Abstract

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is incurable chronic disease which kills 3.3 million each year worldwide. Number of global cases of COPD is steadily rising alongside with life expectancy, disproportionally hitting middle-income countries like Russia and China, in such conditions, new approaches to the COPD management are desperately needed. DNA microarray technology is a powerful genomic tool that has the potential to uncover underlying COPD biological alteration and brings up revolutionized treatment option to clinicians. We executed systematic review studies of studies published in last 10 years regarding DNA microarray application in COPD management, with complacence to PRISMA criteria and using PubMed and Medline data bases as data source. Out of 920 identified papers, 39 were included in the final analysis. We concluded that Genome-wide expression profiling using DNA microarray technology has great potential in enhancing COPD management. Current studied proofed this method is reliable and possesses many potential applications such as individual at risk of COPD development recognition, early diagnosis of disease, COPD phenotype identification, exacerbation prediction, personalized treatment optioning and prospect of oncogenesis evaluation in patients with COPD. Despite all the proofed benefits of this technology, researchers are still in the early stage of exploring it's potential. Therefore, large clinical trials are still needed to set up standard for DNA microarray techniques usage implementation in COPD management guidelines, subsequently giving opportunity to clinicians for controlling or even eliminating COPD entirely.

1 Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is an expanding global issue for public health. According to World Health Organization, in 2019, COPD caused 3.3 million deaths bringing it up to 3rd place as a cause of death in the overall mortality structure worldwide[1]. Depending on the reports, the total number of cases in 2019 varied from 300 to 600 million cases globally. With an estimated global prevalence of 10.3% among the adult population, COPD disproportionally burdens middle and low-income countries[2,3]. Such countries as Russia and China attribute to at least 65 million cases combined, with a total prevalence of 1.7% and 3.84% respectively[4,5].

Being a long-lasting chronic disease, COPD prevalence differs by age and can reach up to 35% in people aged ≥ 70 years old[4]. Taking into account the growing life expectancy, combined with the high prevalence of risk factors such as smoking and air pollution in the countries with COPD burden, we can assume that mortality, disability, and healthcare spending caused by COPD will rise steadily[6].

Unfortunately, COPD is an incurable disease that can be prevented or discovered in the early stages of development and controlled relatively well with treatment[7]. Due to its complexity and heterogeneity, many studies have been examining COPD molecular mechanisms thus contributing to novel and promising techniques providing better diagnosis, treatment tactics, and prognosis evaluation of COPD. One of such tools is DNA microarray technology, allowing a fast way of individual genome assessment with numerous subsequent applications from personalized treatment options to carcinogenesis evaluation. This method is finding its way into modern standards of COPD management[8]. This study aimed to identify the modern state of application of DNA microarray in COPD management by performing a systematic literature review.

