Abstract

Research indicates that the news media plays an important role in discursively constructing social identities through representations of ‘otherness.’ Guided by the politics of belonging, gender nationalism, and the argument that non-belonging is ascribed to Muslim women’s bodies through representations in the news media, this article examines discourse about the burkini – a type of swimsuit worn by some Muslim women – in the German press. Employing a multilevel critical discourse-analytical approach to the study of follow-ups made in online newspaper comment sections, it combines an initial content analysis focused on thematic patterns in discourse topics with an analysis of argumentation schemes. It focuses on how commenters utilise referential strategies to discursively frame the burkini in exclusionary terms. The findings indicate that while the burkini is highly contested particularly regarding sociocultural difference, integration, and gender equality, overall, it functions as a marker of non-belonging in German discourse.

Zusammenfassung

Forschungsergebnisse zeigen, dass die Medien durch die Darstellung von „Andersartigkeit“ eine wichtige Rolle bei der diskursiven Konstruktion sozialer Identitäten spielen. Ausgehend von der Politik der Zugehörigkeit, dem Gender-Nationalismus und der These, dass muslimischen Frauen durch Darstellungen in den Medien Nichtzugehörigkeit zugeschrieben wird, untersucht dieser Artikel den Diskurs über den Burkini – eine Art Badeanzug, der von einigen muslimischen Frauen getragen wird – in der deutschen Presse. Unter Verwendung eines mehrstufigen kritischen diskursanalytischen Ansatzes zur Untersuchung von Follow-ups in Online-Zeitungskommentaren wird eine erste Inhaltsanalyse mit Schwerpunkt auf thematischen Mustern in den Diskursthemen mit einer Analyse der Argumentationsschemata kombiniert. Der Fokus liegt darauf, wie Kommentatoren Referenzstrategien nutzen, um den Burkini diskursiv in ausgrenzenden Begriffen zu framen. Die Ergebnisse zeigen, dass der Burkini zwar insbesondere im Hinblick auf soziokulturelle Unterschiede, Integration und Geschlechtergleichstellung sehr kontrovers diskutiert wird, insgesamt jedoch im deutschen Diskurs als Marker für Nichtzugehörigkeit fungiert.

Résumé

Des recherches montrent que les médias jouent un rôle important dans la construction discursive des identités sociales à travers des représentations de l’ « altérité ». Guidé par les politiques d’appartenance, de nationalisme sexuel et l’argument selon lequel la non-appartenance est attribuée aux corps des femmes musulmanes à travers des représentations dans les médias, cet article examine le discours sur le burkini – une sorte de maillot de bain porté par certaines femmes musulmanes – dans la presse germanique. En appliquant une approche analytique multiniveau du discours critique à l’étude des suivis des pages de commentaires des journaux en ligne, il combine une analyse de contenu initiale centrée sur les tendances thématiques dans les sujets de discours et une analyse des schémas argumentatifs. Il se concentre sur la manière dont les commentateurs utilisent des stratégies référentielles pour cadrer discursivement le burkini en termes d’exclusion. Les résultats montrent que, bien que le burkini soit fortement contesté, notamment en ce qui concerne les différences socioculturelles, l’intégration et l’égalité des genres en général, il fonctionne comme un marqueur de non-appartenance dans le discours germanique.

1 Introduction

“Burkinis für alle! [Burkinis for everyone!]” proclaimed the attention-grabbing headline in Die Zeit, a left-leaning weekly newspaper of record (Luig 2018).[1] “Die Prinzipienlosigkeit der Burkini-Befürworter [The unprincipledness of burkini advocates]” countered an equally engaging headline in the right-leaning daily broadsheet Die Welt (Kelle 2018). In Germany, where the aforementioned opinion columns were published, the burkini – a type of swimsuit worn by some Muslim women – not only has become a point of contention in mandatory coeducational swimming lessons in state-funded secondary schools, but, increasingly, is also part-and-parcel of what Wodak (2021) terms the ‘politics of fear,’ or the myriad ways in which discourse constructs ‘us’ and politicises anxiety about ‘them.’ In this sense, while the Die Zeit editor asks the reader what at first glance appears to be a straight-forward question: “Ob Ganzkörperanzug oder Bikini: Warum können Mädchen im Schwimmunterricht nicht einfach anziehen, was sie wollen? [Whether full-body swimsuits or bikinis: Why can’t girls just wear what they want in swimming lessons?]” (Luig 2018), the answer is far more complex. In fact, discourse about the burkini, particularly on the right, but also on the left, often combines a racialised body politics with gender nationalism to justify the notion of Muslim cultural alterity and non-belonging.

Focusing on how political ideologies about gender and integration are reflected and recontextualised in everyday digital discourse, this article takes a multilevel critical discourse-analytical approach to the study of these issues by examining how the burkini is framed by readers of German regional and national newspapers. In doing so, it builds upon work examining the discursive portrayal of veiled Muslim women in European news media (e. g., Davis 2025; Korteweg and Yurdakul 2014, 2021; Schiffer 2023). Analyses of Islam-related coverage in German newspapers, in particular, indicate that Muslims are framed not only as a homogeneous group according to stereotypes and recurring argumentation schemes, but, as a large, multinational meta-analysis also found (Ahmed and Matthes 2017), commonly, in terms of extremism, political unrest, migration, and debates about “women, their rights, and their clothing” (Richter and Paasch-Colberg 2023; Schmidt 2022; Shooman 2014). A key locus upon which national belonging is discursively negotiated, studies show that Muslim body-coverings are framed by the German press as non-conforming, contrary to the constitutional right of gender equality, and, as a result, a major obstacle to integration (Ehrkamp 2010; Korteweg and Yurdakul 2014). Indeed, Muslim practices are often framed in terms of unintegration (Fuller 2019). These frames prime the reader to associate objects – for example, in this case, the burkini – with specific topics irrespective of context (Schiffer 2023). Work examining public policy and political discourse, generally, also suggests that gender equality is regularly instrumentalised as a liberal-democratic value in boundary-marking between the European ‘self’ and Muslim ‘other’ with dress serving as a visual foil and marker of societal ‘otherness’ (e. g., Rosenberger and Sauer 2012). However, research gaps remain – namely, limited analysis of veiled Muslim women in the German press especially following the passage of the 2016 Integration Act (Richter and Paasch-Colberg 2023), the burkini compared to other forms of Muslim body-coverings, and online news media particularly newspaper comment sections from a critical discourse studies perspective (Ahmed and Matthes 2017; Dorostkar and Preisinger 2017).

Consequently, in this article, specific attention is given to follow-ups, or comments posted to online comment sections in response to news articles and opinion columns about a key discursive event – reports that a state-funded secondary school (Gymnasium) in Germany’s largest and most densely populated polycentric urban area, the Rhine-Ruhr metropolitan region in the state of North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW), had supplied female students with burkinis for use in swimming lessons in 2018.[2] As the abovementioned headlines illustrate, the press, echoing statements issued by the school principal, as well as regional and federal politicians, framed the ensuing public debate in terms of the appropriateness of the burkini and its role in fostering integration, especially vis-à-vis gender equality. These issues are not new; integration also informed a 2016 Federal Constitutional Court judgment that established a new legal precedent by ruling that a Muslim student could not be excused from coeducational swimming lessons on religious grounds, in part, because participation could occur in a burkini. Notably, in both cases, the emphasis on integration obscures the fact that ‘migrant’ and ‘Muslim’ are not coreferential – indeed, nearly half of all Muslims in Germany are German nationals (Pfündel et al. 2021). It also underscores how Muslim women’s dress and behaviour are scrutinised for evidence of individualised integration and adherence to liberal-democratic norms (Davis 2023), even as the act of veiling remains largely stigmatised in German public discourse and a subject of societal concern (Korteweg and Yurdakul 2014).

To investigate how these issues are reflected and recontextualised in follow-ups, the article begins with a short overview of discourse about the burkini in German state-funded education. It next introduces the three interconnected theoretical frameworks that inform and guide the analysis: the politics of belonging (Yuval-Davis 2006, 2011), gender nationalism (Hadj Abdou 2017), and non-belonging (Korteweg and Yurdakul 2024). Together, these indicate that power is negotiated through gender nationalist discourse to delineate societal differences reflective of the politics of belonging and that the news media, in particular, acts as a conduit whereby non-belonging is ascribed onto Muslim women’s bodies according to gendered and racialised boundaries. After detailing the research questions, materials, and methodological framework, the article reviews the major themes and argumentation schemes that emerged from the analysis, as well as how these employ referential strategies to discursively frame the burkini in exclusionary terms. It concludes by discussing the major findings and pointing towards further areas of study.

2 Contextual overview

Discourse about the burkini – specifically, whether one may wear it or be excused from mandatory coeducational swimming lessons altogether on religious grounds – on the one hand, centres on the issue of religious freedom and accommodation and on the other, on the integration of migrants into German society. While this article focuses on examples of the latter in newspaper comment sections, the former remains a key facet of socio-political discourse about the burkini. In keeping with a critically contextualised approach to discourse, both are detailed here in brief; attention is given to the legal judgments and educators featured in political news about the burkini. These – along with statements by prominent politicians, which are further detailed in tandem with the analysis of newspaper comments – are reiterated in news articles and opinion pieces and thus, the discourse most often repeated and reinterpreted in online public forums.

