Abstract

In this paper we investigate how verum is realized in Xhosa and Zulu, two Southern Bantu languages belonging to the Nguni group. The data for our study were collected through interviews with native speakers who were prompted to produce sentences in discourse contexts that typically license utterances with verum. We found that the main grammatical strategy for the expression of verum in Xhosa and Zulu involves the removal of phrasal constituents from the focus domain (the VP). This leaves the verb as the sole remaining focus host, and allows auxiliary features of the verb, such as polarity, to be marked as focus. Consequently, we analyse verum in Xhosa and Zulu as polarity focus, which is expressed indirectly, via the backgrounding of potentially focusable phrasal material. We also examined the prosodic properties of verum utterances in Xhosa. Based on findings from previous studies on Nguni intonation, we expected to observe lengthening of the penultimate vowels of phrase-final verbs and utterance-final words in our data. However, contrary to expectation, we did not find evidence of penultimate vowel lengthening in Xhosa sentences with verum, a (preliminary) result which suggests that the expression of verum may have an effect on prosody in Nguni languages.

1 Introduction

The English sentence in (1), which includes the stressed auxiliary do, is a typical example of a sentence with verum focus:

| John did clean his room. |

There are at least three related characteristics of sentences with verum focus that any theory has to account for. First, with the use of a sentence with verum focus, the speaker emphasizes the truth of the proposition that is asserted (hence the term verum). Second, verum focus is typically used in contexts in which this proposition is somehow at issue, or controversial. For example, (1) could be uttered in response to some speaker explicitly denying that John cleaned his room, or when there is some doubt as to whether John really cleaned his room etc. And third, the propositional content of a sentence with verum focus is all-given. This is why sentences such as (1) are judged as infelicitous when uttered out of the blue.

As the term verum focus suggests, the phenomenon illustrated by sentences such as (1) has traditionally been analysed in terms of focus: either focus on a truth predicate (e.g. Höhle 1992), on positive polarity (e.g. Goodhue 2018, 2022; Samko 2016; Servidio 2015; Wilder 2013), or on sentence mood (Kocher 2023; Lohnstein 2012, 2016). However, other research (e.g. Gutzmann et al. 2020; Romero and Han 2004) argues that verum “focus” is not a kind of focus at all. Instead, these alternative accounts suggest that the interpretation of sentences such as (1) is brought about by a lexical conversational operator (labelled verum in Gutzmann et al. 2020), which in a language such as English or German happens to be realized by the same intonational means as focus, namely by pitch accent. One of the key arguments in Gutzmann et al. (2020) for this Lexical Operator Thesis (LOT) is that in some languages in which focus is not marked by intonation, the strategy for expressing verum (focus) differs from the strategies used to mark (other types of) focus.

In our discussion, we will henceforth use the neutral term verum (lowercase) instead of verum (small-caps), verum focus or polarity focus and remain agnostic (at least initially) about whether it is a focus phenomenon (we will later conclude that it is). Our aim is to contribute to the debate about the status of verum by exploring how it is realized in Xhosa (S41)[1] and Zulu (S42), two closely related and mutually intelligible varieties belonging to the Nguni group of Bantu languages (Niger-Congo), which also includes Swati (S43) and Ndebele (S44). Xhosa and Zulu are the most frequently spoken languages in South African households, with 22.7 and 16 percent of the population respectively reporting them as their first language (Statistics South Africa 2012). Similarly to the languages mentioned in Gutzmann et al. (2020), focus is typically not marked directly through prosodic prominence in Bantu languages (Downing and Hyman 2016). However, vowel length and/or tone have been found to correlate with phonological and syntactic phrasing, which in turn corresponds with information structure. It is therefore an important empirical question which strategies Xhosa and Zulu speakers adopt to express the meanings associated with constructions such as (1), and if, or how, these strategies relate to focus-marking strategies in the language. While the expression of verum in Xhosa and Zulu has been mentioned in studies of other aspects of the grammar of Nguni languages, the phenomenon has never received systematic attention (to the best of our knowledge). The present study addresses this lacuna by contributing a first in-depth account of verum in Xhosa and Zulu, in the different contexts in which verum is expected, based on first-hand data. Furthermore, we provide the first investigation of possible intonational reflexes of verum in these languages, by offering an analysis of the prosody of our Xhosa data.

Our study demonstrates that verum-readings in Xhosa and Zulu are expressed consistently through the removal of all non-focal phrasal material from the focus domain. Following Güldemann (2016), we interpret this process of maximal backgrounding as an indirect focus marking strategy, and consequently argue that the Xhosa and Zulu data support an analysis of verum as polarity focus. The backgrounding of phrasal material leaves the verb as the final element in its phrase and marks it as a potential focus host. Focus can then fall on the verbal predicate, or on auxiliary features (Hyman and Watters 1984), such as tense, aspect, or polarity. An unexpected additional finding of our study is that Xhosa and Zulu sentences with verum show no evidence of penultimate vowel lengthening, a prosodic feature which is otherwise expected both in phrase-final verbs and at the end of declarative utterances in Nguni languages.

The article is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the basic building blocks of a focus account of verum, labelled the Focus Accent Thesis (FAT) by Gutzmann et al. (2020), as well as its alternative, the Lexical Operator Thesis (LOT). Section 3 provides an illustration of two verum marking strategies, attested in some Bantu languages, that are particularly relevant for our study, namely the use of the so-called “disjoint” verb form, and doubling object marking. Section 4 presents the results of our study of verum in Xhosa and Zulu. In Section 5, we address the prosodic properties of Xhosa sentences that are used in verum contexts, and we provide a discussion of our results in Section 6. Section 7 concludes.

2 The FAT and the LOT: two approaches to verum

As noted above, a common approach to verum is to treat it as a genuine focus phenomenon. One prominent focus account assumes that in constructions with verum, the (positive)[2] polarity of the sentence is focused, and the semantic, pragmatic and prosodic characteristics of verum are derived from this assumption. Many authors (e.g. Goodhue 2018, 2022; Samko 2016; Servidio 2015; Zimmermann and Hole 2008) implement this idea in terms of Rooth’s theory of alternative semantics (Rooth 1985, 1992). According to this theory, every expression φ has, in addition to its ordinary denotation, a focus semantic value. The focus semantic value of φ is a set of alternatives, where each alternative in the set is derived by replacing the denotation of a focused constituent in φ with an element of the same semantic type. For example, in a sentence with subject focus, such as john likes Mary, the focus semantic value of the focused subject John is a set of individuals (e.g. {Brian, Anna, John …}), and the focus sematic value of the sentence is the set of alternative propositions that are derived by replacing the denotation of the focused subject with one of these alternatives, e.g. {‘Brian likes Mary’, ‘Anna likes Mary’, ‘John likes Mary’ …}. The sentence john likes Mary is felicitous in a context in which at least one of the propositions from the set of alternatives that is distinct from the actual asserted proposition is available as a focus antecedent (or focal target).

A sentence with polarity focus can be analysed along the same lines. When the polarity of the sentence is focused, it follows that its propositional content is given. Sentence polarity only has two plausible alternatives in natural language, affirmation and negation, represented in (2)a) and (2)b). Consequently, the focus semantic value of polarity is the set that includes these two alternatives. It then follows that the focus alternative set of a sentence with polarity focus is always the set which includes exactly two propositions, namely p and its negative counterpart ¬p, (3) (Goodhue 2018, 2022; Wilder 2013; Zimmermann and Hole 2008):

| affirmation: λp<s,t>.p | (maps a proposition onto itself) |

| negation: λp<s,t>.¬p | (maps a proposition onto its negative counterpart) |

| Focus alternative set of S with propositional content p and polarity focus: {p, ¬p} |

Because the focal target of a sentence must be distinct from its propositional content, it follows from (3) that the focus antecedent of a sentence with polarity focus is always the proposition with the opposite polarity to what has been asserted. This explains the observation that polarity focus is felicitous in contexts in which the proposition expressed by the sentence is somehow in doubt or contentious:

| I don’t think John cleaned his room. |

| John did clean his room! |

Polarity focus in (4)B) makes {‘John cleaned his room’, ‘John did not clean his room’} the set of focus alternatives. The only member of this set which is distinct from the proposition denoted by (4)B) is the proposition that John didn’t clean his room. Since this alternative proposition is made salient by A’s utterance, (4)B) is acceptable in this context.

As argued in Goodhue (2018, 2022, a polarity focus account also explains the pragmatic effects of verum: “Using focus to signal that your assertion of p contrasts with the focal target ¬p while also entailing that it is false produces the intuition that the truth of p is emphasized” (Goodhue 2022: 146). According to this view, the emphasis on the truth of the proposition expressed by a sentence with verum follows directly from drawing attention to a focus alternative with contrasting polarity.

Finally, a focus theory of verum also explains that in languages such as English and German, verum is marked by a prosodic prominence shift to the finite verb or auxiliary. Since focus in these languages is generally marked by pitch accent, the accent which marks verum can be treated as a genuine focus accent.