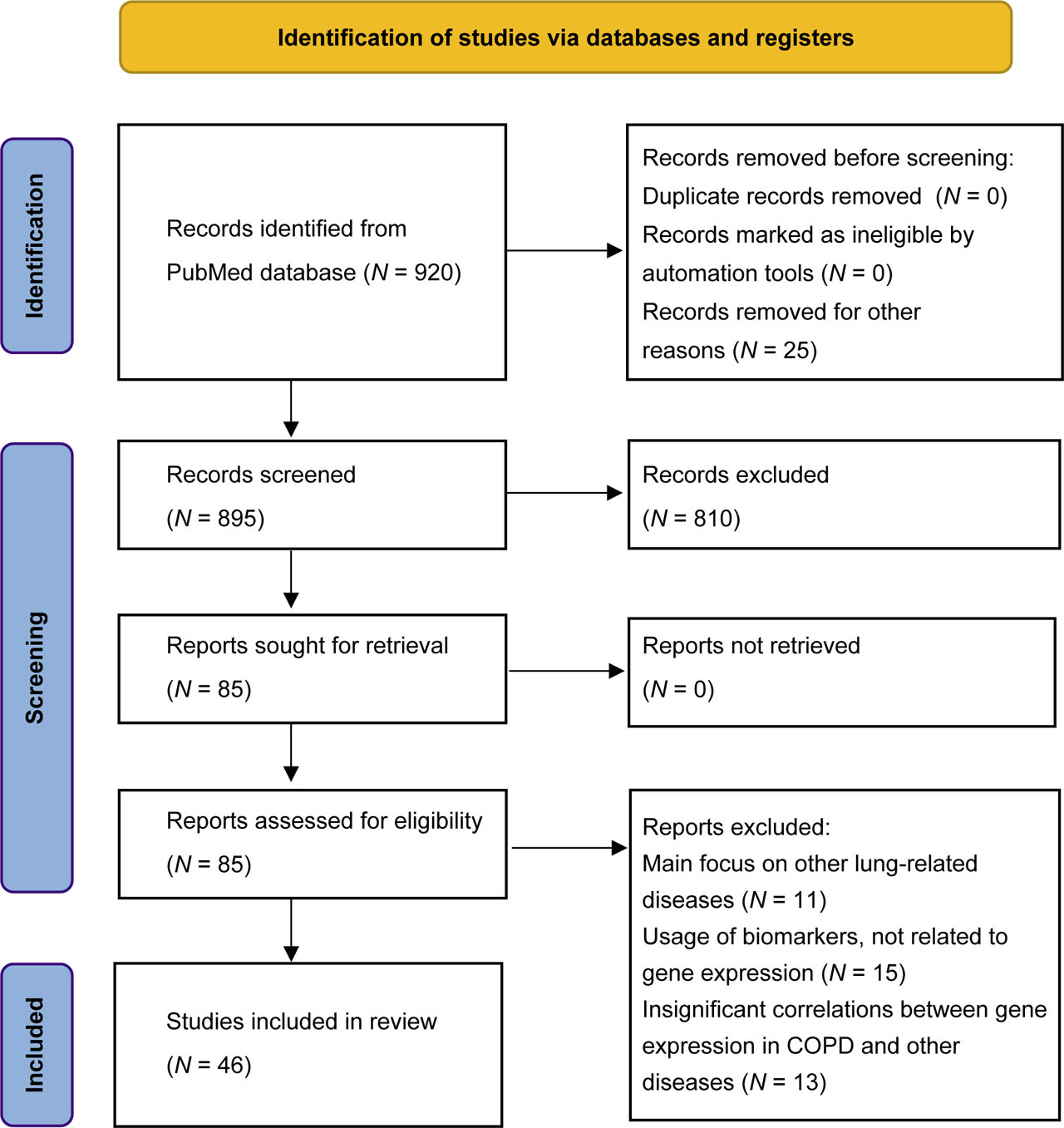

Detailed flow diagram for new systematic reviews

2 Methodology

This study is a systematic review of the most relevant DNA microarray application for COPD management. The search was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews (PRISMA) standard[9]. The search was conducted through the PubMed database, with the period of publication from 1st January, 2011, to 31st December, 2021. The search terms used were “COPD” and “genomic” as a medical subject heading (MeSH) and “gene expression” and “COPD” as text words. The final query for the search was ((“COPD”, “genomic” [MeSH]) OR (“gene expression” AND “COPD”)). In total, 920 studies were identified, which then were screened and reviewed by two researchers separately. The exclusion criteria were as such: (1) Main focus on other lung-related diseases, (2) Usage of biomarkers not related to gene expression, (3) Insignificant correlations between gene expression in COPD and other diseases. The inclusion criteria were as such: (1) Main focus of the study should be COPD or processes directly contributing to COPD development; (2) DNA microarray should be the most prominent biomarker during the course of the study; and (3) Included studies should be original.

After abstracts and titles screening, with the researchers' consensus, 835 articles were excluded according to criteria. The final pool of studies was formed after a full text evaluation of the remaining articles. This resulted in 46 studies, that were approved for further analysis and synthesis of the data according to established criteria.

Quality assessment on the included studies was concluded using the Database of Abstract of Reviews of Effects (DARE) tool[10]. Five criteria consist of: (1) was inclusion/exclusion criteria reported; (2) was the search adequate; (3) was the quality of the included studies assessed; (4) are sufficient details about the individual included studies present and (5) were the included studies synthesized.

3 Result

3.1 DNA microarray basic principles

DNA microarray is a technology used as an aid in the semiquantitative detection of different genes using a collection of probes in a single box. The core of the process is an arrayed series of thousands of spotted DNA oligonucleotides that are bound to surface (e.g., fiber, glass), which complimentarily binds to the congruent DNA material in the probe taken from the patient, subsequently allowing identification of exact genes in the sample. Due to variation in technical execution, we limited our search to the Affymetrix method whenever DNA microarrays were mentioned with one inclusion of the Aglient method.

The most common use for DNA microarrays has been to assess gene expression levels with additional usage of Eberwine amplification processes. This allows the estimation of corresponding gene expression by measuring the intensity of fluorescence of each binding spot[11].

