Abstract

The gut microflora is a combination of all microbes in intestine and their microenvironment, and its change can sensitively reflect the relevant response of the body to external environment and remarkably affect body's metabolism as well. Recent studies have found that cold exposure affects the body's gut microflora, which can lead to changes in the body's metabolism of glucose and lipid. This review summarizes recent research on the effects of cold exposure on gut microbes and metabolism of glucose and lipid, aiming to provide some new ideas on the approaches and measures for the prevention and treatment of diabetes and obesity.

1 Introduction

With the development of economics and the change of lifestyle, the morbidity of metabolic disorders and related diseases such as diabetes and obesity has been rising in recent years showing a clear uptrend in younger population[1,2,3,4]. The gut microflora defined as all microbes in gut and their related microenvironment plays an important role in metabolic homeostasis[5,6,7]. In recent years, studies have found that gut microbes are capable of modulating metabolism and immunity, and deregulation of the gut microflora is regarded as one of crucial factors in the occurrence and development of metabolic disorders including obesity[8–9]. Cold exposure can disturb the gut microflora to impair energy homeostasis in the host[10–11]. Moreover, the detrimental effects of maternal prenatal cold exposure on gut microflora could likely be transmitted to the offspring[12]. Cold exposure can also directly disrupt the body's energy homeostasis other than through acting on the gut microflora, especially the metabolism of glucose and lipid, by affecting the function of other organs and tissues of metabolic importance. This paper reviews the recent studies related to the effects of cold exposure on the gut microflora and the metabolism of glucose and lipids in the human host.

2 The gut microflora affects the metabolism of glucose and lipid of the human body

Four kinds of microbial communities including the oral microflora, the gut microflora, the urogenital tract microflora and the skin microflora exist in the human body. Among all kinds of microflora in body, the gut microflora is the most dominant, the most complex, and the most extensively and deeply studied one. The gut microflora contains probiotics which aid host digestion, symbiotic bacteria and their metabolites, archaea, and eukaryotes[13]. Eighty percent of body's microbes exist in gut, > 99% of which are bacteria that primarily reside in the colon[14]. The total number of gut microbes exceeds 38 billion belonging to more than 1,000 different species[15]. The gut microbiome (the entire genome of all microbes in the gut) contains more than 3 million genes, 100 times the number of genes in humans[16]. Therefore, gut microbes impose powerful regulatory effect in the human body. The relationship between the body and the gut microflora is normally of mutual benefits; as the host of gut microbes, the body provides them with an appropriate living environment and certain nutrients. At the same time, the gut microflora regulate many physiological functions of the host, promoting the development of immune system[17], strengthening the intestinal barrier[18], metabolizing undigested nutrients and exogenous organisms[19], regulating the activity of the intestinal and central nervous systems, etc.[20–21]. Although the exact mechanisms behind the dynamic changes of the gut microflora in the body and the effects on the host metabolism have not been fully elucidated, their association with the energy balance and the metabolism of glucose and lipid has been well understood[22].

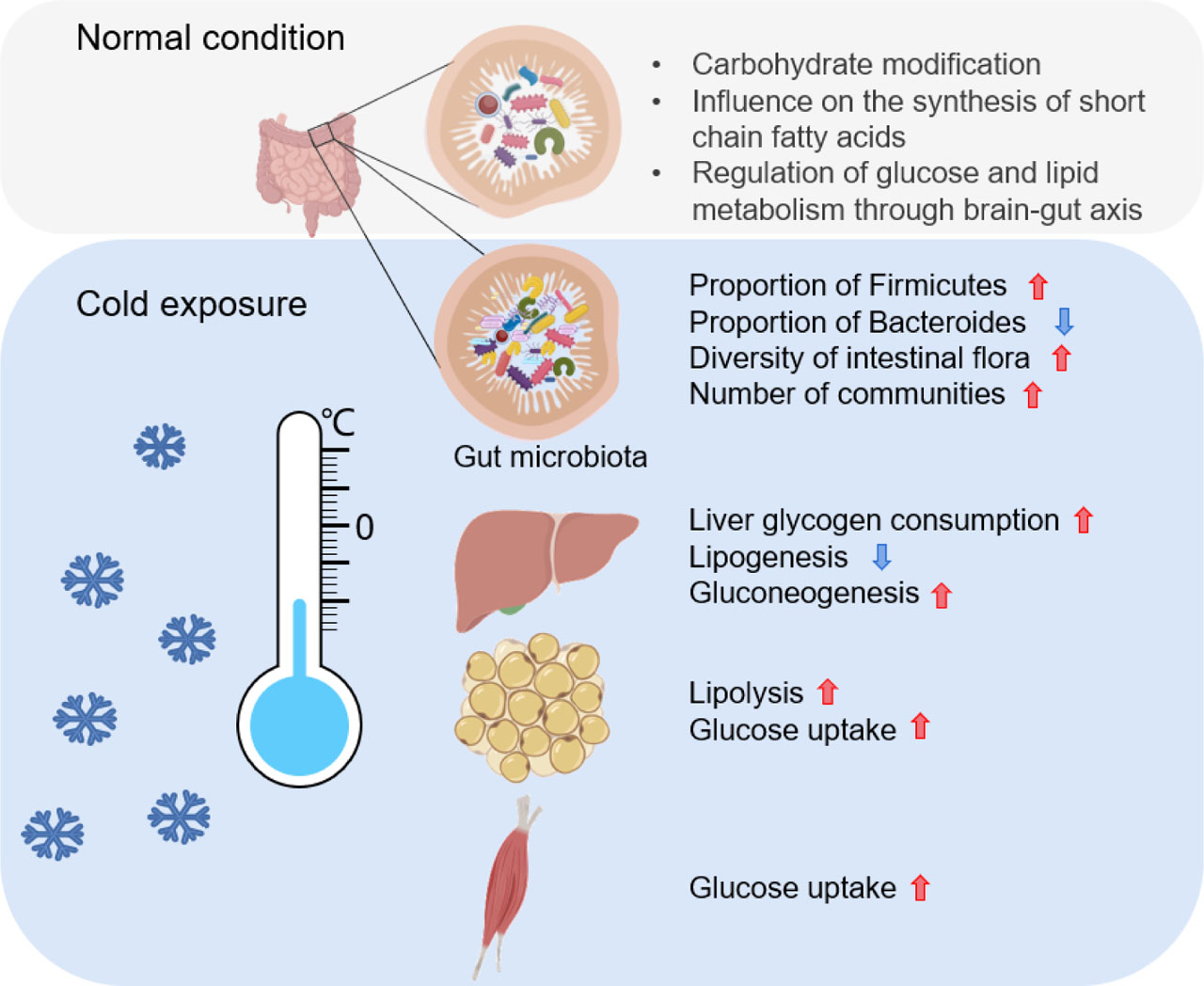

Cold exposure affects gut microbes and glucose and lipid metabolism through multiple organs

Red upward arrow indicates that the process or scale is positively affected; Blue downward arrow indicates that the process or mechanism is negatively affected.