While Germany is a secular state, religion plays a role in public life. The German Basic Law provides individuals with the constitutional right to freedom of faith and conscience, parents with control over their children’s upbringing, and individual states with the right to administer education.[3] Each state also has the power “to prohibit the wearing of religious, political and philosophical symbols and to re-define the balance between state neutrality and religious manifestation in public schools as long as those limitations are in line with fundamental freedoms” (Baldi 2021: 75). As a result, when disputes about students’ religious freedom and accommodation have arisen, ultimately these often must be resolved by the judiciary. The first major adjudication on this matter – a 1993 Federal Administrative Court judgment – found that students could be exempt from coeducational physical education classes on religious grounds if a school could not offer gender-separate instruction.[4] However, in 2011, a Gymnasium in the city of Frankfurt am Main in the state of Hessen denied a fifth-grade student’s request to be exempt from coeducational swimming lessons by arguing that she could attend in a burkini. Notably, when the case was settled on appeal by the Federal Constitutional Court in 2016, the justices agreed with the school – as had the Administrative Court of Frankfurt am Main, the Hessian Administrative Court, and the Federal Administrative Court before them.[5] This decision not only overturned established precedent, but realigned the politics of belonging to include the burkini by emphasising individualised integration and the state’s role in socialisation and enculturation (Davis 2023).

Yet, the 2016 judgment did little to settle the issue. In fact, less than two years later in 2018, burkinis again made news when media outlets reported that a Gymnasium in Herne, the most densely-populated city in the Rhine-Ruhr metropolitan region had provided the garments for use in coeducational swimming lessons. First reported by the Westdeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung regional newspaper, the privately funded, student-led initiative was undertaken after 34 ‘integration students’ (Integrationsschüler) enrolled at the school at the height of the ‘refugee crisis’ in 2016 (Poll 2018). At this time, the 2016 Integration Act had instituted a policy of ‘support and challenge’ (Fördern und Fordern) that required individuals to show ‘successful’ integration in order to access various government benefits. According to news reports, the decision to purchase twenty burkinis was also rooted in long-term efforts to provide disadvantaged pupils with school supplies and sports equipment (Bolsmann et al. 2018; Poll 2018). Name-brand burkinis can be expensive and ‘homemade’ (Eigenbau) versions composed of a synthetic shirt and leggings are often not permitted in municipal swimming pools (Niewerth 2018 a, 2018b), which, in general, is where such lessons take place. Also, according to the principal, the newly arrived students had little to no swimming experience and refused to attend lessons on religious grounds (Poll 2018). Thus, he said the school sought “’Teilhabe im Rahmen der gesetzlichen Vorgaben ermöglichen [to enable participation within the scope of the legal requirements]’” enumerated in the Federal Constitutional Court’s 2016 judgment by providing free rental burkinis – a decision supported by Herne’s City Council, Integration Council (Integrationsräte), and the Arnsberg Government District (Bolsmann et al. 2018; Poll 2018). Just as the courts had stressed individualised integration in their rulings, so too, did the principal, who told the press, “’Ich vertrete aber eine klare Haltung: Bei uns soll jeder schwimmen lernen und dafür schaffe ich die Bedingungen...Schwimmen ist Integration, das gehört in Deutschland zur Kultur [I take a clear stance: everyone should learn to swim here and I create the conditions for this...swimming is integration, it’s part of the German culture]’” (Poll 2018).

3 Theoretical framework

To better conceptualise how political ideologies about gender and integration are reflected and recontextualised in discourse about the burkini, this article relies upon three interconnected frameworks centred on the concept of ‘belonging’:

First, Yuval-Davis (2006, 2011) theorises that while ‘belonging’ is naturalised in terms of social categories, identifications, and normative value systems, the ‘politics of belonging’ is the political project that constructs, maintains, and reproduces the intersectional boundaries of inclusion and exclusion. The ability to demarcate who ‘belongs’ is governed by access to power and as a result, social categories and their boundaries – whether physical or symbolic – are often most salient when their “hegemonic naturalness” is contested (Yuval-Davis 2011: 91). Gender plays a major role in this process; women are framed in nationalist discourse as ‘border guards’ whose actions and appearance symbolically embody sociocultural norms and values representative of the nation (Yuval-Davis 1997).

Second, research indicates that gender equality is increasingly employed in European political discourse as a means of boundary-marking. This requires discursively spatialising and temporalising Europe (e. g., Krzyżanowski 2009), as well as ‘conceptual flipsiding’ liberal-democratic values for illiberal gains (Krzyżanowski and Krzyżanowska 2024). Hadj Abdou (2017) describes this phenomenon as ‘gender nationalism,’ which is the term used here, but others have employed ‘femonationalism’ (Farris 2017) and ‘gendernativism’ (Dahinden and Manser-Egli 2023) to reference related ideas. For example, Hadj Abdou (2017: 85) argues that by framing gender equality as an established liberal-democratic value, gender nationalist rhetoric positions a liberal European ‘self’ in binary opposition to an incompatible Muslim ‘other’ responsible for “(re)importing gender inequality.” Similarly, Farris (2017) shows that right-wing politicians and feminists utilise tropes – like that of the veiled Muslim woman as the oppressed victim or the incompatibility of ‘Muslimness,’ in general – to justify anti-Muslim policies. Dahinden and Manser-Egli (2023) further contend that comparable language is widespread throughout society and functions to reinforce in-group cohesion. According to Sauer (2016: 118), such discourse, especially in relation to Muslim head and body coverings, is a part of a new, gendered politics of belonging in which attention to bodily practices serves as a form of governance that symbolically defines “who belongs and who does not, who is a ‘normal’ citizen and who is not and, hence, who has access to rights and who does not.”

Lastly, bridging the politics of belonging and gender nationalism, Korteweg and Yurdakul’s (2024) theoretical model of ‘non-belonging’ provides a framework for focusing attention on the discursive portrayal of Muslim women in news media and its subsequent digital mediation in newspaper comment sections. They argue that non-belonging is fostered through representations ascribed to bodies in gendered and racialised ways, in part, through boundary formations in the news media that specifically exclude Muslims. Starting from the position that “non-belonging is not simply the absence of belonging,” but, rather, the result of an intersectional, context-specific process of boundary-making (Korteweg and Yurdakul 2024: 294), their model suggests how non-belonging is reified, especially in terms of the mediatisation of political speech about Muslims in Europe.

Together, these interconnected frameworks inform the research design. They indicate that while power is negotiated through gender nationalist discourse to delineate societal differences reflective of the politics of belonging, the press not only amplifies, but also ascribes non-belonging onto Muslim women’s bodies according to gendered and racialised boundaries. This informs how the burkini is framed by readers of German regional and national newspapers in terms of gender and integration.

4 Research design

4.1 Research questions

Guided by the following research questions, this article examines a corpus of online user-generated newspaper comments about burkinis in German state-funded education:

RQ-1. Which major themes emerge from the corpus; specifically, is the burkini discursively framed in terms of political ideologies about gender and integration and if so, do these framings differ by newspaper comment sections across ideological lines?

RQ-2. Which argumentation schemes are utilised in follow-ups about gender and integration; specifically, how is the burkini framed in terms of referential strategies to demarcate exclusionary boundaries of non-belonging?

As such, it employs the multilevel critical discourse-analytical approach first developed by Wodak, et al. (2009) and advanced by Krzyżanowski (2010) for examining discourses of national identity and belonging by combining an initial content analysis focused on thematic patterns in the data (RQ-1) with an analysis focused on argumentation schemes (RQ-2).

4.2 Online user-generated newspaper comment corpus

Newspaper comment sections, such as that examined in this study, reflect the digital mediation of political discourse. An opinion genre situated at the “interface of language and sociality,” comment sections provide one of the most popular and widely accessible public forums for users to respond to political news media in interaction with others (Giltrow 2013: 717; Johansson 2015, 2017; Ruiz et al. 2011). They allow users to “integrate their personal experience into their comments, criticise and reframe news items, distance themselves from journalistic arguments, help other users understand particular aspects of an issue, and begin discussions with other users” in an iterative and dynamic fashion (Ziegele and Quiring 2013: 132). Accordingly, their analysis can show how the “discourse contributions of prominent public voices (politicians and other opinion leaders, including mainstream media but also marginal voices), are taken up, repeated, changed and reinterpreted by the wider public” (Musolff 2019: 342), which, in turn, may provide greater insight into how non-belonging is constructed and ascribed to specific bodily practices in the German national imagination. Also, as a type of follow-up, or any “communicative acts, in and through which a prior communicative act is accepted, challenged, or otherwise negotiated” (Berlin et al. 2015: 2), comments are organised according to hierarchical, nested discussion threads with news articles or opinion pieces initiating level-one responses, which, in turn, initiate level-two responses (Weizman 2015). In this sense, comments may be simultaneously responsive and initiative; for example, reproducing commentary through linguistic anchoring (e. g., quoting a prior comment) and recontextualising the object of discourse to negotiate meaning and spur further discussion (Johansson 2015, 2017; Weizman 2023).

For this study, a corpus of online user-generated newspaper comments (n=3,600) was compiled. The comments were posted as follow-ups made in response to news articles and opinion columns published in the online edition of two national newspapers: the liberal-leaning weekly newspaper of record Die Zeit and the conservative-leaning daily broadsheet Die Welt, as well as the Westdeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung, the largest regional newspaper in the Rhine-Ruhr conurbation. These media outlets provide a broad scope across the political spectrum. Excluding subscriber-only content, a total of 17 news articles and opinion columns written about the Herne burkini controversy in June and July 2018 were identified using key word searches (e. g., a Boolean search for ‘burkini’ and ‘Herne’) via each newspaper website’s search bar. Any post made ‘below the line’ in a publicly accessible, asynchronous comment section was manually extracted, transferred to a spreadsheet, and collated in nested discussion threads according to a numerical code rather than the source metadata (i. e., user names or publication date and time) then further anonymised with another random numerical code in accordance with ethical guidelines for the use of public data in news media research. This resulted in a corpus of 3,600 comments posted across 1,766 nested discussion threads, which, in the original German totals 173,957 words, or an average of 48.3 words per comment (see Table 1).

