A convenient one-pot approach to the synthesis of novel pyrazino[1,2-a]indoles fused to heterocyclic systems and evaluation of their biological activity as acetylcholinesterase inhibitors

Abstract

Pyrazino[1,2-a]indoles fused with various heterocycles, such as oxazolidine, oxazinane, imidazolidine, hexahydropyrimidine and benzimidazole, were synthesized transition metal-free by domino reactions which involved the condensation of 1-(2-bromoethyl)-3-chloro-1H-indole-2-carbaldehydes 28–31 with various nucleophilic amines, resulting in the formation of two new interesting fused heterocycles. The anticholinesterase, antioxidant and antibacterial activities of the compounds were evaluated. Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibitory activities were tested by Ellman’s assay, antioxidant activities were detected using the 2,2-azinobis[3-ethylbenzthiazoline]-6-sulfonic acid (ABTS•+) free-radical scavenging method and antibacterial activities were determined by agar diffusion tests. The oxazolo-pyrazino[1,2-a]indoles (8, 10), the oxazino-pyrazino[1,2-a]indoles (16, 18, 19), the pyrimido-pyrazino[1,2-a]indole (22), and the benzoimidazo-pyrazino[1,2-a]indole (27) possessed the highest inhibitory activity against AChE with IC50 values in the range 20–40 μg mL−1. The oxazolo-pyrazino[1,2-a]indoles (8, 9), the imidazo-pyrazino[1,2-a]indoles (12, 13), and the benzoimidazo-pyrazino[1,2-a]indole (24) revealed the highest antioxidant values with IC50 values less than 300 μg mL−1. However, the oxazolo-pyrazino[1,2-a]indole (11) and imidazo-pyrazino[1,2-a]indoles (12, 13) exhibited weak to moderate bioactivities against all tested Gram-positive bacteria, namely Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus subtilis and Bacillus cereus.

1 Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is an age-related neurodegenerative disorder of the brain. It is characterized by a progressive neurodegeneration, impairment in cognition, and memory loss which lead ultimately to the death of patients [1]. The level of the acetylcholine (ACh) neurotransmitter responsible for cholinergic transmission is reduced at the cholinergic synapses by the activity of acetylcholinesterase enzyme (AChE) [2]. It rapidly hydrolyzes ACh yielding acetic acid and choline. Currently, therapy of AD is based on the enhancement of the central cholinergic function through improvement of the level of ACh in the brain. AChE inhibitors such as donepezil, galantamine and rivastigmine have been used as symptomatic treatment agents for AD [3]. Therefore, the development of new AChE inhibitors with improved activity and reduced adverse side effects is of great interest in current research.

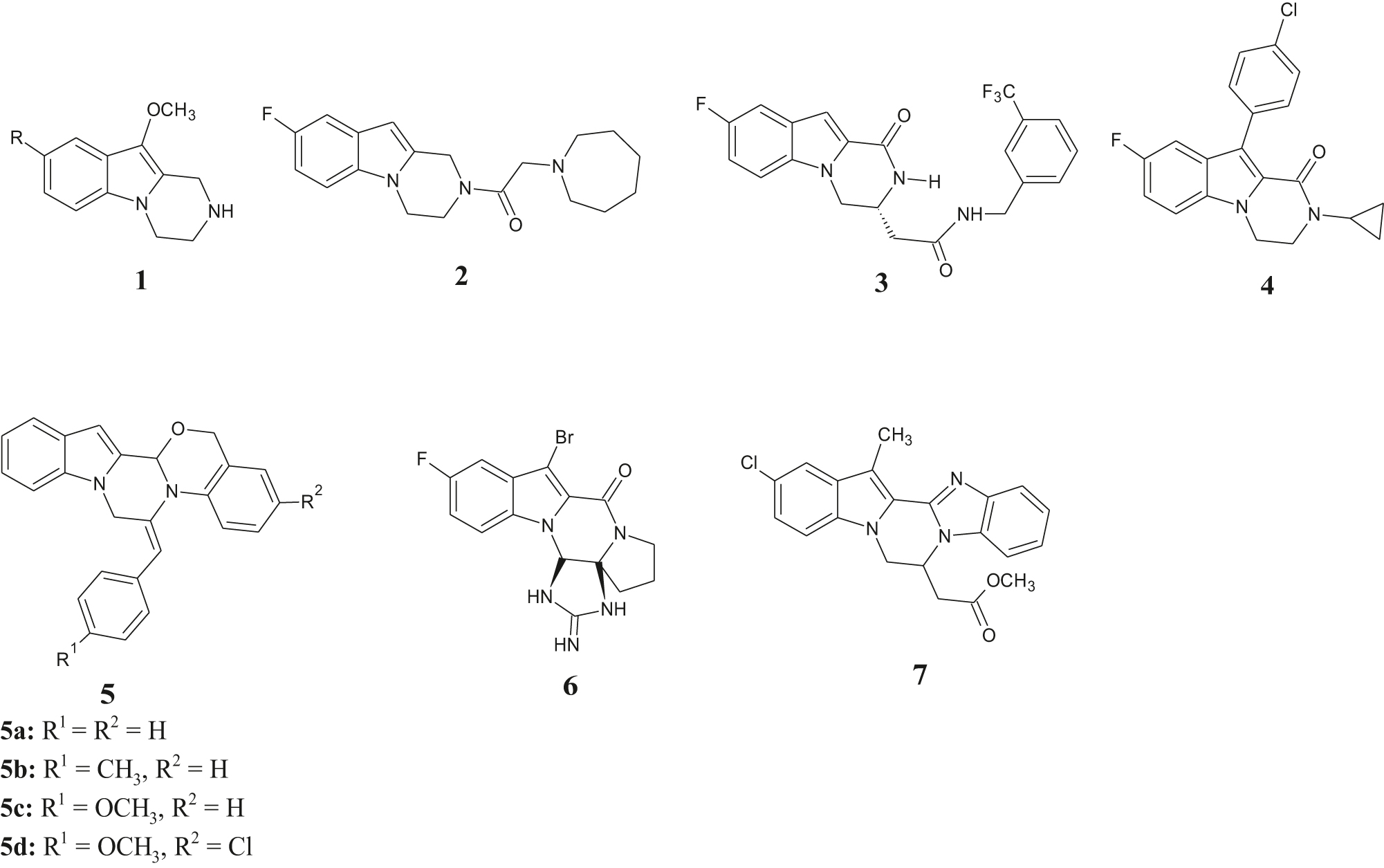

Nitrogen-containing heterocyclic scaffolds are important backbones of compounds with versatile biological activities. The pyrazino[1,2-a]indoles motif is a prominent core scaffold in synthetic bioactive compounds with broad biological activities against a multitude of targets [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15]. Representative examples of bioactive members of this class of compounds are shown in Figure 1.

Representative structures of bioactive indolopyrazine compounds.

Oxazolidines, oxazinanes, imidazolidine, hexahydropyrimidine and benzimidazole moieties are building blocks for several heterocyclic scaffolds that play a central role in biologically active molecules. Some of these moieties and their derivatives exhibited potent inhibitory activity as dual cholinesterase inhibitors [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23].

Although several synthetic methodologies and strategies for the preparation of 1,2,3,4-tetrahydropyrazino[1,2-a]indoles are available in the literature [11, 12, 24–43] their significance in medicinal chemistry warrants the development of new approaches for their synthesis. It was anticipated that new effective molecular scaffolds should result from fusing pyrazino[1,2-a]indoles with other bioactive heterocyclic motifs, such as oxazolidines, oxazinanes, imidazolidine, hexahydropyrimidine or benzimidazole. These new compounds were expected to provide effective potential in anti-AChE activity for the treatment of AD.

