Perplexing Rash: Challenges to Diagnosis and Management of Mycosis Fungoides

-

Jonathan A. Aun

Abstract

Mycosis fungoides is the most ubiquitous form of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Diagnosis is arduous, as early phases often resemble common inflammatory dermatoses. The principal histologic features of MF include medium to large-sized cerebriform mononuclear cells in single or small clusters in the epidermis. Treatment modalities are prodigious and relapses are common. The authors present a case of a 69-year-old man with mycosis fungoides, followed by a review of diagnostic modalities and phototherapeutic interventions for patients with this condition. According to literature reports, monochromatic excimer light therapy is the most advantageous and well-tolerated phototherapy modality for patients with early patch stage mycosis fungoides.

Mycosis fungoides (MF) is the most common form of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, with an estimated 1500 annual cases in the United States as of 2014.1 The incidence from 1973 to 2002 was 6.4 cases per million, and, in 2011, the overall incidence rate was approximately 4 cases per million.1 Mycosis fungoides is a helper T-cell lymphoma of the skin that most commonly occurs in patients aged between 40 and 60 years.1 The pathogenesis remains unclear, with no known associated risk factors and no known geographic predisposition or evidence for maternal transmission of the disease.1 There are 4 stages of MF: (I) early stage, (II) patch stage, (III) plaque stage, and (IV) tumor stage.2 The beginning of patch stage MF (ie, early patch stage) presents as superficial, noninfiltrated scaly lesions that can appear in any location but have a predilection for sun-protected areas, including the buttocks, lower abdomen, groin, inner surface of extremities, and breasts. Early diagnosis is challenging because early phases of the disease often resemble common inflammatory dermatoses, such as eczema or psoriasis, which can lead to misdiagnosis and delayed therapeutic intervention.2 On hematologic dissemination, a diffuse erythema and erythroderma, known as Sézary syndrome, can develop over the entire body.1 This leukemic transformation of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma may form de novo or can evolve from the classic patch or plaque stages of MF. Hence, early detection is vital for management and may reduce or prevent progression.3 This report describes a case of MF and provides a review of various diagnostic modalities for MF.

Report of Case

A 69-year-old white man presented to an urgent care center in 2009 with nonpruritic erythematous patches in a band-like distribution within the suprapubic region in a “swimsuit pattern” (Figure 1). He had a history of diverticulosis, colon polyps, osteoarthritis, and diet-controlled type 2 diabetes mellitus. He denied any current medications or known medication allergies. From 2010 to 2011, various physicians at urgent care centers and family medicine clinics evaluated the patient and diagnosed his condition as allergic contact dermatitis attributable to metals from his pants or belt. For the next 3 years, the patient implemented several unsuccessful measures to avoid metallic contact, including tucking his shirt and the avoidance of nickel buckles. The erythema progressed, however, and eventually lesions with scaling developed.

Nonpruritic erythematous patches (A and B) in a bandlike distribution within the suprapubic region in a swimsuit pattern (C) in a patient with mycosis fungoides.

In January 2014, the patient presented to a family medicine clinic where topical steroids were prescribed. They provided transient improvement over the following 2 months but did not completely resolve the rash. In March 2014, the patient was referred to a dermatologist for a punch biopsy of a representative lesion in the right side of his waist. Histopathologic evaluation revealed spongiotic dermatitis, including focal parakeratosis, chronic inflammatory infiltrate, and dermal eosinophils. Topical steroids were prescribed but did not resolve the rash.

