Abstract

Henry Lawson is best known for his short stories of the Australian rural “bush.” He also wrote stories set in urban Sydney, and in a rediscovered letter he describes one of those stories, “Two Larrikins” (1893), as “realistic or Zolaistic.” The story is set in Lawson’s fictional Sydney slum locality of “Jones’ Alley,” also the title of one of the urban-set stories in his definitive collection While the Billy Boils (1896). This reference to Zola invites new attention to Lawson’s own slum setting and to his own conception of realism, as applied in his urban stories. The term “zolaistic” also alludes to the sex- and gender-related content of these stories, and that content connects in turn with contemporary feminist thought. The article argues that these aspects of the literary significance of Lawson’s early urban material were inevitably overshadowed by the Bush, obscuring some of the earliest examples of a minority Australian urban realist tradition.

1 The Class and Gender Geography of the City

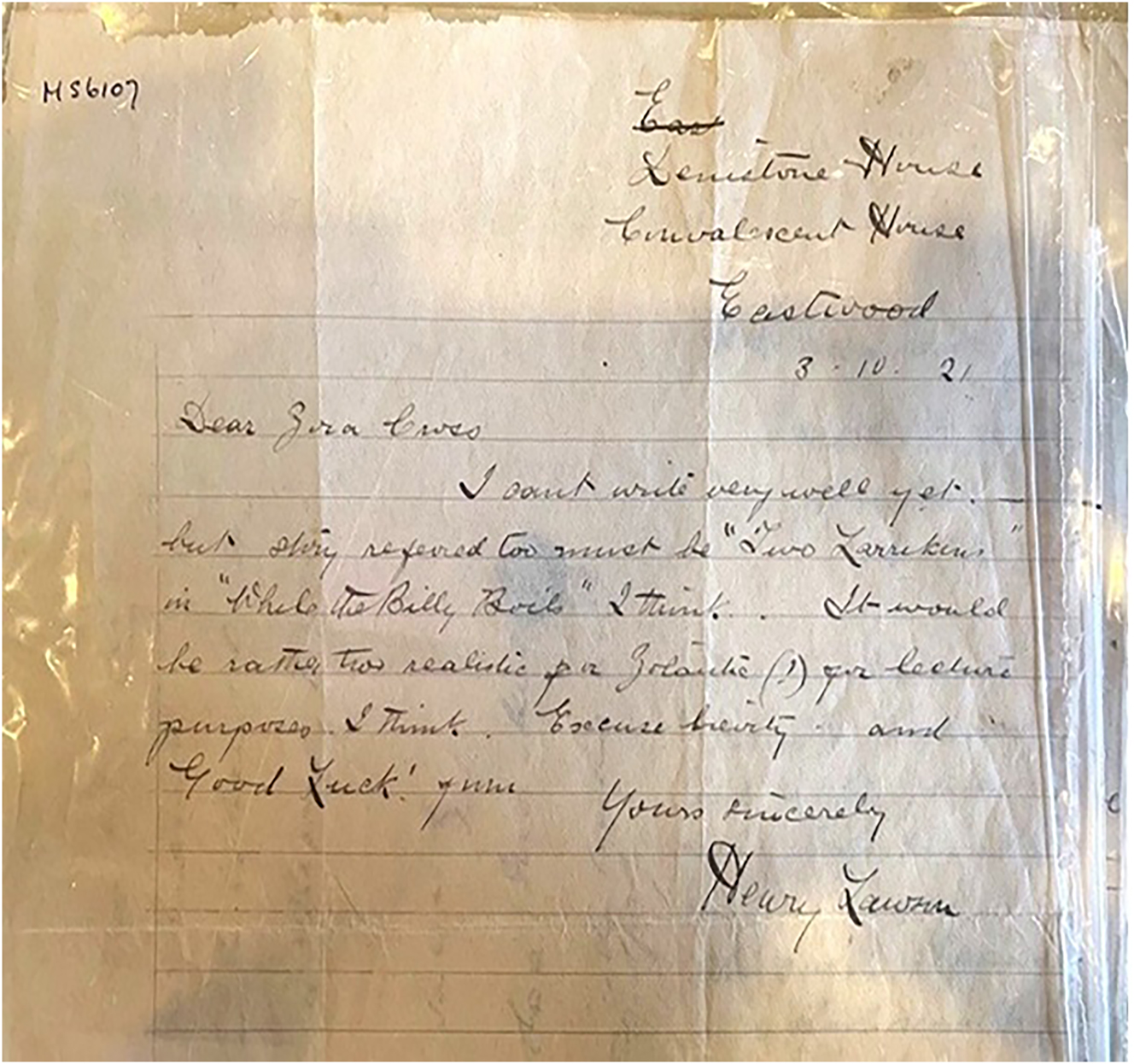

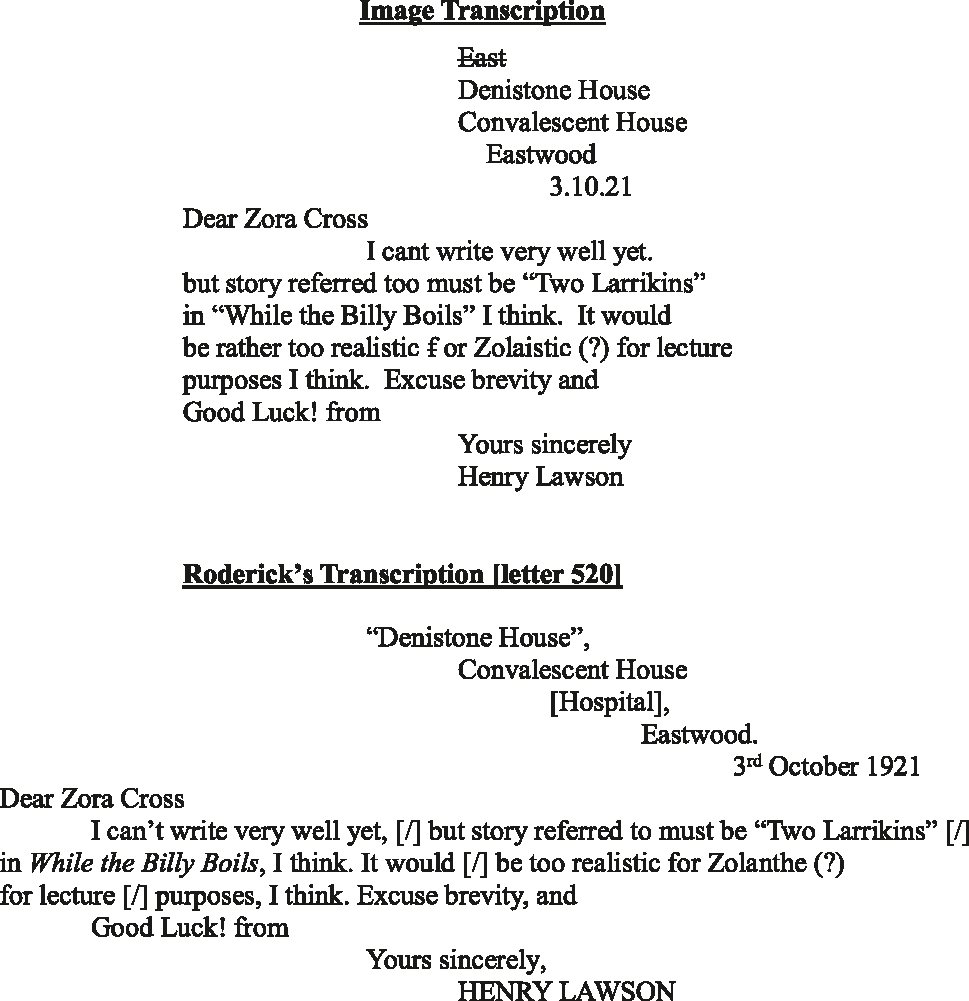

Henry Lawson is best known for his short stories of the Australian rural “bush,” and in that respect he has been compared with other Anglo-colonial frontier writers such as the American Bret Harte. Lawson expressed impatience with such comparisons in his “Preface” to Short Stories in Prose and Verse (1894). In 1921 he compared his own story set in inner Sydney, “Two Larrikins” (1893), with the work of Émile Zola, describing it as “realistic or Zolaistic.” Lawson’s use of the term “Zolaistic” has remained obscure because the word was wrongly transcribed in Colin Roderick’s Henry Lawson Letters ( 1972 ). An image of the letter is reproduced in the Appendix to this essay, with my transcription and notes.[1]

“Two Larrikins” is one of several stories set in Lawson’s fictional Sydney slum locality “Jones’ Alley,” also the title of a long story in his definitive collection While the Billy Boils (1896). It is well known that Lawson advocated literary realism but nowhere else in his writings does he compare his work to French novelist Émile Zola, author of L’Assommoir (1877), “the archetypal slum novel” (Keating 1971, 128). This s.a. reference to Zola invites new attention to Lawson’s own slum setting and to his own conception of realism as applied in his urban stories and revealed in his non-fiction (including the letter). Considered in this way, Lawson’s slum material has parallels with features of European realism identified in the major art and literary histories, Linda Nochlin’s Realism and Peter Keating’s Working Classes in Victorian Fiction. The term “zolaistic” also alludes to the sex- and gender-related content of some of these stories, and that connects in turn with contemporary Australian feminist thought. In this respect I refer to more recent feminist and demographic histories by Susan Margary, Marilyn Lake, and Helen Moylan. Australian studies of Lawson are surveyed in my conclusion; they have minimal or no reference to Lawson’s urban material. I argue that these aspects of the literary significance of Lawson’s early urban stories were inevitably overshadowed by the Bush, obscuring the beginnings of a minority Australian urban realist tradition.

The dialogue “Two Larrikins” begins with an unmistakable reference to the practice of abortion:

