Abstract

A new functional pH-responsive polyurethane-based nanomicelle has been developed with BES-Na as the functional monomer, the buffering agent with tertiary amine, and sulfonic acid group was incorporated into the hydrophilic shell as the functional agent, which resulted in polyurethane nanosystem with pH-sensitive property. Folic acid (FA) was chosen as model hydrophobic drug to evaluate the loading and pH-triggered release of the PU micelles in vitro drug loading and release. The drug loading content (LC) and the encapsulation efficiency (EE) for FA-loaded micelles in phosphate-buffered solutions were 7.68% and 27.72%, respectively, and the largest accumulative drug release percentages in pH 6.8 and pH 5.0 were 79.17% and 89.83% in 24 h, respectively. A facile and versatile approach has been provided for the design and fabrication of smart nanovehicles for effective drug delivery and opens a new thought in the design and fabrication of biodegradable polyurethanes for next generation of nanomicellar systems.

1 Introduction

Great strides have been made in the development of stimuli-responsive nanocarriers systems (1), (2) based on block amphiphilic copolymers (3), (4), (5) for drug and gene delivery, which become an important part of biological delivery system materials as personalized medicine systems, over the past decades (6), (7). The nanomicelles show improved drug solubility, reduced cytotoxicity and prolonged circulation time in an aqueous medium within solid tumors and provide a solution for the side effects of antibiotics and anticancers, such as poor solubility, serious side effects and low absorption. The enhanced permeability effect (EPR) effect (8) was first put forward by Matsumura and Maeda in 1986 and has been observed in many experimental and human solid tumors in more researches, which has thus become the “gold standard” in nanomicelles design of suitable drug delivery system of appropriate size, moderated charge and stable structure (9), (10). The nanomicelles accumulate passively on the target location (solid tumor) by EPR and respond simultaneously to the environmental stimuli of tumor, such as pH (11), (12), redox (13), (14), temperature (15), enzyme (16), (17) and multiple responsiveness (18), then release the loading drugs (19), (20).

Polyurethanes, which have been well established as a large family of synthetic materials used for a versatile range of biomedical applications, have been extensively applied in controlled drug delivery (21), tissue engineering (22), wearable E-skin (23) and shape memory biomaterials (24) and widely used in many applications. It is owing to their comprehensive biocompatibility and biodegradability, excellent physical properties and hypocytotoxicity (25). In addition to this, some important factors may enable the incorporation of different functional moieties, such as the mild fabrication process and the high variable chemistry maneuverability of polyurethanes, and introduce stimuli responsiveness, functional group and internalized ligands into the polymer structure, thus generating nanobiomaterials exhibiting diverse biophysical chemistry properties. In recent years, functional polyurethanes especially stimuli-sensitive polyurethanes have been suitable as the appealing candidates for intracellular-triggered drug release (26), (27).

Herein, a zwitterionic polymer (BPU)-based polyurethane, bearing tertiary amine group and sulfonate group providing appropriate surface charge and pH responsiveness, showed that poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG, Mn=800) was proposed as “stealth” (28) hydrophilic chain to increase the cell internalization of polymer micelles for efficient drug delivery and poly(neopentyl glycol adipate) diol (PNA-2000, Mn=2000) was used as hydrophobic chain curled into a nucleus for drug enveloped. We chose folic acid (FA) as mode drug to evaluate the loading and pH-triggered releasing profile of the BPU nanomicelle. The FA-loaded BPU nanomicelles had an average particle size of about 100 nm, which exhibited stable existence in phosphate-buffered solution (PBS). The drug loading content (LC) and the encapsulation efficiency (EE) for FA-loaded micelles in PBS were 7.68% and 27.72%, respectively, and the largest accumulative drug release percentages in pH 6.8 and pH 7.4 were 79.17% and 89.83% in 24 h, respectively.

2 Experimental

2.1 Materials

Isophorone diisocyanate (IPDI), 2-[N, N-bis (2-hydroxyethyl)] aminoethanesulfonic acid sodium salt (BES-Na), dibutyltin dilaurate (DBTDL), 1,4-butanediol (BDO), 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate (HEMA) and calcium hydride(CaH2) were purchased from Aladdin Industrial Corporation (Shanghai), China. Polyethylene glycol (PEG) (Mn=800) was purchased from Guangfu Fine Chemical Research Institute (Tianjin), China. Poly(neopentyl glycol adipate) diol (PNA-2000, Mn=2000) was purchased from Xinyutian Chemical (Qingdao) Co. Ltd., China. BES-Na, BDO, PEG (800) and PNA-2000 were dehydrated under reduced pressure at 120°C for 2–3 h before use. 1-Methyl-2-pyrrolidinone [NMP, Fuchen chemical reagent factory (Tianjin), China] was dried over CaH2 and vacuum distilled before use. N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF) was purchased from Tianjin kemio chemical reagent co. LTD. (Tianjin), China. FA was obtained from Solaibao Technology (Beijing) Co. Ltd., China.