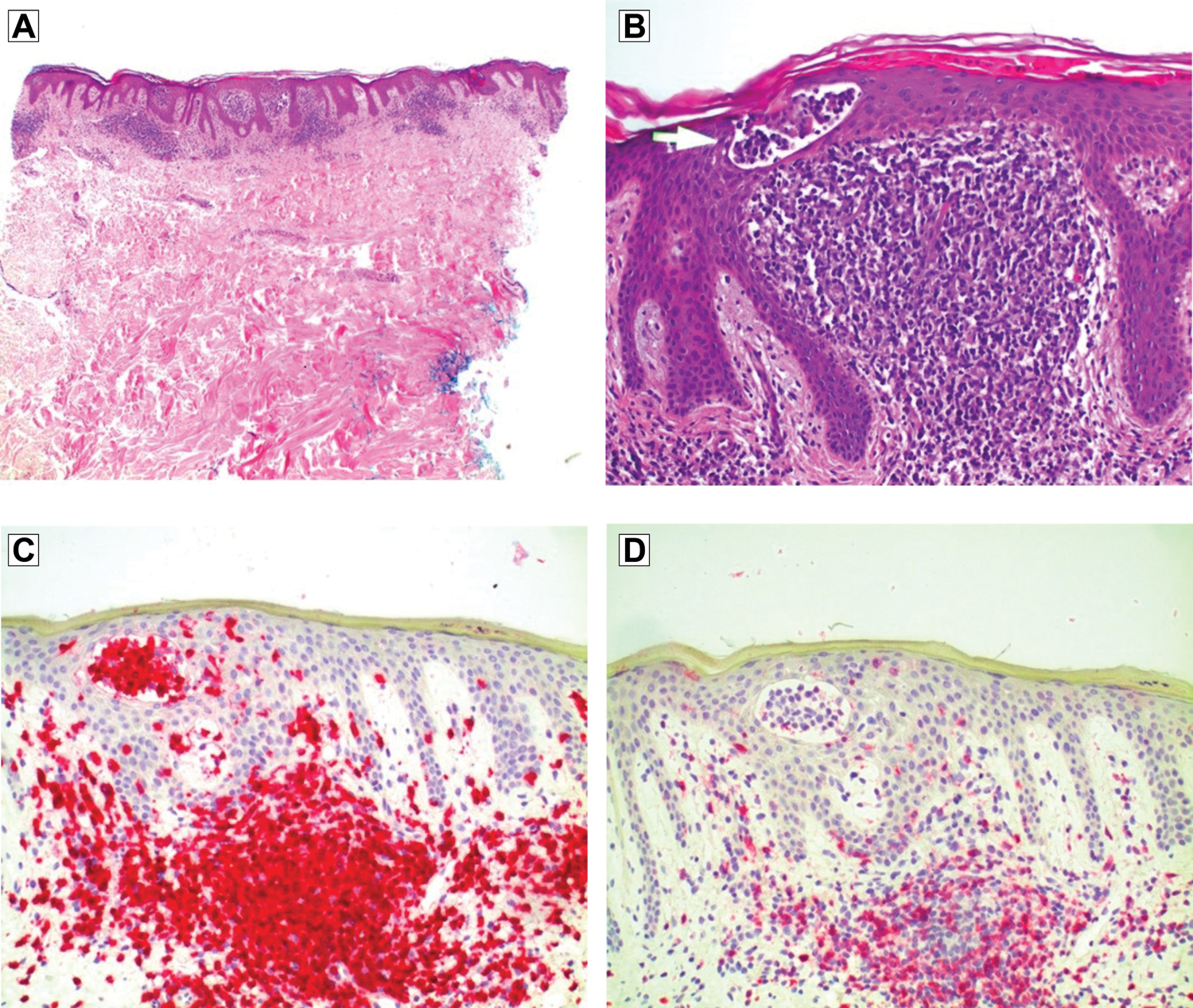

In May 2014, the patient returned to his dermatologist for skin patch testing, and the results indicated blue dye sensitivity. He received 2 courses of corticosteroids, which provided transient resolution with subsequent recurrences. The patient avoided wearing blue jeans, with no clinical improvement. In June 2014, the response to higher doses of corticosteroids was variable. About 1 month later, the patient returned to his dermatologist for a repeated punch biopsy of a lesion on the right side of his waist. The biopsy specimen revealed lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate and atypical lymphocytes with epidermotropism and predominantly CD3-positive cells and loss of CD7 staining (Figure 2), indicative of patch stage MF. T-cell receptor gene rearrangement by polymerase chain reaction confirmed clonal rearrangement of the T-cell receptor gamma locus gene. In August 2014, the patient reported that many new lesions developed in the axillary, inguinal, and popliteal areas. These scaly lesions involved less than 10% of his body surface area. With a suspicion of Sézary syndrome, the patient was referred to an oncologist for flow cytometry. On completion of staging studies, early patch stage MF was confirmed.