Despite the numerous applications that are available for microarrays, they have a variety of limitations. First, and the most important, is the fact that microarrays provide an indirect measure of relative gene concentration. Second, if there is a certain homology between several target genes, multiple related DNA/RNA sequences will be bound to the same probe on the array. Third, the DNA array can only detect sequences it was designed to detect. If there are no complementary genetic sequences in the solution, they will not be detected. In terms of gene expression profiles, it means that genes that have not yet been discovered will not be present in the result[12]. And finally, DNA microarray does not always accurately display the correlation between expressed gene level and protein level of the gene. Therefore, the usage of protein microarrays could be more beneficial[13].

3.2 Using microarray gene profiles in COPD subtype classification and COPD diagnosis

Due to COPD's complexity and many factors that contribute to its pathogenesis and development, COPD is characterized by a high degree of heterogeneity. While current recommendations for COPD therapy produce satisfying results, molecular subtyping of COPD might revolutionize personalized treatment, predicting corticosteroid responsiveness and identifying exacerbation-prone patients. Therefore, many studies aim to achieve a comprehensive molecular classification of COPD. In this regard, two crucial studies were identified. Both of them were clinical trials that were using non-invasive methods for samples acquisition.

Chang et al.[14] used data from the ECLIPSE study to identify novel and clinically relevant molecular subtypes of COPD[15]. The method of network-based stratification was used to determine cluster-specific gene expression profiles, resulting in four clusters, the first one being the “severely affected”, the second one “moderately affected”, the third one “less preserved lung function”, and the fourth being “more preserved lung function”. Clusters examination was based on the gene profiling data and spirometry measurements. While the clusters differ in lung function impairment, respiratory symptoms, emphysema, and in the most strongly enriched biological processes, there was some overlap in biological process enrichment across clusters. Thus, a blood-based expression signature for COPD was identified that might provide necessary insight into the COPD-associated biological pathways and into specific therapeutic targets as well.

A study by Baines et al.[16] was using sputum to identify 6-gene expression signature (6GS) for predicting inflammatory phenotypes. During the clinical trial, 6GS with all of the genes in combinations was able to partition participants with eosinophilic inflammation from participants without eosinophilic inflammation, as well as participants with neutrophilic inflammation compared with those without it. The same results were obtained after repeating the same design on a larger cohort of patients. Those have shown that the 6GS can distinguish between patients with different inflammatory phenotypes of COPD, with a considerable degree of accuracy and reproducibility.

As could be seen in Table 1, there is little in terms of overlapping genes for a clear diagnosis. Therefore, no clear gene profiling signature has been developed yet, but some promising biomarkers could become the proper diagnostic tool. Winter et al.[24] discovered several genes that are directly correlated with COPD. The focus is on GATA binding protein 2 (GATA2), a receptor tyrosine kinase type III (KIT), and histidine decarboxylase (HDC), which are strongly associated with decreased lung function, while GATA2 plays an important role in macrophages/basophils development and proliferation, which in turn leads to the acute inflammation. There is also a study by Yu et al.[25], that constructs 7 gene signature based on difference analysis and trait module analysis. Over-expression of genes constituting these signatures could indicate onset of pathological processes contributing to COPD; therefore, patients that show high levels of gene signature expression should be under observation. But this data is still needed to be proved in the larger cohort, considering the limitations, including small sample size and different methods that are used in these studies.

Summary of identified potential genes for COPD diagnosis

| Authors | Publication year | DNA microarray platform | Sampling source | Significant genes detected |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bhattacharya et al.[17] | 2011 | Affymetrix | Peripheral blood, lung tissue | RP9, NAPE-PLD, ARID2, STX17, FOXP1, SESN1 |

| Bahr et al.[18] | 2013 | Affymetrix | Peripheral blood, GSE42057 | ASAH1, FOXP1, TLR8, VNN2 |

| Wei et al.[19] | 2015 | Affymetrix | GSE29133 | HMGCS2, FABP6, TAP1, HLA-A, HLA-DOB, HLA-F |

| Boudewijn et al.[20] | 2017 | Affymetrix | Nasal epithelial brushings | NPHP1, CFAP206, CCDC113, MUC1, CREB3L1, DSP |

| Yao et al.[21] | 2019 | Aglient | Peripheral blood | HBEGF, DIO2, CLCN3 |

| Rogers et al.[22] | 2019 | Affymetrix, Aglient | Peripheral blood | DUSP7, GPR15, PLD1, RPS4Y1, FCGR1B, TCF7 |

| Huang et al.[23] | 2019 | Affymetrix | Lung tissue | CX3CR1, PPBP, PTGS2, FPR1, FPR2, VCAM1, S100A12, ARG1, EGR1, CD163, FGG, ORM1, S100A8, S100A9 |

| Yu et al.[24] | 2021 | Affymetrix | Lung tissue | MTHFD2, KANK3, GFPT2, PHLDA1, HS3ST2, FGG, RPS4Y1 |

| Winter et al.[25] | 2021 | Affymetrix | Sputum, peripheral blood | TPSB2, CPA3, KIT, GATA2, SOCS2, ENO2, GPR56, HDC |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Undoubtedly, DNA microarrays could be useful not only for the determination of COPD subtypes but also for early diagnosis.

