Abstract

Background and Objectives

Weight reduction has evidenced benefit on attenuation of histological activity and fibrosis of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), but there is scarcity of data for lean NASH subgroup. We have designed this study to compare the effects of weight reduction on histological activity and fibrosis of lean and non-lean NASH.

Methods

We have included 20 lean and 20 non-lean histologically proven NASH patients. BMI < 25 kg/m2 was defined as non-lean. Informed consent was taken from each subject. All methods were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Moderate exercise along with dietary restriction was advised for both groups for weight reduction. After 1 year, 16 non-lean and 15 lean had completed second liver biopsy.

Results

Age, sex, alanine transaminase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), gamma-glutamyltrasferase (GGT), Homeostasis model assessment insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), triglyceride and high density lipoprotein (HDL) was similar in both groups. Steatosis, ballooning, lobular inflammation, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease activity score (NAS) and fibrosis was similar in the two groups. In lean/non-lean group, any amount of weight reduction, ≥ 5% weight reduction and ≥ 7% weight reduction was found in respectively 8/11, 5/6 and 2/6 patients. In both lean and non-lean groups, weight reduction of any amount was associated with significant reduction of steatosis, ballooning and NAS, except lobular inflammation and fibrosis. In both groups, weight reduction of ≥ 5% was associated with significant reduction in NAS only. However, significant improvement in NAS was noted with ≥ 7% weight reduction in non-lean group only.

Conclusion

Smaller amount of weight reduction had the good benefit of improvement in all the segments of histological activity in both lean and non-lean NASH.

Introduction

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), the most prevalent chronic liver disorder worldwide, is a clinico-histopathological entity ranging from simple fat accumulation (steatosis) to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH).[1,2] NASH is diagnosed by the joint presence of steatosis and inflammation along with hepatocyte injury (evident as hepatocyte ballooning).[3] It is estimated that NASH occurs in 20% of patients with NAFLD, whereas in Bangladesh, it shows a higher proportion (42.4%).[4,5] Due to its progressive nature, approximately 30% to 40% of patients with NASH develop fibrosis and others lead to advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis. Moreover, it is one of the most common indications of liver transplantation worldwide.[5] The risk of progression to advanced hepatic complications is influenced by the severity of underlying liver histology as, it is documented that increased rate of deleterious outcomes are observed in patients with advanced fibrosis. However, with therapeutic interventions, reversal as well as prevention of further progression of fibrosis is possible as well.[6]

NAFLD is commonly observed in obese people and is associated with insulin resistance (IR) and metabolic syndrome (MS). Nonetheless, NAFLD/NASH in non-obese or persons with normal body mass index (BMI) (i.e., < 25 kg/m2), termed as, “lean NASH” is not uncommon.[7,8] As in Bangladesh, it was demonstrated that 25.6% of NAFLD patients were found non-obese, and among the non-obese NAFLD, 53.1% were documented as NASH.[9] Considering the obesity, from another study, NASH is reported in 18.5% of obese and 2.7% of lean patients.[10] Lean NASH is a distinct phenotype of NAFLD in terms of relationship with BMI, sharing the metabolic characters and liver pathology, as seen in obese persons having NASH.[7] Despite this, the pathophysiologic issue behind NAFLD in lean subjects is not settled enough; it seems that there is no straight pathway to this multifactorial phenotype. Genetic predisposition along with environmental factors, such as dietary composition and gut microbiome may play an important role.[11]

Treatment of NASH is applied with the targets of reducing the NASH-related mortality and prevention of the progression to cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). At present, the resolution of the histological findings of NASH is now approved as a surrogate endpoint. The major treatment offered for NAFLD remains lifestyle changes including weight reduction by a healthy diet and performing regular physical activity.[12,13] It is evident that improvements of liver histology in NASH can be achieved through losing a certain amount of weight.[14] Promrat et al. in his RCT showed that almost 7–10% of weight reduction can improve the NAFLD activity score (NAS) and its elements (steatosis, lobular inflammation and ballooning).[15] Not only that, even a greater amount of weight reduction (≥ 10% of total body weight) make significant regression of hepatic fibrosis in NASH also. Most of these studies were performed among obese or overweight individuals.[1] Single case report by Merchant et al. described that like obese NAFLD patients, lean NAFLD patients can get benefits in dietary modification as well as weight reduction strategy.[16] This data is also supported by another study that concluded that change in the body weight is a potent independent issue for both the development and regression of NAFLD in non-obese individuals, regardless of baseline BMI.[17] As none of the study focused on the benefits of weight reduction on histological activity in patients with lean NASH, the study was focused to explore the effect of weight reduction strategy in lean NASH individuals.