The approach to verum that treats it as a focus phenomenon has been labelled the Focus Accent Thesis (FAT) by Gutzmann et al. (2020).[3] Gutzmann et al. (2020) contrast the FAT with an alternative analysis which they name the Lexical Operator Thesis (LOT). According to the LOT, verum is not a focus construction. Rather, the meaning of verum is associated directly with a use-conditional conversational operator verum which only appears in sentences with verum. In languages such as German or English, the lexical realization of this operator is accent (lexicalized intonational meaning), but in other languages, the verum operator may be realized by affixes or particles (Gutzmann et al. 2020; Matthewson and Glougie 2018; compare e.g. the Bura example in (6)b) below). Different versions of the LOT are adopted, for example, by Romero and Han (2004), Gutzmann and Miró (2011), Gutzmann et al. (2020), and Bill and Koev (2021).

One possible advantage of the LOT over the FAT is that the semantics of verum is not restricted by the conditions on focus assignment and interpretation. Rather, the LOT allows its proponents to associate any conceivable version of a verum interpretation directly with the lexical operator. For example, Gutzmann et al. (2020: 39), following Gutzmann and Miró (2011), postulate the following semantics for verum:

| ⟦verum⟧u,c(p) = √, if the speaker cS wants to prevent that QUD(c) is downdated with ¬p. |

According to (5), the semantics of the verum operator is use-conditional: using verum in a sentence which expresses the proposition p is felicitous if it is the speaker’s intention to prevent that the question under discussion (QUD) in the context is settled with ¬p. In other words, the speaker asserts p, but at the same time signals that they do not want ¬p to be considered as a resolution to an open (potentially implicit) question. According to Gutzmann et al. (2020), this entails that the possibility of ¬p has been mentioned or made salient in the discourse. It therefore explains that verum is used in contexts in which the proposition p expressed by a sentence is in doubt or controversial.

Gutzmann et al. (2020) provide a number of arguments against the FAT and in favour of the LOT. One of their strongest arguments is cross-linguistic. The authors point out that the FAT is motivated mainly by languages in which both verum and focus are marked via accent and discuss several languages in which focus is not prosodically marked. Crucially, in these languages, the strategies to mark verum are different from the strategies used to mark other types of focus. For instance, in the Chadic language Bura, object focus is marked by a cleft construction and the focus marker an, (6)a). Verum, on the other hand, is optionally marked in Bura by means of a different marker kú, which puts emphasis on the truth value, (6)b):

| Bura[4] |

| Kilfa | an | tí | Kubílí | másta | akwa | kwasúku | |

| fish | foc | rel | Kubili | buy | at | market | |

| ‘It’s fish that Kubili bought at the market.’ |

| a’á, | Pindár ( kú ) | sá | mbal | náha |

| yes | Pindar (verum) | drink | beer | yesterday |

| ‘Yes, Pindar did drink beer yesterday.’ | ||||

| (Gutzmann et al. 2020: 19–20) |

As mentioned in the introduction, Nguni and other Bantu languages generally do not make use of prosodic prominence to directly mark focus. It is therefore of importance to examine whether the strategies to mark verum are different from other focus strategies in these languages, to bring further cross-linguistic evidence to the theoretical debate on verum.

3 Verum strategies in Bantu: disjoint verb forms and object marking

Kerr and van der Wal (2023) distinguish a variety of lexical and grammatical strategies utilized to mark verum in different Bantu languages. In this section, we discuss two of these strategies that are relevant for our exploration of verum in Xhosa and Zulu, namely the use of the disjoint verb form, and doubling object marking. (The reader is referred to Kerr and van der Wal (2023) for an overview and discussion of other verum marking strategies in Bantu.)

The conjoint–disjoint (CJ-DJ) alternation (Van der Wal and Hyman 2017) is an alternation in certain TAMs between two forms of the verb that are distinguished by segmental morphology and/or tone. The two verb forms are identical in their TAM semantics but impose different requirements on the structure. The conjoint form can never appear sentence-finally (7)b), and material directly following the conjoint form is typically focused, or part of the focus (7)a). The disjoint form can appear sentence-finally (7)c), but it can also be followed by other constituents (7)d). The following examples illustrate this for Makhuwa:

| Makhuwa |

| ki-n-lówá | ehopá |

| sm1sg-pres.cj-fish | 9.fish |

| ‘I catch fish.’ |

| *ki-n-lówa |

| ki-náá-lówa | |

| sm1sg-pres.dj-fish | |

| ‘I’m fishing.’ |

| ki-náá-lówá | ehópa |

| sm1sg-pres.dj-fish | 9.fish |

| ‘I catch fish.’ | |

| (Van der Wal 2011: 1738) |

When a verb in the disjoint form is not in sentence-final position, the postverbal material is structurally outside the VP, and semantically out-of-focus. Consequently, a sentence with the disjoint verb form can express predication focus (Güldemann 2003): the focus can fall on the verb, or on any of the inflectional categories associated with verbs, such as tense, aspect, mood, or verum/polarity (called auxiliary focus in Hyman and Watters 1984). Kerr and van der Wal (2022, 2023 note this to be the case in Makhuwa:

| Makhuwa | |

| o-h-aápéya | (ekútte) |

| sm1-pfv.dj-cook | 10.green.beans |

| ‘He did cook beans.’ (Paulo didn’t cook beans.) |

| ‘He cooked beans.’ (‘Did he buy beans?’) |

| (Kerr and van der Wal 2022) |

As the translations show, the disjoint form in (8) can express verum (8)a), but also contrastive verb focus (8)b). While it is not the case that the use of the disjoint form necessarily encodes predication focus in Makhuwa, the disjoint form is needed if predication focus is to be expressed (cf. van der Wal 2017: 44).

The disjoint form has also been linked to the expression of verum in the Nguni languages (see Adams 2010; Doke 1997 [1927]; Güldemann 2003; Halpert 2012; Jokweni 1995; Voeltz 2004). In Nguni, the disjoint form is segmentally marked in the present tense by the prefix ya- and in the recent past tenses by the suffix -ile. The conjoint form is unmarked in the present and takes the (high-toned) suffix -e in the recent past tenses. The (b)-examples below illustrate the use of the disjoint form as a strategy to express verum-readings, which are indicated in the English translations by the use of the auxiliary do:

| Zulu |

| ngi-dla | isinkwa |

| sm1sg-eat.cj | 7.bread |

| ‘I’m eating bread.’ |

| ngi- ya -si-dla | isinkwa |

| sm1sg-dj-om7-eat | 7.bread |

| ‘I do eat bread.’ | |

| (Doke 1997 [1927]: § 809) |

| Zulu |

| si-dlala | ekuseni |

| sm1pl-play.cj | in.the.morning |

| ‘We play in the morning (not at other times).’ |

| si- ya -dlala | ekuseni |

| sm1pl-pres.dj-play | in.the.morning |

| ‘We do play in the morning.’ | |

| (Voeltz 2004: 9) |

| Xhosa |

| ndi-thetha | ku-ye | |

| sm1sg-speak.cj | to-pro1 | |

| ‘I am speaking to him.’ |

| ndi- ya -thetha | ku-ye |

| sm1sg-dj-speak | to-pro3 |

| ‘I am speaking/do speak to him.’ | |

| (Güldemann 2003: 337, citing McLaren 1955: 82–83) |

Note that in the Zulu example in (9), in addition to the disjoint marker, an object marker is prefixed to the verb, which “doubles” the postverbal object, and agrees with it in noun class. The occurrence of the object marker in a sentence with verum is interesting in light of another verum-marking strategy, which has been observed in Bantu languages such as Lubukusu, Cinyungwe (Lippard et al. Forthcoming; Sikuku et al. 2018; Sikuku and Diercks Forthcoming) and Rukiga (Kerr and van der Wal 2023). In these languages, an object marker prefixed to the verb stem does not tolerate the corresponding full object-NP to appear VP-internally in pragmatically neutral contexts. When the object marker co-occurs with the object, the object is typically extraposed, as signalled by compulsory comma intonation in (12):

| Lubukusu | ||

| n-á-ki-βona | *(,) | éembwa |

| sm1sg-rem.pst-om9-see | 9.dog | |

| ‘I saw it, the dog.’ | ||

| (Sikuku et al. 2018: 368) |

However, the object marker can be used to double a VP-internal object when the sentence receives a verum interpretation:

| Lubukusu | |

| n-aá-βu-l-iilé | βúusuma |

| sm1sg-pst-om14-eat-pfv | 14.ugali |

| ‘I did eat ugali.’ | |

| (Sikuku et al. 2018: 360) |

In the following sections we present and discuss the results of our study, in which we investigated the grammatical properties of sentences produced by Xhosa and Zulu speakers in contexts designed to elicit verum responses. Our aim was to explore whether speakers use the disjoint verb form and the object marker systematically to express verum readings, and whether (or to what extent) they also resort to other verum-marking strategies – in particular with verbs whose TAM does not license the CJ-DJ alternation, or in sentences with no, or more than one, object. In Section 5, we therefore also examine the prosody of verum sentences, in order to establish whether suprasegmental features play a role in the expression of verum in Xhosa and Zulu.[5]

4 Verum in Xhosa and Zulu

This section outlines the results of our study, which was conducted in the form of interviews with 9 Xhosa speakers (6 female and 3 male) and 11 Zulu speakers (7 female and 4 male), aged 20–55. Interviews took place at the homes of interviewees or at the university, in quiet settings. The Xhosa interviews were conducted in Makhanda (Eastern Cape province), and the Zulu interviews in the Clermont township near Durban (KwaZulu-Natal province), in South Africa. The interviews took the form of guided elicitation where respondents were expected to fill in an appropriate answer. We introduced a short context to the situation imagined, followed by a sentence to which the participants were asked to respond. These sentences were based on verum tests discussed in Gutzmann et al. (2020) and Matthewson and Glougie (2018) and presented contexts in which the expression of verum is infelicitous, expected, or optional. In total, we included 42 contexts/sentences. Our database of sample sentences representing speakers’ responses consists of ca. 730 sentences (not every speaker provided a response for every context). The contexts were initially constructed in English and then translated by bilingual research assistants into Xhosa and Zulu. The same research assistants also conducted the interviews monolingually in Xhosa and Zulu and transcribed the data they collected. A few of the interviews were also conducted in English, by the authors.

