Abstract

234 Various reasons have been put forward for the declining global relevance of the London equity market. Reform proposals and changes already implemented target some of the major problems identified as reasons for the stock market’s decline. Surprisingly, tax related explanations for the current state of the UK stock market are largely absent from the discourse. This paper argues that the preferential tax treatment of the dividend income of UK pension funds and insurance companies introduced in the early 1970s and repealed in the mid 1990s first contributed to the UK stock market’s growth by implicitly subsidising financing via equity and encouraging the flow of the funds of these investors into the market, and subsequently led to the market’s decline as a result of the outflow of the funds of the two major classes of institutional investors: UK pension funds and insurance companies. The key implication of this argument is that omitting tax as a major factor in the decline of the UK stock market risks ending up with reforms that can, at best, do little to change the current situation.

I. 235Introduction

The London Stock Exchange is not the global marketplace that it used to be. This is clear even without going back to the late 1980s and early 1990s – the heyday of London’s stock market. The share of the London Stock Exchange (LSE) in the global equity value of listed companies has more than halved during the last decade.[1] Not only is the combined market capitalisation of companies listed on the LSE falling, but their numbers are also dwindling.[2] The UK equity market is the only major developed market to have shrunk relative to GDP over the past 20 years, according to New Financial, a think tank.[3] The capitalisation of the market decreased from 104% of GDP for the UK in 2002 to 94% of GDP in 2022.[4] By contrast, the capitalisation of the US stock market relative to US GDP increased by almost 55% during the same period (from 101% of GDP to 156% of GDP).[5] The underperformance of the London stock market relative to others and its declining global relevance may be seen as a risk to London’s reputation as a global financial hub. Paul Marshall, the chair and co-founder of Europe’s largest hedge fund with headquarters in London, warned somewhat dramatically in 2021 that the City of London was in danger of becoming “the Jurassic Park” of stock markets.[6] According to the chief executive of one of the Britain’s largest insurers, Legal & General, London’s stock exchange has been in “perpetual drift:” “[t]here’s a drift of the City to Europe; there is a drift of the City to the United States.”[7] Not surprisingly, the decline of the stock market has drawn the attention of politicians. The former Chancellor Jeremy Hunt promised reforms that would make UK capital 236markets more attractive in his speech in the City of London in July 2023.[8] Before that, then-Chancellor Rishi Sunak launched two independent reviews that would put forward recommendations for strengthening the UK’s position as a leading global financial centre.[9]

Different reasons have been put forward to explain the decline of London’s stock market, and there are undoubtedly a multitude of factors that have contributed to it. Somewhat surprisingly, explanations related to tax have been largely absent from the ongoing discourse. This paper argues that tax incentives likely played a critical role in the rise and subsequent decline of the UK stock market first by encouraging the flow of funds into the market and next by contributing to the outflow of the funds from the market. The preferential tax treatment of the dividend income of certain major UK institutional investors drew their funds into the London equity market in the period between mid-1970s and mid-1990s, which contributed substantially to the rise of the market. Similarly, we argue that tax – or, more specifically, the repeal of the tax incentives that had been in place before – partly explains the outflow of funds from London’s equity market starting from late 1990s and the market’s subsequent decline.

The link between tax rules and the various elements of stock markets has been proposed in the literature in the past. Brian Cheffins and Steven Bank used tax to explain ownership and control patterns of large listed British companies in an article published in 2007.[10] In a book published a year later, Brian Cheffins drew attention to the implications of the UK’s dividend taxation reform in mid-1990s for institutional share ownership and explained that the declining ownership of UK equities by pension funds and insurance companies would weaken active investor stewardship.[11] But surprisingly the impact of tax changes on the rise and relative decline of London’s equity market has other237wise largely been neglected in academic literature, policy debates, and media. This paper fills this gap by showing how different regimes concerning the taxation of dividend income affected the incentives of pension funds and the pension component of insurance companies to invest in UK equities and, in turn, in the London stock market. The implication of this paper, however, is not that the government should restore the preferential treatment of pension fund income derived from dividends (or indeed that the size of the London equity market should be a policy goal at all). Rather, this analysis merely suggests that tax has in the past played an important role in the development of the London equity market, and that it should not be neglected when designing regulatory strategies for reviving it.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows. The next section briefly reviews the main existing explanations for the decline of London’s equity markets and the reforms and reform proposals that have been put forward to address these problems. Next, the paper introduces tax as a major factor that explains how the funds of a leading group of UK-based institutional investors had been drawn into the shares of the FTSE companies and have subsequently flown out from these shares. Following this analysis, the next part highlights the major policy implications of the paper’s main argument. The final section concludes.

II. The Decline of London’s Equity Market and Its Mainstream Explanations

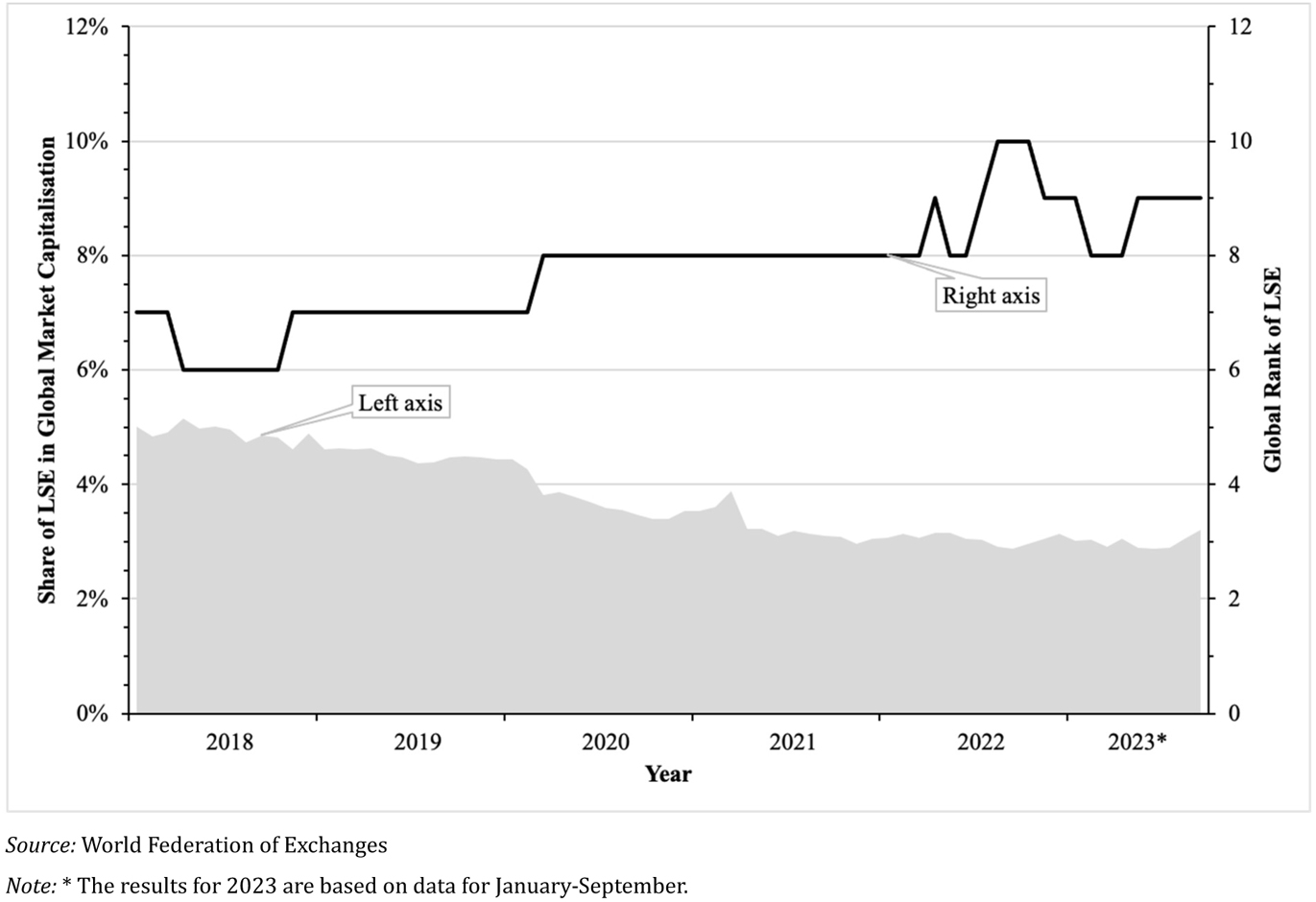

London’s equity market is on a steady decline. The share of the London Stock Exchange in the global equity value of listed companies has more than halved during the last decade. At the end of 2013, the LSE was home to the third largest domestic stock market by market capitalisation and accounted for 6.90% of the worldwide market, according to statistics provided by the World Federation of Exchanges.[12] By August 2023, companies listed on the LSE accounted for only 3.05% of global equity value (Figure 1). By then, the exchange had fallen to being the world’s ninth largest stock exchange by market capitalisation – just ahead of Saudi Stock Exchange (Tadawul) and behind the National Stock Exchange of India. The downward trend in the size of UK’s domestic market capitalisation, as illustrated in Figure 1, is clear. There were even recent short periods when the global share of the market fell below the 3% mark. Notably, the decline of the UK’s equity market did not start a decade ago; this is a longer trend that started two decades ago. The London Stock 238Exchange’s share of global equity values stood at 8.5% in 2007 but at 13% around the turn of the millenium.[13] The relative decline of London’s role in global capital markets can be partly attributed to global macroeconomic trends, including the significant rise in the emerging markets share of global equity market capitalisation over the past decades.[14]

