female citizens were usually self-employed when they engaged in crucial domestic work, including childcare, cooking, and textile work, among other duties. Although it was not often profitable, it did result in uncompensated benefits. While individuals from other orders could engage in domestic work for themselves, they would have been far more restricted by their limited time and resources. Female un -il 2 and slaves could have used some of their days off for domestic work, especially since they had more days off than male un -il 2 . Female citizens could also be self-employed in various occupations, such as midwives, physicians, priestesses, sex workers, and tavern keepers, among others (Steinkeller 2022).[36] Male citizens could be self-employed as merchants, for example. The profits from any of these occupations are difficult to ascertain, however.

Perhaps the best-attested form of self-employment was renting tenant land ([gan 2 ] apin-la 2 ), which required tenants to invest their own resources in order to gain profits that generally amounted to about maybe a third or nearly half their tenant-land yields. Tenant land producing various kinds of crops or for pasturage could be rented, but barley was the most significant and assumed in this discussion.[37] Most individuals who rented tenant land were citizen men, but some citizen women could rent tenant land. There is also one possible instance of an un -il 2 renting tenant land. In Orient 21, p. 2 obv. iv 19′–20′ and rev. iv 10–11, there is an animal fattener named Bida who rented 1 iku of tenant land yielding 200 sila 3 /iku before deducting cultivation costs, rent, and taxes and who was allotted 9 iku of subsistence land yielding 200 sila 3 /iku. Due to the text's damage, it is possible that he rented more tenant land. This Bida appears to have been an un -il 2 based on OrSP 47–49: 483 and probably CUSAS 39: 129. While this singular instance of a possible un -il 2 renting tenant land indicates that other un -il 2 may have been able to rent tenant land, this individual was allotted more subsistence land than most un -il 2 , and he rented a small amount of tenant land with a below-average yield according to the extant text.