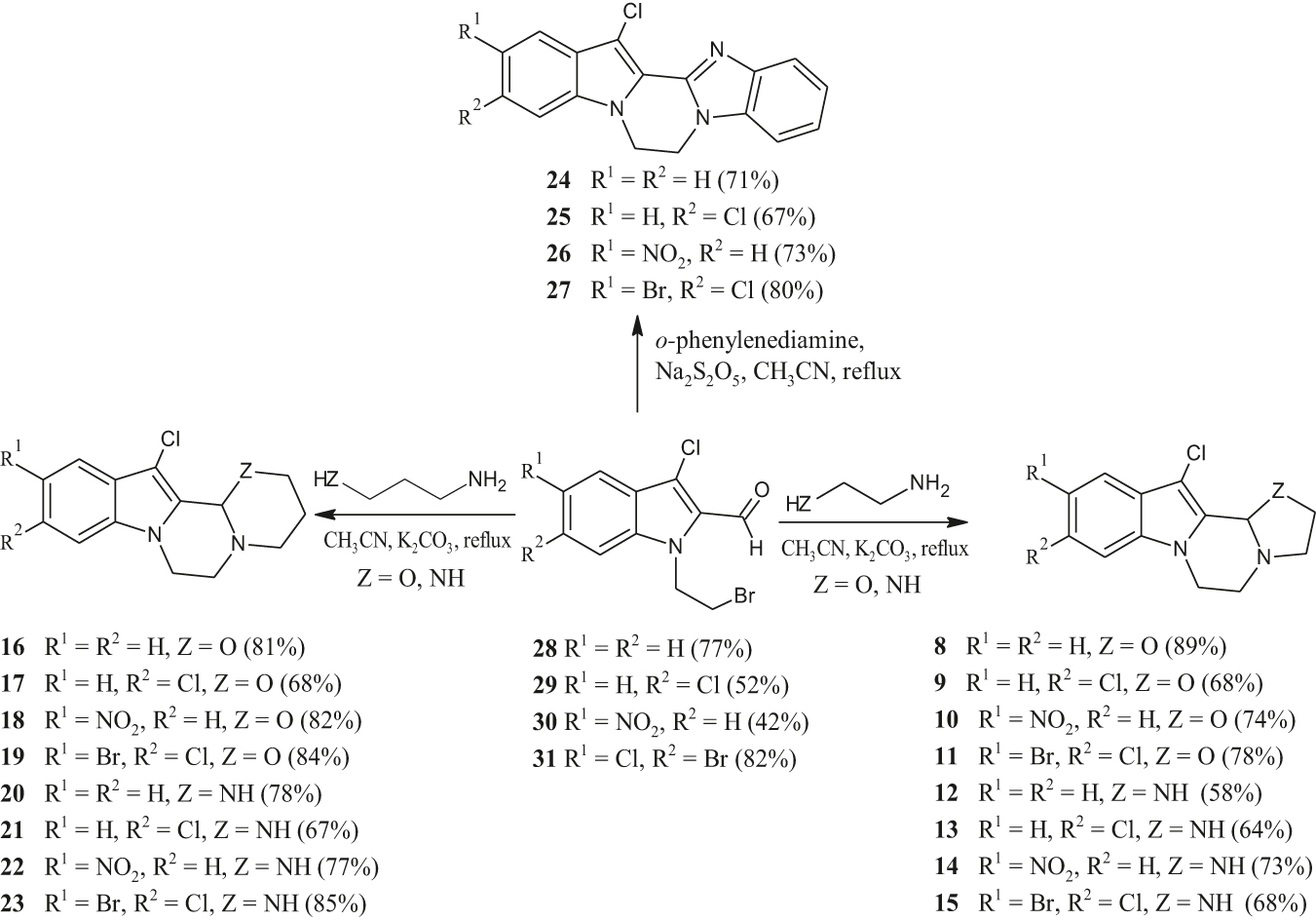

In our current study, we were interested in developing new, general and easy protocols for the synthesis of novel pyrazino[1,2-a]indole scaffolds fused to bioactive heterocycles as outlined above (Scheme 1). The resulting new compounds were evaluated for their antibacterial, antioxidant and AChE inhibitory activity. This was deemed particularly necessary as there are only rare literature studies on their anti-cholinergic and antioxidant activities [44, 45].

Synthetic route for compounds 8–27 and their percentage yields.

2 Results and discussion

2.1 Chemistry

In connection with our ongoing research into the chemistry of nitrogen heterocycles, we were interested in the synthesis of novel pyrazino[1,2-a]indoles fused to heterocycles (Scheme 1; compounds 8–27). The employed synthetic approach was similar to that used for the synthesis of oxazepine derivatives [46], [47], [48]. The synthetic pathway for the preparation of the target compounds (8–27) is shown in Scheme 1. The synthesis of compounds 8–23 involved the condensation of 1-(2-bromoethyl)-3-chloro-1H-indole-2-carbaldehyde 28 and its derivatives 29–31 with ethylenediamine, 2-aminoethanol, 3-amino-1-propanol, or 1,3-diaminopropane in the presence of anhydrous K2CO3 and acetonitrile at reflux temperature. The pyrazino[1,2-a] indoles fused to heterocyclic systems 8–23 are prepared straightforward and in very good yields. On the other hand, condensation of ortho-phenylenediamine with 1-(2-bromoethyl)-3-chloro-1H-indole-2-carbaldehydes 28–31 in the presence of sodium metabisulfite and acetonitrile at reflux temperature produced compounds 24–27 as unique products in a simple one-pot synthesis. Compounds 8–27 were characterized by 1H and 13C NMR, IR and high resolution mass spectroscopy (HRMS). The mass spectra gave the correct molecular ion peaks for which the HRMS data were in a good agreement with the calculated values. Spectral data detailed in the experimental part are consistent with the suggested structures. For compounds 8–11 and 16–19, the signals of the 1H and 13C nuclei of the CHNN segment are sharp singlets around δ = 5.5 and 85 ppm, respectively. On the other hand, for compounds 12–15 and 20–23 these signals appear as sharp singlets at around δ = 4.5–5.0 and 70–72 ppm, respectively. They are strong evidence of the formation of the tetracyclic products. 1H NMR spectra of compounds 24–27 in DMSO-d6 show better resolved signals in the aliphatic range as compared to other compounds. A singlet at about δ = 4.7 ppm corresponds to the four methylene protons of the pyrazine ring. Also, the other signals agree with the proposal structures. To the best of our knowledge, a general procedure for the preparation of these new pyrazino[1,2-a]indoles derivatives has not been reported as yet.

2.2 Evaluation of biological activities

2.2.1 Anticholinesterase activity

AChE inhibitory activities expressed as IC50 values are summarized in Table 1 and Figure 2. The compounds under investigation can be divided into three groups based on their IC50 values. Group I compounds (8, 10, 16, 18, 19, 22, and 27) exhibit the highest inhibitory activity against AChE with IC50 values ranging from 20 to <40 μg mL−1. Group II compounds (11, 12, 14, 15, 24, and 26) have a moderate activity with IC50 values ranging from 40 to 80 μg mL−1 and group III compounds (9, 13, 17, 20, 21, 23, and 25) have only weak activity with values in the range 100–200 μg mL−1.

AChE inhibitory potential and ABTS•+ free-radical scavenging activity of compounds 8–27a.

| Compound | ABTS•+ scavenging IC50 (µg mL−1)b | AChE % inhibition at 100 μg mL−1 | AChE inhibition IC50 (µg mL−1)c |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | 122.3 | 79.3 ± 2.5 | 23.2 ± 1.8 |

| 9 | 301.2 | 33.83 ± 1.5 | 200 ± 2.9 |

| 10 | 543.0 | 74.2 ± 0.2 | 33.4 ± 2.9 |

| 11 | >600 | 60.0 ± 2.4 | 75.3 ± 3.2 |

| 12 | 265.0 | 64.6 ± 2.2 | 42.7 ± 2.3 |

| 13 | 210.4 | 33.2 ± 5.1 | 199.5 ± 4.2 |

| 14 | 377.0 | 67.7 ± 0.9 | 40.6 ± 3.6 |

| 15 | >600 | 58.1 ± 0.1 | 77.1 ± 2.3 |

| 16 | >500 | 70.4 ± 6.9 | 39.3 ± 4.1 |

| 17 | 471.8 | 46.7 ± 2.3 | 119.7 ± 3.7 |

| 18 | >600 | 76.7 ± 0.8 | 28.3 ± 1.3 |

| 19 | 472.3 | 78.9 ± 0.4 | 22.7 ± 3.1 |

| 20 | 504.7 | 35.4 ± 4.6 | 201.8 ± 4.6 |

| 21 | 394.8 | 40.6 ± 3.9 | 137.2 ± 2.6 |

| 22 | >600 | 77.7 ± 1.2 | 25.9 ± 2.1 |

| 23 | >600 | 43.1 ± 2.0 | 129.2 ± 3.1 |

| 24 | 67.0 | 63.2 ± 1.1 | 57.6 ± 3.3 |

| 25 | 559.7 | 38.9.1 ± 3.1 | 159.8 ± 3.5 |

| 26 | >600 | 56.6 ± 1.9 | 78.9 ± 2.1 |

| 27 | >600 | 76.6 ± 4.2 | 32.8 ± 2.4 |

aResults expressed as % inhibition and IC50 values. bThe concentration of a sample scavenging 50% of the radicals. cThe IC50 value is the concentration required to inhibit the control enzyme activity by 50%.