2.2 Synthesis of the polyurethanes

Polyurethanes were synthesized from IPDI, PNA-2000, PEG (800), BDO, HEMA and BES-Na; the feed ratios of the monomers are listed in Table 1 and Figure 1. First, BES-Na was copolymerized with the first part of IPDI at 75°C for 1 h in the presence of a dry nitrogen atmosphere. Second, soft chains such as PNA-2000 and PEG and catalyst DBTDL (0.1%) were added at 90°C for 3 h. Then chain extender BDO was added at 80°C for 2 h to form high molecular weight copolymers. Finally, HEMA was added at 60°C for 1 h to terminate the reaction. To remove the organic solvent and oligomers, the crude polyurethanes were subsequently poured to water. Turbid liquid was centrifugated to obtain precipitants, which were redissolved in NMP and precipitated by water for three times and dried at 80°C in reduced pressure for 2 days to get the final product BPU.

Theoretical composition of polyurethanes.

| Samples | Molar ratio (mmol) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BES-Na | IPDI | PNA-2000 | PEG-800 | IPDI | BDO | HEMA | |

| BPU (1) | 0.5 | 1.0 | 2.5 | 2.0 | 6.0 | 1.55 | 0.9 |

| BPU (2) | 0.8 | 1.6 | 2.5 | 2.0 | 5.4 | 1.25 | 0.9 |

| BPU (3) | 1.0 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 2.0 | 5.0 | 1.05 | 0.9 |

| BPU (4) | 1.5 | 3.0 | 2.5 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 0.55 | 0.9 |

| BPU (1-1) | 0.5 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 1.5 | 6.0 | 1.55 | 0.9 |

| BPU (1-3) | 0.5 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 6.0 | 1.55 | 0.9 |

Synthesis route of the BPU polyurethane copolymers.

2.3 Characterization of polyurethanes

2.3.1 1H NMR

1H NMR spectra of polyurethanes were recorded using chloroform-d (CDCl3) as the solvent and tetramethylsilane as an internal standard on an Avance III HD 400 MHz (Bruker Biospin) spectrometer.

2.3.2 Fourier transform infrared

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) data were obtained on KBr slice between 4000 and 500 cm−1 with the Vertex 70 spectrophotometer (Brooker).

2.4 Preparation of polyurethane micelles (blank micelles and FA-loading micelles)

Polyurethane micelles were prepared by dialysis. Typically, BPU (10 mg) and FA were completely dissolved in 3 ml DMF by ultrasound to achieve FA-loading micelles (blank micelles without FA). Subsequently, the semitransparent solution was added drop by drop into 10 ml distilled water under magnetic stirring at 25°C. Afterwards, the semifinished micelle solution was transferred to the dialysis bag (MWCO, 8000–14,000) with distilled water to eliminate the organic solvent at room temperature, and the dialysis water was renewed every other hour. The achieved micelle solution was passed through a 0.45 μm pore-sized syringe filter and diluted to 20 ml; the achieved micelle concentration was 0.5 mg⋅ml−1.

2.5 Characterization of polyurethane micelles (blank micelles and FA-loading micelles)

2.5.1 Transmission electron microscopy

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was recorded on a JEOL JEM-2010 microscope with an accelerating voltage of 200 kV. The micellar solution was stained by 1% (w/v) phosphotungstic acid. Sample preparation was conducted on a copper grid with formvar film, with the liquid blotted off at room temperature before measurement.

2.5.2 Dynamic light scattering (DLS)

Size distribution of polyurethane nanomicelles was performed on a Zetasizer Nano ZS dynamic light-scattering instrument (Malvern, UK) at 25°C at an angle of 90°.