Materials and methods

Design, subjects of the study

This prospective study was confined to the Department of Hepatology, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University (BSMMU). Data collection was done within the period from February 2016 to September 2017. Prior to the commencement of the study, ethical permission was taken from Institutional Review Board of BSMMU. All methods performed in this study were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. For this comparative analysis, study populations were divided into two groups: 1) lean NASH patients defined by BMI < 25 kg/m2 were compared with 2) non-lean NASH patients defined by BMI > 25 kg/m2. Adult patients aged ≥ 18 years with histology-proven NAFLD (NAS score ≥ 5) were initially approached and were screened subsequently according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Patients with history of alcohol consumption (≥ 20 g/day in men or ≥ 10 g/day in women), positive viral makers (hepatitis B, hepatitis C), or known case of secondary fatty liver (e.g., use of systemic drugs including anabolic steroids, tamoxifen, anticonvulsant, antiarrhythmic drugs, etc.), chronic liver disease (CLD) with known etiology, pregnant women or suffering from any kind of malignancies before baseline were excluded. Moreover, patients with known contraindications to liver biopsy were also excluded. Liver biopsy for histopathological assessment was done at inclusion and at follow-up one year after inclusion in accordance with AASLD guideline for liver biopsy. Informed written consent was taken from all the subjects before inclusion.

Finally, a total of 20 lean and 20 non-lean histologically proven NASH patients were included and were investigated to summarize the baseline information. Data collection were done with an aid of a pretested questionnaire aiming to collect data in several dimensions: a) sociodemographic profile, b) anthropometric information including weight, height, BMI and waist circumference, c) glycemic status and insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), d) liver biochemistry (alanine transaminase [ALT], aspartate aminotransferase [AST], gamma-glutamyltrasferase [GGT]), e) liver histopathology (NAS score and fibrosis), and f) other comorbid conditions like diabetes mellitus (DM), dyslipidemia, hypertension, and so on. Similar data were collected at the end of the follow-up for 1 year. Patients were followed-up monthly for the first 3 months and three monthly up to 1 year. During the study period, moderate exercise along with dietary restriction was advised for both groups as weight reduction strategy. More details are described in the operational definition.

Procedure of biopsy

Liver biopsies were done within 15 days of laboratory investigations with full resuscitation facilities. Biopsy materials were immersed in 10% formalin and stained with hematoxylin-eosin and Masson’s trichome. Prepared samples were evaluated by an experienced pathologist, who was not aware about the treatment plan as well as the clinical and biochemical parameters of any patient. Evaluation of biopsy samples was done using Kleiner. This histological scoring system quantifies steatosis, lobular inflammation, and ballooning resulting in NAS that ranged between 0 and

8. Scores greater than or equal to 5 are largely diagnostic of NASH. Fibrotic changes were evaluated separately from NAS, with score ranging from 0 (no fibrosis) to 4 (cirrhosis). Standard aseptic precautions were maintained during the collection of the biopsy materials. In all the cases, informed written consent was ensured from all the patients before performing biopsy procedure.

Follow-up of the patients

Following the end of the 1-year prospective follow-up, the total amount of attrition was 4 in the non-lean group and 5 in the lean group. Therefore, 16 non-lean and 15 lean had completed the second liver biopsy, and also, rest of the investigations.

Data analysis technique of the study

Unpaired t test was done to compare the baseline variables and the improvement in different parameters at the end of the study. Paired t test was done to compare the baseline and the end of treatment values. Logistic regression analysis was done to assess the effect of important factors on the final outcome.

Operational definition

BMI: BMI was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height (m) squared; a BMI < 25 kg/m2 was considered as lean subjects and BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 was used to identify non-lean subjects.

Waist circumference: It was measured in the horizontal plane midway between lowest rib and the iliac crest. The measurement tried to keep the nearest 0.1 cm at the end of a normal expiration. Before recording the measurement, it was ensured that the tape was snug but did not compress the skin and was parallel to the floor. The reproducibility was also assessed.

Hypertension: was defined as systolic blood pressure ≥ 130 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 85 mm Hg;

DM:[18] DM was defined by:

FPG ≥ 126 mg/dL (7.0 mmol/L). Fasting is defined as no caloric intake for at least 8 h.

Or

2-h PG ≥ 200 mg/dL (11.1 mmol/L) during an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT). The test was performed as described by the WHO, using a glucose load containing the equivalent of 75 g anhydrous glucose dissolved in water.

Or

In a patient with classic symptoms of hyperglycemia or hyperglycemic crisis, a random plasma glucose ≥ 200 mg/dL (11.1 mmol/L)

macrovesicular steatosis,

lobular inflammation and

hepatocellular injury or ballooning degeneration in acinar zone 3

Components of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease activity score

| Item | Definition < 5% | Score 0 |

|---|---|---|

| Steatosis (0–3) | 5–33% | 1 |

| > 33%–66% | 2 | |

| > 66% | 3 | |

| Lobular inflammation (0–3) | No foci | 0 |

| < 2 foci per 200 × field | 1 | |

| 2-4 foci per 200 × field | 2 | |

| > 4 foci per 200 × field | 3 | |

| Ballooning (0–2) | None | 0 |

| Few balloon cells | 1 | |

| Many cells/prominent ballooning | 2 |

• Staging system for NASH: [19,20] Brunt definition of staging of NASH was used in the study for staging of the study population.[19] Zone 3 perisinusoidal/pericellular focal or extensive fibrosis was considered as stage 1 NASH, Zone 3 perisinusoidal/pericellular fibrosis with focal or extensive periportal fibrosis was stage 2 NASH, Zone 3 perisinusoidal/pericellular fibrosis and portal fibrosis with focal or extensive bridging fibrosis was defined as stage 3 NASH, while cirrhosis of liver was defined as stage 4 NASH.

