Caring for Patients With Chronic Pain: Pearls and Pitfalls

-

David J. Debono

Abstract

Chronic, nonmalignant pain is a substantial public health problem in the United States. Research over the past 2 decades has defined chronic pain by using a “biopsychosocial model” that considers a patient's biology and psychological makeup in the context of his or her social and cultural milieu. Whereas this model addresses the pathology of chronic pain, it also places many demands on the physician, who is expected to assess and manage chronic pain safely and successfully. There is a growing body of evidence suggesting that opioids can be effective in the management of chronic pain, but there has also been a rise in opioid-related overdoses and deaths. Clinicians should be aware of assessment tools that may be used to evaluate the risk of opioid abuse. A basic understanding of chronic pain pathophysiology and a uniform approach to patient care can satisfy the needs of both patients and physicians.

Abstract

Chronic pain is a substantial public health problem in the United States. The “biopsychosocial model,” which addresses the pathology of chronic pain, also places many demands on the physician, who is expected to play a major role in assessing and managing chronic pain. Despite a growing body of evidence that supports the efficacy of opioids in managing chronic pain, there has also been a rise in opioid-related overdoses and deaths. The authors examine nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies for chronic pain and address the unique issues of prescribing opioids, including addiction and patient-monitoring tools.

But pain is perfect misery, the worst

Of evils and, excessive, overturns

All patience…

—John Milton, Paradise Lost1

Pain is the most common reason a patient sees a physician. For most patients, pain is of short duration and quickly forgotten. Unfortunately, for some the pain does not pass but becomes a continuous burden, an unrelenting suffering, and the “perfect misery” described in Paradise Lost.1 With these patients, however, the physician faces one of the greatest challenges: the relief of chronic pain. In a 2011 report, authors at the Institute of Medicine2 underscored that “effective pain management is a moral imperative, a professional responsibility, and a duty of people in the healing profession.” Nonetheless, few physicians are formally trained in effectively managing pain, and achieving this goal remains problematic.

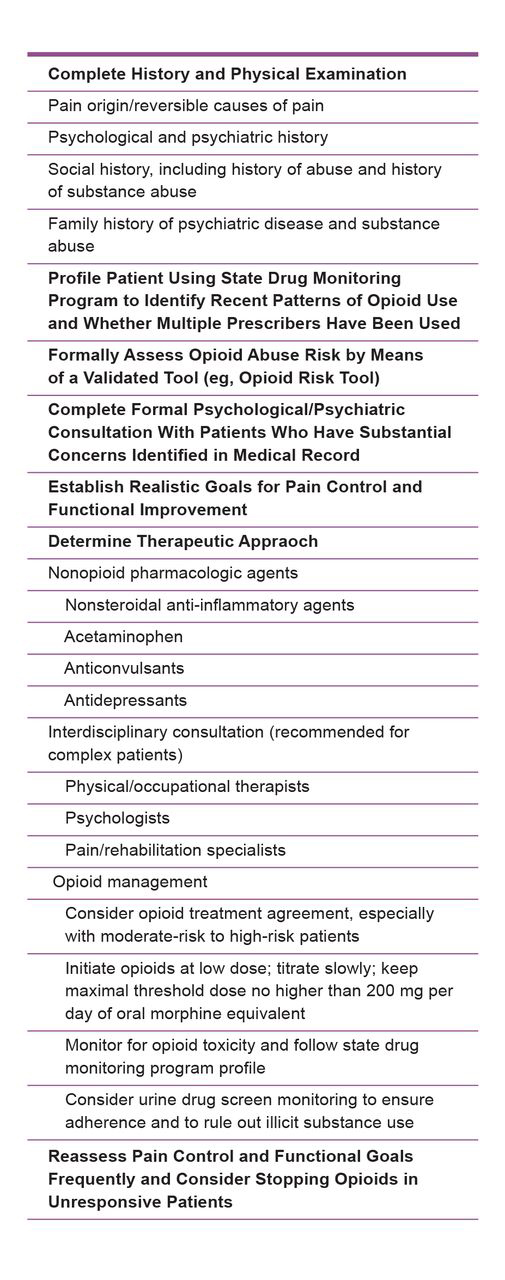

In the current review we examine chronic pain, discuss theories regarding its cause, evaluate nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapy, address the unique aspects of prescribing opioids, and provide a list of take-home points regarding the problem of chronic pain (Figure 1).