![Figure 2: AChE inhibition and ABTS•+ scavenging values for compounds 8–27. Values in brackets (“[ ]”): IC50 (in μg mL−1) of AChE inhibition; values in parentheses (“( )”):IC50 (in μg mL−1) of ABTS•+ scavenging activities.](/document/doi/10.1515/znb-2020-0205/asset/graphic/j_znb-2020-0205_fig_002.jpg)

AChE inhibition and ABTS•+ scavenging values for compounds 8–27. Values in brackets (“[ ]”): IC50 (in μg mL−1) of AChE inhibition; values in parentheses (“( )”):IC50 (in μg mL−1) of ABTS•+ scavenging activities.

As is shown in Figure 2, the inhibitory potency of the compounds for the AChE enzyme is due to the differences in the type of fused heterocycle rings into the pyrazino[1,2-a]indole moiety and due to the type and position of substituents on the benzene ring. Cheung et al. showed that the size and type of the heterocyclic ring and the nature of the substituents clearly affect the activity of AChE inhibitors [49]. Regarding the substituent effects as shown in Figure 2, it is interesting to note that the compounds 9, 13, 17, 21, and 25 bearing a Cl atom at C-6 of the indole moiety are the least-active compounds against AChE. Introduction of a Br atom at C-5 adjacent to a Cl atom at C-6 causes a great enhancement in the activity (e.g., compounds 11, 15, 19, 23, and 27). On the other hand, a strong electron-withdrawing -NO2 group at C-5 of the indole moiety noticeably enhances the inhibitory potency against AChE (e.g., compounds 10, 14, 18, 22, and 26). These compounds exhibit high-to-moderate inhibitory activity. This observation of a nitro group effect against AChE was also noticed in other AChE inhibitors [21]. We can conclude that introducing substituents at C-5 of the indole moiety results in more potent AChE inhibitors than their counterparts substituted in position 6. Inhibitory effects related to the type of heterocycle fused to the pyrazino[1,2-a]indole ring can be summarized as follows: compounds 20, 21, and 23, but not 22, which has the -NO2 substituent (vide supra), with fused hydropyrimidine rings have poor IC50 values. By contrast, compounds with fused oxazinane rings (16, 18, and 19, but not 17 with a Cl atom at C-6) display high inhibitory effects.

2.2.2 Antioxidant activity

The antioxidant properties of the synthesized compounds was determined by ABTS•+ assay for radical scavenging activity. The results were recorded as IC50 values as is shown in Table 1 and Figure 2. The antioxidant activity can be classified into three groups. High antioxidant activity with IC50 values less than 300 μg mL−1 decreases in the order 24 > 8 > 13 > 12 > 9, moderate antioxidant levels with IC50 between 300 and 600 μg mL−1 is found for compounds 20, 25, 17, 21, 10, 14, and 19, whereas the remainder shows very low antioxidant levels with IC50 > 600 μg mL−1. Compounds 8 and 24 are the most potent compounds having IC50 values of 67.0 and 122.3 μg mL−1, respectively. Interestingly, both of them have no substituent at all on the benzene ring of the indole moiety. In contrast to the observed substituent effects on the AChE inhibitory activity, substituents either at C-5 or both at C-5 + C-6 cause a sharp decrease in the antioxidant activity for most of the compounds under study.

2.2.3 Antibacterial activity

The antibacterial activity of compounds 8–27 against different reference strains of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria is summarized in Table 2. Regarding the antimicrobial activity against Gram-positive bacteria, only compounds 8–15, 21, and 24 have an inhibitory effect against at least one of the tested Gram-positive bacteria. The most effective compounds against Bacillus cereus are 9, 11, and 13. It is worth mentioning that each one of 11, 12, or 13, possessing either oxazolidine or imidazolidine fused rings, exhibit antibacterial activity against the three tested Gram-positive bacteria, while each one of 8, 9, 21, or 24 exhibit activity against only one Gram-positive bacterium. In the concentration range tested, none of the compounds was active against Gram-negative bacteria. These results indicate that compounds 8–15, 21 and 24 are highly selective toward Gram-positive bacteria. The resistance of all Gram-negative bacteria used in this study might be attributed to the presence of outer membrane and lipopolysaccharide barriers to the tested compounds.

Antibacterial activity of compounds 8–15, 21 and 24 against tested bacterial strains.

| Inhibition zone (mm)a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | B. cereus | B. subtilis | S. aureus | E. coli | P. aerogenosa |

| 8 | 14 | – | – | – | – |

| 9 | 22 | – | – | – | – |

| 10 | 9 | – | – | – | – |

| 11 | 17 | 13 | 9 | – | – |

| 12 | 15 | 12 | 13 | – | – |

| 13 | 21 | 13 | 13 | – | – |

| 14 | 15 | – | – | – | – |

| 15 | 9 | – | – | – | – |

| 21 | – | – | 10 | – | – |

| 24 | 10 | – | – | – | – |

a1000 μg per disc.

3 Conclusion

In summary, we have developed a simple and efficient transition metal-free methodology for the synthesis of novel pyrazino[1,2-a]indole derivatives. This approach gives tetracyclic nitrogen-containing heterocycles in moderate to good yields starting from simple, readily available, and cheap educts. The procedure is straightforward and the purification of the products is simple. This method provides a means for the construction of diverse and useful nitrogen-containing tetracyclic compounds which incorporate the bioactive indole motif. The compounds were tested for AChE inhibition, and for their antioxidant and antibacterial activities. Compounds 8, 10, 16, 18, 19, 22, and 27 exhibited the highest inhibitory activity against AChE enzyme with IC50 values ranging from 20 to 40 μg mL−1. Compounds 8 and 24 showed high antioxidant activities with IC50 values 67.0 and 122.3 μg mL−1, respectively. In addition, antibacterial activities are shown for some compounds against Gram-positive bacteria but only with high selectivity.

4 Experimental section

4.1 General information

Silica gel 60 for column chromatography was obtained from Fluka. The progress of the reactions was monitored by thin-layer chromatography (TLC), carried out on TLC sheets that were visualized under UV light (where appropriate). Chromatographic separations were performed on silica gel columns (60–120 mesh, Fluka). Melting points were determined on a Stuart scientific melting point apparatus in open capillary tubes and are uncorrected. 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a 500 MHz spectrometer (Bruker DPX-500) with TMS as internal standard. Chemical shifts (δ values) are given in ppm, whereas J values of 1H–1H coupling constants are given in Hertz. HRMS were obtained (in positive ion mode) using electron spray ion trap (ESI) techniques with a Bruker APEX-4 (7 Tesla) instrument. Samples were dissolved in acetonitrile, diluted with a spray solution (methanol-water 1:1 v/v + 0.1% formic acid) and infused using a syringe pump with a flow rate of 2 μL min−1. External calibration was conducted using arginine cluster in a mass range m/z = 175–871. Acetylcholinesterase (electric eel, Electrophorus electricus AChE), 5,5′-dithiobis [2-nitrobenzoic acid] (DNTB) and acetylthiocholine iodide (ATCI) were obtained from Sigma–Aldrich (USA).

4.2 Synthesis of compounds 28–31

1-(2-bromoethyl)-3-chloro-1H-indole-2-carbaldehyde 28 and its derivatives 29–31 were prepared according to literature procedures [50, 51].

4.2.1 1-(2-Bromoethyl)-3,6-dichloro-1H-indole-2-carbaldehyde (29)

The crude product was purified by column chromatography using ethylacetate-n-hexane (1:9) as eluant to give a colorless solid. Yield: 52%; m. p. 95–97 °C. – IR (KBr disk): ν = 2926, 2856, 1652 (C=O, aldehyde), 1620, 1607, 1508, 1458, 1404, 1336, 1317, 1268, 1223, 1186, 1146, 1057, 1006, 965 cm−1 – 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ = 3.74 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 4.88 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 7.13 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 1H), 7.67 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 1H), 7.96 (d, J = 1 Hz, 1H), 10.02 (s, 1H). – 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 30.1, 47.1, 111.2, 112.2, 117.0, 121.8, 122.0, 128.4, 132.5, 178.6.

4.2.2 1-(2-Bromoethyl)-3-chloro-5-nitro-1H-indole-2-carbaldehyde (30)

The crude product was purified by column chromatography using ethylacetate-n-hexane (1:9) as eluent to give a yellow solid. Yield 42%; m. p. 130–132 °C. – IR (KBr disk): ν = 2928, 2820, 1666 (C=O, aldehyde), 1612, 1576, 1515, 1370, 1330, 1264, 1163, 1076, 1025, 916 cm−1 – 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 3.76 (t, J = 4.5 Hz, 2H), 4.96 (t, J = 4.5 Hz, 2H), 7.63 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 1H), 8.37 (dd, J = 1.8, 6.9 Hz, 1H), 8.78 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 10.25 (s, 1H). – 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 30.3, 46.5, 111.9, 118.3, 122.8, 122.9, 123.7, 130.9, 140.7, 143.2, 181.0.