Diet and exercise module

Patient was encouraged for moderate exercise, that is, walking 30 minutes a day. Dietary advice to avoid saturated fat, excessive sugar containing diet, soft drinks, fast food and refined carbohydrate were given to both groups of patients according to diet chart of NAFLD. Diabetic patients were treated with life style modification, and if required, with oral sulphonylureas – Gliclazide, Glimeperide, or with Insulin. Hypertensive patients were treated using antihypertensive drug except ACE – inhibitor, ARB and calcium channel blocker (Diltiazem) due to their beneficial effect on steatohepatitis and fibrosis.

Results

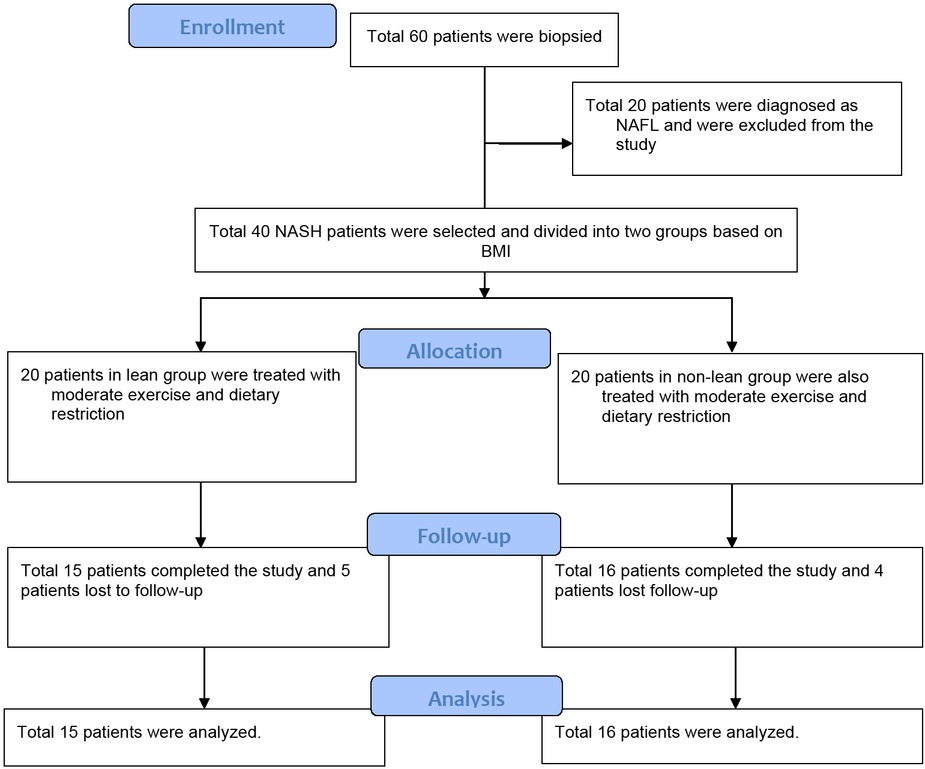

Total 40 patients of histologically proven NASH were initially selected for inclusion. Twenty patients were included in the lean group and another 20 patients were included in the non-lean group based on their BMI. Five patients from the lean group and 4 patients from the non-lean group were lost to follow-up (Figure 1). Total 31 NASH patients (15 patients in the lean group and 16 patients in the non-lean group) were considered for the final analysis.

Flow chart of patient selection

Comparison of baseline characteristics is enlisted in Table 2. No statistically significant difference was noted between the lean and non-lean patients in relation to age, sex, HOMA IR, serum lipid profile, liver biochemistry, and liver histology. BMI, waist circumference (WC) and FBS were significantly high in non-lean group than in lean group (P = 0.000 and P = 0.01, respectively). Non-lean group had a significantly higher number of diabetes and hypertensive patients (7 cases each) than that of the lean group (0 and 1 case respectively; P = 0.004 and P = 0.018 respectively).

Base line characteristics of lean and non-lean NASH patients

| Variable | Lean (n = 15) Mean ± SD | Non-lean (n = 16) Mean ± SD | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 34.80 ± 8.66 | 37.88 ± 5.83 | 0.253 |

| Sex (male/female) | 6/9 | 6/10 | 0.886 |

| BMI(kg/m2) | 23.26 ± 1.10 | 27.84 ± 3.89 | 0.000 |

| WC (cm) | 88.60 ± 3.58 | 95.16 ± 9.97 | 0.023 |

| ALT (U/L) | 46.53 ± 25.55 | 57.25 ± 25.48 | 0.252 |

| AST (U/L) | 35.33 ± 15.02 | 42.25 ± 28.01 | 0.403 |

| GGT (U/L) | 44.73 ± 16.96 | 50.75 ± 28.77 | 0.488 |

| Fasting blood sugar (mmol/L) | 4.90 ± 0.78 | 5.87 ± 1.59 | 0.040 |

| HOMA IR | 1.90 ± 1.47 | 2.19 ± 1.29 | 0.579 |

| S. Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 195.60 ± 60.01 | 201.56 ± 68.35 | 0.799 |

