Abstract

Explorative high-pressure/high-temperature syntheses (9 GPa, 1,200 °C) starting from NiO and H3BO3 yielded a product mixture containing single crystals of NiB6O8(OH)4, a new orthorhombic borate (space group Fdd2) with the lattice parameters a = 39.097(4) Å, b = 4.3880(4) Å, c = 7.5899(8) Å, V = 1,302.1(2) Å3, and eight formula units per cell. This compound is the third one in the structural class of borates with the general formula M(B6O9–x )(OH)3+x (M = In3+, Sc3+ (x = 0), Ni2+ (x = 1)). The reaction product has been studied by means of powder X-ray diffraction, and an infrared spectrum of a single crystal has been recorded. Results of BLBS and CHARDI calculations are presented.

1 Introduction

During high-pressure/high-temperature (HP/HT) investigations on the transition and main group metal borates, several new structure types of borates have been established: e. g., β-MB4O7 (M = Mg, Mn–Zn), 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 M 2BO4 (M = Fe, Co, Ni), 5 , 6 , 7 and M 5B12O25(OH) (M = Al, Ga, In, V, Cr). 8 , 9 , 10 Under extreme conditions of pressure and temperature, typical structure types not only tend to host atoms with a wider range of ionic radii, 11 , 12 but can also adapt to host cations with different valence states by incorporation of hydrogen atoms and by a potential occupation of previously unoccupied sites, e. g., Mn2+ 5Mn2+B12O22(OH)4, 9 a compound, which is based on the original M 5B12O25(OH) structure type.

At present, 10 compounds exist in the system Ni(II)–B–O(–H). Four of them crystallize under ambient pressure conditions, namely Ni[B6O7(OH)6]·5H2O, 13 Ni(H2O)4[B6O7(OH)6]·H2O, 14 NiB12O14(OH)10, 15 and Ni3(BO3)2. 16 The other six borates were synthesized under high pressure/high-temperature conditions: β-/γ-NiB4O7, 3 , 17 Ni(B2O4), 7 Ni[B2O2(OH)4], 18 NiB3O5(OH), 19 Ni6(B22O39)(H2O), 20 and Ni3B18O28(OH)4·(H2O). 21

In the current work, we report on the HP/HT synthesis and crystal structure of a new orthorhombic nickel borate with the composition NiB6O8(OH)4, the first example containing a metal dication with in the series possessing the general formula M(B6O9−x )(OH)3+x (M = In3+, Sc3+ (x = 0), 22 , 23 Ni2+ (x = 1)).

2 Experimental section

2.1 Synthesis

The starting materials NiO (99.9 %, Strem Chemicals, Bischheim, France) and H3BO3 (99.8 %, Carl Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany) in the form of powders were mixed in the molar ratio of 1:6 and transferred into a Pt capsule. The experiment was carried out via high-pressure/high-temperature methods using a Walker-type multianvil module within a 1,000 t hydraulic press (Max Voggenreiter GmbH, Mainleus, Germany) in an 18/11 assembly. Further details concerning this kind of setup have been described previously in the literature. 12 , 24 , 25

The pressure of 9 GPa was built up within 240 min, followed by heating up to 1,200 °C within 15 min. The maximum temperature of the reaction mixture was held for 20 min, then reduced to 400 °C with a cooling rate of 2.5 K min−1. Afterwards, the product was quenched to room temperature within a few minutes. Decompression to ambient conditions was performed within 920 min.

2.2 Phase identification and structure determination by single-crystal X-ray diffraction

The reaction product was analysed with an STOE Stadi P powder X-ray diffractometer (STOE & Cie GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany) equipped with a Mythen 1 K microstrip detector (Dectris, Baden-Daettwil, Switzerland). Measurements were performed in transmission geometry with Ge(111)-monochromatized MoK-L3 radiation (λ = 0.7093 Å) within a range of 2θ = 2–50° and a step size of 0.015°.

A suitable single crystal was isolated under a Leica 125M polarization microscope and measured using a Bruker D8 Quest diffractometer equipped with a CMOS Photon 300 detector. A multiscan absorption correction was performed with Sadabs-2014/5. 26 Structure solution and refinement were performed within the program Olex2 1.5 and ShelXL-2018/3 algorithms. 27 , 28 , 29 , 30

2.3 Infrared spectroscopy

A single crystal of NiB6O8(OH)4 was mounted on a BaF2 plate and the spectrum was collected with a Bruker Vertex 70 FT-IR spectrometer. The spectrometer was equipped with a KBr beam splitter, a liquid nitrogen-cooled Mercury Cadmium Telluride (MCT) detector, and a Bruker Hyperion 3,000 microscope. A Globar (silicon carbide) rod was used as mid-IR source and the radiation was focused on the sample with a 15 × IR objective. For data collection and correction for atmospheric influences, the Opus 7.2 software 31 was employed.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Powder X-ray diffraction