2.5.3 The critical micelle concentration

The critical micelle concentration (CMC) was calculated by fluorescence spectroscopy, and pyrene was used as a probe (29), (30). The measurements were recorded on an Edinburgh FLS 980 spectrometer (UK). The concentrations of polyurethane nanomicelles varied from 0.5 to 8.0×10−6 mg⋅ml−1, and the same concentration of pyrene in acetone was added into this arranged series of micellar solutions. After acetone evaporated, the final pyrene concentrations were fixed to 6.0×10−7 mg⋅ml−1. The combined solutions of polyurethane and pyrene were equilibrated at room temperature in the dark for 24 h before measurement. Steady-state fluorescence spectra were obtained with the excitation spectra scanned from 250 to 500 nm at room temperature. The bandwidths for excitation were 2.5 and 2.5 nm for emission, respectively, and the emission wavelength was 340 nm. The intensity ratio of the peak at 372.5 nm (I1/the first vibrational band) to that at 392.5 nm (I3/the third band) from excitation spectra was recorded. A function was established as the plot of I3/I1 to logarithm of concentration, whereas the corresponding concentration of the inflection point in the graphic was considered as the CMC.

2.5.4 Drug loading and release in vitro

FA was used as the model drug loaded into pH-sensitive polyurethane nanomicelles by a micelle extraction technique as mentioned above. Loading content (LC) and entrapment efficiency (EE) of FA were determined by UV-Vis-NIR spectrophotometer (UV-2000, 50 Hz, Beijing), operating in 200–350 nm spectral range, and the UV adsorption of FA was recorded at 280 nm. The FA LC (%) and EE (%) were calculated based on the following equations [1, 2]:

In vitro drug release experiment of FA-loading polyurethane nanomicelle using a dialysis method was performed as follows in triplicate at different pH value. Five milliliter of 0.5 mg⋅ml−1 FA-loading micelle solution was immersed into a dialysis tube (MWCO 8000–14,000) and dialyzed against 95 ml PBS (10 mm, pH 7.4, 6.8 or 5.0) in a beaker, which was placed at a 37°C water bath and stirred slowly. At desired time intervals, 5 ml of release media was sampled and refreshed with an equal volume of fresh media. The release concentration of FA was analyzed using UV-Vis-NIR spectrophotometer (UV-2000, 50 Hz, Beijing), operating at 280 nm, and then the cumulative drug release percent (Er) was calculated based on the equation [3]

where mFA represents the amount of FA in the polyurethane nanomicelle, Ve is the displacement volume of PBS, V0 is the whole volume of the release media, Ci represents the concentration of FA in the sample and n is the number of changing the media.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Synthesis of pH-sensitive polyurethanes

BPU copolymers were synthesized via four steps. BES-Na bearing tertiary amino/sulfonic was not soluble in NMP as the functional pH-sensitive monomer, so BES-Na was firstly added to the reaction tube with two times the equivalent of IPDI as heterogeneous reaction, leading functional groups into the polymer. After the insoluble monomer was completely dissolved, PNA-2000 and PEG (800) were used as soft chains of large molecular weight. PNA-2000 was introduced as the hydrophobic chain (31), which played the role of increasing the drug loading capacity, and PEG (800) was the hydrophilic chain (32) of polyurethane nanomicelle, which could shield the particle surface (28), increasing biocompatibility, prolonging circulation (33), (34).

The structures of the synthetic polyurethanes were identified by 1H NMR and FTIR, respectively, as shown in Figures 2 and 3. Figure 2 expounded the 1H NMR spectrogram of BPU performed in CDCl3. As shown in the graph, the resonance peak at 3.869 ppm belonged to the protons of methenyl connected to isocyanate group (-CH-NCO) of IPDI, the peak centered at 3.645 ppm was accounted for the protons of methoxyl (-O-CH2-) on the PEG units, as 3.294 ppm to the protons of methoxyl (-O-CH2-) on PNA-2000 and the resonance peak at 2.322~2.389 ppm was attributed to the protons of methylene connected to nitrogen (-N-CH2-) on BES-Na and PNA-2000. The resonances 1.634~1.671 ppm were mainly assigned to the protons of methylene (-C-CH2-) that were not connected to a hybrid atom, and the peaks around 0.952 and 0.910 ppm declared the protons of methyl (-CH3) on IPDI and PNA-2000.

1H NMR spectra of BPU (1), BPU (2) and BPU (3).

FTIR spectra of IPDI, BPU (1), BPU (2) and BPU (3).

The FTIR spectra of polyurethanes are shown in Figure 3. Compared to IPDI, the disappearance of absorption at about 2200–2300 cm−1 accounted for the complete repercussion of the isocyanate (35). The absorption peaks at 1533 cm−1 represented the deformation vibration of the N-H band, a broad stretching band at about 3534 cm−1 was mainly assigned to the N-H stretching vibration and intramolecular hydrogen bond and 3379 cm−1 showed intermolecular hydrogen bond. The peaks of 2961 and 2882 cm−1 corresponded to the symmetrical and antisymmetric stretching vibration of C-H, respectively, whereas the peaks of 1469 and 1379 cm−1 corresponded to the symmetrical and antisymmetric deformation vibration of C-H, respectively. The absorption peak at 1735 cm−1 was attributed to the C=O stretching band. The absorption peaks at 1247 cm−1 belonged to the C-O stretching band, whereas 1170 cm−1 was attributable to the C-O-C stretching band of PEG (11), and the peak at 1020 cm−1 vested in the S=O stretching band of BES-Na showed that BES-Na has been introduced into polyurethane.