3.3 Microarray analysis as a prognostic tool in COPD

While the means of certain diagnoses of COPD by noninvasive methods are still under development, the era taking the advantage of the ability to predict COPD severity and progression by DNA-microarray is rapidly approaching t. Research is making rapid progress in identifying gene profiles that could be used to determine the prognosis of COPD. In turn, this could help specialists manage patients with mild or severe COPD better by determining whether or not DNA microarray should be applied in individual case and adjusting treatment and therapy accordingly. Savarimuthu et al.[26] by validating and confirming findings from other studies identified a 8-genes signature of COPD[27,28,29], in which three genes could be the most reliable markers for COPD severity - thrombospondin 1 (THBS1), immunoglobulin heavy constant gamma 1 (IGHD1), and cytochrome B reductase 1 (CYBRD1). Levels of expression for these genes are correlated with moderate and severe COPD (GOLD stage II–III)[30].

By gene expression profiling of the airway epithelium, Steiling et al.[31] were not only able to show that COPD induces a molecular field of injury that affects bronchial airways as well as lung parenchyma, but found a set of 98 genes whose expression was associated with predicted FEV1% and FEV1/forced vital capacity (FVC) reduction following continuous measures. This signature includes dihydropyrimidinase like 3 (DPYSL3), carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 5 (CEACAM5), Sushi repeat containing protein X-linked 2 (SRPX2), and enoyl-CoA delta isomerase 2 (ECI2), which are already been linked to irreversible alteration in the lungs caused by cigarette smoking[32].

Similar results were obtained by Poliska et al.[33] showing that increased expression of C-C motif chemokine receptor 1 (CCR1), growth differentiation factor 15 (GDF15), and solute carrier family 2 member 3 (SLC2A3) in alveolar macrophages and of ADAM metallopeptidase domain 10 (ADAM10), glycerol kinase (GK), interferon developmental regulator 1 (IFRD1), and SEC14 like lipid binding 1 (SEC14L1) in peripheral monocytes were significantly correlated with lower FEV1% values. The data might be useable in monitoring disease progression. It is also possible to use autophagy-related genes as a prognostic marker for COPD. It was demonstrated that autophagy-associated protein levels of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were increased in COPD patients and were correlated with FEV1% predicted values[34]. Sun et al.[35] validated and further expanded the association of autophagy-related genes, such as hypoxia inducible factor 1 subunit alpha (HIF1A), cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor 1A (CDKN1A), BAG cochaperone 3 (BAG3), human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (ERBB2), and autophagy related 16 like 1 (ATG16L1), with the severity and progression of COPD.

Zhang et al.[36], showed that toll like receptor 2 (TLR2) and heme oxygenase 1 (HMOX2) were both significantly associated with immune inflammatory responses, thus involved in the progression of COPD in all stages. It is also known that systemic immune response is associated with Acute Exacerbation of COPD (AECOPD), implying that it could also be indirectly associated with TLR2 and HMOX1 phenotypes.

3.4 COPD exacerbation and ways of its prediction

Preventing AECOPD is the main goal of COPD baseline therapy, and currently, researchers exploring the application of gene expression profiling for exacerbation prediction and frequent exacerbation phenotype detection. The study by Morrow et al.[37] has shown that serum myeloperoxidase (MPO) level could be used for ongoing exacerbation diagnosis as well as for AECOPD prediction. Contrary to the serum level of MPO, sputum and bronchoalveolar lavage samples did not show the same properties. In addition, MPO significance as a biomarker is indirectly confirmed by a longitudinal study where a reduction in MPO level was observed during the treatment of chronic bronchitis[38].

More significant results were obtained by Wu et al.[39] They integrated dynamic bioinformatics with clinical phenotypes and obtained and validated AECOPD-specific biomarkers, including ALAS2, EPB42, and CA1, that were co-differentially expressed in patients with AECOPD. TCF7 was also validated as a prominent biomarker, as it was downregulated by an absolute tenfold in patients with AECOPD phenotype compared with control subjects and patients with stable COPD, proofing significant association between TCF7 and the severity of COPD.

