The Female Gaze of Western Retirees in Hua Hin, Thailand

-

Stefanie Wallinger

Stefanie Wallinger is a researcher and lecturer at the Department of Business & Tourism at Salzburg University of Applied Sciences. Her research focuses on qualitative social science tourism research and the interdisciplinarity of gender and tourism studies.Stefanie Wallinger ist Researcherin und Dozentin am Department Business & Tourism der Fachhochschule Salzburg. Ihre Forschungsschwerpunkte liegen in der qualitativen, sozialwissenschaftlichen Tourismusforschung und Interdisziplinarität von Gender- und Tourismuswissenschaft.

Abstract

This article examines the perspectives of Western female retirees in Hua Hin, Thailand, addressing the underrepresented experiences of women in international retirement migration literature. Focusing on everyday life, social relationships, and the challenges of aging abroad, it explores the intersections of gendered migration, intercultural relationships, and female support systems. The central research question investigates how these women experience retired life, with sub-questions concerning the specific challenges faced by single women, their social interactions, and their views on relationships between Western men and Thai women.

The literature review highlights the dominance of male-centric perspectives in retirement migration studies, mirroring broader trends in tourism research, and – drawing on Urry’s concept of the tourist gaze – establishes a Western female gaze that addresses this gap. The study adopts an exploratory qualitative design based on semi-structured interviews with nine German-speaking Western female retirees, analysed using the documentary method of interpretation.

The findings reveal that participants navigate their identities between a sense of belonging and foreignness, often relying on strong female support networks to manage emotional insecurities and social challenges. Their Western female gaze, shaped by continual comparison with familiar cultural norms, produces an ambivalent sense of connection and alienation in the host society.

Zusammenfassung

Dieser Beitrag untersucht die Perspektiven westlicher Rentnerinnen in Hua Hin, Thailand, und adressiert damit die bislang in der internationalen Literatur zur Altersmigration unterrepräsentierten Erfahrungen von Frauen. Im Zentrum stehen Alltagspraktiken, soziale Beziehungen sowie die Herausforderungen des Alterns im Ausland. Analytisch werden die Schnittstellen von geschlechtsspezifischer Migration, interkulturellen Partnerschaften und weiblichen Unterstützungsnetzwerken betrachtet.

Die zentrale Forschungsfrage richtet sich darauf, wie westliche Frauen ihren Ruhestand in Hua Hin erleben. Untergeordnete Fragestellungen betreffen die besonderen Herausforderungen alleinstehender Frauen, deren soziale Interaktionen sowie ihre Wahrnehmungen von Beziehungen zwischen westlichen Männern und thailändischen Frauen.

Die Literaturanalyse verdeutlicht die Dominanz männlich geprägter Perspektiven in Studien zur Altersmigration, was zugleich breitere Trends in der Tourismusforschung widerspiegelt. Aufbauend auf Urrys Konzept des tourist gaze wird der Begriff des westlichen weiblichen Blicks entwickelt, um diese Forschungslücke zu adressieren.

Methodisch folgt die Studie einem explorativen qualitativen Design. Grundlage bilden halbstrukturierte Interviews mit neun deutschsprachigen westlichen Rentnerinnen, die mithilfe der dokumentarischen Methode ausgewertet wurden.

Die Ergebnisse zeigen, dass die Befragten ihre Identität im Wechselspiel von Zugehörigkeit und Fremdheit konstruieren und dabei häufig auf weibliche Unterstützungsnetzwerke innerhalb der Gemeinschaft westlicher Zuwanderinnen zurückgreifen, um emotionale Unsicherheiten und soziale Herausforderungen zu bewältigen. Der westliche weibliche Blick, geprägt durch den kontinuierlichen Vergleich mit vertrauten kulturellen Normen, erzeugt ein ambivalentes Spannungsfeld von Verbundenheit und Entfremdung gegenüber der thailändischen Gastgesellschaft.

1 Introduction

The phenomenon of Western retirement migration to Thailand has become a significant area of inquiry within migration studies, sociology, and gerontology. As global mobility increases and aging populations in Western countries seek affordable and culturally rich destinations for retirement, Thailand has emerged as a particularly popular choice.

According to the International Migration Stock 2020, 12 percent of the 281 million migrants worldwide are over 65 years old (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division 2020). While male migrants generally outnumber female migrants, with the share of females slightly decreasing since 2000 (International Organization for Migration 2024a), this is not the case for older populations (International Organization for Migration 2024b). As of mid-2020, women slightly outnumbered men among older international migrants, representing 6.8 percent of the global migrant population, compared to 5.4 percent for older men (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division 2020). The motives, experiences, and challenges have diversified over time, shaped by a range of sociodemographic factors (Repetti and Calasanti 2023a). While labour, education, and family remain the primary drivers of international migration – alongside forced displacement due to conflict, persecution, or disaster – the number of individuals migrating for lifestyle and quality-of-life reasons in later life has steadily increased over recent decades (International Organization for Migration 2024b).

Schweppe (2022) highlights the role of global inequalities in shaping retirement migration, noting that low income in old age can be a major push factor for older people seeking more affordable living conditions in countries of the Global South. This trend also reflects the impact of neoliberal and austerity-driven welfare reforms in high-income countries, which have increased financial precarity among retirees (Repetti and Calasanti 2023a). From a gendered perspective, Gambold (2013) shows that single women often view international migration as a strategic means of mitigating poverty risks associated with the pension gender gap – stemming from part-time employment, divorce, or widowhood.

However, from a postcolonial perspective, it is important to recognise that the privilege to sustain or improve one’s lifestyle by locating to a lower-income country is rooted in longstanding global inequalities and geopolitical legacies (Botterill 2017; Repetti and Calasanti 2023; Tang and Zolnikov 2021). This dynamic positions retirement migrants as privileged actors in terms of race, class and nationality (Savaş et al. 2023), with implications not only for the migrants themselves but also for the host societies they enter.

Prior tourism experience also plays an essential role in retirement migrants’ decision-making (Barbosa et al. 2021; Butratana et al. 2022). In Thailand, a well-established tourism industry – interrupted only by the Covid-19 pandemic – has laid the groundwork for the growth of expatriate communities. The country is often cited as an ideal destination due to its relatively low cost of living, favourable climate, accessible healthcare, and perceived cultural hospitality (Howard 2008). These conditions have attracted large numbers of Western retirees, particularly to urban and coastal areas (Husa and Vielhaber 2014). In their case study on retirement migration in Hua Hin and Cha-am, Husa and Vielhaber (2014) show that retirees bring both economic capital and cultural norms that reshape local social structures, sometimes fostering enrichment, but also generating tensions and new social stratifications.

