Abstract

Osteoarthritis (OA) is one of the major causes of disability and pain worldwide, yet despite a massive international research effort, no effective disease-modifying drugs have been identified to date. In this review, we put forward the proposition that greater focus on rarer forms of OA could lead to a better understanding of the pathogenesis of more common OA. We have investigated the severe osteoarthropathy of the ultra-rare disease alkaptonuria (AKU). In addition to the progress made in finding a treatment for AKU, our research has revealed important lessons for more common OA, including the identification of high-density mineralized protrusions (HDMPs), new pathoanatomical structures which may play an important role in joint destruction and pain in AKU and in OA. AKU is an inherited disorder of tyrosine metabolism, caused by genetic lack of the enzyme homogentisate 1,2 dioxygenase (HGD), which leads to failure to breakdown homogentisic acid (HGA). While most HGA is excreted over time, some of it is deposited as a pigment in connective tissues, a process described as ochronosis. Ochronotic pigment alters the mechanical properties of tissues, leading to inevitable joint destruction and frequently to cardiac valve disease. Until recently, there was no effective therapy for AKU, but preclinical studies demonstrated that upstream inhibition of tyrosine metabolism by nitisinone, a drug previously used in hereditary tyrosinaemia 1 (HT1), completely prevented ochronosis in AKU mice. This was followed by successful clinical trials which have resulted in nitisinone being approved for therapy of AKU by the European Medicines Agency, making AKU the only cause of OA for which there is an effective therapy to date. Study of other rare causes of OA should be a higher priority for researchers and funders to ensure further advances in understanding and eventual therapy of OA.

Alkaptonuria

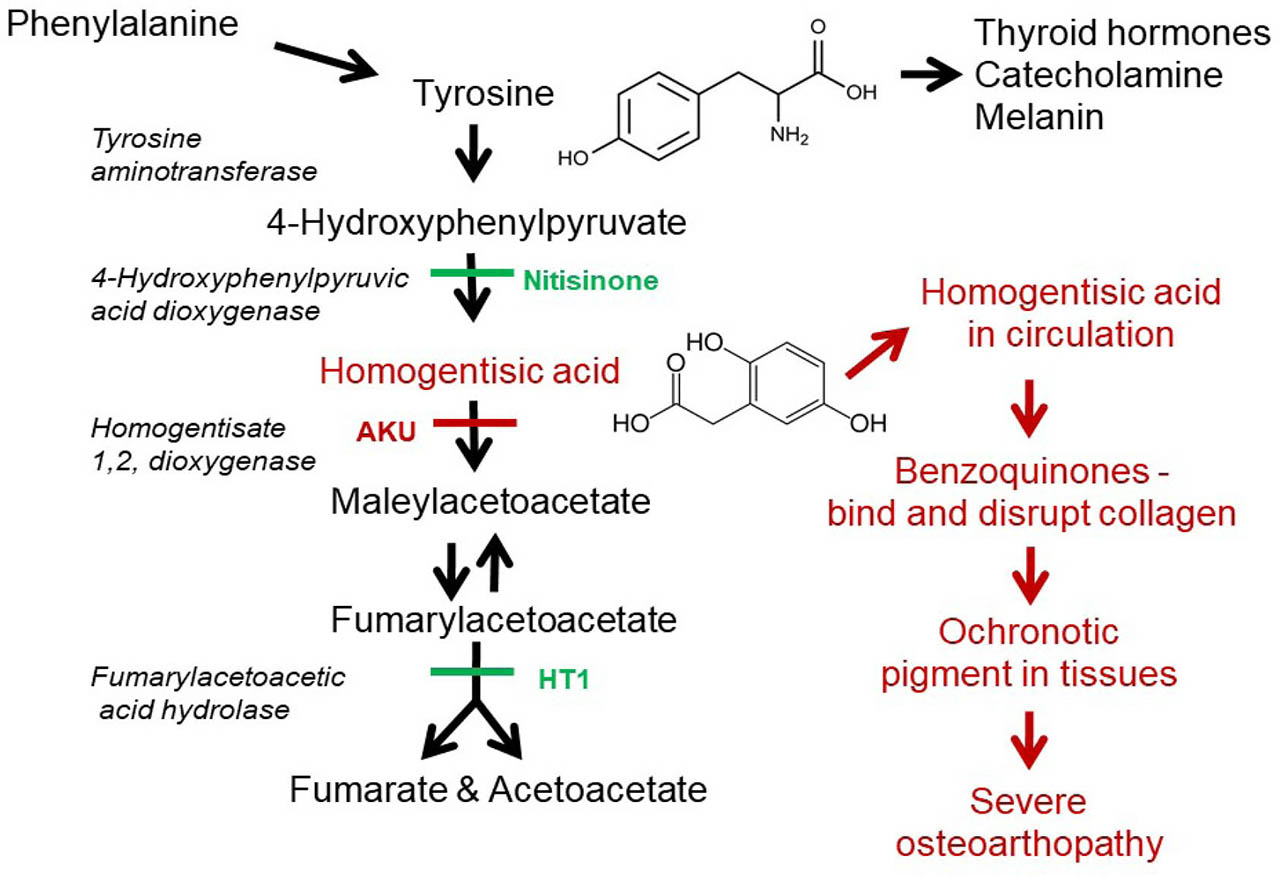

Alkaptonuria (AKU) is a metabolic disorder that leads to severe and early onset osteoathropathy, mainly affecting the spine and the large weight bearing joints. Until 2020, the only treatment available for AKU was pain relief medication, physiotherapy, lifestyle counseling, and eventual joint replacement.[1] AKU is an iconic disease; it was the first human disorder recognized to conform to Mendelian autosomal recessive inheritance by Archibald Garrod over 100 years ago.[2] It arises from homozygous or compound heterozygous mutations in the homogentisate 1,2 dioxygenase (HGD) gene encoding HGD [E.C.1.13.11.5], an enzyme in the metabolism of tyrosine and phenylalanine as shown in Figure 1.[1]