Reliable prediction of the frequent exacerbation phenotype was achieved by Singh et al.[40] A model of three genes (B3GNT, LAF4, and ARHGEF10) was created based on sputum and blood samples obtained from 138 COPD patients in the ECLIPSE cohort. The markers were further tested as a model in the same population, with prediction power for a frequent exacerbation phenotype with a sensitivity of 88% and specificity of 33% without considering exacerbation history in the previous year. When the history was considered, sensitivity and specificity increased to the values of 91% and 81%, respectively, thus allowing us to consider the 3-gene model as a promising biomarker for predicting frequent exacerbation phenotype.

3.5 Novel therapeutic avenues

The main feature of COPD is an inflammatory response, but its underlying pathophysiology responsible for such chronic inflammation is incompletely understood. Therefore, microarray technology could provide not only new targets for therapy, but also deeper understanding of the processes involved in COPD occurrence and progression.

3.6 Corticosteroids

The long-term effect of inhaled corticosteroids on COPD has been reported by several studies with conflicting results. Van den Berge et al.[41] analyzed gene expression profiles of patients before and during treatment with inhaled fluticasone or salmeterol, investigating underlying mechanisms responsible for the effects of long-term corticosteroid therapy. Fluticasone exposure for six months resulted in a gene expression profile that closely correlates with the gene expression profile of non-COPD patients. Moreover, the downregulation of gene expression was significantly associated with a lower rate of decline in FEV1%. These findings suggest that inhaled fluticasone can modify the expression of genes that are involved in COPD progression to improve the quality of life and health status. A study by Lee et al.[42] investigated further the mechanisms that cause corticosteroid treatment effects. Short-term treatment with inhaled corticosteroids resulted in significant down-regulation of genes that are associated with B-cell and Th2-driven immune response. GATA3, which is mainly responsible for naive T-cells differentiation, was down-regulated by nearly twofold after the treatment. Additionally, there was a significant down-regulation of genes associated with mature B-cells activity, such as immunoglobulin encoding genes. Taken together, these results suggest the importance of corticosteroid treatment for a subset of patients with a prominent autoimmune inflammation component.

Glucocorticoids are considered to be the front-line anti-inflammatory treatment for chronic inflammation, however, many patients with COPD show a poor response[43]. Therefore, new targets for treating corticosteroid-resistant COPD phenotypes are needed. Pei et al.[44] by CMap database analysis, found that scopoletin might mitigate steroid resistance based on results of gene expression profiling. The results of treatment with scopoletin showed a decrease in gene expression associated with corticosteroid resistance induced by oxidative stress. Thus, scopoletin may contribute to the reduction of glucocorticoid resistance induced by cystathionine-γ-lyase, although further clinical trials are needed.

3.7 Antibiotic therapy

Another promising option for COPD management is antibiotic therapy. Long-term low-dose azithromycin treatment resulted in downregulation of interferon-stimulated genes, as well as genes involved in immune signaling, as shown by Baines et al.[45].

3.8 Oxygen therapy

Seo et al.[46] suggested long-term oxygen therapy assessment according to the expression levels of arylsulfatase B (ARSB), an oxygen-responsive gene. The results showed that COPD patients with moderate hypoxemia and downregulated ARSB showed increased mitochondrial dysfunction, reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation, and ultimately longer hospitalization and mortality. However, patients receiving oxygen therapy showed increased levels of ARSB, improved survival, and shortened hospitalization length.

3.9 Carcinogenesis in COPD

The association between COPD and lung cancer is well known. Lung cancer is up to five times more likely to occur in smokers with airflow obstruction than in those with normal lung function[47] and about 50%–70% of smokers with lung cancer have pre-existing COPD[48]. Miao et al.[49] suggested the importance of secreted phosphoprotein 1 (SSP1) in the carcinogenesis of COPD. Associated with growth and stage of lung cancer, tumor angiogenesis, and lymph node metastasis as well as with neutrophilic inflammation and emphysema, SPP1 could be viewed as an oncogene. Varying expression levels with significant upregulation in COPD patients and further upregulation in patients with co-existing COPD and lung cancer indirectly confirm this theory. SSP1 could also be considered a therapeutic target for reducing the development of lung cancer in patients with co-existing COPD.

On the other hand, Sun et al.[50] suggest aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family member A1 (ALDH1A1) as a most promising diagnostic biomarker specifically for predicting the risk of developing smoking-related squamous cell carcinoma (SQCC) from COPD. Its high prognostic value was indirectly confirmed by observing a 25.5% decrease of downregulated expression in SQCC cases, so decreased ALDH1A1 expression may promote carcinogenesis[51].

Finally, the study by Zhang et al.[52] aimed to identify genetic signatures that promote non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Among their findings, a panel of 6 genes was discovered that could be considered as a marker for the development and prognosis of NSCLC. Moreover, this panel is involved in the regulation of DNA replication, cell cycle, and mismatch repair, which have a significant role in cancer development. Thus, expression levels of the 6-gene panel could be used as both diagnostic and prognostic markers for the development of NSCLC in COPD patients.