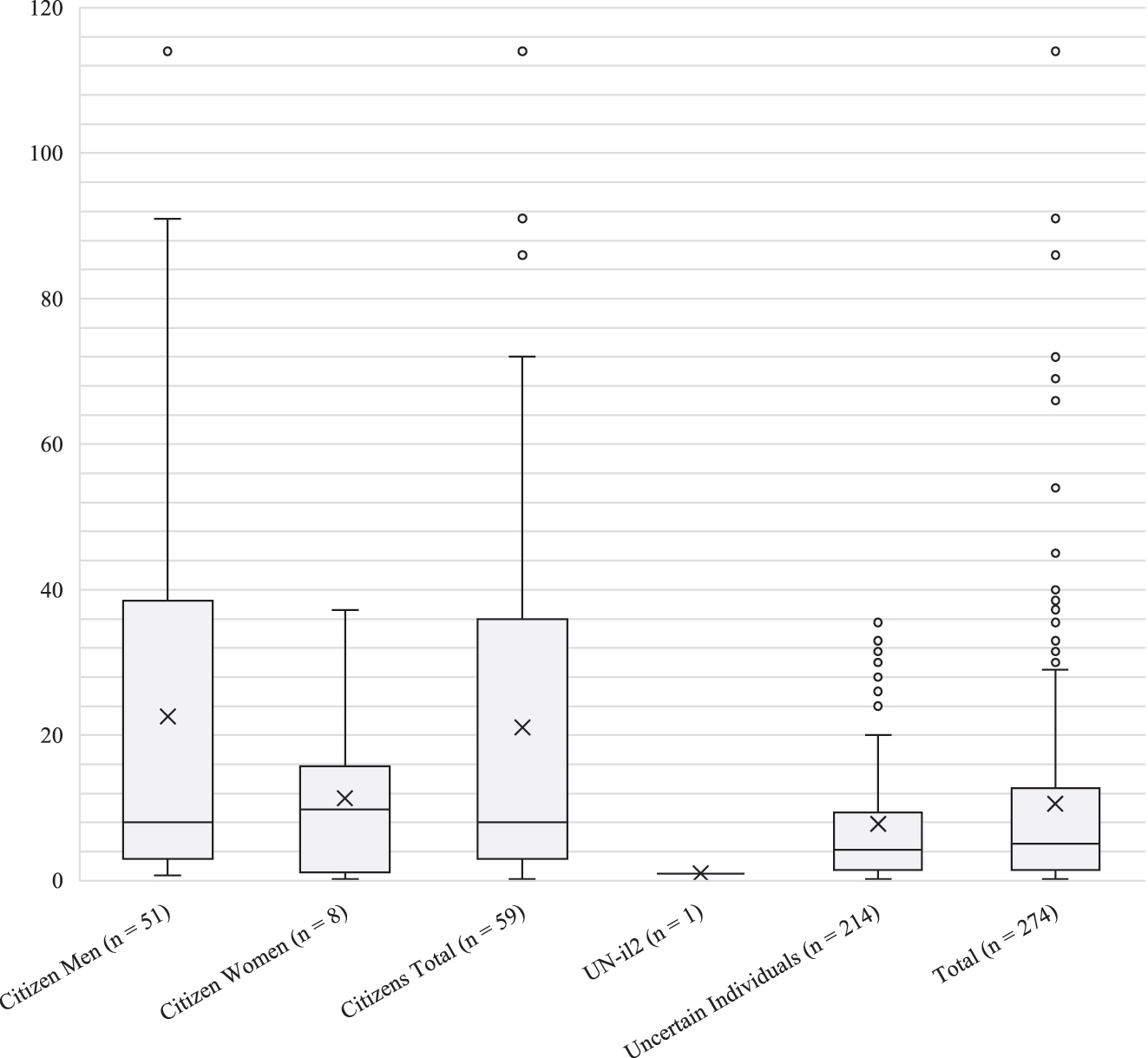

Although it is difficult to know the full sizes of tenant-land plots because individuals could rent tenant land from multiple areas, their known minimum sizes with regard to barley land for citizens and un -il 2 are given in Graph 3.[38] Whereas the order of most tenants is not certain, they were overwhelmingly citizens. The minimum sizes of 0.25 iku were especially small and were likely pieces of larger rented amounts. While the middle 50 percent for the total amount is 1.5 to ∼13 iku, it can be rounded up to at least 2 to 14 iku since these amounts were based on known minimums. Unsurprisingly, individuals with occupations that were better compensated during conscription tended to rent more, but even individuals with low-compensation occupations could rent tenant land (Pottorf 2022: 262).

Minimum tenant-land sizes (in iku) of barley land for citizens and un -il 2 in Umma.

