Abstract

In modern Turkish, the apostrophe is used to separate proper names from inflectional endings (İzmir’de ‘in İzmir’). This is not the case with inflected common nouns (şehirde ‘in the city’). In this respect, the apostrophe constitutes an instance of graphematic dissociation between proper names and common nouns. Interestingly, the apostrophe was originally employed to transliterate hamza and ayn in Arabic and Persian loanwords (san’at ‘art’). However, these loanwords gradually lost the apostrophe (sanat ‘art’). This implies that Turkish experienced a graphematic change whereby the apostrophe developed from a phonographic marker of glottal stop into a morphographic marker of morpheme boundaries in proper names. This refunctionalization process is illustrated by a diachronic corpus analysis based on selected issues of the newspaper Cumhuriyet from 1929–1975. The findings reveal that the use of the apostrophe with proper names was triggered by foreignness. More specifically, the apostrophe first occurred with foreign names to highlight morpheme boundaries (Eden’in ‘of Eden’) and then expanded to native names via animacy (Doğan’ın ‘of Doğan’).

1 Introduction

In Turkish, the apostrophe separates proper names from inflectional endings. This is the case with the personal name Emir and the place name İzmir (Emir’in ‘of Emir’, İzmir’in ‘of İzmir’), as shown in Table 1. In contrast, the apostrophe does not occur with inflected common nouns such as amir ‘chief’ and şehir ‘city’ (amirin ‘of the chief’, şehrin ‘of the city’).

Apostrophe and capitalization in Turkish proper names.[1]

| Case | Proper name | Common noun | ||

| Personal name | Place name | Human | Inanimate | |

| Accusative | Emir’i | İzmir’i | amiri | şehri |

| Dative | Emir’e | İzmir’e | amire | şehre |

| Locative | Emir’de | İzmir’de | amirde | şehirde |

| Ablative | Emir’den | İzmir’den | amirden | şehirden |

| Genitive | Emir’in | İzmir’in | amirin | şehrin |

This implies that there is a graphematic dissociation between proper names and common nouns. Dissociations are defined in terms of formal differences between proper names and common nouns at the phonological, morphosyntactic, and graphematic level (see Nübling 2005; Nübling et al. 2015: 64–92). With regard to graphematic dissociations, Nübling et al. (2015: 86–92) distinguish between capitalization, graphemes, and syngraphemes (apostrophe, hyphen, etc.). In addition to the apostrophe, Turkish exhibits capitalization, which applies to proper names (Emir, İzmir), but not to common nouns (amir ‘chief’, şehir ‘city’). In Turkish, dissociations are found at the graphematic level, but not at the morphosyntactic level since proper names do not differ from common nouns with respect to inflection.

The apostrophe contributes to the principle of onymic schema constancy, according to which the shape of proper names is preserved in order to enable their recognition and processing (see Nübling 2005: 50–51). The need to retain the proper name body has been shown to have an effect on the phonology, morphosyntax, and graphematics of German (see Nübling 2017). In Turkish, however, the principle of onymic schema constancy is restricted to graphematics where the apostrophe has the function of highlighting morpheme boundaries. Moreover, common nouns and proper names can differ with respect to spelling although they share the same pronunciation. This is illustrated by the graphematic representation of /b d ɡ dʒ/ in word-final and word-medial position (see Table 2). In word-final position, /b d ɡ dʒ/ undergo devoicing, giving rise to [p t k tʃ], respectively. When a vowel-initial suffix is attached to the stem, /b d ɡ dʒ/ are syllabified and occupy the word-medial onset. Such is the case with the accusative ending -(y)I.[2] In word-medial intervocalic position, /b d dʒ/ are retained while /ɡ/ experiences deletion via lenition (see Lees 1961: 51–52 for word-final devoicing and word-medial deletion).[3] As a result of deletion, the preceding vowel undergoes lengthening (see Ünal-Logacev et al. 2019). This phonologically conditioned allomorphy is reflected in the spelling of common nouns such as mehtap ‘moonlight’, umut ‘hope’, ışık ‘light’, and sevinç ‘joy’, which show the alternation of the graphemes <p t k ç> and <b d ğ c> in word-final and word-medial position, respectively (see Lewis 1967: 10–12 for examples). These phonological processes also apply to the corresponding personal names Mehtap, Umut, Işık, and Sevinç. Thus, we find devoicing in word-final position (Mehtap [mɛhtɑp], Işık [ɯʃɯk]), but retention or deletion in word-medial position (Mehtap’ı [mɛhtɑbɯ], Işık’ı [ɯʃɯːɯ]). However, /b d ɡ dʒ/ are represented with the graphemes <p t k ç> both in word-final and in word-medial position. That is, in contrast to common nouns, proper names do not display graphematic alternations.

Onymic schema constancy in Turkish proper names.

| Phoneme | Graphematic alternation | Common noun | Proper name |

| /b/ | <-p>, <-b-> | mehtap - mehtabı | Mehtap - Mehtap’ı |

| /d/ | <-t>, <-d-> | umut - umudu | Umut - Umut’u |

| /ɡ/ | <-k>, <-ğ-> | ışık - ışığı | Işık - Işık’ı |

| /dʒ/ | <-ç>, <-c-> | sevinç - sevinci | Sevinç - Sevinç’i |

The apostrophe has been intensively studied for German, both from a diachronic and synchronic perspective. Nübling (2014; 2017: 360–361) provides a comprehensive overview of the development of the apostrophe, showing that its occurrence with inflected proper names was motivated by animacy (personal names prior to place names) and foreignness (foreign names prior to native names) (see Kempf 2019: 135–136 for foreign personal names). With regard to Turkish, little is known about the factors that conditioned the emergence and development of the apostrophe with proper names. The goal of this paper is to provide a diachronic account of apostrophe usage from the introduction of the new Latin-based alphabet in 1928 to the present.

The paper is structured as follows: Section 2 discusses the functions of the apostrophe from a typological perspective. Section 3 deals with the 1928 alphabet revolution. Section 4 gives a diachronic overview of the functions of the apostrophe in newspapers and the Spelling Dictionary. Section 5 presents a diachronic corpus analysis which examines the use of the apostrophe with Arabic and Persian loanwords and inflected proper names in the newspaper Cumhuriyet. Section 6 summarizes the main findings of our study.

2 Functions of the apostrophe

Cross-linguistically, the apostrophe has been shown to have different functions (see Gallmann 1989: 102; Bunčić 2004; Scherer 2013). We will distinguish between diacritic, deletion, phonographic, and morphographic markers (see Table 3).[4] As a diacritic marker, the apostrophe is added to consonant letters for denoting duration and place of articulation. For example, we find the apostrophe in Jèrriais for geminates (s’s /zː/, ss’s /sː/, t’t /tː/), in Slovak for the palatal consonants t’ [c], d’ [ɟ], l’ [ʎ] before back vowels or in word-final position (t’ava [caʋa] ‘camel’, cakat’ [tʃakac] ‘to wait’), and in Ukrainian for the non-palatalization of the consonants <б п м в ф р> when adjacent to the diphthongs <я ю є ї> (п’ять [pjatj] ‘five’) (Pugh and Press 1999: 31; Rothstein 2006: 419; Finbow 2016: 686). As a deletion marker, the apostrophe is employed for the omission of a letter (or letters). The apostrophe has been mainly associated with this function in the literature (see Bunčić 2004: 186–187). As a phonographic marker, the apostrophe is related to consonantal segments, especially the glottal stop [Ɂ]. This is the case in Hawaiian and Mohawk (Elbert and Pukui 1979: 10; Mithun 1996: 159). Examples from Mohawk are ksa:’a ‘child’ and kati’ ‘thus’ (Mithun 1996: 160–161). As a morphographic marker, the apostrophe highlights word and morpheme boundaries. Gallmann (1985: 33, 101–104) makes a distinction between the pragmatic-morphological principle for proper names and the graphematic-morphological principle for abbreviations, acronyms, and numerals. In German, for example, we find the pragmatic-morphological principle with inflected personal names and place names containing genitive -s (Gino’s ‘Gino’s’, Berlin’s ‘of Berlin’) as well as with derived personal names (Einstein’sche Zeit-Dilatation ‘Einsteinian time dilation’). In turn, we find the graphematic-morphological principle with inflected abbreviations (LKW’s ‘trucks’), acronyms (UFO’s ‘UFOs’), and loanwords (T-Shirt’s ‘T-shirts’) as well as with derived abbreviations (DRK’ler ‘members of the German Red Cross’) (examples taken from Bankhardt 2010 and Scherer 2010). Both principles have in common that they constitute word shape preservation strategies (see Nowak and Nübling 2017). Interestingly, we rarely find languages where the apostrophe exclusively functions as a morphographic marker. However, we will see that in Turkish the apostrophe is mainly associated with this function (see Section 4).