2.1 The gut microflora affects the metabolism of glucose

The gut microflora chemically transforms exogenous substances[23], and affects their half-life and bioavailability by altering their chemical structures. Having been ingested, part of carbohydrates are absorbed by small intestine, and the remaining part are absorbed in large intestines after modification by enzymes secreted by gut microbes. Numerous enzymes associated with this process, such as hydrolases, lyases, oxidoreductases, and transferases, are widely present in the gut microflora[24,25,26]. The gut microflora uses these metabolic enzymes to hydrolyze or reduce heterologous substances and then enters the glucose metabolism[23]. Glucose tolerance reflects body's regulatory capacity of glucose. When body is in abnormal conditions, the metabolic capacity of the gut microflora is weakened, which is manifested by impaired glucose tolerance. For example, one study investigated the gut microflora of patients with impaired glucose tolerance versus those with normal glucose tolerance and found that those with impaired glucose tolerance had higher levels of Erysipelotrichaceae and Lachnospiraceae that were positively associated with metabolic disorders[27]. Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a highly prevalent metabolic disease with glucose metabolism disorder caused by insulin dysfunction as the most obvious clinical manifestation is. A research group in China performed high-throughput 16S rDNA sequencing of the intestinal flora of T2DM patients and found that the gut microflora was significantly correlated with T2DM, with the microflora altering with the progression of the disease[28]. In this study, the subjects were divided into three groups according to their glucose tolerance status: normal glucose tolerance (NGT), early T2DM group and T2DM group. From the NGT to the early T2DM group, the relative abundance of Verrucomicrobia decreased while the relative abundance of Betaproteobacteria increased, and the abundance of Betaproteobacteria further increased in the T2DM group. The relative abundance of Streptococcus continuously decreased from NGT to the early T2DM group and to the T2DM group. The relative abundance of Clostridium in the T2DM group was higher than that in the NGT and early T2DM groups. The abundance of Bacteroides and Clostridium experienced significant fluctuations along with the progression of T2DM. As a result, the gut microflora might be a potential biomarker for diabetes diagnosis[28]. Metformin is one of the most widely used drugs for treating T2DM nowadays, and it works primarily by transiently blocking the mitochondrial respiratory-chain complex I, thereby stimulating glucose consumption and decreasing hepatic glucose output[29–30]. Interestingly, a study has reported that gut microbes work together with metformin to regulate blood glucose. When obese mice with metabolic disorders were treated with metformin, eighteen signaling pathways in the gut microbiome were found activated, most of which were associated with glucose metabolic processes[31]. The above studies suggest that some specific microflora in intestines, such as β-streptococcus and Clostridium, may adjust their relative abundance to adapt to the change of the body or compensate for the impaired glucose tolerance.

The influence of microflora on glucose metabolism is not only limited to intestine but is also reflected on the interaction of the brain-intestine axis. Gut microbes initiate the signal transduction and communications between the gut and the central nervous system by activating the vagus nerve[32], regulating the homeostasis of microglia[33], and influencing tryptophan metabolism[34]. Glucose homeostasis is also an important factor in maintaining cell viability. When digestion process is affected and glucose metabolism is disturbed, the intestinal endocrine cells send signals to the central nervous system through the endocrine pathways, which directly act on the hypothalamus and the pituitary region or affect the central nervous system through the vagus nerve, thereby regulating the brain-intestinal axis to ensure normal digestion, absorption, and energy production and to maintain glucose homeostasis[35].

2.2 The gut microflora affects the metabolism of lipid

The prevalence of obesity and the associated metabolic diseases is now a public health problem in many countries. Obesity is associated with lipid metabolic disorder, which then leads to abnormal blood lipid levels, ectopic lipid deposition, and other related symptoms[36–37]. Lipid metabolism includes the biosynthesis and degradation of lipids including fatty acids, triglycerides, and cholesterol, and the gut microflora regulates these metabolic processes[38]. Lipid dysregulation is found associated with the undesirable alterations of the composition of the gut microflora. Researchers tracked the gut microflora of obese preschool children and found that the composition of gut microflora in obese children changed significantly with increasing proportion of harmful bacteria such as Proteus and decreasing proportion of beneficial bacteria such as Bifidobacterium[39]. Lipidomic analysis of regular dietary germ-free and commonly fed mice showed that the gut microflora was able to influence the lipid components in host tissue and serum[40]. Metabolomics analysis of obese people suggested that total serum cholesterol and triglyceride levels were associated with the total genomic gene abundance in gut microbiome of obese people[41]. It is also found that individuals with fewer gut microbial genes had higher triglyceride levels and lower high-density lipoprotein levels[42]. In obese mice, the diversity of gut microbes decreased, while the overall number of bacteria increased. After transplantation of gut microbes of obese and lean mice (mice with a leaner body size and less fat content) into normal germ-free mice, mice transplanted with the gut microbes from the obese produced 2% more energy after consuming the same amount of food than those transplanted with the gut microbes from the lean, suggesting that the obesity-associated gut microflora confers richer energy from the diet to the host[43].