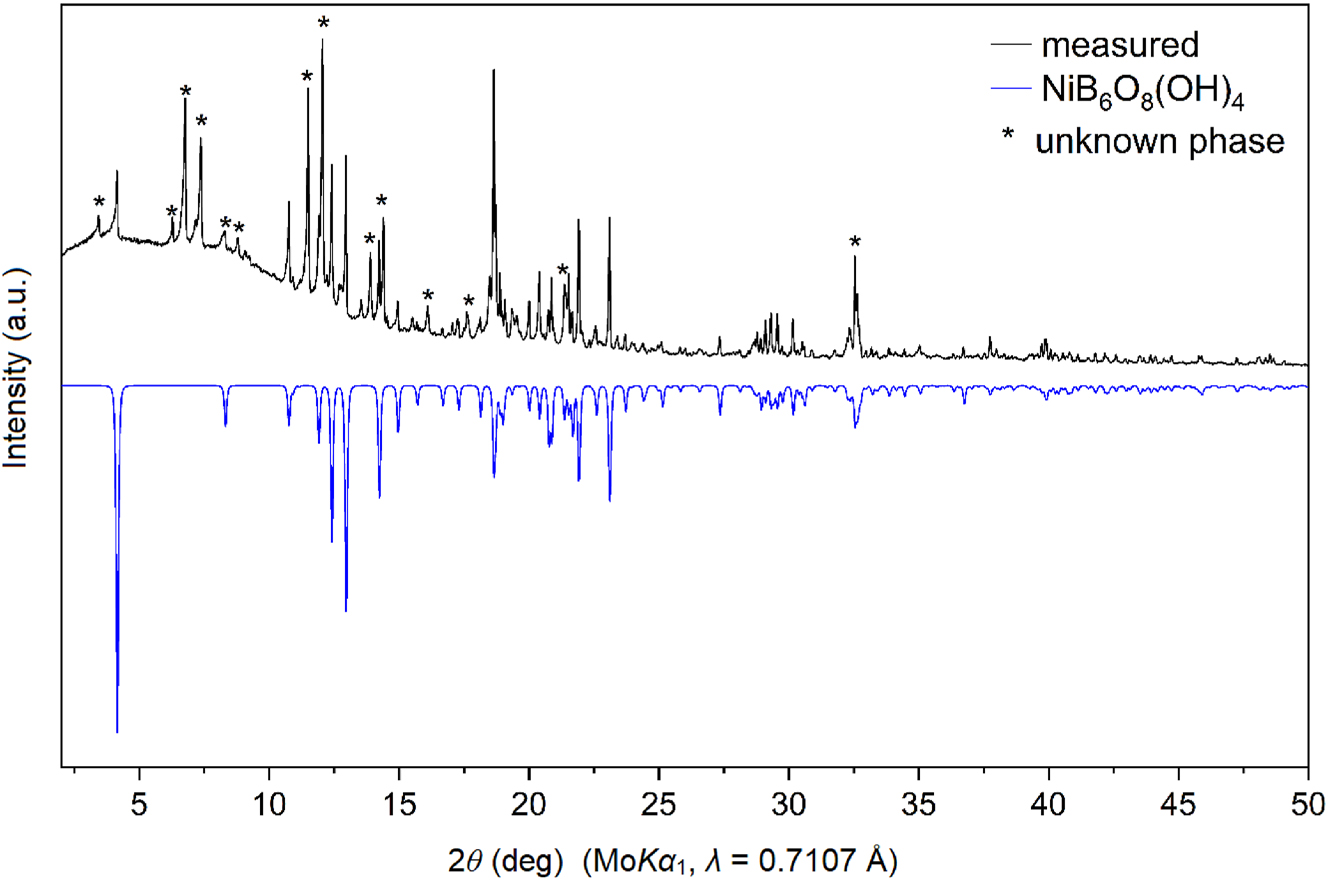

The product consisted of a light green/colorless microcrystalline matrix, in which one could observe larger light-green crystals of NiB6O8(OH)4. The powder pattern is shown in Figure 1 (top). The side phase remains unknown due to a lack of measurable crystals.

Powder X-ray diffraction pattern of the sample as obtained from the synthesis (top) and theoretical pattern of the new borate modelled on the basis of the single-crystal data (bottom). Reflections of the unknown side product are marked with asterisks.

3.2 Crystal structure description

NiB6O8(OH)4 crystallizes in the orthorhombic space group Fdd2 (no. 43) with the unit cell parameters a = 39.097(4) Å, b = 4.3880(4) Å, c = 7.5899(8) Å, V = 1,302.1(2) Å3, and eight formula units per cell. The structure and refinement data are shown in Table 1. Further details on the structure refinement such as atomic coordinates, anisotropic displacement parameters, selected interatomic distances, and bond angles are provided in Tables 2–5.