Functions of the apostrophe in selected languages.

| Language | Diacritic marker | Deletion marker | Phonographic marker | Morphographic marker |

| Jèrriais, Slovak, Ukrainian | ✓ | |||

| Hawaiian, Mohawk | ✓ | |||

| Catalan, French, Greek | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Cupeño | ✓ | ✓ |

Importantly, the different functions of the apostrophe can co-occur and even overlap. In this respect, Scherer (2013: 77) talks about the polyfunctionality of the apostrophe. For example, in Catalan, French, and Greek the apostrophe serves simultaneously as a deletion and a morphographic marker since the apostrophe coincides with a word or morpheme boundary. For example, in Greek the apostrophe is associated with vowel deletion at word boundaries, as in το ’κανα (< το έκανα) ‘I did it’ (Holton et al. 2012: 39). Similarly, in Catalan and French the apostrophe highlights vowel deletion at morpheme boundaries, as in Cat. l’home (< el home) and Fr. l’homme (< le homme) ‘the man’. Note that the apostrophe is optional in Greek, but obligatory in Catalan and French. In turn, in Cupeño, an Uto-Aztecan language formerly spoken in Southern California, the apostrophe functions at the same time as a phonographic and a morphographic marker since the glottal stop, which is represented by apostrophe, is restricted to word-final position (tavxaa’ ‘to work’) and word-medial position, both after vowel-final prefixes (pe’amu ‘s/he hunted’) and before vowel-initial suffixes (tavxaa’ily ‘work’) (Hill 2005: 20–21, 50–53).

With regard to morphographic markers, we can distinguish between syngraphemes such as the apostrophe and hyphen (see Gallmann 1996 for a comprehensive overview). Thus, the function as a morphographic marker can be performed by the apostrophe, by the hyphen, or by both (see Table 4). In Turkish, we only find the apostrophe as a morphographic marker while in Armenian, Romanian, and Spanish we only find the hyphen as a morphographic marker (RAE/ASALE 2010: 411–422; DOOM 2005; Dum-Tragut 2009: 714–716). For example, in Romanian the hyphen functions as a morphographic marker with cliticization (dă-l ‘s/he gives it’), certain derivational prefixes and compounds (ex-ministru ‘ex-minister’, prim-ministru ‘Prime Minister’), derivation of foreign names and numerals (shakespeare-ian ‘Shakespearean’, 16-imi ‘16th’), and the suffixed definite article occurring with abbreviations and acronyms (pH-ul ‘the pH’), names of letters and sounds (x-ul ‘the x’), and loanwords and foreign place names whose pronunciation differs from the spelling (show-ul ‘the show’, Bordeaux-ul ‘Bordeaux’) (see DOOM 2005: xl–xliii, lxiv–lxxvi). In other languages, by contrast, we find both the apostrophe and the hyphen as morphographic markers. This is the case in Catalan (IEC 2017: 105–109, 111–127), Finnish (Korpela 2015), French (Grevisse and Goosse 2016: 114–122), and German (Gallmann 1989). For example, in Catalan the apostrophe functions as both a deletion and a morphographic marker with the definite article el/la, the preposition de ‘from/of’, and reduced pronouns while the hyphen functions as a morphographic marker with full pronouns and some derivational prefixes and compounds (cf. l’agafa ‘s/he takes it’ vs. agafar-lo ‘to take it’). In Finnish, the apostrophe, the hyphen, and the colon function as morphographic markers. The apostrophe occurs with inflected loanwords and foreign place names whose pronunciation differs from the spelling (show’t ‘the shows’, Bordeaux’ssa ‘in Bordeaux’) while the hyphen occurs at the word-internal boundary of compounds with identical adjacent vowels (kuorma-auto ‘truck’). In addition, the colon is employed with inflected abbreviations (UM:ssä < ulkoministeriössä ‘in the Foreign Office’) and inflected numerals (3:ssä ‘in 3’), but not with inflected acronyms (NATOssa ‘in NATO’).

The apostrophe and hyphen as morphographic markers in selected languages.

| Apostrophe | Hyphen | |

| Turkish | ✓ | |

| Armenian, Romanian, Spanish | ✓ | |

| Catalan, Finnish, French, German | ✓ | ✓ |

From a diachronic perspective, the functions of the apostrophe can vary as a result of a graphematic change. For example, in German the apostrophe was originally a phonographic marker which subsequently developed additional functions, serving also as a deletion and morphographic marker (see Nübling 2014). A similar development has taken place in Turkish, as we will see in the ensuing sections.

3 The Turkish alphabet revolution

The early years of the Turkish Republic can be characterized as an era of westernization, which implies that there was a break with previous traditions. The initiated reforms include the abolition of the caliphate, the Islamic calendar, and the Ottoman alphabet. The replacement of the Arabic-based alphabet by a Latin-based one is known as the Turkish alphabet revolution (harf devrimi).[5] This section explores the historical background that led to the alphabet revolution, the contributions of the Language Commission (Dil Encümeni) and the Turkish Language Association (Türk Dil Kurumu), and the role of newspapers in introducing the new alphabet to the literate public.

The Ottoman alphabet was not well-suited for Turkish (see Taşdemir 2006: 30–39). On the one hand, some Arabic sounds were not present in spoken Turkish. This is the case with  [θ],

[θ],  [χ], etc. On the other, some Turkish sounds could be represented by a single Arabic letter. For example,

[χ], etc. On the other, some Turkish sounds could be represented by a single Arabic letter. For example,  represented the vowels [y u œ ɔ].[6] First debates about the consequences of the Ottoman alphabet on illiteracy among the population arose in the mid-nineteenth century (see Şimşir 1992: 18–29; Taşdemir 2006: 3–18; Strauss 2008: 487–489; Yılmaz 2013: 63–64; Türker 2019: 38–87). After the Turkish Republic was established, these debates were still pursued in parliament and newspapers (see Levend 1960: 392–400; Doğaner 2005: 30–33; Taşdemir 2006: 18–29; Biçici and Yıldız Özlü 2020). The adoption of a new Latin-based alphabet was publicly announced by President Mustafa Kemal Atatürk on 9 August 1928. The Alphabet Law (Türk Harflerinin Kabul ve Tatbiki Hakkında Kanun ‘Law of the adoption and application of Turkish letters’) was passed by the Turkish Grand National Assembly on 1 November 1928 (see Şimşir 1992: 208–216).

represented the vowels [y u œ ɔ].[6] First debates about the consequences of the Ottoman alphabet on illiteracy among the population arose in the mid-nineteenth century (see Şimşir 1992: 18–29; Taşdemir 2006: 3–18; Strauss 2008: 487–489; Yılmaz 2013: 63–64; Türker 2019: 38–87). After the Turkish Republic was established, these debates were still pursued in parliament and newspapers (see Levend 1960: 392–400; Doğaner 2005: 30–33; Taşdemir 2006: 18–29; Biçici and Yıldız Özlü 2020). The adoption of a new Latin-based alphabet was publicly announced by President Mustafa Kemal Atatürk on 9 August 1928. The Alphabet Law (Türk Harflerinin Kabul ve Tatbiki Hakkında Kanun ‘Law of the adoption and application of Turkish letters’) was passed by the Turkish Grand National Assembly on 1 November 1928 (see Şimşir 1992: 208–216).

The Language Commission (Dil Encümeni) was formed in May 1928 in order to develop the new alphabet.[7] The first version was presented in the Elifba Report (Elifba Raporu) in the same year (see Türker 2019: 108–123). The publications of the Language Commission include a grammar (Muhtasar Türkçe gramer ‘Concise Turkish grammar’), an alphabet (Yeni Türk alfabesi ‘New Turkish alphabet’), and a spelling dictionary (İmlâ Lûgati). The new alphabet is comprised of twenty-nine letters. Phonological processes such as word-final devoicing are reflected in the alternation of the graphemes <b d ğ c> and <p t k ç> in word-medial and word-final position, respectively (see Table 2 for examples). Soft <ğ> (yumuşak g) replaced the Ottoman letters  [ɣ] and

[ɣ] and  [j], which followed back and front vowels, respectively. In addition, we find the apostrophe (kesme işareti), the circumflex (uzatma işareti, düzeltme işareti), and the hyphen (bağlama çizgisi).[8] The Spelling Dictionary discusses the orthographic rules and provides an extensive list which contains words in Ottoman letters alongside their new counterparts. The discussion revolves around the codification of the new alphabet. Rather than listing a fixed set of rules, it explains the motivation for capitalization and the use of the circumflex and apostrophe in Arabic and Persian loanwords. Capitalization follows the model of the contemporary French writing system.[9] This is illustrated by first names (Mehmet), family names (Ağaoğlu), place names (Ankara), nationalities (Türk ‘Turk’), institutions (Büyük Millet Meclisi ‘Grand National Assembly’), titles of books (Usul Hakkında Nutuk ‘Discourse on the Method’), and titles following personal names (İsmet Paşa ‘General İsmet’). The circumflex indicates the front consonants k [c], g [ɟ], l [l] before the back vowels [ɑ u] (kâr [cɑɾ] ‘profit’ vs. kar [kɑɾ] ‘snow’), vowel length (nâr [nɑːɾ] ‘fire’ vs. nar [nɑɾ] ‘pomegranate’), and the derivational nisba suffix -î (ilmî ‘scientific’) (see Steuerwald 1964: 10–21, 24–32). Apostrophe use is described in Section 4. The Spelling Dictionary was viewed as preliminary work for a future Turkish language academy. The second edition (İmlâ Kılavuzu) was published by the Turkish Language Association (Türk Dil Kurumu) in 1941. It contains orthographic rules and a word list in the new script only. The orthographic rules include capitalization, word-final devoicing, apostrophe, circumflex, and punctuation marks. Altogether, there have been twenty-seven editions of the Spelling Dictionary so far.