The Declining Relevance of the London Stock Market by Market Capitalisation

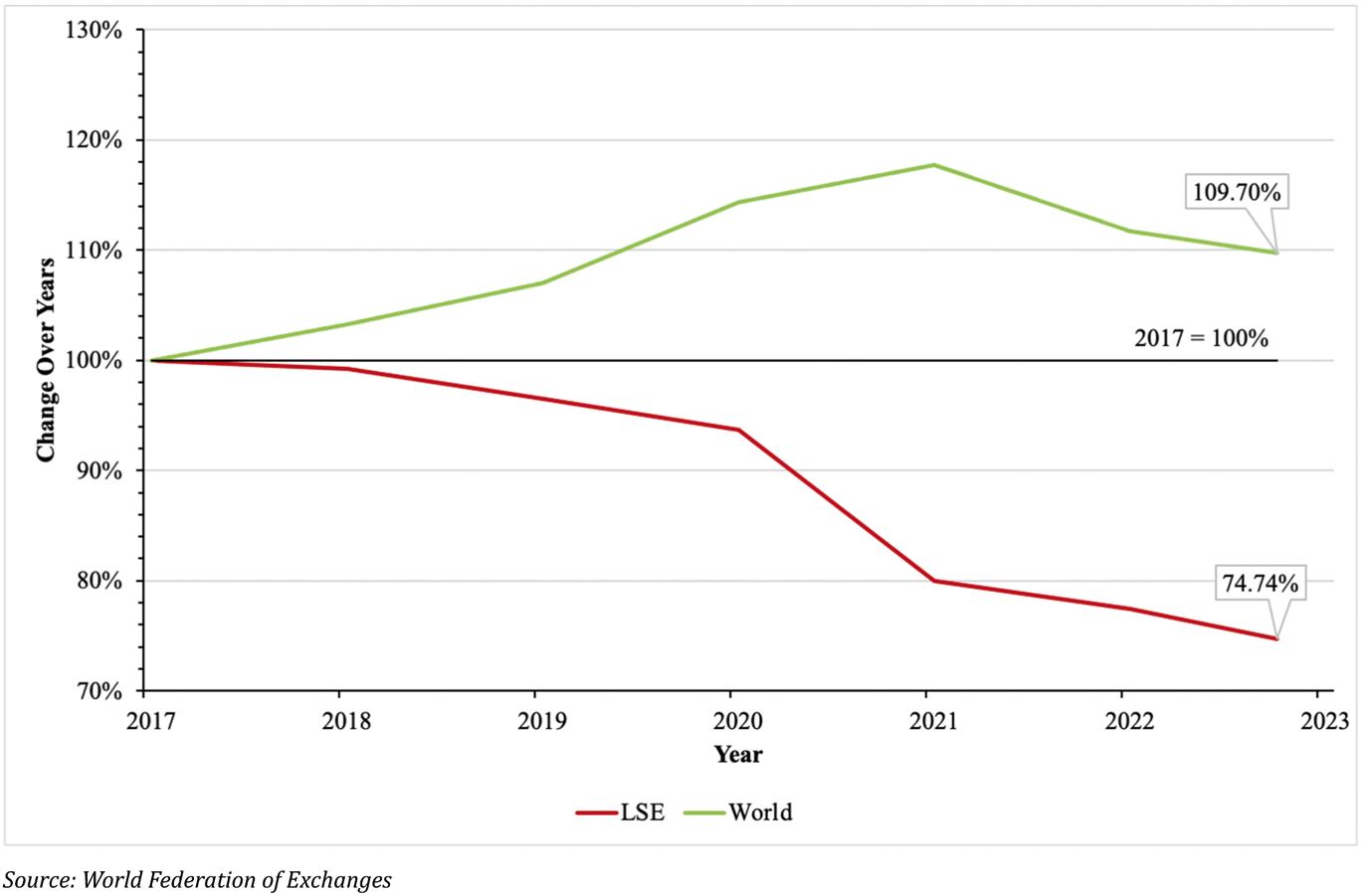

However, the total number of companies listed on the LSE is also decreasing. Figure 2 relies on data from the World Federation of Exchanges to show changes in the number of companies listed on the LSE and globally over 2017-2023. The LSE lost more than one-quarter of the listed companies during this period. In particular, there were 2,498 companies (excluding investment 239funds) listed on the various markets of the LSE at the end of 2017. The LSE was the sixth largest stock exchange by the number of listed companies in the world. In September 2023, the number of listed companies on the London stock market stood at 1,867; the LSE dropped to the 13th position in the list of the largest stock exchanges by the number of listed companies. By contrast, the number of listed companies across the world increased by more than 9% during the same period.[15]

Change in the Number of Listed Companies

The problem of a declining equity market and the questions of how to revitalise the market are high on the political and policy agenda. A recurring theme in the explanations for the dire state of the London stock market is perceived over-regulation. In a globally competitive environment where stock exchanges compete for global or regional prominence, prescriptive and stringent corporate governance rules and standards – once the hallmark of the London Stock Exchange – arguably become a weakness by undermining the competitiveness 240of London as a company listing venue. Strict requirements on minimum free float, financial audits, the use of dual-class shares, and information disclosure are important mechanisms of the investor protection ecosystem, but they may discourage companies from listing in London.[16] A consensus has been emerging among public officials, business groups, and the London Stock Exchange that more listings can be brought to London by relaxing the UK’s listing regime.[17]

One recent study extends this argument by linking the decline of the listed company in the UK with “over-governance” through soft law best practice governance standards.[18] The UK Corporate Governance Code aims to protect investor interests and promote the long-term success of companies but instead it has increased red tape and impedes innovation.[19] Accordingly, abolishing the code “might help to restore the publicly traded company to the status it held 3 decades ago.”[20] Julia Hoggett, head of the London Stock Exchange, makes a similar argument by claiming that “ever increasing corporate governance processes” have “impacted the effectiveness of listed companies and the standing of the UK over other capital markets.”[21]

More recently, industry participants have drawn attention to the UK’s unfavourable cultural norms on executive compensation.[22] In addition to easing the regulatory burden on listed companies, the City also needs a change in culture. Julia Hoggett warned that UK companies were struggling to compete for ta241lent globally.[23] To illustrate the point, business news outlets refer to the example of Laxman Narasimhan who reportedly quadrupled his pay by resigning as the CEO of Reckitt Benckiser, a FTSE 100 consumer-goods company, to become the CEO of Starbucks Corp, an American coffee chain.[24] The concern is that many UK investors, due to their reserved culture on executive pay, act to constrain the level of pay in UK companies and thus cause the best talent to migrate towards US companies, where institutional investors are more willing to tolerate high levels of executive pay, or towards private companies, where managerial pay is outside the scope of institutional investor oversight. Some experts go further by speculating that pay disparity at the top level between UK and US companies could be large enough to explain, at least partly, the motivation behind the recent de-listings of several UK companies from the London Stock Exchange with the subsequent listing on one of the US stock exchanges. The prospect of securing higher pay for top executives, in addition to higher valuations and deeper liquidity in US stock markets, could be one implicit reason for switching over to a US listing.[25] BlackRock’s Larry Fink, the chairman and CEO of the world’s largest fund manager, echoes this concern and explains the reluctance of his stewardship team to vote against high pay by the need to prevent market distortions where strict investor oversight penalises publicly traded companies.[26] Although this is a valid concern, it is also true that investors engaging with UK companies are willing to tolerate higher pay levels if a company is hiring a CEO from the US or if it has large presence in US markets.[27]

