Choosing Primary Care: Factors Influencing Graduating Osteopathic Medical Students

-

Katherine M. Stefani

Abstract

Context

Access to primary care (PC) improves health outcomes and decreases health care costs. The shortage of PC physicians and shifting physician workforce makes this an ongoing concern. Osteopathic medical schools are making strides to fill this void. Considering the critical need for PC physicians in the United States, this study aims to identify factors related to choosing a PC specialty.

Objective

To understand possible motivations of osteopathic medical students pursuing a career in PC specialties by examining the role of sex and the influence of 5 key factors in this decision.

Methods

Responses from the annual American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine graduate survey (2007-2016) were analyzed. Self-reported practice decision considerations of 5 key factors, including (1) intellectual and technical content, (2) debt level, (3) lifestyle, (4) prestige/income level, and (5) personal experience and abilities were summarized, and their subjective value was contrasted between osteopathic medicine graduates pursuing PC specialties vs those pursuing non-PC specialties.

Results

The mean percentage of graduates pursuing PC and non-PC specialties from 2007 to 2016 was 31.3% and 68.7%, respectively. Women were 1.75 times more likely to choose PC than men (95% CI, 1.62-1.89). Regardless of specialty choice, lifestyle was the most important factor each year (1027 for PC [75.3%] vs 320 for non-PC [63.3%] in 2016; P<.0001). Students entering PC were more likely to report prestige and income level to be “no or minor influence” compared with students entering non-PC specialties (P<.0001). Debt level was more likely to be a “major influence” to students choosing to enter non-PC specialties than to those entering PC (P<.0001), and the percentage of non-PC students has grown from 383 in 2007 (22.9%) to 833 in 2016 (30.6%).

Conclusion

Sex was found to significantly influence a graduate's choice of specialty, and female graduates were more likely to enter practice in PC. Each of the 5 survey factors analyzed was significantly different between students entering PC and students entering non-PC specialties. Lifestyle was deemed a major influencing factor, and responses suggested that debt level is a strong influencing factor among students pursuing non-PC specialties.

As health care reform continues to evolve in the United States, the common goals of improving health outcomes and decreasing health care expenditures have persisted. Routine access to primary care (PC) is a critical mechanism required to achieve these goals; even 1 additional PC physician per 10,000 persons in a population decreases emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and elective operations.1-3 However, with the shortage of PC physicians and rapid attrition of the current workforce, increasing access to PC is problematic.2 In the 2017 update4 by the Association of American Medical Colleges, the projected 2030 shortfalls in PC range between 7300 and 43,100 physicians. In family medicine, the number of residency positions has risen steadily over the past 9 years, and the 2018 residency match had the highest fill rate in history at 96.7%.5 With only 3.3% of family medicine residency spots open, the current education pipeline is full. The geographic maldistribution of PC physicians is an added concern. There is a large discrepancy in the distribution of PC physicians between Mississippi, the state with the lowest number of PC physicians (1925; 64.4/100,000 residents), and Massachusetts, the state with the highest number of PC physicians (9156; 134.4/100,000 residents).6

Today, 1 in 4 US medical students graduate from an osteopathic medical school, yielding more than 6500 new osteopathic physician graduates annually.7 Furthermore, osteopathic medical schools are responsible for training a large portion of PC physicians, with an estimated 56% of current osteopathic physicians practicing in a PC field.7 The proportion of women actively practicing osteopathic medicine has also increased, from 18% in 1993 to 42% today.8 As a result of these trends, 74% of actively practicing female osteopathic physicians in the United States are under the age of 45.8