4 Conclusion

COPD remains one of the most prominent global health threats despite all the efforts to develop proper management protocols. Novel strategies are needed, and DNA microarray technology could one of them. Gene expression profiles have been used to identify differences in expression between healthy subjects and COPD patients, providing information about gene signatures used to distinguish molecular subtypes of COPD, improve diagnosis and prognosis, and open novel therapeutic avenues in treating COPD. Gene expression profiles could help identify patient groups benefiting from personalized treatment, and identification of new possible targets for therapy could improve the overall survival and quality of life of patients with COPD.

There are still a lot of setbacks regarding applying DNA microarrays to day-to-day practice. First, cost and requirement for designated equipment make it nearly impossible for widespread usage of this technology. Second, only specific groups of patients require testing with DNA microarrays, and recognizing them among other patients with COPD could be a challenge. Finally, DNA microarray do not guarantee full accuracy.

It is certain that DNA microarrays have a prominent clinical application concerning COPD and could provide desirable tools for clinicians to manage COPD successfully.

Conflicts of interests

All authors declared that they have no conflict of interest.

References

[1] World Health Organization. The top 10 causes of death. 2020. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/the-top-10-causes-of-death. Accessed on 03 March, 2022.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Adeloye D, Song P, Zhu Y, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of, and risk factors for, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in 2019: a systematic review and modelling analysis. Lancet Respir Med, 2022; 10(5): 447–458.10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00511-7Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Szalontai K, Gémes N, Furák J, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: epidemiology, biomarkers, and paving the way to lung cancer. J Clin Med, 2021; 10(13): 2889.10.3390/jcm10132889Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Quan Z, Yan G, Wang Z, et al. Current status and preventive strategies of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in China: a literature review. J Thorac Dis, 2021; 13(6): 3865–3877.10.21037/jtd-20-2051Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Cook S, Eggen A E, Hopstock L A, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in population studies in Russia and Norway: comparison of prevalence, awareness and management. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis, 2021; 16: 1353–1368.10.2147/COPD.S292472Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[6] Fettes L, Bone A E, Etkind S N, et al. Disability in basic activities of daily living is associated with symptom burden in older people with advanced cancer or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a secondary data analysis. J Pain Symptom Manage, 2021; 61(6): 1205–1214.10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.10.012Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Gupta N, Malhotra N, Ish P. GOLD 2021 guidelines for COPD - what's new and why. Adv Respir Med, 2021; 89(3): 344–346.10.5603/ARM.a2021.0015Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Taub F E, DeLeo J M, Thompson E B. Sequential comparative hybridizations analyzed by computerized image processing can identify and quantitate regulated RNAs. DNA, 1983; 2(4): 309–327.10.1089/dna.1983.2.309Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. PRISMA-P Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev, 2015; 4(1): 1.10.1186/2046-4053-4-1Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (UK). Database of abstracts of reviews of effects (DARE): quality-assessed reviews. York (UK): Univeristy of York, 1995.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Van Gelder R N, Von Zastrow M E, Yool A, et al. Amplified RNA synthesized from limited quantities of heterogeneous cDNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1990; 87(5): 1663–1667.10.1073/pnas.87.5.1663Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Brazma A, Hingamp P, Quackenbush J, et al. Minimum information about a microarray experiment(MIAME) - toward standards for microarray data. Nat Genet, 2001; 29(4): 365–371.10.1038/ng1201-365Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Naidu C N Suneetha Y. Current knowledge on microarray technology-an overview. Trop J Pharm Res, 2012; 11(1): 153–164.10.4314/tjpr.v11i1.20Search in Google Scholar

