Abstract

In this paper, we examine the relationship between terrorism and exports at the firm-level. We use a panel data of 301 firms listed on the Pakistan Stock Exchange and records of terrorist attacks in Pakistani cities from 1999 to 2014. By calculating city-level terrorism indices, the study reveals significant variations in the frequency of terrorist incidents both between cities and within cities over different time periods. Our panel regressions show that firm exports are correlated with terrorist attacks in the cities where the firms are located, and these correlations are statistically significant even when terrorism is lagged up to six years. Interregional spillover effects of terrorism are less pronounced. While a negative correlation can be found between firm exports and our terrorism indices, the correlation with domestic sales tends to be statistically insignificant. The findings shed light on the persistent link between local terrorism and firms’ international and domestic operations.

1 Introduction

Terrorism is a worldwide phenomenon. There have been major attacks since the early 1970s and the number of terrorist attacks has increased significantly since the beginning of the 21st century (Institute for Economics & Peace 2018). While the direct effects of terrorism are evidenced by numerous victims and their suffering, it also has indirect economic effects that may be intended or unintended by the terrorist perpetrators (Sandler and Enders 2008). Empirical studies provide evidence of negative macroeconomic effects of terrorism on investment and growth (Abadie and Gardeazabal 2003; Bandyopadhyay, Sandler and Younas 2014; Chen and Siems 2004; Choi 2014; Enders and Sandler 1996; Tavares 2004).

Macroeconomic research suggests that international trade could be a channel through which terrorism influences economic growth, as an increase in the number and intensity of terrorist attacks can adversely affect international trade. Empirical studies examining the relationship between terrorism and international trade at the macroeconomic level suggest that the empirical relationship between terrorism and trade is either negative or statistically insignificant (e.g. Bandyopadhyay, Sandler, and Younas 2018; Blomberg and Hess 2006; Egger and Gassebner 2015; Nitsch and Schumacher 2004). One explanation for these ambiguous results is that empirical studies in this area focus on macroeconomic relationships. Recently, Gaibulloev and Sandler (2023) have noted that one of the myths associated with terrorism is that terrorism has macroeconomic consequences for the countries that experience terrorist attacks. Gaibulloev and Sandler argue that the harmful effects of terrorist attacks dissipate with increasing distance from the site of the attack and may have little impact on a country’s overall economy. Significant local effects are quite compatible with small or insignificant macroeconomic effects. Thus, the lack of empirical evidence of a link between terrorism and international trade at the macroeconomic level does not necessarily mean that firms’ trade activities are unaffected by terrorism.

While previous macroeconomic research on the relationship between terrorism and international trade has provided valuable insights, our knowledge of the microeconomic links between terrorism and firms’ international trade activities is still limited, and it is still unclear whether the results of macroeconomic research based on aggregate country-level trade data can even be generalized to the microeconomic level, i.e. when using firm-level or region-level data. Empirical analyzes based on country-level data, for example, completely disregard regional differences in the number and intensity of terrorist attacks within countries. Some regions may be particularly affected by terrorism while others are not. Economic activity in provinces affected by terrorism may shift to safer provinces, so that economic losses in one place are offset by economic gains elsewhere (Gaibulloev and Sandler 2023). Indeed, there is empirical evidence that terrorist attacks are not evenly distributed within a country and can vary significantly between regions and over time (Mazhar 2019; Öcal and Yildirim 2010). This could mean that the internationalization activities of firms located in terrorism-ridden regions tend to be more affected by terrorism than firms located in other regions of the country. Of course, this depends on whether the effects of terrorism are localized or whether there are negative interregional spillovers from terrorism. Macroeconomic studies that rely on terrorism at the country level tend to obscure such relationships, which means that the results of these empirical studies do not allow conclusions to be drawn about the microeconomic relationships between terrorism and international trade.

This study attempts to fill this research gap by investigating the relationship between exports and terrorism at the firm- and city-level, thereby testing the microeconomic basis of macroeconomic research in this area. Recent research suggests that firms’ capabilities are determined by local environments, such as urban clusters, and that studies examining firms’ internationalization activities benefit from not only focusing on the country-of-origin, but also zooming in to the level of the city or a subnational region (Côté, Estrin, and Shapiro 2020; Mudambi et al. 2018). Therefore, our disaggregated approach complements macro-level research in two ways. First, this paper follows the call to consider the spatial dimension of terrorism and the corresponding dynamics over time (Gaibulloev and Sandler 2023; LaFree 2010). Our subnational approach allows us to empirically investigate whether firm exports are related to terrorist attacks in the cities where the firms are located and whether firm’ exports are related to terrorist attacks in other cities through interregional spillover effects.

Second, beyond the macroeconomic relationship between terrorism and international trade, this is the first study, to the authors’ knowledge, to use firm-level panel data to empirically examine the relationship between terrorism and exports. A negative correlation between terrorist attacks and exports is found by Osgood and Simonelli (2020), who examine the relationship between terrorism and vertical foreign investment by US firms. However, their study focuses on the very specific case of intra-firm exports, i.e. production abroad for sale at home. In contrast, our study examines firm exports as a whole, and we focus on Pakistan, which has been consistently ranked as one of the countries most affected by terrorism since 2002 according to the Global Terrorism Index (Institute for Economics & Peace 2015; 20–22). Since the economic impact of terrorist attacks is particularly high in countries that are severely affected by terrorism (Mirza and Verdier 2008), it is to be expected that the export activities of firms in such economies could also be severely affected by terrorism. Rather than conducting a cross-country analysis, we use a single country approach, which also implies that all firms in our sample tend to face the same institutional environment, e.g. trade regulations and legal frameworks. At the same time, we take into account sub-national differences in terms of the location of firms and terrorist incidents.

Our empirical strategy allows us to control for a substantial part of unobserved heterogeneity that may influence the results of empirical studies at the country-level. We use a panel data estimation with firm-specific and year-specific fixed effects to eliminate variation due to unobserved time-invariant factors (stable firm and city characteristics) as well as unobserved year-specific factors (systematic factors affecting all firms and cities in a given year) that may confound the relationship between a firm’s export ratio and terrorism. Our results may therefore be less affected by problems of aggregation and omitted variables than the results of previous studies. However, like previous empirical studies in this area, our study is based on observational data. Without a natural experiment or valid instrumental variables, it is not possible to identify causal effects. Therefore, we do not claim to be able to identify causal effects of terrorism and interpret our results with due caution, pointing to correlations or empirical relationships rather than (causal) effects.

Our empirical analysis is based on a unique panel dataset containing the State Bank of Pakistan’s financial data for 301 firms listed at the Pakistan Stock Exchange (PSX) from 1999 to 2014. To account for the regional dimension of terrorism, we have compiled detailed terrorism data from the South Asian Terrorism Portal (SATP) for different regions (cities) of Pakistan over fifteen years. Based on the number of terrorist incidents, the number of fatalities, and the number of injuries we constructed a City Terrorism Index (CTI) for each city following the Global Terrorism Index (Institute for Economics & Peace 2018). In addition, we also consider the impact of terrorism outside the city in which a firm is located by constructing a distance-weighted indicator for terrorism outside a city, assuming that firm exports tend to be stronger disrupted by terrorist attacks in geographical proximity than by terrorism in more distant regions. Our empirical panel estimations show that there is a negative and statistically significant correlation between a firm’s export ratio and the level of terrorism in the cities where the firms are located. The empirical correlations are strongest in the medium term, and slowly decrease over time. Although we also find some empirical evidence of a correlation between firm exports and terrorism in other regions, suggesting interregional spillovers of terrorism, the strongest correlation is found between firms’ export ratios and terrorist incidents in the same city.

2 Terrorism, Firm Exports, and Interregional Spillovers

Terrorism can be defined as “the threatened or actual use of illegal force and violence by a non-state actor to attain a political, economic, religious, or social goal through fear, coercion, or intimidation” (Institute for Economics & Peace 2022, p. 6).[1] Individual terrorist attacks are quite random and unpredictable, creating a broader atmosphere of fear in addition to physical destruction and human suffering. Terrorism can affect the business operations of firms – even if this is not necessarily the main intention of the terrorists.

Terrorism can directly affect the capability of firms to innovate, produce and sell their products by disrupting R&D, organizational and production processes. For example, terror-induced uncertainty over returns from R&D projects reduces significantly firm’s R&D investments as firms opt to defer their investments (Li et al. 2022). In addition, employees may not show up for work or some investment plans may not be implemented due to uncertainty, which may negatively affect the scale of production, productivity or quality of products. The negative effects of terrorism on companies’ capabilities can also affect their exports (Bandyopadhyay, Sandler, and Younas 2018).