Given the importance of PC to health outcomes, understanding the components that attract or deter medical students from entering PC fields has received considerable attention in the literature. Among allopathic graduates, several factors have been cited to account for the movement away from PC, including rising educational debt, a “controllable lifestyle,” prestige, and prospective income.9,10 Published factors associated with allopathic students choosing PC include the female sex, having a rural upbringing, planning to practice in a rural community, having lower income expectations, and attending a public medical school.11 But do these findings generalize to a contemporary physician workforce and a growing osteopathic cohort? The question is legitimate given highlighted differences between the osteopathic and allopathic cohorts in relation to how debt influences specialty selection. Studies12-16 attempting to link debt and specialty selection among allopathic medical students have routinely been uncorrelated or mixed. With notable confounders such as underlying sociodemographics playing a role, debt has proven to be an influential variable in osteopathic graduates in a contemporary cohort, especially in relation to access to loan-forgiveness programs.17

Considering the critical need for PC physicians in the United States, the increasing heterogeneity of the physician workforce, the increase in graduates from osteopathic medical schools, and differences in osteopathic and allopathic cohorts, we sought to understand how various factors, including sex, influence PC selection and which elements are prioritized in a contemporary osteopathic cohort.

Methods

The American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine (AACOM) administers a voluntary annual survey to all students graduating from osteopathic medical schools. This survey gathers information on graduate demographics, medical school training, anticipated career path, and other metrics. We obtained de-identified data, with the permission of AACOM, from 2007, 2010, 2013, and 2016 survey results. This time frame was chosen to examine how determinants of PC selection have transformed longitudinally. Responses to the following questions from 2007, 2010, 2013, and 2016 were analyzed: (1) “Select 1 specialty in which you are most likely to work or seek training,” and (2) “Please indicate the importance of each of the following factors affecting your specialty choice decision.”

To contrast the perceived importance of various factors between groups, respondents were divided into PC or non-PC groups depending on their declared specialty. Primary care was defined as pursuing a career in family medicine, general internal medicine, general pediatrics, or geriatrics.5,7 Although AACOM defines PC as the disciplines of family medicine, general internal medicine, and general pediatrics,18 we also included geriatrics given the high degree of practice overlap and the tendency of geriatricians to identify as PC phyisicans.19 The non-PC category included all other specialties. The influence of sex on the decision to pursue a career in PC was analyzed, and 5 key factors, including (1) intellectual and technical content of the specialty, (2) debt level, (3) lifestyle, (4) prestige/income level, and (5) personal experience and abilities, were summarized. The subjective value of those factors was contrasted between students pursuing PC vs those who were not. This study was approved by the institutional review board at Midwestern University (Glendale, Arizona).

The distribution of responses was tabulated for each of the 5 self-reported factors across a 5-point Likert scale (major influence, strong influence, moderate influence, minor influence, no influence). χ2 analyses were performed to evaluate differences between those planning to enter a PC specialty compared with those who were not. We assessed relationships of interest, including the association between sex and PC selection, using a multivariable proportional odds ratio (OR) model with logistic regression. Statistical significance was indicated by P<.05. Categorical data were expressed as the number of respondents and percentage of the sample. SAS software, version 3.7 (SAS Institute, Inc.) was used for statistical analysis.

Results

Survey responses increased from 2403 in 2007 to 4191 in 2016 as graduating osteopathic class sizes increased nationwide. Although participation in the survey was optional, response rates ranged between 72% and 77% from 2007 to 2016. We included data from 12,887 surveys (6207 women and 6670 men), which comprised all surveys without missing responses (288 surveys) to the analyzed variables. Figure 1 depicts the consistent trend in specialty choice among graduating students, with the majority choosing to pursue careers in non-PC areas. The percentage of osteopathic medical students entering PC between 2007 and 2016 gradually increased (675 [28%] and 1345 [33%], respectively). The number of men pursuing PC increased from 2007 to 2010 (248 [21%] to 581 [26%], respectively).

Percentage of declared specialty by year.