The gut microflora affects not only the host energy intake by changing its composition, but also the synthesis of short-chain fatty acids (SCFA), an important substrate involved in lipid metabolism including lipogenesis, gluconeogenesis and cholesterol synthesis[44]. SCFA including acetic acid, propionic acid, and butyric acid are produced when dietary fiber is decomposed and fermented. Dietary fiber is positively correlated with the intestinal IgA level[45], implying that dietary fiber or its metabolites has the potential to support the B lymphocyte response in the gut. As the main microbial metabolite of dietary fiber, SCFA play a role through a variety of mechanisms, such as activating cell surface receptors, inhibiting histone deacetylase, and the like. Besides, SCFA can enhance the function of acetyl-CoA in B lymphocytes, contributing to oxidative phosphorylation, glycolysis, and fat synthesis[46]. SCFA can bind to specific G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) which are involved in the regulation of lipid and glucose metabolisms[47]. Free fatty acid receptors Ffar2 and Ffar3 are two common receptors for SCFA binding, and SCFA-Ffar regulates the balance among oxidation, synthesis, and breakdown of fatty acids in vivo[48]. In addition to the SCFA-Ffar signaling pathway, the AMP-dependent protein kinase (AMPK) signaling pathway also plays an important regulatory role in lipid and glucose metabolisms[49]. The above studies suggest that the gut microflora participates in host lipid metabolism by promoting the production of SCFA from dietary fiber, and then regulates the balance among body fat synthesis and fatty acid oxidation, synthesis, and decomposition.

Gastrointestinal hormones, receptors of the central nervous system, and neuropeptides regulate lipoprotein metabolism through the sympathetic and parasympathetic signaling pathways[50]. The gut microflora acts on the gut-central nervous system through the production of neurotransmitters to maintain the metabolic balance. One study showed that transplantation of multiple gut microbiomes in germ-free mice promoted the maturation of microglia. And some bacterial strains including Bacteroides distasonis, Lactobacillus salivarius, and Clostridium cluster XIV were able to alter the synthesis of neurotransmitters such as γ-aminobutyric acid, serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine, which may affect the activation of microglia in the brain and some brain functions[51], and those neurotransmitters are involved in lipid metabolism regulation through the endocrine system of the intestine epithelium and the brain-intestinal axis[52].

2.3 Gut microflora affects mitochondria

Mitochondria are involved in almost all processes of the life cycle, and as energy providers, mitochondria's role in glucose and lipid metabolism cannot be ignored. The gut microflora affects mitochondrial metabolism in certain ways. As a by-product of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, reactive oxygen species (ROS) may be key signaling factors for interactions between mitochondria and gut microbes[53]. Gut microbes produce short-chain fatty acids including acetic acid and butyric acid, of which acetate can enhance mitochondrial respiration and improve the defense ability of the body's intestinal epithelial cells[54], while butyric acid can stimulate mitochondrial biogenesis, improve cell respiration capacity, and activate antioxidant enzymes[55–56]. Enhanced mitochondria biogenesis has a positive regulatory effect on glycolipid metabolism[57]. Therefore, the influence of the gut microflora on mitochondria is directly related to life activities such as glucose and lipid metabolism.

3 Cold exposure altersthe gut microflora

Cold is one of the environmental challenges, which is often faced by human beings, and cold exposure refers to cold-air exposure and cold-water immersion exposure. Besides, wind speed and humidity have a synergistic effect on the intensity of cold exposure[58]. Cold exposure can affect many physiological functions and even lead to injury. Recent studies reported that cold exposure can also have an important impact on the gut microflora.

3.1 Cold exposure alters the composition of the gut microflora

Researchers found that long-term cold exposure alters the composition of the gut microflora. Cold-exposed mouse fecal microbes showed significant changes in phylum abundance compared to room temperature controls. The Verrucomicrobia phylum was almost eradicated (from 12.5% to 0.003%), and the Bacteroides and Firmicutes phyla became two predominantly flora in the gut microflora[59], within which the proportion of Firmicutes increased from 18.6% to 60.5% while that of Bacteroides decreased from 72.6% to 35.2%, and the ratio Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes increased significantly[11]. These findings are supported by another study based on 16S RNA sequencing of the microflora of rat exposed to 4°C[60].

3.2 Cold exposure affects the function of the gut microflora

3.2.1 Cold exposure increases intestinal absorption capacity

When mammals are exposed in cold, the body undergoes significant physiological adaptive responses, including increased thermogenesis, food intake, and intestinal absorption capacity[10]. The gut microflora after cold exposure is called the cold microflora[11]. Both cold-exposed mice and mice transplanted with cold microbes increased their gut length and weight compared to the control group. Chevalier's team demonstrated that such phenotypic alterations were caused by gut microbes[11].Not only that, after cold exposure, the number of intestinal endocrine cells, the length of intestinal microvilli, and the surface area of intestinal absorption all increased significantly, which explained why the food intake and absorption capacity of cold-exposed mice increased. In addition, the thermal effects of food were mediated by the gut microflora. Researchers restricted the diet of mice eight hours before cold exposure and reduced the gut microbiome by adding broad-spectrum antibiotics to drinking water. In this way, they found that the ability to obtain energy from food and the core body temperature, blood glucose, and body weight of those mice receiving antibiotics were significantly reduced, further illustrating that the gut microflora is a key factor in coordinating the overall energy balance[11].

3.2.2 Cold exposure affects gut microbe phenotypic plasticity

When ambient temperature fluctuates, the gut microflora changes accordingly, indicating the characteristic of phenotypic plasticity that aids the body to better adapt to the external environment without alteration in genetic level[61]. The complex and variable ambient temperature is one of the important factors shaping the formation of the phenotypic plasticity[62]. The phenomenon that the gut microflora changes with the temperature of the external environment may also be one of the internal physiological processes of the body's response to complex living environments. For example, Khakisahneh et al.[63] investigated the impact of varying ambient temperatures (between −47.5°C and 35.3°C per year) on Meriones unguiculatus. They intermittently exposed the Meriones unguiculatus to 37°C, 23°C and 5°C, and found that their intestinal microflora altered significantly to adapt to the external environment. The phylogenetic whole-tree diversity and the Chao1 index were increased significantly in the 5°C group compared to the 37°C group, indicating that the gut microflora increased in both germline and community numbers in response to the changing seasonal environment. However, some specific bacteria, such as Brucella and Lactobacillus, increased their relative abundance at 23°C and 37°C, but not at 5°C. The gut microflora was not only sensitive to environmental temperature, but also showed seasonal physiological plasticity in energy intake, resting metabolic rate (RMR), non-shivering thermogenesis (NST)[63], and modifications of the intestinal immune system[64,65,66,67]. These results suggest that external environmental changes can affect the adaptability of intestinal microorganisms, which can further enhance the adaptability to the environment.