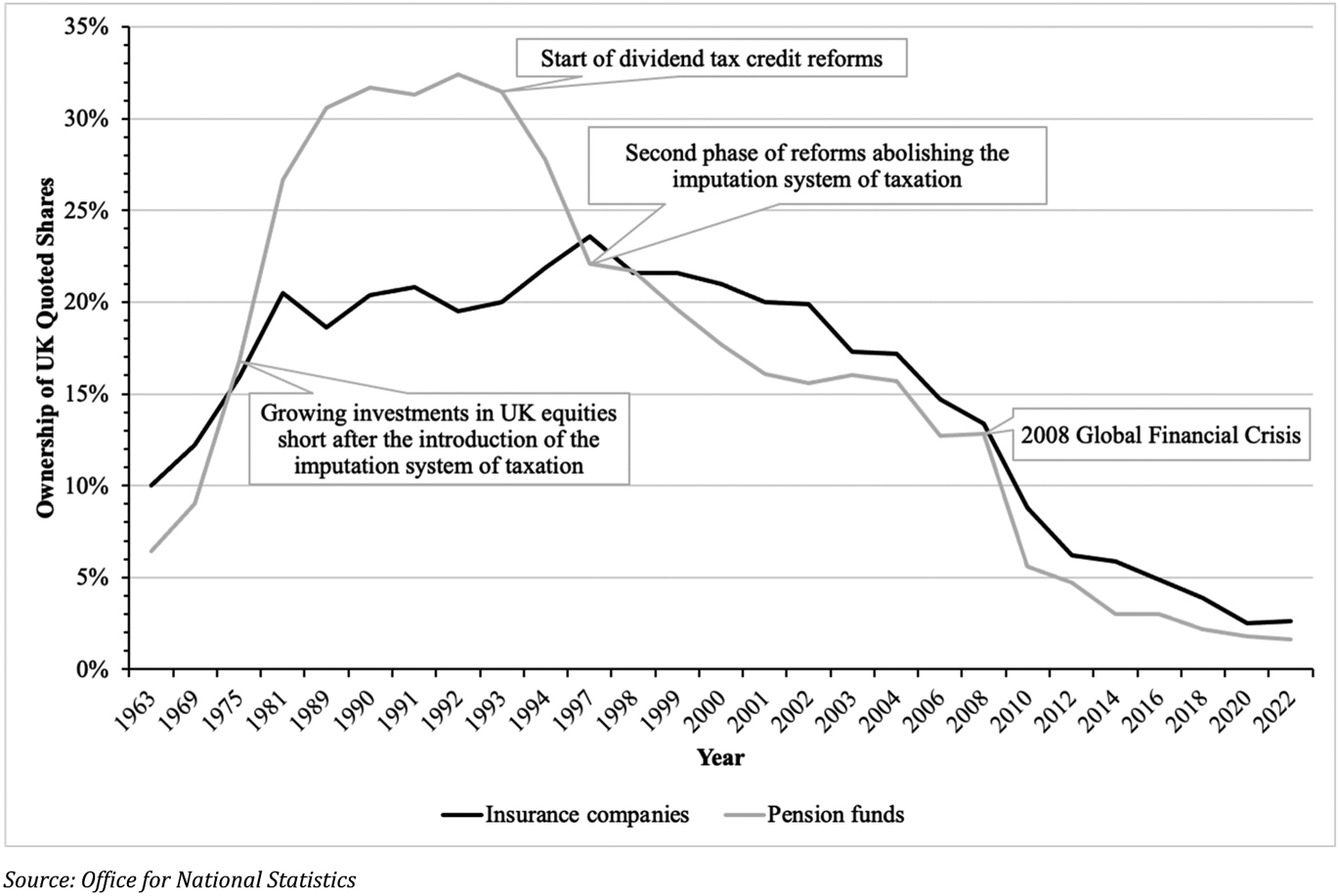

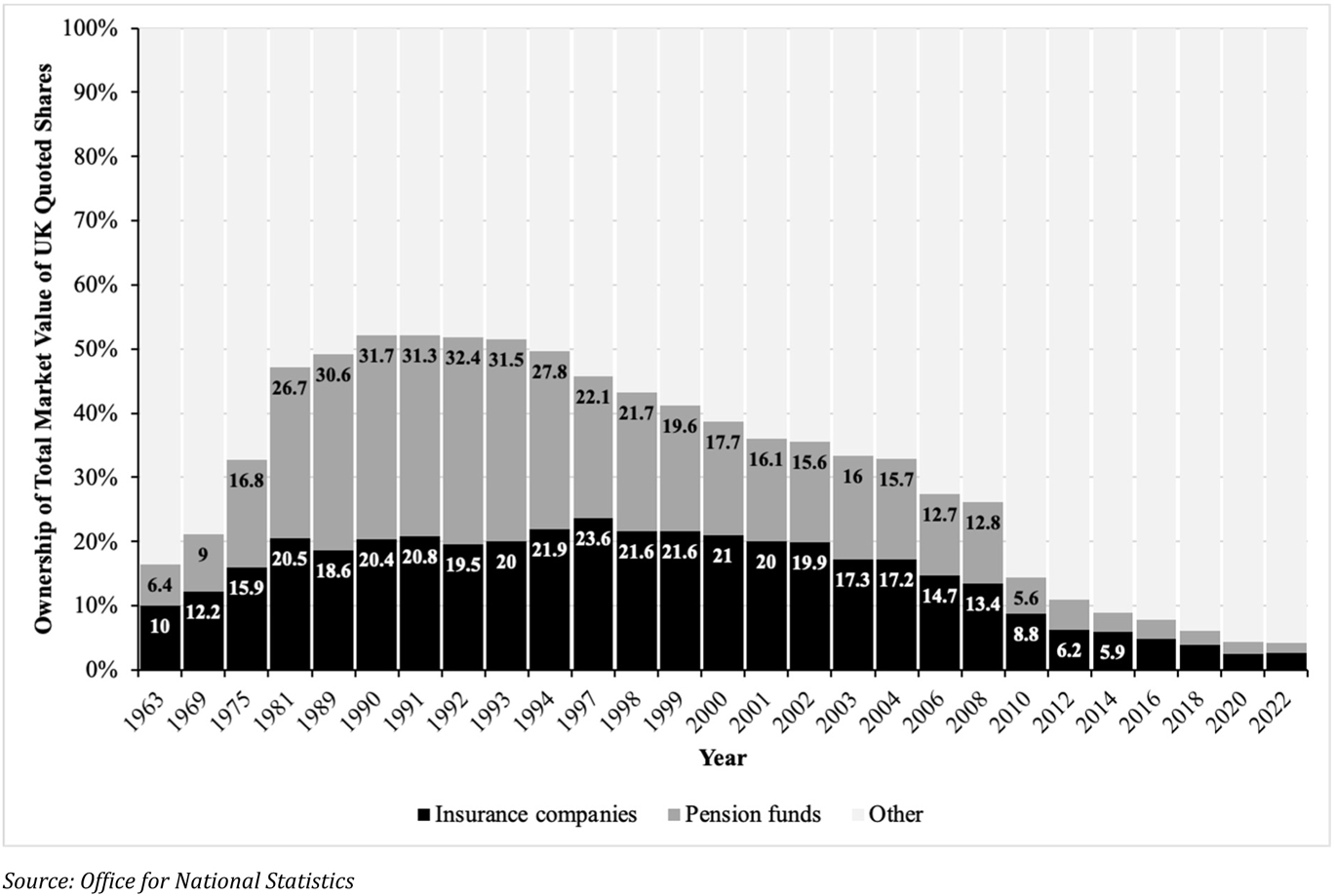

Yet others point to the reluctance of UK pension funds and insurance companies to invest in locally listed shares. Historically, these two categories of investors were prominent shareholder groups in UK publicly traded companies. 242In the 1980s, pension funds controlled around 30% of the shares of UK quoted companies, according to data from the Office for National Statistics.[28] Insurance companies controlled another 20%.[29] And, according to study by John Scott, more than half of the top 20 owners of the largest UK companies in 1976 were insurance companies and pension funds.[30] By contrast, pension funds now own less than 2% of UK listed shares, with overseas equity investments and debt holdings dominating their portfolios.[31] This declining interest has been attributed to a technical change in accounting rules made in the mid 2000s.[32]

Identifying accurately the reasons for the decline of London’s stock market is important to offer solutions that can revitalise the market. Based on the reasons highlighted above, experts and policymakers have proposed relaxing rules and governance standards for UK listed companies, changing corporate culture, and other measures. The UK government responded to the declining relevance of the UK equity market by proposing two separate reform packages: the Edinburgh Reforms primarily targeting stock market listings introduced in a written statement of the Chancellor of the Exchequer to Parliament in December 2022;[33] and the Mansion House proposals on pensions reform outlined by the Chancellor in July 2023.[34] The latter reforms promised by the Chancellor include two broad proposals for reviving UK stock markets: (1) directing more pension fund savings towards equity investments by consolidating highly fragmented pension schemes into large “superfunds” and offering support for voluntary industry-wide commitments to back UK companies; and (2) deregulation of share listing and trading regimes, including by simplifying the prospectus documents and reforming equity research.[35] Earlier, the Listing Rules became the subject of deregulatory proposals by offering changes that would 243simplify the listing regime to make company listings more accessible than before and support the competitiveness of London as a listing venue. In December 2021, the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), the UK’s main regulator for financial services firms and financial markets, introduced rules that would loosen the currently strict regime on the use of dual-class shares and the minimum free float of shares in public hands.[36] Furthermore, the FCA launched a consultation on detailed proposals on the reform of listing rules in late December 2023.[37] The new rules, which came into force at the end of July 2024, include, among others, provisions on removing the distinction between premium and standard markets and simplifying the rules on advance shareholder approval for large transactions.[38] There is progress in changing rules on compensation as well. As a first move, UK regulators removed at the end of October 2023 the bankers’ bonus cap introduced in the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis.[39]

In pursuit of this deregulatory vision, the UK government withdrew its proposal on imposing additional reporting requirements on large companies in mid-October 2023.[40] The draft regulations, published just three months before the withdrawal, would have added additional corporate and company reporting requirements for large UK listed and private companies, including an annual resilience statement, distributable profits figure, material fraud statement, and triennial audit and assurance policy statement.[41] As explained in the press release announcing the withdrawal of the draft regulations, they “would have 244incurred additional costs for companies by requiring them to include additional layers of corporate information in their annual reports.”[42] Consistent with the Government’s new policy to streamline and simplify regulation for businesses, the Financial Reporting Council (FRC), the body responsible for regulating the audit industry and for setting the best practice corporate governance and investor stewardship standards, announced in early November 2023 plans to withdraw most of the proposals that it had set out earlier in connection with the comprehensive review of the UK Corporate Governance Code.[43] Among the dropped proposals were plans to strengthen existing standards on diversity and over-boarding, to add new environmental, social, and governance (ESG) responsibilities for audit committees of corporate boards, and to set an expectation of regular engagement by board chairs with large shareholders.[44] Notably, there seemed to be disagreements among regulators on the need for deregulation as a means to revive UK listed companies. While the Government used the overly positive language of cutting costs for business as a justification for abandoning its reform proposals,[45] the FRC’s press release announcing policy updates expressed disappointment and hope that these reforms would be implemented later because of the need to “restore investor and public trust following the very damaging collapse of several high-profile businesses.”[46]

As we explain next, whilst deregulation may play a role in increasing the attractiveness of the London market, these proposals are unlikely to have any meaningful role in reversing the declining trend on the London stock market because none of the reasons that they target are the likely root cause for the market’s decline.