More women (2358 [57.7%]) planned to enter PC fields compared with men (1729 [42.3%]; OR, 1.75; 95% CI, 1.62-1.89), and sex was found to be associated with differences in choosing a specialty (P<.0001). In the sex-stratified analyses, the percentage of women (427 in 2007 [35.1%] to 764 in 2016 [41.0%]) and men (248 in 2007 [21.1%] to 581 in 2016 [26.8%]) entering PC demonstrated a modest increase since 2007. In the results of the logistic regression analysis, women remained more likely to select PC than men for each year analyzed. For example, in 2007, women were 2.02 times more likely to choose PC (95% CI, 1.68-2.42), and in 2016, this OR dropped to 1.89 (95% CI, 1.66-2.16; Table). In the linear regression, sex had a significant effect on each of the 5 influencing survey factors (P<.0006).

Distribution of Osteopathic Medical Students Into Primary Care and Non–Primary Care Specialties by Sex and Yeara

| Yearsb | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | 2007 | 2010 | 2013 | 2016 | All |

| OR (95% CI) | 2.02 (1.68-2.42) | 1.60 (1.36-1.87) | 1.62 (1.41-1.87) | 1.89 (1.66-2.16) | 1.75 (1.62-1.89) |

| Women | 1216 | 1439 | 1687 | 1865 | 6207 |

| Primary carec | 427 (35.1) | 528 (36.7) | 639 (37.9) | 764 (41.0) | 2358 |

| Non–primary carec | 789 (64.9) | 911 (63.3) | 1048 (62.1) | 1101 (59.0) | 3849 |

| Men | 1173 | 1432 | 1901 | 2164 | 6670 |

| Primary care | 248 (21.1) | 381 (26.6) | 519 (27.3) | 581 (26.8) | 1729 |

| Non–primary care | 925 (78.9) | 1051 (73.4) | 1382 (72.7) | 1583 (73.2) | 4941 |

| Total | 2389 | 2871 | 3588 | 4029 | 12,877 |

aP<.0001 for the association between sex and specialty for each year.

b Data are given as No. (%) unless otherwise indicated.

cP<.05 for the association between sex and year for each specialty.

Abbreviation: OR, odds ratio.