3.2.3 Cold exposure alters the gut microflora to modify the adaptive thermogenesis of adipose tissue

Cold exposure stimulates the browning of white adipose, which is one of the mechanisms by which the body maintains non-chilling thermogenesis, and the gut microflora is involved in this process[68]. The gut microflora of mice was extinguished after antibiotic intervention, and the expression of uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1) was inhibited. Therefore, the adaptive thermogenesis of brown adipose tissue (BAT) and white adipose tissue (WAT) was impaired[68]. Another study yielded similar results that lack of gut microbes impaired UCP1-dependent thermogenesis of adipose tissue in mice subject to cold exposure[69]. Butyric acid produced by Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron is the most important energy substance and the most abundant short-chain fatty acid in the colon[70]. Ramos-Romero et al. measured the proportion of the gut microbes in mice after cold exposure and found that the proportion of Clostridium was higher in the cold exposure group[69]. However, another study published in 2015 drew the opposite conclusion[71]. The authors argued that the depletion of microbes promoted browning of white adipose tissue instead, and that the trend toward browning became more obvious as the depletion of microbes developed over time.

4 Cold exposure regulates glucose and lipid metabolism through other organs and tissues

4.1 Cold exposure regulates glucose and lipid metabolism in the liver

As the main organ for adaptive regulation of metabolism, the liver maintains a stable state of glucose and lipid metabolism. Hepatic glycogen consumption increases during acute cold exposure, and expression of the key enzymes required for hepatic glycogen synthesis increases at the same time[72]. Liver glycogen of rats was depleted in four hours under the −8°C cold exposure condition, and liver edema and other pathological manifestations quickly developed after cold exposure at lower temperatures such as −20°C[73–74]. Liu et al.[75] found that after 0 hour, 2 hours, 4 hours, and 6 hours cold exposure at 4°C, the blood glucose level of C57BL/J mice significantly decreased, while the expression of cold inducible RNA binding protein (CIRP) increased, and the CIRP expression level increased with prolonged duration of cold exposure. The AKT pathway is one of the important regulatory pathways for liver injury protection mechanism[75]. The CIRP regulates liver glucose metabolism in mice through the AKT signaling pathway to maintain hepatocyte energy balance[76]. Glucose metabolism and lipid metabolism in the liver are closely related. Wei et al. studied the effect of cold exposure duration at 4°C on the relevant indicators of liver lipid metabolism and found that cold exposure reduced the content of liver triglycerides and cholesterol, downregulated the expression of liver lipogenesis genes such as fatty acid synthase (FASN), and up-regulated the expression of liver gluconeogenic genes such as Pgc-1α and G6p[77]. However, reports of elevated liver triglyceride levels due to cold exposure are at odds with other results of different cold exposure lengths (4 hours, 24 hours, and 10 days, etc.)[78–79], which may be due to differences in cold exposure conditions or fasting conditions of mice. Taken together, cold exposure leads to accelerated liver glucose metabolism and decelerated lipid metabolism, which may be a protective mechanism against external environmental stimuli.

4.2 Cold exposure regulates glucose and lipid metabolism in adipose tissue

Mammals fight against the loss of heat in cold environments by increasing thermogenesis, and as one of the important tissues for storage and conversion of energy, adipose tissues play an important role in the process of energy metabolism. Adipose tissues typically include white adipose tissue (WAT) and brown adipose tissue (BAT). WAT is an important substance regulating homeostasis of energy by storing energy in the form of triglycerides (TGS), whereas BAT is the main non-shivering thermogenic tissue by breaking down lipids to produce heat, which is mediated by tissue-specific UCP1 in BAT mitochondria[80]. Cold stimulation activates BAT, up-regulates UCP1 expression, increases thermogenesis, and regulates energy expenditure[81]. BAT activation is significantly associated with triglyceride-free fatty acid (FFA) cycling, FFA oxidation, and insulin sensitivity in adipose tissue[82]. At the same time, cold exposure can induce the browning of white adipocyte to beige adipocyte which has similar characteristics and functions to BAT, and the browning of white adipocyte can significantly increase the body energy consumption[83–84]. Activating BAT and promoting WAT browning may be new strategies for the treatment of metabolic diseases. Orava et al. explored the role of BAT in human lipid mobilization and clearance by means of isotopic tracing[85]. The results showed that in BAT compared with in WAT the gene expression associated with lipid metabolism in cold induction was up-regulated, and fat mobilization as well as lipid oxidation was accelerated[85]. In cold stress, the function of thermogenic tissues including BAT are influenced by sympathetic and thyroid hormones, therefore the glucose and lipid metabolisms of BAT are regulated in synergy with the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis (HPT axis)[86].

4.3 Cold exposure regulates glucose and lipid metabolisms in skeletal muscles

Skeletal muscles are an important organ where in active glucose metabolism occurs through decomposing glycogen. Specifically and mechanistically, skeletal muscles regulate glucose metabolism during cold exposure by activating peroxisome proliferator-activator receptor γ coactivator-1α (PGC-1α) which in turn modulates muscle glucose uptake and insulin sensitivity. This process is mediated by the insulin receptors (IR)/serine/threonine kinases (AKT) and AMPK-dependent oxidative phosphorylation signaling pathways[87]. But there are still many controversies as to the overall regulatory pathways involved. Muscle proteins are the most important component of skeletal muscle, and the rate of muscle protein synthesis in rats exposed to cold was significantly reduced, which may explain the decrease in protein quality following long-term cold exposure[88]. Manfredi et al. observed a decrease in the rate of protein synthesis and an increase in the rate of decomposition of the cataracts muscle in mice after 24 hours cold exposure at 4°C. Meanwhile, the sympathetic nervous system was activated, and a sharp increase in plasma glucose, cortisol, and thyroid hormone levels as along with a decrease in plasma insulin levels were also observed[89]. Notably, short-term cold exposure may alter the fatty acid composition of fatty-infiltrating skeletal muscles (intramuscular fat infiltration) by directly affecting the lipid metabolism pathways, including the phosphatidylinositol kinase (PI3K-AKT) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways. For example, saturated fatty acids of mice exposed to 4°C cold for 3 days were reduced by 6.4% compared with counterparts raised at room temperature. Additionally, the expression level of genes associated with fat and energy metabolism including Leptin (Lep), stearyl-CoA desaturase genes 1 (Scd1), uncoupling protein factors 2, 3 (Ucp2, Ucp3) and cytochrome c oxidase 5A (Cox5a) were increased in skeletal muscles. Especially, the myogenic differentiation factor 1 (Myod1), a muscle differentiation marker, was also significantly increased after cold exposure[90]. However, the results from another study showed a 28% reduction of the protein content in gastrocnemius and flounder muscles following 20 days of cold exposure compared to the control group, and there were no significant differences in protein synthesis and degradation index of skeletal muscles in cold-exposed rats, including cold stress (5 days of cold exposure) and cold acclimatization (20 days of cold exposure), compared to control ones kept in normal conditions[91]. The specific causes for the observed alterations in this stress model remain unclear, and the alterations of muscle protein metabolism following cold stress also remain controversial. The signaling pathways regulating the glucose and lipid metabolism processes of skeletal muscles during cold exposure merit further studies.