A structured approach for the optimal assessment and treatment of patients with chronic pain.

The Dilemma of Chronic Pain

Approximately 100 million individuals in the United States have chronic pain.2 This condition accounts for an estimated $560 billion to $635 billion per year in health costs and lost productivity.2 Despite the high prevalence of chronic pain, physicians are often poorly trained in managing the condition and have expressed considerable frustration as part of the emotional toll of that management.2,3 Upshur et al4 surveyed patients from 4 primary care facilities, who reported feeling distrusted and disrespected; physicians were also perceived as dismissive of pain symptoms that patients reported.

Chronic pain is defined as pain that persists for longer than 3 to 6 months, or the “normal healing” time of an injury.2 A physician may be frustrated by the lack of objective findings in a patient with chronic pain, because the extent of an injury does not always correlate with the severity of the patient's discomfort.

The “biopsychosocial model” is currently accepted as the optimal conceptual approach,5 one that envisions chronic pain in terms of the biological parameters in conjunction with the psychological, social, and cultural contexts of the patient.

Evidence2,6 suggests that genetic factors influence pain expression. These factors include variations in the transmission of nociceptive signals, differences in opioid receptor responsiveness, and differences in pain sensitivities.2 Functional neuroimaging has revealed a complex network of different areas of the brain in pain processing. Melzack6 developed the “neuromatrix theory,” which suggests that pain is “produced by the output of a widely distributed neural network that is genetically determined and modified by sensory experience.” Accordingly, chronic pain is affected by neural output and not only by sensory input from tissue injury.

The psychosocial context of chronic pain suggests a close relationship between a patient's emotional state and his or her chronic pain experience. Negative emotions can increase the perception of chronic pain,

whereas a positive emotional state can lead to a more favorable therapeutic response.2 In a study of 1323 individuals with chronic, disabling occupational spinal disorders,7 65% of patients had at least 1 psychiatric disorder and 56% had a major depressive disorder.

Nonpharmacologic Treatment

The biopsychosocial model requires a different approach to chronic pain than is commonly used with acute pain. Chronic pain management is more complex and may require the input of multiple disciplines rather than a single provider. Chou et al,8 working as a multidisciplinary panel convened by the American Pain Society, published guidelines for the management of chronic low back pain. They found strong evidence for noninvasive, interdisciplinary rehabilitation with a cognitive-behavioral emphasis in patients who do not respond to more invasive, single-provider interventions.8 Such intensive programs typically include physical and occupational therapy along with psychological or behavioral support.9

A close relationship exists between a patient's emotional state and his or her chronic pain experience

In 2007, Chou and Huffman published guidelines on behalf of the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society.10 The authors reviewed nonpharmacologic therapies for chronic low back pain and found good evidence that cognitive-behavioral therapy, progressive relaxation, exercise, functional restoration, and spinal manipulation were effective for chronic low back pain. They found fair evidence for acupuncture, massage therapy, and Viniyoga. In 2010, the Clinical Guideline Subcommittee on Low Back Pain11 reported that osteopathic manipulative treatment significantly reduced low back pain. Although no organizations or researchers, to our knowledge, have published guidelines on how best to use these interventions, each therapy presents a viable alternative to immediate pharmacologic interventions.

Pharmacologic Therapy

Ideally, chronic pain management begins with a clear diagnosis, resulting in a specific therapy addressing the underlying pathology rather than serving as the first step to nonspecific opioid therapy. Pharmacologic agents—such as anti-inflammatory agents, serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (eg, duloxetine, venlafaxine), tricyclic antidepressants (eg, amitriptyline), or calcium channel α 2-δ ligands (eg, gabapentin, pregabalin)—may be sufficient alone or synergistic if opioids are required.

Although well accepted for malignant pain, opioid therapy in chronic, nonmalignant pain is controversial because of the epidemic of prescription drug overdoses and deaths. In 2008, more than 14,000 unintentional drug overdose deaths occurred in the United States.12 From 1999 to 2008, more overdose deaths involved opioid analgesics than heroin and cocaine combined.13

Numerous clinical trials and guidelines on chronic pain therapy have been published.14-19 In 2010, Noble et al20 concluded that opioid therapy can cause significant pain reduction but found that long-term efficacy was inconclusive and difficult to evaluate. According to Noble et al, opioid therapy can be effective in reducing chronic nonmalignant pain, but the authors noted that published studies and reviews of long-term opioid therapy are scarce.