Terrorism can also impact access to markets, as it may detract firms’ business activities through a decrease in customer demand as well as additional costs of doing business and changes in government regulations and policies (Czinkota et al. 2010; Suder 2004). In particular, terrorism can impede firms’ access to world markets in at least three ways. First, terrorism can be conceptualized as an increase in trade costs, such as a hidden tax or tariff on trade, whereby transportation costs associated with bilateral trade increase when terrorism increases in trading countries (Egger and Gassebner 2015; Lenain, Bonturi, and Koen 2002; Mirza and Verdier 2008; Nitsch and Schumacher 2004; Walkenhorst and Dihel 2006). Second, terrorism increases uncertainty and creates an atmosphere of fear and mistrust among business partners. Consequently, firms might be unwilling to enter into business contacts with actors operating in an insecure and risky business environment. Business plans become less reliable, if not obsolete, and travel to terrorism-prone countries becomes more dangerous and more expensive (e.g. higher insurance premiums). Terrorism can deter international business contacts, as international customers are not only less familiar with local risks but are also more likely to choose alternative business opportunities and locations than local firms (cf. Becker and Rubinstein 2011; Greenbaum, Dugan and LaFree 2007). Even if there are alternative solutions for communicating with customers in foreign markets, the lack of face-to-face interaction can diminish the likelihood of future business deals. Tan and Colleagues (2024) show that suppliers located near terrorist attacks are 2.9 percentage points more likely to terminate business relationships with their main customers within two years following the attacks. Increased perceptions of risk in the supply chain by major customers is the main reason for terminating the relationship. Similarly, terrorism affects acquisitions as top managers of acquiring firms are often reluctant to invest in terrorism-afflicted areas, in part because they are less willing to travel to the headquarters of target firms near terrorist attack sites (Nguyen, Petmezas, and Karampatsas 2023). Third, trade is indirectly affected by legislative and organizational counterterrorism measures introduced by the government to reduce the likelihood of future terrorist attacks, which also raises the cost of doing business (Gaibulloev and Sandler 2019). For example, the goods and supply chain can be affected by delays and temporary disruptions due to longer inspections, enhanced border security and stricter safety regulations (Walkenhorst and Dihel 2006), which increases the cost of exporting (Lenain, Bonturi, and Koen 2002).

While previous research has not specifically examined the link between terrorism and firm exports, there are several empirical studies that examine the effects of terrorism on trade at the macroeconomic level, and their results suggest either that terrorism has a negative effect on trade or that the effects are statistically insignificant (e.g. Bandyopadhyay, Sandler, and Younas 2018; Blomberg and Hess 2006; Egger and Gassebner 2015; Nitsch and Schumacher 2004). These ambiguous or insignificant effects may be due to the fact that the focus of previous studies has been on the macroeconomic consequences of terrorism, which may have obscured the true consequences of terrorism, which are only identifiable at the micro level. Gaibulloev and Sandler (2023, p. 294) point out that “significant localized economic impacts are entirely consistent with little overall economy-wide macroeconomic impacts.” With regard to the relationship between international trade and terrorism, Egger and Gassebner (2015, p. 60) conclude: “The average terror event is relatively small and, for countries and country-pairs, infrequent. Certainly, that does not mean that terror does not matter. It says, though, that trade might be the wrong domain to look for big effects.” Furthermore, Nitsch and Schumacher (2004, p. 424 ff.) state: “In fact, it is possible that terrorism has almost no measurable effect on trade since the overwhelming majority of terrorist actions are operations with only local implications.” Given the relevance of the local dimension of terrorism for economic activities in general, Greenbaum and Hultquist (2006, p. 128) suggest that “future research should use the disaggregated nature of city-level data further to more carefully examine the spatial relationships among cities and to better understand the implications of a terrorist attack on the regional economy.”

Against this background, we argue that the local dimension of terrorism should be considered when examining the relationship between exports and terrorism, and that the most promising way to identify potential effects of terrorism on exports is to focus on countries that are heavily affected by terrorism and to analyze the link between terrorism and exports at the micro level (cf. Mazhar 2019). In particular, firms operating in terrorism-prone countries suffer from frequent and severe terrorist attacks, which can hamper their exports. But even within a country threatened by terrorism, not all regions and cities are affected by terrorism in the same way, and it is to be expected that the export activities of firms located in cities and regions with many and severe terrorist attacks will be particularly negatively affected by terrorism.

However, not only terrorism in the same city or region can affect firm exports, but also terrorism in other regions due to interregional spillover effects of terrorism, and these spillover effects can be positive or negative. On the one hand, terrorism in other regions can have a negative impact on firm’s access to world markets, for example through rising export costs. In addition, intense media coverage of terrorist attacks can trigger widespread uncertainty and fear among economic actors far beyond the city or region attacked (Nellis and Savage 2012). On the other hand, terrorism in other regions can also facilitate firms’ access to world markets because international customers can shift their imports from regions threatened by terrorism to other regions.

Due to the aggregation of data, these micro-level effects of terrorism may be blurred in empirical analyses that focus on the macro level, which could explain the ambiguous results of macroeconomic studies. Therefore, to shed light on the relationship between terrorism and firm exports at the micro level, we use firm-level data and city-level terrorism indicators in our empirical analysis.

3 Data

3.1 Data Sources and Sample

Our study uses financial data of firms and terrorist incidents data in various cities of Pakistan. Our empirical analysis is based on two data sources. Firm information comes from the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) Balance Sheet Analysis, which contains data on firms listed on the Pakistan Stock Exchange. As it was not possible to obtain the data electronically, we received PDF files from the State Bank of Pakistan, which we had to compile manually. The State Bank of Pakistan’s dataset covers all non-financial firms from all industries and is considered the most reliable source of data for listed firms in Pakistan. The dataset contains information on firms’ export sales and other financial variables. The balance sheet analysis is published annually and we have compiled firm-level information for firms listed on the Pakistan Stock Exchange (PSX) between 1999 and 2014.[2] We have analyzed the balance sheet data in detail and found that a large number of key figures are missing. Hence, complete information is not available for all companies and not for all years. We also carefully checked the data for inconsistencies and only included those companies or data that appeared reliable. Based on this information, we were able to construct a reliable dataset for an unbalanced panel of 301 non-financial firms. We do not claim, however, that the companies in our sample are representative of all companies in Pakistan.

The data on terrorism in Pakistan between 1999 and 2014 comes from the South Asian Terrorism Portal (SATP), which is maintained by the Institute of Conflict Management in India. The SATP contains very detailed information on terrorist activities in South Asian countries, making it one of the most comprehensive and reliable sources of data on terrorist attacks in Pakistan. The information on terrorist attacks is largely sourced from print and electronic media reports on terrorist incidents. SATP contains information on suicide attacks and bombings (explosions), which account for about 60 % of all terrorist activities (cf. Gaibulloev and Sandler 2019). More detailed information on each event is provided in text form. As the SATP database contains detailed information on the location of terrorist attacks, we can attribute terrorist attacks to 105 cities in Pakistan. In addition, we have also extracted all relevant information regarding the number of incidents, the number of fatalities, and the number of injuries caused by terrorists in a given year, all of which are used to construct a terrorism index for each city and year (see next section).

The data provided by the SATP on terrorism in Pakistan has already been used for studies on the determinants of terrorism (Ismail and Amjad 2014), the relationship between economic growth and terrorism (Shahbaz et al. 2013), the impact of terrorism on foreign direct investment (Haider and Anwar 2014) and migrant remittances (Mughal and Anwar 2015). However, these studies focus on the national level, while our study is the first to use highly detailed information on terrorist activities to create a reliable dataset for a balanced panel of Pakistani cities. By merging the two data sets, i.e. the data at company level and the regional terrorism data, we are able to exploit the temporal and spatial variations.

3.2 Measurement of Variables

One of the most common indicators for firm’s export performance is the export ratio, our dependent variable, which is measured by the ratio of export sales to total sales (e.g. Roper and Love 2002).

Our main independent variables are a City Terrorism Index (CTI) and an Interregional Terrorism Index (IRTI), which measures the severity of terrorism at city and regional levels. Most papers examining the impact of terrorism on trade often measure terrorism as a binary variable that takes the value 1 if at least one terrorist attack between two trading partners has been recorded and 0 otherwise (Blomberg and Hess 2006; Nitsch and Schumacher 2004). Alternatively, some authors count the number of terrorist attacks (Nitsch and Schumacher 2004). However, these approaches do not allow us to take into account the severity of terrorism, which is expressed, for example, in the number of incidents, fatalities, and injuries. Our work offers a methodological advantage in terms of measuring terrorism. To better reflect the severity of these incidents, we therefore also take into account the number of fatalities and the number of injuries. Even though all three indicators could be included separately in our regression analysis, the interpretation of the estimation results might be problematic as the three indicators are strongly correlated. For instance, the correlation between the number of injuries and the number of fatalities is 0.91.