4.2.3 5-Bromo-1-(2-bromoethyl)-3,6-dichloro-1H-indole-2-carbaldehyde (31)

The crude product was purified by column chromatography using ethylacetate-n-hexane (1.5:8.5) as eluent to give a colorless solid. Yield 82%; m. p. 124–125 °C. – IR (KBr disk): ν = 2926, 2810, 1671 (C=O, aldehyde), 1627, 1453, 1279, 1242, 1197, 1160, 1089, 1022, 962 cm−1 – 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 3.60 (t, J = 4.8 Hz, 2H), 4.73 (t, J = 4.8 Hz, 2H), 7.55 (s, 1H), 7.93 (s, 1H), 10.06 (s, 1H). – 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 30.1, 46.6, 112.1, 115.3, 118.9, 123.6, 124.1, 129.6, 133.8, 137.7, 181.2.

4.3 General procedure for the preparation of pyrazino[1,2-a]indoles 8–23

In a 50 mL one-neck round-bottom flask equipped with a magnetic stirrer bar and a reflux condenser, 1-(2-bromoethyl)-3-chloro-1H-indole-2-carbaldehydes (2 mmol) and anhydrous K2CO3 (0.55 g, 4 mmol) were suspended in anhydrous CH3CN (50 mL). To this well-stirred solution at room temperature solutions of 2-aminoethanol, 3-amino-1-propanol, ethylenediamine, or 1,3-diaminopropane (2 mmol) in dry CH3CN (5 mL) were added dropwise. The reaction mixtures were refluxed with stirring for 24 h. Subsequently they were filtered and the solvents were evaporated. The crude product was purified as indicated below for the individual reactions.

4.3.1 12-Chloro-3,5,6,12b-tetrahydro-2H-oxazolo[2′,3′:3,4]pyrazino[1,2-a]indole (8)

The crude product was purified by washing with methanol to give light yellow solid. Yield 89%; m. p. 133–135 °C (decomp.). – IR (KBr disk): ν = 2930, 2860, 1625, 1571, 1525, 1475, 1448, 1421, 1373, 1336, 1323, 1281, 1234, 1185, 1157, 1072, 1045, 1019, 1004, 984 cm−1 – 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 2.98 (m, 1H), 3.19–3.24 (m, 2H), 3.43–3.50 (m, 1H), 3.88–4.03 (m, 3H), 4.20–4.34 (m, 1H), 5.52 (s, 1H), 7.19 (m, 1H), 7.23–7.29 (m, 2H), 7.62 (m, 1H). – 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 42.1, 45.8, 54.1, 62.6, 85.1, 104.4, 109.4, 118.6, 120.6, 123.1, 125.6, 126.7, 134.4. – HRMS ((+)-ESI): m/z = 249.0778 (calcd. 249.0795 for C13H14ClN2O [M+H]+).

4.3.2 9,12-Dichloro-3,5,6,12b-tetrahydro-2H-oxazolo[2′,3′:3,4]pyrazino[1,2-a]indole (9)

The crude product was purified by column chromatography using ethylacetate to give pale yellow solid. Yield 68%; m. p. 118–120 °C. – IR (KBr disk): ν = 2927, 2830, 1622, 1568, 1526, 1472, 1445, 1420, 1361, 1327, 1285, 1230, 1203, 1158, 1076, 1020, 962 cm−1 – 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 3.02 (m, 1H), 3.20–3.30 (m, 2H), 3.46–3.54 (m, 1H), 3.92–4.08 (m, 3H), 4.17–4.20 (m, 1H), 5.52 (s, 1H), 7.17 (dd, J = 1.2, 6.3 Hz, 1H), 7.31 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.56 (d, J = 6.3 Hz, 1H). – 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 42.2, 45.6, 54.1, 63.6, 84.9, 104.6, 108.8, 118.6, 120.5, 123.3, 125.4, 126.9, 134.5. – HRMS ((+)-ESI): m/z = 283.0407 (calcd. 283.0405 for C13H13Cl2N2O [M+H]+).

4.3.3 10-Nitro-12-chloro-3,5,6,12b-tetrahydro-2H-oxazolo[2′,3′:3,4]pyrazino[1,2-a]indole (10)

The crude product was purified by washing with methanol to give yellow solid. Yield 74%; m. p. 165–167 °C (decomp.). – IR (KBr disk): ν = 2928, 2810, 1619, 1576, 1510, 1468, 1420, 1376, 1328, 1280, 1234, 1181, 1158, 1070, 1017, 985 cm−1 – 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 3.06–3.11 (m, 1H), 3.23–3.33 (m, 2H), 3.49–3.56 (m, 1H), 3.95–4.15 (m, 3H), 4.29–4.33 (m, 1H), 5.54 (s, 1H), 7.37 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 1H), 8.18 (dd, J = 1.2, 6.9 Hz, 1H), 8.63 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 1H). – 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 42.4, 45.8, 54.5, 63.9, 85.0, 107.0, 108.7, 116.5, 118.4, 125.5, 129.9, 137.4, 142.2. – HRMS ((+)-ESI): m/z = 294.0635 (calcd. 294.0645 for C13H13ClN3O3 [M+H]+).

4.3.4 10-Bromo-9,12-dichloro-3,5,6,12b-tetrahydro-2H-oxazolo[2′,3′:3,4]pyrazino[1,2-a]indole (11)

The crude product was purified by column chromatography using ethylacetate to give beige solid. Yield 78%; m. p. 138–140 °C (decomp.). – IR (KBr disk): ν = 2928, 2830, 1625, 1570, 1526, 1472, 1447, 1418, 1361, 1261, 1236, 1156, 1145, 1119, 1046, 990 cm−1. – 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 2.92–2.95 (m, 1H), 3.09–3.21 (m, 2H), 3.36–3.44 (m, 1H), 3.83–3.98 (m, 3H), 4.05–4.08 (m, 1H), 5.40 (s, 1H), 7.34 (s, 1H), 7.30 (s, 1H). – 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 42.2, 42.4, 54.0, 62.7, 84.8, 103.8, 111.1, 114.2, 123.4, 125.6, 128.7, 128.8, 133.6. – HRMS ((+)-ESI): m/z = 360.9490 (calcd. 360.9510 for C13H12BrCl2N2O [M+H]+).

4.3.5 12-Chloro-1,2,3,5,6,12b-hexahydroimidazo[2′,1′:3,4]pyrazino[1,2-a]indole (12)

The crude product was purified by column chromatography using CHCl3–CH3OH (9.5:0.5) to give brown oily product. Yield 58%. – IR (KBr disk): ν = 3316 (NH), 2926, 2835, 1647 1542, 1450, 1424, 1359, 1321, 1222, 1180, 1122, 1093, 1063, 1019, 976 cm−1. – 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 2.99 (br, 1H, NH), 3.06–3.09 (m, 2H), 3.15–3.25 (m, 4H), 4.07–4.10 (m, 2H), 5.05 (s, 1H), 7.19–7.31 (m, 3H), 7.64 (d, J = 5.7 Hz, 1H). – 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 41.6, 43.8, 45.6, 53.2, 71.2, 102.7, 108.4, 118.1, 120.6, 120.7, 125.5, 128.9, 134.4. – HRMS ((+)-ESI): m/z = 248.0938 (calcd. 248.0954 for C13H15ClN3 [M+H]+).

4.3.6 9,12-Dichloro-1,2,3,5,6,12b-hexahydroimidazo[2′,1′:3,4]pyrazino[1,2-a]indole (13)

The crude product was purified by column chromatography using ethylacetate-CH3OH (7.5:2.5) to give light brown solid. Yield 64%; m. p. 72–73 °C. – IR (KBr disk): ν = 3257 (NH), 2927, 2827, 1629, 1609, 1540, 1451, 1327, 1216, 1125, 1092, 1069, 970 cm−1. – 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 2.98–3.31 (m, 7H), 3.93–4.08 (br, 2H), 4.91 (s, 1H), 7.08 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.19 (s, 1H), 7.43 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H). – 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 41.7, 43.6, 45.4, 53.1, 71.0, 102.7, 109.4, 119.1, 121.3, 124.1, 128.6, 129.9, 134.6. – HRMS ((+)-ESI): m/z = 282.0541 (calcd. 282.0564 for C13H14Cl2N3 [M+H]+).