[j], which followed back and front vowels, respectively. In addition, we find the apostrophe (kesme işareti), the circumflex (uzatma işareti, düzeltme işareti), and the hyphen (bağlama çizgisi).[8] The Spelling Dictionary discusses the orthographic rules and provides an extensive list which contains words in Ottoman letters alongside their new counterparts. The discussion revolves around the codification of the new alphabet. Rather than listing a fixed set of rules, it explains the motivation for capitalization and the use of the circumflex and apostrophe in Arabic and Persian loanwords. Capitalization follows the model of the contemporary French writing system.[9] This is illustrated by first names (Mehmet), family names (Ağaoğlu), place names (Ankara), nationalities (Türk ‘Turk’), institutions (Büyük Millet Meclisi ‘Grand National Assembly’), titles of books (Usul Hakkında Nutuk ‘Discourse on the Method’), and titles following personal names (İsmet Paşa ‘General İsmet’). The circumflex indicates the front consonants k [c], g [ɟ], l [l] before the back vowels [ɑ u] (kâr [cɑɾ] ‘profit’ vs. kar [kɑɾ] ‘snow’), vowel length (nâr [nɑːɾ] ‘fire’ vs. nar [nɑɾ] ‘pomegranate’), and the derivational nisba suffix -î (ilmî ‘scientific’) (see Steuerwald 1964: 10–21, 24–32). Apostrophe use is described in Section 4. The Spelling Dictionary was viewed as preliminary work for a future Turkish language academy. The second edition (İmlâ Kılavuzu) was published by the Turkish Language Association (Türk Dil Kurumu) in 1941. It contains orthographic rules and a word list in the new script only. The orthographic rules include capitalization, word-final devoicing, apostrophe, circumflex, and punctuation marks. Altogether, there have been twenty-seven editions of the Spelling Dictionary so far.

The newspapers shifted to the new alphabet in the months leading up to 1 December 1928 when, according to the Alphabet Law, all newspapers had to be completely published in the new script. This was the case with Cumhuriyet, Hakimiyeti Milliye, Milliyet, Vakit, etc. Newspapers therefore played an important role during the alphabet revolution since they introduced the new letters and orthographic rules to their readers (see Acar 2011). This will be illustrated with Cumhuriyet and Hakimiyeti Milliye. Cumhuriyet presented the new alphabet (letters, numerals, apostrophe, circumflex, and hyphen) in the panel Benim Alfabem ‘My Alphabet’ on the front page of the issues from September 5 to September 21. Similarly, Hakimiyeti Milliye regularly provided sections on the new alphabet and thereby introduced the new spelling (letters, apostrophe, circumflex), with examples involving word formation (abbreviations, acronyms, compounding), inflection, and phonological processes (voicing assimilation, vowel harmony, word-final devoicing). Importantly, Hakimiyeti Milliye was a semi-official newspaper which largely followed the new orthographic rules. Moreover, its editor-in-chief, Falih Rıfkı Atay, was a member of the Language Commission. In contrast, these orthographic rules were not strictly followed by book publishers or by Istanbul-based newspapers such as Cumhuriyet (see Steuerwald 1963: 11–12; 1964: 8–9, 57, 108–109). This was not unusual in the 1930s and 1940s, which was criticized by the newspaper Ulus (Atay 1940; 1941).[10]

4 The apostrophe in Turkish

This section provides a diachronic account of the use of the apostrophe from the introduction of the new alphabet to the present. The focus will be on the alphabet and grammar of the Language Commission, orthographies and newspapers of that time, and selected editions of the Spelling Dictionary.

After the introduction of the new alphabet, the apostrophe (kesme işareti, koma işareti) was originally employed to transliterate the Arabic letters  (hamza) and

(hamza) and  (ayn), as in mes’ele ‘issue’ (< Ar.

(ayn), as in mes’ele ‘issue’ (< Ar.  ) and mes’ut ‘happy’ (< Ar.

) and mes’ut ‘happy’ (< Ar.  ) (see Steuerwald 1964: 22–23).[11] The letters

) (see Steuerwald 1964: 22–23).[11] The letters  and

and  represent the voiceless glottal stop [ʔ] and the voiced pharyngeal fricative [ʕ], respectively. The apostrophe was spoken as a glottal stop. In this respect, Lewis (1967: 8–9) distinguishes between primary glottal stop for hamza and secondary glottal stop for ayn. The use of the apostrophe as a phonographic marker can be gleaned from the alphabet and the grammar of the Language Commission as well as from contemporaneous orthographies and newspapers. The Language Commission presented the apostrophe in their alphabet (Yeni Türk alfabesi ‘New Turkish alphabet’) and grammar (Muhtasar Türkçe gramer ‘Concise Turkish grammar’). The alphabet only contains the examples mes’ud ‘happy’ and mebde’ ‘beginning’ (Dil Encümeni 1928c: 5). By contrast, the grammar explains that the apostrophe is employed for

represent the voiceless glottal stop [ʔ] and the voiced pharyngeal fricative [ʕ], respectively. The apostrophe was spoken as a glottal stop. In this respect, Lewis (1967: 8–9) distinguishes between primary glottal stop for hamza and secondary glottal stop for ayn. The use of the apostrophe as a phonographic marker can be gleaned from the alphabet and the grammar of the Language Commission as well as from contemporaneous orthographies and newspapers. The Language Commission presented the apostrophe in their alphabet (Yeni Türk alfabesi ‘New Turkish alphabet’) and grammar (Muhtasar Türkçe gramer ‘Concise Turkish grammar’). The alphabet only contains the examples mes’ud ‘happy’ and mebde’ ‘beginning’ (Dil Encümeni 1928c: 5). By contrast, the grammar explains that the apostrophe is employed for  (hamza) and

(hamza) and  (ayn).[12] It further illustrates the apostrophe with examples such as mes’ud ‘happy’ for ayn and mes’ul ‘responsible’ for hamza (Dil Encümeni 1928b: 9). This use is also reflected in orthographies and newspapers.[13] As for newspapers, Cumhuriyet deals with the apostrophe in both the new alphabet in the panel Benim Alfabem ‘My Alphabet’ (19/09/1928) and in the Ottoman script (30/09/1928). Similarly, Hakimiyeti Milliye describes the apostrophe in both the Ottoman script (06/09/1928, 21/09/1928) and the new alphabet (30/09/1928, 01/10/1928, 02/10/1928).

(ayn).[12] It further illustrates the apostrophe with examples such as mes’ud ‘happy’ for ayn and mes’ul ‘responsible’ for hamza (Dil Encümeni 1928b: 9). This use is also reflected in orthographies and newspapers.[13] As for newspapers, Cumhuriyet deals with the apostrophe in both the new alphabet in the panel Benim Alfabem ‘My Alphabet’ (19/09/1928) and in the Ottoman script (30/09/1928). Similarly, Hakimiyeti Milliye describes the apostrophe in both the Ottoman script (06/09/1928, 21/09/1928) and the new alphabet (30/09/1928, 01/10/1928, 02/10/1928).

The use of the apostrophe with inflected proper names was first put forward by Ata (1928) in the intellectual magazine Hayat following English usage, in particular.[14] In an article published in Hakimiyeti Milliye, Ata (1929) criticizes that in some newspapers and magazines inflected proper names are highlighted by means of italics (Baconun ‘of Bacon’) or quotation marks followed by a blank space (“Bacon„un ‘of Bacon’).[15] Instead, he suggests that the apostrophe be applied to all proper name classes, including personal names (Ahmet’in ‘of Ahmet’), personal names with titles (Mehmet Bey’e ‘to Mr. Mehmet’), and institution names (Büyük Millet Meclisi’nin ‘of the Great National Assembly’). He further argues that in inflected foreign names the morpheme boundaries are not always straightforward.[16] Ata’s proposal was supported by Atay, editor-in-chief of Hakimiyeti Milliye. As a result, the apostrophe was employed with inflected proper names in Hakimiyeti Milliye from 1929 onwards.[17]

Let us move on to the use of the apostrophe in the Spelling Dictionary. We will focus on the first five editions (1928–1957) and the most recent edition (2012) (see Table 5).[18] According to the first edition (İmlâ Lûgati), the apostrophe is employed for the transliteration of hamza and ayn in word-medial position after a consonant (san’at ‘art’) and, albeit less frequently, after a vowel (şe’niyet ‘reality’) (Dil Encümeni 1928a: xii–xiii). Interestingly, the first edition presents one instance of inflected foreign name with an apostrophe: Descartes’ın ‘of Descartes’ (p. xxviii).

Use of the apostrophe according to selected editions of the Spelling Dictionary.

| İmlâ Lûgati (11928: xii) |

İmlâ Kılavuzu (21941: xxxiv, 31948: xxxiv) |

İmlâ Kılavuzu (41956: 21, 51957: 21) |

Yazım Kılavuzu (272012: 38–39) |

and and  |

|||

| Inflected proper names | |||

| Segment deletion | |||

| Homophony avoidance | |||

| Inflected numerals | |||

| Inflected abbreviations, dates, letters, etc. | |||

The second edition (İmlâ Kılavuzu) included two new uses of the apostrophe (Türk Dil Kurumu 1941: xxxiii–xxxv). First, the apostrophe is compulsory with segment deletion (ne ola > n’ola ‘what happens’). Second, the apostrophe is optional with inflected proper names, as shown in (1). Note that the proper name class is not specified. However, the introduction contains examples of the apostrophe with the inflected names of persons (Tasar’ın ‘of Tasar’), institutions (Türk Dil Kurumu’nun ‘of the Turkish Language Association’) and books (İmlâ Lûgati’nin ‘of the Spelling Dictionary’). In addition, the spelling of word-final <p t k ç> is preserved when vowel-initial suffixes are attached despite the pronunciation being [b d ɡ dʒ], as in Ahmet’i [ɑhmɛdi] (see Table 2 for examples). The third edition does not differ from the second one with respect to the functions of the apostrophe.