Corpus of online user-generated comments (n=3,600).

| Article | Comments | Discussion Threads | Words |

| Die Zeit | |||

| DZ-1 | 516 | 145 | 25,109 |

| DZ-2 | 1,128 | 389 | 66,730 |

| 1,644 | 534 | 91,970 | |

| Die Welt | |||

| DW-1 | 463 | 291 | 15,928 |

| DW-2 | 1,029 | 701 | 41,717 |

| DW-3 | 202 | 109 | 9,966 |

| 1,694 | 1,101 | 67,611 | |

| Westdeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung | |||

| WAZ-1 | 8 | 4 | 410 |

| WAZ-2 | 8 | 3 | 951 |

| WAZ-3 | 7 | 6 | 398 |

| WAZ-4 | 117 | 61 | 7,488 |

| WAZ-5 | 2 | 2 | 90 |

| WAZ-6 | 2 | 1 | 56 |

| WAZ-7 | 5 | 4 | 102 |

| WAZ-8 | 3 | 3 | 200 |

| WAZ-9 | 22 | 9 | 1,063 |

| WAZ-10 | 58 | 27 | 2,472 |

| WAZ-11 | 24 | 7 | 697 |

| WAZ-12 | 6 | 4 | 448 |

| 262 | 131 | 14,376 | |

| Total | 3,600 | 1,766 | 173,957 |

4.3 Content analysis

Content analysis was employed to determine which major themes emerged from the corpus and, in particular, to determine if the burkini was discursively framed in terms of political ideologies about gender and integration, as well as how these framings differ by newspaper comment sections across ideological lines (RQ-1). An empirical, objective means of categorising and classifying units of information, content analysis is the most widely-used method for the study of user-generated content (Naab and Sehl 2017). As a research technique, it is used to identify thematic patterns in data; its use here reflects the first stage of two-fold analysis in which contextually situated, topic-oriented themes are established before undertaking a critical discourse-analytical examination of argumentation schemes (RQ-2).

Specifically, a qualitative content analysis was undertaken following the procedure outlined by Bingham (2023) to sort, identify, categorise, and interpret data. This involved combining an initial coding frame with open, in vivo coding to systematically classify and code small units of information, such as repeated words or concepts. First, to sort the data, a coding frame based on the 11 major symbolic-interpretative constructs identified by Rosenberger and Sauer (2012) as part of their extensive study of veiling policies in eight European countries (e. g., ‘citizenship’ or ‘Europeanness – Westernism – modernity’) was devised by the coder. To increase the reliability and replicability of the analysis, their 32 subframes (e. g., ‘citizenship’ framed as ‘recognition of difference,’ ‘assimilation,’ and ‘integration’) were also noted. This not only anchored the analysis in earlier empirical research, but also allowed for deductive “lean coding” (Creswell 2013: 184) or what Saldaña (2013: 87) terms “descriptive coding” to inventory topics in the corpus. Next, to identify and categorise more detailed information, the data was reviewed, recoded, and refined through open, in vivo coding using words and concepts found in the comments. This inductively expanded and substantiated the initial coding frame while also ensuring that the analysis was responsive to the “words of real people” (Bernard 2006: 493). Lastly, to interpret the data, the codes were grouped into themes, or overarching conceptual patterns, based on line-by-line comparison of discursive framing and topical repetition (Ryan and Bernard 2003). Major themes (e. g., ‘sociopolitical difference and governance’) represent the most saliant discourses in the corpus. These were then subdivided into dominant argumentation schemes (e. g., ‘arguments related to secularism and democracy’) (see Table 2).

Major themes and argumentation schemes, corpus of online user-generated comments (n=3,600).

| Major Theme | Argumentation Schemes |

| Gender | –Arguments about gender in Germany, including those that use: o a positive or neutral frame (e. g., gender equality, female participation in society) o a negative frame (e. g., gender inequality, claims about needing to protect women and children) |

| Sociocultural difference and integration | –Arguments about German social norms, values, or national identity that focus on the perceived sociocultural differences of Muslims or migrants with non-Western backgrounds, including: o self- and other-presentation strategies (e. g., “we” / “us” / “our” / “German” / “the people” / “normal” versus “they” / “them” / “their” / “migrant” / “Muslims” / “abnormal”) –Arguments framing Germany as a modern, secular society in binary opposition to Muslim majority societies with a focus on perceived sociocultural differences past or present, including references to: o (western) civilization, the Occident, or European social norms, values or identity –Arguments about sociocultural difference and integration in Germany, including those that use: o a positive or neutral frame (e. g., references to the majority or minority, generally) o a negative frame (e. g., claims that Muslims exhibit foreign allegiance) |

| Sociopolitical difference and governance | –Arguments framing Islam as a political ideology –Arguments related to secularism, including references to: o secularism and state neutrality o secularism and democracy –Arguments about legal codes, including references to: o the Basic Law and associated constitutional rights or case law o the education mandate at the state or federal level –Arguments about the local, state, or federal government, including references to: o fiscal policy and social benefits o political representation o immigration and crime |

4.4 Critical discourse studies

An in-depth critical discourse studies-based analysis was employed to determine which argumentation schemes were utilised in follow-ups about gender and integration, as well as how the burkini was framed in terms of referential strategies demarcating exclusionary boundaries of non-belonging (RQ-2). Understanding discourse to be a form of ‘social practice’ that not only constitutes and provides meaning to the social world (e. g., social identities), but also reflects and (re)produces inequality according to intersecting forms of oppression (e. g., race/ethnicity, nationality, gender) (Fairclough and Wodak 1997: 258), critical discourse studies examines the interface between language and social dynamics. In this sense, while discourse may refer to language use, generally, it may also reference various discourses (e. g., gender nationalist discourse, anti-Muslim discourse) that reflect specific ideologies, which, in turn, influence perception of the social world and aid in boundary-marking (e. g., demarcating the ‘we’ in-group).

The specific methodological approach taken for this analysis is indebted to a framework devised for studying national identity and belonging (Krzyżanowski 2010; Wodak, et al. 2009). Argumentation schemes reflective of context- and content-specific claims about gender and integration were first inductively identified. These were then systematically analysed for referential strategies that have ideological effects and are used in boundary-marking like ‘positive self- and negative other-presentation’ (Reisigl and Wodak 2001; Wodak, et al. 2009) and the classification of social actors (e. g., pronoun versus noun usage, individualisation versus collectivisation) (Van Leeuwen 2008).

5 Results

5.1 Major themes in the corpus

The qualitative content analysis revealed three major themes in the corpus: (1) gender, (2) sociocultural difference and integration, and (3) sociopolitical difference and governance (see Table 2). The major theme of gender is characterised by topical references to gender equality/inequality, protection for women and children, and societal participation (e. g., in education or the labour market). The major theme of sociocultural difference and integration is thematically categorised according to discourses about the Occident (e. g., European social norms, values, or identity), Germany (e. g., German social norms, values, or identity; the ‘we’ in-group), sociocultural difference (e. g., diversity; integration), and Muslims in Germany (e. g., claims about self-isolation or integration resistance). The major theme of sociopolitical difference and governance reflects discourse related to Islamism (e. g., fear of Islamisation), German legal codes (e. g., the German Basic Law and associated constitutional rights), and federal, state, or local government (e. g., fiscal policy and social benefits; political representation). Together, these major themes represent the most salient topics embedded in the corpus and thus, reflect how commenters frame discourse about the burkini. It is important to note these themes are found in comments posted to all three newspapers and also, that there is considerable overlap; that is to say, any given comment may include thematic content reflecting interconnected topics, discourses, or forms of argumentation.

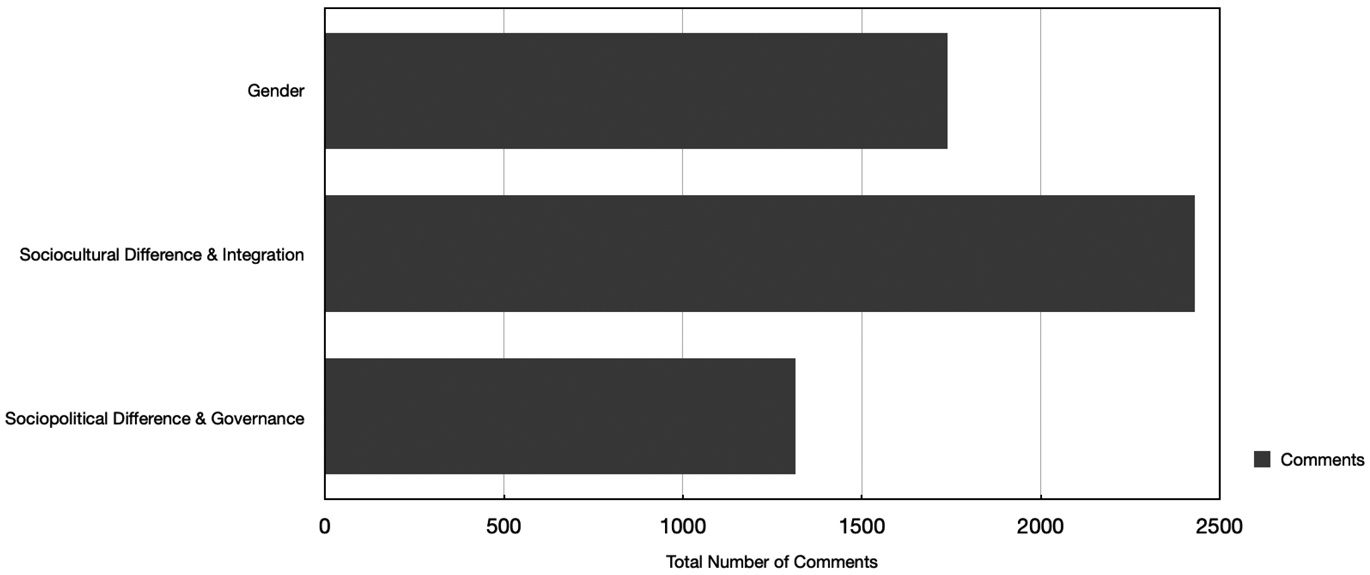

The major themes manifest in the corpus at varying frequencies. The most common major theme is sociocultural difference and integration with 68 % (2,430) of the comments framing the burkini in these terms (see Figure 1). Found in 48 % (1,740) of the comments, gender is the second most frequently utilised major theme. The least common major theme is sociopolitical difference and governance, which manifests in 36 % (1,312) of the comments.