Biopsy specimen of the right side of the waist in a patient with a persistent rash revealed (A) lymphocytic infiltrate with epidermotrophism and a lack of significant spongiosis (hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification ×40), (B) atypical lymphoid infiltrate with Pautrier microabscess formation (hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification ×200), (C) lymphocytes staining diffusely with CD3 (hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification ×200), and (D) loss of CD7 staining (immunohistochemical, original magnification ×200).

In January 2015, the patient returned to his dermatologist and was treated with topical nitrogen mustard gel, which caused a significant amount of local irritation and was stopped after 1 month. He was subsequently referred to a different dermatologist for advanced management of his condition. Narrowband UV-B treatment was considered, but, because of extensive groin involvement and atypical nevi, phototherapy was decided against. In February 2015, methotrexate was initiated with folic acid supplementation and continuation of topical steroids. Mole mapping was recommended for the atypical nevi. The methotrexate and topical steroids failed to improve the patient's symptoms and, in April 2015, he underwent monochromatic excimer light (MEL) phototherapy and achieved partial remission.

Discussion

We conducted a literature review using Pubmed, Worldcat.org, VCOM Library, and UpToDate. Search terms included “early mycosis fungoides,” “mycosis fungoides patch,” “mycosis fungoides diagnosis,” “phototherapy,” and “treatments.”

Achieving Accurate Diagnosis

Some patients will exhibit only 1 MF stage and some may have all 4 simultaneously.2 Mycosis fungoides can be difficult to diagnose because it is easily confused with eczema.4 In 2005, a 4-point diagnostic scoring algorithm for the diagnosis of early MF was proposed (Table).5 This algorithm includes clinical, histopathologic, molecular biologic, and immunopathologic criteria that should be considered in the diagnosis of early MF.

Algorithm for Diagnosis of Early Mycosis Fungoidesa

| Criteria | Description | Scoring |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical | ||

| Basic | Persistent or progressive patches or thin plaques | 2 points for basic criteria and 2 additional criteria met 1 point for basic criteria and 1 additional criterion met |

| Additional | 1. Non-sun exposed location 2. Size/shape variation 3. Poikiloderma |

|

| Histopathologic | ||

| Basic | Superficial lymphoid infiltrate | 2 points for basic criteria and 2 additional criteria met 1 point for basic criteria and one additional criterion met |

| Additional | 1. Epidermotropism without spongiosis 2. Lymphoid atypiab |

|

| Molecular biologic (T-cell receptor gene rearrangement analysis) | T-cell clonal pattern must be detected by PCR-based analysis of T-cell receptor gene rearrangementsc | 1 point for clonality |

| Immonopathologicd | 1. <50% CD2+, CD3+, or CD5+ T cells 2. <10% CD7+ T cells 3. Epidermal/dermal discordance of CD2, CD3, CD5, or CD7e |

1 point for 1 or more criteria met |

a A total of 4 points are required for the diagnosis of mycosis fungoides based on any combination of points from the clinical, histopathologic, molecular biologic, and immunopathologic criteria.

b Lymphoid atypia is defined as cells with enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei and irregular or cerebriform nuclear contours.

c Contact laboratory to determine specimen required (eg, fresh-frozen tissue, formalin-fixed paraffin block).

d Contact laboratory to determine specimen required (eg, 5-mm punch biopsy submitted in tissue culture medium not frozen or fixed).

e T-cell antigen deficiency confined to the epidermis.

Abbreviation: PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

Source: Reprinted with permission from the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, Vol 53, Pimpinelli N, Olsen EA, Santucci M, et al, Defining early mycosis fungoides, 1053-1063, 2005, with permission from Elsevier.

Early MF can be diagnosed based on clinical criteria after evaluating the patient's history, morphologic characteristics, and number and distribution of lesions. Lesions are generally unresponsive to topical corticosteroids and antibiotics.6 Alternative conditions to consider when lesions are unresponsive to topical corticosteroids or antibiotics include nummular eczema, psoriasis, lichen planus, pityriasis rosea, and small plaque parapsoriasis.7 Most patients with MF present with multiple lesions; unilesional cases of MF can occur, but they are rare.8 The traditional distribution area of lesions, commonly referred to as the bathing suit pattern, was found in the current patient. This pattern includes areas below the waistline, flanks, breasts, inner thighs, inner arms, and periaxillary areas.2 Early MF lesions can include macular patches or more indurated, infiltrated plaques. The lesions can be pink, erythematous, or violaceous, with a smooth or scaly surface, resembling chronic eczema.9