“Y’orter do something Ernie. Yer know how I am. You don’t seem to care. Y’orter do something.”

Stowsher slouched at a greater angle to the greasy door-post and scowled under his hat-brim. It was a little low frowsy room opening onto Jones’ Alley.

“Why don’t you go to some of them women and get fixed up?”

She flicked the end of the table-cloth over some tiny, unfinished article of clothing and bent to her work.

“But you know very well I haven’t got a shilling […] Where am I to get the money from?” (Prose I 230)

Nicole Moore has shown that literary euphemism can signal a cultural taboo and encode a set of norms opposed to it. Here “fixed up” signals the taboo then associated with abortion. Moore includes it in a list of abortion euphemisms but does not mention “Two Larrikins” (2001, 71). “To get fixed up” is very much a vernacular, vulgar expression, befitting the slum setting. In the law and in texts such as newspaper reports, the terminology for abortion was “procuring a miscarriage.” To do so by using drugs or other means was a criminal offence in colonial NSW and remained an offence until 2019 (Drabsch 2005, 19–20). Publishing information about contraception or abortion was then also liable to prosecution (Jarvis 1983, 407–8; Moore 2012, 44–6).[2]

One comparable literary text is identified by Moore, “Biddable Selina” (Bulletin, 5 April 1906), its author given only as “A. W.” The euphemisms in this story, used by the young pregnant woman herself, are to be “[made] right” and “[made] respectable.” Selina is employed as a servant girl on a rural property. The naïvety implied in that position is apparent when she realizes after a “couple of months” that her seducer, a gentleman guest, will not return. She withdraws her savings and consults a doctor who gives her an address in the city and a price of “20 pounds.” She sees the doctor “after dark” and travels in secret to the city. These details hint at the shame and transgression attached to her course. She dies in the city after a botched attempt by a nurse.

Moore’s essay was concerned with writers of the late 1930s and 1940s when it was possible to view such a story as cliché. The “fallen woman” certainly became a typical theme of European realism (Nochlin 1971, 199–201). “Two Larrikins” and “Biddable Selina” are rare Australian early treatments of the subject, before processes of familiarity and attitude-change had made it a cliché. Apart from the euphemism, however, the couple in “Two Larrikins” seem to treat abortion as a matter-of-fact option, without the moral revulsion often associated with transgression of a taboo. Nor is the couple naïve about the subject; they know it is performed by groups of women and available for a price. The phrase “them women” suggests non-medical practitioners. The dialogue continues on an economic basis, comparing the cost of abortion and rearing a child. Their matter-of-fact attitude may partly reflect class differences (Finch and Stratton 1988). But, as is soon clear, the young woman’s “work” is her argument for keeping the child; she does not view the problem purely as one of economic practicalities. She appeals to the father’s future emotional attachment to the child, arguing in effect that he should share the responsibility. He agrees, claiming it was always his intention to leave the “push” (street gang), marry the mother, and get a job. In the other stories marriage does not provide a solution.