III. The Overlooked Role of Tax in the Rise and Decline of the London Equity Market

A major reason for the declining relevance of London’s equity market – and one that is largely absent from the discourse – is related to rule changes in the taxation of dividend income. The only existing study that explicitly links the 245current state of the UK equity market to tax changes is a policy paper published recently by Tony Blair Institute for Global Change.[47] This section shows that tax incentives related to income derived from dividends encouraged the flow of funds from pension schemes and insurance companies into domestic equities in the UK starting from mid 1970s, thereby contributing to the growth of the equity market. The repeal of the preferential treatment of dividend income from shares held by pension funds and the pensions business of insurance companies towards the end of 1990s marked the beginning of the opposite trend of outflows of the savings of local investors from UK equities. Following the repeal of the tax incentives, major classes of local institutional investors all but disappeared from the ownership of UK equities, leading to the decline of the market. These tax incentives can explain not only changes in the ownership structures of UK listed companies, but are also likely to have contributed to the other key features of the UK equity market: the strong investor preference of dividend payments over share buybacks and, perhaps more importantly, over the reinvestment of corporate profits in growth. The fact that tax rules can have an important impact on the attractiveness of a market is of course wholly unsurprising. AIM, the “junior” market operated by the LSE, for instance, offers significant and controversial tax benefits to investors[48] – something that has long been marketed by investment firms as a key advantage of investing in AIM-traded firms.[49] This tax treatment likely distorts investment choices of individual investors.[50]

1. Introduction to the UK’s Partial Imputation System of Taxation

Except for a short period between 1965 and 1973 when the United Kingdom had a “classical” taxation system, the post-World War tax rules in the UK offered some form of tax relief for dividend income.[51] The “classical” taxation system 246involves applying two layers of tax on the income, once at the corporate level and again, a second time, as dividend income at the shareholder level. By contrast, under the so-called “partial imputation system” which was introduced in 1973 to replace the “classical” system of corporation tax, shareholders received credit against their income tax liability on dividend income.[52] After the repeal of high taxes on dividend income introduced during and after the two World Wars, the partial imputation system turned into powerful incentive encouraging investments in the shares of local companies by major UK-based institutional investors. The rest of this sub-section introduces the workings of the UK’s partial imputation system of taxation. This introduction sets the scene for explaining the impact of tax rules on the incentives of institutional investors to invest in the shares of UK-listed companies in the following sub-section. As shown below, there are strong reasons for linking the rise and the relative decline of the London stock market with the UK’s partial imputation system of dividend taxation.

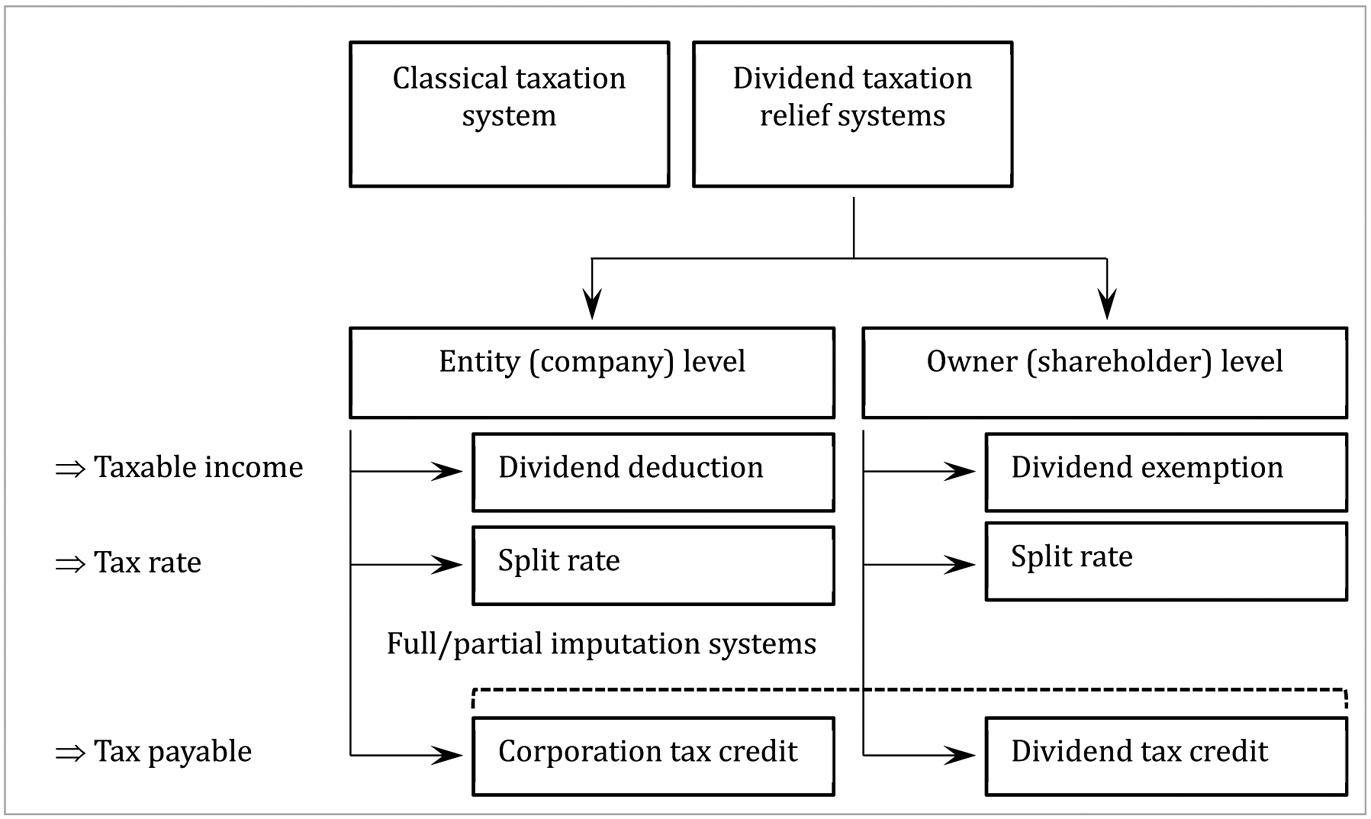

The peculiarity of corporate income under tax rules is that it is treated as income twice: once when it is derived and again when it is distributed.[53] Taxing both events, which is common practice in most countries, results in the economic double taxation of corporate income unless specific relief is provided.[54] The imputation system of dividend taxation imposes income tax at the entity level but reconciles it with owner-level income tax to mitigate this double taxation problem. It is thus an intermediate model between pure entity taxation (the classical system), where corporation income tax is paid entirely separate from owner-level taxes on dividend income, and pure pass-through (or flow-through) taxation, where tax is paid only at the owner level.[55] There are different forms of imputation systems depending upon the availability of tax relief at the corporation or at the shareholder level and upon the adjustment made to taxable income, the tax rate, or the tax result.[56] The chart below illustrates the types of dividend relief (Figure 3). At the shareholder level, dividend income can be partly or fully excluded from the income tax base;[57] can be taxed at a lower rate compared to other income;[58] or can entitle shareholders to a full or partial per247sonal tax credit for the profits that have been taxed at the corporate level.[59] At the corporate level, tax rules can allow companies to deduct dividends paid from taxable profits,[60] impose a lower rate on dividends compared to retained profits,[61] or offer corporation tax credit.[62] The UK’s partial imputation system adopted the latter form by offering a tax credit at the corporate level. This system aimed to mitigate, but not eliminate, the double taxation of corporate profits arising under the classical system by offering a refundable tax credit related to dividend income to partly reduce the tax due to be paid by the company.[63]

Types of Dividend Taxation Systems

Under this partial imputation system, when a UK resident company paid dividends, it was also required to make a payment amounting to a certain percentage of the dividend paid. This payment was credited against the company’s regular (or “mainstream”) corporation tax liability due after the end of the financial year, thereby functioning as an advance payment of corporation tax.[64] To prevent double taxation, dividends carried with them a refundable tax credit 248at the rate equal to the advance corporate tax rate. This refundable tax credit was offset against the corporate income tax.[65] A shareholder that was exempt from the tax on dividend, like UK pension funds, could reclaim the tax credit from the government for dividends paid by UK resident companies.[66] The role of the advance tax payment by companies then was to make sure that the tax credit represented tax that had actually been paid by the company (even in cases where the company, for different reasons, did not have corporation tax obligations). As a result, the advance corporation tax payment was effectively equivalent to a dividend withholding tax imposed on shareholders but paid by companies as their tax agent.[67] Importantly, dividends paid by overseas companies that were not UK residents for tax purposes did not carry a tax credit since non-residents did not pay corporation tax in the UK. Neither did non-resident shareholders receive a tax credit for dividends paid by UK resident companies unless these shareholders could rely on a double taxation treaty.[68]