Major themes, corpus of online user-generated comments (n=3,600).[6]

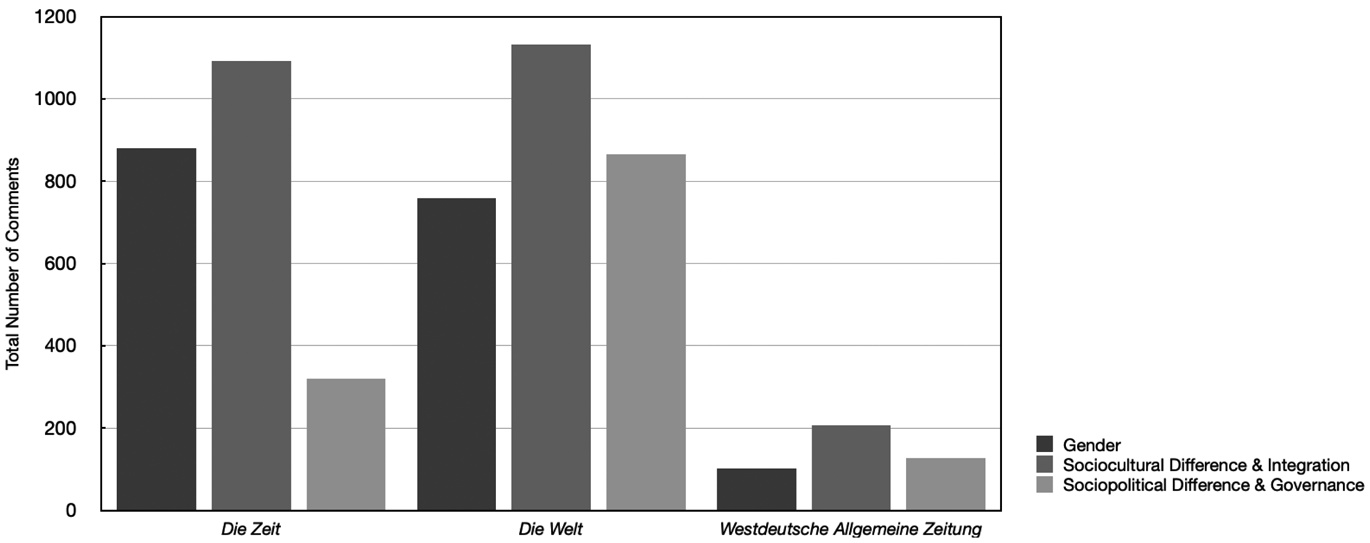

As a result, the burkini is most often discursively framed in terms of political ideologies about gender and integration. The prominence of these topics largely reflects how the burkini was presented in news articles and opinion columns. For example, in all three newspapers, politicians are quoted either confirming or questioning the role of the burkini in fostering integration and, by extension, the acceptability of the garment vis-à-vis gender equality in coeducational swimming lessons. This is evinced not only in terms of the overall number of comments about gender and integration in their associated major themes, but also per each newspaper comment section. The major theme of sociocultural difference and integration is apparent in 66 % (1,092) of the comments posted on Die Zeit, 67 % (1,132) of the comments posted on Die Welt, and 79 % (206) of the comments posted on the Westdeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung (see Figure 2). The major theme of gender is expressed in 54 % (880) of the comments posted on Die Zeit, 45 % (758) of the comments posted on Die Welt, and 39 % (102) of the comments posted on the Westdeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung.

Major themes per newspaper, corpus of online user-generated comments (n=3,600).[7]

However, differences are apparent across ideological lines. The results indicate a slightly greater focus on gender relations among Die Zeit commenters compared those posting on Die Welt, who, in comparison, are more likely to frame their commentary in terms of integration and the perceived cultural alterity of ‘Muslimness.’ Specifically, 41 % (675) of Die Zeit comments compared to 32 % (545) of Die Welt comments frame the burkini in terms of gender equality. The analysis also reveals that gender equality is invoked in tandem with discourse about sociocultural difference and integration and, combined, this accounts for 34 % (562) of Die Zeit comments and 32 % (540) of Die Welt comments. Additionally, while comments posted on both Die Zeit and Die Welt overwhelmingly frame the burkini in terms of discourse about Muslims in Germany, the latter are nearly one-and-a-half times more likely to do so do. Specifically, 60 % (1,010) of Die Welt comments frame the burkini in terms of arguments about self-isolation, integration resistance, or similar discourses problematising Muslims in Germany.

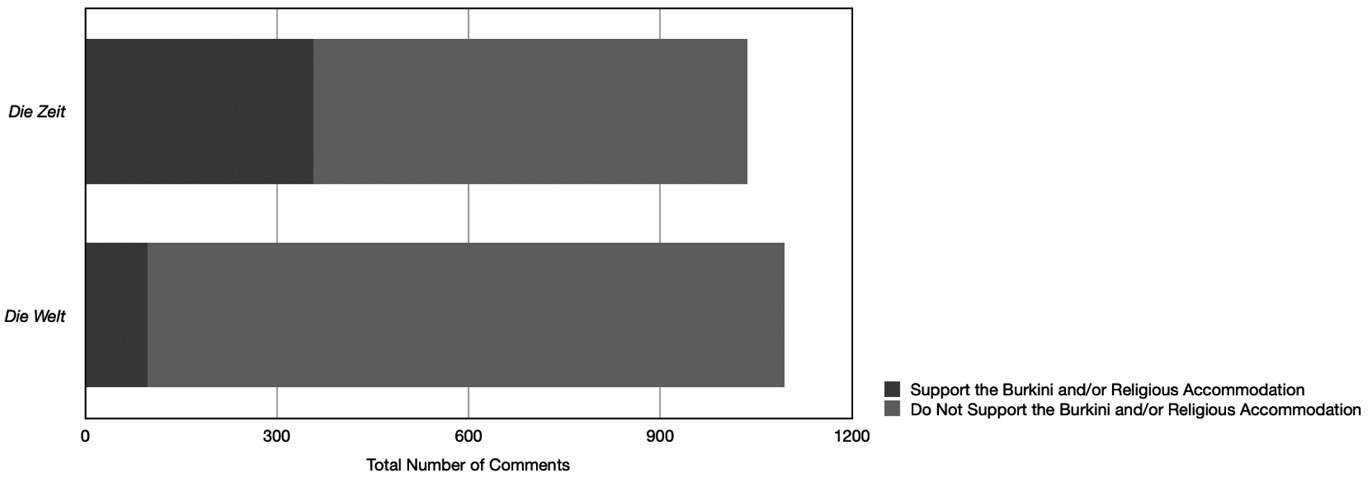

Lastly, while there are clear differences in how commenters frame discourse about the burkini suggestive of ideological variance, overall, the discourse is negative. Excluding unclear or off-topic commentary, only 22 % (357) of comments posted on Die Zeit and 6 % (97) of comments posted on Die Welt express support for the burkini and/or religious accommodation in German state-funded education (see Figure 3). In this sense, the majority of Die Zeit and Die Welt comments label such practices in exclusionary terms.

Attitude towards the burkini and/or religious accommodation per newspaper, corpus of online user-generated comments (n=3,600).

5.2 Argumentation schemes

Each of the three major themes consists of a series of sub-themes, which are framed according to argumentation schemes (see Table 2). These reflect context- and content-specific arguments through which commenters take a stance vis-à-vis a newspaper article, opinion column, or another comment in the online comment section by employing a positive, neutral, and/or negative frame. Focusing on frames related to gender and integration, the following sections review how commenters utilise these schemes with referential strategies to demarcate exclusionary boundaries of non-belonging in discourse about the burkini.

5.2.1 Major theme of gender

The major theme of gender is characterised by argumentation schemes referencing relations between men and women in German society (see Table 2). These may praise gender equality as a fundamental German liberal-democratic value (positive or neutral frame) or claim that Islam condones segregation, inequality and gendered violence (negative frame) (see Table 3). The frames often work in tandem to reinforce a binary between a German in-group, which, as Lewicki (2018: 507) notes, is assumed to conform to “liberal sexual and gender norms by default” and a Muslim out-group thought to contravene such norms.