Ethnographic studies such as that of Jaisuekun and Sunanta (2017) on German lifestyle migrants in Pattaya further explore how economic motivations intersect with gendered patterns, particularly in relationships between older male and younger Thai women. Such relationships play a key role in shaping power structures and community dynamics. However, the literature remains heavily focused on male retirees and reflects gendered drivers such as marriage migration and social privilege. In contrast, the experiences of female retirees are still largely underexplored.

The present article aims to address this gap by foregrounding women’s perspectives in retirement migration to Thailand. Simultaneously, it builds on Urry’s theorization of the tourist gaze, which conceptualizes how tourists view and interpret destinations through culturally constructed expectations. As Zhang and Hitchcock (2017) emphasize, engaging the gendered dimensions of the tourist gaze is essential, since Urry’s original formulation largely overlooks how tourist experiences are shaped by gendered power relations. By foregrounding women’s perspectives and the female tourist gaze, this article contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of women’s underrepresented experiences in international retirement migration literature (Gambold 2013; Samarathunga and Cheng 2021). It underscores the need for a gender-sensitive approach to migration studies – one that acknowledges the diverse experiences of women and the specific ways in which they engage with their social and cultural environments. Furthermore, the work links retirement migration to global inequalities and late life precarity, distinguishing economically privileged movers from those seeking to mitigate financial insecurity, with particular attention to gendered risks faced by older women (Schweppe 2022; Repetti and Calasanti 2023; Savaş et al. 2023; Gambold 2013). It engages Thailand-specific research that traces the growth of expatriate communities and the gendered dynamics of Thai–Western relationships (Howard 2008, 2009; Husa and Vielhaber 2014; Jaisuekun and Sunanta 2016; Butratana et al. 2022; Tang and Zolnikov 2021).

Against this backdrop, the article complements prior work by foregrounding German-speaking Western women in Hua Hin examining their living situations, challenges and social relationships and elaborating a ‘Western female gaze’ that links everyday belonging, moral evaluation, and intercultural intimacy. It departs from predominantly male-focused accounts by showing how women’s support networks and vulnerabilities, especially among single retirees, reframe prevailing narratives of Thai–Western relations.

The central research question guiding this study is: How do female Western migrants experience their retired life in Hua Hin, Thailand? Sub-questions address their experiences of community life in Hua Hin and their perspectives on the prevalent intercultural relationships between Western men and Thai woman.

The empirical section outlines the qualitative research design and the use of the documentary method to analyse interviews with nine Western female retirees. The article concludes with a summary of key findings conceptualised in a model of the Western female gaze, followed by reflections on methodological limitations and suggestions for future research.

2 Theoretical Framework: The Tourist Gaze and Its Gendered Reinterpretation

Building on Foucault’s concept of the medical gaze (1963), John Urry (1990, 2009) defines the tourist gaze as a socially organized and systemised phenomenon. It is not a neutral or natural way of seeing but one shaped by cultural norms, media representations, and prior experience. Tourism emerges from temporary movement away from home and involves gazing upon the unfamiliar through socially constructed expectations. Urry argues that the multiplicity of tourist gazes is influenced by factors such as age, gender, and nationality. However, the original framework has been critiqued for its androcentric bias. Zhang and Hitchcock (2017) call for critical engagement with the gendered dimensions of the tourist gaze, emphasizing that visual practices in tourism are embedded within unequal gendered power relations, particularly in postcolonial settings. Their work underscores the need to explore how women not only experience but also perform the gaze differently from men.

These critiques resonate with broader postcolonial and intersectional perspectives that highlight the Western-centric and heteronormative underpinnings of much tourism theory. Scholars such as Pritchard and Morgan (2000) argue that tourism, as a cultural practice, often privileges white, male, heterosexual viewpoints, marginalizing female and queer perspectives. The tourist gaze, when viewed through an intersectional lens, reveals how race, gender, class, and age co-produce hierarchies of seeing and being seen. In retirement migration contexts, this becomes particularly salient, as perceptions of otherness, exoticism, and intimacy are filtered through overlapping structures of privilege.

Drawing upon Urry’s dichotomy of home versus away, retirement migration can be conceptualised as an in-between space. As noted by Åkerlund and Sandberg (2015), Barbosa et al. (2021), Kordel (2015), and Williams and Hall (2000) tourism often acts as a precursor to lifestyle migration. Retirement migrants frequently experience a duality of belonging and estrangement, navigating their lives somewhere between tourist mobility and residential permanence. In this context, prior travel plays an essential role in shaping migrants’ decisions. Barbosa et al. (2021) note that tourism experiences provide not only practical knowledge but also emotional attachment and early social ties to a place. Network theory further suggests that connections with both local residents and co-national expatriates help reduce perceived barriers, allowing migrants to reconstruct familiar routines abroad (Kordel 2015). Through the lens of gaze theory, such reconstructions are not merely physical but visual and symbolic – retirement migrants reinterpret spaces once seen as tourist sites into familiar environments. These perceptions are mutually shaped by what Urry calls the ‘mutual gaze’, where locals and foreigners co-construct expectations and behaviors (Urry 2009).

Yet, gender remains an underexplored dimension. Samarathunga and Cheng (2021) highlight the lack of attention to the female gaze and the female host gaze in tourism studies. This neglect is echoed in international retirement migration literature, where the focus has predominantly been on heterosexual male retirees (Butratana et al. 2022; Gambold 2013; Howard 2009; Koch-Schulte 2008; Sampaio 2018; Schweppe 2022; Thang et al. 2012). As Pritchard (2004) notes, tourism research has long privileged male experiences and suppressed alternative narratives, especially those of women and queer individuals. The resulting knowledge production often reinforces heteropatriarchal norms and renders female retirees either invisible or passive. While the experiences and perceptions of women remain on the margin of tourism research interests, their role in tourism has been highly acknowledged as producers rather than as consumers of tourism. Much gender tourism research has been devoted to women’s employment patterns and the sex tourism industry (Pritchard 2004).

The investigation of host-guest relationships forms a major research strand of gender tourism studies and has likewise received much attention in retirement migration literature. Moreover, dominant representations of intercultural relationships in Thailand reinforce gendered binaries. Western women are often portrayed as sceptical or moralistic observers of Thai-Western partnerships, while Thai women are either vilified or exoticized (Howard 2009; Scuzzarello 2020). This reinforces a white, male-centric tourist gaze that objectifies Thai women and positions Western women on its margins. The voices of single female retirees, as highlighted in studies by Gambold (2013), Sampaio (2018), Thang et al. (2012) and Lulle and King (2016) reveal shared motivations rooted in freedom and self-determination. Despite diverse destinations, these women commonly emphasize individualism and liberation from conventional gender roles. The studies further highlight aspects such as financial independence (Gambold 2013), emotional and romantic fulfilment (Sampaio 2018), gendered migration dynamics, and personal growth and well-being in new environments (Thang et al. 2012).