Optimal Doses for Opioid Therapy

In most trials of opioids for chronic pain, the dose was 200 mg/d or less of oral morphine equivalents.14-19 Ballantyne and Mao14 reported that patients who received higher doses rarely reported satisfactory analgesia or improved function. Kahan and colleagues,19 summarizing the guidelines of a 49-researcher panel in Canada, suggested that physicians use a maximum dose of 200 mg/d of an oral morphine equivalent for patients. The authors noted a lack of efficacy above that threshold, as well as a rise in opioid-related deaths.

Initially, short-acting opioids should be used to establish daily requirements. These requirements are then used to calculate an equivalent dose of a long-acting opioid. Pain occurring between doses (ie, breakthrough pain) is typically managed with short-acting doses that are 10% of the 24-hour opioid requirement (eg, if a patient requires 100 mg of long-acting oxycodone per day, a breakthrough dose should be 10 mg of short-acting oxycodone every 4 hours as needed). Physicians should prescribe extended-release formulations of a drug for most pain control applications. Most of the pain control comes from the extended-release formulations, with relatively infrequent need for breakthrough doses. If large doses of breakthrough medications are needed on a regular basis, then the physician should consider increasing the long-acting medication and evaluating whether the underlying problem is worsening. Discussion of opioid dosing and dose conversions can be complex and is beyond the scope of the present article. Many excellent resources exist, such as the National Cancer Institute's pain website.21

From 1999 to 2008, more overdose deaths involved opioid analgesics than heroin and cocaine combined

Dangers of Chronic Opioid Therapy

Although opioid therapy can be safely used in well-selected patients with chronic pain, problems remain. The most profound danger is unintentional drug overdose. Many factors place patients at risk for overdose, including a dose of greater than 100 mg/d of oral morphine equivalents, prescriptions from multiple providers or from non-medical sources, and polysubstance abuse.22-24 A study by Webster and Webster25 of fatal overdoses in Canada revealed that 56% of the patients had received an opioid prescription within 4 weeks of their deaths.

The rate of drug addiction as a result of opioid therapy is low. In the review by Noble et al,20 the rate of addiction was calculated to be 0.27%. In another meta-analysis26 that specifically evaluated abuse behaviors, the rate of abuse or addiction was 3.27%.

Adverse events in patients with chronic pain who undergo opioid therapy are common. Although respiratory depression is often encountered, its risk is low when opioids are initiated at a low dose and titrated slowly. Other adverse effects include sedation, cognitive dysfunction, constipation, and myoclonus. Patients typically develop tolerance to sedation, whereas cognitive changes tend to resolve within 7 days after a dosage increase.14 Constipation occurs in most patients and should be managed aggressively because patients do not develop tolerance to this adverse effect. Myoclonus is infrequently seen but can be treated by changing to a different opioid or decreasing the dosage.

A maximum dose of 200 mg oral morphine equivalent per day is recommended.

The use of transdermal fentanyl presents unique problems because the drug has a variable rate of absorption (ie, peak concentrations do not occur for 12-16 hours) and a prolonged half-life.27 Transdermal fentanyl should not be initiated unless a patient has demonstrated tolerance to an alternative opioid. Initial dosing should be calculated from the daily maintenance dose of shorter-acting opioids.

Methadone is often used in a patient whose condition requires a high dosage of opioids. Numerous drug and food interactions, nonlinear kinetics, and a widely variable half-life are a few of the challenges associated with methadone, and only physicians who are experienced with its complex pharmacology should prescribe the drug.