Apostrophe with inflected proper names (Türk Dil Kurumu 1941: xxxiii)

Özel adlar, kendilerinden sonra gelen eklerden bir (’) işaretiyle ayrılabilir [Proper names can be separated from inflectional endings by (’)]

The fourth edition added two new uses of the apostrophe. First, the apostrophe can be employed when inflection leads to homophony with monomorphemic words. For example, karın [kɑɾɯn] ‘belly’ is homophonous with the inflected forms kar’ın ‘of snow’ and karı’n ‘your wife’ (examples taken from Lewis 1967: 2). Thus, the apostrophe separates the base form from the inflectional ending, thereby highlighting morpheme boundaries. Second, the apostrophe can be used to separate numerals from inflectional endings (1956’da ‘in 1956’). The fifth edition does not differ from the fourth one with respect to the functions of the apostrophe.

According to the latest edition (Yazım Kılavuzu), the apostrophe is employed for separating the inflectional endings of proper names (Atatürk’üm ‘my Atatürk’), titles (Ayşe Hanım’dan ‘from Ms. Ayşe’), abbreviations and acronyms (TDK’nin ‘of the TDK’), numerals (1985’te ‘in 1985’), names of days and months in specific dates (12 Temmuz 2010 Pazartesi’nin ‘of Monday 12 July 2010’), and letters, suffixes, or words in metalinguistic use (a’dan z’ye ‘from a to z’, -lık’la ‘with -lık’) (Türk Dil Kurumu 2012: 38–40).[19] The inflectional endings include case, comitative (-(y)lA), copula (-DIr, -mIş, -(y)-sA), and possessive. In addition, the apostrophe is employed to mark the deletion of one or more segments (ne’n var? < neyin var? ‘what have you got?’).[20] With regard to inflected proper names, there are some exceptions. First, inflected names of committees, conferences, institutions, organizations, sessions, and workplaces are not separated by the apostrophe (Türk Dil Kurumundan ‘from the Turkish Language Association’). In this respect, institution names differ from other object name subclasses such as book names as well as from other proper name classes such as personal names and place names (see Section 5.3 for discussion). Second, personal names followed by the plural suffix -lAr (-lar, -ler) do not occur with the apostrophe (Ahmetler).[21] A possible explanation is that proper names lose their onymic status when they are pluralized (Nübling et al. 2015: 35). Third, ethnonyms, which are formed by combining a place name (Ankara) with the derivational suffix -lI (-li, -lı, -lu, -lü), lack the apostrophe both before and after the derivational suffix, as in Ankaralı ‘inhabitant of Ankara’ and Ankaralının ‘of the inhabitant of Ankara’, respectively (see Göksel and Kerslake 2011: 324–325 for examples). The absence of the apostrophe in these cases is in accordance with the view that ethnonyms do not constitute proper names (Nübling et al. 2015: 36). However, Karabacak (1999: 602) reports that the apostrophe can be applied to proper names where the pronunciation differs from the spelling (Bordeaux’lu ‘inhabitant of Bordeaux’).[22]

In summary, the use of the apostrophe with proper names was first put forward by Ata (1928; 1929) shortly after the alphabet revolution took place. However, this practice was not reflected in the orthographic rules until the second edition (1941) although it is found in Hakimiyeti Milliye from 1929. With regard to the Spelling Dictionary, we found the following changes: (1) the transliteration of hamza and ayn is present in the first five editions. However, the instances of apostrophe slightly decrease in the word list.[23] In the most recent edition, the apostrophe is absent from Arabic and Persian loanwords, as in kati ‘sure’, mesul ‘responsible’, and sanat ‘art’ (Türk Dil Kurumu 2012: 331, 388, 460); (2) the use of the apostrophe for segment deletion and inflected proper names is introduced in the second edition and has continued to apply until the present day. Regarding inflected proper names, the apostrophe is optional in the second to fifth editions, but obligatory in the most recent one; (3) homophony avoidance by means of apostrophe is present in the fourth and fifth editions, but no longer in the most recent one; (4) the occurrence of the apostrophe with inflected numerals is introduced in the fourth edition and is still present; and (5) in the most recent edition, apostrophe use is extended to abbreviations, acronyms, dates, inflected letters, suffixes, and words in metalinguistic use.

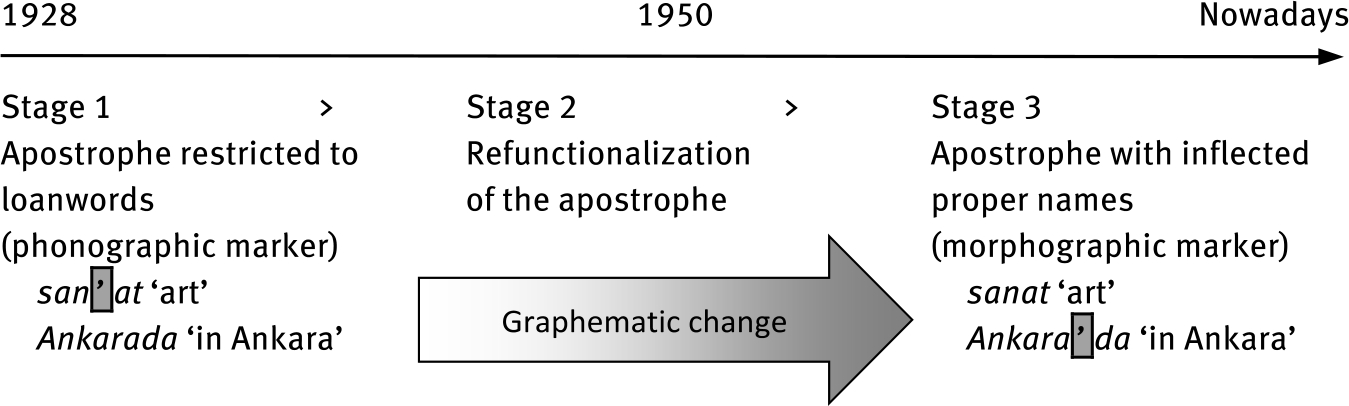

This diachronic overview has shed light on a previously undocumented graphematic change involving the refunctionalization of the apostrophe, as illustrated in Figure 1. At a first stage, the apostrophe constitutes a phonographic marker for the transliteration of hamza and ayn in Arabic and Persian loanwords (san’at ‘art’). At a second stage, the apostrophe is gradually refunctionalized as a morphographic marker in proper names (Ankara’da ‘in Ankara’). At a final stage, the apostrophe is absent from Arabic and Persian loanwords (san’at > sanat ‘art’) and is mainly associated with inflected proper names. The absence of the apostrophe with Arabic and Persian loanwords reflects the loss of the glottal stop in spoken Turkish. After vowels, glottal stop deletion can be accompanied by compensatory vowel lengthening. This is the case with tesir [tɛːsiɾ] ‘effect’ and malum [maːlum] ‘known’, which originally contained hamza (Ar.  ) and ayn (Ar.

) and ayn (Ar.  ), respectively (Steuerwald 1964: 117, 120; Lewis 1967: 14). The glottal stop still occured in the 1960s with old-fashioned words such as kur’a ‘prize draw’ (Steuerwald 1964: 23, 122–123). Today, it is mainly found among older speakers (Kornfilt 1997: 488–489). In addition, we see that the pragmatic-morphological principle (for inflected proper names) is followed by the graphematic-morphological principle (for inflected abbreviations, acronyms, and numerals).[24]

), respectively (Steuerwald 1964: 117, 120; Lewis 1967: 14). The glottal stop still occured in the 1960s with old-fashioned words such as kur’a ‘prize draw’ (Steuerwald 1964: 23, 122–123). Today, it is mainly found among older speakers (Kornfilt 1997: 488–489). In addition, we see that the pragmatic-morphological principle (for inflected proper names) is followed by the graphematic-morphological principle (for inflected abbreviations, acronyms, and numerals).[24]

Diachronic development of the apostrophe.

5 The apostrophe in Cumhuriyet (1929–1975)

As we have seen in the previous section, Turkish exhibits a graphematic change involving a refunctionalization of the apostrophe. However, little is known about the refunctionalization patterns in the intermediate stage where the apostrophe occurred both as a phonographic marker with Arabic and Persian loanwords and as a morphographic marker in inflected proper names (see Figure 1). Moreover, the use of the apostrophe with inflected proper names was introduced in the second edition (1941) of the Spelling Dictionary. Importantly, the apostrophe was optional rather than compulsory. The optionality of this rule is well suited for a variationist analysis. In this section, we will conduct a corpus analysis in order to examine the loss of the apostrophe with Arabic and Persian loanwords on the one hand and the factors that motivated the refunctionalization of the apostrophe on the other. This issue will be illustrated by the newspaper Cumhuriyet.[25] This newspaper was chosen for the following reasons: First, Cumhuriyet is a daily national newspaper which was grounded in 1924 and is still published today. This allows for an in-depth diachronic study of the apostrophe from 1929 onwards. Second, recall from Section 3 that in contrast to the semi-official newspaper Hakimiyeti Milliye, book publishers and Istanbul-based newspapers such as Cumhuriyet did not strictly follow the orthographic rules. For example, Hakimiyeti Milliye employed the apostrophe with inflected proper names as early as 1929 (see Footnote 17 for examples). However, it will be shown that Cumhuriyet also employed it, albeit at a later point and under specific conditions. In this section, we will address the following questions:

What are the distribution patterns of the apostrophe with Arabic and Persian loanwords and inflected proper names?