Tyrosine metabolic pathway highlighting the enzyme defects responsible for AKU and HT1, the putative ochronotic pathway, and the site of action of nitisinone. AKU, alkaptonuria; HT1, hereditary tyrosinaemia 1.

The prevalence of AKU is estimated to be around 1 in 250,000 but rises to 1 in 19,000 in the Dominican Republic and in Slovakia.[3] Recent studies have also identified that there is a high incidence of AKU in some villages in Jordan[4] and in a gypsy community in India.[1] In fact, it is highly likely that there are vast reservoirs of undiagnosed AKU globally, especially in regions where consanguinity is practiced. The affected gene which codes for HGD has been mapped to human chromo-some 3q13.33 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/3081). It is a mutational hotspot with over 200 mutations identified distributed throughout the entire gene.[3] The most frequent mutations are missense variants (68.3%), followed by splicing (13.4%) and frameshift (11.3%) mutations.[3] Many of the mutations have been found in a small region in the northwest of Slovakia, and there is currently no explanation for this increased incidence. In contrast, the high incidence of AKU in the Dominican Republic can be explained through a classical founder effect.[5]

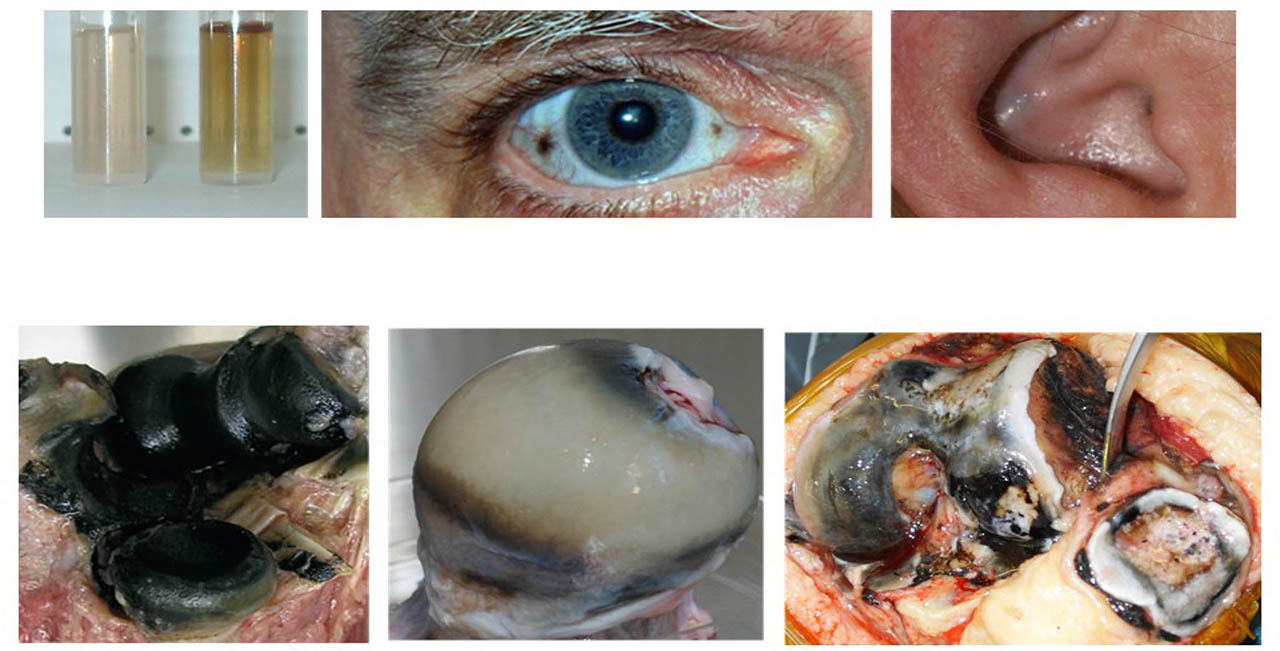

Loss of HGD enzyme activity increases the circulating concentration and urinary excretion of homogentisic acid (HGA), the culprit molecule in AKU. HGA in urine causes it to darken on standing, a process that can be accelerated by the addition of alkali (see Figure 2). Despite the efficient excretion of most of the HGA that is synthesized, over time, some of it is deposited as a pigment in connective tissues, a process described as ochronosis. Ochronotic pigment is predominantly deposited in cartilage, as seen in Figure 2, and this leads to severe, early onset osteoarthritis (OA). There are few symptoms or signs of AKU before the late 20s or early 30s, apart from constant dark urine and sometimes renal stones, but during the third decade, progressive arthritic pain starts to affect synovial joints.[1] At the same time, serious and painful spinal disease also develops leading to progressive kyphoscoliosis and impaired spinal and thoracic mobility. This causes poor pulmonary inflation, decreased respiratory reserve, and disc disease and prolapse resulting in spinal stenosis, cord compression, and myelopathy. Visible signs of ochronosis become evident in eyes and ears as illustrated in Figure 2. Spondyloarthopathy leads to constant pain, difficulty with activities of daily living, poor sleep, depression, poor quality of life, unemployment, and isolation. Together with joint damage, manifestations of AKU include other effects due to high HGA, in particular: stones in the kidney, prostate, gall bladder, and salivary gland; ruptures of tendons, ligaments, or muscles; and osteopenia and fractures.[1,6,7]. Heart valve disease is common, requiring valve replacement.[8]