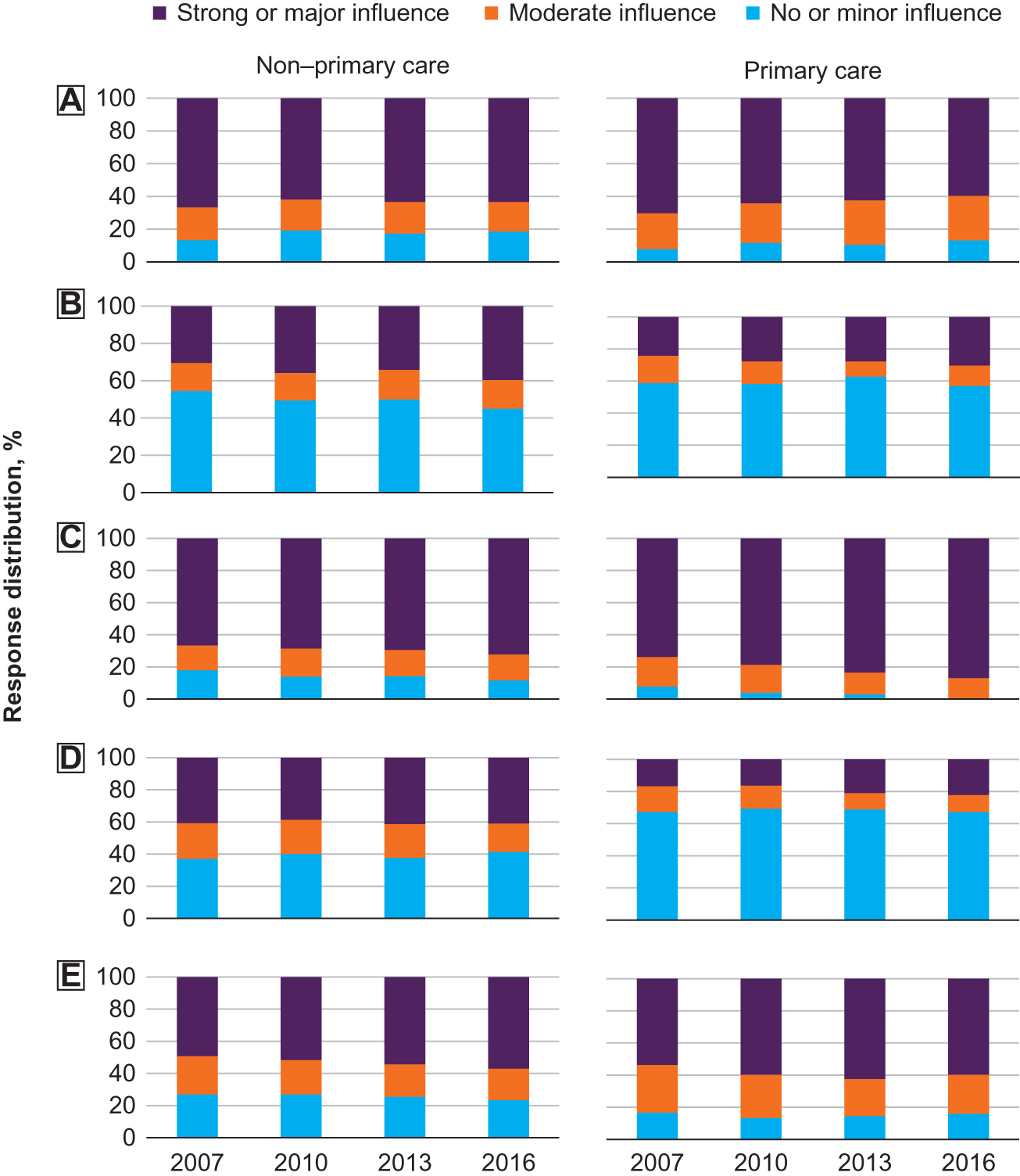

Among self-reported factors, lifestyle was the most important element in specialty choice each year for all students (P<.0001). For students entering PC, the percentage of students reporting that lifestyle was a “major influence” increased gradually from 397 (60.1%) in 2007 to 1027 (75.3%) in 2016. A similar trend was observed among students entering non-PC specialties, with increases from 966 in 2007 (57.5%) to 1729 in 2016 (63.3%). Students entering PC were more likely to report prestige and income level to be “no influence” or a “minor influence” compared with students entering non-PC specialties (P<.0001). Debt level was more likely to be a “major influence” for students choosing to enter non-PC specialties than it was for those entering PC (P<.0001), and this percentage of students entering non-PC specialties increased from 393 in 2007 (22.9%) to 833 in 2016 (30.6%). The intellectual and technical content of the specialty was of great importance to more students entering non-PC specialties (1005 [36.7%]) than it was students entering PC (354 [25.9%]) in 2016. Last, students entering PC and non-PC both reported similar frequencies across the Likert scale when rating the importance of one's personal experience and abilities in choosing a specialty (Figure 2).

Response distribution (%) of the influence of 5 key factors in an osteopathic medical student's choice to pursue primary care or a non–primary care specialty by year. (A) intellectual and technical content of the specialty; (B) debt level; (C) lifestyle; (D) prestige; (E) personal experience and abilities.

Discussion

Primary care is the cornerstone of medical care delivery in the United States; adequate access to PC improves health outcomes and plays a role in cost mitigation.1-3 As PC shortages remain, it is important to understand the factors that influence and predict an osteopathic graduate ultimately choosing to practice PC.

Previous efforts have attempted to understand the multifaceted factors that may influence a medical student's choice of practice. In a broad review of the literature, Bennett et al11 identified 5 factors highly associated with choosing PC: female sex, a rural background, planning to practice in a rural community, low-income expectation, and attending a public medical school. In a different study20 of allopathic medical students, female sex was found to be strongly associated with pursuing a career in PC in an analysis of more than 100,000 graduates from 1997 to 2006. The number of students entering PC between 1997 and 2006 declined from 60.7% to 42.1%,20 respectively. However, the increase in female allopathic graduates was proposed to have attenuated this decline.9 Although the findings from these studies9,20 are suggestive, both are older and based on an allopathic cohort. Individual factors that attract a student to pursue an education at an osteopathic instead of an allopathic medical school may suggest that conclusions reached in an allopathic cohort cannot be generalized to include osteopathic graduates.