Jones’ Alley is also the setting for three stories in While the Billy Boils (1896), including “Jones’ Alley” itself (1895). The main character in these stories, Mrs Aspinall, is a resident. Other common characters include her son Arvie and his workmate Bill Anderson in “Arvie Aspinall’s Alarm Clock” and “A Visit of Condolence: A Study from Life of a Sydney Larrikin” (both 1892). Two related stories had appeared by 1896 but were not included in the collection: “Two Larrikins” and “Two Boys at Grinder Brothers” (both 1893). The city factory of “Grinder Bros,” where Arvie and Bill work as boys, is also a common element. Several stories mention the presence of brothels in the locality. Two further stories are connected. The newswoman in “His Mother’s Mate” (1895) is mentioned in the story “Jones’ Alley.” The monologue “The Dying Anarchist” (1894) is connected by the unnamed speaker’s birth “among the brothels” and his “bitter servitude at Grinder Brothers” (Prose I 169–70).

The slum in late-nineteenth-century Sydney implies a topology locating the places of industrial production at a distance to the south and west of the city centre, and the residences of the middle class on the harbour to the north-east, the near east, and south. There was no industrial “north” as in English fiction (Keating 6–9). In Lawson’s fictional Sydney the real distances are compressed. Jones’ Alley is walking-distance to the Grinders factory in “Arvie Aspinall’s Alarm Clock” (WTBB 57, 59 note). The factory-owners’ residences on the harbour seem to be just visible from the slum.

The rain had cleared away, and a bright, starry dome was over sea and city, slum and villa alike; but little of it could be seen from the hovel in Jones Alley […] It was what the ladies call a ’a lovely night’ as seen from the house of Grinder […] with its moonlit terraces and gardens sloping gently to the water, and its windows lit up for an Easter Ball (WTBB 58).

The city centre (and its social disparities) appear in a Bulletin story-fragment from 1895, “His Mother's Mate.” The title substitutes “Mother” into the title of Lawson’s first-published prose story “His Father’s Mate” (1888), shifting the focus to the woman’s position.

The haggard woman sat on a step under the electric-light, by the main entrance of the theatre. She had one child on one arm, two more beside her, a pile of papers on her knee, and a cigar-box full of matches, bootlaces and bone studs, on the pavement by her foot.

A gentleman stepped out of the ‘marble bar’ opposite, stood for a moment on the kerb, glanced at his watch and then across at the theatre. He crossed over, and put his hand in his pocket as he reached the pavement.

‘Paper, sir?’ cried the newsboy. ‘Here y’are, mister – NEWS, STAR.’ But ’mister’ had noticed the woman and walked towards her.

‘Paper, sir! NEWS, STAR!’ cried the boy, dodging round in front; then, with a quick glance from ‘mister’s’ face to the newswoman, ‘It’s all right, mister. It’s all the same – she’s my mother … Thanks,’ (Prose I 42)

At that time there were several theatres in the city area near the offices and shops, the banks, the law courts, the hospital, and Parliament House. The opulent Marble Bar (built in 1892) was part of a hotel. In Lawson’s geography the city centre lies somewhere between the harbour villas and the slum, close enough for the newswoman to claim her city position each day. Elizabeth Webby’s note says the slum is based on “the Rocks,” a locality near the harbour and shipping wharves north-west of the city (WTBB 337–8). This geography of villas, city, factory, and slum is the setting for all the urban stories, implicit or present in a detail.

As he leaves the Marble Bar, the gentleman misconstrues the situation. Intending to give a coin to the newswoman, he tries to avoid the boy, assuming he is a venal street-competitor. The inference is that the middle class, insulated in its own world, does not comprehend the underclass that exists next-door, even though its members move in and out of the city each day. The two worlds are proximate, mutually incomprehensible and yet “porous,” as suggested in some recent theory (Heino and Jackson 2024).

The mother-workers of “Jones’ Alley” have much in common with the newswoman. The long story was first published in the Worker in three parts in June 1895. It opens with the statement of a woman’s position. “She” is not identified as Mrs Aspinall until later.

She lived in Jones’ Alley. She ‘cleaned offices,’ ‘washed’ and ‘nursed’ from daylight until anytime after dark and filled in her ‘spare time’ cleaning her own place […] cooking and nursing her own sick [children …] one or another of the children was always sick […] She was a haggard woman. Her second husband was supposed to be dead, and she lived in dread of his daily resurrection [sic]. Her eldest son was at large, but not yet […] hardened in misery, she dreaded his ‘getting into trouble’ even more than his frequent and interested appearances at home. She could buy off the son for a shilling or two and a clean shirt and collar, but she couldn’t purchase the absence of the father at any price – he claimed what he called his ‘conzugal rights’ as well as board, lodging, washing and beer. (WTBB 324; original emphasis)[3]

Mrs Aspinall and Mrs Anderson also move in and out of the city each morning to clean offices. Their husbands and the fathers of their children are also absent or dead (WTBB 41). Unlike the newswoman, they are able to work partly at home doing sewing and laundry, but like her, their capacity for work is restricted by the need to nurse small children. The newswoman mentioned later in the story employs several older children who operate as sharp competitors in the street news-business (WTBB 332). These older children are comparable to Arvie Aspinall and Bill Anderson, aged 11 and 12 at the time of the earlier stories, who must work in the Grinders factory to support their households.

“Jones’ Alley” is the fourth slum story in chronological terms, set some years after the sequence of a few days in the three earlier stories, “Two Boys at Grinder Brothers,” “Arvie Aspinall’s Alarm Clock,” and “A Visit of Condolence.” First, there is Arvie’s last work-shift at the Grinder factory, second, the gift of the alarm clock and his coughing illness and death, and third, Bill’s visit to the Aspinall house the next afternoon. In “Arvie Aspinall’s Alarm Clock” it is the last night of the Easter holidays, before Arvie’s next shift. Mrs Aspinall wakes early and notices that the alarm-clock has failed to rouse him. The image of his death forms the centre-piece of the early sequence.

She rose and stood by the sofa. Arvie lay on his back with his arms folded – a favourite sleeping position of his; but his eyes were wide open and staring upward as though they would stare through the ceiling and roof to the place where God ought to be. (WTBB 40)

Later that day Bill Anderson visits to inquire about Arvie’s absence from work. Mrs Aspinall tells him of Arvie’s death and the visit becomes one of condolence. Their viewing of “the white, pinched face of the dead boy” is as near as the reader comes to any funeral rites, reduced even from the small group of mourners for the death of the boy in “His Father’s Mate” (WTBB 40, 21). In “Two Boys at Grinder Brothers” Arvie is said to be missed at work “the next day” (Prose I 29). In the Alarm Clock story, however, he dies during the last night of the Easter holidays. Lawson introduces the intervening Easter holiday as a counterpoint to the boy’s death. The image of his death repudiates any ideas of elevation or transcendence associated with Easter, conforming with the realist pattern of death identified by Linda Nochlin (1971, 57–60).[4]

In “Jones’ Alley,” Bill Anderson has grown into a young man and leader of a “push”. Mrs Aspinall’s position has worsened. She has rent arrears (accruing at 10 shillings per week) and only a few pence in hand. The landlord’s agent visits Jones’ Alley to demand payment from her and others. Parts of her ceiling fall in, injuring one of the children. The Magistrates Court orders her (wrongly) to pay for house repairs. By chance, outside the court, Bill Anderson sees Mrs Aspinall and offers to help.