Which factors condition the occurrence of the apostrophe with inflected proper names?

5.1 Study design

We selected twenty-two issues published between 1929 and 1975. This time span begins directly after the introduction of the Latin alphabet and ends with the regular use of the apostrophe with inflected proper names. We analysed the front pages of two issues per year with five-year intervals (1929, 1930, 1935, etc.).[26] To examine the distribution of the apostrophe with Arabic and Persian loanwords and inflected proper names, we coded all instances of apostrophe. Further, in order to address the question of which factors trigger the occurrence of the apostrophe with proper names, we considered all instances of inflected proper names both with and without apostrophe. Following previous diachronic studies on German which demonstrated that the apostrophe is motivated by foreignness and animacy (see Section 1), we will test the following hypotheses: First, if the apostrophe is triggered by foreignness, we expect it to occur with foreign names prior to native names (regardless of animacy). Second, if the apostrophe is triggered by animacy, we expect it to occur with human names (personal names) prior to inanimate names (place names, object names, etc.). Our hypotheses are summarized in (2).

Hypotheses for the apostrophe with inflected proper names

H1 (Foreignness): The apostrophe occurs with foreign names prior to native names

H2 (Animacy): The apostrophe occurs with personal names prior to other proper name classes

The tokens were lemmatized according to the Turkish Dictionary (Türk Dil Kurumu 1988) and subsequently annotated for word class, proper name class, presence of apostrophe, overlap of the apostrophe with a morpheme boundary, morphological ending (case, copula, derivation, possession, etc.), and foreignness (native vs. foreign). With regard to word class, we distinguished between common noun, numeral, and proper name. Since the apostrophe with common nouns is associated with loanwords, we specified the etymology (Arabic, French, Greek, Persian). With regard to proper name class, we followed the classification of proper names put forward by Nübling et al. (2015: 99–104), thereby differentiating between personal names, place names, object names, event names, and weather names. Object names were subclassified as names of institutions, means of transport, etc. (see Vasil’eva 2004: 617 for a classification of institution names).

Foreignness was determined only for personal names and place names. Personal names were classified as native if they were of Turkish origin (Atatürk, İnönü), but as foreign if they originated from other languages such as English (Churchill, Eden), French (de Gaulle, Molière), German (Rommel, von Ribbentrop), etc. Place names were classified as native if they belonged to the Turkish vocabulary. This holds not only for place names from Turkey (Türkiye ‘Turkey’, Ankara ‘Ankara’), but also for place names from abroad (İngiltere ‘England’, Londra ‘London’). Note that native place names from abroad are integrated into the Turkish graphematic and phonological system (Varşova < Warszawa ‘Warsaw’). By contrast, place names were classified as foreign if they exhibited a low degree of familiarity and linguistic integration in terms of graphematics and phonology (see Nowak and Nübling 2017 and Zimmer 2018: 137–176 for German). The degree of familiarity of the place name correlates with the conceptual distance between the speaker (or reader in the case of newspapers) and the named object (see Zimmer 2018: 141). Graphematic deviations include letters which are absent from the Turkish alphabet (<w> in Washington), letters which despite being present in the Turkish alphabet have a different pronunciation (<y> for [i] in Vichy, <z> for [ts] in Salzburg), and violations of the one-to-one correspondences between letters and sounds. This is the case with letters that are not spoken (<g> in Washington), letters that have the same pronunciation (<i> and <y> for [i] in Vichy), and combinations of letters for a single sound (<sh> in Washington). Phonological deviations include violations of phonotactics (<str> and <g> in Strasburg) as well as sounds that do not belong to the phoneme inventory (<z> for [ts] in Salzburg). Examples of foreign place names are given in Table 6. For instance, Luzon (Philippine island) is in line with Turkish graphematics and phonology. However, its degree of familiarity is rather low. Vichy (French city) is in accordance with Turkish phonology. However, it contains the letter <y>, which in Turkish is employed for the onglide [j], and further violates the one-to-one correspondence principle (<ch> for [ʃ], <i> and <y> for [i]). In addition, its degree of familiarity is rather low. Washington exhibits graphematic and phonological deviations. However, its degree of familiarity is rather high. Salzburg does not obey Turkish graphematics (<z> represents [z] in Turkish) and phonology (<g> for [k], <z> for [ts]) and further exhibits a low degree of familiarity. Interestingly, the low degree of linguistic integration and familiarity is associated with the apostrophe, as in Luzon’a ‘to Luzon’ (01/02/1945), Vichy’den ‘from Vichy’ (31/07/1940), Washington’da ‘in Washington’ (31/07/1945), and Salzburg’da ‘in Salzburg’ (31/07/1940). Moreover, of the 31 foreign place names found in our study, 25 occur with the apostrophe.

Features of foreign place names.

| Example | Graphematics | Phonology | Familiarity |

| Luzon | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Vichy | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Washington | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ |

| Salzburg | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

Finally, we excluded the following cases: 1) inflected proper names separated by quotation marks («Cumhuriyet»in ‘of Cumhuriyet’ 31/01/1930) or a blank space (CKMP nin ‘of the CKMP’ 31/07/1965), of which we found 5 and 15 tokens, respectively. This implies that this practice is infrequent as compared to the apostrophe (see Section 5.2); 2) uninflected proper names with apostrophe (6 tokens). This is the case with names of Arabic origin such as Kur’an ‘Quran’ (31/01/1970) and Mes’ul (31/01/1929); and 3) names of months (7 tokens). This is the case with Mayısta ‘in May’ (31/07/1960) and Ramazanın ‘of Ramadan’ (31/01/1930). Following Nübling (2004: 836–837), names of months are not considered proper names.

5.2 Results

This section is structured as follows: First, we will provide an overview of the tokens obtained from the corpus analysis. Second, we will present the distribution of the apostrophe with Arabic and Persian loanwords and inflected proper names. Third, we will examine the influence that foreignness and animacy have on the occurrence of the apostrophe with inflected personal names and place names. Finally, we will analyse the apostrophe with object names and event names.

We found a total of 1,252 tokens, of which 547 contain the apostrophe while 705 do not. These tokens are arranged in Table 7 according to word class, proper name class, and foreignness. Arabic and Persian loanwords are comprised of uninflected and inflected forms (san’at ‘art’, san’atı ‘art (acc.)’, both from 31/01/1929). The apostrophe is restricted to word-medial position such that the apostrophe never coincides with a morpheme boundary. Note that the absence of the apostrophe with Arabic and Persian loanwords, numerals, and inflected French and Greek loanwords was not considered. With regard to inflected proper names, we can observe a gradual decrease in the use of the apostrophe according to proper name class: personal names (68 %), place names (34 %), object names (32 %), and event names (13 %). Inflected weather names are not attested. With regard to foreignness, the apostrophe is more frequently attested with foreign names than with native names (82 % vs. 37 %).

Apostrophe according to word class, inflected proper name class, and foreignness.

| Category | N | With apostrophe | Without apostrophe |

| Word class | |||

| Arabic and Persian loanwords | 53 | 53 | n/a |

| Inflected proper names | 1,182 | 477 (40 %) | 705 (60 %) |

| Inflected numerals | 12 | 12 | n/a |

| Inflected loanwords (French, Greek) | 4 | 4 | n/a |

| Inflected proper names | |||

| Personal names | 247 | 169 (68 %) | 78 (32 %) |

| Place names | 698 | 238 (34 %) | 460 (66 %) |

| Object names | 205 | 66 (32 %) | 139 (68 %) |

| Event names | 32 | 4 (13 %) | 28 (87 %) |

| Foreignness (personal names, place names) | |||

| Native | 818 | 303 (37 %) | 515 (63 %) |

| Foreign | 122 | 100 (82 %) | 22 (18 %) |

Figure 2 documents the refunctionalization of the apostrophe from a phonographic marker of glottal stop in Arabic and Persian loanwords to a morphographic marker of morpheme boundaries in proper names. The use of the apostrophe with Arabic and Persian loanwords is widely attested in 1929. From 1930 to 1955, it drastically decreases. After 1960, the phonographic marker disappears. Examples of Arabic and Persian loanwords with a frequency of ≥ 5 are kat’i ‘sure’, mes’ele ‘issue’, and san’at ‘art’ (with 8, 15, and 6 tokens, respectively). The use of the apostrophe with inflected proper names undergoes profound changes from 1929 to 1935: it abruptly increases in 1930 and is abandoned in 1935. The 56 tokens of inflected proper names with apostrophe are comprised of 1 foreign personal name (Makdonald’ın ‘of MacDonald’ 31/01/1930) and 55 native place names (İstanbul’un ‘of Istanbul’ 31/01/1930). This finding runs counter to the idea that the apostrophe is triggered by animacy. For the period between 1940 and 1955, we can observe that the apostrophe gradually establishes itself as a morphographic marker. In addition, the apostrophe also occurs with inflected numerals (12 tokens) and inflected French and Greek loanwords (4 tokens).[27] In this respect, loanwords behave as proper names (see Ackermann and Zimmer 2017 and Zimmer 2018: 221–252 for German).