Pigmentation and ochronosis in AKU. Upper left panel, darkening of AKU urine following addition of alkali. Upper central panel, ochronotic pigmentation of the sclera of the eye. Upper right panel, darkening of the conchal bowl of the external ear due to ochronosis of the underlying elastic cartilage. Lower left panel, an elbow joint observed at autopsy (adapted with permission from Ref. 10). Lower central panel, a femoral head removed from a patient because of persistent lancinating pain. Pigmentation is most intense in the deeper layers of the cartilage. The cartilage is generally intact. Further study of this sample with advanced imaging techniques lead to the identification of HDMPs shown in Figure 5. Lower right panel, a photomicrograph taken during knee replacement surgery (adapted with permission from Ref. 17). There is pigmentation of the femoral, tibial, and patellar hyaline cartilages. Areas of cartilage fragmentation and loss can be observed on the surface of the femur of the articular cartilage. AKU, alkaptonuria; HDMPs, high-density mineralized protrusions.

Ochronosis

Ochronosis is the cause of the debilitating morbidity in AKU.[9] It involves the selective deposition of HGA-derived pigment in collagenous tissues, particularly cartilage, fibrocartilage, and ligaments, whereas other tissues including liver and brain are unaffected. Ochronosis changes the mechanical properties of tissues which ultimately leads to their dysfunction and degeneration. Ochronosis cannot be fully reversed, and this will be a key factor in influencing treatment decisions. Despite the importance of ochronosis in AKU pathology, the molecular mechanism of pigment formation has not been fully elucidated.

Studies on tissue samples from patients with AKU,[10,11] the in-vitro model of ochronosis,[12] and the mouse AKU model[13,14] have confirmed that HGA is the key molecule that drives ochronosis.[9] However, these studies have also revealed that tissues are initially resistant to pigmentation but become susceptible following biomechanical and biochemical influences on the composition or structure of the extracellular matrix (ECM).

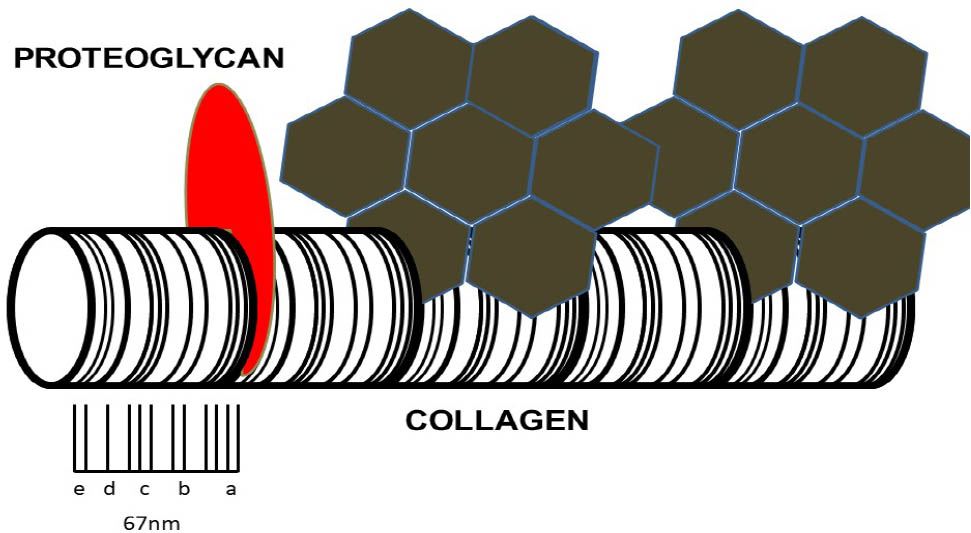

Early pigmentation has been shown to be associated ultra-structurally with the periodicity of collagen,[15] somewhat reminiscent of proteoglycan (PG) binding.[16] This pattern strongly indicates that there are specific sites on collagen where HGA can bind but which are protected in native collagen in undamaged ECM. PGs and other molecules decorating collagen could repel HGA, an acidic molecule with a pKa value of 3.57. However, following structural and compositional changes, including loss of PGs, the potential binding sites become exposed, allowing HGA to bind. We describe this as the “exposed collagen hypothesis,” which is illustrated in Figure 3.[17] The initial binding appears to be similar to a nucleation event which is followed by rapid deposition of HGA as a pigmented polymer. Binding of HGA-derived pigment to the collagen fibers makes them stiffer and susceptible to more mechanical damage.[9] This leads to further ultrastructural changes in collagen, increased exposure of binding sites to HGA, and a downward spiral of pigmentation. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) findings are supported by solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance (ssNMR) studies which revealed loss of order at the nanoscale and loss of PGs.[18] ssNMR further revealed that both synthetic pigment and pigmented human cartilage tissues show hydroquinone-like signals, and electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy showed that the synthetic pigment also contains radicals.[19] Moreover, intrastrand disruption of the collagen triple helix was observed in pigmented AKU human cartilage and in the cartilage of patients with OA.[19] These findings suggest that collagen degradation can occur via transient glycyl radicals, the formation of which is enhanced in AKU due to the redox environment generated by pigmentation.

The exposed collagen hypothesis. Schematic representation of collagen fibril with characteristic periodicity. On the left-hand side, the collagen fibril is decorated with a protective proteoglycan molecule (red). Further along the fibrils, proteoglycans have been lost as a result of repetitive mechanical loading, chemical attack, or aging and degeneration. This has allowed HGA to bind to the exposed aspects of collagen fibril. The initial binding of HGA functions as a nucleation event and is followed by further rapid deposition of HGA as a pigmented polymer. Binding of HGA-derived pigment to the collagen fibrils makes them stiffer and susceptible to more mechanical damage. This leads to further ultrastructural changes in collagen, increased exposure to HGA, and a downward spiral of increasing pigmentation (adapted with permission from Ref. 17). HGA, homogentisic acid.

Mouse model of AKU

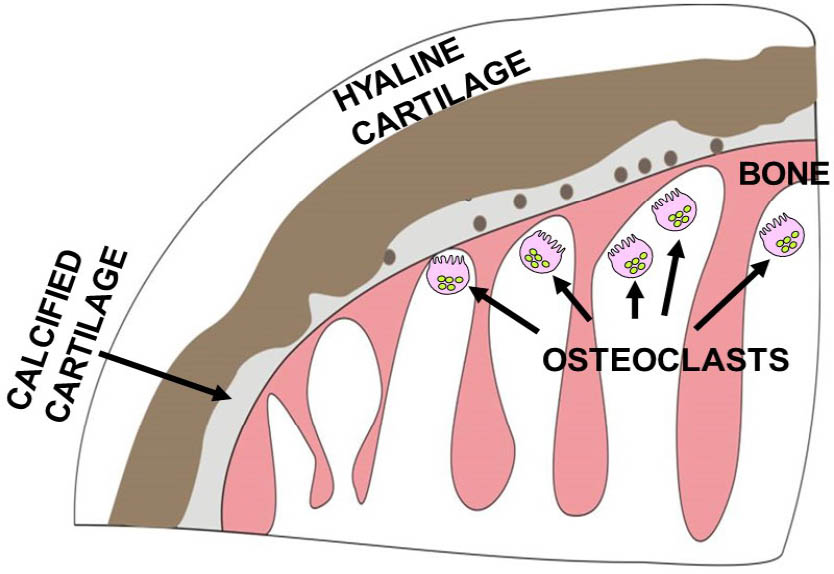

The first AKU mouse model was generated by N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU) mutagenesis at the Pasteur Institute in Paris. The AKU phenotype was identified by Montagutelli et al.[20] due to darkened cage bedding, caused by elevated HGA in the urine. Initially, these mice were believed to be a good genetic and metabolic model for AKU, but it was thought that they did not develop ochronosis.[21] However, careful histological examination using a modified Schmorl’s stain revealed that these mice developed cartilage lesions, identical to the early stages of arthropathy in AKU patients (see Figure 4).[13,14] This AKU model demonstrated relatively stable increased plasma HGA levels, the first reported in an AKU animal model, and extensive chondrocyte pigmentation. Deposition of pigment is initiated in the territorial matrix of individual chondrocytes in calcified cartilage (CAC) and then progresses to the intracellular compartment.[22] Pigmentation then proliferates throughout the hyaline cartilage. The ability to score the number of pigmented chondrocytes in the tibiofemoral joint revealed a linear increase in pigmentation with age. This AKU mouse model has provided the means to study early ochronosis in a predictable and systematic manner and to allow the investigation of potential therapeutic agents.

Schematic representation of joint destruction in ochronosis. Ochronosis begins with the deposition of pigment in individual chondrocytes and their territorial matrix in calcified cartilage. Pigmentation then proliferates throughout the hyaline cartilage. Ochronotic cartilage shields the underlying bone from normal mechanical loading leading to aggressive resorption of the subchondral plate and underlying trabeculae by osteoclasts. Despite the increased stiffness, the pigmented shell of the remaining articular cartilage fails catastrophically.

Treatment with nitisinone

Nitisinone, (2-[2-nitro-4-(trifluoromethyl)benzoyl]-1,3-cyclohexanedione, C14H10F3NO5, MW 329.2), is an inhibitor of p-hydroxyphenyl-pyruvate dioxygenase (4-HPPD) in the tyro-sine metabolic pathway (Figure 2) which was first developed as a herbicide.[23] It is chemically related to leptospermone, a phytotoxin discovered in the Australian bottlebrush plant. Nitisinone is a highly effective therapy for another genetic disease of tyrosine metabolism, hereditary tyrosinemia type 1 (HT1, OMIM 276700),[24] and has transformed the lives of patients with that disorder.[25]

Nitisinone was effective at lowering HGA in AKU patients, but an early clinical trial at the National Institute of Health, USA, failed to demonstrate an improvement in musculoskeletal function,[26] probably because of the slow progression of the disease, the type of assessment undertaken, and the limited number of patients in the trial. However, in preclinical studies, we were able to demonstrate that nitisinone was completely effective at preventing ochronosis in the AKU mouse,[14] and when administered mid-life, it was shown to arrest, but not reverse, further ochronosis.[27] Following these findings, we received funding from the European Commission as part of the Framework Programme 7 (EUFP7) for the DevelopAKUre Programme to undertake clinical trials on nitisinone. In the dose-ranging study of suitability of nitisinone in AKU 1 (SONIA 1), 8 mg of nitisinone was effective at lowering circulating HGA in AKU patients.[28] This was followed by a 4-year randomized multicentre international clinical study, called suitability of nitisinone in AKU 2 (SONIA 2), which not only confirmed the decrease in serum and urine HGA levels but also demonstrated a decrease in eye ochronosis and a slowing down of clinical disease progression as assessed by AKU severity score index (AKUSSI), a validated AKU severity score index.[29,30] These studies have contributed to the approval of nitisinone as the first disease-modifying treatment of adult AKU by the European Medicines Agency and the European Commission.

Lessons for OA

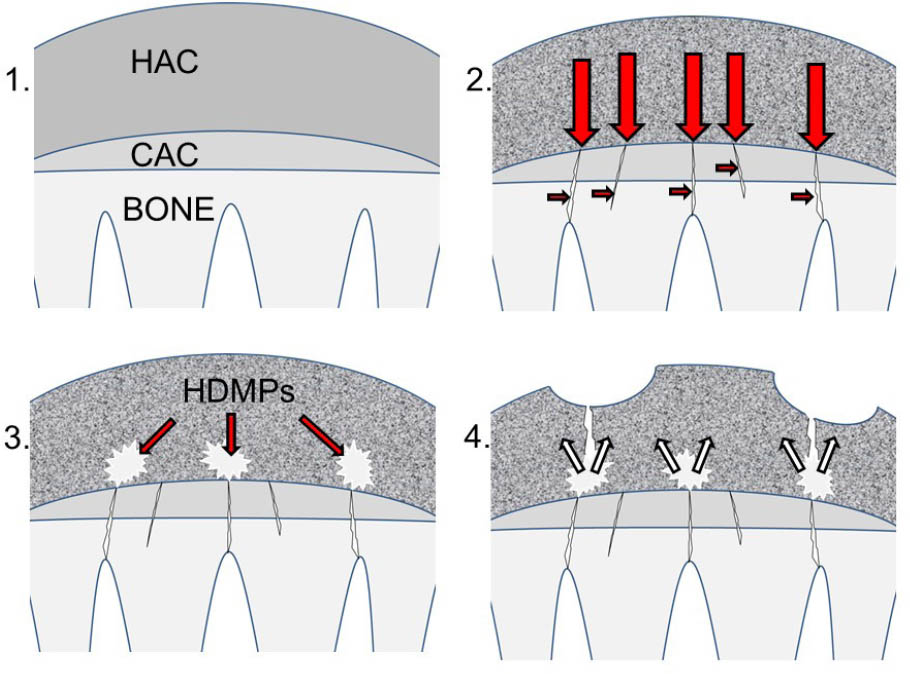

In addition to the progress in finding an effective therapy for AKU, one striking thing that has emerged from research on AKU is that, by studying this rare disease, important lessons have been learnt for more common OA. Rare diseases are a neglected area of study in OA research, but our experience is that greater focus on rare syndromes leads to more rapid advancement, as forecast by 2 of the great English medical scientists of the 17th and 19th centuries, William Harvey and William Bateson [discussed in Ref. 17]. In the extreme phenotypes of Mendelian disorders, disease progression is often rapid and predictable, so it is easier to identify the initiation and subsequent advance of pathological changes. Studies on tissue samples from patients with AKU and from the mouse model of the disease have revealed previously unrecognized microanatomical, cellular, and biochemical features in joints which have been subsequently also recognized in human OA. These include trabecular excrescences in bone[31] and circumferential lamellae in CAC.[32] Of the many lessons learnt from AKU, one that stands out as providing a paradigm shift in our understanding of the pathogenesis of OA and points to new routes for diagnosis and therapy is the identification of high-density mineralized protrusions (HDMPs) (Figure 5). The first discovery of the occurrence of HDMPs in humans came through a study of a severely affected hip joint in an individual with AKU.[33] The patient suffered extreme pain, leading to elective hip surgery. Anatomical examination of his femoral head ex vivo revealed no significant loss of cartilage from the articular surface. Subsequent investigation by micro-computerised tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and scanning electron microscopy revealed HDMPs, regions of ultra-dense material arising from the mineralizing front of the CAC and protruding into the hyaline cartilage. The HDMPs appeared to arise from fluid extruded through microscopic cracks in the subchondral plate. The fluid mineralized, forming hard, abrasive structures embedded in the hyaline cartilage and extended up to two-thirds of its thickness. The HDMPs were associated with focal fibrillation directly overlying their site. Moreover, isolated fragments of HDMPs were found in the superficial fibrillated area of the hyaline cartilage (see Figure 6). Nano-indentation proved HDMPs to be stiffer and harder than any other phase in bone organs. Initially, it was thought that these structures were disease specific for AKU, but subsequent studies have revealed that they are present in aging and OA human hip joints. They appear to be analogous to calcified structures previously identified in palmar osteochondral disease of the distal third metapodials in trained Thoroughbred racehorses, a model of overload arthrosis,[34] and subsequently in other equine breeds including the Icelandic horses, which are a good model of genetic OA in a large mammal.[35] The protrusions could play a major role in the destruction of cartilage from the subchondral aspect. HDMPs might also be partially responsible for the discordance between pain and cartilage loss in OA. Their formation constitutes a newly recognized mechanism of joint destruction in AKU and in OA and provides potential targets for drug therapy. Furthermore, the ability to detect HDMPs in joint tissues in situ by MRI holds out the prospect that these recently discovered structures might be a useful imaging biomarker of joint disease progression in AKU and OA.

![Figure 5 HDMPs in AKU and non-AKU femoral heads. Upper left panel, MRI slice through the femoral head of a 49-year-old male patient with AKU obtained with an isotropic dual-echo steady-state (DESS) sequence with a resolution of 0.23 mm. Note a region of hypointensity within the hyaline cartilage that corresponds to the position of the HDMPs. Upper right panel, MRI image of a femoral head from an 87-year-old non-AKU male showing a hypointense HDMP (arrow). The lower right and left panels show the HDMPs at higher magnification. The lower central panel shows a 3D micro-computerised tomography (CT) image of HDMPs from the AKU sample (adapted with permission from Boyde et al.[33]). AKU, alkaptonuria; HDMPs, high-density mineralized protrusions.](/document/doi/10.2478/rir-2021-0011/asset/graphic/j_rir-2021-0011_fig_005.jpg)

HDMPs in AKU and non-AKU femoral heads. Upper left panel, MRI slice through the femoral head of a 49-year-old male patient with AKU obtained with an isotropic dual-echo steady-state (DESS) sequence with a resolution of 0.23 mm. Note a region of hypointensity within the hyaline cartilage that corresponds to the position of the HDMPs. Upper right panel, MRI image of a femoral head from an 87-year-old non-AKU male showing a hypointense HDMP (arrow). The lower right and left panels show the HDMPs at higher magnification. The lower central panel shows a 3D micro-computerised tomography (CT) image of HDMPs from the AKU sample (adapted with permission from Boyde et al.[33]). AKU, alkaptonuria; HDMPs, high-density mineralized protrusions.

Formation of high-density mineralized protrusions (HDMPs). (1) Diagram of hyaline articular cartilage (HAC), calcified cartilage (CAC), and underlying subchondral and trabecular bone prior to degeneration. The subchondral plate is intact. (2) Collagen in cartilage becomes pigmented (represented by shading) and stiffened leading to aberrant transmission of mechanical loading (large red arrows). Repetitive loading leads to cracking of the subchondral plate (small red arrows). In addition, dysregulated remodeling of underlying bone leads to focal sclerosis and lysis. (3) Extrusion of mineralizable matrix through the cracks leads to the formation of HDMPs (white). (4) HDMPs are sharp, abrasive, and brittle leading to extensive mechanical destruction of the hyaline cartilage (small white arrows) (adapted with permission from Ref. 17).

Future perspectives

Although nitisinone is a safe and effective therapy for AKU, it can only treat and not cure the disease. Patients receiving nitisinone have to follow a restrictive, low-tyrosine diet and need monitoring to ensure that their circulating tyrosine levels do not become too elevated. The next big step in single-gene diseases like AKU would be to treat the underlying genetic cause with gene replacement therapy.

Knowledge gained from studying AKU might contribute to the development of agents that will specifically target cartilage. No molecules are available yet, and this is a significant factor in the lack of progress in developing diagnostic imaging methods and new therapies. This contrasts starkly with the situation in bone, where the identification of bisphosphonates led to bone scintigraphy and the most successful family of therapeutic agents for bone disease. Could the specificity of HGA for degenerating cartilage be harnessed as carriers of drugs, including enzyme inhibitors and growth factors, to cartilage and as imaging molecules to visualize the degenerating cartilage? Furthermore, resistance to HGA uptake could potentially be used to test the quality of matrix in tissue-engineered cartilages in vitro and as the basis of a high-throughput screen to test chondroprotective agents.

Permissions

The authors declared that permissions has been obtained for figures used in this review article.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

[1] Davison AS, Hughes AT, Milan AM, et al. Alkaptonuria – Many Questions Answered, Further Challenges Beckon. Ann Clin Biochem. 2020;57(2):106–120.10.1177/0004563219879957Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Garrod AE. The Incidence of Alkaptonuria: A Study in Chemical Individuality. 1902 [classical article]. Yale J Biol Med. 2002;75:221–231.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Zatkova A. An Update on Molecular Genetics of Alkaptonuria (AKU). J Inherit Metab Dis. 2011;34:1127–1136.10.1007/s10545-011-9363-zSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Al-Sbou M, Mwafi N, Lubad MA. Identification of Forty Cases with Alkaptonuria in One Village in Jordan. Rheumatol Int. 2012;32:3737–3740.10.1007/s00296-011-2219-xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Goicoechea De Jorge E, Lorda I, Gallardo ME, et al. Alkaptonuria in the Dominican Republic: Identification of the Founder AKU Mutation and Further Evidence of Mutation Hot Spots in the HGO Gene. J Med Genet. 2002;39:E40.10.1136/jmg.39.7.e40Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[6] Phornphutkul C, Introne WJ, Perry MB, et al. Natural History of Alkaptonuria. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:2111–2121.10.1056/NEJMoa021736Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Ranganath LR, Khedr M, Vinjamuri S, et al. Frequency, Diagnosis, Pathogenesis and Management of Osteoporosis in Alkaptonuria: Data Analysis from the UK National Alkaptonuria Centre. Osteoporos Int. 2021;32(5):927–938.10.1007/s00198-020-05671-ySearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Pettit SJ, Fisher M, Gallagher JA, et al. Cardiovascular Manifestations of Alkaptonuria. J Inherit Metab Dis 2011;34:1177–1181.10.1007/s10545-011-9339-zSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Ranganath LR, Norman BP, Gallagher JA. Ochronotic Pigmentation is Caused by Homogentisic Acid and is the Key Event in Alkaptonuria Leading to the Destructive Consequences of the Disease – A Review J Inherit Metab Dis. 2019;42(5):776–792.10.1002/jimd.12152Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Helliwell TR, Gallagher JA, Ranganath L. Alkaptonuria – A Review of Surgical and Autopsy Pathology. Histopathology. 2008;53:503–512.10.1111/j.1365-2559.2008.03000.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Taylor AM, Boyde A, Wilson PJ, et al. The Role of Calcified Cartilage and Subchondral Bone in the Initiation and Progression of Ochronotic Arthropathy in Alkaptonuria. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:3887–3896.10.1002/art.30606Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Tinti L, Taylor AM, Santucci A, et al., Development of an In Vitro Model Toinvestigate Joint Ochronosis in Alkaptonuria. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2011;50(2011):271–277.10.1093/rheumatology/keq246Search in Google Scholar

[13] Taylor AM, Preston AJ, Paulk NK, et al. Ochronosis in A Murine Model of Alkaptonuria is Synonymous to that in the Human Condition. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2012;20:880–886.10.1016/j.joca.2012.04.013Search in Google Scholar

[14] Preston AJ, Keenan CM, Sutherland H, et al. Ochronotic Osteoarthropathy in a Mouse Model of Alkaptonuria, and its Inhibition by Nitisinone. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:284–289.10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202878Search in Google Scholar

[15] Taylor AM, Wlodarski B, Prior IA, et al. Ultrastructural Examination of Tissue in A Patient with Alkaptonuric Arthropathy Reveals A Distinct Pattern of Binding of Ochronotic Pigment. Rheumatology. 2010;49:1412–1414.10.1093/rheumatology/keq027Search in Google Scholar

[16] Scott JE, Haigh M. Proteoglycan-Type I Collagen Fibril Interactions in Bone and Non-Calcifying Connective Tissues. Biosci Rep. 1985;5:71–81.10.1007/BF01117443Search in Google Scholar

[17] Gallagher JA, Dillon JP, Sireau N, et al. Alkaptonuria: An Example of a “Fundamental Disease” – A Rare Disease with Important Lessons for more Common Disorders. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2016;52:53–57.10.1016/j.semcdb.2016.02.020Search in Google Scholar

[18] Chow WY, Taylor AM, Reid DG, et al. Collagen Atomic Scale Molecular Disorder in Ochronotic Cartilage from an Alkaptonuria Patient Observed by Solid State NMR. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2011;34(6):1137–1140.10.1007/s10545-011-9373-xSearch in Google Scholar

[19] Chow WY, Norman BP, Roberts NB, et al. Pigmentation Chemistry and Radical-Based Collagen Degradation in Alkaptonuria and Osteoarthritic Cartilage. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2020;59(29):11937–11942.10.1002/anie.202000618Search in Google Scholar

[20] Montagutelli X, Lalouette A, Coudé M, et al. AKU A Mutation of the Mouse Homologous to Human Alkaptonuria, Maps to Chromosome 16. Genomics. 1994;19:9–11.10.1006/geno.1994.1004Search in Google Scholar

[21] Manning K, Fernandez-Canon JM, Montagutelli X, et al. Identification of the Mutation in the Alkaptonuria Mouse Model. Hum Mutat. 1999;13:171.10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1999)13:2<171::AID-HUMU15>3.0.CO;2-WSearch in Google Scholar

[22] Hughes JH, Keenan CM, Sutherland H, et al. Anatomical Distribution of Ochronotic Pigment in Alkaptonuric Mice is Associated with Calcified Cartilage Chondrocytes at Osteochondral Interfaces. Calcif Tissue Int. 2021;108(2):207–218.10.1007/s00223-020-00764-6Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] Lock EA, Ellis MK, Gaskin P, et al. From toxicological problem to therapeutic use: the discovery of the mode of action of 2-(2-nitro-4-trifluoromethylbenzoyl)-1,3-cyclohexanedione (NTBC), its toxicology and development as a drug. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1998;21:498–506.10.1023/A:1005458703363Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Lindstedt S, Holme E, Lock EA, et al. Treatment of hereditary tyrosinaemia type I by inhibition of 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase. Lancet. 1992;340:813–817.10.1016/0140-6736(92)92685-9Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] McKiernan PJ. Nitisinone for the Treatment of Hereditary Tyrosinemia Type I. Expert Opin Orphan Drugs. 2013;1:491–497.10.1517/21678707.2013.800807Search in Google Scholar