4.3.7 10-Nitro-12-chloro-1,2,3,5,6,12b-hexahydroimidazo[2′,1′:3,4]pyrazino[1,2-a]indole (14)

The crude product was purified by column chromatography using ethylacetate-n-hexane (6:4) to give pale brown solid. Yield 73%; m. p. 170–172 °C. – IR (KBr disk): ν = 3307 (NH), 2926, 1621, 1572, 1519, 1469, 1420, 1330, 1248, 1203, 1176, 1070, 1036, 980 cm−1. – 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 2.10 (br, 2H), 3.44 (br, 5H), 4.15 (br, 2H), 5.05 (s, 1H), 7.33 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H), 8.12 (dd, J = 1.8, 6.6 Hz, 1H), 8.55 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H). – 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 42.1, 43.4, 45.1, 53.3, 71.8, 105.5, 109.2, 118.4, 119.3, 124.8, 133.2, 137.7, 143.6. – HRMS ((+)-ESI): m/z = 293.0806 (calcd. 293.0805 for C13H14ClN4O2 [M+H]+).

4.3.8 10-Bromo-9,12-dichloro-1,2,3,5,6,12b-hexahydroimidazo[2′,1′:3,4]pyrazino[1,2-a]indole (15)

The crude product was purified by column chromatography using ethylacetate-CH3OH (7:3) to give pale brown solid. Yield 68%; m. p. 130–132 °C. – IR (KBr disk): ν = 3310 (NH), 2928, 1625, 1527, 1473, 1446, 1418, 1358, 1236, 1204, 1161, 1088, 1041, 991 cm−1. – 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 2.14 (br, 1H, NH), 3.03–3.31 (m, 6H), 3.99–4.12 (m, 2H), 4.99 (s, 1H), 7.41 (s, 1H), 7.85 (s, 1H). – 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 41.8, 43.7, 45.4, 54.1, 70.9, 101.9, 110.9, 114.1, 122.6, 125.3, 128.2, 131.5, 133.5. – HRMS ((+)-ESI): m/z = 359.9667 (calcd. 359.9669 for C13H13BrCl2N3 [M+H]+).

4.3.9 13-Chloro-2,3,4,6,7,13b-hexahydro-[1,3]oxazino[2′,3′:3,4]pyrazino[1,2-a]indole (16)

The crude product was purified by washing with diethylether to give light brown solid. Yield 81%; m. p. 90–91 °C. – IR (KBr disk): ν = 2926, 2857, 1626, 1570, 1526, 1474, 1447, 1422, 1369, 1303, 1232, 1161, 1125, 1080, 1044, 963 cm−1. – 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 1.24 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 2.17–2.27 (m, 1H), 2.83–2.88 (m, 1H), 3.19–3.22 (m, 1H), 3.38–3.46 (m, 1H), 3.88–4.00 (m, 2H), 4.01–4.06 (m, 1H), 4.16–4.29 (m, 2H), 5.56 (s, 1H), 7.15 (t, J = 4.5 Hz, 1H), 7.20–7.27 (m, 2H), 7.59 (t, J = 4.6 Hz, 1H). – 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 20.8, 42.5, 42.9, 52.4, 68.3, 82.4, 102.5, 109.2, 118.5, 120.4, 122.7, 125.5, 128.9, 134.3. – HRMS ((+)-ESI): m/z = 263.0935 (calcd. 263.0951 for C14H16ClN2O [M+H]+).

4.3.10 10,13-Dichloro-2,3,4,6,7,13b-hexahydro-[1,3]oxazino[2′,3′:3,4]pyrazino[1,2-a]indole (17)

The crude product was purified by washing with diethylether to give light yellow solid. Yield 68%; m. p. 110–111 °C. – IR (KBr disk): ν = 2926, 2856, 1624, 1568, 1526, 1481, 1424, 1371, 1303, 1206, 1161, 1127, 1081, 1044, 980 cm−1. – 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 1.29 (d, J = 9.9 Hz, 1H), 2.22–2.28 (m, 1H), 2.88–2.90 (m, 1H), 3.22–3.27 (m, 1H), 3.40–3.48 (m, 1H), 3.92–3.95 (m, 2H), 4.03–4.27 (m, 3H), 5.58 (s, 1H), 7.15 (dd, J = 0.9, 6.6 Hz, 1H), 7.29 (d, J = 0.9 Hz, 1H), 7.53 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H). – 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 20.7, 42.6, 42.7, 52.3, 68.3, 82.3, 102.8, 109.4, 119.5, 121.2, 124.1, 128.7, 129.6, 134.6. – HRMS ((+)-ESI): m/z = 297.0557 (calcd. 297.0561 for C14H15Cl2N2O [M+H]+).

4.3.11 11-Nitro-13-chloro-2,3,4,6,7,13b-hexahydro-[1,3]oxazino[2′,3′:3,4]pyrazino[1,2-a]indole (18)

The crude product was purified by washing with methanol to give yellow solid. Yield 82%; m. p. 174–176 °C. – IR (KBr disk): ν = 2928, 2854, 1620, 1572, 1509, 1471, 1447, 1421, 1375, 1325, 1298, 1243, 1160, 1071, 1048, 979, 915 cm−1. – 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 1.32 (d, J = 10.2 Hz, 1H), 2.23–2.31 (m, 1H), 2.91–2.95 (m, 1H), 3.24–3.28 (m, 1H), 3.41–3.48 (m, 1H), 3.90–4.11 (m, 3H), 4.24–4.28 (m, 2H), 5.58 (s, 1H), 7.32 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H), 8.13 (dd, J = 1.5, 6.6 Hz, 1H), 8.58 (d, J = 1.5 Hz, 1H). – 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 20.8, 42.7, 42.8, 52.5, 68.6, 82.5, 104.2, 108.1, 116.5, 117.2, 124.0, 132.0, 136.2, 142.1. HRMS ((+)-ESI): m/z = 308.0791 (calcd. 308.0801 for C14H15ClN3O3 [M+H]+).

4.3.12 11-Bromo-10,13-dichloro-2,3,4,6,7,13b-hexahydro-[1,3]oxazino[2′,3′:3,4] pyrazino [1,2-a]indole (19)

The crude product was purified by washing with methanol to give pale brown solid. Yield 84%; m. p. 164–166 °C. – IR (KBr disk): ν = 2927, 2856, 1625, 1570, 1525, 1476, 1444, 1418, 1366, 1302, 1234, 1205, 1159, 1124, 1084, 1041, 978 cm−1. – 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 1.30 (d, J = 10.2 Hz, 1H), 2.22–2.28 (m, 1H), 2.87–2.90 (m, 1H), 3.22–3.27 (m, 1H), 3.39–3.47 (m, 1H), 3.88–3.96 (m, 2H), 4.04–4.15 (m, 2H), 4.23–4.27 (m, 1H), 5.55 (s, 1H), 7.42 (s, 1H), 7.87 (s, 1H). – 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 20.5, 42.6, 42.9, 52.3, 68.4, 83.2, 102.0, 110.8, 113.8, 122.9, 123.6, 128.4, 130.7, 133.9. – HRMS ((+)-ESI): m/z = 374.9664 (calcd. 374.9666 for C14H14Cl2BrN2O [M+H]+).

4.3.13 13-Chloro-2,3,4,6,7,13b-hexahydro-1H-pyrimido[2′,1′:3,4]pyrazino[1,2-a]indole (20)

The crude product was purified by column chromatography using ethylacetate-CH3OH (9.5:0.5) to give light yellow solid. Yield 78%; m. p. 71–72 °C. – IR (KBr disk): ν = 3310 (NH), 2929, 1625, 1570, 1526, 1471, 1447, 1421, 1363, 1319, 1281, 1212, 1159, 1083, 1021, 979 cm−1. – 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 1.49 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 1.87–1.95 (m, 2H), 2.77–2.84 (m, 2H), 2.96–3.02 (m, 1H), 3.12–3.14 (m, 1H), 3.24–3.32 (m, 1H), 3.33–3.35 (m, 1H), 3.99–4.09 (m, 1H), 4.10–4.14 (m, 1H), 4.63 (s, 1H), 7.15 (t, J = 4.6 Hz, 1H), 7.19–7.23 (m, 2H), 7.56 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H). – 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 24.5, 42.4, 45.5, 47.4, 54.3, 72.3, 100.9, 109.0, 118.1, 120.3, 122.4, 125.8, 130.2, 134.2. – HRMS ((+)-ESI): m/z = 262.1112 (calcd. 262.1111 for C14H17ClN3 [M+H]+).

4.3.14 10,13-Dichloro-2,3,4,6,7,13b-hexahydro-1H-pyrimido[2′,1′:3,4]pyrazino[1,2-a]indole (21)

The crude product was purified by washing with diethylether to give light yellow solid. Yield 67%; m. p. 93–94 °C. – IR (KBr disk): ν = 3308 (NH), 2928, 1622, 1569, 1526, 1451, 1422, 1359, 1283, 1209, 1157, 1120, 1099, 1022, 989 cm−1. – 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 1.52–1.56 (m, 1H), 1.92–1.96 (m, 2H), 2.80–2.88 (m, 2H), 2.99–3.05 (m, 1H), 3.15–3.19 (m, 1H), 3.26–3.30 (m, 1H), 3.31–3.40 (m, 1H), 3.97–4.00 (m, 1H), 4.07–4.12 (m, 1H), 4.63 (s, 1H), 7.14 (dd, J = 1.2, 6.5 Hz, 1H), 7.26 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.50 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 1H). – 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 24.4, 42.8, 45.6, 47.8, 54.4, 72.2, 101.1, 109.4, 119.4, 121.1, 125.6, 128.9, 131.1, 135.6. – HRMS ((+)-ESI): m/z = 296.0722 (calcd. 296.0721 for C14H16Cl2N3 [M+H]+).

4.3.15 11-Nitro-13-chloro-2,3,4,6,7,13b-hexahydro-1H-pyrimido[2′,1′:3,4]pyrazino[1,2-a]indole (22)

The crude product was purified by washing with ethylacetate to give yellow solid. Yield 77%; m. p. 162–164 °C. – IR (KBr disk): ν = 3312 (NH), 2927, 2855, 1620, 1575, 1514, 1471, 1447, 1365, 1278, 1244, 1208, 1158, 1072, 980 cm−1. – 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 1.54–1.58 (m, 1H), 1.89–1.97 (m, 2H), 2.83–2.91 (m, 2H), 3.00–3.07 (m, 1H), 3.17–3.21 (m, 1H), 3.28–3.21 (m, 1H), 3.29–3.42 (m, 1H), 4.09–4.11 (m, 1H), 4.13–4.23 (m, 1H), 4.67 (s, 1H), 7.28 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H), 8.10 (dd, J = 1.5, 6.5 Hz, 1H), 8.53 (d, J = 1.5 Hz, 1H). – 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 24.6, 43.3, 45.6, 47.7, 54.5, 72.2, 104.5, 109.4, 116.0, 118.3, 125.6, 133.9, 137.2, 141.7. – HRMS ((+)-ESI): m/z = 307.0969 (calcd. 307.0962 for C14H16ClN4O2 [M+H]+).

4.3.16 11-Bromo-10,13-dichloro-2,3,4,6,7,13b-hexahydro-1H-pyrimido[2′,1′:3,4]pyrazino [1,2-a]indole (23)

The crude product was purified by column chromatography using ethylacetate-CH3OH (9:1) to give pale brown solid. Yield 85%; m. p. 125–126 °C. – IR (KBr disk): ν = 3309 (NH), 2926, 1626, 1526, 1447, 1420, 1355, 1212, 1088, 1046, 979 cm−1. – 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 1.44 (d, J = 9.9 Hz, 1H), 1.83–1.89 (m, 1H), 2.41 (br, 1H, NH), 2.71–2.80 (m, 2H), 3.89–2.96 (m, 1H), 3.07–3.10 (m, 1H), 3.18–3.21 (m, 1H), 3.28–3.33 (m, 1H), 3.85–3.90 (m, 1H), 3.98–4.03 (m, 1H), 4.56 (s, 1H), 7.28 (s, 1H), 7.73 (s, 1H). – 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 24.2, 42.5, 45.9, 47.0, 54.1, 71.8, 100.4, 110.7, 113.8, 122.6, 125.9, 128.0, 132.8, 133.5. – HRMS ((+)-ESI): m/z = 373.9817 (calcd. 373.9826 for C14H15Cl2BrN3 [M+H]+).

4.4 General procedure for the preparation of pyrazino[1,2-a]indoles 24–27

In a 50 mL one-neck round-bottom flask equipped with a magnetic stirrer bar, a reflux condenser, 1-(2-bromoethyl)-3-chloro-1H-indole-2-carbaldehydes (2 mmol) and Na2S2O5 (4 mmol) in 20 ml of anhydrous CH3CN was added a CH3CN solution of ortho-phenylenediamine (2 mmol) at room temperature gradually. The reaction mixture was refluxed with stirring for 24–48 h. The reaction mixture was filtered after cooling, and the crude product was purified as indicated for the individual reactions below.

4.4.1 14-Chloro-6,7-dihydrobenzo[4′,5′]imidazo[2′,1′:3,4]pyrazino[1,2-a]indole (24)

The reaction mixture was filtered after cooling and the solid on the Buchner funnel was washed with excess water to remove the oxidizing agent Na2S2O5 and then with methanol to give pale yellow solid. Yield 71%; m. p. >250 °C (decomp.). – IR (KBr disk): ν = 2928, 1623, 1571, 1526, 1472, 1415, 1321, 1235, 1162, 1083, 1025, 918 cm−1. – 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 4.65(s, 4H), 7.21–7.35 (m, 4H), 7.60–7.74 (m, 4H). – 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 47.6, 60.8, 110.7, 111.4, 118.7, 119.8, 121.7, 122.9, 123.2, 123.4, 125.0, 125.9, 134.1, 135.7, 142.6, 144.1. – HRMS ((+)-ESI): m/z = 294.0789 (calcd. 294.0798 for C17H13ClN3 [M+H]+).

4.4.2 3,14-Dichloro-6,7-dihydrobenzo[4′,5′]imidazo[2′,1′:3,4]pyrazino[1,2-a]indole (25)

The reaction mixture was filtered after cooling and the solid on the Buchner funnel was washed with water and then with acetonitrile and chloroform to give pale yellow solid. Yield 67%; m. p. >255 °C (decomp.). – IR (KBr disk): ν = 2927, 1624, 1523, 1473, 1422, 1365, 1279, 1237, 1203, 1160, 1089, 1069, 1022, 918 cm−1. – 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 4.66 (s, 4H), 7.22–7.29 (br, 3H), 7.59–7.72 (m, 3H), 7.87 (s, 1H). – 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 43.6, 60.8, 104.1, 110.8, 111.5, 119.8, 120.2, 122.1, 123.0, 123.6, 124.2, 124.7, 129.8, 134.1, 136.0, 142.2, 144.1. – HRMS ((+)-ESI): m/z = 328.03728 (calcd. 328.0408 for C17H12Cl2N3 [M+H]+).

4.4.3 2-Nitro-14-chloro-6,7-dihydrobenzo[4′,5′]imidazo[2′,1′:3,4]pyrazino[1,2-a]indole (26)

The reaction mixture was filtered after cooling and the solid on the Buchner funnel was washed with water and then with methanol to give dark yellow solid. Yield 73%; m. p. >265 °C (decomp.). – IR (KBr disk): ν = 2926, 1623, 1575, 1521, 1475, 1445, 1370, 1324, 1302, 1235, 1205, 1162, 1085, 1044, 884 cm−1. – 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 4.79 (br, 4H), 7.34 (br, 2H), 7.56–7.80 (m, 2H), 7.93 (br, 1H), 8.21 (br, 1H), 8.49 (br, 1H). Due to poor solubility of the compound in CDCl3 as well as in DMSO-d6, we were unable to record 13C NMR spectra. – HRMS ((+)-ESI): m/z = 339.0654 (calcd. 339.0648 for C17H12ClN4O2 [M+H]+).

4.4.4 2-Bromo-3,14-dichloro-6,7-dihydrobenzo[4′,5′]imidazo[2′,1′:3,4]pyrazino[1,2-a]indole (27)

The reaction mixture was filtered after cooling and the solid on the Buchner funnel was washed with water and then with methanol to give pale brown solid. Yield 80%; m. p. >275 °C (decomp.). – IR (KBr disk): ν = 2927, 1624, 1526, 1472, 1359, 1248, 1204, 1159, 1095, 1076, 1024, 955 cm−1. – 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 4.72 (s, 4H), 7.30–7.37 (m, 2H), 7.71 (d, J = 6 Hz, 1H), 7.80 (d, J = 6 Hz, 1H), 8.00 (s, 1H), 8.20 (s, 1H). Due to poor solubility of the compound in CDCl3 as well as in DMSO-d6, we were unable to record 13C NMR spectra. – HRMS ((+)-ESI): m/z = 405.9508 (calcd. 405.9513 for C17H11BrCl2N3 [M+H]+).

4.5 Biological evaluation

4.5.1 Inhibition of acetylcholine esterase activity

AChE inhibitory activities of synthesized compounds were measured by slightly modifying Ellman assay [52]. In this assay, AChE inhibitory activity is indirectly measured via reduction of acetylthiocholine iodide breakdown. Three hundred microliters of 200 mm phosphate buffer (pH 8.0), 5 µL of AChE (5 IU mL−1), 50 µL of 5 mm 5,5-dithio-bis(2-nitrobenzoic acid (DTNB)) and (+/−)10 µL of synthetic compounds solution at different concentrations were mixed and incubated for 20 min at 25 °C. The reaction was then initiated by adding 2 µL of 4 mm acetylthiocholine iodide. The reaction of thiocholine with DNTB was monitored at 412 nm, utilizing a 96-well microplate reader (Bio-Tek ELx800UV, USA). The results were recorded as IC50, which indicate that 50% of enzyme of activity was decreased.