Diagnosis of MF can also be made based on histopathologic criteria. Skin biopsy, specifically excisional fusiform biopsy, along the longitudinal length of the affected area is the traditional approach to perform a gross and histopathologic analysis.2 However, results of these biopsies must be compared to determine any pathologic differences.10 The most important feature to recognize is medium to large cerebriform mononuclear cells, either singly or in small clusters in the epidermis, for which the sensitivity and specificity are 100% and 92.3%, respectively.11 These cerebriform mononuclear cells are referred to as Pautrier microabscesses.

These clinicopathologic criteria are generally more useful in diagnosing the patch stage of MF; however, early MF typically displays a nonspecific pattern of lesions, and, thus, molecular analysis is often necessary for diagnosis.4 Mycosis fungoides is a disorder of mature CD4+ helper T-cells or, less commonly, of CD8+ cytotoxic T-cells. An uncommonly performed test that may aid in diagnosis is nonradioactive polymerase chain reaction–single strand conformational polymorphism.12 Research within the molecular biology field is promising, and this test may be recommended for patients in whom traditional excisional biopsy has failed to aid in diagnosis.2 T-cell receptor gene rearrangement can be a sign of MF (Table). The patient in the current case demonstrated this polymerase chain reaction gene rearrangement. Polymerase chain reaction may be used to identify the presence or absence of malignant clone T cells systemically after a patient begins treatment.6

Additionally, immunopathologic criteria should be considered for the diagnosis of MF. Based on the algorithm for diagnosis (Table),5 3 immunopathologic criteria, if present, could be signs of early MF. The most specific immunochemical criteria is CD7 deficiency, as this marker is 40% sensitive and 80% specific for early MF.5 Lymphocytes staining diffusely with CD3 were found in our patient (Figure 2C).

Phototherapy Treatment Options

There are various treatment options for patients with MF, depending on the extent of skin involvement, with varying methods for measuring remission and complete response rates.13 Because MF is an immunosuppressive and immunologically responsive disease, initial therapies for many patients involve cutaneous and biological approaches to treatment that directly target cytotoxic cells and have indirect effects on disease control.1 Early MF is typically confined to the skin and has an excellent prognosis, with long-term therapies directed only at the skin.1

Phototherapy is an effective treatment option for patients with MF because lymphocytes are very sensitive to light in the form of UV-A, psoralen—UV-A (PUVA), broadband UV-B, and narrowband UV-B. In a retrospective study14 of 56 patients with patch stage MF, 21 patients were treated with narrowband UV-B, and 35 patients were treated with PUVA. Narrowband UV-B resulted in complete remission in 81% of patients, and PUVA resulted in complete remission in 71% of patients.14 Another study15 that examined UV-B treatment in 14 patients with MF showed that the treatment resulted in complete response in 78% of patients. Risks associated with PUVA include cutaneous epithelial neoplasms and cataract formation.16 Narrowband UV-B is the most commonly used form of phototherapy because of the low risk of secondary skin neoplasms.1 Alternatively, electron beam radiation therapy may be used for solitary and localized lesions, as it is a reliable and rapid method of inducing a remission of these types of lesions. Moreover, narrowband UV-B is widely available and can be used on most lesions no matter the location.16

Total skin electron beam therapy (TSEBT) may also be used to treat patients with MF. This therapy is well tolerated and advantageous because its superficial penetration (≤10 mm) spares the mucous membranes, bone marrow, gastrointestinal tract, and other vital internal organs.16-18 Technical factors, such as completeness of the skin treatment, surface dose, and energy or penetration of the electrons, affect clinical outcomes. Higher-intensity TSEBT is associated with a greater rate of complete remission and less disease progression. Overall response rates approach 100%, and complete responses range from 40% to 98%, depending on the extent of skin involvement.17,18 Clinical complete response rates for patients with patch or plaque stage MF range from 71% to 98%.1 For patients with cutaneous recurrences after TSEBT who are not amenable to other skin-directed treatments, a second course of TSEBT can be worthwhile.1 A disadvantage of TSEBT is that the palms, soles, scalp, axillae, and perineum may need separate exposures to ensure total body treatment.16 Moreover, skin folds inhibit effective electron beam coverage. In the case of eyelid involvement, lead eye shields are used for protection of the lens and cornea, and special contact lenses may be worn for additional protection.16 If hands are involved, nail shields may be applied for prevention of anonychia.16 Potential adverse effects of TSEBT include alopecia, atrophy of sweat glands and skin, radiodermatitis, and edema. These adverse effects can be reduced through the use of highly fractionated doses.16