In sum, integrating a gendered lens into the existing tourist gaze framework expands its theoretical scope by proposing a patterned way of seeing that emerges at the intersection of gendered life courses, post-colonial privilege and the liminal status of long-stay tourists. While Zhang and Hitchcock (2017) highlight how female tourists perform a gaze that blends self-reflexivity, aesthetic appreciation, and consumer desire, the understanding of the female gaze in this study is deeply embedded in personal identity formation and affective engagement. The gaze is grounded in moral evaluation, cultural comparison, and postcolonial hierarchies, where Western women often assess local gender dynamics and Thai-Western relationships through a lens shaped by their own cultural and gendered expectations. The Western female gaze operates as a socially constructed perceptual framework shaped by gendered and racialized histories, through which local actors, especially Thai women, are often interpreted via normative Western ideals. Unlike Urry’s (1990) original formulation, which treats the gaze as a general phenomenon of tourist consumption, the Western female gaze, as observed in the retirement migration context, is embedded in specific power asymmetries and moral hierarchies. It reflects a complex interplay of visual subjectivity, cultural distancing, and identity affirmation. This reconceptualization thus calls for a clearer theorization of gaze as both structured perception and symbolic practice, one that is not only shaped by the viewers’ positionalities but also constitutive of the social worlds they inhabit and interpret.

3 Thailand as a Destination for Western Retirees

The Expat Insider 2024 Survey (InterNations 2024) rated Thailand the world’s sixth-most-favoured expat destination. In its 11th edition the survey canvassed more than 12 500 expatriates in 174 countries, asking about 53 indicators such as quality of life, working abroad and personal finance. A detailed 2023 country profile described the typical expat in Thailand as a 54-year-old British male retiree (InterNations 2023). Overall, 86 % of respondents reported being satisfied with life in Thailand and 71 % were happy with their social life; 81 % praised the friendliness of residents towards foreigners.

To address the global tourism demand and the demographic shift towards an aging population, the Tourism Authority of Thailand (TAT) set out to expand the tourism market towards groups with considerable purchasing power and extended stays (Sasiwongsaroj and Husa 2022). Thus, in favour of the initial Thai “Long-Stay and Health-Care Project” and in support of the Royal Thai Government, long-stay tourism has been actively promoted by the facilitation of visa permits for older people and the introduction of low monthly income requirements (Bender et al. 2018; Hudson et al. 2019).

Although, obtaining an exact number of foreign retirees in Thailand is difficult due to data restrictions and confidentiality matters, over the years several authors have tried to identify rough estimates. Only a few foreign embassies, such as Switzerland, the United Kingdom, France or Austria came up with some estimates. According to Thai Immigration statistics compiled by Tangchitnusorn (2016), the number of retirement visa holders rose five-fold in 16 years – from 10 709 in 2005 to 52 040 in 2021. Between 2008 and 2018 most applicants originated from high-income nations such as the United Kingdom, United States and Germany, alongside China and Japan (Sasiwongsaroj and Husa 2022). Geographically, many foreign retirees reside in the Bangkok metropolitan area or are concentrated around popular tourist destinations such as Pattaya, Hua Hin or Chiang Mai, Phuket or Ko Samui (Howard 2009; Tangchitnusorn 2016).

According to the Ministry of Tourism and Sports and the National Statistical Office of Thailand, the number of international tourists “substantially increased from 9.51 million in 2000 to 39.92 million in 2019”, while at the same time inbound tourism revenue increased from 8700 million Euro to 58 500 million Euro, accomplishing a significant growth of almost 700 % (Fakfare et al. 2022). In 2022, Thailand’s GDP saw a 7.3 percent boost from the tourism sector, marking an increase from the previous year following the full reopening of the country to tourists (Bank of Thailand 2025).

Tang and Zolnikov (2021) describe different pull factors motivating international migrants to move and settle down abroad. The favourable attributes of the retirement destinations are hereby compared to the prevailing and often negatively associated factors in the originating country. German lifestyle migrants in Pattaya, for example, framed Thailand as an escape from financial strain (Jaisuekun and Sunanta 2016). Similarly, Scuzzarello (2020) remarks how narratives of European retirement migrants “pitch Western and Thai societies as opposite” (1614) and how the latter is thereby often portrayed in a romanticized and idealized way. In addition to the identified pull factors, Tang and Zolnikov (2021) list different push factors that describe unfavourable or detrimental conditions in the foreign country that would make retirees terminate their stay in the receiving country. The analysis of the literature confirms the dominant drivers of retirement migration as low living costs, favourable climate, Thai lifestyle and culture, availability of good and affordable health and medical care, Thai spouses or the availability of sexual partners and marriage possibilities with Thai women.

The Expat Insider 2024 Survey by InterNations (2023) reports a pronounced gender imbalance among expats living in Thailand, with 72 % male to 27 % female. This disparity reflects the historically gendered nature of international tourism in Thailand, particularly due to its longstanding association with the sex industry. Popular media reinforces the prominent gaze by typifying the Western retiree in Thailand as “a somewhat overweight, mostly gray-haired man with a sunburnt face accompanied by a beautiful Thai woman, half his size and age” (Butratana et al. 2022, 152). Indeed, intercultural marriages and relationships between Western men and Thai women are often established abroad and later followed by ‘re-migration’ to Thailand; these relationships account for a significant share of retiree inflows.

While single men and men in Thai-Western partnerships still predominate, the number of retiring Western couples and single women is growing (Butratana et al. 2022; Vogler 2015). Yet, Western women’s everyday experiences and challenges as retirement migrants in Thailand – as well as their perceptions of the prevailing gendered dynamics in Thai–Western relationships – remain understudied, highlighting the need to foreground their perspectives.

4 Hua Hin

Hua Hin ( ) is one of eight districts (Amphoe) in Prachuap Khiri Khan province, 199 km south-west of Bangkok and covering 911 km². It aristocratic origins date back to the 1920s when kings Rama VI (King Vajiravudh) and Rama VII (King Prajadhipok) built summer residences there to escape Bangkok’s stifling climate. As of 2019, the population of Hua Hin is estimated to be around 66 000 people (Department of Provincial Administration/ Official Statistics Registration System as cited in Brinkhoff 2020). In the first quarter of 2023, the province welcomed a total of 4.5 million tourists, including 172 605 internationals. This is an increase of 39 % in comparison to the overall tourist arrivals of the previous year. (Department of Tourism and Ministry of Tourism and Sports cited in Hua Hin Today, Online Reporter 2023).