Single-crystal data and structure refinement of NiB6O8(OH)4.

| Empirical formula | NiB6O8(OH)4 |

| Molar mass, g mol−1 | 1,302.1 |

| Crystal system | Orthorhombic |

| Space group | Fdd2 (no. 43) |

| Single-crystal diffractometer | Bruker D8 Quest Kappa |

| Radiation/wavelength λ, Å | MoK-L2,3/0.7107 |

| a, Å | 39.097(4) |

| b, Å | 4.3880(4) |

| c, Å | 7.5899(8) |

| V, Å3 | 1,302.1(2) |

| Formula units per cell Z | 8 |

| Calculated density, g cm−3 | 3.22 |

| Crystal size, mm | 0.08 × 0.04 × 0.03 |

| Temperature, K | 293 |

| Absorption coefficient, mm−1 | 3.1 |

| F(000), e | 1,232 |

| Flack parameter | 0.02(2) |

| θ range, deg | 4.17–39.42 |

| Range in hkl | −70 ≤ h ≤ 70; −7 ≤ k ≤ 5; −13 ≤ l ≤ 13 |

| Refl. total/indep./R int | 17,722/2024/0.056 |

| Refl. with I > 2 σ(I) | 1,913 |

| Data/restraints/ref. parameters | 2024/2/96 |

| Absorption correction | Multi-scan |

| Final R1/wR2 (I > 2 σ(I)) | 0.0266/0.0639 |

| Final R1/wR2 (all data) | 0.0284/0.0648 |

| Goodness-of-fit on F 2 | 1.091 |

| Largest diff. peak/hole, e Å−3 | 0.97/−0.37 |

Atomic coordinates, equivalent isotropic displacement parameters U eq (Å2) and site occupancy factors (S.O.F) for all crystallographically independent atoms in the structure of NiB6O8(OH)4. U eq is defined as one third of the trace of the orthogonalized U ij tensor (standard deviations in parentheses).

| Atom | Wyckoff position | x | y | z | U eq | S.O.F. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ni1 | 8a | ½ | 0 | 0.75063(6) | 0.00551(9) | 1 |

| O1 | 16b | 0.46623(4) | 1.1295(3) | 0.2496(2) | 0.0066(2) | 1 |

| O2 | 16b | 0.46847(4) | 0.1883(4) | 0.5620(2) | 0.0059(3) | 1 |

| O3 | 16b | 0.46602(4) | 0.6862(4) | 0.4340(2) | 0.0068(3) | 1 |

| O4 | 16b | 0.41549(9) | 0.0088(4) | 0.4307(3) | 0.0118(5) | 1 |

| H4 | 16b | 0.401(3) | 0.59(2) | 0.55(2) | 0.27(9) | 1 |

| O5A | 16b | 0.3876(2) | 0.4059(13) | 0.2933(9) | 0.0082(10) | 0.5 |

| O5B | 16b | 0.3876(2) | 0.4857(14) | 0.3200(10) | 0.0090(10) | 0.5 |

| O6 | 16b | 0.41568(8) | 0.4756(4) | 0.5866(3) | 0.0101(5) | 1 |

| H6 | 16b | 0.3998(19) | 0.00(2) | 0.363(12) | 0.14(5) | 1 |

| B1 | 16b | 0.45663(14) | 0.4972(4) | 0.5823(4) | 0.0054(6) | 1 |

| B2 | 16b | 0.39308(7) | 0.2822(6) | 0.4694(3) | 0.0116(4) | 1 |

| B3 | 16b | 0.45726(15) | 1.0025(5) | 0.4175(4) | 0.0071(6) | 1 |

Anisotropic displacement parameters (Å2) for all crystallographically independent atoms in the structure of NiB6O8(OH)4.

| Atom | U 11 | U 22 | U 33 | U 12 | U 13 | U 23 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ni1 | 0.00577(11) | 0.00573(11) | 0.00488(11) | 0 | 0 | 0.00024(10) |

| O1 | 0.0102(5) | 0.0060(4) | 0.0034(4) | −0.0004(5) | 0.0003(4) | −0.0018(4) |

| O2 | 0.0072(5) | 0.0054(5) | 0.0050(5) | −0.0001(4) | −0.0007(4) | 0.0008(4) |

| O3 | 0.0095(5) | 0.0049(5) | 0.0052(5) | 0.0005(4) | 0.0016(4) | 0.0003(4) |

| O4 | 0.0164(10) | 0.0093(8) | 0.0086(7) | −0.0015(5) | 0.0036(6) | −0.0039(5) |

| O5A | 0.0067(12) | 0.012(2) | 0.0083(18) | 0.0034(13) | −0.0016(11) | −0.0019(16) |

| O5B | 0.0059(12) | 0.012(2) | 0.0070(17) | 0.0040(14) | 0.0001(11) | 0.0008(15) |

| O6 | 0.0134(9) | 0.0072(7) | 0.0096(7) | −0.0017(5) | 0.0039(6) | −0.0003(5) |

| B1 | 0.0084(12) | 0.0047(10) | 0.0043(9) | −0.0001(5) | 0.0000(7) | 0.0007(5) |

| B2 | 0.0058(7) | 0.0184(10) | 0.0100(9) | 0.0060(7) | 0.0002(5) | 0.0000(6) |

| B3 | 0.0101(12) | 0.0063(11) | 0.0044(9) | −0.0001(6) | −0.0004(7) | −0.0007(6) |

Selected interatomic distances and average (bold) values (Å) of the coordination polyhedra in the structure of NiB6O8(OH)4 (standard deviation in parentheses).