3.2 Characterization of BPU micelles

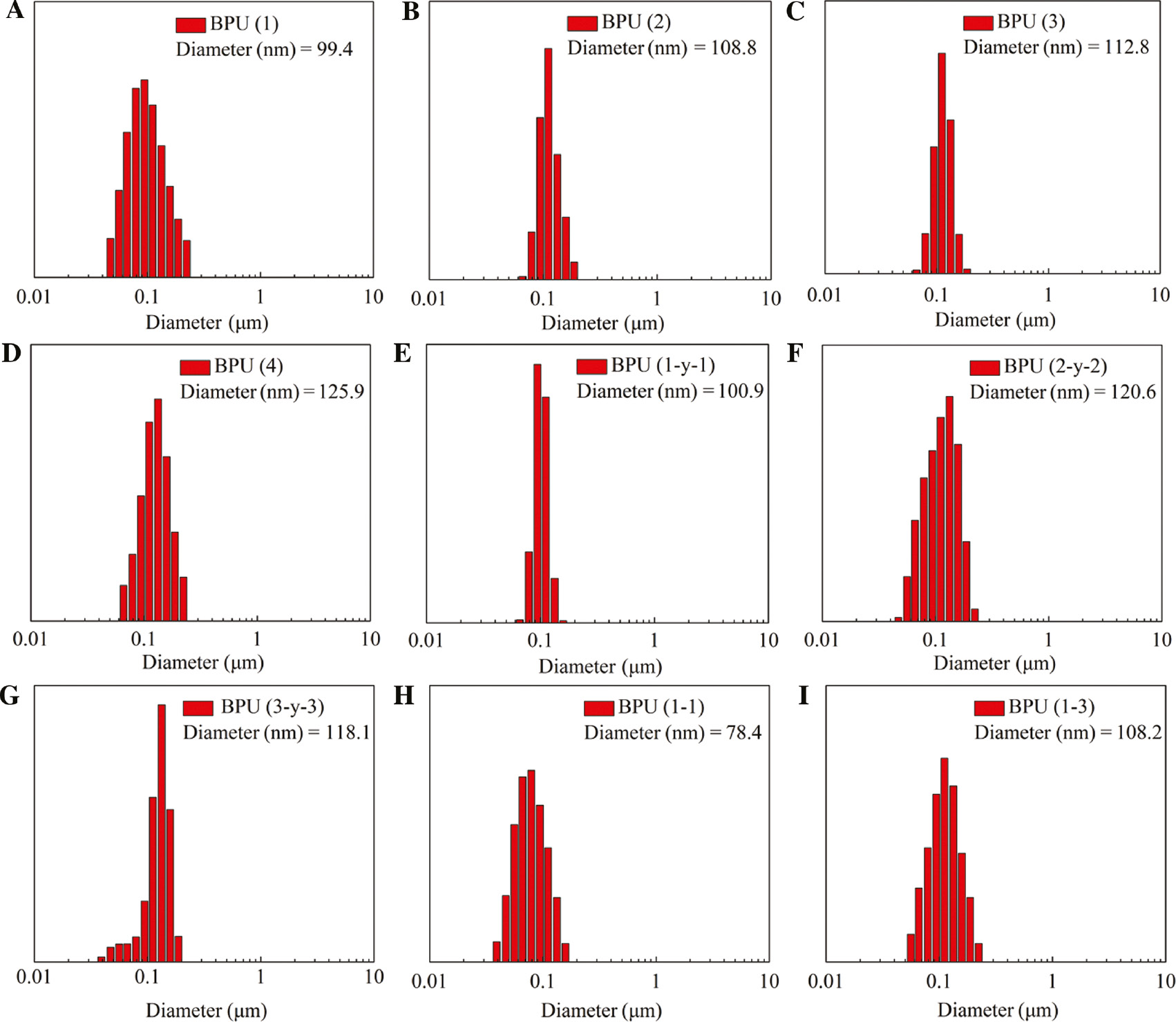

The DLS measurements of BPU micelles are exhibited in Figure 4, with increased dosage for functional monomer BES-Na. The average size of BPU micelles increasing slightly from 99.4 nm (A) of 0.5 mmol to 125.9 nm (D) of 1.5 mmol. These results were attributed to the hydrogen-bond interaction and the electric charge effect of tertiary amino/sulfonic in aqueous medium. The repulsive force was more powerful due to the structure of strong acid-weak base; thus, the higher the BES-Na, the more obvious the effect, which made the micelles pH sensitive. After loading FA, the particle size of nanomicelles [BPU (1-3)] swelled to about 120 nm on average (E–G). There were also increasing influences on the size of micelle, if the ratio of hydrophilic chain and hydrophobic chain increased. The results indicated that the particle size of nanomicelles was about 78.4 nm (H), when the ratio of hydrophobic and hydrophilic chains was 3.0:1.5, and increased to 108.2 nm (I) when the ratio was changed to 2.0:2.5. In aqueous medium, hydrophilic PEG shell stretched freely and wrapped the frizzly hydrophobic PNA-2000 core, that is, when density increased in the hydrophilic chain, the particle size of the micelle also increased, which is beneficial to drug delivery and nanomicelle transportation due to the excellent characteristic of “shielding” (36).

Size distribution of polyurethanes micelles determined by DLS.

BPU micelles with different feed ratios as shown in Table 1 (A, B, C, D, H, I ), FA-loading micelles of BPU (1, 2, 3) (E, F, G ).

The morphology of BPU micelles was achieved by TEM. As shown in Figure 5, after negative staining with phosphotungstic acid, micelles come into view with similar spherical morphology and uniform sizes about 60 nm. Comparing the TEM data with the statistical result of DLS, the sizes had shrunk a lot, which is mostly attributed to the shrunk hydrophilic chain PEG (37, 38) and the weakened tertiary amino/sulfonic mutual effect.

TEM micrograph of BPU micelles.

BPU(1) with different amplification ratio (A) 200 nm (B) 30 nm.

