Cynefin Framework for Evidence-Informed Clinical Reasoning and Decision-Making

-

Christian Lunghi

Abstract

Osteopathy (manipulative care provided by foreign-trained osteopaths) emphasizes manual techniques as the cornerstone of patient care. Although osteopathic medicine has been well integrated into traditional health care systems in the United States, little is known about the role of osteopathy in traditional health care systems outside the United States. Therefore, it is incumbent on the osteopathy community to gather evidence in order to practice scientifically informed effective methods. This narrative review outlines the Cynefin framework for clinical reasoning and decision-making and encourages a broadening of the evidence base among osteopaths to promote health in an interdisciplinary care setting. This review also presents the concept of an osteopath's mindline, in which the osteopath combines information from a range of sources into internalized and collectively reinforced tacit guidelines.

Public health is achievable through the science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life, and promoting health.1 The major causes of chronic illness and death can be directly related to excessive behavioral, environmental, and social stress.2,3 To promote more holistic person-centered health care,4,5 the theory of Adaptive Health Practice6 was designed to incorporate a personalized approach to health care and to motivate behaviors needed to confront challenges to reducing those stresses.7 To resolve complex illness, the World Health Organization suggests that health care systems should focus on improving different components of an individual's health over the disease that affects him or her8 and integrating adjunctive approaches to traditional medicine.9

Osteopathic manipulative therapy (OMTh; manipulative care provided by foreign-trained osteopaths) is considered useful for conditions such as acute and chronic nonspecific low back pain, dysfunctional disorders in pregnancy, headaches, irritable bowel syndrome, and chronic respiratory disorders.10 Osteopathic manipulative therapy has also been shown to reduce the length of hospital stay and costs in a large population of preterm infants11 and to promote relevant neurophysiologic effects in terms of cortical plasticity.12 Although positive effects were found in psychological, neurologic, and chronic inflammatory disease management,13-15 as well as in the fields of gynecology and obstetrics,16 further investigations with more pragmatic methods are recommended to obtain solid and generalizable results.17,18 Moreover, the differences in osteopathic practice between the United States and the rest of the world need to be considered.19,20 Osteopaths may need to implement new standards for osteopathic education and practice,21 integrating evidence-informed and anecdotal perspectives20 and paying attention to the distinct components and roles of the non-US osteopathic profession in modern integrative health care.17,22

The Italian Register of Osteopaths produced the Italian Core Competencies Framework in Osteopathy, which is based on the Italian health care system and focuses osteopathic competencies on the important health needs of the population: promotion of health and prevention, management, and support of complex illnesses.23 To achieve holistic and person-centered osteopathic care, it is crucial to contextualize evidence and use critical thinking to review traditional osteopathic principles and their application.24 The framework of the 5 structure and function models25,26 could be valuable to osteopaths for implementing scientific findings in practice and promoting an integrative approach27 that could help patients become more resilient and autonomous promoters of their own health.23 Although osteopathy has recently been recognized as a health profession in Italy, combining OMTh with traditional medicine has not yet occurred.

Implementation science is “the study of methods to promote the systematic uptake of research findings and other evidence-based practices into routine practice . . . to improve the quality and effectiveness of health services.”28 Complexity science, meanwhile, is “concerned with complex systems and problems that are dynamic, unpredictable and multi-dimensional.”29 Both implementation and complexity science involve some properties of health care systems that favor more effective, evidence-informed integrated care.30 Therefore, creating proposals and discussions about clinical reasoning and the distinctive role of osteopaths in health care processes is paramount to adapting an implementation science intervention to osteopathy. Working with the osteopathic community could facilitate ways to get osteopaths on board with an evidence-informed intervention by leading it, reflecting on progress among stakeholders, and providing feedback to participants to help embrace implementation over time. Osteopaths do not typically work with explicit codified knowledge or guidelines, but instead use knowledge in practice, combining information from a wide range of sources into internalized and collectively reinforced tacit guidelines, or mindlines, to inform their practice.31

In the present review, we sought to introduce a complex medical framework32 in osteopathic models of care that provides a common language of reference and a multidimensional-complexity-informed model to draw appropriate conclusions for insight, decisions, and actions. Through this framework, we encourage deep reflection in the osteopathy community to establish a common clinical reasoning and decision-making process that aligns with risk-based thinking and promotes health in an interdisciplinary care setting. We also describe our mindlines31 (Figure 1) as an example of osteopathic practice that needs to be negotiated through a range of informal interactions in free-flowing communities of practice, experience with patients, and consensus workshops. The resulting construct will be a day-to-day evidence-informed practice based on socially constituted knowledge.