Negative frames, major theme of gender, corpus of online user-generated comments (n=3,600).

| Major Theme | Negative Frames |

| Gender | –Arguments that negatively frame discourse related to gender equality: o claims about female access to education or societal participation o claims about the need to protect women and girls o claims linking Islam to inequality or gender-based violence |

Example (1) is representative of this type of argumentation pattern. Posted on the Westdeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung, the follow-up uses the common referential strategy of positive self- and negative other-presentation to address comments made by Franziska Giffey, Federal Minister for Family Affairs, Senior Citizens, Women, and Youth to Die Zeit regarding the Herne secondary school’s burkini program. A prominent member of the centre-left Social Democratic Party, Giffey’s statement that the program should not be interpreted as the “’Untergang des Abendlandes [downfall of the West],’” but, instead, that “’das Wichtigste ist ja das Wohl der Kinder, und das heißt nun mal, dass alle Schwimmen lernen [the most important thing is the well-being of the children, and that means that everyone learns to swim]’” were widely reported by the press (“Ministerin” 2018).

In response, the commenter critiques Giffey through use of the first-person plurals ‘we’ and ‘us’ along with the spatial deictic expression ‘here’ to index the German in-group.

(1) Wir sind hier nicht in einem arabischen Land. Nur für den Fall das sie das inzwischen vergessen hat. Unsere kulturellen Werte und Errungenschaften im 21. Jhrdt. erlauben es den Frauen so gekleidet herumzulaufen wie sie es für richtig erachten. Ob auf der Straße im Minirock oder im Schwimmbad im Bikini. Wieso sollen die Mädchen und Frauen hier auch sich benehmen wie im Mittelalter wie in den moslemisch geprägten Ländern?

We are not in an Arab country here. Just in case she [Franziska Giffey] has forgotten in the meantime. Our cultural values and achievements in the 21st century allow women to walk around dressed as they see fit. Whether on the street in a miniskirt or at the swimming pool in a bikini. Why should girls and women here also behave as they did in the Middle Ages, as in Muslim majority countries?

(Westdeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung, C230)

To emphasise this distinction, the commenter implies that perhaps Giffey had forgotten that “we are not in an Arab country here.” While the comment does not explicitly mention the burkini, reference to ‘our’ cultural values – in this case, clearly gender equality – along with the ability of women in Germany “to walk around dressed as they see fit...on the street in a miniskirt or at the swimming pool in a bikini” allude to it, especially as these garments are widely associated with female emancipation. Example (1) illustrates how gender nationalist discourse depoliticises ongoing and historic inequalities “by claiming that it is the supposedly ‘common achievementsʼ (such as gender equality) that are threatened” by the Muslim out-group (Hadj Abdou 2017: 87). This distinction is reinforced through spatial references, which imply that Muslim head and body coverings are sartorially better suited to life in an Arab or Muslim-majority country. Likewise, reference to the “Middle Ages” carries a negative connotation associated with backwardness and ignorance. For example, analyses of the influential German news magazine Der Spiegel and tabloid newspaper Bild note that pejorative references to Islam as ‘medieval,’ ‘pre-modern,’ ‘backward,’ or ‘unenlightened’ are utilised to demarcate the exclusion of Muslim practices (Becker and El-Menouar 2012; Javadian Namin 2009). As such, the commenter is implying that covering one’s body is temporally out of sync with life in modern, gender-equal Germany.

Example (2) illustrates how a Die Welt commenter replies to a comment, which, like Giffey, framed the burkini as facilitating student participation. This comment prompted debate by asking: “Was ist denn bitte schlimm an einem Burkini [What exactly is so bad about a burkini]?” (Die Welt, C803).

(2) Was ist schlimm an Burka und Ganzkörper-Verhüllung? [...] Was schlimm daran ist? Dass wir uns langsam ins Mittelalter zurückkatapultieren lassen und manche Dinge, für die Generationen von Frauen im Rahmen von Gleichberechtigung gekämpft haben, jetzt zu Gunsten von religiösen Fundamentalisten mit einem rückständigen Geschlechter-Rollen-Bild opfern.

What is so bad about burqas and full-body coverings? [...] What’s so bad about that? That we are slowly allowing ourselves to be catapulted back into the Middle Ages and are now sacrificing some things that generations of women have fought for in the context of equal rights in favour of religious fundamentalists with a backward image of gender roles.

(Die Welt, C806)

The follow-up is distinctive in its use of repetition: it repeats the initial question and utilises the same sentence construction to frame requests for female-only swimming or nude sauna days at the municipal swimming pool as problematic. Like Example (1) it relies upon positive self- and negative other-presentation by using the first-person plural ‘we’ and its reflexive form ‘ourselves’ to emphasise difference. In this example, the German in-group is temporally framed as modern and supportive of gender equality in contrast to the Muslim out-group who subscribes to a “backward image of gender roles.” Reference to the latter also restates a widely cited critique levelled by Federal Agriculture Minister Julia Klöckner, a member of the centre-right Christian Democratic Union (CDU) that the burkini program reinforced “ein Frauen diskriminierendes Rollenverständnis [a misogynistic understanding of gender roles]” (“’Das ist fatal’” 2018). The image of being “catapulted back into the Middle Ages” also rhetorically implies that to encounter inequality and the “generations of women” who fought against it, one would need to travel far into Germany’s past. In this sense, the comment reflects the recontextualisation of political speech, as well as how the news media has primed readers to associate Muslim head and body coverings with gender inequality in such a way that the garments serve as abstract symbols upon which “verschiedener Diskursstränge [various strands of discourse]” may culminate (Schiffer 2023; Wehrstein 2013: 162). This not only reinforces the non-belonging of Muslims in Germany, but also obscures that gendered forms of prejudice, discrimination, and violence remain a contemporary societal issue.

Example (3) relies upon a similar argumentation pattern, but, in this case, the follow-up is linguistically anchored to a Die Zeit opinion column through a quotation. Specifically, the commenter criticises the newspaper editor’s contention that “Freiheit wird nicht erlernt, indem man Unfreiheit verbietet [freedom is not learned by forbidding bondage]” by arguing that the burkini symbolises female oppression (Luig 2018).

(3) „Freiheit wird nicht erlernt, indem man Unfreiheit verbietet.“ / Was für eine Falschaussage! Dann führen wir doch gleich den altgriechischen Haussklaven wieder ein! Immerhin erkennt Frau Luig damit indirekt an, wofür ein Burkini (wie im Übrigen ein Kopftuch) steht: für Unfreiheit, für eine fundamentalistische, sexistische Religionsauffassung. Wie beim Kopftuch gilt auch hier: Es spielt keine Rolle, ob eine Schülerin einen Burkini „freiwillig“ trägt, sondern es kommt auf das damit vermittelte Signal an, auf die gesellschaftliche Aussage.

‘Freedom is not learned by forbidding bondage.’ / What a false statement! Then let’s reintroduce the ancient Greek house slave! At least Ms. Luig is acknowledging indirectly what a burkini (like a headscarf, by the way) stands for: bondage, a fundamentalist, sexist religious outlook. As with the headscarf, the same applies here: It doesn’t matter whether a schoolgirl wears a burkini ‘voluntarily,’ instead what matters is the signal it sends out, the social message.

(Die Zeit, C1262)

Invoking inflammatory imagery, the commenter references slavery in ancient Greece to imply that wearing a headscarf or burkini is temporally and spatially out of alignment with the liberal-democratic values that characterise modern Germany. As with Example (1) and Example (2), the first-person plural is employed to differentiate the German in-group from the Muslim out-group in order to demarcate and exclude what the commenter portrays as “a fundamentalist, sexist religious outlook.” Strategic use of the adverb ‘voluntarily’ in scare quotes in reference to Muslim body-coverings also denotes doubt regarding the ability of Muslim women to act according to their own free will. Shooman (2014: 86) writes that Islam-related coverage in the German news media suggests “dass patriarchale Strukturen ein Alleinstellungsmerkmal des Islams wären [that patriarchal structures are a unique feature of Islam]” rather than a larger societal problem. Similarly, Yildiz (2009) shows how the image of the veiled, powerless Muslim woman in Germany was constructed by Der Spiegel as an object onto which anxiety about terrorism and societal change could be projected. Thus, by employing the gender nationalist trope of the oppressed Muslim woman, the commenter not only negatively frames Muslim body-coverings as deleterious, but also implies that Muslim women and girls need to be protected.

5.2.2 Major theme of sociocultural difference and integration

The major theme of sociocultural difference and integration is characterised by argumentation schemes that reference Europe and Germany in terms of societal norms and values, sociocultural difference, and concerns related to Muslim sociocultural practices (see Table 2). The latter relies upon negative framing related to the perceived incompatibility of ‘Muslimness’ or behaviour associated with Muslims (see Table 4). It may also manifest in discourse about ‘tolerance,’ especially claims of ‘false tolerance’ or tolerating otherwise problematic behaviour.

Negative frames, major theme of sociocultural difference and integration, corpus of online user-generated comments (n=3,600).

| Major Theme | Negative Frames |

| Sociocultural Difference and Integration | –Arguments that negatively frame discourse related to sociocultural difference and integration: o claims that Muslims self-isolate and create ‘parallel societies’ (Parallelgesellschaften) o claims that Muslims reject German norms and values and/or refuse to integrate o claims that Muslims demand special treatment o claims that Muslims exhibit foreign allegiance o claims that Muslims cause societal disintegration or demographic change o claims of ‘false tolerance’ (falschen Toleranz) |

Example (4) addresses diversity and religious accommodations within state-funded schools. It was posted in response to a Westdeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung news article, which reported Muzaffer Oruc, Chair of the Herne Integration Council as stating that, “wenn junge Frauen aus Glaubensgründen nicht mit Männern schwimmen wollen [if young women do not want to swim with men for religious reasons]” then schools should act in a “kultursensibel [culturally sensitive]” manner, because “wenn die Schüler fern bleiben, ist das auch keine Integration [if students stay away, that’s not integration either]” (Poll 2018).