| S. LDL (mg/dL) | 116.50 ± 41.92 | 98.64 ± 56.87 | 0.375 |

| S. HDL (mg/dL) | 39.33 ± 14.78 | 38.44 ± 27.71 | 0.912 |

| S. Triglyceride (mg/dL) | 222.20 ± 161.141 | 320.56 ± 249.31 | 0.206 |

| Diabetes (present/absent) | 0/15 | 7/9 | 0.004 |

| Hypertension (present/absent) | 1/14 | 7/9 | 0.018 |

| Steatosis | 2.0 ± .54 | 2.06 ± .57 | 0.756 |

| Ballooning | 1.53 ± .52 | 1.44 ± .51 | 0.608 |

| Lobular inflammation | 1.73 ± .59 | 1.69 ± .48 | 0.814 |

| NAS | 5.27 ± .46 | 5.19 ± .54 | 0.665 |

| Fibrosis | 1.47 ± .74 | 1.62 ± 1.03 | 0.628 |

P value was determined by unpaired t test; BMI: body mass index; WC: waist circumference; ALT: alanine transaminase; AST: aspartate aminotransferase;

ALP: alkaline phosphatase; GGT; gamma-glutamyltrasferase; HOMA-IR: homeostasis model assessment insulin resistance; HDL: high density lipoprotein;

LDL: low density lipoprotein; NAS: nonalcoholic fatty liver disease activity score

Following a year of exercise and diet restriction regimen, only improvement in weight was found to be significantly higher in the non-lean group than lean group (Table 3). In the non-lean group, mean weight reduction was 3.71 ± 4.58 kg, and in the lean group, mean weight reduction was 0.88 ± 2.79 kg (P = 0.045). Improvement in other anthropometric, biochemical and histological parameters between lean and non-lean group did not differ significantly.

Comparison of anthropometric, biochemical and histological improvement between lean and non-lean NASH

| Variable improvement | Lean (n = 15) | Non-lean (n = 16) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weight (kg) | Mean ± SD 0.88 ± 2.79 | Mean ± SD 3.71 ± 4.58 | 0.045 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.37 ± 1.14 | 1.49 ± 1.85 | 0.052 |

| WC (cm) | 1.73 ± 2.49 | 1.59 ± 6.80 | 0.940 |

| Steatosis | 0.47 ± 0.99 | 0.44 ± 0.51 | 0.920 |

| Ballooning | 0.20 ± 0.68 | 0.19 ± 0.65 | 0.959 |

| Lobular inflammation | 0.27 ± 0.70 | 0.19 ± 0.54 | 0.728 |

| NAS | 1.03 ± 0.26 | 0.91 ± 0.23 | 0.732 |

| Fibrosis | 0.00 ± 0.65 | 0.19 ± 1.16 | 0.583 |

| ALT (U/L) | 14.80 ± 28.49 | 17.81 ± 31.29 | 0.782 |

| AST (U/L) | 11.93 ± 14.03 | 10.75 ± 27.99 | 0.884 |

| GGT (U/L) | 15.20 ± 13.79 | -3.75 ± 37.03 | 0.073 |

| Fasting blood sugar (mmol/L) | 0.06 ± 0.75 | 0.04 ± 1.81 | 0.956 |

| HOMA IR | 0.68 ± 1.71 | -0.14 ± 1.95 | 0.272 |

| S. Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 18.66 ± 64.53 | 11.12 ± 83.31 | 0.797 |

| S. LDL (mg/dL) | 15.73 ± 50.09 | 9.10 ± 50.27 | 0.766 |

| S. HDL (mg/dL) | 25.33 ± 96.40 | -8.81 ± 23.47 | 0.253 |

| S. Triglyceride (mg/dL) | 32.33 ± 216.05 | -26.13 ± 235.09 | 0.501 |

P value was determined by unpaired t test; BMI: body mass index; NAS: nonalcoholic fatty liver disease activity score; ALT: alanine transaminase; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; ALP: alkaline phosphatase; GGT; gamma-glutamyltrasferase; HOMA-IR: homeostasis model assessment insulin resistance; HDL: high density lipoprotein; LDL: low density lipoprotein.

Table 4 shows the effect of weight reduction on overall histological activity and fibrosis score of lean and non-lean NASH patient. Any amount of weight reduction was found in 8 lean patients and 11 non-lean patients. Weight reduction of ≥ 5% from the baseline was found in 5 lean and 6 non-lean patients and of ≥ 7% from the baseline was found in 2 lean and 6 non-lean patients. Any amount of weight reduction was associated with significantly improved steatosis, ballooning, and NAS score after one year in both lean and non-lean patients (P = 0.001, P = 0.005, and P = 0.000 respectively for lean, and P = 0.016, P = 0.016 and P = 0.000, respectively, for non-lean patients). Weight reduction ≥ 5% was associated with a significant improvement in the NAS score in both lean and non-lean NASH patients (P = 0.009 and P = 0.01, respectively). But, weight reduction of ≥ 7% was found to improve the NAS score significantly only in the non-lean patients (P = 0.01).