) is one of eight districts (Amphoe) in Prachuap Khiri Khan province, 199 km south-west of Bangkok and covering 911 km². It aristocratic origins date back to the 1920s when kings Rama VI (King Vajiravudh) and Rama VII (King Prajadhipok) built summer residences there to escape Bangkok’s stifling climate. As of 2019, the population of Hua Hin is estimated to be around 66 000 people (Department of Provincial Administration/ Official Statistics Registration System as cited in Brinkhoff 2020). In the first quarter of 2023, the province welcomed a total of 4.5 million tourists, including 172 605 internationals. This is an increase of 39 % in comparison to the overall tourist arrivals of the previous year. (Department of Tourism and Ministry of Tourism and Sports cited in Hua Hin Today, Online Reporter 2023).

Although official data on the size of the on-site expat community are difficult to obtain, various travel and migration-related websites consistently report a steadily growing foreign resident population of approximately 3000–5000. Researchers such as Butratana et al. (2022) and Husa et al. (2014) agree that the area is increasingly regarded as Thailand’s new ‘retirement haven’ with a rapidly growing expatriate population. Drawing on the research of Husa et al. (2014), data from the 2010 Population and Housing Census recorded a total of 2015 Western foreigners (from Europe, USA, Australia and New Zealand) in the provinces of Phetchaburi and Prachuab Khiri Kha, “with an estimated gender bias of almost 84 percent males” (150). Additional records from the Dan Sinkorn immigration office indicated that approximately 7000 Western foreigners resided in the Hua Hin area in 2010. However, as the authors suggest, given the ongoing growth of the foreign population, an estimate of around 15 000 Western residents in the Hua Hin and Cha-am areas seems to be more realistic. Moreover, official figures are likely underreported due to the absence of reporting requirements for non-annual visa holders and for those who apply for visas in other parts of Thailand. Regarding the sociodemographic composition of Hua Hin’s foreign retiree population, local estimates vary, with assumptions ranging from 50 to 90 percent of all Western migrants being single males; the remainder are typically couples who have migrated together. Regardless of the exact ratio, the expatriate scene in Hua Hin is widely reported to be dominated by older Western men accompanied by younger Thai partners (Husa et al. 2014).

Hua Hin appeals through Western-style amenities, a booming property market and expanding international-standard healthcare (Botterill 2017, 4). Its calmer atmosphere, family-friendly reputation and proximity to Bangkok distinguish it from more overtly sex-tourist hubs (Butratana et al. 2022).

5 Methodology

To explore how female Western migrants experience their retired life in Hua Hin, a qualitative design based on semi-structured interviews was adopted. This format provides enough structure to steer discussion yet grants participants the freedom to express subjective viewpoints (Flick 2014). The aim of the study was to let female retirees speak openly about everyday life and the challenges they face in a strongly gendered migration environment. As foreigners in a partially unfamiliar culture, they are significantly influenced by the Western tourist gaze in shaping their perceptions of the host country, local people and existing traditions. Thus, this research aims to explore how the interviewees interpret their current social environment and connect with the host country, its people and cultural traditions.

Based on the literature review and research questions, an interview guide was developed covering the main topics of migration motives, connectedness with country, people and Thai traditions, daily routines, gender-specific challenges and perceptions of Thai-Western relationships. The guide included core prompts while leaving space for unanticipated themes (Bryman 2012).

Interviewees were recruited purposively during a one-week field trip to Hua Hin (4–5 October 2023). In addition to a contact from the Swiss Society Hua Hin – approached via email for potential interview partners – other participants were recruited through various local Facebook expatriate groups, as the target group is highly active on this social media platform. Nine interviews were completed: two arranged by e-mail, five via Facebook and two conducted spontaneously at German-speaking social gatherings. Because recruitment relied on the German-speaking community, all interviews were held in German, yielding a sample of five Swiss, two German and one Austrian woman, aged 47–72. Seven lived with a spouse or long-term partner; one shared a community residence; one was recently separated. To protect participants’ anonymity and uphold their dignity, rights, and privacy, all names have been replaced with pseudonyms. Informed consent was obtained from all interviewees, including their agreement to the recording of the conversations.

Transcripts were coded in MAXQDA24 using a blend of a-priori and open coding. Initial codes were derived from the interview guide, followed by the addition of emergent labels and the condensation of related categories, resulting in a total of 559 assigned codes. This iterative process preserved inductive flexibility while maintaining thematic focus.

The data was coded in MAXQDA24 and analysed through the documentary methods of interpretation. According to Bohnsack et al. (2010, 20), “the documentary method aims at reconstructing the implicit knowledge that underlies everyday practice and gives an orientation to habitualized [sic!] actions independent of individual intentions and motives.” This approach has its roots in Karl Mannheim’s sociology of knowledge and draws on the ethnomethodological research tradition, which itself is influenced by Mannheim’s work. It emphasizes that verbal communication in interviews is not the only significant element for analysis; rather it is essential to reconstruct the underlying meaning conveyed through these expressions. The method distinguishes between communicative (literal) and documentary (implicit) meaning and proceeds through formulating, reflective and comparative stages, ultimately leading to the development of multidimensional typologies. For the purpose of this study, this analytical protocol enabled the reconstruction of tacit orientations underlying the women’s narratives and allowed them to be situated within existing scholarship (Bohnsack 2014; Bohnsack et al. 2010).

6 Findings: The Western female gaze explained

The present findings are organised around the Western female gaze – the analytical lens for understanding how older European women make sense of everyday life in Hua Hin. Building on Urry’s tourist-gaze theory, the Western female gaze is defined as a socially constructed way of seeing, filtered through life-course experiences, Western values and long-standing cultural knowledge of ‘Western’ gender relations.

As retirement migrants in Hua Hin, the interviewees continually interpret their everyday perceptions within the foreign Thai culture through the lens of familiar Western schemata. Living largely apart from Thai society, separated by a mutual language barrier and embedded within an existing expatriate enclave, they constructed distinct cultural spaces of their own. In this context, both Westerners and Thais often remain strangers to one another, reinforcing stereotypical perceptions that appear to confirm their search for known and established patterns. Relationships between Western men and Thai women frequently serve as a link between the expatriate community and the local population. In some cases, such relationships represent the only opportunity for Westerners to engage with Thais on a more personal level. Notably absent from these cross-cultural interactions, however, are Thai men. They were rarely mentioned in the interviews, except in occupational roles such as gardeners, taxi drivers or pool boys. Moreover, according to the interviewees, Thai men are generally not considered potential partners for single Western women.