Although there was a notable increase in men pursuing PC from 2007 to 2010 (21% to 26%) in the current study, the rates were largely flat from 2010 to 2016 (Table). The rates of women entering PC increased each year, while women decreased from 51% of the total osteopathic graduates in 2007 to only 46% in 2016. This finding suggests that while the representation of women among graduates decreased, PC became an increasingly popular choice for women, which should add further credence to the statistically significant OR of the representation of women to men in PC of 1.75 from 2007 to 2016.

Differences in sex representation among specialties have been hypothesized to be related to women seeking careers that offer more work-life-family balance. However, some studies21-23 found that women also pursue careers associated with uncontrollable lifestyles, including PC specialties and obstetrics and gynecology, whereas men were found to favor surgical specialties and other controllable lifestyle specialties (eg, emergency medicine, radiology, ophthalmology, anesthesiology, and dermatology).21-23

Osteopathic medical schools have invested heavily to increase the number of graduates who pursue PC; many schools stress the importance of producing graduates who practice PC in their mission statements,24-29 and their recruitment patterns likely reflect these stated goals. Other strategies to increase PC graduates have been reported; for example, Lake Erie College of Medicine initiated a 3-year accelerated PC program in 2010.30,31

Each of the 5 survey factors analyzed was significantly different between students entering PC and those entering non-PC specialties. Lifestyle was deemed a major influencing factor each year, and respondents suggested that the debt level was perceived as a strong influencing factor among students pursuing non-PC specialties, which are typically associated with higher compensation. The potential lifestyle permissible by certain specialties is a major influencing factor among medical school graduates since 1990 and has been attributed to the shifts in specialty choices since that time.32-34 In the AACOM survey,18 lifestyle was defined as having predictable working hours and sufficient time for family and deemed the most important factor for all students regardless of their choice of practice. The interpretation of controllable lifestyle specialties is subjective, and may have been influenced by the subjective nature of the survey in general, as well as other potential factors not able to be captured through the current study design.

In the setting of rising debt burdens, the relationship between debt and specialty selection has been the subject of several studies.13-17 Although 1 study14 found that students with higher debt burdens tended to pursue higher-paid specialties, several studies13,15-17 have not found debt to be an influential factor. A 2019 study17 demonstrated that the use of loan forgiveness programs mitigated the effect of debt on specialty selection. Students with higher burdens of debt and who did not use such programs were less likely to pursue PC specialties.

The current study has several limitations. Survey questions about intended practice plans may not have reflected actual residency choice or practice pursued after residency. However, most surveys were administered at the end of the final year of medical school and after Match Day; thus, responses should be largely congruent with final specialty destination. The survey was retrospective, and although the current study used a large sample population and included data spanning 10 years, we were limited by the confines of the predetermined survey that is disseminated annually by AACOM. Therefore, we were limited by the scope to which we could explore other potentially important factors that may have influenced specialty choice.

Although previous studies10,14,20,21,23,34,35 have shown that demographics influence practice selection, no demographic information beyond sex were included in our analyses. Factors such as socioeconomic status, race, marital status, and board scores are variables that could influence graduate specialty selection but were not analyzed in this study because these data were either not available under our data use agreement or not collected through the AACOM survey. Further analyses are recommended to understand how these and other factors influence students’ choice of practice, especially in light of findings35 indicating that the percentage of women entering osteopathic medical schools has been declining since 2004. More investigation of whether medical school experiences, such as mentoring and clerkship opportunities (which may garner or reinforce student interest in PC) influence specialty selection is warranted. Studies regarding the geographic locale of a medical school and the size of the community in which it operates are also needed.