In what follows, we first present examples from Xhosa and Zulu in contexts in which verum marking is infelicitous. With this as a background, we examine the difference between those and contexts in which verum marking is expected, followed by contexts in which verum marking is optional.

4.1 Verum infelicitous

As noted above, in a sentence with verum, the whole proposition is given. Therefore, the expression of verum is not expected in out-of-the-blue statements or discourse-initially, where there either is no question under discussion, or a very broad one such as ‘What happened?’ (Gutzmann et al. 2020: 10). In the Nguni languages, this kind of broad question can be answered with a sentence in the canonical SVO order (14)a–b), or through a subject inversion construction with expletive agreement (14)c):

| Context: you are in a room, and just before Sipho comes in, the cat happens to push down a glass. The glass lies broken on the floor. Sipho says: kwenzeke ntoni? ‘what happened?’ |

| ikati y-am | y-ophul-e | iglas |

| 9.cat 9-poss1sg | sm9-break.tr-rec.cj | 9.glass |

| ‘My cat broke the glass.’ | [XHOSA_04_F_25/A1][6] |

| ikati | li-wis-e | inkomishi |

| 5.cat sm5-fall.caus-rec.cj | 9.cup | |

| ‘The cat broke the cup.’ | [ZULU_04_M_34/A1] |

| k-ophuk-e | iglasi | ngoba | be-ku-kho | umoya | |

| sm17-break.intr-rec.cj | 9.glass | because | rec-17.be.present | 11.wind | |

| ‘A glass broke because there was wind.’ [XHOSA_01_F_48/A1] |

Recall from Section 3 that Xhosa and Zulu exhibit a distinction between two morphologically different forms in the present and the recent past, the CJ-DJ alternation. As (14)a–b) illustrate, we found that speakers consistently used the conjoint form of the recent past in the SVO-answers to a broad ‘What happened’-question, while the disjoint form was never attested. The construction in (14)c) with expletive agreement and subject inversion is often referred to as ‘default agreement inversion’ in Bantu studies and is typically used to introduce new referents and situations (Carstens and Mletshe 2015; Marten and van der Wal 2014). Default agreement inversion always requires the conjoint form of the verb. Therefore, the responses show that the conjoint form is the canonical verb form in transitive all-new or thetic sentences with broad focus in Xhosa and Zulu.

A second context in which verum has been claimed to be disallowed, or at least marked (see e.g. Gutzmann et al. 2020), is in the neutral answer to an unbiased polar question. However, Goodhue (2018) considers verum in these contexts optional. We will therefore discuss the constructions used in this context in Section 4.3 below.

4.2 Verum expected

We now turn to speakers’ responses in contexts that allow, or even prompt verum. Recall from Section 2 that verum(p) is licensed when there is some controversy around p, such as when the speaker is correcting a previous utterance (see (4) above). This is exemplified with the following context that was presented to our respondents:

| Context: someone tells you that you did or did not do a certain thing, but it’s not true. Speaker: You didn’t clean the house yesterday. – You: Contradict the person. |

| ndi-yi-coc-ile | indlu | izolo |

| sm1sg-om9-clean-rec.dj | 9.house | yesterday |

| ‘I did clean the house.’ | [XHOSA_01_F_48/D22] |

| hhayi | ma | ngi- yi -hlanz- ile | indlu |

| no | mother | sm1sg-om9-clean-rec.dj | 9.house |

| ‘No mother, I did clean the house.’ | [ZULU_10_M_24/D22] |

The examples in (15) illustrate two crucial morpho-syntactic properties of constructions that appear in verum-licensing contexts in Nguni. First, in contrast to the examples in (14) in which verum is infelicitous and where the conjoint verb form was used, the disjoint form of the recent past appears in (15). This is a consistent finding across all our respondents, for both languages: Whenever the TAM of the respective sentence allows a distinction between a conjoint and a disjoint form, the disjoint form is used in contexts such as (15) in which the truth of the sentence is under dispute. As was noted above in Section 3, the fact that the disjoint form in Nguni can give rise to a verum interpretation has been noted before in the literature on Xhosa and Zulu. Our results confirm this observation.

Second, as illustrated by (15), when the relevant sentences are based on monotransitive verbs with a single object, the corresponding object marker appears on the verb. This result is interesting in light of the studies, mentioned in Section 3, that find that object doubling is used in some Bantu languages as a device to express verum (Lippard et al. Forthcoming; Sikuku et al. 2018), see examples (12)–(13). However, some caution needs to be exercised before an analogous conclusion can be drawn for Nguni, since in Nguni the relation between object marking and verum is indirect. As has been noted frequently in the literature (see Adams 2010; Buell 2005; Cheng and Downing 2009; van der Spuy 1993; Voeltz 2004; Zeller 2015 for Zulu; Andrason and Visser 2016; Carstens and Mletshe 2016 for Xhosa), object marking in Xhosa and Zulu correlates with object dislocation: when the sole object of a monotransitive verb is dislocated, the object marker is obligatory, while a VP-internal object can never be object-marked. Now recall that the use of the disjoint verb form in Xhosa and Zulu entails that postverbal material is VP-external. An object that follows the disjoint verb form is therefore not in its VP-internal argument position but has been right-dislocated. Consequently, the object marker must occur in the relevant examples. This means that both the disjoint form and the object marker in examples such as (15) are morphological reflexes of the fact that the postverbal object-DP is in a VP-external position. We return to this point in Section 6, where we suggest that object dislocation is a means to remove the object from the focus domain of the clause, which is a necessary condition for the expression of verum in Xhosa and Zulu.

The requirement to object-mark an object in a context that licenses verum also extends to sentences whose TAM does not show a distinction between the conjoint and the disjoint verb form, such as the future tense:

| Context: someone tells you that you will or will not do a certain thing, but you strongly disagree. Speaker: You will never get your driver’s license… – You: Contradict the person. |

| hhayi, | ngi-zo- zi -thola | izincwadi | zo-ku-shayela |

| no | sm1sg-fut-om10-take 10.papers | 10as-15-drive | |

| ‘No, I will get my driving licence.’ [ZULU_03_F_38/E29] |

Verbs in the future tense in Nguni do not exhibit the CJ-DJ alternation. However, if there is an object in the sentence, it must be object-marked in the verum-licensing context above, just as in the examples in (15). Again, this is a consequence of the fact that the object in (16) is dislocated to a VP-external position. In monotransitive sentences based on TAM specifications that do not show the CJ-DJ alternation, the removal of the object from the VP is still signalled by object marking.

We also asked speakers to respond to a context such as (17), to prompt them to form sentences with an intransitive verb and a locative argument. Locative arguments cannot be object-marked in Nguni:

| Context: someone tells you that you did or did not do a certain thing, but it’s not true. Speaker: You did not come to my party. – You: Contradict the person. |

| ngi-z- ile | ephathini | ya-kho |

| sm1sg-go-rec.dj | loc.9.party | poss9-2sg |

| ‘I did come to your party!’ [ZULU_05_F_31/D25] |

The only past tense form that shows the CJ-DJ alternation in Nguni is the recent past. As expected, speakers who responded to the context in (17) in the recent past used the disjoint form of the verb (as shown in (17)). As explained above, the use of the disjoint form signals that the postverbal locative is in a VP-external position.

Next, consider (18). This sentence is in the future tense, which does not license the CJ-DJ alternation, and the verb does not take an object that can be object-marked. Consequently, the response in (18)a) does not include any special morphological marking that would indicate a verum reading:[7]

| Context: your mother tells you that you will not be allowed to go to a party, but you contradict her. Speaker: You will not go to the party! – You: Disagree with your mother. |

| cha | mama ngi-zo-ya | ephathini |

| no | mama sm1sg-fut-go | loc.9.party |

| ‘No mother I will go to the party.’ | [ZULU-09-F-24/D23] |

Based on the discussion above, it is reasonable to assume that the locative in (18) is VP-external, but in contrast to our earlier examples, this is not signalled by the verbal morphology. Note however that a sentence such as (18) may provide prosodic cues regarding the position of the postverbal constituent. We discuss the prosodic properties of sentences with verum in Section 5.

Apart from morphological markers, speakers also used various lexical means to signal the contradiction of a previous statement. In example (15)b) and (16), the emphatic negative interjection hhayi ‘no’ is used by the speaker. In (18), the negative interjection is cha. Negative interjections were used as a common additional strategy in many cases (for example, 10 out of 17 respondents used it in the specific context described in (15), and 7 out of 17 in (16)). However, as the examples in (15)a) and (17) illustrate, these lexical markers are not obligatory.