| Atoms | Distance | Atoms | Distance | Atoms | Distance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1–O2 | 1.441(3) | B2–O5A | 1.435(8) | B2–O5B | 1.436(9) |

| B1–O3 | 1.446(4) | B2–O5A | 1.458(8) | B2–O5B | 1.459(8) |

| B1–O1 | 1.446(4) | B2–O4 | 1.514(4) | B2–O4 | 1.514(4) |

| B1–O6 | 1.604(7) | B2–O6 | 1.514(4) | B2–O6 | 1.514(4) |

| Average | 1.483(4) | Average | 1.480(6) | Average | 1.481(6) |

| B3–O2 | 1.434(4) | Ni1–O2 (2 × ) | 2.062(2) | O4–H4 | 0.80(9) |

| B3–O3 | 1.435(3) | Ni1–O3 (2 × ) | 2.091(2) | O6–H6 | 0.81(1) |

| B3–O1 | 1.435(4) | Ni1–O1 (2 × ) | 2.094(2) | ||

| B3–O4 | 1.636(6) | ||||

| Average | 1.485(4) | Average | 2.082(2) |

Selected interatomic angles and their averaged (bold) values (deg) of the coordination polyhedra in the structure of NiB6O8(OH)4 (standard deviation in parentheses).

| Atoms | Angle | Atoms | Angle |

|---|---|---|---|

| O1–B1–O2 | 112.9(3) | O4–B2–O5A | 104.7(7) |

| O1–B1–O3 | 112.8(3) | O4–B2–O5A | 101.7(6) |

| O1–B1–O6 | 105.4(4) | O4–B2–O6 | 102.7(3) |

| O2–B1–O3 | 112.0(3) | O5A–B2–O5 | 112.3(8) |

| O2–B1–O6 | 105.5(3) | O5A–B2–O6 | 118.3(7) |

| O3–B1–O6 | 107.7(3) | O5A–B2–O6 | 114.6(6) |

| Average | 109.4(3) | Average | 109.0(6) |

| O4–B2–O5B | 118.3(7) | O1–B3–O2 | 112.6(3) |

| O4–B2–O5B | 114.8(6) | O1–B3–O3 | 113.3(3) |

| O4–B2–O6 | 102.9(3) | O1–B3–O4 | 107.0(4) |

| O5B–B2–O5B | 112.2(9) | O2–B3–O3 | 114.2(3) |

| O5B–B2–O6 | 104.8(7) | O2–B3–O4 | 104.4(4) |

| O5B–B2–O6 | 101.5(6) | O3–B3–O4 | 104.4(4) |

| Average | 109.0(6) | Average | 109.3(3) |

| O1–Ni1–O2 (2 × ) | 93.63(11) | O1–Ni1–O1 | 179.57(12) |

| O1–Ni1–O2 (2 × ) | 86.08(11) | O2–Ni1–O3 | 177.23(14) |

| O1–Ni1–O3 (2 × ) | 84.56(10) | O2–Ni1–O3 | 177.23(14) |

| O1–Ni1–O3 (2 × ) | 95.75(10) | Average | 178.01(13) |

| O2–Ni1–O3 (2 × ) | 85.74(11) | ||

| O2–Ni1–O2 | 92.06(12) | ||

| O3–Ni1–O3 | 96.51(12) | ||

| Average | 90.00(11) |

Further details of the crystal structure investigation may be obtained from Fachinformationszentrum Karlsruhe, 76, 344 Eggenstein-Leopoldshafen, Germany (fax: +49 7247 808 666; e-mail: crysdata@fiz-karlsruhe.de, https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures/) on quoting the deposition number CSD-2475184.

NiB6O8(OH)4 is isostructural to ScB6O9(OH)3 23 and InB6O9(OH)3 22 (Table 6). Since Ni2+ is smaller than Sc3+ and In3+ 32 (see Table 6), the lattice parameters b and c – which are directly affected by the size of the MO6 layers – are also the smallest in the group for the Ni-containing structure.

Unit cell parameters of known members of the structure class M(B6O9−x )(OH)3+x (M = In3+, Sc3+ (x = 0), Ni2+ (x = 1)) and ionic radii (i.r.) of the corresponding metal cations (C.N. = 6).