Apostrophe with Arabic and Persian loanwords and inflected proper names.

To study the role of foreignness and animacy, we concentrated on personal names and place names (see Section 5.3 for further proper name classes). We excluded the years 1929 to 1935 for two reasons. First, the apostrophe does not occur with inflected proper names in 1929 and 1935 (see Figure 2). Second, the apostrophe is mostly restricted to native place names in 1930. Figure 3 shows the distribution of the apostrophe with foreign personal names and place names from 1940 to 1975. Notwithstanding the low frequency of foreign names (especially in 1955 and 1970), the overall picture reveals that foreignness strongly correlates with apostrophe usage. Moreover, the occurrence of the apostrophe with foreign names is not sensitive to animacy since it is found both with personal names (Mihailoviç’in ‘of Mihailoviç’ 31/07/1940) and place names (Versailles’dan ‘from Versailles’ 31/07/1940).

Apostrophe with inflected foreign personal names and place names.

Apostrophe with inflected native personal names and place names.

Figure 4 depicts the distribution of the apostrophe with native personal names and place names in the period from 1940 to 1975. Between 1940 and 1955, the apostrophe with native names is rare. Note that the frequency of personal names in 1940 and 1945 is low (only 6 tokens) and does not allow us to observe an impact of animacy. However, animacy has a clear effect in 1960 and 1965 where the apostrophe occurs more frequently with native personal names than with native place names (91 % vs. 46 % and 74 % vs. 33 %, respectively). In 1970 and 1975, the use of the apostrophe with both native personal names and native place names is regular.

We fit a mixed-effects logistic regression model with the response variable “apostrophe” and the predictor variables “proper name class” (place name vs. personal name), “foreignness” (native vs. foreign), and “year”.[28] The model coefficients are given in Table 8, showing that all three predictor values had a highly significant effect.

Coefficients of the mixed-effects regression model.

| Estimate | Std. Error | z value | Pr(>|z|) | |

| (Intercept) | −1.6 | 0.28 | −5.7 | 9.4E-09*** |

| PN_Class_PersN | 1.52 | 0.42 | 3.59 | 0.00033*** |

| Foreignness_Foreign | 3.66 | 0.57 | 6.42 | 1.3E-10*** |

| Year | 1.71 | 0.17 | 10.2 | 1.9E-24*** |

We now turn to the hypotheses postulated in (2). The corpus analysis provides evidence that foreignness triggers the use of the apostrophe with personal names and place names regardless of animacy, thereby confirming Hypothesis 1. On the other hand, animacy motivated the use of the apostrophe with native names in 1960 and 1965 since the apostrophe occurs more frequently with personal names than with place names. Thus, Hypothesis 2 is only partly borne out. This is discussed in more detail in Section 5.3.

Let us move on to object names and event names. With regard to object names, we found a total of 205 tokens, which were subclassified as names of books, institutions, languages, newspapers, songs, and means of transport. The subcategory of institution names is overrepresented with 195 tokens, of which 60 contain an apostrophe (Senato’dan ‘from the Senate’ 31/07/1970) while 135 do not (Dışişleri Bakanlığına ‘to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ 31/01/1975). Interestingly, 35 of 60 cases constitute abbreviations and acronyms, which are first attested from 1960 onwards (CHP’nin ‘of the CHP’ 31/07/1965). With regard to event names, we found a total of 32 tokens, of which only 4 exhibit the apostrophe (İnebahtı’da ‘at [the battle of] Lepanto’ 31/01/1965) while 28 lack it (Londra konferansında ‘at the London Conference’ 31/08/1955). In summary, object names and event names are characterized by the absence of the apostrophe. An explanation is that these proper name classes usually contain non-onymic material (see Nübling et al. 2015: 269–270, 320–322). This is the case with havayolu ‘airline’ in İran havayollarını ‘Iran Airlines (acc.)’ (31/01/1975). In this respect, object names and event names do not constitute prototypical proper names as opposed to personal names and place names.

The findings can be summarized as follows: First, the loss of the apostrophe as a phonographic marker of glottal stop in Arabic and Persian loanwords was complete by 1960. Second, the refunctionalization of the apostrophe from a phonographic marker to a morphographic marker of morpheme boundaries in proper names took place between 1940 and 1955. Third, this refunctionalization began with foreign names in 1940. Later, it expanded to native names in 1960 and 1965. Importantly, the apostrophe is more frequently found with personal names than with place names. Fourth, the apostrophe regularly occurs with inflected personal names and place names from 1970 onwards. Finally, object names and event names rarely exhibit the apostrophe.

5.3 Discussion

The discussion will revolve around foreignness and the influence of the Spelling Dictionary on apostrophe usage. Foreignness has been shown to have an impact on morphosyntactic phenomena. This is the case with spatial relations in French and Latin (Adams 2013: 328–329; Stolz et al. 2017: 137–140), genitive constructions with place names in German (Nübling 2012; Nowak and Nübling 2017; Zimmer 2018), and the definite article with place names in Romance languages (Caro Reina 2020). In addition, foreignness motivates the use of syngraphemes. As we saw in Section 2, loanwords and foreign place names are separated from inflectional endings with the apostrophe in Finnish (show’t ‘the shows’, Bordeaux’ssa ‘in Bordeaux’), and with the hyphen in Romanian (show-ul ‘the show’, Bordeaux-ul ‘Bordeaux’) (see Bunčić 2004: 189 for Polish and Russian). Similarly, foreign personal names and place names are separated from inflectional endings by means of the apostrophe in Cumhuriyet. More specifically, foreignness initiates the use of the apostrophe with inflected personal names and place names from 1940 onwards (see Figure 3). This raises the following questions:

Why do foreign names attract the use of the apostrophe?

Why did this practice begin in 1940?

What is the effect of foreignness on other proper name classes such as object names and event names?

As shown in Section 4, the Spelling Dictionary gradually increases the number of functions of the apostrophe. We will now compare the Spelling Dictionary and the Cumhuriyet newspaper with respect to the apostrophe with inflected proper names in order to address the question of whether the rules of the Spelling Dictionary have an influence on the use of the apostrophe in Cumhuriyet. The Spelling Dictionary includes the optional use of the apostrophe with inflected proper names in the second edition (1941). However, this use is first attested with native place names and foreign personal names in 1930 (İtalya’nın ‘of Italy’, Makdonald’ın ‘of MacDonald’, both from 31/01/1930) (see also Figure 2). This implies that the Spelling Dictionary features pre-existent practices rather than introducing new ones. Similar observations have been made for graphematic changes such as sentence-internal capitalization in Early New High German (Bergmann 1999: 73–75).

6 Conclusions

Turkish exhibits graphematic dissociations between common nouns and proper names (İzmir’de ‘in İzmir’ vs. şehirde ‘in the city’). These dissociations originated from a graphematic change involving the refunctionalization of the apostrophe from a phonographic marker of glottal stop in Arabic and Persian loanwords to a morphographic marker of morpheme boundaries in proper names. This paper studied the emergence and development of the apostrophe from the Turkish alphabet revolution (1928) to the present. The use of the apostrophe was examined in the different editions of the Spelling Dictionary published by the Language Commission (Dil Encümeni) and the Turkish Language Association (Türk Dil Kurumu) as well as in early issues of the newspapers Hakimiyeti Milliye and Cumhuriyet. The apostrophe was originally employed as a phonographic marker for transliterating  (hamza) and

(hamza) and  (ayn) in Arabic and Persian loanwords (san’at ‘art’). The use of the apostrophe as morphographic marker in proper names was first proposed by Ata in 1928 and was practiced by Hakimiyeti Milliye from 1929 onwards. However, the Spelling Dictionary did not include this use until the second edition in 1941. In this respect, the Spelling Dictionary did not have a direct influence on apostrophe usage.

(ayn) in Arabic and Persian loanwords (san’at ‘art’). The use of the apostrophe as morphographic marker in proper names was first proposed by Ata in 1928 and was practiced by Hakimiyeti Milliye from 1929 onwards. However, the Spelling Dictionary did not include this use until the second edition in 1941. In this respect, the Spelling Dictionary did not have a direct influence on apostrophe usage.

To illustrate this graphematic change, we conducted a diachronic corpus analysis based on selected issues of the newspaper Cumhuriyet from 1929–1975. The main findings can be summarized as follows: The loss of the apostrophe as a phonographic marker in Arabic and Persian loanwords is complete by 1960 (san’at > sanat ‘art’). This development is in line with the loss of the glottal stop in spoken Turkish. With regard to inflected proper names, we observed that the refunctionalization of the apostrophe as a morphographic marker is triggered by foreignness and later by animacy with native names. More specifically, foreign personal names and place names occur with the apostrophe from 1940 onwards while native personal names and place names do not occur with the apostrophe until 1960 and 1965. The use of the apostrophe with native names is sensitive to animacy since we find the apostrophe more frequently with personal names than with place names. Finally, refunctionalization is accomplished by 1970, after which the apostrophe regularly applies to inflected foreign and native names.