The critical micellar concentration (CMC) of nanomicelle was determined by fluorescence spectroscopy using pyrene as a fluorescence probe, as shown in Figure 6. All kinds of polyurethane micelles formed under very low concentration, just like CMC of BPU (1), had a value of 0.091×10−3 mg⋅ml−1. As BES-Na increased, the CMC increased from 0.091×10−3 mg⋅ml−1 to 0.104×10−3 mg⋅ml−1 when the amount of substance of BES-Na was 0.8 mmol, and to 0.118×10−3 mg⋅ml−1 when the content of BES-Na was 1.0 mmol. As was shown above, these polyurethane micelles would aggregate to the self-assembling morphology although the concentrations were very low, which would improve micellar stability. The increase in CMC may because the repulsion increased as more sulfonic acid group existed.

Intensity ratio (I392.5/I372.5) in fluorescence spectra versus concentrations of polyurethanes BPU (1, 2, 3) in water.

(A) BPU(1), (B) BPU(2), (C) BPU(3).

3.3 In vitro pH-triggered drug release

Drug loading and releasing were evaluated by UV-visible spectroscopy. We used FA as a model hydrophobic drug to validate the loading and releasing ability of BPU nanomicelles in vitro. FA could be detected with a maximum absorption wavelength of about 280 nm even if it is enshrouded in micellar nucleus as a model drug. The statistical significances are listed in Figure 7 and Table 2. The LCs and EEs of the BPUs were determined to be 3.19%–7.68% and 32.95%–27.72%, respectively. BPU (3) equipped the highest; LC and EE were 7.68% and 27.72%, which indicated that the content of BES-Na had a significant influence to micelles, consistent with other characterization test results above. The drug release behaviors of BPUs were investigated at neutral (pH 7.4) and two kinds of acidic (pH 5.0 and pH 6.8) PBS simulating the organism environment at 37°C. A function was established by cumulative drug release (%) of release time. All release curves were synchronized wherein the drug release rates were faster within the first 5 h and gradually slowed to basically the same within 24 h. Apparently, at acidic solution environment, the release efficiency of drug-loading nanomicelles was higher than the same ones at neutral environment, which is induced by the protonation of tertiary amine groups and sulfonate groups. The surface charge of nanomicelles changed, and the release of FA was promoted by the electrostatic interaction between FA and nanomicelles. In detail, the maximum cumulative drug release percent (Er) of BPU (3) could achieve 89.83% at pH 5.0.

![Figure 7: Release profiles of FA of polyurethane nanomicelles [BPU (1, 2, 3)] in PBS (pH 7.4, 6.8, 5.0).(A) BPU(1), (B) BPU(2), (C) BPU(3).](/document/doi/10.1515/epoly-2018-0030/asset/graphic/j_epoly-2018-0030_fig_007.jpg)

Release profiles of FA of polyurethane nanomicelles [BPU (1, 2, 3)] in PBS (pH 7.4, 6.8, 5.0).