| M | Ni2+ this work | Sc3+ 23 | In3+ 22 |

|---|---|---|---|

| i.r., Å 32 | 0.630 | 0.745 | 0.800 |

| a, Å | 39.097(4) | 38.935(4) | 39.011(8) |

| b Å | 4.3880(4) | 4.4136(4) | 4.4820(9) |

| c, Å | 7.5899(8) | 7.6342(6) | 7.740(2) |

| V, Å3 | 1,302.1(2) | 1,311.9(2) | 1,353.3(5) |

| Synthesis conditions | 9 GPa, 1,200 °C | 6 GPa, 1,200 °C | 12 GPa, 1,500 °C |

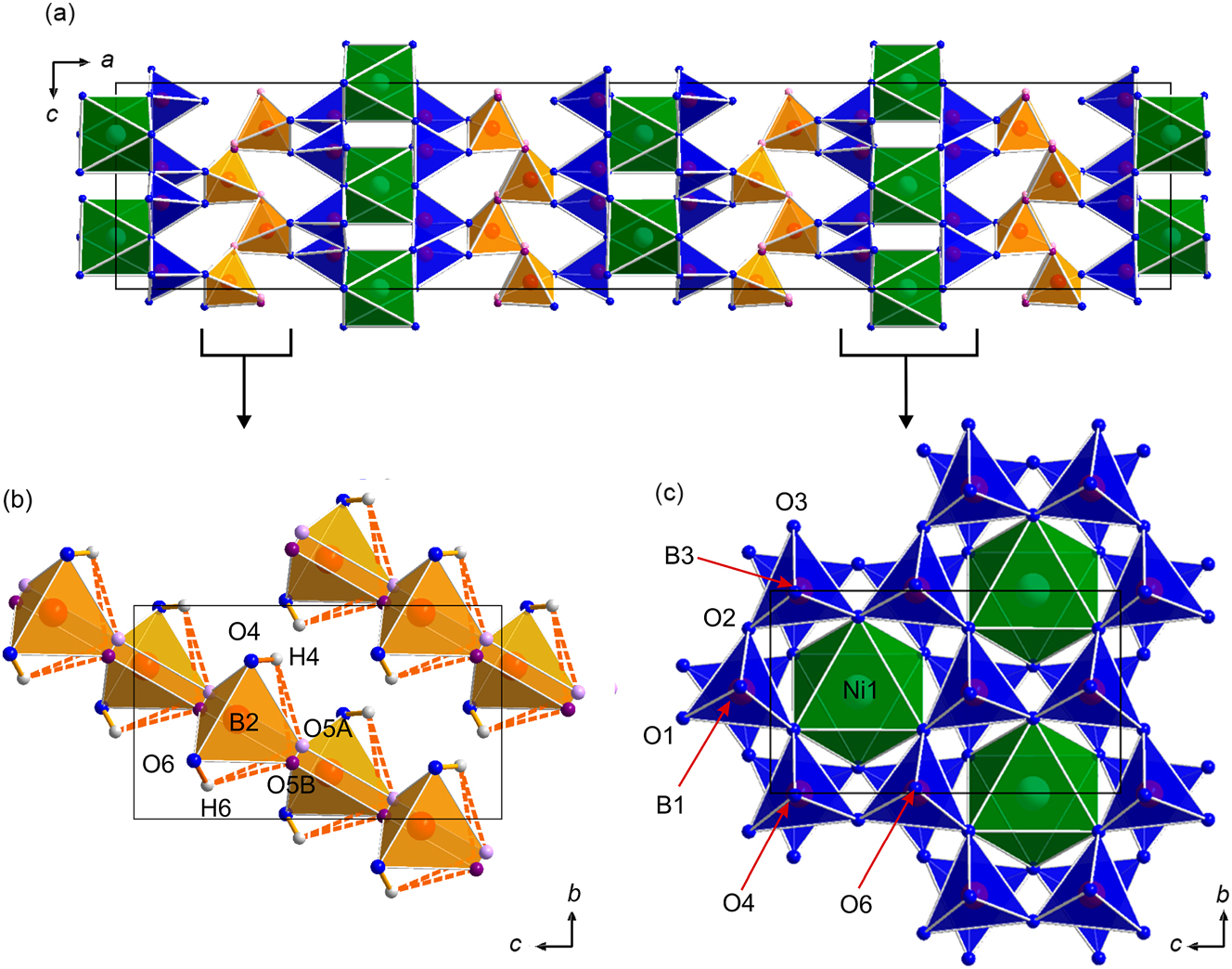

The crystal structure of NiB6O8(OH)4 (Figure 2a) is built up of triple layers of corner-sharing BO4 tetrahedra, separated by NiO6 layers. Along the c axis, one can observe four blocks of these layers, each of these being offset by ¼ ¼ ¼ in relation to the previous one. The middle B2O4 layer consists of two infinite corner-sharing chains (Figure 2b). Two other BO4 layers are framing NiO6 octahedra with tetrahedra oriented away from the layer of octahedra. Each of the BO4 layers consists of alternating B1O4 and B3O4 tetrahedra, all oriented in the same direction within a layer forming sechser-rings (Figure 2c), a consequence of the non-centrosymmetric structure.

(a) Crystal structure of NiB6O8(OH)4 with a view along the b axis; (b) infinite chains of B2O4 tetrahedra (orange) in the middle layer, (c) first and third infinite ring layers consisting of alternating B1O4 and B3O4 tetrahedra (blue), which are surrounding the NiO6 octahedra (green). Non-disordered oxygen atomic sites are shown in blue. Due to the disorder on the sites O5A (shown in light pink) and O5B (shown in purple), the orange B2O4 tetrahedra have two atoms in two of the corners. Hyrdogen atoms are shown in grey and the hydrogen bonds are shown in orange.