As a result of this graphematic change, the apostrophe functions as a morphographic marker for highlighting morpheme boundaries primarily in inflected proper names, but also in inflected abbreviations, acronyms, dates, and numerals. In this respect, the pragmatic-morphological principle is followed by the graphematic-morphological principle. In addition, the apostrophe is employed, albeit less frequently, as a deletion marker (see Footnote 20 for examples). However, there is an overlap of both functions since deletion occurs at morpheme boundaries. The different functions of the apostrophe in 1928 Turkish and in modern Turkish are summarized in Table 9.

Functions of the apostrophe in Turkish.

| Diacritic marker | Deletion marker | Phonographic marker | Morphographic marker | |

| 1928 Turkish | ✓ | |||

| Modern Turkish | (✓) | ✓ |

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Hüseyin Erdem for transliterations from Ottoman, Stefan Hartmann for the statistical analysis, and Béatrice Hendrich, Diego Romero Heredero, and the editors of the volume for helpful comments on a previous version of this paper.

References

Académie Française. 1879. Dictionnaire de l’Académie Française. 2 vol. 7th edn. Paris: Firmin-Didot.Search in Google Scholar

Acar, Ayla. 2011. Türkiye’de latin alfabesine geçiş süreci ve gazeteler [The transition period to the Latin alphabet and newspapers in Turkey]. İstanbul Üniversitesi İletişim Fakültesi Hakemli Dergisi 41. 5–25.Search in Google Scholar

Ackermann, Tanja & Christian Zimmer. 2017. Morphologische Schemakonstanz – eine empirische Untersuchung zum funktionalen Vorteil nominalmorphologischer Wortschonung im Deutschen. In Nanna Fuhrhop, Renata Szczepaniak & Karsten Schmidt (eds.), Sichtbare und hörbare Morphologie (Linguistische Arbeiten 565), 145–176. Berlin & Boston: De Gruyter.10.1515/9783110528978-006Search in Google Scholar

Adams, James N. 2013. Social variation and the Latin language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511843433Search in Google Scholar

Ata, Nurullah. 1928. Ariel yahut Shelley’nin hayatı [Ariel or the Life of Shelley]. Hayat 99. 422–423.Search in Google Scholar

Ata, Nurullah. 1929. İsmi hasler [Proper names]. Hakimiyeti Milliye 25(May). 1.Search in Google Scholar

Atay, Falih Rıfkı. 1940. İmlâ lûgatine dair [On the Spelling Dictionary]. Ulus 29(November). 2.Search in Google Scholar

Atay, Falih Rıfkı. 1941. İmlâya dair düşünceler [Thougths on spelling]. Ulus 9(October). 2.Search in Google Scholar

Bankhardt, Christina. 2010. Tütel, Tüpflein, Oberbeistrichlein. Der Apostroph im Deutschen. Mannheim: Institut für Deutsche Sprache.Search in Google Scholar

Barton, Kamil. 2017. MuMIn: Multi-Model Inference. R package version 1.40.0 [Computer software].Search in Google Scholar

Bates, Douglas, Martin Mächler, Ben Bolker & Steve Walker. 2015. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software 67(1). 1–81.10.18637/jss.v067.i01Search in Google Scholar

Bayraktarlı, İhsan Yılmaz. 2009. Die Türkei im Umbruch. Schrift und Sprache als nationalistisches Politikum in der türkischen Revolution. Frankfurt am Main: Maurer.Search in Google Scholar

Bergmann, Rolf. 1999. Zur Herausbildung der deutschen Substantivgroßschreibung. In Walter Hoffmann, Jürgen Macha, Klaus J. Mattheier, Hans-Joachim Solms & Klaus-Peter Wegera (eds.), Das Frühneuhochdeutsche als sprachgeschichtliche Epoche, 59–79. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.Search in Google Scholar

Biçici, Mehmet & Zeynep Yıldız Özlü. 2020. Harf inkılâbı üzerine Türkiye Büyük Millet Meclisi’nde çıkan tartışmalar ve karşıt görüşler [Debates and opposing views in the Turkish Grand National Assembly on the letter revolution]. Tarih ve Gelecek Dergisi 6(1). 180–197.10.21551/jhf.681313Search in Google Scholar

Bunčić, Daniel. 2004. The apostrophe: A neglected and misunderstood reading aid. Written Language & Literacy 7(2). 85–204.10.1075/wll.7.2.04bunSearch in Google Scholar

Caro Reina, Javier. 2020. The definite article with place names in Romance languages. In Nataliya Levkovych & Julia Nintemann (eds.), Aspects of the grammar of names: Empirical case studies and theoretical topics, 25–51. München: LINCOM.10.1515/9783110672626-003Search in Google Scholar

Caymaz, Birol & Emmanuel Szurek. 2007. La révolution au pied de la lettre. L’invention de «l’alphabet turc». European Journal of Turkish Studies, Thematic Issue 6.10.4000/ejts.1363Search in Google Scholar

Doğaner, Yasemin. 2005. Elifba’dan Alfabeye: Yeni Türk Harfleri. Modern Türklük Araştırmaları Dergisi 2(4). 27–44.Search in Google Scholar

DOOM = Academia Română (ed.). 2005. Dicţionarul ortografic, ortoepic și morfologic al limbii române [The orthographic, orthoepic and morphological dictionary of the Romanian language]. 2nd edn. București: Editura Academiei Române.Search in Google Scholar

Dum-Tragut, Jasime. 2009. Armenian: Modern Eastern Armenian. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/loall.14Search in Google Scholar

Elbert, Samuel H. & Mary Kawena Pukui. 1979. Hawaiian grammar. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii Press.10.1515/9780824840792Search in Google Scholar

Encümeni, Dil (ed.). 1928a. İmlâ Lûgati [Spelling dictionary]. İstanbul: Devlet Matbaası.Search in Google Scholar

Encümeni, Dil (ed.). 1928b. Muhtasar Türkçe gramer [Concise Turkish grammar]. İstanbul: Devlet Matbaası.Search in Google Scholar

Encümeni, Dil (ed.). 1928c. Yeni Türk alfabesi. İmlâ ve tasrif şekilleri [New Turkish alphabet. Spelling and inflectional forms]. İstanbul: Devlet Matbaası.Search in Google Scholar

Erturk, Nergis. 2011. Grammatology and literary modernity in Turkey. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199746682.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Finbow, Thomas. 2016. Writing systems. In Adam Ledgeway & Martin Maiden (eds.), The Oxford guide to the Romance languages, 681–693. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199677108.003.0041Search in Google Scholar

Gallmann, Peter. 1985. Graphische Elemente der geschriebenen Sprache. Grundlagen für eine Reform der Orthographie. Tübingen: Niemeyer.10.1515/9783111630380Search in Google Scholar

Gallmann, Peter. 1989. Syngrapheme an und in Wortformen. Bindestrich und Apostroph im Deutschen. In Peter Eisenberg & Hartmut Günther (eds.), Schriftsystem und Orthographie (Reihe Germanistische Linguistik 97), 85–110. Tübingen: Niemeyer.10.1515/9783111372266.85Search in Google Scholar

Gallmann, Peter. 1996. Interpunktion (Syngrapheme). In Hartmut Günther & Otto Ludwig (eds.), Schrift und Schriftlichkeit / Writing and its use, 2. Halbband / Volume 2 (Handbücher zur Sprach- und Kommunikationswissenschaft / Handbooks of Linguistics and Communication Science 10/2), 1456–1467. Berlin & New York: De Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9783110147445.2.9.1456Search in Google Scholar

Göksel, Aslı & Celia Kerslake. 2011. Turkish: An essential grammar. New York: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Grevisse, Maurice & André Goosse. 2016. Le bon usage: Langue française. 16th edn. Bruxelles: De Boeck Supérieur.Search in Google Scholar

Hill, Jane H. 2005. A grammar of Cupeño. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.Search in Google Scholar

Hilmi, Ibrahîm. 1928. Yeni harflerle resimli türkçe alfabe [The Turkish alphabet illustrated with new letters]. İstanbul: Hilmi Kitaphânesi.Search in Google Scholar

Holton, David, Peter Mackridge & Irene Philippaki-Warburton. 2012. Greek: A comprehensive grammar. 2nd edn. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9780203802380Search in Google Scholar

IEC = Institut d’Estudis Catalans (ed.). 2017. Ortografia catalana [Catalan orthography]. Barcelona: Institut d’Estudis Catalans.Search in Google Scholar

Karabacak, Esra. 1999. Kesme işareti [The apostrophe]. In Türk Dil Kurumu (ed.), 3. Uluslararası Türk Dil Kurultayı (1996), 601–603. Ankara: Türk Dil Kurumu Yayınları.Search in Google Scholar

Károly, László. 2012. History of the intervocalic velars in the Turkic languages. Turkic Languages 16(1). 3–24.Search in Google Scholar

Kempf, Luise. 2019. Die Evolution des Apostrophgebrauchs. Eine korpuslinguistische Untersuchung. Jahrbuch für Germanistische Sprachgeschichte 10. 119–150.10.1515/jbgsg-2019-0009Search in Google Scholar

Klein, Wolf Peter. 2002. Der Apostroph in der deutschen Gegenwartssprache: Logographische Gebrauchserweiterungen auf phonographischer Basis. Zeitschrift für Germanistische Linguistik 30(2). 169–197.10.1515/zfgl.2002.014Search in Google Scholar

Kornfilt, Jaklin. 1997. Turkish. New York: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Korpela, Jukka K. 2015. Handbook of Finnish. E-painos Oy: Online publication.Search in Google Scholar