Additionally, there is variation within PC pertaining to controllable vs uncontrollable work lifestyle (eg, ambulatory only practice vs PC with inpatient call vs full concierge practice models), and respondents likely have varying interpretations of what is deemed a controllable vs uncontrollable lifestyle in the context of specialty selection. Career planning and specialty selection decisions are multifactorial, and we cannot make conclusive predictions based on this study's results. Constructing causal determinations is beyond the scope of this study. However, our data showed an association between being a woman and the likelihood to choose a PC specialty. Further studies that link osteopathic physician specialty choice and longitudinal practice patterns would offer additional insight; an osteopathic equivalent of the American Medical Association Master File data repository might enable such research.

Conclusion

Increasing rates of PC choice by osteopathic medical school graduates are being driven by female students. Though previous research has been inconclusive about relationships between influencing monetary and social factors on medical trainee practice choices, the clear differences between these influencing survey factors in terms of sex may provide avenues for future research. Further research could illuminate methods for shifting interest in PC practice in future medical graduates.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Mayo Clinic and AACOM for their support of this analysis.

Author Contributions

Student Doctor Stefani and Drs Richards and Scheckel provided substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; all authors drafted the article or revised it critically for important intellectual content; all authors gave final approval of the version of the article to be published; and all authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

References

1. StarfieldB, ShiL, MacinkoJ. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83(3):457-502. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00409.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

2. Council on Graduate Medical Education. Advancing Primary Care. Health Services and Resources Administration; 2010. https://www.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/hrsa/advisory-committees/graduate-medical-edu/reports/archive/2010.pdf. Accessed May 1, 2020.Search in Google Scholar

3. Why primary care matters. American Academy of Family Physicians website. https://www.aafp.org/medical-school-residency/choosing-fm/value-scope.html. Accessed September 4, 2018.Search in Google Scholar

4. IHS Markit. The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections From2015to 2030. Association of American Medical Colleges; 2017. https://aamc-black.global.ssl.fastly.net/production/media/filer_public/a5/c3/a5c3d565-14ec-48fb-974b-99fafaeecb00/aamc_projections_update_2017.pdf. Accessed May 1, 2020.Search in Google Scholar

5. FamilyMedicine2020 National Resident Matching Program (NRMP) Results Analysis. American Academy of Family Physicians. website. https://www.aafp.org/medical-school-residency/program-directors/nrmp.html. Accessed April 29, 2020.Search in Google Scholar

6. Association of American Medical Colleges. 2017 State Physician Workforce Data Report. Association of American Medical Colleges; 2017. https://store.aamc.org/downloadable/download/sample/sample_id/30/Search in Google Scholar

7. American OsteopathicAssociation. 2016 Osteopathic Medical Profession Report. American Osteopathic Association; 2016. https://osteopathic.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/2016-OMP-report.pdf Accessed December 26, 2017.Search in Google Scholar

8. American OsteopathicAssociation. 2019 Osteopathic Medical Profession Report. American Osteopathic Association; 2020. https://osteopathic.org/wp-content/uploads/OMP2019-Report_Web_FINAL.pdf. Accessed May 14, 2020.Search in Google Scholar

9. Resneck JSJr. The influence of controllable lifestyle on medical student specialty choice. Virtual Mentor. 2006;8(8):529-532. doi:10.1001/virtualmentor.2006.8.8.msoc1-0608Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. XuG, RattnerSL, VeloskiJJ, HojatM, FieldsSK, BarzanskyB. A national study of the factors influencing men and women physicians’ choices of primary care specialties. Acad Med. 1995;70(5):398-404. doi:10.1097/00001888-199505000-00016Search in Google Scholar PubMed

11. BennettKL, PhillipsJP. Finding, recruiting, and sustaining the future primary care physician workforce: a new theoretical model of specialty choice process. Acad Med. 2010;85(10 suppl):S81-S88. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181ed4baeSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