In April 1973, following a short experiment with a classical income tax system, the UK re-introduced rules giving all shareholders tax relief on dividend income in recognition of corporation tax paid by companies.[69] In practice, the UK’s partial imputation system had different implications for taxpaying and tax-exempt shareholders. Taxpaying shareholders generally ended paying lower income tax liability on dividend income. For example, an individual shareholder who was a basic-rate taxpayer paying tax at the standard (i.e. the lowest) rate of income tax did not pay any income tax on dividends because the rate of the advance corporation tax payment was set equal to the basic rate of income tax on dividend income.[70] But the tax credit did not completely offset the income tax liability of higher-rate taxpayers who needed to pay more – the so-called “top up tax” – to cover the positive difference between their tax obligations under the higher rate of income tax and the tax credit.[71] By contrast, tax exempt shareholders received cash payments from tax authorities as a refund of 249the tax paid at the corporate level when the company distributed profits.[72] This group of tax exempt shareholders predominantly consisted of pension funds and the pension component of insurance companies.[73] Importantly, the pension component was a major part of the business of insurance companies in late 1980s: over half of insurance premium income was related to the pension business of insurance companies, according to the estimates of the Association of British Insurers.[74] Accordingly, a significant portion of insurance company investments in equity markets were financed by pension savings contributed to insurance policies.[75]

During the late 1990s and early 2000s, several countries, especially in Europe, abandoned the partial imputation system of dividend taxation in favour of other forms of tax relief, such as the adoption of lower rates for dividend taxation.[76] The main reason for this change in the EU countries was the threat that the European Court of Justice would treat partial imputation systems, due to their effectively preferential treatment of domestic investors and domestic investments, inconsistent with the EU’s right to the free movement of capital.[77] Consistent with these global trends, the UK’s imputation system of dividend taxation was relaxed over time and was abandoned completely in 1999 after the incoming Labour government repealed it in 1997. These radical reforms had good intentions that went beyond the need to comply with the EU law. High levels of dividends paid by UK companies, which arguably reduced the funds available to companies for reinvesting in growth, were a major concern at the time and the driving force behind the reform of dividend taxation.[78] Tax ex250empt institutional investors were believed to be forcing companies to maintain high dividend payments and were thus seen as potentially distortive.[79] The intended objective of the reforms was thus to make powerful tax exempt institutional investors indifferent between dividend payments and retained earnings.

These reforms were implemented in two major steps. In April 1993, the UK government reduced the rate of the refundable dividend tax credit.[80] The effect of the rate change on shareholders depended on their position. Nothing changed for basic-rate taxpayers because changes in the rate of dividend tax credit were matched by changes in the rate of advance corporation tax paid by companies.[81] But taxpayers that could reclaim a repayment of tax credit from the government – UK pension funds among them – were hit the hardest because the size of the available tax refund fell.[82] The partial imputation system and the dividend tax credit associated with it were abolished entirely during the Labour government reforms that began in 1997 and were completed in 1999.[83] The reform “retained the shell of the imputation system.”[84] In place of the partial imputation system, the UK introduced a mixed shareholder level relief system of taxation of dividends by combining a dividend tax credit with reduced tax rates for dividends. Under this system, which remained effective until April 2016, shareholders received a tax credit, calculated as a percentage of the amount of corporate distributions, that was used to reduce the shareholder tax payable on the dividend at the reduced dividend rates.[85] The key practical difference of this system from the old one was that dividend tax credits could not reduce the taxpayer’s income tax liability accrued through other income, nor would they be entitled to an outright refund from HMRC.[86] After 1997, according to the leading treatise on UK tax law, “there was virtually no right to repayment, whether the shareholder was a UK pensioner with low income, a charity, a pension fund or most types of non-resident.”[87] This feature made the new system considerably less favourable for tax exempt shareholders like pension funds and the pension component of insurance companies. From 6 April 2016, the last remnants of the imputation system were removed. The tax credit was abolished and instead all individuals were given a capped tax-free amount 251of dividends; dividends above this amount are taxed at different rates depending on the taxpayer’s tax band.[88]

An important feature of the UK’s partial imputation system was the availability of tax relief only for the part of company profits that was paid out to shareholders in the form of dividends.[89] There was no relief of corporation tax paid on retained profits at the level of the company or its shareholders.[90] As a result, the UK’s partial imputation system, perhaps unintentionally, made it harder for companies to retain profits. The rules created incentives for tax-exempt shareholders to encourage companies to pay more dividends than they would otherwise pay in the absence of tax distortions. By contrast, high-rate taxpayers disfavoured dividend payments and might, instead, want companies to retain and reinvest profits in growth.[91] Note that UK company law prohibited share buybacks by companies until the early 1980s.[92] This effectively meant that the only option shareholders had to participate in the distribution of profits was through the declaration and payment of corporate dividends.

2. The Effect of Dividend Taxation on UK Investors and Equity Market

In this section we address two questions. First, why have domestic pension funds and insurance companies stopped investing in the UK equity market? Second, how has the retreat of these investors from UK equities contributed to the decline of the UK equity market? Answers to these questions pave the way for the discussion of how this trend can be reversed. We deal with the follow up question of whether the proposed or other reforms can address the problem of the declining UK equity markets in the following section.

The UK’s partial imputation system of taxation, combined with dividend tax exemptions for UK pension funds and the 252pension component of insurance companies, created strong incentives for tax exempt investors to invest in the shares of UK tax resident companies. The right to reclaim the dividend tax credit from the government meant that dividends received by these investors were effectively higher than the dividends paid by the same company to all other non-tax-free shareholders. This tax-driven implicit subsidy made investments in the UK stock market more attractive for UK pension funds and the pension component of insurance companies compared to investments abroad and to investments in other asset classes. From the perspective of UK companies raising equity capital, the impact of the implicit subsidy was to reduce the cost of capital by increasing tax-exempt investors’ expected returns on the investments. This encouraged companies to offer their shares to tax-exempt shareholders by listing on the UK equity market. A similar imputation system of dividend taxation in Australia has, arguably, increased the appeal of dividends for Australian superannuation funds and turned these funds into one of the most significant holders of Australian equities.[93]

The reduction of the rate of dividend tax credit in the UK in 1993 had the opposite effect, and reduced the size of dividends paid by UK resident companies for tax-exempt institutional investors.[94] The reduced rate meant that these investors could claim lower tax refunds from the government. This, in turn, made the shares of UK listed companies less attractive for those investors. Tax-driven incentives of pension funds and insurance companies to invest locally started to weaken gradually and were eliminated altogether after the complete repeal of the dividend tax credit in 1997. This last reform reduced the value of dividend income on UK for by previously tax-exempt institutional investors by 20%.[95] Tax-exempt investors had fewer reasons to overinvest in UK equities after the reform. As a consequence, the two most significant sources of capital for investments in UK listed shares lost a major financial incentive for investing in UK equity markets. The repeal of the tax incentive levelled the playing field between UK equities and alternatives, such as foreign equities or other asset classes. In the absence of the distortive tax support, UK pension funds and insurance companies had no reasons not to allocate more capital to foreign markets and/or fixed-income instruments.

Historical ownership patterns of UK listed shares by pension funds and insurance companies show striking correlation with the expected outcomes of tax rules. As illustrated in Figure 4, the ownership of UK shares by pension funds expanded quickly after the introduction of the tax relief and peaked during the early 1990s. The first wave of divestment from UK equities by pension funds started right after the dividend taxation reforms of 1993 and continued after 1997 when the last remnants of the dividend tax relief were being repealed. The 2008 global financial crisis, for the reasons explained below, was the final straw that almost eliminated UK equities from the portfolio of pension funds. Similarly, insurance companies were major holders of UK equities in the period 253from mid-1970s until mid 1990s, but gradually left the market after the start of the Labour government’s tax reforms.

Ownership of UK Quoted Shares by Domestic Pension Funds and Insurance Companies

Brian Cheffins and Steven Bank rely on a study by the Institute of Chartered Accountants of England and Wales to document the historical rise of pension funds and insurance companies. The percentage of shares held by pension funds grew from 1% in 1957 to 17% in 1975 and 31% in 1991.[96] Insurance companies, similarly, increased their share in the ownership structure of UK companies from 8% in 1957 to 16% in 1975 and 20% in 1991.[97] Other sources, offer corroborating evidence.[98] According to John Scott’s study of the ownership structures in the largest 250 UK financial and non-financial companies, both publicly traded and privately held, almost half of the top 20 institutional investors in 1976 were insurance companies, such as Prudential Assurance, Cooperative Group, Legal & General Assurance, Norwich Union Insurance, Pearl Assurance, Royal Insurance, Commercial Union Assurance, Britannic 254Assurance, and General Accident.[99] These investments were primarily financed by pension savings contributions to insurance policies.[100] The list of top institutional investors included several large pension funds too: National Coal Board, Electricity Council, and ‘Shell’ Transport & Trading.[101] Figure 5 uses data from the Office for National Statistics to show that in 1969, pension funds and insurance companies together owned only 21.2% of the total equity in stock market quoted companies in the UK. Their combined holdings jumped to 32.7% already in 1975 and continued to increase steadily over the next decade and half to exceed 52% in 1991. During the four peak years of 1990-1993, UK-based pension funds and insurance companies together held more than half of the shares of the total market value of all UK quoted companies (Figure 5). By contrast, today the two together own less than 5% of the shares of UK quoted companies, thereby leaving the UK equity market with “no natural investors,” as described by one fund manager.[102] The modern UK stock market, as shown in Table 1, is dominated by overseas investors and domestic pooled investment funds.