(A) BPU(1), (B) BPU(2), (C) BPU(3).

Characterization of BPU micelles for drug delivery.

| Samples | CMC (μg/ml) | LC (%) | EE (%) | Er (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH 7.4 | pH 6.8 | pH 5.0 | ||||

| BPU (1) | 0.09 | 3.19 | 32.95 | 46.85 | 54.19 | 65.48 |

| BPU (2) | 0.10 | 5.01 | 26.40 | 51.76 | 70.62 | 88.50 |

| BPU (3) | 0.12 | 7.68 | 27.72 | 58.29 | 79.17 | 89.83 |

4 Conclusions

We have developed a kind of pH-sensitive polyurethane nanomicelles bearing two amphoteric groups (tertiary amino/sulfonic) as functional group and PEG and PNA-2000 as soft chains to adjust the size. The synthesis process was simple and easy to operate, and the influence of functional group content and the ratio of hydrophilic and hydrophobic chain on the particle size of micelle were investigated. The final compounds possessed a very low CMC and were pH sensitive based on the zwitterionic construction. In in vitro drug loading and release of polyurethane micelles, the highest LC and EE were 7.68% and 27.72% of FA. In addition, at acidic solution environment, the release efficiency of drug-loading nanomicelles was higher than the same ones at neutral environment. The research lays the foundation for the next stage of drug delivery and release research in vivo.

References

1. Mura S, Nicolas J, Couvreur P. Stimuli-responsive nanocarriers for drug delivery. Nat Mater. 2013;12:991–1003.10.1038/nmat3776Search in Google Scholar

2. Song ZX, Liu Y, Shi J, Ma T, Zhang Z, Ma H, Cao SK. Hydroxyapatite/mesoporous silica coated gold nanorods with improved degradability as a multi-responsive drug delivery platform. Mater Sci Eng C. 2018;83:90–8.10.1016/j.msec.2017.11.012Search in Google Scholar

3. Masayuki Y, Mizue M, Noriko Y, Teruo O, Yasuhisa S, Kazunori K, Shohei I. Polymer micelles as novel drug carrier: adriamycin-conjugated poly (ethylene glycol)-poly (aspartic acid) block copolymer. J Control Release. 1990;11:269–78.10.1016/0168-3659(90)90139-KSearch in Google Scholar

4. Kazunori K, Kwon GS, Masayuki Y, Teruo O, Yasuhisa S. Block copolymer micelles as vehicles for drug delivery. J Control Release. 1993;24:119–32.10.1016/0168-3659(93)90172-2Search in Google Scholar

5. Kataoka AHK. Formation of stable and monodispersive polyion complex micelles in aqueous medium from poly(L-lysine) and poly (ethylene glycol)-poly (aspartic acid) block copolymer. J Macromol Sci A. 1997;34:2119–33.10.1080/10601329708010329Search in Google Scholar

6. Ding M, He X, Wang Z, Li J, Tan H, Deng H, Fu Q, Gu Q. Cellular uptake of polyurethane nanocarriers mediated by gemini quaternary ammonium. Biomaterials 2011;32:9515–24.10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.08.074Search in Google Scholar

7. Xu SH, Shi J, Feng DS, Yang L, Cao SK. Hollow hierarchical hydroxyapatite/Au/polyelectrolyte hybrid microparticles for multi-responsive drug delivery, J Mater Chem B. 2014;2:6500–7.10.1039/C4TB01066CSearch in Google Scholar

8. Matsumura Y, Maeda H. A new concept for macromolecular therapeutics in cancer chemotherapy: mechanism of tumoritropic accumulation of proteins and the antitumor agent smancs. Cancer Res. 1986;46:6387–92.Search in Google Scholar

9. Fang J, Nakamura H, Maeda H. The EPR effect: unique features of tumor blood vessels for drug delivery, factors involved, and limitations and augmentation of the effect. Adv Drug Deliver Rev. 2011;63:136–51.10.1016/j.addr.2010.04.009Search in Google Scholar

10. Maeda H, Wu J, Sawa T, Matsumura Y, Hori K. Tumor vascular permeability and the EPR effect in macromolecular therapeutics: a review. J Control Release. 2000;65:271–84.10.1016/S0168-3659(99)00248-5Search in Google Scholar

11. Yao Y, Xu D, Liu C, Guan Y, Zhang J, Su Y, Zhao L, Meng F, Luo J. Biodegradable pH-sensitive polyurethane micelles with different polyethylene glycol (PEG) locations for anti-cancer drug carrier applications. RSC Adv. 2016;6:97684–93.10.1039/C6RA20613ASearch in Google Scholar