5 Prospective

In recent years, the incidence of obesity and diabetes has been significantly increasing accompanied by increasing complications, which not only negatively impacts on the quality of life of patients, but also loads heavy burdens to patients’ families and the whole society. This article reviews numerous studies on cold exposure, gut microflora, and glucose and lipid metabolism. Studies have shown that cold stimulation can change the gut microflora and its functionality, thereby regulating the glucose and lipid metabolism. In addition to affecting the gut microflora to regulate the energy homeostasis, cold exposure can also directly activate BAT to improve insulin sensitivity and enhance glucose and lipid metabolism. The gut microflora is one of the endogenous factors for BAT activation. At present, the signaling pathways related to glycolipid metabolism in adipose tissues, muscles and the liver affected by cold exposure are still being extensively studied, and the specific regulatory mechanism needs to be unveiled. It is hoped and anticipated that elucidating the specific regulatory mechanisms underlying glucose and lipid metabolism by the gut microflora, will lay a theoretical foundation for more efficient treatment of metabolic-related diseases such as diabetes and obesity.

Author contributions

The manuscript has been read and approved by all the authors, that the requirements for authorship as stated earlier in this document have been met, and that each author believes that the manuscript represents honest work.

Conflicts of interests

Yang D F is an Editorial Board Member of the journal. The article was subjected to the journal's standard procedures, with peer review handled independently of this member and her research groups.

References

[1] Pulgaron E R, Delamater A M. Obesity and type 2 diabetes in children: epidemiology and treatment. Curr Diab Rep, 2014; 14(8): 508.10.1007/s11892-014-0508-ySearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[2] Abuyassin B, Laher I. Obesity-linked diabetes in the Arab world: a review. East Mediterr Health J, 2015; 21(6): 420–439.10.26719/2015.21.6.420Search in Google Scholar

