Abstract

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is a devastating disease with an extremely high lethality rate. Oncogenic KRAS activation has been proven to be a key driver of PDAC initiation and progression. There is increasing evidence that PDAC cells undergo extensive metabolic reprogramming to adapt to their extreme energy and biomass demands. Cell-intrinsic factors, such as KRAS mutations, are able to trigger metabolic rewriting. Here, we update recent advances in KRAS-driven metabolic reprogramming and the associated metabolic therapeutic potential in PDAC.

Introduction

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is one of the most lethal cancers, with a 5-year survival rate of 9% in the USA, and is projected to become the second-leading cause of cancer-related death in the near future.[1] Advancements in fundamental and adjuvant chemotherapy have been made in PDAC patients, but only modest incremental progress in patient outcomes has been made. PDAC is a disorder with multiple genetic mutations during multistage progression.[2] The most important genetic event in the development of PDAC is an oncogenic mutation of KRAS (90% in TCGA-PAAD). KRAS is a member of the Rat sarcoma (RAS) family of guanosine triphosphate (GTP)-ases whose activity is regulated by the guanosine diphosphate (GDP)/GTP cycle and is involved in several cellular processes, including survival, proliferation, differentiation, migration, and apoptosis.[3] In contrast to the tight regulation of wild-type protein, mutant KRAS leads to the persistent activation of downstream signaling pathways, such as Raf/MEK/ERK, PI3K/PTEN/AKT, and Ral guanine nucleotide exchange factor (Ral-GEF).[4] Using a mouse disease model, oncogenic KRAS mutations have been proven to initiate acinar-to-ductal metaplasia (ADM) and promote and maintain pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN) lesions.[5] Mutations of KRAS alone do not recapitulate the full spectrum of PDAC development. In addition, the loss of tumor suppressor genes (e.g., tumor protein p53 [TP53]), epigenetic dysregulation (e.g., lysine-specific demethylase 6A [KDM6A], SET Domain Containing 2 [SETD2]), and/or environmental stresses are essential for PDAC malignant transformation and progression.[6]

Tumors are usually accompanied by unique metabolic disorders, which can be regarded as “metabolic diseases”, and many of studies have confirmed that targeting key metabolic pathways can indeed suppress tumor growth.[7] To continuously fulfill biosynthetic demands, tumor cells usually reprogram the glucose metabolism process, which gives priority to glycolysis (the Warburg effect) for energy supply even in an environment with sufficient oxygen.[8] This process is characterized by increased glucose consumption, decreased oxidative phosphorylation, and enhanced lactate synthesis.[9] Lactate in turn promotes angiogenesis and immune cell trafficking in tumors.[10] In addition, the accumulation of reactive oxygen species in proliferating tumor cells leads to DNA damage, and elevated levels of the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) generate more nucleotides and reduce nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) for DNA repair and oxidation resistance.[11] Other metabolites, such as amino acids, fatty acids, and ketone bodies, also participate in tumor metabolism. Moreover, tumor cells can develop autophagy that provides energy in the form of glucose, lactate, amino acids, free fatty acids, and nucleosides for tumor progression, eventually leading to tumor cachexia.[12, 13]

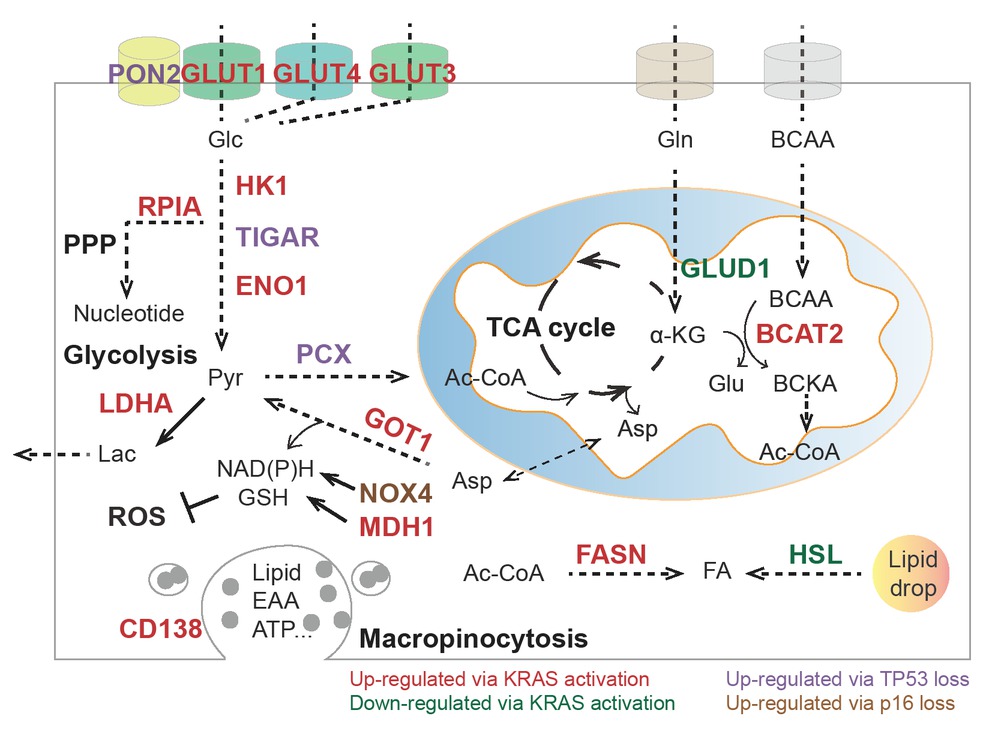

Several studies have shown that tumor cells carry hallmarks of sustained proliferation, enabling replicative immortality, evading growth suppressors, and resisting cell death.[14] To support these extraordinary energetic and biosynthetic demands, tumorigenesis usually accompanies metabolic reprogramming.[14] Early reports have suggested that most tumor cells undergo a metabolic shift toward glycolysis (Warburg effect) to produce energy and toward anabolic pathways to synthesize proteins and lipids, while normal cells mainly depend on oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) in the mitochondria.[15, 16] However, recent reports have begun to uncover the essential role of OXPHOS in tumor cells.[17] Defining how genetic mutations reprogram cellular metabolism has also aroused great interest, which helps us to better understand the intertumoral metabolic heterogeneity and may develop potential targets for cancer therapy. Notably, KRAS mutation-driven metabolic reprogramming in PDAC is the most studied. Here, we summarize the latest studies exploring how KRAS mutation reprograms metabolic processes to enforce PDAC tumorigenesis (Figure 1).