12. Wang T, Wang D, Yu H, Wang M, Liu J, Feng B, Zhou F, Yin Q, Zhang Z, Huang Y, Li Y. Intracellularly acid-switchable multifunctional micelles for combinational photo/chemotherapy of the drug-resistant tumor. ACS Nano. 2016;10:3496–508.10.1021/acsnano.5b07706Search in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Tan S, Yin M, Song Q, Bao Y, Zhang Z. Novel redox-sensitive mixed micelle with enhanced antitumor activity. J Control Release. 2015;213:E148–9.10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.05.251Search in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Wang X, Guerin G, Wang H, Wang Y, Manners I, Winnik MA. Cylindrical block copolymer micelles and co-micelles of controlled length and architecture. Science 2007;317:644–7.10.1126/science.1141382Search in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Wei H, Cheng SX, Zhang XZ, Zhuo RX. Thermo-sensitive polymeric micelles based on poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) as drug carriers. Prog Polym Sci. 2009;34:893–910.10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2009.05.002Search in Google Scholar

16. Sharipov M, Tawfik SM, Gerelkhuu Z, Huy BT, Lee YI. Phospholipase A2-responsive phosphate micelle-loaded UCNPs for bioimaging of prostate cancer cells. Sci Rep-UK. 2017;7:16073.10.1038/s41598-017-16136-4Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

17. Gao L, Zheng B, Chen W, Schalley CA. Enzyme-responsive pillar [5] arene-based polymer-substituted amphiphiles: synthesis, self-assembly in water, and application in controlled drug release. Chem Commun. 2015;51:14901–4.10.1039/C5CC06207ASearch in Google Scholar

18. Du C, Shi J, Shi J, Zhang L, Cao SK. PUA/PSS multilayer coated CaCO3 microparticles as smart drug delivery vehicles. Mater Sci Eng C. 2013;33:3745–52.10.1016/j.msec.2013.05.004Search in Google Scholar PubMed

19. Ganta S, Devalapally H, Shahiwala A, Amiji M. A review of stimuli-responsive nanocarriers for drug and gene delivery. J Control Release. 2008;126:187–204.10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.12.017Search in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Chu Z, Dreiss CA, Feng Y. Smart wormlike micelles. Chem Soc Rev. 2013;42:7174–203.10.1039/c3cs35490cSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Mahanta AK, Mittal V, Singh N, Dash D, Malik S, Kumar M, Maiti P. Polyurethane-grafted chitosan as new biomaterials for controlled drug delivery. Macromolecules 2015;48: 2654–66.10.1021/acs.macromol.5b00030Search in Google Scholar

22. Kishan AP, Wilems T, Mohiuddin S, Cosgriffhernandez EM. Synthesis and characterization of plug-and-play polyurethane urea elastomers as biodegradable matrixes for tissue engineering applications. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2017;3:3493–502.10.1021/acsbiomaterials.7b00512Search in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Wu J, Wang H, Su Z, Zhang M, Hu X, Wang Y, Wang Z, Zhong B, Zhou W, Liu J. Highly flexible and sensitive wearable E-skin based on graphite nanoplatelet and polyurethane nanocomposite films in mass industry production available. Acs Appl Mater Inter. 2017;9:38745–54.10.1021/acsami.7b10316Search in Google Scholar PubMed

24. Chai Q, Huang Y, Ayres N. Shape memory biomaterials prepared from polyurethane/ureas containing sulfated glucose. J Polym Sci Pol Chem. 2015;53:2252–7.10.1002/pola.27668Search in Google Scholar

25. Aksoy EA, Taskor G, Gultekinoglu M, Kara F, Ulubayram K. Synthesis of biodegradable polyurethanes chain-extended with (2S)-bis(2-hydroxypropyl) 2-aminopentane dioate. J Appl Polym Sci. 2018;135:45764.10.1002/app.45764Search in Google Scholar

26. Pan Z, Fang D, Song N, Song Y, Ding M, Li J, Luo F, Tan H, Fu Q. Surface distribution and biophysicochemical properties of polymeric micelles bearing gemini cationic and hydrophilic groups. Acs Appl Mater Inter. 2017;9:2138–49.10.1021/acsami.6b14339Search in Google Scholar PubMed

27. Su Y-L, Zhao L, Meng F, Wang Q, Yao Y, Luo J. Silver nanoparticles decorated lipase-sensitive polyurethane micelles for on-demand release of silver nanoparticles. Colloid Surface B. 2017;152:238–44.10.1016/j.colsurfb.2017.01.036Search in Google Scholar PubMed