Another context in which verum is typically expected is in the response to an alternative question (“p or not p?”):

| Was Katie looking good yesterday or was she not looking good? |

| She was looking good |

| (Gutzmann et al. 2020: 12) |

Not surprisingly, our respondents here adopted the same strategies as in the examples above, i.e. object marking and the disjoint form of the verb:

| Context: someone asks you a question. Answer the questions positively, and then negatively. Speaker: ‘Did Thoko pass his exam or did he not pass his exam?’ |

| yebo uThoko | u-zi-phas-ile | izivivinyo | za-khe |

| yes | Thoko | sm1-om10-pass-rec.dj 10.exams | poss10-3sg |

| ‘Yes Thoko did pass his exams.’ | [ZULU_02_M_32/F_32_1] |

| cha uThoko | a-ka- zi -phas-anga | izivivinyo | za-khe |

| no Thoko | neg-sm.neg1-om10-pass-neg.rec | 10.exams | poss10-3sg |

| ‘No Thoko did not pass his exams.’ | [ZULU_02_M_32/F_32_2] |

In (20)a), the object DP is object-marked, and hence dislocated, and the recent past tense consequently is realized in the disjoint form. The CJ-DJ alternation is not marked in negated sentences in Nguni; therefore, in the negative response in (20)b), object dislocation is only reflected by object marking.

4.3 Verum optional

In this section we discuss contexts which allow, but do not require, a response with verum. When a speaker emphatically confirms an affirmative or negative assertion, verum is possible, as in the English dialogue below (Gutzmann et al. 2020; Wilder 2013):

| Sue looked nice yesterday. |

| Yes, she did look nice. |

| Yes, she looked nice. |

B can use verum when affirming A’s previous statement but does not have to. The response with verum suggests that B considers it possible that there is some doubt regarding A’s statement that Sue looked nice, and by using verum, contrasts the truth of this statement with its (implicit) negative counterpart.[8]

In our results for these contexts, speakers use a variety of lexical expressions to express agreement with the previous statement (compare ngempela ‘indeed’ in (22)a). When a TAM is used in which the CJ-DJ alternation is expressed, the disjoint form is again used:

| Context: someone makes a statement and you really agree. Speaker: He is a hard-working student. – You: Agree emphatically with the person. |

| ya | yena | umshana | wa-mi | u-ya-zi-misela | ngempela |

| yes | 3sg | 1.nephew | poss1-1sg | sm1-pres.dj-refl-determine | indeed |

| ‘Yes, he is, my nephew is determined indeed.’ | [ZULU_07_M_19/D18] |

| ewe | u- ya -zi-nikezela | emsebenzini | wa-khe |

| yes | sm1-pres.dj-refl-submit | loc.3.work | poss3-3sg |

| ‘Yes, he does submit himself to his work.’ | [XHOSA_ 01_F_48/D18] |

Another context in which verum is optional is in response to a polar question. When answering a neutral yes-no question such as (23)A), the use of verum(p) is often considered “weird” (Gutzmann et al. 2020: 7, but see Goodhue 2018: 12 for the opposing view that verum is “perfectly normal” in such a context). However, when p is somehow in doubt or controversial, as in the context of a biased question such as (24)A), verum is acceptable:

| Did Chris submit her paper yesterday? |

| Yes, she submitted her paper. |

| #Yes, she did submit her paper. |

| Did Chris really submit her paper yesterday? |

| Yes, she did submit her paper. |

| (Gutzmann et al. 2020: 12) |

To establish to what extent the response strategy here depends on the context, we first provided speakers with a neutral, unbiased question, and later asked them to answer the same question, but with the added contextual information that the proposition p is in doubt. Interestingly, there was no significant difference between our speakers’ answers to these questions. In both types of answers, the disjoint verb form was used when permitted by the TAM, and an object marker appeared when the verb selected one or more objects:[9]

| Context: answer the question as if it’s true what the previous speaker says (whether the event did happen, or did not happen). Speaker: a) ‘Did Nwabisa give the children money’? b) ‘Are the children playing outside?’ c) ‘Will Andiswa not start the new job soon?’ |

| yebo, | uNwabisa | u-zi-ph-ile | izingane | imali |

| yes | 1a.Nwabisa | sm1-om10-give-rec.dj | 10.child | 9.money |

| ‘Yes, Nwabisa gave/did give the children money.’ | [ZULU_06_F_23/C12_1] |

| yebo, izingane | zi- ya -dlala | emnyango | |

| yes | 10.child | sm10-dj-play | loc.3.door |

| ‘Yes, the children are/are playing outside.’ | [ZULU_08_F_26/C12_2] |

| hayi uAndiswa a-ka-zo- wu -qala | umsebenzi | omtsha | ||||

| no | Andiswa | neg-sm.neg1-fut-om3-start | 3.work | 3.new | ||

| ‘No, Andiswa will not/not start the new job.’ | [XHOSA_02_F_28/C11] | |||||

| Context: as in (25), but with doubt that it has really happened. Speaker: (a) ‘Did Nwabisa really give the children money’? (b) ‘Are the children really playing outside?’ (c) ‘Did Hlumi really clean the dishes?’ |

| yebo, | uNwabisa | u-zi-ph-ile | izingane | imali |

| yes | Nwabisa | sm1-om10-give-rec.dj | 10.children | 9.money |

| ‘Yes, Nwabisa did give the children money.’ | [ZULU_06_F_23/C17_1] |

| ya, | izingane | zi- ya -dlala | emnyango |

| yes | 10.child | sm10-dj-play | loc.3.door |

| ‘Yes, the children are playing outside.’ | [ZULU_08_F_26/C17_2] |

| ewe uHlumi | u- zi -hlambh- ile | izitya |

| yes Hlumi | sm1-om10-wash-rec.dj | 10.dishes |

| ‘Yes Hlumi did wash the dishes.’ [XHOSA_03_F_25/C16] |

The responses shown in (25) and (26) mirror the strategies that were used in contexts in which verum is expected, such as the denial of a previous statement. While this was expected in the context in (26), where there was some doubt about the proposition, the use of the same strategy in a response to a simple yes-no question warrants some discussion. Before we offer this discussion in Section 6, we take a closer look at the prosody of the answers with verum.

5 Verum in the prosody?

We now turn to the question whether there is any marking of verum in the prosody of the Nguni languages. The interaction between focus and prosody has received ample attention in the research on Bantu languages. However, no direct relationship between semantic focus and prominence in pitch has been attested (Hyman 1999; Nurse 2008). Rather, in many Bantu languages, there is a relationship between phonological phrasing (as evidenced by vowel length and/or tone) and focus (Downing and Hyman 2016; Kanerva 1990).

In Luganda, for example, a plateau of high tones is the result when a verb with a high-low tone pattern is followed by a focused argument:

| Luganda | |||||

| y-a-lábà | + | bi-kópò | > | y-a-lábá bí-kópò | |

| sm1-pst-see | 8-cup | ||||

| ‘He saw cups.’ | |||||

| (Downing and Hyman 2016: 803) |

An indirect relationship between vowel length and focus has been shown to exist in Zulu (Cheng and Downing 2009, 2012) as well as in Xhosa (Jokweni 1995), as illustrated by example (29) below. In yet other Bantu languages, no relationship between prosody and focus can be found at all (Downing 2012; Zerbian 2006, 2007).

Since tone and vowel length can play a role in the expression of focus in Bantu languages, albeit indirectly, we need to test for their possible effects in the specific case of verum. We should also not rule out any direct marking of verum through pitch increase, although this is not expected based on the previous research mentioned above. To investigate these potential prosodic effects, we made use of visual inspection of pitch tracks, spectrograms and waveforms with the software Praat (Boersma and Weenink 2023) and measured penultimate vowel length for a selection of our Xhosa data. The recordings were made with a Zoom H4n recorder, making use of the internal microphone.[10]