As appears from the opening passage of the story, the underlying cause of Mrs Aspinall’s predicament is her marriages, not the landlord. Marriage has removed her choice about her fertility. She had eight children. Five are still with her, Arvie is dead, and two elder sons have left home. Her eldest spends periods “at large” and in gaol. The second eldest moved to another city (WTBB 57–58, 324). The “conzugal rights” of her husband (slurred speech and euphemism) imply rape exercisable by drunken threat or force. “Conjugal rights” in popular belief meant that a wife must submit to sexual intercourse with her husband.[5] Eight children also indicate the absence of reliable contraception. Her position is generalised on a gender basis: “she” is one of many.

[…] widows with large families, or ‘women’ in the case of Jones’ Alley – who couldn’t afford it [the rent] without being half-starved, or running greater and unspeakable risks which “society” is not supposed to know anything about. (WTBB 326)

The narrator is explicit about the “society” producing the euphemism of “unspeakable risks,” but the underlying taboo is unclear. It might refer to engaging in prostitution for extra income. In context it seems to refer to abortion, with its own risks. Without affordable or reliable contraception, causing an early miscarriage was a means to avoid the consequences, personal and economic, of “large families.”

Opposite Mrs Aspinall’s front door is a brothel with its genial operator “Mother Brock.”

[Mrs Aspinall] was a ‘respectable woman,’ and was known in Jones’ Alley as ‘Misses,’ and called so generally, and even by ‘Mother’ Brock, who kept ’that place’ opposite […] and this distinction was about the only thing – excepting always the everlasting children – that the haggard woman had left to care about, to take a selfish, narrow-minded sort of pleasure in […] Mother Brock laughed good-naturedly. She was a broad-minded ‘bad woman,’ and was right according to her lights. Poor Mrs A. was a respectable, haggard woman, and was right according to her lights, and to Mrs Next-door’s. (WTBB 325; original emphasis)

“Respectability” is another euphemism that encodes norms (and taboos) relating to female gender. Being a “Misses” and being “respectable” means being married, the norm opposed to promiscuity/prostitution. Lawson presents marriage and respectability as a self-limiting, damaging condition for these women, contrasting with “broad-minded” Mother Brock, an example of female independence, and one who gives Mrs Aspinall some practical help (WTBB 327).

The realists of the nineteenth century were among the first to divide the emerging modern city into geo-social sectors. Sydney was an emerging modern city almost from its beginning (1788). By making “Jones’ Alley” the title of the story, Lawson invites inferences about the locality as distinct from the characters, and about its relationship with other sectors. In particular, it suggests a form of realist social determinism like Zola’s. The story makes several allusions to the broader Australian economic context in the “banks that went bust” and the “general depression” of the 1890s, affecting landlords and tenants alike (WTBB 328, 332; Fisher and Kent 1999; Hickson and Turner 1893). The slum itself is the product of the economic system, and the fate of its characters is determined in turn by that depleted urban environment. The history of Mrs Aspinall’s family and her sickly children represent this disadvantage; one elder son is “not yet hardened in misery.” The description of the “hump-back” and fantastically-receding chin of the boy “Chinny,” one of Bill Anderson’s “push,” hints also at disadvantages of heredity (WTBB 334–5).

Marital rape, conjugal rights, and respectability, however, point to the more fundamental disadvantage of gender roles, embodied in Mrs Aspinall. Unlike her, contemporary women sought increasingly to control their fertility to improve their independence and material position, preferring generally “female-controlled” forms of contraception and abortifacients. Working-class women used abortion at a higher rate than middle class women. By the 1890s the NSW birthrate had declined to such an extent that a Royal Commission was established to inquire into it. In the late 1880s and 1890s the Sydney press debated the related problem of abandoned children on the streets (Margarey 2001, 66–9, 102–5; Moylan 2020, 191–6, 201, 224; Finch and Stratton 1988, 45–64; Lake 1999, 32–4).[6]

By representing “respectable” marriage as a form of enslavement in a series of births, miscarriages, or “everlasting” periods of nursing, Lawson was, in effect, justifying women’s greater control of their fertility, and challenging the patriarchal ideology of “conzugal rights” or male sexual autonomy (Margarey 2001, 90–2; Allen 1994, 89–91; Lake 1999, 19–20, 35–6). Lawson was not a theorist but he was exposed to feminist thought by his involvement in his mother Louisa’s circle and her publishing work, in The Republican and her feminist magazine, The Dawn (1888–1905). Lawson helped print and must have read much of this material, and also contributed occasional pieces himself (Matthews 1988, 159–1, 322; Schaffer 1988, 141–2). Several articles in The Dawn are sources for the passages in “Jones’ Alley” about the drunken husband, large families, and conjugal rights.[7]

At the end of “Jones’ Alley” Bill Anderson and his push help Mrs Aspinall move house to live with a sister-in-law, while the local policeman turns a blind eye. Mrs Aspinall’s retreat in Chinny’s horse and cart, however, does not confirm any possibilities that work against the social determinism. Their procession out of Jones’ Alley is described as a “funeral” (WTBB 337). Throughout the urban stories Mrs Aspinall remains a central but exhausted figure, reflecting her circumstances rather than her personality. Nor does the group of stories suggest any hope in political reform. The narrator’s ironic observations at the end of “Two Boys at Grinder Brothers” make it clear that exploitation of child labour continues despite the “Education Act” (Prose I 29). The Alarm Clock story opens with the narrator’s ironic comments suggesting that the conservative press are whitewashing the exploitative factory owners (WTBB 55–6). The deathbed monologue of the unnamed “Dying Anarchist” traces a life from Jones Alley “among the brothels” to socialism, anarchism, and madness. Political disillusionment also appears in the non-fiction of the period, such as “The City and the Bush” (1893) and “The Cant and Dirt of Labour Literature” (1894).