Summary of metabolic pathways and enzymes influenced by KRAS, TP53, and p16. PON2: paraoxonase 2; GLUT1: glucose transporter 1; GLUT3: glucose transporter 3; GLUT4: glucose transporter 4; HK1: hexokinase 1; TIGAR: Trp53-induced glycolysis regulatory phosphatase; ENO1: alpha-enolase; LDHA: lactic dehydrogenase A; RPIA: ribose 5-phosphate isomerase A; Pcx: pyruvate carboxylase function; BCKA: branched-chain α-keto acids; BCAT: branched-chain aminotransferases; GLUD1: glutamate dehydrogenase 1; GOT1: aspartate transaminase; NOX4: NAD(P)H oxidase 4; MDH1: malate dehydrogenase 1; HSL: hormone-sensitive lipase; FASN: fatty acid synthase; Glc: glucose; Lac: lactate; Pyr: pyruvate; Ac-CoA: acetyl-CoA; αKG: α-ketoglutarate; Gln: glutamine; Glu: glutamate; Asp: aspartate; BCAA: branched-chain amino acids; FA: fatty acids; EAA: essential amino acids; NADH: nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; NADPH: nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate; GSH: glutathione; PPP: pentose phosphate pathway; TCA cycle: tricarboxylic acid cycle; ROS: reactive oxygen species.

Glucose metabolism

Oncogenic KRAS activation is closely related to tumor-associated glucose metabolic dysfunction.[18] Accumulating evidence has revealed that murine Kras activation enhances glucose uptake and glycolysis by upregulating the transcriptional level of glucose transporters, including Slc2a1 (encoding Glut1) and Slc2a4 (encoding Glut4), as well as rate-limiting enzymes, including Hk1, Eno1 and Ldha.19, 20, 21, 22 Coherently, the enhanced glycolytic flux caused by oncogenic KRAS can maintain PDAC progression by diverting into anabolic pathways, including the hexosamine biosynthesis pathway (HBP) and nonoxidative PPP, for NADPH production, reactive oxygen species (ROS) detoxification, and nucleotide precursor ribose 5-phosphate synthesis.[20, 23, 24, 25] Mechanistically, sustained KRAS can activate the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway and MYC proto-oncogene (MYC) and hypoxia inducible factor 1 subunit alpha (HIF1α) to transcriptionally regulate transporters and enzymes in glucose metabolism.[20] These metabolic alterations triggered by oncogenic KRAS may confer distinct survival advantages to PDAC under unfavorable microenvironmental conditions.

Moreover, loss of tumor suppressor genes, such as TP53 and cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (CDKN2A or p16), coordinates with oncogenic KRAS mutations to modulate the glycolytic pathway.[19] In a mouse PDAC model, loss of Tp53 further enhances glycolytic flux and energy supply in multiple ways, including elimination of the transcriptional arrest of glucose transporters (e.g., Slc2a1 and Slc2a4) and rate-limiting enzymes (e.g., Pgm, phosphoglycerate mutase) and inhibition of the glycolysis inhibitor Tigar (TP53-induced glycolysis and apoptosis regulator).[26, 27, 28, 29, 30] Loss of Tp53 also transcriptionally increases paraoxonase 2 (Pon2), which facilitates pancreatic cancer growth and metastasis by stimulating Glut1-mediated glucose transport.[19] Notably, Lowe’s group found that restoration of p53 function in Kras and Tp53 mutant-derived PDAC could rewire glucose and glutamine metabolism to favor the accumulation of αKG at the expense of succinate, which triggered chromatin modification 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) to facilitate tumor differentiation and blunt tumor cell fitness.[31] Upon oncogenic activation, further loss of p53 prevents these metabolic effects and enables tumor cells to transition to more aggressive and less differentiated PDAC. Moreover, oncogenic KRAS activation in conjunction with inactivated CDKN2A upregulates the expression of NAD(P)H oxidase 4 (NOX4) to generate nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD)+ and supports glycolysis in human and mouse PDAC cell lines.[32]

Amino acids

Recent studies have suggested that the involvement of amino acids in cancer metabolism is more important than previously thought.[33, 34] The nonessential amino acid glutamine is a common source of carbon and nitrogen for tumor cells.[35, 36] Oncogenic KRAS acts as a converter of glutamine metabolism in PDAC by shifting glutamine metabolism from the TCA cycle to the noncanonical pathway.[37, 38, 39] KRAS activation in human PDAC cells downregulates the glutamate dehydrogenase (GLUD1)-dependent canonical Gln utilization pathway but upregulates aspartate transaminase (GOT1) to maintain redox balance, which contributes to cell proliferation and tumor progression.[40, 41] In addition, KRAS can also preserve glutamine metabolism by protecting MDH1 from CARM1-mediated methylation, which indicates its inactive state.[42] In addition, oncogenic KRAS is able to upregulate the mRNA level of nuclear factor-like 2 (NRF2), which further reprograms glucose and glutamine into anabolic and antioxidant pathways.[38, 43, 44]

In addition to glutamine, tumor progression still relies on the essential branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs), which refer to leucine, isoleucine, and valine. BCAAs can be converted to glutamate and branched-chain α-keto acids (BCKAs) in the cytosol and mitochondria, respectively, by branched-chain aminotransferases (BCATs), to produce energy and nitrogen for biosynthesis.[13, 45] A recent study showed that KRAS stabilized BCAT2 instead of BCAT1 via spleen tyrosine kinase (SYK) and E3 ligase tripartite-motif-containing protein 21 (TRIM21).[46, 47] BCAT2 is markedly elevated in mouse models and human PDAC, and specific deletion of Bcat2 in the murine pancreas largely impedes the early stage of PDAC development. Functionally, BCAT2 enhances BCAA uptake to sustain BCAA catabolism and mitochondrial respiration.[48]

Fatty acids and lipids

In PDAC, obesity and excess fatty acids accelerate tumor growth and metastasis, and lipolysis and lipogenesis processes are indispensable for tumor growth and invasion.[49, 50, 51, 52] During pancreatic cancer progression, several catalyzed enzymes related to de novo fatty acid and cholesterol synthesis are significantly upregulated, including citrate synthase (CS), ATP citrate lyase (ACLY), fatty acid synthase (FASN), and 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase (HMGCR).[53, 54] FASN, the key enzyme that converts sugar metabolism to fatty acids and palmitate, is highly expressed in both human PDAC tissues and spontaneous mouse models and is associated with poor prognosis in PDAC patients.[55] KRAS sensitizes epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling and upregulates FASN expression during PDAC progression.[56, 57] Oncogenic KRAS activation in human PDAC cells also enhances lipid droplet accumulation and attenuates fatty acid oxidation by restraining hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL) levels.[58] Thus, the stored lipid drop will be utilized as an energy supply to promote the invasion process.[58] These findings have revealed novel mechanisms by which KRAS regulates lipid metabolism to favor PDAC metastasis and invasion.[58, 59]

Nucleotide synthesis

In addition to ribose biogenesis influenced by glucose metabolism, oncogenic KRAS can support PDAC proliferation by activating the MAPK-dependent MYC-RPIA axis.[20] Ribose 5-phosphate isomerase A (RPIA) catalyzes the conversion between ribulose-5-phosphate and ribose-5-phosphate in a nonoxidative PPP pathway, which is the dominant mechanism of nucleotide synthesis for PDAC cells.[60]