The use of excimer laser and MEL therapies in patients with MF have also been examined. The primary advantage of excimer laser therapy is that it can be specifically directed at the location of the lesion. Patients usually undergo 2 to 3 weekly sessions, with a total of 12 to 46 sessions,19 which allows areas without lesions to avoid accumulating UV light, thereby reducing the risk of carcinogenesis. Another advantage of excimer laser therapy is the application of higher fluencies to the affected skin, as well as application to hidden areas, such as folds and curves, which conventional phototherapy treatment typically does not reach.19 The rate of complete response is 50% to 80%, with response durations varying from 7 months to 30 months at follow-up.19 The treatment is well tolerated but may cause hyperpigmentation of the lesions, as well as erythema, edema, crusting, and blisters. The primary disadvantage of excimer laser therapy is that it is expensive and, therefore, inaccessible for use in daily clinical practice.19 Moreover, this therapy requires extensive training and management by a dermatologist.

In patients with MF, MEL has been shown to have positive results. In 3 studies19-21 that examined the use of MEL in patients with MF, the results of 1 weekly session over 4 to 11 weeks were analyzed. Fewer total treatment sessions of MEL are required (4-11) with a lower cumulative dose compared with excimer laser therapy. In a study19 that examined the effects of MEL on patients with MF, the complete response rate was 100% of lesions, with remission periods of 12 to 28 months. The only reported adverse effect was transient hyperpigmentation. In another study20 that examined 4 patients with early patch stage MF, 7 patch lesions achieved clinical and histologic remission, and all lesions remained in stable complete remission after 28 months, with no reported adverse effects. Additionally, in a prospective study21 involving 9 patients with MF who underwent MEL in which clinical response was assessed with photographs and biopsies and patients were monitored for 12 months, complete remission in all patients was achieved.21 Monochromatic excimer light therapy is an expensive treatment option for patients but less costly than excimer laser therapy.19 The results reported in previous studies have been encouraging, but the cost and small number of centers that provide MEL are limitations.22 Although extensive training is required to perform MEL, it is less complicated than excimer laser therapy.19

Conclusion

Based on the literature, clinical and histopathologic criteria can be helpful in the diagnosis of early MF. Given the powerful prognostic implications of body surface involvement and the progression from patch to plaque to nodular forms, early diagnosis of MF is warranted. In cases of MF, it is recommended to perform an excisional fusiform biopsy along the longitudinal length of the affected area and to recognize that subsequent biopsies increase diagnostic yield. A high index of suspicion by the physician and persistence of patient involvement, such as scheduling and attending frequent follow-up appointments, are key contributing factors to achieving a successful diagnosis. Our literature review found that phototherapy treatments, including MEL, excimer laser therapy, and TSEBT, are efficacious for patients with MF. Among these 3 phototherapies, MEL therapy may be the most advantageous and well-tolerated option. It also carries the added benefit of penetrating difficult areas, such as skin folds. Despite these benefits, therapy should always be tailored to the individual patient. Although more trials are necessary, we conclude that phototherapy can be valuable in the management of MF.

References

1. Foss F , GibsonJ, EdelsonR, WilsonL. Cutaneous lymphomas. In: DeVitaV, LawrenceT, RosenbergS, eds. Cancer Principles and Practice of Oncology. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2014:1584-1596.Search in Google Scholar

2. Habif T , CampbellJ, ChapmanMS, DinulosJ, ZugK. Skin Disease: Diagnosis and Treatment. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2011:493-495.Search in Google Scholar

3. Lazar A , MurphyG. The skin. In: KumarV, AbbasA, AsterJ, eds. Robbins & Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2014:1159-1160.Search in Google Scholar

4. Habif T . Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2016:837-849.Search in Google Scholar

5. Pimpinelli N , OlsenE, SantucciM, et al. Defining early mycosis fungoides. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53(6):1053-1063. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.08.057Search in Google Scholar