(4) Was die s. g. Kultursensibilität der Schulen angeht, so kann damit innerhalb unserer Grenzen doch nur die deutsche Kultur gemeint sein!?

As far as the so-called cultural sensitivity of schools is concerned, within our borders this can only refer to German culture, can it not!?

(Westdeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung, C458)

While Oruc advocates for an inclusive school environment, the commenter questions the appropriateness of “so-called cultural sensitivity” in schools. This statement along with use of the first-person plural in the phrase “within our borders” and reference to “German culture” represents culture as a discreetly bound entity fixed according to essentialised, sociocultural attributes. As such, it implies that schools should not provide ‘culturally sensitive’ religious accommodations like the burkini or gender-separate swimming lessons for Muslim students. This aligns with research conducted on the German press (Ehrkamp 2010) and public policy documents (Andreassen and Lettinga 2012; Gresch et al. 2012), which indicate that Muslim body-coverings are framed as a sign of the wearer’s cultural alterity and un-belonging while the removal of these garments marks belonging and inclusion in the national body politic.

Written in response to a Die Zeit editorial, Example (5) is indicative of framing that indexes Muslim non-belonging. It metaphorically invokes Greek mythology by comparing Muslims in Germany to a ‘Trojan horse,’ as well as philosophical conceptualisations of toleration, especially characterisations of specific groups as intolerant.

(5) Burka, Schleier und so weiter sind nicht Ausdruck einer aufgeklärten Gesellschaft, sondern Ausdruck von Unfreiheit, von Reaktionismus ein Zeichen gegen Demokratie! Wir laden uns hier als freie und demokratische Gesellschaft eine Bürde auf, ein trojanisches Pferd, dessen Bedeutung wir nicht begreifen und wir wollen uns das Problem vom Hals halten, indem wir es einfach zu einer Frage der Toleranz erklären.

Burkas, veils and so on are not expressions of an enlightened society, but expressions of a lack of freedom, of reactionism, a symbol against democracy! As a free and democratic society, we are taking on a burden, a Trojan horse whose significance we do not understand, and we want to rid ourselves of the problem by simply declaring it a matter of tolerance.

(Die Zeit, C2982)

The comment marks a Muslim out-group in opposition to the German in-group through negation. By framing Muslim head and body coverings, in particular, as unenlightened, undemocratic, and representative of a lack of freedom, the commenter sets up a dichotomy between two mutually exclusive and contradictory ways of being. Thus, veiling is framed as a “burden” and a “problem” that the German in-group – which is marked through the first-person plural ‘we’ and its reflexive form ‘ourselves’ – must not tolerate.

The argumentation scheme in Example (5) relies up the essentialisation of perceived differences coupled with a dichotomous characterisation of Muslim body-coverings as a “symbol against democracy” and Germany as a “free and democratic society.” This reflects the German news media’s framing of Islam as “politisch und dies nicht mit dem westlichen Wertesystem sowie dem Demokratieverständnis zu vereinbaren [politically incompatible with the Western value system and understanding of democracy]” (Kalwa 2013: 161). Likewise, it echoes speech by prominent politicians – including ‘codebreakers’ cited by the German news media as ‘authentic’ representatives of the Muslim community – who claim that Islam is undemocratic and Muslim body-coverings signify subjugation (Korteweg and Yurdakul 2021). In this sense, the comment also exemplifies what Shooman (2014: 63) describes as “dem Dreischritt Essentialisierung, Dichotomisierung und Hierarchisierung [the three-step process of cultural essentialism, dichotomisation and hierarchisation]” that characterises anti-Muslim racism in Germany. Notably, the comment’s polemical tone not only intends to frame Islam as incongruous with the German political system or in some way less acceptable, but also implies that as a ‘Trojan horse’ the presence of Muslims in Germany is somehow equivalent to an invasion by a foreign army and, thus, a threat to the body politic. A widely cited trope in European news media (Poole 2018) and political speech (Bracke and Hernández Aguilar 2020, 2021), such discursive framings are none the less dangerous (Verschueren 2022) and highly inflammatory in their problematisation of Muslims.

Posted on Die Welt, Example (6) is notable in that it suppresses the primary agent and does not use personal pronouns as part of a referential strategy to demarcate non-belonging.

(6) Da wird im vorauseilenden Gehorsam und falsch verstandener Toleranz eine Extrawurst für Islamisten gebraten. So funktioniert keine Integration und die Spaltung der Gesellschaft wird vorangetrieben.

In a rush to be obedient and out of a misguided sense of tolerance, Islamists are being given special treatment. This is not how integration works, and it only serves to drive a wedge between members of society.

(Die Welt, C1445)

Instead, the sentence structure shifts the attention away from the agent onto the result of the agent’s action in order to emphasise that “Islamists” are unfairly benefiting from “special treatment” due to “a misguided sense of tolerance.” German news outlets like Der Spiegel and Bild primarily use the term ‘Islamist’ in the context of extremism (Javadian Namin 2009) and thus its use in discourse about the Herne secondary school’s burkini program is striking.

On the other hand, reference to “a misguided sense of tolerance” recontexualises political statements widely quoted in the news media in terms of integration. Specifically, NRW Secretary for Integration Serap Güler (CDU) said the burkini program was “fatal vor allem aus emanzipatorischer Sicht...ich halte dies für das absolut falsche Signal und für völlig falsch verstandene Toleranz [fatal, especially from an emancipatory perspective...I think this sends absolutely the wrong signal and is a complete misguided sense of tolerance]” (“’Das ist fatal’” 2018). Klöckner also used emotive language arguing that, “wir sollten den Mädchen und jungen Frauen nicht aus falsch verstandener Toleranz in den Rücken fallen, das ist keine Toleranz, das ist vielmehr eine verhängnisvolle Ignoranz [we should not stab girls and young women in the back out of a misguided sense of tolerance, that is not tolerance, it is rather a fatal ignorance]” (“’Das ist fatal’” 2018). While both politicians direct their criticism in terms of gender equality, namely Güler’s focus on emancipation and Klöckner’s emphasis on protecting women, in Example (6) the commenter recontextualises their words in terms of integration. Namely, by arguing that this “is not how integration works” focus is placed on the need to stop tolerating what the commenter perceives to be intolerable behaviour, as well as the need for greater conformity or a willingness to integrate. However, as Fuller (2019: 335) contends, behaviour associated with Muslims is often marked as a sign of unintegration and, as a result, it is nearly “impossible for Muslims to fulfill the criteria for being German.”

6 Discussion and conclusion

Guided by the politics of belonging, gender nationalism, and the argument that non-belonging is ascribed through boundary formations in the news media, this article shows how political ideologies about gender and integration are reflected and recontextualised in discourse about the burkini. Focusing on a corpus of online user-generated newspaper comments compiled from the online edition of German regional and national newspapers, it follows a two-fold analytical approach. Examining thematic patterns within the corpus, the qualitative content analysis indicates that the burkini is characterised according to the major themes of gender, sociocultural difference and integration, and sociopolitical difference and governance. Further substantiating these findings, the critical discourse studies-based analysis reveals that commenters utilise argumentation schemes about gender relations, European and German societal norms and values, sociocultural difference, and concerns related to Muslim sociocultural practices to frame the burkini in terms of gender and integration. In addition, the analysis shows that commenters combine positive, neutral, and/or negative frames with referential strategies with ideological effects. Examples of this include the use of positive self- and negative other-presentation and the strategic use of pronouns to align or distance the commenter from specific claims, which, discursively, also allow for exclusionary boundaries of non-belonging to be drawn.

On the subject of gender and integration, these findings need to be contextualised. Notably, although commenters draw upon ideologies about gender and integration separately, roughly a third of all Die Zeit and Die Welt comments specifically reference gender equality in terms of sociocultural difference and integration. This is significant as it points towards the salience and normalisation of gender nationalist rhetoric in everyday digital discourse, as well as the role of the news media in priming the public to associate veiling with ‘foreignness’ (Schiffer 2023). Gender equality is not referenced as a liberal-democratic value in its own right in these comments, but, rather, as Hadj Abdou (2017: 87) notes, instrumentalised as “part of a nationalist repertoire of exclusion.” By drawing upon gender nationalism to symbolically define “who belongs and who does not” in what Sauer (2016: 118) argues is a new, gendered politics of belonging centred on Muslim body-coverings, the commentary also reflects a changing understanding of ‘Germanness.’ Specifically, Rostock and Berghahn (2008: 358) contend that following the introduction of jus soli citizenship procedures in 2000, gender equality became “a useful tool to secure the image of German society as modern and emancipated” in contrast to the Muslim ‘other.’