[26] Introne WJ, Perry MB, Troendle J, et al. A 3-Year Randomized Therapeutictrial of Nitisinone in Alkaptonuria. Mol Genet Metab. 2011;103:307–314.10.1016/j.ymgme.2011.04.016Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[27] Keenan CM, Preston AJ, Sutherland H, et al. Nitisinone Arrests But Does not Reverse Ochronosis in Alkaptonuric Mice. JIMD Rep. 2015;24:45–50.10.1007/8904_2015_437Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[28] Ranganath LR, Milan AM, Hughes AT, et al. Suitability of Nitisinone in Alkaptonuria 1 (SONIA 1): An International, Multicentre, Randomised, Open-Label, No-Treatment Controlled, Parallel-Group, Dose-Response Study to Investigate the Effect of Once Daily Nitisinone on 24-h Urinary Homogentisic Acid Excretion in Patients with Alkaptonuria after 4 Weeks of Treatment. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:362–367.10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-206033Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Ranganath LR, Psarelli EE, Arnoux JB. et al Efficacy and Safety of Once-Daily Nitisinone for Patients with Alkaptonuria (SONIA 2): An International, Multicentre, Open-Label, Randomised Controlled Trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8(9):762–777.10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30228-XSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Griffin R, Psarelli EE, Cox TF, et al. Data on Items of AKUSSI in Alkaptonuria Collected Over Three Years from the United Kingdom National Alkaptonuria Centre and the Impact of Nitisinone. Data Brief. 2018;20:1620–1628.10.1016/j.dib.2018.09.021Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[31] Taylor AM, Boyde A, Davidson JS, et al. Identification of Trabecular Excrescences, Novel Microanatomical Structures, Present in Bone in Osteoarthropathies. Eur Cell Mater. 2012;23:300–308; discussion 308–309.10.22203/eCM.v023a23Search in Google Scholar

[32] Keenan CM, Beckett AJ, Sutherland H, et al. Concentric Lamellae – Novel Microanatomical Structures in the Articular Calcified Cartilage of Mice. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):11188.10.1038/s41598-019-47545-2Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] Boyde A, Davis GR, Mills D, et al. On Fragmenting, Densely Mineralised Acellular Protrusions into Articular Cartilage and their Possible Role in Osteoarthritis. J Anat. 2014;225:436–446.10.1111/joa.12226Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[34] Boyde A, Riggs CM, Bushby AJ, McDermott B, Pinchbeck GL, Clegg PD. Cartilage Damage Involving Extrusion of Mineralisable Matrix from the Articular Calcified Cartilage and Subchondral Bone. Eur Cell Mater. 2011;21:470–478; discussion 478.10.22203/eCM.v021a35Search in Google Scholar

[35] Ley CJ, Björnsdóttir S, Ekman S, Boyde A, Hansson K. Detection of Early Osteoarthritis in the Centrodistal Joints of Icelandic Horses: Evaluation of Radiography and Low-Field Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Equine Vet J. 2016;48(1):57–64.10.1111/evj.12370Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2021 James A. Gallagher et al., published by Sciendo

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Guideline

- 2020 Chinese expert-based consensus on the diagnosis and treatment of connective tissue disease associated pulmonary arterial hypertension

- Review

- Development of an effective therapy for alkaptonuria – Lessons for osteoarthritis

- The role of 14-3-3 η as a biomarker in rheumatoid arthritis

- A Darwinian view of Behçet's disease

- Original Article

- Clinical characteristics of adult patients with systemic vasculitis: Data of 1348 patients from a single center

- The emerging challenge of pain in systemic sclerosis: Similarity to the pain experience reported by Sjőgren’s syndrome patients

- Case Report

- Relapsing polychondritis presenting 2 years after systemic sclerosis with pulmonary arterial hypertension

- Images

- “A Bomb in the Chest”—Multiple aortic lesions in a patient with Takayasu’s arteritis

- Letter

- Gout with hearing loss

Articles in the same Issue

- Guideline

- 2020 Chinese expert-based consensus on the diagnosis and treatment of connective tissue disease associated pulmonary arterial hypertension

- Review

- Development of an effective therapy for alkaptonuria – Lessons for osteoarthritis

- The role of 14-3-3 η as a biomarker in rheumatoid arthritis

- A Darwinian view of Behçet's disease

- Original Article

- Clinical characteristics of adult patients with systemic vasculitis: Data of 1348 patients from a single center

- The emerging challenge of pain in systemic sclerosis: Similarity to the pain experience reported by Sjőgren’s syndrome patients

- Case Report

- Relapsing polychondritis presenting 2 years after systemic sclerosis with pulmonary arterial hypertension

- Images

- “A Bomb in the Chest”—Multiple aortic lesions in a patient with Takayasu’s arteritis

- Letter

- Gout with hearing loss