Ownership of UK Quoted Shares by Different Investor Types

255Ownership of UK Quoted Shares by Different Investor Types, %

| Investor Type | Year | |||||||

| 1963 | 1975 | 1989 | 1998 | 2008 | 2018 | 2022 | ||

| Insurance companies | 10.0 | 15.9 | 18.6 | 21.6 | 13.4 | 3.9 | 2.6 | |

| Pension funds | 6.4 | 16.8 | 30.6 | 21.7 | 12.8 | 2.2 | 1.6 | |

| Overseas investors | 7.0 | 5.6 | 12.8 | 30.7 | 41.5 | 55.7 | 57.7 | |

| Individuals | 54.0 | 37.5 | 20.6 | 16.7 | 10.2 | 13.3 | 10.8 | |

| Banks | 1.3 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 3.5 | 2.1 | 3.4 | |

| Pooled investment funds | 12.6 | 14.6 | 8.6 | 6.0 | 13.7 | 18.9 | 21.0 | |

| Public sector | 1.5 | 3.6 | 2.0 | 0.1 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 0.6 | |

| Charities | 2.1 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.7 | |

| Private non-financial companies | 5.1 | 3.0 | 3.8 | 1.4 | 3.0 | 2.1 | 1.8 |

Source: Office for National Statistics

Clearly, the introduction of the tax relief on dividend income paid by UK tax resident companies in 1973 encouraged the flow of pension savings into the London equity market. According to a 1977 survey by The Economist, “the enormous advantages of institutional saving” were a key reason explaining the overwhelming dominance of institutional investors in the UK’s stock markets.[103] Similarly, the revocation of the tax relief in 1999 contributed to the outflow of these funds from the UK equity market.[104] Remarkably, pension funds in Australia, which is one of the few countries in the world that continues to operate a partial imputation system of dividend taxation,[105] allocate a much higher portion of their assets to domestic equities.[106]

After showing that tax played a major role first in the inflow of the funds of UK institutional investors into the UK equity market and later in the outflow of these funds from the market, the next step is to establish a link between the fund flows and the state of the UK equity market. The retreat of domestic shareholders from the UK equity market does not necessarily entail the decline of the market. One could argue that in global financial markets the exit of a group of domestic investors, even if those are the largest in the market, is not a major concern for a national market if the net inflow of foreign capital can fill 256the financing gap. Indeed, foreign capital inflows are likely to have an impact on equity markets,[107] and, as shown in Table 1, overseas investors naturally did increase their relative holdings in UK company shares over time, especially after early 1990s.

It is a standard assumption in corporate finance that in efficient markets that are completely integrated, assets with the same risk have identical expected returns (and therefore prices) irrespective of the market where they trade.[108] Accordingly, if a high required rate of return increases the cost of capital for UK listed firms, it would be because of different market risk exposure, rather than the exit of specific investors. But national stock markets, due to the presence of various frictions on the global flows of capital, are not completely integrated. For example, (self-imposed) restrictions on country-specific investments in the target portfolio allocation strategies of funds may cap capital inflows into markets outside their home countries. If the mismatch between the numbers of selling and buying investors (outflows and inflows) is large, capital flows may have an impact on equity returns and thus the cost of equity capital of firms listed on a market. This means that, even if we disregard the obvious effect of the UK’s dividend tax credit on the cost of capital of UK companies, foreign fund inflows may not necessarily be sufficient to fill the void created by the outflows of the funds of local pension funds and insurance companies. In other words, while it is evident that overseas investors replaced UK pension funds and insurance companies as the largest holders of UK equities, it is far from clear that the supply of financing from overseas investors was sufficient to fully offset the effect of outflows.

In any case, even if foreign investments after the retreat of domestic pension funds and insurance companies led to net capital inflows, these investments could not compensate for the subsidising and distortive effect of the dividend tax credit on the cost of capital of UK companies. Dividend tax refunds available to tax-exempt investors increased the return that they expected to receive on their investments in UK equities, thereby lowering the cost of capital for UK companies. This encouraged more companies to list publicly which, in turn, increased the market size (both in terms of the number of publicly traded 257companies and the total market capitalisation). Changes in the taxation of dividends coupled with the outflow of the funds of UK pension funds and insurance companies from the market contributed to the decline of London’s equity market by increasing the cost of capital for UK listed companies.

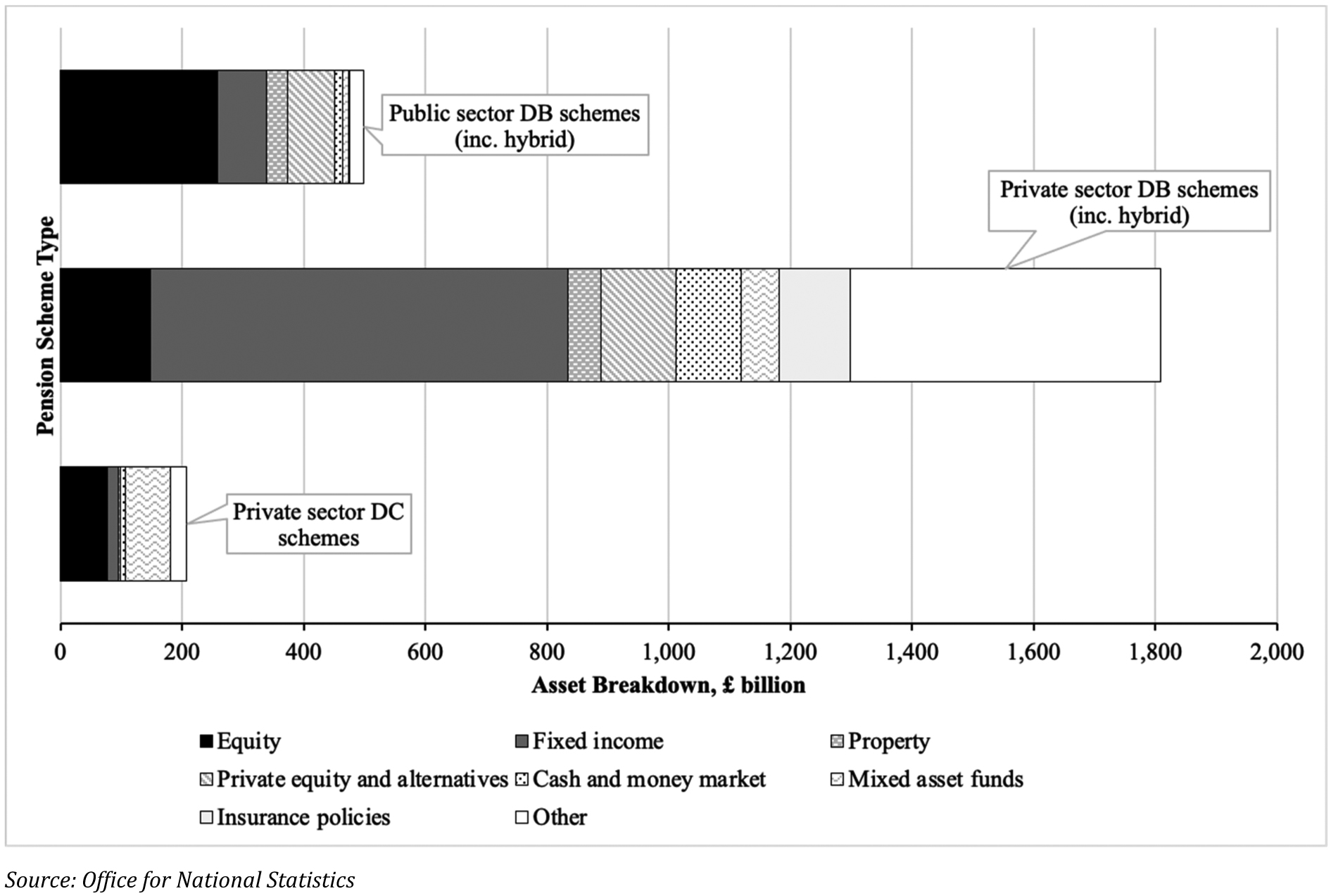

Importantly, the shrinking trend in the UK equity holdings of pension funds and insurance companies is not the result of the relative decline of the overall assets of these two investor classes in capital markets or a general move away from riskier equity markets to less risky assets, such as fixed income or money market funds. The share of pension fund and insurance company holdings in UK equities has declined because of the outflow of capital from the UK equity market and reinvestment of this capital both in fixed-income markets or overseas equity markets. At present, UK insurance companies and private defined benefit (DB) pension schemes – the largest category of pension schemes in the country by assets – allocate a small portion of their assets to equities and even smaller share to UK equities (below 5% of total assets).[109] Even defined contribution (DC) pension schemes, which have a different risk preference and invest more than half of their assets in equities, have only around 13% of their assets allocated to the UK equity market.[110] (See also Figure 6 below.) Both pension funds and insurance companies reduced their asset allocation to UK equities substantially, while keeping allocation to non-UK equities relatively stable.[111] The trend illustrated above in Figure 4 is thus a targeted move out of UK equities.