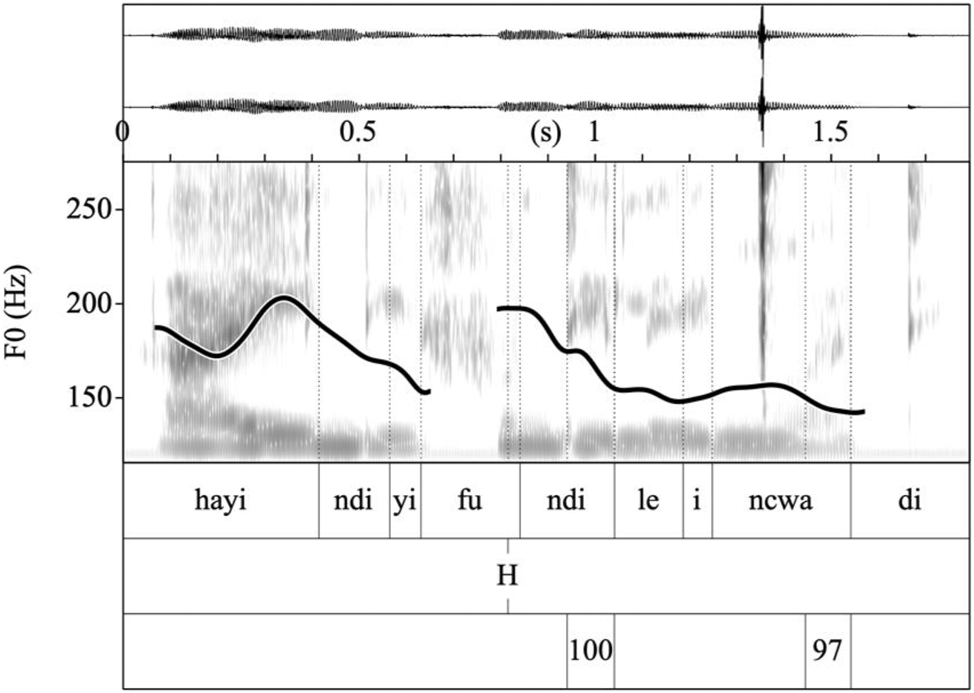

We start by considering pitch. In the results of our survey, an utterance-initial rise in pitch can optionally accompany a sentence with verum. This is exemplified in (28)a). The tonal pattern of this sentence is not altered. Subject markers of the first and second person are toneless in Xhosa, but the object marker (underlined) contributes a high tone. Since -fundile is low toned (Tshabe and Shoba 2006) and trisyllabic, the high tone of the object marker surfaces on the antepenultimate syllable, in accordance with systematic tone rules of the language (see Bloom Ström 2022 for a summary of these rules and also for intonation of sentence types in Xhosa). The high tones of the object argument ‘book’ are affected by declination and possibly final lowering and are therefore lowered. Together with the devoicing of the final syllable, these processes are indications of the end of a declarative utterance in Xhosa (Bloom Ström 2022) (Figures 1 and 2).

Spectrogram and pitch track of (28)a).

Spectrogram and pitch track of (28)b).

The additional rise in pitch in Figure 1 was not consistently used by this speaker in sentences with verum, and other speakers did not use this rise in pitch in the same example, as shown in Figure 2:[11]

| Context: disagree with the previous speaker. Speaker: ‘I guess you haven’t read the book.’ – You: disagree with this (you have read the book) |

| ndi-yi-fúnd-ile | íncwadí |

| sm1sg-om9-read-rec.dj | 9.book |

| ‘I have read the book.’ | [XHOSA_01_F_48/E26] |

| hayi | ndi-yi-fúnd-ile | íncwadí |

| no | sm1sg-om9-read-rec.dj | 9.book |

| ‘No, I have read the book.’ | [XHOSA_02_F_28/E26] |

Note that the example in (28)b) starts with a negative interjection. However, we have not found any systematic correlation between the rise in pitch and the presence/absence of an interjection. The rise in pitch appears optional.

Judging from these and other sentences in our results, we conclude that Xhosa does not express verum through a rise in pitch anywhere in the sentence. A prominence in pitch is optional, and not needed to mark a sentence as verum in Nguni. This finding confirms the previous reports in the literature mentioned above, that focus is not marked directly through prominence in pitch like it is in Germanic languages. Rather, the pitch rise we observe in examples such as (28) is what Downing and Pompino-Marschall (2013) call emphasis prosody: an optional, paralinguistic expression of emphasis, which is “gradiently realized in a particular focus context only if the speaker so desires” (Downing and Pompino-Marschall 2013: 666). However, it is still possible that pitch manipulation is used in Nguni, through the overall expansion in the pitch register of sentences with verum. We have indications in the data that this might be the case, but this would need further testing.[12]

We continue by exploring vowel length. The Nguni languages do not contrast vowel length lexically. However, there is systematic manipulation of length of the next to last (penultimate) vowel, serving at least two functions.

Firstly, alternations in the penultimate vowel play a role in an important function of intonation, namely the demarcation of syntactic borders (Cheng and Downing 2009; van der Spuy 1993). This demarcation, correlated with phonological phrasing, is linked with information structure in Nguni:

| Xhosa |

| (ba-vúl’ | íncwa:dí) |

| sm2-open.cj | 9.book |

| ‘They are opening a book.’ (answer to: ‘What are they doing?’) |

| (ba-ya-yi-vú:l’) | (íncwa:dí) |

| sm2-pres.dj-om9-open 9.book | |

| ‘They open it, the book.’ (answer to: ‘What do they do to the book?’) | |

| (Jokweni 1995: 26; 28) |

In (29)a), there is broad focus and the conjoint form of the verb is used. This form phrases with the following object, and there is penultimate lengthening on the object noun. In (29)b), on the other hand, with predication focus, the verb in the disjoint form is in its own phonological phrase, as evidenced by the lengthening of the verb’s penult. The object noun is dislocated and object-marked, and occurs in a separate phonological phrase, as indicated by the round brackets (an apostrophe indicates vowel elision).

Since the example with predication focus in (29)b) has the same morphosyntactic structure as our participants’ responses with verum, we expected our data to show the same behaviour as (29) in terms of phonological phrasing. However, contrary to expectation, we have not been able to establish a clear penultimate length in the verb at the end of the presumed phonological phrase with verum. Our interviews were aimed at leaving the choice of how to reply to the speaker, since we were searching for any expression of verum, whether morphosyntactic or prosodic. Hence, as a result, the words used in our participants’ responses are not controlled for optimal segmentation of vowels and consonants. A follow-up, experimental study, is needed. As a preliminary test, we compared measurements of 12 phrases of the sentences in Xhosa in which verum is expected. We noted that the mean length of the penultimate vowel of the verb preceding an object noun is 103 ms. That is not evidence of lengthening, when compared to vowel length measurements in Bloom Ström (2022). In that study, non-lengthened vowels in Xhosa utterances were found to be up to 100 ms long. This is very close to our average for the penultimate vowels in the verbs at the end of a presumed phonological phrase with verum.

Secondly, penultimate length is an important means to signal the end of an utterance. In a recent study, the penultimate vowels of Xhosa declaratives were calculated to have a mean length of 217 ms (Bloom Ström 2022). Results from previous studies indicate even longer mean penultimate length (Jones 2001: 31). The following example of an ordinary declarative with broad focus illustrates this penultimate length, combined with devoicing of the last vowel (Figure 3):

Spectrogram and pitch track of (30).

| Xhosa | ||

| abántwana | ba-léqa | iká:t(i) |

| 2.children | sm2-chase.cj | 5.cat |

| ‘(The) children are chasing a/the cat.’ | ||

| (Bloom Ström 2022: 92) |

This lengthening, and the suspension thereof, serves to distinguish different kinds of utterances in many Eastern and Southern Bantu languages (Hyman 2013; Hyman and Monaka 2011; Zerbian 2007, 2017). Specifically, shortening of the penultimate vowel of the utterance in Nguni is the most salient feature of polar questions, combined with an overall increase in the pitch register (Bloom Ström 2022; Jones 2001). The manipulation of vowel length, therefore, serves the intonational function of distinguishing sentence types.

With respect to the length of penultimate vowels on the utterance level, our recorded responses are sub-optimal for vowel-measuring, and our observations are therefore tentative. Our results indicate that the penultimate vowel in a sentence with verum is shortened when compared to a declarative statement without verum. Again, in a preliminary test, the average of 21 penultimate vowels of intonation phrases is 123 ms, considerably shorter than the mean values for declaratives mentioned above.[13]

In concluding this section, we note that a prominent pitch increase is not an obligatory accompaniment of verum in Xhosa, but that it can be added as an optional expression of emphasis. We furthermore observe a remarkable lack of penultimate length in sentences in which verum is expected in Xhosa, in comparison with ordinary declaratives. This is the case for the penultimate vowel of the verb as well as the penultimate vowel of the utterance.

6 Discussion

We investigated the grammatical, intonational, and lexical properties of sentences that Xhosa and Zulu speakers produced in contexts which in English require or license verum. With sentences that included a mono-transitive verb and a TAM which licenses the CJ-DJ alternation, we found that speakers consistently used object marking and the disjoint verb form in these contexts. As already noted in Sections 3 and 4 above, these morpho-syntactic devices signal that postverbal material is VP-external in Nguni. For example, a locative argument following a disjoint verb form is right-adjoined to a projection higher than VP, and an object-marked object is removed from its VP-internal argument position and right-dislocated. The syntax of the relevant part of a sentence such as (15)b) with an object-marked, dislocated object-NP is provided in (31):

| Zulu (= (15)b)) | |||

| hhayi | ma | ngi- yi -hlanz- ile | indlu |

| no | mother | sm1sg-om9-clean-rec.dj | 9.house |

| ‘No mother, I did clean the house.’ | [ZULU_10_M_24/D22] | ||

|

Following Zeller (2015), we assume that a right-dislocated object has moved to the right-peripheral specifier of a functional category (here labelled X) whose head is realized by the agreeing object marker. Furthermore, we follow Halpert (2012, 2015 and represent the disjoint markers of the present tense and recent past in a dedicated functional projection L (for licenser) that immediately dominates VP. When the verb undergoes head movement to L and X, it combines with the relevant affixes.[14]