The isostructural Sc compound 23 has a disorder within the middle layer in both boron and oxygen atomic sites, while the isostructural In phase does not show any disorder. 22 In comparison to them, the here presented Ni compound also exhibits a disordered oxygen site (O5A and O5B, respectively) within the middle layer, but no signs of a disorder of the boron atomic sites were observed.

As is also observed for the Sc and In compounds, the hydrogen atoms in NiB6O8(OH)4 are located on the middle layer. In order to keep up the charge balance, for the Ni2+ cations, not one, but two protons are required. However, due to the disorder in the structure, their exact location on the basis of X-ray data was not possible. Therefore, BLBS and CHARDI calculations were performed (vide infra).

Average bond lengths in the BO4 tetrahedra range from 1.480–1.485 Å (see Table 4), however, some bonds are elongated: B3–O4 (1.636(6) Å), B2–O4 (1.514(4) Å), and B2–O6 (1.514(4) Å). These bonds are all in the range of known values (1.373–1.699 Å), 33 but their elongation can be seen as another evidence of disorder. A similar effect occurs for the O–B–O angles (see Table 5) in the BO4 tetrahedra: average values are about 109.0(6)°, but several single values (for example, O5A–B2–O6 and O4–B2–O5B (118.3(7)°)) are on the top border (119.43°), 33 while some other single values such as O4–B2–O6 (102.7(3)°) are close to the lower border (95.72°). 33

Bond valence sums (Table 7) were calculated according to the bond-length/bond-strength (BLBS) 34 and charge distribution (CHARDI) 35 concepts.

Calculation of bond valences with BLBS (∑V) and CHARDI-2015 (∑Q) in the structure of NiB6O8(OH)4 without (a) and with (b) hydrogen atoms in comparison with expected values (exp.). For the values formatted in bold see text below.

| Atom | Exp. | a | b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ∑V | ∑Q | ∑V | ∑Q | ||

| Ni1 | +2 | 2.00 | 1.90 | 1.98 | 1.90 |

| B1 | +3 | 3.00 | 3.31 | 2.99 | 2.91 |

| B2 | +3 | 2.99 | 4.43 | 2.99 | 2.94 |

| B3 | +3 | 3.00 | 3.31 | 3.01 | 2.92 |

| O1 | −2 | −1.98 | −1.86 | −1.98 | −2.09 |

| O2 | −2 | −2.02 | −1.86 | −2.02 | −2.13 |

| O3 | −2 | −1.98 | −1.86 | −1.98 | −2.09 |

| O4 | −2 | −1.18 | −1.52 | −2.14 | −1.70 |

| O5A | −2 | −1.62 | −1.36 | −1.70 | −2.18 |

| O5B | −2 | −1.62 | −1.36 | −1.70 | −2.18 |

| O6 | −2 | −1.21 | −1.54 | −2.16 | −1.80 |

| H4 | +1 | – | – | 0.97 | 1.11 |

| H6 | +1 | – | – | 0.95 | 1.17 |

It can be seen from both BLBS and CHARDI calculations that while the oxidation states of the cations Ni2+ and the O2− anions O1–O3 are in a good agreement with the expected values, this is not the case for O4, O6, and O5A/B (bold-formatted values). Based on that observation, and considering elongated B–O bond lengths and the aspect of charge neutrality, it becomes evident that four hydrogen atoms per formula unit are needed. Those should be covalently bound to O4 and O6, establishing weak hydrogen bonds between the oxygen atoms O4 and O5A/B (O4–H4⋯O5A/B).

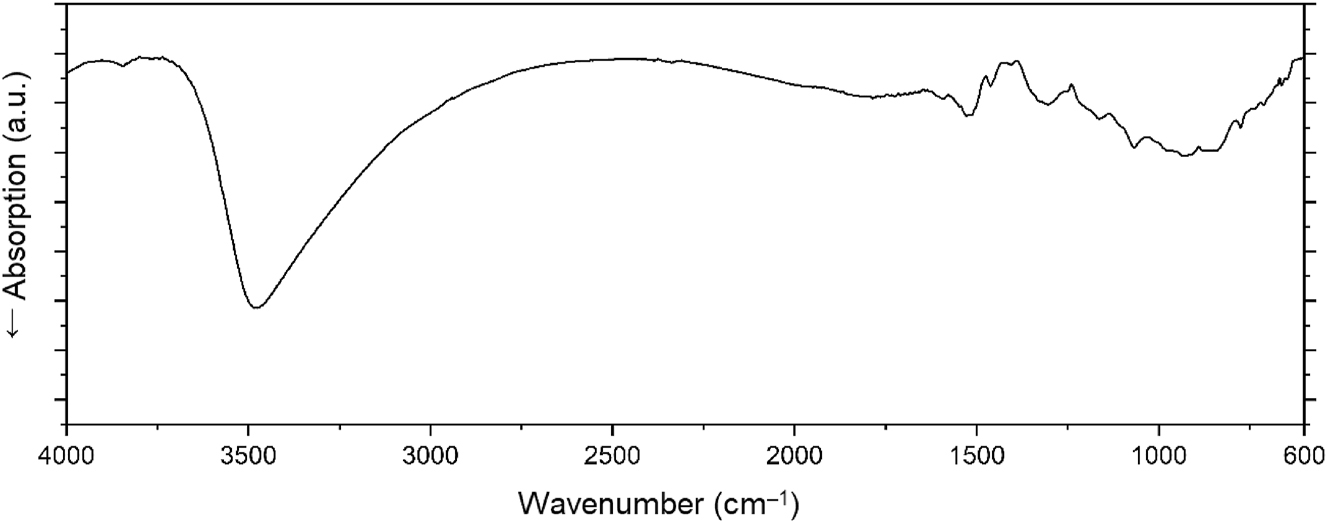

3.3 Single-grain IR spectroscopy

The infrared spectrum of NiB6O8(OH)4 is shown in Figure 3. A strong signal in the range of ∼2,900–3,600 cm−1 can be attributed to OH− stretching modes, and therefore, supports the proposed presence of hydroxyl groups in the structure. 36 Signals around 1,250–1,500 cm−1 can be attributed to O–B–O stretching vibrations. 37 The complicated continuous character of absorptions in the range between 700 and 1,000 cm−1 can be explained as the sum of vibration modes of BO4 and NiO6 units, overlapping with bending vibrations of the BO4 tetrahedra. 38 , 39

The single-crystal infrared spectrum of NiB6O8(OH)4.

4 Conclusions

A new high-pressure/high-temperature borate with the composition NiB6O8(OH)4 has been synthesized and the details of its crystal structure are described. The structure is built up of triple layers of corner-sharing BO4 tetrahedra, separated by NiO6 layers. Two outer borate layers consist of alternating B1O4 and B3O4 tetrahedra. The middle layer in the BO4 triplets consists of two infinite corner-sharing chains. This borate joins the structural class M(B6O9−x )(OH)3+x (M = In3+, Sc3+ (x = 0), 22 , 23 Ni2+ (x = 1)) with Ni as the first dication.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Univ.-Prof. Dr. Roland Stalder and Alexander Fischereder for providing access and operating of the single-crystal infrared spectrometer and Dr. Tobias Teichtmeister for the help with the calculation of bond valences.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: ChatGPT was used to improve language when required.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: The raw data can be obtained on request from the corresponding author. CSD-2475184 contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. The data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

References

1. Neumair, S. C.; Knyrim, J. S.; Glaum, R.; Huppertz, H. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2009, 635, 2002–2008; https://doi.org/10.1002/zaac.200900190.Search in Google Scholar

2. Huppertz, H.; Heymann, G. Solid State Sci. 2003, 5, 281–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1293-2558(02)00057-2.Search in Google Scholar

3. Knyrim, J. S.; Friedrichs, J.; Neumair, S.; Roeßner, F.; Floredo, Y.; Jakob, S.; Johrendt, D.; Glaum, R.; Huppertz, H. Solid State Sci. 2008, 10, 168–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solidstatesciences.2007.09.004.Search in Google Scholar

4. Pasqualini, L. C.; Huppertz, H. Z. Naturforsch. 2023, 78b, 285–291.10.1515/znb-2023-0008Search in Google Scholar

5. Neumair, S. C.; Glaum, R.; Huppertz, H. Z. Naturforsch. 2009, 64b, 883–890.10.1515/znb-2009-0802Search in Google Scholar

6. Neumair, S. C.; Kaindl, R.; Huppertz, H. Z. Naturforsch. 2010, 65b, 1311–1317.10.1515/znb-2010-1104Search in Google Scholar

7. Knyrim, J. S.; Roessner, F.; Jakob, S.; Johrendt, D.; Kinski, I.; Glaum, R.; Huppertz, H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 9097–9100; https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.200703399.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Vitzthum, D.; Wurst, K.; Pann, J. M.; Brüggeller, P.; Seibald, M.; Huppertz, H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 11451–11455; https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201804083.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

9. Pasqualini, L. C.; Tribus, M.; Huppertz, H. Z. Naturforsch. 2024, 79b, 39–49.10.1515/znb-2023-0082Search in Google Scholar

10. Vitzthum, D.; Widmann, I.; Wimmer, D. S.; Wurst, K.; Joachim‐Mrosko, B.; Huppertz, H. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 1165–1174; https://doi.org/10.1002/ejic.202001136.Search in Google Scholar

11. Prewitt, C. T.; Downs, R. T. High-Pressure Crystal Chemistry. In Ultrahigh Pressure Mineralogy. Physics and Chemistry of the Earth’s Deep Interior, Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry Series; Hemley, R. J., Ed.; Walter de Gruyter: Boston, Vol. 37, 1998; pp. 283–318. chapter 9.10.1515/9781501509179-011Search in Google Scholar

12. Huppertz, H. Z. Kristallogr. 2004, 219, 330–338; https://doi.org/10.1524/zkri.219.6.330.34633.Search in Google Scholar

13. Silin, E. Y. I. A. Kristallografiya 1977, 22, 505–509.10.1016/0301-0104(77)89036-8Search in Google Scholar

14. Silin, E. Y.; Zavodnik, V. E.; Ozolins, G.; Tetere, I. V. Latv. PSR Zinat. Akad. Vestis, Kim. Ser. 1988, 15, 404–410.Search in Google Scholar

15. Ju, J.; Sasaki, J.; Yang, T.; Kasamatsu, S.; Negishi, E.; Li, G.; Lin, J.; Nojiri, H.; Rachi, T.; Tanigaki, K.; Toyota, N. Dalton Trans. 2006, 1597–1601; https://doi.org/10.1039/b517155e.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Pardo, J.; Martinez-Ripoll, M.; García-Blanco, S. Acta Crystallogr. 1974, B30, 37–40.10.1107/S0567740874002160Search in Google Scholar

17. Schmitt, M. K.; Janka, O.; Niehaus, O.; Dresselhaus, T.; Pöttgen, R.; Pielnhofer, F.; Weihrich, R.; Krzhizhanovskaya, M.; Filatov, S.; Bubnova, R.; Bayarjargal, L.; Winkler, B.; Glaum, R.; Huppertz, H. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 56, 4217–4228; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.7b00243.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Pasqualini, L. C.; Huppertz, H. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2024, 650, e202400137 (6 pages).10.1002/zaac.202400137Search in Google Scholar

19. Schmitt, M. K.; Janka, O.; Pöttgen, R.; Huppertz, H. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2017, 643, 1344–1350.10.1002/zaac.201700130Search in Google Scholar

20. Schmitt, M. K.; Huppertz, H. Z. Naturforsch. 2017, 72b, 967–975.10.1515/znb-2017-0148Search in Google Scholar

21. Schmitt, M. K.; Janka, O.; Pöttgen, R.; Wurst, K.; Huppertz, H. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 3508–3515.10.1002/ejic.201700464Search in Google Scholar

22. Vitzthum, D.; Bayarjargal, L.; Winkler, B.; Huppertz, H. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57, 5554–5559; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.8b00518.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Fuchs, B.; Huppertz, H. Z. Naturforsch. 2020, 75b, 597–603.10.1515/znb-2020-0070Search in Google Scholar

24. Walker, D.; Carpenter, M. A.; Hitch, C. M. Am. Mineral. 1990, 75, 1020–1028.Search in Google Scholar

25. Walker, D. Am. Mineral. 1991, 76, 1092–1100.10.1007/978-1-4615-3968-1_10Search in Google Scholar

26. Sheldrick, G. M. Sadabs (Version 2016). Bruker AXS Inc.: Madison, Wisconsin (USA), 2016.Search in Google Scholar

27. Krause, L.; Herbst-Irmer, R.; Sheldrick, G. M.; Stalke, D. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2015, 48, 3–10; https://doi.org/10.1107/s1600576714022985.Search in Google Scholar

28. Sheldrick, G. M. Acta Crystallogr. 2015, A71, 3–8.10.1107/S2053273314026370Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

29. Sheldrick, G. M. Shelxt, Integrated Space-Group and Crystal-Structure Determination; University of Göttingen: Göttingen (Germany), 2015.Search in Google Scholar

30. Dolomanov, O. V.; Bourhis, L. J.; Gildea, R. J.; Howard, J. A. K.; Puschmann, H. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2009, 42, 339–341; https://doi.org/10.1107/s0021889808042726.Search in Google Scholar

31. Opus (Version 7.2); Bruker Corporation: Billerica, Massachusetts (USA), 2012.Search in Google Scholar

32. Shannon, R. D. Acta Crystallogr. 1976, A32, 751–767.10.1107/S0567739476001551Search in Google Scholar

33. Zobetz, E. Z. Kristallogr. 1990, 191, 45–58.10.1524/zkri.1990.191.14.45Search in Google Scholar

34. Brese, N. E.; O’Keeffe, M. Acta Crystallogr. 1991, B47, 192–197.10.1107/S0108768190011041Search in Google Scholar

35. Nespolo, M.; Guillot, B. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2016, 49, 317–321; https://doi.org/10.1107/s1600576715024814.Search in Google Scholar

36. Nakamoto, K.; Margoshes, M.; Rundle, R. E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1955, 77, 6480–6486; https://doi.org/10.1021/ja01629a013.Search in Google Scholar

37. Kaindl, R.; Sohr, G.; Huppertz, H. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A 2013, 116, 408–417; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2013.07.072.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

38. Čukanov, N. V.; Chervonnyi, A. D. Infrared Spectroscopy of Minerals and Related Compounds; Springer: Cham (Switzerland), Heidelberg, New York, Dordrecht, London, 2016.10.1007/978-3-319-25349-7Search in Google Scholar

39. Ross, S. D. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A 1972, 28, 1555–1561. https://doi.org/10.1016/0584-8539(72)80126-0.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.