Also, across ideological lines, differences are apparent with Die Zeit commenters slightly more likely to focus on gender relations while comments posted on Die Welt are nearly one-and-a-half times more likely to emphasis and problematise ‘Muslimness.’ This indicates that while gender equality is a key means of framing the burkini in the analysed commentary, it is also utilised as part of what El-Tayeb (2011: xxvi) describes as a “shared iconography” in which race is implicitly rather than explicitly referenced – for example, by framing specific behaviours as evidence of insurmountable sociocultural or religious differences – to denote un-belonging. Lewicki and Shooman (2020) argue that anti-Muslim racism is a key component of German nation-building, which gains legitimacy, in part, through what Farris (2017: 3) terms “a new, unholy alliance” that unites right-wing nationalists, feminists, and neoliberals in invoking gender equality to advance their own political objectives. To this point, the populist and ethnonationalist far-right party, the Alternative for Germany portrayed imagery of women in bikinis in campaign posters and videos in 2017 to contrast German ‘liberality’ with the ‘illiberality’ of Muslims (Yurdakul, et al. 2019). And while such discourse could lead Die Welt’s presumably more conservative readership to frame the burkini in similar terms, focusing on gender in combination with perceived sociocultural difference also serves a larger societal function. Specifically, Lewicki and Shooman (2020: 40) claim that racialised body politics combine with gender nationalism to redirect former East German grievances and solidify the collective German self-image of ‘who we are not’ and ‘what we don’t do’ that “not only masks, but also re-creates and reinforces hierarchical binaries” between groups. Consequently, as part of a ‘politics of fear,’ in which veiled Muslim women symbolise the ultimate societal ‘other’ or provocatively the “enemy within” (Baldi 2021; Lewicki and Shooman 2020: 32; Wodak 2021), it is not surprising that the analysis, despite evidence of some ideological variance, indicates that the majority of Die Zeit and Die Welt commentary is exclusionary in nature and against allowing the burkini and/or other forms of religious accommodation in German state-funded education.

Additional research is needed to test these conclusions against linguistic corpora that reflect discourse about other forms of Muslim body-coverings, such as ongoing public debates about face-veils in state-funded schools in the German news media. Also, while literature has examined related public policy and political discourse, particularly regarding the far-right, more analysis is needed to indicate how gender nationalist discourse has begun to shift from a focus on integration to exclusion.

References

Ahmed, Saifuddin & Jörg Matthes. 2017. Media representation of Muslims and Islam from 2000 to 2015: A meta-analysis. International Communication Gazette. 79(3): 219–244. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048516656305. 10.1177/1748048516656305Search in Google Scholar

Andreassen, Rikke & Doutje Lettinga. 2012. Veiled debates: Gender and gender equality in European national narratives. In Sieglinde Rosenberger & Birgit Sauer (eds.), Politics, Religion and Gender: Framing and Regulating the Veil, 17–36. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203181058. 10.4324/9780203181058-3Search in Google Scholar

Baldi, Giorgia. 2021. Un-veiling Dichotomies: European Secularism and Women’s Veiling, Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-79297-8. 10.1007/978-3-030-79297-8Search in Google Scholar

Becker, Melanie & Yasemin El-Menouar. 2012. Is Islam an obstacle for integration? A qualitative analysis of German media discourse. Journal of Religion in Europe. 5(2): 141–61. https://doi.org/10.1163/187489212X639172.10.1163/187489212X639172Search in Google Scholar

Berlin, Lawrence N., Elda Weizman & Anita Fetzer. 2015. Introduction. In Anita Fetzer, Elda Weizman & Lawrence N. Berlin (eds.), The Dynamics of Political Discourse: Forms and Functions of Follow-ups, 1–14. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/pbns.259.001int.10.1075/pbns.259.001intSearch in Google Scholar

Bernard, H. Russell. 2006. Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. 4th edn. Oxford: AltaMira Press.Search in Google Scholar

Bingham, Andrea J. 2023. From data management to actionable findings: A five-phase process of qualitative data analysis. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. 22. 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069231183620.10.1177/16094069231183620Search in Google Scholar

Bolsmann, Tobias, Matthias Korfmann & Kathrin Meinke. 2018. “Herner Schulleiter – ‘Wir wollen Teilhabe ermöglichen’ [Principal in Herne – ‘We want to enable participation’].” Westdeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung, 12 June. Available online: https://www.waz.de/staedte/herne-wanne-eickel/article214561683/burkini-kauf-des-pestalozzi-gymnasiums-sorgt-fuer-aufsehen.html (accessed 31 October 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Bracke, Sarah & Luis Manuel Hernández Aguilar. 2020. ‘They love death as we love life’: The ‘Muslim question’ and the biopolitics of replacement. British Journal of Sociology 71: 680–701. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12742. 10.1111/1468-4446.12742Search in Google Scholar

Bracke, Sarah & Luis Manuel Hernández Aguilar. 2021. Thinking Europe’s ‘Muslim question’: On Trojan horses and the problematization of Muslims. Critical Research on Religion. 10(2): 200–220. https://doi.org/10.1177/20503032211044430. 10.1177/20503032211044430Search in Google Scholar

Creswell, John W. 2013. Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. 3rd edn. London: SAGE.Search in Google Scholar

Dahinden, Janine & Stefan Manser-Egli. 2023. Gendernativism and liberal subjecthood: The cases of forced marriage and the burqa ban in Switzerland. Social Politics 30(1): 140–163. https://doi.org/10.1093/sp/jxab053.10.1093/sp/jxab053Search in Google Scholar

“‘Das ist fatal’ – Reaktionen auf Burkinis an Herner Schule [‘That’s fatal’ - Reactions to burkinis at a school in Herne].” 2018. Westdeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung, 12 June. Available online: https://www.waz.de/staedte/herne-wanne-eickel/article214557885/heftige-reaktionen-auf-burkini-angebot-an-herner-schule.html (accessed 31 October 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Davis, Emily E. 2023. The burkini in German legal discourse: Individualised integration, belonging, and the role of the state. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. 49(11). 2627–2647. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2023.2199139.10.1080/1369183X.2023.2199139Search in Google Scholar

Davis, Emily E. 2025. Muslim women as the ‘other’ in German political cartoons. In Charlotte Taylor, Simon Goodman, & Stuart Dunmore (eds.), Discursive Construction of Migrant Identities, 203–228. London: Bloomsbury. http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781350442900.0015.10.5040/9781350442900.0015Search in Google Scholar

Dorostkar, Niku & Alexander Preisinger. 2017. ‘Cyber hate’ vs. ‘cyber deliberation’: The case of an Austrian newspaper’s discussion board from a critical online-discourse analytical perspective. Journal of Language and Politics. 16(6): 759–781. https://doi.org/10.1075/jlp.15033.dor. 10.1075/jlp.15033.dorSearch in Google Scholar

Ehrkamp, Patricia. 2010. The limits of multicultural tolerance? Liberal democracy and media portrayals of Muslim migrant women in Germany. Space and Polity. 14(1): 13–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562571003737718. 10.1080/13562571003737718Search in Google Scholar

El-Tayeb, Fatima. 2011. European Others: Queering Ethnicity in Postnational Europe. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. https://doi.org/10.5749/minnesota/9780816670154.001.0001. 10.5749/minnesota/9780816670154.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Fairclough, Norman & Ruth Wodak. 1997. Critical discourse analysis. In Teun A. van Dyk (ed.), Discourse as Social Interaction, 258–284. London: SAGE.Search in Google Scholar

Farris, Sara R. 2017. In the Name of Women’s Rights: The Rise of Femonationalism. Durham: Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822372929.10.1215/9780822372929Search in Google Scholar

Fuller, Janet M. 2019. Discourses of immigration and integration in German newspaper comments. In Lorella Viola & Andreas Musolff (eds.), Migration and Media: Discourses about Identities in Crisis, 317–338. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/dapsac.81.14ful. 10.1075/dapsac.81.14fulSearch in Google Scholar

Giltrow, Janet. 2013. Genre and computer-mediated communication. In Susan C. Herring, Dieter Stein & Tuija Virtanen (eds.), Pragmatics of Computer-Mediated Communication (Handbooks of Pragmatics, 9), 717–737. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9783110214468.717Search in Google Scholar

Gresch, Nora, Petra Rostock & Sevgi Kılıç. 2012. Negotiating belonging: Or how a differentiated citizenship is legitimized in European headscarf debates. In Sieglinde Rosenberger & Birgit Sauer (eds.), Politics, Religion and Gender: Framing and Regulating the Veil, 55–73. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203181058. 10.4324/9780203181058-5Search in Google Scholar

Hadj Abdou, Leila. 2017. ‘Gender nationalism’: The New (Old) Politics of Belonging. Österreichische Zeitschrift für Politikwissenschaft. 46(1). 83–8. https://doi.org/10.15203/ozp.1592.vol46iss1.10.15203/ozp.1592.vol46iss1Search in Google Scholar

Javadian Namin, Parisa. 2009. Die Darstellung des Islam in den deutschen Printmedien am Beispiel von Spiegel und Bild [The portrayal of Islam in the German print media using the example of Spiegel and Bild]. In Rainer Geißler and Horst Pöttker (eds.), Massenmedien und die Integration ethnischer Minderheiten in Deutschland [Mass Media and the Integration of Ethnic Minorities in Germany], 271–296. Bielefeld: Transcript. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783839410271-010.10.1515/9783839410271-010Search in Google Scholar

Johansson, Marjut. 2015. Bravo for this editorial! Users’ comments in discussion forums. In Elda Weizman & Anita Fetzer (eds.), Follow-ups in Political Discourse: Explorations Across Contexts and Discourse Domains, 83–107. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/dapsac.60.04joh. 10.1075/dapsac.60.04johSearch in Google Scholar

Johansson, Marjut. 2017. Everyday opinions in news discussion forums: Public vernacular discourse. Discourse, Context & Media. 19. 5–12. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.dcm.2017.03.001.10.1016/j.dcm.2017.03.001Search in Google Scholar

Kalwa, Nina. 2013. Das Konzept »Islam«: Eine diskurslinguistische Untersuchung [The Concept of ‘Islam’: A Discourse-linguistic Investigation]. Berlin: De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/zrs-2015-0010.10.1515/9783110309973Search in Google Scholar