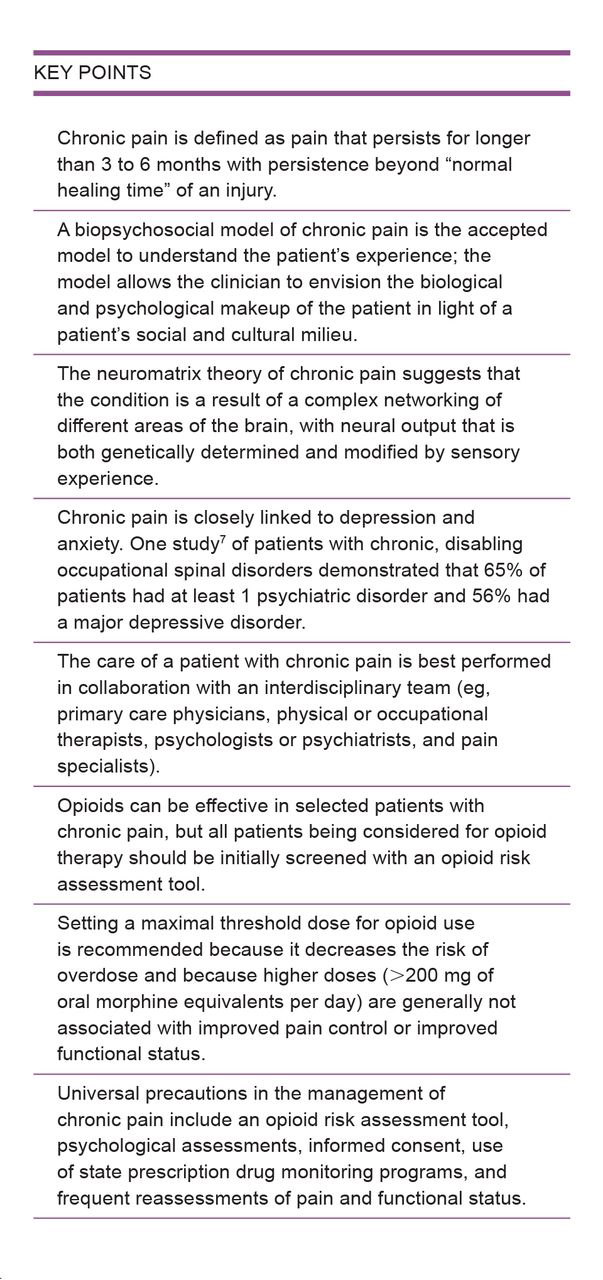

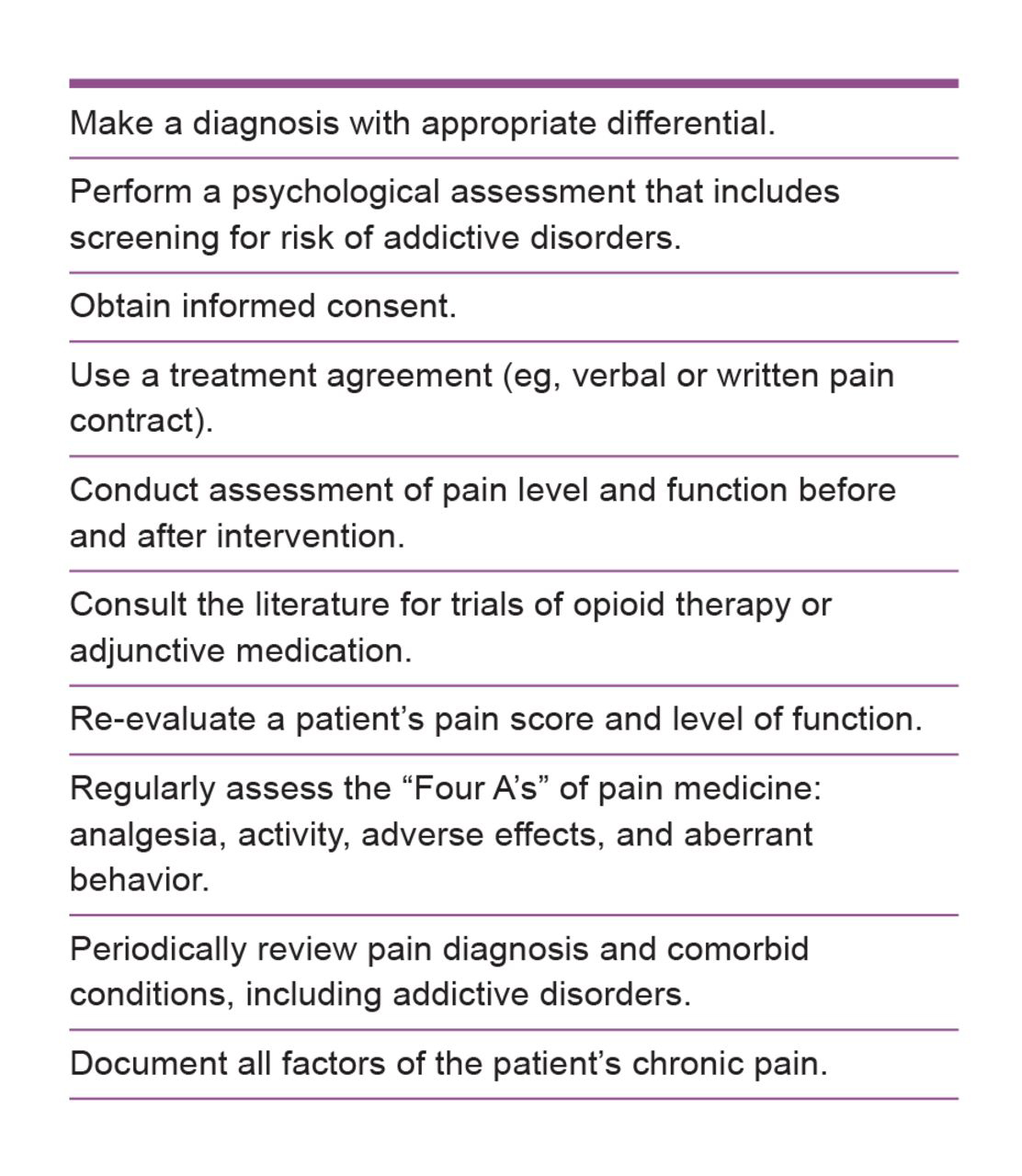

Universal Precautions

When assessing chronic pain, a physician should take a standardized approach that has become known as universal precautions (Figure 2).28 An initial evaluation should include a complete history and physical examination, an assessment of coincident psychiatric or addictive disorders, and an exploration of reversible causes of pain. The patient should work in tandem with the physician to understand the conditions of informed consent, implement possible treatment contracts, and set realistic goals for pain reduction and functional improvement.

Recommended actions for physicians who treat patients for chronic pain. Adapted from Gourlay DL, Heit HA, Almahrezi A. Universal precautions in pain medicine: a rational approach to the treatment of chronic pain. Pain Med. 2005;6(2):107-112.