[14] Chang Y, Glass K, Liu Y Y, et al. COPD subtypes identified by network-based clustering of blood gene expression. Genomics, 2016; 107(2–3): 51–58.10.1016/j.ygeno.2016.01.004Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Vestbo J, Anderson W, Coxson H O, et al. Evaluation of COPD longitudinally to identify predictive surrogate end-points (ECLIPSE). Eur Respir J, 2008; 31(4): 869–873.10.1183/09031936.00111707Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Baines K J, Negewo N A, Gibson P G, et al. A Sputum 6 gene expression signature predicts inflammatory phenotypes and future exacerbations of COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis, 2020; 15: 1577–1590.10.2147/COPD.S245519Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Bhattacharya S, Tyagi S, Srisuma S, et al. Peripheral blood gene expression profiles in COPD subjects. J Clin Bioinforma, 2011; 1(1): 12.10.1186/2043-9113-1-12Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] Bahr T M, Hughes G J, Armstrong M, et al. Peripheral blood mononuclear cell gene expression in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol, 2013; 49(2): 316–323.10.1165/rcmb.2012-0230OCSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] Wei L, Xu D, Qian Y, et al Comprehensive analysis of gene-expression profile in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis, 2015; 10: 1103–1109.10.2147/COPD.S68570Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] Boudewijn I M, Faiz A, Steiling K, et al. Nasal gene expression differentiates COPD from controls and overlaps bronchial gene expression. Respir Res, 2017; 18(1): 213.10.1186/s12931-017-0696-5Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[21] Yao Y, Gu Y, Yang M, et al. The Gene expression biomarkers for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and interstitial lung disease. Front Genet, 2019; 10: 1154.10.3389/fgene.2019.01154Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Rogers L R K, Verlinde M, Mias G I. Gene expression microarray public dataset reanalysis in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. PLoS One, 2019; 14(11): e0224750.10.1371/journal.pone.0224750Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] Huang X, Li Y, Guo X, et al. Identification of differentially expressed genes and signaling pathways in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease via bioinformatic analysis. FEBS Open Bio, 2019; 9(11): 1880–1899.10.1002/2211-5463.12719Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[24] Yu H, Guo W, Liu Y, et al. Immune characteristics analysis and transcriptional regulation prediction based on gene signatures of Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis, 2021; 16: 3027–3039.10.2147/COPD.S325328Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[25] Winter N A, Gibson P G, McDonald V M, et al. Sputum gene expression reveals dysregulation of mast cells and basophils in eosinophilic COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis, 2021; 16: 2165–2179.10.2147/COPD.S305380Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[26] Savarimuthu Francis S M, Larsen J E, Pavey S J, et al. Genes and gene ontologies common to airflow obstruction and emphysema in the lungs of patients with COPD. PLoS One, 2011; 6(3): e17442.10.1371/journal.pone.0017442Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[27] Ning W, Li C J, Kaminski N, et al. Comprehensive gene expression profiles reveal pathways related to the pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2004; 101(41): 14895–14900.10.1073/pnas.0401168101Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[28] Wang I M, Stepaniants S, Boie Y,, et al. Gene expression profiling in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and lung cancer. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2008; 177(4): 402–411.10.1164/rccm.200703-390OCSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Bhattacharya S, Srisuma S, Demeo D L, et al. Molecular biomarkers for quantitative and discrete COPD phenotypes. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol, 2009; 40(3): 359–367.10.1165/rcmb.2008-0114OCSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[30] Singh D, Agusti A, Anzueto A, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive lung disease: the GOLD science committee report 2019. Eur Respir J, 2019; 53(5): 1900164.10.1183/13993003.00164-2019Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] Steiling K, van den Berge M, Hijazi K, et al. A dynamic bronchial airway gene expression signature of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and lung function impairment. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2013; 187(9): 933–942.10.1164/rccm.201208-1449OCSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[32] Beane J, Sebastiani P, Liu G, et al. Reversible and permanent effects of tobacco smoke exposure on airway epithelial gene expression. Genome Biol, 2007; 8(9): R201.10.1186/gb-2007-8-9-r201Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] Poliska S, Csanky E, Szanto A, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease-specific gene expression signatures of alveolar macrophages as well as peripheral blood monocytes overlap and correlate with lung function. Respiration, 2011; 81: 499–510.10.1159/000324297Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] Wu Y, Xu B, He X, et al. Correlation between autophagy levels in peripheral blood mononuclear cells and clinical parameters in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Mol Med Rep, 2018; 17(6): 8003–8009.10.3892/mmr.2018.8831Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Sun S, Shen Y, Wang J, et al. Identification and Validation of Autophagy-Related Genes in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis, 2021; 16: 67–78.10.2147/COPD.S288428Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[36] Zhang J, Zhu C, Gao H, et al. Identification of biomarkers associated with clinical severity of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. PeerJ, 2020; 8: e10513.10.7717/peerj.10513Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[37] Morrow J D, Qiu W, Chhabra D, et al. Identifying a gene expression signature of frequent COPD exacerbations in peripheral blood using network methods. BMC Med Genomics, 2015; 8: 1.10.1186/s12920-014-0072-ySearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[38] Gompertz S, O'Brien C, Bayley DL, et al. Changes in bronchial inflammation during acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis. Eur Respir J, 2001; 17(6): 1112–1119.10.1183/09031936.01.99114901Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[39] Wu X, Sun X, Chen C, et al. Dynamic gene expressions of peripheral blood mononuclear cells in patients with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a preliminary study. Crit Care, 2014; 18(6): 508.10.1186/s13054-014-0508-ySearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[40] Singh D, Fox S M, Tal-Singer R, et al. Altered gene expression in blood and sputum in COPD frequent exacerbators in the ECLIPSE cohort. PLoS One, 2014; 9(9): e107381.10.1371/journal.pone.0107381Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[41] Van Den Berge M, Steiling K, Timens W, et al. Airway gene expression in COPD is dynamic with inhaled corticosteroid treatment and reflects biological pathways associated with disease activity. Thorax, 2014; 69(1): 14–23.10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-202878Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[42] Lee J, Machin M, Russell K E, et al. Corticosteroid modulation of immunoglobulin expression and B-cell function in COPD. FASEB J, 2016; 30(5): 2014–2026.10.1096/fj.201500135Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[43] Rossios C, To Y, Osoata G, et al. Corticosteroid insensitivity is reversed by formoterol via phosphoinositide-3-kinase inhibition. Br J Pharmacol, 2012; 167(4): 775–786.10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.01864.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[44] Pei G, Ma N, Chen F, et al. Screening and identification of hub genes in the corticosteroid resistance network in human airway epithelial cells via microarray analysis. Front Pharmacol, 2021; 12: 672065.10.3389/fphar.2021.672065Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[45] Baines K J, Wright T K, Gibson P G, et al. Azithromycin treatment modifies airway and blood gene expression networks in neutrophilic COPD. ERJ Open Res, 2018; 4(4): 00031–2018.10.1183/23120541.00031-2018Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[46] Seo M, Qiu W, Bailey W, et al. Genomics and response to long-term oxygen therapy in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Mol Med (Berl), 2018; 96(12): 1375–1385.10.1007/s00109-018-1708-8Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[47] Young R P, Hopkins R J. Link between COPD and lung cancer. Respir Med, 2010; 104(5): 758–759.10.1016/j.rmed.2009.11.025Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[48] Young R P, Hopkins R J, Christmas T, et al. COPD prevalence is increased in lung cancer, independent of age, sex and smoking history. Eur Respir J, 2009; 34(2): 380–386.10.1183/09031936.00144208Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[49] Miao T W, Xiao W, Du L Y, et al. High expression of SPP1 in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is correlated with increased risk of lung cancer. FEBS Open Bio, 2021; 11(4): 1237–1249.10.1002/2211-5463.13127Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[50] Sun X, Shang J, Wu A, et al. Identification of dynamic signatures associated with smoking-related squamous cell lung cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Cell Mol Med, 2020; 24(2): 1614–1625.10.1111/jcmm.14852Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[51] Okudela K, Woo T, Mitsui H, et al. Downregulation of ALDH1A1 expression in non-small cell lung carcinomas--its clinicopathologic and biological significance. Int J Clin Exp Pathol, 2013; 6(1): 1–12.Search in Google Scholar