Lees, Robert. 1961. The phonology of modern standard Turkish. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Levend, Agâh Sırrı. 1960. Türk dilinde gelişme ve sadeleşme evreleri [Stages of development and simplification in the Turkish language]. 2nd edn. Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu Basımevi.Search in Google Scholar

Lewis, Geoffrey L. 1967. Turkish grammar. Oxford: Clarendon Press.Search in Google Scholar

Mithun, Marianne. 1996. Grammatical sketches: The Mohawk language. In Jacques Maurais (ed.), Quebec’s aboriginal languages: History, planning and development, 159–173. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.10.21832/9781800418127-008Search in Google Scholar

Nakagawa, Shinichi & Holger Schielzeth. 2013. A general and simple method for obtaining

Nowak, Jessica & Damaris Nübling. 2017. Schwierige Lexeme und ihre Flexive im Konflikt: Hör- und sichtbare Wortschonungsstrategien. In Nanna Fuhrhop, Renata Szczepaniak & Karsten Schmidt (eds.), Sichtbare und hörbare Morphologie (Linguistische Arbeiten 565), 113–144. Berlin & Boston: De Gruyter.10.1515/9783110528978-005Search in Google Scholar

Nübling, Damaris. 2004. Zeitnamen. In Andrea Brendler & Silvio Brendler (eds.), Namenarten und ihre Erforschung. Ein Lehrbuch für das Studium der Onomastik, 835–856. Hamburg: Baar.Search in Google Scholar

Nübling, Damaris. 2005. Zwischen Syntagmatik und Paradigmatik: Grammatische Eigennamenmarker und ihre Typologie. Zeitschrift für Germanistische Linguistik 33(1). 25–56.10.1515/zfgl.2005.33.1.25Search in Google Scholar

Nübling, Damaris. 2012. Auf dem Weg zu Nicht-Flektierbaren: Die Deflexion der deutschen Eigennamen diachron und synchron. In Björn Rothstein (ed.), Nicht-flektierende Wortarten (Linguistik – Impulse und Tendenzen 47), 224–246. Berlin, New York: De Gruyter.10.1515/9783110276619.224Search in Google Scholar

Nübling, Damaris. 2014. Sprachverfall? Sprachliche Evolution am Beispiel des diachronen Funktionszuwachses des Apostrophs im Deutschen. In Albrecht Plewnia & Andreas Witt (eds.), Sprachverfall? Dynamik – Wandel – Variation, 99–123 (Jahrbuch des Instituts für Deutsche Sprache 2013). Berlin & Boston: De Gruyter.10.1515/9783110343007.99Search in Google Scholar

Nübling, Damaris. 2017. The growing distance between proper names and common nouns in German: On the way to onymic schema constancy. Folia Linguistica 51(2). 341–367.10.1515/flin-2017-0012Search in Google Scholar

Nübling, Damaris, Fabian Fahlbusch & Rita Heuser. 2015. Namen. Eine Einführung in die Onomastik. 2nd edn. Tübingen: Narr.Search in Google Scholar

Pugh, Stefan & Ian Press. 1999. Ukrainian: A comprehensive grammar. New York: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

R Core Team. 2020. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing.Search in Google Scholar

RAE/ASALE = Real Academia Española & Asociación de Academias de la Lengua (eds.). 2010. Ortografía de la lengua española. Madrid: Espasa.Search in Google Scholar

Rothstein, Robert. 2006. Slovak. In Keith Brown (ed.), Encyclopedia of language & linguistics, 419–422. Oxford: Elsevier.10.1016/B0-08-044854-2/02175-1Search in Google Scholar

Ryding, Karin C. 2005. A reference grammar of modern standard Arabic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511486975Search in Google Scholar

Scherer, Carmen. 2010. Das Deutsche und die dräuenden Apostrophe. Zur Verbreitung von ’s im Gegenwartsdeutschen. Zeitschrift für Germanistische Linguistik 38(1). 1–24.10.1515/zgl.2010.002Search in Google Scholar

Scherer, Carmen. 2013. Kalb’s Leber und Dienstag’s Schnitzeltag. Zur funktionalen Ausdifferenzierung des Apostrophs im Deutschen. Zeitschrift für Sprachwissenschaft 32(1). 75–112.10.1515/zfs-2013-0003Search in Google Scholar

Şimşir, Bilâl N. 1992. Türk Yazı Devrimi [The Turkish writing revolution]. Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu Basımevi.Search in Google Scholar

Steuerwald, Karl. 1963. Untersuchungen zur türkischen Sprache der Gegenwart. Teil 1: Die Türkische Sprachpolitik seit 1928. Berlin: Langenscheidt.Search in Google Scholar

Steuerwald, Karl. 1964. Untersuchungen zur türkischen Sprache der Gegenwart. Teil 2: Zur Orthographie und Lautung des Türkischen. Berlin: Langenscheidt.Search in Google Scholar

Stolz, Thomas, Nataliya Levkovych & Aina Urdze. 2017. Die Grammatik der Toponyme als typologisches Forschungsfeld: Eine Pilotstudie. In Johannes Helmbrecht, Damaris Nübling & Barbara Schlücker (eds.), Namengrammatik, 121–146. Hamburg: Buske.Search in Google Scholar

Strauss, Johann. 2008. Literacy and the development of the primary and secondary educational system; the role of the alphabet and language reforms. In Erik-Jan Zürcher (ed.), Turkey in the twentieth century, 479–516. Berlin: Schwarz.10.1515/9783110998511-022Search in Google Scholar

Taşdemir, Aynur. 2006. Harf devrimi ve Halk Mecmuası [The alphabet revolution and the Halk Mecmuası]. İstanbul: Yıldız Technical University MA thesis.Search in Google Scholar

TS Corpus = Sezer, Taner & Türker Sezer. 2012. TS Corpus V2 [491,360,398 tokens]. https://tscorpus.com (accessed 11 September 2020).Search in Google Scholar

TS TimeLine Corpus = Sezer, Taner & Türker Sezer. 2012. TS TimeLine Corpus [700,677,451 tokens]. https://tscorpus.com (accessed 11 September 2020).Search in Google Scholar

Türk Dil Kurumu (ed.). 1941. İmlâ Kılavuzu. İmlâ Lûgati’nin ikinci basımı [Spelling dictionary. Second edition of the İmlâ Lûgati]. 2nd edn. İstanbul: Cumhuriyet Basımevi.Search in Google Scholar

Türk Dil Kurumu (ed.). 1948. İmlâ Kılavuzu [Spelling dictionary]. 3rd edn. İstanbul: Milli Eğitim Basımevi.Search in Google Scholar

Türk Dil Kurumu (ed.). 1956. İmlâ Kılavuzu [Spelling dictionary]. 4th edn. Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu.Search in Google Scholar

Türk Dil Kurumu (ed.). 1957. İmlâ Kılavuzu [Spelling dictionary]. 5th edn. Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu.Search in Google Scholar

Türk Dil Kurumu (ed.). 1988. Türkçe Sözlük [Turkish dictionary]. 8th edn. Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu Basım Evi. https://sozluk.gov.tr.Search in Google Scholar

Türk Dil Kurumu (ed.). 2012. Yazım Kılavuzu [Spelling dictionary]. 27th edn. Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu. http://tdk.gov.tr/category/icerik/yazim-kurallari.Search in Google Scholar

Türker, Safiye. 2019. The politics of phonetics, orthography and grammar during the period from Tanzimat to the Alphabet Revolution. İstanbul: Yıldız Technical University MA thesis.Search in Google Scholar

Ünal-Logacev, Özlem, Marzena Żygis & Susanne Fuchs. 2019. Phonetics and phonology of soft ‘g’ in Turkish. Journal of the International Phonetic Association 49(2). 183–206.10.1017/S0025100317000317Search in Google Scholar

Vasil’eva, Natalija Vladimirovna. 2004. Institutionsnamen. In Andrea Brendler & Silvio Brendler (eds.), Namenarten und ihre Erforschung. Ein Lehrbuch für das Studium der Onomastik, 605–621. Hamburg: Baar.Search in Google Scholar

Yılmaz, Hale. 2013. Becoming Turkish: Nationalist reforms and cultural negotiations in early republican Turkey, 1923–1945. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Zimmer, Christian. 2018. Die Markierung des Genitiv(s) im Deutschen: Empirie und theoretische Implikationen von morphologischer Variation (Reihe Germanistische Linguistik 315). Berlin & Boston: De Gruyter.10.1515/9783110557442Search in Google Scholar

© 2021 Caro Reina and Akar, published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Special issue on The evolution of writing systems

- Artikel

- The evolution of writing systems

- Alternative criteria for writing system typology

- Spelling variation and text alignment

- Enregistered spellings in interaction

- Lost in Translation – Typographic variation in loanword surrounded punctuation positions

- Punctuation and text segmentation in 15th-century pamphlets

- The development of the apostrophe with proper names in Turkish

- Towards a broad-coverage graphemic analysis of large historical corpora

- Quantifying graphemic variation via large text corpora

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Special issue on The evolution of writing systems

- Artikel

- The evolution of writing systems

- Alternative criteria for writing system typology

- Spelling variation and text alignment

- Enregistered spellings in interaction

- Lost in Translation – Typographic variation in loanword surrounded punctuation positions

- Punctuation and text segmentation in 15th-century pamphlets

- The development of the apostrophe with proper names in Turkish

- Towards a broad-coverage graphemic analysis of large historical corpora

- Quantifying graphemic variation via large text corpora