As a result of object dislocation, the verb is now final in the phonological phrase whose right edge coincides syntactically with the right edge of VP. Consequently, given what has been observed in some of the literature on Nguni (see references further below in this paragraph), we expected the penultimate vowel of the verb to be lengthened in this context. However, as noted in Section 5, we did not observe clear evidence of penultimate lengthening with the phrase-final verbs in verum sentences in our data. It is at present difficult to interpret this result. That a lengthened penultimate vowel is an indication of the end of a phonological phrase has been noted in previous literature on Xhosa and Zulu (Jokweni 1995; Khumalo 1987; van der Spuy 1993). At the same time, several sources have noticed that this lengthening is not obligatory and that the exact conditions under which it applies remain somewhat elusive (see e.g. van der Spuy 1993: fn. 8). Cheng and Downing (2009) note that right-dislocated DPs are always preceded by a phonological phrase break in Zulu, but that focused complements inside the VP are not always followed by a phrase break. Studies of the phonetic correlates of phonological phrasing are scarce. Zeller et al. (2017) compare the phonological properties of phrase-medial verbs (which are followed by a VP-internal argument) and phrase-final verbs (followed by a dislocated argument) in Zulu, both in tenses which do not exhibit the CJ-DJ alternation (remote past and future) and in the present tense, in which the alternation exists. They conclude that a phrase-final penultimate vowel is indeed on average (but not always) lengthened and that penultimate lengthening is a strong indicator of phonological phrasing. However, the distinction between phrase-medial and phrase-final length in Zulu is not as salient as found in a study of vowel length in another Bantu language, Chichewa (Downing and Pompino-Marschall 2013). Our results suggest that the penultimate vowels of phrase-final verbs in constructions with verum are shorter than those reported on in Zeller et al. (2017). Furthermore, as discussed in Section 5, we also noted a suspension of penultimate vowel length at the end of utterances with verum. Both findings are tentative, and need to be corroborated through further, and more systematic, testing.

The fact that the VP in (31) does not include any overt material has important information-structural consequences. The VP in Nguni constitutes the focus domain (Buell 2009; Cheng and Downing 2009); narrowly focused phrases must appear inside the VP. Consequently, removing the object from the VP via right dislocation is a way of marking it as part of the background. Now recall from Section 2 that according to a polarity focus-account of verum, the propositional content of a sentence with verum is given, while the polarity of the sentence is focused. The focus account therefore offers an explanation for why the expression of verum in Nguni and similar Bantu languages is correlated, whenever possible, with object marking and the use of the disjoint verb form: in order to place focus on polarity, all other potentially focusable material needs to be removed from the focus domain. Object markers and the disjoint verb form are morphological reflexes of the fact that in a sentence with verum, postverbal arguments or adjuncts are interpreted as part of the background and consequently must be located outside the VP.

The idea that the expression of polarity focus in Nguni requires the backgrounding of all phrasal constituents brings to mind a focus-marking strategy discussed in Güldemann (2016), which he calls maximal backgrounding. Maximal backgrounding is the indirect encoding of focus by formally marking not the focus itself, but rather all the material that constitutes the background of a sentence. In Nguni, maximal backgrounding is achieved by evacuating the VP, which leaves the predicate as the potential focus host and allows for focus to be placed on polarity.

What we suggest, therefore, is that verum in Nguni is polarity focus, which however is marked only indirectly, by ensuring that all phrasal constituents are represented outside the focus domain, VP. As a consequence, the verb appears in the disjoint form in TAMs that show the CJ-DJ alternation. Furthermore, when the backgrounded material corresponds to an object of the verb, the object marker appears.

As Güldemann (2016) points out, making a single focus host available through maximal backgrounding does not entail the identification of a unique focus candidate. In Nguni, maximal backgrounding of phrasal constituents marks the predicate as a potential focus host. This allows the expression of polarity focus (32), but the same kind of sentence construction can also be used to express other types of predication focus, such as focus on the verb, (33) (see Güldemann (2003) and Section 3 for discussion):

| Xhosa | ||

| bá- ya -fudú:ka | ngowésihlá:nu | |

| sm2-pres.dj-emigrate | Friday | |

| ‘They do emigrate on Friday.’ | ||

| (Jokweni 1995: 69) |

| Xhosa | ||

| ba- yá -za:m’ | ukú-lim’ | úmbó:na |

| sm2-pres.dj-try | 15-cultivate | 3.maize |

| ‘They try to cultivate maize.’ | ||

| (Jokweni 1995: 94) |

As indicated by the disjoint verb form in the above examples, both the postverbal adverb in (32) and the infinitive in (33) are VP-external, and hence backgrounded. Consequently, the verb is the potential focus host in both (32) and (33). While (32) receives a polarity focus reading, (33) shows that maximal backgrounding also licenses contrastive verb focus. Without a context, the examples are ambiguous as to whether the verb or polarity are focused. This shows that in Xhosa and Zulu, constructions in which all phrasal material is realized VP-externally are underspecified with respect to where exactly the focus is located (see Güldemann 2003). Kerr and van der Wal (2023) propose a Background Underspecification Thesis (BUT) to capture the poly-functionality of examples such as (32) and (33).

It is important to note that maximal backgrounding as a focus marking strategy in Nguni is not only observed in predication focus contexts such as those in (32) and (33). For example, Cheng and Downing (2009) show that in ditransitive constructions in Zulu, focus on one of the objects is correlated with object marking and dislocation of the other:

| Zulu | |||||

| ízívakáshí | zí-yí-theng-el-é | ízínguːbo | ímíndeni | yâ:zo | |

| 8.visitor | sm8-om4-buy-appl-rec.cj | 10.clothes | 4.family | 4.their | |

| ‘The visitors bought clothing for their families.’ (answer to: ‘What did the visitors buy for their families?’) | |||||

| (Cheng and Downing 2009: 210) |

| Zulu | |||

| úSíph’ | ú-yí-phék-él’ | ízívakâːsh’ | ínkuːkhu |

| 1a.Sipho | sm1-om9-cook.cj-appl | 8.visitor | 9.chicken |

| ’Sipho is cooking the chicken for the visitors.’ (answer to: ‘Who is Sipho cooking the chicken for?’) | |||

| (Cheng and Downing 2009: 211) |

In (34), the indirect object ímíndeni yâzo, ‘their families’ is part of the background, and hence object-marked and right-dislocated. Consequently, the direct object ízíngubo, ‘clothes’ can be focused. In (35), it is the direct object ínkukhu, ‘chicken’ which is object-marked and right-dislocated, and focus can be placed on the indirect object ízívakáshi, ‘visitors’.

Note that in (34) and (35), the verb is in the conjoint form, reflecting the fact that the non-dislocated object is VP-internal, and hence in focus. Now recall that our data have shown that in verum-contexts, ditransitive verbs appear in the disjoint form. The sentence in (36), which repeats example (26)a) from Section 4, was produced as an answer to a biased question in which the speaker expressed doubt that Nwabisa gave the children money:

| ‘Did Nwabisa really give the children money’? |

| Yebo, | uNwabisa | u-zi-nik-ile | izingane | imali |

| yes | Nwabisa | sm1-om10-give-rec.dj | 10.children | 9.money |

| ‘Yes, Nwabisa did give the children money.’ | [ZULU_06_F_23/C17_1] |

The disjoint form in the response in (36) is evidence that, in contrast to (34) and (35), both object arguments are dislocated.[15] This follows from the idea that in a sentence with verum, all arguments of the verb form must be part of the background, and therefore have to be realized in a VP-external position in order for focus to be placed on polarity. As discussed in Section 2, positive polarity focus requires a negative focus antecedent. In (36), this antecedent is provided by the doubt expressed in the biased question, which makes the proposition that Nwabisa did not give money to the children salient. By marking focus on polarity, the focus alternative set of the response in (36) includes this proposition, and therefore, the response is felicitous in this context.

In Section 4, we showed that the same type of construction, with both arguments dislocated, was also produced by speakers in response to an unbiased polar question (compare (25)b)). One possible interpretation of this observation would be to assume that unbiased polar questions in Nguni, like their biased counterparts, require answers with polarity focus. However, this assumption is at odds with the semantic characterization of polarity focus discussed in Section 2 above, according to which a sentence with polarity focus expressing proposition p presupposes the existence of a salient focus antecedent ¬p in the discourse (Goodhue 2022). An unbiased polar question does not explicitly provide such an antecedent, and polarity focus is therefore sometimes considered marked in such contexts. Since the participants in our study, when asked to answer an unbiased polar question, also had no reason to assume an implicit focal target with contrasting polarity, we conclude that their responses cannot be interpreted as expressing polarity focus.