[52] Zhang L, Chen J, Yang H, et al. Multiple microarray analyses identify key genes associated with the development of non-small cell lung cancer from Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Cancer, 2021; 12(4): 996–1010.10.7150/jca.51264Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2023 Litvinova Anastasiia et al., published by Sciendo

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Perspective

- Computation-aided novel epitope prediction by targeting spike protein's functional dynamics in Omicron

- Review

- Prospects of DNA microarray application in management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A systematic review

- Research progress on adaptive modifications of the gut microflora and regulation of host glucose and lipid metabolism by cold stimulation

- The effect of living environment on developmental disorders in cold regions

- Cold weather and Kashin-Beck disease

- Original Article

- Aminothiols exchange in coronavirus disease 2019

- Pharmacodynamics of frigid zone plant Taxus cuspidata S. et Z. against skin melanin deposition, oxidation, inflammation and allergy

- Growth differentiation factor 11 promotes macrophage polarization towards M2 to attenuate myocardial infarction via inhibiting Notch1 signaling pathway

Articles in the same Issue

- Perspective

- Computation-aided novel epitope prediction by targeting spike protein's functional dynamics in Omicron

- Review

- Prospects of DNA microarray application in management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A systematic review

- Research progress on adaptive modifications of the gut microflora and regulation of host glucose and lipid metabolism by cold stimulation

- The effect of living environment on developmental disorders in cold regions

- Cold weather and Kashin-Beck disease

- Original Article

- Aminothiols exchange in coronavirus disease 2019

- Pharmacodynamics of frigid zone plant Taxus cuspidata S. et Z. against skin melanin deposition, oxidation, inflammation and allergy

- Growth differentiation factor 11 promotes macrophage polarization towards M2 to attenuate myocardial infarction via inhibiting Notch1 signaling pathway