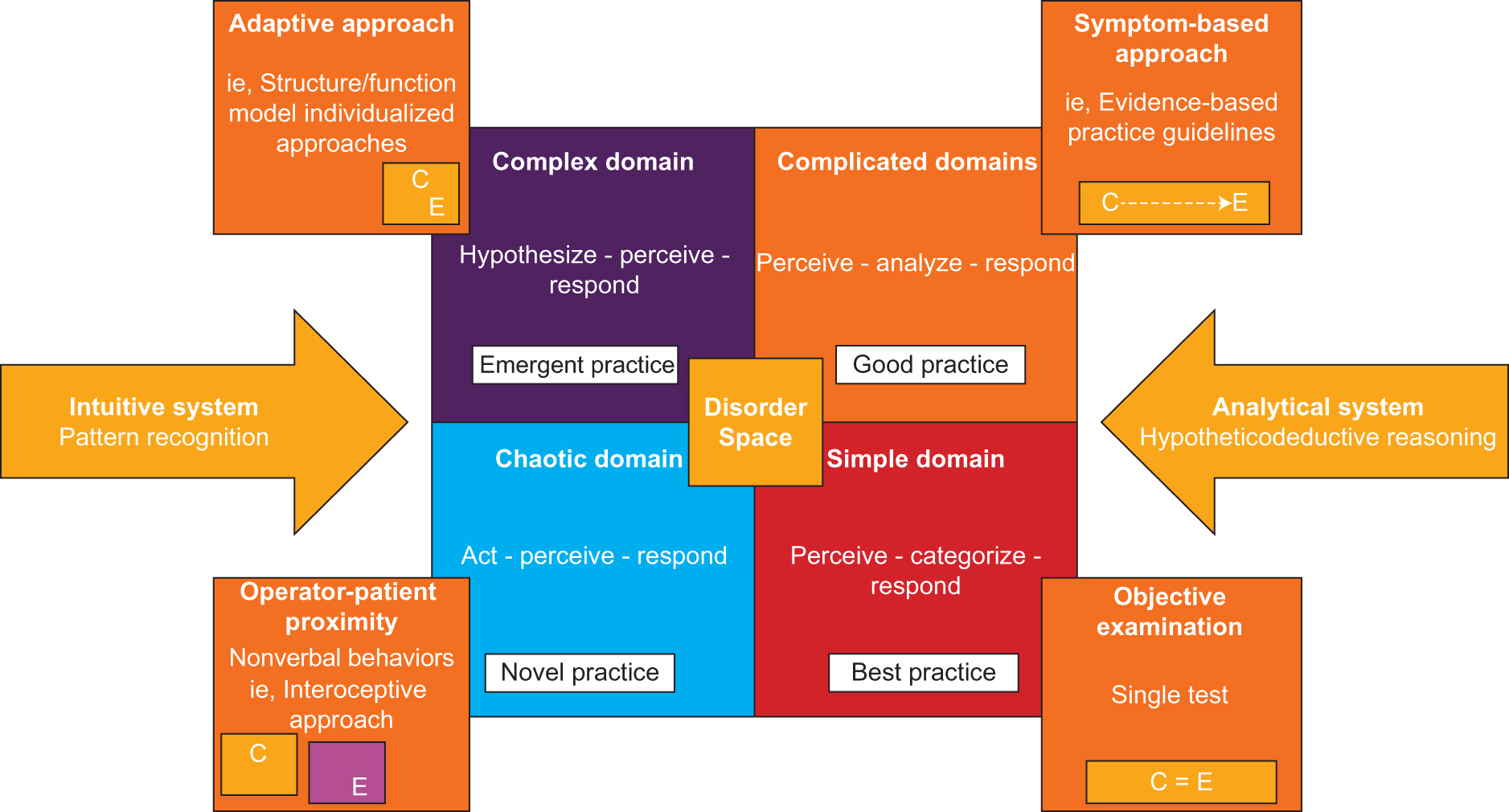

The Cynefin framework in the field of osteopathy (manipulative care provided by foreign-trained osteopaths). The application of the Cynefin framework domains is useful to better understand clinical reasoning and the decision-making process. Modified from: Lunghi C, Baroni F, Alò M. Ragionamento clinico osteopatico: trattamento salutogenico ed approcci progressivi individuali. EDRA, Milano 2017: 25. Abbreviations: C, cause; E, effect.

Cynefin Framework: Clinical Reasoning and Decision-Making Process

Beyond contextualizing the results of scientific evidence for the management of a particular disease, health approaches to a complex adaptive system should adapt procedures to the values and preferences of each person. Complexity and uncertainty are fundamental features in health care processes.33 Complexity science has more recently been used in health care to realize the implementation of interventions and to translate evidence into practice.30 Systems analysis tools need to be applied to understand complex problems and develop solutions.34 The Cynefin framework (CF) has emerged from research conducted in the theory of complex adaptive systems, cognitive sciences, anthropology, and narrative models, as well as in evolutionary psychology.35Figure 1 shows the relationship between the individual, experience, and context, which all enable new approaches to decision-making processes in complex environments,32 such as the relationship between patient and osteopath. In the field of osteopathy, especially in countries where osteopathy is proposed as an analytic hierarchy process,23 the CF could be useful to better understand the decision-making process (Table 1 and Figure 2).