12. TeitelbaumHS, EhrlichN, TravisL. Factors affecting specialty choice among osteopathic medical students. Acad Med. 2009;84(6):718-723. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181a43c60Search in Google Scholar PubMed

13. KahnMJ, MarkertRJ, LopezFA, SpecterS, RandallH, KraneNK. Is medical student choice of a primary care residency influenced by debt?Med Gen Med. 2006;8(4):18.Search in Google Scholar

14. RosenblattRA, AndrillaCH. The impact of U.S. medical students’ debt on their choice of primary care careers: an analysis of data from the 2002 medical school graduation questionnaire.Acad Med. 2005;80(9):815-819. doi:10.1097/00001888-200509000-00006Search in Google Scholar PubMed

15. FrankE, FeinglassS. Student loan debt does not predict female physicians’ choice of primary care specialty. J Gen Intern Med.1999;14(6):347-350. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.00339.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

16. SparIL, PryorKC, SimonW. Effect of debt level on the residency preferences of graduating medical students. Acad Med. 1993;68(7):570-572. doi:10.1097/00001888-199307000-00017Search in Google Scholar PubMed

17. ScheckelCJ, RichardsJ, NewmanJR, et al.. Role of debt and loan forgiveness/repayment programs in osteopathic medical graduates' plans to enter primary care.J Am Osteopath Assoc.2019;119(4):227-235. doi:10.7556/jaoa.2019.038Search in Google Scholar PubMed

18. American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine. 2015-16 Academic Year Survey of Graduating Seniors Summary. American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine; 2016.Search in Google Scholar

19. Ettinger WHJr, HazzardWR. Geriatric medicine: we are what we do. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994;42(4):453-454. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.1994.tb07498.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

20. JeffeDB, WhelanAJ, Andriole DA. Primary care specialty choices of United States medical graduates, 1997-2006. Acad Med. 2010;85(6):947-958. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181dbe77dSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

21. KuMC. When does gender matter: gender differences in specialty choice among physicians. Work Occup. 2011;38(2):221-262. doi:10.1177/0730888410392319Search in Google Scholar

22. LambertEM, HolmboeES. The relationship between specialty choice and gender of U.S. medical students, 1990-2003. Acad Med. 2005;80(9):797-802. doi:10.1097/00001888-200509000-00003Search in Google Scholar PubMed

23. BoulisAK, JacobsJA. The Changing Face of Medicine: Women Doctors and the Evolution of Health Care in America. Cornell University Press; 2008.Search in Google Scholar

24. Mission statement of the Lake Erie College of Osteopathic Medicine. Lake Erie College of Osteopathic Medicine website. https://lecom.edu/about-lecom/lecom-mission/. Accessed December 21, 2017.Search in Google Scholar

25. Our mission & vision. Touro College of Osteopathic Medicine website. https://tourocom.touro.edu/about-us/mission--vision/. Accessed December 21, 2017.Search in Google Scholar

26. Mission and vision. Pacific Northwest University of Health Sciences website. https://www.pnwu.edu/inside-pnwu/about-us/mission-and-vision. Accessed February 6, 2019.Search in Google Scholar

27. Mission, vision & guiding principles. Burrell College of Osteopathic Medicine website. https://bcomnm.org/about-bcom/the-college/mission-vision-guiding-principles/. Accessed December 21, 2017.Search in Google Scholar

28. About the college of osteopathic medicine. NYIT College of Osteopathic Medicine website. https://www.nyit.edu/medicine/about. Accessed December 21, 2017.Search in Google Scholar

29. Mission and goals. Edward Via College of Osteopathic Medicine website. http://www.vcom.edu/about/mission-and-goals. Accessed December 21, 2017.Search in Google Scholar

30. ShannonS, BuserB, HahnM, et al.. A new pathway for medical education. Health Aff. 2013;32(11):1899-1905. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0533Search in Google Scholar PubMed