Kelle, Birgit. 2018. “Die Prinzipienlosigkeit der Burkini-Befürworter [The unprincipledness of burkini advocates],” Die Welt, 27 June. Available online: https://www.welt.de/debatte/kommentare/plus178286762/Birgit-Kelle-Die-Prinzipienlosigkeit-der-Burkini-Befuerworter.html (accessed 31 October 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Klöckner, Julia. (@juliakloeckner) 2018. “Über den Vorstoß.” Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/juliakloeckner/posts/über-den-vorstoß-schwimmburkinis-an-einem-herner-gymnasium-anzuschaffen-bin-ich-/1946454125412156/ (last modified 12 June 2018).Search in Google Scholar

Korteweg, Anna & Gökce Yurdakul. 2014. The Headscarf Debates: Conflicts of National Belonging. Stanford: Stanford University Press.10.1515/9780804791168Search in Google Scholar

Korteweg, Anna & Gökce Yurdakul. 2021. Liberal feminism and postcolonial difference: Debating headscarves in France, the Netherlands, and Germany. Social Compass 68(3): 410–429. https://doi.org/10.1177/0037768620974268. 10.1177/0037768620974268Search in Google Scholar

Korteweg, Anna & Gökce Yurdakul. 2024. Non-belonging: Borders, boundaries, and bodies at the interface of migration and citizenship studies. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 50(2): 293–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2024.2289704. 10.1080/1369183X.2024.2289704Search in Google Scholar

Krzyżanowski, Michel. 2009. Europe in crisis? Discourses on crisis events in the European press 1956–2006. Journalism Studies. 10(1): 18–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616700802560468.10.1080/14616700802560468Search in Google Scholar

Krzyżanowski, Michel. 2010. The Discursive Construction of European Identities: A Multi-Level Approach to Discourse and Identity in the Transforming European Union. Frankfurt: Peter Lang.Search in Google Scholar

Krzyżanowski, Michel & Krzyżanowska, Natalia. 2024. Conceptual Flipsiding in/and Illiberal Imagination: Towards a Discourse-Conceptual Analysis. The Journal of Illiberalism Studies. 4(2): 33–46. https://doi.org/10.53483/XCPU3574.10.53483/XCPU3574Search in Google Scholar

Kultusministerkonferenz [KMK]. 2017. Basic Structure of the Education System in the Federal Republic of Germany: Diagram. Berlin: Secretariat of the Standing Conference of the Ministers of Education and Cultural Affairs of the Länder in the Federal Republic of Germany. Search in Google Scholar

Leeuwen, Theo van. 2008. Discourse and Practice: New Tools for Critical Analysis. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195323306.001.0001. 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195323306.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Lewicki, Aleksandra. 2018. Race, Islamophobia and the politics of citizenship in post-unification Germany. Patterns of Prejudice, 52(5): 496–512. https://doi.org/10.1080/0031322X.2018.1502236. 10.1080/0031322X.2018.1502236Search in Google Scholar

Lewicki, Aleksandra & Yasemin Shooman. 2020. Building a new nation: Anti-Muslim racism in post-reunification Germany. Journal of Contemporary European Studies 28(1): 30–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/14782804.2019.1647515. 10.1080/14782804.2019.1647515Search in Google Scholar

Luig, Judith. 2018. “Burkinis für alle! [Burkinis for everyone!]” Die Zeit, 26 June. Available online: https://www.zeit.de/gesellschaft/zeitgeschehen/2018-06/schwimmunterricht-schule-burkinis-selbstbewusstsein (accessed 31 October 2024). Search in Google Scholar

“Ministerin spricht sich für Burkinis im Schwimmunterricht aus [Minister speaks out in favour of burkinis in swimming lessons].” 2018. Westdeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung, 25 June. Available online: https://www.waz.de/politik/article214679881/ministerin-spricht-sich-fuer-burkinis-im-schwimmunterricht-aus.html. (accessed 31 October 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Musolff, Andreas. 2019. “They have lived in our street for six years now and still don’t speak a work [!] of English”: Scenarios of alleged linguistic underperformance as part of anti-immigrant discourses. In Lorella Viola & Andreas Musolff (eds.), Migration and Media: Discourses about Identities in Crisis, 339–354. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/dapsac.81.15mus. 10.1075/dapsac.81.15musSearch in Google Scholar

Naab, Teresa K. & Annika Sehl. 2017. Studies of user-generated content: A systematic review. Journalism. 18(10). 1256–1273. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884916673557.10.1177/1464884916673557Search in Google Scholar

Niewerth, Gerd. 2018 a. “Das Gerangel um die Kleiderordnung in Essener Bädern [The tussle over the dress code in Essen’s pools],” Westdeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung, 24 August. Available online: https://www.waz.de/staedte/essen/article12128750/das-gerangel-um-die-kleiderordnung-in-essener-baedern.html (accessed 31 October 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Niewerth, Gerd. 2018 b. “Schwimmen in Leggins? – Debatte um Badekleidung von Muslimas [Swimming in leggings? – Debate about swimwear for Muslims],” Westdeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung, 2 August. Available online: https://www.waz.de/staedte/essen/article214989617/streit-um-badekleidung-muslimischer-frauen-polarisiert.html (accessed 31 October 2024). Search in Google Scholar

Pfündel, Katrin, Anja Stichs & Kerstin Tanis. 2021. Muslimisches Leben in Deutschland 2020: Studie im Auftrag der Deutschen Islam Konferenz [Muslim life in Germany 2020: Study commissioned by the German Islam Conference]. Report 38, Research Centre of the Federal Office. Nuremberg: Federal Office for Migration and Refugees. Search in Google Scholar

Poll, Karoline. 2018. “Gymnasium hat Burkinis für Schwimmunterricht angeschafft [Secondary school has purchased burkinis for swimming lessons],” Westdeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung, 12 June. Available online: https://www.waz.de/staedte/herne-wanne-eickel/article214549509/herner-gymnasium-schafft-burkinis-fuer-schwimmunterricht-an.html (accessed 31 October 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Poole, Elisabeth. 2018. Constructing ‘British values’ within a radicalisation narrative: The reporting of the Trojan horse affair. Journalism Studies 19(3): 376–391. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2016.1190664. 10.1080/1461670X.2016.1190664Search in Google Scholar

Reisigl, Martin & Ruth Wodak. 2001. Discourse and Discrimination: Rhetorics of Racism and Antisemitism. New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203993712. 10.4324/9780203993712Search in Google Scholar

Richter, Carola & Sünje Paasch-Colberg. 2023. Media representations of Islam in Germany. A comparative content analysis of German newspapers over time. Social Sciences and Humanities Open 8(1): 100619. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssaho.2023.100619. 10.1016/j.ssaho.2023.100619Search in Google Scholar

Rosenberger, Sieglinde & Birgit Sauer (eds). 2012. Politics, Religion and Gender: Framing and Regulating the Veil. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203181058.10.4324/9780203181058Search in Google Scholar

Rostock, Petra & Sabine Berghahn. 2008. The ambivalent role of gender in redefining the German nation. Ethnicities 8(3): 345–364. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468796808092447.10.1177/1468796808092447Search in Google Scholar

Ruiz, Carlos, David Domingo, Josep Lluís Micó, Javier Díaz-Noci, Koldo Meso & Pere Masip. 2011. Public sphere 2.0? The democratic qualities of citizen debates in online newspapers. The International Journal of Press/Politics. 16(4). 463–487. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161211415849. 10.1177/1940161211415849Search in Google Scholar

Ryan, Gery W. & H. Russell Bernard. 2003. Techniques to Identify Themes. Field Methods. 15(1): 85–109. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X02239569. 10.1177/1525822X02239569Search in Google Scholar

Saldaña, Johnny. 2013. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. London: SAGE.Search in Google Scholar

Sauer, Birgit. 2016. Gender and Citizenship: Governing Muslim Body Covering in Europe. In Lena Gemzöe, Marja-Liisa Keinänen & Avril Maddrell (eds.), Contemporary Encounters in Gender and Religion: European Perspectives, 105–29, Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-42598-6.10.1007/978-3-319-42598-6Search in Google Scholar

Schiffer, Sabine. 2023. Framing, Priming und Politik [Framing, priming and politics]. In Anna Sabel & Natalia Amina Loinaz (eds.), (K)ein Kopftuchbuch [(Not) a book about headscarves], 17–28. Bielefeld: Transcript. https://doi.org/10.14361/9783839465073-002. 10.1515/9783839465073-002Search in Google Scholar

Schmidt, Sabrina. 2022. Grauzonen des Alltagsrassismus: Zum kommunikativen Umgang mit antimuslimischem »Wissen« [Gray areas of everyday racism: On dealing communicatively with anti-Muslim ‘knowledge’]. Bielefeld: Transcript. http://doi.org/10.14361/9783839460535.10.1515/9783839460535Search in Google Scholar

Shooman, Yasemin. 2014. ‘... weil ihre Kultur so ist’: Narrative des antimuslimischen Rassismus [‘... Because their culture is like that’: Narratives of anti-Muslim racism]. Bielefeld: Transcript. https://doi.org/10.1515/transcript.9783839428665.10.14361/transcript.9783839428665Search in Google Scholar

Taylor, Adam. 2016. “The surprising Australian origin story of the ‘burkini.’” Washington Post, 17 August. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2016/08/17/the-surprising-australian-origin-story-of-the-burkini/ (accessed 31 October 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Verschueren, Jef. 2022. Complicity in discourse and practice. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781003206354Search in Google Scholar

Wehrstein, Daniela. 2013. Deutsche und französische Pressetexte zum Thema ‚Islam’: Die Wirkungsmacht impliziter Argumentationsmuster [German and French Press on the Subject of ‘Islam’: The Effect of Implicit Argumentation Patterns]. Berlin: De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110307757. 10.1515/9783110307757Search in Google Scholar