Of course, the evidence on the gradual exit of pension assets from UK equities shows only correlation with changes in the taxation of dividend income. Our analysis does not offer empirical evidence showing that changes in tax rules caused the inflows and outflows of funds into and from equities. Neither does it rule out the role of other contributing factors in the rise and decline of the London stock market. Certainly, there were other factors that contributed to the decline of the UK equity market.[112] In a policy paper published in May 2023, the experts of Tony Blair Institute for Global Change attribute the dire state of the UK equity market to the above-mentioned reforms in dividend income taxation and to a technical change in the accounting of pension assets and liabilities.[113] The latter receives noticeably more attention in the report and 258is the primary target of the paper’s policy and law reform proposals. At the beginning of 2005, following a long transition period, the UK Accounting Standards Board introduced the so-called “FRS 17” accounting requirements for retirement benefits, according to which (1) pension scheme assets were measured annually using market values and (2) future pension liabilities would be discounted by a fluctuating rate of a highly ranked corporate bond.[114] Previously, companies estimated pension liabilities based on the investment strategy of the pension scheme; if the scheme invested most of its assets in equities, higher expected returns from equities could be taken into account when calculating the scheme’s net pension liabilities.[115] This change, like the dividend taxation reforms, was well-intended: its goal was to make pension savings in employer-run private DB schemes safer than before.[116] But the new rules, coupled with unprecedented period of ultra-low interest rates for corporate borrowers, created enormous accounting liabilities on the balance sheets of large companies with in-house corporate DB pension schemes.[117] Accounting experts predicted that this change would encourage companies to close their DB pension schemes to new members and, instead, offer new employees only DC pen259sions.[118] Furthermore, to reduce the exposure of pension schemes to interest rate fluctuations, companies would change the investment strategy of pension schemes by moving holdings from equities into corporate and sovereign bonds.[119] It is clear now that both predictions proved to be right.[120] The disastrous impact of this reform for the balance sheets of companies with in-house DB pension schemes was fully appreciated during the 2008 global financial crisis, when the dual effect of low equity valuations and low interest rates created large pension scheme funding gaps. This, as illustrated in Figure 4 above, added more pressure on corporate DB schemes to divest quickly their remaining equity investments after 2008.

The impact of these accounting changes, although important in affecting the future and the investment strategy of corporate (private) DB schemes, especially after the risks of the 2008 global financial crisis, should not be overstated. They mattered only for private DB schemes and cannot explain changes in the investment strategies of public DB pension schemes, such as local government pension funds, and of the growing segment of DC pension schemes. Calculations based on the latest data on funded occupational schemes from the UK’s Office for National Statistics reveal that both public DB schemes and private DC schemes allocate substantial portion of their assets to equities and to private equity and alternative funds (Figure 6). Yet, like corporate DB schemes, these pension schemes have reduced their allocation to UK equities over the past two decades.[121] It is, of course, possible that some UK companies have become less attractive as investments relative to their foreign peers because they needed to direct funds into corporate pension schemes to cover scheme liabilities instead of investing in innovation and growth.[122] But again, this explanation cannot be extended to all UK corporate sector. Furthermore, the exodus of UK pension money from domestic equities, as shown in Figure 4, started long before 2005 when the accounting changes were introduced. All these factors suggest that changes in the taxation of dividend income have had a major, if not the most decisive, impact on the investment preferences of the overall UK pension fund sector. The tax relief should not be underestimated lest omitted during the discussions on how to revive London’s equity market.

260Asset Allocation of Funded Occupational Pension Schemes in the UK, Q1 2023

Existing empirical evidence offers some support for the link between the UK’s dividend income tax relief and corporate ownership structures. Helen Short and her co-authors show a positive association between the dividend pay-out ratios of companies listed on the LSE during the functioning of the partial imputation system and the levels of institutional ownership.[123] Furthermore, a study by Leonie Bell and Tim Jenkinson shows that pension funds and other tax-exempt shareholders predominantly invested in UK equities that offered high dividends.[124] Based on their findings, they correctly predicted that the withdrawal of tax credits for dividend income in mid 1990s would, over time, lead to significant changes in the corporate ownership structures of British companies in the form of a gradual shift of the shareholdings of pension funds from high dividend yielding shares of UK companies to other shares.[125]

The declining UK equity holdings of pension funds and insurance companies is a significant factor that should not be ignored. The UK has more than £5 261trillion in pensions and insurance assets.[126] UK pension schemes alone have £2.13 trillion in assets according to Figure 6 above, of which £233 billion are in private sector DC schemes (invested almost exclusively through pooled investment vehicles), close to £500 billion are in public sector DB schemes (invested both directly and through pooled investment vehicles), and almost £1.4 trillion are in private sector DB schemes (invested mostly directly, but also in pooled investment products and insurance policies). This is a deep pool of savings money that has left the UK equity market and, most likely, has had a major impact on the market’s stagnation over the past decade.

The last point to address in this section is the impact of the UK’s partial imputation system of corporate taxation on investments in a longer historical perspective. The careful reader may note that the UK had a form of dividend taxation relief before 1965 as well. Until that year, companies deducted income tax at the assumed standard rate from dividends but did not need to pay the deducted amount to the Inland Revenue.[127] Companies retained this money and could use it to pay corporation tax.[128] A logical question then is why pension funds did not invest in the shares of local companies, at least at a rate similar to the post-1973 period, before 1965. There are three major reasons that explain different behavioural patterns of pension funds and their relatively small equity holdings prior to 1965. First, various tax levies introduced on corporate profits during and after the two World Wars to finance the wars and post-war recovery discouraged investments in company shares. These levies were imposed on corporate profits before distributions, thereby taxing ordinary shareholders.[129] They were repealed after World War II, but UK tax laws had an explicit tax bias against dividends in place between 1947 and 1958. The corporate income tax rate on distributed profits was double of the rate on undistributed profits.[130] This policy was explicitly designed to discourage dividends.[131] Indeed, historical estimates of average dividend tax rate weighted by the distribution of share ownership show that prior to 1965, UK tax rules imposed a substantial tax burden on dividends.[132] As a result, notwithstanding the presence of tax relief for dividends prior to 1965, tax laws discouraged investments in corporate shares, thus supressing buy-side demand. Holding corporate shares was an unattractive means of investing income. Tax bias against divi262dends continued in the period between 1965 and 1973 when the application of the classical income tax system meant that corporate profits were taxed twice: once at the corporate level and once again at the shareholder level.[133] The view that companies should be encouraged to retain their profits rather than distribute them to their shareholders was the basis of this classical system.[134] Tax incentives changed dramatically after April 1973 when the partial imputation system was back with strong incentives for tax exempt shareholders – like pension funds and the pension component of insurance companies – to invest in shares. Corporate dividends became an attractive source of income which, in turn, strengthened the buy-side demand for shares issued by UK tax resident companies.

Second, pension funds and insurance companies were also relatively small before 1950s. It was only during the following two decades that these two types of investors increased their assets under management tremendously and became a powerful force in capital markets.[135] Pension provision was almost absent in the 19th and early 20th centuries, even among employees at the managerial level: “direct occupational support tended to be in the form of discretionary payments provided only to ‘deserving’ individuals, usually to long-serving men of ‘good character.’”[136] The shift from discretionary support to formal occupational pension provision started in 1920s, but the increase in the number of pension funds was slow, partly because employers did not need to offer benefits in addition to salary to attract and retain employees in the conditions of high unemployment and recession.[137] The expansion of pension schemes started only after the Second World War.[138] With more employees being covered by company pension plans and the popularity of life insurance products among the British public, the investments of pension funds and insurance companies in the shares of UK listed companies became distinctly visible.[139]

Third, and perhaps most substantially, under the pre-1965 system of dividend taxation, companies deducted income tax at the assumed standard rate of 30% for all dividends.[140] All shareholders – whether paying income tax at a standard (or higher) rate or being tax exempt – were treated equally for income tax deductions from dividends. This feature of the pre-1965 tax rules did not offer 263pension funds additional incentives to invest in shares compared to any other shareholder.

3. The Ancillary Consequences of Dividend Taxation for the UK Equity Market

Turning to the question on how the declining investments in UK equities can be reversed, it is important to emphasise that the analysis above does not imply that the UK government should bring back the preferential tax treatment of dividend income, even if doing so would likely encourage pension funds (and other institutional investors) to support the growth of the economy and stock market by investing locally. To start with, tax subsidies result in an obvious loss of tax revenue and thus may be hard to justify for a government constrained by budget limits. Furthermore, tax incentives and exemptions, powerful and effective though they may be, are costly and create market distortions that can have long-lasting, often negative, impacts. It is well known that the costs of preferential tax treatment of certain activities or sectors relative to other unaffected taxpayers go beyond the immediate loss of revenue through the erosion of tax base and also include distortions to resource allocation and business decision-making, administrative costs from running the scheme and preventing its fraudulent use, and increased opportunities for corruption and socially unproductive rent-seeking behaviour.[141] Clearly, there are then trade-offs associated with encouraging investments in local stock markets through tax incentives.

Indeed, the UK’s partial imputation tax system not only possibly encouraged more local investments by pension funds and the pension component of insurance companies but can also be used to explain other features – or anomalies – of the UK stock market. The (re-)introduction of tax relief for encouraging pension funds to invest in growth companies and UK company shares in general then is a policy decision based on the trade-offs of preferential tax treatment schemes and the preferences of policy makers.[142] It is, however, impor264tant to acknowledge that the long-run development of the London equity market is partly a function of changing tax policy. As argued above, the removal of a likely distortive tax subsidy has contributed to the decline of the UK stock market. Benchmarking against historical data is therefore complicated by what may best be described as an inflated baseline. It is the aim of this paper to highlight this fact, and it is submitted that reforms focussing only on deregulation are unlikely to reverse the effects of a changing tax landscape.