Macropinocytosis

In addition to the metabolic pathway of single metabolites, tumor cells often develop micropinocytosis, macropinocytosis, and autophagy processes that obtain essential nutrients by engulfing and digesting extracellular matrix or other cells to support their rapid division or proliferation.[18, 61, 62, 63] Autophagy is employed to degrade intracellular components and provide energy, ATP, and metabolites, including amino acids, lipids, sugars, and nucleosides, to promote and/or inhibit tumor progression.[64, 65] In fact, a wide range of studies have shown that enhanced macropinocytosis and subsequent hydrolysis of extracellular proteins in lysosomes become significant features of tumoral KRAS activation in both mouse models and primary human PDAC specimens, which enable tumor cell survival and proliferation in the absence of essential amino acids (EAAs).[66, 67, 68] In terms of mechanism, KRAS expedites CD138 membrane recycling through activation of the MAPK-PSD4-ARF6 axis, which provides another potential therapeutic target worthy of further consideration.[62]

Tumor microenvironment

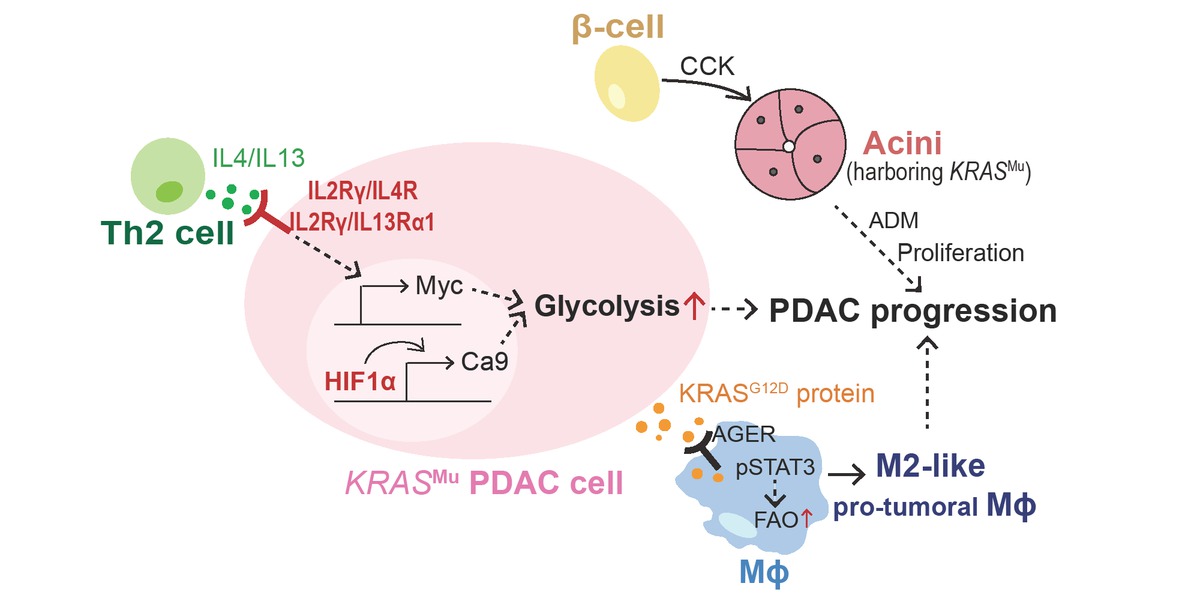

The tumor microenvironment (TME) is a dynamic network that includes malignant cells, immune cells, fibroblasts, and extracellular matrix components and influences the progression of tumors and the therapeutic response (Figure 2). Dey et al.[69] reported that oncogenic KRAS could mediate metabolic reprogramming in PDAC by utilizing cytokines from the TME. Murine Kras mutation in PDAC drives cell-autonomous expression of type I cytokine receptor complexes (IL2rγ-IL4rα and IL2rγ-IL13rα1) that are capable of receiving Th2 cytokines (IL4 or IL13) produced by invading Th2 cells in the TME. The ligand-induced activation of cytokine receptor signals stimulates cancer cell–intrinsic MYC transcriptional upregulation to enhance glycolysis.[69]

Summary of tumor microenvironment driven by oncogenic KRAS. PDAC: pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma; FAO: fatty acid; Mϕ: macrophage; ADM: acinar-to-ductal metaplasia; CCK: cholecystokinin; HIF1α: hypoxia inducible factor 1 subunit alpha; CA9: carbonic anhydrases 9; IL4/IL13: interleukin 4/interleukin 13.

In response to the tumoral hypoxic microenvironment caused by poor vascularization and high interstitial pressure, activated Kras in mouse tumor cells stabilizes Hif1a and Hif2a to increase carbonic anhydrase 9 (Ca9) levels, which next commands the pH value and glycolysis to maintain cell survival.[70] The progression of PDAC is also driven by surrounding endocrine cells in the pancreas.[71] The abnormal expression of cholecystokinin (Cck) in β cells from obese mice promotes oncogenic Kras-driven pancreatic tumorigenesis.[71]

Recently, Tang’s group found that KRASG12D protein could be released from cancer cells succumbing to autophagy-dependent ferroptosis upon oxidative stress. Extracellular KRASG12D protein is then taken up by macrophages via an AGER-dependent mechanism, which drives macrophages to switch to an M2-like protumor phenotype via STAT3-dependent fatty acid oxidation.[72]

Perspectives in early diagnosis

Positron emission tomography (PET) is a nuclear medicine procedure based on the measurement of positron emission from radiolabeled tracer molecules.[73] Given the hallmark of enhanced glucose metabolism in cancer, the most common metabolite-related radiotracer in use today is 18 fluorine-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG), a radiolabeled glucose analog. Imaging with 18F-FDG PET has been widely used to determine the sites of abnormal glucose metabolism and can be used to characterize and localize many types of tumors.[74, 75] Unfortunately, the current 18F-FDG PET imaging has limitations in detecting early-stage or small metastatic lesions of pancreatic cancer.[76, 77, 78, 79, 80] Many efforts have been made toward developing more tumor-specific radiotracers for PET imaging. For example, according to the extreme demand of glutamine for tumor cells, 18F-labeled glutamine analogs are currently being developed and have demonstrated their efficiency in preclinical animal models.[81, 82, 83, 84]

Metabolic reprogramming is an early event in pancreas carcinogenesis initiated by KRAS mutation, suggesting a rationale for the development of related methods for the early diagnosis of PDAC. To develop more selective radiotracers for early diagnosis, intensive studies are required to understand the cellular metabolic changes in the early stages of pancreatic malignant cells and even in precancerous cells (e.g., ADM and PanINs). However, our current understanding of metabolic reprogramming at the early stage of PDAC is based primarily on in vitro cell models and transcriptome or scRNA-seq analyses. Due to technical limitations, it is difficult to measure the metabolome and track metabolites using in vivo models. With technological innovations (e.g., single-cell metabolomics) in the field of metabolic research, more in-depth studies would help us better understand how oncogenic KRAS drives metabolic reprogramming to initiate pancreatic cancer.