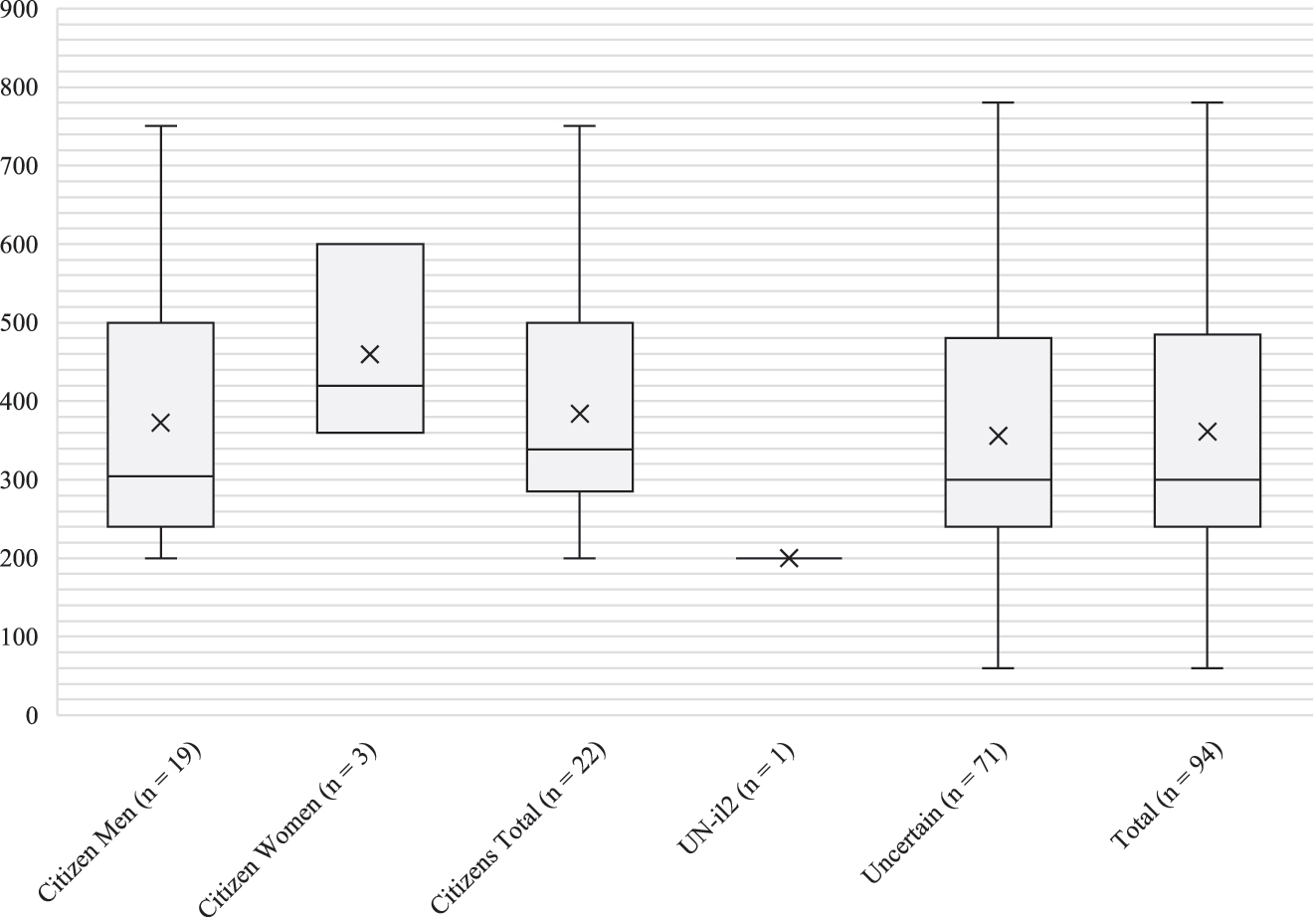

As for tenant-land yields, they are difficult to calculate given the variety of texts. A few texts detail tenant-land yields prior to the deduction of cultivation costs presumably as well as any rent paid in barley and irrigation tax paid in silver, which are given in Graph 4.[39] Though there are fewer data for these yields than for subsistence-land yields, tenant-land yields were typically larger. The middle 50 percent of the total yields ranges from 240 to 485 sila 3 /iku, whereas the middle 50 percent for all subsistence land is 200 to 400 sila 3 /iku. The average yield for citizen women is similarly larger than for all others, again perhaps due to their privileged positions. The yield for the one known un -il 2 is unsurprisingly low. While it is possible to speculate about the motives of landlords and tenants in improving tenant-land productivity, this requires further study to account for other factors, such as annual variances. More importantly, these yields did not factor in cultivation costs, but it is not known who cultivated tenant land and how its costs were paid. Although it is admittedly simplistic, perhaps tenant-land yields were virtually equal to or just a little higher than subsistence-land yields after deducting cultivation costs. For example, the cost of seeds and animal fodder may have been about 25 sila 3 /iku, which were not the only costs, of course.[40]

Tenant-land yields (in sila 3 /iku) of barley land for citizens and un -il 2 in Umma.

In addition to the few texts that document tenant-land yields before the deduction of the barley rent and silver tax, there are a few texts that record the barley rents of tenant land according to whether various plots had silver taxes or not. Most texts involving tenant land from Umma do not specify whether silver taxes were paid or not unfortunately, but the barley amounts appear to be rents. For the sake of brevity, the middle 50 percents of the barley-rent rates in all these texts are provided in Table 5.[41]

Middle 50 percents of barley-rent rates of tenant land for citizens and possibly others in Umma.

| Tenant-land type | Middle 50 percent of barley-rent rates (in sila3/iku) per order | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citizen | Uncertain | Total | |||

| Men | Women | Total | |||

| With silver tax | 150 (n = 2) | – | 150 (n = 2) | ∼151 to 240 (n = 11) | 150 to ∼239 (n = 13) |

| Without silver tax | – | – | – | 36.5 to 60 (n = 5) | 36.5 to 60 (n = 5) |

| Unspecified silver tax | 121.5 to 195 (n = 24) | ∼51 to 420 (n = 4) | ∼114 to 218.75 (n = 28) | 75 to 240 (n = 106) | 78.75 to ∼234 (n = 134) |

| Total | 123.75 to 185 (n = 26) | ∼51 to 420 (n = 4) | ∼118 to 206.25 (n = 30) | 75 to 240 (n = 122) | 76.25 to ∼230 (n = 152) |

The middle 50 percent of barley-rent rates for tenant land with silver taxes was much higher than those for tenant land without silver taxes because the latter was less productive. When there were silver taxes, they ranged from 10 to 20 še (∼0.46 to ∼0.92 g) per iku. The middle 50 percent for the barley-rent rates of all tenant land is 76.25 to ∼230 sila 3 /iku, which fit well with the yields of 240 to 485 sila 3 /iku since the barley-rent rates at Ur III Girsu-Lagaš tended to range between one third and one half the yields (Steinkeller 1981: 126–27). If the yields of the middle 50 percent were about 200 to 400 sila 3 /iku after cultivation costs, the profits before tax for the middle 50 percent could range from roughly 125 to 175 sila 3 /iku. If the silver-tax range is averaged to 15 še/iku, it could be equivalent to about 25 sila 3 /iku based on the typical equivalency of 1 gin 2 of silver to 300 sila 3 of barley (Cripps 2017). While this silver tax would only apply for some of the tenant land, it can be conservatively applied to the entire profit range established above, resulting in a range from 100 to 150 sila 3 /iku. Moreover, it is important to note that the rent may have varied beyond the estimates here in various circumstances regarding the relationship between the landlord and tenant. Given the adjusted middle 50 percent of 2 to 14 iku, the middle 50 percent of tenants perhaps earned profits of 200 to 2,100 sila 3 of barley annually. The larger end of this range may have required further cultivation costs to account for hired workers, however. Given the conservative estimates here, this amount is still plausible perhaps. Overall, the nearly exclusive access that citizens had to voluntary work granted them significantly more economic autonomy and stability than un -il 2 and especially slaves.

3.7.3 Sustenance

The resources that would have sustained individuals and families during the Ur III period varied widely, but barley was an important staple for their diets and bartering. In terms of diet, it is difficult to determine how much any individual would have consumed daily, but it is assumed that adults needed at least 1 sila 3 with extra for bartering (Pottorf 2022: 267). Based on the data presented so far, it is possible to estimate annual barley-income ranges for five hypothetical families. The first and second were citizen families of six with two daughters aged zero to six and six to thirteen as well as two sons of the same age brackets, which would have been on the larger end of the average range. Both families were allotted subsistence land according to the middle 50 percent, though the first earned tenant-land profits according to the middle 50 percent, whereas the second earned wages. Since it is not clear how citizens used their days off to hire themselves out or rent tenant land, these hypothetical families only engaged in one of these options each. Actual families may have blended these options, however. The third and fourth families were un -il 2 of the same structure as the citizen families. The third family was allotted only barley monthly, and the fourth received a combination of monthly barley allotments and an annual subsistence-land share according to the middle 50 percent. The fifth family was an enslaved family in an administrative household, including a mother and two daughters aged zero to six and six to thirteen, which was only allotted barley monthly. As such, the annual barley-income ranges and daily barley-amount ranges per individual for these families are enumerated in Table 6.

Annual barley-income ranges and daily barley-amount ranges per individual for hypothetical citizen, un -il 2 , and enslaved families in Umma.

| Family type | Annual barley-allotment range (in sila3) | Annual subsistence-land barley-yield range (in sila3) | Annual tenant-land barley-profit range (in sila3) | Annual barley-wages range (in sila3) | Total annual barley-income range (in sila3) and |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| daily barley-amount range per individual (in sila3) | |||||

| Citizen families of six | – | 1,800 to 5,400 | 200 to 2,100 | – | 2,000 to 7,500 |

| ∼0.93 to ∼3.47 | |||||

| – | 1,800 to 5,400 | – | 200 to 750 | 2,000 to 6,150 | |

| ∼0.93 to ∼2.85 | |||||

| un -il 2 families of six | 1,800 to 2,580 | – | – | – | 1,800 to 2,580 |

| ∼0.83 to ∼1.19 | |||||

| 720 to 960 | 600 to 1,400 | – | – | 1,320 to 2,360 | |

| ∼0.61 to ∼1.09 | |||||

| Enslaved family of three | 720 to 960 | – | – | – | 720 to 960 |

| ∼0.67 to ∼0.89 |

Although the daily amounts per individual could be more finely tuned to account for differences between adults and children, clearly all the families except for the citizen families would have struggled to have or maintain economic stability. As for the citizen families, some may have earned little more than the un -il 2 families, but their earning potentials were vastly higher. The un -il 2 family allotted only barley monthly would have had little flexibility, but the un -il 2 family with subsistence land could have been significantly wealthier if their yield was greater than the estimate used here or if they were allotted well above the average. At least more than 9 iku, if not less, was an outlier for them, however. The enslaved family was the most impoverished, of course, and there was little flexibility in how much they could earn annually. It is important to add that families could have obtained other kinds of tenant land and commodities, including privately owned orchards (Steinkeller 1999: 294). All these families were also allotted wool or garments as well as other commodities for their sustenance, as mentioned above.