6. Cho-Vega JH , TschenJA, DuvicM, VegaF. Early-stage mycosis fungoides variants: case-based review. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2010;14(5):369-385. doi:10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2010.06.003Search in Google Scholar

7. Ackerman AB , BoerA, BenninB, GottliebGJ. Histologic Diagnosis of Inflammatory Skin Disease: An Algorithmic Method Based on Pattern Analysis. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1997.Search in Google Scholar

8. Oliver GF , WinkelmannRK. Unilesional mycosis fungoides: a distinct entity. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20(1):63-70.10.1016/S0190-9622(89)70008-6Search in Google Scholar

9. Abel EA , WoodGS, HoppeRT. Mycosis fungoides: clinical and histologic features, staging, evaluation, and approach to treatment. CA Cancer J Clin. 1993;43(2):93-115.10.3322/canjclin.43.2.93Search in Google Scholar

10. Naraghi ZS , SeirafiH, ValikhaniM, FarnaghiF, KavusiS, DowlatiY. Assessment of histologic criteria in the diagnosis of mycosis fungoides. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42(1):45-52. doi:10.1046/j.1365-4362.2003.01566.xSearch in Google Scholar

11. Santucci M , BiggeriA, FellerA, MassiD, BurgG. Efficacy of histologic criteria for diagnosing early mycosis fungoides: an EORTC cutaneous lymphoma study group investigation. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24(1):40-50. doi:10.1097/00000478-200001000-00005Search in Google Scholar

12. Murphy M , SignorettiS, KadinME, LodaM. Detection of TCR-gamma gene rearrangements in early mycosis fungoides by non-radioactive PCR-SSCP. J Cutan Pathol. 2000;27(5):228-234. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0560.2000.027005228.xSearch in Google Scholar

13. Michie SA , AbelEA, HoppeRT, WarnkeRA, WoodGS. Discordant expression of antigens between intraepidermal and intradermal T cells in mycosis fungoides. Am J Pathol. 1990;137(6):1447-1451.Search in Google Scholar

14. Diederen PV , van WeeldenH, SandersCJ, ToonstraJ, van VlotenWA. Narrowband UVB and psoralen-UVA in the treatment of early-stage mycosis fungoides: a retrospective study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48(2):215-219. doi:10.1067/mjd.2003.80Search in Google Scholar

15. Boztepe G , SahinS, AyhanM, ErkinG, KolemenF. Narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy to clear and maintain clearance in patients with mycosis fungoides. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53(2):242-246. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.03.012Search in Google Scholar

16. Gary W . Inflammatory diseases that simulate lymphomas: cutaneous pseudolymphomas. In: GoldsmithL, KatzS, eds. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Medical; 2012:1748-1760.Search in Google Scholar

17. Jones GW , RosenthalD, WilsonLD. Total skin electron radiation for patients with erythrodermic cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and the Sézary syndrome). Cancer. 1999;85(9):1985-1995.10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19990501)85:9%3C1985::AID-CNCR16%3E3.0.CO;2-OSearch in Google Scholar

18. Becker M , HoppeRT, KnoxSJ. Multiple courses of high-dose total skin electron beam therapy in the management of mycosis fungoides. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;32(5):1445-1449. doi:10.1016/0360-3016(94)00590-hSearch in Google Scholar

19. Fernandez-Guarino M . Emerging treatment options for early mycosis fungoides. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2013;6:61-69. doi:10.2147/ccid.s27482Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

20. Mori M , CampolmiP, MaviliaL, RossiR, CappugiP, PimpinelliN. Monochromatic excimer light (308 nm) in patch-stage IA mycosis fungoides. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50(6):943-945. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.01.047Search in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Nisticò SP , SaracenoR, SchipaniC, CostanzoA, ChimentiS. Different applications of monochromatic excimer light in skin diseases. Photomed Laser Surg. 2009;27(4):647-654. doi:10.1089/pho.2008.2317Search in Google Scholar PubMed

22. Nistico SP , CostanzoA, SaracenoR, ChimentiS. Efficacy of monochromatic excimer laser radiation (308 nm) in the treatment of early stage mycosis fungoides. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151(4):877-879. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.06178.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2018 American Osteopathic Association

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- LETTERS TO THE EDITOR

- Response

- OMT MINUTE

- Osteopathic Lymphatic Pump Techniques

- STILL RELEVANT?