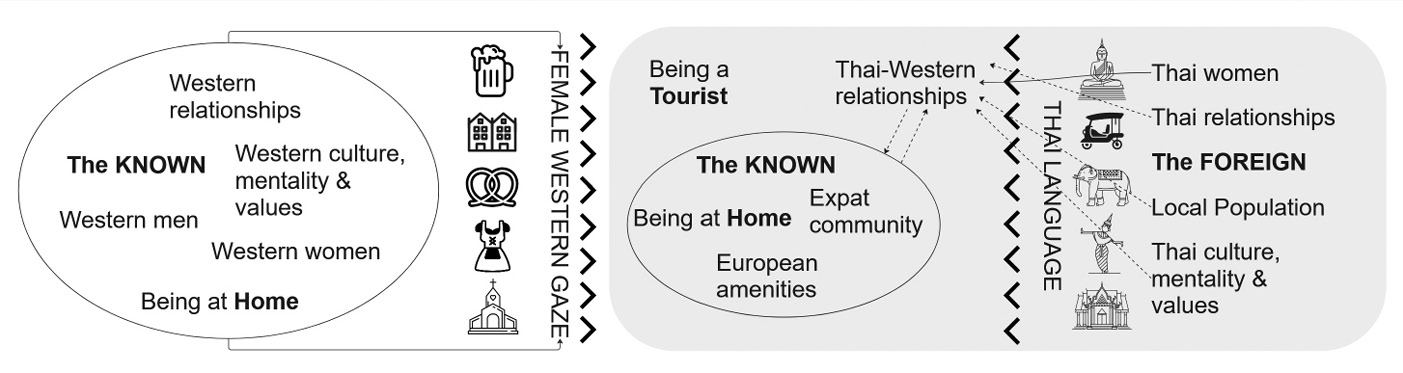

Figure 1 presents a conceptual model of the Western female gaze as it has been developed in this study. It is grounded in empirical data gathered from nine female retirees in a German-speaking expat community and synthesises dispersed narratives into an integrated framework.

Conceptual model of the Western female gaze of retirement migrants to Thailand

(own representation created on Miro)

The left- and the right-hand side of the model represent Urry’s (1980) dichotomy of the known “Western” cultural environment opposed to the foreign ‘Thai’ one. As Western retirees migrate to Thailand, their familiar surroundings are transferred into a foreign context – shown by the left-to-right arrows. Within the Thai context they cultivate a sense of home within the local expat community but continue to look at Thai life with a tourist’s eyes. Occupying this liminal space, they are neither fully integrated nor entirely foreign – being simultaneously home and a tourist. Additionally, a persistent language barrier – indicated by the right-to-left arrows – keeps most retirees and Thais apart. In this context, intercultural couples often act as a two-way bridge between the two communities.

The following sub-chapters examine different layers of the model in greater detail, demonstrating how these elements together constitute the Western female gaze. It must be acknowledged that for a matter of simplicity the model offers a generalised representation of the Western female gaze based on the present data, intentionally neglecting all other possible interfering factors such as individual sociodemographic background, biography and prior life experiences, etc.

6.1 Feeling at home vs. feeling like a tourist

Almost all interviewed women rejected the term ‘tourist’ as a label for their current living situation, a finding that aligns with Barbosa et al. (2021). Still, Reya (R9) who was born in Thailand, called herself a tourist and foreigner in Hua Hin. Similarly, Carina (R3) recognized her role as a tourist, although she is the most integrated of all respondents, speaking Thai and counting a Thai woman as her closest friend: “I clearly live here as a tourist. But because I speak, read and write Thai, I am much more integrated with the Thai people than someone who only comes down here at 65 and collects a pension.” (Pos. 26–29) The desire to distance themselves from ‘ordinary’ tourists appears to signal a wish to draw a firm line between their former and present lives and also sets them apart from other more typical tourists.

While most respondents referred to Hua Hin as home, they also acknowledged limited integration into the local community. The most obvious reason for this is found in the language barrier. Many reported initial enthusiasm for learning Thai but mentioned that they soon found it too challenging, while at the same time English proved sufficient for their daily errands. Consequently, contact with the Thai population is largely confined to landladies, service staff or partners of Western men. As sole point of contact, these women often become representatives for ‘Thai women’ at large. In the conceptual model (Fig. 1), Thai partners of Western men are positioned at the intersection of the expatriate and local communities, often acting as translators and facilitators between the two – as shown by the dashed arrows.

6.2 White privilege: perceptions of superiority and benevolence

The narratives of Western female retirees in Hua Hin revealed a recurring theme of white privilege, often articulated through both explicit and implicit comparisons between their own lifestyles and those of the local Thai population. Julia (R1), for example, justified her own privileged position by contrasting the Swiss work ethic and pension system with what she perceives as a Thai approach to life: “And we’ve worked a long time for the money so that we now have a decent pension. They don’t understand that because Thai people live from hand to mouth every day. If he has rice and a few vegetables today, then he’s happy. A banana or something, that’s enough. He doesn’t need much of a roof over his head.” (R1, Pos. 151)

Charitable engagement often reinforces retirees’ sense of moral and social superiority. Julia (R1) and Ruth (R2) highlight their involvement in local initiatives, such as supporting schools or distributing sanitary products, presenting these actions as evidence of their positive community impact. As Scuzzarello (2020) notes, such contributions, while valuable, can also serve as a way for Western migrants to justify their privileged status and derive personal gratification.

Tina (R5) and Petra (R6) express similar views, framing everyday acts – like employing local workers or giving extra payments – as support for the Thai economy and society. Tina stated: “My husband and I appreciate everyone, even those in the mall who clean the railings or tidy up. Someone always gets rid of the flowers after the rain and the garbage at our place… Our gardeners can always do something in between… And even the cab driver has to pay for his car. It’s all us… We simply want to add value with little things.” (R5, Pos. 368) And Petra added “Here and there I give them also a few extra cakes and cookies.” (R6, Pos. 373) These narratives often reflect a paternalistic dynamic, casting Thais as dependent recipients of Western benevolence.

During the interviews little consideration was given to how the influx of Westerners might raise housing costs, reshape infrastructure or widen local inequalities. In sum, the women’s accounts illustrate how white privilege is both enacted and rationalised in everyday interactions, shaping their relationships with the local population and reinforcing existing power dynamics within the context of international retirement migration.

6.3 The friendly vs. the ruthless Thai

In their descriptions of Thais, the interviewees repeatedly distinguished three types of Thai women. On one hand of the spectrum is the modest, friendly, thankful and mature partner who takes care of her Western partner until the very end. In contrast, the second type is portrayed as a younger, ruthless, calculating and financially motivated impostor who is manipulative and exploitative. A third, less frequently encountered type in Hua Hin is the stereotypical ‘bar girl’ or sex worker, often described in juvenile terms. Nearly all narratives about Thai-Western relationships referenced at least one of these typologies.