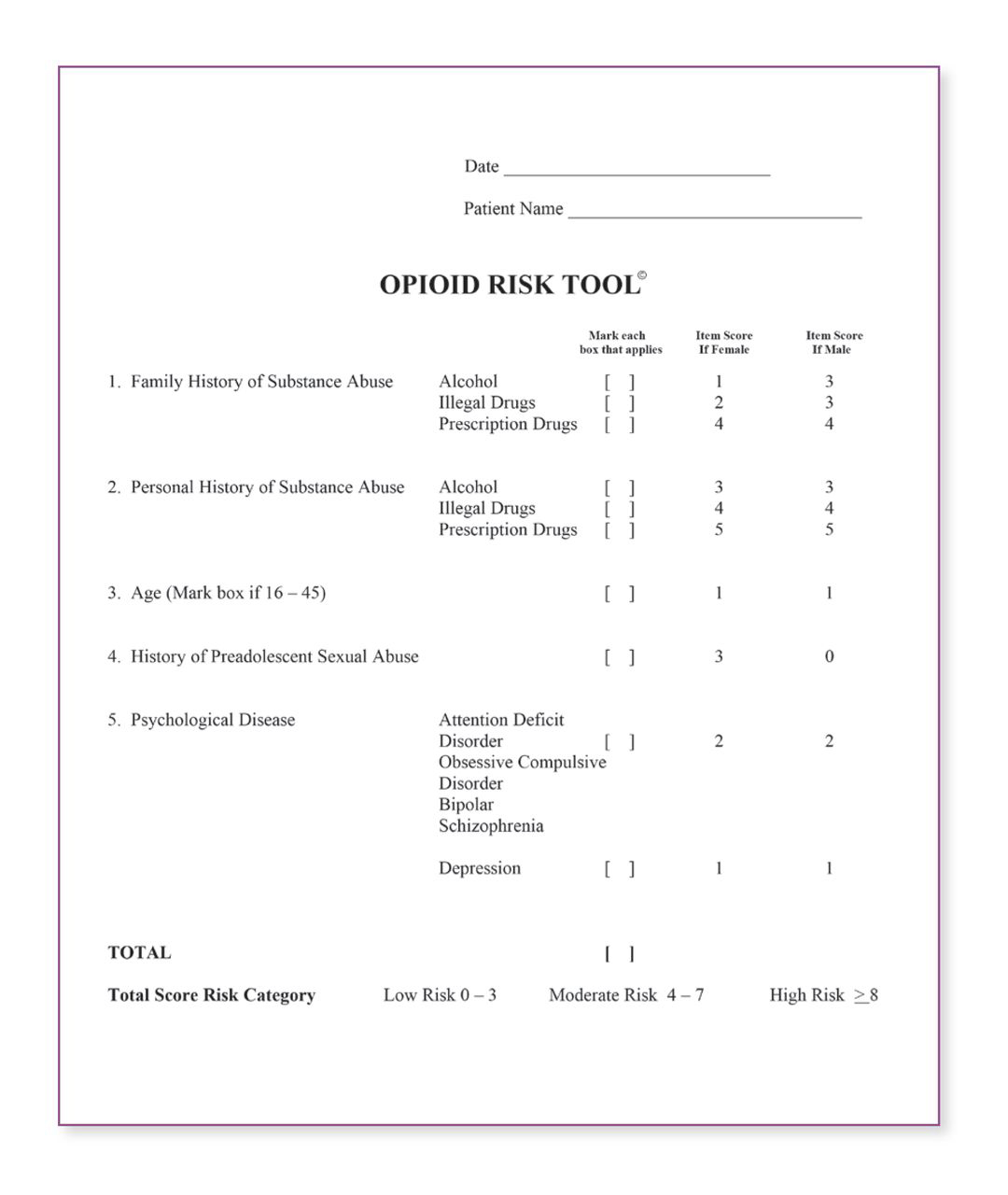

Tools to Screen for Substance Abuse

Researchers have developed several tools to assess the risk of substance abuse. The Opioid Risk Tool29 (Appendix) is a 5-item tool designed for the primary care setting that assesses the risk of aberrant behaviors for patients with chronic pain who have prescriptions for opioids. The Opioid Risk Tool allows providers to stratify patients into low-, moderate-, or high-risk categories on the basis of a participant's responses to questions regarding age, family and personal history of substance abuse, history of preadolescent sexual abuse, and psychological disease.

Role of Opioid Contracts and Urine Drug Screening

Starrels et al,30 in a systematic review from 2010, found little evidence to support the effectiveness of urine drug screening and opioid treatment agreements (ie, pain contracts) in reducing opioid misuse. However, some physicians find drug testing and pain contracts helpful in establishing dialogue and setting expectations, using them either routinely or selectively for high-risk patients.

Before performing urine drug screening, physicians should understand how to recognize false-positive and false-negative test results, as well as how changes in drug metabolism can distort findings.31

Role of State Monitoring Programs

Currently in the United States, 49 states and 1 territory have legislation authorizing the creation of a Prescription Monitoring Program, with 42 states having an operational system.32 These programs help prevent prescription drug abuse by identifying patients who have obtained multiple prescriptions from different physicians or from multiple pharmacies. These programs are not, however, designed to identify a patient who obtains an excessive quantity of a drug from a single provider or who obtains medications across state lines.

Conclusion

Milton's apt description of pain as “perfect misery”1 is one that the physician might keep in mind when treating a patient with chronic pain. Pain, by its nature, demands considerable attention and draws an individual away from friends, family, and personal interests, often leading to protracted suffering and isolation from activities that enhanced the patient's life. Nationwide, the successful management of chronic pain remains a profound challenge because of inadequate medical training, the potential for patient drug abuse, and the risk of prescribing potentially addictive drugs. Physicians should strive to overcome these challenges and, by doing so, realize the opportunity they have to mitigate suffering and restore a patient's quality of life.

Appendix

An opioid risk assessment tool, which physicians can use to evaluate potential aberrant behavior in a patent who has been prescribed opioids.

-

Financial Disclosures: None reported.

References

1 Milton J . Paradise Lost. New York, NY: The Odyssey Press; 1935.Search in Google Scholar

2 Committee on Advancing Pain Research, Care, and Education, Institute of Medicine Board on Health Sciences Policy . Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. http://books.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=13172. Accessed November 13, 2012.Search in Google Scholar

3 Matthias MS Parpart AL Nyland KA et al. . The patient-provider relationship in chronic pain care: providers' perspectives. Pain Med.2010;11(11):1688-1697.10.1111/j.1526-4637.2010.00980.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

4 Upshur CC Bacigalupe G Luckmann R . “They don't want anything to do with you”: patient views of primary care management of chronic pain. Pain Med.2010;11(12):1791-1798.10.1111/j.1526-4637.2010.00960.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