2 Realism too Far?

“It would be rather too realistic or Zolaistic for lecture purposes.” To interrogate Lawson’s phrase in the letter, it is logical to begin with the category “realistic,” before the quantifier “too” and the term “Zolaistic.” Lawson’s best-known statement on literary realism, “Some Popular Australian Mistakes” (1893), was concerned with the bush, not urban conditions:

We wish to heaven that Australian writers would leave off trying to make a paradise out of the Out Back Hell; if only out of consideration for the poor, hopeless, half-starved wretches who carry swags through it and look for work in vain – and ask in vain for tucker very often. What’s the good of making heaven of a hell when by describing it as it really is, we might do some good for the lost souls there. (Prose II 25)

The background is the new age of literacy and mass-printing technology when fiction in newspapers and magazines became important sources of public information. The underlying idea is that literature, having that important position, should serve a useful social purpose (“do some good”). Lawson identifies a form of artistic representation as inimical to that purpose (making “a paradise out of hell” or idealisation). The corrective is realism, stated as an imperative to represent contemporary actuality (“describing it as it really is”). The current accurate picture is a necessary foundation for the purpose of social utility, in this case, some improvement to the conditions of bush workers.

In stating the imperative of contemporary actuality, Lawson was also stating (self-consciously or not) an identified central feature of realism in Europe, and one whose foremost expression was representation of the ordinary worker (Nochlin 1971, 103, 111–3). Lawson’s statement also uses the worker’s vernacular, not literary language. The vernacular was consistent with realist treatment of the working class, and Zola defended it on that basis for L’Assommoir (Keating 1971, 129–30). For Lawson, the vernacular bushman had entered his literary persona even for non-fiction. He used it to give authority to his views in the Bulletin newspaper debate that was the immediate context for “Some Popular Australian Mistakes.” And it was used against him by his “cultured” critics who wanted more complex work or an optimistic novel (Nesbitt 1971; Lee 2004, 28, 31–2). Lawson used impersonal dramatic realism in many stories, such as “Two Larrikins.” In the other Jones’ Alley stories there is also some ironic commentary or scene setting by the narrator. But in some stories the mind of the narrator mediates the actual events almost entirely, such as the characteristic sketches “Hungerford” or “In a Dry Season.” Lawson’s narrative persona was an un-Zola-like feature of his work, as Elizabeth Webby has observed (1981, 154).

Lawson repeated the argument of social utility in “If I Could Paint” (1899). He begins by referring to realism’s documentary value, for recording characters and ways of life that may soon pass into history. Then he imagines the path of the artist who travels to Europe (like Tom Roberts):

And if I went to Europe, it would be to learn to paint Australian, not old world scenes – the old world born can do that better than we. A Dutch tavern scene looks picturesque to us – probably on account of the costumes mostly – and is restful to our eyes and therefore good to have in our galleries. A real Dutch tavern scene mightn’t be any more picturesque otherwise than our own haggard threepenny bar, but – Anyway, Van de Velde can paint all our Dutch tavern scenes for us. Pictures of our threepenny bars might set men wishing for a different style of pub and a different fashion in drinking. (Prose II 37)

Here the argument is translated to urban conditions. Temperance reform was an important issue in the period (and for Lawson personally). By representing the ugly actuality of Sydney’s threepenny bars, so goes the argument, the artist might stimulate ideas of reform or better conduct. Applying Lawson’s conception of realism to “Jones’ Alley,” Mrs Aspinall and her locality are themselves the ugly picture that establishes the need for some (unspecified) reform. In this conception it would serve no useful purpose to present a stronger character who can rise above the slum, as English realists did (Keating 1971, 134–5).

The phrases – “as it really is” and “real Dutch tavern” – indicate the complexity of the contemporary usage. This was rarely concerned about the problem that artistic representation can have only a very indirect relationship with “reality” or the objective world. By the nineteenth century the cognate term “real” had acquired its modern sense – “actual, tangible, not merely apparent, not artificial.” “Realistic” or “describing it as it really is” refers to realism in a derivative sense, as a form of artistic representation – “faithful, true to life, rich in detail.” This sense had entered critical discourse in France by 1826. It was also a period term, denoting a new artistic movement and implying an adverse inference about competing or past artistic production. English-speaking and most French-speaking discourse did not detain itself with Zola’s coinage “naturalisme,” preferring the term “realism” (Borgerhoff 1938, 837–43; Becker 1980; 37–8; Keating 1971, 132). Lawson publicly used the term “realistic” only once, in “For the Future” (1899). He advocated a “realistic” national literature, without elaborating the concept itself. His main purpose was to attack critic A. G. Stephens for estimating his work as “parochial” and “scrappy” (Prose II 56; Stephens 1972, 51).

“Van de Velde” was probably a generic name for a Dutch/Flemish painter. Dutch painting and the relatively new technology of photography became common analogies for realism, denoting sometimes a valuable quality, and sometimes limited value in the form of over-minuteness or mere surface reproduction (Nochlin 1971, 44; Keating 1971, 138; Quartermaine 1978, 419–22). Genre painter Paulus Van der Velden (1837–1915) worked in New Zealand during Lawson’s time there, and is mentioned by A. G. Stephens in “Suffering Art” (1914), but there is no record of him in Lawson’s writings (Cantrell 1978, 370).

The term “Zolaism” appeared in English by 1885 when the Poet Laureate, Tennyson, deplored a range of modern trends in the long poem “Locksley Hall – 60 Years After,” including “troughs of zolaism.” It denoted an excessive form of realism, one that went too far into sordid subjects such as immorality, prostitutes, or slums (Keating 1971, 130–2, 136–7). In Australia Marcus Clarke expressed the idea of excessive realism, observing that Alphonse Daudet did not “go so deep into the awful Realities of poverty and crime as his contemporary Zola” (1880, 994). A critic in the Melbourne Australasian, however, wrote approvingly in 1893 of Kipling’s “Zolaesque study of backslum life” (Stilz 1985, 112). Like “realistic” and its analogies, the term could have a negative or positive sense, depending on the underlying attitudes of the critic. The Bulletin defended Zola from the negative association in 1884. “This work,” it thundered, referring to the new translation of Zola’s Nana,

[…] the precursor of a school of fiction – the realistic – is a work of absolute genius. It presents no spurious concoction of impossible immorality, but pictures aspects of actual life which it is probably useful should be recognized and fairly faced. (11 October 1884)

Lawson, already resident in Sydney for a year, must have heard and read about the public controversy of which this article was a part. The police had seized copies of Nana on the grounds of obscenity, along with some well-known works on contraception and abortifacients (Jarvis 1983, 407–8; Moore 2012, 44–6). Similar prosecutions and debate occurred later in Melbourne and London (Frierson 1928; Hubber 1990; Keating 1971, 126–7). Notably, the Bulletin’s defence of realism was based on the same argument of social utility later advanced by Lawson.