Although the interviewed women generally expressed sympathy for Thai women’s economic motivations, they showed little empathy for Western men, whom they perceived as primarily driven by sexual desire and wilfully ignoring all warning signs: “Because the men always think the Thai really loves me now. And everyone tells you, me, me, mine is different. Yes, you hear that and think yours must be different. There are exceptions. They really are different. But there are really many who only think about the money.” (R8, Pos. 71)

When describing Thai women, the respondents frequently emphasized their beauty, petite stature and overall physical attractiveness: “Yes, because they are exotic. And some of them are beautiful women and gorgeous figures. Not like these… [points to herself].” (R4, Pos. 54) By positioning themselves less favourably than their Thai counterparts, the retirees seemed to reveal underlying insecurities. This illustrates how the women reproduce the stereotypical patriarchal Western gaze that idealizes the ‘Oriental’ female beauty.

6.4 The threat of ending up single

Single Western female migrants appear to be the most vulnerable group in Hua Hin. Among those in partnerships, a persistent anxiety concerns the possibility of losing their husbands to Thai women, and if that occurs, being left alone with little prospect of finding a new partner. As Trudi (R7) put it: “If you come here as a woman. You are alone. You have a really difficult time. Because there’s no way you’ll meet another man. Because the men who are here alone want a Thai woman” (Pos. 33). The situation poses an existential risk, as many have severed ties with their countries of origin to begin a completely new life in Thailand, often without any securities back home. As such, female retirees in Thailand must either be very confident in their independence or place full trust in their current marriage or partnership. Ruth (R1) summed it up as follows: “The women are available. And if the partnership isn’t right, then. As a woman, you just have to know. Are you going? Do you trust your partner to be able and willing to endure life there together? Do you have enough in common? I think that’s just important in a relationship” (Pos. 327).

Many of the interviewed women reported initiating conversations with their husbands to seek reassurance that their partners were not interested in Thai women and knew how to conduct themselves appropriately. In some cases, couples even appeared to joke about the perceived ease with which men could be ‘stolen away’ by Thai women: “So we’ve already done the experiment. It’s my partner and me. […] He walked that way, 50 meters in front of me. Yes, he would have been gone in no time. Yes, that happens very quickly” (R4, Pos. 44). The perception of Thai women as complicated, too petite for Western men, or simply as ‘Thai bunnies’ appears to offer some Western women an additional – though fragile – sense of security in their relationships. Hanni (R8) reported the prior conversation with her partner as follows: “I mean, if you have a Thai woman, she’s half your age, half as thin as you and pretty. You know how Thai women are. […] I don’t feel like emigrating now. And then you find yourself a ‘Thai-bunny’ and I’ll be on my own” (Pos. 63–65).

The constant threat of ending up alone may help explain why women place such high value on their female friendships and the expatriate community more broadly. The interviews also revealed that many women had carefully considered the migration process and their choice of destination. Given women’s higher life expectancy and the likelihood that they will probably outlive their partners, it can be assumed that many have already made plans for how their lives might unfold in the event of their partner’s death.

6.5 The European relationship standard

When discussing Thai-Western relationships, many interviewees implied that Western-style partnerships represented the normative ideal to which intercultural couples should aspire. In this sense they differentiated between good intercultural unions – such as those in which the Thai wife genuinely cares for her Western husband, couples who met in Europe, relationships with an appropriate age gap or more functional arrangements often viewed as mutually beneficial or ‘win-win’ situations. Hanni (R8), for instance, reiterated the common stereotype of Thai women as dutiful daughters (Angeles and Sunanta 2009), who are expected to support their extended families: “I think the main thing is really the money, because they are very closely connected to their family and the most important thing for them is that their family is doing well” (Pos. 50). In comparing European and intercultural relationships, Trudi (R7) described Thai women as less complicated and more desirable partners due to their perceived submissiveness, contrasting this with the autonomy of European women: “It’s much easier to be with a Thai woman than with a European woman. Because Thai women are submissive everywhere. And European women have their own will, their own attitude. And that is challenging for a man” (R7, Pos. 42).

These findings correspond with research by Howard (2009) and Vogler (2015a), who documented similar views among male Western migrants. Overall, the female respondents in this study regarded relationships between Western men and Thai women as both common and socially accepted, frequently emphasizing that they had no personal objection to them.

7 Conclusion

This article offers a critical examination of the experiences of Western female retirees in Hua Hin, Thailand, thereby contributing to the often-underrepresented perspective of women in the field of international retirement migration. By exploring their living situations, challenges, and social relationships, the study sheds light on how older women navigate the intersection of gender, migration, and intercultural dynamics in a foreign context. The findings reveal that female retirees in Hua Hin face distinct challenges, particularly those related to social isolation, the threat of ending up alone, and the complexities of acculturation in a predominantly male-oriented expatriate environment. To cope with these issues, many women form close-knit female support networks, which play a vital role in helping them adapt and feel secure in their new surroundings.

The concept of the Western female gaze, as developed in this study, captures the continuous comparison between familiar Western cultural norms and the foreign Thai context. This gaze shapes a nuanced sense of belonging that is at once comforting and alienating. The study also uncovers the ambivalent attitudes towards Thai women, who are simultaneously admired and perceived as rivals within a social landscape dominated by Western male-Thai female relationships. This ambivalence highlights the complexities of intercultural interactions in expatriate communities, where gendered and cultural differences are constantly negotiated. Importantly, this research challenges the prevailing male-centric narrative in retirement migration literature by arguing for greater attention to the experiences and perspectives of women. As the population of older, single female retirees continues to grow, their voices will become increasingly central to understanding the broader dynamics of international retirement migration.

The study also acknowledges several limitations that may have influenced its findings. Despite efforts to remain open to respondent’s perspectives, the analysis was inevitably influenced by the researcher’s own assumptions, stereotypes and expectations regarding retirement migrants and intercultural couples. Limited exposure to on-site expatriate communities may have restricted deeper engagement with local contexts and the full range of retiree experiences. Furthermore, the researcher’s empathy with female participants – stemming from a shared female gaze – may have contributed to a more critical judgment of older Western men and a more sympathetic stance toward younger Thai women. The generational gap between the researcher and participants may also have introduced interpretive biases. In addition, the sample was confined to a relatively homogenous group within the German-speaking retirement community, potentially leading to a one-sided portrayal of female Western retirees in Hua Hin and limiting insights into Thai culture and the broader retiree population. Hence, it would also be advisable to validate the key elements of the developed conceptual model using a larger and more diverse sample.