5 Gatchel RJ Peng YB Peters ML Fuchs PN Turk DC . The biopsychosocial approach to chronic pain: scientific advances and future directions. Psychol Bull.2007;133(4):581-624.10.1037/0033-2909.133.4.581Search in Google Scholar PubMed

6 Melzack R . Evolution of the neuromatrix theory of pain: The Prithvi Raj Lecture—presented at the third World Congress of World Institute of Pain, Barcelona 2004. Pain Practice. 2005;5(2):85-94.10.1111/j.1533-2500.2005.05203.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

7 Dersh J Gatchel RJ Mayer T Polatin P Temple OR . Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in patients with chronic disabling occupational spinal disorders. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31(10):1156-1162.10.1097/01.brs.0000216441.83135.6fSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

8 Chou R Loeser JD Owens DK et al. . Interventional therapies, surgery, and interdisciplinary rehabilitation for low back pain: an evidence-based clinical practice guideline from the American Pain Society. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34(10):1066-1077.10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181a1390dSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

9 Stanos S . Focused review of interdisciplinary pain rehabilitation programs for chronic pain management. Curr Pain Headache Rep.2012;16(2):147-152.10.1007/s11916-012-0252-4Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10 Chou R Huffman LH . Nonpharmacologic therapies for acute and chronic low back pain: a review of the evidence for an American Pain Society/American College of Physicians clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med.2007;147(7):492-504.10.7326/0003-4819-147-7-200710020-00007Search in Google Scholar PubMed

11 Clinical Guideline Subcommittee on Low Back Pain . American Osteopathic Association guidelines for osteopathic manipulative treatment (OMT) for patients with low back pain. J Am Osteopath Assoc.2010;110(11):653-666.Search in Google Scholar

12 Policy impact: prescription painkiller overdoses. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. http://www.cdc.gov/homeandrecreationalsafety/rxbrief. Accessed May 7, 2012.Search in Google Scholar

13 Paulozzi LJ Jones CM Mack KA Rudd RA . Vital signs: overdoses of prescription opioid pain relievers—United States, 1999-2008. MMWR. 2011;60(43):1487-1492.Search in Google Scholar

14 Ballantyne JC Mao J . Opioid therapy for chronic pain. N Engl J Med.2003;349(20):1943-1953.10.1056/NEJMra025411Search in Google Scholar PubMed

15 Kalso E Edwards JE Moore RA McQuay HJ . Opioids in chronic non-cancer pain: systematic review of efficacy and safety. Pain. 2004;112(3):372-380.10.1016/j.pain.2004.09.019Search in Google Scholar PubMed

16 Rosenblum A Marsch LA Joseph H Portenoy RK . Opioids and the treatment of chronic pain: controversies, current status, and future directions. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol.2008;16(5):405-416.10.1037/a0013628Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

17 Chou R Fanciullo GJ Fine PG et al. . Clinical guidelines for the use of chronic opioid therapy in chronic noncancer pain. J Pain. 2009;10(2):113-130.10.1016/j.jpain.2008.10.008Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

18 Fine PG Finnegan T Portenoy RK . Protect your patients, protect your practice: practical risk assessment in the structuring of opioid therapy in chronic pain. J Fam Pract.2010;59(9 suppl 2):S1-S16.Search in Google Scholar

19 Kahan M Mailis-Gagnon A Wilson L Srivastava A . Canadian guideline for safe and effective use of opioids for chronic noncancer pain—clinical summary for family physicians, part 1: general population. Can Fam Physician. 2011;57(11):1257-1266.Search in Google Scholar

20 Noble M Treadwell JR Tregear SJ et al. . Long-term opioid management for chronic noncancer pain [review]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.2010;1:CD006605.10.1002/14651858.CD006605.pub2Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

21 Pain (PDQ). National Cancer Institute website. http://cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/supportivecare/pain/HealthProfessional. Updated 0503, 2012. Accessed June 11, 2013.Search in Google Scholar

22 Dunn KM Saunders KW Rutter CM et al. . Opioid prescriptions for chronic pain and overdose: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med.2010;152(2):85-92.10.7326/0003-4819-152-2-201001190-00006Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

23 Bohnert ASB Valenstein M Bair MJ et al. . Association between opioid prescribing patterns and opioid overdose-related deaths. JAMA. 2011;305(13):1315-1321.10.1001/jama.2011.370Search in Google Scholar PubMed