Therapeutic opportunities

Oncogenic KRAS mutations are present in the overwhelming majority of patients with PDAC, which makes KRAS naturally the most valuable target. Unfortunately, direct targeting of KRAS has been demonstrated to be ineffective, mainly because the activation and signaling of RAS proteins are primarily accomplished through protein-protein interactions. Such interfaces have traditionally been difficult to target with small molecules due to their lack of well-defined binding pockets.[85, 86] Recent efforts have led to the development of pharmacological inhibitors targeting the KRASG12C mutant, which have shown promising results in early clinical trials.[87,88] However, targeting KRASG12D remains a major challenge. Therefore, there is an urgent need for therapeutics targeting KRASG12D mutants, especially for PDAC. Unfortunately, targeting downstream effectors of oncogenic KRAS, such as the RAF-MEK-ERK pathway and PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway, has been demonstrated to be ineffective.[86, 89, 90, 91, 92] Up to now, several targeted therapies against the mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MEK), extracellular-signal regulated kinase (ERK), phosphoinositide 3-kinases (PI3Ks), and mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathways have been demonstrated to be effective in impeding cell proliferation and tumor progression in human PDAC cell lines and mouse models. However, none of these has any impact on survival benefits according to clinical trials.[92, 93, 94, 95]

Recently, metabolic enzyme inhibitors have received increasing attention for their therapeutic potential. Of note, inhibitors targeting isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) mutations have been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia carrying IDH2 and IDH1 mutations, representing the first breakthrough in the translational research of tumor metabolism.[96, 97] In addition, metabolic targets such as glucose transporter protein type 1 (GLUT1), lactate dehydrogenase-A (LDHA), and glutaminase (GLS) have also shown antitumor effects in other tumors, such as breast cancer and ovarian cancer.[98, 99, 100, 101]

The novel insights into the metabolic alterations associated with KRAS mutations provide exciting possibilities for targeting these poor-prognosis cancers. Many metabolic inhibitors have shown significant inhibitory effects on PDAC in preclinical culture and animal models; however, none has been approved for patients with PDAC.[102, 103, 104, 105] Herein, according to the results of existing clinical trials, as well as drug efficacy and resistance issues, this field needs more in-depth exploration in the future.

Conclusion

Here, we summarized and highlighted recent advances in understanding how oncogenic KRAS mutations reprogram cellular metabolism in PDAC. Oncogenic KRAS activation alters glucose uptake, glycolytic flux, glutamine usage, nucleotide synthesis, lipolysis, and lipogenesis processes in PDAC to meet specific demands for energy metabolites during PDAC rapid progression. Moreover, to adapt to the scarcity or imbalance of nutrient availability, oncogenic KRAS is also able to activate metabolic scavenging pathways, such as autophagy and macropinocytosis. Elucidating the role of oncogenic KRAS in metabolic reprogramming provides novel therapeutic interventions for PDAC.

Funding statement: This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82022049, Xue J; No. 82073105, Niu N), Shanghai Rising-Star Program (19QA1408300, Niu N), the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (20ZR1432900, Niu N), Shanghai Municipal Education Commission-Gaofeng Clinical Medicine Grant Support (No. 20161312, Xue J), and State Key Laboratory of Oncogenes and Related Genes (KF2113, Niu N).

-

Conflicts of Interest

None declared.

References

1 Vincent A, Herman J, Schulick R, Hruban RH, Goggins M. Pancreatic cancer. Lancet 2011;378:607-20.10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62307-0Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

2 Hruban RH, Fukushima N. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma: update on the surgical pathology of carcinomas of ductal origin and PanINs. Mod Pathol 2007;20 Suppl 1:S61-70.10.1038/modpathol.3800685Search in Google Scholar PubMed

3 Castellano E, Santos E. Functional specificity of ras isoforms: so similar but so different. Genes Cancer 2011;2:216-31.10.1177/1947601911408081Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

4 Morris JPt, Wang SC, Hebrok M. KRAS, Hedgehog, Wnt and the twisted developmental biology of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Nat Rev Cancer 2010;10:683-95.10.1038/nrc2899Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

5 Niu N, Lu P, Yang Y, He R, Zhang L, Shi J, et al. Loss of Setd2 promotes Kras-induced acinar-to-ductal metaplasia and epithelia-mesenchymal transition during pancreatic carcinogenesis. Gut 2020;69:715-26.10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318362Search in Google Scholar PubMed

6 Buscail L, Bournet B, Cordelier P. Role of oncogenic KRAS in the diagnosis, prognosis and treatment of pancreatic cancer. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020;17:153-68.10.1038/s41575-019-0245-4Search in Google Scholar PubMed

7 Encarnacion-Rosado J, Kimmelman AC. Harnessing metabolic dependencies in pancreatic cancers. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;18:482-92.10.1038/s41575-021-00431-7Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

8 Gogvadze V, Zhivotovsky B, Orrenius S. The Warburg effect and mitochondrial stability in cancer cells. Mol Aspects Med 2010;31:60-74.10.1016/j.mam.2009.12.004Search in Google Scholar PubMed

9 Reina-Campos M, Moscat J, Diaz-Meco M. Metabolism shapes the tumor microenvironment. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2017;48:47-53.10.1016/j.ceb.2017.05.006Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

10 Altman BJ, Stine ZE, Dang CV. From Krebs to clinic: glutamine metabolism to cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer 2016;16:619-34.10.1038/nrc.2016.71Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

11 Levine A. J. P-KAM. The Control of the Metabolic Switch in Cancers by Oncogenes and Tumor Suppressor Genes. Science 2010;330:1340-4.10.1126/science.1193494Search in Google Scholar PubMed

12 MacVicar T, Ohba Y, Nolte H, Mayer FC, Tatsuta T, Sprenger HG, et al. Lipid signalling drives proteolytic rewiring of mitochondria by YME1L. Nature 2019;575:361-5.10.1038/s41586-019-1738-6Search in Google Scholar PubMed

13 Mayers JRea. Tissue of origin dictates branched-chain amino acid metabolism in mutant Kras-driven cancers. Science 2016;353:607-20.10.1126/science.aaf5171Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

14 Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. cell. 2011;144:646-74.10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013Search in Google Scholar PubMed

15 Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC, Thompson CB. Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science 2009;324:1029-33.10.1126/science.1160809Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

16 Koppenol WH, Bounds PL, Dang CV. Otto Warburg’s contributions to current concepts of cancer metabolism. Nat Rev Cancer 2011;11:325-37.10.1038/nrc3038Search in Google Scholar PubMed

17 Ashton TM, McKenna WG, Kunz-Schughart LA, Higgins GS. Oxidative Phosphorylation as an Emerging Target in Cancer Therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24:2482-90.10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-3070Search in Google Scholar PubMed