Future research should continue to investigate the gendered dimensions of retirement migration, with particular attention to the voices and experiences of women and other marginalised groups that remain under-represented in the literature. Addressing these gaps will support a more comprehensive understanding of international retirement migration – one that fully incorporates the diversity of migrants’ experiences, regardless of gender or other sociodemographic factors. Further studies should also examine the experiences of female retirees in a variety of cultural contexts to deepen insights into the global dynamics of aging and mobility.

About the author

Stefanie Wallinger is a researcher and lecturer at the Department of Business & Tourism at Salzburg University of Applied Sciences. Her research focuses on qualitative social science tourism research and the interdisciplinarity of gender and tourism studies.

Stefanie Wallinger ist Researcherin und Dozentin am Department Business & Tourism der Fachhochschule Salzburg. Ihre Forschungsschwerpunkte liegen in der qualitativen, sozialwissenschaftlichen Tourismusforschung und Interdisziplinarität von Gender- und Tourismuswissenschaft.

Funder Name: AKTF Tourismusforschung und Initiative Tourismusforschung

Grant Number: AKTF-ITF-Preis für die beste Bachelorarbeit 2025

References

Åkerlund, Ulrika, and Linda Sandberg. 2015. “Stories of Lifestyle Mobility: Representing Self and Place in the Search for the ‘Good Life.’” Social & Cultural Geography 16 (3): 351–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2014.987806.10.1080/14649365.2014.987806Search in Google Scholar

Angeles, Leonora C., and Sirijit Sunanta. 2009. “Demanding Daughter Duty: Gender, Community, Village Transformation, and Transnational Marriages in Northeast Thailand.” Critical Asian Studies 41 (4): 549–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/14672710903328021.10.1080/14672710903328021Search in Google Scholar

Bank of Thailand. 2025. “Tourism Indicators.” https://app.bot.or.th/BTWS_STAT/statistics/ReportPage.aspx?reportID=875&language=eng (accessed May 21, 2025).Search in Google Scholar

Barbosa, Belem, Claudia Amaral Santos, and Márcia Santos. 2021. “Tourists with Migrants’ Eyes: The Mediating Role of Tourism in International Retirement Migration.” Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change 19 (4): 530–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/14766825.2020.1727489.10.1080/14766825.2020.1727489Search in Google Scholar

Bender, Désirée, Tina Hollstein, and Cornelia Schweppe. 2018. “International Retirement Migration Revisited: From Amenity Seeking to Precarity Migration?” Transnational Social Review 8 (1): 98–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/21931674.2018.1429080.10.1080/21931674.2018.1429080Search in Google Scholar

Bohnsack, Ralf. 2014. “Documentary Method.” In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Analysis, edited by Uwe Flick. SAGE Publications Ltd. https://www.ufs.ac.za/docs/librariesprovider68/resources/methodology/uwe_flick_(ed-)-_the_sage_handbook_of_qualitative(z-lib-org)-(1).pdf?sfvrsn=db96820_(accessed July 24, 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Bohnsack, Ralf, Nicolle Pfaff, and Wivian Weller, eds. 2010. Qualitative Analysis and Documentary Method: In International Educational Research. Verlag Barbara Budrich. https://doi.org/10.3224/86649236.10.3224/86649236Search in Google Scholar

Botterill, Kate. 2017. “Discordant Lifestyle Mobilities in East Asia: Privilege and Precarity of British Retirement in Thailand: Discordant Lifestyle Mobilities in East Asia.” Population, Space and Place 23 (5): e2011. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.2011.10.1002/psp.2011Search in Google Scholar

Brinkhoff, Thomas. 2020. “Hua Hin (Prachuap Khiri Khan, Western Region, Thailand) – Population Statistics, Charts, Map, Location, Weather and Web Information.” Citypopulation. https://www.citypopulation.de/en/thailand/western/prachuap_khiri_khan/7798__hua_hin/ (accessed July 24, 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Bryman, Alan. 2012. Social Research Methods. 4th ed. Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Butratana, Kosita, Alexander Trupp, and Karl Husa. 2022. “Intersections of Tourism, Cross-Border Marriage, and Retirement Migration in Thailand.” In Intersections of Tourism, Migration, and Exile, 1st ed. edited by Natalia Bloch and Kathleen Adams. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003182689-9.10.4324/9781003182689-9Search in Google Scholar

Fakfare, Pipatpong, Jin-Soo Lee, and Heesup Han. 2022. “Thailand Tourism: A Systematic Review.” Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 39 (2): 188–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2022.2061674.10.1080/10548408.2022.2061674Search in Google Scholar

Flick, Uwe. 2014. An Introduction to Qualitative Research. 5th ed. SAGE Publications Ltd.Search in Google Scholar

Gambold, Liesl. 2013. “Retirement Abroad as Women’s Aging Strategy.” Anthropology & Aging 34 (2): 184–98. https://doi.org/10.5195/aa.2013.19.10.5195/aa.2013.19Search in Google Scholar

Howard, Robert W. 2008. “Western Retirees in Thailand: Motives, Experiences, Wellbeing, Assimilation and Future Needs.” Ageing and Society 28 (2): 145–63. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X07006290.10.1017/S0144686X07006290Search in Google Scholar

Howard, Robert W. 2009. “The Migration of Westerners to Thailand: An Unusual Flow from Developed to Developing World.” International Migration 47 (2): 193–225. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2435.2009.00517.x.10.1111/j.1468-2435.2009.00517.xSearch in Google Scholar

Hua Hin Today, Online Reporter. 2023. “4 Million Tourists, of Which 173 000 Were Foreigners, Visited Prachuap Khiri Khan in Q1 2023.” Hua Hin Today – Your Premier Source for News, Reports, Events, and Information in Hua Hin, June 3. https://www.huahintoday.com/hua-hin-news/4-million-tourists-of-which-173000-were-foreigners-visited-prachuap-khiri-khan-in-q1-2023/ (accessed July 24, 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Hudson, Simon, Kevin Kam Fung So, Jing Li, Fang Meng, and David Cárdenas. 2019. “Persuading Tourists to Stay – Forever! A Destination Marketing Perspective.” Journal of Destination Marketing & Management 12 (June): 105–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2019.02.007.10.1016/j.jdmm.2019.02.007Search in Google Scholar

Husa, Karl, Christian Vielhaber, Julia Jöstl, Krisztina Veress, and Birgit Wieser. 2014. “Searching for Paradise? International Retirement Migration to Thailand – A Case Study of Hua Hin and Cha-Am.” In Southeast Asian Mobility Transitions – Issues and Trends in Migration and Tourism, edited by Alexander Trupp, Karl Husa, and Helmut Wohlschlägl. Abhandlungen zur Geographie und Regionalforschung 19. Wien.Search in Google Scholar