Nevertheless, answers to unbiased polar questions in Nguni display the same grammatical form as sentences with polarity focus. We suggest that this follows from the fact that answers to such questions are all-given (Goodhue 2022). Therefore, in the answers as well, all phrasal material must be backgrounded, and VP-internal arguments are hence dislocated in Nguni. However, in contrast to the cases of maximal backgrounding discussed above, we contend that in the response to an unbiased question in Nguni, the backgrounding of phrasal material is not accompanied by focus marking. As argued by Kratzer and Selkirk (2020), the new part of the answer to a constituent question can be “merely new”, i.e. a constituent can express new information without being marked as focus, in which case no alternatives are introduced. For example, if the subject John in the answer to the subject question in (37)A) is focused, then the answer in (37)B) is appropriate only if the contrasting proposition that someone other than John has cleaned the kitchen is salient in the discourse. However, John in (37)B) can also merely express new information. In that case, the VP in (37)B) is marked as given (and hence deaccented), but no element is marked as focus, and no contrast is expressed:

| Who cleaned the room? |

| john cleaned the room. |

We extend Kratzer and Selkirk’s analysis to sentence polarity. In the answer to a polar question in Nguni, everything but polarity is given, and phrasal material must therefore be backgrounded by being placed outside the VP. When an alternative proposition with contrasting polarity is salient in the discourse (as is the case, for example, with biased polar questions such as (36)), focus is placed on polarity. However, when no such focal target exists, the polarity of the sentence simply represents the new information that answers the question. No contrast with an alternative proposition is expressed.[16]

As discussed in Section 2, Gutzmann et al. (2020) argue against focus accounts of verum, which they subsume under the FAT. According to Gutzmann et al. (2020: 16), the FAT predicts verum and focus “to be marked by the same strategies in a given language”, and they provide evidence from a number of languages that this is not always the case. However, we have shown that, as far as the Nguni languages are concerned, this prediction of the FAT is fulfilled: in sentences that appear in verum contexts, Xhosa and Zulu speakers mark phrasal constituents as the background, which in turn licenses focus marking of polarity. This maximal backgrounding strategy resembles the strategy that is used to express narrow focus on a VP-internal constituent in sentences with multiple arguments or adjuncts. Our results therefore demonstrate that the parallel between the strategies used for the expression of focus and verum is not only found in languages such as German or English, in which both phenomena are marked through pitch accent. It is also attested in languages which for the most part use non-intonational means to structure the propositional content of a sentence to distinguish between old and new information.

7 Conclusions

In this paper we examined the prosodic, lexical, and morpho-syntactic properties of Xhosa and Zulu sentences in contexts which have been shown to license verum in languages such as English. Although there are indications that manipulation of vowel length plays a role in sentences with verum, our results are not conclusive in this respect. We do conclude that pitch rise is not an obligatory accompaniment of verum in Nguni languages, nor are lexical additions. The only reliable sign of verum is found in the morpho-syntax of (a subset of) sentences that appear in verum contexts in Nguni: Verbs which display the CJ-DJ alternation, or which select arguments that can be object-marked, signal that postverbal constituents are VP-external through affixation. The VP-external material is thereby marked as backgrounded, which is a necessary condition for inflectional verbal categories, including polarity, to be focused. We conclude that verum in Nguni is polarity focus, which is indirectly expressed via maximal backgrounding, by placing otherwise focusable constituents outside VP.

Abbreviations

We follow the Leipzig Glossing Rules. Abbreviations and conventions used in this paper that cannot be found there are the following:

- AS

-

associative

- CJ

-

conjoint

- DJ

-

disjoint

- OM

-

object marker

- REC

-

recent past

- REM

-

remote

- SM

-

subject marker

Numbers not followed by sg or pl identify noun class.

Acknowledgments

We thank Onelisa Slater and Mfundo Didi for their invaluable assistance in data collection and transcriptions in this project, for Xhosa and Zulu respectively, as well as two reviewers and the editors of this special issue for their constructive comments. We gratefully acknowledge the time and effort contributed by our participants. The research for this article was conducted as part of research projects funded by the Swedish Research Council (2017-01811 and 2021–03125).

References

Adams, Nikki. 2010. The Zulu ditransitive verb phrase. Chicago: The University of Chicago dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Andrason, Alexander & Marianna Visser. 2016. The mosaic evolution of left dislocation in Xhosa. Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics Plus 50. 139–158. https://doi.org/10.5842/50-0-720.Search in Google Scholar

Bill, Cory & Todor Koev. 2021. Verum accent IS verum, but not always focus. Proceedings of the Linguistic Society of America 6. 188–202. https://doi.org/10.3765/plsa.v6i1.4959.Search in Google Scholar

Bloom Ström, Eva-Marie. 2022. The role of pitch and vowel length in Xhosa intonation. Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics Plus 62. 81–111.10.5842/62-2-894Search in Google Scholar

Boersma, Paul & David Wennink. 2023. Praat: Doing phonetics by computer [Computer program]. Version 6.3.08. Available at: http://www.praat.org.Search in Google Scholar

Buell, Leston. 2005. Issues in Zulu verbal morphosyntax. Los Angeles: University of California dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Buell, Leston. 2009. Evaluating the immediate postverbal position as a focus position in Zulu. In Masangu Matondo, Fiona Mc Laughlin & Eric Potsdam (eds.), Selected Proceedings of the 38th Annual Conference on African Linguistics, 166–172. Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Proceedings Project.Search in Google Scholar

Büring, Daniel. 2016. Intonation and meaning. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199226269.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Carstens, Vicki & Loyiso Mletshe. 2015. Radical defectivity: Implications of Xhosa expletive constructions. Linguistic Inquiry 46. 187–242. https://doi.org/10.1162/ling_a_00180.Search in Google Scholar

Carstens, Vicki & Loyiso Mletshe. 2016. Negative concord and nominal licensing in Xhosa and Zulu. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 34. 761–804. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-015-9320-x.Search in Google Scholar

Cheng, Lisa L. & Laura J. Downing. 2009. Where’s the topic in Zulu? The Linguistic Review 26. 207–238. https://doi.org/10.1515/tlir.2009.008.Search in Google Scholar

Cheng, Lisa L. & Laura J. Downing. 2012. Against FocusP: Evidence from Durban Zulu. In Ivona Kučerová & Ad Neeleman (eds.), Contrasts and positions in information structure, 247–266. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511740084.012Search in Google Scholar

Diercks, Michael. 2022. Information structure is syntactic: Evidence from Bantu languages. Pomona College Unpublished manuscript.Search in Google Scholar

Dik, Simon, Maria E. Hoffmann, Jan, R. de Jong, Sie Ing Djiang, Harry Stroomer & Lourens de Vries. 1981. On the typology of focus phenomena. In Teun Hoekstra, Harry van der Hulst & Michael Moortgat (eds.), Perspectives on functional grammar, 41–74. Dordrecht: Foris.Search in Google Scholar

Doke, Clement M. 1997 [1927]. Textbook of Zulu grammar. Capetown: Maskew Miller Longman.Search in Google Scholar

Downing, Laura J. 2012. On the (Non-)congruence of focus and prominence in Tumbuka. In Nikki Adams, Michael Marlo, Tristan Purvis & Michelle Morrison (eds.), Selected proceedings of ACAL, vol. 42, 122–133. Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Proceedings Project.Search in Google Scholar

Downing, Laura J. & Larry M. Hyman. 2016. Information structure in Bantu. In Caroline Féry & Shinichiro Ishihara (eds.), The Oxford handbook of information structure, online edn. Oxford: Oxford Academic.10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199642670.013.010Search in Google Scholar

Downing, Laura J. & Bernd Pompino-Marschall. 2013. The focus prosody of Chichewa and the stress-focus constraint: A response to samek-Lodovici (2005). Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 31. 647–681. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-013-9192-x.Search in Google Scholar

Goodhue, Daniel. 2018. On asking and answering biased polar questions. Montréal: McGill University dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Goodhue, Daniel. 2022. All focus is contrastive: On polarity (verum) focus, answer focus, contrastive focus and givenness. Journal of Semantics 39. 117–158. https://doi.org/10.1093/jos/ffab018.Search in Google Scholar

Güldemann, Tom. 2003. Present progressive vis-à-vis predication focus in Bantu. A verbal category between semantics and pragmatics. Studies in Language 27. 323–360. https://doi.org/10.1075/sl.27.2.05gul.Search in Google Scholar

Güldemann, Tom. 2016. Maximal backgrounding = focus without (necessary) focus encoding. Studies in Language 40. 551–590.10.1075/sl.40.3.03gulSearch in Google Scholar

Guthrie, Malcolm. 1967 [1971]. Comparative Bantu: An introduction to the comparative linguistics and prehistory of the Bantu languages. London: Gregg International.Search in Google Scholar

Gutzmann, Daniel & Elena Castroviejo Miró. 2011. The dimensions of verum. In Olivier, Bonami & Patricia Cabredo-Hofherr (eds.), Empirical issues in syntax and semantics 8, 143–165. Paris: Colloque de syntaxe et sémantique à Paris.Search in Google Scholar

Gutzmann, Daniel, Katharina Hartmann & Lisa Matthewson. 2020. Verum focus is verum, not focus: Cross-linguistic evidence. Glossa: A Journal of General Linguistics 5. 1–48. https://doi.org/10.5334/gjgl.347.Search in Google Scholar

Halpert, Claire. 2012. Argument licensing and agreement in Zulu. Cambridge, MA: MIT dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Halpert, Claire. 2015. Argument licensing and agreement. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190256470.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Höhle, Tilman. 1992. Über Verum-Fokus im Deutschen. In Joachim Jacobs (ed.), Informationsstruktur und Grammatik, 112–142. Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag.10.1007/978-3-663-12176-3_5Search in Google Scholar

Hyman, Larry M. 1999. The interaction between focus and tone in Bantu. In Georges Rebuschi & Laurice Tuller (eds.), The grammar of focus, 151–177. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/la.24.06hymSearch in Google Scholar