18 Kimmelman AC. Metabolic Dependencies in RAS-Driven Cancers. Clin Cancer Res 2015;21:1828-34.10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2425Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

19 Nagarajan A, Dogra SK, Sun L, Gandotra N, Ho T, Cai G, et al. Paraoxonase 2 Facilitates Pancreatic Cancer Growth and Metastasis by Stimulating GLUT1-Mediated Glucose Transport. Mol Cell 2017;67:685-701.e6.10.1016/j.molcel.2017.07.014Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

20 Ying H, Kimmelman AC, Lyssiotis CA, Hua S, Chu GC, Fletcher-Sananikone E, et al. Oncogenic Kras maintains pancreatic tumors through regulation of anabolic glucose metabolism. Cell 2012;149:656-70.10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.058Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

21 Li C, Zhao Z, Zhou Z, Liu R. PKM2 Promotes Cell Survival and Invasion Under Metabolic Stress by Enhancing Warburg Effect in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Dig Dis Sci 2016;61:767-73.10.1007/s10620-015-3931-2Search in Google Scholar PubMed

22 Deer EL, Gonzalez-Hernandez J, Coursen JD, Shea JE, Ngatia J, Scaife CL, et al. Phenotype and genotype of pancreatic cancer cell lines. Pancreas 2010;39:425-35.10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181c15963Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

23 Lin R, Elf S, Shan C, Kang HB, Ji Q, Zhou L, et al. 6-Phosphogluconate dehydrogenase links oxidative PPP, lipogenesis and tumour growth by inhibiting LKB1-AMPK signalling. Nat Cell Biol 2015;17:1484-96.10.1038/ncb3255Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

24 Stincone A, Prigione A, Cramer T, Wamelink MM, Campbell K, Cheung E, et al. The return of metabolism: biochemistry and physiology of the pentose phosphate pathway. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc 2015;90:927-63.10.1111/brv.12140Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

25 Patra KC, Hay N. The pentose phosphate pathway and cancer. Trends Biochem Sci 2014;39:347-54.10.1016/j.tibs.2014.06.005Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

26 Shen L, Sun X, Fu Z, Yang G, Li J, Yao L. The fundamental role of the p53 pathway in tumor metabolism and its implication in tumor therapy. Clin Cancer Res 2012;18:1561-7.10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-3040Search in Google Scholar PubMed

27 Escobar-Hoyos LF, Penson A, Kannan R, Cho H, Pan CH, Singh RK, et al. Altered RNA Splicing by Mutant p53 Activates Oncogenic RAS Signaling in Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Cell 2020;38:198-211.e8.10.1016/j.ccell.2020.05.010Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

28 Morton JP, Timpson P, Karim SA, Ridgway RA, Athineos D, Doyle B, et al. Mutant p53 drives metastasis and overcomes growth arrest/senescence in pancreatic cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010;107:246-51.10.1073/pnas.0908428107Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

29 Wormann SM, Song L, Ai J, Diakopoulos KN, Kurkowski MU, Gorgulu K, et al. Loss of P53 Function Activates JAK2-STAT3 Signaling to Promote Pancreatic Tumor Growth, Stroma Modification, and Gemcitabine Resistance in Mice and Is Associated With Patient Survival. Gastroenterology 2016;151:180-93.e12.10.1053/j.gastro.2016.03.010Search in Google Scholar PubMed

30 Schwartzenberg-Bar-Yoseph F, Armoni, M. & Karnieli, E. The tumor suppressor p53 down-regulates glucose transporters GLUT1 and GLUT4 gene expression. Cancer Res 2004;64:2627–33.10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-0846Search in Google Scholar

31 Morris JPt, Yashinskie JJ, Koche R, Chandwani R, Tian S, Chen CC, et al. alpha-Ketoglutarate links p53 to cell fate during tumour suppression. Nature 2019;573:595-9.10.1038/s41586-019-1577-5Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

32 Ju HQ, Ying H, Tian T, Ling J, Fu J, Lu Y, et al. Mutant Kras- and p16-regulated NOX4 activation overcomes metabolic checkpoints in development of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Nat Commun 2017;8:14437.10.1038/ncomms14437Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

33 Bertero T, Oldham WM, Grasset EM, Bourget I, Boulter E, Pisano S, et al. Tumor-Stroma Mechanics Coordinate Amino Acid Availability to Sustain Tumor Growth and Malignancy. Cell Metab 2019;29:124-40 e10.10.1016/j.cmet.2018.09.012Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

34 Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Peiris-Pages M, Pestell RG, Sotgia F, Lisanti MP. Cancer metabolism: a therapeutic perspective. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2017;14:11-31.10.1038/nrclinonc.2016.60Search in Google Scholar PubMed

35 Sivanand S, Vander Heiden MG. Emerging Roles for Branched-Chain Amino Acid Metabolism in Cancer. Cancer Cell 2020;37:147-56.10.1016/j.ccell.2019.12.011Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

36 Yang M, Vousden KH. Serine and one-carbon metabolism in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2016;16:650-62.10.1038/nrc.2016.81Search in Google Scholar PubMed

37 Gwinn DM, Lee AG, Briones-Martin-Del-Campo M, Conn CS, Simpson DR, Scott AI, et al. Oncogenic KRAS Regulates Amino Acid Homeostasis and Asparagine Biosynthesis via ATF4 and Alters Sensitivity to L-Asparaginase. Cancer Cell 2018;33:91-107.e6.10.1016/j.ccell.2017.12.003Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

38 Mitsuishi Y, Taguchi K, Kawatani Y, Shibata T, Nukiwa T, Aburatani H, et al. Nrf2 redirects glucose and glutamine into anabolic pathways in metabolic reprogramming. Cancer Cell 2012;22:66-79.10.1016/j.ccr.2012.05.016Search in Google Scholar PubMed

39 DeBerardinis RJ, Lum JJ, Hatzivassiliou G, Thompson CB. The biology of cancer: metabolic reprogramming fuels cell growth and proliferation. Cell Metab 2008;7:11-20.10.1016/j.cmet.2007.10.002Search in Google Scholar PubMed

40 Son J, Lyssiotis CA, Ying H, Wang X, Hua S, Ligorio M, et al. Glutamine supports pancreatic cancer growth through a KRAS-regulated metabolic pathway. Nature 2013;496:101-5.10.1038/nature12040Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

41 Lyssiotis CA, Son J, Cantley LC, Kimmelman AC. Pancreatic cancers rely on a novel glutamine metabolism pathway to maintain redox balance. Cell Cycle 2013;12:1987-8.10.4161/cc.25307Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

42 Wang YP, Zhou W, Wang J, Huang X, Zuo Y, Wang TS, et al. Arginine Methylation of MDH1 by CARM1 Inhibits Glutamine Metabolism and Suppresses Pancreatic Cancer. Mol Cell 2016;64:673-87.10.1016/j.molcel.2016.09.028Search in Google Scholar PubMed

43 DeNicola GM, Karreth FA, Humpton TJ, Gopinathan A, Wei C, Frese K, et al. Oncogene-induced Nrf2 transcription promotes ROS detoxification and tumorigenesis. Nature 2011;475:106-9.10.1038/nature10189Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

44 DeNicola GM, Chen PH, Mullarky E, Sudderth JA, Hu Z, Wu D, et al. NRF2 regulates serine biosynthesis in non-small cell lung cancer. Nat Genet 2015;47:1475-81.10.1038/ng.3421Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

45 Ananieva EA, Powell JD, Hutson SM. Leucine Metabolism in T Cell Activation: mTOR Signaling and Beyond. Adv Nutr 2016;7:798S-805S.10.3945/an.115.011221Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

46 Li JT, Yin M, Wang D, Wang J, Lei MZ, Zhang Y, et al. BCAT2-mediated BCAA catabolism is critical for development of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Nat Cell Biol 2020;22:167-74.10.1038/s41556-019-0455-6Search in Google Scholar PubMed

47 Rak J. The KRAS-BCAA-BCAT2 axis in PDAC development. Nat Cell Biol 2020;22:137-9.10.1038/s41556-020-0466-3Search in Google Scholar PubMed

48 Lei MZ, Li XX, Zhang Y, Li JT, Zhang F, Wang YP, et al. Acetylation promotes BCAT2 degradation to suppress BCAA catabolism and pancreatic cancer growth. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2020;5:70.10.1038/s41392-020-0168-0Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

49 Snaebjornsson MT, Janaki-Raman S, Schulze A. Greasing the Wheels of the Cancer Machine: The Role of Lipid Metabolism in Cancer. Cell Metab 2020;31:62-76.10.1016/j.cmet.2019.11.010Search in Google Scholar PubMed

50 Vriens K, Christen S, Parik S, Broekaert D, Yoshinaga K, Talebi A, et al. Evidence for an alternative fatty acid desaturation pathway increasing cancer plasticity. Nature 2019;566:403-6.10.1038/s41586-019-0904-1Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

51 Rohrig F, Schulze A. The multifaceted roles of fatty acid synthesis in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16:732-49.10.1038/nrc.2016.89Search in Google Scholar PubMed

52 Currie E, Schulze A, Zechner R, Walther TC, Farese RV, Jr. Cellular fatty acid metabolism and cancer. Cell Metab 2013;18:153-61.10.1016/j.cmet.2013.05.017Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

53 Bensaad K, Favaro E, Lewis CA, Peck B, Lord S, Collins JM, et al. Fatty acid uptake and lipid storage induced by HIF-1alpha contribute to cell growth and survival after hypoxia-reoxygenation. Cell Rep 2014;9:349-65.10.1016/j.celrep.2014.08.056Search in Google Scholar PubMed

54 Bulusu V, Tumanov S, Michalopoulou E, van den Broek NJ, MacKay G, Nixon C, et al. Acetate Recapturing by Nuclear Acetyl-CoA Synthetase 2 Prevents Loss of Histone Acetylation during Oxygen and Serum Limitation. Cell Rep 2017;18:647-58.10.1016/j.celrep.2016.12.055Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

55 Tadros S, Shukla SK, King RJ, Gunda V, Vernucci E, Abrego J, et al. De Novo Lipid Synthesis Facilitates Gemcitabine Resistance through Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Res 2017;77:5503-17.10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-3062Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

56 Navas C, Hernandez-Porras I, Schuhmacher AJ, Sibilia M, Guerra C, Barbacid M. EGF receptor signaling is essential for k-ras oncogene-driven pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell 2012;22:318-30.10.1016/j.ccr.2012.08.001Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

57 Bian Y, Yu Y, Wang S, Li L. Up-regulation of fatty acid synthase induced by EGFR/ERK activation promotes tumor growth in pancreatic cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2015;463:612-7.10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.05.108Search in Google Scholar PubMed

58 Rozeveld CN, Johnson KM, Zhang L, Razidlo GL. KRAS Controls Pancreatic Cancer Cell Lipid Metabolism and Invasive Potential through the Lipase HSL. Cancer Res 2020;80:4932-45.10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-20-1255Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

59 Chen M, Huang J. The expanded role of fatty acid metabolism in cancer: new aspects and targets. Precis Clin Med 2019;2:183-91.10.1093/pcmedi/pbz017Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

60 Santana-Codina N, Roeth AA, Zhang Y, Yang A, Mashadova O, Asara JM, et al. Oncogenic KRAS supports pancreatic cancer through regulation of nucleotide synthesis. Nat Commun 2018;9:4945.10.1038/s41467-018-07472-8Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

61 Commisso C, Davidson SM, Soydaner-Azeloglu RG, Parker SJ, Kamphorst JJ, Hackett S, et al. Macropinocytosis of protein is an amino acid supply route in Ras-transformed cells. Nature 2013;497:633-7.10.1038/nature12138Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

62 Yao W, Rose JL, Wang W, Seth S, Jiang H, Taguchi A, et al. Syndecan 1 is a critical mediator of macropinocytosis in pancreatic cancer. Nature 2019;568:410-4.10.1038/s41586-019-1062-1Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

63 Yang S, Wang X, Contino G, Liesa M, Sahin E, Ying H, et al. Pancreatic cancers require autophagy for tumor growth. Genes Dev 2011;25:717-29.10.1101/gad.2016111Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

64 Kang R, Zhang Q, Zeh HJ, 3rd, Lotze MT, Tang D. HMGB1 in cancer: good, bad, or both? Clin Cancer Res 2013;19:4046-57.10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0495Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

65 Rabinowitz JD, White E. Autophagy and metabolism. Science 2010;330:1344-8.10.1126/science.1193497Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

66 Kamphorst JJ, Nofal M, Commisso C, Hackett SR, Lu W, Grabocka E, et al. Human pancreatic cancer tumors are nutrient poor and tumor cells actively scavenge extracellular protein. Cancer Res 2015;75:544-53.10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-2211Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

67 Palm W, Park Y, Wright K, Pavlova NN, Tuveson DA, Thompson CB. The Utilization of Extracellular Proteins as Nutrients Is Suppressed by mTORC1. Cell 2015;162:259-70.10.1016/j.cell.2015.06.017Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

68 Davidson SM, Jonas O, Keibler MA, Hou HW, Luengo A, Mayers JR, et al. Direct evidence for cancer-cell-autonomous extracellular protein catabolism in pancreatic tumors. Nat Med 2017;23:235-41.10.1038/nm.4256Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

69 Dey P, Li J, Zhang J, Chaurasiya S, Strom A, Wang H, et al. Oncogenic KRAS-Driven Metabolic Reprogramming in Pancreatic Cancer Cells Utilizes Cytokines from the Tumor Microenvironment. Cancer Discov 2020;10:608-25.10.1158/2159-8290.CD-19-0297Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

70 McDonald PC, Chafe SC, Brown WS, Saberi S, Swayampakula M, Venkateswaran G, et al. Regulation of pH by Carbonic Anhydrase 9 Mediates Survival of Pancreatic Cancer Cells With Activated KRAS in Response to Hypoxia. Gastroenterology 2019;157:823-37.10.1053/j.gastro.2019.05.004Search in Google Scholar PubMed

71 Chung KM, Singh J, Lawres L, Dorans KJ, Garcia C, Burkhardt DB, et al. Endocrine-Exocrine Signaling Drives Obesity-Associated Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Cell 2020;181:832-47.e18.10.1016/j.cell.2020.03.062Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

72 Dai E, Han L, Liu J, Xie Y, Kroemer G, Klionsky DJ, et al. Autophagy-dependent ferroptosis drives tumor-associated macrophage polarization via release and uptake of oncogenic KRAS protein. Autophagy 2020;16:2069-83.10.1080/15548627.2020.1714209Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

73 Sridhar P, Mercier G, Tan J, Truong MT, Daly B, Subramaniam RM. FDG PET metabolic tumor volume segmentation and pathologic volume of primary human solid tumors. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2014;202:1114-9.10.2214/AJR.13.11456Search in Google Scholar PubMed

74 Friess H, Langhans J, Ebert M, Beger HG, Stollfuss J, Reske SN, et al. Diagnosis of pancreatic cancer by 2[18F]-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography. Gut 1995;36:771-7.10.1136/gut.36.5.771Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

75 Zimny M, Bares R, Fass J, Adam G, Cremerius U, Dohmen B, et al. Fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in the differential diagnosis of pancreatic carcinoma: a report of 106 cases. Eur J Nucl Med 1997;24:678-82.10.1007/BF00841409Search in Google Scholar PubMed

76 Chen BB, Tien YW, Chang MC, Cheng MF, Chang YT, Wu CH, et al. PET/MRI in pancreatic and periampullary cancer: correlating diffusion-weighted imaging, MR spectroscopy and glucose metabolic activity with clinical stage and prognosis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2016;43:1753-64.10.1007/s00259-016-3356-ySearch in Google Scholar PubMed

77 Yamamoto T, Sugiura T, Mizuno T, Okamura Y, Aramaki T, Endo M, et al. Preoperative FDG-PET predicts early recurrence and a poor prognosis after resection of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol 2015;22:677-84.10.1245/s10434-014-4046-2Search in Google Scholar PubMed

78 Lee JW, Kang CM, Choi HJ, Lee WJ, Song SY, Lee JH, et al. Prognostic Value of Metabolic Tumor Volume and Total Lesion Glycolysis on Preoperative (1)(8)F-FDG PET/CT in Patients with Pancreatic Cancer. J Nucl Med 2014;55:898-904.10.2967/jnumed.113.131847Search in Google Scholar PubMed

79 Matsumoto I, Shirakawa S, Shinzeki M, Asari S, Goto T, Ajiki T, et al. 18-Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography does not aid in diagnosis of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013;11:712-8.10.1016/j.cgh.2012.12.033Search in Google Scholar PubMed

80 Rijkers AP, Valkema R, Duivenvoorden HJ, van Eijck CH. Usefulness of F-18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography to confirm suspected pancreatic cancer: a meta-analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol 2014;40:794-804.10.1016/j.ejso.2014.03.016Search in Google Scholar PubMed

81 Wu Z, Zha Z, Li G, Lieberman BP, Choi SR, Ploessl K, et al. [(18)F] (2S,4S)-4-(3-Fluoropropyl)glutamine as a tumor imaging agent. Mol Pharm 2014;11:3852-66.10.1021/mp500236ySearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

82 Lieberman BP, Ploessl K, Wang L, Qu W, Zha Z, Wise DR, et al. PET imaging of glutaminolysis in tumors by 18F-(2S,4R)4-fluoroglutamine. J Nucl Med 2011;52:1947-55.10.2967/jnumed.111.093815Search in Google Scholar PubMed

83 Ploessl K, Wang L, Lieberman BP, Qu W, Kung HF. Comparative evaluation of 18F-labeled glutamic acid and glutamine as tumor metabolic imaging agents. J Nucl Med 2012;53:1616-24.10.2967/jnumed.111.101279Search in Google Scholar PubMed

84 Venneti S, Dunphy MP, Zhang H, Pitter KL, Zanzonico P, Campos C, et al. Glutamine-based PET imaging facilitates enhanced metabolic evaluation of gliomas in vivo. Sci Transl Med 2015;7:274ra17.10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa1009Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

85 Sun Q, Burke JP, Phan J, Burns MC, Olejniczak ET, Waterson AG, et al. Discovery of small molecules that bind to K-Ras and inhibit Sos-mediated activation. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2012;51:6140-3.10.1002/anie.201201358Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

86 Zeitouni D, Pylayeva-Gupta Y, Der CJ, Bryant KL. KRAS Mutant Pancreatic Cancer: No Lone Path to an Effective Treatment. Cancers (Basel) 2016;8:45.10.3390/cancers8040045Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

87 Canon J, Rex K, Saiki AY, Mohr C, Cooke K, Bagal D, et al. The clinical KRAS(G12C) inhibitor AMG 510 drives anti-tumour immunity. Nature 2019;575:217-23.10.1038/s41586-019-1694-1Search in Google Scholar PubMed

88 Hong DS, Fakih MG, Strickler JH, Desai J, Durm GA, Shapiro GI, et al. KRAS(G12C) Inhibition with Sotorasib in Advanced Solid Tumors. N Engl J Med 2020;383:1207-17.10.1056/NEJMoa1917239Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

89 Hatzivassiliou G, Song K, Yen I, Brandhuber BJ, Anderson DJ, Alvarado R, et al. RAF inhibitors prime wild-type RAF to activate the MAPK pathway and enhance growth. Nature 2010;464:431-5.10.1038/nature08833Search in Google Scholar PubMed

90 Heidorn SJ, Milagre C, Whittaker S, Nourry A, Niculescu-Duvas I, Dhomen N, et al. Kinase-dead BRAF and oncogenic RAS cooperate to drive tumor progression through CRAF. Cell 2010;140:209-21.10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.040Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

91 Poulikakos PI, Zhang C, Bollag G, Shokat KM, Rosen N. RAF inhibitors transactivate RAF dimers and ERK signalling in cells with wild-type BRAF. Nature 2010;464:427-30.10.1038/nature08902Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

92 Awasthi N, Kronenberger D, Stefaniak A, Hassan MS, von Holzen U, Schwarz MA, et al. Dual inhibition of the PI3K and MAPK pathways enhances nab-paclitaxel/gemcitabine chemotherapy response in preclinical models of pancreatic cancer. Cancer Lett 2019;459:41-9.10.1016/j.canlet.2019.05.037Search in Google Scholar PubMed

93 Ning C, Liang M, Liu S, Wang G, Edwards H, Xia Y, et al. Targeting ERK enhances the cytotoxic effect of the novel PI3K and mTOR dual inhibitor VS-5584 in preclinical models of pancreatic cancer. Oncotarget 2017;8:44295–311.10.18632/oncotarget.17869Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