International Organization for Migration. 2024a. “Interactive World Migration Report 2024.” https://worldmigrationreport.iom.int/msite/wmr-2024-interactive/ (accessed July 24, 2024)Search in Google Scholar

International Organization for Migration. 2024b. World Migration Report 2024. United Nations.Search in Google Scholar

InterNations. 2023. The Expat Insider 2023 Survey Report. https://cms.in-cdn.net/cdn/file/cms-media/public/2023-07/Expat-Insider-2023-Survey-Report.pdf (accessed July 15, 2024).Search in Google Scholar

InterNations. 2024. “Expat Insider 2024.” Expat Insider 2024. The World Through Expat Eyes. https://www.internations.org/expat-insider/ (accessed July 15, 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Jaisuekun, Kwanchanok, and Sirijit Sunanta. 2016. “Lifestyle Migration in Thailand: A Case Study of German Migrants in Pattaya.” Thammasat Review 19 (2): 2. https://doi.org/10.14456/TUREVIEW.2016.13Search in Google Scholar

Koch-Schulte, John. 2008. “Planning for International Retirement Migration and Expats: A Case Study of Udon Thani, Thailand.” The University of Manitoba. http://hdl.handle.net/1993/3020 (accessed June 22, 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Kordel, Stefan. 2015. “Being a Tourist – Being at Home: Reconstructing Tourist Experiences and Negotiating Home in Retirement Migrants’ Daily Lives.” In Practising the Good Life: Lifestyle Migration in Practices, edited by Kate Torkington, Inês David, and João Sardinha. Cambridge Scholars Publishing.Search in Google Scholar

Lulle, Aija, and Russell King. 2016. “Ageing Well: The Time–Spaces of Possibility for Older Female Latvian Migrants in the UK.” Social & Cultural Geography 17 (3): 444–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2015.1089584.10.1080/14649365.2015.1089584Search in Google Scholar

Pritchard, Annette. 2004. “Gender and Sexuality in Tourism Research.” In A Companion to Tourism, edited by C Michael Hall and Allan M Williams. Blackwell Companions to Geography. Blackwell.Search in Google Scholar

Pritchard, Annette, and Nigel J Morgan. 2000. “Privileging the Male Gaze.” Annals of Tourism Research 27 (4): 884–905. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(99)00113-9.10.1016/S0160-7383(99)00113-9Search in Google Scholar

Repetti, Marion, and Toni Calasanti. 2023. “Retirement Migration.” In Retirement Migration and Precarity in Later Life, 1st ed. Bristol University Press. https://doi.org/10.46692/9781447358244.10.51952/9781447358244.ch001Search in Google Scholar

Samarathunga, W. H. M. S., and Li Cheng. 2021. “Tourist Gaze and beyond: State of the Art.” Tourism Review 76 (2): 344–57. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-06-2020-0248.10.1108/TR-06-2020-0248Search in Google Scholar

Sampaio, Dora. 2018. “A Place to Grow Older … Alone? Living and Ageing as a Single Older Lifestyle Migrant in the Azores.” Area 50 (4): 459–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/area.12414.10.1111/area.12414Search in Google Scholar

Sasiwongsaroj, Kwanchi, and Karl Husa. 2022. “Growing Old and Getting Care: Thailand as a Hot Spot of International Retirement Migration.” In Migration, Ageing, Aged Care, and the Covid-19 Pandemic in Asia – Case Studies from Thailand and Japan, edited by Kwanchi Sasiwongsaroj, Karl Husa, and Helmut Wohlschlägl. Abhandlungen Zur Geographie Und Regionalforschung 24. Department of Geography and Regional Research, University of Vienna.Search in Google Scholar

Savaş, Esma Betül, Juul Spaan, Kène Henkens, Matthijs Kalmijn, and Hendrik P. Van Dalen. 2023. “Migrating to a New Country in Late Life: A Review of the Literature on International Retirement Migration.” Demographic Research 48 (February): 233–70. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2023.48.9.10.4054/DemRes.2023.48.9Search in Google Scholar

Schweppe, Cornelia, ed. 2022. Retirement Migration to the Global South: Global Inequalities and Entanglements. Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-6999-6.10.1007/978-981-16-6999-6Search in Google Scholar

Scuzzarello, Sarah. 2020. “Practising Privilege. How Settling in Thailand Enables Older Western Migrants to Enact Privilege over Local People.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (8): 1606–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1711570.10.1080/1369183X.2020.1711570Search in Google Scholar

Tang, Yuan, and Tara Rava Zolnikov. 2021. “Examining Opportunities, Challenges and Quality of Life in International Retirement Migration.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18 (22): 12093. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182212093.10.3390/ijerph182212093Search in Google Scholar

Tangchitnusorn, Kanokwan. 2016. “International Retirement Migration of Westerners to Thailand: Decision-Making Process, Wellbeing, Assimilation, and Impacts on Destination.” Doctor of Philosophy, Chulalongkorn University. https://doi.org/10.58837/CHULA.THE.2016.1490.10.58837/CHULA.THE.2016.1490Search in Google Scholar

Thang, Leng Leng, Sachiko Sone, and Mika Toyota. 2012. “Freedom Found? The Later-Life Transnational Migration of Japanese Women to Western Australia and Thailand.” Asian and Pacific Migration Journal 21 (2): 239–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/011719681202100206.10.1177/011719681202100206Search in Google Scholar

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. 2020. “International Migrant Stock 2020.” https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/content/international-migrant-stock (accessed July 24, 2025).Search in Google Scholar

Urry, John. 1990. The Tourist Gaze: Leisure and Travel in Contemporary Societies. Theory, Culture & Society. Sage Publications.Search in Google Scholar

Urry, John. 2009. The Tourist Gaze. 2. ed., Reprinted. Theory, Culture & Society. Sage.Search in Google Scholar

Vogler, Christina. 2015. “Change and Challenges for Foreign Retirees in Thailand. An Interview with Nancy Lindley.” Austrian Journal of South-East Asian Studies, 209–14. https://doi.org/10.14764/10.ASEAS-2015.2-7.Search in Google Scholar

Williams, Allan M, and C Michael Hall. 2000. “Tourism and Migration: New Relationships between Production and Consumption.” Tourism Geographies 2 (1): 5–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/146166800363420.10.1080/146166800363420Search in Google Scholar

Zhang, Yang, and Michael John Hitchcock. 2017. “The Chinese Female Tourist Gaze: A Netnography of Young Women’s Blogs on Macao.” Current Issues in Tourism 20 (3): 315–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2014.904845.10.1080/13683500.2014.904845Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.