The syntax of the phrase in the letter is ambiguous. It could be read as alternatives, “too realistic or [too] zolaistic,” or it could be read as if “Zolaistic” were an equivalent of “too realistic.” The contemporary usage of the term supports the latter reading, as equivalents, because the term by itself could denote excess. This reading also fits the apparent context of the letter, but in either reading, the term must be an allusion to the content of the story, its reference to abortion in Sydney’s slums.

At the time of the letter, the addressee, Zora Cross, was preparing her Sydney Teachers’ College lectures for publication in book form, Introduction to the Study of Australian Literature (1922), in which she recommended “Two Larrikins” (1922, 64). Lawson was resident in a convalescent facility, Denistone House, to recover from the alcohol-related conditions that would contribute to his death a year later, aged 55. Cross had apparently inquired about one of Lawson’s stories, and he identified it by saying the “story […] must be ‘Two Larrikins.’” Cross’s inquiry might have referred to the subject of abortion. If so, Lawson correctly remembered the title. He was right to say it appeared “I think” in While the Billy Boils; in book-form it first appeared in On the Track (1900). Also, he apparently thought that Cross intended to use the story in a public lecture. In 1921 abortion remained illegal and it remained a taboo subject. The term “zolaistic” was a way of alluding to the ongoing public battle in Australia over censorship and wowserism (i.e., a denigratory description of people who - allegedly - indulge in immoral and sinful behaviour), which occurred not only on the fronts of art and literature, but also hotel trading, religious observance and swimming (Moore 2012, 45, 61; Dunstan 1968). Perhaps Lawson also remembered the matter-of-fact treatment of abortion in his story. He was warning or reminding Cross that her public may regard the subject as “too realistic.” Despite illness, his memory and reasoning on this were correct.

A final question from the letter, then, is whether Lawson was expressing a new reservation about his work, whether in 1921 he was suggesting that some of it was “too realistic” because he now accepted similar standards of propriety to those which led to public and official condemnation of Zola. If those standards applied to “Two Larrikins” they would certainly apply also to “Jones’ Alley” with its slum brothels and drunken marital rape.

Such a shift would be a significant one. The acceptance of such standards would be inconsistent with Lawson’s own idea of realism and its insistence on contemporary actuality. His urban stories express a rejection of those standards. Mrs Aspinall’s respectability is described as “narrow-minded.” The “unspeakable risks which ‘society’ is not supposed to know anything about” suggests the society’s wilful blindness to the risks, a form of hypocrisy. Lawson also rejected these standards privately. In a 1900 letter to Miles Frankin, he gave a warning similar to the Cross letter. He wrote that British publishers to whom he recommended her work – which he praised as “vividly realistic” – may want My Brilliant Career “toned down.” Referring to its “political and sex-problem passages” he reported later to his Australian publisher George Robertson that publishers Blackwoods had simply “struck ’em out” (Henry Lawson Letters 1972, 94, 99, 124). British publishing preference probably explains also why none of Lawson’s urban stories appeared in the first British editions of his work in 1901 and 1902: The Country I Came From and Children of the Bush. The better view is that Lawson did not intend to reject his own early work. He privately acknowledged the publishing imperatives and the public standards not to endorse them, but to signal a question about their validity – in the Cross letter, by using the question mark “too realistic or Zolaistic (?).”

3 Back to the Bush?

The group of pre-1896 urban stories was overwhelmed by Australia’s preoccupation with the bush. By the 1890s urban realist traditions were established in England and France (Keating 1971, 128–9; Nochlin 1971, 150–5). Australia’s largely urban society, however, continued to produce varieties of the bush as the dominant subject of its literature (McLaren 1980; Davidson 1978; Woodward 1975, 119). The bush also dominated critical attention, beginning with A. G. Stephens: “Henry Lawson is the voice of the bush, and the bush is the heart of Australia” (Lee 2004, 29). On Lawson’s death, one critic wrote as if the urban prose did not exist.

Therein [in his prose] he pictures Australia, not the Australia of the cities […] of Brisbane, or Sydney […] but the real Australia, the Australia of the miner, the fossicker, the selector. (Lee 2004, 62)

Lawson undoubtedly contributed to this by cultivating his bushman persona, and modern Lawson studies continued largely to ignore the urban material (Devanny 1942; Prichard 1943; Prout 1963; Murray-Smith 1975; Phillips 1970; Barnes 1985; Mitchell 1995). Harry Heseltine recognized it, if only as inferior and over-political (1960, 344; Lee 2004, 156). Two other leading studies illustrate the point. Brian Matthews’ Receding Wave (1972) makes the case for Lawson’s prose, yet barely touches the urban-set work up to 1896. His intended focus is Lawson as interpreter of the “interior” (Matthews 1972, 2–4, 127–8). The same can be said of Kay Schaffer’s Women and the Bush ( 1988 ). She notes that female characters in Lawson’s early stories “mostly live in the city” and then moves on to her intended focus–women and the bush (Schaffer 1988, 120).

Most of Lawson’s short stories are set in the bush; the urban stories are a small minority. Out of 52 stories in While the Billy Boils, six have an urban setting, including the three Jones’ Alley stories, two boarding-house stories, “Board and Residence” and “Going Blind,” and one new story, “Auld Lang Syne.” Three more Jones’ Alley stories had been published, but did not appear in the collection: “Two Larrikins” and “Two Boys at Grinder Bros” and “The Dying Anarchist.”

The mode of urban realism links these stories with a few other urban-set works of the period, including Fergus Hume’s The Mystery of a Hansom Cab (1886), Francis Adams’ Madeline Brown’s Murderer (1887), Edward Dyson’s Fact’ry ’Ands (1906), and Louis Stone’s Jonah (1910). The latter seems to owe much to Lawson’s urban stories. It opens with an unwanted slum pregnancy and its central character, father-to-be Jonah, is the hunchback leader of a larrikin push. Lawson’s letter suggests that, in his own view, the Jones’ Alley stories connected to European realism and Zola. Francis Adams publicly acknowledged Zola as a model of realism (Adams 1888; Jarvis 1982). More common was the view that recognized the connection but made a negative evaluation of it. Conservative critics in The Development of Australian Literature (1898), for example, deplored the “unclean realism of George Moore, and the many English followers of Zola” (Sutherland and Turner 1898, 26). Gerhard Stilz has offered an encompassing explanation for the acceptance or rejection of Zola’s realism by Australian writers and critics, in its perceived correlation with their own ideas of Australian national development (1990, 479–81).

The connection of these stories with contemporary feminist thinking is also a part of their literary significance. The Lawson criticism focused on the bush often identifies the expression of an ethos of male “mateship.” The Jones’ Alley stories attempt unmistakably to represent working-class women, not just in a “harsh urban environment” as suggested by Kay Schaffer, but in relation to identifiable negative elements of the patriarchal social system, including “conjugal rights,” “respectability,” and access to birth control. The specific occasion for Lawson’s use of the term “Zolaistic” was the topic of unplanned pregnancy and abortion in his own story. In this way his urban stories look forward to the later Australian realist fiction about sex, class and abortion examined by Nicole Moore (2001).

This kind of picture was not so available from Lawson’s women in the Bush, such as middle-class Mrs Spicer with her table napkins or the Drover’s Wife with her Sunday walks and Young Ladies’ Journal. For these women, the city is far away, even the object of nostalgic memories. But it would be wrong to draw too sharp a distinction. All cling to forms of respectability; all are alone with their children. Mrs Aspinall, the Newswoman, Mrs Spicer and the Drover’s Wife are all described as “haggard” or “gaunt” or both (Prose I 573, 582; WTBB 61, 65, 68). These repeated terms signify the personal toll of the environments in which the women live, on their faces and their bodies. The end human result of both environments is the same.

Amid the Australian strikes and economic depression of the 1890s, Lawson called for recognition of the common identity of bush workers and city women workers. In “The City and the Bush” (1893), he complained that

[t]here should be a strong bond of sympathy between the bush workers and those in the cities in Australia – and there isn’t […] because they […] misunderstand each other […] What of the poor city women – widows and the wives of loafing or drunken husbands – who have to keep the children and pay the rent of ten shillings […]? What of the women who have twelve or thirteen hours a day for from 2s. 6d […] What of the girls in sweating dens at five shillings per week? (Prose II 27–8)

The story “Jones’ Alley” re-used some of these details. Brian Matthews’ unconventional biography Louisa and Kay Schaffer’s Women and the Bush also point in this direction - to the influence of Louisa Lawson and the rich literary possibilities of Louisa’s urban Sydney. Whatever those possibilities, for Henry Lawson they remained moot. After 1896 no further urban-set stories appeared until the pastiche “The Rising of the Court” (1908) and the “Elder Man’s Lane” series (1912–1920). The later stories do not have any of the characters, themes, or setting from the earlier group. As Kay Schaffer has shown, anti-feminist and misogynist themes began to appear in his later work, such as “The She Devil” (1904).

Notes on Transcriptions

The notes refer to line numbers in the image text. For lines 7, 10, and 12, I have indicated uncertain or speculative readings by a question mark. In the Roderick transcription I have indicated the image line-endings by [/]. Roderick does not identify, nor have I identified, any contemporary with the name “Zolanthe.”

Ln 1. “MS6107” is a manuscript number of the State Library of Victoria, Melbourne. “East” crossed out. “Eastwood” (ln 4) is a suburb of Sydney.

Ln 7. Full stop wrongly inserted at end of line? Omitted by Roderick.

Ln 8. “too” should be “to.” Corrected by Roderick.

Ln 9. Roderick inserts italics in title and comma.

Ln 10. After “realistic,” crossed-out lower-case “f” and space (transcribed as “f ”). The crossing-out looks like “>”? Comparable with the letter “f” in “referred” and “for.” After crossed-out “f” and space, “or” is comparable with those letters in “Zora” and “for.” HL may have started the phrase “for lecture purposes” but crossed out “f,” deciding to insert “or Zolaistic”? The space after the crossed-out “f” does not support Roderick’s “for.” The “Z” is comparable to the addressee’s name “Zora.” The ending “-istic” is clearly preferable to Roderick’s “-anthe.” The question mark is curved, not straight as in exclamation mark after “Good Luck!” (ln 12).

Ln 11. Roderick adds comma after “purposes.”

Ln 12. Third word indecipherable? I have adopted Roderick’s “from.”

References

Adams, F. 1888. “Realism.” Centennial Magazine 1 (1): 56–60.Search in Google Scholar

Allen, J. 1994. Rose Scott: Vision and Revision in Feminism. Melbourne: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Barnes, J. 1985. Henry Lawson’s Short Stories. Melbourne: Shillington House.Search in Google Scholar

Becker, G. 1980. Realism and Modern Fiction. New York: Frederick Ungar.Search in Google Scholar

Borgerhoff, E. B. O. 1938. “Realism and Kindred Words: Their Use as Terms of Literary Criticism in the First Half of the Nineteenth Century.” PMLA 53 (3): 837–43, https://doi.org/10.2307/458657.Search in Google Scholar

Cantrell, L., ed. 1978. A. G. Stephens: Selected Writings. Angus & Roberston.Search in Google Scholar

Clarke, M. 1880. “A French Dickens.” Victorian Review 1 (6): 994.Search in Google Scholar

Cross, Z. 1922. Introduction to the Study of Australian Literature. Sydney: Angus & Robertson.Search in Google Scholar

Davidson, G. 1978. “Sydney or the Bush: An Urban Context for the Australian Legend.” Historical Studies 18 (71): 191–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/10314617808595587.Search in Google Scholar

Devanny, J. 1942. “The Workers Contribution to Australian Literature.” In Australian Writers Speak. Sydney: Angus & Robertson.Search in Google Scholar

Drabsch, T. 2005. Abortion and the Law in New South Wales. Sydney: NSW Parliamentary Research Service.Search in Google Scholar

Dunstan, K. 1968. Wowsers. Melbourne: Cassell.Search in Google Scholar

Finch, L. and J. Stratton. 1988. “The Australian Working Class and the Practice of Abortion.” Journal of Australian Studies 23: 45–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/14443058809386981.Search in Google Scholar

Fisher, C., and C. Kent. 1999. “Two Depressions, One Banking Collapse.” Reserve Bank Research Paper 1999–06, https://www.rba.gov.au/publications/rdp/1999//1999-06.Search in Google Scholar

Frierson, W. C. 1928. “The English Controversy over Realism.” PMLA 43: 522–50.Search in Google Scholar

Heino, B., and L. Jackson. 2024. “‘The Mystery of a Hansom Cab’ as a Spatial Artefact: Exploring Class and the Spatial Unconscious in Nineteenth Century Australia’s Favourite Whodunnit.” ALS 39 (3).Search in Google Scholar

Heseltine, H. 1960. “Saint Henry: Our Apostle of Mateship.” In Henry Lawson Criticism, Vol. 344, edited by C. Roderick. Angus & Robertson.Search in Google Scholar

Hickson, C. R., and J. D. Turner. n.d. “Free Banking Gone Awry: The Australia Banking Crisis of 1893.” Financial History Review 9 (2): 147–67, https://doi.org/10.1017/s0968565002000124.Search in Google Scholar

Hubber, B. 1990. “The Victorian Customs Department and Respectable Limits of Taste: Emile Zola and Colonial Censorship.” French Australian Review 9: 3–15.Search in Google Scholar

Jarvis, D. 1982. “Francis Adams: Australia’s Champion of Realism.” New Literature Review 12: 25–35.Search in Google Scholar

Jarvis, D. 1983. “Morality and Literary Realism: A Debate of the 1880s.” Southerly 43 (4): 404–20.Search in Google Scholar

Keating, P. J. 1971. The Working Classes in Victorian Fiction. Routledge and Kegan Paul.Search in Google Scholar

Lake, M. 1999. Getting Equal: The History of Australian Feminism. Sydney: Allen & Unwin.Search in Google Scholar

Lawson, H. 1972a. “Prose I.” In Short Stories and Sketches 1888-1922, edited by C Roderick. Sydney: Angus & Robertson.Search in Google Scholar

Lawson, H. 1972b. “Prose II.” In Autobiographical and other Writings 1887-1922, edited by C Roderick. Sydney: Angus & Robertson.Search in Google Scholar

Lawson, H. 2013. “While the Billy Boils.” In While the Billy Boils, edited by P. Eggert and E. Webby. Sydney: Sydney University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Lee, C. 2004. The City Bushman: Henry Lawson and the Australian Imagination. Fremantle: Curtin University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Margarey, S. 2001. Passions of the First-Wave Feminists. Sydney: Sydney University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Matthews, B. 1972. The Receding Wave. Melbourne University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Matthews, B. 1988. Louisa. Melboure: McPhee Gribble.Search in Google Scholar

McLaren, J. 1980. “Colonial Mythmakers: The Development of the Realist Tradition in Australian Literature.” Westerly 2 (5): 43–9.Search in Google Scholar

Mitchell, A. 1995. The Short Stories of Henry Lawson. Sydney: Sydney University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Moore, N. 2001. “The Politics of Cliche: Sex, Class and Abortion in Australian Realism.” Modern Fiction Studies 47: 69–91. https://doi.org/10.1353/mfs.2001.0006.Search in Google Scholar

Moore, N. 2012. The Censor’s Library. St Lucia: University of Queensland Press.Search in Google Scholar

Moylan, H. 2020. The Australian Fertility Transition: A Study of 19th Century Australia. Canberra: ANU Press.Search in Google Scholar

Murray-Smith, S. 1975. Henry Lawson. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Nesbitt, B. 1971. “Literary Nationalism and the 1890s.” ALS 5 (1): 3–17, https://doi.org/10.20314/als.8c839619ab.Search in Google Scholar

Nochlin, L. 1971. Realism. Pelican.Search in Google Scholar

Phillips, A. A. 1970. Henry Lawson. Twayne.Search in Google Scholar

Prichard, K. S. 1943. “The Anti-Capitalist Core of Australian Literature.” Communist Review 24.Search in Google Scholar

Prout, D. 1963. Henry Lawson: The Grey Dreamer. Rigby.Search in Google Scholar

Quartermaine, P. 1978. “The Literary Photographs of Henry Lawson.” ALS 8 (4): 419–34, https://doi.org/10.20314/als.715c8667bc.Search in Google Scholar

Roderick, C. 1972. Henry Lawson Letters. Sydney: Angus & Robertson.Search in Google Scholar

Schaffer, K. 1988. Woman and the Bush: Forces of Desire in the Australian Cultural Tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Stephens, A. G. 1972. “Henry Lawson’s Prose.” In Henry Lawson Criticism, Vol. 51, edited by C. Roderick. Sydney: Angus & Robertson.Search in Google Scholar

Stilz, G. 1985. “Kipling’s Visit and the Early Reception of his Books in Australia 1889–1900.” ALS 12 (1): 105–15, https://doi.org/10.20314/als.a45c6800e8.Search in Google Scholar

Stilz, G. 1990. “Nationalism before Nationhood: Overseas Horizons in Debates of the 1880s.” ALS 14 (4): 476–88, https://doi.org/10.20314/als.5497650155.Search in Google Scholar

Sutherland, A. and H. G. Turner. 1898. The Development of Australian Literature. London: Longmans.Search in Google Scholar

Webby, E. 1981. “Australian Short Fiction from while the Billy Boils to the Everlasting Secret Family.” ALS 10 (2): 147–64. https://doi.org/10.20314/als.c60edd9c1f.Search in Google Scholar

Woodward, J. 1975. “Urban Influence in Australian Literature in the Late Nineteenth Century.” ALS 7 (2): 115–29.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Editorial

- Articles

- Horror Polaris: Lovecraft, Dickens, Poe, and the Horror of Polar Exploration

- Henry Lawson’s Slum Stories: “Jones’ Alley,” Gender, and Birth Control

- “The Priestess, the Medium, the Prophetess”: Identity in British Modernist Literary Patronage

- A Microscopic History of War Through Women’s Stories: Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Half of a Yellow Sun

- The Liminal Space: Unravelling Borderland Mentality in Cormac McCarthy’s The Road

- Book Reviews

- David Finkelstein, David Johnson and Caroline Davis: The Edinburgh Companion to British Colonial Periodicals

- Judith Rauscher: Ecopoetic Place-Making: Nature and Mobility in Contemporary American Poetry

- Friederike Danebrock: On Making Fiction: Frankenstein and the Life of Stories

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Editorial

- Articles

- Horror Polaris: Lovecraft, Dickens, Poe, and the Horror of Polar Exploration

- Henry Lawson’s Slum Stories: “Jones’ Alley,” Gender, and Birth Control

- “The Priestess, the Medium, the Prophetess”: Identity in British Modernist Literary Patronage

- A Microscopic History of War Through Women’s Stories: Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Half of a Yellow Sun

- The Liminal Space: Unravelling Borderland Mentality in Cormac McCarthy’s The Road

- Book Reviews

- David Finkelstein, David Johnson and Caroline Davis: The Edinburgh Companion to British Colonial Periodicals

- Judith Rauscher: Ecopoetic Place-Making: Nature and Mobility in Contemporary American Poetry

- Friederike Danebrock: On Making Fiction: Frankenstein and the Life of Stories