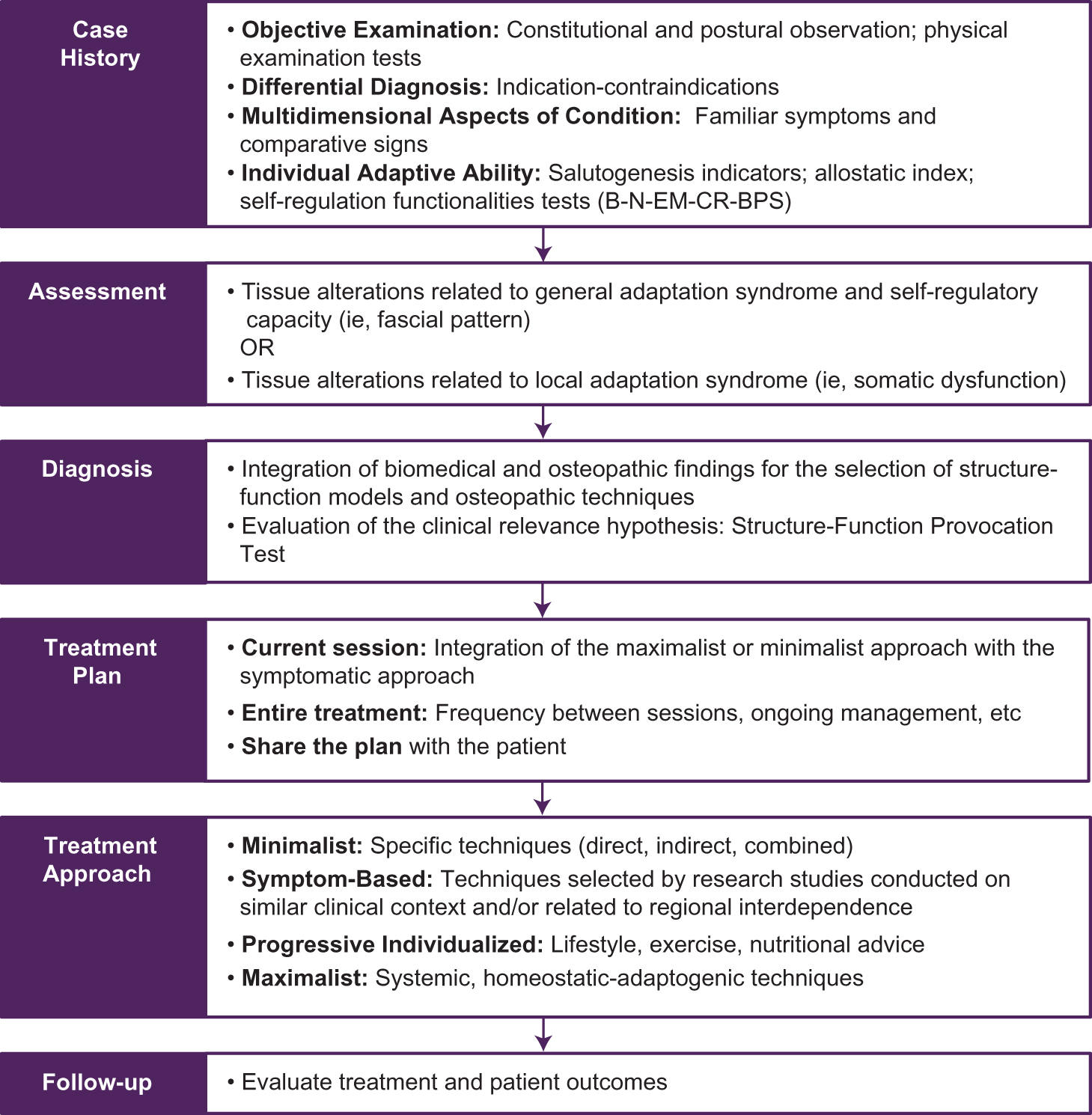

Decision-making process in osteopathy (manipulative care provided by foreign-trained osteopaths). Osteopathic decision-making is based on the integration of clinical history, objective examination of patient presentation, allostatic load index, and osteopathic palpatory findings (somatic dysfunction and/or fascial pattern). The decision-making process leads to an adaptive treatment with different manipulative approaches: one focused on SD related to local adaptation syndrome (minimalist approach), one focused on fascial pattern related to general adaptation syndrome and functional overload (maximalist approach), and one based on the outcomes of research studies on similar complaints (symptom-based approach). During the integration of the structure/function models, attention should be paid to the different types of touch and their different effects on patient's perception, tissue alterations, and self-regulation systems. Abbreviations: B, biomechanical; BPS, biopsychosocial; CR, circulatory respiratory; EM, energetic metabolic; N, neurological.

Application of Cynefin Framework's Domains in the Practice of Osteopathya

| Domain or Space | Description |

|---|---|

| Simple domain | During the objective examination, the DM follows anatomic-physiological rules and standard operating procedures and finds scientific evidence; an appropriate clinical test is selected to confirm or refute a diagnosis. |

| Complicated domain | Using a symptom-based approach, the osteopath relies on expert opinion and diverse stakeholder perspectives to identify a cause-effect relationship and select an appropriate treatment plan for a patient. This method is used when a patient has poor motivation and therefore complex adaptive care cannot be implemented.36 The patient's capacity for adaptive health work can be assessed with appropriate tools (eg, the Patient Activation Measure).37 |

| Complex domain | In this domain, psychosocial factors that influence adaptive capacity (learning mindset, autonomy orientation, self-regulatory strength, social networks) are particularly important in treatment planning.36 The osteopath should assess the patient's willingness to comply or accept adaptive care.37 The adaptive approach is based on the 5 structure/function models26: biomechanical, neurologic, circulatory/respiratory, metabolic, and biopsychosocial; osteopathic philosophy and practice are centered on the unit of body, mind, and spirit, which is consistent with a person-centered approach and the biopsychosocial model.36 Anamnestic and observational decoding of disorders, self-regulation systems overload related to the patients’ complaints and associated with the allostatic overload index, and palpatory findings lead an osteopath to evaluate a local or general overload of self-regulatory systems. This process leads the osteopath to select the models that evoke the same activation forces of the detected overload, focusing on dysfunctional structures or overload functions, as well as offering lifestyle recommendations, including nutritional and exercise advice and referrals to other professionals. Within the complex domain of health care, great improvements could be achieved not only by measuring the impact of osteopathy on patients’ experience of disease-related symptoms, but also from assessing improvements in the empowerment process.38,39 Furthermore, measuring the strength of SOC39 could help identify important factors involved in developing and maintaining health, even under difficult external circumstances.39 While pathogenesis is important to understand disease and disease development, salutogenesis contributes to the comprehension of the development and maintenance of health. A strong SOC can be progressively developed by individuals capable of drawing on general, sufficient, and adequate resilience resources.39 |

| Chaotic domain | In this domain, stabilization is needed for patterns to emerge. Osteopaths should use multimodal program aims (eg, cognitive behavioral approaches and exercise) to increase psychological flexibility and improve function,40 as well as osteopathic approaches based on operator-patient proximity and nonverbal behaviors, such as interoceptive touch.41 During these procedures, the osteopath maintains contact with the patient and is contextually engaged in a focused tactile attention task (eg, perceiving myofascial movements to balance the activity of the autonomic nervous system, the interoceptive threshold, and the cortical integration centers41 to elicit a response). Decoding health improvement findings within a multimodal program integrated with osteopathic interoceptive treatment could encourage the patient to engage in a process approach40 and allow an integration between the symptom-based and the adaptive approaches with the support of other health care professionals. |

| Disorder space | If it is impossible to recognize a domain, the osteopath should search for any confounding DM factors. To identify an action domain, the assessment procedure must be repeated. Of note, if the osteopath bases DM on predefined, linear knowledge rather than on single case assessment, he or she risks choosing a procedure just because it succeeded in the past, and previous positive outcomes will not necessarily recur. Thus, some patients require referral to specialists. |

a Manipulative care provided by foreign-trained osteopaths.

Abbreviations: DM, decision-making; SOC, sense of coherence.

The CF has 4 domains and a disorder space, as follows35:

■ Simple domain. Cause and effect are in linear relation; therefore, the operator can identify 1 or 2 good responses. This approach involves 3 actions required to apply best practice: perceive, categorize, and respond.

■ Complicated domain. Cause-effect relationship is not fully known to the experts and requires analysis or some other form of investigation or application of specialist knowledge; reference is made to systematic reviews and guidelines to find real-world hypotheses and discover a range of possible reactions. This approach involves 3 actions required to apply “good practice”: perceive, analyze, and respond.

■ Complex domain. The relationship between cause and effect can be perceived only retrospectively. It is therefore defined as an emerging relationship because events can be understood on the basis of stories, narration, relationships, and patterns of dysfunctional behavior. This approach involves 3 actions required to elicit “emergent practice”: hypothesize, perceive, and respond.

■ Chaotic domain. When the evaluation process does not show clinically relevant cause-effect relationships, the approach is to act, perceive, and respond to discover new practice (or “novel practice”).

■ Disorder space. At the center of the framework, the disorder space applies to situations in which selecting from any of the 4 previously named domains is impossible.

Knowledge in health care is a multidimensional dynamic construct that is personal, is discovered, has explicit and tacit dimensions, and can be concerned with content or context. Complex adaptive systems science views knowledge as both constructed and in constant flux. The CF model helps osteopaths in understanding knowledge as a personal construct achieved through sense making.52 Specific knowledge aspects temporarily reside in either 1 of 4 domains—simple, complicated, complex, or chaotic—but new knowledge can only be created by challenging the known and moving it through the other domains. Thus, health care is inherently uncertain, and osteopaths require a context-driven flexible approach to knowledge discovery and application in clinical practice, as well as in health service training and planning.52

Cognitive Processes in the CF

Pattern recognition and hypotheticodeductive reasoning are the foundations of the intuitive and the analytical systems, respectively.53 Osteopaths, like other health care professionals, mainly adopt both pattern recognition and hypotheticodeductive approaches as part of their diagnostic reasoning, which depends on the perceived level of complexity of the patient presentation.54,55 The recommendations on perceptual training described in several articles53,55,56 can be gradually applied by osteopaths who adopt domains of complexity to aid with decision-making. When the patient-osteopath relationship is located in the simple domain, an osteopath is anchored with routine and previously used patterns. Osteopaths seek confirmation with tried and tested ways of diagnosis and management. Liem53 reported that there is little room for experimentation and originality within the simple domain.

Osteopaths operating in the complicated domain must be open and inquisitive. In the complex domain, osteopaths move out of their limited frame of reference and attempt to see the world through the patient's eyes because being empathetic with patients may bring radical new insights.53 In the chaotic domain, osteopaths begin to perceive the fullness of information that emerges at each moment of perception and can draw from their reliable and trustworthy intuition to evolve and foster innovation at all levels.53

Improving the awareness and development of intuitive processes in practical decision-making of both osteopaths and osteopathic students should be introduced in teaching and learning processes. The introduction to these concepts will improve “reliance on intuition” or “problem-oriented” strategies and launch CF to develop clinical reasoning in osteopathic education.53,56

The CF is a useful tool for classifying a system's complexities and its environment. The framework does not tell us how to solve problems or give a solution. Instead, the CF points out in which domain the patient-osteopath relationship is located, and it gives no suggestions for shifting domains. The most interesting element in the CF is the differentiation between the complicated and the complex domains. The analytical approach adopted in the complicated domain does not work in all cases because the osteopath is required to stick to the analytical model. This is the typical guideline-focused approach aimed to manage an aspect of a disease on the basis of protocols derived from research studies and established treatment recommendations.54

On the contrary, the osteopath applying clinical reasoning in the complex domain has no model available to predetermine all aspects of the process. Treatment is directed to all components related to the patient's adaptive capacity (eg, fascial system alterations, somatic dysfunctions, behavioral habits) that emerge as clinically relevant for the patient's presentation and state of health. In the complex domain, both patient and osteopath can share a high-value experience, which can be investigated through the patient's narrative and understood by decoding a metaphorical language: not just what the patient says but what the patient does not say and what the patient's body language communicates. The complex domain calls for the recognition of system behavior patterns that may evoke adequate models of salutogenic interaction with the whole person. Consequently, it is up to the osteopath to understand the complexity of the person–environment–health system and use their skills to contextualize the available scientific literature in their clinical practice. In particular, osteopaths should refer to research studies that address the effects of OMTh and related manipulation sources on physical parameters and physiological functions involved in causes, maintenance, or aggravation of different disorders.

Clinical and diagnostic reasoning must be better understood and incorporated into osteopathic practice and education to ensure patient safety and optimal care.56 Osteopathic educational institutions should actively promote the basic understanding of the dual-process theory and facilitate this process. The institutions should also include case-based learning approaches during training and postgraduate mentorship programs to reinforce the acquisition of clinically relevant patterns (Table 2).56 Because decision-making habits of osteopaths remain relatively unexplored, it is necessary to design experimental and qualitative research to obtain a common framework and develop teaching programs and clinical practice.55 Therefore, as proven by other health-related practice research such as ergonomics,57 the CF could also be a powerful tool for advancing decision-making processes and establishing practiced based in complexity science in the field of osteopathy.32

Allostatic Overload Index Involved in the Decision-Making Process in the Practice of Osteopathya

| Identifiers | Examples |

|---|---|

| Markers | |

| Biomarkers | Neuroendocrine, metabolic, immunologic markers42,43 |

| Psychomarkers | Body perception questionnaire-short form44; depression, anxiety and stress scales45; salutogenesis index (sense of coherence questionnaires)39 |

| Life markers | Social Readjustment Rating Scale46 |

| Self-Regulation Systems Functional Tests | |

| Biomechanical | Postural control test47 |

| Neurologic | Manual assessments of central sensitization48 and autonomic nervous system tone49 |

| Respiratory-circulatory | Manual assessment of respiratory motion50 and examination of the amplitude of the peripheral pulses, considering its relationship with arterial stiffness49 |

| Metabolic | Gastrointestinal distress signs49 |

| Psychosocial | Waddell signs51 |

a Manipulative care provided by foreign-trained osteopaths.

New Complex Perspective in Osteopathic Research for Best Practices

The CF was originally developed as a tool for decision-making processes in management. Although occasionally applied to health care,34,52,57,58 the CF has not been implemented in medical research and practice, to our knowledge. The CF is no substitute for solid scientific solutions to the consequences of complexity, but it provides a common reference language and conceptual framework to discuss complexity and draw conclusions regarding insights, decisions, and actions.32

In a 2017 article, Kerry18 noted that “clinical practice should be based on best evidence, and an era of clinical freedom should not be returned to.” Kerry also claimed that “limitations of existing approaches to clinical research can be re-examined and reconceptualized.” Complexity principles can be endorsed to propose a new research vision in osteopathic and other professional practices. The core elements include a reexamination of what constitutes best evidence in the osteopathic clinical decision-making processes and health policy. Clinical reasoning and decision-making processes associated with clinical practice build on the foundation of evidence-based best practice to achieve evidence-informed competence.59 Using research to inform practice can increase accountability and transparency in decision-making processes, which will be helpful to better determine which interventions are likely to produce the desired outcomes and ensure that osteopaths’ decisions are informed by the best knowledge available.59

In line with a humanistic framework, patients should be at the core of future studies. Forthcoming research agendas should be focused on transdisciplinary studies that consider the humanities and involve stakeholders to expand research context and theories. The complexity of clinical practice exposes the empirical and philosophical limitations of current methods. Clinical practice provides a context in which additional sources of evidence can and should be scientifically examined. For instance, in 2018, the Italian Register of Osteopaths proposed a list of core competencies for osteopaths, focusing on specific activities, such as the promotion of health through OMTh based on adaptation.23 To provide a longitudinal index of the impact of osteopathic interventions on health promotion and maintenance, future research through prospective longitudinal studies must include measurement of the self-regulation systems activities, a sense of coherence,39 and examination of the allostatic load battery.42,43,60 It is time to create an ambitious research program to effectively establish a person-centered and evidence-informed framework for the practice of osteopathy.

Conclusion

Today, health care systems are promoting a more holistic approach to person-centered care by considering and empowering the whole patient.3,8 Like the foundational role of primary health care, osteopaths should support patients who are not motivated to care for themselves and teach them to recover trust by providing an appropriate process of care.61 Complexity thinking adds a real world, multidimensional appreciation of the system's density and dynamics, but it does not make it easier to effect change. Through interdisciplinary work, it should be possible to identify ways to create richer and more valid forms of evidence-informed knowledge.

Osteopaths should follow the osteopathic medicine model in the United States and closely monitor the practice of OMTh. However, if appropriately implemented, the mindlines model should enable osteopaths to provide expert guidance and to empower patients. The time has come to create a health system that considers the expectations and needs of the community through the social context of a personalized and evidence-informed practical approach.

Acknowledgments

The CF is a useful tool to renew the principles of osteopathy and contextualize it in contemporary health systems; thus, we are grateful to Stephen Tyreman, PhD, for introducing the concept of complexity science and CF in the field of osteopathy.

References

1. Acheson SD . Independent Inquiry Into Inequalities in Health Report.London, United Kingdom: The Stationary Office; 1998.Search in Google Scholar

2. Mokdad AH , MarksJS, StroupDF, GerberdingJL. Actual causes of death in theUnited States, 2000. JAMA.2004;291:1238-1245.10.1001/jama.291.10.1238Search in Google Scholar PubMed

3. World Health O rganization—Regional Office for Europe. Health 2020: A European Policy Framework Supporting Action Across Government and Society for Health and Well-being. Copenhagen, Denmark: World Health Organization; 2013.Search in Google Scholar

4. Roberti di Sarsina P , AliviaM, GuadagniP. Traditional, complementary and alternative medical systems and their contribution to personalisation, prediction and prevention in medicine—person-centred medicine. EPMA Journal. 2012;3:15. doi:10.1186/1878-5085-3-15Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

5. Turner P , HolroydE. A theoretical framework of holism in healthcare. Insights Biomed. 2017;2(1):1-4. doi:10.21767/2572-5610.100019Search in Google Scholar

6. Thygeson M , MorrisseyL, UlstadV. Adaptive leadership and the practice of medicine: a complexity-based approach to reframing the doctor-patient relationship. J Eval Clin Pract. 2010;16(5):1009-1015. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01533.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Thygeson MN . Implementing adaptive health practice: a complexity-based philosophy of health care. In: SturmbergJP, MartinCM, eds. Handbook of Systems and Complexity in Health.New York, NY: Springer; 2013:661-684.10.1007/978-1-4614-4998-0_38Search in Google Scholar

8. WHO Traditional Medicine Strategy: 2014-2023 . Hong Kong, China: World Health Organization; 2013.Search in Google Scholar

9. Fischer F , LewithG, WittCM, et al.A research roadmap for complementary and alternative medicine - what we need to know by 2020.Forsch Komplementmed.2014;21(2):e1-e16. doi:10.1159/000360744Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Slattengren AH , NisslyT, BlustinJ, BaderA, WestfallE. Best uses of osteopathic manipulation. J Fam Pract. 2017;66(12):743-747.Search in Google Scholar

11. Lanaro D , RuffiniN, ManzottiA, ListaG. Osteopathic manipulative treatment showed reduction of length of stay and costs in preterm infants: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(12):e6408. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000006408Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

12. Ponzo V , CinneraAM, MommoF, CaltagironeC, KochG, TramontanoM. Osteopathic manipulative therapy potentiates motor cortical plasticity. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2018;118(6):396-402. doi:10.7556/jaoa.2018.084Search in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Saracutu M , RanceJ, DaviesH, EdwardsDJ. The effects of osteopathic treatment on psychosocial factors in people with persistent pain: a systematic review.Int J Osteopath Med.2018;27:23-33.10.1016/j.ijosm.2017.10.005Search in Google Scholar

14. Cerritelli F , RuffiniN, LacorteE, VanacoreN. Osteopathic manipulative treatment in neurological diseases: systematic review of the literature. J Neurol Sci. 2016;369:333-341. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2016.08.062Search in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Cicchitti L , MartelliM, CerritelliF. Chronic inflammatory disease and osteopathy: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0121327. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0121327Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

16. Ruffini N , D’AlessandroG, CardinaliL, FrondaroliF, CerritelliF. Osteopathic manipulative treatment in gynecology and obstetrics: a systematic review. Complement Ther Med. 2016;26:72-78. doi:10.1016/j.ctim.2016.03.005Search in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Steel A , BlaichR, SundbergT, AdamsJ. The role of osteopathy in clinical care: broadening the evidence-base. Int J Osteopath Med. 2017;24:32-36. doi:10.1016.j.ijosm.2017.02.002Search in Google Scholar

18. Kerry R . Expanding our perspectives on research in musculoskeletal science and practice. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2017;32:114-119. doi:10.1016/j.msksp.2017.10.004Search in Google Scholar PubMed

19. Sandhouse M . Technical requirements to become an osteopathic physician. Int J Osteopath Med. 2014;17(1):43-47. doi:10.1016/j.ijosm.2013.04.005Search in Google Scholar

20. Sposato N , ShawR, BjersåK. Addressing the ongoing friction between anecdotal and evidence-based teachings in osteopathic education in Europe. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2018;22(3):553-555. doi:10.1016/j.jbmt.2018.05.006Search in Google Scholar PubMed

21. European Committee for Standardization. CEN website. https://standards.cen.eu/. Accessed March 15, 2018. Search in Google Scholar

22. Mein EA , GreenmanPE, McMillinDL, RichardsDG, NelsonCD. Manual medicine diversity: research pitfalls and the emerging medical paradigm. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2001;101(8):441-444.Search in Google Scholar

23. Sciomachen P , ArientiC, BergnaA, et al. Core competencies in osteopathy: Italian register of osteopaths proposal. Int J Osteopath Med. 2018;27:1-5. doi:10.1016/j.ijosm.2018.02.001Search in Google Scholar

24. Thomson OP , PettyNJ, MooreAP. Reconsidering the patient-centeredness of osteopathy. Int J Osteopath. 2013;16(1):25-32. doi:10.1016/j.ijosm.2012.03.001Search in Google Scholar

25. Grace S , OrrockP, VaughanB, BlaichR, CouttsR. Understanding clinical reasoning in osteopathy: a qualitative research approach. Chiropr Man Therap. 2016;24:6. doi:10.1186/s12998-016-0087-xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

26. Lunghi C , TozziP, FuscoG.The biomechanical model in manual therapy: is there an ongoing crisis or just the need to revise the underlying concept and application?J Bodyw Mov Ther.2016;20(4):784-799. doi:10.1016/j.jbmt.2016.01.004Search in Google Scholar PubMed

27. Wainapel SF , RandS, FishmanLM, Halstead-KennyJ. Integrating complementary/alternative medicine into primary care: evaluating the evidence and appropriate implementation. Int J Gen Med. 2015;8:361-372. doi:10.2147/IJGM.S66290Search in Google Scholar