28. Zhu C, Li Y. PEG-sheddable reduction-sensitive polyurethane micelles for triggered intracellular anti-tumor drug delivery. J Control Release. 2017;259:E14–5.10.1016/j.jconrel.2017.03.059Search in Google Scholar

29. Ma L, Geng H, Song J, Li J, Chen G, Li Q. Hierarchical self-assembly of polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane end-capped stimuli-responsive polymer: from single micelle to complex micelle. J Phys Chem B. 2011;115:10586–91.10.1021/jp203782gSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

30. Zhang CY, Yang YQ, Huang TX, Zhao B, Guo XD, Wang JF, Zhang LJ. Self-assembled pH-responsive MPEG-b-(PLA-co-PAE) block copolymer micelles for anticancer drug delivery. Biomaterials 2012;33:6273–83.10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.05.025Search in Google Scholar PubMed

31. Moughton AO, Hillmyer MA, Lodge TP. Multicompartment block polymer micelles. Macromolecules 2012;45:2–19.10.1021/ma201865sSearch in Google Scholar

32. Otsuka H, Nagasaki Y, Kataoka K. PEGylated nanoparticles for biological and pharmaceutical applications. Adv Drug Deliver Rev. 2012;64:246–55.10.1002/9781118135440.ch47Search in Google Scholar

33. Wu H, Zhu L, Torchilin VP. pH-sensitive poly(histidine)-PEG/DSPE-PEG co-polymer micelles for cytosolic drug delivery. Biomaterials 2013;34:1213–22.10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.08.072Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

34. Taipaleenmki EM, Mouritzen SA, Schattling PS, Zhang Y, Staedler B. Mucopenetrating micelles with a PEG corona. Nanoscale 2017;9:18438–48.10.1039/C7NR06821BSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

35. John JV, Thomas RG, Lee HR, Chen H, Jeong YY, Kim I. Phospholipid end-capped acid-degradable polyurethane micelles for intracellular delivery of cancer therapeutics. Adv Healthc Mater. 2016;5:1874–83.10.1002/adhm.201600126Search in Google Scholar PubMed

36. Lutz JF, Hoth A. Preparation of ideal PEG analogues with a tunable thermosensitivity by controlled radical copolymerization of 2-(2-methoxyethoxy) ethyl methacrylate and oligo (ethylene glycol) methacrylate. Macromolecules 2006;39:893–6.10.1021/ma0517042Search in Google Scholar

37. Deng H, Liu J, Zhao X, Zhang Y, Liu J, Xu S, Deng L, Dong A, Zhang J. PEG-b-PCL copolymer micelles with the ability of pH-controlled negative-to-positive charge reversal for intracellular delivery of doxorubicin. Biomacromolecules 2014;15:4281–92.10.1021/bm501290tSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

38. Long YB, Gu WX, Pang C, Ma J, Gao H. Construction of coumarin-based cross-linked micelles with pH responsive hydrazone bond and tumor targeting moiety. J Mater Chem B. 2016;4:1480–8.10.1039/C5TB02729BSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

©2018 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- In this Issue

- Review

- Progress in semicrystalline heat-resistant polyamides

- Full length articles

- Functional polyurethane nanomicelle with pH-responsive drug delivery property

- Which average of copolymer composition does NMR provide?

- Synthesis of random copolymer of isobutylene with p-methylstyrene by cationic polymerization in ionic liquids

- Study on epoxy resin with high elongation-at-break using polyamide and polyether amine as a two-component curing agent

- Optimization of the fabrication conditions and effects of multi-walled carbon nanotubes on the tensile properties of various glass fibers/unsaturated polyester resin composites

- Meta-linked cationic poly(pyridinylene vinylene) conjugated polyelectrolytes: solution photophysics and fluorescent sensing of metal ions

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- In this Issue

- Review

- Progress in semicrystalline heat-resistant polyamides

- Full length articles

- Functional polyurethane nanomicelle with pH-responsive drug delivery property

- Which average of copolymer composition does NMR provide?

- Synthesis of random copolymer of isobutylene with p-methylstyrene by cationic polymerization in ionic liquids

- Study on epoxy resin with high elongation-at-break using polyamide and polyether amine as a two-component curing agent

- Optimization of the fabrication conditions and effects of multi-walled carbon nanotubes on the tensile properties of various glass fibers/unsaturated polyester resin composites

- Meta-linked cationic poly(pyridinylene vinylene) conjugated polyelectrolytes: solution photophysics and fluorescent sensing of metal ions