Abstract

For more than a decade, a global race to recruit nurses from middle-income countries to work in aging, high-income nations has been underway. But very soon, middle-income countries will also face shortages in healthcare personnel. Germany, a country where, by 2040, 9 % of the population will be over 80 years of age and 28 % over 65, has reacted relatively quickly to these developments by establishing, in 2010, a specialized approach for the fair recruitment of nurses from Vietnam and the Philippines called Triple Win. Meanwhile, Indonesia has been actively pursuing new international cooperations beyond its established migration circuits involving several Asian and Arab countries. In 2021, when Indonesia was no longer part of the World Health Organisation safeguard list for healthcare personnel, Germany and Indonesia signed a government to government agreement on nurse recruitment. It contains clear elements of the migration pathways adopted for other Asian countries under this approach. This article analyses the Indonesian case as a relative latecomer in nurse migration towards Europe. It analyses ongoing recruitment under the Triple Win scheme as part of an attempt to formalize Indonesian migration dynamics through bilateral agreements. Although much is known about the functioning of global care chains in general, there is relatively little research on the “making” and design of the care chains themselves, on how institutional dynamics and spatial arrangements shape the migratory process and on how migrant agency shapes the process.

Zusammenfassung

Seit mehr als einem Jahrzehnt findet weltweit ein Wettlauf um die Anwerbung von Pflegekräften aus Ländern mit mittlerem Einkommen für die Arbeit in Ländern mit hohem Einkommen und alternden Bevölkerungen statt. Doch es ist absehbar, dass auch Länder mit mittlerem Einkommen mit einem Engpass an Pflegepersonal konfrontiert sein werden – einige sind es bereits. Deutschland, ein Land, in dem bis 2040 9 % der Bevölkerung über 80 Jahre und 28 % über 65 Jahre alt sein werden, hat relativ früh auf diese weltweite demographische Entwicklung reagiert und rief ab 2010 einen speziellen Ansatz zur Förderung einer fairen Anwerbung von Pflegekräften aus Vietnam und den Philippinen namens „Triple Win“ ins Leben. Indonesien selbst strebte unterdessen aktiv neue internationale Kooperationen mit mehreren asiatischen und arabischen Ländern an. Nachdem Indonesien 2021 von der Safeguardlist der Weltgesundheitsorganisation (WHO) gestrichen worden war, brachten Deutschland und Indonesien eine Vermittlungsabsprache zur Anwerbung von Pflegekräften auf den Weg. Diese Absprache folgte, basierend auf den Erfahrungen mit den anderen beiden Ländern, den Leitlinien einer fairen Anwerbung. Dieser Beitrag konzentriert sich auf den Fall Indonesiens als Nachzügler hinsichtlich der Integration in internationale Migrationsregime im Pflegesektor. Er interpretiert die unterzeichnete Vermittlungsabsprache und das Design der praktischen Umsetzung vor Ort als Teil einer angestrebten Formalisierung des indonesischen Migrationssystems. Zwar liegt umfangreiche Literatur über die Bedeutung und Funktionsweise globaler Dienstleistungsketten im Pflegesektor vor. Es findet sich bislang jedoch kaum Forschung dazu, mittels welcher institutionellen Dynamiken und räumlicher Arrangements die Umsetzung der Vermittlungsabsprachen konkret erfolgt bzw. dazu, wie die Pflegekräfte selbst ihre Einbindung in das Triple Win Programm wahrnehmen. In diese Forschungslücke stößt dieser Beitrag.

1 Introduction[1]

International care migration, including healthcare work, has been part of worldwide migration circuits for centuries. Being “invisible” in practice (as care work mostly takes place in the private sphere), this type of work initially received little attention in mainstream research. Yet, there is now a substantial body of academic literature discussing international nurse and care migration (Abagat 2015; Efendi et al. 2021; Aulenbacher et al. 2024) – referring to a field of work with blurred classifications between “care work” and “nursing”. Existing literature focuses especially on the precarity of the working conditions within the healthcare sector itself. In addition, much of the available literature highlights the inclusion of this care and nursing work into international circuits of labour mobility as an expression of (neo-)colonial heritage. In this context, international nurse migration is analysed as part of global care chains, which reflect spatialized dependencies, increasingly feeding into glocal assemblages of nurse migration (see Hillmann et al. 2022). Other scholars speak of new forms of governance, which have enhanced the formalization of formerly informal work arrangements in migration regimes (Skeldon 2008; Anderson/Ruhs 2013). Many authors interpreted the emerging Global Nurse Care Chains (=GNCC, see also Acker 2006) as an expression of global inequality regimes, underlining that these regimes are tied to various actors on the local, national and global level and that “various private and public actors interact to produce and reinforce GNCCs through on-going transnational recruitment and placement practices” (Näre/Silva 2020: 522). Many authors also call for more empirical research on organizational practises because it is assumed that it is precisely this assemblage of different actors involved that is sustaining or even re-enforcing these dependencies. Such authors point for example to the under-exploration of migration legislation and regulations for educational and language requirements, as well as management practices reinforcing the observed inequality regimes. Based on the case of Filipino nurses migrating to Finland, Näre and Silva (2020) further highlight the compliance of the migrant workers within the system itself.

Precisely because the organization of international nurse migration is tied to a plethora of involved institutions and stakeholders on various geographical levels, it is a contested topic in academia as well as in the political sphere. On a global level, the out-migration of healthcare personnel from countries that already face severe problems in their health sector is seen as a major risk for local development, putting even more stress on the healthcare system and feeding into a global race for migrant workers after the COVID19 pandemics (Triandafyllidou/Yeoh 2023). Accordingly, forms of “care drain” have repeatedly been criticized by international players like the International Labour Organization (ILO). In 2010, ILO published a code of conduct which recommends not to recruit healthcare personnel from selected countries. Despite this, private recruiters stepped up to integrate the increasingly lucrative business of nurse recruitment into their portfolio. At the same time, countries such as Germany pushed forward their agenda on fair migration and followed ILO’s agenda of “decent work”. Our research is positioned in this field of interest.

Germany, being one of the European countries with a rapidly ageing population, reacted to these international calls to foster and better regulate care migration by establishing its own approach to recruitment which would facilitate the recruitment of more nurses from abroad and at the same time could live up to the expectations of “fair migration”. A collection of not always closely connected projects over the past decade under the umbrella term ‘Triple Win’ included a variety of stakeholders at the local and national levels. The approach transformed over time, as did the concepts for its implementation for different countries in Asia (e.g. the Philippines, Vietnam).[2] Indeed, as Indonesia was removed from WHO’s abovementioned safeguard list before 2021, the two countries signed an agreement on the recruitment of workers in the healthcare sector. Former West-Germany had already recruited nurses from Asia under its guest worker regime in the 1970s. Back then, the system was entirely based on the rotation of workers with no perspective for long-term integration into German society. Also former East-Germany, GDR, had invited Vietnamese workers for work and education in their factories and social networks between the two countries continue to exist since that times.

Today, Germany’s Triple Win approach is designed as a holistic concept that claims to offer benefits for the country of origin, the destination country and the migrants themselves (GIZ 2025, Logan et al. 2018). In terms of numbers, the dimensions of Triple Win are rather small compared to the numbers to be found in private recruitment. Yet, we argue that in a world of multilateral cooperation and enhanced global competitiveness for nurse recruitment, bilateral agreements such as this are of special interest for social policy because they also impact many aspects of national policy (to name a few: education and recognition of international degrees, housing policy, social security and the pension system). In the case considered here concerning the relationship between Germany and Indonesia, the two partners sit at opposite ends of the negotiating table in a globally power-laden field characterized by historic inequalities (Walton-Roberts 2022). At one end sits Germany, a global leader, with its approach to establishing standards for fair(er) migration, hoping to address its national worker shortages. At the other end of the table sits Indonesia, a G20 member with a rapidly growing economy, hoping to expand its traditional migration circuits beyond Asia and the Middle East and thus take advantage of a situation in which migration corridors become redefined and the global migration governance system is in transformation. Additionally, the current situation in the healthcare sector in Indonesia is characterized by a high degree of informality, poor working conditions and severe regional disparities (Efendi et al. 2021; Raharto et al. 2023).

Our article focuses on this ongoing development of international nurse recruitment involving Germany and Indonesia. We highlight which actors, institutions and stakeholders have been involved into the recently established agreement and what the migrants themselves think about their trajectories. Our theoretical interest lies in how the design of bilateral migration policies with Europe affects a relative latecomer in formalizing its migration circuits. Our empirical interest is directed towards the design and implementation of Triple Win in Indonesia. Our analysis is guided by the following questions:

Which elements of the Indonesian migration system change with its formalization?

How is the Triple Win approach applied in Indonesia, and how is the process of implementation spelled out on the local scale?

What was the role of the “blueprint” of the Triple Win concept in the Philippines and what does this mean for Indonesia?

How does the Triple Win concept impact the country of origin and the “nurses-to-be”?

The first part of our paper (Section 2) delineates the main theoretical contributions on care, including nurse, migration in the context of the different migration regimes before discussing the code of conduct and fair migration standards set by the WHO. Section 3 explains the methodology of our empirical study. Section 4 introduces the German and Indonesian cases (i.e. the two ends of the negotiating table) as reflected in dynamics and numbers of nurse migration (4.1 and 4.2). We then depict the current setup of the blueprint of the Triple Win approach in the Philippines (4.3). Section 5 presents the dynamics of “nurses on design”, i.e. the process of planned matching, as we observed it in autumn 2023. To better understand how this recruitment process is constructed, we present the perspectives of the experts involved and that of the nurses-to-be at the time. The conclusion brings together our research findings.

2 Theoretical debate

The academic literature on international nurse and care migration spans various research fields because nurse migration is “tethered to geographic hierarchies” (Walton-Roberts 2022: 8, quoting Yeates (2014: 177)), invoking individual as well as structural factors. A transnational perspective is much needed – one that addresses “care [work] as a nested notion that affects society at its various scales: from the intimate sphere of families and households to global labour markets” (Kaspar 2022: 51). This is a daunting task because, at the international level, there is neither a binding definition of who can be classified as a care worker nor much cohesion on the professional definition of a nurse. The working definition of the latter is entirely based on nationally-varying health professional credentials. Accordingly, international healthcare worker migration reflects shifting arrangements of actors and institutions and diverse discourses on care work. Furthermore, healthcare migration is embedded in a transforming field of global social governance and policy concepts (Yeates/Pillinger 2021). At present, we lack codified knowledge about procedures. These circumstances make empirical research challenging.

Much literature on nurse migration focuses on nationally-organized educational frameworks and healthcare systems as well as on the social and legal situation in the associated labour markets (Piper 2008; Kuptsch 2010), often highlighting the sector’s high degree of exploitation, high burnout rates and poor working conditions. Recently, this strand of research has increasingly focused on the deskilling and devaluation of international migrants as a by-product of current nurse migration pathways (Walton-Roberts 2022).

Care work, which is often practised in informal working settings (e.g. in the domestic sphere), was long classified as female unpaid reproductive work, and received little attention in early migration research. Only after feminist research made its way into academia was care work considered a structural part of welfare systems. Now there is an international perspective focused on care work (Pfau-Effinger/Geissler 2005). In addition, migration research studies on Filipino communities abroad paved the way for research on international care migration as linked to multidimensional, power-laden geographies. The now emerging research on global care chains (=GCC) refers to “care drain” rather than “brain drain” and frames care migration within gendered global economic restructuring (Hochschild 2003; Lutz/Palenga-Möllenbeck 2012). In addition, since the 2000s, the male breadwinner model in many Western welfare states started being transformed into the adult worker model, provoking a global crisis of reproduction work (Scheele et al. 2023; Bakker/Silvey 2008). This crisis also touched upon the organization of elder care, which was already in need of more care workers (Theobald 2022).

The blurred boundaries between formal, semi-formal and informal institutions that characterize care migration have been identified as an important pillar of migration systems. Authors such as Chikanda (2022: 182) underline the emerging role of migration intermediaries, partly due to the “impact of market liberalization, which has seen the decentring of stated mobilized services since the late 1980s” having led to privatized and highly fragmented services. Nurse migration was seen as part of a “bifurcated internal migratory system along gender and occupational lines” (Chang 2021), while “continuous undervaluing of nursing and its global commodification” was followed by decentralized, privatized and contracted-out forms of employment for example in Nordic and European welfare states (Näre/Silva 2020: 510). Building on the work of Acker (2006), who introduced the notion of inequality regimes on the global scale by pointing to “loosely interrelated practices, processes, actions and meanings” to maintain existing inequalities in class, gender and race (Acker 2006: 443), Näre and Silva (2020) also claim that such inequalities are perpetuated by means of political and economic practices within the global healthcare industry. Such inequalities are likely to cater to migration industries, which aim at making big business (Nyberg Sørensen/Gammeltoft-Hansen 2013). As a consequence, new glocal arrangements with marked gender differences emerged (Hillmann et al. 2022; Raghuram 2012; Vaittiinen 2014). With digitalization, even more fluid forms of organizing care work are now starting to arise (Schwiter/Steiner 2020), with private players increasingly driving the reorganization of international nurse migration through the implementation of digital-first recruitment models (Tern Group 2025).

Among the broader group of care workers, international nurses are considered professionalized and thus can be regarded as relatively privileged international workers (Hanrieder/Janauschek 2025). Also, Indonesia’s nurse migration policies are highly varied and show limited interaction between its stakeholders (Efendi et al. 2021). If we want to understand the current dynamics of nurse migration from Indonesia, in addition to the international perspective, we should also take a deep dive into the local and regional organization of migration.

Alongside academic research, a vast body of policy-oriented literature has emerged over the past two decades, driven by the mushrooming of NGOs and initiatives in the field of migration governance, with the International Labour Organization (ILO), the WHO, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) and the World Bank taking the lead. Ethical recruitment has become a key policy concept (Yeates/Pillinger (2021). The policy-oriented literature produced by these international institutions reflects the debate on the delicate balance between brain drain, brain gain and migrants’ right to live and work in their country of choice (Shaffer et al. 2022). In addition, multilateral agreements such as the UN Global Compact for Migration, signed in December 2018, recognize the importance of migrant empowerment and its impact on inclusion and stability, specifically highlighting the nurses’ role. The relatively new discussion of more formalized working conditions concurs with a broader discussion on the role of remittances for development in the places of origin – which has increasingly been classified as a benefit for the whole of the country of origin (Asian Development Bank et al. 2024: 32 f.; Gelb 2024).

One outcome of policy-driven knowledge production is that studies like “Health Professional Mobility in the European Union – PROMETHEUS” and “Registered Nurse Forecasting – RN4CAS” have delivered reliable data on the dimensions of international nurse migration for the first time. Also, governments have increasingly promoted the process of fair migration by establishing friendly relations with other governments and institutions with regard to migration issues. Bilateral agreements with other states have been concluded, attracting foreign graduates, tailoring visa and emigration processes, and/or facilitating cross-border mobility of home-educated healthcare professionals (Plotnikova/Adhikari 2023). In sum: it was political and economic pressures, combined with longstanding feminist claims, that urged nations to better manage migration, especially care migration. While some governments introduced drastic measures, such as placing bans or caps on emigration, professional institutions and migration brokers also began to play a greater role in healthcare migration. In this configuration, the WHO consensus has served as a reference point for all players in the field.

In 2010, the WHO adopted its Global Code of Practice on the International Recruitment of Health Care Personnel. A safeguard list named 57 countries at risk of experiencing a “critical shortage” of healthcare workers. Excluding government-to-government (G-to-G) agreements, the declaration called on WHO member states to “discourage active recruitment of health personnel from developing countries facing critical shortages of health workers” (Clemens/Dempster 2021[3]). Indonesia, which had less than 2.23 healthcare workers per 1,000 inhabitants in 2006, was part of that list.

Following the WHO declaration, Germany banned all recruitment from the countries on the safeguard list. Decent work, labour rights and fair migration between WHO member states became a major focus of ongoing policies.[4] A large part of the discussion on fair migration started addressing the formalization of informal work as well as the improvement of employment conditions. The position of recruitment procedures was crucial to this debate. Recruitment costs were high and the market non-transparent, varying across different migration corridors (IOM 2018). The call for more ethical recruitment became louder. Still, attempts to set standards for recruitment agencies and employers and attempts at monitoring and certification had little effect. Existing frameworks were voluntary; a common ethical standard out of sight. Empirical research on the contractual terms of migrant was scarce (Shire 2020: 448).

The next WHO safeguard list, published in 2021 and based on newly-defined criteria, no longer listed India and Indonesia. Germany soon started negotiations with both countries and began establishing migration corridors. To realize these agreements as part of the fair migration that the international organizations were calling for, Germany developed its Triple Win approach (see details below). It was designed to re-establish Germany as an attractive destination for migrant workers in the care sector. With this approach, Germany offered a subsidized and highly formalized procedure to secure high quality working standards for both migrant workers and employers. Triple Win was operated and implemented with the support of state-based agencies, such as the Federal Employment Agency (Bundesagentur für Arbeit, or BA) and the German Agency for International Cooperation (GIZ) as well as the BA’s specialized department “International and Specialized Services” (Zentrale Auslands- und Fachvermittlung, ZAV). Critics of the Triple Win approach speak of the paradox of “liberal extractivism”: on the one hand, Germany protects (however imperfectly) individual worker mobility and rights. But on the other hand, as Hanrieder and Janauschek (2025) conclude, the approach “disregards collective social rights, and the right to development”. When taking a closer look at the intentions and the implementation of this approach to fair migration, the question arises whether this perception reflects what the benefits for the involved stakeholders are. Fair migration is a big word, boiling it down to practice and implementation is an ambitious task because already the design of the approach is tied to very different players with contrasting interests.

3 Methodology

To shed light on the design of the Triple Win approach in Indonesia, we started with an analysis of (available) relevant documents and literature (e.g. national laws and regulations related to Asian migration to Germany), as well as online resources and statistics on migration dynamics. Codified knowledge in the field is rare and often not available for public use since it is mostly stored in internal documents of the participating institutions. We conducted a set of expert interviews between September and November 2023 with Triple Win partners in Indonesia (n=8) and included a sample on the blueprint of the concept as it was realized in the Philippines (n=8). In addition to these 16 semi-structured expert interviews, we organized group interviews and attended roundtables (four in total, three in Indonesia and one in the Philippines). The analytical focus of the expert interviews lay on migration governance and the implementation of Triple Win in Indonesia. The interviews in the Philippines were used to better understand the design of the Indonesian case. All interviews were conducted in co-presence of a German and Indonesian native speaker. Lastly, qualitative, semi-structured narrative interviews with “nurses-to-be” who volunteered to join our research sample were conducted in Indonesia, either in person or via Zoom (n = 6). These interviews helped us to gain insights into the motivations and obligations of the candidates in the Triple Win programme. These interviews were conducted in Bahasa Indonesia to allow for and invite critique and free speech. All interviews were recorded, transcribed and coded. All ethical standards of research in this sensitive field were respected. The next section outlines our findings regarding the evolution of the two countries’ migration systems.

4 Positioned at different ends of migration regimes

4.1 The destination country: Dynamics of Asian nurse recruitment to Germany

Former West-Germany had bilateral agreements to recruit nurses under its guest worker regime in the 1960s and 1970s (Lauxen et al. 2019). Between 1966 and 1977, about 10,000 to 12,000 Korean nurses were officially recruited to work in Germany (Kim 2023). There was a much lower number of nurses from the Philippines; Mosuela (2023: 109) reports that a total of 3,425 nurses from the Philippines were recruited for work in Germany in the period between 1969 and 1973. Since the 1970s, care migration to Germany continued, but the recruitment involved mostly circular migration from Eastern European countries to Western Europe. It was only after 2012 that Germany actively resumed recruitment of care workers from Asia, e.g. from the Philippines and Vietnam.

The composition of nurses from abroad who came to work in Germany

Estimates of the current need for additional workers in the German healthcare sector may vary, but they generally reflect a shortage of qualified workers. Existing data for Germany is fragmented along the lines of Germany’s federal system, based on its Länder (states). Also, the fluctuation of workers in the healthcare sector itself is reported to be high: The sector is characterized by high turnover (Kordes et al. 2020) and systematic monitoring of why migrant workers leave the sector is unavailable for Germany (Lauxen et al. 2019). This shortage of personnel can be explained by the economisation of the German health system since the early 2010s, which led to a successive deterioration in working conditions, lower wages and reductions in patient-to-staff ratios. Demographic change and a shrinking workforce due to an ageing society add to the existing pressure in the sector.

Dynamics and numbers

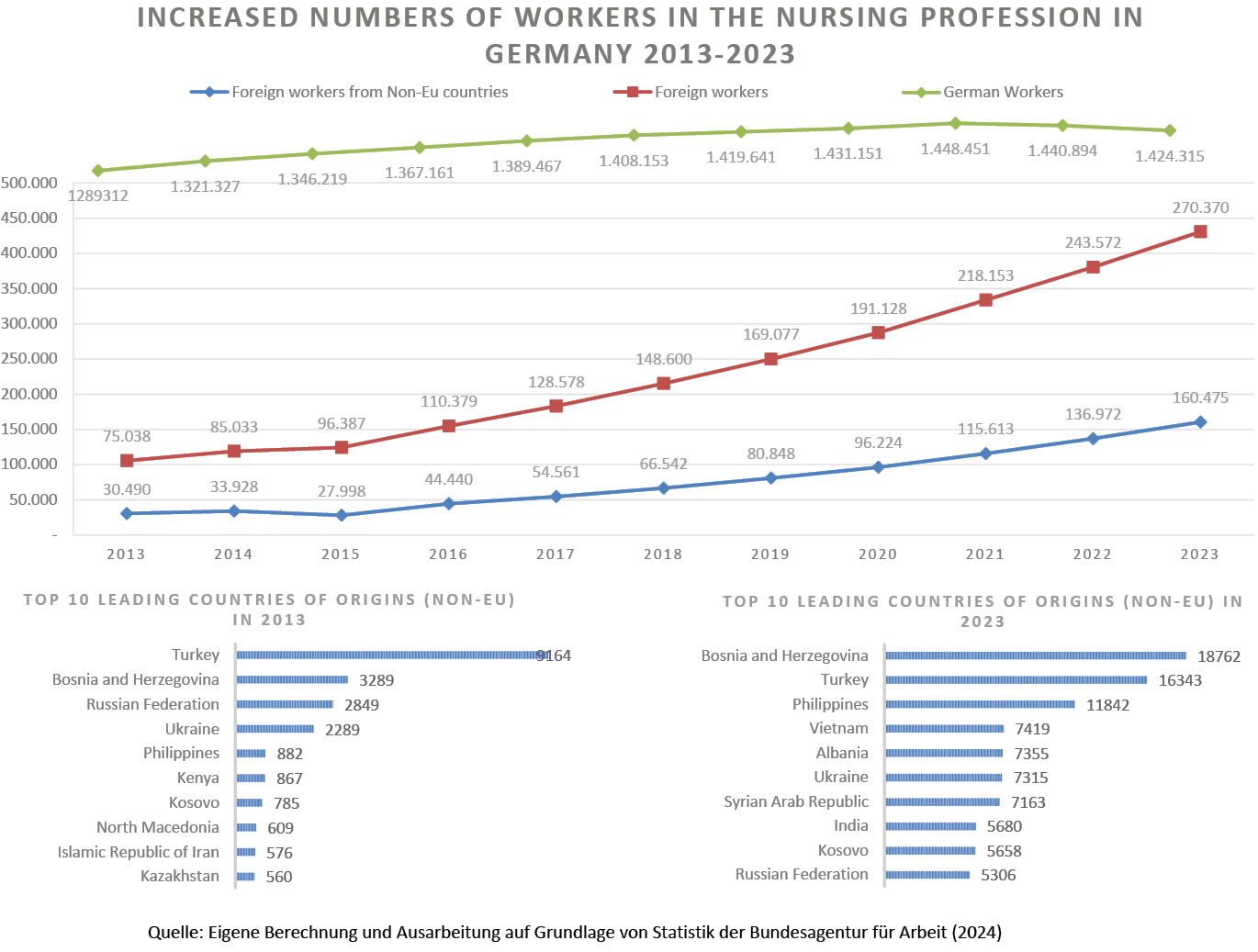

For many years, Germany was able to satisfy its need for healthcare personnel by recruiting workers from EU and non-EU European states (see Figure 1). From 2016 onwards, international recruitment patterns changed and an increasing number of healthcare workers from non-EU countries were incorporated into the sector. Germany started to attract workers based on bilateral labour agreements and various types of recruitment (e.g., the Western Balkans Regulation [Westbalkanregelung]).

The recruitment of nurses under the Triple Win umbrella worked as an essential element of a more comprehensive, but still fragmented strategy. Today, several initiatives have established training and educational programmes and have tried to implement German-style vocational training programmes in partner countries (see Hillmann/Handayani 2024).

The Triple Win approach in Germany

In the early 2010s, private recruitment agencies had already started to recruit care workers by concluding individual contracts with employees. Back then, no accreditation was required for recruitment agencies, leaving individual workers with high responsibilities, costs and risks for their migratory pathways – with brokerage fees of up to 10 monthly salaries (IOM 2018). Repeatedly, private placement agencies promised to reduce the high transaction costs for both employers and the nurses. Germany’s Triple-Win approach sought to subsidize these transaction costs (Kordes et al. 2020). Indeed, in 2023, less than 10,000 nurses had arrived via the Triple Win activities (Heuke 2023). Although these numbers are relatively low, the concept was serving as a “trailblazer”, opening up the labour market for more private recruitment from the selected countries on purpose. It must be mentioned here that the Triple Win activities took place alongside various attempts of the Federal Agency to function as a provider and gatekeeper for the recruitment of international workforce. While the partners benefitting from the programme were mostly content with it, many private stakeholders in the field considered Triple Win too lengthy, too costly and not sufficiently transparent for the recruitment of large numbers of international nurses. Some employers said the subsidies would undermine the free market and that the approach was hardly scalable.

4.2 Indonesia: Joining international circuits

During the period of Indonesian independence from 1949 until the Suharto period (1966–1998), the government was not involved in the placement of Indonesian workers abroad (Missbach/Palmer 2018). Such placements were primarily based on private relationships and organized within social networks. Government policy in this area was established from the 1970s onwards. From then on, the placement of migrant workers also involved private companies while temporary labour migration became an increasingly attractive strategy for the government to reduce labour surpluses and unemployment at home. Given the high labour demand in the domestic and care sectors in destination countries such as Saudi Arabia, women were overrepresented among Indonesian migrant workers, with intergenerational and intrafamily relationships guiding the female migrants’ decision-making. The women mostly came from agricultural regions and had relatively low levels of formal education (Hugo 2002: 17). That being said, informality in the sector was instrumental: it facilitated the kefala system, whereby workers were bound to their employers and denied workers’ rights, leaving them particularly vulnerable on purpose (Farbenblum et al. 2013, see also Parreñas/Silvey 2021). As a consequence, high levels of exploitation and abuse occurred.

In 2006, the Indonesian government began implementing G-to-G (intergovernmental) agreements to send migrant workers to South Korea. Economic instability, limited career opportunities and inadequate working conditions at home fuelled international emigration (Pradipta et al. 2023). Nonetheless, the employment of nurses abroad occurred in the “grey area as to whether it should be centralised or decentralised” (Bachtiar 2011: 22). A network of service centres, located at the provincial and municipal levels (BNP2TKI),[5] were identified to handle G-to-G deployment in terms of placement (Bachtiar 2011). In autumn 2023, when we were conducting our empirical research and the formalization of the migration system was just in the making, the Indonesian Migrant Workers Protection Agency (Badan Perlingundan Perkerja Migran Indonesia, or BP2MI) oversaw the protection and placement of migrant workers, and the Ministry for Manpower was responsible for the regulation of migration. Meanwhile, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs was responsible for the protection of Indonesian citizens abroad more generally.

This making of a more formalized migration origin country not only required and still requires new regulatory bodies and agreements, but also fresh narratives on the migration process itself. Due to its largely informal and exploitative nature, most of the Indonesian population generally did not perceive migration as beneficial. Accordingly, BP2MI (Badan Perlingundan Perkerja Migran Indonesia) launched a campaign to bolster the image of the migrant as a positive figure:

The institution started to resocialize an old notion: that of the ‘devisa hero’ – who is somebody who brings in currency for the city. But that was a difficult notion as somebody who works like stupid for twelve hours a day and brings back money for the city and we see him/her as a hero – this is difficult. So, there is an attempt to give a new connotation to migrant work, for example by speaking of ‘Indonesian Migrant Workers – The City Official Team’. (Interview partner M)

As part of this image campaign, BP2MI established the Indonesian Migrant Worker Award in 2021. Further, “Indonesian migrant worker” (Pekerja Migran Indonesia) replaced the term “TKW” (Tenaga Kerja Wanita, female worker). In addition, the first Indonesian Diaspora Congress was organized in 2012 by the Indonesian Ambassador to the United States in Los Angeles. The situation of Indonesian domestic workers increasingly came into focus. A new social fund specifically for the protection of migrant workers, the Dana Konpensasi Warga, was introduced in late 2023 (Hillmann/Handayani 2024: 49).

Within the country itself, attitudes towards youth leaving the country shifted. To start with, ceremonies praising the courage and innovative mindset of the departing citizens were organized. For example, at a ceremony held for the first 84 nurses sent to Germany, the coordinator of European recruitment noted that although sending nurses to Germany had long been perceived as impossible, the goal had been reached in terms of the numbers and strategy. She stated that the “European heartland had been successfully conquered” and that “our nurse friends” had made it to work there. She added that the trust of the German government towards receiving the Indonesian nurses should be kept and that the agreement should be broadened. The director of the Indonesian Service Centre for the Security of Migrants (BP3MI, the local sub-authority of BP2MI) at the same event further stressed that this development proved Indonesian human capital to be able to compete with that of other countries and that the country’s educational standards were in line with international standards for the healthcare sector.[6]

Gradually, the vision of the “global citizen” from Indonesia, a recurring narrative among young Indonesians (Interview M), took shape. Today, one of those global citizens is Bunda Corla, a transgender person from Bandung who lives in Germany and has 5.5 million online followers (Ginting 2022).

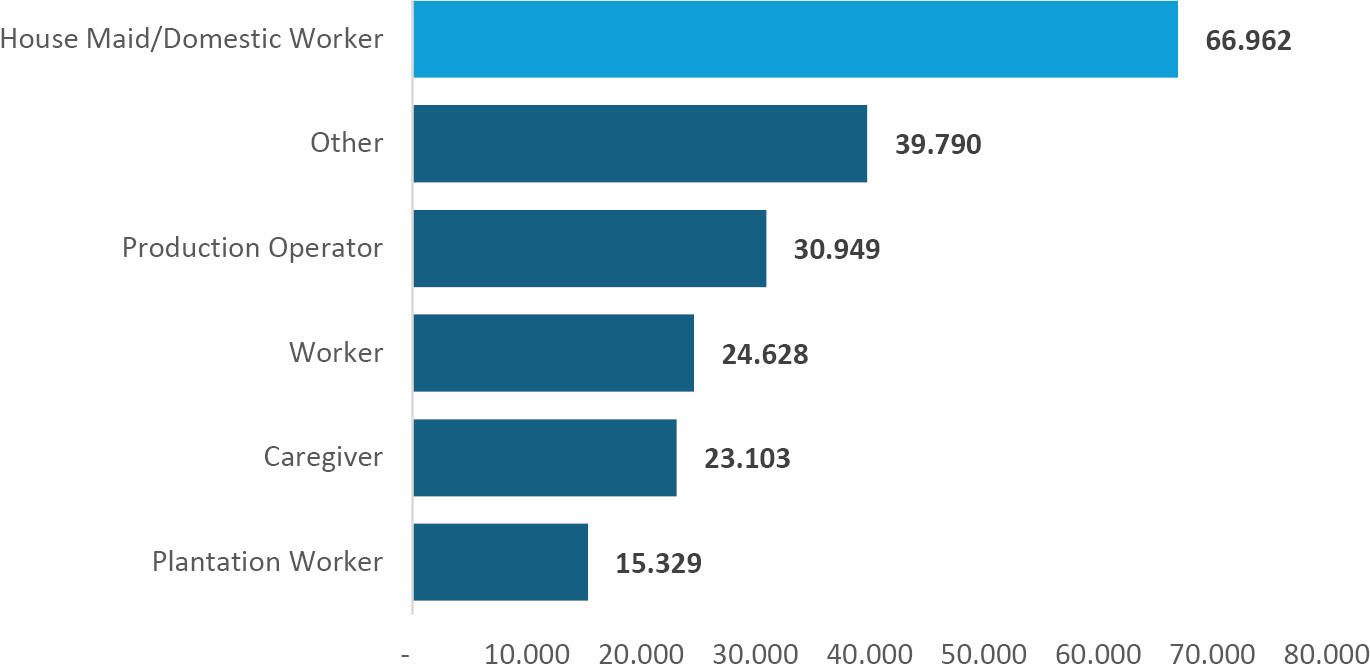

Occupations of documented Indonesian migrant workers in destination countries (2022)

Source: BP2MI, Government of Indonesia, 2022, Graph: Intan Hapsari

Current dynamics and numbers

Generally, Indonesia is the 14th largest source of migrant workers in the world (IOM 2022) and the second largest in Southeast Asia, after the Philippines. In 2017, more than 9 million Indonesian migrant workers lived abroad (corresponding to 7 % of Indonesia’s total labour force), of which 5 million were thought to be undocumented (IOM 2023, Jakarta). Recent data on labour migration from Indonesia show a steep increase of 37 % from 2022 to 2023, reaching a total number of 275,000 workers, but not reaching pre-pandemic levels (in 2012 and 2013 the annual outflow was around 500,000 workers). In 2021, a record 88 % of the outflow of workers from Indonesia were women (Asian Development Bank et al. 2024: 6). Data from BP2MI show that a large share of the migrant workers are active in the field of care work, as housemaids or domestic workers (see Graph 1).

Official data on the registered placement of Indonesian migrant workers show that female migrants outnumber male migrants in the decade between 2012 and 2022 (IOM). In 2022, registered migrants were primarily high school graduates. Primary destinations for Indonesian migrant workers were Hong Kong, Taiwan and Malaysia.

Economic factors drive Indonesia’s migration dynamics in the healthcare sector. Existing literature points to workers that travel abroad to gain work experience, improve their skills and acquire better career development opportunities. At the same time, the number of nursing school graduates in Indonesia has long exceeded national needs and produces a surplus of workers (Raharto/Noveria 2023). The availability of nurses nationwide further increased as the number of nurses assessed as competent to practice nursing (surat tanda registrasi [STR], valid for 5 years) climbed to 985,889 in 2020, so the authors state. Less than half of those assessed were working in hospitals, public health centres (puskesmas) or other health facilities. The majority were likely working in fields unrelated to the health sector or unemployed. The estimated nursing staff surplus of 695,217 people in 2025 will be distributed unequally across the national territory and the corresponding health centres (Puskesmas Pusat Kesehatan Masyarakat), thus cementing current regional inequalities. Between 2015 and 2020, only a total of 6,393 nurses worked abroad (Raharto/Noveria 2023).

The Triple Win approach in Indonesia

Initially, recruitment of Indonesian nurses was dominated by private agencies. Starting in 1996, Indonesian nurses were deployed to work in the United Arab Emirates, the Netherlands, Kuwait, the United Kingdom and Saudi Arabia, among other countries (Raharto/Noveria 2023). The government scheme started in 2008, based on a bilateral agreement with Japan under the Indonesia–Japan Economic Partnership Agreement (IJEPA) and was followed by Timor Leste (Raharto/Noveria 2023: 107). Until recently, the main destination countries for female nurses and caregivers were Japan, Malaysia, Singapore, as well as Taiwan, Hong Kong and Saudi Arabia. Qatar and Bahrain were also mentioned in our interviews as destination countries without having formal agreements.

Indonesia is permitted to send nurses to Germany as long as they meet the Triple Win requirements and the applicants pass the selection process. The implementation of Triple Win is based on an agreement between the German Federal Employment Agency (BA) and the BP2MI, the Indonesian institution which regulates the procedures, selection and placement of nursing professionals, including document verification, an interview and an assessment of German language skills. In collaboration with the BA, the German Agency for International Cooperation (GIZ) provides support for both the partner administration in Indonesia and the nurses. Representatives of the BA and GIZ conduct online interviews to select the applicants.

Once the participants arrive in Germany as assistant nurses, they receive German language training up to level B2 as well as nursing training in order to qualify as full nurses. Their salary, which is based on the work agreement between the two countries, is initially around IDR 25–30 million and increases once they become full nurses. The participants acquire a minimum extendable contract of three years that enables them to bring their families to Germany (Interview N).

Our interviews revealed that Indonesia had the capacity to send 200 nurses and carers to Germany in 2022 and a group of 600 in 2023. Each month, about 5 nurses departed for Germany. In 2022, 76 out of the 200 nurses originally selected had left for Germany in so called “batches” (interview partners spoke of “batch” 2, as if the applicants were stacked goods). “Batches” 3 and 4 planned for about 600 nurses, of which 169 were already in training. The next call for registration remained open while we were conducting our interviews (289 registrants in “batch” 4) (Interview D).

Our interview partners repeatedly said that the execution of the Triple Win programme in the Philippines served as a blueprint for the development of the strategy in Indonesia. The stronger bi-lateral entanglement of educational schemes as well as language schemes were part of the plan, an MOU (Memorandum of understanding) was signed. Although the programme was well planned, experts described its overall mode as a “muddling through” approach: “The setup is totally different because we signed the MOU and we just started right away. It’s more like figuring things out as we went along” (Interview D).

4.3 The Philippine blueprint

As was the case in Indonesia, Germany was not seen as a top destination for Filipino migrant workers, and just a few informal networks between the two countries existed in the early 2010s. For the whole of the country, only two universities offered a German language programme.

The Triple Win concept was first adopted in 2013. The quality standards were high. It included different elements along the pathway: there were no placement fees, the employer covered the largest share of the pre-deployment expenses, a free flight ticket to the destination country was included, and there were no costs for the medical exam. The employer also paid for six months of language training. All elements were refinanced by state subsidies and involved minimal costs for the migrating nurses. A major outcome of Triple Win is that, as of 2023, 5 out of 26 recruitment agencies in the Philippines recruit directly to Germany using a similar approach. One of our interview partners estimates that 2,300 of the 8,000 nurses recruited to Germany from the Philippines arrived through Triple Win, less than a third of all Filipino nurses in Germany. While the programme started with 2,000–3,000 applicants per year in 2015 and 2016, the numbers later decreased, and the pandemic lowered the number of applicants even further (Interview Q). There is now relatively limited interest in the programme:

Triple Win in the Philippines now is not that successful. They are having quite a lot of problems in recruiting skilled or nurses. […] At the moment we have two [language] courses [instead of 5 or 6]. So and then of course the sales of [courses for] Level A1 and then going until B1 go down. (Interview F)

Our interview partners noted that, in the face of international competition, Germany could offer neither the highest pay nor the best working conditions upon arrival, even though the country’s recruitment model was promising. Consequently, as the GIZ experts report, the GIZ managers in the Philippines started travelling to the countryside to develop promotional activities in cooperation with other partners.

5 Matching: The design and implementation of Triple Win in Indonesia

5.1 The institutional actors and the process

The matching process between Indonesian nurses and German employers turned out to be complicated because it involved various state and semi-state stakeholders without clearly defined competences and responsibilities. Alongside the organization of language training, networking among the different stakeholders was pivotal for the realization of nurse recruitment under the Triple Win umbrella. At the time of our research, local institutions slowly began to adapt their curricula. Language training in particular seemed to be simultaneously a bottleneck and a facilitator. The contract for language training was mostly stipulated with the Goethe-Institut, as it offered the highest quality of teaching and training through pre-integration courses and intercultural training. The structure of the courses was designed to meet precisely the needs of the German labour employers. In the design of the courses the Goethe Institutes were obliged to follow the instructions of GIZ.

How was the programme organized locally? The Triple Win applicants in our sample participated in partially-funded German language courses until the B1 level exam (= basic understanding of everyday life topics). If the students failed the exam, they had to retake it out of their own pocket. The duration of the German language training was around 5 months and one week (Level A1: 2 months, Level A2: 2 months, Level B1: 5 weeks), the conditions changed with the different cohorts. In 2023, the number of people failing the examination was around 40 %, having increased in that year. The experts explained the high failure rates with the fact that the nurses-to-be already worked full-time while studying.

Additionally, programme participants did not receive financial support to cover living expenses during the training period in Jakarta – meaning that students from remote areas were at a disadvantage. Those who lived in peripheral areas were invited to make use of newly designed digital classes, introduced during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, most of the digital participants did not possess the necessary hardware and had to rely on tablets or mobile phones with no stable internet connection.

In October 2023, the long-awaited plan to establish a proper training centre for skilled recruitment was underway in collaboration with a Goethe-Institut site in Jakarta. Apart from offering language training, the Goethe-Institut in Jakarta served as a meeting point for the German partner institutions linked to the Triple Win. The partners met frequently to design a competence centre for skilled migration, identifying West Java as the area from which most workers emigrated. Accordingly, the city of Bandung was chosen as the location for the new centre. In our interviews, local Indonesian partners of the Triple Win programme criticized the decision, arguing that their opinions on the matter had been disregarded (Interview M). Nonetheless, the centre finally opened in Bandung in June 2025.

After all, the Goethe-Institute has - indipendently from the activities of GIZ – opened up the competence center for skilled migration – within the Goethe-institute in Bandung, focusing on internal trainings and the development of teaching materials. Also, GIZ decided to open up the project “Move ID/Zentren für Migration und Entwicklung” in Indonesia – as it’s own approach. The two projects Triple Win and ZME follow different trajectories: while Triple Win is part of International Services and considered to be a profit-oriented program, ZME is a project which is funded by the German ministry for international cooperation and has a focus on capacity building. As these projects with its different project logics are implemented in the same place, they are easily mixed up.

On top of this re-organization of the language training offered by the Goethe-Institut, German language training was further integrated into the Indonesian educational system. Two pilot classes in Jakarta were planned to extend to 38 selected polytechnic schools offering vocational training for nurses. It was also intended to include German language training in future international classes, which had, until that point, primarily focused on teaching units in English (60 % in English, 40 % in Bahasa Indonesia). Generally, these international classes were part of the overall internationalization strategy of the Indonesian educational system. However, international classes hold both high prestige and high costs for the students, indicating a social bias in the selection of people able to benefit from German language classes.

Alongside the Goethe-Institut, Indonesian state institutions were involved in the preparation for recruitment. In 2022, government ministries asked the polytechnical institutes in selected regencies to guarantee education for the required healthcare personnel, delegating the realization of this political intention to different educational institutions in Java: “Our minister said that Semarang has to prepare to increase the number of nurses who go to Germany” (Interview S).

The regional affiliation was decided top-down by the Federal Ministry of Health, but these decisions were not linked formally to the Triple Win activities. The city of Semarang was selected for the future “German” nurses, while a study programme in Blora was dedicated to students heading for Japan, a programme in Pekalongan prepared students for the Netherlands and a programme in Purwokerto prepared students for Saudi Arabia (Interview S). Three polytechnical institutes in Java were selected to prepare students for Germany: Semarang, Jakarta 3, and Bandung. As there is no Goethe-Institut in Semarang, the language training and other travel preparations conducted with the help of two private agencies – as our interview partner stated on request.

Specifically, the polytechnic institute in Semarang was preparing to open international classes, especially for students heading to Germany. At that institute, students already had the opportunity to go to Japan, the Netherlands and Saudi Arabia. International classes had been introduced in 2016; three classes were conducted each year with approximately 30 students each. In early November 2023, 20 lecturers at the polytechnic joined the German language courses. The language courses were prepared not only for the students but also for the lecturers, who took classes 3 times a week for 1.5 hours per session (Interview S). The expert from the polytechnic in Semarang described the same problems faced by the Goethe-Institut in Jakarta: it was nearly impossible to find native speakers with didactic skills to instruct the students willing to learn German to an acceptable quality level.

While the government representatives were relatively optimistic about the numbers of people ready to go to Germany, the local vocational schools were more sceptical:

When we talk about this to the students, or maybe graduated students, only some of them are interested in going to Germany. I don’t know. […] Maybe we will prepare and communicate with them about the preparation, and [this] will increase the likelihood of going to Germany. We still try. (Interview S)

5.2 Expectations and potentials: The “nurses-to-be”

Who were the Triple Win applicants in Indonesia? All six interviewed “nurses-to-be” were born in the 1990s (mostly between 1997 and 1999). They were in their mid-twenties when they were preparing to go to Germany, and they all came from either Java or Sumatra, Indonesia’s main islands. This finding confirms that relatively few candidates for work opportunities abroad come from more peripheral regions in the country. All of the interviewed nurses already held degrees in nursing: one had a bachelor’s degree plus an education in a private nursing school, five nurses held had a major degree in nursing and/or a diploma in nursing (D4). Four of the interviewees had nursing experience from volunteering for a six-month period during the pandemic, and the remaining two interviewees had at least three years of work experience in the nursing field. Notably, most of them knew about the German programme through on-campus seminars organized by BP3MI or BP2MI. Three candidates mentioned that they had friends who were already involved in the programme, and two said that they had friends going to Japan for work. When asked why they decided to go to Germany, the candidates mentioned Germany’s “good reputation” in the healthcare sector, the desire to go abroad and that the German language would be easier for them to learn than Japanese. Several interviewees mentioned that they had worked in Indonesian hospitals with German medical tools and medicines and that they trusted the German medical system. Additionally, Germany was seen as a country with a very good education system.

When asked about their expectations for Germany, most nurses-to-be said that they were not sure about what to expect upon arrival in Germany. They anticipated that German culture would be very different from that of Indonesia, and culture shock seemed unavoidable to them. In this respect, one of the interviewed experts also mentioned that the way the German embassy posed questions related to the visa process was perceived as inquisitorial and humiliating. Our candidates themselves did not mention this during our interviews.

Interestingly, an important indication of Germany’s welcome culture for some of our interview partners was the fact that a “real mosque with towers” had been built in Cologne (Interview M). This signalled to them that Germany was a Muslim-friendly country. Some of the participants said that they were of Christian religion. Raharto and Noveria (2020: 113) underline the strong role of the family in any migration decision. Our interview partners confirmed this finding: the family’s influence on individual decision-making was high. Our Indonesian interviewees said that their families asked them very practical questions about Germany such as: “What is there in Germany? How is it to live there? What can you eat? How will you pray?” However, some young professionals also said that they would use the opportunity to stay abroad as a means of escaping family ties they perceived as limiting.

Previous contact with cultures outside of Indonesia turned out to be the exception: only two out of the six interviewed candidates had previously travelled outside Indonesia (e.g. for holidays in another Asian country). None of them had any experience with Europe, but one candidate said that she knew someone who went to the Netherlands. They said that they were interested in travelling to the United States (Texas), Australia, Singapore or Japan. It became clear that Germany was not the candidates’ first choice, but that they were interested in the Triple Win because it offered desirable conditions. Four of the six candidates opted to work in a hospital in a big city in Germany, while one said they were flexible, and another said s/he would prefer to work in a small town.

When asked why they had decided to live and work in Germany for the next few years, our respondents named earning a good salary and potentially sending remittances as their primary motivation. They also noted that they would like to acquire more professional skills and that they expected life to be more secure in Germany, especially for women. As expressed by one of our interview partners:

The expectation of living in Germany is that I can certainly have a better quality of life than here. Maybe the convenience of life in Indonesia is much easier. Living in Germany certainly has many challenges. However, for technological advances, education and health in Germany, Germany is much better. Human resources in Germany are also better than in Indonesia. I hope I can be happier living in Germany. In addition, the environment in Germany is safer for women, especially for women who go out alone. This is different from Indonesia, where there is still catcalling for women, so it is less safe. [I-N-2, quoted after Hillmann and Handayani 2024: 71]

Finally, we asked the candidates how long they intended to stay in Germany. Most said that they would initially stay for two to three years and then decide whether to continue working in Germany, go somewhere else or return to Indonesia. All described how the contact to the diaspora and their colleagues already living abroad would facilitate their integration upon arrival in Germany. All participants in the language courses and the Triple Win programme felt that is was well-organized and offered them a fair deal. Additionally, social media served as a prominent source of information while the candidates were deciding whether to go abroad: all of the candidates mentioned YouTube tutorials and/or social media platforms.

6 Conclusion

Our research, focusing on two countries sitting on opposite ends of the negotiating table in a power-laden field of global migration, only allows for a first impression of what the organization of international nurse migration between two inequal partners could look like in the coming years. Our sample was small and temporally restricted to autumn 2023, when implementation of the Triple Win approach had just taken off in Indonesia. Still, it is possible to draw some conclusions. As Näre and Silva (2020) stated in their research on Filipino nurses moving to Finland, we could observe how the design of practices for organizing international recruitment led to new dependencies – be it within the global care chain, but also on the national and the local scale. Concerning the integration of the two countries into the global care chains as part of their migration systems, our research suggests that the Triple Win approach came in handy for Indonesia because it helped to formalize the country’s integration into global care migration chains and allowed for it to connect to the European migration system through Germany. This formalization was supported internally by a) a change in the narrative of migration and an acknowledgement of the importance of the diaspora, b) the top-down internationalization of the national education system in selected regions, and c) the establishment of new social policy elements for migrant workers in Indonesia. The design of the Triple Win structure was based on the blueprint of the Philippine case, but soon developed its own dynamics, e.g. through the establishment of a new centre for skilled migration in Java (Bandung), as well as the subtle exclusion of local players.

In contrast, for Germany, the introduction of Triple Win in Indonesia started when the WHO safeguard list no longer mentioned Indonesia. Germany designed its Triple Win approach in Indonesia with the ambition of providing fair migration standards and meeting its need for skilled personnel in the healthcare sector. Our research showed that in the Philippine case, the number of international nurses entering the Triple Win programme was on the decline since the pandemic. Operators had started to reach out to interested professionals in the peripheral regions of the country. Our research further revealed that in both Triple Win countries, the role of language training was pivotal and that there was a severe shortage of teachers with native language skills of German. Nonetheless, our research also found that Germany, with its broad network of Goethe-Institutes and the German Chambers of commerce (Auslandshandelskammern), was in a nearly ideal position to activate and foster international migration networks and help preventing a dominance of exploitative migration industries.

We identified a spatial pattern accompanying the “making” of the Triple Win process: the recruitment of nurses in Indonesia was tied to the central region of Java and far less directed to the country’s peripheral regions. The location of educational centres providing international classes in Indonesia was decided in a top-down manner. Most of the future nurses, all in their 20s, already held a degree in nursing and had worked for some time in Indonesia. Nearly all planned to send remittances back home while working. But they also hoped to improve their professional skills and to find better working conditions abroad. They were positive about taking part in the Triple Win in Jakarta as it allowed them to pursue their plans for migrating to another country. Until then, Germany had not been in the focus of their attention but was generally held in high regard. Yet, it was difficult for them to tell for how long they intended to stay in Germany once they emigrated. Our findings thus point to the crucial issue of how flexible the more formalized migration system, supported by Triple Win, will be. For the nurses themselves, better options for return migration and circulation could contribute to fair migration and reduce the risk of extractive migration corridors.

References

Aulenbacher, B.; Lutz, H.; Palenga-Möllenbeck E. (2024): Home Care for Sale. London: SAGE Publications 2024.Search in Google Scholar

Azahaf, Najim (2020): Fostering transnational skills partnerships in Germany. Making Fair Migration a Reality. Bertelsmann Foundation, Policy Brief Migration.Search in Google Scholar

Abagat, R. H. (5 July 2021): Sociocultural Integration of Filipino migrant nurses: Findings from the Triple Win Project (TWP) Implementation. 5th International Conference on Public Policy, Barcelona, Spain. https://www.ippapublicpolicy.org/file/paper/6090f93891457.pdfSearch in Google Scholar

Acker, J. (2006): “Inequality Regimes: Gender, Class, and Race in Organizations”, Gender & Society 20(4): 441–464. https://doi.org/10.1177/089124320628949910.1177/0891243206289499Search in Google Scholar

Anderson, B.; Ruhs, M. (2013): “Responding to Employers: Skills, Shortages and Sensible Immigration Policy”, in: G. Brochmann; E. Jurado (eds.): Europe’s Immigration Challenge: Reconciling Work, Welfare and Mobility. London: I. B. Tauris & Co Ltd., 95–104.Search in Google Scholar

Atthareq, R. H.; Affandi, R. N. (2023): “Indonesia-Germany cooperation in efforts to improve vocational education levels: Analysis of the Ausbildung program”, Jurnal Pendidikan Vokasi 13(1): 69–79. https://doi.org/10.21831/jpv.v13i1.4934110.21831/jpv.v13i1.49341Search in Google Scholar

Bakker, I.; Silvey, R. (eds.) (2008): Beyond States and Market: The Challenges of Social Reproduction. Routledge. London.Search in Google Scholar

Bachtiar, P. P. (2011): The governance of Indonesian overseas employment in the context of decentralization. RePEc: Research Papers in Economics. Also: Philippine Institute for Development Studies.http://www.smeru.or.id/sites/default/files/publication/migrantworkers_monograph.pdfSearch in Google Scholar

Chang, A. S. (2021): “Selling a Resume and Buying a Job: Stratification of Gender and Occupation by States and Brokers in International Migration from Indonesia”, Social Problems 68(4): 903–924. https://doi.org/10.1093/socpro/spab00210.1093/socpro/spab002Search in Google Scholar

Chikanda, A. (2022): “Migration Intermediaries and the Migration of Health Professionals from the Global South”, in: M. Walton-Roberts (ed.): Global Migration, Gender, and Health Care Professional Credentials. Transnational Value Transfer and Losses. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 167–186. https://doi.org/10.3138/9781487531744-01110.3138/9781487531744-011Search in Google Scholar

Clemens, M. A.; Dempster, H. (2021): Ethical Recruitment of Health Workers: Using Bilateral Cooperation to Fulfill the World Health Organization’s Global Code of Practice. OECD. https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/PP212-Clemens-Dempster-Ethical-recruitment-health-workers-WHO-Code.pdfSearch in Google Scholar

Efendi, F.; Haryanto, J.; Indarwati, R.; Kuswanto, H.; Ulfiana, E.: Has, E. M. M.; Chong, M. C. (2021): “Going Global: Insights of Indonesian Policymakers on International Migration of Nurses”, Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare 14: 3285–3293. https://doi.org/10.2147/jmdh.s32796210.2147/JMDH.S327962Search in Google Scholar

Farbenblum, B.; Taylor-Nicholson, E.; Paoletti, S. (2013): Migrant Workers’ Access to Justice at Home: Indonesia. Worker’s Acess to Justice Series 495. Open Society Foundations, New York, USA. https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/faculty_scholarship/495Search in Google Scholar

Nyberg Sørensen, N.; Gammeltoft-Hansen, T. (eds.) (2013): The Migration Industry and the Commercialization of International Migration. Routledge. London.10.4324/9780203082737Search in Google Scholar

Gelb, Stephen (2024): Diaspora resource flows as a vehicle for sustainable development. In: Piper, Nicola and Kavita Datta (2024) (ed.): The Elgar Companion to Migration and the sustainable Development Goals. Edward Elger Publishing, pp. 214–22910.4337/9781802204513.00023Search in Google Scholar

Ginting, R. T.; Bisma, G.; Gelgel, N. M. R. A. (2022): “Bunda Corla’s Phenomenon: İnstafamous and Personal Branding”, Communicare: Journal of Communication Studies 9(2): 139–146. https://doi.org/10.37535/10100822021610.37535/101008220216Search in Google Scholar

GIZ (2025): https://www.arbeitsagentur.de/vor-ort/zav/projects-programs/health-and-care/triple-win, accessed 23.10.2025Search in Google Scholar

Hanrieder, T.; Janauschek, L. (2025): “The ‘Ethical Recruitment’ of İnternational Nurses: Germany’s Liberal Health Worker Extractivism”, Review of International Political Economy 32(4): 1164–1188. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2025.245039910.1080/09692290.2025.2450399Search in Google Scholar

Heuke, S. (2023): Das Ringen um die Regulierung der Migration: ein Einblick in die internationalen Abkommen und der Anspruch der fairen Migration Jahrestagung Rat für Migration, Technische Universität (TU) Berlin. https://www.static.tu.berlin/fileadmin/www/40000126/Paradigmenwechsel_weiterdenken/Folienset_Stephan_Heuke_24_11_2023_neu.pdfSearch in Google Scholar

Hillmann, F.; Walton-Roberts, M.; Yeoh, B. S. (2022): “Moving nurses to cities: On how migration industries feed into glocal urban assemblages in the care sector”, Urban Studies 59(11): 2294–2312. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098022108704810.1177/00420980221087048Search in Google Scholar

Hillmann, F.; Handayani, W. (2024): „Nurses by design?“ – Die Vermittlungsabsprache mit Indonesien im Kontext von Triple win – eine Momentaufnahme. TU Berlin, nups Working Paper Nr. 3.Search in Google Scholar

Hochschild, A. R. (2003): The Commercialization of Intimate Life: Notes from Home and Work. University of California Press. Berkeley.10.1525/9780520935167Search in Google Scholar

Näre, L.; Silva, T. C. (2020): “The Global Bases of Inequality Regimes: The Case of International Nurse Recruitment”, Equality Diversity and Inclusion. An International Journal 40(5): 510–524. https://doi.org/10.1108/edi-02-2020-003910.1108/EDI-02-2020-0039Search in Google Scholar

Hugo, G. (2002): “Effects of International Migration on the Family in Indonesia”, Asian and Pacific Migration Journal 11(1): 13–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/01171968020110010210.1177/011719680201100102Search in Google Scholar

IOM (2018): Informing the implementation of the Global Compact for Migration. IOM GMDAC, Berlin, Germany, Data Bulletin Nr. 9.Search in Google Scholar

IOM (2023): IOM Indonesia Programmes. Jakarta, Indonesia.Search in Google Scholar

Kaspar, H. (2022): “Circulation of Love: Care Transactions in the Global Health Care Market of Transnational Medical Travel”, in: M. Walton-Roberts (ed.), Global Migration, Gender, and Health Care Professional Credentials. Transnational Value Transfer and Losses. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 49–68.10.3138/9781487531744-005Search in Google Scholar

Kim, H. (2023): “‘My life would have been happier in Germany’: Korean Guestworker Nurses’ Journeys to Germany and to the US”, Identities: Global Studies in Culture and Power 30(6): 823–840. https://doi.org/10.1080/1070289x.2023.218660310.1080/1070289X.2023.2186603Search in Google Scholar

Kordes, J.; Pütz, R.; Rand, S. (2020): “Analyzing Migration Management: On the Recruitment of Nurses to Germany”, Social Sciences 9(2): 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci902001910.3390/socsci9020019Search in Google Scholar

Kuptsch, C. (ed.) (2010): The Internationalization of Labour Markets. The Social Dimension of Globalization. ILO. https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/wcmsp5/groups/public/@ed_protect/@protrav/@migrant/documents/publication/wcms_208705.pdfSearch in Google Scholar

Lauxen, O.; Larsen, C.; Slotala, L. (2019): “Pflegefachkräfte aus dem Ausland und ihr Beitrag zur Fachkräftesicherung in Deutschland. Das Fallbeispiel Hessen”, Bundesgesundheitsblatt – Gesundheitsforschung – Gesundheitsschutz 62(6): 792–797. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00103-019-02956-410.1007/s00103-019-02956-4Search in Google Scholar

Logan, D.; Loh, L. C.; Huang, V. (2018): “The ‘Triple Win’ Practice: The Importance of Organizational Support for Volunteer Endeavors undertaken by Health Care Professionals and Staff”, Journal of Global Health 8(1). https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.08.010305Search in Google Scholar

Lutz, H.; E. Palenga-Möllenbeck (2012): “Care Workers, Care Drain, and Care Chains: Reflections on Care, Migration, and Citizenship”, Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society 19(1): 15–37. https://doi.org/10.1093/sp/jxr02610.1093/sp/jxr026Search in Google Scholar

Missbach, A.; Palmer, W. (2018): “Indonesia: A Country Grappling with Migrant Protection at Home and Abroad”, Migration Policy Institute, Migration information source, online journal, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/indonesia-country-grappling-migrant-protection-home-and-abroad.Search in Google Scholar

Mosuela, C. C. (2023): Die globale Migration von Pflegekräften zurückgewinnen. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-39166-810.1007/978-3-031-39166-8Search in Google Scholar

Asian Development Bank; together with ILO; OECD. (2024): Labour migration in Asia – Trends, skills certification and seasonal work. https://doi.org/10.1787/9b45c5c4-en10.1787/9b45c5c4-enSearch in Google Scholar

Parreñas, R.; Silvey, R. (2021): “The Governance of the Kafala System and the Punitive Control of Migrant Domestic Workers”, Population, Space and Place 27(5). https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.248710.1002/psp.2487Search in Google Scholar

Pfau-Effinger, B.; Geissler, B. (eds.). (2005): Care and Social Integration in European Societies (1st ed.). Bristol: Bristol University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt9qgr8h10.1332/policypress/9781861346049.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Piper, N. (2008): “Feminisation of Migration and the Social Dimensions of Development: The Asian Case”, Third World Quarterly 29(7): 1287–1303.10.1080/01436590802386427Search in Google Scholar

Plotnikova, E.; Adhikari, R. (2023): “Conclusion: Nurse migration in Asia”, in: Evgeniya Plotnikova; Radha Adhikari (eds.), Nurse Migration in Asia. Routledge, London, 155–165. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003218449-910.4324/9781003218449-9Search in Google Scholar

Pradipta, R. O.; Efendi, F.; Alruwaili, A.; Diansya, M. R.; Kurniati, A. (2023): “The Journey of Indonesian Nurse Migration: A Scoping Review”, Healthcare in Low-resource Settings 11(2). https://doi.org/10.4081/hls.2023.1183410.4081/hls.2023.11834Search in Google Scholar

Raghuram, Parvati (2012): “Global Care, Local Configurations? Challenges to Conceptualizations of Care”, Global Networks 12(2): 155–174. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0374.2012.00345.x.10.1111/j.1471-0374.2012.00345.xSearch in Google Scholar

Raharto, A.; Noveria, M. (2020): “Nurse Migration and Career Development: The Indonesian Case”, in: Y. Tsujita; O. Komazawa (eds.), Human Resources for the Health and Long-term Care of Older Persons in Asia. Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia (ERIA), Jakarta, 63–102. https://www.ide.go.jp/library/English/Publish/Reports/Ec/pdf/202011_ch03.pdfSearch in Google Scholar

Raharto, A.; Noveria, M. (2023): “Indonesian International Nurse Migration: Assessing Migration as Investment for Future Work”, in: Y. Tsujita; O. Komazawa (eds.), Human Resource Development, Employment, and International Migration of Nurses and Caregivers in Asia and the Pacific Region, ERIA Research Project Report FY2023 No. 07. ERIA, Jakarta, 107–130. https://www.ide.go.jp/library/English/Publish/Reports/Ec/pdf/202307_ch06.pdfSearch in Google Scholar

Scheele, A.; Schiffbänker, H.; Walker, D.; Wienkamp, G. (2023): “Double Fragility: The Care Crisis in Times of Pandemic”, Gender and Research 24(1): 11–35. https://doi.org/10.13060/gav.2023.00310.13060/gav.2023.003Search in Google Scholar

Schneider, Jan (2023): Labor migration schemes, pilot partnerships, and skills mobility initiatives in Germany. Background paper to the World Development Report 2023: Migrants, Refugees, and Societies. Washington DC. https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/1b03278725f9fff007a3b91dc9301135-0050062023/original/230331-Schneider-Background-Paper-FINAL.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Schwiter, K.; Steiner, J. (2020): “Geographies of Care Work: The Commodification of Care, Digital Care Futures and Alternative Caring Visions”, Geography Compass 14. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12546. Article e12546.10.1111/gec3.12546Search in Google Scholar

Shaffer, F. A.; Bakhshi, M.; Cook, K. N.; Álvarez, T. D. (2022): “International Nurse Recruitment Beyond the COVID-19 Pandemic”, Nurse Leader 20(2): 161–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mnl.2021.12.00110.1016/j.mnl.2021.12.001Search in Google Scholar

Shire, K. (2020): “The Social Order of Transnational Migration Markets”, Global Networks 20(3): 434–453. https://doi.org/10.1111/glob.1228510.1111/glob.12285Search in Google Scholar

Skeldon, R. (2008): “International Migration as a Tool in Development Policy: A Passing Phase?”, Population and Development Review 34(1): 1–18. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2543465610.1111/j.1728-4457.2008.00203.xSearch in Google Scholar

Tern Group (2025): Global Nurse Migration Is Changing: What the Next Wave Means for International Healthcare Recruitment. https://www.tern-group.com/de/blog/the-future-of-global-nurse-migration-why-the-next-wave-wont-follow-the-old-paths, visited 30.09.2025.Search in Google Scholar

Theobald, H. (2022): “Brennglas Corona und die Reformen in der Altenpflege in Deutschland. Nationale und internationale Perspektiven”, in: J. Lange; A. Yollu-Tok (guest eds.): Sozialer Fortschritt 71, Sonderheft 10: Die großen Herausforderungen der Sozialpolitik in der neuen Legislaturperiode: Lehren aus der Coronakrise, 749–769.10.3790/sfo.71.10.749Search in Google Scholar

Triandafyllidou, A.; Yeoh, B. S. A. (2023): “Sustainability and Resilience in Migration Governance for a Post-pandemic World”, Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies 21(1): 1–14, DOI: 10.1080/15562948.2022.212264910.1080/15562948.2022.2122649Search in Google Scholar

Vaittinen, Tiina (2014): “Reading Global Care Chains as Migrant Trajectories: A Theoretical Framework for the Understanding of Structural Change”, Women’s Studies International Forum 47: 191–202.10.1016/j.wsif.2014.01.009Search in Google Scholar

Walton-Roberts, M. (ed.) (2022): Global Migration, Gender, and Health Care Professional Credentials. Transnational Value Transfer and Losses. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.10.3138/9781487531744Search in Google Scholar

Yeates, N.; Pillinger, J. (2021): “International Organizations, Care And Migration: The Case of Migrant Health Care Workers”, International Organizations in Global Social Governance. Ed, by K. Martens, Dennis Niemann and Alexandra Kaasch, Palgrave, macmillan, 83–111. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-65439-9_410.1007/978-3-030-65439-9_4Search in Google Scholar

Appendix

Bilateral labour recruitment projects, 2012–2023.

|

Project |

Sector |

Country of Origin |

Year |

Type |

|

Triple Win |

Nursing/Geriatric Care |

Bosnia and Herzegovina Philippines Tunisia India Indonesia (new) Mexico (new) Brazil (new) |

2012–present |

Recruitment of qualified professionals |

|

Triple Win Vietnam |

Nursing/Geriatric Care |

Vietnam |

2012–2018, 2016–2019, ongoing |

Training of professionals in Germany |

|

Hand in Hand for International Talent |

Electric, IT, gastronomy, hospitality |

Brazil India Vietnam |

2020–present |

Helping German companies in recruiting professionals |

|

HabiZu |

Electronics, metal construction, mechanics |

Bosnia and Herzegovina |

2020–2023 |

Recruiting professionals |

|

THAMM |

Gastronomy, hospitality, commercial, electronics, sanitation, heating, plumbing |

Egypt Morocco Tunisia |

2019–present |

Recruiting trainees and professionals |

|

APAL |

Health |

El Salvador Mexico (as of 2021) |

2019–present |

Recruiting trainees |

|

Global Skills Partnership |

Care |

Mexico Philippines |

2021–present |

Training to German standards in home country |

|

YES Kosovo |

Construction Sector |

Kosovo |

2017–2021 |

Training to German standards in home country |

|

PAM |

Mechanics/engineering, construction, early education |

Ecuador Nigeria Kosovo Vietnam |

2019–present |

Various |

Source: compilation by the authors (internet research and Angenendt et al., 2023.)

© 2025 the author(s), published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.