28. Eccles MP , MittmanBS. Welcome to implementation science. Implementation Sci. 2006;1:1. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-1-1Search in Google Scholar

29. Complexity science in brief. University of Victoria website. https://www.uvic.ca/research/groups/cphfri/assets/docs/Complexity_Science_in_Brief.pdf. Accessed April 1, 2019. Search in Google Scholar

30. Braithwaite J , ChurrucaK, LongJC, EllisLA, HerkesJ. When complexity science meets implementation science: a theoretical and empirical analysis of systems change. BMC Med. 2018;16(1):63. doi:10.1186/s12916-018-1057-zSearch in Google Scholar

31. Gabbay J , le MayA. Evidence based guidelines or collectively constructed "mindlines?" ethnographic study of knowledge management in primary care.BMJ.2004;329(7473):1013. doi:10.1136/bmj. 329.7473.1013Search in Google Scholar

32. Kempermann G. Cynefin as reference famework to facilitate insight and decision-making in complex contexts of biomedical research. Front Neurosci. 2017;11:634. doi:10.3389/fnins.2017.00634Search in Google Scholar

33. Sturmberg JP . Complexity and primary care. In: World Organization of Family Doctors - Europe (WONCA Europe).World Book of Family Medicine – European Edition 2015. Istanbul, Turkey: Stichting WONCA Europe; 2015:33-36.Search in Google Scholar

34. Sturmberg JP , MartinCM, eds. Complexity in health: an introduction. In: Handbook of Systems and Complexity in Health.New York, NY: Springer; 2013:1-17.10.1007/978-1-4614-4998-0_1Search in Google Scholar

35. Van Beurden EK , KiaAM, ZaskA, DietrichU, RoseL. Making sense in a complex landscape: how the Cynefin framework from complex adaptive systems theory can inform health promotion practice. Health Promot Int. 2013;28(1):73-83. doi:10.1093/heapro/dar089Search in Google Scholar

36. Ellico T , SeffingerMA. Biopsychosocial effects of osteopathic interventions in patients with chronic pain. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2018;118(5):345-346. doi:10.7556/jaoa.2018.067Search in Google Scholar

37. Hibbard JH , MahoneyER, StockardJ, TuslerM.Development and testing of a short form of the patient activation measure.Health Serv Res.2005;40(6 pt 1):1918-1930. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00438.xSearch in Google Scholar

38. Antonovsky A. The sense of coherence: development of a research instrument. Newslett Res Rep Schwartz Res Center Behav Med. 1983;1:11-22.Search in Google Scholar

39. Antonovsky A . The structure and properties of the sense of coherence scale. Soc Sci Med. 1993;36(6):725-733. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(93)90033-Z.1093/heapro/dar089Search in Google Scholar

40. Lederman E . A process approach in osteopathy: beyond the structural model. Int J Osteopath Med. 2017;23:22-35. doi:10.1016/j.ijosm.2016.03.004Search in Google Scholar

41. Cerritelli F , ChiacchiarettaP, GambiF, FerrettiA. Effect of continuous touch on brain functional connectivity is modified by the operator's tactile attention. Front Hum Neurosci. 2017;11:368. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2017.00368Search in Google Scholar

42. Fava GA , GuidiJ, SempriniF, TombaE, SoninoN. Clinical assessment of allostatic load and clinimetric criteria. Psychother Psychosom. 2010;79(5):280-284. doi:10.1159/000318294Search in Google Scholar

43. McEwen BS . Biomarkers for assessing population and individual health and disease related to stress and adaptation.Metabolism.2015;64(3 suppl 1):S2-S10. doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2014.10.029Search in Google Scholar

44. Cabrera A , KolaczJ, PailhezG, Bulbena-CabreA, BulbenaA, PorgesSW. Assessing body awareness and autonomic reactivity: Factor structure and psychometric properties of the Body Perception Questionnaire-Short Form (BPQ-SF). Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2018;27(2):e1596. doi:10.1002/mpr.1596Search in Google Scholar

45. Keller A , LitzelmanK, WiskLE, et al. Does the perception that stress affects health matter? The association with health and mortality. Health Psychol. 2012;31(5):677-84. doi:10.1037/a002674355.Search in Google Scholar

46. Holmes TH , RaheRH.The Social Readjustment Rating Scale.Psychosom Res.1967;11(2):213-218. doi:10.1016/0022-3999(67)90010-4Search in Google Scholar

47. Bohannon RW , LarkinPA, CookAC, GearJ, SingerJ. Decrease in time balance test scores with aging. Phys Ther. 1984;64(7):1067-1070.10.1093/ptj/64.7.1067Search in Google Scholar PubMed

48. Nijs J , Van HoudenhoveB, OostendorpRA. Recognition of central sensitization in patients with musculoskeletal pain: application of pain neurophysiology in manual therapy practice. Man Ther. 2010;15(2):135-141. doi:10.1016/j.math.2009.12.001Search in Google Scholar PubMed

49. Cheshire WP Jr. , GoldsteinDS. The physical examination as a window into autonomic disorders. Clin Auton Res.2018;28(1):23-33. doi:10.1007/s10286-017-0494-7Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

50. Courtney R , van DixhoornJ, CohenM. Evaluation of breathing pattern: comparison of a Manual Assessment of Respiratory Motion (MARM) and respiratory induction plethysmography. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback.2008;33(2):91-100. doi:10.1007/s10484-008-9052-3Search in Google Scholar PubMed