Hence, instead of including the three measures separately, we follow the approach of the Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP), which computes the Global Terrorism Index (GTI). This index is an indicator of the extent of terrorism at country level. We adapted the GTI computation (see Institute for Economics & Peace 2022, p. 87) to construct a City Terrorism Index (CTI) for each city j in each year t:[3]

Based on our theoretical considerations, we assume that firm exports can also be affected by terrorist attacks outside the city in which it is based, e.g. by terrorism in neighboring or more distant regions. To examine such interregional effects of terrorist attacks, we constructed an Interregional Terrorism Index (IRTI) that measures the level of terrorist attacks in other regions. We identify 105 locations in Pakistan and measure the level of terrorist incidents in each location. We argue that the impact of terrorism diminishes with increasing distance. To create weights that reflect the diminishing impact of terrorism, we measured the pairwise distances between the cities where firms are located and all other (104) locations using the great circle distance (geographic city centers).[4] We apply the Haversine formula, which is commonly used to calculate the distance between two points on the earth surface based on longitude and latitude coordinates. The (pairwise) weights (α jl ) are the inverse of the corresponding kilometer aerial distances (D) between a city j and a location l: α jl = 1/D jl . The Interregional Terrorism Index (IRTI) for a city j in year t is given by:

where N is the number of all locations. The measure that captures the level of terrorism in the city where a firm is located and the interregional spillovers of terrorism is the Total Terrorism Index (TTI), which is computed as the sum of the CTI and the IRTI for each city j and for each year t.

The listed companies in our dataset are headquartered in 21 cities. We use the information on terrorist activities in the other 84 cities in our sample to calculate the IRTI indices and the TTI indices.

At the firm level, we also include several control variables. Firm size is identified as a relevant determinant of export performance (Chetty and Hamilton 1993; Sousa, Martínez‐López, and Coelho 2008). In our panel data analysis, the average size of a firm is already accounted for by firm-specific fixed effects. However, to control for the change in firm size over time, we include two additional variables that are used in the literature as indicators of firm size, namely a firm’s total sales and total assets (both in logarithms). Financial risk can affect the ability of firms to engage in export activities (Egger and Kesina 2013; Greenaway, Guariglia, and Kneller 2007). To control for financial risk, we include a firm’s financial leverage as an indicator of financial risk, measured as the ratio of total liabilities to total assets. These control variables are lagged by one year to reduce potential endogeneity problems.

3.3 Terrorism in Pakistan: Differences Between Cities and Over Time

The intensity of terrorist attacks varies remarkably across cities (regions) in Pakistan and over time, as shown in Figure 1 for the City Terrorism Index (CTI) in five provincial capitals. On the one hand, there are cities where the intensity of terrorism is high, e.g. Peshawar, Karachi and Quetta. On the other hand, there are cities where the intensity of terrorism is low, e.g. Faisalabad. Although terrorism has generally increased since 2006, it is worth noting that not all cities are affected in the same ways. The CTI peaks differ not only in intensity (e.g. 1,112 for Karachi and 2,165 for Peshawar), but also over time (e.g. for Karachi in 2013 and for Peshawar in 2009). As can be seen in Figure 1, our measure of terrorism at the city-level (CTI) does not follow a clear or systematic pattern: The CTI may rise sharply in one year, followed by a sharp decline in the next. Moreover, each terrorist attack is quite random and unpredictable, which means that terrorist attacks can be seen as exogenous shocks from firms’ perspective.

Terrorism in cities across Pakistan (CTI index). Source: South Asian Terrorism Portal (2018).

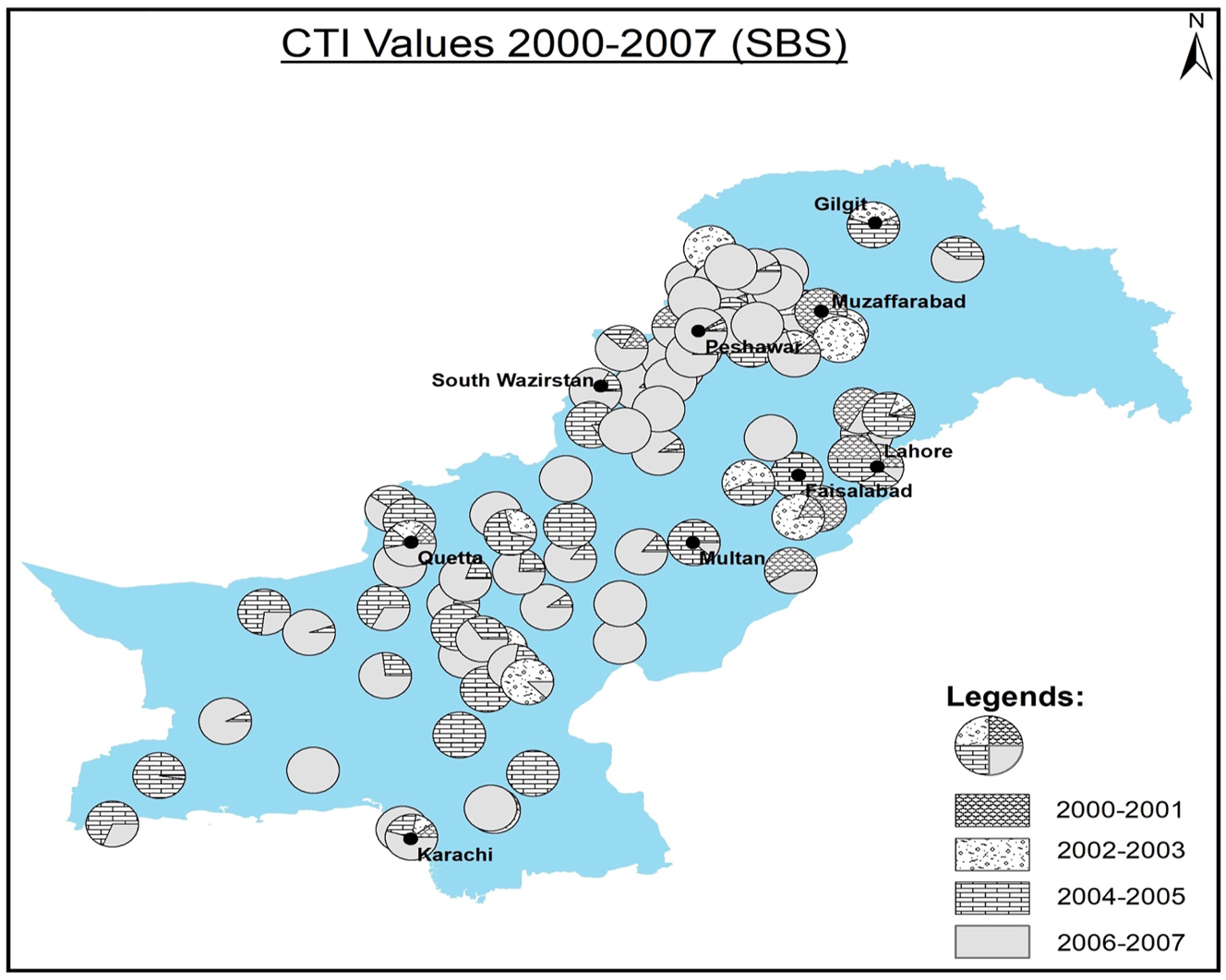

Figure 2 depicts the intensity of terrorism for all target cities between 2000 and 2007. Each pie chart represents a city and contains the CTI intensity for up to four two-year periods. Pie charts with a single shaded pattern indicate that terrorist attacks only occurred within one specific two-year period. Pie charts with multiple patterns mean that terrorism occurred in more than just two years. The larger the relative CTI value within a time period, the larger the shaded area in each pie. For 2000–2001, very few cities are affected by terrorist attacks. Thereafter, more and more cities are attacked, especially in the northwestern border provinces of Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPk), which share a border with Afghanistan.

City Terrorism Index (CTI) in Pakistani cities for the 2000 to 2007 period. Source: South Asian Terrorism Portal (2018). Each circle represents the CTI intensity for a given city or region in the case of FATA, Gilgit-Baltistan, and Azad Kashmir. Patterns within the pie show the accumulated value of CTI for two years (e.g. 2000–2001). Dot in the circle represents the geographic location of the labeled city in the map of Pakistan.

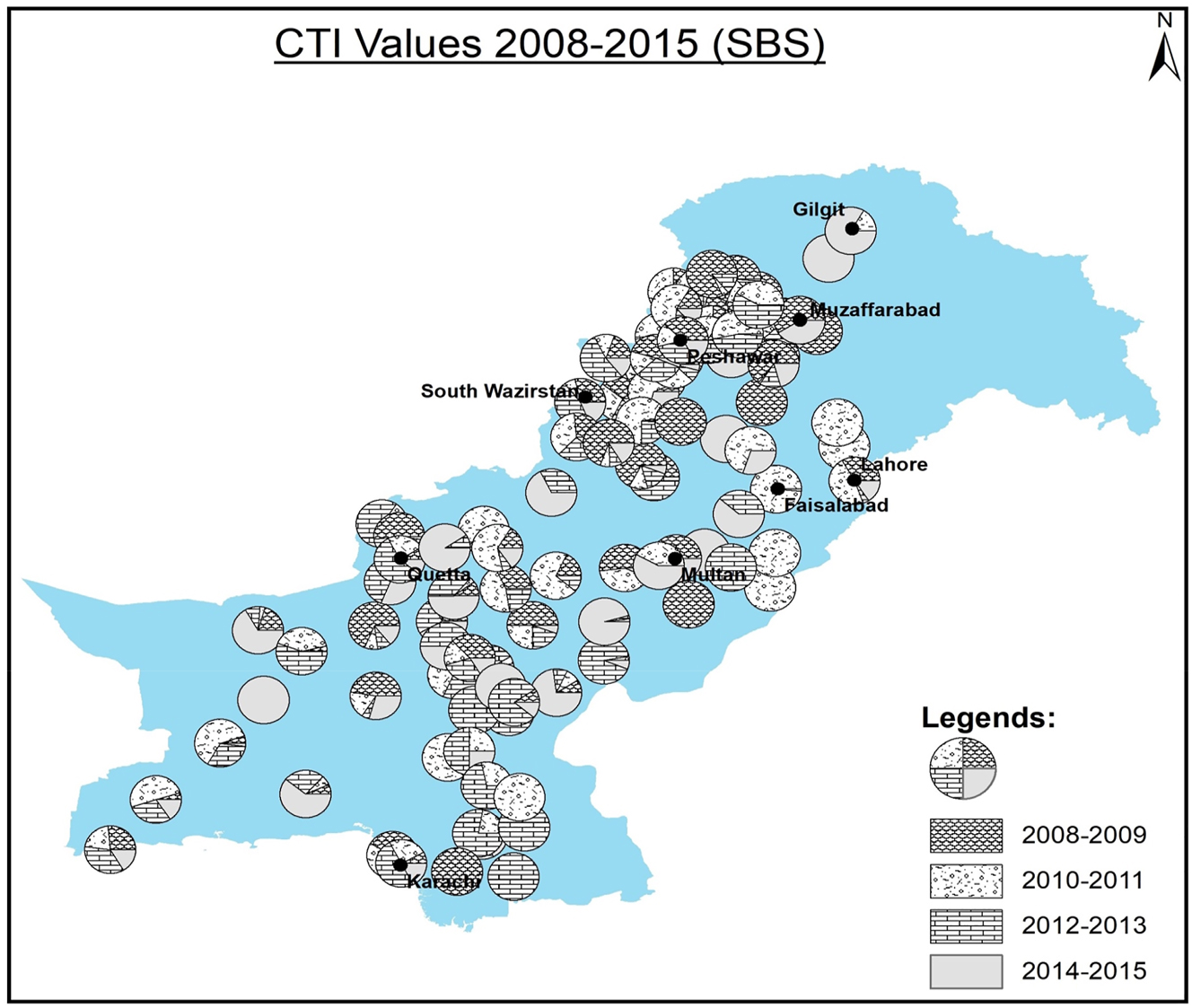

Similarly, Figure 3 shows the intensity of terrorism for terrorism-affected cities between 2008 and 2015, showing a rapid expansion of terrorism across the country, with terrorist activities shifting from Balochistan and KPk to new cities in the eastern provinces of Punjab and Sind. Overall, the descriptive findings show that terrorist incidents and their intensity can vary remarkably between cities (regions) and over time, supporting the notion that terrorist incidents in Pakistan are rather unpredictable and random. Consequently, cross-regional and country-specific studies, that look at the country as a whole, ignore any subnational variation and thus do not take into account the heterogeneity of terrorism between cities and over time. Therefore, in our empirical analysis, we focus on the geographical and intertemporal dispersion of terrorism in Pakistan.

City Terrorism Index (CTI) in Pakistani cities for the 2008 to 2015 period. Source: South Asian Terrorism Portal (2018). Each circle represents the CTI intensity for a given city or region in the case of FATA, Gilgit-Baltistan, and Azad Kashmir. Patterns within the pie show the accumulated value of CTI for two years (e.g. 2008–2009). Dot in the circle represents the geographic location of the labeled city in the map of Pakistan.

4 Econometric Specification

Our panel data allow us to control for unobserved heterogeneity in several ways. We use a two-way fixed-effects model in which we include firm-specific fixed effects that control for all unobserved variables that do not change over time, and time-specific fixed effects that control for all unobserved variables that affect all firms in a given year in the same way. Our econometric specification is as follows:

where ER ijt is the export ratio of firm i (percentage of export sales in total sales) located in city j in year t, γ i is a firm-specific fixed effect, γ t is a time-specific fixed effect, and ∈ it is an error term. The independent variables of interest are the lagged values of the Total Terrorism Index (TTI) where the maximum lag is five (T = 5). We also include three control variables, namely the logarithm of financial leverage (FL), the logarithm of sales (LS) and the logarithm of total assets (LA). In addition, all explanatory variables are lagged by one year for two reasons: First, terrorist attacks that occur at the end of a year, for example, cannot affect export ratios in the preceding months (also known as time aggregation bias) and by using lagged values we can rule out such cases (Egger and Gassebner 2015). Second, lagged values further reduce potential endogeneity problems. Finally, we take into account that the error terms of firms located in the same city may not be independent. Therefore, we make use of cluster-robust standard errors, i.e. robust errors are clustered at the city level.

Our two-way fixed effects model allows us to eliminate a substantial amount of variation that may include time-invariant and year-specific confounding factors that would otherwise lead to biased parameter estimates. It should be noted that the inclusion of firm-specific fixed effects eliminates the between-firm variation and our parameter estimates are therefore based on the within-firm variation over time. The inclusion of year-specific fixed effects ensures that our parameter estimates are based on city-specific variation in terrorism levels over time. Including only lagged values of the terrorism variables in our regression analyzes further reduces potential endogeneity problems. However, we acknowledge that controlling for firm-specific and time-specific fixed effects and including only lagged terrorism variables cannot completely rule out potential endogeneity biases due to unobserved variables.

More precisely, our panel estimator allows us to control for unobserved variables that are constant over time (time-invariant characteristics of a firm and the city in which it is located) and common year-specific effects, but not for unobserved city-specific variables that change over time. Therefore, endogeneity problems could arise due to omitted variables, which would mean that our estimated coefficients of the terrorism variables would be biased and could not be interpreted as causal effects. However, unobserved city-specific variables that change over time only lead to biased results if they are also correlated with changes in our terrorism measures, such as the City Terrorism Index (CTI). For example, one such unobserved variable could be changes in demand factors in export destination countries, which could affect changes in firms’ exports. However, we find it unlikely that such demand-side factors are city-specific and thus correlated with the year-to-year change in terrorism in a given city. While lower demand for Pakistani imports in destination markets may be caused by factors such as exchange rate changes, recessions, changes in tastes/preferences, or simply trade diversion to other markets, these factors are likely to affect exports by firms in all cities, but are unlikely to correlate with city-specific annual changes in terrorism. Therefore, we argue that such unobserved demand-side factors are likely to be captured by time-specific fixed effects, as they affect all cities in a similar way. Another unobserved variable could be annual changes in local socioeconomic conditions in the cities where the firms are located. Unobserved local socio-economic conditions that do not change over time are already captured by the firm-specific fixed effects in our analysis. However, our econometric specification does not allow us to account for unobserved city-specific variables that change over time.

Of course, we have thought hard about how to solve the problem of unobserved time-varying city-specific variables. One possible solution would be to use city-specific instrumental variables that change over time. Unfortunately, reliable city-level information is not available for Pakistani cities due to lack of data. However, even if such data were available, it would be difficult to find variables that are sufficiently correlated with year-to-year changes in the City Terrorism Indices (CTIs) while being exogenous and satisfying the exclusion condition. Our descriptive analyzes of the variation in terrorism in Pakistan across cities and time show that CTIs often rise sharply in one year and fall sharply in the next. Since individual terrorist attacks tend to be random and unpredictable, annual CTIs tend to exhibit an erratic pattern. However, this may also suggest that unobserved time-varying city-specific variables do not pose too much of a problem for our analysis, as the generally more uniform changes in city-specific socioeconomic conditions are unlikely to follow the same temporal pattern as CTIs and are therefore unlikely to be strongly correlated with them. Nevertheless, we interpret our results with due caution, as our coefficient estimates are correlations or empirical associations that do not necessarily reflect causal effects.

5 Descriptive Statistics and Estimation Results

5.1 Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics and the correlation matrix for the data used in our regression analyses can be found in Tables 1 and 2. As can be seen in Table 2, the two control variables, total assets and sales, are highly correlated. Moreover, the pairwise correlation between the export ratio and IRTI is negative and statistically significant, while the correlations between the export ratio and the other two terrorism indices, namely TTI and CTI, are statistically insignificant. Note, however, that these correlations are based on the total variation in our panel data (variation between and within firms), while our regression analyzes are based only on within-firm variation. Furthermore, in our empirical analyses, we take into account that the export ratio can be affected by terrorist attacks with a longer time lag.

Descriptive statistics.

| Variable | Mean | Std. dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Export ratio | 19.325 | 28.591 | 0 | 100 |

| TTI | 287.625 | 316.478 | 2.106 | 2,227.432 |

| CTI | 275.330 | 316.025 | 0 | 2,164.5 |

| IRTI | 12.296 | 12.945 | 1.706 | 94.072 |

| LS (ln total sales) | 14.584 | 1.682 | 5.624 | 19.334 |

| LA (ln total assets) | 14.526 | 1.550 | 8.536 | 19.410 |

| FL (ln financial leverage) | 0.6739 | 0.4529 | 0.0139 | 9.1334 |

-

The number of firms is 301 and the number of observations is 2,450. All explanatory variables are lagged by one year.

Correlation matrix.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| 1 Export ratio | 1 | ||||||

| 2 TTI | 0.0271 | 1 | |||||

| 3 CTI | 0.0303 | 0.9992a | 1 | ||||

| 4 IRTI | −0.0803a | 0.0640a | 0.0250 | 1 | |||

| 5 LS (ln total sales) | 0.1046a | 0.1038a | 0.1029a | 0.0268 | 1 | ||

| 6 LA (ln total assets) | 0.1004a | 0.0820a | 0.0802a | 0.0508a | 0.8973a | 1 | |

| 7 FL (ln financial leverage) | −0.0226 | 0.0142 | 0.0149 | −0.0174 | −0.2000a | −0.1739a | 1 |

-

The number of firms is 301 and the number of observations is 2,450. All explanatory variables are lagged by one year. aCorrelation is statistically significant at p < 0.05.

5.2 Estimation Results

The estimation results for the panel of 301 listed firms are reported in Table 3. All estimations include firm-specific fixed effects, time-specific fixed effects and control variables. By including firm-specific fixed effects, we control for all unobserved variables that do not change over time. Such unobserved variables could be, for instance, the quality of a firm’s management or the institutional environment of the region (city) in which the firm is located. By including time-specific fixed effects, we control for all variables that affect all firms in a given year in the same way, e.g. business cycle effects. Our empirical results show that the year-specific fixed effects are statistically significant.

The relationship between export ratio and terrorism.

| Independent variable: export ratio | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Main explanatory variable: | TTI | CTI | IRTI |

| LAG 1 | −0.000384 (0.001487) | −0.000266 (0.001042) | −0.0350484 (0.02488) |

| [−0.002267, 0.007563] | [−0.0021741, 0.0016395] | [−0.080843, 0.012699] | |

| LAG 2 | −0.00216b (0.001000) | −0.002069c (0.001025) | −0.037034 (0.028666) |

| [−0.003955, −0.000317] | [−0.003889, −0.000171] | [−0.088902, 0.016711] | |

| LAG 3 | −0.00239a (0.000457) | −0.002382a (0.000478) | 0.015589 (0.035821) |

| [−0.0032518, −0.001516] | [−0.003300, −0.001477] | [−0.044095, 0.075154] | |

| LAG 4 | −0.00273a (0.000935) | −0.002643b (0.000979) | −0.058556b (0.022971) |

| [−0.004461, −0.000965] | [−0.004451, −0.000811] | [−0.102088, −0.015361] | |

| LAG 5 | −0.00251a (0.000897) | −0.00236b (0.000861) | −0.034522c (0.016837) |

| [−0.004163, −0.000871] | [−0.0039144, −0.000804] | [−0.064473, 0.003856] | |

| Log sales | 3.221b (0.935593) | 3.201a (0.939409) | 3.210a (0.928214) |

| [1.451655, 4.946726] | [1.429953, 4.947002] | [1.48438, 4.91671] | |

| Financial leverage | −3.700a (1.162125) | −3.683a (1.15418) | −3.968a (1.33597) |

| [−5.812023, −1.572509] | [−5.782655, −1.570508] | [−6.38667, −1.563549] | |

| Log total assets | 0.550 (1.880484) | 0.554 (1.879525) | 0.497 (1.868194) |

| [−3.758028, 2.677444] | [−3.760867, 2.670566] | [3.665236, 2.682253] | |

| R 2 (within) | 0.0666 | 0.0662 | 0.0652 |

-

Regressions are based on a sample of 301 firms and 2,450 observations. The dependent variable is firm export ratio and all firm-specific explanatory variables are lagged one year. Cluster robust standard errors that are clustered at the city level are reported in parentheses and corresponding significance levels are: a p < 0.01, b p < 0.05, c p < 0.1. The 95 % confidence interval reported in brackets was generated with wild cluster bootstrap method (Cameron, Gelbach, and Miller 2008).

Furthermore, we take into account that the error terms of firms located in the same city may not be independent. Therefore, we use cluster-robust standard errors, i.e. robust errors are clustered at the city-level. Cluster-robust standard errors that are adjusted for intra-cluster correlation within cities are reported in parentheses. Since the firms in our sample are located in only 21 different cities and “few” clusters may lead to a downward-biased estimate of the cluster-robust variance matrix (Cameron and Miller 2015), we report the confidence intervals of the coefficients generated by the wild cluster bootstrap method proposed by Cameron, Gelbach, and Miller (2008). These confidence intervals are given in parentheses.[5]

Columns (1), (2) and (3) show the results of regressions in which lagged values of the Total Terrorism Index (TTI), the City Terrorism Index (CTI) and the Interregional Terrorism Index (IRTI) are included separately as explanatory variables. In addition, firm-specific control variables are included in all three regressions with a one-year lag. The estimated coefficient of the logarithm of sales is positive and statistically significant at a five or ten percent level, indicating that higher sales in the previous year lead to a higher export ratio in the current year. The estimated coefficient of the leverage ratio is negative and statistically significant at the one percent level, indicating that financial risks tend to reduce a firm's export ratio. The estimated coefficient of the logarithm of a company’s total asset is statistically insignificant in all regressions.

In column (1), the sign of the estimated coefficients of the lagged values of TTI is always negative and also statistically significant at the five or one percent significance level for lag two to lag five, while it is not statistically different from zero for lag one at the conventional levels. The 95 percent confidence interval for each of these coefficients, confirms this result. Thus, our estimation results suggest a negative correlation between business exports and terrorist attacks, especially within cities, but also in other regions.

Next, we include the CTI and IRTI separately in our regressions to check whether firms’ export ratios are mainly correlated with terrorist attacks in the city where a firm is located or with terrorist attacks in other regions of Pakistan. Column (2) shows the results of a regression that includes only the lagged values of the CTI. The pattern of the coefficient estimates is very similar to that of the TTI variable. This result indicates that terrorism in a city is negatively associated with the export performance of firms in the same city.

In contrast, column (3) shows that the estimated coefficients of the lagged values of IRTI are negative, but only statistically significant at the five percent level for lag four. The estimated coefficients of the other lagged values of IRTI are statistically insignificant at conventional levels of significance. This suggests that the negative empirical association between terrorism and companies’ export ratios is stronger when the terrorist attacks take place in the same cities.

In addition, columns (1) and (2) show that the estimated coefficients of the first lag are very small and statistically insignificant, whereas the sizes of the estimated coefficients for lags two to five are similar, suggesting that the correlations between our terrorism measure and firm’s export ratio appear to be quite stable over a four-year period. Instead of including all lagged values of TTI separately, we assume that the correlations of four years are identical and compute the sum of TTI (STTI) for a four-year period:

Column (1) of Table 4 reports the result of a regression in which STTI is included as an explanatory variable. The estimated coefficient is negative and statistically significant at the one percent level (p < 0.01). Again, we include SCTI and SIRTI separately and the results of these regressions are reported in Columns (2) and (3). The estimated coefficients are negative and statistically significant at the one percent level for SCTI (p < 0.01) and at the five percent level for SIRTI (p < 0.05). Finally, we include both SCTI and SIRTI together to investigate whether the estimated effects are robust to the joint inclusion of both variables. As can be seen in Column (4), the sizes of both coefficients decrease and the estimated coefficient of SIRTI is now only statistically significant at the ten percent level.

The relationship between export ratio and terrorism.

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| STTI | −0.002399 a (0.000541) | |||

| [−0.003394, −0.00138] | ||||

| SCTI | −0.002341 a (0.000568) | −0.002087 a(0.000702) | ||

| [−0.003395, −0.001256] | [−0.003403, −0.000745] | |||

| SIRTI | −0.031897 b (0.014164) | −0.026159 c(0.012570) | ||

| [−0.057438, −0.006074] | [−0.049194, −0.002553] | |||

| Control variables | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Firm-specific fixed effects | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Year-specific fixed effects | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| R 2 (within) | 0.0665 | 0.0662 | 0.0645 | 0.0682 |

-

Regressions are based on a sample of 301 firms and 2,450 observations. The dependent variable is the export ratio. Cluster robust standard errors that are clustered at the city level are reported in parentheses and corresponding significance levels are: a p < 0.01, b p < 0.05, c p < 0.1. The 95 % confidence interval reported in bracket was generated with wild cluster bootstrap method (Cameron et al 2008). The estimated coefficients are in bold.

Our empirical result that terrorism in a city is negatively associated with the export ratio of firms located in that city is consistent with our theoretical considerations. From a theoretical perspective, the impact of interregional spillovers of terrorism on firms’ exports can be positive or negative. Our finding of a negative correlation is more consistent with negative spillover effects, implying that even the exports of companies in cities less affected by terrorism are negatively associated with terrorist activities in other regions.

Regarding the time dimension of the observed correlations, our results suggest that the estimated coefficients are statistically significant with a lag of about two years. In our empirical analysis, we use measures of terrorism that are lagged at least one year, implicitly assuming that a firm’s export ratio in a given year is not related to terrorist attacks in the same year. While this procedure may avoid potential endogeneity problems, it also neglects potential short-term correlations between the export ratio and terrorism. In order to check the robustness of our results, we conduct our regressions with non-lagged measures of terrorism. Although not reported here, the estimated coefficients of current terrorism indices are statistically insignificant, thus providing further evidence that terrorist attacks are not associated with firms export ratios in the short-term. Moreover, our results suggest that the correlations between terrorism and firm export ratios do not decline rapidly over time. We find that terrorist activities are still correlated with firm exports, even after five years. If we also include longer lags, the results are hardly affected. However, including longer lags leads to a reduction in the number of observations and a change in the observation period; therefore, we present the results for up to five lags.

In order to further check the robustness of our results, we conduct additional analyzes. The logarithm of sales (LS) is included as an explanatory variable in our regressions. However, it can be argued that total sales should not be included in the regression because total sales itself is endogenous to terrorism and including sales as an explanatory variable – even when lagged by one year – could lead to biased estimates due to a bad control problem (Angrist and Pischke 2008). We therefore run regressions in which we exclude sales. As can be seen from the Columns 1a and 1b in Table 5, the results hardly differ from those in Columns 1 and 4 of Table 4, suggesting that it does not seem to matter whether total sales are included as an explanatory variable or not.

Additional analyses.

| (1a) | (1b) | (2a) | (2b) | (2c) | (3a) | (3b) | (3c) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Export ratio | Export sales | Domestic sales | |||||

| Model | Log-linear | Log-linear | Log-log | Log-linear | Log-linear | Log-log | ||

| Dependent Variables | ||||||||

| STTI | −0.002165a | −0.000337b | 0.000112b | |||||

| (0.0004986) | (0.0001561) | (0.000508) | ||||||

| SCTI | −0.001894a | −0.000251c | −0.2447309b | 0.000085 | 0.0674587 | |||

| (0.0006478) | (0.0001374) | (0.0986541) | (0.000059) | (0.0423323) | ||||

| SIRTI | −0.022406c | −0.006797c | −0.5061045 | 0.002145 | 0.072341 | |||

| (0.0119976) | (0.003574) | (0.3881592) | (0.0013038) | (0.1166965) | ||||

| Control variables | YES, excluding total sales | YES | YES | |||||

| Firm-specific fixed effects | YES | YES | YES | |||||

| Year-specific fixed effects | YES | YES | YES | |||||

| R 2 (within) | 0.0563 | 0.0665 | 0.1161 | 0.1180 | 0.1197 | 0.1208 | 0.1233 | 0.1228 |

-

Regressions are based on a sample of 301 firms and 2,450 observations. Cluster robust standard errors that are clustered at the city level are reported in parentheses and corresponding significance levels are: a p < 0.01, b p < 0.05, c p < 0.1.

We reasoned that terrorism in a region can have a negative impact on the exports of firms in that region, as it can have a negative impact on companies’ production capabilities and their access to markets. It can be argued, however, that these negative effects of terrorism not only apply to firms’ exports but also to firms’ domestic sales. Consequently, our dependent variable, the export ratio, may change due to the impact of terrorism on export sales, the numerator of the export ratio, or due to the impact of terrorism on domestic sales, which is part of the denominator of the export ratio, or due to the impact on both. We therefore run additional regressions in which the dependent variables are export sales and domestic sales. We use a log-linear specification in which only the dependent variable is logarithmized.[6] The results of these regressions are reported in Table 5. As can be seen from Columns 2a and 3a, the estimated coefficients of STTI in both regressions are statistically significant at the five percent level. As expected, the sign of the estimated coefficient for exports is negative. However, it is positive for domestic sales, which could mean that companies are replacing part of the decline in exports caused by terrorism with domestic sales.

When distinguishing between the effects of local terrorism (SCTI) and the interregional spillovers of terrorism (SIRTI), the estimated coefficients are statistically significant at the ten percent level with exports as the dependent variable (Column 2b), while they are statistically insignificant at the conventional significance level with domestic sales as the dependent variable (Column 3b).

Moreover, we also use a log-log specification in which the terrorism variables are also logarithmized, implying that the estimated coefficients reflect elasticities. Our results reported in Column 2c show that the estimated coefficient of SCTI is statistically significant at the five percent level. In contrast, for domestic sales, the estimated coefficients of the terrorism variables are statistically insignificant at conventional significance levels (Column 3c). Overall, our results suggest that the correlation between terrorism in a city and exports of firms located there is negative and statistically significant, while the correlation with domestic sales, if present, is positive and very low.

We also run additional regressions similar to those in Table 3, looking at the three components of the CTI index individually, i.e. the number of incidents, the number of fatalities and the number of injuries at the city level. The estimated coefficients for each component are also negative and statistically significant in most cases.

Finally, we restrict the regressions to a subsample of large exporting firms to determine whether there is empirical evidence that these firms are shifting to the domestic market. Only those observations are considered for which two conditions are simultaneously met: (a) sales are higher than the median sales, (b) the export ratio is higher than the median export ratio. Our estimation results shown in Table 4 are confirmed for this sub-sample.[7]

6 Discussion and Conclusion

Using a unique dataset that merges information from 301 firms listed on the Pakistan Stock Exchange with measures of terrorism in 105 cities/regions in Pakistan between 1999 and 2014, this study provides insights into the relationship between firm exports and terrorism at the micro level. While Pakistan has been one of the most terrorism-plagued countries in the world over the last two decades, our data shows that the level of terrorism varies significantly across Pakistani cities and also over time.

Overall, our empirical results point to a negative correlation between firms’ export ratio and terrorism. The negative correlation is quite stable in the years following a terrorist attack, which may suggest that exports might be impaired by terrorism for longer than expected. Moreover, we find robust empirical evidence for a correlation between firm exports and local terrorist attacks that occur in the same city where a firm is located. We also find somewhat weaker empirical evidence for an association between export performance and terrorism in other cities, suggesting possible interregional spillovers of terrorism in Pakistan.

While previous studies have focused on the empirical analysis of the relationship between terrorism and international trade at the macro level and have found ambiguous empirical evidence for such a relationship, we go beyond the aggregate country-level analysis and examine the underlying microeconomic relationship between terrorism and exports using firm-level data, taking into account the geographical variation of terrorism within a country and over time. In doing so, we show that firms’ exports are negatively correlated with local terrorism and thereby providing empirical evidence at the micro level for a relationship between terrorism and exports found at the macro level (e.g. Egger and Gassebner 2015; Gassebner, Keck, and Teh 2005; Nitsch and Schumacher 2004).

Moreover, we find that the correlation between firm exports and local terrorism is negative and statistically significant, while domestic sales appear to be unrelated to local terrorism. The latter result may seem surprising at first glance, as it can be assumed that domestic sales are also negatively associated with local terrorism. Empirical evidence suggests, for instance, that successful terrorist attacks in a region lead to fear and reduce consumer confidence in the respective region (Brodeur 2018), and the study by Gaibulloev, Oyun, and Younas (2019) suggests that there is a negative link between terrorism at the district level and subjective financial well-being at the individual level in Pakistan. However, our measure of domestic sales at the company level includes not only sales to consumers in the same region where the company is located, but also sales to other companies in the same region and sales to customers in other regions of Pakistan.

Theoretically, this raises the question of how the observed difference in the empirical relationships between local terrorism and domestic sales and local terrorism and export sales can be explained. It can be expected that the negative effects of local terrorism on (production) capabilities inhibit domestic sales and exports in a similar way. Hence, it is more likely that the differences in the relationships between local terrorism and firm exports and local terrorism and domestic sales are due to differences in the effects of local terrorism on access to domestic and foreign markets. We have argued that firms operating in highly terrorism-prone cities suffer from frequent and severe terrorist attacks because customers may switch to business partners in other regions of Pakistan or even other countries because they expect less insecurity and lower trade costs. International business customers in particular may be deterred by local terrorism because they are less familiar with local conditions than domestic business customers and may therefore avoid doing business with firms operating in terrorism-plagued regions and cities altogether. In contrast, domestic customers located in the same or a different region of Pakistan are likely to be more familiar with local conditions and may be less deterred by local terrorism. Although the relationship between firms’ domestic sales and local terrorism is not the focus of our study, this additional finding is interesting in its own right and should be investigated further in future research.

Our results suggest that terrorism may be a major obstacle for the exports of firms located in terrorism-ridden regions, despite trade and market liberalization policies that allow firms in emerging economies to more easily discover and exploit foreign market opportunities through exports (Aulakh, Rotate and Teegen 2000; Johanson and Vahlne 1977). As the number of terrorist attacks has increased dramatically since September 11, 2001, especially in emerging markets (Institute for Economy & Peace 2015; 2022), the export performance of firms in terrorism-affected regions in countries such as Pakistan can be severely affected by local terrorism.

Although we believe that our study contributes to a better understanding of the links between local terrorism and firm export activities, our study is not without limitations. First, as mentioned in the introduction, we do not claim to speak about causal effects of terrorism. Since, like previous empirical studies on the relationship between terrorism and international trade, we do not have a true natural experiment to identify causal effects, we cannot rule out the possibility of omitted variables. Nonetheless, our empirical analysis provides empirical associations that provide an interesting starting point for future research in this area. Second, due to the limited availability of reliable firm-level data in Pakistan, we focus on a specific type of firms, namely those listed on the Pakistan Stock Exchange. The companies in our sample may differ from other listed companies and non-listed companies and therefore may not be representative of all companies in Pakistan, and they may have multiple production locations. We implicitly assume that a company’s headquarters and manufacturing location are the same. While most manufacturing firms in Pakistan have their main production site at their headquarters, we cannot exclude the possibility that some firms in our sample have more than one location in Pakistan. Therefore, terrorism in cities where firms have subsidiaries could also have a negative impact on the business activities of firms. Admittedly, our City Terrorism Index (CTI) does not fully reflect the impact of terrorist attacks in locations other than headquarters, but we do take into account the impact of terrorism in other regions, at least through the Interregional Terrorism Index (IRTI). If firms have subsidiaries in other cities, the impact we estimate may even underestimate the real impact of terrorism on firm exports. In addition, the location of a firm’s headquarters may be particularly important for a firm’s access to global markets, as foreign customers are particularly familiar with a firm’s headquarters and tend to visit it on their business trips. Finally, our study is a single-country study focusing on Pakistan. This approach has its merits, as Pakistan can be representative of a developing country plagued by terrorism. However, it could also be criticized that the results may not hold for companies in other countries.

We suggest several avenues for future research: First, future studies could examine the relationship between firm exports and local terrorism for other countries affected by terrorism to see if our findings can be generalized. For example, a comparison between Pakistan, Nigeria, India, and Colombia, all of which have been affected by major terrorist attacks but have very different political, economic, and social situations, could be instructive. Moreover, it can be expected that firms will have varying degrees of willingness and ability to adopt counter-terrorism strategies and plans, which in turn may lead to heterogeneity in the impact of local terrorism on firm exports. Some firms may implement formalized programs and contingency plans to respond to terrorist attacks, while others may not. To better understand how terrorism affects exports and how firms deal with the threat of terrorism, future empirical research could further investigate at how firm exports are affected by terrorism and what measures firms take to counter terrorism.

References

Abadie, A., and J. Gardeazabal. 2003. “The Economic Costs of Conflict: A Case Study of the Basque Country.” The American Economic Review 93 (1): 113–32. https://doi.org/10.1257/000282803321455188.Search in Google Scholar

Angrist, J., and S. Pischke. 2008. Mostly Harmless Econometrics: An Empiricists’ Companion. Princeton: Princeton University Press.10.2307/j.ctvcm4j72Search in Google Scholar

Aulakh, P. S., M. Rotate, and H. Teegen. 2000. “Export Strategies and Performance of Firms from Emerging Economies: Evidence from Brazil, Chile, and Mexico.” Academy of Management Journal 43 (3): 342–61. https://doi.org/10.5465/1556399.Search in Google Scholar

Bandyopadhyay, S., T. Sandler, and J. Younas. 2014. “Foreign Direct Investment, Aid, and Terrorism.” Oxford Economic Papers 66 (1): 25–50. https://doi.org/10.1093/oep/gpt026.Search in Google Scholar

Bandyopadhyay, S., T. M. Sandler, and J. Younas. 2018. “Trade and Terrorism: A Disaggregated Approach.” Journal of Peace Research 55 (5): 656–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343318763009.Search in Google Scholar

Becker, G. S., and Y. Rubinstein. 2011. “Fear and the Response to Terrorism: An Economic Analysis.” CEP Discussion Paper No. 1079. London School of Economics and Political Science.Search in Google Scholar

Berry, H., M. F. Guillén, and N. Zhou. 2010. “An Institutional Approach to Cross-National Distance.” Journal of International Business Studies 41 (9): 1460–80. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2010.28.Search in Google Scholar

Blomberg, S. B., and G. D. Hess. 2006. “How Much Does Violence Tax Trade?” The Review of Economics and Statistics 88 (4): 599–612. https://doi.org/10.1162/rest.88.4.599.Search in Google Scholar

Boeh, K. K., and P. W. Beamish. 2012. “Travel Time and the Liability of Distance in Foreign Direct Investment: Location Choice and Entry Mode.” Journal of International Business Studies 43 (5): 525–35. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2012.10.Search in Google Scholar

Brodeur, A. 2018. “The Effect of Terrorism on Employment and Consumer Sentiment: Evidence from Successful and Failed Terror Attacks.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 10 (4): 246–82. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20160556.Search in Google Scholar

Cameron, A. C., and D. L. Miller. 2015. “A Practitioner’s Guide to Cluster-Robust Inference.” Journal of Human Resources 50 (2): 317–72. https://doi.org/10.3368/jhr.50.2.317.Search in Google Scholar

Cameron, A. C., J. B. Gelbach, and D. L. Miller. 2008. “Bootstrap-Based Improvements for Inference with Clustered Errors.” The Review of Economics and Statistics 90 (3): 414–27. https://doi.org/10.1162/rest.90.3.414.Search in Google Scholar

Chen, A. H., and T. F. Siems. 2004. “The Effects of Terrorism on Global Capital Markets.” European Journal of Political Economy 20 (2): 349–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0176-2680(03)00102-2.Search in Google Scholar

Chetty, S. K., and R. T. Hamilton. 1993. “Firm-level Determinants of Export Performance: A Meta-Analysis.” International Marketing Review 10 (3): 26–42. https://doi.org/10.1108/02651339310040643.Search in Google Scholar

Choi, S. W. 2014. “Economic Growth and Terrorism: Domestic, International, and Suicide.” Oxford Economic Papers 67 (1): 157–81. https://doi.org/10.1093/oep/gpu036.Search in Google Scholar

Côté, C., S. Estrin, and D. Shapiro. 2020. “Expanding the International Trade and Investment Policy Agenda: The Role of Cities and Services.” Journal of International Business Policy 3 (3): 199–223. https://doi.org/10.1057/s42214-020-00053-x.Search in Google Scholar

Czinkota, M. R., G. Knight, P. W. Liesch, and J. Steen. 2010. “Terrorism and International Business: A Research Agenda.” Journal of International Business Studies 41 (5): 826–43. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2010.12.Search in Google Scholar

Dai, L., L. Eden, and P. W. Beamish. 2013. “Place, Space, and Geographical Exposure: Foreign Subsidiary Survival in Conflict Zones.” Journal of International Business Studies 44 (6): 554–78. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2013.12.Search in Google Scholar

Egger, P., and M. Gassebner. 2015. “International Terrorism as a Trade Impediment?” Oxford Economic Papers 67 (1): 42–62. https://doi.org/10.1093/oep/gpu037.Search in Google Scholar

Egger, P., and M. Kesina. 2013. “Financial Constraints and Exports: Evidence from Chinese Firms.” CESifo Economic Studies 59 (4): 676–706. https://doi.org/10.1093/cesifo/ifs036.Search in Google Scholar

Enders, W., and T. Sandler. 1996. “Terrorism and Foreign Direct Investment in Spain and Greece.” Kyklos 49 (3): 331–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6435.1996.tb01400.x.Search in Google Scholar

Gaibulloev, K., and T. Sandler. 2019. “What We Have Learned about Terrorism since 9/11.” Journal of Economic Literature 57 (2): 275–328. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.20181444.Search in Google Scholar

Gaibulloev, K., and T. Sandler. 2023. “Common Myths of Terrorism.” Journal of Economic Surveys 37: 271–301. https://doi.org/10.1111/joes.12494.Search in Google Scholar

Gaibulloev, K., G. Oyun, and J. Younas. 2019. “Terrorism and Subjective Financial Well-Being: Micro-level Evidence from Pakistan.” Public Choice 178 (3–4): 493–512. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-018-0606-5.Search in Google Scholar

Gassebner, M., A. Keck, and R. Teh. 2005. “The Impact of Disasters and Terrorism on International Trade.” Review of International Economics 18 (2): 351–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9396.2010.00868.x.Search in Google Scholar