The tax relief on dividend income paid by domestic companies can explain the preference of traditional UK fund managers for dividends over share buybacks and, perhaps more importantly, over the reinvestment of profits in growth. According to Paul Marshall, many UK fund managers give priority to dividends over growth.[143] In the United States, profits distributed as dividends are taxed more heavily than retained profits; whereas lower capital gains taxes also make share buybacks more attractive from shareholder perspective than dividend payments.[144] By contrast, the tax relief for dividend income introduced by the UK’s 1973 partial imputation system created a clear and strong tax preference for dividends for certain powerful tax exempt investor classes.[145] This scheme’s tax bias created incentives for pension funds and the pension component of insurance companies to demand high dividends from investee companies.[146] As a result, companies were likely to pay more dividends than they would in the absence of the tax bias.[147] Available empirical studies support these claims. Poterba and Summers use data on British companies to show that the UK’s transition from the classical system of dividend taxation to the partial imputation system in 1973 changed the valuation of dividends by shareholders, thereby making dividend income more attractive than before.[148] Bell and Jenkinson show that pension funds and other tax exempt shareholders preferred investments in high dividend yielding UK equities which, in turn, influenced the dividend polices of UK companies.[149] Similarly, Lasfer shows that a lower tax burden on dividends after 1973 encouraged UK companies to pay higher dividends.[150] Moreover, companies considered the tax position of their shareholders when setting their dividend policy by, for example, paying more dividends when tax exempt investors dominated the corporate ownership struc265ture.[151] Last, Helen Short and her co-authors show a consistent positive association between the dividend pay-out ratios of companies listed on the LSE during 1988-1992 and the share of institutional investors in their ownership structure.[152] As explained above, the tax relief also made more attractive for these investors to invest in UK company shares.[153] These two factors combined to create a cycle where the prospect of high dividend payments and tax credit encouraged more pension fund investments in the local stock market and the growing clout of these investors as shareholders put an increasing pressure on corporate managers to pay more dividends. Indeed, along with the emergence of pension funds as the most influential investors in many UK companies in the 1980s and early 1990s, dividends paid by UK listed companies increased compared to other developed countries.[154]

The expectation that the dominant institutional investors demand more dividends has turned into a strong-form market norm over time. As a result, companies are finding it hard to scale back dividend payments even long after the repeal of the dividend tax relief. If the distribution of dividends is taxed, corporate actors can be reasonably expected to have a preference for retaining profits over paying dividends. This incentive to retain corporate profits is the strongest under a classical corporate tax system where the distribution of dividends is fully taxed.[155] Nevertheless, almost 15 years after the repeal of the tax relief on dividends, the UK’s FTSE 100 index still has a dividend yield that tends to be higher than in many other major developed markets,[156] even though this is likely also a consequence of the types of businesses traded in the London market. A bias towards dividend distributions may limit their access to low-cost internal funds, thereby reducing the growth opportunities of UK companies vis-à-vis their overseas competitors.

IV. 268Policy Implications

The key policy implication of the analysis above is not then that the UK needs tax exemptions that would encourage the flow of pension savings into the 266country’s stock market. Because preferential tax regimes in general reduce tax revenues and create many inefficient distortions with long-term consequences, extreme care is needed before they are re-introduced. It may be a better policy decision not to re-introduce tax exemptions to avoid market distortions. Rather, this analysis highlights the limited role of other law reforms and reform proposals under consideration, such as changes in corporate governance arrangements and listing rules, as opposed to tax incentives. Reforms will succeed in reviving the London stock market if they address the root causes of the exit of pension assets from the equity market. If tax reforms had a substantial impact on the outflow of pension funds from the UK equities, then deregulatory governance and listing reforms can have only limited impact on drawing pension assets back to the UK stock market.

The UK government unveiled a plan to reinvigorate the City of London in December 2022, also known as Edinburgh Reforms.[157] Part of these plans, such as the repeal on the cap for banker bonuses, have already been formally implemented. On the one-year anniversary of the UK government’s reform plan, the House of Commons Treasury Committee released a report criticising the speed of action.[158] The parliamentarians called on the City Minister to speed up the pace of delivery of the Edinburgh Reforms, including the proposed changes in the listing rules. The government needs “to be absolutely relentless in . . . completing the things that were set out,” according to the parliamentarians.[159] Our analysis shows that even the “relentless” implementation of all proposals included in the government’s plan are unlikely to be enough to reinvigorate London’s stock market. They are likely to have a mild impact on revitalising London’s stock market because more important causes of the decline of the market lie elsewhere. This means historical comparisons may be misleading in assessing the latest reforms. According to the head of one bank’s European IPO business quoted in The Economist, he is “unaware of any company choosing an IPO venue based on its listing rules.”[160] Instead, the primary considerations of this bank’s clients are the amount of money they can raise and the readiness of local investors to support their business.[161] Both are factors directly connected with the changes in the taxation of dividends. The di267vidend tax credit was an implicit subsidy to equity financing that lowered the cost of capital of UK companies. The removal of this subsidy had an obvious impact on the cost of capital that UK tax-resident companies could raise; it also possibly diminished the pool of capital available in the UK equity market after it was abandoned by UK pension funds and insurance companies. Deregulation and reforms in corporate governance and listing rules can neither lower the cost of equity capital of UK companies, nor are they sufficient to encourage British institutional investors to return en masse to the UK equity market (because these investors divested from the domestic shares for different reasons). The danger is that the temptation to explain the likely failure of these reforms by the limited scope of rule changes can create a self-fulfilling process of deregulatory reforms that will erode investor protections and disrupt the established governance mechanisms without any meaningful positive impact on stopping the diminution of the UK stock market. Instead, reforms should target proposals that can encourage pension funds to allocate more assets to UK equities by making these investments more attractive compared to opportunities elsewhere. The consolidation of fragmented pension schemes into “superfunds” can be the first, but not the only, necessary step. For one thing, more pension funds could afford investing directly in a broader list of asset classes, including in early-stage growth companies and private markets, through in-house management teams and negotiating better fees and terms for pooled investments because of a larger scale.

Similarly, the analysis in this paper does not imply that deregulation is unnecessary. Deregulation may be desirable for reducing costs for UK-based companies. Easing rules for listed companies can also remove the imbalances between the regulatory regimes of public and private companies that have distorted business organisation and financing decisions. But deregulation, as shown above, should not be marketed on the basis that it is needed to encourage more listings in London and reinvigorate the London stock market.[162]

To sum up, we need to introduce tax into the ongoing discourse on the reasons for the decline of the UK stock market to have a better understanding and more accurate tools for assessing options that we have for revitalising the market. Omitting tax as an important factor that has influenced the stock market risks ending up with reforms that can, at best, do little to change the current situation.

V. Conclusion

Tax has been overlooked as a factor explaining the decline of the London stock market. This absence is remarkable because tax experts have long recognised the “hugely influential” impact of the tax framework on the shape of pension provision in the UK.[163] Commercial and corporate lawyers themselves often joke – usually with an element of truth in it – that they always refer to tax reasons when clients ask difficult questions. Following this wisdom that there must be some tax reason behind every difficult business question, this article offers a new tax-oriented perspective explaining why the London stock market is where it is now. The preferential tax treatment of the dividend income of certain types of institutional investors introduced in the early 1970s and repealed in the mid 1990s first contributed to the UK stock market’s growth by implicitly subsidising financing via equity and encouraging the flow of the funds of these investors into the market, and subsequently led to the market’s decline as a result of the outflow of the funds of the two major classes of investors: UK pension funds and insurance companies. The key implication of this argument is that omitting tax as a major factor in the decline of the UK stock market risks ending up with reforms that can, at best, do little to change the current situation.

In this article, we focused on one aspect of taxation that influenced the incentives of UK pension schemes to invest in local shares. There are certainly other tax rules that affect broader markets and create global imbalances in share trading. For example, taxes on share trading introduced in various European countries (the UK, for example, imposes 0.5% stamp duty charge when buying shares) may be driving more trading to markets that do not have comparable taxes on share trading or can encourage retail investors to invest through collective investment schemes instead of direct share ownership. These tax rules remain beyond the scope of this article, but this is not to negate their potential impact on national equity markets.

Acknowledgement

We are grateful to Brian Cheffins, Alex Evans, Rita de la Feria, Alperen Gözlugöl, David Kershaw, Shukri Shahizam, and Andy Summers for invaluable comments and suggestions; the authors are solely responsible for all remaining errors and inaccuracies.

© 2024 the author(s), published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Frontmatter

- From London to the Continent: Rethinking Corporate Governance Codes in Europe

- Traditional and Digital Limits of Collective Investment Schemes

- The Sanctions Principles-Based Regulation: A Blueprint for a New Approach for the EU Sanctions Policy (Part I)

- Tax Reforms and the Decline of the London Stock Market: The Untold Story

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Frontmatter

- From London to the Continent: Rethinking Corporate Governance Codes in Europe

- Traditional and Digital Limits of Collective Investment Schemes

- The Sanctions Principles-Based Regulation: A Blueprint for a New Approach for the EU Sanctions Policy (Part I)

- Tax Reforms and the Decline of the London Stock Market: The Untold Story