31. ShannonSC, FerrettiSM, WoodD, LevitanT. The challenges of primary care and innovative responses in osteopathic education. Health Aff. 2010;29(5):1015-1022. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0168Search in Google Scholar PubMed

32. SchwartzRW, HaleyJV, WilliamsC, et al.. The controllable lifestyle factor and students’ attitudes about specialty selection. Acad Med. 1990;65(3):207-210. doi:10.1097/00001888-199003000-00016Search in Google Scholar PubMed

33. DorseyER, JarjouraD, RuteckiGW. Influence of controllable lifestyle on recent trends in specialty choice by US medical students. JAMA. 2003;290(9):1173-1178. doi:10.1001/jama.290.9.1173Search in Google Scholar PubMed

34. NewtonDA, GraysonMS, WhitleyTW. What predicts medical student career choice?J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13(3):200-203. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00057.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

35. BashaME, BauerLJ, ModrzakowskiMC, BakerHH. Women in osteopathic and allopathic medical schools: an analysis of applicants, matriculants, enrollment, and chief academic officers. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2018;118(5):331-336. doi:10.7556/jaoa.2018.064Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2020 American Osteopathic Association

Articles in the same Issue

- SURF

- Lumbar Diagnosis and Pressure Difference Variance

- OMT MINUTE

- Osteopathic Manipulative Treatment for Low Back Pain

- LETTERS TO THE EDITOR

- Influence of Research on Osteopathic Medical Student Residency Match Success

- ORIGINAL CONTRIBUTION

- How Trainees Finance Their Medical Education: Implications of Higher Education Act Reform

- Choosing Primary Care: Factors Influencing Graduating Osteopathic Medical Students

- BRIEF REPORT

- Empathy in Medicine Self and Other in Medical Education: Initial Emotional Intelligence Trend Analysis Widens the Lens Around Empathy and Burnout

- ORIGINAL CONTRIBUTION

- Implied Evidence of the Functional Role of the Rectus Capitis Posterior Muscles

- REVIEW

- The Role of Sphenobasilar Synchondrosis in Disease and Health

- CLINICAL PRACTICE

- Partnering With Patients to Reduce Firearm-Related Death and Injury

- SPECIAL COMMUNICATION

- Buying Time: Using OMM to Potentially Reduce the Demand for Mechanical Ventilation in Patients With COVID-19

- CASE REPORT

- Integrating Osteopathic Manipulative Treatment and Injections in the Diagnosis and Management of a Hip Labral Tear

- CLINICAL IMAGES

- Graves Orbitopathy

Articles in the same Issue

- SURF

- Lumbar Diagnosis and Pressure Difference Variance

- OMT MINUTE

- Osteopathic Manipulative Treatment for Low Back Pain

- LETTERS TO THE EDITOR

- Influence of Research on Osteopathic Medical Student Residency Match Success

- ORIGINAL CONTRIBUTION

- How Trainees Finance Their Medical Education: Implications of Higher Education Act Reform

- Choosing Primary Care: Factors Influencing Graduating Osteopathic Medical Students

- BRIEF REPORT

- Empathy in Medicine Self and Other in Medical Education: Initial Emotional Intelligence Trend Analysis Widens the Lens Around Empathy and Burnout

- ORIGINAL CONTRIBUTION

- Implied Evidence of the Functional Role of the Rectus Capitis Posterior Muscles

- REVIEW

- The Role of Sphenobasilar Synchondrosis in Disease and Health

- CLINICAL PRACTICE

- Partnering With Patients to Reduce Firearm-Related Death and Injury

- SPECIAL COMMUNICATION

- Buying Time: Using OMM to Potentially Reduce the Demand for Mechanical Ventilation in Patients With COVID-19

- CASE REPORT

- Integrating Osteopathic Manipulative Treatment and Injections in the Diagnosis and Management of a Hip Labral Tear

- CLINICAL IMAGES

- Graves Orbitopathy