The AChE activity was calculated according to the following equation:

4.5.2 ABTS•+ assay

The ABTS•+ scavenging ability of the synthetic compounds was measured according to a recently reported method [53] with slight modifications. The stock solutions included 7 mm ABTS•+ solution and 2.4 mm potassium persulfate solution. The working solution was then prepared by mixing the two stock solutions in equal quantities and allowing them to react for 14 h at room temperature in the dark. The starting solution ABTS•+ should have an A = 0.70, as recommended [54] at λ = 734 nm using a spectrophotometer. Fresh ABTS•+ radical was freshly prepared. To 1.0 mL ABTS•+, different concentrations from 50 to 500 μg mL−1 of synthetic compounds were added and left in dark for 10 min, and then the absorbance was measured at λ = 734 nm. The percentage inhibition of ABTS•+ was calculated using the following formula:

where Abscontrol is the absorbance of ABTS•+ radical in methanol and Abssample is the absorbance of ABTS•+ radical solution mixed with sample. All determinations were performed in triplicate (n = 3). ABTS•+ free radical scavenging activity of each sample was expressed as IC50 (IC50: the sample concentration providing 50% ABTS•+ inhibition).

4.5.3 Antibacterial activity

Antibacterial activities of synthesized compounds were determined by agar diffusion test according to the standard methods followed in Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI, 2012) [55]. One milligram of tested compounds was applied on a 6 mm sterile blank filter disk, which was placed on the top of Muller Hinton Agar plates (Oxoid, UK). The plates were seeded with bacterial test strain at a cell density of 106 cells per mL. Five strains were included: the Gram-negative bacteria [Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ATCC 13048) and Escherichia coli (ATCC 25922)] and the Gram-positive bacteria [Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 43300), Bacillus subtilis (ATCC 6633) and B. cereus (ATCC 11778)]. The results are presented as means of three independent tests.

5 Supporting information

Copies of the 1H and 13C NMR spectra are given as supplementary material available online (https://doi.org/10.1515/znb-2020-0205).

Acknowledgment

The Chemistry Department of the University of Jordan-Amman is gratefully acknowledged for measuring the NMR, HRMS and IR spectra.

Author contributions: All the authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this submitted manuscript and approved submission.

Research funding: None declared.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding this article.

References

1. Walsh, D. M., Selkoe, D. J. Neuron 2004, 44, 181–193; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2004.09.010.Search in Google Scholar

2. Francis, P. T., Palmer, A. M., Snape, M., Wilcock, G. K. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1999, 66, 137–147; https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.66.2.137.Search in Google Scholar

3. Muñoz-Torrero, D. Curr. Med. Chem. 2008, 15, 2433–2455.10.2174/092986708785909067Search in Google Scholar

4. Commons, T. J., Laclair, C. M., Christman, S. PCT Int. Appl. WO 9612721, 1996. Chem. Abstr. 1996, 125, 114494u.Search in Google Scholar

5. Freed, M. E. US. Pat. 4022778, May 10, 1977. Chem. Abstr. 1977, 87, 68421q.10.1007/BF03285157Search in Google Scholar

6. Mokrosz, J. L., Duszynska, B., Paluchowska, M. H. Arch. Pharm. 1994, 8, 529–531; https://doi.org/10.1002/ardp.19943270811.Search in Google Scholar

7. Ruppelt, M., Bartel, S., Guarnieri, W., Raddatz, S., Rosentreter, U., Wild, H., Endermann, R., Kroll, H. P. Chem Abstr. 1999, 131, 129985.Search in Google Scholar

8. Basanagoudar, L. D., Mahajanshetti, C. S., Hendi, S. B., Dambal, S. B. Indian J. Chem. 1991, B30, 1014–1017.Search in Google Scholar

9. Bit, R. A., Davis, P. D., Elliott, L. H., Harris, W., Hill, C. H., Keech, E., Kumar, H., Lowton, G., Maw, A., Nixon, J. S., Vesey, D. R., Wadsworth, J., Wilkinson, S. E. J. Med. Chem. 1993, 36, 21–29; https://doi.org/10.1021/jm00053a003.Search in Google Scholar

10. Chang-Fong, J., Addo, J., Dukat, M., Smith, C., Mitchell, N. A., Herrick-Davis, K., Teitler, M., Glennon, R. A. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 2002, 12, 155–158; https://doi.org/10.1016/s0960-894x(01)00713-2.Search in Google Scholar

11. Bös, M., Jenck, F., Martin, J. R., Moreau, J. L., Mutel, V., Sleight, A. J., Widmer, U. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 1997, 32, 253–261; https://doi.org/10.1016/s0223-5234(97)83976-1.Search in Google Scholar

12. Romagnoli, R., Baraldi, P. G., Carrion, M. D., Cruz-Lopez, O., Cara, C. L., Delia, P., Mojgan, A. T., Jan, B., Ernest, H., Enirca, F., Roberto, G. Lett. Drug Des. Discov. 2009, 6, 298–303; https://doi.org/10.2174/157018009788452519.Search in Google Scholar

13. Tiwari, R. K., Verma, A. K., Chhillar, A. K., Singh, D., Singh, J., Snakar, V. K., Yadav, V., Sharma, G. L., Chandra, R. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2006, 14, 2747–2752; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmc.2005.11.054.Search in Google Scholar

14. Tiwari, R. K., Singh, D., Singh, J., Yadav, V., Pathak, A. K., Dabur, R., Chhillar, A. K., Singh, R., Sharma, G. L., Chandra, R., Verma, A. K. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006, 16, 413–416; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.09.066.Search in Google Scholar

15. Kim, Y. J., Pyo, J. S., Jungb, Y.-S., Kwak, J.-H. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2017, 27, 607–611; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmcl.2016.12.006.Search in Google Scholar

16. Mashkovskii, M. D., Glushkov, R. G. Pharm. Chem. J. 2001, 35, 179–182; https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1010474325601.10.1023/A:1010474325601Search in Google Scholar

17. Jamil, M., Sultana, N., Ashraf, R., Sarfraz, M., Tariq, M. I., Mustaqeem, M. Trop. J. Pharmaceut. Res. 2018, 17, 451–459; https://doi.org/10.4314/tjpr.v17i3.10.Search in Google Scholar

18. Sangi, D. P., Monteiro, J. L., Vanzolini, K. L., Cass, Q. B., Paixão, M. W., Corrêa, A. G. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2014, 25, 887–889.Search in Google Scholar

19. Ahmad, S., Iftikhar, F., Ullah, F., Sadiq, A., Rashid, U. Bioorg. Chem. 2016, 69, 91–101; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioorg.2016.10.002.Search in Google Scholar

20. Coban, G., Carlino, L., Tarikogullari, A. H., Parlar, S., Sarıkaya, G., Alptüzün, V., Alpan, A. S., Güneş, H. S., Erciyas, E. Med. Chem. Res. 2016, 25, 2005–2014; https://doi.org/10.1007/s00044-016-1648-1.Search in Google Scholar

21. Alpan, A. S., Sarıkaya, G., Çoban, G., Parlar, S., Armagan, G., Alptüzün, V. Arch. Pharm. (Weinheim, Ger.) 2017, 350, e1600351; https://doi.org/10.1002/ardp.201600351.Search in Google Scholar

22. Yanovsky, I., Finkin-Groner, E., Zaikin, A., Lerman, L., Shalom, H., Zeeli, S., Weil, T., Ginsburg, I., Nudelman, A., Weinstock, M. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 10700–10715; https://doi.org/10.1021/jm301411g.Search in Google Scholar

23. Zhu, J., Wu, C.-F., Li, X., Wu, G.-S., Xie, S., Hu, Q.-N., Deng, Z., Zhu, M. X., Luo, H.-R., Hong, X. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2013, 21, 4218–4224; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmc.2013.05.001.Search in Google Scholar

24. Abbiati, G., Arcadi, A., Beccalli, E., Rossi, E. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003, 44, 5331–5334; https://doi.org/10.1016/s0040-4039(03)01202-4.Search in Google Scholar

25. Abbiati, G., Arcadi, A., Bellinazzi, A., Beccalli, E., Rossi, E., Zanzola, S. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 70, 4088–4095; https://doi.org/10.1021/jo0502246.Search in Google Scholar

26. Nayak, M., Pandey, G., Batra, S. Tetrahedron 2011, 67, 7563–7569; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tet.2011.07.074.Search in Google Scholar

27. Toche, R., Chavan, S., Janrao, R. Monatsh. Chem. 2014, 145, 1507–1512; https://doi.org/10.1007/s00706-014-1216-7.Search in Google Scholar