51. Centeno CJ , ElkinsWL, FreemanM.Waddell's signs revisited?Spine. 2004;29(13):1392. doi:10.1097/01.BRS.0000128771.48789.FBSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

52. Sturmberg JP , MartinCM. Knowing—in medicine.J Eval Clin Pract.2008.14(5):767-770. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2753.2008.01011.x10.1111/j.1365-2753.2008.01011.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

53. Liem T . Intuitive judgement in the context of osteopathic clinical reasoning. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2017;117(9):586-594. doi:10.7556/jaoa.2017.113Search in Google Scholar PubMed

54. Task Force on the Low Back Pain Clinical Practice Guidelines. American Osteopathic Association Guidelines for Osteopathic Manipulative Treatment (OMT) for Patients With Low Back Pain. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2016;116(8):536-549. doi:10.7556/jaoa.2016.107Search in Google Scholar PubMed

55. Noyer AL , EstevesJE, ThomsonOP. Influence of perceived difficulty of cases on student osteopaths’ diagnostic reasoning: a cross sectional study. Chiropr Man Therap. 2017;25:32. doi:10.1186/s12998-017-0161-zSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

56. Spadaccini J , EstevesJE. Intuition, analysis and reflection: an experimental study into the decision-making processes and thinking dispositions of osteopathy students. Int J Osteopath Med. 2014;17(4):263-271. doi:10.1016/j.ijosm.2014.04.004Search in Google Scholar

57. Elford W. A multi-ontology view of ergonomics: applying the Cynefin Framework to improve theory and practice. Work. 2012;41(suppl 1):812-7. doi:10.3233/WOR-2012-0246-812Search in Google Scholar PubMed

58. Mark AL . Notes from a small island: researching organisational behaviour in healthcare from a UK perspective. J Organ Behav. 2006;27(7):851-867.10.1002/job.414Search in Google Scholar

59. Epstein I . Promoting harmony where there is commonly conflict: evidence-informed practice as an integrative strategy. Soc Work Health Care. 2009;48(3):216-231. doi:10.1080/00981380802589845Search in Google Scholar PubMed

60. Karlamangla AS , SingerBH, SeemanTE. Reduction in allostatic load in older adults is associated with lower all-cause mortality risk: MacArthur studies of successful aging. Psychosom Med. 2006;68(3):500-507. doi:10.1097/01.psy.0000221270.93985.82Search in Google Scholar PubMed

61. Tyreman S. Trust and truth: uncertainty in health care practice. J Eval Clin Pract. 2015; 21(3):470-8. doi:10.1111/jep.12332.1093/heapro/dar089Search in Google Scholar

© 2019 American Osteopathic Association

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- LETTERS TO THE EDITOR

- Doming the Diaphragm in a Patient With Multiple Sclerosis

- SURF

- Can Osteopathic Medical Students Accurately Measure Abdominal Aortic Dimensions Using Handheld Ultrasonography Devices in the Primary Care Setting?

- EDITORIAL

- The Art and Science of Osteopathic Medicine

- LETTERS TO THE EDITOR

- Renal Calculi Passage While Riding a Roller Coaster Has Ayurvedic Roots

- CORRECTION

- Correction

- AOA COMMUNICATION

- Official Call: 2019 Annual Business Meeting of the American Osteopathic Association

- Proposed Amendments to the AOA Constitution and Bylaws

- ORIGINAL CONTRIBUTION

- Gender Differences in Sexual Health Knowledge Among Emerging Adults in Acute-Care Settings

- Osteopathic Manipulative Medicine Consultations for Hospitalized Patients

- BRIEF REPORT

- Effects of Cannabis Use on Sedation Requirements for Endoscopic Procedures

- REVIEW

- Cynefin Framework for Evidence-Informed Clinical Reasoning and Decision-Making

- ART AND SCIENCE OF OSTEOPATHIC MEDICINE

- Why Does Clostridium difficile Infection Recur?

- CASE REPORT

- Complicated Withdrawal Phenomena During Benzodiazepine Cessation in Older Adults

- CLINICAL IMAGES

- Fetal Nuchal Cord

Articles in the same Issue

- LETTERS TO THE EDITOR

- Doming the Diaphragm in a Patient With Multiple Sclerosis

- SURF

- Can Osteopathic Medical Students Accurately Measure Abdominal Aortic Dimensions Using Handheld Ultrasonography Devices in the Primary Care Setting?

- EDITORIAL

- The Art and Science of Osteopathic Medicine

- LETTERS TO THE EDITOR

- Renal Calculi Passage While Riding a Roller Coaster Has Ayurvedic Roots

- CORRECTION

- Correction

- AOA COMMUNICATION

- Official Call: 2019 Annual Business Meeting of the American Osteopathic Association

- Proposed Amendments to the AOA Constitution and Bylaws

- ORIGINAL CONTRIBUTION

- Gender Differences in Sexual Health Knowledge Among Emerging Adults in Acute-Care Settings

- Osteopathic Manipulative Medicine Consultations for Hospitalized Patients

- BRIEF REPORT

- Effects of Cannabis Use on Sedation Requirements for Endoscopic Procedures

- REVIEW

- Cynefin Framework for Evidence-Informed Clinical Reasoning and Decision-Making

- ART AND SCIENCE OF OSTEOPATHIC MEDICINE

- Why Does Clostridium difficile Infection Recur?

- CASE REPORT

- Complicated Withdrawal Phenomena During Benzodiazepine Cessation in Older Adults

- CLINICAL IMAGES

- Fetal Nuchal Cord