94 Burmi RS, Maginn EN, Gabra H, Stronach EA, Wasan HS. Combined inhibition of the PI3K/mTOR/MEK pathway induces Bim/Mcl-1-regulated apoptosis in pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Biol Ther 2019;20:21-30.10.1080/15384047.2018.1504718Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

95 Van Cutsem E, van de Velde H, Karasek P, Oettle H, Vervenne WL, Szawlowski A, et al. Phase III trial of gemcitabine plus tipifarnib compared with gemcitabine plus placebo in advanced pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:1430-8.10.1200/JCO.2004.10.112Search in Google Scholar PubMed

96 Mullard A. FDA approves first-in-class cancer metabolism drug. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2017;16:593.10.1038/nrd.2017.174Search in Google Scholar PubMed

97 Mullard A. Cancer metabolism pipeline breaks new ground. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2016;15:735-7.10.1038/nrd.2016.223Search in Google Scholar PubMed

98 Ma Y, Wang W, Idowu MO, Oh U, Wang XY, Temkin SM, et al. Ovarian Cancer Relies on Glucose Transporter 1 to Fuel Glycolysis and Growth: Anti-Tumor Activity of BAY-876. Cancers (Basel) 2018;11:33.10.3390/cancers11010033Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

99 Boudreau A, Purkey HE, Hitz A, Robarge K, Peterson D, Labadie S, et al. Metabolic plasticity underpins innate and acquired resistance to LDHA inhibition. Nat Chem Biol 2016;12:779-86.10.1038/nchembio.2143Search in Google Scholar PubMed

100 Gross MI, Demo SD, Dennison JB, Chen L, Chernov-Rogan T, Goyal B, et al. Antitumor activity of the glutaminase inhibitor CB-839 in triple-negative breast cancer. Mol Cancer Ther 2014;13:890-901.10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0870Search in Google Scholar PubMed

101 Varghese S, Pramanik S, Williams LJ, Hodges HR, Hudgens CW, Fischer GM, et al. The Glutaminase Inhibitor CB-839 (Telaglenastat) Enhances the Antimelanoma Activity of T-Cell-Mediated Immunotherapies. Mol Cancer Ther 2021;20:500-11.10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-20-0430Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

102 Bulle A, Dekervel J, Deschuttere L, Nittner D, Van Cutsem E, Verslype C, et al. Anti-Cancer Activity of Acriflavine as Metabolic Inhibitor of OXPHOS in Pancreas Cancer Xenografts. Onco Targets Ther 2020;13:6907-16.10.2147/OTT.S245134Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

103 Wen CL, Huang K, Jiang LL, Lu XX, Dai YT, Shi MM, et al. An allosteric PGAM1 inhibitor effectively suppresses pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019;116:23264-73.10.1073/pnas.1914557116Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

104 Daemen A, Peterson D, Sahu N, McCord R, Du X, Liu B, et al. Metabolite profiling stratifies pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas into subtypes with distinct sensitivities to metabolic inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci US A 2015;112:E4410-7.10.1073/pnas.1501605112Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

105 Ding L, Madamsetty VS, Kiers S, Alekhina O, Ugolkov A, Dube J, et al .Glycogen Synthase Kinase-3 Inhibition Sensitizes Pancreatic Cancer Cells to Chemotherapy by Abrogating the TopBP1/ATR-Mediated DNA Damage Response. Clin Cancer Res 2019;25:6452-62.10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-0799Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2023 Xuqing Shen, Ningning Niu, Jing Xue, published by De Gruyter on behalf of Scholar Media Publishing

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Perspective

- Mucus hypersecretion in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: From molecular mechanisms to treatment

- Timing of TIPS for the management of portal vein thrombosis in liver cirrhosis

- Commentary

- Could unpublishing negative results be harmful to the general public?

- Review Article

- Oncogenic KRAS triggers metabolic reprogramming in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

- Mitochondrial damage-associated molecular patterns in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Pathogenetic mechanism and therapeutic target

- Exosomes and their derivatives as biomarkers and therapeutic delivery agents for cardiovascular diseases: Situations and challenges

- Autophagy-dependent ferroptosis in infectious disease

- Impact of gut microbiota and associated mechanisms on postprandial glucose levels in patients with diabetes

- Circular RNA: A promising new star of vaccine

- Crosstalk between gut microbiota and gut resident macrophages in inflammatory bowel disease

- Original Article

- Hypervolemia suppresses dilutional anaemic injury in a rat model of haemodilution

- Prognostic value of serum ammonia in critical patients with non-hepatic disease: A prospective, observational, multicenter study

- Global lineage evolution pattern of sars-cov-2 in Africa, America, Europe, and Asia: A comparative analysis of variant clusters and their relevance across continents

- Efficacy and safety of QL0911 in adult patients with chronic primary immune thrombocytopenia: A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial

- A pan-cancer analysis of the oncogenic role of Golgi transport 1B in human tumors

- Short-term duration of diabetic retinopathy as a predictor for development of diabetic kidney disease

- Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging-derived septum swing index detects pulmonary hypertension: A diagnostic study

- Letter to Editor

- Temporal trend of acute myocardial infarction-related mortality and associated racial/ethnic disparities during the omicron outbreak

Articles in the same Issue

- Perspective

- Mucus hypersecretion in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: From molecular mechanisms to treatment

- Timing of TIPS for the management of portal vein thrombosis in liver cirrhosis

- Commentary

- Could unpublishing negative results be harmful to the general public?

- Review Article

- Oncogenic KRAS triggers metabolic reprogramming in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

- Mitochondrial damage-associated molecular patterns in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Pathogenetic mechanism and therapeutic target

- Exosomes and their derivatives as biomarkers and therapeutic delivery agents for cardiovascular diseases: Situations and challenges

- Autophagy-dependent ferroptosis in infectious disease

- Impact of gut microbiota and associated mechanisms on postprandial glucose levels in patients with diabetes

- Circular RNA: A promising new star of vaccine

- Crosstalk between gut microbiota and gut resident macrophages in inflammatory bowel disease

- Original Article

- Hypervolemia suppresses dilutional anaemic injury in a rat model of haemodilution

- Prognostic value of serum ammonia in critical patients with non-hepatic disease: A prospective, observational, multicenter study

- Global lineage evolution pattern of sars-cov-2 in Africa, America, Europe, and Asia: A comparative analysis of variant clusters and their relevance across continents

- Efficacy and safety of QL0911 in adult patients with chronic primary immune thrombocytopenia: A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial

- A pan-cancer analysis of the oncogenic role of Golgi transport 1B in human tumors

- Short-term duration of diabetic retinopathy as a predictor for development of diabetic kidney disease

- Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging-derived septum swing index detects pulmonary hypertension: A diagnostic study

- Letter to Editor

- Temporal trend of acute myocardial infarction-related mortality and associated racial/ethnic disparities during the omicron outbreak