28. Guven, S., Ozer, M. S., Kaya, S., Menges, N., Balci, M. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 2660–2663; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.orglett.5b01041.Search in Google Scholar

29. Zhu, Y.-P., Liu, M.-C., Cai, Q., Jia, F.-C., Wu, A.-X. Chem. Eur J. 2013, 19, 10132–10137; https://doi.org/10.1002/chem.201301734.Search in Google Scholar

30. An, J., Chang, N.-J., Song, L.-D., Jin, Y.-Q., Ma, Y., Chen, J.-R., Xiao, W.-J. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 1869–1871; https://doi.org/10.1039/c0cc03823g.Search in Google Scholar

31. Mahdavi, M., Hassanzadeh-Soureshjan, R., Saeedi, M., Ariafard, A., BabaAhmadi, R., Ranjbar, P. R., Shafiee, A. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 101353–101361; https://doi.org/10.1039/c5ra17056g.Search in Google Scholar

32. Golantsov, N. E., Karchava, A. V., Nosova, V. M., Yurovskaya, M. A. Russ. Chem. Bull., Int. Ed. 2005, 54, 226–230; https://doi.org/10.1007/s11172-005-0241-4.Search in Google Scholar

33. Festa, A. A., Zalte, R. R., Golantsov, N. E., Varlamov, A. V., Van der Eycken, E. V., Voskressensky, L. G. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 9305–9311; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.joc.8b01279.Search in Google Scholar

34. Palomba, M., Sancineto, L., Marini, F., Santi, C., Bagnoli, L. Tetrahedron 2018, 74, 7156–7163; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tet.2018.10.044.Search in Google Scholar

35. Hu, S.-B., Chen, Z.-P., Song, B., Wang, J., Zhou, Y.-G. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2017, 359, 2762–2767; https://doi.org/10.1002/adsc.201700431.Search in Google Scholar

36. Chu, X., Zhang, Z., Wang, C., Chen, X., Wang, B., Ma, C. Tetrahedron 2017, 73, 7185–7189; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tet.2017.10.066.Search in Google Scholar

37. Chizhova, M., Khoroshilova, O., Dar’in, D., Krasavin, M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2018, 59, 3612–3615; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tetlet.2018.08.049.Search in Google Scholar

38. Kumar, K. S., Kumar, N. P., Rajesham, B., Kishan, G., Akula, S., Kancha, R. K. New J. Chem. 2018, 42, 34–38.10.1039/C7NJ03608FSearch in Google Scholar

39. Srinivasulu, V., Shehadeh, I., Khanfar, M. A., Malik, O. G., Tarazi, H., Abu-Yousef, I. A., Sebastian, A., Baniowda, N., O’Connor, M. J., Al-Tel, T. H. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 84, 934–948; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.joc.8b02878.Search in Google Scholar

40. Ramesh, S., Ghosh, S. K., Nagarajan, R. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2013, 11, 7712–7720; https://doi.org/10.1039/c3ob41044g.Search in Google Scholar

41. Bi, H.-Y., Du, M., Pan, C.-X., Xiao, Y., Su, G.-F., Mo, D.-L. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 84, 9859–9868; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.joc.9b00784.Search in Google Scholar

42. Murugesh, V., Bruneau, C., Achard, M., Sahoo, A. R., Sharma, G. V. M., Suresh, S. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 10448–10451; https://doi.org/10.1039/c7cc05604d.Search in Google Scholar

43. Toche, R. B., Janrao, R. A. Arabian J. Chem. 2019, 12, 3406–3416; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2015.08.034.Search in Google Scholar

44. Youssif, B. G. M., Abdelrahman, M. H., Abdelazeem, A. H., Abdelgawad, M. A., Ibrahim, H. M., Salem, O. I. A., Mohamed, M. F. A., Treambleau, L., Bukhari, S. N. A. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 146, 260–273; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.01.042.Search in Google Scholar

45. Gujral, S. S. Master Dissertation, University of Waterloo: Waterloo, Ontario (Canada), 2017.Search in Google Scholar

46. Mizyed, S. A., Ashram, M., Awwadi, F. F. Arkivoc 2011, x, 277–286.10.3998/ark.5550190.0012.a22Search in Google Scholar

47. Ashram, M., Awwadi, F. F. Arkivoc 2019, v, 142–151; https://doi.org/10.24820/ark.5550190.p010.780.Search in Google Scholar

48. Ashram, M., Awwadi, F. F. Arkivoc 2019, vi, 239–251; https://doi.org/10.24820/ark.5550190.p011.061.Search in Google Scholar

49. Cheung, J., Rudolph, M. J., Burshteyn, F., Cassidy, M. S., Gary, E. N., Love, J., Franklin, M. C., Height, J. J. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 10282–10286; https://doi.org/10.1021/jm300871x.Search in Google Scholar

50. Rodríguez-Domínguez, J. C., Balbuzano-Deus, A., López-López, M. A., Kirsch, G. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2007, 44, 273–275; https://doi.org/10.1002/jhet.5570440146.Search in Google Scholar

51. Salahi, S., Ghandi, M., Abbasi, A. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2019, 56, 1296–1305; https://doi.org/10.1002/jhet.3499.Search in Google Scholar

52. Ellman, G. L., Courtney, K. D., Andres, V., Featherstone, R. M. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1961, 7, 88–95; https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-2952(61)90145-9.Search in Google Scholar

53. Aras, A., Dogru, M., Bursal, E. Anal. Chem. Lett. 2016, 6, 758–765; https://doi.org/10.1080/22297928.2016.1265467.Search in Google Scholar

54. Re, R., Pellegrini, N., Proteggente, A., Pannala, A., Yang, M., Rice-Evans, C. Free Radical Biol. Med. 1999, 26, 1231–1237; https://doi.org/10.1016/s0891-5849(98)00315-3.Search in Google Scholar

55. Al-Zereini, W. A. Jordan J. Biol. Sci. 2014, 7, 133–137; https://doi.org/10.12816/0008227.Search in Google Scholar

Supplementary Material

The online version of this article offers supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/znb-2020-0205).

© 2021 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Research Articles

- Coloring and distortion variants of the bcc packing and for the aristotypes BaAl4 and CeMg2Si2

- Coloring variants of the Re3B type

- CeTiO2N oxynitride perovskite: paramagnetic 14N MAS NMR without paramagnetic shifts

- Li9Yb2[PS4]5 and Li6Yb3[PS4]5: two lithium-containing ytterbium(III) thiophosphates(V) revisited

- Nitroimidazoles Part 9. Synthesis, molecular docking, and anticancer evaluations of piperazine-tagged imidazole derivatives

- A convenient one-pot approach to the synthesis of novel pyrazino[1,2-a]indoles fused to heterocyclic systems and evaluation of their biological activity as acetylcholinesterase inhibitors

- A 2-D Zn(II) coordination polymer based on 4,5-imidazoledicarboxylate and bis(benzimidazole) ligands: synthesis, crystal structure and fluorescence properties

- Synthesis and crystal structures of Zn(II) and Cd(II) coordination polymers derived from the flexible N-(4-carboxyphenyl)iminodiacetic acid and auxiliary ligands

- Synthesis, structural characterization, and properties of three Ag(I) complexes with oxazoline-containing chiral ligands

- Book Review

- P. M. H. Kroneck and M. E. Sosa Torres (Guest Editors): Metals, Microbes and Minerals: The Biogeochemical Side of Life

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Research Articles

- Coloring and distortion variants of the bcc packing and for the aristotypes BaAl4 and CeMg2Si2

- Coloring variants of the Re3B type

- CeTiO2N oxynitride perovskite: paramagnetic 14N MAS NMR without paramagnetic shifts

- Li9Yb2[PS4]5 and Li6Yb3[PS4]5: two lithium-containing ytterbium(III) thiophosphates(V) revisited

- Nitroimidazoles Part 9. Synthesis, molecular docking, and anticancer evaluations of piperazine-tagged imidazole derivatives

- A convenient one-pot approach to the synthesis of novel pyrazino[1,2-a]indoles fused to heterocyclic systems and evaluation of their biological activity as acetylcholinesterase inhibitors

- A 2-D Zn(II) coordination polymer based on 4,5-imidazoledicarboxylate and bis(benzimidazole) ligands: synthesis, crystal structure and fluorescence properties

- Synthesis and crystal structures of Zn(II) and Cd(II) coordination polymers derived from the flexible N-(4-carboxyphenyl)iminodiacetic acid and auxiliary ligands

- Synthesis, structural characterization, and properties of three Ag(I) complexes with oxazoline-containing chiral ligands

- Book Review

- P. M. H. Kroneck and M. E. Sosa Torres (Guest Editors): Metals, Microbes and Minerals: The Biogeochemical Side of Life