4 Conclusions

un -il 2 were a serflike order distinguished by their in-between status in comparison to the citizen and slave orders especially with regard to their economic conditions. Like slaves, un -il 2 usually lacked economic autonomy and stability because they were conscripted full time all year and typically held poorly compensated occupations. However, like citizens, they could be compensated with subsistence land, sometimes significant amounts depending on their occupations, and they could perhaps rarely rent tenant land. Nevertheless, only the few wealthier un -il 2 with better-compensated occupations would have experienced some autonomy and stability. Moreover, typically male un -il 2 , like male citizens, could be temporarily exempted from conscription to support their parents, which was likely not a possibility for slaves. Their terminology could distinguish them clearly if they were male, but female un -il 2 and slaves were usually described as simply geme 2 . Their origins are poorly detailed, but many of them were likely impoverished natives who inherited their order from previous generations of serflike individuals, such as carriers documented during the Early Dynastic period. While it is difficult to reconstruct their family lives, many of them probably maintained nuclear and extended families similar to citizen families. Their housing and legal rights are the least understood, unfortunately. They may have been housed by those upon whom they were dependent, but if they could afford housing, it was probably lower in quality on average than the housing for citizens. While they were legally free like citizens, they lacked mobility due to their full-time conscription. Although un -il 2 are best attested during the Ur III period, they are indicative of a larger phenomenon of individuals that were neither as free as citizens nor as unfree as slaves, economically and legally, in the ancient Near East.

Acknowledgments

I want to thank Vitali Bartash, Felix Rauchhaus, Piotr Steinkeller, and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful feedback as well as the British Museum for the opportunity to collate Nisaba 11: 34; Orient 21, p. 2; and SNAT 508.

Collations are given in Table 7, and the collated signs are underlined unless they are omitted.

Collations.

| Text | Line | Transliteration with underlined collations |

|---|---|---|

| AnOr 1: 49 | obv. i 31 | 0.0.0 ½ gan2 0.1.0 Lu2-kal-la ⸢aga3 -/us 2 ⸣ |

| obv. ii 21 | 0.0.1 ½ gan2 1.1.0 gu[r] | |

| rev. i 7′ | 0.0.4 ½ ⸢¼ gan2 4 ⸣ .2.3 gur | |

| AnOr 7: 374 | obv. iv′ 11′ | 0.0.2 gan2 1.2.3 gur |

| BDTNS 059327 | obv. iii 3 | 0.1.0 gan2 ⸢ 4 ⸣ .0.0 gur |

| obv. iv 17 | 0.1.0 gan2 6.0.0 gur | |

| obv. iv 21 | 0.1.0 gan2 ⸢ 6 ⸣ .0.0 gur | |

| obv. iv 25 | 0.0.2 gan2 2 !(3).0.0 gur | |

| rev. i 1 | 0.0.2 gan2 1+[1.0.0 gur] | |

| rev. i 3 | 0.0.2 gan2 2.[0.0 gur] | |

| rev. i 21 | 0.1.0 gan2 3.0.0 gur | |

| rev. i 29 | 0.0.3 gan2 ⸢ 1 ⸣.2.3 gur | |

| rev. ii 15 | 0.0.3 gan2 3.0.0 gur | |

| rev. ii 17 | 0.0.2 gan2 2.0.0 gur | |

| rev. ii 19 | 0.0.2 gan2 2.0.0 gur | |

| BIN 5: 277 | rev. ii 2 (CDLI) | 0.1.1 ¼ gan2 6.3.0 gur |

| CUSAS 39: 138 | obv. iii 2′ | 0.0.3 gan2 ⸢ 6 ⸣.0.0 ⸢gur⸣ |

| obv. vi 6′ | 0.0.1 ½ gan2 3.0.0 ⸢gur⸣ | |

| rev. iv 19′ | 0.0.1 ½ gan2 1.2.3 gur | |

| MVN 4: 3 | obv. 9 | 0.0.2 ¼ gan2 2.0.0 gur-ta |

| Nik. 2: 236 | rev. ii 19 | šu-nigin2 5.2.5 ½ gan2 |

| Nisaba 11: 34 | rev. i 21a | 0.0.3 gan2 0.3.2-ta sahar ud |

| Nisaba 33: 126 | obv. 4 | 0.0.1 ½ gan2 0.1.1 Ur-sukkal sipa |

| obv. 5 | 0.0.0 ½ ¼ gan2 0.2.1 5 sila3 Lu2-/dŠara2 dumu Da-zi-gi4-na | |

| obv. 6 | 0.0.0 ½ gan2 0.0.4 5 sila3 Lugal-/ma2-gur8-re | |

| rev. 3 | 0.0.0 ½ gan2 0.1.3 Ab-ba-sig5 / dumu Gu2-ru | |

| rev. 4 | 0.0.0 ½ gan2 0.2.3 Puzur4-dŠara2 | |

| Nisaba 33: 521 | obv. i 1 | 0.0.1 ½ gan2 še-ba u3 kaš / 0.2.3 |

| obv. i 6 | 0.0.0 ½ gan2 0.2.0 Lugal-inim-ge-na / dumu Ša3-ku3-ge | |

| obv. i 8 | 0.0.0 ½ gan2 0.1.0 Ur-dBa-u2 | |

| obv. ii 1 | 0.0.1 ½ gan2 0.⸢1⸣.3 ⸢Šu?-x-x⸣ | |

| obv. ii 2 | 0.0.0 ½ gan2 0.2. ⸢ 3 x-x(-x) ⸣ | |

| Organisation administrative, Diss. 1, p. 202 Talon-Vanderroost 1 | rev. viii 26 | aš ama Lu2-uru-mu |

| Orient 21, p. 2 | obv. i 7′ | 5.0.1 gan2 1.3.2-ta |

| obv. vi 7′ | A-tu ⸢ dub ⸣ -[sar] | |

| OrSP 47–49: 481 | obv. i 16 | 0.0.2 ½ gan2 0.4.0-ta |

| obv. i 18 | 0.0.4 ½ gan2 0.4.0-ta | |

| obv. i 20 | 0.0.4 ½ ¼ gan2 0.4.0-ta | |

| obv. i 22 | 0.0.4 ½ ¼ gan2 0.4.0-ta | |

| obv. ii 2 | 0.0.4 ½ gan2 0. ⸢ 4 ⸣ .0-ta | |

| SNAT 508 | obv. 1 | 0.2.2 gan2 še-ba u3 kaš 7.0.0 gur [maš tuku] |

| obv. 8 | 0.0.3 gan2 1.2.3 gur maš tuku | |

| obv. 12 | 0.1.0 gan2 3.0.0 gur maš tuku | |

| rev. 16 | šu-nigin2 še-bi 48.2.[0 gur] | |

| ŠA 135 (LXXIV) | obv. 7′ | 0.1.0 gan2 6.0.0 gur […] |

-

a sahar ud is uncertain, but that is how these signs are currently read according to BDTNS and CDLI.

References

Attinger, Pascal. 2021. Glossaire sumérien-français: Principalement des textes littéraires paléobabyloniens. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.10.13173/9783447116169Search in Google Scholar

Bartash, Vitali. 2020. “Coerced Human Mobility and Elite Social Networks in Early Dynastic Iraq and Iran.” JANEH 7 (1): 25–57. https://doi.org/10.1515/janeh-2019-0006.Search in Google Scholar

Bartash, Vitali. In this issue. “Humans as Votive Gifts and the Question of ‘Temple Slavery’ in Early Mesopotamia.” In Beyond Slavery and Freedom in Ancient Mesopotamia, edited by Vitali Bartash, and Andrew Pottorf. JANEH 12 (1).Search in Google Scholar

Bartash, Vitali, and Andrew, Pottorf. In this issue. “Muškēnum in Third-Millennium BC Mesopotamia.” In Beyond Slavery and Freedom in Ancient Mesopotamia, edited by Vitali Bartash, and Andrew Pottorf. JANEH 12 (1).Search in Google Scholar

Bendix, Reinhard. 1960. Max Weber: An Intellectual Portrait. Garden City, NY: Doubleday.Search in Google Scholar

Borrelli, Noemi. 2013. Managing the Land: Agricultural Administration in the Province of Ĝirsu/Lagaš During the Ur III Period. PhD diss., Università degli Studi di Napoli “L’orientale.”Search in Google Scholar

Burger, Thomas. 1985. “Power and Stratification: Max Weber and beyond.” In Theory of liberty, legitimacy and power: new directions in the intellectual and scientific legacy of Max Weber, edited by Vatro Murvar, 11–39. International Library of Sociology. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.Search in Google Scholar

Civil, Miguel. 1985. “Sur les ‘livres d’écolier’ à l’époque paléo-babylonienne.” In Miscellanea babylonica: Mélanges offerts à Maurice Birot, edited by J.-M. Durand, and J.-R. Kupper, 67–78. Paris: Éditions Recherche sur les Civilisations.Search in Google Scholar

Civil, Miguel. 1994. The Farmer’s Instructions: A Sumerian Agricultural Manual. AuOr – Supplementa 5. Sabadell: Editorial AUSA.Search in Google Scholar

Cohen, Mark E. 2023. An Annotated Sumerian Dictionary. University Park: Eisenbrauns.10.1515/9781646022212Search in Google Scholar

Cripps, Eric L. 2017. “The Structure of Prices in the Neo-Sumerian Economy (I): Barley:Silver Price Ratios.” CDLJ 2017 (2), https://cdli.mpiwg-berlin.mpg.de/articles/cdlj/2017-2.Search in Google Scholar

Culbertson, Laura. 2024. “Slaves, serfs, and foreigners.” In Society and the Individual in Ancient Mesopotamia, edited by Laura Culbertson, and Gonzalo Rubio, 241–68. SANER 33. Berlin: de Gruyter.10.1515/9781501517655-007Search in Google Scholar

Dahrendorf, Ralf. 1959. Class and Class Conflict in Industrial Society. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.Search in Google Scholar

Engerman, Stanley L. 2000. “Slavery at Different Times and Places.” American Historical Review 105 (2): 480–84, https://doi.org/10.2307/1571463.Search in Google Scholar

Jursa, Michael. 2010. Aspects of the Economic History of Babylonia in the First Millennium BC: Economic Geography, Economic Mentalities, Agriculture, the Use of Money and the Problem of Economic Growth, vol. 4 of Veröffentlichungen zur Wirtschaftsgeschichte Babyloniens im 1. Jahrtausend v. Chr. AOAT 377. Münster: Ugarit-Verlag.Search in Google Scholar

Kleber, Kristin. 2011. “Neither Slave nor Truly Free: The Status of the Dependents of Babylonian Temple Households.” In Slaves and Households in the Near East, edited by Laura Culbertson, 101–11. OIS 7. Chicago: Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.Search in Google Scholar

Lambert, W. G., and Ryan D. Winters. 2023. An = Anum and Related Lists: God Lists of Ancient Mesopotamia, vol. 1, edited by Andrew George, and Manfred Krebernik. ORA 54. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck.10.1628/978-3-16-161383-8Search in Google Scholar

Maekawa, Kazuya. 1977. “The Rent of the Tenant Field (gán-APIN.LAL) in Lagash.” Zinbun 14: 1–54.Search in Google Scholar

Maekawa, Kazuya. 1984. “Cereal cultivation in the Ur III period.” BSA 1: 73–96.Search in Google Scholar

Maekawa, Kazuya. 1986. “The Agricultural Texts of Ur III Lagash of the British Museum (IV).” Zinbun 21: 91–157.Search in Google Scholar

Molina, Manuel. 2016. “Archives and Bookkeeping in Southern Mesopotamia during the Ur III Period.” Comptabilités 8, http://comptabilites.revues.org/1980.Search in Google Scholar

Neumann, H. 2004. “Pacht. A. Präsargonisch bis Ur III.” RlA 10 (3/4): 167–70.Search in Google Scholar

Omodei, R. A. 1982. “Beyond the Neo-Weberian Concept of Status.” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Sociology 18 (2): 196–213. https://doi.org/10.1177/144078338201800206.Search in Google Scholar

Pottorf, Andrew Richard. 2022. Social Stratification in Southern Mesopotamia during the Third Dynasty of Ur (ca. 2100–2000 BCE). PhD diss., Harvard University.Search in Google Scholar

Pottorf, Andrew. Forthcoming. “From the Ground Up: The Foundational Role of the Land-Tenure System for Social Stratification in Southern Mesopotamia during the Ur III Period.” In Concepts of Governance and the Study of Ancient Near Eastern Societies, edited by Eva Cancik-Kirschbaum, Jörg Klinger, and Aron Dornauer. Melammu Symposia 16. Vienna: Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften.Search in Google Scholar

Pottorf, Andrew, and Andrew, A. N. Deloucas. 2024. “The Groton School Cuneiform-Text Collection.” CDLB 2024 (2), https://cdli.mpiwg-berlin.mpg.de/articles/cdlb/2024-2.Search in Google Scholar

Reculeau, Hervé. 2013. “Awīlum, muškēnum, and wardum.” In The Encyclopedia of Ancient History, vol. 2, edited by Roger S. Bagnall, Kai Brodersen, Craige B. Champion, Andrew Erskine, and Sabine R. Huebner, 998–99. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.Search in Google Scholar

Roth, T. 1997. Law Collections from Mesopotamia and Asia Minor, edited by Piotr Michalowski. 2nd ed. WAW 6. Atlanta: Scholars Press.10.2307/jj.25577265Search in Google Scholar

Sallaberger, Walther. 1993. Der kultische Kalender der Ur-III Zeit, part 1. UAVA 7/1. Berlin: de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110889253Search in Google Scholar

Snell, Daniel C. 1989. “The Lager Texts: Transliterations, Translations and Notes.” ASJ 11: 155–224.Search in Google Scholar

Steinkeller, Piotr. 1981. “The Renting of Fields in Early Mesopotamia and the Development of the Concept of ‘Interest’ in Sumerian.” JESHO 24 (2): 113–45, https://doi.org/10.1163/156852081x00068.Search in Google Scholar

Steinkeller, Piotr. 1999. “Land-Tenure Conditions in Third-Millennium Babylonia: The Problem of Regional Variation.” In Urbanization and Land Ownership in the Ancient Near East: A Colloquium Held at New York University, November 1996, and The Oriental Institute, St. Petersburg, Russia, May 1997, edited by Michael Hudson, and Baruch A. Levine, 289–329. Peabody Museum Bulletin 7. Cambridge: Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University.Search in Google Scholar

Steinkeller, Piotr. 2013. “Corvée Labor in Ur III Times.” In From the 21st Century b.c. to the 21st Century a.d.: Proceedings of the International Conference on Sumerian Studies Held in Madrid, 22–24 July 2010, edited by Steven J. Garfinkle, and Manuel Molina, 347–424. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns.10.1515/9781575068718-021Search in Google Scholar

Steinkeller, Piotr. 2015. “Introduction. Labor in the Early States: An Early Mesopotamian Perspective.” In Labor in the Ancient World, edited by Piotr Steinkeller, and Michael Hudson, 1–35. The International Scholars Conference on Ancient Near Eastern Economies 5. Dresden: ISLET.Search in Google Scholar

Steinkeller, Piotr. 2017. History, Texts and Art in Early Babylonia: Three Essays. SANER 15. Berlin: de Gruyter.10.1515/9781501504778Search in Google Scholar

Steinkeller, Piotr. 2018. “Care for the Elderly in Ur III Times: Some New Insights.” ZA 108 (2): 136–42. https://doi.org/10.1515/za-2018-0009.Search in Google Scholar

Steinkeller, Piotr. 2022. “On Prostitutes, Midwives and Tavern-Keepers in Third Millennium BC Babylonia.” Kaskal 19: 1–38.Search in Google Scholar

Tenney, Jonathan S. 2017. “Babylonian Populations, Servility, and Cuneiform Records.” JESHO 60 (6): 715–87.10.1163/15685209-12341440Search in Google Scholar

Uchitel, Alexander. 1992. “Erín-èš-didli.” ASJ 14: 317–38.10.1007/BF03025211Search in Google Scholar

Weber, Max. 1978. Economy and Society: An Outline of Interpretive Sociology, edited by Guenther Roth, and Claus Wittich, translated by Ephraim Fischoff, Hans Gerth, A. M. Henderson, Ferdinand Kolegar Mills, Talcott Parsons, Max Rheinstein, Guenther Roth, Edward Shils, and Claus Wittich. 2 vols. Berkeley: University of California Press.Search in Google Scholar

Yoffee, Norman. 2012. “The Meanings of Law in Ancient Mesopotamia.” In Wissenskultur im Alten Orient: Weltanschauung, Wissenschaften, Techniken, Technologien: 4. Internationales Colloquium der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft, 20.–22. Februar 2002, Münster, edited by Hans Neumann, and Susanne Paulus, 87–93. CDOG 4. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Introduction

- Beyond Slavery and Freedom in Ancient Mesopotamia

- Articles

- Muškēnum in Third-Millennium BC Mesopotamia

- Humans as Donations and the Question of Temple Slavery in Early Mesopotamia

- un-il2 (“Menials”) as a Serflike Social Stratum during the Ur III Period

- The Precarious Inheritance Rights of Adopted Slaves During the Old Babylonian Period

- The Status of War Prisoners at Uruk in the Old Babylonian Period

- Detention as Liminal Space During the Middle Babylonian Period

- The Hoax of Semi-Freedom in Babylonia

- Beyond Slavery and Freedom in Ancient Mesopotamia: A Response

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Introduction

- Beyond Slavery and Freedom in Ancient Mesopotamia

- Articles

- Muškēnum in Third-Millennium BC Mesopotamia

- Humans as Donations and the Question of Temple Slavery in Early Mesopotamia

- un-il2 (“Menials”) as a Serflike Social Stratum during the Ur III Period

- The Precarious Inheritance Rights of Adopted Slaves During the Old Babylonian Period

- The Status of War Prisoners at Uruk in the Old Babylonian Period

- Detention as Liminal Space During the Middle Babylonian Period

- The Hoax of Semi-Freedom in Babylonia

- Beyond Slavery and Freedom in Ancient Mesopotamia: A Response