[3] Bhupathiraju S N, Hu F B. Epidemiology of obesity and diabetes and their cardiovascular complications. Circ Res, 2016; 118(11): 1723–1735.10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306825Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Chobot A, Górowska-Kowolik K, Sokołowska M, et al. Obesity and diabetes-Not only a simple link between two epidemics. Diabetes Metab Res Rev, 2018; 34(7): e3042.10.1002/dmrr.3042Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Martin K, Mcleod E, Periard J, et al. The impact of environmental stress on cognitive performance: A systematic review. Hum Factors, 2019; 61(8): 1205–1246.10.1177/0018720819839817Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Horie M, Miura T, Hirakata S, et al. Comparative analysis of the intestinal flora in type 2 diabetes and nondiabetic mice. Exp Anim, 2017; 66(4): 405–416.10.1538/expanim.17-0021Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Bibbò S, Ianiro G, Giorgio V, et al. The role of diet on gut microbiota composition. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci, 2016; 20(22): 4742–4749.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Morrison D J, Preston T. Formation of short chain fatty acids by the gut microbiota and their impact on human metabolism. Gut microbes, 2016; 7(3): 189–200.10.1080/19490976.2015.1134082Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Gomes A C, Hoffmann C, Mota J F. The human gut microbiota: Metabolism and perspective in obesity. Gut microbes, 2018; 9(4): 308–325.10.1080/19490976.2018.1465157Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] Gomez De La Torre Canny S, Rawls J F. Baby, It's Cold Outside: Host-Microbiota relationships drive temperature adaptations. Cell Host Microbe, 2015; 18(6): 635–636.10.1016/j.chom.2015.11.009Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Chevalier C, Stojanović O, Colin D J, et al. Gut microbiota orchestrates energy homeostasis during cold. Cell, 2015; 163(6): 1360–1374.10.1016/j.cell.2015.11.004Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Zheng J, Zhu T, Wang L, et al. Characterization of gut microbiota in prenatal cold stress offspring rats by 16s rrna sequencing. Animals (Basel), 2020; 10(9): 1619.10.3390/ani10091619Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[13] Sebastián Domingo J J, Sánchez Sánchez C. From the intestinal flora to the microbiome. Rev Esp Enferm Dig, 2018; 110(1): 51–56.10.17235/reed.2017.4947/2017Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Luckey T D. Introduction to intestinal microecology. Am J Clin Nutr, 1972; 25(12): 1292–1294.10.1093/ajcn/25.12.1292Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Yatsunenko T, Rey F E, Manary M J, et al. Human gut microbiome viewed across age and geography. Nature, 2012; 486(7402): 222–227.10.1038/nature11053Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Qin J, Li R, Raes J, et al. A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing. Nature, 2010; 464(7285): 59–65.10.1038/nature08821Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Hooper L V, Dan R L, Macpherson A J. Interactions Between the Microbiota and the Immune System. Science, 2012; 336(6086): 1268–1273.10.1126/science.1223490Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] Cani P D. Crosstalk between the gut microbiota and the endocannabinoid system: impact on the gut barrier function and the adipose tissue. Clin Microbiol Infect, 2012; 18 Suppl 4: 50–53.10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03866.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Holmes E, Li J V, Marchesi J R, et al. Gut microbiota composition and activity in relation to host metabolic phenotype and disease risk. Cell Metab, 2012; 16(5): 559–564.10.1016/j.cmet.2012.10.007Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Cryan J F, Dinan T G. Mind-altering microorganisms: the impact of the gut microbiota on brain and behaviour. Nat Rev Neurosci, 2012; 13(10): 701–712.10.1038/nrn3346Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Leslie J L, Young V B. The rest of the story: the microbiome and gastrointestinal infections. Curr Opin Microbiol, 2015; 23: 121–125.10.1016/j.mib.2014.11.010Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Sonnenburg J L, Bäckhed F. Diet-microbiota interactions as moderators of human metabolism. Nature, 2016; 535(7610): 56–64.10.1038/nature18846Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] Sousa T, Paterson R, Moore V, et al. The gastrointestinal microbiota as a site for the biotransformation of drugs. Int J Pharm, 2008; 363(1–2): 1–25.10.1016/j.ijpharm.2008.07.009Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Ryan A, Kaplan E, Nebel J C, et al. Identification of NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase activity in azoreductases from P. aeruginosa: azoreductases and NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductases belong to the same FMN-dependent superfamily of enzymes. PloS One, 2014; 9(6): e98551.10.1371/journal.pone.0098551Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[25] Martínez-Del Campo A, Bodea S, Hamer H A, et al. Characterization and detection of a widely distributed gene cluster that predicts anaerobic choline utilization by human gut bacteria. mBio, 2015; 6(2): e00042–e00015.10.1128/mBio.00042-15Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[26] Levin B J, Huang Y Y, Peck S C, et al. A prominent glycyl radical enzyme in human gut microbiomes metabolizes trans-4-hydroxy-l-proline. Science, 2017; 355(6325): eaai8386.10.1126/science.aai8386Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[27] Lippert K, Kedenko L, Antonielli L, et al. Gut microbiota dysbiosis associated with glucose metabolism disorders and the metabolic syndrome in older adults. Benef Microbes, 2017; 8(4): 545–556.10.3920/BM2016.0184Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Zhang X, Shen D, Fang Z, et al. Human gut microbiota changes reveal the progression of glucose intolerance. PloS One, 2013; 8(8): e71108.10.1371/journal.pone.0071108Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[29] Cefalu W T, Buse J B, Del Prato S, et al. Beyond metformin: safety considerations in the decision-making process for selecting a second medication for type 2 diabetes management: reflections from a diabetes care editors' expert forum. Diabetes Care, 2014; 37(9): 2647–2659.10.2337/dc14-1395Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[30] Viollet B, Guigas B, Sanz Garcia N, et al. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of metformin: an overview. Clin Sci (Lond), 2012; 122(6): 253–270.10.1042/CS20110386Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[31] Lee H, Ko G. Effect of metformin on metabolic improvement and gut microbiota. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2014; 80(19): 5935–5943.10.1128/AEM.01357-14Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[32] Forsythe P, Bienenstock J, Kunze W A. Vagal pathways for microbiome-brain-gut axis communication. Adv Exp Med Biol, 2014; 817: 115–133.10.1007/978-1-4939-0897-4_5Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] Erny D, Hrabě De Angelis A L, Jaitin D, et al. Host microbiota constantly control maturation and function of microglia in the CNS. Nat Neurosci, 2015; 18(7): 965–977.10.1038/nn.4030Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[34] O'mahony S M, Clarke G, Borre Y E, et al. Serotonin, tryptophan metabolism and the brain-gut-microbiome axis. Behav Brain Res, 2015; 277: 32–48.10.1016/j.bbr.2014.07.027Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Chen X, Eslamfam S, Fang L, et al. Maintenance of Gastrointestinal Glucose Homeostasis by the Gut-Brain Axis. Curr Protein Pept Sci, 2017; 18(6): 541–547.10.2174/1389203717666160627083604Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] Grundy S M. Metabolic syndrome update. Trends Cardiovasc Med, 2016; 26(4): 364–373.10.1016/j.tcm.2015.10.004Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] Katsiki N, Mikhailidis D P, Mantzoros C S. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and dyslipidemia: An update. Metabolism, 2016; 65(8): 1109–1123.10.1016/j.metabol.2016.05.003Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] Schoeler M, Caesar R. Dietary lipids, gut microbiota and lipid metabolism. Rev Endocr Metab Disord, 2019; 20(4): 461–472.10.1007/s11154-019-09512-0Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[39] Quiroga R, Nistal E, Estébanez B, et al. Exercise training modulates the gut microbiota profile and impairs inflammatory signaling pathways in obese children. Exp Mol Med, 2020; 52(7): 1048–1061.10.1038/s12276-020-0459-0Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[40] Velagapudi V R, Hezaveh R, Reigstad C S, et al. The gut microbiota modulates host energy and lipid metabolism in mice. J Lipid Res, 2010; 51(5): 1101–1112.10.1194/jlr.M002774Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[41] Cotillard A, Kennedy S P, Kong L C, et al. Dietary intervention impact on gut microbial gene richness. Nature, 2013; 500(7464): 585–588.10.1038/nature12480Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[42] Le Chatelier E, Nielsen T, Qin J, et al. Richness of human gut microbiome correlates with metabolic markers. Nature, 2013; 500(7464): 541–546.10.1038/nature12506Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[43] Turnbaugh P J, Ley R E, Mahowald M A, et al. An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature, 2006; 444(7122): 1027–1031.10.1038/nature05414Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[44] Den Besten G, Lange K, Havinga R, et al. Gut-derived short-chain fatty acids are vividly assimilated into host carbohydrates and lipids. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol, 2013; 305(12): G900–G910.10.1152/ajpgi.00265.2013Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[45] Kudoh K, Shimizu J, Wada M, et al. Effect of indigestible saccharides on B lymphocyte response of intestinal mucosa and cecal fermentation in rats. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo), 1998; 44(1): 103–112.10.3177/jnsv.44.103Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[46] Kim M, Qie Y, Park J, et al. Gut Microbial Metabolites Fuel Host Antibody Responses. Cell Host Microbe, 2016; 20(2): 202–214.10.1016/j.chom.2016.07.001Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[47] Le Poul E, Loison C, Struyf S, et al. Functional characterization of human receptors for short chain fatty acids and their role in polymorphonuclear cell activation. J Biol Chem, 2003; 278(28): 25481–25489.10.1074/jbc.M301403200Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[48] Bjursell M, Admyre T, Göransson M, et al. Improved glucose control and reduced body fat mass in free fatty acid receptor 2-deficient mice fed a high-fat diet. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab, 2011; 300(1): E211–E220.10.1152/ajpendo.00229.2010Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[49] Lin H V, Frassetto A, Kowalik E J, Jr., et al. Butyrate and propionate protect against diet-induced obesity and regulate gut hormones via free fatty acid receptor 3-independent mechanisms. PloS One, 2012; 7(4): e35240.10.1371/journal.pone.0035240Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[50] Farr S, Taher J, Adeli K. Central nervous system regulation of intestinal lipid and lipoprotein metabolism. Curr Opin Lipidol, 2016; 27(1): 1–7.10.1097/MOL.0000000000000254Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[51] Abdel-Haq R, Schlachetzki J C M, Glass C K, et al. Microbiome-microglia connections via the gut-brain axis. J Exp Med, 2019; 216(1): 41–59.10.1084/jem.20180794Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[52] Ahlman H, Nilsson. The gut as the largest endocrine organ in the body. Ann Oncol, 2001; 12 Suppl 2: S63–S68.10.1093/annonc/12.suppl_2.S63Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[53] Aw W C, Towarnicki S G, Melvin R G, et al. Genotype to phenotype: Diet-by-mitochondrial DNA haplotype interactions drive metabolic flexibility and organismal fitness. PLoS Genet, 2018; 14(11): e1007735.10.1371/journal.pgen.1007735Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[54] Fukuda S, Toh H, Hase K, et al. Bifidobacteria can protect from enteropathogenic infection through production of acetate. Nature, 2011; 469(7331): 543–547.10.1038/nature09646Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[55] Mollica M P, Mattace Raso G, Cavaliere G, et al. Butyrate Regulates Liver Mitochondrial Function, Efficiency, and Dynamics in Insulin-Resistant Obese Mice. Diabetes, 2017; 66(5): 1405–1418.10.2337/db16-0924Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[56] Bach Knudsen K E, Lærke H N, Hedemann M S, et al. Impact of diet-modulated butyrate production on intestinal barrier function and inflammation. Nutrients, 2018; 10(10): 1499.10.3390/nu10101499Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[57] Fillmore N, Jacobs D L, Mills D B, et al. Chronic AMP-activated protein kinase activation and a high-fat diet have an additive effect on mitochondria in rat skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol (1985), 2010; 109(2): 511–520.10.1152/japplphysiol.00126.2010Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[58] Tarapacki P, Jørgensen L B, Sørensen J G, et al. Acclimation, duration and intensity of cold exposure determine the rate of cold stress accumulation and mortality in Drosophila suzukii. J Insect Physiol, 2021; 135: 104323.10.1016/j.jinsphys.2021.104323Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[59] Eckburg P B, Bik E M, Bernstein C N, et al. Diversity of the human intestinal microbial flora. Science, 2005; 308(5728): 1635–1638.10.1126/science.1110591Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[60] Wang B, Liu J, Lei R, et al. Cold exposure, gut microbiota, and hypertension: A mechanistic study. Sci Total Environ, 2022; 833: 155199.10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.155199Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[61] Wang S P, Althoff D M. Phenotypic plasticity facilitates initial colonization of a novel environment. Evolution, 2019; 73(2): 303–316.10.1111/evo.13676Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[62] Westneat D F, Potts L J, Sasser K L, et al. Causes and Consequences of Phenotypic Plasticity in Complex Environments. Trends Ecol Evol, 2019; 34(6): 555–568.10.1016/j.tree.2019.02.010Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[63] Khakisahneh S, Zhang X Y, Nouri Z, et al. Gut microbiota and host thermoregulation in response to ambient temperature fluctuations. mSystems, 2020; 5(5): e00514–e00520.10.1128/mSystems.00514-20Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[64] Kurtz C C, Carey H V. Seasonal changes in the intestinal immune system of hibernating ground squirrels. Dev Comp Immunol, 2007; 31(4): 415–428.10.1016/j.dci.2006.07.003Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[65] Carey H V, Duddleston K N. Animal-microbial symbioses in changing environments. J Therm Biol, 2014; 44: 78–84.10.1016/j.jtherbio.2014.02.015Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[66] Niu Z, Xue H, Jiang Z, et al. Effects of temperature on intestinal microbiota and lipid metabolism in Rana chensinensis tadpoles. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int, 2022 Dec 19. doi: 10.1007/s11356-022-24709-8. Epub ahead of print.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[67] Dill-Mcfarland K A, Neil K L, Zeng A, et al. Hibernation alters the diversity and composition of mucosa-associated bacteria while enhancing antimicrobial defence in the gut of 13-lined ground squirrels. Mol Ecol, 2014; 23(18): 4658–4669.10.1111/mec.12884Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[68] Li B, Li L, Li M, et al. Microbiota depletion impairs thermogenesis of brown adipose tissue and browning of white adipose tissue. Cell Rep, 2019; 26(10): 2720–2737.10.1016/j.celrep.2019.02.015Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[69] Ramos-Romero S, Santocildes G, Piñol-Piñol D, et al. Implication of gut microbiota in the physiology of rats intermittently exposed to cold and hypobaric hypoxia. PloS One, 2020; 15(11): e0240686.10.1371/journal.pone.0240686Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[70] Ferreyra J A, Wu K J, Hryckowian A J, et al. Gut microbiota-produced succinate promotes C. difficile infection after antibiotic treatment or motility disturbance. Cell Host Microbe, 2014; 16(6): 770–777.10.1016/j.chom.2014.11.003Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[71] Suárez-Zamorano N, Fabbiano S, Chevalier C, et al. Microbiota depletion promotes browning of white adipose tissue and reduces obesity. Nat Med, 2015; 21(12): 1497–1501.10.1038/nm.3994Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[72] Wang J, Chen Y, Zhang W, et al. Akt activation protects liver cells from apoptosis in rats during acute cold exposure. Int J Biol Sci, 2013; 9(5): 509–517.10.7150/ijbs.5220Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[73] Meneghini A, Ferreira C, Abreu L C, et al. Cold stress effects on cardiomyocytes nuclear size in rats: light microscopic evaluation. Rev Bras Cir Cardiovasc, 2008; 23(4): 530–533.10.1590/S0102-76382008000400013Search in Google Scholar