Effect of weight reduction on histological activity and fibrosis of lean and non-lean NASH

| Lean (n = 15) | Non-lean (n = 16) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | n | Base line | After 1 year | P | n | Base line | After 1 year | P |

| (Mean ± SD) | (Mean ± SD) | (Mean ± SD) | (Mean ± SD) | |||||

| Weight in kg | 15 | 58.33 ± 7.56 | 57.47 ± 7.55 | 0.250 | 16 | 68.53 ± 9.97 | 64.81 ± 9.31 | 0.005 |

| Steatosis | ||||||||

| No WR | 7 | 2.00 ± 0.58 | 2.14 ± 0.69 | 0.604 | 5 | 2.00 ± 0.70 | 1.60 ± 0.54 | 0.178 |

| Any WR | 8 | 2.5 ± 0.52 | 1.37 ± 0.831 | 0.001 | 11 | 2.09 ± 0.54 | 1.64 ± 0.81 | 0.016 |

| WR ≥ 5% | 5 | 1.80 ± 0.45 | 1.00 ± 0.71 | 0.099 | 6 | 2.17 ± 0.41 | 1.67 ± 0.81 | 0.076 |

| WR ≥ 7% | 2 | 2.00 ± 0.00 | 1.50 ± 0.71 | 0.500 | 6 | 2.17 ± 0.41 | 1.67 ± 0.82 | 0.076 |

| Ballooning | ||||||||

| No WR | 7 | 1.43 ± 0.53 | 1.29 ± 0.76 | 0.689 | 5 | 1.20 ± 0.45 | 1.60 ± 0.55 | 0.178 |

| Any WR | 8 | 1.21 ± 0.42 | 1.21 ± 0.42 | 0.005 | 11 | 1.55 ± 0.52 | 1.09 ± 0.30 | 0.016 |

| WR ≥ 5% | 5 | 1.60 ± 0.55 | 1.20 ± 0.45 | 0.178 | 6 | 1.33 ± 0.52 | 1.00 ± .000 | 0.175 |

| WR ≥ 7% | 2 | 1.50 ± 0.71 | 1.50 ± 0.71 | NA | 6 | 1.33 ± 0.52 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 0.175 |

| Lobular inflammation | ||||||||

| No WR | 7 | 1.86 ± 0.69 | 1.71 ± 0.48 | 0.604 | 5 | 1.80 ± 0.45 | 1.80 ± 0.45 | NA |

| Any WR | 8 | 1.63 ± 0.50 | 1.32 ± 0.48 | 0.055 | 11 | 1.64 ± 0.51 | 1.36 ± 0.51 | 0.192 |

| WR ≥ 5% | 5 | 1.80 ± 0.45 | 1.20 ± 0.45 | 0.070 | 6 | 1.67 ± 0.52 | 1.17 ± 0.41 | 0.076 |

| WR ≥ 7% | 2 | 2.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | NA | 6 | 1.67 ± 0.52 | 1.17 ± 0.41 | 0.076 |

| NAS | ||||||||

| No WR | 7 | 5.29 ± 0.49 | 5.14 ± 0.90 | 0.604 | 5 | 5.00 ± 0.00 | 5.00 ± 0.70 | 1.00 |

| Any WR | 8 | 5.26 ± 0.56 | 3.89 ± 0.94 | 0.000 | 11 | 5.27 ± 0.65 | 4.09 ± 0.94 | 0.000 |

| WR ≥ 5% | 5 | 5.20 ± 0.45 | 3.40 ± 0.89 | 0.009 | 6 | 5.17 ± 0.41 | 3.83 ± 0.75 | 0.010 |

| WR ≥ 7% | 2 | 5.50 ± 0.71 | 4.00 ± 0.00 | 0.205 | 6 | 5.17 ± 0.41 | 3.83 ± 0.75 | 0.010 |

| Fibrosis | ||||||||

| No WR | 7 | 1.71 ± 0.95 | 2.00 ± 0.82 | 0.356 | 5 | 1.80 ± 1.10 | 2.00 ± 0.71 | 0.799 |

| Any WR | 8 | 1.42 ± 0.84 | 1.11 ± 0.46 | 0.083 | 11 | 1.55 ± 1.04 | 1.18 ± 0.60 | 0.221 |

| WR ≥ 5% | 5 | 1.40 ± 0.55 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 0.178 | 6 | 1.50 ± 0.84 | 1.33 ± 0.82 | 0.363 |

| WR ≥ 7% | 2 | 1.50 ± 0.71 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 0.500 | 6 | 1.50 ± 0.84 | 1.33 ± 0.82 | 0.363 |

P value was determined by paired t test; WR: weight reduction; NAS: NAFLD activity score

Logistic regression analysis was done to find out the best predictor of patient response. As shown in Table 2, only improvement in weight was found to differ across groups. Therefore, univariate analysis was done for the category of patients (lean and non-lean) and weight reduction (Table 5). Weight reduction was found to have a significant effect on the histological improvement at the end of the treatment in univariate analysis (OR 25.5; 95% CI 3.58–181.61; P = 0.001). On multivariate analysis, the lean patients were found to have higher odds than the non-lean patients for histological improvement, although it was not statistically significant (OR 3.56; 95% CI 0.34–37.80; P = 0.293). On the

Predictors of patient response

| Predictors | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P value | OR 95% CI | P value | OR 95% CI | |

| Category of patients (Lean) | 0.809 | 1.20 (0.27–5.25) | 0.291 | 3.56 (0.34–37.80) |

| Weight reduction | 0.001 | 25.50 (3.58–181.61) | 0.002 | 40.04 (3.73–429.38) |

other hand, weight reduction was independently associated with a significant improvement in the histological status (steatosis, ballooning and NAS) of NASH patients (OR 40.04; 95% CI 3.73–429.38; P = 0.002).

Discussion

NASH has become an important health concern as it is associated with progressive liver disease, cardiovascular mortality and type-2 diabetes.[22] Various modalities of treatment are being tested for the management of NASH.[22] Among different drugs tested,[23] vitamin E,[24,25] pioglitazone,[25] liraglutide,[26] telmisartan,[27] pentoxifylline[28] were found to improve histological activity and fibrosis in different degrees. But these must be balanced with their potential adverse effects. Therefore, diet and lifestyle modification, with weight reduction remains the mainstay of treatment in these patients.[16,22] Previous studies testing the effectiveness of lifestyle modification in NAFLD have found that 7 to 10% weight loss is accompanied by a remarkable normalization of liver enzymes and a systematic reduction of liver fat.[29] But, no previous study tested the effect of weight reduction on non-obese lean NASH patients. This study was the first attempt to test and compare the effect of weight reduction in lean and non-lean NASH patients.

We initially included 40 patients of histologically proven NASH in the study, among whom 9 patients were lost to follow-up. Total 15 lean NASH cases and 16 non-lean NASH cases were tested in the final analysis. Both groups were advised moderate intensity exercise and dietary restriction for one year. Our results show that both lean and non-lean patients achieved weight reduction at the end of the treatment, with the reduction being significant in the non-lean group. 8 and 11 lean and non-lean patients respectively achieved any amount of weight reduction, 5 and 6 lean and non-lean patients respectively achieved ≥ 5% weight reduction, and 2 and 6 lean and non-lean patients respectively achieved ≥ 7% weight reduction.

Any amount of weight reduction was found to be significantly associated with improvement in steatosis, ballooning and NAS score in both lean and non-lean patients. More than or equal to 5% weight reduction was associated with improvement in overall NAS score in both groups without showing significant improvement in individual scores. But ≥ 7% reduction in weight was not associated with any further improvement in NAS score of lean patients. In comparison, non-lean patients showed a significant improvement in NAS score with ≥ 7% reduction. In a meta-analysis research, Musso et al. described that body weight reduction through sedentary life style changes was associated with a significant histological improvement of NASH patient. But, they could not quantify the cut off value.[30] Promrat et al. have shown that weight reduction of more than 7% sustained over 48 weeks is associated with a significant reduction in the histological severity of obese NASH patients.[16] Vilar-Gomez et al. found that a 10% reduction in weight over 52 weeks was associated with the highest reduction in NAS reduction, NASH resolution and fibrosis regression in non-lean NASH.[31] Our study suggests that weight reduction of more than ≥ 5% benefits the histologic activity of liver in both lean and non-lean (obese) NASH patients.

Although improvement in NAS score was noted in both groups of patients, neither group achieved improvement in fibrosis with weight reduction over the year. This may indicate that the effect of weight loss on fibrosis is smaller than the effect on overall histologic activity, and thus, could not be detected with our sample size or that longer than a year study is needed to detect changes in fibrosis score. These findings are correlated with that of Promrat et al.[16]

In the multivariate analysis, we had a unique finding that lean NASH cases have higher odds of achieving improvement in NAS score than non-lean NASH cases. Also, weight reduction was independently associated with a significant improvement in liver histology. Kim et al. have reviewed that visceral obesity as opposed to general obesity, high fructose and cholesterol intake, and genetic risk factors were linked with non-obese NAFLD.[32] Lifestyle modification, including dietary changes and physical activity to reduce visceral adiposity through weight reduction was suggested to be a standard care in non-obese NAFLD patients in their study. Fracanzani et al. found that lean and non-lean NAFLD patients had an increasing risk of NASH with increasing visceral obesity.[32] They used WC to represent visceral obesity, which is a relatively accurate surrogate marker.[33] We measured WC before and after the intervention and noted a statistically similar decrease in both lean and non-lean patients. Therefore, our findings indicate that overall body weight reduction independent of reduction in visceral adiposity is also beneficial for improvement in overall histologic activity of lean in comparison to non-lean NASH patients.

NAFLD is a common disease in non-obese (lean) people in the South Asian region.[35] Alazawi et al. found that Bangladeshi ethnicity is an independent risk factor for developing NAFLD[36] and prevalence of NASH was found to be high in NAFLD patients in Bangladesh.[22] Hence, it is pertinent to focus on the treatment of lean non-obese NASH patients alongside their obese counterparts. Weight reduction strategy could be a good starting point, as we have shown that any amount of weight reduction is associated with improvement in histology of liver.

However, this study was limited in the absence of a control group. Also, a precise cut-off value of weight reduction for significant improvement in histological activity of liver in the study could not be evaluated due to the small sample size. Therefore, large randomized control trials addressing the issue of cut-off point of weight reduction as well as trials assessing the correlation of percent weight reduction with reduction in NAS score are some good topics for future research.

Conclusion

A weight reduction strategy of one year significantly improves the histologic activity of liver in both lean and non-lean NASH patients.

Ethical consideration and informed written consent

The researcher was duly concerned about the ethical issues related to the study. Formal ethical clearance was taken from the Institutional Review Board of BSMMU for conducting the study, as well as a formal permission was taken from the responders. Confidentiality was maintained properly. Informed written consent was taken from the subject informing the nature and purpose of the study, procedure of the study, the right to refuse, accept and withdraw to participate in the study as well as the participants didn’t gain financial benefit from this study. The present study posed a very low risk to the participants, as procedures such as medical treatments, invasive diagnostics or procedures causing psychological, spiritual or social harm were not included.

Conflict of Interest

Conflict of Interests: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

1 Romero-gómez M, Zelber-sagi S, Trenell M. Treatment of NAFLD with diet, physical activity and exercise. J Hepatol 2017; 67: 829–46.10.1016/j.jhep.2017.05.016Search in Google Scholar PubMed

2 Krawczyk M, Bonfrate L. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2010; 24: 695–708.10.1016/j.bpg.2010.08.005Search in Google Scholar PubMed

3 Burt AD, Tiniakos DG, Lackner C. Diagnosis and Assessment of NAFLD : Definitions and Histopathological Classification. Semin Liver Dis 2015; 35: 207–20.10.1055/s-0035-1562942Search in Google Scholar PubMed

4 Alam S, Alam M, Alam SMNE, Chowdhury ZR, Kabir J. Prevalence and Predictor of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH) in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD). J Bangladesh Coll Physicians Surg 2015; 32: 71.10.3329/jbcps.v32i2.26034Search in Google Scholar

5 Spengler EK, Mhsc RL. Recommendations for Diagnosis, Referral for Liver Biopsy, and Treatment of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Mayo Clin Proc 2015; 90: 1233–46.10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.06.013Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

6 Schuppan D, Surabattula R, Wang XY. Determinants of fibrosis progression and regression in NASH. J Hepatol 2018; 68: 238–50.10.1016/j.jhep.2017.11.012Search in Google Scholar PubMed

7 Das K, Chowdhury A. Lean NASH : distinctiveness and clinical implication. Hepatol Int 2013; 7: s806–13.10.1007/s12072-013-9477-5Search in Google Scholar PubMed

8 Paschos P, Paletas K. Non alcoholic fatty liver disease and metabolic syndrome. Hippokratia 2009; 13: 9–19.Search in Google Scholar

9 Alam S, Gupta U Das, Alam M. Clinical, anthropometric, biochemical, and histological characteristics of nonobese nonalcoholic fatty liver disease patients of Bangladesh. Indian J Gastroenterol 2014; 33: 452–7.10.1007/s12664-014-0488-5Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10 Medina J, Fernandez-salazar LI, Garcia-buey L, Moreno-otero R. Approach to the pathogenesis and treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Diabetes Care 2004; 27:2057–66.10.2337/diacare.27.8.2057Search in Google Scholar PubMed

11 Sookoian S, Pirola CJ. Genetic predisposition in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Mol Hepatol 2017; 23: 1–12.10.3350/cmh.2016.0109Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

12 Zelber-sagi S, Godos J, Salomone F. Lifestyle changes for the treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease : a review of observational studies and intervention trials. Ther Adv Gastroenterol Rev 2016; 9: 392–407.10.1177/1756283X16638830Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

13 European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL), European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD), European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO). EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol 2016; 64: 1388–402.10.1016/j.jhep.2015.11.004Search in Google Scholar PubMed

14 Wands JR, Fava J, Wing RR. Randomized Controlled Trial Testing the Effects of Weight Loss on Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH). Hepatology 2011;51:121–9.10.1002/hep.23276Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

15 Promrat K, Kleiner DE, Niemeier HM, Jackvony E, Kearns M, Wands JR, et al. Randomized controlled trial testing the effects of weight loss on nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology 2010; 51: 121–9.10.1002/hep.23276Search in Google Scholar

16 Merchant HA. Can Diet Help Non-Obese Individuals with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD)?. J Clin Med 2017; 6: 88.10.3390/jcm6090088Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

17 Kim NH, Kim JH, Kim YJ, Yoo HJ, Kim HY, Seo JA, et al. Clinical and metabolic factors associated with development and regression of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in nonobese subjects. Liver Int 2014; 34: 604–11.10.1111/liv.12454Search in Google Scholar PubMed

18 American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care 2016; 39: S13–S22.10.2337/dc16-S005Search in Google Scholar PubMed

19 Brunt EM, Janney CG, Di Bisceglie AM, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Bacon BR. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a proposal for grading and staging the histological lesions. Am J Gastroenterol 1999; 94: 2467–74.10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01377.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

20 Takahashi Y, Fukusato T. Histopathology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease/nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 14; 20: 15539–48.10.3748/wjg.v20.i42.15539Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

21 Kleiner DE, Brunt EM, Van Natta M, Behling C, Contos MJ, Cummings OW, et al. Design and validation of a histological scoring system for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2005; 41: 1313–21.10.1002/hep.20701Search in Google Scholar PubMed

22 Alam S, Noor-E-Alam SM, Chowdhury ZR, Alam M, Kabir J. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease patients of Bangladesh. World J Hepatol 2013; 5: 281–7.10.4254/wjh.v5.i5.281Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

23 Hardy T, Anstee QM, Day CP. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: New treatments. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2015; 31: 175–83.10.1097/MOG.0000000000000175Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