Hyman, Larry M. 2013. Penultimate lengthening in Bantu. Analysis and spread. In Balthasar Bickel, Lenore A. Grenoble & David A. Peterson (eds.), Language typology and historical contingency: In honor of Johanna Nichols, 309–330. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/tsl.104.14hymSearch in Google Scholar

Hyman, Larry M. & Kemmonye C. Monaka. 2011. Tonal and non-tonal intonation in shekgalagari. In Sonia Frota, Gorka Elordieta & Pilar Prieto (eds.), Prosodic categories: Production, perception and comprehension, 267–290. Dordrecht: Springer.10.1007/978-94-007-0137-3_12Search in Google Scholar

Hyman, Larry M. & John R. Watters. 1984. Auxiliary focus. Studies In African Linguistics 15. 233–273. https://doi.org/10.32473/sal.v15i3.107511.Search in Google Scholar

Jokweni, Mbulelo W. 1995. Aspects of IsiXhosa phrasal phonology. Urbana-Champaign, IL: University of Illinois dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Jones, Catherine Jacquelynn Julia. 2001. Queclaratives in Xhosa: An acoustic and perceptual analysis. Stellenbosch: University of Stellenbosch dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Jones, Catherine Jacquelynn Julia & Justus C. Roux. 2003. Acoustic and perceptual qualities of queclaratives in Xhosa. South African Journal of African Languages 23. 223–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/02572117.2003.10587220.Search in Google Scholar

Jordanoska, Izabela. 2020. The pragmatics of sentence final and second position particles in Wolof. Vienna: University of Vienna dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Kanerva, Jonni M. 1990. Focus and phrasing in Chichewa phonology. New York: Garland Publishing.Search in Google Scholar

Kerr, Elizabeth J. & Jenneke van der Wal. 2022. Indirect verum marking in 10 Bantu languages. Paper presented at Bantu9, Malawi, July 2022.Search in Google Scholar

Kerr, Elizabeth & Jenneke van der Wal. 2023. Indirect truth marking via backgrounding: Evidence from Bantu. Zeitschrift für Sprachwissenschaft 42(3). 443–492. https://doi.org/10.1515/zfs-2023-2010.Search in Google Scholar

Khumalo, James Steven Mzilikazi. 1987. An autosegmental account of Zulu phonology. Johannesburg: University of the Witwatersrand dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Kocher, Anna. 2023. A sentence mood account for Spanish verum. Glossa: A Journal of General Linguistics 8(1). 1–47. https://doi.org/10.16995/glossa.8784.Search in Google Scholar

Kratzer, Angelika & Elizabeth Selkirk. 2020. Deconstructing information structure. Glossa: A Journal of General Linguistics 5(1). 113. 1–53. https://doi.org/10.5334/gjgl.968.Search in Google Scholar

Lippard, Hannah, Justine Sikuku, Crisófia Langa da Câmara, Rose Letsholo, Madelyn Colantes, Kang (Franco) Liu & Michael Diercks. Forthcoming. Emphatic interpretations of object marking in Bantu languages. Studies In African Linguistics.Search in Google Scholar

Lohnstein, Horst. 2012. Verumfokus–Satzmodus–Wahrheit. In Horst Lohnstein & Hardarik Blühdorn (eds.), Fokus–wahrheit–negation (Linguistische Berichte Sonderheft 18), 31–67. Hamburg: Buske.Search in Google Scholar

Lohnstein, Horst. 2016. Verum focus. In Caroline Féry & Shinichiro Ishihara (eds.), The Oxford handbook of information structure, online edn. Oxford: Oxford Academic.10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199642670.013.33Search in Google Scholar

Marten, Lutz & Jenneke van der Wal. 2014. A typology of Bantu subject inversion. Linguistic Variation 14. 318–368. https://doi.org/10.1075/lv.14.2.04mar.Search in Google Scholar

Matthewson, Lisa & Jennifer Glougie. 2018. Justification and truth: Evidence from languages of the world. In Stephen Stich, Masaharu Mizumoto & Eric Mccready (eds.), Epistemology for the rest of the world, 149–186. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

McLaren, James. 1955. A Xhosa grammar. Cape Town: Longmans Green & Co.Search in Google Scholar

Nurse, Derek. 2008. Tense and aspect in Bantu. New York: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780199239290.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Romero, Maribel & Chung-Hye Han. 2004. On negative yes/no questions. Linguistics and Philosophy 27. 609–658. https://doi.org/10.1023/b:ling.0000033850.15705.94.10.1023/B:LING.0000033850.15705.94Search in Google Scholar

Rooth, Mats. 1985. Association with focus. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Rooth, Mats. 1992. A theory of focus interpretation. Natural Language Semantics 1. 75–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02342617.Search in Google Scholar

Samko, Bern. 2016. Syntax & information structure: The grammar of English inversions. Santa Cruz, CA: UC Santa Cruz dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Servidio, Emilio. 2015. Polarity focus constructions in Italian. Rivista di Grammatica Generativa 37. 121–163.Search in Google Scholar

Sikuku, Justine & Michael Diercks. Forthcoming. Object marking in Lubukusu. At the interface of pragmatics and syntax. Berlin: Language Science Press.Search in Google Scholar

Sikuku, Justine, Michael Diercks & Michael Marlo. 2018. Pragmatic effects of clitic doubling: Two kinds of object markers in Lubukusu. Linguistic Variation 18. 359–429. https://doi.org/10.1075/lv.00027.sik.Search in Google Scholar

Statistics South Africa. 2012. Census 2011 statistical release – P0301.4. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa.Search in Google Scholar

Tshabe, S. L. & F. M. Shoba. 2006. The greater dictionary of isiXhosa, volume 1 A-J. Alice: IsiXhosa National Lexicography Unit.Search in Google Scholar

Turk, Alice, Satsuki Nakai & Mariko Sugahara. 2012. Acoustic segment durations in prosodic research: A practical guide. In Sudhoff Stefan, Lenertova Denisa, Meyer, Roland, Pappert Sandra, Augurzky Petra, Mleinek Ina, Richter Nicole & Schließer Johannes (eds.), Methods in empirical prosody research, 1–28. Berlin & Boston: De Gruyter.Search in Google Scholar

Van der Spuy, Andrew. 1993. Dislocated noun phrases in Nguni Lingua 90. 335–355. https://doi.org/10.1016/0024-3841(93)90031-q.Search in Google Scholar

Van der Wal, Jenneke. 2011. Focus excluding alternatives: Conjoint/disjoint marking in Makhuwa. Lingua 121. 1734–1750. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2010.10.013.Search in Google Scholar

Van der Wal, Jenneke. 2017. What is the conjoint/disjoint alternation? Parameters of crosslinguistic variation. In Jenneke van der Wal & Larry M. Hyman (eds.), The conjoint/disjoint alternation in Bantu, 14–60. Berlin & Boston: De Gruyter.10.1515/9783110490831-002Search in Google Scholar

Van der Wal, Jenneke & Larry M. Hyman (eds.). 2017. The conjoint/disjoint alternation in Bantu. Berlin: De Gruyter.Search in Google Scholar

Voeltz, F. K. Erhard. 2004. Long and short verb forms in Zulu. Unpublished manuscript, University of Cologne.Search in Google Scholar

Wilder, Chris. 2013. English ‘emphatic do. Lingua 128. 142–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2012.10.005.Search in Google Scholar

Zeller, Jochen. 2015. Argument prominence and agreement: Explaining an unexpected object asymmetry in Zulu. Lingua 156. 17–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2014.11.009.Search in Google Scholar

Zeller, Jochen, Sabine Zerbian & Toni Cook. 2017. Prosodic evidence for syntactic phrasing in Zulu. In Jenneke van der Wal & Larry M. Hyman (eds.), The conjoint/disjoint alternation in Bantu, 295–328. Berlin & Boston: De Gruyter.10.1515/9783110490831-011Search in Google Scholar

Zerbian, Sabine. 2006. Expression of information structure in Northern Sotho. Berlin: Humboldt University dissertation.10.21248/zaspil.45.2006.331Search in Google Scholar

Zerbian, Sabine. 2007. Investigating prosodic focus marking in Northern Sotho. In Katharina Hartmann, Enoch Aboh & Malte Zimmermann (eds.), Focus strategies in African languages: The interaction of focus and grammar in Niger-Congo and Afro-Asiatic, 55–79. Berlin & Boston: De Gruyter.10.1515/9783110199093.1.55Search in Google Scholar

Zerbian, Sabine. 2017. Sentence intonation in Tswana (Sotho-Tswana group). In Laura J. Downing & Annie Rialland (eds.), Intonation in African tone languages, 393–433. Berlin & Boston: De Gruyter.10.1515/9783110503524-012Search in Google Scholar

Zimmermann, Malte & Daniel Hole. 2008. Predicate focus, verum focus, verb focus: Similarities and difference. Paper presented at the potsdam-London IS meeting. 12.12.2008.Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Introduction special issue: marking the truth: a cross-linguistic approach to verum

- Indirect truth marking via backgrounding: evidence from Bantu

- Verum in Xhosa and Zulu (Nguni)

- Clausal doubling and verum marking in Spanish

- Whether-exclamatives: a verum strategy

- Getting the facts right: focus on adverbial verum marking in German

- Verum, focus and evidentiality in Conchucos Quechua

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter