Making the Connection: Using Concept Mapping to Bring the Basic Sciences to the Diagnosis

-

Douglas B. Spicer

Abstract

Although medical education has historically emphasized the role and importance of basic science in clinical reasoning, educators have struggled to teach basic science to optimize its use for students. Concept mapping helps students develop relationships between basic and clinical science, which can enhance understanding of the material. Educators at the University of New England College of Osteopathic Medicine developed a weekly concept-mapping activity connecting biomedical principles with clinical signs, symptoms, and laboratory values from a comprehensive clinical case. This activity elicits cross-disciplinary discussion, illustrates content integration by the students, and enhances faculty collaboration across disciplines.

Medical education has historically emphasized the role and importance of basic science since the Flexner report1 was published. However, educators have struggled with how best to teach basic science to optimize its utility for students. The concept of cognitive integration in medicine refers to “the creation of integrated understanding of basic and clinical sciences within the mind of the individual learner.”2 Many studies indicate the importance of integrating the basic and clinical sciences for diagnostic reasoning.2 Simply integrating the curriculum by teaching basic and clinical sciences next to each other is not sufficient; the integration must occur within each teaching session.3 To best achieve cognitive integration, the relationships between the basic science and clinical domains need to be explicitly demonstrated to students.4 Therefore, students should be given strategies to actively integrate and synthesize this information.

Concept mapping, which is “a diagrammatic representation of ‘meaningful’ relationships between concepts,”5 helps students develop relationships between the basic and clinical science domains and enhances understanding of the material.6 Previous studies6-8 have indicated that concept mapping helps students develop meaningful learning and integrate basic and clinical science information, and these results were demonstrated independent of the students’ learning styles. Furthermore, concept mapping facilitates group and collaborative learning when used as a group task.9-11

In 2006, we created a course at University of New England College of Osteopathic Medicine that replaced some of the traditional lecture-based educational experiences with more active learning pedagogies to allow students to integrate basic science with clinical sciences. The course was also designed to develop team-building skills to prepare students for the clinical working environment. We adopted a case-based model based on the principles of team-based learning as described by Michaelsen et al.12 Concept mapping addressed the challenge of developing clinical case-based application exercises that helped to create highly functioning teams and ensured that students made connections between the basic science and clinical concepts.

In 2012, this model was used for a year-long osteopathic medical knowledge course during the first year. The course was taught by basic scientists and physicians using clinical correlations to integrate the basic science disciplines. The curricular framework included weekly clinical case-based concept-mapping exercises similar to those we had developed in 2006. Detailed grading rubrics for the concept maps were created for each case to provide more guidance, informational feedback, and instructor scaffolding for the students.13,14 For these exercises, students worked in the same group of 6 for the entire year, and almost all of the groups went through the stages of group development described by Tuckman15 of “forming,” “storming,” “norming,” and most reached the final stage of “performing” as a very effective team.

Designing Concept-Mapping Sessions

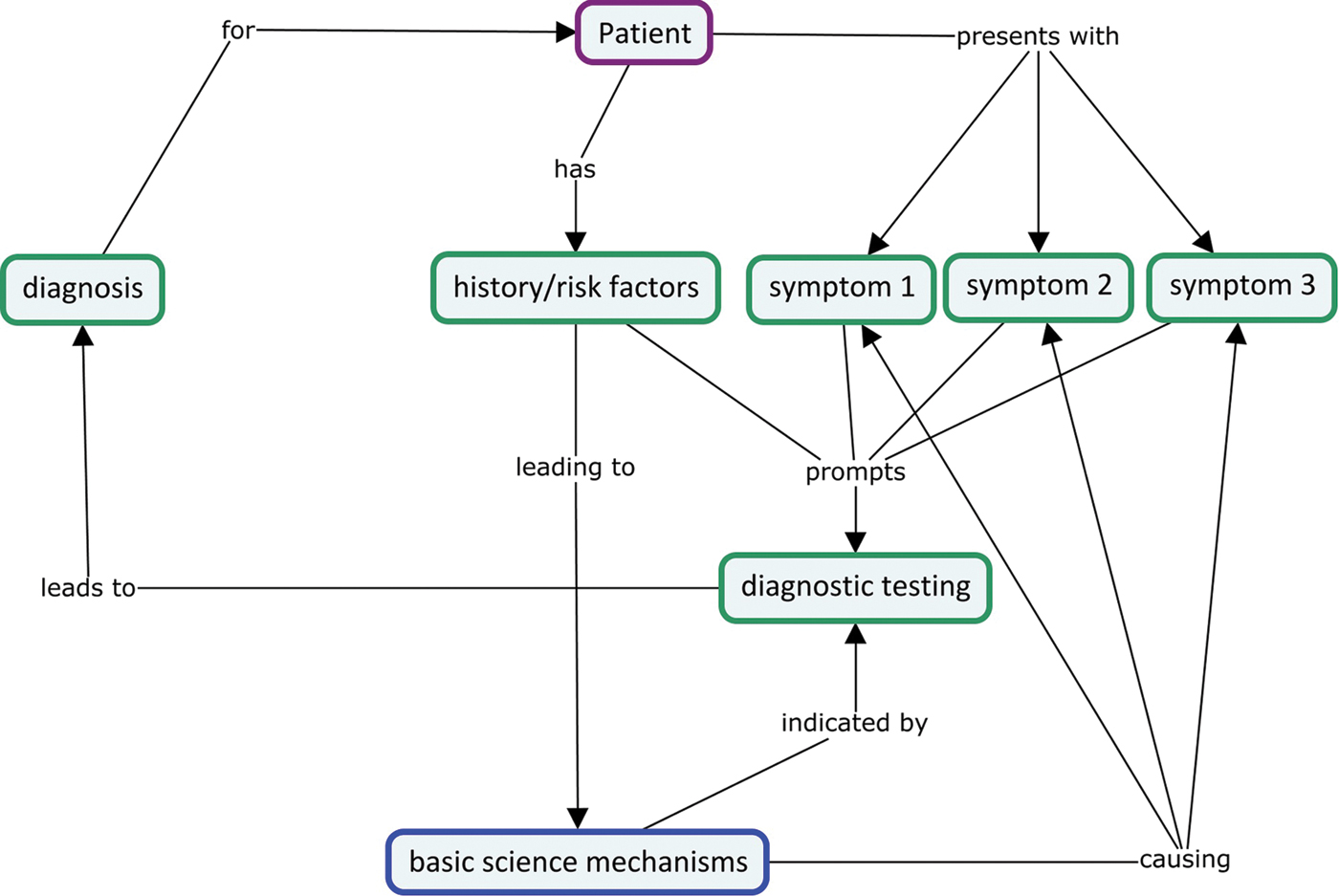

The concept mapping exercise helped students visualize how the basic science concepts explained the clinical presentation's pathophysiologic characteristics in a specific case. This approach helped students focus on the patient. Students started and ended their concept map with the patient (Figure 1). The map contained basic science concepts that explained the basis of the clinical concepts, which included the clinical symptoms, signs, and the diagnostic test results. The students arranged these concepts by linking terms to create logical connections that could be followed from the patient through every part of the map.

A simplified concept map exemplifying how students might move from the patient to the clinical signs, symptoms, and history and link the basic science concepts and diagnostic tests to support the diagnosis. Depending on the prompt, treatment and its effects may be linked to these concepts.

The materials for the case-based learning (CBL) activity were designed through collaboration between basic science faculty and physicians and included the clinical case, prompt, rubric, and an exemplar concept map. The case included a complete history, physical examination, diagnosis, diagnostic tests, and management. The faculty decided on a prompt to limit the scope of the basic science and clinical concepts for the concept map based on the learning objectives for the week. The prompt helped direct the students to explain the underlying pathophysiologic characteristics and defend their primary diagnosis by connecting the key elements of the history, physical examination, and diagnostic tests. In addition, the students used these elements informed their decisions regarding treatment and management as appropriate (eAppendix 1). Once the prompt was generated, the faculty developed an example concept map and a rubric that outlined the information on the concept map to help facilitators guide their groups (eAppendix 2 and eAppendix 3).

A meeting was convened a week before each concept mapping session to prepare the faculty facilitators and standardize the experience for each group. In these meetings, a physician presented the case providing a clinical perspective for the facilitators, who were often basic scientists. The basic science and clinical concepts underpinning the patient's clinical presentation were presented by the faculty who generated the rubric and concept map for the case (eAppendix 2 and eAppendix 3). These sessions oriented the facilitators to the content and instructed them on how to guide the students through the session.

Implementation

Each CBL group, which comprised 6 students and a facilitator, met weekly for the 2-hour concept mapping session. Students were provided with the case and prompt ahead of time to prepare for the session. The session began with 1 student giving an oral presentation of the case, which included identification of the key elements of the history, physical examination, and diagnostic tests that informed the diagnosis. This activity required the students to explore the connections between the basic science and clinical domains, which were centered on the patient's clinical presentation and provided an opportunity for students to practice presentation skills.

The students used the prompt to create their concept map using CmapTools (IHMC). The map was projected on a large monitor to allow the whole group to view its construction. The discussion centered on reaching consensus about concept placement and linking terms. The group was required to use all of the terms provided in the prompt on their concept map, and they were encouraged to also add their own concepts to describe certain processes better. Students referred to lectures and other resources from the week, and substantial peer-to-peer teaching occurred. The rubric and exemplar concept map were provided as a resource for the facilitator, whose role was to keep the students focused on the appropriate concepts without being too directive or restrictive. The facilitator also provided guidance on group process as the students engaged in decision-making, task performance, and conflict resolution.

Grading

To provide immediate feedback to the group on their concept map, the faculty-generated rubric and concept map were available to students after completion of their map (eAppendix 2 and eAppendix 3). Before grading, the maps were deidentified and coded to prevent bias. The maps were initially graded by second-year students who used the rubric and exemplar concept map to grade and provide commentary. The final grade was determined by 2 faculty facilitators whose responsibility was to review the maps and standardize the grading process. Facilitators were not assigned to review and grade the map of their own group(s). The activity was designed primarily as an opportunity for learning rather than assessment, so grading was primarily formative, but with enough weight to be taken seriously. The concept maps were graded using a 20-point scale. A total of 4 points were given for including all of the required basic science and clinical concepts on the map. The remaining 16 points were designated for the content on the map. Rather than assigning specific point amounts for each correct link made, the point distribution was more subjective, with more weight given to important general concepts rather than every specific detail. Identifying the important concepts and realizing that they can be shown in different ways on a concept map took some practice for the student graders. The faculty who supervised them provided feedback, and they soon became adept at grading. Having experienced concept mapping during the previous year, their comments were very relevant and they often identified bridges between the first- and second-year curriculum, as well as the board examinations. First-year students responded to these comments by incorporating the feedback into their subsequent maps.

Before returning the graded concept maps to the groups, the numeric score was converted to an “exceeds expectations” (18-20 points), “meets expectations” (16-<18 points), and “needs improvement” (<16 points). Groups receiving a “needs improvement” grade were required to meet with the faculty member who graded the concept map to review the map, clarify any misconceptions, and edit their map based on the comments.

Benefits

Concept mapping, as described in this article, is a method to integrate basic science concepts with clinical medicine. Since 2014, course evaluations have indicated that at least 80% of students agreed or strongly agreed with the statement, “The Facilitated Case Based Learning activities (CBL)/Concept Mapping provided opportunities to integrate the basic science and clinical science concepts from the objectives.” Student comments from the course evaluation suggested that concept mapping helped them to contextualize basic science concepts underpinning clinical medicine (Figure 2). The process of discussing concepts to reach a consensus on the map challenged students to defend their understanding and explain their rationale to others. Others have shown that this enhances learning and retention of the material.6,16 Many students also found the maps to be useful study tools. Additionally, working in these small-group sessions helped students understand the elements of effective team dynamics and reflect on their strengths and weaknesses.

Comments from first-year students at the University of New England College of Osteopathic Medicine who participated in concept-mapping sessions. Abbreviation: CBL, case-based learning.

Second-year student graders found the experience helpful for reviewing basic science concepts and appreciated revisiting first-year content as they prepared for the board examinations. Concept map grading allowed these students to practice assessment and provide constructive feedback.

The collaborative effort to create materials for each concept mapping session brought faculty from different basic science and clinical disciplines together, and basic scientists learned which concepts are critical for application to clinical medicine. These experiences helped faculty to understand the importance of integration and develop new skills to emphasize this in their teaching.

The process of concept mapping can be challenging for both students and faculty. Robust orientation programs to help faculty and students appreciate the value of cognitive integration for developing clinical reasoning skills can help address these challenges. Students and facilitators should be educated about team building and supported throughout the process of team development.

Conclusion

Concept mapping provided rich discussion between students about the basic sciences in a clinical context. Through this interaction, students challenged each other and their perceptions to create an integrated understanding of the basic and clinical sciences. Providing focused prompts and relevant concepts were important to promote a discussion that achieved cognitive integration to enhance clinical reasoning. Our approach of having the same groups of students work together for the entire year gave them the time to work through the different stages of team development and become productive team members. These acquired skills are critical for students in their clinical practice, particularly in the environment of team-based patient-centered care.

References

1. FlexnerA.Medical Education in the United States and Canada: A Report to the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. Bulletin No. 4. Updyke; 1910.Search in Google Scholar

2. BandieraG, KuperA, MylopoulosM, et al.. Back from basics: integration of science and practice in medical education. Med Educ. 2018;52(1):78-85. doi:10.1111/medu.13386Search in Google Scholar PubMed

3. KulasegaramKM, MartimianakisMA, MylopoulosM, WhiteheadCR, WoodsNN. Cognition before curriculum: rethinking the integration of basic science and clinical learning. Acad Med. 2013;88(10):1578-1585. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182a45defSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

4. KulasegaramK, ManzoneJC, KuC, SkyeA, WadeyV, WoodsNN. Cause and effect: testing a mechanism and method for the cognitive integration of basic science. Acad Med. 2015;90:S63-S69. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000896Search in Google Scholar PubMed

5. WatsonGR. What is… concept mapping?Med Teach. 1989;11(3-4):265-269. doi:10.3109/01421598909146411Search in Google Scholar PubMed

6. DaleyBJ, TorreDM. Concept maps in medical education: an analytical literature review. Med Educ. 2010;44(5):440-448. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03628.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

7. LaightDW. Attitudes to concept maps as a teaching/learning activity in undergraduate health professional education: influence of preferred learning style. Med Teach. 2004;26(3):229-233. doi:10.1080/0142159042000192064Search in Google Scholar PubMed

8. KostovichCT, PoradziszM, WoodK, O'BrienKL. Learning style preference and student aptitude for concept maps. J Nurs Educ. 2007;46(5):225-231. doi:10.3928/01484834-20070501-06Search in Google Scholar PubMed

9. van BoxtelC, van der LindenJ, RoelofsE, ErkensG. Collaborative concept mapping: provoking and supporting meaningful discourse. Theory Pract. 2002;41(1):40-46.10.1207/s15430421tip4101_7Search in Google Scholar

10. HsuLL. Developing concept maps from problem-based learning scenario discussions. J Adv Nurs. 2004;48(5):510-518.10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03233.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

11. RendasAB, FonsecaM, PintoPR. Toward meaningful learning in undergraduate medical education using concept maps in a PBL pathophysiology course. Adv Physiol Educ. 2006;30(1):23-29. doi: 10.1152/advan.00036.2005Search in Google Scholar PubMed

12. MichaelsenL, KnightA, FinkL, eds. Team-Based Learning: A Transformative Use of Small Groups in College Teaching. Stylus Publishing; 2004.Search in Google Scholar

13. MoniRW, BeswickE, MoniKB. Using student feedback to construct an assessment rubric for a concept map in physiology. Adv Physiol Educ. 2005;29(4):197-203. doi:10.1152/advan.00066.2004Search in Google Scholar PubMed

14. PudelkoB, YoungM, Vincent-LamarreP, CharlinB. Mapping as a learning strategy in health professions education: a critical analysis: mapping as a learning strategy. Med Educ. 2012;46(12):1215-1225. doi:10.1111/medu.12032Search in Google Scholar PubMed

15. TuckmanBW. Developmental sequence in small groups. Psychol Bull. 1965;63(6):384-399. doi:10.1037/h0022100Search in Google Scholar PubMed

16. MorseD, JutrasF. Implementing concept-based learning in a large undergraduate classroom. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2007;7(2):243-253. doi: 10.1187/cbe.07-09-0071Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2020 American Osteopathic Association

Articles in the same Issue

- LETTERS TO THE EDITOR

- Osteopathic Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic

- EDITORIAL

- Research at University of New England College of Osteopathic Medicine

- ORIGINAL CONTRIBUTION

- Life vs Loans: Does Debt Affect Career Satisfaction in Osteopathic Graduates?

- BRIEF REPORT

- Eosinopenia and COVID-19

- JAOA/AACOM MEDICAL EDUCATION

- Learning Together: Interprofessional Education at the University of New England

- 48-Hour Hospice Home Immersion Encourages Osteopathic Medical Students to Broaden Their Views on Dying and Death

- Making the Connection: Using Concept Mapping to Bring the Basic Sciences to the Diagnosis

- Report on 7 Years’ Experience Implementing an Undergraduate Medical Curriculum for Osteopathic Medical Students Using Entrustable Professional Activities

- SPECIAL COMMUNICATION

- Forty Years of University of New England's Research and Scholarship and its Impact in Maine, New England, and Beyond

- CLINICAL IMAGES

- Undifferentiated Pleomorphic Sarcoma

Articles in the same Issue

- LETTERS TO THE EDITOR

- Osteopathic Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic

- EDITORIAL

- Research at University of New England College of Osteopathic Medicine

- ORIGINAL CONTRIBUTION

- Life vs Loans: Does Debt Affect Career Satisfaction in Osteopathic Graduates?

- BRIEF REPORT

- Eosinopenia and COVID-19

- JAOA/AACOM MEDICAL EDUCATION

- Learning Together: Interprofessional Education at the University of New England

- 48-Hour Hospice Home Immersion Encourages Osteopathic Medical Students to Broaden Their Views on Dying and Death

- Making the Connection: Using Concept Mapping to Bring the Basic Sciences to the Diagnosis

- Report on 7 Years’ Experience Implementing an Undergraduate Medical Curriculum for Osteopathic Medical Students Using Entrustable Professional Activities

- SPECIAL COMMUNICATION

- Forty Years of University of New England's Research and Scholarship and its Impact in Maine, New England, and Beyond

- CLINICAL IMAGES

- Undifferentiated Pleomorphic Sarcoma