24 Hadi HE, Vettor R, Rossato M. Vitamin E as a Treatment for Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Reality or Myth? Antioxidants 2018;7:12.10.3390/antiox7010012Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

25 Sanyal AJ, Chalasani N, Kowdley KV, McCullough A, Diehl AM, Bass NM, et al. Pioglitazone, Vitamin E, or Placebo for Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. N Engl J Med 2010; 362: 1675–85.10.1056/NEJMoa0907929Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

26 Ipsen DH, Rolin B, Rakipovski G, Skovsted GF, Madsen A, Kolstrup S, et al. Liraglutide Decreases Hepatic Inflammation and Injury in Advanced Lean Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2018; 123:704–13.10.1111/bcpt.13082Search in Google Scholar PubMed

27 Alam S, Kabir J, Mustafa G, Gupta U, Hasan SKMN, Alam AKMK. Effect of telmisartan on histological activity and fibrosis of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: A 1-year randomized control trial. Saudi J Gastroenterol 2016; 22: 69.10.4103/1319-3767.173762Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

28 Alam S, Nazmul Hasan S, Mustafa G, Alam M, Kamal M, Ahmad N. Effect of pentoxifylline on histological activity and fibrosis of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis patients: A one year randomized control trial. J Transl Intern Med 2017; 5:155–63.10.1515/jtim-2017-0021Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

29 Marchesini G, Petta S, Dalle Grave R. Diet, weight loss, and liver health in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Pathophysiology, evidence, and practice. Hepatology 2016; 63: 2032–43.10.1002/hep.28392Search in Google Scholar PubMed

30 Musso G, Gambino R, Cassader M, Pagano G. Meta-analysis : Natural history of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and diagnostic accuracy of non-invasive tests for liver. Ann Med. 2011;43:617–49.10.3109/07853890.2010.518623Search in Google Scholar PubMed

31 Vilar-Gomez E, Martinez-Perez Y, Calzadilla-Bertot L, Torres-Gonzalez A, Gra-Oramas B, Gonzalez-Fabian L, et al. Weight loss through lifestyle modification significantly reduces features of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology 2015; 149: 367–78.10.1053/j.gastro.2015.04.005Search in Google Scholar PubMed

32 Kim D, Kim WR. Non-Obese Fatty Liver Disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017; 15: 474–85.10.1016/j.cgh.2016.08.028Search in Google Scholar PubMed

33 Fracanzani AL, Petta S, Lombardi R, Pisano G, Russello M, Consonni D, et al. Liver and Cardiovascular Damage in Patients with Lean Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease, and Association with Visceral Obesity. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017; 15:1604–11.10.1016/j.cgh.2017.04.045Search in Google Scholar PubMed

34 Borruel S, Moltó JF, Alpañés M, Fernández-Durán E, Álvarez-Blasco F, Luque-Ramírez M, et al. Surrogate markers of visceral adiposity in young adults: Waist circumference and body mass index are more accurate than waist hip ratio, model of adipose distribution and visceral adiposity index. PLoS One 2014; 9: 1–17.10.1371/journal.pone.0114112Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

35 Alam S, Lama TK, Mustafa G, Alam M, Ahmad N. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: The Future Frontier of Hepatology for South Asia//Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease- Molecular Bases, Prevention and Treatment. 2018: 79–91.10.5772/intechopen.71159Search in Google Scholar

36 Alazawi W, Mathur R, Abeysekera K, Hull S, Boomla K, Robson J, et al. Ethnicity and the diagnosis gap in liver disease: A population-based study. Br J Gen Pract 2014; 64: e694–702.10.3399/bjgp14X682273Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2019 Shahinul Alam, Mohammad Jahid Hasan, Md. Abdullah Saeed Khan, Mahabubul Alam, Nazmul Hasan, published by Sciendo

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Editorial

- Application of wearable technology in clinical walking and dual task testing

- Commentary

- A hypothetical approach on gender differences in cancer diagnosis

- Review Article

- Endoscopic Ultrasound-guided Gastroenterostomy: A Promising Alternative to Surgery

- Original Article

- Treatment of ventilator-associated pneumonia with high-dose colistin under continuous veno-venous hemofiltration

- Effect of weight reduction on histological activity and fibrosis of lean nonalcoholic steatohepatitis patient

- Case Report

- Elevated lactic acid during ketoacidosis: pathophysiology and management

- Intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in a young female: Views from a developing country

- Letter to the Editor

- Vitamin C dosing during continuous renal replacement therapy: The last word is not said!

Articles in the same Issue

- Editorial

- Application of wearable technology in clinical walking and dual task testing

- Commentary

- A hypothetical approach on gender differences in cancer diagnosis

- Review Article

- Endoscopic Ultrasound-guided Gastroenterostomy: A Promising Alternative to Surgery

- Original Article

- Treatment of ventilator-associated pneumonia with high-dose colistin under continuous veno-venous hemofiltration

- Effect of weight reduction on histological activity and fibrosis of lean nonalcoholic steatohepatitis patient

- Case Report

- Elevated lactic acid during ketoacidosis: pathophysiology and management

- Intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in a young female: Views from a developing country

- Letter to the Editor

- Vitamin C dosing during continuous renal replacement therapy: The last word is not said!