24 Hall AJ Logan JE Toblin RL et al. . Patterns of abuse among unintentional pharmaceutical overdose fatalities. JAMA. 2008;300(22):2613-2620.10.1001/jama.2008.802Search in Google Scholar PubMed

25 Webster LR Webster RM . Predicting aberrant behaviors in opioid-treated patients: preliminary validation of the Opioid Risk Tool. Pain Med.2005;6(6):432-442.10.1111/j.1526-4637.2005.00072.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

26 Fishbain DA Cole B Lewis J Rosomoff HL Rosomoff RS . What percentage of chronic nonmalignant pain patients exposed to chronic opioid analgesic therapy develop abuse/addiction and/or aberrant drug-related behaviors? a structured evidence-based review. Pain Med.2008;9(4):444-459.10.1111/j.1526-4637.2007.00370.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

27 Kornick CA Santiago-Palma J Moryl N Payne R Obbens EA . Benefit-risk assessment of transdermal fentanyl for the treatment of chronic pain. Drug Saf. 2003;26(13):951-973.10.2165/00002018-200326130-00004Search in Google Scholar PubMed

28 Gourlay DL Heit HA Almahrezi A . Universal precautions in pain medicine: a rational approach to the treatment of chronic pain. Pain Med.2005;6(2):107-112.10.1111/j.1526-4637.2005.05031.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

29 Webster LR Webster RM . Predicting aberrant behaviors in opioid-treated patients: preliminary validation of the opioid risk tool. Pain Med.2005;6(6):432-442.10.1111/j.1526-4637.2005.00072.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

30 Starrels JL Becker WC Alford DP Kapoor A Williams AR Turner BJ . Systematic review: treatment agreements and urine drug testing to reduce opioid misuse in patients with chronic pain. Ann Intern Med.2010;152(11):712-720.10.7326/0003-4819-152-11-201006010-00004Search in Google Scholar PubMed

31 Christo PJ Manchikanti L Ruan X et al. . Urine drug testing in chronic pain. Pain Physician. 2011;14(2):123-143.10.36076/ppj.2011/14/123Search in Google Scholar

32 Prescription monitoring frequently asked questions (FAQ). Alliance of States with Prescription Monitoring Programs website. http://www.pmpalliance.org/content/prescription-monitoring-frequently-asked-questions-faq. Accessed March 27, 2012.Search in Google Scholar

© 2013 The American Osteopathic Association

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Abstracts

- 57th Annual AOA Research Conference—Abstracts, 2013

- Editorial

- Search for a New Editor in Chief

- Osteopathic Research Conference 2013: “From Bench to Bedside”

- Letters to the Editor

- The Effect of OMT on Postoperative Medical and Functional Recovery of Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Patients

- Response

- Relighting the Fire in Our Bellies

- Original Contribution

- Mathematical Analysis of the Flow of Hyaluronic Acid Around Fascia During Manual Therapy Motions

- Exercise During Pregnancy: The Role of Obstetric Providers

- Evidence-Based Clinical Review

- Caring for Patients With Chronic Pain: Pearls and Pitfalls

- Medical Education

- Incorporating Simulation Technology Into a Neurology Clerkship

- Case Report

- Conservative Approach to Tardive Dyskinesia–Induced Neck and Upper Back Pain

- Clinical Images

- Fibrous Dysplasia of the Craniofacial Bones

- In Your Words

- One of Ours

Articles in the same Issue

- Abstracts

- 57th Annual AOA Research Conference—Abstracts, 2013

- Editorial

- Search for a New Editor in Chief

- Osteopathic Research Conference 2013: “From Bench to Bedside”

- Letters to the Editor

- The Effect of OMT on Postoperative Medical and Functional Recovery of Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Patients

- Response

- Relighting the Fire in Our Bellies

- Original Contribution

- Mathematical Analysis of the Flow of Hyaluronic Acid Around Fascia During Manual Therapy Motions

- Exercise During Pregnancy: The Role of Obstetric Providers

- Evidence-Based Clinical Review

- Caring for Patients With Chronic Pain: Pearls and Pitfalls

- Medical Education

- Incorporating Simulation Technology Into a Neurology Clerkship

- Case Report

- Conservative Approach to Tardive Dyskinesia–Induced Neck and Upper Back Pain

- Clinical Images

- Fibrous Dysplasia of the Craniofacial Bones

- In Your Words

- One of Ours