Greenaway, D., A. Guariglia, and R. Kneller. 2007. “Financial Factors and Exporting Decisions.” Journal of International Economics 73: 377–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2007.04.002.Search in Google Scholar

Greenbaum, R. T., and A. Hultquist. 2006. “The Economic Impact of Terrorist Incidents on the Italian Hospitality Industry.” Urban Affairs Review 42 (1): 113–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087406290116.Search in Google Scholar

Greenbaum, R. T., L. Dugan, and G. LaFree. 2007. “The Impact of Terrorism on Italian Employment and Business Activity.” Urban Studies 44 (5–6): 1093–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980701255999.Search in Google Scholar

Haider, M., and A. Anwar. 2014. Impact of Terrorism on FDI Flows to Pakistan. MPRA Paper No. 57165.10.2139/ssrn.2463543Search in Google Scholar

Institute for Economics & Peace. 2015. Global Terrorism Index 2015: Measuring the Impact of Terrorism. Sydney. Also available at: https://visionofhumanity.org/reports (accessed November 10, 2015).Search in Google Scholar

Institute for Economics & Peace. 2018. Global Terrorism Index 2018: Measuring the Impact of Terrorism. Sydney. Also available at: https://visionofhumanity.org/reports (accessed November 15, 2018).Search in Google Scholar

Institute for Economics & Peace. 2022. Global Terrorism Index 2022: Measuring the Impact of Terrorism. Sydney. Also available at: https://visionofhumanity.org/reports (accessed November 18, 2022).Search in Google Scholar

Ismail, A., and S. Amjad. 2014. “Determinants of Terrorism in Pakistan: An Empirical Investigation.” Economic Modelling 37: 320–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2013.11.012.Search in Google Scholar

Johanson, J., and J. E. Vahlne. 1977. “The Internationalization Process of the Firm-A Model of Knowledge Development and Increasing Foreign Market Commitments.” Journal of International Business Studies 8: 23–32. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490676.Search in Google Scholar

LaFree, G. 2010. “The Global Terrorism Database: Accomplishments and Challenges.” Perspectives on Terrorism 4 (1): 24–46.Search in Google Scholar

Lenain, P., M. Bonturi, and V. Koen. 2002. The Economic Consequences of Terrorism. OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 334. Paris: OECD Publishing.Search in Google Scholar

Li, D., T. W. Tong, Y. Xiao, and F. Zhang. 2022. “Terrorism-induced Uncertainty and Firm R&D Investment: A Real Options View.” Journal of International Business Studies 53: 255–67. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-021-00470-x.Search in Google Scholar

Mazhar, U. 2019. “Terrorism and Firm Performance: Empirical Evidence from Pakistan.” The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy 19 (1): 20180041. https://doi.org/10.1515/bejeap-2018-0041.Search in Google Scholar

Mirza, D., and T. Verdier. 2008. “International Trade, Security and Transnational Terrorism: Theory and a Survey of Empirics.” Journal of Comparative Economics 36 (2): 179–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jce.2007.11.005.Search in Google Scholar

Mudambi, R., L. Li, X. Ma, S. Makino, G. Qian, and R. Boschma. 2018. “Zoom in, Zoom Out: Geographic Scale and Multinational Activity.” Journal of International Business Studies 49: 929–41. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-018-0158-4.Search in Google Scholar

Mughal, M. Y., and A. I. Anwar. 2015. “Do Migrant Remittances React to Bouts of Terrorism?” Defence and Peace Economics 26 (6): 567–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/10242694.2014.921359.Search in Google Scholar

Nellis, A. M., and J. Savage. 2012. “Does Watching the News Affect Fear of Terrorism? the Importance of Media Exposure on Terrorism Fear.” Crime & Delinquency 58 (5): 748–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128712452961.Search in Google Scholar

Nguyen, T., D. Petmezas, and N. Karampatsas. 2023. “Does Terrorism Affect Acquisitions?” Management Science 69 (7): 4134–68. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2022.4506.Search in Google Scholar

Nitsch, V., and D. Schumacher. 2004. “Terrorism and International Trade: An Empirical Investigation.” European Journal of Political Economy 20: 423–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2003.12.009.Search in Google Scholar

Öcal and Yildirim, 2010 Öcal, N., and J. Yildirim. 2010. “Regional Effects of Terrorism on Economic Growth in Turkey: A Geographically Weighted Regression Approach.” Journal of Peace Research 47 (4): 477–89. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343310364576.Search in Google Scholar

Osgood, I., and C. Simonelli. 2020. “Nowhere to Go: FDI, Terror, and Market-specific Assets.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 64 (9): 1584–611. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002720908314.Search in Google Scholar

Roper, S., and J. H. Love. 2002. “Innovation and Export Performance: Evidence from the UK and German Manufacturing Plants.” Research Policy 31 (7): 1087–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0048-7333(01)00175-5.Search in Google Scholar

Sandler, T., and W. Enders. 2008. “Economic Consequences of Terrorism in Developed and Developing Countries.” In Terrorism, Economic Development, and Political Openness, edited by P. Keefer, and N. Loayza. New York: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511754388.002Search in Google Scholar

Schmid, A. P., ed. 2011. The Routledge Handbook of Terrorism Research. New York: Taylor & Francis.10.4324/9780203828731Search in Google Scholar

Shahbaz, M., M. S. Shabbir, M. N. Malik, and M. E. Wolters. 2013. “An Analysis of a Causal Relationship between Economic Growth and Terrorism in Pakistan.” Economic Modelling 35: 21–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2013.06.031.Search in Google Scholar

Sousa, C. M., F. J. Martínez‐López, and F. Coelho. 2008. “The Determinants of Export Performance: A Review of the Research in the Literature between 1998 and 2005.” International Journal of Management Reviews 10 (4): 343–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2008.00232.x.Search in Google Scholar

Suder, G.G.S. 2004. Terrorism and the International Business Environment: The Security-Business Nexus. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.10.4337/9781845420772Search in Google Scholar

Tan, W., W. Wang, and W. Zhang. 2024. “The Effects of Terrorist Attacks on Supplier–Customer Relationships.” Production and Operations Management 33 (1): 146–65. https://doi.org/10.1177/10591478231224920.Search in Google Scholar

Tavares, J. 2004. “The Open Society Assesses its Enemies: Shocks, Disasters and Terrorist Attacks.” Journal of Monetary Economics 51 (5): 1039–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoneco.2004.04.009.Search in Google Scholar

Walkenhorst, P., and N. Dihel. 2006. “Trade Impacts of Increased Border Security Concerns.” International Trade Journal 20 (1): 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/08853900500467958.Search in Google Scholar

Zaheer, S., M. S. Schomaker, and L. Nachum. 2012. “Distance without Direction: Restoring Credibility to a Much-Loved Construct.” Journal of International Business Studies 43 (1): 18–27. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2011.43.Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Women’s Labour Market Attachment and the Gender Wealth Gap

- Terror in the City: Local Terrorism and Firm Exports

- Achievement Effects of Dual Language Immersion in One-Way and Two-Way Programs: Evidence from a Statewide Expansion

- Test Endurance and Remedial Education Interventions: Good News for Girls

- Patent Clearinghouse and Technology Diffusion: What is the Contribution of Arbitration Agreements?

- How Much Competition is Enough Competition for Regulatory Forbearance?

- Waiting for the Weekend – The Adoption and Proliferation of Weekend Feeding (“BackPack”) Programs in Schools

- The Effect of Inheritance Receipt on Labor Supply: A Longitudinal Study of Japanese Women

- Letters

- Time Preferences and Lunar New Year: An Experiment

- Outsourcing Child Labor

- Future Focus is Surprisingly Linked with Prioritizing Work–Life Balance over Long-Term Savings

- Inmate Assistance Programs

- On Plaintiffs’ Strategic Information Acquisition and Disclosure during Discovery

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Women’s Labour Market Attachment and the Gender Wealth Gap

- Terror in the City: Local Terrorism and Firm Exports

- Achievement Effects of Dual Language Immersion in One-Way and Two-Way Programs: Evidence from a Statewide Expansion

- Test Endurance and Remedial Education Interventions: Good News for Girls

- Patent Clearinghouse and Technology Diffusion: What is the Contribution of Arbitration Agreements?

- How Much Competition is Enough Competition for Regulatory Forbearance?

- Waiting for the Weekend – The Adoption and Proliferation of Weekend Feeding (“BackPack”) Programs in Schools

- The Effect of Inheritance Receipt on Labor Supply: A Longitudinal Study of Japanese Women

- Letters

- Time Preferences and Lunar New Year: An Experiment

- Outsourcing Child Labor

- Future Focus is Surprisingly Linked with Prioritizing Work–Life Balance over Long-Term Savings

- Inmate Assistance Programs

- On Plaintiffs’ Strategic Information Acquisition and Disclosure during Discovery