[74] Bozkurt A, Ghandour S, Okboy N, et al. Inflammatory response to cold injury in remote organs is reduced by corticotropin-releasing factor. Regul Pept, 2001; 99(2–3): 131–139.10.1016/S0167-0115(01)00239-7Search in Google Scholar

[75] Liu P, Yao R, Shi H, et al. Effects of cold-inducible RNA-binding protein (CIRP) on liver glycolysis during acute cold exposure in C57BL/6 Mice. Int J Mol Sci, 2019; 20(6): 1470.10.3390/ijms20061470Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[76] Leng J, Wang Z, Fu C L, et al. NF-κB and AMPK/PI3K/Akt signaling pathways are involved in the protective effects of Platycodon grandiflorum saponins against acetaminophen-induced acute hepatotoxicity in mice. Phytother Res, 2018; 32(11): 2235–2246.10.1002/ptr.6160Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[77] Wei X, Jia R, Yang Z, et al. NAD(+) /sirtuin metabolism is enhanced in response to cold-induced changes in lipid metabolism in mouse liver. FEBS Lett, 2020; 594(11): 1711–1725.10.1002/1873-3468.13779Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[78] Van Den Beukel J C, Boon M R, Steenbergen J, et al. Cold exposure partially corrects disturbances in lipid metabolism in a male mouse model of glucocorticoid excess. Endocrinology, 2015; 156(11): 4115–4128.10.1210/en.2015-1092Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[79] Grefhorst A, Van Den Beukel J C, Dijk W, et al. Multiple effects of cold exposure on livers of male mice. J Endocrinol, 2018; 238(2): 91–106.10.1530/JOE-18-0076Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[80] Kaisanlahti A, Glumoff T. Browning of white fat: agents and implications for beige adipose tissue to type 2 diabetes. J Physiol Biochem, 2019; 75(1): 1–10.10.1007/s13105-018-0658-5Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[81] Seale P, Lazar M A. Brown fat in humans: turning up the heat on obesity. Diabetes, 2009; 58(7): 1482–1484.10.2337/db09-0622Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[82] Chondronikola M, Volpi E, Børsheim E, et al. Brown adipose tissue activation is linked to distinct systemic effects on lipid metabolism in humans. Cell Metab, 2016; 23(6): 1200–1206.10.1016/j.cmet.2016.04.029Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[83] Sepa-Kishi D M, Ceddia R B. White and beige adipocytes: are they metabolically distinct? Horm Mol Biol Clin Investig, 2018; 33(2): 20180003.10.1515/hmbci-2018-0003Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[84] Jankovic A, Golic I, Markelic M, et al. Two key temporally distinguishable molecular and cellular components of white adipose tissue browning during cold acclimation. J Physiol, 2015; 593(15): 3267–3280.10.1113/JP270805Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[85] Orava J, Nuutila P, Lidell M E, et al. Different metabolic responses of human brown adipose tissue to activation by cold and insulin. Cell metab, 2011; 14(2): 272–279.10.1016/j.cmet.2011.06.012Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[86] Castillo-Campos A, Gutiérrez-Mata A, Charli J L, et al. Chronic stress inhibits hypothalamus-pituitary-thyroid axis and brown adipose tissue responses to acute cold exposure in male rats. J Endocrinol Invest, 2021; 44(4): 713–723.10.1007/s40618-020-01328-zSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[87] Oliveira R L, Ueno M, De Souza C T, et al. Cold-induced PGC-1alpha expression modulates muscle glucose uptake through an insulin receptor/Akt-independent, AMPK-dependent pathway. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab, 2004; 287(4): E686–E695.10.1152/ajpendo.00103.2004Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[88] Samuels S E, Thompson J R, Christopherson R J. Skeletal and cardiac muscle protein turnover during short-term cold exposure and rewarming in young rats. Am J Physiol, 1996; 270(6 Pt 2): R1231–R1239.10.1152/ajpregu.1996.270.6.R1231Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[89] Manfredi L H, Zanon N M, Garófalo M A, et al. Effect of short-term cold exposure on skeletal muscle protein breakdown in rats. J Appl Physiol (1985), 2013; 115(10): 1496–1505.10.1152/japplphysiol.00474.2013Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[90] Xu Z, You W, Chen W, et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing and lipidomics reveal cell and lipid dynamics of fat infiltration in skeletal muscle. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle, 2021; 12(1): 109–129.10.1002/jcsm.12643Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[91] Mcallister T A, Thompson J R, Samuels S E. Skeletal and cardiac muscle protein turnover during cold acclimation in young rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol, 2000; 278(3): R705–R711.10.1152/ajpregu.2000.278.3.R705Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2023 Wanting Wei et al., published by Sciendo

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Perspective

- Computation-aided novel epitope prediction by targeting spike protein's functional dynamics in Omicron

- Review

- Prospects of DNA microarray application in management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A systematic review

- Research progress on adaptive modifications of the gut microflora and regulation of host glucose and lipid metabolism by cold stimulation

- The effect of living environment on developmental disorders in cold regions

- Cold weather and Kashin-Beck disease

- Original Article

- Aminothiols exchange in coronavirus disease 2019

- Pharmacodynamics of frigid zone plant Taxus cuspidata S. et Z. against skin melanin deposition, oxidation, inflammation and allergy

- Growth differentiation factor 11 promotes macrophage polarization towards M2 to attenuate myocardial infarction via inhibiting Notch1 signaling pathway

Articles in the same Issue

- Perspective

- Computation-aided novel epitope prediction by targeting spike protein's functional dynamics in Omicron

- Review

- Prospects of DNA microarray application in management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A systematic review

- Research progress on adaptive modifications of the gut microflora and regulation of host glucose and lipid metabolism by cold stimulation

- The effect of living environment on developmental disorders in cold regions

- Cold weather and Kashin-Beck disease

- Original Article

- Aminothiols exchange in coronavirus disease 2019

- Pharmacodynamics of frigid zone plant Taxus cuspidata S. et Z. against skin melanin deposition, oxidation, inflammation and allergy

- Growth differentiation factor 11 promotes macrophage polarization towards M2 to attenuate myocardial infarction via inhibiting Notch1 signaling pathway