- The Rule of the Artery Is Supreme. Or, Is It?

- LETTERS TO THE EDITOR

- Progressive Infantile Scoliosis Managed With Osteopathic Manipulative Treatment

- AOA COMMUNICATION (REPRINT)

- Official Call: 2018 Annual Business Meeting of the American Osteopathic Association

- Proposed Amendments to the AOA Constitution, Bylaws, and Code of Ethics

- ORIGINAL CONTRIBUTION

- Medical Students’ Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behaviors With Regard to Skin Cancer and Sun-Protective Behaviors

- Lymphatic Pump Treatment Mobilizes Bioactive Lymph That Suppresses Macrophage Activity In Vitro

- JAOA/AACOM MEDICAL EDUCATION

- Oral Health Training in Osteopathic Medical Schools: Results of a National Survey

- CASE REPORT

- Perplexing Rash: Challenges to Diagnosis and Management of Mycosis Fungoides

- Laparoscopic Adjustable Gastric Band Erosion Into the Stomach and Colon

- THE SOMATIC CONNECTION

- Safety of Chiropractic Manipulation in Patients With Migraines

- Effect of HVLA on Chronic Neck Pain and Dysfunction

- Effects of Adding Cervicothoracic Treatments to Shoulder Mobilization in Subacromial Impingement Syndrome

- Manipulation Under Anesthesia Thaws Frozen Shoulder

- Treating Patients With Low Back Pain: Evidence vs Practice

- Reducing Low Back and Posterior Pelvic Pain During and After Pregnancy Using OMT

- Neuromuscular Manipulation Improves Pain Intensity and Duration in Primary Dysmenorrhea

- Reducing Cesarean Delivery Rates and Length of Labor by Addressing Pelvic Shape

- Remote MFR Increases Hamstring Flexibility: Support for the Fascial Train Theory

- CLINICAL IMAGES

- Minocycline-Induced Hyperpigmentation

- Massively Enlarged Leiomyomatous Uterus

Articles in the same Issue

- LETTERS TO THE EDITOR

- Response

- OMT MINUTE

- Osteopathic Lymphatic Pump Techniques

- STILL RELEVANT?

- The Rule of the Artery Is Supreme. Or, Is It?

- LETTERS TO THE EDITOR

- Progressive Infantile Scoliosis Managed With Osteopathic Manipulative Treatment

- AOA COMMUNICATION (REPRINT)

- Official Call: 2018 Annual Business Meeting of the American Osteopathic Association

- Proposed Amendments to the AOA Constitution, Bylaws, and Code of Ethics

- ORIGINAL CONTRIBUTION

- Medical Students’ Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behaviors With Regard to Skin Cancer and Sun-Protective Behaviors

- Lymphatic Pump Treatment Mobilizes Bioactive Lymph That Suppresses Macrophage Activity In Vitro

- JAOA/AACOM MEDICAL EDUCATION

- Oral Health Training in Osteopathic Medical Schools: Results of a National Survey

- CASE REPORT

- Perplexing Rash: Challenges to Diagnosis and Management of Mycosis Fungoides

- Laparoscopic Adjustable Gastric Band Erosion Into the Stomach and Colon

- THE SOMATIC CONNECTION

- Safety of Chiropractic Manipulation in Patients With Migraines

- Effect of HVLA on Chronic Neck Pain and Dysfunction

- Effects of Adding Cervicothoracic Treatments to Shoulder Mobilization in Subacromial Impingement Syndrome

- Manipulation Under Anesthesia Thaws Frozen Shoulder

- Treating Patients With Low Back Pain: Evidence vs Practice

- Reducing Low Back and Posterior Pelvic Pain During and After Pregnancy Using OMT

- Neuromuscular Manipulation Improves Pain Intensity and Duration in Primary Dysmenorrhea

- Reducing Cesarean Delivery Rates and Length of Labor by Addressing Pelvic Shape

- Remote MFR Increases Hamstring Flexibility: Support for the Fascial Train Theory

- CLINICAL IMAGES

- Minocycline-Induced Hyperpigmentation

- Massively Enlarged Leiomyomatous Uterus